Submitted:

25 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

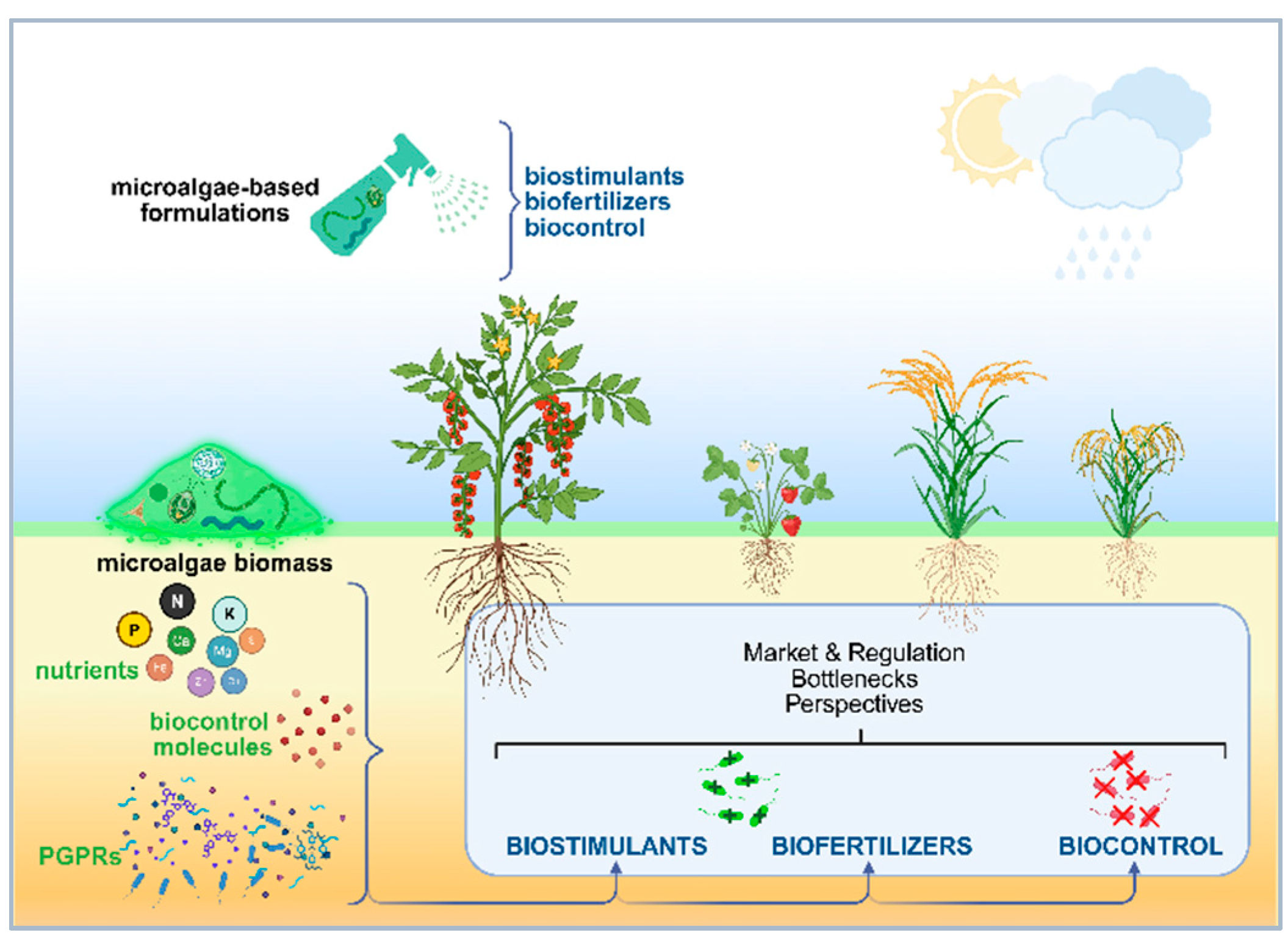

2. The Use of Microalgae and Cyanobacteria as Biostimulants

3. Biofertilizers

3.1. Nitrogen-Fixing Biofertilizers

3.2. Phosphorus and Potassium Solubilizing Biofertilizers

3.3. Zinc Solubilizing Biofertilizers

3.4. Iron Solubilizing Biofertilizers

3.5. Phytostimulators

3.6. Microalgae and Cyanobacteria-Based Biofertilizers

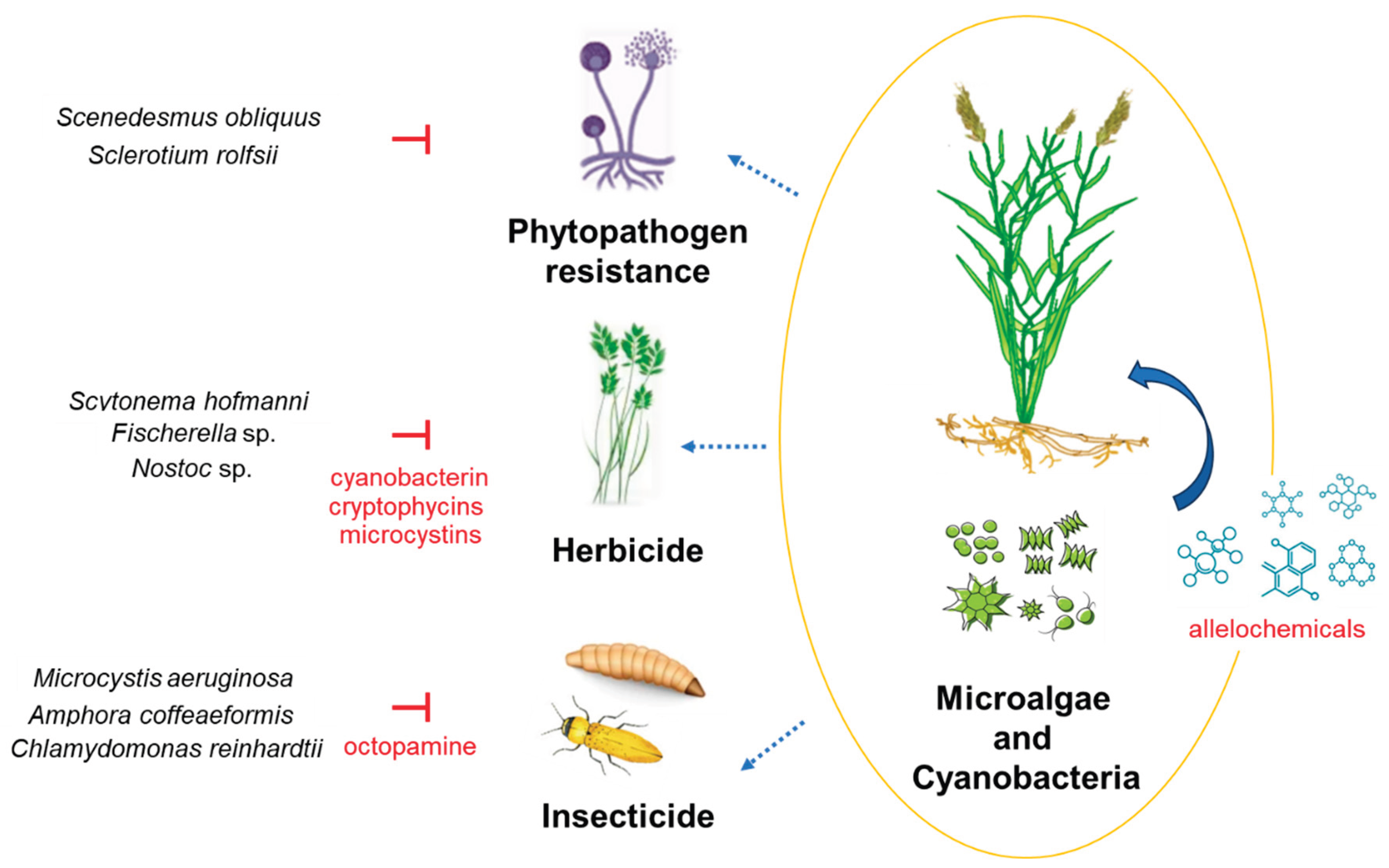

4. Biocontrol

4.1. Phytopathogen Resistance

4.2. Microalgae as Herbicides

4.3. Microalgae as Insecticides

5. Commercialized Microalgae- and Cyanobacteria-Based Products

6. Bottlenecks and Future Perspectives

9. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ren, C.G.; Kong, C.C.; Li, S.M.; Wang, X.J.; Yu, X.; Wang, Y.C.; Qin, S.; Cui, H.L. Symbiotic Microalgae and Microbes: A New Frontier in Saline Agriculture. Front Microbiol 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.G.; Kong, C.C.; Liu, Z.Y.; Zhong, Z.H.; Yang, J.C.; Wang, X.L.; Qin, S. A Perspective on Developing a Plant ‘Holobiont’ for Future Saline Agriculture. Front Microbiol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A. Soil Salinization Management for Sustainable Development: A Review. J Environ Manage 2021, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, J.; Daliakopoulos, I.N.; Del Moral, F.; Hueso, J.J.; Tsanis, I.K. A Review of Soil-Improving Cropping Systems for Soil Salinization. Agronomy 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito-Lopez, C.; Van Der Wielen, N.; Barbosa, M.; Karlova, R. Plant Growth-Promoting Microbes and Microalgae-Based Biostimulants: Sustainable Strategy for Agriculture and Abiotic Stress Resilience. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2025, 380.

