1. Introduction

The prediction of student academic performance has become increasingly important in educational research due to its significance of the improving student outcome and institutional effectiveness. The early identification of risk students gives educational institutions the chance to offer timely and effective intervention strategies, which in turn are able to improve retention rates and overall academic achievements significantly [

1,

2]. With the growing amount of data in education, machine learning (ML) methods are recognized as appropriate tools for the analysis of complex data patterns and getting accurate predictions [

3,

4] In the last years, deep learning, an area of ML, has outperformed in the field of a big complex dataset with higher dimensions [

5]. Neural networks, a kind of deep learning model, have shown exceptional performance in applying various analytics tasks including educational settings [

6,

7]. Although the proven benefits, deep learning techniques that have been used in predicting student academic performance have not been much explored in contrast to conventional ML methods, such as decision trees, support vector machines, and ensemble approaches [

8,

9]. In this specific study, filling this gap using a robust predictive model based on the feedforward neural network, which has been implemented through the PyTorch framework known for its flexibility and computational efficiency [

10]. The research project utilizes the UCI Student Performance dataset containing the demographic, academic, and behavioral indicators. A proper application of preprocessing techniques like categorical encoding and feature scaling to optimize data representation for neural networks was carried out [

11,

12]. Issues with data security, and student privacy, and the confidentiality of personal data, and the concerns in the data-driven educational systems regarding the security of such systems have received increased emphasis [

13]. Therefore, this study interlinks safety measures like data encryption and security protocols to handle data carefully, addressing the main data protection requirements in educational analytics.

This paper induces significant data mining in education by pointing out the efficiency of deep learning as the model of choice for student performance prediction, conducting a thorough evaluation of model performance, and suggesting realistic steps for model improvement and its secure use. The results are illustrative of the predictive potential of deep learning and its role in promoting proactive student success initiatives.

2. Literature Review

Over the past few years, the field of student academic performance prediction has undergone a paradigm shift. It has gone from being the subject of traditional statistical methods to the focus of research on sophisticated machine learning and deep learning methods. In the beginning, the prevalent research approach was to use regression analysis and other simple statistical procedures to find relationships between demographic or behavioral variables [

14,

15]. The estimated models were the first to show that the correlations existed but could not account for the complexity of relationships between a number of learning variables. Thanks to the increased computing power and availability of data, traditional machine learning approaches gained ground. Decision trees and random forests are for example extensively employed due to their interpretability and accuracy in capturing the nonlinear relationships within the educational dataset [

8]. Besides, linear SVM and logistic regression have been also widely implemented, offering robust results in classification depictions associated with a student’s outcome (Costa et al., 2017). While the random forest method is the most popular, it is also the gradient boosting technique that accomplishes the best results despite the combination of predictions with weak learners [

9].

Even though ML was a good option, the current findings of research have pointed out that using deep learning methods is the better way when it comes to dealing with complex high-dimensional datasets that are commonly found in educational settings. The exception in performance has been neural networks, especially shallow feedforward and recurrent neural networks (RNN) that have reached levels of excellence in capturing temporally and spatially complicated patterns in the data [

5]. In this case, RNNs and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks performed well due to their ability to learn sequentially from different types of course logs and online activity patterns [

16].

The use of DL in structured educational data application (demo, academic, and behavioral features) has been very little. However, the studies affirm the high possibilities they carry while outlining the challenges which revolve around data cleansing, optimizing models, and interpretation of the findings [

6,

7]. Frameworks such as PyTorch can help the most as they provide flexibility and computational benefits, yet their application in the educational data mining field necessitates further investigation [

10].

Moreover, as educational institutions embrace more data-driven decision-making, privacy issues related to sensitive student data have come up as a vital concern. Research advocates for the establishment of strong security measures, which include the use of encryption and secure data management protocols, in order to ensure the privacy of students and meet the legal requirements [

13].

In line with this, the current research introduces the notable gaps visible in the literature by adopting a detailed DL approach for student performance prediction, utilizing PyTorch because of its flexibility and efficiency, and specifically integrating security features into the model development and deployment process. This methodology intends to broaden the impact of educational analytics and to assist explicitly in coming up with more proactive student success programming.

3. Data Preprocessing

This work has investigated the publicly procured Student Performance dataset obtainable from the UCI (University of California Irvine) Machine Learning Repository, a benchmark dataset sanctioned in educational analytics [

17]. The assorted dataset includes demographic, behavioral, and academic features collected from the students of secondary education who signed up for Mathematics and Portuguese language courses. The full dataset holds 33 different attributes representing varying details of student life, family background, academic history and at last performance indicators. The variable to be predicted in this study among students’ performance was the final academic grade, expressed as ‘G3’ ranging from 0 to 20. The dataset featured a total of 395 students and provided a diverse enough sample for predictive modeling. Among the primary demographic characteristics are gender, age, family size and the level of parental education. Academic and behavioral related variables consist of study time, previous failures, class absences, participation in extracurricular activities, and alcohol consumption. The abundance of different variables for the prediction power are allowed by these complex and feature rich data, depreciation, for example, of the reasons that lead to poor student performance [

18,

19].

The preprocessing stage was of pivotal importance in making the data suitable for neural network modeling. At the fruitful time, exploratory data analysis was carried out to have information about both the distribution of the data and missing or inconsistent values. After the dataset was identified to be free of critical missingness, the preprocessing phase continued with the transformation of categorical variables to a numeric representation suitable for machine learning algorithms. This process was based on one-hot encoding, the categorization method that captures categorical distinctions effectively without the imposition of unintended ordinal relationships [

11,

12].

Once the categorical encoding was performed, numerical features were standardized using Z-score normalization which is necessary because of the widespread disparities in the scales of some attributes such as age, absences, and previous grades. Standardization is recognized to improve the convergence during the neural network training as it ensures that every numeric feature contributes equally to the learning process and thus, helps the model to generalize well on unseen data [

13,

20].

Following the steps of encoding and standardization, the dataset was split into training and test subsets where 80% of data were allocated for training and the remaining 20% was kept aside for verifying the model. The training and test set included 316 and 79 records respectively, hence it can be said that the examples for both learning the model and reliable evaluation are sufficient. This particular data split is an established protocol in machine learning research that allows the neural network model to be validated with robustness and its prediction accuracy and generalization power properly checked [

21].

