Submitted:

31 July 2025

Posted:

01 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background on Avian Influenza Viruses

1.2. Significance of the Topic

1.3. Objectives of the Review

- i.

- Examine the epidemiological patterns, virological properties, and clinical outcomes associated with H5N1 and H7N9 infections;

- ii.

- Critically evaluate current global surveillance systems, outbreak response strategies, and mitigation efforts;

- iii.

- Identify critical knowledge gaps and vulnerabilities in pandemic preparedness frameworks;

- iv.

- Propose evidence-based recommendations to enhance early detection, containment, and prevention of future avian influenza outbreaks.

2. Epidemiology of H5n1 and H7n9

2.1. Global Distribution and Spread

2.1.1. H5N1: -

2.1.2. H7N9: -

2.2. Case Fatality Rates and Clinical Outcomes

2.2.1. H5N1: -

2.2.2. H7N9: -

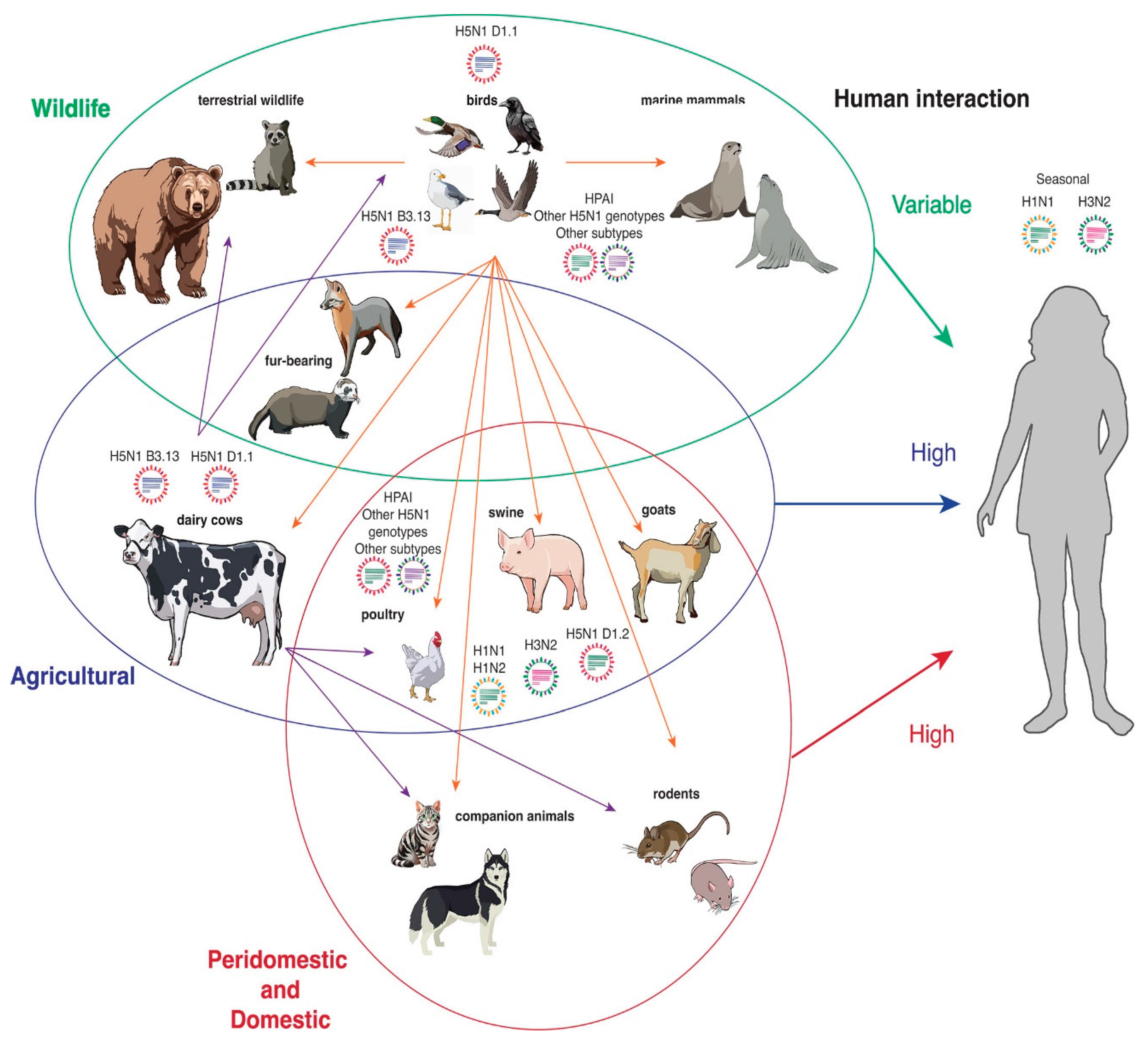

2.3. Zoonotic Potential

Role of Poultry Farming, Live Bird Markets, and Migratory Birds

3. Evolution of H5N1 and H7N9

3.1. Genetic Characteristics

3.1.1. Genomic Differences Between H5N1 and H7N9

3.1.2. Mechanisms of Antigenic Drift and Antigenic Shift Between H5N1 and H7N9

- Antigenic Drift

- Antigenic Shift

3.2. Adaptation to Human Hosts

- i.

-

H5N1 AdaptationsAdaptation of H5N1 to human hosts involves several key genetic changes:

- HA mutations, such as Q222L and G224S, promote a shift from α2,3- to α2,6-SA receptor binding [35].

- Additional mutations at HA positions 129 and 134 can further modulate binding affinity.

- Polymerase complex mutations, notably E627K, D701N, and S714R in PB2, enhance viral replication efficiency in mammalian cells [36].

- Mutations in NA can improve viral fitness by enhancing replication in human airway epithelial cells and facilitating immune escape.

- ii.

-

H7N9 AdaptationsThe H7N9 virus has similarly exhibited key adaptations:

- Early isolates demonstrated dual receptor specificity, with mutations such as G186V and Q226L in HA facilitating α2,6-SA binding [37].

- The PB2-E627K substitution has been implicated in increased polymerase activity and replication in mammals.

- Additional mutations in the NP, M, PA, and NA genes contribute to enhanced virulence, replication efficiency, and modulation of the host immune response [38].

- NS1 protein mutations have been associated with antagonism of interferon responses, supporting viral persistence in human hosts.

3.3. Antigenic Diversity and Vaccine Challenges

Impact of Viral Diversity on Vaccine Development

- H5N1

- H7N9

3.4. Current Vaccines and Their Limitations

3.4.1. H5N1 Vaccine Candidates and Limitations

- i.

