1. Introduction

Recent advances in multimodal models, such as LLaMA [

1], Gemma [

2], and Mistral [

3], have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in processing and generating text, images, and other data modalities. However, integrating 3D vision and speech synthesis remains an underexplored area. To bridge this gap, we propose a 3D-to-Speech model that converts 3D images into natural spoken descriptions. Our approach leverages a pipeline of state-of-the-art models: DETR [

4] and Moondream [

5] for understanding 3D images, LLaMA-3.2-1B-Instruct [

1] (fine-tuned with DPO) for generating coherent textual descriptions, and Orpheus-3B-0.1-ft [

6] fine-tuned TTS model for high-quality speech synthesis. The training data for LLaMA were synthetically generated using DeepSeek-V3 0324 [

7] as the chosen data and LLaMA-3.2-1B-Instruct [

1] as the rejected data, ensuring rich and diverse descriptions.

Unlike existing multimodal models that focus primarily on 2D images and text, our system uniquely supports interactive speech-based queries, allowing users to ask questions and receive dynamic spoken responses. This enables a conversational experience with 3D visual data, opening new possibilities for accessibility and human-computer interaction. Our work demonstrates how combining specialized models can overcome the limitations of general-purpose multimodal systems in handling 3D-to-speech conversion.

2. Related Works

Recent advancements in 3D object detection are critical for analyzing 3D images, as seen in our model’s use of DETR and Moondream. Wang et al. [

8] introduced DETR3D, a framework for multicamera 3D object detection, extracting 2D features from multiple camera images and using 3D object queries to index into these features, linking 3D positions to multiview images via camera transformation matrices. This top-down approach outperforms bottom-up methods by avoiding compounding errors from depth prediction, aligning with our image analysis needs. Additionally, a survey by Peng et al. [

9] on deep learning for 3D object detection and tracking in autonomous driving highlights the challenges of sparse point clouds, relevant for our 3D image processing. These works provide a robust foundation for our DETR-based analysis.

For generating textual descriptions from 3D images, our model leverages LLaMA, trained with DPO, which connects to recent works in 3D captioning. Luo et al. [

10] proposed Scalable 3D Captioning with Pretrained Models, an automated approach using pretrained models from image captioning, image-text alignment, and LLMs to consolidate captions from multiple views of a 3D asset, applied to the Objaverse dataset, resulting in 660k 3D-text pairs. Their evaluation with 41k human annotations showed that Cap3D surpasses human-authored descriptions in quality, cost, and speed—an unexpected finding that could enhance our model’s efficiency. This work aligns with our use of LLaMA, suggesting that pretrained models are pivotal for scalable 3D captioning.

The ability of users to interact via speech input, enabling a dynamic conversational experience, connects to advancements in speech-based conversational AI. Xue et al. [

11] provided a review of recent progress, highlighting neural models for dialogue systems, relevant for our interaction feature. Tu et al. [

12] introduced AMIE, an LLM-based system for diagnostic dialogue, using self-play and feedback mechanisms, emphasizing speech interfaces for accessibility, aligning with our conversational design. These works underscore the potential for multimodal, speech-driven interactions, supporting our system’s user engagement.

3. Model Architecture Justification

3.1. Choice of LLaMA over Other LLMs

The decision to use LLaMA-3.2-1B-Instruct [

1] instead of larger or alternative models like Gemma [

2] or Mistral [

3] was driven by three key factors. First, LLaMA’s 1.3 billion parameter architecture strikes an optimal balance between computational efficiency and performance, enabling real-time inference on consumer-grade GPUs while maintaining strong reasoning capabilities [

13]. Second, its instruction-tuned variant demonstrated superior performance in following complex spatial prompts compared to similarly sized models. Third, the model’s open weights and modular architecture facilitated efficient integration with our DPO training framework [

14], allowing targeted adaptation to 3D spatial reasoning without catastrophic forgetting [

15]. This combination of efficiency, task alignment, and adaptability made LLaMA preferable to both larger models (which would exceed our computational constraints) and smaller models (which lacked sufficient reasoning depth).

3.2. Modular Vision Processing over Integrated VLMs

While Vision-Language Models (VLMs) like GPT-4V [

16] or LLaVA [

17] offer end-to-end image understanding, our modular approach—combining DETR [

4], MiDaS [

18], and Moondream [

5]—provides critical advantages for 3D-to-speech conversion. First, explicit depth estimation via MiDaS injects quantifiable 3D spatial relationships (x,y,z) into the language model, enabling geometrically grounded descriptions that VLMs typically lack. Second, decoupling object detection (DETR) from semantic captioning (Moondream) allows specialized optimization—DETR’s transformer architecture achieves state-of-the-art detection accuracy [

19], while Moondream’s small size (1.9B parameters) enables efficient fine-grained captioning. Third, this separation permits transparent error diagnosis; for instance, we can independently verify depth estimates versus object classifications.

4. Main Scheme and Working Principles of the Model

The system is based on a multimodal artificial intelligence model that analyzes visual data to produce meaningful text outputs and then converts these texts into speech responses. It also allows users to interact by asking questions via voice input.

