Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Prior Reviews on Trustworthy AI

2.2. Branches of Trustworthy AI

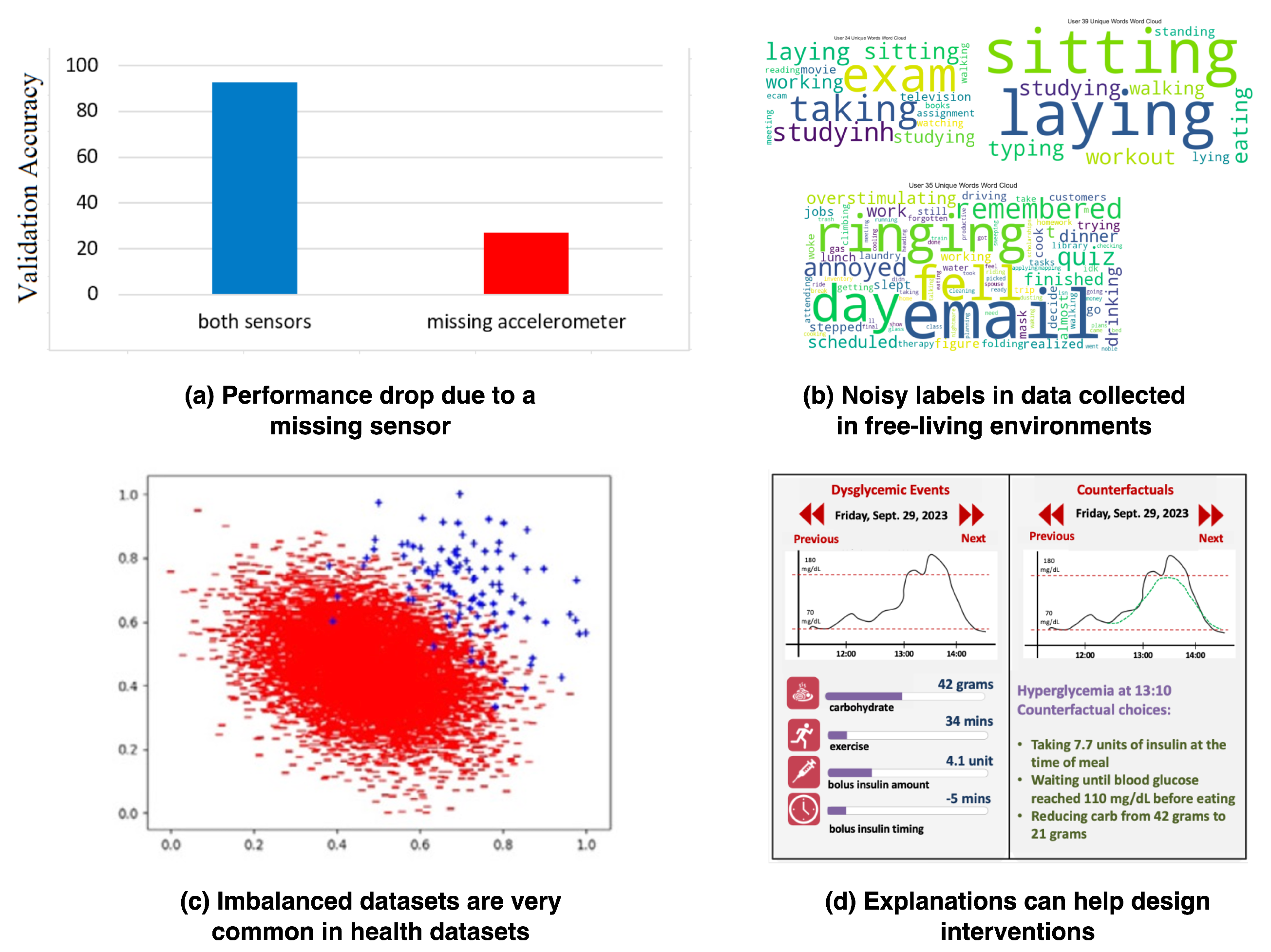

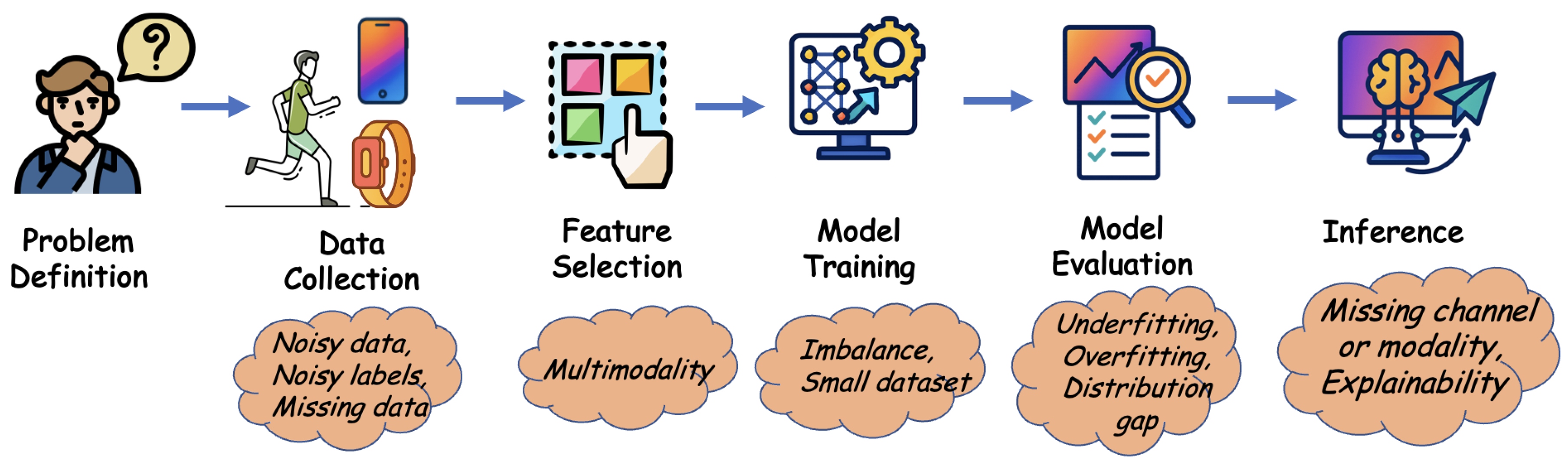

2.3. Challenges in Different Phases of a Machine Learning System

2.4. Designing Robust Machine Learning Models

3. Application-Specific Trust Concerns

3.1. Radiology and Medical Imaging

3.2. Cardiovascular Health

3.3. Metabolic Health

3.4. Neonatal Health and Pediatrics

3.5. Mental Health and Addiction Recovery

3.6. Brain Health

3.7. Intensive Care and Monitoring

3.8. Public Health and Epidemiology

4. Advances in Trustworthy AI for Digital Health

4.1. Label Scarcity and Data-Efficient Learning

4.2. Forecasting and Personalized Interventions

4.3. Self-Supervised Learning and Cross-Domain Generalization

4.4. Robustness and Clinical Utility

4.5. Scientific Discovery and Human Oversight

5. Explainability in Machine Learning

5.1. Explainable AI Methods in ML Models

5.2. Concept and Visual Explanations

5.3. Regularization and Novel Frameworks for Model Robustness

5.4. Counterfactual Explanations in XAI

5.4.1. Benchmarking and Frameworks for Counterfactuals

5.4.2. Applications of Counterfactual Explanations in Healthcare

6. Explainable AI Techniques

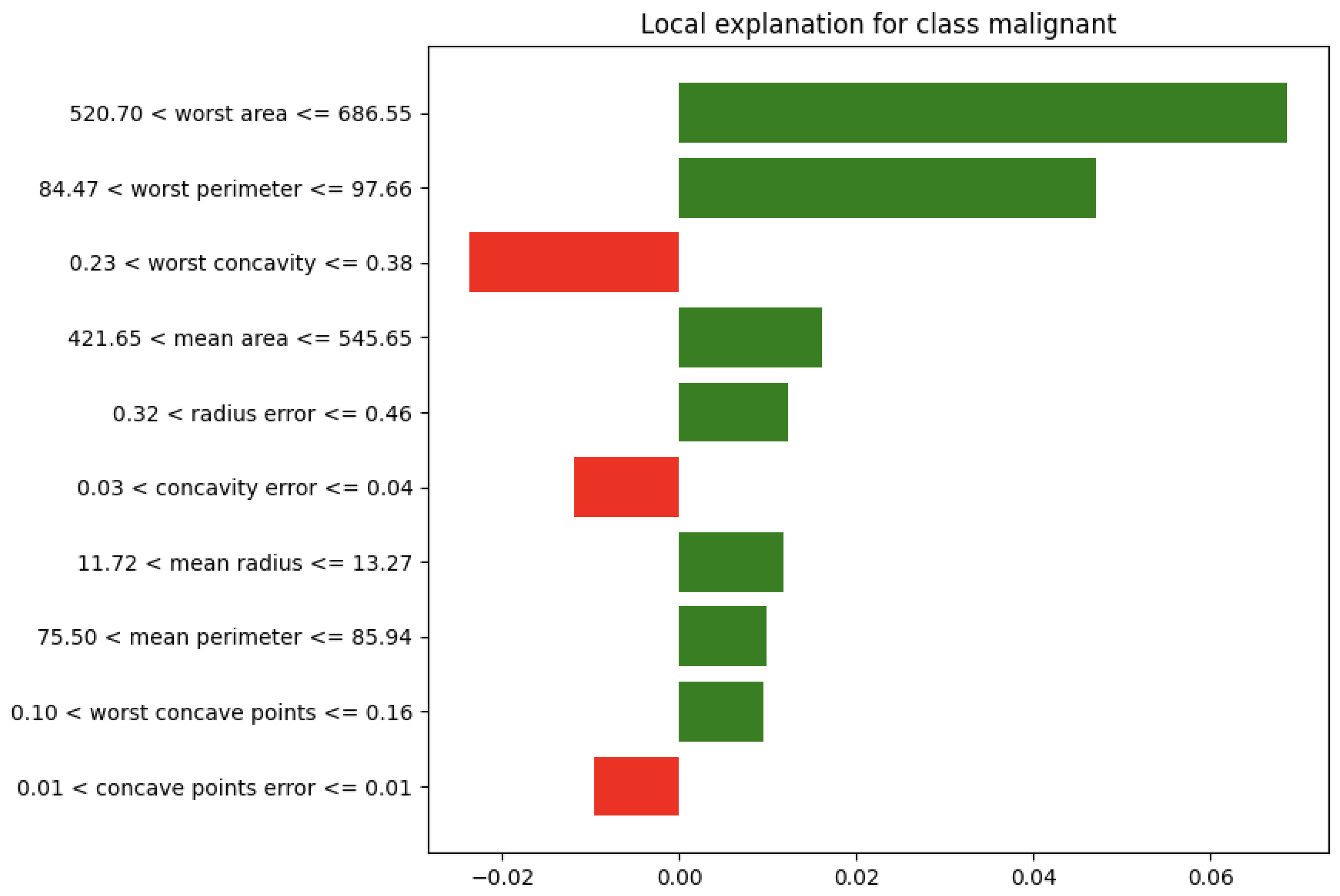

6.1. LIME (Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations)

6.2. Shapley Values

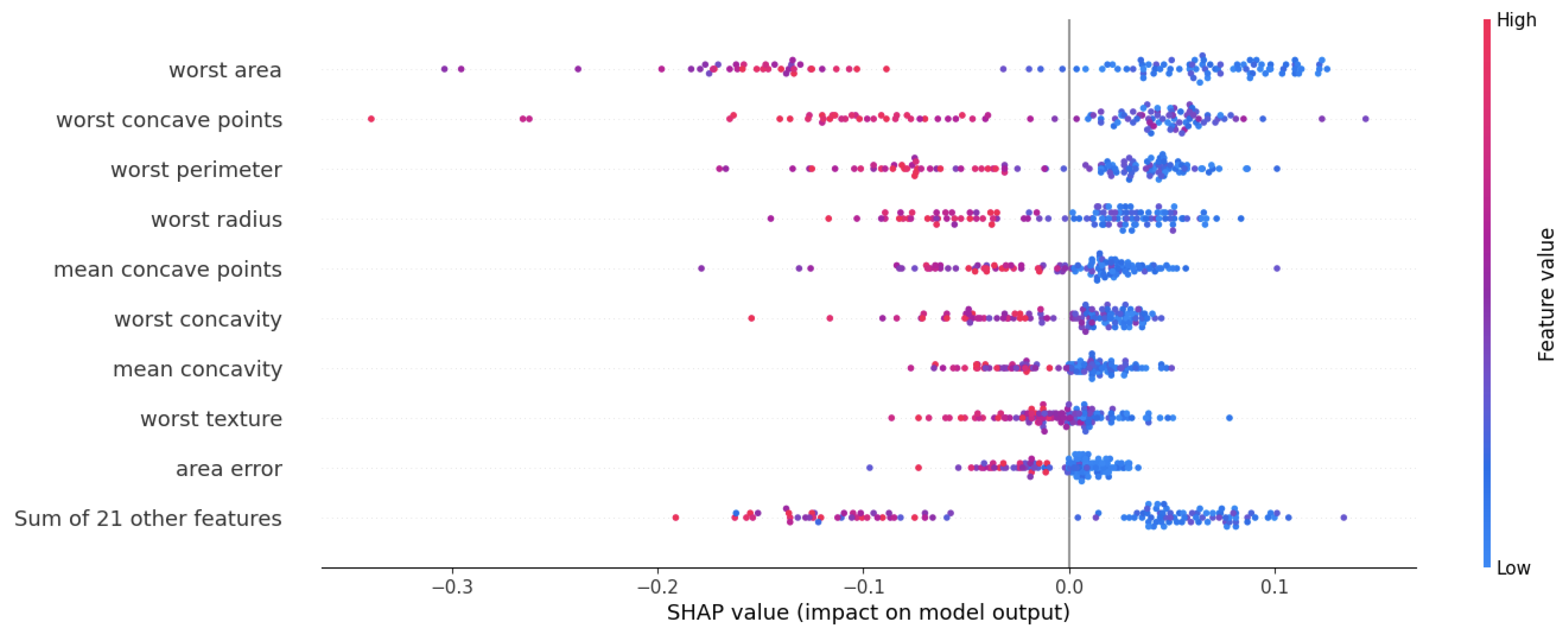

6.3. SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations)

6.4. LRP (Layer-Wise Relevance Propagation)

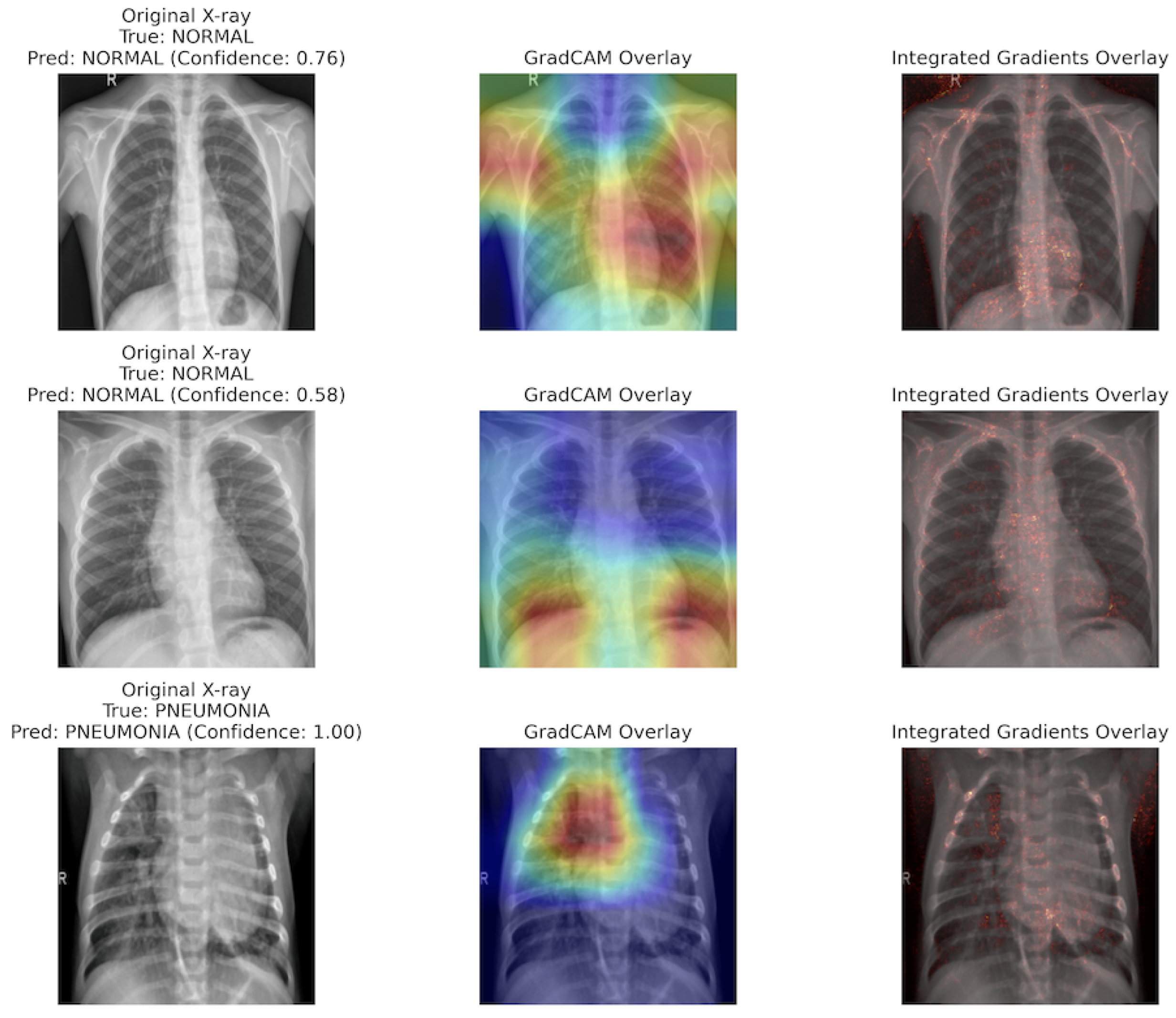

6.5. GradCAM (Gradient-Weighted Class Activation Mapping)

6.6. Integrated Gradients

6.7. NICE (Nearest Instance Counterfactual Explanations)

6.8. DiCE (Diverse Counterfactual Explanations)

6.9. CFNOW

7. Trustworthy AI in the Era of LLMs

8. Evaluation Methods and Metrics of Trustworthy AI

8.1. Evaluation Methods

8.2. Metrics of Evaluation

8.2.1. Trust

8.2.2. Validity

8.2.3. Fidelity

8.2.4. Proximity

8.2.5. Sparsity

8.2.6. Diversity

9. Conclusion

References

- CE Marking trade.gov. https://www.trade.gov/ce-marking. [Accessed July 2025].

- Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI — digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai. [Accessed July 2025].

- oad_breast_cancer — scikit-learn.org. https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.datasets.load_breast_cancer.html. [Accessed July 2025].

- Trustworthy and Responsible AI — nist.gov. https://www.nist.gov/trustworthy-and-responsible-ai. [Accessed July 2025].

- Reduan Achtibat, Maximilian Dreyer, Ilona Eisenbraun, Sebastian Bosse, Thomas Wiegand, Wojciech Samek, and Sebastian Lapuschkin. From attribution maps to human-understandable explanations through concept relevance propagation. Nature Machine Intelligence, 5(9):1006–1019, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Shihab Albahri, Ali M Duhaim, Mohammed A Fadhel, Alhamzah Alnoor, Noor S Baqer, Laith Alzubaidi, Osamah Shihab Albahri, Abdullah Hussein Alamoodi, Jinshuai Bai, Asma Salhi, et al. A systematic review of trustworthy and explainable artificial intelligence in healthcare: Assessment of quality, bias risk, and data fusion. Information Fusion, 96:156–191, 2023.

- Parastoo Alinia, Iman Mirzadeh, and Hassan Ghasemzadeh. Actilabel: A combinatorial transfer learning framework for activity recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.07415, 2020.

- José P Amorim, Pedro H Abreu, João Santos, Marc Cortes, and Victor Vila. Evaluating the faithfulness of saliency maps in explaining deep learning models using realistic perturbations. Information Processing & Management, 60(2):103225, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Yaqoob Ansari, Omar Mourad, Khalid Qaraqe, and Erchin Serpedin. Deep learning for ecg arrhythmia detection and classification: an overview of progress for period 2017–2023. Frontiers in Physiology, 14:1246746, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Asiful Arefeen and Hassan Ghasemzadeh. Designing user-centric behavioral interventions to prevent dysglycemia with novel counterfactual explanations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.01684, 2023.