-

Approved VaccinesSeveral H5N1 vaccines have been licensed, primarily for pandemic stockpiling or high-risk occupational groups [41]:

- Audenz (FDA, 2020): An adjuvanted, cell-culture-derived H5N1 vaccine for individuals aged six months and older.

- Sanofi Pasteur H5N1 Vaccine (FDA, 2007): Approved for adults aged 18–64 at elevated risk.

- GSK Adjupanrix and Prepandemic Vaccines (EU-approved): Based on A/VietNam/1194/2004 (H5N1) strain.

- Seqirus Vaccines (Celldemic, Incellipan): EMA-approved for avian influenza preparedness.

- CSL Seqirus H5N8 Vaccine: Targets clade 2.3.4.4b HA, with N8 NA, using an MF59 adjuvant.

- Antigenic Drift: Rapid viral evolution necessitates frequent updates to vaccine strains.

- Cross-Protection Gaps: Vaccines targeting one clade may not be effective against others.

- Low Immunogenicity: Most H5N1 vaccines require adjuvants and prime-boost regimens.

- Limited Field Data: Real-world effectiveness in preventing disease or transmission remains unproven.

- Stockpile Constraints: Current global vaccine reserves are insufficient for large-scale deployment.

- Low Uptake: Vaccination rates among high-risk occupational groups remain poor.

- Animal Model Limitations: Predictive value of mRNA vaccine studies in ferrets has not translated reliably to humans.

3.4.2. H7N9 Vaccine Candidates and Limitations

- Poultry: China introduced a bivalent inactivated H5/H7 vaccine, reducing human cases post-wave 5, though sterilizing immunity remains elusive.

-

Human Vaccines: Multiple candidates have been developed:

- Inactivated Vaccines: Require high doses and adjuvants for robust protection.

- Live-Attenuated Vaccines (LAIVs): Offer stronger T-cell responses and heterosubtypic protection potential.

- Virus-Like Particles (VLPs): Show promise for safety and immunogenicity in early trials.

- Antigenic Drift and Evolution: Ongoing viral changes require frequent updates to vaccine compositions.

- Diverse Viral Lineages: Genetic variability complicates the design of broadly protective vaccines.

- Need for Universal Vaccines: Broader cross-protection strategies remain a critical unmet need.

- Suboptimal Immune Responses: Current vaccines often fail to stimulate sufficient neutralizing antibody and NA-specific responses.

- Persistent Threat: Despite decreased human cases, H7N9 and related viruses continue to circulate in poultry and wild birds, necessitating ongoing vigilance.

4. Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

4.1. Symptoms and Disease Progression:

- i.

- Initial symptoms often include influenza-like illness such as fever (including high fever), cough, muscle or body aches (myalgia), headaches, and fatigue [44].

- ii.

- Other symptoms can include sore throat and shortness of breath or difficulty breathing (dyspnea).

- iii.

- Diarrhea has been reported in both infections, occurring in more than 50% of patients in one H5N1 series from Vietnam but less than 10% in others. It is listed as a less common symptom for H5N1 and among typical flu symptoms for H7N9.

- iv.

- Nausea and vomiting can also occur, sometimes following initial flu-like symptoms in H5N1 [44].

4.2. Differences in Clinical Presentation and Complications:

- i.

- Disease Progression: Both viruses can rapidly attack the lower respiratory tract, leading to severe pneumonia, bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

- ii.

- Extrapulmonary Manifestations: H5N1 infection more often leads to extrapulmonary manifestations compared to pandemic influenza viruses. These can include liver impairment with elevated transaminases, particularly in severe cases. Notably, H5N1 infections are characterised by a heightened inclination towards Central Nervous System (CNS) disease manifestation when contrasted with seasonal influenza. In animal models, H5N1 can access the CNS via olfactory and trigeminal nerves, causing severe meningoencephalitis. In animals generally, HPAIV clade 2.3.4.4b spontaneous infections are characterised by remarkable neurotropism and systemic virus spread [46].

- iii.

- Uncommon Features: H7N9 infection presents some uncommon clinical features compared to H5N1 (Table 4), such as conjunctivitis and encephalopathy, while common symptoms like nasal congestion and rhinorrhea may be less apparent. Conversely, recent mild H5N1 cases in the US have predominantly presented with conjunctivitis [47].

- iv.

- Age and Comorbidities: H7N9 infection severity increases with increasing age, with mild diseases observed in young children and more severe disease in adults. Coexisting chronic medical conditions, such as hypertension and diabetes, are commonly observed in H7N9 cases. Historically, H5N1 cases have had a younger mean age and coexisting conditions were uncommon [47].

- v.

- Immune Response: Severe H7N9 and H5N1 infections are associated with high inflammatory cytokine and chemokine levels in the lungs and peripheral blood, referred to as hypercytokinemia or cytokine storm. While potentially correlated with severe disease, hypercytokinemia levels caused by H7N9 may be lower than those caused by H5N6. HP-H7N9 seemed to induce higher cytokine levels than LP-H7N9, but the difference was not significant in one study [48].

- vi.

- Fatal Outcomes: In both infections, fatal outcomes are often associated with the development of complications such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (Table 4), severe pneumonia, and multi-organ failure (including respiratory and renal failure, pulmonary haemorrhage, pneumothorax, and pancytopenia). For H5N1, fatal outcomes have been associated with high viral loads, lymphopenia, and elevated inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. For H7N9, multiple organ failure is a major cause of death. Nosocomial bacterial infections, often with antibiotic-resistant organisms, are also common in severe H7N9 cases [49].

4.3. Diagnostic Tools:

4.3.1. RT-PCR and Real-Time PCR:

- i.

-

Serological tests: Detection of H5N1-specific antibodies is essential for epidemiological investigations.

- Microneutralisation (MN) assay: More specific than the haemagglutination inhibition (HI) assay for specific H5N1 diagnosis. It is the preferred gold standard for serodiagnosis of H5N1, preferably confirmed by Western blotting. Most individuals develop a positive titre 3 weeks after symptom onset. MN or HI tests can be used to test for seroprevalence in healthy populations, but they need validation. Note that HI has limited value for detecting antibodies against avian viruses in humans/mammals due to low sensitivity [53].

- ii.

- Rapid diagnostic kits / Antigen detection methods: These methods, such as rapid immunochromatographic assays or direct immunofluorescence, can provide rapid diagnosis to guide immediate management. They have a sensitivity of 50–80% and specificity of 90% for virus detection. Reliability depends on factors like specimen type, quality, and timing. Enzyme immunoassays are not widely used for human diagnostics [54].

4.3.2. Virus Isolation: Considered the Gold Standard for Virus Propagation and Detection

- Egg culture: Used for virus isolation.

