1. Introduction

Currently, against the backdrop of increasing urbanization, the study of urban language varieties has emerged as a promising field of linguistic research [Petrov, 2023: 5]; [Yakovleva, 2019: 420]. Due to various sociocultural factors, the speech of residents in Russian cities tends toward universalization [Kuznetsov, 2012: 91]. This study represents an initial attempt to describe a newly identified phonetic phenomenon in the speech of Saratov city dwellers, with Saratov selected as the region of focus. Despite a growing body of research on regional linguistic features [Bubnova, 2025: 224], there remains a notable lack of scholarly attention to the Volga region as an area where the phonetic standard norm is preserved.

The question of the norm in contemporary Russian literary language encompasses both regional and temporal dimensions. As T.M. Nikolaeva emphasizes, the classification of phonetic phenomena as regional or archaic remains unresolved [Nikolaeva, 2013: 144].

The relevance of this research is founded upon the importance of investigating changes in assimilatory processes within consonant clusters under the influence of sociolinguistic factors, alongside the necessity to identify the underlying causes of language change.

V.G. Kostomarov asserted that “the pan-Russian pronunciation norm had solidified into a single standardized norm by the mid-20th century, centered in Moscow” [Kostomarov, 2015: 3]. Many scholars associate the palatal assimilation of consonants particularly with the Moscow region, highlighting that “the most problematic issue is the assimilative palatalization of consonants” [Prokhorova, 2014: 163].

In 1968, D.N. Ushakov did not examine in detail the palatal assimilation of all labial consonants preceding a soft velar, addressing only the labiodental case ([ф] vs. [ф’]) [Shatin, 2022: 29]. He further noted that, within the Moscow standard, “the dental consonants д, т, с, з, н, as well as р and ф, are typically pronounced softly before soft consonants: баньщик, дверь, две, деньщик, дефки (девки)” [Ushakov, 2025: 48]. Notably, Ushakov omits mention of palatal assimilation involving labials like [м] and [п], which may indicate that by that time, such assimilation had already been lost.

Accordingly, the 1989 Orthoepic Dictionary edited by R.I. Avanesov does not record palatal assimilation of labials before velars. Moreover, assimilation in cases such as labiodentals preceding soft velars (e.g., “девки”) is also unrecorded [Avanesov, 1989: 115]. At the same time, variants of palatal assimilation involving dentals—both plosives and fricatives—before labials continue to be documented (e.g., две, дверь, зверь, изменить) [Avanesov, 1989: 113, 171, 180].

In M.L. Kalenchuk’s 2017 Large Orthoepic Dictionary of the Russian Language [Kalenchuk, 2017], palatal assimilation of labials before velars reappears. This dictionary categorizes consonant clusters into contemporary, declining (“старш.”), and obsolete (“устар.”) usage, thereby introducing sociolinguistic causality linked to speaker age.

T.M. Nikolaeva draws attention to the intersection of regional and temporal features, arguing that “the differences between the ‘older’ and ‘younger’ generations are not always age-related. <…> It is plausible that pronunciation differences (mostly concerning consonant clusters) between older and younger speakers are regional rather than age-dependent” [Nikolaeva, 2013: 147–148].

Thus, while phonetic norms evolved within Moscow and Saint Petersburg, speakers from other cities may preserve phonetic phenomena typical of the early to mid-20th century literary language norm.

Another driver of language change may be the pursuit of a “prestigious” linguistic form, the command of which “is determined, on one hand, by the highest social esteem afforded to the standard (literary) language relative to other language variants, and on the other hand, by speakers’ self-assessment” [SST, 2006: 172].

Prestige is often expressed through linguistic markers. However, not all linguistic features or deviations from the standard are socially marked as prestigious or non-prestigious. Palatal assimilation of labials before velars in Saratov speech represents one such phenomenon lacking a prestige marker.

Furthermore, it remains unclear how to classify this deviation from current orthoepic norms. It likely cannot be attributed to a dialectal feature since similar phenomena occur in the CRLL and are documented in dictionaries. Nor does it correspond to the definition of a regiolect—that is, “a specific spoken form that has lost many archaic dialectal traits and developed new characteristics” [Erofeeva, 2020: 303]. Therefore, these processes may be best conceptualized as parallel tendencies operating within the broader linguistic norm.

The objective of this study is to describe the characteristics of consonant assimilation in the speech of native Russian speakers in Saratov, juxtaposed with the orthoepic norm of the CRLL, with consideration of sociolinguistic parameters.