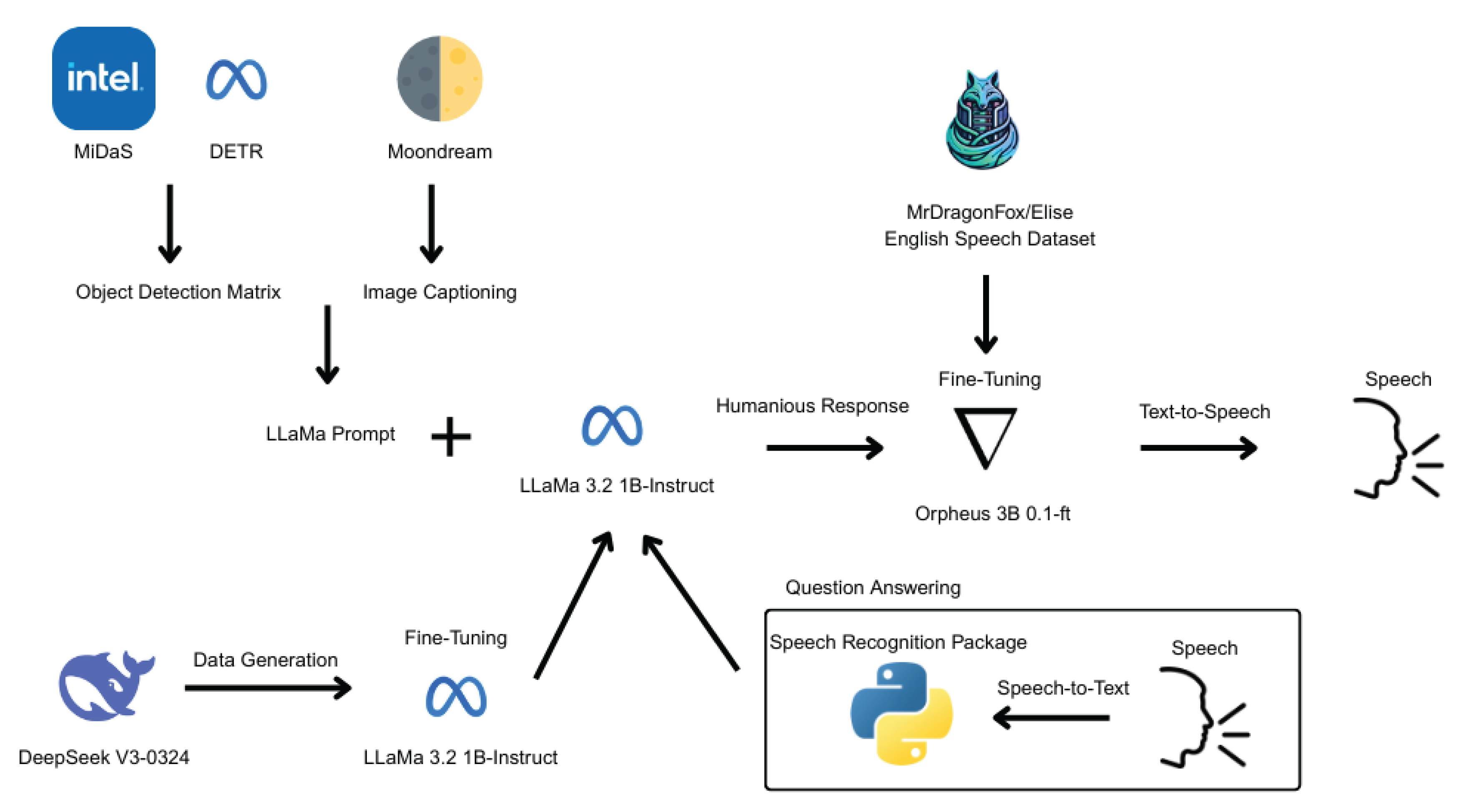

As shown in

Figure 1, the process begins when an image is provided by the user. This image is first processed for object detection using MiDaS [

20] developed by Intel and DETR [

4] developed by Meta. Meanwhile, Moondream [

5] is used to generate a caption that describes the content of the image. The outputs of these modules are combined into a single prompt that can be interpreted by LLaMA-based models.

The constructed prompt is passed to the LLaMA 3.2 1B-Instruct [

1] model, which has been fine-tuned with synthetic data generated by DeepSeek V3-0324 [

7]. This model generates a relevant and coherent response based on the visual content.

This response is then sent to the Orpheus 3B 0.1-ft model [

6], which has been fine-tuned with the MrDragonFox/Elise English speech dataset [

21] for producing more natural and human-like responses. The textual response is converted into speech through a text-to-speech engine.

Additionally, the system supports spoken question answering. The user’s voice is transcribed using a SpeechRecognition package [

22] and transformed into text. This text input is then processed in the same manner, allowing for continuous voice-based interaction between the user and the system.

5. 3D Image Captioning

The first stage of the model, 3D captioning, will process the user’s video or image input from the camera and generate a prompt for LLaMA with DETR, MiDaS and Moondream [

4,

5,

20], following the stages described in

Section 3.