- Crystal-Ornelas, R.; Thapa, R.; Tully, K.L. Soil Organic Carbon Is Affected by Organic Amendments, Conservation Tillage, and Cover Cropping in Organic Farming Systems: A Meta-Analysis. Agric Ecosyst Environ 2021, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihan, A. A Review of Climate Change Mitigation and Agriculture Sustainability through Soil Carbon Sequestration. Journal of Agriculture Sustainability and Environment 2023, 2, 23–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Gonzalez, L.M.; de-Bashan, L.E. The Potential of Microalgae–Bacteria Consortia to Restore Degraded Soils. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, A.L.; Weyers, S.L.; Goemann, H.M.; Peyton, B.M.; Gardner, R.D. Microalgae, Soil and Plants: A Critical Review of Microalgae as Renewable Resources for Agriculture. Algal Res 2021, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinola, M.V.; Díaz-Santos, E. Microalgae Nutraceuticals: The Role of Lutein in Human Health. In Microalgae Biotechnology for Food, Health and High Value Products; 2020.

- León-Bañares, R.; González-Ballester, D.; Galván, A.; Fernández, E. Transgenic Microalgae as Green Cell-Factories. Trends Biotechnol 2004, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, N.; Sharma, A.; Sundaram, S. The Role of PGPB-Microalgae Interaction in Alleviating Salt Stress in Plants. Curr Microbiol 2024, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmonaut® Agriculture Biologicals Market: 2025 Growth & Research Guide. https://farmonaut.com/blogs/agriculture-investments-2025-sustainable-growth-guide.

- Barkia, I.; Saari, N.; Manning, S.R. Microalgae for High-Value Products towards Human Health and Nutrition. Mar Drugs 2019, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vangenechten, B.; De Coninck, B.; Ceusters, J. How to Improve the Potential of Microalgal Biostimulants for Abiotic Stress Mitigation in Plants? Front Plant Sci 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, J.; Ahmad, S.; Malik, M. Nitrogenous Fertilizers: Impact on Environment Sustainability, Mitigation Strategies, and Challenges. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, R.; Sood, A.; Ratha, S.K. ; K.; Singh, P. Cyanobacteria as a “Green” Option for Sustainable Agriculture. In Cyanobacteria: An Economic Perspective; 2013.

