Submitted:

28 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Primary Exposure Variables

Study Outcomes

Statistical Analyses

Results

Discussion

Authors contributions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Choy, K.T.; Lam, K.; Kong, J.C. Exercise and colorectal cancer survival: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2022, 37, 1751–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drageset, S.; Lindstrøm, T.C.; Underlid, K. “I just have to move on”: Women’s coping experiences and reflections following their first year after primary breast cancer surgery. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 21, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.M.; Nagle, C.M.; Ibiebele, T.I.; Grant, P.T.; Obermair, A.; Friedlander, M.L.; DeFazio, A.; Webb, P.M. ; Ovarian Cancer Prognosis Lifestyle Study Group Ahealthy lifestyle survival among women with ovarian cancer Int, J. Cancer 2020, 147, 3361–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, M.L.; Buys, S.S.; Gren, L.H.; Simonsen, S.E.; Kirchhoff, A.C.; Hashibe, M. Do cancer survivors develop healthier lifestyle behaviors than the cancer-free population in the PLCO study? J. Cancer Surviv. 2017, 11, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanera, I.M.; Bolman, C.A.W.; Mesters, I.; Willems, R.A.; Beaulen, A.A.J.M.; Lechner, L. Prevalence and correlates of healthy lifestyle behaviors among early cancer survivors. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollosa, D.N.; Holliday, E.; Hure, A.; Tavener, M.; James, E.L. Multiple health behaviors before and after a cancer diagnosis among women: A repeated cross-sectional analysis over 15 years. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 3224–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsay, S.-L.; Ko, W.-S.; Lin, K.-P. The Lifestyle Change Experiences of Cancer Survivors. J. Nurs. Res. 2017, 25, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Aziz, N.M.; Rowland, J.H.; Pinto, B.M. Riding the Crest of the Teachable Moment: Promoting Long-Term Health After the Diagnosis of Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 5814–5830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paek, J.; Son, S.; Choi, Y.J. E-cigarette and cigarette use among cancer survivors versus general population: a case-control study in Korea. J. Cancer Surviv. 2021, 16, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Hyun, N.; Leach, C.R.; Yabroff, K.R.; Jemal, A. Association of First Primary Cancer With Risk of Subsequent Primary Cancer Among Survivors of Adult-Onset Cancers in the United States. JAMA 2020, 324, 2521–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, M.L.; EBlackburn, B.; Rowe, K.; Snyder, J.; Deshmukh, V.G.; Newman, M.; Fraser, A.; Smith, K.; Herget, K.; AGanz, P.; et al. Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases Among Colorectal Cancer Survivors in a Population-Based Cohort. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 112, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Liu, Z.; Thong, M.S.Y.; Doege, D.; Arndt, V. Higher Incidence of Diabetes in Cancer Patients Compared to Cancer-Free Population Controls: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2022, 14, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHOO WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2020; pp. 1–582.

- Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Rogers, L.Q.; Alfano, C.M.; Thomson, C.A.; Courneya, K.S.; Meyerhardt, J.A.; Stout, N.L.; Kvale, E.; Ganzer, H.; Ligibel, J.A. Practical clinical interventions for diet, physical activity, and weight control in cancer survivors. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2015, 65, 167–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lux, M.P.; Fasching, P.A.; Beckmann, M.W. Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: review and future perspectives. J. Mol. Med. 2005, 84, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, R.; Sheahan, K.; O’Connell, P.R.; Hanly, A.M.; Martin, S.T.; Winter, D.C. Lynch Syndrome: An Updated Review. Genes 2014, 5, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- On behalf of the SEOMHereditary Cancer Working, G.r.o.u.p.; Llort, G.; Chirivella, I.; Morales, R.; Serrano, R.; Sanchez, A.B.; Teulé, A.; Lastra, E.; Brunet, J.; Balmaña, J.; et al. SEOM clinical guidelines in Hereditary Breast and ovarian cancer. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2015, 17, 956–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, F.C.C.; Valentin, M.D.; Ferreira, F.d.O.; Carraro, D.M.; Rossi, B.M. Mismatch repair genes in Lynch syndrome: a review. Sao Paulo Med J. 2009, 127, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, P.; Seppälä, T.; Bernstein, I.; Holinski-Feder, E.; Sala, P.; Evans, D.G.; Lindblom, A.; Macrae, F.; Blanco, I.; Sijmons, R.; et al. Cancer incidence and survival in Lynch syndrome patients receiving colonoscopic and gynaecological surveillance: first report from the prospective Lynch syndrome database. Gut 2015, 66, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadder, N.J.; Giridhar, K.V.; Baffy, N.; Riegert-Johnson, D.; Couch, F.J. Hereditary cancer syndromes—A primer on diagnosis and management: Part 1: Breast-ovarian cancer syndromes. Mayo Clinic Proceedings; 2019: Elsevier.