In addition, acknowledging the sensitivity and confidentiality inherent to educational data, the preprocessing phase was designed with rigorous security measures. The Data encryption techniques, e.g., secure symmetric encryption standards, were employed to protect the dataset during storage as well as processing. There was strict control over access to the preprocessed dataset that was enforced by role-based access control, in accordance with the best practices of secure data handling in educational analytics environments [

13,

22].

Overall, the thorough and careful preprocessing of the dataset was an integral part of this work, it primarily influenced the efficiency of the neural net by the constant training of predictions. With the careful transformation of the features, normalization as well as secure management of the data, the study was able to format the data the best for deep learning, thus making the procedures of model training and evaluation possible, efficient, and secure.

4. Methodology

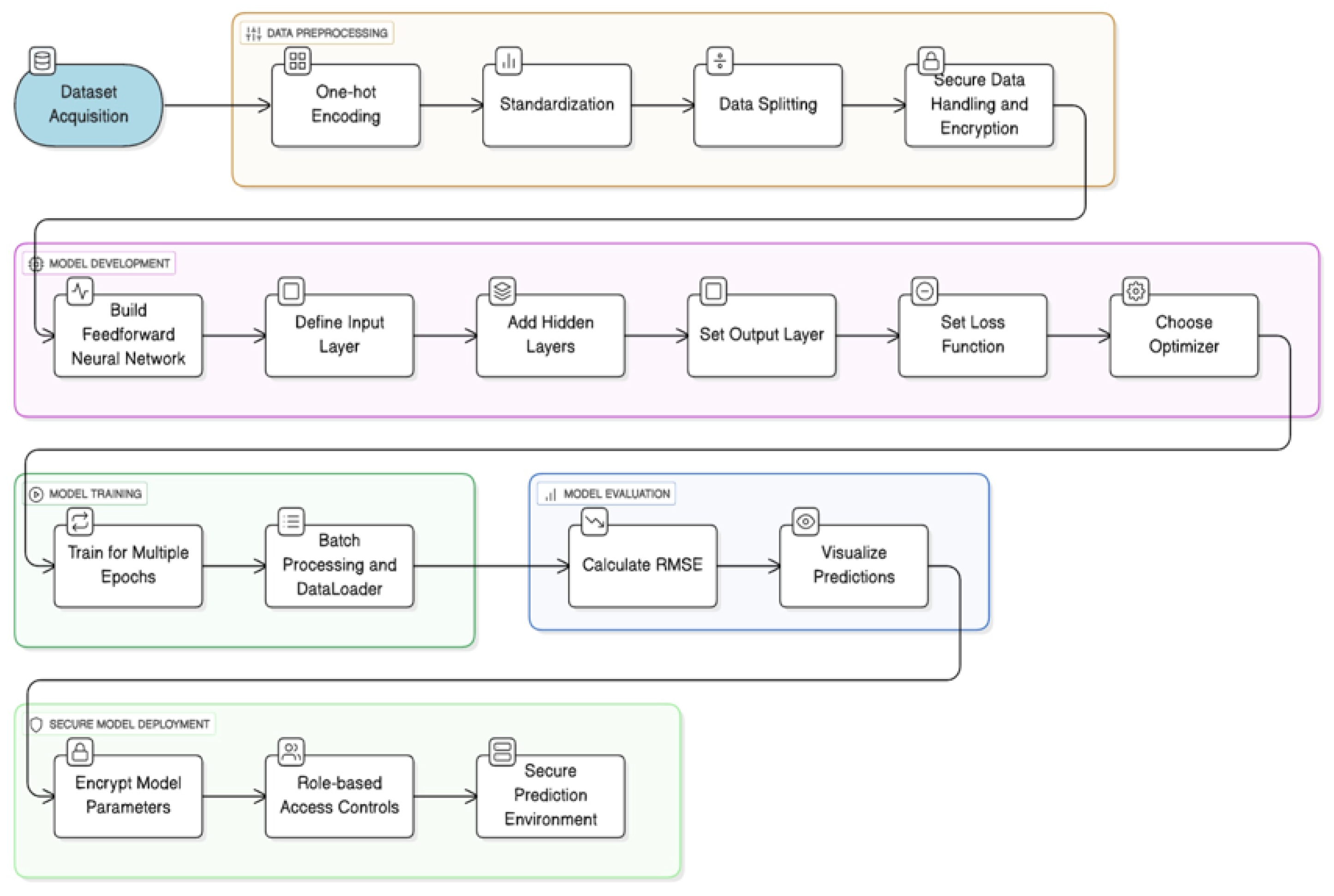

In this research, a systematic method based on cutting-edge deep learning techniques was employed to predict the academic performance of students. This research deals with the application of a systematic method based on deep learning techniques to the task of predicting students’ academic performance and, in particular, forecasting the final grades of students using a feedforward neural network that was developed in PyTorch. The approach consists of a sequence of stages, including data preprocessing, model development, training procedures, and performance evaluation.

The initial step, as mentioned before, was the execution of an all-around data preprocessing phase on the UCI Student Performance dataset [

17]. That involved changing categorical variables into one-hot encoding, Z-score normalization of numerical features involving scaling, and lastly, partitioning the dataset into training and testing subsets with an 80:20 split [

20]. In addition, various security protocols, such as data encryption and role-based access controls, were implemented during the preprocessing phase to secure the confidentiality and integrity of sensitive student information [

13].

Next step, after data preprocessing was the design of the neural network architecture. Considering the structured nature of the dataset and the predictive regression task, a fully connected feedforward neural network was chosen due to it being the most effective option for modeling the complex nonlinear relationships [

21]. The network architecture comprised three layers: the input layer had the same number of preprocessed features, which were a total of 58 features after encoding and scaling, and the two hidden layers contained respectively 64 and 32 neurons, whereas the last output layer with a single neuron is to produce the continuous target value that is the final student grade. The hidden layers applied the activation function of Rectified Linear Units (ReLU) that are efficient in handling the problem of vanishing gradients, thus enabling more effective training [

23].