The subject of investigation comprises the contemporary phonetic features observed in the speech of Saratov residents. The research focus centers on consonant clusters exhibiting palatal assimilation.

The novelty of this study lies in its systematic approach to describing phonetic phenomena in Saratov speech as an instance of language norm variation among Volga region inhabitants, embedded within a sociolinguistic context.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in Saratov in 2025.

The focus group included 17 native Saratov speakers aged 30 to 80, comprising 13 females and 4 males. Participants represented diverse social statuses (e.g., salespersons, retirees, professors, students). Speech samples were collected in both formal and informal settings.

The research corpus consisted of 60 examples of consonant pairs exhibiting palatal assimilation, alongside control consonant pairs.

Two orthoepic dictionaries were utilized as referential pronunciation norms:

1. Orthoepic Dictionary of the Russian Language (1989), edited by R.I. Avanesov (hereafter referred to as Avanesov’s Dictionary).

2. Large Orthoepic Dictionary of the Russian Language (2017), by M.L. Kalenchuk et al. (hereafter Kalenchuk’s Dictionary).

These dictionaries were chosen due to their comprehensive coverage of the Russian orthoepic norm.

Research methods included the sociolinguistic technique of participant-unaware observation, alongside general scientific methods of comparison and systematization.

In the initial phase, the study applied the participant-unaware observation method first described by W. Labov and previously tested in bilingual contexts [Solovyeva, 2022: 56]; this approach helps circumvent the “observer’s paradox” by eliciting authentic speech. The investigation focused on palatal assimilation within the following consonantal combinations:

- Labial before velar [м’к’, п’к’];

- Labiodental before velar [ф’к’];

- Labiodental before dental plosive [ф’т’];

- Dental fricative and dental plosive before labiodental [з’д’в’];

- Dental plosive before labiodental [д’в’];

- Dental fricative before labial [з’м’, с’п’, с’м’];

- Dental fricative before labiodental [з’в’], [с’в’];

- Dental plosive before labial [д’м’].

Control pairs selected were consonant combinations that never exhibit assimilation:

- Alveolar before velar [рк];

- Dental plosive before velar [тк].

In the second phase, these observed results were compared against data from the Avanesov and Kalenchuk orthoepic dictionaries.

2.1. Advantages and Limitations of the Chosen Method

Since participants are unaware of being observed, the participant-unaware observation method enables the capture of the most authentic phonetic features. However, this method does not guarantee a representative sample, potentially diminishing the generalizability of findings. Nonetheless, its use in the preliminary stage of the study is considered adequate.

2.2. Ethical Considerations

The research procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee of the Pushkin State Institute of the Russian Language and adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and its subsequent amendments. Measures were taken to ensure confidentiality and anonymity of the speakers’ data. No personal identifying information was collected or published. Given the unobtrusive nature of the observation method, care was taken to minimize any potential discomfort or influence on participant behavior.

3. Results

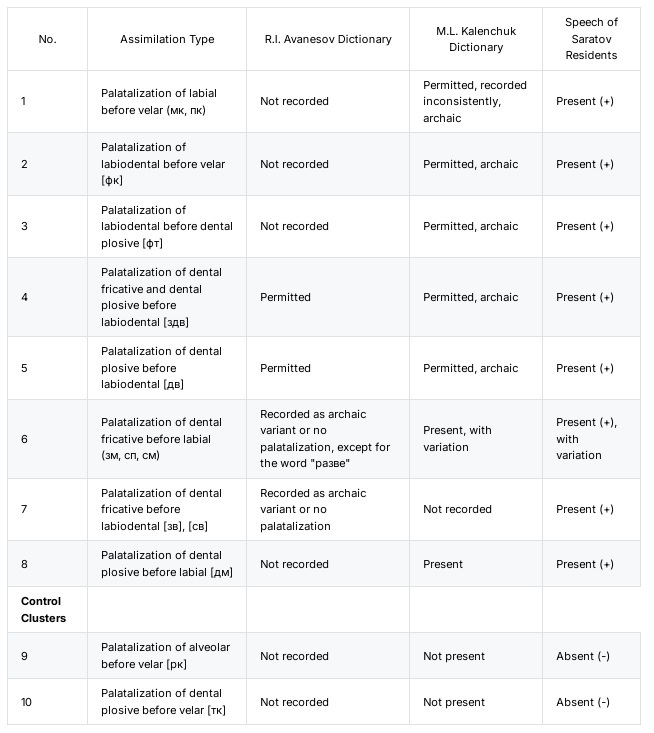

Based on the analysis, a table was compiled comparing the presence of palatal assimilation in dictionaries with its occurrence in Saratov speech.