- Howlader, N.; Noone, A.; Krapcho, M.; Miller, D.; Brest, A.; Yu, M.; et al. Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2016. National Cancer Institute. 2019.

- Kuchenbaecker, K.B.; Hopper, J.L.; Barnes, D.R.; Phillips, K.A.; Mooij, T.M.; Roos-Blom, M.J.; Jervis, S.; van Leeuwen, F.E.; Milne, R.L.; Andrieu, N.; Goldgar, D.E.; et al. Risks of breast, ovarian, and contralateral breast cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. JAMA. 2017, 317, 2402–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniou, A.; Pharoah, P.D.; Narod, S.; Risch, H.A.; Eyfjord, J.E.; Hopper, J.L.; Loman, N.; Olsson, H.; Johannsson, O.; Borg, A.; et al. Average Risks of Breast and Ovarian Cancer Associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutations Detected in Case Series Unselected for Family History: A Combined Analysis of 22 Studies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003, 72, 1117–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, E.; Hill, J.; Evans, D.G. Cancer risk in Lynch Syndrome. Fam. Cancer 2013, 12, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Barry, W.T.; Seah, D.S.; Tung, N.M.; Garber, J.E.; Lin, N.U. Patterns of recurrence and metastasis in BRCA1/BRCA2-associated breast cancers. Cancer. 2020, 126, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraldsdottir, S.; Hampel, H.; Wu, C.; Weng, D.Y.; Shields, P.G.; Frankel, W.L.; Pan, X.; de la Chapelle, A.; Goldberg, R.M.; Bekaii-Saab, T. Patients with colorectal cancer associated with Lynch syndrome and MLH1 promoter hypermethylation have similar prognoses. Anesthesia Analg. 2016, 18, 863–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, H.; Marty, R.; Hofree, M.; Gross, A.M.; Jensen, J.; Fisch, K.M.; Wu, X.; DeBoever, C.; Van Nostrand, E.L.; Song, Y.; et al. Interaction landscape of inherited polymorphisms with somatic events in cancer. Cancer discovery. 2017, 7, 410–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Mukherjee, A.; Machiela, M.J.; Song, L.; Hua, X.; Shi, J.; Garcia-Closas, M.; Chanock, S.J.; Chatterjee, N. An investigation of the association of genetic susceptibility risk with somatic mutation burden in breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 115, 752–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodily, W.R.; Shirts, B.H.; Walsh, T.; Gulsuner, S.; King, M.-C.; Parker, A.; Roosan, M.; Piccolo, S.R.; Galli, A. Effects of germline and somatic events in candidate BRCA-like genes on breast-tumor signatures. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0239197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.H.; Sokolova, A.O.; Schaeffer, E.M.; Small, E.J.; Higano, C.S. Germline and Somatic Mutations in Prostate Cancer for the Clinician. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2019, 17, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasanisi, P.; Bruno, E.; Venturelli, E.; Morelli, D.; Oliverio, A.; Baldassari, I.; Rovera, F.; Iula, G.; Taborelli, M.; Peissel, B.; et al. A Dietary Intervention to Lower Serum Levels of IGF-I in BRCA Mutation Carriers. Cancers 2018, 10, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, P.; Iyengar, N.M.; Zahid, H.; Carter, K.M.; Byun, D.J.; Choi, M.H.; Sun, Q.; Savenkov, O.; Louka, C.; Liu, C.; et al. Obesity promotes breast epithelium DNA damage in women carrying a germline mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2. Sci. Transl. Med. 2023, 15, eade1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniele, A.; Divella, R.; Pilato, B.; Tommasi, S.; Pasanisi, P.; Patruno, M.; Digennaro, M.; Minoia, C.; Dellino, M.; Pisconti, S.; et al. Can harmful lifestyle, obesity and weight changes increase the risk of breast cancer in BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 mutation carriers? A Mini review. