Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

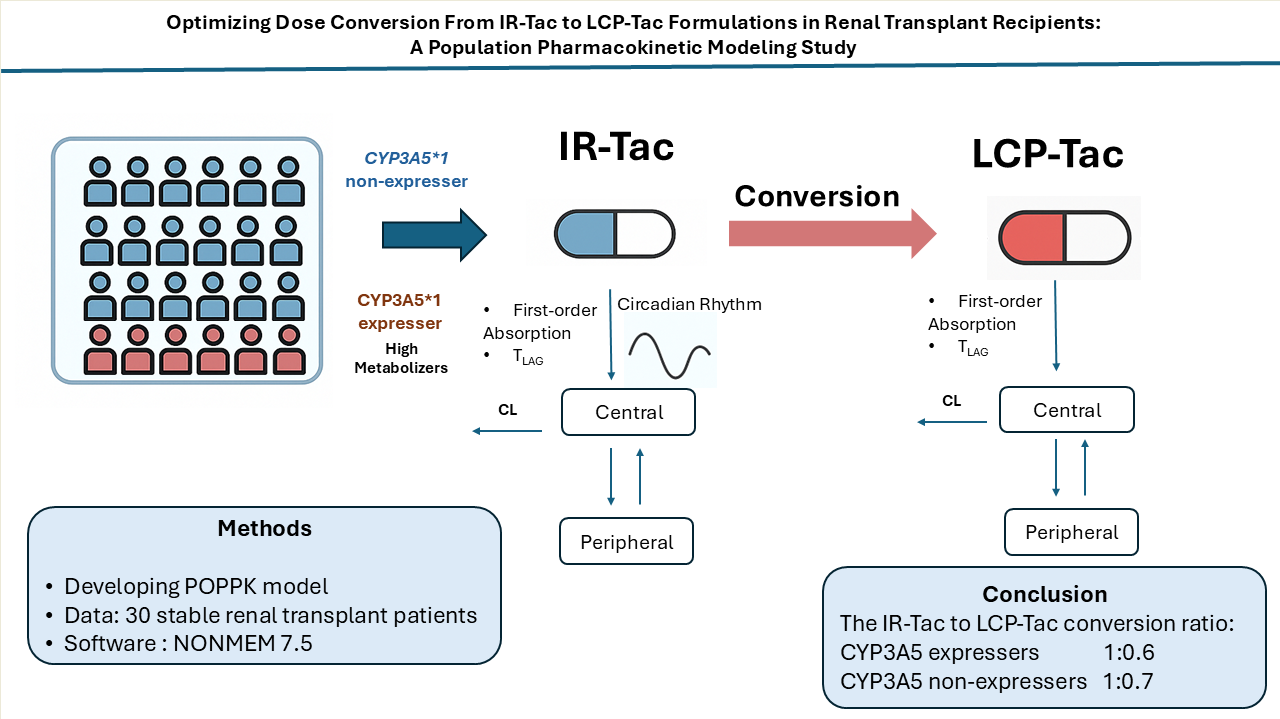

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Blood Sampling and Data Recording

2.3. Tacrolimus Measurement

2.4. Genotyping

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Population Pharmacokinetic Analysis