- Asiful Arefeen, Saman Khamesian, Maria Adela Grando, Bithika Thompson, and Hassan Ghasemzadeh. Glyman: Glycemic management using patient-centric counterfactuals. In 2024 IEEE EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics (BHI), pages 1–5. IEEE, 2024.

- Asiful Arefeen, Saman Khamesian, Maria Adela Grando, Bithika Thompson, and Hassan Ghasemzadeh. Glytwin: Digital twin for glucose control in type 1 diabetes through optimal behavioral modifications using patient-centric counterfactuals. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.09846, 2025.

- Saugat Aryal. Semi-factual explanations in ai. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, volume 38, pages 23379–23380, 2024.

- IIbrahim Berkan Aydilek and Ahmet Arslan. A hybrid method for imputation of missing values using optimized fuzzy c-means with support vector regression and a genetic algorithm. Information Sciences, 233:25–35, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Reza Rahimi Azghan, Nicholas C Glodosky, Ramesh Kumar Sah, Carrie Cuttler, Ryan McLaughlin, Michael J Cleveland, and Hassan Ghasemzadeh. Cudle: Learning under label scarcity to detect cannabis use in uncontrolled environments using wearables. IEEE Sensors Journal, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Mohit Bajaj, Lingyang Chu, Zi Yu Xue, Jian Pei, Lanjun Wang, Peter Cho-Ho Lam, and Yong Zhang. Robust counterfactual explanations on graph neural networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 34:5644–5655, 2021.

- Stephanie Baker and Wei Xiang. Explainable ai is responsible ai: How explainability creates trustworthy and socially responsible artificial intelligence. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.01555, 2023.

- Shahab S Band, Atefeh Yarahmadi, Chung-Chian Hsu, Meghdad Biyari, Mehdi Sookhak, Rasoul Ameri, Iman Dehzangi, Anthony Theodore Chronopoulos, and Huey-Wen Liang. Application of explainable artificial intelligence in medical health: A systematic review of interpretability methods. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked, 40:101286, 2023.

- Oresti Banos, Rafael Garcia, and Alejandro Saez. Mhealth dataset. UCI machine learning repository, 2014.