5.1. Object Detection Matrix

The DETR [

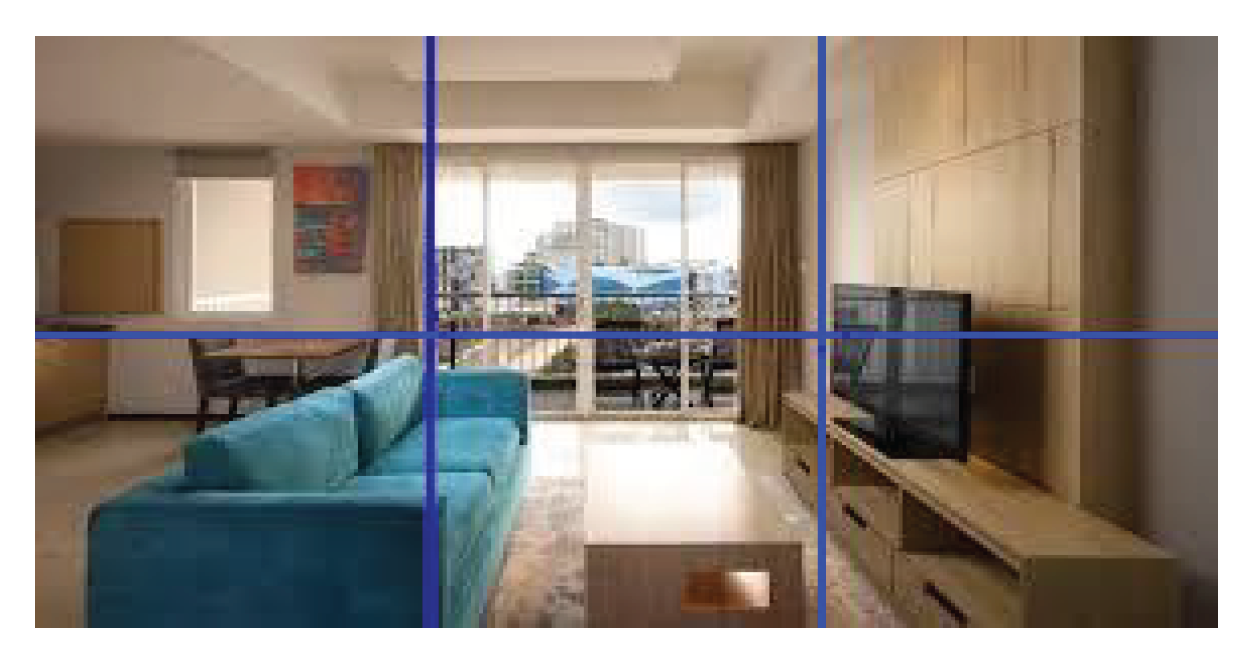

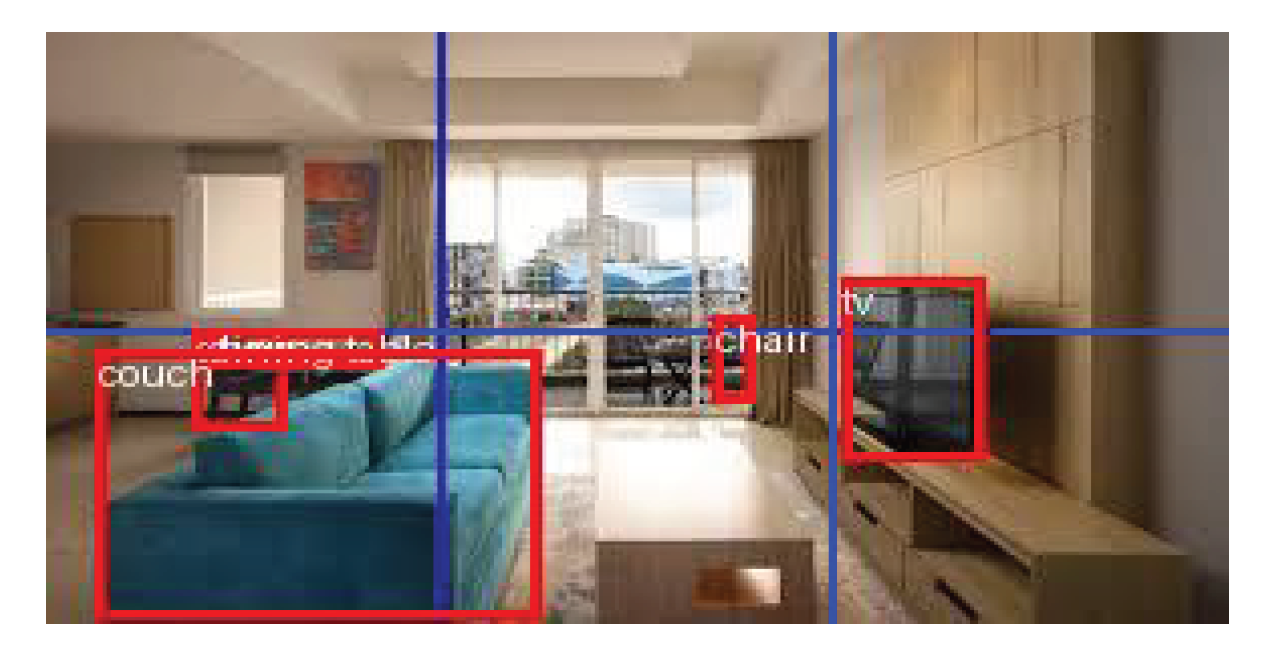

4] can determine how many objects there are in a picture and where they are like

Figure 2. MiDas [

20] can also determine height, length and depth of the objects. But more importantly, it can provide the location of these objects to the LLaMA [

1] model in a way that it can understand as a prompt.

That’s why a mechanism was needed to communicate the location of these objects in the image to the LLaMA model. For this purpose, we divided the image into a grid of 2 rows and 3 columns like

Figure 3. Then we put the 2 pictures on top of each other as in

Figure 4. Finally, we convert this image into an object detection matrix with the output of MiDaS and structure it in a way that the LLaMA model can interpret:

All values are structured to include the object, the probability of matching the object, and its (x, y, z) coordinates. The structure can be summarized as follows:

However, it is a fact that the model cannot predict everything correctly, so objects that do not provide a 90% match as a threshold value are not included in the matrix. If we need to give a more concrete explanation based on

Figure 4, top three values will be empty and bottom three values will be as follows:

5.2. Image Captioning

Moondream [

5] is a vision-language model capable of generating image captions by holistically analyzing a given image. The primary motivation for integrating this model into our system is to move beyond the mere extraction of object coordinates or class labels. Instead, it enables the language model to make semantic inferences based on the visual attributes of objects, their symbolic meanings, and their relative spatial and contextual relationships within the scene.

By producing image-level descriptions, the model captures spatial arrangements, dimensional differences, potential interactions, and contextual dependencies between entities. This facilitates the generation of linguistically rich and contextually grounded textual representations. Consequently, the system acquires a multimodal understanding capability, processing visual information not only at the recognition level but also at the levels of interpretation and reasoning.

5.3. Prompt for LLaMA

Finally, object detection matrix and image caption are combined and a prompt is obtained.

5.4. Mathematical Model Explanations

DETR (DEtection TRansformer):

DETR combines a CNN backbone with a Transformer to detect objects as a set prediction problem. It directly outputs bounding boxes and class labels using bipartite matching loss.

Given an image

I, the CNN encoder produces a feature map

. These features are passed to the Transformer encoder-decoder:

Where:

: class probability for object i

: bounding box coordinates

N: fixed number of object queries

MiDaS (Monocular Depth Estimation):

MiDaS predicts relative depth from a single image using a convolutional vision transformer hybrid.

Given an image

I, it outputs a depth map

D:

Where

is the relative depth value at pixel

.

Moondream (Vision-Language Model):

Moondream generates captions from images using a vision-language model.