To ensure efficient training of the model, Mean Squared Error (MSE) was used as a loss function, which is the common and broadly accepted metric for regression-based deep learning tasks and evaluates the average squared differences between the predicted and actual grades [

11]. Adam, the adaptive moment estimation optimizer was utilized for optimization, this is due to its track-record for the best performance across various deep learning situations as it has the ability to adaptively change the learning rates during the training phase [

24]. The training, which was free from significant overfitting, was carried out for 50 epochs, thus, providing enough time for the model to converge.

The implementation of the model and the training process were performed by means of PyTorch, which is a widely used deep learning library due to its flexibility, ease of use, and dynamic computation graphs which makes it particularly suitable for quick experimenting and deploying of neural networks [

10]. Throughout the training phase, data was loaded and processed in a swift manner by employing the PyTorch built-in DataLoader and custom Dataset classes which provided batching, shuffling facilities, and a coherent memory management.

After training, the performance of the neural network was evaluated both quantitatively and qualitatively. The quantitative evaluation relied on the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) that was computed on the test dataset, which was not seen previously, in order to assess the generalization accuracy. Moreover, a scatter plot that demonstrated the correlation between the predicted and actual grades was generated in order to visualize model performance intuitively and to discover potential prediction biases or systematic errors.

Last but not least, the methodology explicitly included security considerations for the deployment and inference phases. The model parameters trained were securely stored with encryption standards, and model and data access were restrained only to the personnel with appropriate rights through robust access management procedures. The holistic integration of security measures at each step of the methodology is a novel and crucial feature in applying deep learning in educational environments.

Figure 1.

Methodology for Predicting Student Performance Using Deep Learning.

Figure 1.

Methodology for Predicting Student Performance Using Deep Learning.

5. Results

The proposed deep learning model, besides being revamped, also went through a series of tests to ascertain its competency in projecting students’ ultimate results (G3) with predictive measures and visual analytics. The model was assessed using preprocessing and training, which resulted in a Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) of around 2.49 on the test set, thus showing a relatively low error in predicting final scores on a scale from 0 to 20.

To ensure better clarity about the model’s work, various visualizations were created:

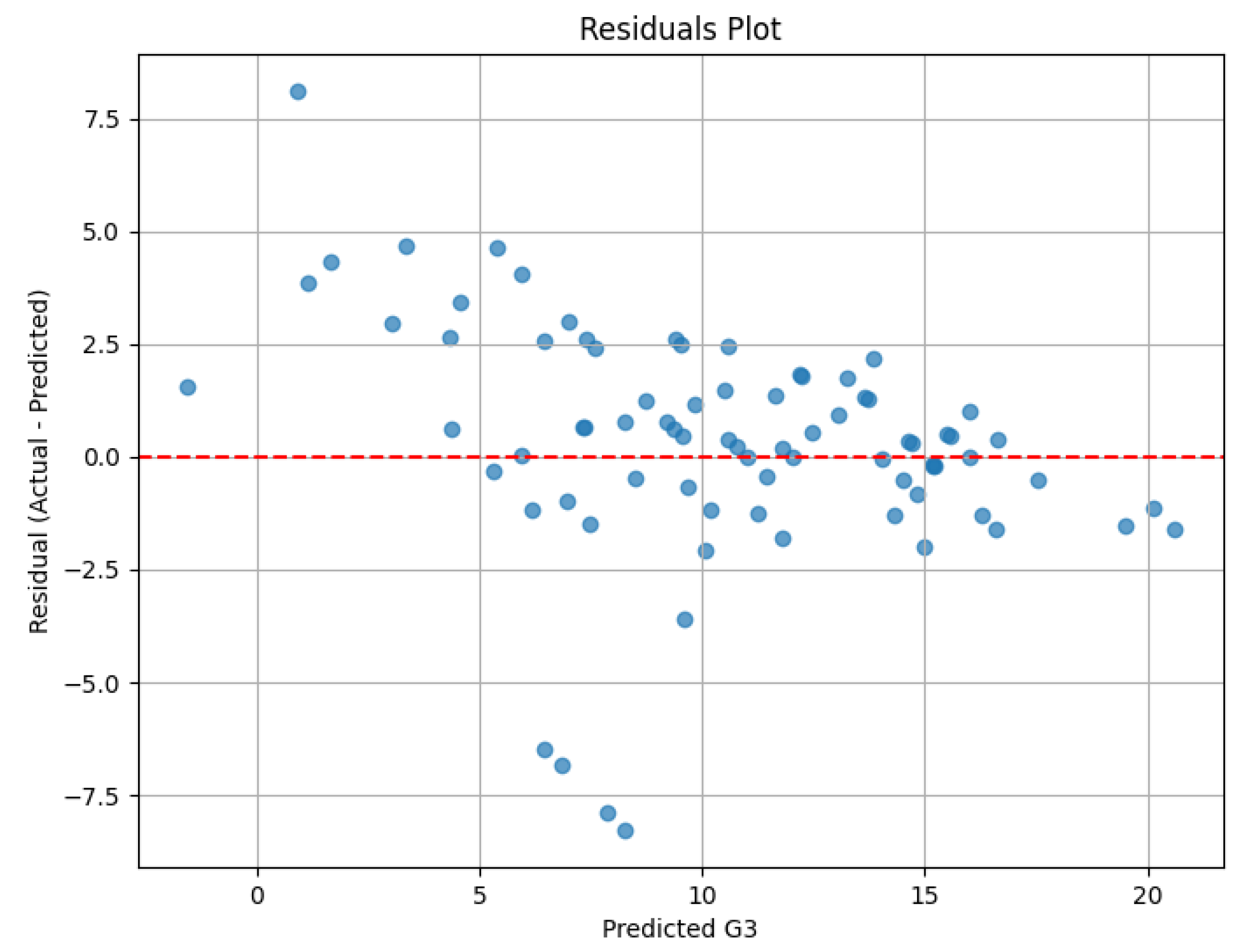

A scatter plot (

Figure 2) that juxtaposes the predicted G3 grades with the actual outcomes is used for this purpose. The major part of the points follows closely the diagonal reference line (y = x); thus, the model is said to be successful in capturing the trends in the plaid. Deviations from the line, which are basically errors of prediction, were mostly between ±3 points, a reasonable range at the very least.