- Akhiad Bercovich, Itay Levy, Izik Golan, Mohammad Dabbah, Ran El-Yaniv, Omri Puny, Ido Galil, Zach Moshe, Tomer Ronen, Najeeb Nabwani, et al. Llama-nemotron: Efficient reasoning models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.00949, 2025.

- Visar Berisha and Julie M Liss. Responsible development of clinical speech ai: Bridging the gap between clinical research and technology. NPJ Digital Medicine, 7(1):208, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jorge Bernal, Nima Tajkbaksh, Francisco Javier Sanchez, Bogdan J Matuszewski, Hao Chen, Lequan Yu, Quentin Angermann, Olivier Romain, Bjørn Rustad, Ilangko Balasingham, et al. Comparative validation of polyp detection methods in video colonoscopy: results from the miccai 2015 endoscopic vision challenge. IEEE transactions on medical imaging, 36(6):1231–1249, 2017.

- Desirée Bill and Theodor Eriksson. Fine-tuning a llm using reinforcement learning from human feedback for a therapy chatbot application, 2023.

- Alexander Binder, Grégoire Montavon, Sebastian Lapuschkin, Klaus-Robert Müller, and Wojciech Samek. Layer-wise relevance propagation for neural networks with local renormalization layers. In Artificial Neural Networks and Machine Learning–ICANN 2016: 25th International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks, Barcelona, Spain, September 6-9, 2016, Proceedings, Part II 25, pages 63–71. Springer, 2016.

- Ann Borda, Andreea Molnar, Cristina Neesham, and Patty Kostkova. Ethical issues in ai-enabled disease surveillance: perspectives from global health. Applied Sciences, 12(8):3890, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Dieter Brughmans, Pieter Leyman, and David Martens. Nice: an algorithm for nearest instance counterfactual explanations. Data mining and knowledge discovery, 38(5):2665–2703, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Muhammed Kayra Bulut and Banu Diri. Artificial intelligence revolution in turkish health consultancy: Development of llm-based virtual doctor assistants. In 2024 8th International Artificial Intelligence and Data Processing Symposium (IDAP), pages 1–6. IEEE, 2024.

- Oana-Maria Camburu, Tim Rocktäschel, Thomas Lukasiewicz, and Phil Blunsom. e-snli: Natural language inference with natural language explanations. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 31, 2018.

- Aditya Chattopadhay, Anirban Sarkar, Prantik Howlader, and Vineeth N Balasubramanian. Grad-cam++: Generalized gradient-based visual explanations for deep convolutional networks. In 2018 IEEE winter conference on applications of computer vision (WACV), pages 839–847. IEEE, 2018.

- Shreyas Chaudhari, Pranjal Aggarwal, Vishvak Murahari, Tanmay Rajpurohit, Ashwin Kalyan, Karthik Narasimhan, Ameet Deshpande, and Bruno Castro da Silva. Rlhf deciphered: A critical analysis of reinforcement learning from human feedback for llms. ACM Computing Surveys, 2024.

- Nitesh V Chawla, Kevin W Bowyer, Lawrence O Hall, and W Philip Kegelmeyer. Smote: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. Journal of artificial intelligence research, 16:321–357, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Narmatha Chellamani, Saleh Ali Albelwi, Manimurugan Shanmuganathan, Palanisamy Amirthalingam, and Anand Paul. Diabetes: Non-invasive blood glucose monitoring using federated learning with biosensor signals. Biosensors, 15(4):255, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Liang-Chieh Chen, Yukun Zhu, George Papandreou, Florian Schroff, and Hartwig Adam. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), pages 801–818, 2018.

- Yanda Chen, Ruiqi Zhong, Narutatsu Ri, Chen Zhao, He He, Jacob Steinhardt, Zhou Yu, and Kathleen McKeown. Do models explain themselves? counterfactual simulatability of natural language explanations. In Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 7880–7904, 2024.

- Bijoy Chhetri, Lalit Mohan Goyal, and Mamta Mittal. How machine learning is used to study addiction in digital healthcare: A systematic review. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 3(2):100175, 2023.

- Hongjun Choi, Anirudh Som, and Pavan Turaga. Role of orthogonality constraints in improving properties of deep networks for image classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.10762, 2020.

- Minjae Chung, Jong Bum Won, Ganghyun Kim, Yujin Kim, and Utku Ozbulak. Evaluating visual explanations of attention maps for transformer-based medical imaging. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, pages 110–120. Springer, 2024.

- Jan Clusmann, Fiona R Kolbinger, Hannah Sophie Muti, Zunamys I Carrero, Jan-Niklas Eckardt, Narmin Ghaffari Laleh, Chiara Maria Lavinia Löffler, Sophie-Caroline Schwarzkopf, Michaela Unger, Gregory P Veldhuizen, et al. The future landscape of large language models in medicine. Communications medicine, 3(1):141, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Estee Y Cramer, Evan L Ray, Velma K Lopez, Johannes Bracher, Andrea Brennen, Alvaro J Castro Rivadeneira, Aaron Gerding, Tilmann Gneiting, Katie H House, Yuxin Huang, et al. Evaluation of individual and ensemble probabilistic forecasts of covid-19 mortality in the united states. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(15):e2113561119, 2022.

- James L Cross, Michael A Choma, and John A Onofrey. Bias in medical ai: Implications for clinical decision-making. PLOS Digital Health, 3(11):e0000651, 2024.

- Susanne Dandl, Christoph Molnar, Martin Binder, and Bernd Bischl. Multi-objective counterfactual explanations. In International conference on parallel problem solving from nature, pages 448–469. Springer, 2020.

- John Daniels, Pau Herrero, and Pantelis Georgiou. A multitask learning approach to personalized blood glucose prediction. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, 26(1):436–445, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Raphael Mazzine Barbosa de Oliveira, Kenneth Sörensen, and David Martens. A model-agnostic and data-independent tabu search algorithm to generate counterfactuals for tabular, image, and text data. European Journal of Operational Research, 317(2):286–302, 2024.

- Finale Doshi-Velez and Been Kim. Towards a rigorous science of interpretable machine learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1702.08608, 2017.

- Maximilian Dreyer, Reduan Achtibat, Thomas Wiegand, Wojciech Samek, and Sebastian Lapuschkin. Revealing hidden context bias in segmentation and object detection through concept-specific explanations. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pages 3828–3838, 2023.

- Xuefeng Du, Chaowei Xiao, and Sharon Li. Haloscope: Harnessing unlabeled llm generations for hallucination detection. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 37:102948–102972, 2025.

- Abhimanyu Dubey, Abhinav Jauhri, Abhinav Pandey, Abhishek Kadian, Ahmad Al-Dahle, Aiesha Letman, Akhil Mathur, Alan Schelten, Amy Yang, Angela Fan, et al. The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.21783, 2024.

- Ebrahim Farahmand, Reza Rahimi Azghan, Nooshin Taheri Chatrudi, Eric Kim, Gautham Krishna Gudur, Edison Thomaz, Giulia Pedrielli, Pavan Turaga, and Hassan Ghasemzadeh. Attengluco: Multimodal transformer-based blood glucose forecasting on ai-readi dataset. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.09919, 2025.

- Jana Fehr, Brian Citro, Rohit Malpani, Christoph Lippert, and Vince I Madai. A trustworthy ai reality-check: the lack of transparency of artificial intelligence products in healthcare. Frontiers in Digital Health, 6:1267290, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Juraj Gottweis, Wei-Hung Weng, Alexander Daryin, Tao Tu, Anil Palepu, Petar Sirkovic, Artiom Myaskovsky, Felix Weissenberger, Keran Rong, Ryutaro Tanno, et al. Towards an ai co-scientist. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.18864, 2025.