- Cell culture (e.g., MDCK cells): Provides highly specific laboratory diagnosis. This method is significantly more sensitive than antigen detection but requires a BSL-3 facility, special training, and approval for H5N1 due to it being a select agent in some countries. Sample storage and transportation conditions are important [55].

- iv.

-

Novel Techniques: More recently, user-friendly, cost-effective, specific, and potentially point-of-care methods are being employed, including [56]:

- LAMP (Loop-mediated Isothermal Amplification).

- RT-LAMP (Reverse Transcription Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification).

- SAMBA (Simple Amplification-Based Assay).

- NASBA (Nucleic Acid Sequencing-Based Amplification).

- Molecular Integration with Nanotechnology.

- Biosensors Development.

4.4. Treatment Options:

4.4.1. Neuraminidase Inhibitors (NAIs):

4.4.2. Polymerase Inhibitors:

4.4.3. Adamantanes:

4.4.4. Resistance:

4.4.5. Supportive Care:

4.4.6. Future Directions:

5. Global Response and Public Health Measures:

5.1. Surveillance Systems:

Various Types of Surveillance Are Employed:

- i.

- Monitoring of animal populations: This includes surveillance data and mortality data from poultry and wild birds. For North America, this data is collated from sources like USDA-APHIS, USGS-WHISPers, and CFIA/ACIA. Large-scale animal disease data is managed by various authorities including local, state, indigenous, federal, and transnational agencies, as well as non-governmental research groups. The FAO's EMPRES-i+ database is a primary collation of international regional/country-level data, capturing approximately 30% of H5N1 disease events. WOAH-WAHIS is another reporting system used globally [1,67].

- ii.

- Human case surveillance: Countries should remain vigilant for potential human cases of avian influenza, especially in geographic areas where the virus is highly circulating in poultry, wild birds, or other animals. Healthcare workers in these areas need to be aware of the epidemiological situation and the range of symptoms associated with avian influenza infection in humans. Surveillance systems for seasonal influenza have also highlighted the importance of typing viruses to detect zoonotic avian influenza cases. In the U.S., state and local public health officials have monitored occupationally exposed persons for symptoms after exposure to potentially infected animals and collected specimens from symptomatic persons. Most recent U.S. cases were identified through symptom monitoring. Monitoring of bovine veterinary practitioners for HPAI A(H5) infections has also occurred [68].

- iii.

- Wastewater surveillance: This is another method being used, with the CDC detecting the presence of influenza A virus in wastewater in several U.S. states and cities. Virome sequencing has also identified HPAI H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b in wastewater. However, identifying specific subtypes at the national level may be challenging with current CDC methods, and the source (avian, bovine, or human) can be uncertain [69].

- iv.

- Genetic surveillance: Ongoing genetic analysis and monitoring are needed due to genetic variations among HPAI H5N1 strains. Studying mutations and reassortment events provides insights into the virus's evolutionary potential, transmission dynamics, and pathogenicity [70].

- v.

- Serological surveillance: Detection of H5N1-specific antibodies is essential for epidemiological investigations. Serological studies, combined with mortality data, can help infer levels of flock immunity in different species. Testing for seroprevalence in healthy populations can be done using MN or HI tests, though HI has limited value for detecting antibodies against avian viruses in humans/mammals due to low sensitivity [71]. Serology testing was conducted in one U.S. state for H5N1.

5.2. Prevention Strategies for HPAI Outbreaks and Transmission:

Range of Strategies to Prevent HPAI Outbreaks: -

- i.

- Minimising Exposure: The most effective approach to prevent human H5N1 infection is to minimise exposure to potential sources of the virus. This includes avoiding contact with dead, sick, or abnormal birds and mammals unless properly trained and equipped. Caution with pets is also important [73].

- ii.

- Protection for Exposed Individuals: Public health efforts focus on protecting workers exposed to potentially infected animals. This includes the implementation of prevention measures on farms, including PPE use. Despite the importance, low rates of PPE use have been noted among dairy workers [74].

- iii.

- Biosecurity Measures: Improving biosecurity measures is a priority for the poultry industry to reduce transmission to and within domestic poultry. Good farm biosecurity is paramount. This includes implementing policies for visitors [73].

- iv.

- Live Poultry Market (LPM) Interventions: LPMs have been identified as major sources and hotspots for avian influenza outbreaks and human infection. Closure of live poultry markets has been highly effective in reducing the risk of H7N9 infection in humans. Other effective interventions in the LPM system include rest days and banning live poultry overnight. Enhanced disinfection and regular closure of wet markets also reduced transmission risk [73].

- v.

-

Vaccination:

- Poultry Vaccination: Vaccination in the poultry population is practiced in many countries. A bivalent inactivated H5/H7 vaccine for chickens was introduced in China, and multiple strategies, including this vaccine, seem to have been quite successful against emerging H7N9 viruses. A vaccine against one clade of virus may not protect against other clades or subclades due to antigenic differences. Vaccinating cattle to reduce transmission is also being explored, with research teams in the early stages of developing vaccines for livestock [75].

- Human Vaccination: Development and deployment of effective vaccines against HPAI H5N1 are of paramount importance. Several H5N1 vaccines have received approval, including Audenz (FDA, 2020) for individuals aged six months and older at increased risk, Sanofi Pasteur's vaccine (FDA, 2007) for individuals aged 18-64 at elevated risk [76], GlaxoSmithKline’s prepandemic vaccine (EU, 2008), and Adjupanrix (EU, 2009). The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recommended vaccines like Celldemic and Incellipan for use in the EU. Research focuses on improving vaccine efficacy, broadening protection, and optimising delivery strategies. mRNA vaccines are being developed for faster production and updating. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has plans to produce millions of doses of H5N1 vaccine. Some countries, like Finland and Austria, have made H5 vaccines available to individuals with higher exposure risks like farm workers as a precaution. Strategic deployment of vaccination is needed to minimise human cases. However, existing stockpiles may be insufficient in a pandemic scenario [77].

- vi.

-

Adaptive Management: Effective disease management responses depend on improved systems for decision making, particularly in the face of uncertainty. Formal methods of decision analysis can aid in allocating scarce resources and prioritisation of scientific inquiry to inform management and conservation actions. Management-driven scientific inquiry is urgently needed to establish recommended disease response protocols [78].

- Addressing Underlying Factors: In the longer term, addressing underlying factors such as intensive farming practices and wildlife trade, which create environments conducive to viral mutations, is crucial in preventing pandemics [3].

- Pasteurisation: The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) emphasize the critical need for pasteurisation of dairy products to mitigate the risk of human infection [79].

5.3. International Collaboration:

5.3.1. One Health Approach:

5.3.2. Information Sharing and Coordination:

5.3.3. Involvement of International Organisations:

- i.

- WHO (World Health Organization).

- ii.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations).

- iii.