2.6.1. Base Model Development

2.6.2. Covariate Analysis

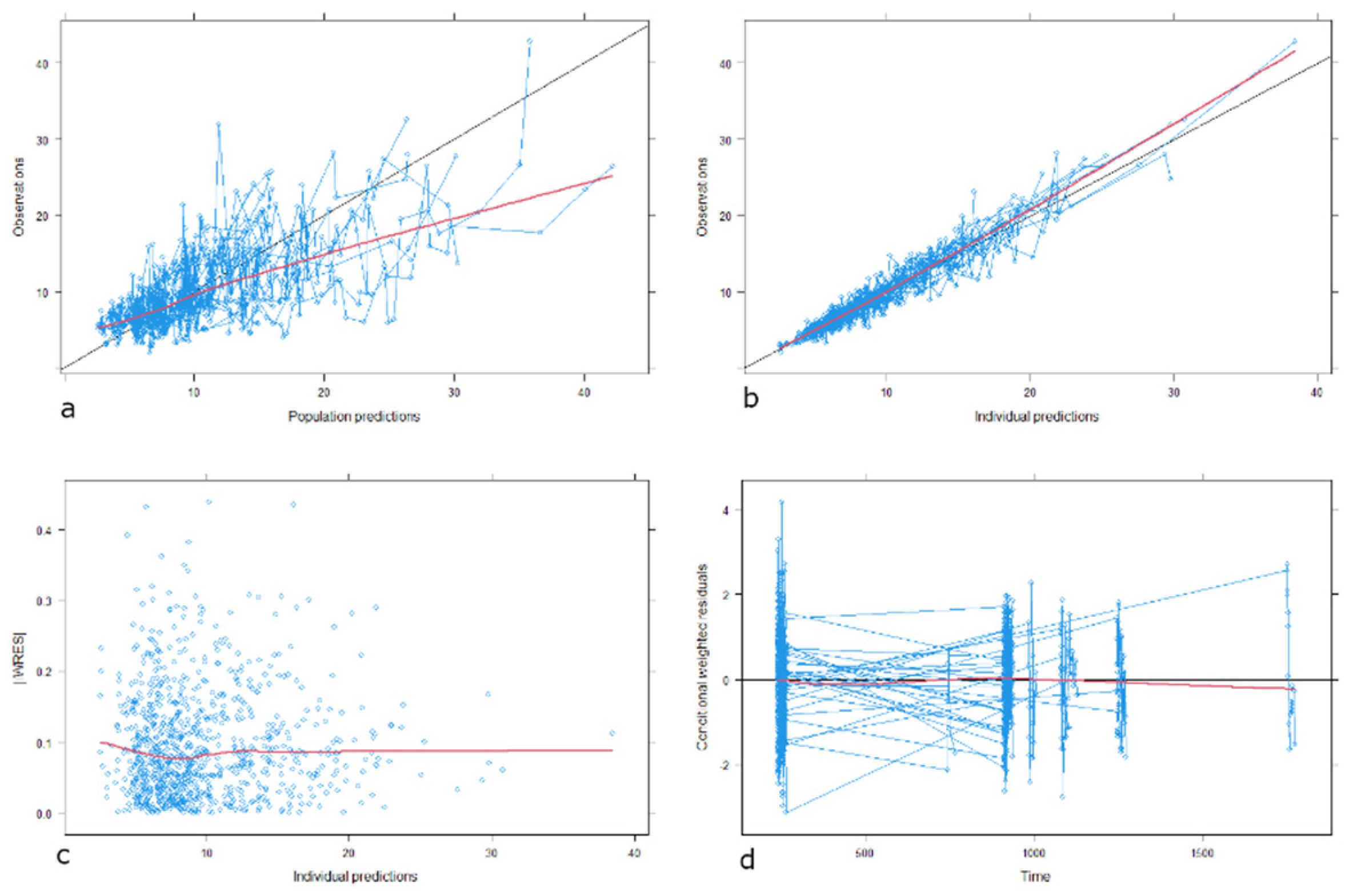

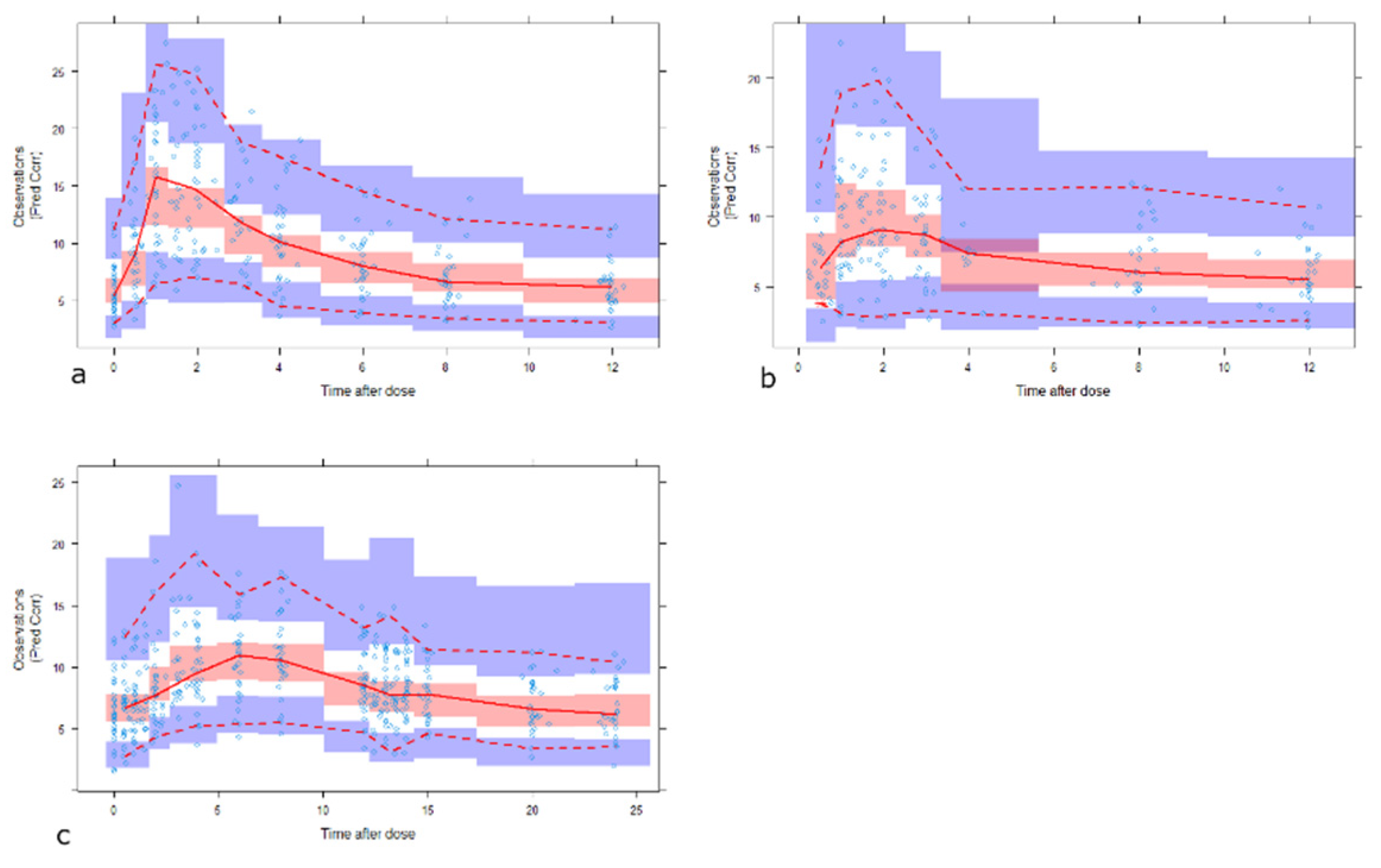

2.7. Model Evaluation and Internal Validation

2.8. Simulations

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics and Datasets

3.2. Population PK Analysis

3.2.1. Base Model

3.2.2. Covariate Model

3.2.3. Model Evaluation

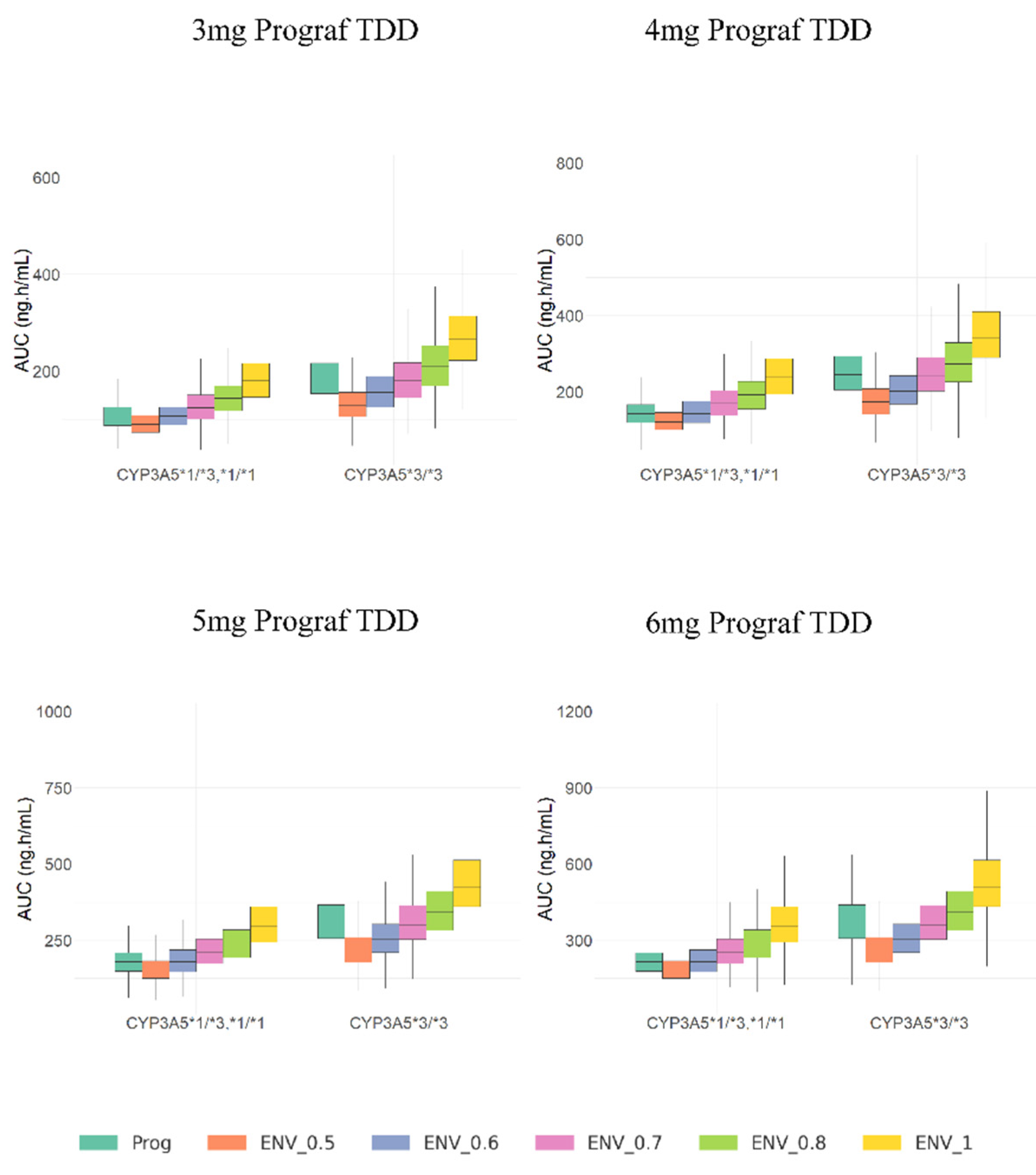

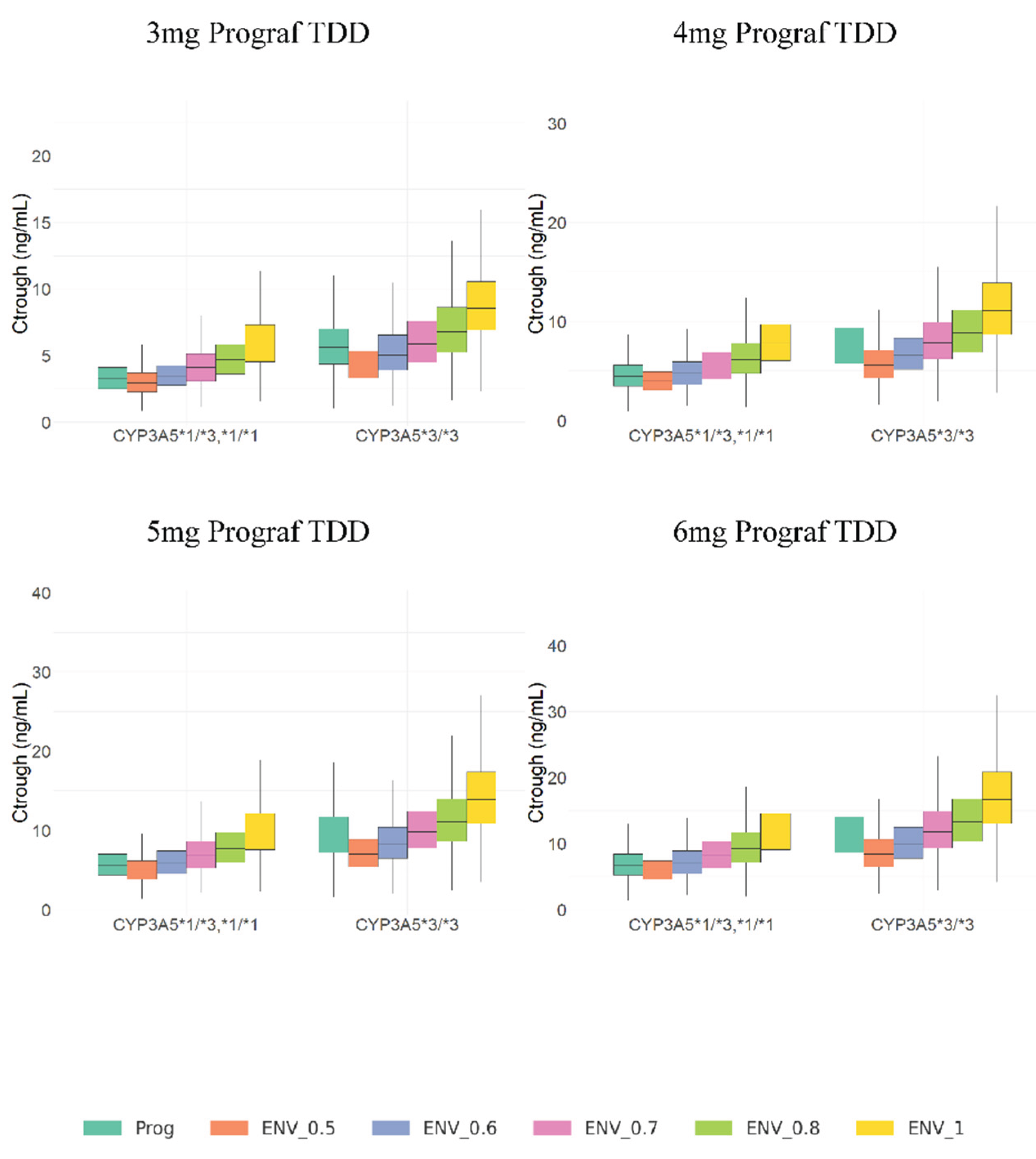

3.3. Model Simulations

4. Discussion

- Study Highlights

-

What is already known?

- -

- LCP-TAC has higher oral bioavailability and lower total daily dose requirement compared to IR-TAC.

- -

- The current conversion ratio of IR-Tac to LCP-Tac is 0.7-0.8 for all patient populations

-