- Ferreira, A.; Bastos, C.R.V.; Marques-dos-Santos, C.; Acién-Fernandez, F.G.; Gouveia, L. Algaeculture for Agriculture: From Past to Future. Frontiers in Agronomy 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronga, D.; Biazzi, E.; Parati, K.; Carminati, D.; Carminati, E.; Tava, A. Microalgal Biostimulants and Biofertilisers in Crop Productions. Agronomy 2019, 9, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Huang, P.; Yu, J.; Wang, P.; Jiang, H. Bin; Jiang, Y.; Deng, S.; Huang, Z.; Yu, J.; Zhu, W. Efficient Wastewater Treatment and Biomass Co-Production Using Energy Microalgae to Fix C, N, and P. RSC Adv 2025, 15, 14030–14041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmar, P.; Kumar, R.; Neha, Y.; Srivatsan, V. Microalgae as next Generation Plant Growth Additives: Functions, Applications, Challenges and Circular Bioeconomy Based Solutions. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyeaka, H.; Miri, T.; Obileke, K.C.; Hart, A.; Anumudu, C.; Al-Sharify, Z.T. Minimizing Carbon Footprint via Microalgae as a Biological Capture. Carbon Capture Science and Technology 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Jardin, P. Plant Biostimulants: Definition, Concept, Main Categories and Regulation. Sci Hortic 2015, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaiese, P.; Corrado, G.; Colla, G.; Kyriacou, M.C.; Rouphael, Y. Renewable Sources of Plant Biostimulation: Microalgae as a Sustainable Means to Improve Crop Performance. Front Plant Sci 2018, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabili, A.; Minaoui, F.; Hakkoum, Z.; Douma, M.; Meddich, A.; Loudiki, M. A Comprehensive Review of Microalgae and Cyanobacteria-Based Biostimulants for Agriculture Uses. Plants 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Vaz, A.; León, R.; Díaz-Santos, E.; Vigara, J.; Raposo, S. Using Agro-Industrial Wastes for Mixotrophic Growth and Lipids Production by the Green Microalga Chlorella sorokiniana. N Biotechnol 2019, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozenberg, J.M.; Sorokin, B.A.; Mukhambetova, A.N.; Emelianova, A.A.; Kuzmin, V.V.; Belogurova-Ovchinnikova, O.Y.; Kuzmin, D.V. Recent Advances and Fundamentals of Microalgae Cultivation Technology. Biotechnol J 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Kuijpers, T.C.; Veldhoen, B.; Ternbach, M.B.; Tramper, J.; Mur, L.R.; Wijffels, R.H. Specific Growth Rate of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Chlorella sorokiniana under Medium Duration Light/Dark Cycles: 13-87 s. Prog Ind Microbiol 1999, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, G.; Biondi, N.; Rodolfi, L.; Tredici, M.R. Plant Biostimulants from Cyanobacteria: An Emerging Strategy to Improve Yields and Sustainability in Agriculture. Plants 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jithesh, M.N.; Shukla, P.S.; Kant, P.; Joshi, J.; Critchley, A.T.; Prithiviraj, B. Physiological and Transcriptomics Analyses Reveal That Ascophyllum nodosum Extracts Induce Salinity Tolerance in Arabidopsis by Regulating the Expression of Stress Responsive Genes. J Plant Growth Regul 2019, 38, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.S.; Kumar, A.; Rai, A.N.; Singh, D.P. Cyanobacteria: A Precious Bio-Resource in Agriculture, Ecosystem, and Environmental Sustainability. Front Microbiol 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, T.; Saud, S.; Gu, L.; Khan, I.; Fahad, S.; Zhou, R. Cyanobacteria: Harnessing the Power of Microorganisms for Plant Growth Promotion, Stress Alleviation, and Phytoremediation in the Era of Sustainable Agriculture. Plant Stress 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Quintero, Á.; Fernandes, S.C.M.; Beigbeder, J.B. Overview of Microalgae and Cyanobacteria-Based Biostimulants Produced from Wastewater and CO2 Streams towards Sustainable Agriculture: A Review. Microbiol Res 2023, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Huang, Y.; Guo, M.; Song, J.; Zhang, T.; Long, Y.; Wang, B.; Liu, H. A Potential Biofertilizer—Siderophilic Bacteria Isolated From the Rhizosphere of Paris polyphylla Var. yunnanensis. Front Microbiol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorentino, S.; Bellani, L.; Santin, M.; Castagna, A.; Echeverria, M.C.; Giorgetti, L. Effects of Microalgae as Biostimulants on Plant Growth, Content of Antioxidant Molecules and Total Antioxidant Capacity in Chenopodium quinoa Exposed to Salt Stress. Plants 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Park, Y.J.; Choi, Y. Bin; Truong, T.Q.; Huynh, P.K.; Kim, Y.B.; Kim, S.M. Physiological Effects and Mechanisms of Chlorella vulgaris as a Biostimulant on the Growth and Drought Tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plants 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minaoui, F.; Hakkoum, Z.; Chabili, A.; Douma, M.; Mouhri, K.; Loudiki, M. Biostimulant Effect of Green Soil Microalgae Chlorella vulgaris Suspensions on Germination and Growth of Wheat (Triticum aestivum Var. achtar) and Soil Fertility. Algal Res 2024, 82, 103655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Bella, E.; Baglieri, A.; Rovetto, E.I.; Stevanato, P.; Puglisi, I. Foliar Spray Application of Chlorella vulgaris Extract: Effect on the Growth of Lettuce Seedlings. Agronomy 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitau, M.M.; Farkas, A.; Balla, B.; Ördög, V.; Futó, Z.; Maróti, G. Strain-Specific Biostimulant Effects of Chlorella and Chlamydomonas Green Microalgae on Medicago truncatula. Plants 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.J.; Shim, C.K.; Kim, Y.K.; Ko, B.G.; Park, J.H.; Hwang, S.G.; Kim, B.H. Effect of Biostimulator Chlorella fusca on Improving Growth and Qualities of Chinese Chives and Spinach in Organic Farm. Plant Pathol J (Faisalabad) 2018, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Tawwab, M.; Mousa, M.A.A.; Mamoon, A.; Abdelghany, M.F.; Abdel-Hamid, E.A.A.; Abdel-Razek, N.; Ali, F.S.; Shady, S.H.H.; Gewida, A.G.A. Dietary Chlorella Vulgaris Modulates the Performance, Antioxidant Capacity, Innate Immunity, and Disease Resistance Capability of Nile Tilapia Fingerlings Fed on Plant-Based Diets. Anim Feed Sci Technol 2022, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuang, S.C.; Khin, M.C.; Chua, P.Q.D.; Luo, Y.D. Use of Spirulina Biomass Produced from Treatment of Aquaculture Wastewater as Agricultural Fertilizers. Algal Res 2016, 15, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, H.; Prasanna, R.; Ramakrishnan, B.; Bidyarani, N.; Babu, S.; Thapa, S.; Renuka, N. Influence of Cyanobacterial Inoculation on the Culturable Microbiome and Growth of Rice. Microbiol Res 2015, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fimbres-Olivarria, D.; Carvajal-Millan, E.; Lopez-Elias, J.A.; Martinez-Robinson, K.G.; Miranda-Baeza, A.; Martinez-Cordova, L.R.; Enriquez-Ocaña, F.; Valdez-Holguin, J.E. Chemical Characterization and Antioxidant Activity of Sulfated Polysaccharides from Navicula sp. Food Hydrocoll 2018, 75, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, K.; Romanowska-Duda, Z.; Messyasz, B. Cultivation of Energy Crops by Ecological Methods under the Conditions of Global Climate and Environmental Changes with the Use of Diatom Extract as a Natural Source of Chemical Compounds. Acta Physiol Plant 2020, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran Marella, T.; Saxena, A.; Tiwari, A. Diatom Mediated Heavy Metal Remediation: A Review. Bioresour Technol 2020, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhamji, S.; Haydari, I.; Sbihi, K.; Aziz, K.; Elleuch, J.; Kurniawan, T.A.; Chen, Z.; Yap, P.S.; Aziz, F. Uncovering Applicability of Navicula permitis Algae in Removing Phenolic Compounds: A Promising Solution for Olive Mill Wastewater Treatment. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2023, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calatrava, V.; Hom, E.F.Y.; Guan, Q.; Llamas, A.; Fernández, E.; Galván, A. Genetic Evidence for Algal Auxin Production in Chlamydomonas and Its Role in Algal-Bacterial Mutualism. iScience 2024, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Tiji, Y.; Fields, F.J.; Yang, Y.; Heredia, V.; Horn, S.J.; Keremane, S.R.; Jin, M.M.; Mayfield, S.P. Optimized Production of a Bioactive Human Recombinant Protein from the Microalgae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii Grown at High Density in a Fed-Batch Bioreactor. Algal Res 2022, 66, 102786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamas, A.; Leon-Miranda, E.; Tejada-Jimenez, M. Microalgal and Nitrogen-Fixing Bacterial Consortia: From Interaction to Biotechnological Potential. Plants 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, I.; Chojnacka, K. Algae as Production Systems of Bioactive Compounds. Eng Life Sci 2015, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vessey, J.K. Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria as Biofertilizers; Plant and Soil, 2003, 255, 571-586. [CrossRef]