- WOAH (World Organisation for Animal Health).

- iv.

- ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control).

- v.

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority).

5.3.4. Collaboration Between Agencies:

6. Lessons Learned and Future Directions

6.1. Insights from Past Outbreaks:

6.2. Emerging Threats by 2025:

6.3. Recommendations for 2025 and Beyond:

Specific Recommended Actions Include:

- i.

- Strengthening Surveillance: Strengthening global surveillance systems for avian influenza is crucial for promptly identifying and monitoring emerging strains, especially those with zoonotic potential (Supplementary file 2). This involves continuous monitoring of wild bird populations, domestic poultry, and high-risk areas. Surveillance should also aim to detect changes in virus pathogenicity and transmissibility and identify potential mammal-to-avian transmission [68,72].

- ii.

- Enhancing Genetic Monitoring: Ongoing genetic analysis and monitoring of viral evolution is needed due to genetic variations, studying mutations and reassortment events to understand evolutionary potential, transmission dynamics, and pathogenicity. Genetic characterisation should be reinforced, especially in areas with mammalian infections. Monitoring viral evolution for changes that stabilise the HA molecule is particularly important [29,35,70].

- iii.

- Advancing Vaccination Strategies: Development and deployment of effective vaccines against HPAI H5N1 are of paramount importance. Research should focus on improving vaccine efficacy, broadening protection across strains, and optimising delivery. Vaccination should be considered in regions where poultry are not vaccinated to protect production and reduce human exposure risk. Controlling the dairy cattle outbreak may require vaccination of cows or better infection control. Vaccination for animals in fur farms and enhanced biosecurity measures are also suggested [11].

- iv.

- v.

- Strengthening Biosecurity: Implementing stringent biosecurity measures and prevention strategies to minimize exposure to potential sources of the virus. This includes avoiding contact with dead, sick, or abnormal birds and mammals unless properly trained and equipped, using appropriate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for workers exposed to potentially infected animals, implementing adequate biosafety and biosecurity at occupational settings, and improving biosecurity measures on farms [73].

- vi.

- vii.

- Applying Structured Decision-Making (SDM): Utilize SDM frameworks to guide resource allocation, prioritize research, and develop effective outbreak management protocols under uncertainty [81].

- viii.

- Adopting a One Health Approach: Adopting a cohesive One Health approach encompassing human, animal, and environmental health sectors is crucial for addressing disease dynamics and managing responses effectively. EFSA, ECDC and WHO have provided practical guidance for managing zoonotic outbreaks using this interdisciplinary approach [80].

- ix.

- Addressing Root Causes: Tackle systemic risk factors, including intensive animal farming, wildlife trade, and ecosystem disruption, which drive viral emergence and cross-species transmission [87].

7. Conclusions

- i.

- Strengthening surveillance systems across wildlife, poultry, cattle, and high-risk human populations to detect emerging strains and critical evolutionary changes.

- ii.

- Enhancing genetic monitoring to track mutations linked to pathogenicity, host adaptation, and transmission potential.

- iii.

- Accelerating vaccine development and deployment, with a focus on broader protection, rapid scalability, and inclusion of under-vaccinated regions and sectors.

- iv.

- Advancing antiviral research and improving therapeutic strategies.

- v.

- Implementing stringent biosecurity and exposure prevention measures at farms, markets, and occupational settings.

- vi.

- Fostering international collaboration and data sharing to enable rapid response and containment.

- vii.

- Adopting a One Health approach that integrates human, animal, and environmental health responses.

- viii.

- Investing in research and structured decision-making frameworks to prioritize critical knowledge gaps and guide evidence-based policy actions.

- ix.

- Promoting long-term structural changes in farming practices and wildlife trade management to reduce zoonotic spillover risks.

- x.

- Ensuring comprehensive testing and pasteurization of dairy products to minimize risks of foodborne transmission.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Harvey, J.A.; Mullinax, J.M.; Runge, M.C.; Prosser, D.J. The changing dynamics of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1: Next steps for management & science in North America. Biological Conservation 2023, 282, 110041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziosi, G.; Lupini, C.; Catelli, E.; Carnaccini, S. Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5 clade 2. 3. 4.4 b virus infection in birds and mammals. Animals 2024, 14, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charostad, J.; Rukerd, M.R.Z. , Mahmoudvand, S. ; Bashash, D.; Hashemi, S.M.A., Nakhaie, M.; Zandi, K. A comprehensive review of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1: an imminent threat at doorstep. Travel medicine and infectious disease 2023, 55, 102638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yon, L.; Duff, J.P.; Ågren, E.O.; Erdélyi, K.; Ferroglio, E.; Godfroid, J. ; .. & Gavier-Widén, D. Recent changes in infectious diseases in European wildlife. Journal of wildlife diseases 2019, 55, 3–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poovorawan, Y.; Pyungporn, S.; Prachayangprecha, S.; Makkoch, J. Global alert to avian influenza virus infection: from H5N1 to H7N9. Pathogens and global health 2013, 107, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhaie, M.; Rukerd, M.R.Z. , Shahpar, A. ; Pardeshenas, M.; Khoshnazar, S.M.; Khazaeli, M.;... & Charostad, J. A Closer Look at the Avian Influenza Virus H7N9: A Calm before the Storm?. Journal of Medical Virology 2024, 96, e70090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinian, S.A.; Hajati, M.H. A comprehensive review of the zoonotic potential of avian influenza viruses: a globally circulating threat to pandemic influenza in human. Journal of Zoonotic Diseases 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasik, B.R.; de Wit, E.; Munster, V.; Lloyd-Smith, J.O.; Martinez-Sobrido, L.; Parrish, C.R. Onward transmission of viruses: how do viruses emerge to cause epidemics after spillover? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2019, 374, 20190017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, A.; Naguib, M.M.; Nogales, A.; Barre, R.S.; Stewart, J.P.; García-Sastre, A.; Martinez-Sobrido, L. Avian influenza A (H5N1) virus in dairy cattle: origin, evolution, and cross-species transmission. Mbio 2024, 15, e02542–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, S. (2017). Avian influenza and co-infections: investigation of the interactions in the poultry models (Doctoral dissertation, Institut National Polytechnique de Toulouse-INPT).

- EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Animal Welfare (AHAW), ECDC, Alvarez, J. ; Boklund, A.; Dippel, S.; Dórea, F.;... & Melidou, A. Preparedness, prevention and control related to zoonotic avian influenza. EFSA Journal 2025, 23, e9191. [CrossRef]

- Redrobe, S.P. Avian influenza H5N1: A review of the current situation and relevance to zoos. International Zoo Yearbook 2007, 41, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charostad, J.; Rukerd, M.R.Z. , Mahmoudvand, S. ; Bashash, D.; Hashemi, S.M.A., Nakhaie, M.; Zandi, K. A comprehensive review of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1: an imminent threat at doorstep. Travel medicine and infectious disease 2023, 55, 102638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Imtiaz, M.A.; Islam, M.M.; Tanzin, A.Z.; Islam, A.; Hassan, M.M. Major bat-borne zoonotic viral epidemics in Asia and Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Veterinary Medicine and Science 2022, 8, 1787–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziosi, G.; Lupini, C.; Catelli, E.; Carnaccini, S. Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5 clade 2. 3. 4.4 b virus infection in birds and mammals. Animals 2024, 14, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacinti, J.A.; Signore, A.V.; Jones, M.E.; Bourque, L.; Lair, S.; Jardine, C. ; .. & Soos, C. Avian influenza viruses in wild birds in Canada following incursions of highly pathogenic H5N1 virus from Eurasia in 2021–2022. Mbio 2024, 15, e03203-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Yin, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z. ; .. & Liu, J. Reassortment with dominant chicken H9N2 influenza virus contributed to the fifth H7N9 virus human epidemic. Journal of virology 2021, 95, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krammer, F.; Hermann, E.; Rasmussen, A.L. Highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1: history, current situation, and outlook. Journal of Virology 2025, 99, e02209-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, C.; Shi, W.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Xu, W. ; .. & Bi, Y. New threats from H7N9 influenza virus: spread and evolution of high-and low-pathogenicity variants with high genomic diversity in wave five. Journal of virology 2018, 92, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, K.K.; Ng, K.H.; Que, T.L.; Chan, J.M.; Tsang, K.Y.; Tsang, A.K. ; .. & Yuen, K.Y. Avian influenza A H5N1 virus: a continuous threat to humans. Emerging microbes & infections 2012, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, T.H.P. , James, J. ; Sealy, J.E.; Iqbal, M. A global perspective on H9N2 avian influenza virus. Viruses 2019, 11, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkie, T.N.; Byrne, A.M.; Jones, M.E.; Mollett, B.C.; Bourque, L.; Lung, O. ; .. & Berhane, Y. Recurring trans-Atlantic incursion of clade 2.3. 4.4 b H5N1 viruses by long distance migratory birds from Northern Europe to Canada in 2022/2023. Viruses 2023, 15, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feoktistova, S.G.; Ivanova, A.O.; Degtyarev, E.P.; Smirnova, D.I.; Volchkov, P.Y.; Deviatkin, A.A. Phylogenetic Insights into H7Nx Influenza Viruses: Uncovering Reassortment Patterns and Geographic Variability. Viruses 2024, 16, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, M.A.; Hassan, A.; Aman, M.; Gul, I.; Mir, A.H.; Potdar, V. ; Molecular and ecological determinants of mammalian adaptability in avian influenza virus. Infection 2025, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lei, Z. The alarming situation of highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses in 2019–2023. Global Medical Genetics 2024, 11, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Shan, N.; Wang, X.; Lin, S.; Ma, K. ; & Qi, W. Genetic diversity, phylogeography, and evolutionary dynamics of highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N6) viruses. Virus Evolution 2020, 6, veaa079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilyicheva, T.N.; Netesov, S.V.; Gureyev, V.N. COVID-19, Influenza, and Other Acute Respiratory Viral Infections: Etiology, Immunopathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Part I. COVID-19 and Influenza. Molecular genetics, microbiology and virology 2022, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranda, A.J.; Aguilar-Tipacamú, G.; Perez, D.R.; Bañuelos-Hernandez, B.; Girgis, G.; Hernandez-Velasco, X. ; .. & Petrone-Garcia, V.M. Emergence, migration and spreading of the high pathogenicity avian influenza virus H5NX of the Gs/Gd lineage into America. Journal of General Virology 2025, 106, 002081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suntronwong, N. (2020). Identification of genetic and antigenic variation and evolution pattern among influenza a and b viruses in Thailand. [CrossRef]

- Altan, E.; Avelin, V.; Aaltonen, K.; Korhonen, E.; Laine, L.; Lindh, E. ; .. & Österlund, P. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) H5N1 virus in Finland in 2021–2023–Genetic diversity of the viruses and infection kinetics in human dendritic cells. Emerging microbes & infections 2025, 14, 2447618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, T. C. The Pandemic Threat of Emerging H5 and H7 Avian Influenza Viruses. Viruses 2018, 10, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charostad, J.; Rukerd, M.R.Z. , Mahmoudvand, S. ; Bashash, D.; Hashemi, S.M.A., Nakhaie, M.; Zandi, K. A comprehensive review of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1: an imminent threat at doorstep. Travel medicine and infectious disease 2023, 55, 102638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.J.; Xiao, H.; Dai, L.; Liu, D.; Chen, J.; Qi, X. ; .. & Liu, Y. Avian influenza A (H7N9) virus: from low pathogenic to highly pathogenic. Frontiers of medicine 2021, 15, 507–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu Thakur, P.; Bullock, H.A.; Stevens, J.; Kumar, A.; Maines, T.R.; Belser, J.A. Heterogeneity across mammalian-and avian-origin A (H1N1) influenza viruses influences viral infectivity following incubation with host bacteria from the human respiratory tract. bioRxiv 2025, 2025–03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jallow, M.M.; Diagne, M.M.; Ndione, M.H.D. , Barry, M. A.; Ndiaye, N.K.; Kiori, D.E.;... & Dia, N. Genetic and Molecular Characterization of Avian Influenza A (H9N2) Viruses from Live Bird Markets (LBM) in Senegal. Viruses 2025, 17, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, X.; Kong, Y. ; .. & Gao, Y. Amino acid sites related to the PB2 subunits of IDV affect polymerase activity. Virology Journal 2021, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisset, A.T.; Hoyne, G.F. Evolution and adaptation of the avian H7N9 virus into the human host. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Guo, J.; Li, L.; Chang, C.; Li, Y. ; .. & Sun, B. The PB2 E627K mutation contributes to the high polymerase activity and enhanced replication of H7N9 influenza virus. Journal of General Virology 2014, 95, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, U.; Su, Y.C.; Vijaykrishna, D.; Smith, G.J. The ecology and adaptive evolution of influenza A interspecies transmission. Influenza and other respiratory viruses 2017, 11, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhu, S.; Govinden, R.; Chenia, H.Y. Multiple vaccines and strategies for pandemic preparedness of avian influenza virus. Viruses 2023, 15, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saenz, H.S.C. , & Liliana, C.A. Preventive, safety and control measures against Avian Influenza A (H5N1) in occupationally exposed groups: A scoping review. One Health 2024, 100766. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, C.E.; Legge, K.L. Influenza A virus vaccination: immunity, protection, and recent advances toward a universal vaccine. Vaccines 2020, 8, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.H.; Erazo, E.M.; Ishcol, M.R.C. , Lin, C. Y.; Assavalapsakul, W.; Thitithanyanont, A.; Wang, S.F. Virus-induced pathogenesis, vaccine development, and diagnosis of novel H7N9 avian influenza A virus in humans: a systemic literature review. Journal of International Medical Research 2020, 48, 0300060519845488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, N.; Yu, Z.; Pan, H.; Chan, T.C. ; .. & Liu, S.L. Comparative epidemiology of human fatal infections with novel, high (H5N6 and H5N1) and low (H7N9 and H9N2) pathogenicity avian influenza A virus. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2017, 14, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krammer, F.; Hermann, E.; Rasmussen, A.L. Highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1: history, current situation, and outlook. Journal of Virology 2025, 99, e02209–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Facciuolo, A.; Aubrey, L.; Barron-Castillo, U.; Berube, N.; Norleen, C. ;... & Warner, B. (2024). Highly pathogenic avian influenza virus H5N1 infection in dairy cows confers protective immunity against reinfection. [CrossRef]