Where:

C: Generated caption

: Extracts visual features

Decoder: Generates text tokens based on visual tokens

It models the probability:

The mathematical formulations provided offer a clear understanding of how each model processes the visual data and communicates its outputs. These formalizations also highlight the connections between object detection, depth estimation, and caption generation. This multi-model approach enables a comprehensive and semantically rich understanding of the visual scene.

Moving forward, refining the mathematical integration and improving the individual model components will further enhance the system’s capability to generate more accurate and context-aware descriptions. This opens up new possibilities in multimodal AI systems capable of deeper reasoning and understanding of complex visual inputs.

6. Spatial Model Training

6.1. Data Preparation

To fine-tune the LLaMA-3.2-1B-Instruct model using Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) [

14], we generated a synthetic dataset that pairs prompts derived from 3D image analyses with responses from two language models: DeepSeek-V3-0324 [

7] and LLaMA-3.2-1B-Instruct. [

1] In this dataset, responses from DeepSeek-V3-0324 are designated as the

chosen responses, reflecting higher-quality outputs, while responses from LLaMA-3.2-1B-Instruct, prior to fine-tuning, are designated as the

rejected responses. This structure enables the DPO algorithm to learn preferences that enhance the model’s ability to produce detailed and contextually accurate descriptions.

The data preparation process involved the following steps:

Image Processing: We selected 2000 images from the COCO 2017 training set [

23], which depict various 3D scenes. For each image, we employed the DETR model [

4] for object detection and the Moondream model [

5] for generating detailed descriptions. DETR provided object counts and their 2D spatial locations within a 2×3 grid, while MiDaS estimated relative depth values to derive the

z-coordinates, enabling 3D spatial reasoning. Together, these models generated tuples of

coordinates for detected objects. Moondream produced a natural language description of each image. These components form the foundation of the prompts used in subsequent steps.

-

Prompt Construction: For each image, we constructed a prompt by combining the Moondream-generated image description with the DETR-derived object detection matrix (augmented with MiDaS depth data). The prompt was designed to elicit a detailed description of the depicted place, integrating both the visual narrative and the 3D spatial arrangement of objects. The prompt format is structured as:

Prompt Format:

Image Description: [Description]

This grid-based object detection matrix represents detected objects in different regions of the image. [Matrix]

Describe this place in detail.

System Prompt:

"You are a visual understanding and interpretation assistant. You will receive an input consisting of a natural language description of an image along with a grid-based object detection matrix, which contains object names, counts, and their spatial positions. Your task is to give information and answer questions about places."

-

Response Generation: Using the constructed prompts, we generated responses from two language models:

DeepSeek-V3-0324: This model produced high-quality, contextually rich descriptions, which were labeled as the chosen responses for DPO training.

LLaMA-3.2-1B-Instruct: The pre-fine-tuned version of this model generated baseline descriptions, labeled as the rejected responses.

Both models were configured with a system prompt to act as visual understanding assistants, using parameters max_tokens=1024, temperature=0.7, and top_p=0.95 to ensure consistency in response generation.

-

Dataset Structuring for DPO: For each of the 2000 processed images, a dataset entry was created comprising:

This triplet structure is critical for DPO, enabling the model to learn from pairwise preferences and improve its description quality by aligning with the chosen responses.

The final dataset consists of 1999 samples, each containing a prompt, a chosen response, and a rejected response. The dataset was published on Hugging Face [

24] under the Apache-2.0 License and was subsequently used to fine-tune the LLaMA-3.2-1B-Instruct model via DPO, as described in the

Section 6.2, enhancing its capability to generate detailed and contextually appropriate descriptions of the scenes depicted in the images.

6.2. Fine-Tuning

This model was trained using LoRA and DPO techniques, as detailed in the

Appendix B.1 and

Appendix B.2. These techniques were chosen because they enable efficient fine-tuning of large language models while minimizing computational overhead. LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) reduces the number of trainable parameters, which accelerates convergence and resource usage. DPO (Direct Preference Optimization) directly optimizes the reward margin between chosen and rejected responses, leading to robust preference learning.

The training hyperparameters can be seen in the

Table 1.

6.2.1. Parameter Changes and Training Details

The following tables summarize the key training statistics and parameters.