- Mahanty, T.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Goswami, M.; Bhattacharyya, P.; Das, B.; Ghosh, A.; Tribedi, P. Biofertilizers: A Potential Approach for Sustainable Agriculture Development. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2017, 24, 3315–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, D.; Ansari, M.W.; Sahoo, R.K.; Tuteja, N. Biofertilizers Function as Key Player in Sustainable Agriculture by Improving Soil Fertility, Plant Tolerance and Crop Productivity. Microb Cell Fact 2014, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobbe and Hiltner. Bodenimpfung für anbau von leguminosen. Sächsische. Landwirtschaftliche Zeitschrift, 1896, 44, pp. [Google Scholar]

- Nosheen, S.; Ajmal, I.; Song, Y. Microbes as Biofertilizers, a Potential Approach for Sustainable Crop Production. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloo, B.N.; Tripathi, V.; Makumba, B.A.; Mbega, E.R. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacterial Biofertilizers for Crop Production: The Past, Present, and Future. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, A.I.; Fadaka, A.O.; Gokul, A.; Bakare, O.O.; Aina, O.; Fisher, S.; Burt, A.F.; Mavumengwana, V.; Keyster, M.; Klein, A. Biofertilizer: The Future of Food Security and Food Safety. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herridge, D.F.; Peoples, M.B.; Boddey, R.M. Global Inputs of Biological Nitrogen Fixation in Agricultural Systems. Plant Soil 2008, 311, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnahal, A.S.M.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Saad, A.M.; Desoky, E.S.M.; El-Tahan, A.M.; Rady, M.M.; AbuQamar, S.F.; El-Tarabily, K.A. The Use of Microbial Inoculants for Biological Control, Plant Growth Promotion, and Sustainable Agriculture: A Review. Eur J Plant Pathol 2022, 162, 759–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleke, R.A.; Raimi, A.R.; Roopnarain, A.; Mokubedi, S.M. Status and Prospects of Bacterial Inoculants for Sustainable Management of Agroecosystems. In; 2019.

