Submitted:

28 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

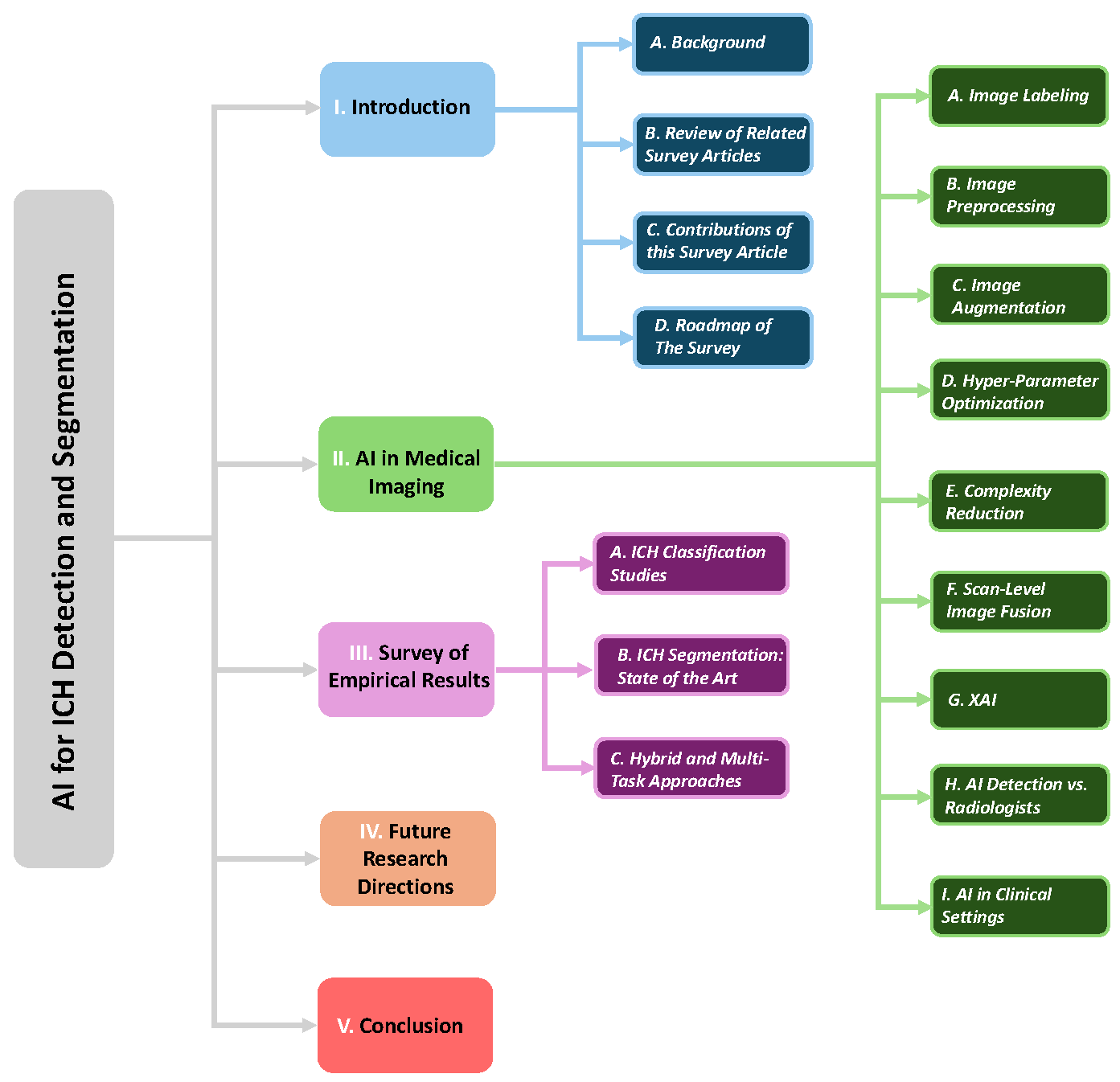

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Review of Related Survey Articles

1.3. Contributions of this Survey Article

- The comprehensive AI pipeline covers everything from annotation and preprocessing to model design, optimization, and deployment.

- The study presents an in-depth review of scan-level image fusion (SLIF), including MIL, attention-based, and fuzzy fusion methods for robust scan-level prediction.

- The comparison of AI-based detection and radiologist interpretation highlights their strengths, limitations, and complementary roles.

- The dual focus on tasks provides balanced coverage of ICH detection (classification), segmentation, and localization studies.

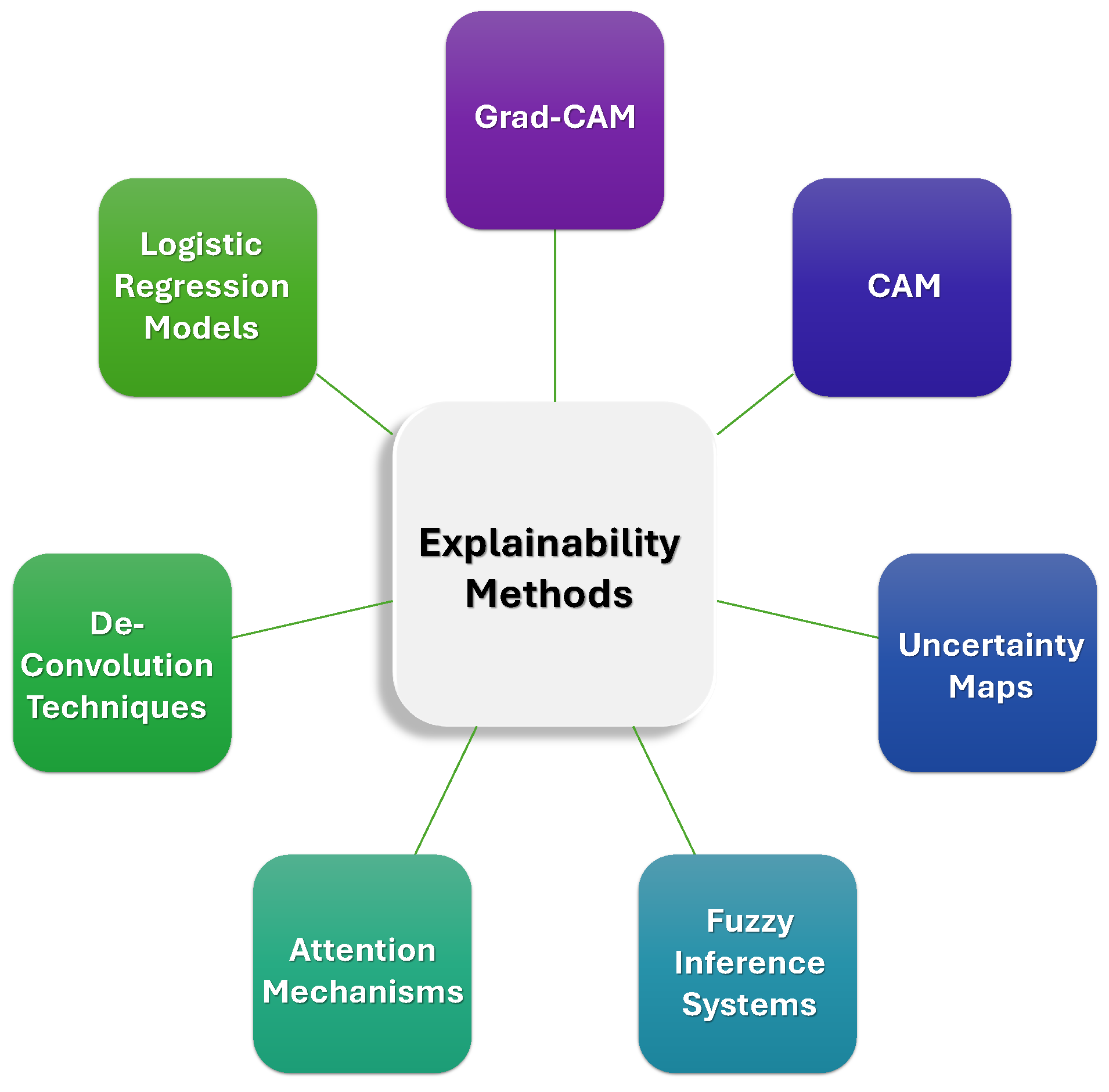

- XAI involves the evaluation of Grad-CAM, uncertainty maps, attention mechanisms, and fuzzy logic to enhance clinical interpretability.

- Clinical integration includes a review of FDA-cleared tools, PACS integration, and AI-assisted triage in real-world settings.