- Chengjian Guan, Angwei Gong, Yan Zhao, Chen Yin, Lu Geng, Linli Liu, Xiuchun Yang, Jingchao Lu, and Bing Xiao. Interpretable machine learning model for new-onset atrial fibrillation prediction in critically ill patients: a multi-center study. Critical Care, 28(1):349, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hao Guan and Mingxia Liu. Domain adaptation for medical image analysis: a survey. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 69(3):1173–1185, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Riccardo Guidotti. Counterfactual explanations and how to find them: literature review and benchmarking. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 38(5):2770–2824, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Daya Guo, Dejian Yang, Haowei Zhang, Junxiao Song, Ruoyu Zhang, Runxin Xu, Qihao Zhu, Shirong Ma, Peiyi Wang, Xiao Bi, et al. Deepseek-r1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in llms via reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.12948, 2025.

- Navid Hasani, Michael A Morris, Arman Rhamim, Ronald M Summers, Elizabeth Jones, Eliot Siegel, and Babak Saboury. Trustworthy artificial intelligence in medical imaging. PET clinics, 17(1):1, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Haibo He, Yang Bai, Edwardo A Garcia, and Shutao Li. Adasyn: Adaptive synthetic sampling approach for imbalanced learning. In 2008 IEEE international joint conference on neural networks (IEEE world congress on computational intelligence), pages 1322–1328. Ieee, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Kaiming He, Xinlei Chen, Saining Xie, Yanghao Li, Piotr Dollár, and Ross Girshick. Masked autoencoders are scalable vision learners. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pages 16000–16009, 2022.

- Tianjia He, Lin Zhang, Fanxin Kong, and Asif Salekin. Exploring inherent sensor redundancy for automotive anomaly detection. In 2020 57th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC), pages 1–6. IEEE, 2020.

- Lei Huang, Weijiang Yu, Weitao Ma, Weihong Zhong, Zhangyin Feng, Haotian Wang, Qianglong Chen, Weihua Peng, Xiaocheng Feng, Bing Qin, et al. A survey on hallucination in large language models: Principles, taxonomy, challenges, and open questions. ACM Transactions on Information Systems, 43(2):1–55, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Shih-Cheng Huang, Anuj Pareek, Malte Jensen, Matthew P Lungren, Serena Yeung, and Akshay S Chaudhari. Self-supervised learning for medical image classification: a systematic review and implementation guidelines. NPJ Digital Medicine, 6(1):74, 2023.

- Dina Hussein, Taha Belkhouja, Ganapati Bhat, and Janardhan Rao Doppa. Energy-efficient missing data recovery in wearable devices: A novel search-based approach. In 2023 IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Low Power Electronics and Design (ISLPED), pages 1–6. IEEE, 2023.

- Dina Hussein and Ganapati Bhat. Cim: A novel clustering-based energy-efficient data imputation method for human activity recognition. ACM Transactions on Embedded Computing Systems, 22(5s):1–26, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Aaron Jaech, Adam Kalai, Adam Lerer, Adam Richardson, Ahmed El-Kishky, Aiden Low, Alec Helyar, Aleksander Madry, Alex Beutel, Alex Carney, et al. Openai o1 system card. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.16720, 2024.

- Davinder Kaur, Suleyman Uslu, and Arjan Durresi. Requirements for trustworthy artificial intelligence–a review. In Advances in Networked-Based Information Systems: The 23rd International Conference on Network-Based Information Systems (NBiS-2020) 23, pages 105–115. Springer, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Davinder Kaur, Suleyman Uslu, Kaley J Rittichier, and Arjan Durresi. Trustworthy artificial intelligence: a review. ACM computing surveys (CSUR), 55(2):1–38, 2022.

- Daniel S Kermany, Michael Goldbaum, Wenjia Cai, Carolina CS Valentim, Huiying Liang, Sally L Baxter, Alex McKeown, Ge Yang, Xiaokang Wu, Fangbing Yan, et al. Identifying medical diagnoses and treatable diseases by image-based deep learning. cell, 172(5):1122–1131, 2018.

- Abby C King, Zakaria N Doueiri, Ankita Kaulberg, and Lisa Goldman Rosas. The promise and perils of artificial intelligence in advancing participatory science and health equity in public health. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 11(1):e65699, 2025.

- Takeshi Kojima, Shixiang Shane Gu, Machel Reid, Yutaka Matsuo, and Yusuke Iwasawa. Large language models are zero-shot reasoners. Advances in neural information processing systems, 35:22199–22213, 2022.

- Dominik Kowald, Sebastian Scher, Viktoria Pammer-Schindler, Peter Müllner, Kerstin Waxnegger, Lea Demelius, Angela Fessl, Maximilian Toller, Inti Gabriel Mendoza Estrada, Ilija Šimić, et al. Establishing and evaluating trustworthy ai: overview and research challenges. Frontiers in Big Data, 7:1467222, 2024.

- Rayan Krishnan, Pranav Rajpurkar, and Eric J Topol. Self-supervised learning in medicine and healthcare. Nature Biomedical Engineering, 6(12):1346–1352, 2022.

- Abhishek Kumar, Tristan Braud, Sasu Tarkoma, and Pan Hui. Trustworthy ai in the age of pervasive computing and big data. In 2020 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Workshops (PerCom Workshops), pages 1–6. IEEE, 2020.

- Wojciech Kusa, Edoardo Mosca, and Aldo Lipani. “dr llm, what do i have?”: The impact of user beliefs and prompt formulation on health diagnoses. In Proceedings of the Third Workshop on NLP for Medical Conversations, pages 13–19, 2023.

- Patrick Lewis, Ethan Perez, Aleksandra Piktus, Fabio Petroni, Vladimir Karpukhin, Naman Goyal, Heinrich Küttler, Mike Lewis, Wen-tau Yih, Tim Rocktäschel, et al. Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive nlp tasks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33:9459–9474, 2020.

- Bo Li, Peng Qi, Bo Liu, Shuai Di, Jingen Liu, Jiquan Pei, Jinfeng Yi, and Bowen Zhou. Trustworthy ai: From principles to practices. ACM Computing Surveys, 55(9):1–46, 2023.

- Chuyi Li, Lulu Li, Hongliang Jiang, Kaiheng Weng, Yifei Geng, Liang Li, Zaidan Ke, Qingyuan Li, Meng Cheng, Weiqiang Nie, et al. Yolov6: A single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.02976, 2022.

- Qian Li, Xi Yang, Jie Xu, Yi Guo, Xing He, Hui Hu, Tianchen Lyu, David Marra, Amber Miller, Glenn Smith, et al. Early prediction of alzheimer’s disease and related dementias using real-world electronic health records. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 19(8):3506–3518, 2023.

- Zhiming Li, Yushi Cao, Xiufeng Xu, Junzhe Jiang, Xu Liu, Yon Shin Teo, Shang-Wei Lin, and Yang Liu. Llms for relational reasoning: How far are we? In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Large Language Models for Code, pages 119–126, 2024.

- Zhenwen Liang, Ye Liu, Tong Niu, Xiangliang Zhang, Yingbo Zhou, and Semih Yavuz. Improving llm reasoning through scaling inference computation with collaborative verification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.05318, 2024.

- Yang Liu, Yuanshun Yao, Jean-Francois Ton, Xiaoying Zhang, Ruocheng Guo, Hao Cheng, Yegor Klochkov, Muhammad Faaiz Taufiq, and Hang Li. Trustworthy llms: a survey and guideline for evaluating large language models’ alignment. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.05374, 2023.

- Scott Lundberg and Su-in Lee. Shap: A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Advances in neural information processing systems, pages 1–10, 2017.