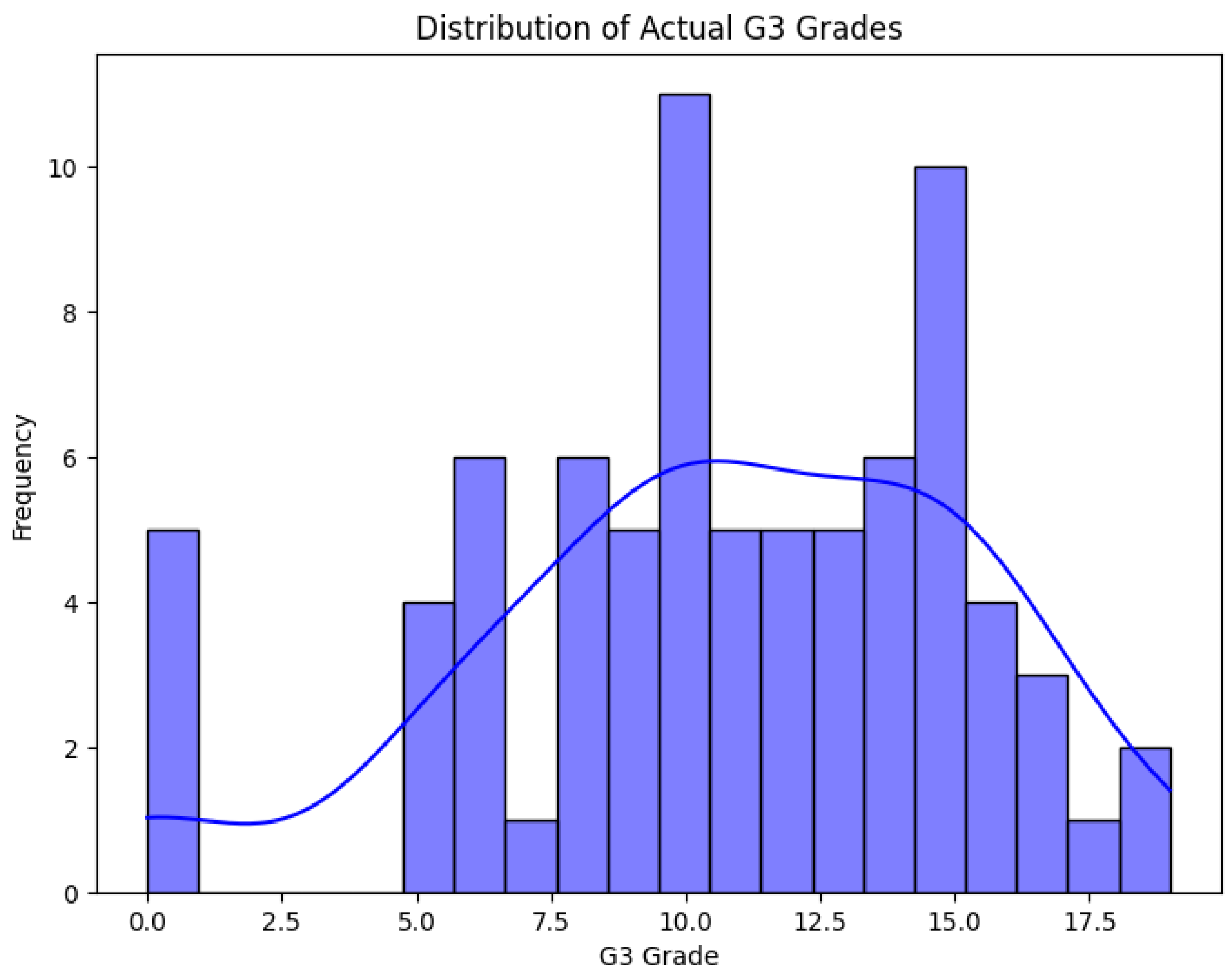

The picture showing in

Figure 3, the grades as histogram reveals a slight mid-range shift with the largest number of grades lying in the 10-15 range. This distribution is a good representation of the dataset’s central tendency in academic performance.