1.4. Roadmap of The Survey

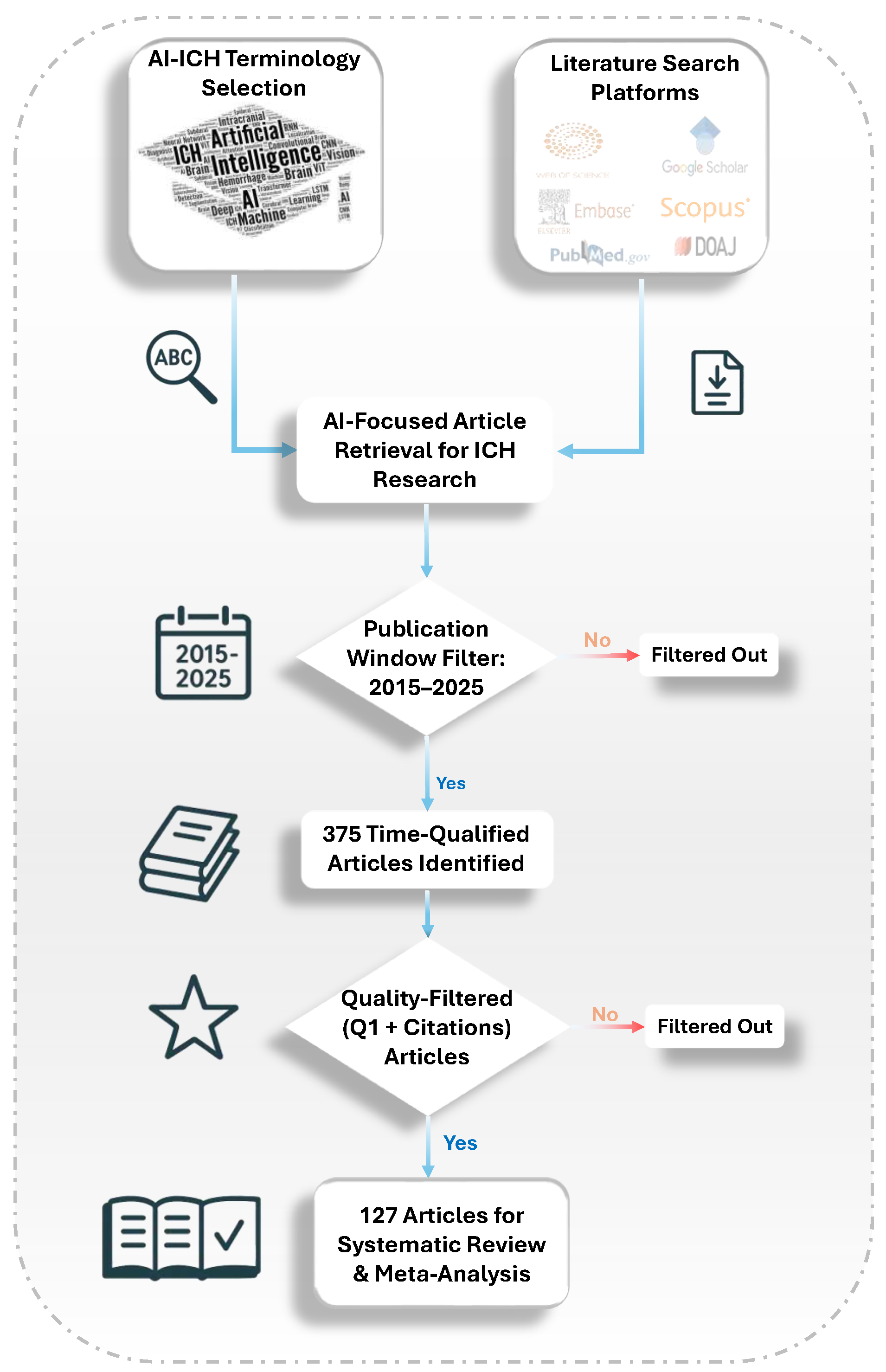

2. AI in Medical Imaging: Techniques, Challenges, and Applications

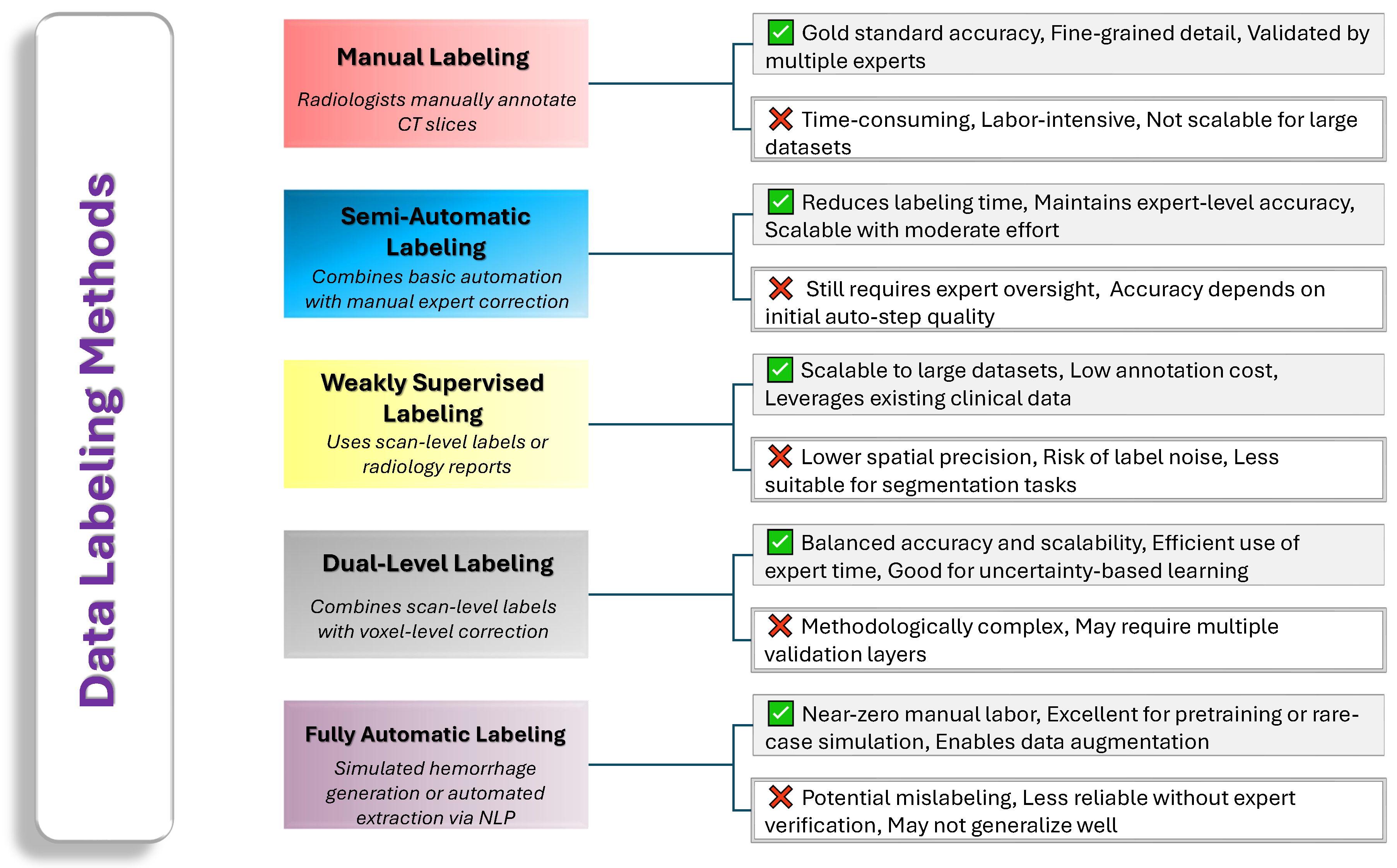

2.1. Image Labeling

- Our Insights: Manual annotations remain the gold standard for accuracy but are expensive and time-consuming. Semi-automatic, weakly supervised, and hybrid approaches aim to ease this burden by leveraging computational tools or scan-level information while still preserving acceptable labeling quality. Ultimately, each method carries its own trade-offs in terms of complexity, cost, and accuracy. Future research will likely focus on refining automated techniques, validating them against expert references, and implementing uncertainty-aware strategies to achieve both high efficiency and high fidelity in labeling ICH data. Figure 4 provides a comparative overview of common data labeling strategies used in ICH research.

2.2. Image Preprocessing

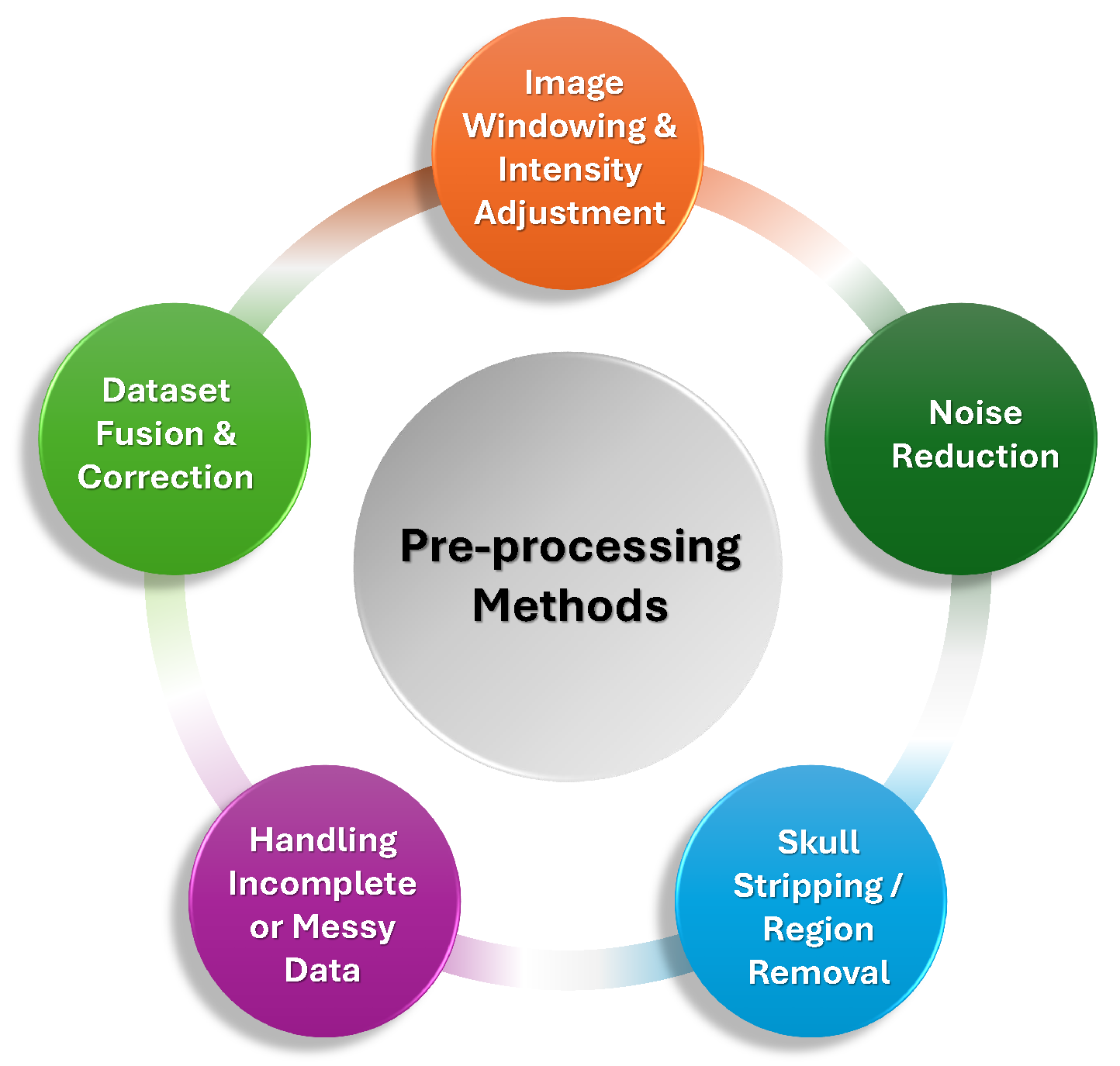

- –

- Image Windowing and Intensity Adjustments: A common technique employed in multiple studies was the use of windowing, which involved adjusting the contrast of CT images to highlight different tissue types. The brain, bone, and subdural windows were frequently used to emphasize hemorrhage detection and reduce irrelevant background noise. These window settings helped optimize the visibility of critical regions while minimizing false positives in model predictions [50,51,52,53]. Windowing was often followed by intensity normalization to standardize the pixel intensity values, ensuring consistency across CT scans from different imaging centers [73,74,75].

- –

- Noise Reduction and Denoising: Many preprocessing pipelines incorporated denoising techniques, including Gaussian filters, median filters, and morphological operations. These methods helped eliminate noise and small artifacts that could interfere with hemorrhage detection. For example, a study used a Gaussian convolution kernel to smooth the segmentation results, while others applied morphological operations like erosion and dilation to refine the boundaries of hemorrhages and remove small unwanted artifacts [66,76,77]. Moreover, bilateral filtering and Gabor filtering were explored in some studies as effective tools for preserving edges while reducing random noise [26,60].

- –

- Skull Stripping and Region Removal: A critical preprocessing step in many studies was skull stripping, which removed the skull and surrounding tissues to focus the model on intracranial structures. This step was particularly important as it reduced irrelevant variations and computational complexity, thereby improving the accuracy of hemorrhage detection. Methods such as thresholding, morphological operations, and the Otsu method were employed to achieve effective skull and background removal [26,53,74,78,79].

- –

- Handling Incomplete or Messy Data: Many studies also emphasized the importance of addressing incomplete or messy data, particularly in clinical settings where some scans may contain motion artifacts, missing slices, or insufficient contrast. Exclusion of scans with these issues or the use of techniques like adaptive thresholding and slice interpolation helped ensure that only high-quality, relevant data was used for training [59,68,72,77]. Some studies also used specialized strategies such as dataset fusion to integrate information across multiple CT slices and correct misclassified hemorrhage regions [73].

- Our Insights: The preprocessing of CT scan images plays a crucial role in optimizing the quality of data and enhancing the performance of DL models for ICH detection. Techniques such as image windowing, intensity normalization, noise reduction, skull stripping, and handling incomplete data ensure the accuracy of model predictions by removing artifacts, standardizing input data, and improving the clarity of critical regions. These preprocessing steps are vital for creating consistent and high-quality data, which significantly contributes to the efficiency and reliability of ICH detection models. Figure 5 summarizes different preprocessing techniques are commonly applied to enhance the quality and consistency of CT scan images before they are used for model training.

2.3. Image Augmentation

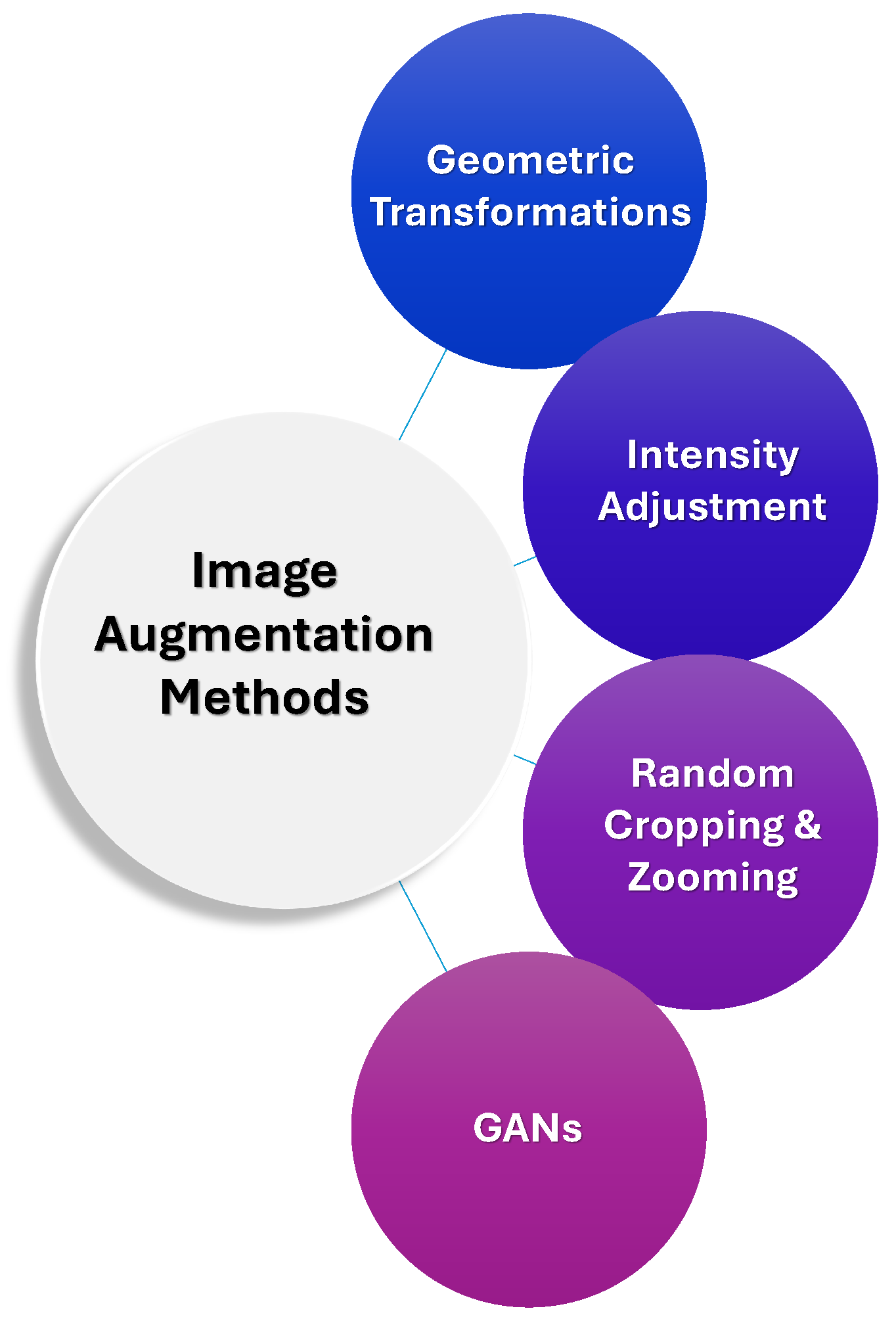

- Our Insights: Data augmentation plays a crucial role in overcoming the challenges of limited labeled medical data, particularly in the context of rare hemorrhage subtypes. By employing techniques such as geometric transformations, intensity adjustments, and advanced methods like GANs and transfer learning, researchers can artificially expand training datasets, improve model generalization, and enhance robustness. These strategies help ensure that models are better equipped to detect hemorrhages across varying imaging conditions, orientations, and qualities, thereby addressing data scarcity, class imbalance, and the risk of overfitting. Ultimately, these augmentation techniques are essential for improving the accuracy and reliability of ICH detection models, especially when high-quality annotated data is scarce. Figure 6 summarizes various data augmentation techniques which are often employed alongside labeling strategies.