What this study adds?

- -

- Identifies factors influencing IR-TAC to LCP-TAC conversion ratios across different patient population.

- -

- Emphasizes genetic polymorphism’s role in optimizing tacrolimus dosing post-conversion in renal transplant patients.

-

Clinical significance?

- -

- Supports genotype-guided IR-TAC to LCP-TAC conversion ratios

- -

- Enables personalized dosing strategies, reducing rejection risk and adverse effects post-transplant.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kuypers, DRJ. Intrapatient Variability of Tacrolimus Exposure in Solid Organ Transplantation: A Novel Marker for Clinical Outcome. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020;107(2):347-358. [CrossRef]

- Staatz CE, Tett SE. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of tacrolimus in solid organ transplantation. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43(10):623-653. [CrossRef]

- Venkataramanan, R.; Swaminathan, A.; Prasad, T.; Jain, A.; Zuckerman, S.; Warty, V.; McMichael, J.; Lever, J.; Burckart, G.; Starzl, T. Clinical pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1995;29(6):404-430. [CrossRef]

- Katari, S.R.; Magnone, M.; Shapiro, R.; Jordan, M.; Scantlebury, V.; Vivas, C.; Gritsch, A.; McCauley, J.; Starzl, T.; Demetris, A.J.; et al. Clinical features of acute reversible tacrolimus (FK 506) nephrotoxicity in kidney transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 1997;11(3):237. Accessed August 18, 2022. /pmc/articles/PMC2967284/.