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pr. 2021, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndt, S.I.; Platz, E.A.; Fallin, M.D.; Thuita, L.W.; Hoffman, S.C.; Helzlsouer, K.J. Mismatch repair polymorphisms and the risk of colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2007, 120, 1548–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friebel, T.M.; Domchek, S.M.; Rebbeck, T.R. Modifiers of Cancer Risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, dju091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, M.; Lynch, P.M.; Hopper, J.L.; Jenkins, M.A.; Gallinger, S.; Haile, R.W.; LeMarchand, L.; Lindor, N.M.; Campbell, P.T.; Newcomb, P.A.; et al. Smoking and Colorectal Cancer in Lynch Syndrome: Results from the Colon Cancer Family Registry and The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 1331–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Duijnhoven, F.J.B.; Botma, A.; Winkels, R.; Nagengast, F.M.; Vasen, H.F.A.; Kampman, E. Do lifestyle factors influence colorectal cancer risk in Lynch syndrome? Fam. Cancer 2013, 12, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coletta, A.M.; Peterson, S.K.; Gatus, L.A.; Krause, K.J.; Schembre, S.M.; Gilchrist, S.C.; Arun, B.; You, Y.N.; Rodriguez-Bigas, M.A.; Strong, L.L.; et al. Diet, weight management, physical activity and Ovarian & Breast Cancer Risk in women with BRCA1/2 pathogenic Germline gene variants: systematic review. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 2020, 18, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Coletta, A.M.; Peterson, S.K.; Gatus, L.A.; Krause, K.J.; Schembre, S.M.; Gilchrist, S.C.; Pande, M.; Vilar, E.; You, Y.N.; Rodriguez-Bigas, M.A.; et al. Energy balance related lifestyle factors and risk of endometrial and colorectal cancer among individuals with lynch syndrome: a systematic review. Fam. Cancer 2019, 18, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehm, R.D.; Genkinger, J.M.; MacInnis, R.J.; John, E.M.; Phillips, K.A.; Dite, G.S.; Milne, R.L.; Zeinomar, N.; Liao, Y.; Knight, J.A.; et al. Recreational physical activity is associated with reduced breast cancer risk in adult women at high risk for breast cancer: a cohort study of women selected for familial and genetic risk. Cancer Research. 2020, 80, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sievänen, T.; Törmäkangas, T.; Laakkonen, E.K.; Mecklin, J.P.; Pylvänäinen, K.; Seppälä, T.T.; Peltomäki, P.; Sipilä, S.; Sillanpää, E. Body weight, physical activity, and risk of cancer in Lynch syndrome. Cancers 2021, 13, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miguchi, M.; Hinoi, T.; Tanakaya, K.; Yamaguchi, T.; Furukawa, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Tamura, K.; Sugano, K.; Ishioka, C.; Matsubara, N.; et al. Alcohol consumption and early-onset risk of colorectal cancer in Japanese patients with Lynch syndrome: a cross-sectional study conducted by the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Surg. Today 2018, 48, 810–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashti, S.G.; Buchanan, D.D.; Jayasekara, H.; Ait Ouakrim, D.; Clendenning, M.; Rosty, C.; Winship, I.M.; Macrae, F.A.; Giles, G.G.; Parry, S.; et al. Alcohol Consumption and the Risk of Colorectal Cancer for Mismatch Repair Gene Mutation CarriersAlcohol Intake and Colorectal Cancer Risk in Lynch Syndrome. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2017, 26, 366–375. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. ; Terry MB, Antoniou AC, Phillips KA, Kast K, Mooij TM, Engel C, Noguès C, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Lasset C, et, a. l. Alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and risk of breast cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from The BRCA1 and BRCA2 Cohort Consortium. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2020, 29, 368–378. [Google Scholar]