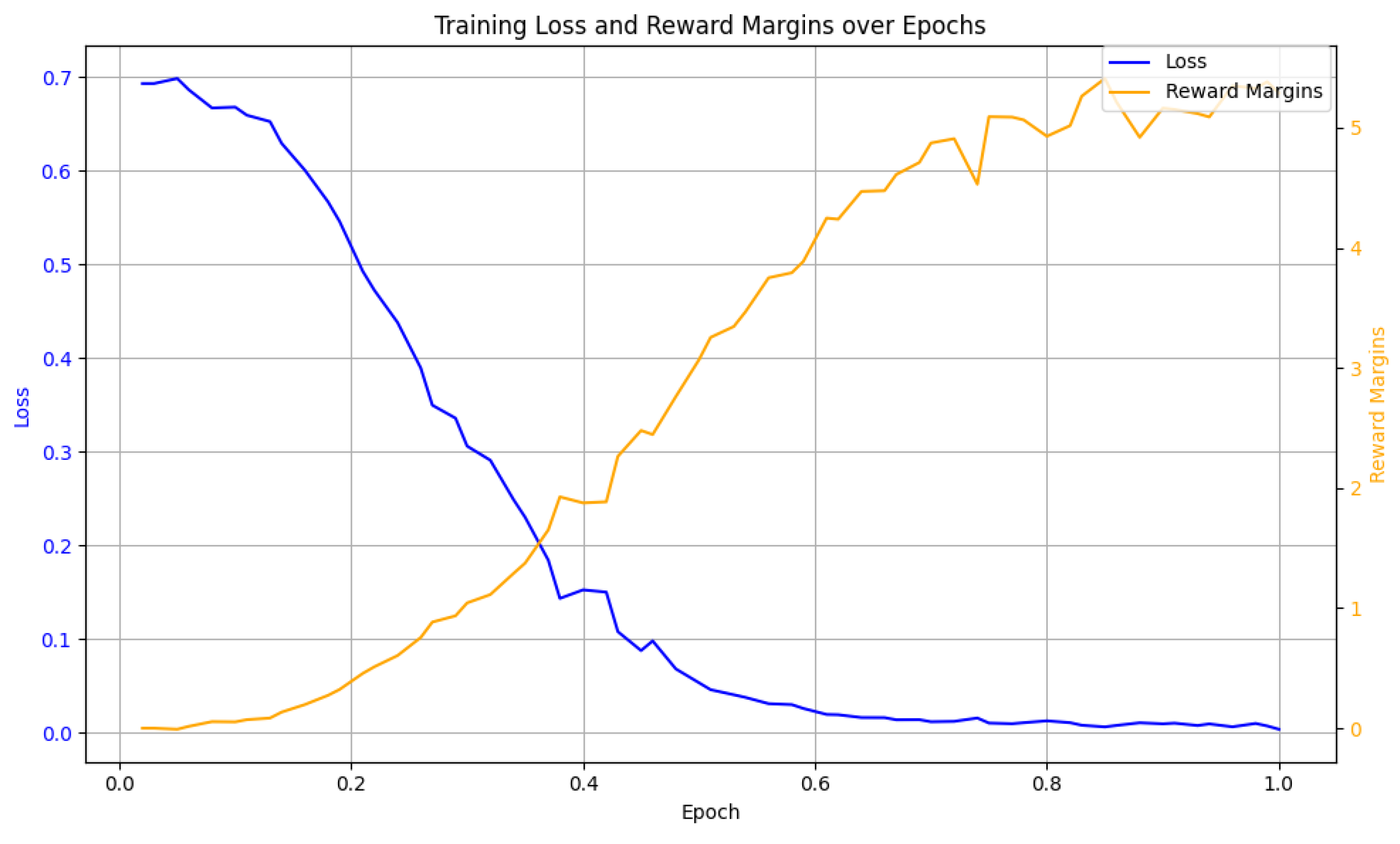

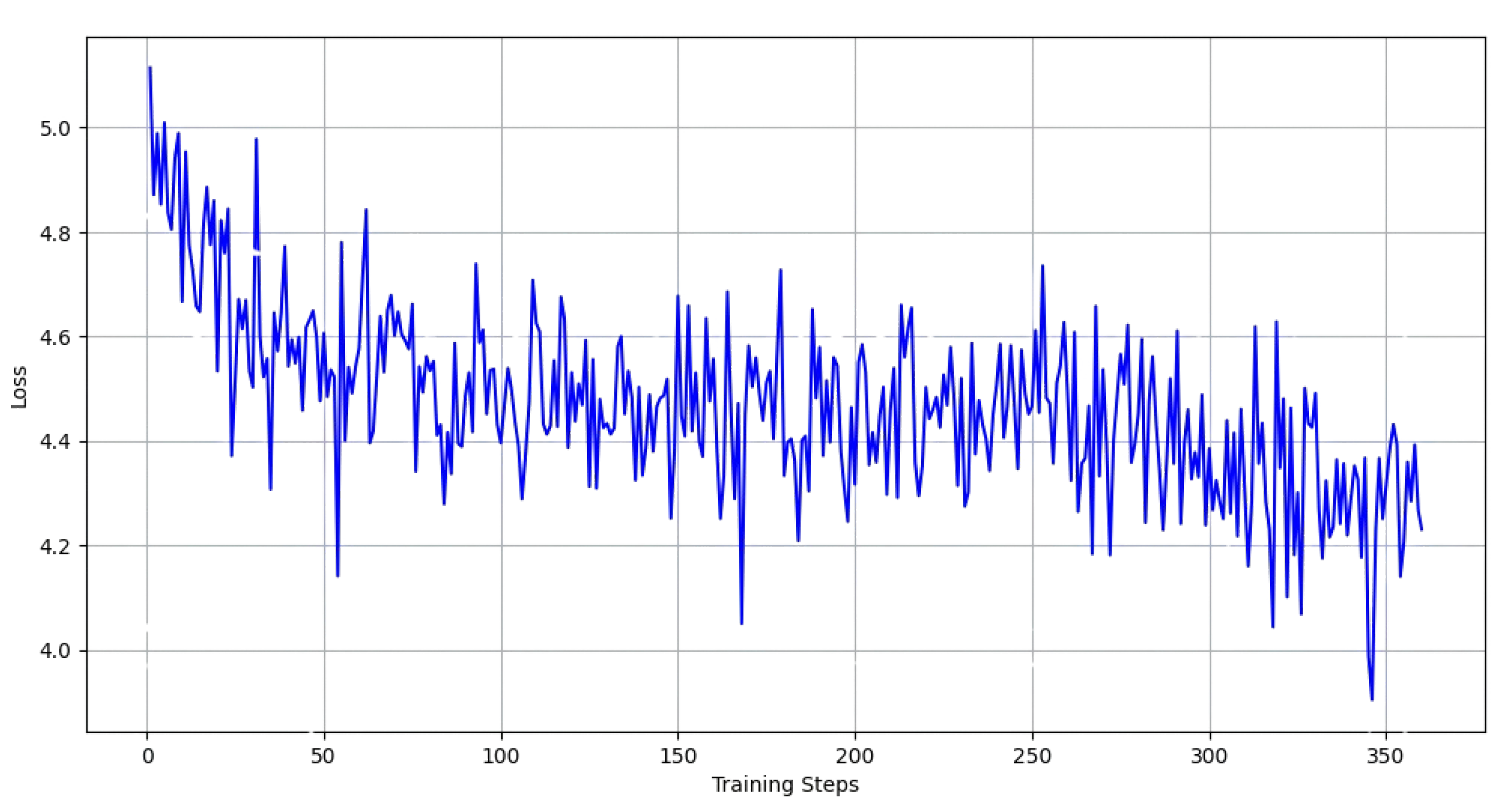

Figure 5.

Training Loss and Reward Margins over Epochs

Figure 5.

Training Loss and Reward Margins over Epochs

Table 2.

Key Training Statistics

Table 2.