- Tremblay, S.; Nigro, V.; Weinberg, J.; Woodle, ES.; Alloway, RR. A Steady-State Head-to-Head Pharmacokinetic Comparison of All FK-506 (Tacrolimus) Formulations (ASTCOFF): An Open-Label, Prospective, Randomized, Two-Arm, Three-Period Crossover Study. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(2):432-442. [CrossRef]

- Wallemacq, PE.; Verbeeck, RK. Comparative clinical pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus in paediatric and adult patients. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2001;40(4):283-295. [CrossRef]

- Wallemacq, P.E.; Furlan, V.; Möller, A.; Schäfer, A.; Stadler, P.; Firdaous, I.; Taburet, A.-M.; Reding, R.; Clement De Clety, S.; De Ville De Goyet, J.; et al. Pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus (FK506) in paediatric liver transplant recipients. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1998;23(3):367-370. [CrossRef]

- Nigro, V.; Glicklich, A.; Weinberg, J. Improved Bioavailability of MELTDOSE Once-Daily Formulation of Tacrolimus (LCP-Tacro) with Controlled Agglomeration Allows for Consistent Absorption over 24 Hrs: A Scintigraphic and Pharmacokinetic Evaluation. American Journal of Transplants. 2013.

- Rostaing, L.; Bunnapradist, S.; Grinyó, J.M.; Ciechanowski, K.; Denny, J.E.; Silva, H.T., Jr.; Budde, K.; Envarsus Study Group. Novel Once-Daily Extended-Release Tacrolimus Versus Twice-Daily Tacrolimus in De Novo Kidney Transplant Recipients: Two-Year Results of Phase 3, Double-Blind, Randomized Trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(4):648-659. [CrossRef]

- Trofe-Clark, J.; Brennan, D.C.; West-Thielke, P.; Milone, M.C.; Lim, M.A.; Neubauer, R.; Nigro, V.; Bloom, R.D. Results of ASERTAA, a Randomized Prospective Crossover Pharmacogenetic Study of Immediate-Release Versus Extended-Release Tacrolimus in African American Kidney Transplant Recipients. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2018;71:315-326. [CrossRef]

- Langone, A.; Steinberg, S.M.; Gedaly, R.; Chan, L.K.; Shah, T.; Sethi, K.D.; Nigro, V.; Morgan, J.C.; STRATO Investigators. Switching STudy of Kidney TRansplant PAtients with Tremor to LCP-TacrO (STRATO): An open-label, multicenter, prospective phase 3b study. Clin Transplant. 2015;29(9):796-805. [CrossRef]

- Gaber, AO.; Alloway, RR.; Bodziak, K.; Kaplan, B.; Bunnapradist, S. Conversion from twice-daily tacrolimus capsules to once-daily extended-release tacrolimus (LCPT): A phase 2 trial of stable renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2013;96(2):191-197. [CrossRef]

- Fontova, P.; Colom, H.; Rigo-Bonnin, R.; Bestard, O.; Vidal-Alabró, A.; van Merendonk, L.N.; Cerezo, G.; Polo, C.; Montero, N.; Melilli, E.; et al. Sustained Inhibition of Calcineurin Activity With a Melt-Dose Once-daily Tacrolimus Formulation in Renal Transplant Recipients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021;110(1):238-247. [CrossRef]

- Bunnapradist, S.; Ciechanowski, K.; West-Thielke, P.; Mulgaonkar, S.; Rostaing, L.; Vasudev, B.; Budde, K. Conversion From Twice-Daily Tacrolimus to Once-Daily Extended Release Tacrolimus (LCPT): The Phase III Randomized MELT Trial. American Journal of Transplantation. 2013;13(3):760. [CrossRef]

- Budde, K.; Bunnapradist, S.; Grinyó, J.M.; Ciechanowski, K.; Denny, J.E.; Silva, H.T.; Rostaing, L.; Envarsus Study Group. Novel Once-Daily Extended-Release Tacrolimus (LCPT) Versus Twice-Daily Tacrolimus in De Novo Kidney Transplants: One-Year Results of Phase III, Double-Blind, Randomized Trial. American Journal of Transplantation. 2014;14(12):2796-2806. [CrossRef]

- Staatz, CE.; Tett, SE. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Once-Daily Tacrolimus in Solid-Organ Transplant Patients. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2015;54(10):993-1025. [CrossRef]

- Lampen, A.; Christians, U.; Guengerich, F.P.; Watkins, P.B.; Kolars, J.C.; Bader, A.; Gonschior, A.K.; Dralle, H.; Hackbarth, I.; Sewing, K.F. Metabolism of the immunosuppressant tacrolimus in the small intestine: cytochrome P450, drug interactions, and interindividual variability. 1995;23(12).