2.4. Hyper-Parameter Optimization

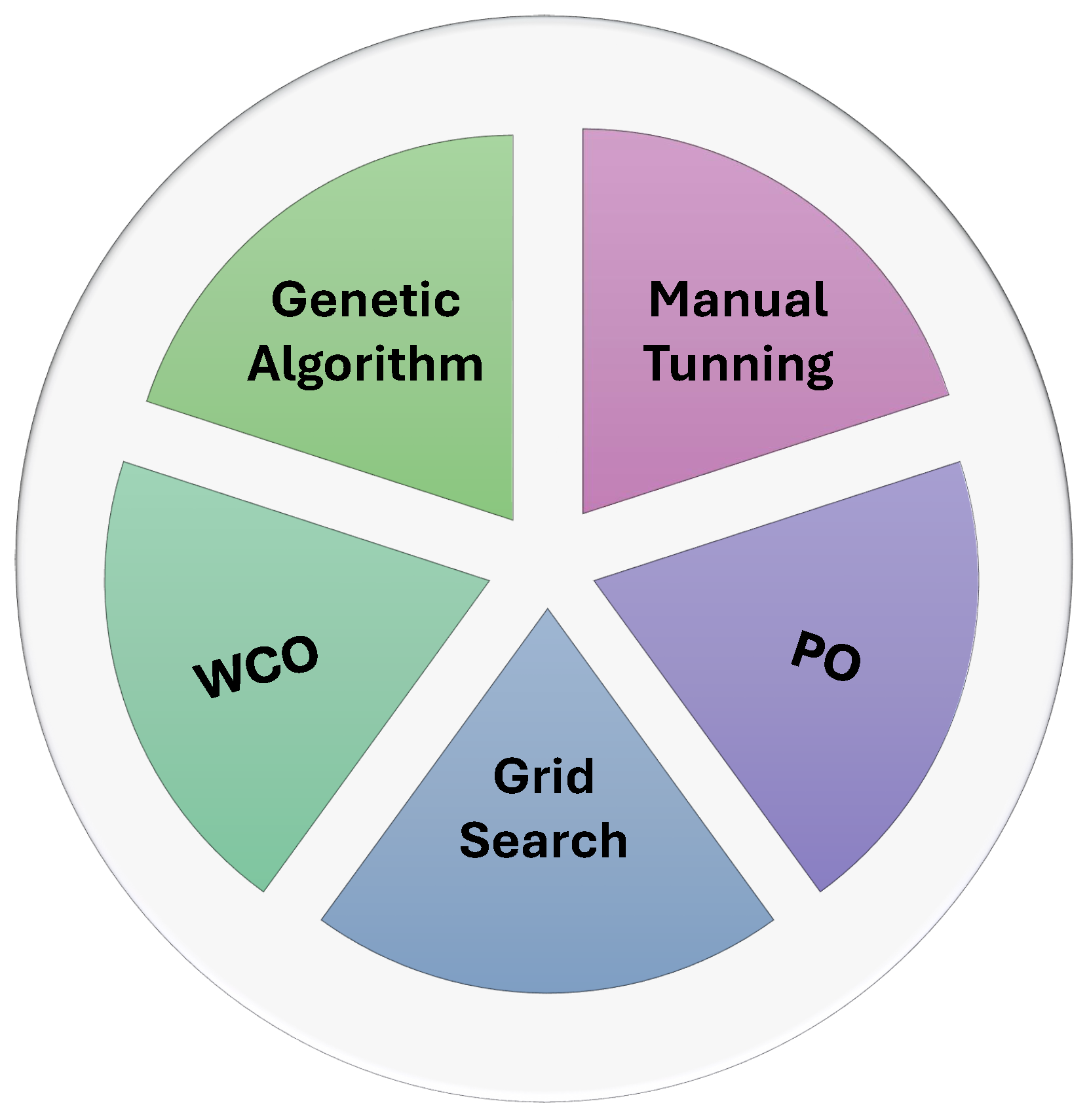

- Our Insights: While manual tuning remains a common approach, more advanced methods like grid search, genetic algorithms, and automated learning rate finders have become increasingly popular due to their ability to efficiently explore large hyperparameter spaces. The integration of metaheuristic algorithms further improves model performance by dynamically adapting hyperparameters, ensuring better accuracy and robustness. Figure 7 summarizes the main hyperparameter optimization techniques employed in AI-based ICH detection models.

2.5. Complexity Reduction

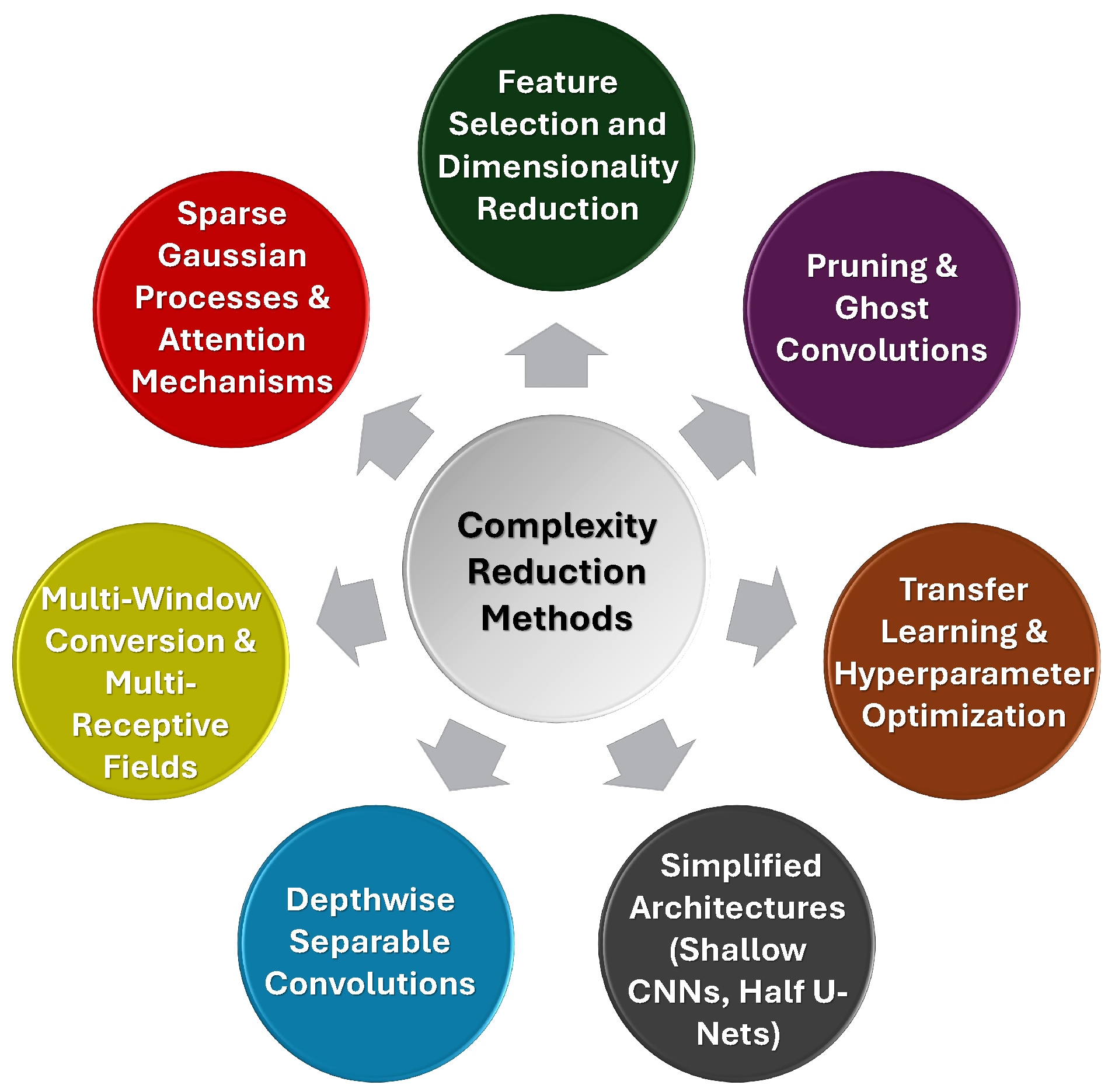

- Our Insights: Techniques such as depthwise separable convolutions, multi-window conversion, voxel and feature selection, pruning, and transfer learning offer effective ways to reduce computational demands without sacrificing diagnostic performance. The ongoing balance between model efficiency and accuracy remains essential, and the use of simpler architectures, optimized for real-time use, continues to be a promising approach for the development of deployable, robust AI models in healthcare settings. Figure 8 summarizes various complexity reduction techniques used in ICH detection models.

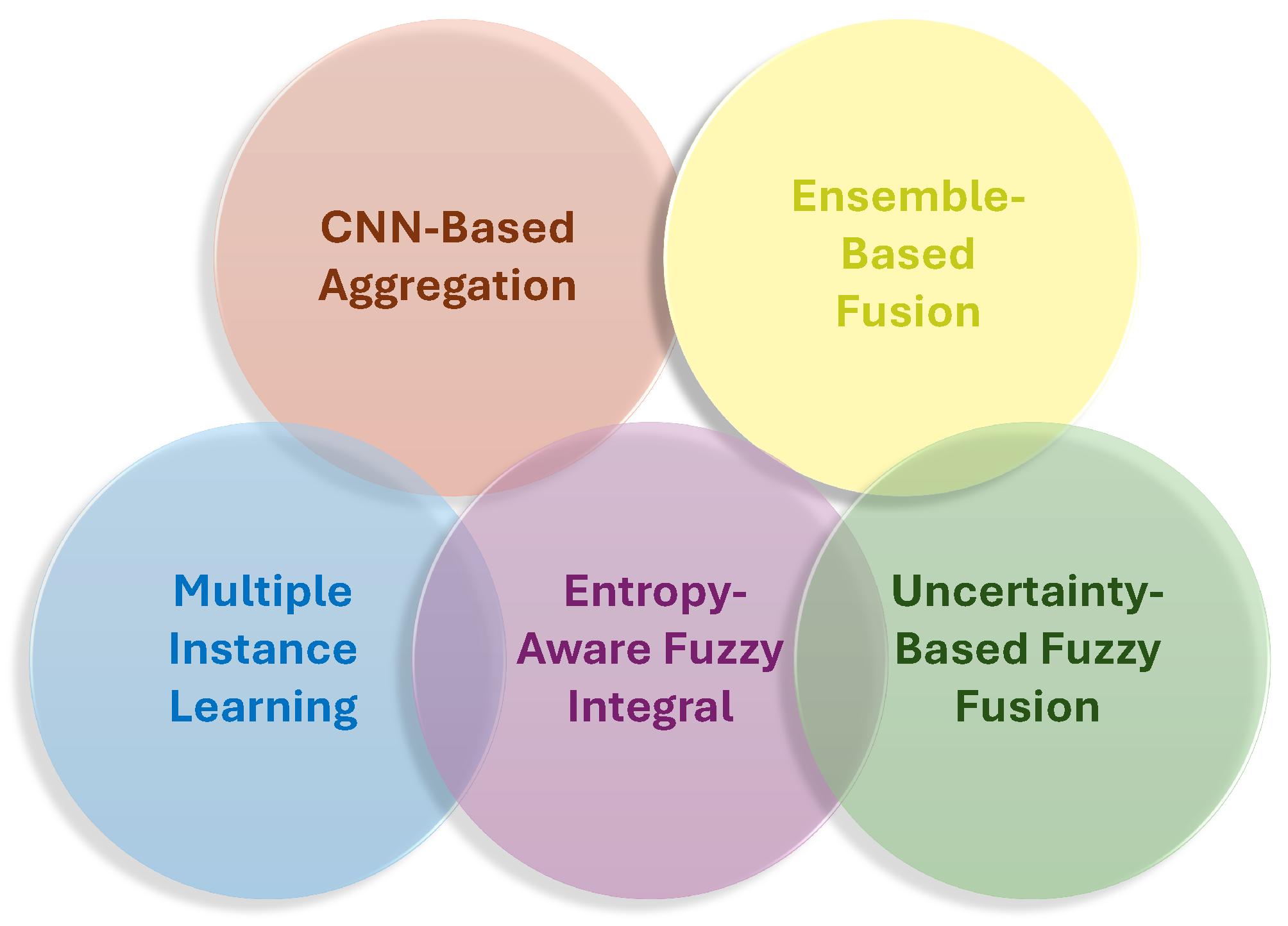

2.6. Scan-Level Image Fusion

- Our Insights: SLIF is crucial for enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of ICH detection from CT scans by integrating information across multiple slices. Techniques such as MIL, cascaded architectures, and ensemble learning strategies help capture inter-slice dependencies and improve model robustness. Advanced methods like entropy-aware fuzzy integral operators further refine scan-level decisions by considering slice importance and uncertainty, leading to more reliable results. These strategies enable models to focus on the most relevant slices, improve classification performance, and enhance diagnostic accuracy, especially when dealing with complex hemorrhage types. Overall, scan-level fusion plays a vital role in improving the precision and generalization of ICH detection models. Figure 9 summarizes various image fusion techniques used in ICH detection models.