- Saleem, I.; Asad, W.; Kiran, T.; Asad, S.B.; Khaliq, S.; Ali Mohammed Al-Harethi, A.; Mallasiy, L.O.; Shah, T.A. Enhancing Spinach Growth with a Biofertilizer Derived from Chicken Feathers Using a Keratinolytic Bacterial Consortium. BMC Microbiol 2025, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez, C.; Jimenez-Ríos, L.; Iniesta-Pallares, M.; Jurado-Flores, A.; Molina-Heredia, F.P.; Ng, C.K.Y.; Mariscal, V. Symbiosis between Cyanobacteria and Plants: From Molecular Studies to Agronomic Applications. J Exp Bot 2023, 74, 6145–6157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Li, Y.; Han, X.; Li, K.; Zhao, M.; Guo, L.; Li, S.; Wang, K.; Qin, K.; Duan, J.; et al. Microalgae-Based Biofertilizer Improves Fruit Yield and Controls Greenhouse Gas Emissions in a Hawthorn Orchard. PLoS One 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordell, D.; Drangert, J.O.; White, S. The Story of Phosphorus: Global Food Security and Food for Thought. Global Environmental Change 2009, 19, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumare, A.; Boubekri, K.; Lyamlouli, K.; Hafidi, M.; Ouhdouch, Y.; Kouisni, L. From Isolation of Phosphate Solubilizing Microbes to Their Formulation and Use as Biofertilizers: Status and Needs. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gureev, A.P.; Kryukova, V.A.; Eremina, A.A.; Alimova, A.A.; Kirillova, M.S.; Filatova, O.A.; Moskvitina, M.I.; Kozin, S.V.; Lyasota, O.M.; Gureeva, M.V. Plant-Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria Azospirillum Partially Alleviate Pesticide-Induced Growth Retardation and Oxidative Stress in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Plant Growth Regul 2024, 104, 503–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Kumari, A.; Sharma, S.; Alzahrani, O.M.; Noureldeen, A.; Darwish, H. Identification, Characterization and Optimization of Phosphate Solubilizing Rhizobacteria (PSRB) from Rice Rhizosphere. Saudi J Biol Sci 2022, 29, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarikhani, M.R.; Khoshru, B.; Greiner, R. Isolation and Identification of Temperature Tolerant Phosphate Solubilizing Bacteria as a Potential Microbial Fertilizer. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2019, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.K.; Singh, S.; Benjamin, J.C.; Singh, V.R.; Bisht, D.; Lal, R.K. Plant Growth-Promoting Activities of Serratia marcescens and Pseudomonas fluorescens on Capsicum annuum L. Plants. Ecological Frontiers 2024, 44, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.; Tahreem, N.; Zafar, M.; Raza, G.; Shahid, M.; Zunair, M.; Iram, W.; Zahra, S.T. Occurrence of Diverse Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria in Soybean [Glycine Max (L.) Merrill] Root Nodules and Their Prospective Role in Enhancing Crop Yield. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 2024, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, E.; Ahmad, A.A.; Abdo, E.S.; Bakr, M.A.; Khalil, M.A.; Abdallah, Y.; Ogunyemi, S.O.; Mohany, M.; Al-Rejaie, S.S.; Shou, L.; et al. Suppression of Root Rot Fungal Diseases in Common Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) through the Application of Biologically Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Zhang, H.; Bai, X.; Jiang, B. The Peanut Root Exudate Increases the Transport and Metabolism of Nutrients and Enhances the Plant Growth-Promoting Effects of Burkholderia pyrrocinia Strain P10. BMC Microbiol 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akintokun, A.K.; Ezaka, E.; Akintokun, P.O.; Shittu, O.B.; Taiwo, L.B. Isolation, Screening and Response of Maize to Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria Inoculants. Scientia Agriculturae Bohemica 2019, 50, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubekri, K.; Soumare, A.; Mardad, I.; Lyamlouli, K.; Hafidi, M.; Ouhdouch, Y.; Kouisni, L. The Screening of Potassium-and Phosphate-Solubilizing Actinobacteria and the Assessment of Their Ability to Promote Wheat Growth Parameters. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, R.; Zhang, H.; Wei, G.; Li, Z. Beneficial Bacteria Activate Nutrients and Promote Wheat Growth under Conditions of Reduced Fertilizer Application. BMC Microbiol 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, R.; Kaur, T.; Negi, R.; Kour, D.; Kumar, S.; Yadav, A.; Singh, S.; Chaubey, K.K.; Rai, A.K.; Shreaz, S.; et al. Bioformulation of Mineral Solubilizing Microbes as Novel Microbial Consortium for the Growth Promotion of Wheat (Triticum aestivum) under the Controlled and Natural Conditions. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh Meena, V.; Ram Maurya, B.; Kumari Meena, S.; Kumar Mishra, P.; Kumar Bisht, J.; Pattanayak, A. Potassium Solubilization: Strategies to Mitigate Potassium Deficiency in Agricultural Soils.

- Cakmak, I.; McLaughlin, M.J.; White, P. Zinc for Better Crop Production and Human Health. Plant Soil 2017, 411, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain Shah, A.; Naz, I.; Ahmad, H.; Nasreen Khokhar, S.; Khan, K. Impact of Zinc Solubilizing Bacteria on Zinc Contents of Wheat. J. Agric. & Environ. Sci 2016, 16, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, A.A.Y.A.; Gebreel, H.M.; Youssef, H.A.I.A.E. Biofertilizer Effect of Some Zinc Dissolving Bacteria Free and Encapsulated on Zea mays Growth. Arch Microbiol 2023, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnwal, A. Enhancing Zinc Levels in Solanum lycopersicum L. through Biofortification with Plant Growth-Promoting Pseudomonas spp. Isolated from Cow Dung. Biotechnologia 2023, 104, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briat, J.F.; Dubos, C.; Gaymard, F. Iron Nutrition, Biomass Production, and Plant Product Quality. Trends Plant Sci 2015, 20, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Sindhu, S.S. Iron Sensing, Signalling and Acquisition by Microbes and Plants under Environmental Stress: Use of Iron-Solubilizing Bacteria in Crop Biofortification for Sustainable Agriculture. Plant Science 2025, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofeeva, A.M.; Galyamova, M.R.; Sedykh, S.E. Bacterial Siderophores: Classification, Biosynthesis, Perspectives of Use in Agriculture. Plants 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazanfar, S.; Hussain, A.; Dar, A.; Ahmad, M.; Anwar, H.; Al Farraj, D.A.; Rizwan, M.; Iqbal, R. Prospects of Iron Solubilizing Bacillus Species for Improving Growth and Iron in Maize (Zea mays L.) under Axenic Conditions. Sci Rep 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Palmero, B.; Lucas, J.A.; Montalbán, B.; García-Villaraco, A.; Gutierrez-Mañero, J.; Ramos-Solano, B. Iron Deficiency in Tomatoes Reversed by Pseudomonas Strains: A Synergistic Role of Siderophores and Plant Gene Activation. Plants 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidi, L.; Gallaher, S.D.; Ben-David, E.; Purvine, S.O.; Fillmore, T.L.; Nicora, C.D.; Craig, R.J.; Schmollinger, S.; Roje, S.; Blaby-Haas, C.E.; et al. Pumping Iron: A Multi-Omics Analysis of Two Extremophilic Algae Reveals Iron Economy Management. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brick, M.B.; Hussein, M.H.; Mowafy, A.M.; Hamouda, R.A.; Ayyad, A.M.; Refaay, D.A. Significance of Siderophore-Producing Cyanobacteria on Enhancing Iron Uptake Potentiality of Maize Plants Grown under Iron-Deficiency. Microb Cell Fact 2025, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, M.; Omae, N.; Tsuda, K. Inter-Organismal Phytohormone Networks in Plant-Microbe Interactions. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2022, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, W.; Dong, N.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Zhou, W.; Qian, Q.; Chu, C.; Tong, H. Understanding Brassinosteroid-Centric Phytohormone Interactions for Crop Improvement. J Integr Plant Biol 2025, 67, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Uesaka, K. Nitrogen Fixation in Cyanobacteria. In Cyanobacterial Physiology: From Fundamentals to Biotechnology; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 29–45 ISBN 9780323961066.