- Mohammad Malekzadeh, Richard G. Clegg, Andrea Cavallaro, and Hamed Haddadi. Protecting sensory data against sensitive inferences. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Privacy by Design in Distributed Systems, W-P2DS’18, pages 2:1–2:6, New York, NY, USA, 2018. ACM.

- Mohammad Malekzadeh, Richard G. Clegg, Andrea Cavallaro, and Hamed Haddadi. Mobile sensor data anonymization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Internet of Things Design and Implementation, IoTDI ’19, pages 49–58, New York, NY, USA, 2019. ACM.

- Abdullah Mamun, Asiful Arefeen, Susan B. Racette, Dorothy D. Sears, Corrie M. Whisner, Matthew P. Buman, and Hassan Ghasemzadeh. Llm-powered prediction of hyperglycemia and discovery of behavioral treatment pathways from wearables and diet, 2025.

- Abdullah Mamun, Diane J Cook, and Hassan Ghasemzadeh. Aimi: Leveraging future knowledge and personalization in sparse event forecasting for treatment adherence. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.16091, 2025.

- Abdullah Mamun, Lawrence D Devoe, Mark I Evans, David W Britt, Judith Klein-Seetharaman, and Hassan Ghasemzadeh. Use of what-if scenarios to help explain artificial intelligence models for neonatal health. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.09635, 2024.

- Abdullah Mamun, Chia-Cheng Kuo, David W Britt, Lawrence D Devoe, Mark I Evans, Hassan Ghasemzadeh, and Judith Klein-Seetharaman. Neonatal risk modeling and prediction. In 2023 IEEE 19th International Conference on Body Sensor Networks (BSN), pages 1–4. IEEE, 2023.

- Abdullah Mamun, Krista S Leonard, Matthew P Buman, and Hassan Ghasemzadeh. Multimodal time-series activity forecasting for adaptive lifestyle intervention design. In 2022 IEEE-EMBS International Conference on Wearable and Implantable Body Sensor Networks (BSN), pages 1–4. IEEE, 2022.

- Abdullah Mamun, Krista S Leonard, Megan E Petrov, Matthew P Buman, and Hassan Ghasemzadeh. Multimodal physical activity forecasting in free-living clinical settings: Hunting opportunities for just-in-time interventions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.09643, 2024.

- Abdullah Mamun, Seyed Iman Mirzadeh, and Hassan Ghasemzadeh. Designing deep neural networks robust to sensor failure in mobile health environments. In 2022 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), pages 2442–2446. IEEE, 2022.

- Elliot Mbunge, Benhildah Muchemwa, Sipho’esihle Jiyane, and John Batani. Sensors and healthcare 5.0: transformative shift in virtual care through emerging digital health technologies. global health journal, 5(4):169–177, 2021.

- Miquel Miró-Nicolau, Antoni Jaume-i Capó, and Gabriel Moyà-Alcover. A comprehensive study on fidelity metrics for xai. Information Processing & Management, 62(1):103900, 2025.

- Seyed Iman Mirzadeh, Jessica Ardo, Ramin Fallahzadeh, Bryan Minor, Lorraine Evangelista, Diane Cook, and Hassan Ghasemzadeh. Labelmerger: Learning activities in uncontrolled environments. In 2019 First International Conference on Transdisciplinary AI (TransAI), pages 64–67. IEEE, 2019.

- Sina Mohseni, Niloofar Zarei, and Eric D Ragan. A multidisciplinary survey and framework for design and evaluation of explainable ai systems. ACM Transactions on Interactive Intelligent Systems (TiiS), 11(3-4):1–45, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Christoph Molnar. Interpretable machine learning. Lulu. com, 2020.

- Michael Moor, Nicolas Bennett, Drago Plečko, Max Horn, Bastian Rieck, Nicolai Meinshausen, Peter Bühlmann, and Karsten Borgwardt. Predicting sepsis using deep learning across international sites: a retrospective development and validation study. EClinicalMedicine, 62, 2023. [CrossRef]

- George Moschonis, George Siopis, Jenny Jung, Evette Eweka, Ruben Willems, Dominika Kwasnicka, Bernard Yeboah-Asiamah Asare, Vimarsha Kodithuwakku, Nick Verhaeghe, Rajesh Vedanthan, et al. Effectiveness, reach, uptake, and feasibility of digital health interventions for adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. The Lancet Digital Health, 5(3):e125–e143, 2023.

- Sayyed Mostafa Mostafavi, Shovito Barua Soumma, Daniel Peterson, Shyamal H Mehta, and Hassan Ghasemzadeh. Detection and severity assessment of parkinson’s disease through analyzing wearable sensor data using gramian angular fields and deep convolutional neural networks. Sensors, 25(11):3421, 2025.

- Ramaravind K Mothilal, Amit Sharma, and Chenhao Tan. Explaining machine learning classifiers through diverse counterfactual explanations. In Proceedings of the 2020 conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency, pages 607–617, 2020.

- Utkarsh Nath, Yancheng Wang, Pavan Turaga, and Yingzhen Yang. Rnas-cl: Robust neural architecture search by cross-layer knowledge distillation. International Journal of Computer Vision, 132(12):5698–5717, 2024.

- Jiquan Ngiam, Aditya Khosla, Mingyu Kim, Juhan Nam, Honglak Lee, Andrew Y Ng, et al. Multimodal deep learning. In ICML, volume 11, pages 689–696, 2011.

- Maxwell Nye, Anders Johan Andreassen, Guy Gur-Ari, Henryk Michalewski, Jacob Austin, David Bieber, David Dohan, Aitor Lewkowycz, Maarten Bosma, David Luan, et al. Show your work: Scratchpads for intermediate computation with language models. 2021.

- Jaya Ojha, Oriana Presacan, Pedro G. Lind, Eric Monteiro, and Anis Yazidi. Navigating uncertainty: A user-perspective survey of trustworthiness of ai in healthcare. ACM Transactions on Computing for Healthcare, 6(3):1–32, 2025.

- David B Olawade, Ojima J Wada, Aanuoluwapo Clement David-Olawade, Edward Kunonga, Olawale Abaire, and Jonathan Ling. Using artificial intelligence to improve public health: a narrative review. Frontiers in Public Health, 11:1196397, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Cheng Ouyang, Carlo Biffi, Chen Chen, Turkay Kart, Huaqi Qiu, and Daniel Rueckert. Self-supervised learning for few-shot medical image segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 41(7):1837–1848, 2022.

- Dong Huk Park, Lisa Anne Hendricks, Zeynep Akata, Anna Rohrbach, Bernt Schiele, Trevor Darrell, and Marcus Rohrbach. Multimodal explanations: Justifying decisions and pointing to the evidence. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pages 8779–8788, 2018.

- Ninlapa Pruksanusak, Natthicha Chainarong, Siriwan Boripan, and Alan Geater. Comparison of the predictive ability for perinatal acidemia in neonates between the nichd 3-tier fhr system combined with clinical risk factors and the fetal reserve index. Plos one, 17(10):e0276451, 2022.

- Xinyuan Qi, Kai Hou, Tong Liu, Zhongzhong Yu, Sihao Hu, and Wenwu Ou. From known to unknown: Knowledge-guided transformer for time-series sales forecasting in alibaba. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.08381, 2021.

- Abhinav Rastogi, Albert Q Jiang, Andy Lo, Gabrielle Berrada, Guillaume Lample, Jason Rute, Joep Barmentlo, Karmesh Yadav, Kartik Khandelwal, Khyathi Raghavi Chandu, et al. Magistral. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.10910, 2025.

- Xiaoyu Ren, Yuanchen Bai, Huiyu Duan, Lei Fan, Erkang Fei, Geer Wu, Pradeep Ray, Menghan Hu, Chenyuan Yan, and Guangtao Zhai. Chatasd: Llm-based ai therapist for asd. In International Forum on Digital TV and Wireless Multimedia Communications, pages 312–324. Springer, 2023.