- Iwasaki K. Metabolism of tacrolimus (FK506) and recent topics in clinical pharmacokinetics. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2007;22(5):328-335. [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, K.; Shiraga, T.; Matsuda, H.; Teramura, Y.; Kawamura, A.; Hata, T.; Ninomiya, S.; Esumi, Y. Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism and Excretion of Tacrolimus (FK506) in the Rat. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1998;13(3):259-265. [CrossRef]

- Lloberas, N.; Vidal-Alabró, A.; Colom, H. Customizing Tacrolimus Dosing in Kidney Transplantation: Focus on Pharmacogenetics. Ther Drug Monit. 2025;47(1):141-151. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Hebert, M.F.; Isoherranen, N.; Davis, C.L.; Marsh, C.; Shen, D.D.; Thummel, K.E. Effect of CYP3A5 polymorphism on tacrolimus metabolic clearance in vitro. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34(5):836-847. [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, H.; De Loor, H.; Verbeke, K.; Vanrenterghem, Y.; Kuypers, DR. In vivo CYP3A4 activity, CYP3A5 genotype, and hematocrit predict tacrolimus dose requirements and clearance in renal transplant patients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92(3):366-375. [CrossRef]

- Birdwell, K.A.; Decker, B.; Barbarino, J.M.; Peterson, J.F.; Stein, C.M.; Sadee, W.; Wang, D.; Vinks, A.A.; He, Y.; Swen, J.J.; et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guidelines for CYP3A5 Genotype and Tacrolimus Dosing. [CrossRef]

- Andreu, F.; Colom, H.; Elens, L.; van Gelder, T.; van Schaik, R.H.N.; Hesselink, D.A.; Bestard, O.; Torras, J.; Cruzado, J.M.; Grinyó, J.M.; et al. A New CYP3A5*3 and CYP3A4*22 Cluster Influencing Tacrolimus Target Concentrations: A Population Approach. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2017;56(8):963-975. [CrossRef]

- Woillard, JB.; De Winter, BCM.; Kamar, N.; Marquet, P.; Rostaing, L.; Rousseau, A. Population pharmacokinetic model and Bayesian estimator for two tacrolimus formulations--twice daily Prograf and once daily Advagraf. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71(3):391-402. [CrossRef]

- Henin, E.; Govoni, M.; Cella, M.; Laveille, C.; Piotti, G. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Strategies for Envarsus in De Novo Kidney Transplant Patients Using Population Modelling and Simulations. Adv Ther. 2021;38(10):5317-5332. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed Ali, Z.; Meertens, M.; Fernández, B.; Fontova, P.; Vidal-Alabró, A.; Rigo-Bonnin, R.; Melilli, E.; Cruzado, J.M.; Grinyó, J.M.; Colom, H.; et al. CYP3A5*3 and CYP3A4*22 Cluster Polymorphism Effects on LCP-Tac Tacrolimus Exposure: Population Pharmacokinetic Approach. Pharmaceutics 2023, Vol 15, Page 2699. 2023;15(12):2699. [CrossRef]

- Brunet, M.; van Gelder, T.; Åsberg, A.; Haufroid, V.; Hesselink, D.A.; Langman, L.; Lemaitre, F.; Marquet, P.; Seger, C.; Shipkova, M.; et al. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Tacrolimus-Personalized Therapy: Second Consensus Report. Ther Drug Monit. 2019;41(3):261-307. [CrossRef]

- Crespo, E.; Vidal-Alabró, A.; Jouve, T.; Fontova, P.; Stein, M.; Mocka, S.; Meneghini, M.; Sefrin, A.; Hruba, P.; Gomà, M.; et al. Tacrolimus CYP3A Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms and Preformed T- and B-Cell Alloimmune Memory Improve Current Pretransplant Rejection-Risk Stratification in Kidney Transplantation. Front Immunol. 2022;13:869554. [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Alabró, A.; Fontova, P.; Rigo-Bonnin, R.; Mohammed Ali, Z.; Melilli, E.; Montero, N.; Manonelles, A.; Coloma, A.; Grinyó, J.M.; Cruzado, J.M.; et al. Nephrology Department, Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge- IDIBELL, Barcelona, Spain. 2025, (manuscript in preparation; to be submitted).

- Rigo-Bonnin, R.; Arbiol-Roca, A.; de Aledo-Castillo, JMG.; Alía, P. Simultaneous Measurement of Cyclosporine A, Everolimus, Sirolimus and Tacrolimus Concentrations in Human Blood by UPLC–MS/MS. Chromatographia. 2015;78(23-24):1459-1474. [CrossRef]

- Davit, B.M.; Chen, M.-L.; Conner, D.P.; Haidar, S.H.; Kim, S.; Lee, C.H.; Lionberger, R.A.; Makhlouf, F.T.; Nwakama, P.E.; Patel, D.T.; et al. Implementation of a reference-scaled average bioequivalence approach for highly variable generic drug products by the US Food and Drug Administration. AAPS J. 2012;14(4):915-924. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Alarcón, B.; Mohammed Ali, Z.; Fontova, P.; Vidal-Alabró, A.; Rigo-Bonnin, R.; Melilli, E.; Montero, N.; Manonelles, A.; Coloma, A.; Grinyó, J.M.; et .al, Nephrology Department, Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge- IDIBELL, Barcelona, Spain. 2025, (manuscript in preparation; to be submitted).