2.7. XAI

- Our Insights: The integration of explainability techniques into DL models for ICH detection is essential for ensuring trust and clinical acceptance. Techniques like Grad-CAM, CAM, uncertainty maps, and attention mechanisms provide transparency by visualizing the regions of CT scans that influence model decisions, making it easier for clinicians to understand and validate AI predictions. These methods not only enhance the interpretability of the models but also allow for more informed decision-making, fostering confidence in AI-assisted diagnoses. Furthermore, advanced techniques like fuzzy inference systems and deconvolution offer additional insights into the decision-making process, helping clinicians verify the model’s reasoning. Figure 10 summarizes key explainability techniques commonly used in AI-based ICH detection models. While these methods are typically applied during model interpretation, their effectiveness heavily depends on the quality and precision of labeled training data.

2.8. AI Detection vs. Radiologists Interpretation

- Our Insights: AI models demonstrated significant potential in improving the accuracy and efficiency of ICH detection, often surpassing radiologists in detecting subtle hemorrhages and reducing false-negative rates. Their ability to process scans rapidly provides a clear advantage in high-pressure environments, such as emergency rooms, where quick triage is essential. However, AI models are not without limitations, particularly in handling rare hemorrhage types, artifacts, and small lesions. Their performance heavily relies on the quality of training data, and they still tend to produce false positives in certain cases. While AI can be a valuable decision-support tool, it should complement, not replace, radiologists, who bring critical expertise and adaptability to complex or ambiguous cases. Ultimately, the integration of AI as an assistive tool rather than a standalone solution is likely to enhance diagnostic accuracy and efficiency, reducing errors and improving patient outcomes.

2.9. AI in Clinical Settings

- Our Insights: The integration of AI systems into hospital workflows, particularly in emergency settings, showed significant promise in improving the detection and management of ICH. AI proved to be effective in assisting radiologists by enhancing diagnostic accuracy, reducing errors, and streamlining workflows, such as by flagging potential ICH cases and providing real-time analysis. Its ability to process scans quickly, often within seconds, is crucial for timely decision-making in time-sensitive situations. However, challenges such as data variability, the need for large annotated datasets, and integration complexities with existing hospital systems still pose obstacles to widespread adoption. Despite these challenges, AI complements radiologists’ expertise by reducing workload, accelerating diagnoses, and improving the accuracy of ICH detection, making it a valuable decision-support tool in busy clinical environments.

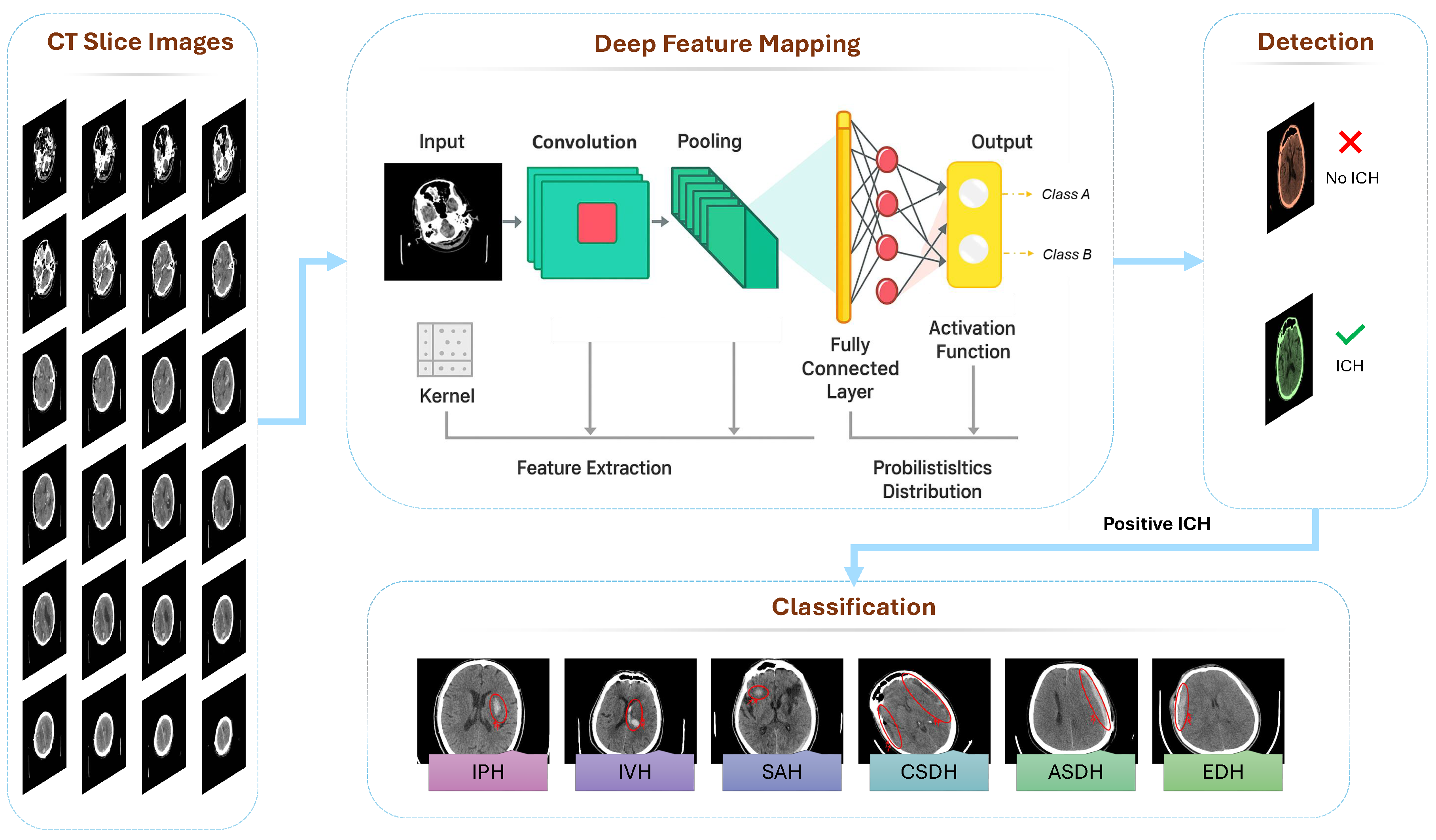

3. Review of Empirical Results in AI Applications for ICH Detection

3.1. ICH Classification Studies

| Research | Sample | Modality | Objective | Deep Learning Model | Validation | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [98] | N/A | CT | 3-Class | CNN + OxfordNet | 70/30 | AUC = 0.894 |

| [99] | 1,940 Slices | MRI | Binary | ResNet18 | 5-Fold |

= 0.91 (Internal), = 0.93 (External) |

| [58] | 613 Slices | MRI | Binary | ResNet34 | 5-Fold | =1.0 |

| [100] | 12635 Scans | CT | Binary | AlexNet-SVM | 70/30 | =0.934 |

| [101] | 42 Scans | MRI | 4-Class | AlexNet + VGG16 + ResNet | 5-Fold | = 0.952 |

| [102] | 372,556 Slices | CT | 5-Class | Double-Branch CNN + Random Forest | 80/10/10 |

: 0.951, = 0.867, = 0.917 |

| [103] | 82 Slices | CT | 5-Class | SVM and FNN | N/A | SVM: =0.806, FNN: =0.867 |

| [86] | 27,749 Scans | CT | 5-Class | DL model | Train/Test |

= 0.913, = 0.941 AUC = 0.954 |

| [97] | 27,713 Slices | CT | 6-Class | SE-ResNeXt50 + XGBoost, CatBoost, LightGBM | 8-Fold |

= 0.913, = 0.941 AUC = 0.954 |

| [104] | 6,565 Scans | CT | 4-Class | Hybrid OzNet | 10-Fold |

=0.938 ,AUC: 0.993 = 0.939 |

| [96] | 750,000 slice | CT | Binary | CNN with Attention | Single-Fold | = 0.839, AUC =0.957 |

| [89] | 200 Slices | CT | Binary | ResNet18 | 80/20 |

= 0.959, = 0.956, = 0.964, = 0.959 |

| [66] | 752,000 Scans | CT | 6-Class | CNN + Attention Network | 5-Fold |

= 0.981, = 0.746, AUC = 0.99 |

| [80] | 945,920 Slices | CT | 6-Class | ResNet34 + Vision Transformer | 5-Fold | AUC = 0.983, = 0.973 |

| [26] | 341 Scans | CT | 5-Class | Faster SqueezeNet & Denoising Autoencoder |

60/40 |

=0.984, =0.948, =0.908, =0.921 |

| [81] | 185,990 Slices | CT | 5-Class | SE-ResNeXT + LSTM | k-Fold | = 0.993 |

| [105] | N/A | CT | 6-Class | Vision Transformer + MLP | Single-Fold | = 0.893 |

| [71] | 573 Scans | NCCT | Binary | Neuro-Fuzzy-Rough Deep Neural Network | 5-Fold | = 0.945 |

| [106] | 2,501 Slices | CT | Binary | Ensemble Learning Model | 90/10 | = 0.865 |

| [107] | 2,600 Scan | CT | Binary | Hybrid Model: DenseNet121 + LSTM | Train/Val/Test |

= 0.959, = 0.975, = 0.970, = 0.963 |

| [65] | 491 Scans | CT | Binary | Attention-Based CNN | K-Fold | AUC = 0.94 |

| [84] | 1,640 Scans | CT | Binary | Attention + Gaussian Processes | 75/25 |

= 0.876, = 0.886, = 0.825 |

| [50] | 917,981 Slices | CT | 6-Class | CNN+ GRU | 5-Fold | AUC = 0.965 |

| [108] | 1,310 Scans | CT | 6-Class | 3D CNN + Bidirectional LSTM | Train/Val/Test |

= 0.982, = 0.989, = 0.987, = 0.984 |

| [109] | 874 Scans | NCCT | 6-Class | EfficientNetV2 + Transformer Encoder | Train/Val/Test |

= 0.976, = 0.983, = 0.975, = 0.976 |

| Research | Sample | Modality | Objective | Deep Learning Model | Validation | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [110] | 46,583 Scans | CT | Binary | Deep CNN | 75/5/20 |

= 0.730, = 0.800 AUC = 0.846 |

| [64] | 21,586 Scans | NCCT | 6-Class | Qure.ai Algorithms | Train/Test | AUC = 0.92 |

| [111] | 1,271 Patients | NCCT | 5-Class | 3D CNN | 5-Fold |

=0.932 ,=0.937, =0.933, =0.987 |

| [112] | 15,979 Slices | NCCT | Binary | 2D CNN & 3D BiLSTM | Train/Test |

: 0.870, = 0.780 = 0.980, AUC = 0.960 |

| [76] | 1,300 Scans | CT | 6-Class | Ensemble Deep Model | Single-Fold | = 0.920, = 0.950 |

| [87] | 110 Patients | CT | Binary | CNN, Aidoc v1.3 | 80/20 |

= 0.950, = 0.990, = 0.980 |

| [113] | 5,650 Patients | CT | 6-Class | Lesion Network | 5-Fold | = 0.883 |

| [114] | 500 Patients | NCCT | Binary | CNN-MLP | N/A |

=0.930, =0.840, =0.940 |

| [115] | 200 Scans | CT | Binary | Hybrid (CNN + LSTM, CNN + GRU) | 5-Fold | = 0.950 |

| [116] | 252 Slices | CT | Binary | Minimalist Machine Learning | N/A | = 0.865, = 0.916 |

| [117] | 200 Slices | CT | 6-Class | ResNet50 | 80/10/10 |

= 0.810, = 0.670, = 0.860 |

| [104] | 3,605 Scans | NCCT | Binary | Aidoc (FDA-Cleared AI DSS) | Train/Test | = 0.923, = 0.977 |

| [94] | 1,113 Scans | NCCT | Binary | Hybrid 2D-3D CNN | 80/20 | = 0.956, = 0.953 |

| [118] | 2,123 Patients | EMR | Binary | XGBoost | 5-Fold |

= 0.740, = 0.749 AUC = 0.800 |

| [93] | 48,070 Patients | NCCT | 6-Class | Joint CNN + RNN with Attention | Train/Test | = 0.994, AUC = 0.998 |

| [119] | 134 Patients | CT | Binary | CNNs + Majority Voting | Single-Fold |

= 0.626, AUC = 0.660 |

| [83] | 341 Scans | CT | 5-Class | Majority Voting-Ensemble of RNN and BiLSTM | 70/30 |