- Botma, A.; Nagengast, F.M.; Braem, M.G.; Hendriks, J.C.; Kleibeuker, J.H.; Vasen, H.F.; Kampman, E. Body Mass Index Increases Risk of Colorectal Adenomas in Men With Lynch Syndrome: The GEOLynch Cohort Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 4346–4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

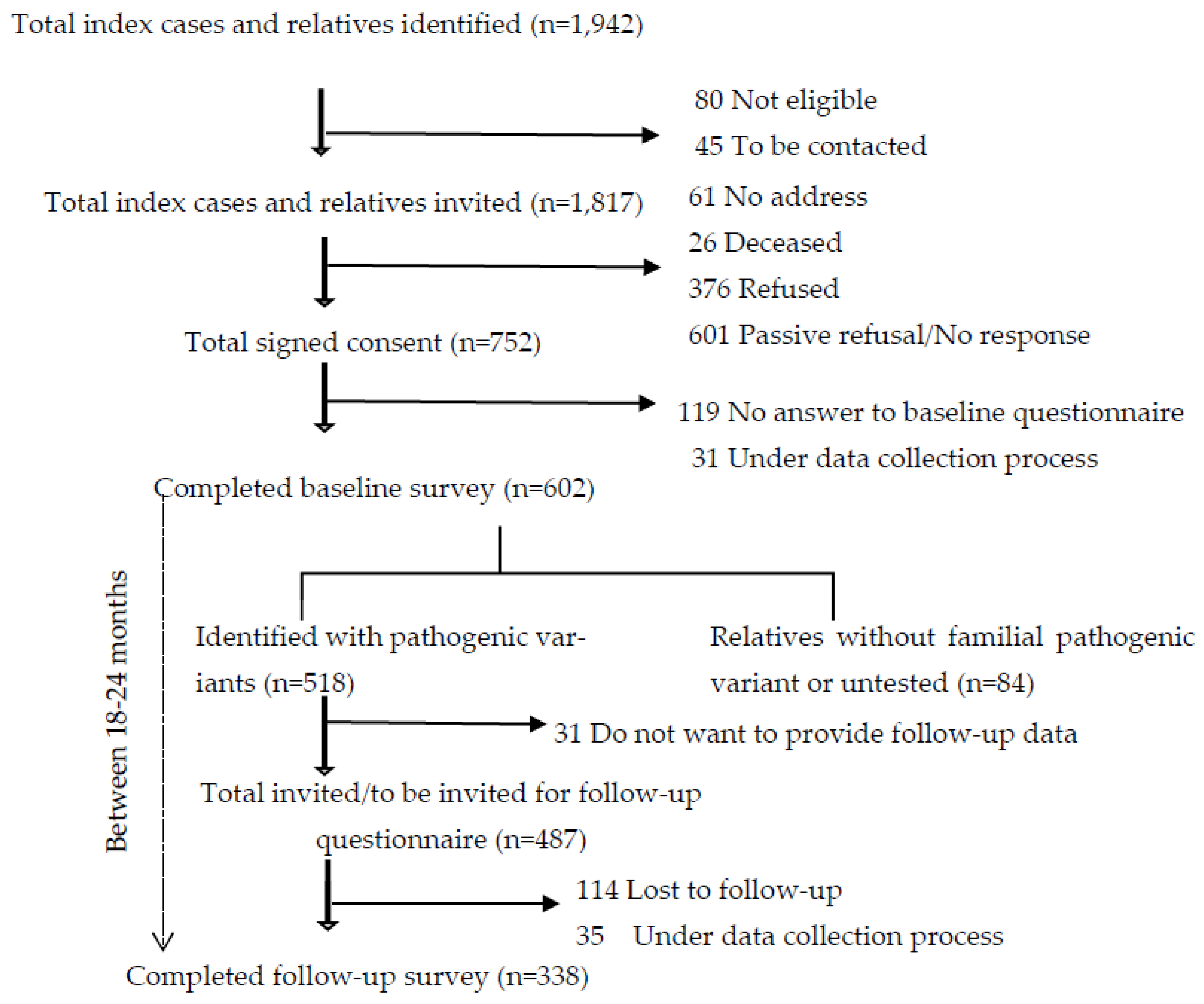

- Katapodi, M.C.; Viassolo, V.; Caiata-Zufferey, M.; Nikolaidis, C.; Bührer-Landolt, R.; Buerki, N.; Graffeo, R.; Horváth, H.C.; Kurzeder, C.; Rabaglio, M.; et al. Cancer Predisposition Cascade Screening for Hereditary Breast/Ovarian Cancer and Lynch Syndromes in Switzerland: Study Protocol. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2017, 6, e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevention CfDCa. Healthy Weight, Nutrition, and Physical Activity: About Adult BMI 2023 [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html#:~:text=Body%20mass%20index%20(BMI)%20is,weight%2C%20overweight%2C%20and%20obesity.

- Dashti, S.G.; Win, A.K.; Hardikar, S.S.; Glombicki, S.E.; Mallenahalli, S.; Thirumurthi, S.; Peterson, S.K.; You, Y.N.; Buchanan, D.D.; Figueiredo, J.C.; et al. Physical activity and the risk of colorectal cancer in Lynch syndrome. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 143, 2250–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultekin, S.C.; Cakir, A.B.; Guc, Z.G.; Ozalp, F.R.; Keskinkilic, M.; Yavuzsen, T.; Yavuzsen, H.T.; Karadibak, D. The comparison of functional status and health-related parameters in ovarian cancer survivors with healthy controls. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luctkar-Flude, M.F.; Groll, D.L.; Tranmer, J.E.; Woodend, K. Fatigue and physical activity in older adults with cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Cancer Nursing. 2007, 30, E35–E45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsunaga, M.; He, Y.; Khine, M.T.; Shi, X.; Okegawa, R.; Li, Y.; Yatsuya, H.; Ota, A. Prevalence, severity, and risk factors of cancer-related fatigue among working cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. J. Cancer Surviv. 2024, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koper, M.; Bochenek, O.; Nowak, A.; Kałuża, J.; Konaszczuk, A.; Ratyna, K.; Kozyra, O.; Szypuła, Z.; Paluch, K.; Skarbek, M. From Diagnosis to Recovery: The Life-Changing Benefits of Exercise for Cancer Patients. Qual. Sport 2024, 20, 54212–54212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeganeh, L.; Willey, S.; Wan, C.S.; Khomami, M.B.; Chehrazi, M.; Cook, O.; Webber, K. The effects of lifestyle and behavioural interventions on cancer recurrence, overall survival and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Maturitas 2024, 185, 107977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, K.-Y.; Min, J.; Lee, D.H.; Kang, D.-W.; Courneya, K.S.; Jeon, J.Y. Exercise Across the Phases of Cancer Survivorship: A Narrative Review. Yonsei Med J. 2024, 65, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakob, J.; Cornuz, J.; Diethelm, P. Prevalence of tobacco smoking in Switzerland: do reported numbers underestimate reality? Swiss Medical Weekly. 2017, 147, w14437. [Google Scholar]