- Neilson, A.; I~ippka, I.; Kv~isawa, R. Heterocyst Formation and Nitrogenase Synthesis in Anabaena sp. A Kinetic Study; Springer-Verlag, 1971; Vol. 76;

- Kollmen, J.; Strieth, D. The Beneficial Effects of Cyanobacterial Co-Culture on Plant Growth. Life 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Shah, S.T.; Rahman, H.; Irshad, M.; Iqbal, A. Effect of IAA on in Vitro Growth and Colonization of Nostoc in Plant Roots. Front Plant Sci 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toribio, A.J.; Suárez-Estrella, F.; Jurado, M.M.; López, M.J.; López-González, J.A.; Moreno, J. Prospection of Cyanobacteria Producing Bioactive Substances and Their Application as Potential Phytostimulating Agents. Biotechnology Reports 2020, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, J.; Nakano, T. Reconstitution of a Blasia-Nostoc Symbiotic Association under Axenic Conditions. Nova Hedwigia 1990, 50, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eily, A.N.; Pryer, K.M.; Li, F.W. A First Glimpse at Genes Important to the Azolla–Nostoc Symbiosis. Symbiosis 2019, 78, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, C.; Navarro, J.A.; Molina-Heredia, F.P.; Mariscal, V. Endophytic Colonization of Rice (Oryza sativa L.) by the Symbiotic Strain Nostoc punctiforme PCC 73102. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 2020, 33, 1040–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, S.; Saadaoui, I.; Bibi, A.; Al-Ghouti, M.; Abu-Dieyeh, M.H. Applications, Advancements, and Challenges of Cyanobacteria-Based Biofertilizers for Sustainable Agro and Ecosystems in Arid Climates. Bioresour Technol Rep 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iniesta-Pallarés, M.; Álvarez, C.; Gordillo-Cantón, F.M.; Ramírez-Moncayo, C.; Alves-Martínez, P.; Molina-Heredia, F.P.; Mariscal, V. Sustaining Rice Production through Biofertilization with N2-Fixing Cyanobacteria. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghotbi-Ravandi, A.A.; Shariatmadari, Z.; Riahi, H.; Hassani, S.B.; Heidari, F.; Nohooji, M.G. Enhancement of Essential Oil Production and Expression of Some Menthol Biosynthesis-Related Genes in Mentha piperita Using Cyanobacteria. Iran J Biotechnol 2023, 21, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Ríos, L.; Torrado, A.; González-Pimentel, J.L.; Iniesta-Pallarés, M.; Molina-Heredia, F.P.; Mariscal, V.; Álvarez, C. Emerging Nitrogen-Fixing Cyanobacteria for Sustainable Cotton Cultivation. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Encinas, J.P.; Ruiz-Cruz, S.; Juárez, J.; Ornelas-Paz, J. de J.; Del Toro-Sánchez, C.L., Ed.; Márquez-Ríos, E. Proteins from Microalgae: Nutritional, Functional and Bioactive Properties. Foods 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Youssef, S.M.; El-Serafy, R.S.; Ghanem, K.Z.; Elhakem, A.; Abdel Aal, A.A. Foliar Spray or Soil Drench: Microalgae Application Impacts on Soil Microbiology, Morpho-Physiological and Biochemical Responses, Oil and Fatty Acid Profiles of Chia Plants under Alkaline Stress. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sayed, H.S.; Hassan, A.; Barakat, K.M.; Ghonam, H.E.B. Improvement of Growth and Biochemical Constituents of Rosmarinus officinalis by Fermented Spirulina maxima Biofertilizer. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2024, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renuka, N.; Guldhe, A.; Prasanna, R.; Singh, P.; Bux, F. Microalgae as Multi-Functional Options in Modern Agriculture: Current Trends, Prospects and Challenges. Biotechnol Adv 2018, 36, 1255–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udaypal, U.; Goswami, R.K.; Verma, P. Strategies for Improvement of Bioactive Compounds Production Using Microalgal Consortia: An Emerging Concept for Current and Future Perspective. Algal Res 2024, 82, 103664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchiosi, R.; dos Santos, W.D.; Constantin, R.P.; de Lima, R.B.; Soares, A.R.; Finger-Teixeira, A.; Mota, T.R.; de Oliveira, D.M.; Foletto-Felipe, M. de P. ; Abrahão, J.; et al. Biosynthesis and Metabolic Actions of Simple Phenolic Acids in Plants. Phytochemistry Reviews 2020, 19, 865–906. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Tang, Z.; Yang, D.; Dai, X.; Chen, H. Enhanced Growth and Auto-Flocculation of Scenedesmus quadricauda in Anaerobic Digestate Using High Light Intensity and Nanosilica: A Biomineralization-Inspired Strategy. Water Res 2023, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Ren, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Pang, X.; Han, J. Microalgae and Microbial Inoculant as Partial Substitutes for Chemical Fertilizer Enhance Polygala Tenuifolia Yield and Quality by Improving Soil Microorganisms. Front Plant Sci 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovinella, M.; Palmieri, M.; Papa, S.; Auciello, C.; Ventura, R.; Lombardo, F.; Race, M.; Lubritto, C.; di Cicco, M.R.; Davis, S.J.; et al. Biosorption of Rare Earth Elements from Luminophores by G. sulphuraria (Cyanidiophytina, Rhodophyta). Environ Res 2023, 239, 117281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, A.; Hussain, N.; Saba, S.; Bilal, M. Actinomycetes, Cyanobacteria, and Fungi: A Rich Source of Bioactive Molecules. In Microbial Biomolecules: Emerging Approach in Agriculture, Pharmaceuticals and Environment Management; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 113–133 ISBN 9780323994767.