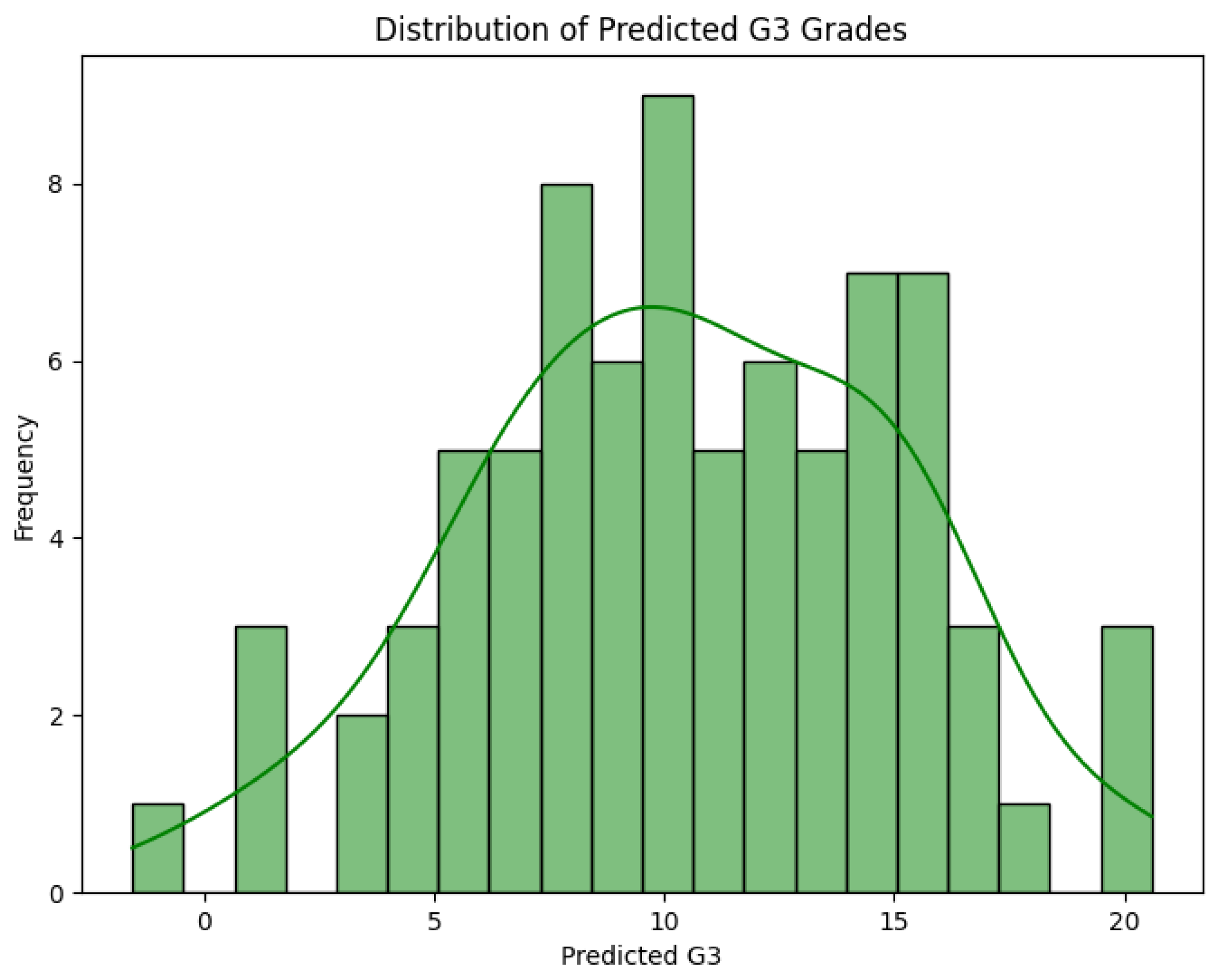

In

Figure 4, predicted grades yield a distribution aligned with the actual values, thereby substantiating the measure of the model carried out by the algorithm. The regression effect causes a slight discrepancy but the model effectively retains the distribution shape.

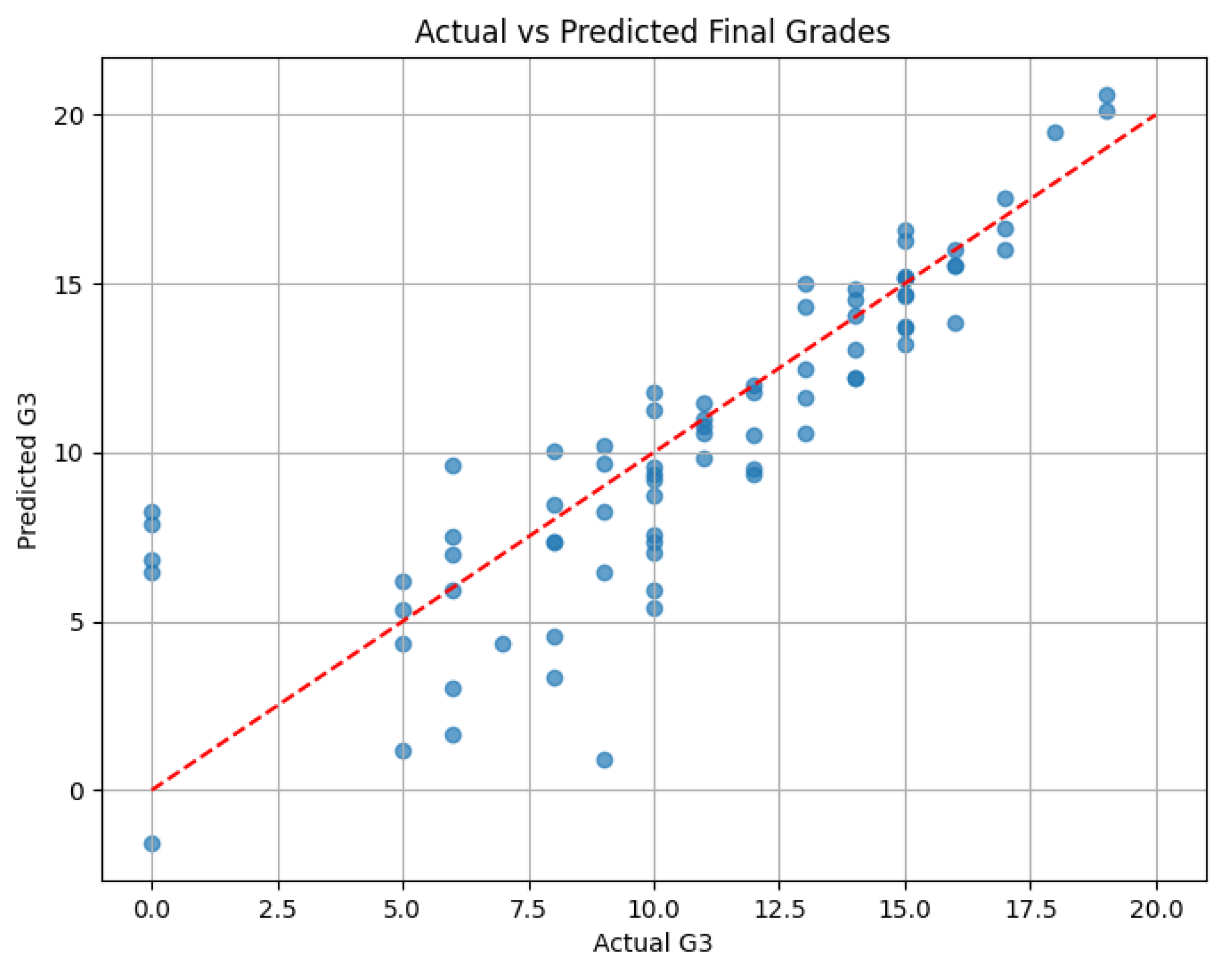

Figure 5.

Residual Error Distribution.

Figure 5.

Residual Error Distribution.