- Suter, F.; Pestoni, G.; Sych, J.; Rohrmann, S.; Braun, J. Alcohol consumption: context and association with mortality in Switzerland. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 62, 1331–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karavasiloglou, N.; Pestoni, G.; Pannen, S.T.; Schönenberger, K.A.; Kuhn, T.; Rohrmann, S. How prevalent is a cancer-protective lifestyle? Adherence to the 2018 World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research cancer prevention recommendations in Switzerland. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 130, 904–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, R.F.; Doherty, D.E.; Horgan, R.; Fahey, P.; Gallagher, D.J.; Lowery, M.A.; Cadoo, K.A. Modifiable risk factors and risk of colorectal and endometrial cancers in Lynch Syndrome: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, e2300196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gersekowski, K.; Na, R.; Alsop, K.; Delahunty, R. ; Goode EL, Cunningham JM, Winham SJ, Pharoah PDP, Song H,Webb, P. M. Risk factors for ovarian cancer by BRCA status: a collaborative case-only analysis. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2024, 33, 586–592. [Google Scholar]

- Conte, L.; Rizzo, E.; Civino, E.; Tarantino, P.; De Nunzio, G.; De Matteis, E. Enhancing Breast Cancer Risk Prediction with Machine Learning: Integrating BMI, Smoking Habits, Hormonal Dynamics, and BRCA Gene Mutations—A Game-Changer Compared to Traditional Statistical Models? Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.E.; Schoemaker, M.J.; Wright, L.B.; Ashworth, A.; Swerdlow, A.J. Smoking and risk of breast cancer in the Generations Study cohort. Breast Cancer Res. 2017, 19, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office, F.S. Swiss Health Survey 2017: alcohol consumption. 2019 10th August 2024.

- Church, D.N. More than just a hangover – alcohol and carcinogenesis in Lynch syndrome. Dis. Model. Mech. 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiyoshi, K.; Sudo, T.; Fujita, F.; Chino, A.; Akagi, K.; Takao, A.; Yamada, M.; Tanakaya, K.; Ishida, H.; Komori, K. Risk of first onset of colorectal cancer associated with alcohol consumption in Lynch syndrome: a multicenter cohort study. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 27, 1051–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zutshi, M.; Hull, T.; Shedda, S.; Lavery, I.; Hammel, J. Gender differences in mortality, quality of life and function after restorative procedures for rectal cancer. Color. Dis. 2012, 15, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office, F.S. Swiss Health Survey 2017: overweight and obesity. 2020.

- Botma, A.; Nagengast, F.M.; Braem, M.G.; Hendriks, J.C.; Kleibeuker, J.H.; Vasen, H.F.; Kampman, E. Body Mass Index Increases Risk of Colorectal Adenomas in Men With Lynch Syndrome: The GEOLynch Cohort Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 4346–4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, P.T.; Cotterchio, M.; Dicks, E.; Parfrey, P.; Gallinger, S.; McLaughlin, J.R. Excess Body Weight and Colorectal Cancer Risk in Canada: Associations in Subgroups of Clinically Defined Familial Risk of Cancer. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers Prev. 2007, 16, 1735–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, R.H. The Complex Role of Estrogens in Inflammation. Endocr. Rev. 2007, 28, 521–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, L.R.; Bulun, S.E. Estrogen production and action. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2001, 45, S116–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeners, B.; Geary, N.; Tobler, P.N.; Asarian, L. Ovarian hormones and obesity. Hum. Reprod. Updat. 2017, 23, 300–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Parmigiani, G. Meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007, 25, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassour, A.-J.; Jain, A.; Hui, N.; Siopis, G.; Symons, J.; Woo, H. Relative Risk of Bladder and Kidney Cancer in Lynch Syndrome: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2023, 15, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Overall number of observations N=856 (%) |