Key Training Statistics

| Metric |

Initial |

Final |

| Loss |

0.693 |

0.204 |

| Chosen Reward |

0.0 |

0.441 |

| Rejected Reward |

0.0 |

-4.848 |

| Margin |

0.0 |

5.289 |

| Gradient Norm |

3.54 |

0.076 |

| Learning Rate |

|

0 |

In addition to the parameter changes, the training was conducted on 2 × T4 GPU [

25] using the Axolotl [

26] framework and completed in 1 hour and 40 minutes. The final policy achieved a perfect preference learning performance, with a final accuracy of 1.0 in selecting preferred responses over rejected ones, and the log ratio

increased by

. The complete training process was executed in 63 steps over 1 epoch, demonstrating robust convergence dynamics even with limited computational resources.

7. TTS Model Training

7.1. Justification for Choosing the Orpheus Model

The Orpheus-3B-0.1-ft model [

6] was selected for the Text-to-Speech (TTS) component of our system due to its architectural suitability, capacity for high-quality speech synthesis, and efficient adaptability to our resource constraints. Below, we detail the key factors that informed this choice.

7.1.1. Transformer-Based Architecture

Orpheus is a transformer-based model, which is particularly well-suited for sequential data processing tasks such as speech synthesis. Transformers excel at capturing long-range dependencies through their attention mechanisms, a critical capability for generating coherent and natural-sounding speech sequences [

27]. This architectural advantage positions Orpheus as a strong candidate for TTS compared to traditional models like Tacotron 2, which relies on autoregressive generation [

28], or WaveNet, which demands significant computational resources for raw waveform synthesis [

29].

7.1.2. Multimodal Processing Capabilities

Orpheus’s ability to handle multimodal inputs—jointly modeling text and audio tokens—enhances its versatility within our broader 3D-to-Speech pipeline. By fusing tokenized audio features with text using special tokens to delineate speech boundaries and roles, the model achieves better alignment between linguistic content and acoustic output. This capability is particularly valuable for generating contextually appropriate speech in interactive applications.

7.1.3. Support for Multi-Speaker Synthesis

Orpheus supports multi-speaker text prompts, enabling it to synthesize speech in diverse styles and voices. This feature is crucial for conversational AI systems, where varied and natural-sounding speech enhances user engagement. By adapting the tokenization strategy to the multi-speaker Elise corpus [

21], we ensured that Orpheus could effectively handle different dialogue and narration styles, as detailed in the

Section 7.3.

7.2. Training Techniques

We utilized the Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) [

30] method for efficient fine-tuning of the Orpheus-3B-0.1-ft model. By injecting trainable rank decomposition matrices into key attention layers—including

—LoRA enables the model to learn task-specific representations while mitigating the effects of catastrophic forgetting [

31]. The model was loaded using 4-bit quantization to reduce memory usage and accelerate training, and gradient checkpointing was enabled to further optimize memory efficiency.

The input space of the model was expanded with tokenized audio features extracted using SNAC (Multiscale Neural Audio Codec) [

32], allowing for the joint modeling of both speech and text. These audio features were converted into discrete token sequences and fused with textual tokens to train the model on multimodal inputs. Special tokens were used to indicate the beginning and end of speech, human input, and AI response, facilitating a clear alignment between the modalities.

To enhance training quality, redundant audio frames were programmatically filtered out, and the tokenization strategy was adapted to support multi-speaker text prompts, enabling the model to handle diverse dialogue and narration styles.

7.3. Training Stages

Training was carried out using the Hugging Face Transformers Trainer API [

33]. The dataset used for training was obtained from the

Elise corpus, which contains paired audio-text data in various speaker styles. The audio inputs were processed with the SNAC model and resampled to 24 kHz to match the codec requirements.

7.3.1. Hyperparameters

The following

Table 3 and Table 4 shows the hyperparameters used during the training.

We intentionally set the LoRA [

30] rank to

64 and the corresponding scaling factor to

64, while disabling dropout, to strike an effective balance between model adaptability and stability. By targeting specific projection layers for fine-tuning, this configuration ensures that only selected components undergo optimization, preserving the core knowledge embedded during pretraining. This deliberate choice enables the model to effectively adapt to task-specific requirements while maintaining its generalization capabilities, as further detailed in

Appendix B.1 and supported by established principles of Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA).

7.4. Overview and Performance Analysis

The model was fine-tuned using 2xT4 GPU [

25]. The total training time and parameter size for the model is detailed in

Table 5.

The loss graph for the model is also detailed in

Figure 6.

In conclusion, the graph depicts a typical training process characterized by an initial rapid loss reduction followed by stabilization, suggesting effective learning and convergence.

8. Discussion

8.1. Limitations

This study faced several limitations that provide avenues for future research. One key challenge was the reliance on a complex integration of multiple state-of-the-art models. Combining DETR and MoonDream for image analysis with LLaMA-3.2-1B-Instruct for text generation and Orpheus-3B-0.1-ft for speech synthesis introduced potential error propagation. In particular, misalignments between the models—for instance, discrepancies between image features extracted by DETR and the semantic interpretations provided by MoonDream—could lead to less coherent spoken descriptions. The chain-of-pipeline nature of our system means that improvements in any single component might not fully translate to better overall performance, emphasizing the need for further work on robust integration strategies.

Another limitation stems from the synthetic nature of our training data for LLaMA. Since the training samples were generated using the DeepSeek-V3-0324 model and the base model itself for the DPO Reinforcement Learning technique, there is an inherent risk that these data may not capture the full diversity and subtleties of real-world 3D images and natural language interactions. This constraint could limit the generalizability of our model in more varied or unexpected scenarios, where nuanced descriptions and context-specific speech synthesis are required.

Moreover, the dynamic conversational component—where users interact with the system via speech input—introduced additional challenges. Variations in accent, ambient noise, and user speaking styles might affect both the accuracy of input interpretation and the quality of the generated responses. Although our system was designed to facilitate interactive dialogue, these factors may have introduced variability that limits the overall consistency of the model’s performance in real-world applications.

Overall, these limitations highlight the trade-offs between integrating advanced components, managing synthetic versus real-world training data, and ensuring a robust conversational interface. Addressing these issues through improved model harmonization, more diverse and representative training datasets, and enhanced speech processing techniques will be critical for future advancements in 3D-to-Speech systems.