=0.984 ,=0.979, =0.928, =0.987 |

| [120] | 238 Patients | CT | Binary | SVM | 10-Fold | AUC = 0.810 |

| [112] | 1,074,271 Slices | CT | 5-Class | DenseNet | 80/10/10 | = 0.949, = 0.854 |

| [26] | 341 Scans | CT | 5-Class | Faster SqueezeNet + DAE | 70/30 |

= 0.983, = 0.948, = 0.908, = 0.921 |

| [96] | 298 Patients | mNIRS | Binary | DL model | Train/Test |

= 0.948, = 0.941, = 0.942 |

| [91] | 244 Patients | CT | Binary | CNN+ Vision Transformers | 70/30 | AUC = 0.930, = 0.840, = 0.790, = 0.950 |

| [23] | 31,500 Slices | CT | Binary | Convolutional Attention Network | Single-Fold |

=0.984, = 0.980, =0.984, = 0.981 |

| [88] | 36,641 Slices | CT | 5-Class | Fuzzy Fusion Network | Single-Fold |

=0.963, = 0.949, =0.938, = 0.943 |

3.2. ICH Segmentation: State of the Art

3.3. Hybrid and Multi-Task Approaches

| Research | Sample | Modality | Objective | Deep Learning Model | Validation | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [67] | 627 Slices | CT | Seg + Cla | Adaboost-DRLSE + SVM | 5-Class | Seg: = 0.956 Cla: 0.941 |

| [62] | 76,621 Slices | NCCT | Cla + Volume Quantification | ROI-Based CNN | 5-Fold |

= 0.972, = 0.951, = 0.973 |

| [141] | 8,652 Patients | CTA | Seg + Det (Binary) | 3D CNN, SE-ResNeXt | 75/10/15 |

= 0.890, = 0.975, = 0.932 |

| [142] | 135,497 Slices | CT | Cla + Seg (5-Class) | GoogleNet + Dual FCN | 5-Fold | = 0.982 |

| [85] | 135,974 Slices | NCCT | Cla + Seg (5-Class) | Dual CNNs | 5-Fold |

= 0.979, = 0.987, = 0.801, = 0.821 |

| [53] | 4,596 Scans | CT | Seg + Cla (6-Class) | FCN + ResNet38 | 4-Fold | AUC = 0.991 |

| [143] | 2,836 Patients | NCCT | Det + Cla | Joint CNN + RNN | 80/10/10 | = 0.990, = 0.990 |

| [144] | 12,000 Slices | NCCT | Det + Cla | 3D CNN | 5-Fold |

= 0.750, = 0.666, = 0.706 |

| [145] | N/A | CT | Seg + Cla | Capsule Network + Fuzzy DNN | Train/Test | = 0.949, = 0.985 |

| [146] | 82 Patients | CT | Cla + Seg (6-Class) | GrabCut + Synergic Deep Learning | Multi-run |

= 0.957, = 0.957, = 0.940, = 0.977 |

| [147] | 372,556 Slices | CT | Det + Cla | Double-Branch CNN + SVM + RF | 80/10/10 | = 0.954 |

| [61] | 253 | CTA | Seg + Det (Binary) | Ensemble Deep Learning | 5-Fold | = 0.960, DSC = 0.870 |

| [148] | 54 Scans | CT | Det + Seg (Binary) | U-Net | N/A | Fisher = 0.018, MCR= 0.092 |

| [149] | 82 Patients | CT | Cla + Seg (6-Class) | InceptionV4 + MLP | 10-Fold |

= 0.926, = 0.948, = 0.944, = 0.941 |

| [150] | 750 Slices | NCCT | Det + Cla | Mask R-CNN + ResNet50 | 5-Fold | Det: AUC = 0.907, Cla: AUC = 0.956 |

| [57] | 814 Patients | NCCT | Det + Cla | DL Model | Train/Test | = 0.956 |

| [151] | 300 Slices | CT | Det + Seg (Binary) | DeepMedic | K-Fold |

= 0.890, = 0.820, = 0.900 |

| [92] | 2,123 Patients | NCCT | Cla + Seg (5-Class) | Dense-UNet | N/A |

= 0.912, = 0.903, = 0.948 |

| [152] | 30,222 Slices | CT | Det + Cla | Dual-task Vision Transformer | 5-Fold |

= 1.00, = 0.998, = 1.00, = 1.00 |

| [153] | 200 Scan | NCCT | Cla + Seg (Binary) | ResNet50 as Encoder + Two Decoders | Train/Val/Test |

= 0.921, = 0.925, = 0.930, DSC = 0.783 |

4. Future Research Directions

- One of the most pressing needs is the establishment of standardized benchmarks, including widely accepted datasets and evaluation protocols. The current diversity in data sources, performance metrics, and validation strategies makes it difficult to directly compare models or assess generalizability across clinical environments.

- Improving model robustness and generalizability is another critical direction. Many AI models exhibit high accuracy on internal or curated datasets but fail to maintain performance when applied to scans from different institutions or imaging protocols. Approaches such as cross-domain training, external validation, and federated learning offer promising paths toward creating models that are adaptable to diverse real-world settings.

- Advancing scan-level fusion techniques also holds substantial potential. While some studies have introduced methods like MIL and fuzzy integration, the field would benefit from further research into more adaptive and context-aware fusion strategies. These can improve diagnostic accuracy by capturing inter-slice relationships and enhancing the interpretability of scan-level decisions.

- Equally important is the development of efficient and lightweight models suitable for real-time deployment in clinical environments, particularly in resource-constrained settings like emergency rooms or mobile health platforms. Balancing accuracy with computational efficiency will be key to achieving scalable implementation.

- Future work should also explore the integration of multimodal and clinical data to improve the contextual understanding of ICH presentations. Combining CT imaging with electronic health records, lab data, or alternative imaging modalities such as MRI or mNIRS could enhance diagnostic precision, especially in complex or ambiguous cases.

- Explainability remains a major concern in clinical adoption. As DL models become more complex, it is essential to develop transparent systems that clinicians can trust. Techniques such as attention visualization, uncertainty estimation, and rule-based inference systems should be further refined to support clearer decision-making and accountability.

- The high cost and time requirements of manual annotations limit the scalability of current models. Future research should focus on leveraging semi-supervised, weakly supervised, and active learning frameworks to utilize partially labeled or unlabeled data more effectively, thus reducing the dependency on exhaustive expert annotation.

- Finally, to bridge the gap between research and practice, AI models must undergo rigorous real-world validation through prospective, multi-center clinical trials. These trials should assess not only technical performance but also usability, workflow integration, and their actual impact on diagnostic speed, accuracy, and patient outcomes.

5. Conclusions

References

- Huang, H.; Zhu, C.; Qin, H.; Deng, L.; Huang, C.; Saifi, C.; Bondar, K.; Giordan, E.; Danisa, O.; Chung, J.H.; et al. Intracranial hemorrhage after spinal surgery: a literature review. Annals of Translational Medicine 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyol, Ş.; Koçak Gül, D.; Yılmaz, E.; Karaman, Z.F.; Özcan, A.; Küçük, A.; Gök, V.; Aydın, F.; Per, H.; Karakükcü, M.; et al. Intracranial hemorrhage in children with hemophilia. Journal of Translational and Practical Medicine 2022, pp. 85–88.

- Feng, X.; Li, X.; Feng, J.; Xia, J. Intracranial hemorrhage management in the multi-omics era. Heliyon 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y.S.; Sun, X.J.; Liu, Y.Z.; Yin, Y.K.; Hu, B.; Su, M.H.; Li, Q.L.; Mi, Y.C.; et al. Clinical characteristics and prognostic factors in intracranial hemorrhage patients with hematological diseases. Annals of Hematology 2022, 101, 2617–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, L.R. Intracranial haemorrhage in cancer patients. In Handbook of Neuro-Oncology Neuroimaging; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 87–91.

- Ren, Z.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Guo, Z. Conv-SdMLPMixer: A hybrid medical image classification network based on multi-branch CNN and multi-scale multi-dimensional MLP. Information Fusion 2025, p. 102937.

- Renedo, D.; Acosta, J.N.; Leasure, A.C.; Sharma, R.; Krumholz, H.M.; De Havenon, A.; Alahdab, F.; Aravkin, A.Y.; Aryan, Z.; Barnighausen, T.W.; et al. Burden of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke across the US from 1990 to 2019. JAMA neurology 2024, 81, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.R. Cavernous malformations of the central nervous system. New England Journal of Medicine 2024, 390, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethi, A.; Kannath, S.K.; Kumar, A.A.; Mathew, J.; Rajan, J. A comprehensive review and experimental comparison of deep learning methods for automated hemorrhage detection. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2024, 133, 108192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, N.; Biradar, V.G.; Mallya, A.K.S.; Sabat, S.S.; Pareek, P.K.; et al. Identification of Intracranial Hemorrhage using ResNeXt Model. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 2nd Mysore Sub Section International Conference (MysuruCon). IEEE; 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Dehghan Rouzi, M.; Moshiri, B.; Khoshnevisan, M.; Akhaee, M.A.; Jaryani, F.; Salehi Nasab, S.; Lee, M. Breast cancer detection with an ensemble of deep learning networks using a consensus-adaptive weighting method. Journal of Imaging 2023, 9, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.N.; Prakasam, P. A systematic review on intracranial aneurysm and hemorrhage detection using machine learning and deep learning techniques. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bayoudh, K. A survey of multimodal hybrid deep learning for computer vision: Architectures, applications, trends, and challenges. Information Fusion 2024, 105, 102217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yakhkind, A.; Alexandrov, A.W.; Alexandrov, A.V.; Anderson, C.S.; Dowlatshahi, D.; Frontera, J.A.; Hemphill, J.C.; Ganti, L.; Kellner, C.; et al. Code ICH: a call to action. Stroke 2024, 55, 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Shi, X.; Pang, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, X.; Wang, W.; Cai, J.; Song, D.; Li, K. Cross-attention guided loss-based deep dual-branch fusion network for liver tumor classification. Information Fusion 2025, 114, 102713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagahi, M.H.; Dashtaki, S.M.; Moshiri, B.; Piran, M.J. Cardiovascular disease detection using a novel stack-based ensemble classifier with aggregation layer, DOWA operator, and feature transformation. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2024, 173, 108345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chagahi, M.H.; Dashtaki, S.M.; Delfan, N.; Mohammadi, N.; Samari, A.; Moshiri, B.; Piran, M.J.; Acharya, U.R.; Faust, O. Enhancing Osteoporosis Detection: An Explainable Multi-Modal Learning Framework with Feature Fusion and Variable Clustering. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2411.00916 2024.

- Nizarudeen, S.; Shanmughavel, G.R. Comparative analysis of ResNet, ResNet-SE, and attention-based RaNet for hemorrhage classification in CT images using deep learning. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2024, 88, 105672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfan, N.; Moghadam, P.K.; Khoshnevisan, M.; Chagahi, M.H.; Hatami, B.; Asgharzadeh, M.; Zali, M.; Moshiri, B.; Moghaddam, A.M.; Khalafi, M.A.; et al. AI-Driven Non-Invasive Detection and Staging of Steatosis in Fatty Liver Disease Using a Novel Cascade Model and Information Fusion Techniques. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2412.04884 2024.

- Iqbal, S.; Qureshi, A.N.; Aurangzeb, K.; Alhussein, M.; Wang, S.; Anwar, M.S.; Khan, F. Hybrid parallel fuzzy CNN paradigm: Unmasking intricacies for accurate brain MRI insights. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Zhou, T.; Huang, J.; Jiang, S.; Hou, T.; Lin, C.T. FMDNN: A Fuzzy-guided Multi-granular Deep Neural Network for Histopathological Image Classification. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, S.; Liu, D.; Li, C.; Wang, B.; Wang, X. Deep-Learning-Based Microwave-Induced Thermoacoustic Tomography Applying Realistic Properties of Ultrasound Transducer. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagahi, M.H.; Piran, M.J.; Delfan, N.; Moshiri, B.; Parikhan, J.H. AI-Powered Intracranial Hemorrhage Detection: A Co-Scale Convolutional Attention Model with Uncertainty-Based Fuzzy Integral Operator and Feature Screening. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2412.14869 2024.