- Chaïb, S.; Pistevos, J.C.A.; Bertrand, C.; Bonnard, I. Allelopathy and Allelochemicals from Microalgae: An Innovative Source for Bio-Herbicidal Compounds and Biocontrol Research. Algal Res 2021, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, N.T.; Rickards, R.W.; Rothschild, J.M.; Smith, G.D. Allelopathic Actions of the Alkaloid 12-Epi-Hapalindole E Isonitrile and Calothrixin A from Cyanobacteria of the Genera Fischerella and Calothrix; 2000; Vol. 12;

- Sasso, S.; Pohnert, G.; Lohr, M.; Mittag, M.; Hertweck, C. Microalgae in the Postgenomic Era: A Blooming Reservoir for New Natural Products. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2012, 36, 761–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden, D.G.; Bourdelais, A.J.; Jacocks, H.; Michelliza, S.; Naar, J. Natural and Derivative Brevetoxins: Historical Background, Multiplicity, and Effects. Environ Health Perspect 2005, 113, 621–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, A.; Murata, M.; Oshima, Y.; Iwashita, T.; Yasumoto, T. Some Chemical Properties of Maitotoxin, a Putative Calcium Channel Agonist Isolated from a Marine Dinoflagellate1; 1988; Vol. 104;

- DellaGreca, M.; Zarrelli, A.; Fergola, P.; Cerasuolo, M.; Pollio, A.; Pinto, G. Fatty Acids Released by Chlorella Vulgaris and Their Role in Interference with Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata: Experiments and Modelling. J Chem Ecol 2010, 36, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, I.Z.; Huang, W.Y.; Wu, J.T. Allelochemicals of Botryococcus braunii (Chlorophyceae). J Phycol 2004, 40, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, R.P.; Sinha, R.P.; Incharoensakdi, A. The Cyanotoxin-Microcystins: Current Overview. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 2014, 13, 215–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaki, B.; Orjala, J.; Heilmann, J.; Linden, A.; Vogler, B.; Sticher, O. Novel Extracellular Diterpenoids with Biological Activity from the Cyanobacterium Nostoc commune. J Nat Prod 2000, 63, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asthana, R.K.; Srivastava, A.; Singh, A.P. ; Deepali; Singh, S. P.; Nath, G.; Srivastava, R.; Srivastava, B.S. Identification of an Antimicrobial Entity from the Cyanobacterium Fischerella sp. Isolated from Bark of Azadirachta Indica (Neem) Tree. J Appl Phycol 2006, 18, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajiyama, S.; Kanzakt, H.; Kawazu, K.; Kobayashi, A. Nostofungicidine, an Antifungal Lipopeptide from the Field-Grown Terrestrial Blue-Green Alga Nostoc commune; 1998; Vol. 39;

- Desbois, A.P.; Mearns-Spragg, A.; Smith, V.J. A Fatty Acid from the Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum Is Antibacterial against Diverse Bacteria Including Multi-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Marine Biotechnology 2009, 11, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouaddi, O.; Oukarroum, A.; Bouharroud, R.; Alouani, M.; EL blidi, A.; Qessaoui, R.; Radouane, N.; Errafii, K.; Hijri, M.; Hamadi, F.; et al. A Study of Antibacterial Efficacy of Tetraselmis rubens Extracts against Tomato Phytopathogenic Pseudomonas corrugata. Algal Res 2025, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, C.; Genevace, M.; Gama, F.; Coelho, L.; Pereira, H.; Varela, J.; Reis, M. Chlorella vulgaris and Tetradesmus obliquus Protect Spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) against Fusarium oxysporum. Plants 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandor, R.; Wagh, S.G.; Kelterborn, S.; Großkinsky, D.K.; Novak, O.; Olsen, N.; Paul, B.; Petřík, I.; Wu, S.; Hegemann, P.; et al. Cytokinin-Deficient Chlamydomonas reinhardtii CRISPR-Cas9 Mutants Show Reduced Ability to Prime Resistance of Tobacco against Bacterial Infection. Physiol Plant 2024, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, B.; Coelho, L.; Schulze, P.S.C.; Pereira, H.; Santos, T.; Maia, I.B.; Reis, M.; Varela, J. Antifungal Properties of Aqueous Microalgal Extracts. Bioresour Technol Rep 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamouda, R.; Hamouda, R.A.; El-Ansary, M.S.M. Potential of Plant-Parasitic Nematode Control in Banana Plants by Microalgae as a New Approach Towards Resistance; 2017; Vol. 27;

- Bang, K.H.; Lee, D.W.; Park, H.M.; Rhee, Y.H. Inhibition of Fungal Cell Wall Synthesizing Enzymes by Trans-Cinnamaldehyde. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2000, 64, 1061–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, J. 2011.

- Berry, J.P. Cyanobacterial Toxins as Allelochemicals with Potential Applications as Algaecides, Herbicides and Insecticides. Mar Drugs 2008, 6, 117–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koodkaew, I.; Sunohara, Y.; Matsuyama, S.; Matsumoto, H. Isolation of Ambiguine D Isonitrile from Hapalosiphon sp. and Characterization of Its Phytotoxic Activity. Plant Growth Regul 2012, 68, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankic, I.; Zelinka, R.; Ridoskova, A.; Gagic, M.; Pelcova, P.; Huska, D. Nano/Microparticles in Conjunction with Microalgae Extract as Novel Insecticides against Mealworm beetles, Tenebrio molitor. Sci Rep 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.E.; Mohafrash, S.M.M.; Fallatah, S.A.; El-Sayed, A.E.K.B.; Mossa, A.T.H. Eco-Friendly Larvicide of Amphora coffeaeformis and Scenedesmus obliquus Microalgae Extracts against Culex pipiens. J Appl Phycol 2021, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becher, P.G.; Jüttner, F. Insecticidal Compounds of the Biofilm-Forming Cyanobacterium Fischerella sp. In (ATCC 43239). In Proceedings of the Environmental Toxicology; 2005; Vol. 20; pp. 363–372. [Google Scholar]