Observations from individuals never diagnosed with cancer N=357 (%) |

Observations from individuals with at least one cancer diagnosis a N=499 (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 157 (18.3) | 90 (25.2%) | 67 (13.4%) | <0.01b |

| Female | 699 (81.7) | 267 (74.8%) | 432 (86.6%) | <0.01 b |

| Age [mean, (SD)], years | 51.4 (13.1) | 45.8 (13.1) | 55.3 (11.4) | <0.01c |

| Syndrome | ||||

| HBOC | 680 (79.4) | 305 (85.4%) | 375 (75.2%) | <0.01 b |

| LS | 176 (20.6) | 52 (14.6%) | 124 (24.8%) | <0.01 b |

| Median time since genetic testing (Q1-Q3), years | 3.41 (2.00-6.30) | 3.00 (1.93-5.65) | 3.73 (2.01-6.71) | 0.0042c |

| Median number of cancer diagnosis (Q1-Q3), (range) | - | - | 1 (1 – 1) | |

| Median time since first cancer diagnosis (Q1-Q3), years | - | - | 6.00 (3.0 -12.28) | |

| Health Behaviors | ||||

| Current smoking (missing=3) | ||||

| Yes | 105 (12.3) | 49 (13.7%) | 56 (11.2%) | 0.07b |

| No | 748 (87.4) | 308 (86.3%) | 440 (88.2% | 0.47 b |

| Average number of cigarettes [mean, (SD)] smoked per week | 72.24 (64.17) | 51.90 (40.45) | 90.7 (75.59) | 0.31 d |

| Alcohol (missing=12) | ||||

| Never (0) | 258 (30.1) | 81 (22.7%) | 177 (35.5%) | <0.01 b |

| Light (1-2/week) | 379 (44.3) | 173 (48.5%) | 206 (41.3%) | 0.04 b |

| Moderate (3-5/week) | 130 (15.2) | 65 (18.2%) | 65 (13.0%) | 0.05b |

| Heavy (≥6/week) | 77 (9.0) | 28 (7.8%) | 49 (9.8%) | 0.38 b |

| Average number of alcoholic beverages [mean, (SD)] per week (missing=12) | 2.31 (3.77) | 2.42 (3.59) | 2.23 (3.89) | 0.47 d |

| Physical activity (missing=12) | ||||

| No exercise (0) | 97 (11.3) | 31 (8.7%) | 66 (13.2%) | 0.05b |

| Light exercise (1/week) | 240 (28.0) | 97 (27.2%) | 143 (28.7%) | 0.69 b |

| Moderate exercise (2-3/week) | 358 (41.8) | 171 (47.9%) | 187 (37.5%) | 0.002 b |

| Heavy exercise (≥4/week) | 149 (17.4) | 56 (15.7%) | 93 (18.6%) | 0.30 b |

| Median hours of physical activity (IQRe) per week (missing=55) | 1.00 (0.3-2.0) | 1.0 (0.5 – 2.0) | 1.0 (0.25 – 2.0) | 0.05c |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5 kgm-2), | 30 (3.5) | 10 (2.8%) | 20 (4.0%) | 0.44 b |

| Normal weight (18.5-24.9 kgm-2) | 498 (58.2) | 211 (59.1%) | 287 (57.5%) | 0.69 b |

| Overweight (25.0-29.9 kgm-2) | 215 (25.1) | 97 (27.2%) | 118 (23.6%) | 0.27 b |

| Obese (≥30 kgm-2) | 91 (10.6) | 28 (7.8%) | 63 (12.6%) | 0.03 b |

| Median BMI (Q1-Q3) (missing=22), kgm-2 | 23.6 (21.3-27.1) | 23.4 (21.3 -26.5) | 23.9 (21.2 – 27.4) | 0.43c |

| Smoking | Alcohol | Physical activity | Body Mass Index (BMI) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current smoking status (yes or no) a |