8.2. Advantages

Our approach offers several distinct advantages that contribute to the advancement of 3D-to-Speech systems. First, the integration of multiple state-of-the-art models—DETR and MoonDream for image analysis, LLaMA-3.2-1B-Instruct for text generation, and Orpheus-3B-0.1-ft for speech synthesis—enables a comprehensive processing pipeline. This modular design not only leverages the strengths of each individual component but also facilitates targeted improvements, as enhancements in any single model can incrementally boost overall system performance.

Another notable advantage is the innovative use of synthetic training data generated using the DeepSeek-V3-0324 model and DPO Reinforcement Learning technique. This approach allows for the creation of large-scale, high-quality datasets that are specifically tailored to bridge the gap between visual inputs and natural language outputs. As a result, our system is capable of producing detailed and contextually rich spoken descriptions of 3D images, which can be particularly valuable in applications such as accessibility technologies and interactive media.

Furthermore, the inclusion of a dynamic conversational interface, which permits users to interact with the system through speech, adds an extra layer of flexibility and usability. This interactive feature transforms the traditional one-way output into a dialogue-driven experience, allowing users to pose follow-up questions and engage with the generated content. Such responsiveness not only enhances user satisfaction but also opens new avenues for real-time, context-aware applications in educational, entertainment, and assistive domains.

Overall, the strengths of our system lie in its modular integration of advanced models, the strategic use of synthetic data for training, and the incorporation of a conversational user interface. These advantages collectively position our 3D-to-Speech model as a significant step forward in the development of multimodal AI systems.

9. Conclusion

In this paper, we introduced EchoLLaMA, a multimodal AI system that transforms 3D visual data into natural spoken descriptions while enabling interactive dialogue through speech input. By integrating specialized models for 3D image analysis—DETR for object localization, MiDaS for monocular depth estimation, and MoonDream for holistic captioning—alongside LLaMA-3.2-1B-Instruct (fine-tuned with DPO) for text generation and Orpheus-3B-0.1-ft for speech synthesis, our pipeline addresses the underexplored challenge of bridging 3D vision with conversational speech. The system’s modular design leverages the strengths of each component: DETR provides precise spatial object detection, MiDaS enriches spatial understanding with depth perception, MoonDream generates semantic captions, and LLaMA synthesizes contextually rich descriptions, which are then vocalized by Orpheus. The inclusion of dynamic speech-based interaction further distinguishes our work, allowing users to engage in real-time dialogue with the system.

Our experiments demonstrate that combining synthetic training data—generated via DeepSeek-V3-0324 and refined through DPO—with efficient fine-tuning techniques like LoRA enables robust performance while minimizing computational costs. MiDaS’s role in constructing depth-aware object detection matrices proved critical for translating 3D spatial relationships into interpretable prompts for LLaMA, ensuring that the generated descriptions account for dimensional and positional context. This approach not only improves the quality of generated descriptions but also ensures scalability across diverse 3D scenes. The system’s ability to interpret spatial relationships and produce coherent spoken outputs has significant implications for accessibility, particularly in assisting visually impaired users, as well as applications in education, robotics, and interactive media.

Looking ahead, future work will focus on enhancing model integration to reduce error propagation (e.g., refining alignment between MiDaS’s depth maps and DETR’s object detection outputs), expanding the diversity of training data to improve generalization, and refining the speech interface for robustness against real-world acoustic variability. Extending the framework to support dynamic 3D environments, such as video streams, represents another promising direction. By advancing the synergy between 3D vision (via DETR, MiDaS, and MoonDream), language, and speech, EchoLLaMA lays a foundation for more intuitive and inclusive human-AI interaction paradigms.

To facilitate further research and development in this field, we have published our models and dataset on Hugging Face [

24]. They can be accessed using the following links:

The dataset can be accessed here:

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Appendix A. Generation Examples

Table A1.

Example generations using the model

Table A1.

Example generations using the model

| Input |

Generated Prompt |

Response |

|

Image Description: The image features a calico cat sitting on the hood of a black car. The cat is comfortably perched on the car’s roof, with its head resting on the hood. The car is parked in front of a house, and there is a potted plant nearby. The scene captures a peaceful moment between the cat and its surroundings.

This grid-based object detection matrix represents detected objects in different regions of the image.

|

Based on the provided grid-based object detection matrix, here’s a summary of the image:

A calico cat is sitting comfortably on the hood of a black car, with its head resting on the hood. The cat is positioned in a serene and peaceful manner, as if enjoying the moment. The car is parked in front of a house, with a potted plant nearby. This scene captures a lovely domestic moment between the cat and its surroundings. |

|

Image Description: The image features a computer monitor with a silver Apple logo on the front, sitting on a wooden desk. Next to the monitor, there is a cell phone with a blue screen, placed on the desk. The cell phone appears to be turned on, as it is illuminated.

The desk is also adorned with several books scattered around, with some placed near the monitor and others on the desk surface. The books vary in size and are positioned at different angles, creating a cozy and inviting atmosphere.

This grid-based object detection matrix represents detected objects in different regions of the image.

|

Based on the provided image description and object detection matrix, here’s a summary of the scene:

A computer monitor with a silver Apple logo on the front sits on a wooden desk. To the left of the monitor, a cell phone with a blue screen is placed, illuminated and turned on. The desk is adorned with several books, scattered around and placed near the monitor and desk surface. The books vary in size and are positioned at different angles, creating a cozy and inviting atmosphere. The overall scene appears to be a comfortable and modern workspace, with the Apple logo and cell phone serving as a focal point. |

Appendix B. Detailed Training Techniques

Appendix B.1. LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation)

Weight Update: Instead of updating the full weight matrix W, LoRA introduces a low-rank decomposition for efficient adaptation.

Low-Rank Decomposition:

where

,

, and

, significantly reducing trainable parameters.

Modified Forward Pass: The adapted weight matrix is used as follows:

where

x is the input, and

is an activation function.

Gradient Update: During backpropagation, only

A and

B are updated:

ensuring efficient training while keeping

W frozen.