- Becher, P.G.; Keller, S.; Jung, G.; Süssmuth, R.D.; Jüttner, F. Insecticidal Activity of 12-Epi-Hapalindole J Isonitrile. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 2493–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becher, P.G.; Jüttner, F. Insecticidal Activity - A New Bioactive Property of the Cyanobacterium Fischerella. Pol J Ecol 2006, 54, 653–662. [Google Scholar]

- Höckelmann, C.; Becher, P.G.; Von Reuß, S.H.; Jüttner, F. Sesquiterpenes of the Geosmin-Producing Cyanobacterium Calothrix PCC 7507 and Their Toxicity to Invertebrates. Zeitschrift fur Naturforschung - Section C Journal of Biosciences 2009, 64, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delaney, J.M.; Wilkins, R.M. AGAINST VARIOUS INSECT SPECIES; 1995; Vol. 33;

- Aguilar-Marcelino, L.; Pineda-Alegría, J.A.; Salinas-Sánchez, D.O.; Hernández-Velázquez, V.M.; Silva-Aguayo, G.I.; Navarro-Tito, N.; Sotelo-Leyva, C. In Vitro Insecticidal Effect of Commercial Fatty Acids, β-Sitosterol, and Rutin against the Sugarcane aphid, Melanaphis sacchari zehntner (Hemiptera: Aphididae). J Food Prot 2022, 85, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumalsamy, H.; Jang, M.J.; Kim, J.R.; Kadarkarai, M.; Ahn, Y.J. Larvicidal Activity and Possible Mode of Action of Four Flavonoids and Two Fatty Acids Identified in Millettia pinnata Seed toward Three Mosquito Species. Parasit Vectors 2015, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoveská, L.; Nielsen, S.L.; Eroldoğan, O.T.; Haznedaroglu, B.Z.; Rinkevich, B.; Fazi, S.; Robbens, J.; Vasquez, M.; Einarsson, H. Overview and Challenges of Large-Scale Cultivation of Photosynthetic Microalgae and Cyanobacteria. Mar Drugs 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, D.L.; Moreira, Í.T.A. Microalgae Biomass Production from Cultivation in Availability and Limitation of Nutrients: The Technical, Environmental and Economic Performance. J Clean Prod 2022, 370, 133538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Group | Biofertilization mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nostoc sp. | Cyanobacteria | Nitrogen fixation, phytohormone production, solubilization of P/K/Zn | [95,101] |

| Anabaena vaginicola ISB42 | Cyanobacteria | Phytohormone-linked nutrient uptake, peppermint oil enhancement | [102] |

| Nostoc spongiaeforme var. tenue ISB65 | Cyanobacteria | Phytohormone-linked nutrient uptake, peppermint oil enhancement | [102] |

| Synechococcus mundulus | Cyanobacteria | Siderophore production, enhanced Fe uptake in maize | [89] |

| Arthrospira platensis | Cyanobacteria | Phytohormone production, improved nutrient acquisition in chia | [105] |

| Spirulina maxima | Cyanobacteria (marketed as microalgae) |

Bioactive compounds enhancing growth and nutrient uptake in rosemary | [106] |

| Chlorella vulgaris | Microalgae | Phosphorus and potassium solubilization, auxin-like activity | [107] |

| Scenedesmus obliquus | Microalgae | P/K mobilization, root stimulation under stress | [107] |

| Dunaliella salina | Microalgae | Siderophore-mediated Fe uptake under deficiency | [88] |

| Dunaliella bardawil | Microalgae | Siderophore-mediated Fe uptake under deficiency | [88] |

| Dunaliella tertiolecta | Microalgae | Siderophore-mediated Fe uptake | [88] |

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | Microalgae | Associative biofertilization via bacterial consortia (N/P uptake) | [108] |

| Class ofcompound | Characteristics | Producingmicroorganisms | Hypothetical use in agriculture | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaloids | Nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds | Fischerella sp., Calothrix sp. | Natural bioinsecticides or antimicrobial agents for biocontrol | [115,116] |

| Polyketides | Structurally diverse metabolites derived from carboxylic acid precursors | Gambierdiscus toxicus, Karenia brevis | Broad-spectrum fungicides or bactericides for crops | [117,118] |

| Fatty acids | Extracellular free fatty acids with allelopathic activity | Chlorella vulgaris, Botryococcus braunii | Natural weed growth inhibitors (bioherbicides) | [119,120] |

| Peptides | Non-ribosomal peptides biosynthesized by multifunctional enzyme complexes |

Anabaena sp. PCC7120, Microcystis sp., Planktothrix sp., Oscillatoria limosa |

Plant defense promoters or biostimulants | [121] |

| Terpenoids | Organic compounds derived from C5 precursors with toxicity to invertebrates | Nostoc commune, Calothrix sp. PCC7507 | Natural insecticides or pest repellents | [122] |

| Product name | Manufacturer | Microalgae used | Formulation | Main effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algafert | Biorizon Biotech | Spirulina spp. | Dry powder | Provides macro and micronutrients, promotes chlorophyll synthesis. |

| AgriAlgae | AlgaEnergy | Nannochloropsis spp. | Liquid biostimulant |

Enhances photosynthesis, nutrient uptake, and crop vigor. |

| Spiralagrow | GreenCoast | Arhtrospira spp. | Pellet, granulate |

Improves soil fertility and water retention. |

| Ecotop | Herogra | Ascophyllum nodosum and blend of other microalgae | Liquid biostimulant |

Enhances plant vigor, growth and resilience to abiotic/biotic stress. |

| Kelpak | Kelpak | Ecklonia maxima (macroalga, used in synergy with microalgae) | Liquid biostimulant |

Promotes root and shoot development, stress tolerance. |

| AlgaGrow | Agrinos | Proprietary blend including cyanobacteria | Liquid biostimulant |

Increases nutrient uptake and crop yield. |

| Seasol | Seasol International (Australia) | Blend of seaweed and microalgae extracts | Liquid concentrate |

Broad-spectrum plant tonic. |

| Weed-Max | Trade S.A.E. Company (Egypt) | Cyanobacteria extract in powder phase | Dry powder | Suppress soil-borne fungi and enhance the antagonistic abilities of other bioagents. |

| Oligo-X algal | Arabian Group for Agricultural Service | Blue-green algal extracts in liquid phase | Liquid concentrate |

Suppress soil-borne fungi. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).