- Chen, Y.R.; Chen, C.C.; Kuo, C.F.; Lin, C.H. An efficient deep neural network for automatic classification of acute intracranial hemorrhages in brain CT scans. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2024, 176, 108587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, L. Deep multiscale convolutional feature learning for intracranial hemorrhage classification and weakly supervised localization. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, M.; Salama, R.; Alotaibi, F.S.; Abdushkour, H.A.; Alzahrani, I.R. Political optimizer with deep learning based diagnosis for intracranial hemorrhage detection. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 71484–71493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negm, N.; Aldehim, G.; Nafie, F.M.; Marzouk, R.; Assiri, M.; Alsaid, M.I.; Drar, S.; Abdelbagi, S. Intracranial Haemorrhage Diagnosis Using Willow Catkin Optimization With Voting Ensemble Deep Learning on CT Brain Imaging. IEEE Access 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, P.; Vidyarthi, A. A Computational Deep Fuzzy Network-Based Neuroimaging Analysis for Brain Hemorrhage Classification. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudadhe, S.S.; Thakare, A.D.; Oliva, D. Classification of intracranial hemorrhage CT images based on texture analysis using ensemble-based machine learning algorithms: A comparative study. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2023, 84, 104832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Miao, W.; Zhu, C.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Song, R.; Liu, L.; Yang, J. A weakly supervised-guided soft attention network for classification of intracranial hemorrhage. IEEE Transactions on Cognitive and Developmental Systems 2022, 15, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyung, S.; Shin, K.; Jeong, H.; Kim, K.D.; Park, J.; Cho, K.; Lee, J.H.; Hong, G.; Kim, N. Improved performance and robustness of multi-task representation learning with consistency loss between pretexts for intracranial hemorrhage identification in head CT. Medical Image Analysis 2022, 81, 102489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Yune, S.; Mansouri, M.; Kim, M.; Tajmir, S.H.; Guerrier, C.E.; Ebert, S.A.; Pomerantz, S.R.; Romero, J.M.; Kamalian, S.; et al. An explainable deep-learning algorithm for the detection of acute intracranial haemorrhage from small datasets. Nature biomedical engineering 2019, 3, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Macias, F.M.; Morales-Alvarez, P.; Wu, Y.; Molina, R.; Katsaggelos, A.K. Hyperbolic Secant representation of the logistic function: Application to probabilistic Multiple Instance Learning for CT intracranial hemorrhage detection. Artificial Intelligence 2024, 331, 104115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Cano, J.; Wu, Y.; Schmidt, A.; Lopez-Perez, M.; Morales-Alvarez, P.; Molina, R.; Katsaggelos, A.K. An end-to-end approach to combine attention feature extraction and Gaussian Process models for deep multiple instance learning in CT hemorrhage detection. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 240, 122296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, T.; Bucolo, G.M.; Kamareddine, T.; Yel, I.; Koch, V.; Gruenewald, L.D.; Martin, S.; Alizadeh, L.S.; Mazziotti, S.; Blandino, A.; et al. Accuracy and time efficiency of a novel deep learning algorithm for Intracranial Hemorrhage detection in CT Scans. La radiologia medica 2024, pp. 1–8.

- Sindhura, C.; Al Fahim, M.; Yalavarthy, P.K.; Gorthi, S. Fully automated sinogram-based deep learning model for detection and classification of intracranial hemorrhage. Medical Physics 2024, 51, 1944–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.; Vithalapara, K.; Malik, S.; Lavania, A.; Solanki, S.; Adhvaryu, N.S. Human factor engineering of point-of-care near infrared spectroscopy device for intracranial hemorrhage detection in Traumatic Brain Injury: A multi-center comparative study using a hybrid methodology. International Journal of Medical Informatics 2024, 184, 105367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, E.; Yuh, E.L. Semi-supervised learning for generalizable intracranial hemorrhage detection and segmentation. Radiology: Artificial Intelligence 2024, 6, e230077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xi, Z.; Jin, G.; Jiang, W.; Wang, B.; Cai, X.; Wang, X. Deep-learning-enabled microwave-induced thermoacoustic tomography based on ResAttU-Net for transcranial brain hemorrhage detection. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2023, 70, 2350–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smorchkova, A.; Khoruzhaya, A.; Kremneva, E.; Petryaikin, A. Machine learning technologies in CT-based diagnostics and classification of intracranial hemorrhages. Zhurnal voprosy neirokhirurgii imeni NN Burdenko 2023, 87, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, T.J.; Choi, J.W.; Han, M.; Jung, W.S.; Choi, S.H.; Yoo, R.E.; Hwang, I.P. Deep learning based automatic detection algorithm for acute intracranial haemorrhage: a pivotal randomized clinical trial. NPJ Digital Medicine 2023, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsoukas, S.; Scaggiante, J.; Schuldt, B.R.; Smith, C.J.; Chennareddy, S.; Kalagara, R.; Majidi, S.; Bederson, J.B.; Fifi, J.T.; Mocco, J.; et al. Accuracy of artificial intelligence for the detection of intracranial hemorrhage and chronic cerebral microbleeds: A systematic review and pooled analysis. La radiologia medica 2022, 127, 1106–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, M.D.; Antulov, R.; Hess, S.; Lysdahlgaard, S. Convolutional neural network performance compared to radiologists in detecting intracranial hemorrhage from brain computed tomography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Radiology 2022, 146, 110073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Champawat, Y.S.; Prakash, C.; et al. Literature Review for Automatic Detection and Classification of Intracranial Brain Hemorrhage Using Computed Tomography Scans. Robotics, Control and Computer Vision 2023, pp. 39–65.

- Maghami, M.; Sattari, S.A.; Tahmasbi, M.; Panahi, P.; Mozafari, J.; Shirbandi, K. Diagnostic test accuracy of machine learning algorithms for the detection intracranial hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis study. BioMedical Engineering OnLine 2023, 22, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, D.; Poonamallee, L.; Joshi, S. Automated detection of intracranial hemorrhage from head CT scans applying deep learning techniques in traumatic brain injuries: A comparative review. Indian Journal of Neurotrauma 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Yan, T.; Xiao, B.; Shu, H.; Sheng, Y.; Wu, Y.; Shu, L.; Lv, S.; Ye, M.; Gong, Y.; et al. Deep learning-assisted detection and segmentation of intracranial hemorrhage in noncontrast computed tomography scans of acute stroke patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Surgery 2024, 110, 3839–3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Wood, D.; Grzeda, M.; Suresh, C.; Din, M.; Cole, J.; Modat, M.; Booth, T.C. Systematic Review of Artificial Intelligence for Abnormality Detection in High-volume Neuroimaging and Subgroup Meta-analysis for Intracranial Hemorrhage Detection. Clinical Neuroradiology 2023, pp. 1–14.

- Karamian, A.; Seifi, A. Diagnostic Accuracy of Deep Learning for Intracranial Hemorrhage Detection in Non-Contrast Brain CT Scans: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2025, 14, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.R.; Chen, C.C.; Kuo, C.F.; Lin, C.H. An efficient deep neural network for automatic classification of acute intracranial hemorrhages in brain CT scans. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2024, 176, 108587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkeaw, P.; Angkurawaranon, S.; Khumrin, P.; Inmutto, N.; Traisathit, P.; Chaijaruwanich, J.; Angkurawaranon, C.; Chitapanarux, I. Automatic hemorrhage segmentation on head CT scan for traumatic brain injury using 3D deep learning model. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2022, 146, 105530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, Q.T.; Pham, X.H.; Trinh, X.T.; Le, A.V.; Bui, M.V.; Bui, T.T. An efficient CNN-based method for intracranial hemorrhage segmentation from computerized tomography imaging. Journal of Imaging 2024, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, W.; Hane, C.; Mukherjee, P.; Malik, J.; Yuh, E.L. Expert-level detection of acute intracranial hemorrhage on head computed tomography using deep learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 22737–22745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.M.; Chowdhury, M.E.H.; Arefin, A.S.M.S.; Podder, K.K.; Hossain, M.S.A.; Alqahtani, A.; Murugappan, M.; Khandakar, A.; Mushtak, A.; Nahiduzzaman, M. A Deep Learning-Based Automatic Segmentation and 3D Visualization Technique for Intracranial Hemorrhage Detection Using Computed Tomography Images. Diagnostics 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Xi, Z.; Jin, G.; Jiang, W.; Wang, B.; Cai, X.; Wang, X. Deep-Learning-Enabled Microwave-Induced Thermoacoustic Tomography Based on ResAttU-Net for Transcranial Brain Hemorrhage Detection. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2023, 70, 2350–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hssayeni, M.D.; Croock, M.S.; Salman, A.D.; Al-Khafaji, H.F.; Yahya, Z.A.; Ghoraani, B. Intracranial hemorrhage segmentation using a deep convolutional model. Data 2020, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLouth, J.; Elstrott, S.; Chaibi, Y.; Quenet, S.; Chang, P.D.; Chow, D.S.; Soun, J.E. Validation of a deep learning tool in the detection of intracranial hemorrhage and large vessel occlusion. Frontiers in Neurology 2021, 12, 656112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talo, M.; Baloglu, U.B.; Yıldırım, Ö.; Acharya, U.R. Application of deep transfer learning for automated brain abnormality classification using MR images. Cognitive Systems Research 2019, 54, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muschelli, J.; Sweeney, E.M.; Ullman, N.L.; Vespa, P.; Hanley, D.F.; Crainiceanu, C.M. PItcHPERFeCT: primary intracranial hemorrhage probability estimation using random forests on CT. NeuroImage: Clinical 2017, 14, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaltin, O.; Coskun, O.; Yeniay, O.; Subasi, A. Classification of brain hemorrhage computed tomography images using OzNet hybrid algorithm. International Journal of Imaging Systems and Technology 2023, 33, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, R.; Pennig, L.; Goertz, L.; Thiele, F.; Kabbasch, C.; Schlamann, M.; Krischek, B.; Maintz, D.; Perkuhn, M.; Borggrefe, J. Fully automated detection and segmentation of intracranial aneurysms in subarachnoid hemorrhage on CTA using deep learning. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 21799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.D.; Kuoy, E.; Grinband, J.; Weinberg, B.D.; Thompson, M.; Homo, R.; Chen, J.; Abcede, H.; Shafie, M.; Sugrue, L.; et al. Hybrid 3D/2D convolutional neural network for hemorrhage evaluation on head CT. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2018, 39, 1609–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pérez, M.; Schmidt, A.; Wu, Y.; Molina, R.; Katsaggelos, A.K. Deep Gaussian processes for multiple instance learning: Application to CT intracranial hemorrhage detection. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2022, 219, 106783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilamkurthy, S.; Ghosh, R.; Tanamala, S.; Biviji, M.; Campeau, N.G.; Venugopal, V.K.; Mahajan, V.; Rao, P.; Warier, P. Deep learning algorithms for detection of critical findings in head CT scans: a retrospective study. The Lancet 2018, 392, 2388–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Macías, F.M.; Morales-Álvarez, P.; Wu, Y.; Molina, R.; Katsaggelos, A.K. Hyperbolic Secant representation of the logistic function: Application to probabilistic Multiple Instance Learning for CT intracranial hemorrhage detection. Artificial Intelligence 2024, 331, 104115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Miao, W.; Zhu, C.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Song, R.; Liu, L.; Yang, J. A weakly supervised-guided soft attention network for classification of intracranial hemorrhage. IEEE Transactions on Cognitive and Developmental Systems 2022, 15, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahangian, B.; Pourghassem, H. Automatic brain hemorrhage segmentation and classification algorithm based on weighted grayscale histogram feature in a hierarchical classification structure. Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering 2016, 36, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; van de Leemput, S.; Prokop, M.; Ginneken, B.; Manniesing, R. Image Level Training and Prediction: Intracranial Hemorrhage Identification in 3D Non-Contrast CT. IEEE Access 2019, PP, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, E.; Yuh, E.L. Semi-supervised learning for generalizable intracranial hemorrhage detection and segmentation. Radiology: Artificial Intelligence 2024, 6, e230077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emon, S.H.; Tseng, T.L.B.; Pokojovy, M.; Moen, S.; McCaffrey, P.; Walser, E.; Vo, A.; Rahman, M.F. Uncertainty-Guided Semi-Supervised (UGSS) mean teacher framework for brain hemorrhage segmentation and volume quantification. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2025, 102, 107386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, P.; Vidyarthi, A. A computational deep fuzzy network-based neuroimaging analysis for brain hemorrhage classification. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, B.; Zohrabian, V.; Cedeno, P.; Saha, A.; Pahade, J.; Davis, M.A. Utility of artificial intelligence tool as a prospective radiology peer reviewer—Detection of unreported intracranial hemorrhage. Academic radiology 2021, 28, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, S.; Kumar, V.; Ahuja, C.; Khandelwal, N. Intensity population based unsupervised hemorrhage segmentation from brain CT images. Expert Systems with Applications 2018, 97, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdi, A.; Benierbah, S.; Nakib, A.; Ferdi, Y.; Taleb-Ahmed, A. Quadratic Convolution-based YOLOv8 (Q-YOLOv8) for localization of intracranial hemorrhage from head CT images. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2024, 96, 106611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, S.; Damaševičius, R.; Maskeliūnas, R. Hemorrhage Detection Based on 3D CNN Deep Learning Framework and Feature Fusion for Evaluating Retinal Abnormality in Diabetic Patients. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Yune, S.; Mansouri, M.; Kim, M.; Tajmir, S.H.; Guerrier, C.E.; Ebert, S.A.; Pomerantz, S.R.; Romero, J.M.; Kamalian, S.; et al. An explainable deep-learning algorithm for the detection of acute intracranial haemorrhage from small datasets. Nature biomedical engineering 2019, 3, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ker, J.; Singh, S.P.; Bai, Y.; Rao, J.; Lim, T.; Wang, L. Image thresholding improves 3-dimensional convolutional neural network diagnosis of different acute brain hemorrhages on computed tomography scans. Sensors 2019, 19, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, L. Deep multiscale convolutional feature learning for intracranial hemorrhage classification and weakly supervised localization. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Gao, F.; Yin, Y.; Guo, D.; Zhao, P.; Lu, Y.; Wang, X.; Bai, J.; Cao, K.; Song, Q.; et al. Precise diagnosis of intracranial hemorrhage and subtypes using a three-dimensional joint convolutional and recurrent neural network. European radiology 2019, 29, 6191–6201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Xiong, G. Vision transformer-based classification study of intracranial hemorrhage. In Proceedings of the 2022 3rd International Conference on Computer Vision, Image and Deep Learning & International Conference on Computer Engineering and Applications (CVIDL & ICCEA). IEEE; 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Umapathy, S.; Murugappan, M.; Bharathi, D.; Thakur, M. Automated computer-aided detection and classification of intracranial hemorrhage using ensemble deep learning techniques. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapakse, J.C.; How, C.H.; Chan, Y.H.; Hao, L.C.P.; Padhi, A.; Adrakatti, V.; Khan, I.; Lim, T. Two-stage approach to intracranial hemorrhage segmentation from head CT images. IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negm, N.; Aldehim, G.; Nafie, F.M.; Marzouk, R.; Assiri, M.; Alsaid, M.I.; Drar, S.; Abdelbagi, S. Intracranial haemorrhage diagnosis using willow catkin optimization with voting ensemble deep learning on CT brain imaging. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 75474–75483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cano, J.; Wu, Y.; Schmidt, A.; López-Pérez, M.; Morales-Álvarez, P.; Molina, R.; Katsaggelos, A.K. An end-to-end approach to combine attention feature extraction and Gaussian Process models for deep multiple instance learning in CT hemorrhage detection. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 240, 122296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Park, K.S.; Karki, M.; Lee, E.; Ko, S.; Kim, J.K.; Lee, D.; Choe, J.; Son, J.; Kim, M.; et al. Improving sensitivity on identification and delineation of intracranial hemorrhage lesion using cascaded deep learning models. Journal of digital imaging 2019, 32, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehinejad, H.; Kitamura, J.; Ditkofsky, N.; Lin, A.; Bharatha, A.; Suthiphosuwan, S.; Lin, H.M.; Wilson, J.R.; Mamdani, M.; Colak, E. A real-world demonstration of machine learning generalizability in the detection of intracranial hemorrhage on head computerized tomography. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 17051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, T.F.; Lip, G.Y.; Lin, Y.J.; Chang, S.L.; Lo, L.W.; Hu, Y.F.; Tuan, T.C.; Liao, J.N.; Chung, F.P.; Chen, T.J.; et al. Major bleeding and intracranial hemorrhage risk prediction in patients with atrial fibrillation: attention to modifiable bleeding risk factors or use of a bleeding risk stratification score? A nationwide cohort study. International journal of cardiology 2018, 254, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagahi, M.H.; Delfan, N.; Moshiri, B.; Piran, M.J.; Parikhan, J.H. Vision Transformer for Intracranial Hemorrhage Classification in CT Scans Using an Entropy-Aware Fuzzy Integral Strategy for Adaptive Scan-Level Decision Fusion. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2503.08609 2025.