- Fontova, P.; Colom, H.; Rigo-Bonnin, R.; van Merendonk, L.N.; Vidal-Alabró, A.; Montero, N.; Melilli, E.; Meneghini, M.; Manonelles, A.; Cruzado, J.M.; et al. Influence of the Circadian Timing System on Tacrolimus Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics After Kidney Transplantation. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12. [CrossRef]

- Yamaoka, K.; Nakagawa, T.; Uno, T. Application of Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) in the evaluation of linear pharmacokinetic equations. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1978;6(2):165-175. [CrossRef]

- Savic, RM,; Karlsson, MO. Importance of Shrinkage in Empirical Bayes Estimates for Diagnostics: Problems and Solutions. AAPS J. 2009;11(3):558. [CrossRef]

- Bergstrand, M.; Hooker, AC.; Wallin, JE.; Karlsson, MO. Prediction-corrected visual predictive checks for diagnosing nonlinear mixed-effects models. AAPS J. 2011;13(2):143-151. [CrossRef]

- Andreu, F.; Colom, H.; Grinyó, JM.; Torras, J.; Cruzado, JM.; Lloberas, N. Development of a population PK model of tacrolimus for adaptive dosage control in stable kidney transplant patients. Ther Drug Monit. 2015;37(2):246-255. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Alarcón, B.; Nolberger, O.; Vidal-Alabró, A.; Rigo-Bonnin, R.; Grinyó, J.M.; Melilli, E.; Montero, N.; Manonelles, A.; Coloma, A.; Favà, A.; et al. Guiding the starting dose of the once-daily formulation of tacrolimus in “de novo” adult renal transplant patients: a population approach. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1456565. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, L.M.; Hesselink, D.A.; van Schaik, R.H.N.; van Gelder, T.; de Fijter, J.W.; Lloberas, N.; Elens, L.; Moes, D.J.A.R.; de Winter, B.C.M. A population pharmacokinetic model to predict the individual starting dose of tacrolimus in adult renal transplant recipients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85(3):601-615. [CrossRef]

- Åsberg, A.; Midtvedt, K.; van Guilder, M.; Størset, E.; Bremer, S.; Bergan, S.; Jelliffe, R.; Hartmann, A.; Neely, M.N. Inclusion of CYP3A5 genotyping in a nonparametric population model improves dosing of tacrolimus early after transplantation. Transplant International. 2013;26(12):1198. [CrossRef]

- Sanghavi, K.; Brundage, R.C.; Miller, M.B.; Schladt, D.P.; Israni, A.K.; Guan, W.; Oetting, W.S.; Mannon, R.B.; Remmel, R.P.; Matas, A.J.; et al. Genotype-guided tacrolimus dosing in African-American kidney transplant recipients. The Pharmacogenomics Journal 2017 17:1. 2015;17(1):61-68. [CrossRef]

- Baccarani, U.; Velkoski, J.; Pravisani, R.; Adani, G.L.; Lorenzin, D.; Cherchi, V.; Falzone, B.; Baraldo, M.; Risaliti, A. MeltDose Technology vs Once-Daily Prolonged Release Tacrolimus in De Novo Liver Transplant Recipients. Transplant Proc. 2019;51(9):2971-2973. [CrossRef]

- Baraldo, M. Meltdose Tacrolimus Pharmacokinetics. Transplant Proc. 2016;48(2):420-423. [CrossRef]

- Tsunashima, D.; Kawamura, A.; Murakami, M.; Sawamoto, T.; Undre, N.; Brown, M.; Groenewoud, A.; Keirns, J.J.; Holman, J.; Connor, A.; et al. Assessment of tacrolimus absorption from the human intestinal tract: open-label, randomized, 4-way crossover study. Clin Ther. 2014;36(5):748-759. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | IR-Tac | LCP-Tac |