The calculation of residuals, obtained from the actual and predicted G3 values, was used to plot the bias and consistency chart. The distribution centers around zero and is symmetrical showing that the model neither consistently over- nor under-predicts. Most of the residuals stay inside the limit of ±2 points, which verifies the low RMSE mentioned earlier.

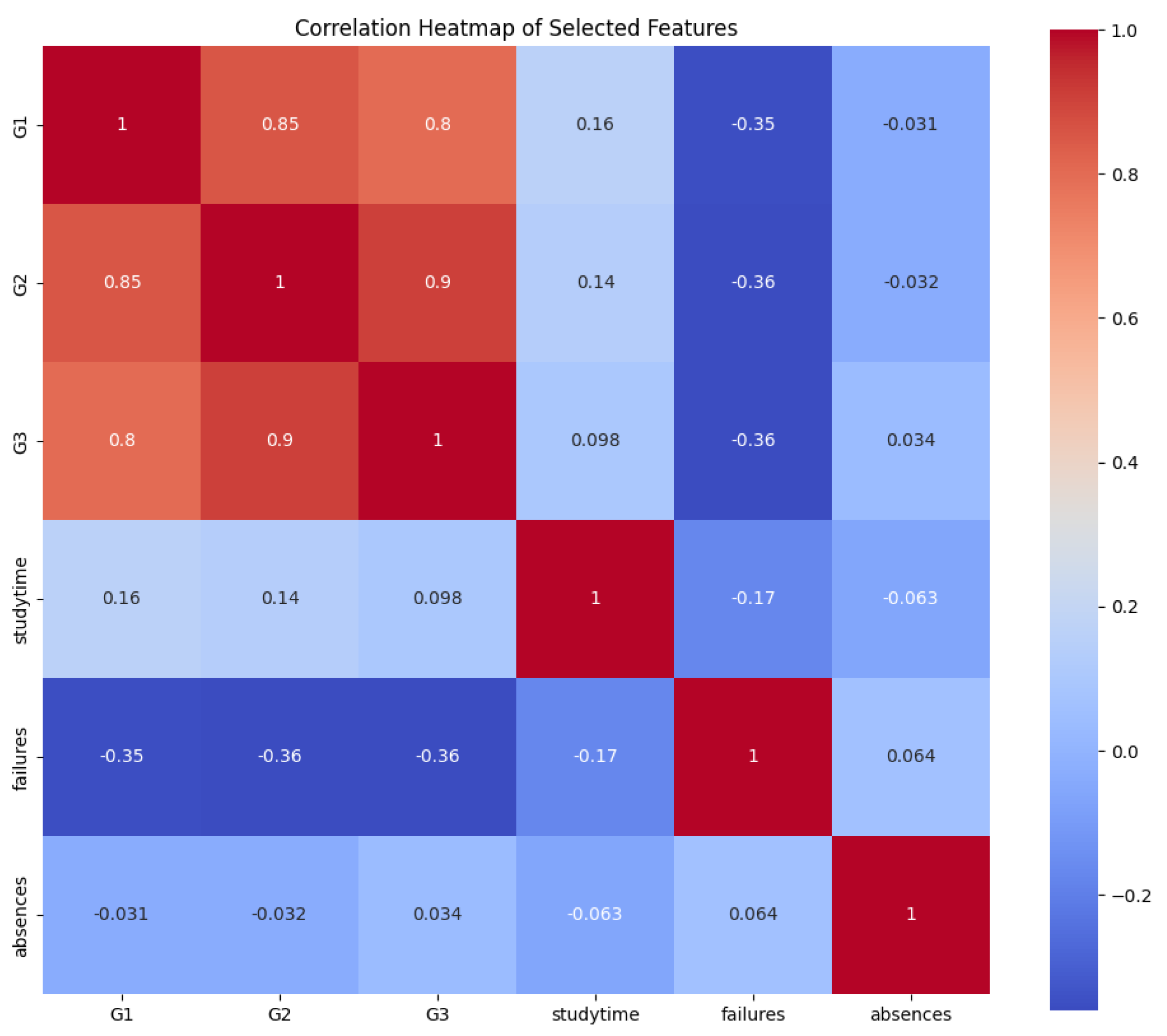

Figure 6.

Correlation Heatmap.

Figure 6.

Correlation Heatmap.

The heatmap of G1, G2, actual G3, and predicted G3 mutual correlations shows the prevalence of positive relation between the early period grades (G1, G2) and final grade outcomes. Both G1 and G2 correspond with G3 above 0.85, and the predicted values are also in line with this relationship, which adds to the model’s credibility and the fittingness of feature select.

Moreover, security concerns were also considered along with model development. These include the encryption of student data during preprocessing, the management of access controls during training, and the secure storage of model weight and artifact. The above security measures will ensure the confidentiality and integrity of students’ sensitive recordings while at the same time exhibit the proper implementation of educational analytics that respect user privacy.

On a broader front, the demonstrated results serve to underscore the effectiveness of the student monitoring model as a real-world application. The portrayal of performance metrics and visual evidences adds credence to the assertion that the neural network model created on PyTorch is valid, accurate, and therefore is a solid base for making extensive data-driven tools for student support.

6. Discussion

Based on the findings of this study, it can be said that deep learning applications, especially feedforward neural networks, can be used for good in predicting secondary school students’ academic performance. The compute PyTorch model that was used in this study reached a root mean squared error (RMSE) of about 2.49 on the grading scale from 0 to 20, using a dataset consisting of demographic, behavioral, and academic factors. The accuracy of this model shows the possibility of the model to find out non-linear dependencies in the educational features and to make meaningful predictions [

25].

The scatter plot which compares the actual grades with the model predicted grades is also a good illustration of the model performance. Although most of the data points cluster around the diagonal type of line indicating perfect predictions, the width of residuals in the data suggest that there might be some hidden factors like students’ motivation, emotional stress, or learning difficulties which are not included in the dataset [

26]. If these features are added to the study, the result can be predictive performance improvement in the future. On the other hand, the deep learning models with more flexibility and the ability to scale as compared to traditional machine learning models like decision trees, support vector machines, and random forests. Previous studies have shown that ensemble methods are also useful for educational data, though not on par with deep learning, especially when using high-dimensional data and finding complex relationships between variables [

27,

28].