- Altuve, M.; Pérez, A. Intracerebral hemorrhage detection on computed tomography images using a residual neural network. Physica Medica 2022, 99, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.A.; Samarasekera, N.; Lerpiniere, C.; Humphreys, C.; McCarron, M.O.; White, P.M.; Nicoll, J.A.; Sudlow, C.L.; Cordonnier, C.; Wardlaw, J.M.; et al. The Edinburgh CT and genetic diagnostic criteria for lobar intracerebral haemorrhage associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy: model development and diagnostic test accuracy study. The Lancet Neurology 2018, 17, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Lu, C.; Xu, M.; Yang, G.; Chen, W.; Liu, Z. DeepSAP: a novel brain image-based deep learning model for predicting stroke-associated pneumonia from spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Academic Radiology 2024, 31, 5193–5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, T.; Bucolo, G.M.; Kamareddine, T.; Yel, I.; Koch, V.; Gruenewald, L.D.; Martin, S.; Alizadeh, L.S.; Mazziotti, S.; Blandino, A.; et al. Accuracy and time efficiency of a novel deep learning algorithm for Intracranial Hemorrhage detection in CT Scans. La radiologia medica 2024, 129, 1499–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alis, D.; Alis, C.; Yergin, M.; Topel, C.; Asmakutlu, O.; Bagcilar, O.; Senli, Y.D.; Ustundag, A.; Salt, V.; Dogan, S.N.; et al. A joint convolutional-recurrent neural network with an attention mechanism for detecting intracranial hemorrhage on noncontrast head CT. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heit, J.; Coelho, H.; Lima, F.; Granja, M.; Aghaebrahim, A.; Hanel, R.; Kwok, K.; Haerian, H.; Cereda, C.; Venkatasubramanian, C.; et al. Automated cerebral hemorrhage detection using RAPID. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2021, 42, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbabshirani, M.R.; Fornwalt, B.K.; Mongelluzzo, G.J.; Suever, J.D.; Geise, B.D.; Patel, A.A.; Moore, G.J. Advanced machine learning in action: identification of intracranial hemorrhage on computed tomography scans of the head with clinical workflow integration. NPJ digital medicine 2018, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.; Vithalapara, K.; Malik, S.; Lavania, A.; Solanki, S.; Adhvaryu, N.S. Human factor engineering of point-of-care near infrared spectroscopy device for intracranial hemorrhage detection in Traumatic Brain Injury: A multi-center comparative study using a hybrid methodology. International Journal of Medical Informatics 2024, 184, 105367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehinejad, H.; Kitamura, J.; Ditkofsky, N.; Lin, A.; Bharatha, A.; Suthiphosuwan, S.; Lin, H.M.; Wilson, J.R.; Mamdani, M.; Colak, E. A real-world demonstration of machine learning generalizability in the detection of intracranial hemorrhage on head computerized tomography. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 17051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Grinsven, M.J.; van Ginneken, B.; Hoyng, C.B.; Theelen, T.; Sánchez, C.I. Fast convolutional neural network training using selective data sampling: Application to hemorrhage detection in color fundus images. IEEE transactions on medical imaging 2016, 35, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Luo, G.; Wang, W.; Wang, K.; Gao, Y.; Li, S. Hematoma expansion context guided intracranial hemorrhage segmentation and uncertainty estimation. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2021, 26, 1140–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawud, A.M.; Yurtkan, K.; Oztoprak, H. Application of deep learning in neuroradiology: brain haemorrhage classification using transfer learning. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 2019, 2019, 4629859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talo, M.; Yildirim, O.; Baloglu, U.B.; Aydin, G.; Acharya, U.R. Convolutional neural networks for multi-class brain disease detection using MRI images. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics 2019, 78, 101673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sage, A.; Badura, P. Intracranial hemorrhage detection in head CT using double-branch convolutional neural network, support vector machine, and random forest. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 7577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Khan, S.; Kou, B.; Nazir, S.; Liu, W.; Hussain, A. A smart machine learning model for the detection of brain hemorrhage diagnosis based internet of things in smart cities. Complexity 2020, 2020, 3047869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voter, A.F.; Meram, E.; Garrett, J.W.; Yu, J.P.J. Diagnostic accuracy and failure mode analysis of a deep learning algorithm for the detection of intracranial hemorrhage. Journal of the American College of Radiology 2021, 18, 1143–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, H.; Yang, L.; Lan, P. A Nested Vision Transformer in Vision Transformer Framework for Intracranial Hemorrhage. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 6th International Conference on Automation, Electronics and Electrical Engineering (AUTEEE). IEEE; 2023; pp. 480–486. [Google Scholar]

- Gudadhe, S.S.; Thakare, A.D.; Oliva, D. Classification of intracranial hemorrhage CT images based on texture analysis using ensemble-based machine learning algorithms: A comparative study. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2023, 84, 104832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, P.P.S.; Brindha, T. Deep Learning Fusion for Intracranial Hemorrhage Classification in Brain CT Imaging. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science & Applications 2024, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.C.; Chiang, H.F.; Hsieh, C.C.; Zhu, B.R.; Wu, W.J.; Shaw, J.S. Impact of Dataset Size on 3D CNN Performance in Intracranial Hemorrhage Classification. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Luo, Y.; Yang, F.; Zhou, H.; Lin, Z.; Cai, C.; Lin, Y.; Chen, J. ETDformer: an effective transformer block for segmentation of intracranial hemorrhage. Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing 2025, pp. 1–18.

- Arbabshirani, M.R.; Fornwalt, B.K.; Mongelluzzo, G.J.; Suever, J.D.; Geise, B.D.; Patel, A.A.; Moore, G.J. Advanced machine learning in action: identification of intracranial hemorrhage on computed tomography scans of the head with clinical workflow integration. NPJ digital medicine 2018, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Schreuder, F.H.; Klijn, C.J.; Prokop, M.; Ginneken, B.v.; Marquering, H.A.; Roos, Y.B.; Baharoglu, M.I.; Meijer, F.J.; Manniesing, R. Intracerebral haemorrhage segmentation in non-contrast CT. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 17858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arman, S.E.; Rahman, S.S.; Irtisam, N.; Deowan, S.A.; Islam, M.A.; Sakib, S.; Hasan, M. Intracranial hemorrhage classification from ct scan using deep learning and bayesian optimization. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 83446–83460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, M.; Cho, J.; Lee, E.; Hahm, M.H.; Yoon, S.Y.; Kim, M.; Ahn, J.Y.; Son, J.; Park, S.H.; Kim, K.H.; et al. CT window trainable neural network for improving intracranial hemorrhage detection by combining multiple settings. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine 2020, 106, 101850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buls, N.; Watte, N.; Nieboer, K.; Ilsen, B.; de Mey, J. Performance of an artificial intelligence tool with real-time clinical workflow integration–detection of intracranial hemorrhage and pulmonary embolism. Physica Medica 2021, 83, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, M.F.; Shahroz, M.; Aseere, A.M.; Shah, H.; Majeed, R.; Shehzad, D.; Samad, A. BHCNet: neural network-based brain hemorrhage classification using head CT scan. Ieee Access 2021, 9, 113901–113916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solorio-Ramírez, J.L.; Saldana-Perez, M.; Lytras, M.D.; Moreno-Ibarra, M.A.; Yáñez-Márquez, C. Brain hemorrhage classification in CT scan images using minimalist machine learning. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Koo, H.W.; Lee, B.J.; Yoon, S.W.; Sohn, M.J. Cerebral hemorrhage detection and localization with medical imaging for cerebrovascular disease diagnosis and treatment using explainable deep learning. Journal of the Korean Physical Society 2021, 79, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, D.; Inaji, M.; Hase, T.; Takahashi, S.; Sakai, R.; Ayabe, F.; Tanaka, Y.; Otomo, Y.; Maehara, T. A prehospital triage system to detect traumatic intracranial hemorrhage using machine learning algorithms. JAMA Network Open 2022, 5, e2216393–e2216393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmeijer, E.; Tan, C.; Van der Heijden, F.; Gupta, R. Crowd-sourced deep learning for intracranial hemorrhage identification: Wisdom of crowds or laissez-faire. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2023, 44, 762–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, J.; Xu, Z.; Sun, H.; Zhai, F.; Qu, X. Machine learning-based CT radiomics model to discriminate the primary and secondary intracranial hemorrhage. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Li, C.; Wang, J.; Wei, X.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, S. Threshold segmentation algorithm for automatic extraction of cerebral vessels from brain magnetic resonance angiography images. Journal of neuroscience methods 2015, 241, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.; Schreuder, F.H.; Klijn, C.J.; Prokop, M.; Ginneken, B.v.; Marquering, H.A.; Roos, Y.B.; Baharoglu, M.I.; Meijer, F.J.; Manniesing, R. Intracerebral haemorrhage segmentation in non-contrast CT. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 17858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livne, M.; Rieger, J.; Aydin, O.U.; Taha, A.A.; Akay, E.M.; Kossen, T.; Sobesky, J.; Kelleher, J.D.; Hildebrand, K.; Frey, D.; et al. A U-Net deep learning framework for high performance vessel segmentation in patients with cerebrovascular disease. Frontiers in neuroscience 2019, 13, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.L.; Farooq, H.; Zhuang, H.; Ibrahim, A.K. Segmentation of intracranial hemorrhage using semi-supervised multi-task attention-based U-net. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, K.; Wu, G.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, X.; Lv, C.; Wu, S.; Chen, Y.; Xie, G.; Yao, Z. Deep learning shows good reliability for automatic segmentation and volume measurement of brain hemorrhage, intraventricular extension, and peripheral edema. European radiology 2021, 31, 5012–5020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, C.; Gong, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wu, S.; Wu, G.; Deng, Y.; Xia, C.; et al. Deep network for the automatic segmentation and quantification of intracranial hemorrhage on CT. Frontiers in neuroscience 2021, 14, 541817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Macías, F.M.; Morales-Álvarez, P.; Wu, Y.; Molina, R.; Katsaggelos, A.K. Hyperbolic Secant representation of the logistic function: Application to probabilistic Multiple Instance Learning for CT intracranial hemorrhage detection. Artificial Intelligence 2024, 331, 104115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Shi, X.; Xia, Q.; Chen, L.; Chen, D.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, H. DFMA-ICH: a deformable mixed-attention model for intracranial hemorrhage lesion segmentation based on deep supervision. Neural Computing and Applications 2024, 36, 8657–8679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Miao, W.; Zhu, C.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Song, R.; Liu, L.; Yang, J. A weakly supervised-guided soft attention network for classification of intracranial hemorrhage. IEEE Transactions on Cognitive and Developmental Systems 2022, 15, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, W.; Hane, C.; Yuh, E.; Mukherjee, P.; Malik, J. Cost-sensitive active learning for intracranial hemorrhage detection. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2018: 21st International Conference, Granada, Spain, September 16-20 2018, Proceedings, Part III 11. Springer, 2018; pp. 715–723.