Average number of cigarettes smoked per week c | Alcohol intake group (never, light, moderate, heavy) b |

Average number of alcoholic beverages per week c |

Physical activity group (no exercise, light, moderate, heavy) b |

Average hours of physical activity per week c |

BMI (underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese) b | BMI c | |||||||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | Est. | Std.er. | p | OR | 95% CI | Est. | Std.er. | p | OR | 95% CI | Est. | Std.er. | p | OR | 95% CI | Est. | Std.er. | p | |

| Cancer diagnosis | 0.8 | 0.10-6.0 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 0.38 | 0.5 | 0.2-1.3 | -0.2 | 0.3 | 0.49 | 0.81 | 0.6-1.1 | -0.37 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.8 | 0.2-3.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Smoking | Alcohol | Physical activity | Body Mass Index (BMI) | |||||||||||||||||

| Current smoking status (yes or no) a |

Average number of cigarettes smoked per week c | Alcohol intake group (never, light, moderate, heavy) b |

Average number of alcoholic beverages per week c |

Physical activity group (no exercise, light, moderate, heavy) b |

Average hours of physical activity per week c |

BMI group (underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese) b | BMI c | |||||||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | Est. | Std.er. | p | OR | 95% CI | Est. | Std.er. | p | OR | 95% CI | Est. | Std.er. | p | OR | 95% CI | Est. | Std.er. | p | |

| Cancer diagnosis | 1.05 | 0.01-11.1 | 4.5 | 3.3 | 0.18 | 0.36 | 0.11-1.20 | -0.2 | 0.3 | 0.51 | 0.7 | 0.5-1.1 | -0.5 | 0.2 | 0.02 | 0.83 | 0.32-2.13 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.43 |

| Age in years | 0.97 | 0.9-1.1 | -0.2 | 0.1 | 0.24 | 1.03 | 0.99-1.08 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 1.01 | 1.0-1.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.93 | 0.92-0.93 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Female (ref: male) |

0.59 | 0.03-10.6 | -3.3 | 4.4 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.11-2.24 | -1.2 | 0.4 | <0.01 | 1.0 | 0.6-1.7 | -0.05 | 0.3 | 0.85 | - | - | -1.8 | 0.6 | 0.002 |

| HBOC (ref: LS) |

1.09 | 0.08-15.7 | 2.9 | 4.0 | 0.47 | 0.55 | 0.12-2.51 | -0.70 | 0.4 | 0.10 | 0.8 | 0.5-1.2 | 0.20 | 0.2 | 0.38 | - | - | -0.2 | 0.5 | 0.64 |

| Time since genetic testing | 1.00 | 0.8-1.3 | -0.1 | 0.3 | 0.67 | 1.13 | 0.99-1.29 | 0.09 | 0.03 | <0.01 | 1.01 | 1.0-1.05 | -0.01 | 0.02 | 0.87 | - | - | -0.04 | 0.04 | 0.60 |

| Average number of cigarettes smoked per week | Average number of alcoholic beverages per week | Average hours of physical activity per week | Body Mass Index | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | Std.er. | p | Est. | Std.er. | p | Est. | Std.er. | p | Est. | Std.er. | p | |

| Female (ref: male) | -7.8 | 5.5 | 0.16 | -0.7 | 0.6 | 0.24 | -0.3 | 0.3 | 0.32 | -2.3 | 0.7 | 0.01 |

| Time since genetic testing | -1.1 | 0.6 | 0.08 | 0.2 | 0.07 | <0.01 | -0.02 | 0.04 | 0.66 | -0.01 | 0.07 | 0.21 |

| Female * time since genetic testing | 1.04 | 0.7 | 0.14 | -0.1 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.62 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.36 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).