| Patients (n) | 30 | 30 |

| Samplings (n) | 481 | 451 |

| Gender Male/Female, n/n) | 22/8 | 22/8 |

| Weight (Kg) | 72 (64-80) | 73 (64-80) |

| Age (Years) | 58 (48-68) | 58 (48-68) |

| BMI (Kg.m-2) | 26 (21.5-29.3) | 27 (21.5-29.3) |

| HTC (%) | 40.9 (37.6-44.8) | 40.1 (37.1-43) |

| GFR (mL.min-1) | 49.6 (34-57) | 49.3 (42-58) |

| Cr (μmol.L-1) | 141.9 (108-166) | 147.6 (111-155) |

| CYP3A5 Genotype | ||

| *1/*3 n (%) | 9 (30%) | 9 (30%) |

| *1/*1 n (%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) |

| *3/*3 n (%) | 20 (67%) | 20 (67%) |

|

Formulation / Genotype Group |

Dose (mg.day-1) | N |

Ctrough (ng.mL-1) |

Ctrough/D |

AUC24 (ng.h.mL-1) |

AUC24/D | Relative Bioavailability |

p-Value |

| IR-Tac | ||||||||

| CYP3A5 *1/*1, *1/*3 | 5 (3-12) | 20 | 4.9 (4.6-5.2) | 1.6(1.4-2) | 195 (184-224) | 32 (27-43) | ||

| LCP-Tac | 0.60 | <0.001 * | ||||||

| CYP3A5 *1/*1, *1/*3 | 3.75 (2-8.5) | 10 | 5.6 (4.5-6.7) | 1.28 (0.9-1.8) | 232(173-286) | 53 (38-71) | ||

| IR-Tac | ||||||||

| CYP3A5 *3/*3 | 3 (1.5-8) | 20 | 5.7 (4.7-7.2) | 3.6(2.9-4.6) | 212 (169-250) | 68 (56-81) | <0.001 # | |

| LCP-Tac | 0.72 | |||||||

| CYP3A5 *3/*3 | 2 (1-4.75) | 10 | 5.7 (4.7-6.7) | 2.7(2.2-3.3) | 199 (163-265) | 94 (76-122) |

| Final model parameter estimates (RSE%) | Bootstrap results * | |||||

| Parameter | Description | Value | Bootstrap median | 90 % CI | ||

| Disposition PK parameters | ||||||

| CL/F (L.h-1) | Apparent Elimination Clearance | 11.9 (8.5%) | 11.85 | 10.34-13.53 | ||

| Vc/F (L) | Apparent Distribution Volume of central compartment | 78 (14.7%) | 81 | 63-100.22 | ||

| CLd/F (L.h-1) | Apparent Distributional Clearance | 25.8 (8.5%) | 25.75 | 22.08-29.39 | ||

| Vp/F (L) | Apparent Distribution Volume of peripheral compartment | 500 FIX | - | - | ||

| Absorption parameters | ||||||

| Ka IR-Tac | Absorption rate constant (IR-Tac) | 2.04 (40%) | 2.17 | 1.23-3.72 | ||

| Ka LCP_Tac | Absorption rate constant (LCP-Tac) | 0.111 (16.9%) | 0.115 | 0.08-0.15 | ||

| F LCP-Tac_PM | Reference group for Relative Bioavilability (LCP-Tac_CYP3A5*1 non-expresser) | 1 FIX | - | - | ||

| F IR-Tac_PM | Relative bioavailability of IR-Tac_ CYP3A5*1 non-expresser compared to reference | 0.745 (7.6%) | 0.757 | 0.66-0.84 | ||

| F LCP-Tac_HM | Relative bioavailability of LCP-Tac_CYP3A5*1 expresser compared to reference | 0.693 (13.7%) | 0.695 | 0.52-0.85 | ||

| F IR-Tac_HM | Relative bioavailability of IR-Tac_ CYP3A5*1 expresser compared to reference | 0.427 (13.4%) | 0.428 | 0.34-0.52 | ||

| Lag-Time IR-Tac(h) | lag time for IR-Tac formulation in hours | 0.465 (0.1%) | 0.465 | 0.42-0.47 | ||

| Lag-Time LCP-Tac(h) | lag time for LCP-Tac formulation in hours | 1.4 (2.4%) | 1.39 | 1.32-1.57 | ||

| Circadian rhythms parameters | ||||||

| AcrophaseCL/F (h) | peak time of the cosine function | 17 (3.6%) | 16.94 | 15.94-17.98 | ||

| AmpCL/F | Amplitude | 3.42 (17.1%) | 3.41 | 2.33-4.39 | ||

| Acrophaseka (h) | peak time of the cosine function | 3.13 (18.3%) | 3.17 | 1.82-4.52 | ||

| Ampka | Amplitude | 1.55 (44.5%) | 1.64 | 0.91-2.97 | ||

| RE. (-) | Combined residual error | 13.30 (8.2%) | 13.11 | 11.83-14.14 | ||

| Interindividual patient variability | Description |

CV% (RSE %) |

||||

| IIVCL/F | IIV associated with Elimination Clearance | 26.49 (29.1%) | 25.49 | 18.7-31.14 | ||

| IIV Vc/F | IIV associated with Distribution Volume of central compartment | 53.47 (42%) | 52.15 | 33.46-72.20 | ||

| Vc/F / Ka IR-Tac Correlation | Correlation between IIV of Vc/F and Ka of IR-Tac | 75.63(16%) | 72.3 | 43-92.33 | ||

| Vc/F / Ka LCP-Tac Correlation | Correlation between IIV of Vc/F and Ka of LCP-Tac | 44.38(10%) | 44.11 | 12.76-65.68 | ||

| IIV Ka IR-Tac | IIV associated with Absorption rate constant (IR-Tac) | 150.66 (25.6%) | 146.62 | 87.6-184.44 | ||

| Ka IR-Tac/ Ka LCP-Tac Correlation | Correlation between IIV of Ka IR-Tac and Ka LCP-Tac | 45(20.3%) | 41.24 | 38.69-75.55 | ||

| IIV Ka LCP_Tac | IIV associated with Absorption rate constant (LCP-Tac) | 67.23 (46.5%) | 72.25 | 46.96-88.67 | ||

| IOVCL | IOV associated with Elimination Clearance | 20.85 (23.9%) | 20 | 16.9-24.51 | ||

| IOV Vc | IOV associated with Distribution Volume of central compartment | 58.82 (28.9%) | 58.05 | 38.47-72 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).