- Karimian, P.E.G.A.H. , & Delavar, M. A. Comparative study of clinical symptoms, laboratory results and imaging features of coronavirus and influenza virus, including similarities and differences of their pathogenesis. Pak. J. Med. Health Sci 2020, 14, 1405–1411. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Wong, G.; Yang, L.; Tan, S.; Li, J.; Bai, B. ; .. & Gao, G.F. Comparison between human infections caused by highly and low pathogenic H7N9 avian influenza viruses in Wave Five: Clinical and virological findings. Journal of Infection 2019, 78, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakhaie, M.; Rukerd, M.R.Z. , Shahpar, A.; Pardeshenas, M., Khoshnazar, S.M., Khazaeli, M., Eds.; ... & Charostad, J. (2024). A Closer Look at the Avian Influenza Virus H7N9: A Calm before the Storm? Journal of Medical Virology, 96, e70090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Reinhart, K.; Couture, A.; Kniss, K.; Davis, C.T.; Kirby, M.K. ; .. & Olsen, S.J. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) virus infections in humans. New England Journal of Medicine 2025, 392, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.; Poorvi, Y.R.G. , Pandey, A.; Paul, E.K., Singh, K., Eds.; Paul, R. Avian Influenza: A Comprehensive Systematic Review of Epidemiology, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnostic Approaches, Prevention Strategies, Recent Outbreaks and Global Collaboration. REDVET-Revista electrónica de Veterinaria, 25(1S), 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Raza, M.A.; Ashraf, M.A.; Amjad, M.N.; Din, G.U.; Shen, B.; Hu, Y. The peculiar characteristics and advancement in diagnostic methodologies of influenza A virus. Frontiers in Microbiology 2025, 15, 1435384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldock, J.; Remarque, E.J.; Zheng, L.; Ho, S.; Hoschler, K.; Neumann, B. ; .. & FLUCOP consortium. Haemagglutination inhibition and virus microneutralisation serology assays: Use of harmonised protocols and biological standards in seasonal influenza serology testing and their impact on inter-laboratory variation and assay correlation: A FLUCOP collaborative study. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 14, 1155552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeley, C.R.; Peiris, J.S.M. Methods in virus diagnosis: immunofluorescence revisited. Journal of clinical virology 2002, 25, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisfeld, A.J.; Neumann, G.; Kawaoka, Y. Influenza A virus isolation, culture and identification. Nature protocols 2014, 9, 2663–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemula, S.V.; Zhao, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Biswas, S.; Hewlett, I. Current approaches for diagnosis of influenza virus infections in humans. Viruses 2016, 8, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wong, G.; Yang, L.; Tan, S.; Li, J.; Bai, B. ; .. & Gao, G.F. Comparison between human infections caused by highly and low pathogenic H7N9 avian influenza viruses in Wave Five: Clinical and virological findings. Journal of Infection 2019, 78, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassetti, M.; Sepulcri, C.; Giacobbe, D.R.; Fusco, L. Treating influenza with neuraminidase inhibitors: an update of the literature. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 2024, 25, 1163–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhaeefi, M.; Rungkitwattanakul, D.; Saltani, I.; Muirhead, A.; Ruehman, A.J.; Hawkins, W.A.; Daftary, M.N. Update and narrative review of avian influenza (H5N1) infection in adult patients. Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy 2024, 44, 870–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smyk, J.M.; Szydłowska, N.; Szulc, W.; Majewska, A. Evolution of influenza viruses—drug resistance, treatment options, and prospects. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 12244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, Y.; Liu, S. Emerging antiviral therapies and drugs for the treatment of influenza. Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs 2022, 27, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialy, D.; Shelton, H. Functional neuraminidase inhibitor resistance motifs in avian influenza A (H5Nx) viruses. Antiviral Research 2020, 182, 104886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, G.; Yu, J.; Li, G. Novel and alternative therapeutic strategies for controlling avian viral infectious diseases: Focus on infectious bronchitis and avian influenza. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2022, 9, 933274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meseko, C.; Sanicas, M.; Asha, K.; Sulaiman, L.; Kumar, B. Antiviral options and therapeutics against influenza: history, latest developments and future prospects. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2023, 13, 1269344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, L.; Farkas, M.; Dobra, P.F.; Lennon, G.; Könyves, L.P.; Rusvai, M. Avian Influenza Clade 2. 3. 4.4 b: Global Impact and Summary Analysis of Vaccine Trials. Vaccines 2025, 13, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astill, J.; Dara, R.A.; Fraser, E.D.; Sharif, S. Detecting and predicting emerging disease in poultry with the implementation of new technologies and big data: A focus on avian influenza virus. Frontiers in veterinary science 2018, 5, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-Roa, C.; Nelson, M.I.; Ariyama, N.; Aguayo, C.; Almonacid, L.I.; Munoz, G. ;... & Neira, V. (2023). Cross-species transmission and PB2 mammalian adaptations of highly pathogenic avian influenza A/H5N1 viruses in Chile. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Li, C.; Ren, R.; Bai, W.; Zhou, L. An overview of avian influenza surveillance strategies and modes. Science in One Health 2023, 2, 100043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrillo, M.; Buttinger, G.; Corbisier, P.; Leoni, G.; Paracchini, V.; Lambrecht, B. ; .. & Marchini, A. In silico design and preliminary evaluation of RT-PCR assays for A (H5N1) bird flu. Nature 2024, 628, 484–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.W.; Wang, S.F. The effects of genetic variation on H7N9 avian influenza virus pathogenicity. Viruses 2020, 12, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Lai, S.; Yang, J.; Cowling, B.J. ; .. & Yu, H. Serological evidence of human infections with highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) virus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC medicine 2020, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, J.H.; Fouchier, R.A.; Lewis, N. Highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses at the wild–domestic bird interface in Europe: future directions for research and surveillance. Viruses 2021, 13, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwhab, E.M.; Hafez, H.M. Insight into alternative approaches for control of avian influenza in poultry, with emphasis on highly pathogenic H5N1. Viruses 2012, 4, 3179–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, K.E. Personal Protective Equipment Use by Dairy Farmworkers Exposed to Cows Infected with Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Viruses—Colorado, 2024. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2024, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.; Tian, G.; Shi, J.; Deng, G.; Li, C.; Chen, H. Vaccination of poultry successfully eliminated human infection with H7N9 virus in China. Science China Life Sciences 2018, 61, 1465–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Focosi, D.; Maggi, F. Avian influenza virus A (H5Nx) and prepandemic candidate vaccines: state of the art. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 8550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Acle, T.; Ravello, C.; Rosemblatt, M. (2024). Are we cultivating the perfect storm for a human avian influenza pandemic? Biological Research, 57, 96. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, O. (2019). How decision makers can use quantitative approaches to guide outbreak responses. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 374, 20180365. [CrossRef]