- Ginat, D. Implementation of machine learning software on the radiology worklist decreases scan view delay for the detection of intracranial hemorrhage on CT. Brain Sciences 2021, 11, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyung, S.; Shin, K.; Jeong, H.; Kim, K.D.; Park, J.; Cho, K.; Lee, J.H.; Hong, G.; Kim, N. Improved performance and robustness of multi-task representation learning with consistency loss between pretexts for intracranial hemorrhage identification in head CT. Medical Image Analysis 2022, 81, 102489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhura, C.; Al Fahim, M.; Yalavarthy, P.K.; Gorthi, S. Fully automated sinogram-based deep learning model for detection and classification of intracranial hemorrhage. Medical Physics 2024, 51, 1944–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Shah, M.A.; Khattak, H.A.; Mussadiq, S.; Ahmed, E.; Nasr, E.A.; Rauf, H.T. Intracranial hemorrhage detection using parallel deep convolutional models and boosting mechanism. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes-Ferre, L.; Gutierrez-Naranjo, M.A.; Egea-Guerrero, J.J.; Perez-Sanchez, S.; Balcerzyk, M. Deep learning applied to intracranial hemorrhage detection. Journal of Imaging 2023, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewel, S.; Robertas, A.; Bożena, F.; et al. Intracranial hemorrhage detection in 3D computed tomography images using a bi-directional long short-term memory network-based modified genetic algorithm. Journals. Journals, Frontiers in neuroscience 2023, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, T.; Chen, F.; Su, J.; Chen, G.; Gan, M. Knowledge-prompted intracranial hemorrhage segmentation on brain computed tomography. Expert Systems with Applications 2025, p. 126609.

- Nizarudeen, S.; Shanmughavel, G.R. Comparative analysis of ResNet, ResNet-SE, and attention-based RaNet for hemorrhage classification in CT images using deep learning. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2024, 88, 105672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, G.; Allende-Cid, H.; Chabert, S.; Mery, D.; Salas, R. Benchmarking YOLO Models for Intracranial Hemorrhage Detection Using Varied CT Data Sources. IEEE access 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emon, S.H.; Tseng, T.L.B.; Pokojovy, M.; Moen, S.; McCaffrey, P.; Walser, E.; Vo, A.; Rahman, M.F. Uncertainty-Guided Semi-Supervised (UGSS) mean teacher framework for brain hemorrhage segmentation and volume quantification. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2025, 102, 107386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.; Chute, C.; Rajpurkar, P.; Lou, J.; Ball, R.L.; Shpanskaya, K.; Jabarkheel, R.; Kim, L.H.; McKenna, E.; Tseng, J.; et al. Deep learning–assisted diagnosis of cerebral aneurysms using the HeadXNet model. JAMA network open 2019, 2, e195600–e195600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Park, K.S.; Karki, M.; Lee, E.; Ko, S.; Kim, J.K.; Lee, D.; Choe, J.; Son, J.; Kim, M.; et al. Improving sensitivity on identification and delineation of intracranial hemorrhage lesion using cascaded deep learning models. Journal of digital imaging 2019, 32, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Gao, F.; Yin, Y.; Guo, D.; Zhao, P.; Lu, Y.; Wang, X.; Bai, J.; Cao, K.; Song, Q.; et al. Precise diagnosis of intracranial hemorrhage and subtypes using a three-dimensional joint convolutional and recurrent neural network. European radiology 2019, 29, 6191–6201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ker, J.; Singh, S.P.; Bai, Y.; Rao, J.; Lim, T.; Wang, L. Image thresholding improves 3-dimensional convolutional neural network diagnosis of different acute brain hemorrhages on computed tomography scans. Sensors 2019, 19, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, R.F.; Escorcia-Gutierrez, J.; Gamarra, M.; Diaz, V.G.; Gupta, D.; Kumar, S. Artificial intelligence with big data analytics-based brain intracranial hemorrhage e-diagnosis using CT images. Neural Computing and Applications 2023, 35, 16037–16049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anupama, C.; Sivaram, M.; Lydia, E.L.; Gupta, D.; Shankar, K. Synergic deep learning model–based automated detection and classification of brain intracranial hemorrhage images in wearable networks. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing 2022, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sage, A.; Badura, P. Intracranial hemorrhage detection in head CT using double-branch convolutional neural network, support vector machine, and random forest. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 7577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fang, Q.; Jiang, A.; Meng, Q.; Pang, G.; Deng, X. Texture analysis based on U-Net neural network for intracranial hemorrhage identification predicts early enlargement. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2021, 206, 106140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansour, R.F.; Aljehane, N.O. An optimal segmentation with deep learning based inception network model for intracranial hemorrhage diagnosis. Neural Computing and Applications 2021, 33, 13831–13843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chen, K.; Xu, S.; Cho, P.C.; Nan, Y.; Zhou, X.; Lv, C.; Li, C.; Xie, G. Lesion synthesis to improve intracranial hemorrhage detection and classification for CT images. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics 2021, 90, 101929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angkurawaranon, S.; Sanorsieng, N.; Unsrisong, K.; Inkeaw, P.; Sripan, P.; Khumrin, P.; Angkurawaranon, C.; Vaniyapong, T.; Chitapanarux, I. A comparison of performance between a deep learning model with residents for localization and classification of intracranial hemorrhage. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 9975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Fan, X.; Song, C.; Wang, X.; Feng, B.; Li, L.; Lu, G. Dual-task vision transformer for rapid and accurate intracerebral hemorrhage CT image classification. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 28920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramananda, S.H.; Sundaresan, V. Label-efficient sequential model-based weakly supervised intracranial hemorrhage segmentation in low-data non-contrast CT imaging. Medical Physics 2025, 52, 2123–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Acronym | Meaning |

|---|---|

| ICH | Intracranial Hemorrhage |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| IL | Image Labeling |

| HPO | Hyper-Parameter Optimization |

| IP | Image Preprocessing |

| IA | Image Augmentation |

| CR | Complexity Reduction |

| SLIM | Scan-Level Image Fusion |

| AICS | AI in Clinical Settings |

| AIVR | AI Detection VS. Radiologists |

| SAH | Subarachnoid Hemorrhage |

| IVH | Intraventricular Hemorrhage |

| IPH | Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage |

| EDH | Epidural Hemorrhage |

| CSDH | Chronic Subdural Hematoma |

| ASDH | Acute Subdural Hematoma |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| GANs | Generative Adversarial Networks |

| PO | Political Optimizer |

| WCO | Willow Catkin Optimization |

| Research | Scope | Contribution | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL | IP | IA | HPO | SLIF | AIDVR | CR | AICS | XAI | ||

| 2022 [43] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | CNN vs radiologist performance | ||||||

| 2022 [42] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Review of ICH classification approaches; preprocessing overview | ||||||

| 2023 [44] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ICH classification review; preprocessing overview | ||||

| 2023 [46] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Focus on validated AI models; Clinical integration | ||||||

| 2023 [45] | ✓ | ✓ | ML accuracy meta-analysis; ResNet focus | |||||||

| 2023 [12] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ICH/aneurysm review; Imaging and hemodynamics | ||||||

| 2023 [48] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Validated ICH detection review | ||||||

| 2024 [47] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | DL model meta-analysis; segmentation speed vs manual | |||||

| 2025 [49] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | DL performance synthesis; clinical explainability | |||||

| Our Survey | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Full AI pipeline; Scan-Level Image Fusion Analysis; AI vs. Radiologists; XAI; model deployment |

| Research | Dataset | Sample | Modality | Objective | Deep Learning Model | Validation | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [121] | Private | 1,800 Slices | 3D TOF MRA | Binary | Thresholding Model | 90/10 | DSC = 0.7, DSC = 0.84 |

| [59] | Public | 112 Scans | CT | Binary | Random Forest | Single-Fold | DSI = 0.899 |

| [73] | Private | 590 Slices | CT | 6-Class | Unsupervised Thresholding-Based Model | Single-Fold |

= 0.939, = 1.00, = 0.924, DSC = 0.923 |

| [122] | Private | 80 Patients | NCCT | Binary | 3D CNN | 49/21/30 | DSC = 0.910 |

| [123] | Private | 66 Patients | TOF, MPRAGE | Binary | U-Net CNN Model | 62/16/12 | DSC = 0.880 |

| [56] | Public | 82 Patients | CT | Binary | U-Net | 5-Fold | DSC = 0.310, = 0.972, = 0.504 |

| [124] | Private + Public | 25,036 Patients | CT | 6-Class | Attention-Based U-Net | 5-Fold | DSC = 0.670 |

| [125] | Private | 11,000 Slices | NCCT | 3-Class | nnU-Net | 62/19/19 | DSC = 0.806, = 0.873 |

| [126] | Private | 3,747 Scans | CT | 4-Class | Dense U-Net | 80/20 | DSC = 0.866 |

| [99] | Private | 11,000 Slices | CT | 5-Class | SLEX-Net | 72/8/20 | = 0.994 |

| [51] | Private | 13,658 Slices | CT | 3-Class | CNN + FCL | 70/30 | DSC (Slice-Level) = 0.524 DSC (Patient-Level) = 0.376 |

| [127] | Public | 2,814 Slices | CT | 5-Class | DenseNet201-U-Net | 5-Fold | DSC = 0.857, = 0.990 IoU = 0.843 |

| [128] | Private | 2,818 Slices | CT | Binary | DeeplabV3+Res50, SAUNet++, TransUNet | K-Fold | DSC = 0.860, = 0.833, IoU = 0.768, = 0.849 |

| Research | Sample | Modality | Objective | Deep Learning Model | Validation | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [129] | 752,000 Slices | CT | Cla + Seg (6-Class) | Weakly-Supervised Guided Soft Attention Network | K-Fold | = 0.981 |

| [130] | 1,247 Scans | CT | Det + Seg (Binary) | PatchFCN | 75/15/10 | Pixel AP= 0.847, Region AP= 0.920, Stack AP= 0.957 |

| [111] | 51 Scans | CT | Seg + Det (Binary) | 2D U-Net, 3D DenseNet, 3D V-Net | 10-Fold | DSC= 0.910 |

| [131] | 8,723 Slices | CT | Cla + Seg (Binary) | DL Model | Train/Test | = 0.884, = 0.961 |

| [125] | 4,000 Slices | CT | Det + Cla | 3D CNN + VGG19 | 10-Fold |

= 0.982, = 0.975, = 0.978, = 0.999 |

| [132] | 147,652 Slices | CT | Seg + Cla | Transfer Learning + LSTM + Conv3D | Single-Fold | AUC = 0.988, = 0.933, = 0.966, = 0.970, DSC = 0.642 |

| [133] | CT | Det + Cla | CNN-RNN (Cascaded) + U-Net | 70/10/20 |

= 0.955, = 0.931, = 0.971 |

|

| [134] | 372,556 slices | CT | Cla + Det | LGBM | 70/30 |

= 0.977, = 0.965, = 0.974, = 0.947 |

| [135] | 752,799 Slices | NCCT | Det + Cla | EfficientNet + ResNet | 90/5/5 | = 0.927, AUC = 0.970 |

| [136] | 870,301 Slices | CT | Cla + Seg | GA + BiLSTM | 5-Fold |

= 0.994, = 0.998, = 0.994 |

| [137] | 37,872 Slices | CT | Det + Cla | CNN-Based Hybrid Model | Train/Test |

= 0.989, = 0.992, = 0.992, = 0.986 |

| [26] | 110 Patients | CT | Cla + Loc (6-Class) | VGG-16 + Attentional Fusion | 80/20 | AUC = 0.973, AP Score = 0.250 |

| [52] | 2,814 Slices | CT | Cla + Seg (6-Class) | Encoder-Decoder Model | 10-Fold |

= 0.993, = 0.943, = 0.967, IoU = 0.807, = 0.981, = 0.960 |

| [69] | 25,457 Scans | NCCT | Det + Seg (Binary) | PatchFCN + Dilated ResNet38 | Train/Test | AUC = 0.939, DSC = 0.829 |

| [138] | 491 Patients | CT | Cla + Seg (6-Class) | ResNet, ResNet-SE, HRaNet | 80/10/10 | AUC = 0.960, Jaccard = 0.913, = 0.946, Kappa = 0.937 |

| [139] | 9,377 Slices | CT | Cla + Loc (5-Class) | YOLO Family | Train/Test |

= 0.967, = 0.970, = 0.979 |

| [140] | 2,814 Slices | CT | Cla + Seg (Binary) | ResUNet | 5-Fold |

= 0.751, = 0.89, Jaccard = 0.441, DSC = 0.613 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).