- Marco Tulio Ribeiro, Sameer Singh, and Carlos Guestrin. " why should i trust you?" explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, pages 1135–1144, 2016.

- Ramesh Kumar Sah, Michael J Cleveland, and Hassan Ghasemzadeh. Stress monitoring in free-living environments. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, 2023.

- Deepti Saraswat, Pronaya Bhattacharya, Ashwin Verma, Vivek Kumar Prasad, Sudeep Tanwar, Gulshan Sharma, Pitshou N Bokoro, and Ravi Sharma. Explainable ai for healthcare 5.0: opportunities and challenges. IEEE Access, 10:84486–84517, 2022.

- Philipp Schmidt and Felix Biessmann. Quantifying interpretability and trust in machine learning systems. 2019.

- Ivan W Selesnick and C Sidney Burrus. Generalized digital butterworth filter design. IEEE Transactions on signal processing, 46(6):1688–1694, 2002.

- Ramprasaath R Selvaraju, Michael Cogswell, Abhishek Das, Ramakrishna Vedantam, Devi Parikh, and Dhruv Batra. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, pages 618–626, 2017.

- Sanyam Paresh Shah, Abdullah Mamun, Shovito Barua Soumma, and Hassan Ghasemzadeh. Enhancing metabolic syndrome prediction with hybrid data balancing and counterfactuals. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.06987, 2025.

- Lloyd S, Shapley; et al. A value for n-person games. 1953.

- Sherif A Shazly, Bijan J Borah, Che G Ngufor, Vanessa E Torbenson, Regan N Theiler, and Abimbola O Famuyide. Impact of labor characteristics on maternal and neonatal outcomes of labor: a machine-learning model. Plos one, 17(8):e0273178, 2022.

- Karen Simonyan, Andrea Vedaldi, and Andrew Zisserman. Deep inside convolutional networks: Visualising image classification models and saliency maps. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.6034, 2013.

- Chandan Singh, Aliyah R Hsu, Richard Antonello, Shailee Jain, Alexander G Huth, Bin Yu, and Jianfeng Gao. Explaining black box text modules in natural language with language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.09863, 2023.

- Bryan A Sisk, Alison L Antes, Sunny C Lin, Paige Nong, and James M DuBois. Validating a novel measure for assessing patient openness and concerns about using artificial intelligence in healthcare. Learning Health Systems, 9(1):e10429, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Shovito Barua Soumma, SM Alam, Rudmila Rahman, Umme Niraj Mahi, Abdullah Mamun, Sayyed Mostafa Mostafavi, and Hassan Ghasemzadeh. Freezing of gait detection using gramian angular fields and federated learning from wearable sensors. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.11764, 2024.

- Shovito Barua Soumma, Abdullah Mamun, and Hassan Ghasemzadeh. Domain-informed label fusion surpasses llms in free-living activity classification (student abstract). In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, volume 39, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Nitish Srivastava, Geoffrey Hinton, Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever, and Ruslan Salakhutdinov. Dropout: a simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. The journal of machine learning research, 15(1):1929–1958, 2014.

- Charithea Stylianides, Andria Nicolaou, Waqar Aziz Sulaiman, Christina-Athanasia Alexandropoulou, Ilias Panagiotopoulos, Konstantina Karathanasopoulou, George Dimitrakopoulos, Styliani Kleanthous, Eleni Politi, Dimitris Ntalaperas, et al. Ai advances in icu with an emphasis on sepsis prediction: An overview. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction, 7(1):6, 2025.

- Mukund Sundararajan, Ankur Taly, and Qiqi Yan. Axiomatic attribution for deep networks. In International conference on machine learning, pages 3319–3328. PMLR, 2017.

- Jayaraman J Thiagarajan, Kowshik Thopalli, Deepta Rajan, and Pavan Turaga. Training calibration-based counterfactual explainers for deep learning models in medical image analysis. Scientific reports, 12(1):597, 2022. [CrossRef]

- George Vavoulas, Charikleia Chatzaki, Thodoris Malliotakis, Matthew Pediaditis, and Manolis Tsiknakis. The mobiact dataset: Recognition of activities of daily living using smartphones. In International conference on information and communication technologies for ageing well and e-health, volume 2, pages 143–151. SciTePress, 2016.

- Sahil Verma, John Dickerson, and Keegan Hines. Counterfactual explanations for machine learning: A review. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.10596, 2(1):1, 2020.

- Pascal Vincent, Hugo Larochelle, Yoshua Bengio, and Pierre-Antoine Manzagol. Extracting and composing robust features with denoising autoencoders. In Proceedings of the 25th international conference on Machine learning, pages 1096–1103, 2008.

- Guotai Wang, Wenqi Li, Michael Aertsen, Jan Deprest, Sébastien Ourselin, and Tom Vercauteren. Aleatoric uncertainty estimation with test-time augmentation for medical image segmentation with convolutional neural networks. Neurocomputing, 338:34–45, 2019.

- Jessica L Watterson, Hector P Rodriguez, Stephen M Shortell, and Adrian Aguilera. Improved diabetes care management through a text-message intervention for low-income patients: mixed-methods pilot study. JMIR diabetes, 3(4):e8645, 2018.

- Jason Wei, Xuezhi Wang, Dale Schuurmans, Maarten Bosma, Fei Xia, Ed Chi, Quoc V Le, Denny Zhou, et al. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems, 35:24824–24837, 2022.

- William Wolberg, Olvi Mangasarian, Nick Street, and W. Street. Breast Cancer Wisconsin (Diagnostic). UCI Machine Learning Repository, 1993. [CrossRef]

- Chengyan Wu, Zehong Lin, Wenlong Fang, and Yuyan Huang. A medical diagnostic assistant based on llm. In China Health Information Processing Conference, pages 135–147. Springer, 2023.

- Xiaolong Wu, Lin Ma, Penghu Wei, Yongzhi Shan, Piu Chan, Kailiang Wang, and Guoguang Zhao. Wearable sensor devices can automatically identify the on-off status of patients with parkinson’s disease through an interpretable machine learning model. Frontiers in Neurology, 15:1387477, 2024.

- Chejian Xu, Jiawei Zhang, Zhaorun Chen, Chulin Xie, Mintong Kang, Yujin Potter, Zhun Wang, Zhuowen Yuan, Alexander Xiong, Zidi Xiong, et al. Mmdt: Decoding the trustworthiness and safety of multimodal foundation models. In The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Lei Xu, Maria Skoularidou, Alfredo Cuesta-Infante, and Kalyan Veeramachaneni. Modeling tabular data using conditional gan. Advances in neural information processing systems, 32, 2019.

- Bufang Yang, Siyang Jiang, Lilin Xu, Kaiwei Liu, Hai Li, Guoliang Xing, Hongkai Chen, Xiaofan Jiang, and Zhenyu Yan. Drhouse: An llm-empowered diagnostic reasoning system through harnessing outcomes from sensor data and expert knowledge. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies, 8(4):1–29, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yifan Yang, Xiaoyu Liu, Qiao Jin, Furong Huang, and Zhiyong Lu. Unmasking and quantifying racial bias of large language models in medical report generation. Communications medicine, 4(1):176, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Matthew D Zeiler and Rob Fergus. Visualizing and understanding convolutional networks. In European conference on computer vision, pages 818–833. Springer, 2014.

- Junhai Zhai, Jiaxing Qi, and Chu Shen. Binary imbalanced data classification based on diversity oversampling by generative models. Information Sciences, 585:313–343, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kexin Zhang, Baoyu Jing, K Selçuk Candan, Dawei Zhou, Qingsong Wen, Han Liu, and Kaize Ding. Cross-domain conditional diffusion models for time series imputation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.12412, 2025.