- Owusu, H.; Sanad, Y.M. Comprehensive Insights into Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 in Dairy Cattle: Transmission Dynamics, Milk-Borne Risks, Public Health Implications, Biosecurity Recommendations, and One Health Strategies for Outbreak Control. Pathogens 2025, 14, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhagat, P.; Coan, J.; Ganguly, A.; Puetz, C.; Silvestri, D.; Madad, S. Enhancing healthcare preparedness: Lessons from a tabletop exercise on Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI). Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 2025, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musa, E.; Nia, Z.M.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Leung, D.; Lee, N.; Kong, J.D. (2024, October). Avian Influenza: Lessons from Past Outbreaks and an Inventory of Data Sources, Mathematical and AI Models, and Early Warning Systems for Forecasting and Hotspot Detection to Tackle Ongoing Outbreaks. In Healthcare (Vol. 12, No. 19, p. 1959). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Tang, S.; Jin, Z.; Xiao, Y. Identifying risk factors of A (H7N9) outbreak by wavelet analysis and generalized estimating equation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cargnin Faccin, F.; Perez, D.R. Pandemic preparedness through vaccine development for avian influenza viruses. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2024, 20, 2347019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Fan, M. Reaction–advection–diffusion model of highly pathogenic avian influenza with behavior of migratory wild birds. Journal of Mathematical Biology 2025, 90, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubareka, S.; Amuasi, J.; Banerjee, A.; Carabin, H.; Copper Jack, J.; Jardine, C. ; .. & Jane Parmley, E. Strengthening a One Health approach to emerging zoonoses. Facets 2023, 8, 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sreenivasan, C.C.; Li, F.; Wang, D. Emerging Threats of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A (H5N1) in US Dairy Cattle: Understanding Cross-Species Transmission Dynamics in Mammalian Hosts. Viruses 2024, 16, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhagat, P.; Coan, J.; Ganguly, A.; Puetz, C.; Silvestri, D.; Madad, S. Enhancing healthcare preparedness: Lessons from a tabletop exercise on Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI). Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 2025, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Virus Subtype | Year(s) | Region/Country | Major Events & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| H5N1 | 1997 | Hong Kong (SAR) | First human outbreak (Clade 0) |

| 2003 onwards | SE Asia (Vietnam, Laos, Thailand), China | Widespread outbreaks (Clade 1) | |

| 2005–2006 | Asia, Europe, Africa | Intercontinental spread (Clade 2.2) | |

| 2014–2015 | China, Korea, USA, Europe | H5N8 spread (Clade 2.3.4.4a) | |

| 2016–2017 | Global | H5Ny emergence (Clade 2.3.4.4b) | |

| 2020–2021 | Europe, Asia, Africa | Novel H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b wave | |

| Late 2021–ongoing | North America | Mass poultry/mammal outbreaks | |

| Late 2022–ongoing | Mexico, Central & South America | Spread of clade 2.3.4.4b | |

| 2023 | Europe (Poland, Spain, Finland) | Infections in cats, mammals | |

| 2024–ongoing | USA (Dairy cattle), Global | Dairy cattle infection, continued wild bird circulation | |

| H7N9 | 2013–2017 | China | Five epidemic waves, LPM interventions successful |

| 2003 | Netherlands | H7N7 outbreak (human infections) | |

| 2019 | Cambodia | Emergence of H7N4 | |

| H9N2 | 1998–ongoing | China, Egypt, Pakistan, Oman | Endemic poultry infection; mild human disease |