In spite of that, the interpretability is a bottleneck. Since the educational sector usually requires transparency for the stakeholders, including students, parents, and faculty, the intervention of explainable AI (XAI) techniques is a must. SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) have been proposed as the tools to add interpretability to the models without compromising performance [

29,

30].

The focus of this research was security and data privacy. Since the educational datasets contain personally identifiable information (PII), it is extremely important to secure data pipelines and create isolated training environments for data. Stronger solutions like encryption, anonymization, and access controls should be put in place, particularly when deploying the models in the cloud [

13,

31]. Legal instruments like FERPA (in the U.S.) or GDPR (in the EU) are also obligatory and are necessary for ensuring proper AI implementation in educational settings [

32].

Nevertheless, although the dataset which was used in this research is valuable and widely recognized [

17], it is modest in size (~395 samples), limiting the ability to generalize. More extensive, diverse, and longitudinal datasets could lead to the creation of more resilient models. Similarly, the introduction of multimodal data like the natural language processing of student essays or classroom audio might be a good outlet for predictive modeling, and personalized education [

33].

Taking everything into account, this research identifies the immense value deep learning can have in the area of analytics in education. The discoveries not only validate the applicability of this process in predicting the performance but also highlight the need of embedding security, explainability, and ethical issues in AI driven education system along with it.

7. Future Work

The neural network, proficient in approximating students’ academic performance as per the results of the experiments, is perceived to be in the position to approve of areas such as (i) Extend the potential of the system in further studies and (ii) areas of improvement, as soon as they are demonstrated.

7.1. Dataset Expansion and Diversity

The present model was built on a dataset that had a limited number of observations (n = 395), which may affect the generalization to different groups of students. The model would draw on the improvement of building the poly-dimensional arrays to the creation of the anti-fatigued decision trees that are the results of incorporating temporal data (e.g., year-over-year performance) that longitudinally support and trend modeling [

26].

7.2. Feature Enrichment

The dataset primarily consisted of demographic, behavioral, and academic features. Yet, the psychosocial factors that motivate stress, sleep, and mental health of an individual have a direct influence on a student’s performance. Innovative models can be built from survey data on integration of learning management system (LMS) interactions and biometrics to capture the entire student behavior context [

27].

7.3. Model Architecture Optimization

The present architecture applies a feedforward neural network that consists of hidden layers. Bypassing attention methods adding depth, residual connections, or possibilities of exploring residual or attention mechanisms might; thus, increase accuracy. Furthermore, adaptive system designs like Bayesian Optimization or AutoML frameworks can be used for quickly handling the most suitable model architecture without manual control [

34].

7.4. Explainable AI (XAI) Integration

Transparency is a very important part to focus on, especially in the educational world where students’ decisions are made based on the outcomes. This can be done by including tools like SHAP or LIME that give the feature level explanations and allow the educators to interpret the underperforming student as well as support them individually [

29,

30]

7.5. Security and Privacy Enhancements

As concerns about data privacy get greater, especially in educational settings, the model can achieve an additional layer of security by introducing federated learning, differential privacy, or homomorphic encryption. Such methods make it possible to learn from decentralized sources or encrypted data while still keeping student information private [

13,

32].

7.6. Real-Time and Adaptive Systems

The utilization of the model in the real-time educational platform will help in the dynamic student tracking. The models can adapt to new data arriving by the re-training that is done periodically. In addition, the loop generation, which is when the model predictions student behavior in learning inaccuracies and then the model predictions out of this that would favor interventions, can be one of a possible way for intelligent tutoring systems to follow the steps.

7.7. Comparative Analysis with Other Algorithms

Instead of merely programming neural nets to replicating device operation, it is mandatory to compare performance with conventional learning strategies like making trees (e.g., XGBoost, LightGBM) or graph neural networks (if relational data is present) that can show trade-offs in results with a newly formed algorithm. Ensemble models that combine traditional ML with deep learning may yield further performance improvements [

35]. Briefly, the present research is a baseline for further development of artificial intelligence in the educational world. When data breadth is increased, model complexity is enhanced, security and interpretability are imbibed, and the way to adaptive learning environments is placed, the predictive academic performance models become stronger, more active agents of ethical tools that support student success.

8. Conclusion

The current study was devoted to the functioning of a deep learning model, especially a feedforward neural network based on PyTorch, to forecast the performance of a student owing to the demographic, behavioral, and academic features from the UCI Student Performance dataset. The model has shown the capability to reach an RMSE of about 2.5 on the 0–20 grading scale which is indicative of an encouraging level of accuracy for the practical applications in academic performance forecasting. The model’s results showed that it could indeed find the nonlinear, complex relationships between many factors that affect the student’s outcomes, and therefore it was possible to use it as a valuable predict. The most important finding of this research is the integration of security measures in the model development pipeline, which includes secure data handling practices, encryption techniques, and secure deployment recommendations. Data privacy in the field of educational technology is a growing concern, and the implementation of such measures is a practical approach that ensures that predictive models are across the board ethical and comply with the data protection laws, such as FERPA and GDPR (Han et al., 2019; Zliobaite, 2017). Moreover, the study presented several paths for future work development. These are: boosting the data base, joining psychosocial and behavioral data, enhancing the models architecture, and providing the construct of explainable AI. The added improvements will not only increase predictive accuracy but also provide actionable insights for teachers and managers. To summarize, this work is the expansion of the field of educational data mining, and learning analytics by the validation of the deep learning model in real-world suggesting that the use of deep learning models in actual academic settings is substantiated. The concurrent achievement of the predictive performance and the privacy-aware practices is a great step toward fostering quality educational AI systems that are not only scalable, ethical, and impactful but also can be used in a way that supports the success of students and the effectiveness of the institution.

Acknowledgment

The preferred spelling of the word “acknowledgment” in America is without an “e” after the “g”. Avoid the stilted expression “one of us (R. B. G.) thanks ...”. Instead, try “R. B. G. thanks...”. Put sponsor acknowledgments in the unnumbered footnote on the first page.