- Zongwei Zhou, Md Mahfuzur Rahman Siddiquee, Nima Tajbakhsh, and Jianming Liang. Unet++: Redesigning skip connections to exploit multiscale features in image segmentation. IEEE transactions on medical imaging, 39(6):1856–1867, 2019.

- Roberto V Zicari, John Brodersen, James Brusseau, Boris Düdder, Timo Eichhorn, Todor Ivanov, Georgios Kararigas, Pedro Kringen, Melissa McCullough, Florian Möslein, et al. Z-inspection®: a process to assess trustworthy ai. IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society, 2(2):83–97, 2021.

| Publication | Application | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|

| Kumar et al. (2020) [71] | Smart Cities | Highlights the embedding of ethical foundations in AI system design and development, focusing on practical applications in smart cities. |

| Verma et al. (2020) [129] | Counterfactual Explanations | Offers a rubric to evaluate counterfactual algorithms, identifying research directions for this critical aspect of model explainability. |

| Kaur et al. (2021) [64] | General AI systems | Consolidates approaches for trustworthy AI based on the European Union’s principles, presenting a structured overview for achieving reliable systems. |

| Kaur et al. (2022) [65] | General AI systems | Provides a comprehensive analysis of the requirements for trustworthy AI, including fairness, explainability, accountability, and reliability, with approaches to mitigate risks and improve societal acceptance. |

| Saraswat et al. (2022) [112] | Healthcare 5.0 [90] | Provides a taxonomy and case studies demonstrating the potential of explainable AI in improving operational efficiency and patient trust using privacy-preserving federated learning frameworks. |

| Liu et al. (2023) [79] | Large Language Models (LLMs) | Explores the alignment of LLMs with safety, fairness, and social norms, providing empirical evaluations to highlight alignment challenges. |

| Band et al. (2023) [18] | Medical Decision-Making | Critically reviews XAI methodologies like SHAP [80], LIME [110], and Grad-CAM [115], emphasizing their usability and reliability for applications like tumor segmentation and disease diagnosis. |

| Albahri et al. (2023) [6] | Healthcare AI | Systematically reviews trustworthiness and explainability in healthcare AI, highlighting transparency and bias risks and proposing a taxonomy for integrating XAI methods into healthcare systems. |

| Li et al. (2023) [74] | General AI systems | Proposes a unified framework integrating fragmented approaches to AI trustworthiness, addressing challenges such as robustness, fairness, and privacy preservation. |

| Fehr et al. (2024) [49] | Medical AI in Europe | Assesses the transparency of CE-certified medical AI products, revealing significant documentation gaps and calling for stricter legal requirements to ensure safety and ethical compliance. |

| Ojha et al. (2024) [102] | Healthcare AI | Focuses on one specific area of trustworthiness, that is, uncertainty. |

| This paper | Digital Health | Provides a comprehensive review and discussion of the aspects of trustworthy AI in digital health systems, with a focus on robustness and explainability. |

| Name | Authors | Year | Method | Original Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denoising Autoencoder [130] | Vincent et al. | 2008 | Uses noisy data as input and the corresponding clean data as output to train | Denoising images |

| Masked Autoencoder [57] | He et al. | 2021 | The positions of the missing patches are used to improve reconstruction. | Recreates missing patches in images |

| Generalized Butterworth Filter [114] | Selesnick and Burrus | 1998 | A Butterworth filter is a signal filter with a maximally flat passband response, minimizing ripples and ensuring smooth attenuation to the stopband. | Reduces noise in time-series data |

| Missing data imputation with Fuzzy c-means clustering [14] | Aydilek and Arslan | 2013 | A hybrid approach combines fuzzy c-means clustering, support vector regression, and a genetic algorithm to estimate missing values. | Improves imputation performance, outperforming zero imputation and other traditional methods. |

| ActiLabel [7] | Alinia et al. | 2020 | Dependency graphs to capture structural similarities and map activity labels between domains. | Improve activity recognition’s usability and performance |

| Missing Sensor Data Reconstruction Algorithm [89] | Mamun et al. | 2022 | Proposes an algorithm to reconstruct missing input data in sensor-based health monitoring systems, improving prediction accuracy on multiple activity classification benchmarks. | Reconstructing missing sensor data |

| CIM: Clustering-based Energy-Efficient Data Imputation Method [62] | Hussein and Bhat | 2023 | CIM detects missing sensors, predicts their clusters for imputation using a mapping table, and determines activities through imputation-aware classification or a reliable activity classifier. | Detecting and imputing missing sensor data |

| Cross-Domain Conditional Diffusion Models for Time Series Imputation [143] | Zhang et al. | 2025 | Introduces a diffusion-based method for cross-domain time series imputation that handles domain shifts and missing data via spectral interpolation and consistency alignment. | Time series data |

| Name | Authors | Year | Method | Data Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multimodal deep learning [100] | Ngiam et al. | 2011 | Bimodal deep autoencoder and Restricted Boltzmann Machine to outperform unimodal classifiers | Video, Audio |

| SMOTE [31] | Chawla et al. | 2002 | K-Nearest-neighbor based synthetic data generation | Tabular, Transformed features |

| AdaSYN [56] | He et al. | 2008 | Synthetic data generator with higher priority near the decision boundary | Tabular, Transformed features |

| CTGAN [138] | Xu et al. | 2019 | A modified GAN for tabular data with different processing for categorical and numerical features | Tabular |

| Binary Imbalanced Data Classification [142] | Zhai et al. | 2021 | GAN and discarding of batch data based on silhouette score | Tabular |

| AIMEN and R-AIMEN [85] | Mamun et al. | 2024 | CTGAN based data balancing with or without restrictions on similarity and type of the generated data | Tabular |

| MetaBoost [116] | Shah et al. | 2025 | Hybrid data balancing method that creates batches of synthetic data from weighted combinations of multiple balancing methods | Tabular |

| Dropout [124] | Srivastava et al. | 2014 | Randomly disables a number of neurons of the previous layer during training time. In the inference time, the weights are adjusted to maintain consistency. | Any data type |

| Knowledge-guided transformer for forecasting [107] | Qi et al. | 2021 | Uses future knowledge (future promotions) to improve performance of forecasting | Time-series |

| Name | Authors | Year | Method | Data Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIME [110] | Ribeiro et al. | 2016 | Surrogate interpretable model for estimating effect. | Tabular, Text, Image |

| Shapley [117] | L. Shapley | 1953 | Measure effect of a feature on different coalitions of all other features. | Tabular, Time-series, Image |

| SHAP [80] | Lundberg and Lee | 2017 | Efficient approximation based on Shapley (practical when the number of features is large). | Tabular, Time-series, Image |

| GradCAM [115] | Selvaraju et al. | 2017 | Generates class-specific heatmaps by calculating the gradients of the target class w.r.t. feature maps. | Image |

| Layer-wise Relevance Propagation [24] | Binder et al. | 2016 | Assigns relevance scores to input features by propagating the output decision backwards. | Image, Tabular, Text |

| Integrated Gradients [126] | Sundararajan et al. | 2017 | A path-based attribution method that assigns feature importance by accumulating gradients from a baseline to the input. | Image |

| NICE [26] | Brughmans et al. | 2023 | Counterfactual explanation based on a modified nearest unlike neighbor. | Tabular |

| DiCE [98] | Mothilal et al. | 2020 | Counterfactual explanations that optimize on validity, proximity, diversity, and sparsity. | Tabular |

| Semi-factual explanation [13] | Aryal and Keane | 2024 | Finds alternate feature values on the same class. Can be counterfactual (CF)-free or CF-guided. | Tabular |

| Multi-Objective Counterfactuals [41] | Dandl et al. | 2020 | Counterfactual method satisfying 4 objective functions: validity, distance, sparsity, distribution sanity. | Tabular |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).