Optimization Goal: LoRA aims to maintain model performance while significantly reducing memory and computation costs, making it ideal for fine-tuning large models efficiently. [

30]

Appendix B.2. DPO (Direct Policy Optimization)

Reference Policy: Defines the conditional probability distribution of the output y given an input state x.

Reward Function: Determines the score associated with a particular state

x and response

y. It is formulated as follows:

where

is a scaling parameter that regulates the influence of the evaluation function on the generated outputs.

Optimization Objective: The primary aim is to refine the model according to the following formulation to ensure it aligns with human judgments:

This equation is designed to encourage the model to generate outputs that better reflect human evaluations. The optimization process involves minimizing a corresponding loss function, thereby enhancing alignment with human expectations. [

14]

References

- et al., A.G. The Llama 3 Herd of Models, 2024, [arXiv:cs.AI/2407.21783].

- Team, G. Gemma: Open Models Based on Gemini Research and Technology, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2403.08295].

- Jiang, A.Q.; Sablayrolles, A.; Mensch, A.; Bamford, C.; Chaplot, D.S.; de las Casas, D.; Bressand, F.; Lengyel, G.; Lample, G.; Saulnier, L.; et al. Mistral 7B, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CL/2310.06825].

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers, 2020, [arXiv:cs.CV/2005.12872].

- Korrapati, V. moondream2 (Revision 92d3d73), 2024. https://doi.org/10.57967/hf/3219.

- CanopyLabs. Orpheus 3B 0.1-ft. https://huggingface.co/canopylabs/orpheus-3b-0.1-ft, 2024. Available on Hugging Face.

- DeepSeek-AI. DeepSeek-V3 Technical Report, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2412.19437].

- Wang, Y.; Guizilini, V.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Solomon, J. DETR3D: 3D Object Detection from Multi-view Images via 3D-to-2D Queries, 2021, [arXiv:cs.CV/2110.06922].

- Peng, S.; Genova, K.; Jiang, C.M.; Tagliasacchi, A.; Pollefeys, M.; Funkhouser, T. OpenScene: 3D Scene Understanding with Open Vocabularies, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CV/2211.15654].

- Luo, T.; Rockwell, C.; Lee, H.; Johnson, J. Scalable 3D Captioning with Pretrained Models, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CV/2306.07279].

- Xue, Z.; Li, R.; Li, M. Recent Progress in Conversational AI, 2022, [arXiv:cs.CL/2204.09719].

- Tu, T.; Palepu, A.; Schaekermann, M.; Saab, K.; Freyberg, J.; Tanno, R.; Wang, A.; Li, B.; Amin, M.; Tomasev, N.; et al. Towards Conversational Diagnostic AI, 2024, [arXiv:cs.AI/2401.05654].

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CL/2302.13971].

- Rafailov, R.; Sharma, A.; Mitchell, E.; Ermon, S.; Manning, C.D.; Finn, C. Direct Preference Optimization: Your Language Model is Secretly a Reward Model, 2024, [arXiv:cs.LG/2305.18290].

- Kirkpatrick, J.; Pascanu, R.; Rabinowitz, N.; Veness, J.; Desjardins, G.; Rusu, A.A.; Milan, K.; Quan, J.; Ramalho, T.; Grabska-Barwinska, A.; et al. Overcoming catastrophic forgetting in neural networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114, 3521–3526. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1611835114.

- OpenAI.; Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; et al. GPT-4 Technical Report, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2303.08774].

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Wu, Q.; Lee, Y.J. Visual Instruction Tuning, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CV/2304.08485].

- Ranftl, R.; Lasinger, K.; Hafner, D.; Schindler, K.; Koltun, V. Towards Robust Monocular Depth Estimation: Mixing Datasets for Zero-shot Cross-dataset Transfer, 2020, [arXiv:cs.CV/1907.01341].

- Zhu, X.; Su, W.; Lu, L.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Dai, J. Deformable DETR: Deformable Transformers for End-to-End Object Detection, 2021, [arXiv:cs.CV/2010.04159].

- Ranftl, R.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Koltun, V. Vision Transformers for Dense Prediction. CoRR 2021, abs/2103.13413, [2103.13413].

- MrDragonFox. Elise Dataset. https://huggingface.co/datasets/MrDragonFox/Elise, 2025.

- Zhang, A. Speech Recognition (Version 3.11) [Software]. https://github.com/Uberi/speech_recognition#readme, 2017. Available from GitHub.

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Bourdev, L.; Girshick, R.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Zitnick, C.L.; Dollár, P. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context, 2015, [arXiv:cs.CV/1405.0312].

- Hugging Face. Hugging Face. The ai community building the future. the platform where the machine learning community collaborates on models, datasets, and applications, 2024.

- .

- Lian, W. axolotl, 2024.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CL/1706.03762].

- Shen, J.; Pang, R.; Weiss, R.J.; Schuster, M.; Jaitly, N.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Skerry-Ryan, R.; et al. Natural TTS Synthesis by Conditioning WaveNet on Mel Spectrogram Predictions, 2018, [arXiv:cs.CL/1712.05884].

- van den Oord, A.; Dieleman, S.; Zen, H.; Simonyan, K.; Vinyals, O.; Graves, A.; Kalchbrenner, N.; Senior, A.; Kavukcuoglu, K. WaveNet: A Generative Model for Raw Audio, 2016, [arXiv:cs.SD/1609.03499].

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models, 2021, [arXiv:cs.CL/2106.09685].

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Mirza, M.; Xiao, D.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. An Empirical Investigation of Catastrophic Forgetting in Gradient-Based Neural Networks, 2015, [arXiv:stat.ML/1312.6211].

- Siuzdak, H.; Grötschla, F.; Lanzendörfer, L.A. SNAC: Multi-Scale Neural Audio Codec, 2024, [arXiv:cs.SD/2410.14411].

- Wolf, T.; Debut, L.; Sanh, V.; Chaumond, J.; Delangue, C.; Moi, A.; Cistac, P.; Rault, T.; Louf, R.; Funtowicz, M.; et al. Transformers: State-of-the-Art Natural Language Processing, 2020. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2020.emnlp-demos.6.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).