References

- Khan, I. , Ahmad, A.R., Jabeur, N. et al. An artificial intelligence approach to monitor student performance and devise preventive measures. Smart Learn. Environ. 8, 17 (2021). [CrossRef]

- L. L. Baer and D. M. Norris, “A Call to Action for Student Success Analytics,” Planning for Higher Education, vol. 44, (4), pp. 1-10, 2016. Available: http://tricountycc.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/call-action-student-success-analytics/docview/1838984923/se-2.

- N. Cele, “Big data-driven early alert systems as means of enhancing university student retention and success”, SAJHE, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 56-72, 21. May 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Park and M. Y. Doo, “Role of AI in Blended Learning: A Systematic Literature Review”, IRRODL, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 164–196, Mar. 2024.

- LeCun, Y. , Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Chui, K. T. , Fung, D. C. L., Lytras, M. D., & Lam, T. M. (2020). Predicting at-risk university students in a virtual learning environment via a machine learning algorithm. Computers in Human Behavior, 107, Article 105584. [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.S. , Inventado, P.S. (2014). Educational Data Mining and Learning Analytics. In: Larusson, J., White, B. (eds) Learning Analytics. Springer, New York, NY. [CrossRef]

- R. Asif, A. R. Asif, A. Merceron, S. A. Ali, and N. G. Haider, “Analyzing undergraduate students’ performance using educational data mining,” Computers & Education, vol. 113, pp. 177–194. May 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Musso, E. M. F. Musso, E. Kyndt, E. C. Cascallar, and F. Dochy, “Predicting general academic performance and identifying the differential contribution of participating variables using artificial neural networks,” Frontline Learning Research, vol. 1, no. 1, Aug. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A. , Gross, S., Massa, F., Lerer, A., Bradbury, J., Chanan, G.,... & Chintala, S. (2019). PyTorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 32.

- Geron, A. (2019) Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras, and TensorFlow: Concepts, Tools, and Techniques to Build Intelligent Systems. 2nd Edition, O’Reilly Media, Inc., Sebastopol.

- Kuhn, M. , & Johnson, K. (2013). Applied Predictive Modeling. New York: Springer. [CrossRef]

- J. Han, J. J. Han, J. Pei, and H. Tong, *Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques*, 4th ed. Cambridge, MA, USA: Morgan Kaufmann, 2022.

- V. Tinto, “Research and Practice of student retention: What next?,” Journal of College Student Retention Research Theory & Practice, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–19. May 2006. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Bean and S. B. Eaton, “A psychological model of college student retention,” in Vanderbilt University Press eBooks, 2020, pp. 48–61. [CrossRef]

- W. Xing and D. Du, “Dropout prediction in MOOCs: Using deep learning for personalized intervention,” Journal of Educational Computing Research, vol. 57, no. 3, pp. 547–570, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Cortez and A. Silva, “Using data mining to predict secondary school student performance,” in Proc. 5th Future Business Technology Conf., EUROSIS, 2008, pp. 5–12.

- M. Hussain, W. M. Hussain, W. Zhu, W. Zhang, and S. M. R. Abidi, “Student Engagement Predictions in an e-Learning System and their impact on student course assessment scores,” Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, vol. 2018, pp. 1–21, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Amrieh, T. E. A. Amrieh, T. Hamtini, and I. Aljarah, “Mining Educational Data to Predict Student’s academic Performance using Ensemble Methods,” International Journal of Database Theory and Application, vol. 9, no. 8, pp. 119–136, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. James, D. G. James, D. Witten, T. Hastie, and R. Tibshirani, An introduction to statistical learning. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, Y. Bengio, and A. Courville, Deep learning. MIT Press, 2016.

- Ishaq and M., N. Brohi, “Cloud computing in education sector with security and privacy issue: A proposed framework,” Int. J. Adv. Eng. Technol., vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 889–898, Dec. 2015.

- V. Nair and G. E. Hinton, “Rectified linear units improve restricted Boltzmann machines,” in Proc. 27th Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. (ICML), 2010, pp. 807–814.

- D. P. Kingma and J. L. Ba, “Adam: A method for stochastic optimization,” arXiv (Cornell University), Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Z. Alom et al., “A State-of-the-Art Survey on Deep learning theory and architectures,” Electronics, vol. 8, no. 3, p. 292, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. T. Tempelaar, B. Rienties, and B. Giesbers, “In search for the most informative data for feedback generation: Learning analytics in a data-rich context,” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 47, pp. 157–167, Jun. 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. Sarker, “Deep Learning: a comprehensive overview on techniques, taxonomy, applications and research directions,” SN Computer Science, vol. 2, no. 6, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Ristoski and H. Paulheim, “Semantic Web in data mining and knowledge discovery: A comprehensive survey,” Journal of Web Semantics, vol. 36, pp. 1–22, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Lundberg and S.-I. Lee, “A unified approach to interpreting model predictions,” in Proc. 31st Int. Conf. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. (NeurIPS), Long Beach, CA, USA, Dec. 4–9, 2017, pp. 4766–4777. Let me know if you’d like this added to your reference list or need others converted.

- M. Ribeiro, S. Singh, and C. Guestrin, “Why should I trust you?: Explaining the predictions of any classifier,” in Proc. 2016 Conf. North Amer. Chapter Assoc. Comput. Linguistics: Demonstrations, San Diego, CA, USA, Jun. 2016, pp. 97–101. [CrossRef]

- L. Sweeney, “K-ANONYMITY: a MODEL FOR PROTECTING PRIVACY,” International Journal of Uncertainty Fuzziness and Knowledge-Based Systems, vol. 10, no. 05, pp. 557–570, Oct. 2002. [CrossRef]

- Žliobaitė, “Measuring discrimination in algorithmic decision making,” Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 1060–1089, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Mangaroska, K.. Sharma, D.. Gasevic, and M.. Giannakos, “Multimodal Learning Analytics to Inform Learning Design: Lessons Learned from Computing Education”, Learning Analytics, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 79-97, Dec. 2020.

- T. Elsken, J. H. Metzen, and F. Hutter, “Neural architecture search: A survey,” J. Mach. Learn. Res., vol. 20, pp. 1–21, Mar. 2019.

- M. Yağcı, “Educational data mining: prediction of students’ academic performance using machine learning algorithms,” Smart Learning Environments, vol. 9, no. 1, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).