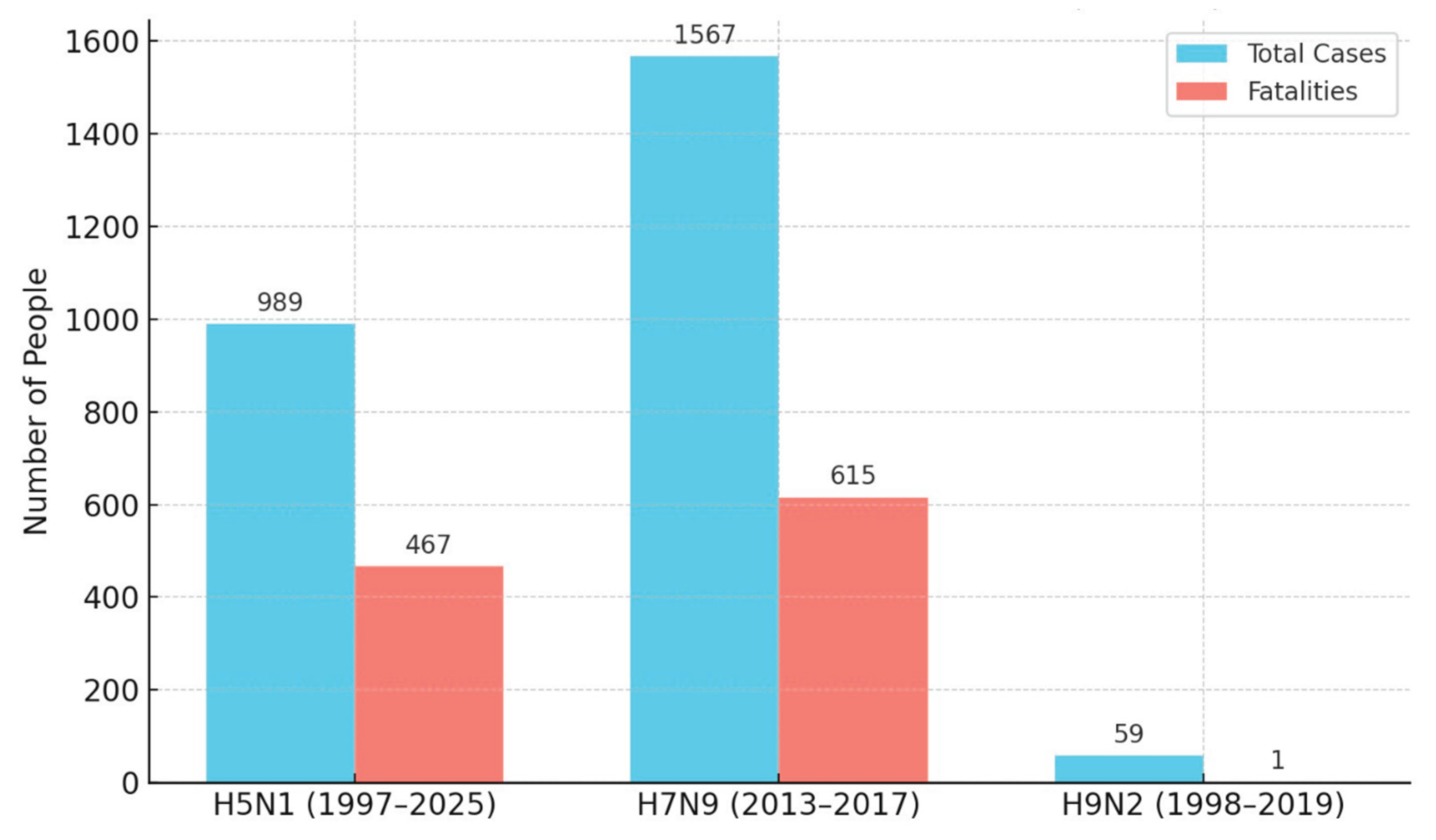

| Virus Subtype | Year Range | Total Cases | Fatalities | Case Fatality Rate (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H5N1 | 1997 | 18 | 6 | 33.3% | First human cases (Hong Kong) |

| 2003 | 3 | 2 | 66.7% | Re-emergence in Asia | |

| 2004 | 46 | 32 | 69.6% | Vietnam, Thailand, others | |

| 2003–July 14, 2023 | 878 | 458 | 52.16% | WHO cumulative reports | |

| March–October 2024 (USA) | 46 | Not specified | Not specified | Exposure to cows and poultry | |

| Since 1997–December 11, 2024 | 974 | 464 | 47.6%* | WHO cumulative reports | |

| Since 1997–March 7, 2025 | 989 | 467 | 47.2%* | Updated data | |

| H7N9 | March–May 2013 (China) | 130 | ≥27 | 20% | First wave |

| Since 2013 (China, five waves) | 1567 | 615 | 39.2% | Five epidemic waves | |

| H9N2 | 1998–2019 | 59 | 1 | 1.7% | Mild infections |

| Viral Protein/Gene | H5N1 Mutation(s) | H7N9 Mutation(s) | Functional Impact |

| Genome | Segmented, negative single-stranded RNA, 8 segments. Encodes at least 11 proteins | Segmented, negative single-stranded RNA, 8 segments. Encodes at least 11 proteins. | Basic structure of Influenza A viruses. HA and NA determine subtype. High mutation rate in HA and NA. |

| Hemagglutinin (HA) | L129V, S589, S582, S512, S541, L515, L52, L569, L55 (amino acid changes in human isolates, frequencies vary by region). HA gene conservation high (98.3-99.9% similarity in Finnish isolates compared to European). Mutations related to human receptor specificity. HA T108I, S123P, S133A, K218Q, S223R, 327-328del/328del in US/Cambodian 2024/2025 cases [45a, 45b, 45c]. | Acquisition of polybasic amino acids at cleavage site (e.g., PKRKRTA(R/G), PKGKRTA(R/G), PKGKRIA(R/G)). Mutations related to avian-to-human receptor-binding adaptation. | HA binds to host cell receptors. HA cleavage site determines pathogenicity (LP vs HP). Mutations can affect receptor binding and stability. Key determinant of host range. |

| Neuraminidase (NA) | NA H155Y, T365I, N366S found in Finnish isolates. | [Specific mutations listed in sources not available in excerpts]. | NA cleaves sialic acid receptors (facilitates virus release - information not explicitly from sources, but common knowledge about NA function). Amino acid substitutions can affect inhibition by neuraminidase inhibitors. |

| Polymerase basic 2 (PB2) | PB2 K389R, V598T, E627K, G309D found in Finnish isolates. E627K mutation detected in clade 2.3.4.4b H5N1 associated with enhanced mammalian replication (mentioned in conclusion thought process). | Amino acid substitutions can contribute to pathogenicity in mammalian hosts. | Part of the polymerase complex (PA, PB1, PB2) that orchestrates transcription and replication. PB2 E627K is a known adaptation to mammalian hosts. |

| Nucleoprotein (NP) | NP V33I, Y52N, I109V found in Finnish isolates. | [Specific mutations listed in sources not available in excerpts]. | Part of the viral ribonucleoprotein (vRNP), involved in genome encapsidation. |

| Matrix protein 1 (M1) | M1 N30D found in Finnish isolates. | [Specific mutations listed in sources not available in excerpts]. | Found inside the lipid envelope. Involved in viral lifecycle. |

| Nonstructural protein 1 (NS1) | NS1 P3S, R41K, K55E, D70G found in Finnish isolates. | [Specific mutations listed in sources not available in excerpts]. | Non-structural/regulatory protein. Involved in viral lifecycle. |

| Feature | H5N1 | H7N9 | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severity | Severe; high mortality | Severe; emerged high pathogenicity in wave 5 | Both associated with ARDS, pneumonia |

| Common Symptoms | Respiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms, elevated aminotransferase | Respiratory symptoms; some GI involvement | Symptoms overlap but vary |

| Age Distribution | Median 18 years (USA 2024: adults) | Median 63 years | H9N2 mainly affects young children |

| Sex Ratio (M:F) | 1:1.19 | 1:0.45 (male predominance) | Differences in susceptibility noted |

| Coexisting Conditions | Rare | Common (elderly, hypertension, diabetes) | Underlying conditions worsen outcomes in H7N9 |

| Transmission | Primarily animal-to-human | Primarily animal-to-human (live bird markets) | Human-to-human transmission rare |

| Antiviral Sensitivity | Sensitive to NA inhibitors | Sensitive to NA inhibitors | Treatment feasible with neuraminidase inhibitors |

| Complications | CNS involvement, multi-organ failure | Nosocomial infections, elevated Angiotensin II | Severe systemic complications in both |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).