The table demonstrates that in the speech of Saratov residents, there is a consistent regressive assimilation of palatalization affecting labial and labiodental consonants preceding a soft velar consonant, regardless of the speaker’s gender or age. This type of assimilation appears uninfluenced by the formality of the speech context. In contrast, cases of assimilation involving dental consonants before labial and labiodental consonants exhibit variability. Specifically, fluctuations in dental assimilation are attested in both dictionaries, whereas fluctuations involving labial consonants are documented only in M.L. Kalenchuk’s dictionary.

That is, the palatal assimilation of labials before velars either vanished (according to the dictionary edited by R.I. Avanesov) or is marginal within the literary phonetic norm (per M.L. Kalenchuk’s dictionary), while in Saratov speech, this assimilation remains central to active usage. These combinations are in complementary distribution, which does not foster the emergence of variation. Variation in the palatal assimilation of dentals occurs both in the literary language and in Saratov speech. In the speech of Saratov speakers, the absence of assimilation may also correlate with speech formality. For example, an 80-year-old speaker demonstrated no dental-to-labial assimilation in a formal setting ([разм’эр]), whereas in informal interaction, assimilation was present ([з’д’в’инь’м п’ьр’ирыф]). Thus, explaining linguistic shifts necessitates accounting for the phenomenon of multifactoriality [Filippova, 2021: 182].

4. Discussion

Phonetic dictionaries of the Contemporary Russian Literary Language (CRLL) also raise questions regarding the direction of language change dynamics within the phonetic norm. Specifically, it remains unclear why the 1989 dictionary omitted the archaic pronunciation, whereas the 2017 edition reintroduced and recorded it explicitly as outdated.

Meanwhile, the loss of palatal assimilation in the CRLL, according to the dictionaries, continues to occur to this day.

This is particularly evident in words featuring dental fricatives before front lingual consonants (e.g., если) and dental fricatives before labiodental consonants (e.g., разве). For instance, R.I. Avanesov’s dictionary notes a palatalized norm in если, whereas M.L. Kalenchuk’s later work presents a variant without palatalization.

Against this background of variation in the CRLL, the speech of native speakers from Saratov also exhibits occurrences of the hard [c] as in [jэсл’и]. This lone example was recorded during a lecturer’s oral presentation. Thus, assimilation phenomena can, in some cases, be explained by register shifts, which rather suggest the regional and/or stylistic nature of the process.

On this basis, the following hypothesis may be advanced: palatal assimilation of consonants historically disappeared in the CRLL, while in Saratov this phenomenon persisted. The pronunciation norm with assimilation was not perceived as a marker of “non-prestigious” speech, since it was once associated with the “prestige” of the literary language and, accordingly, lacked negative social connotations, allowing it to persist to the present day.

It is likely that, through language diffusion and extralinguistic factors, this pronunciation gradually spread back into the CRLL; however, among language norm specialists, it came to be associated not with regionalism, but with the speech of older generations of literary language speakers, given that it used to be part of the older phonetic norm.

5. Conclusions

Therefore, in the speech of Saratov speakers, palatalization of labial or labiodental consonants preceding a soft velar is neither archaic nor stylistically, grammatically, or situationally conditioned. This phenomenon systematically extends across the lexicon and does not depend on the degree of word nativeness [траф’к’ь, диаграм’к’ь, пъдыэф’к’ь].

This is corroborated by examples from both colloquial and public speech across different genders and age groups. Their speech, due to its association with social “prestige” (or the absence of negative social coloring), ensures the retention of certain features of the older phonetic norm concerning palatal assimilation.

In clusters displaying variation (dental before velar and dental before front lingual consonants), the choice between hard and soft consonants may be influenced by the formality of the social context.

Against a general trend toward the loss of palatal assimilation in several literary language clusters, the preservation in Saratov of a unique, consistent, and systematic labial-velar assimilation raises important questions about the dynamics and underlying causes of language change within the phonetic norm of contemporary Russian.

References

- Bubnova, N. V. (2025). “So many golden lights on the streets of Saratov…”: Review of the 22nd International Scientific Conference “Onomastics of the Volga Region.” Philology and Man, (1), 224–228.

- Erofeeva, E. V., & Erofeeva, T. I. (2020). Social variation in regiolect. Philological Notes, (18), 301–313. [CrossRef]

- Kalenchuk, M. L., Kasatkin, L. L., & Kasatkina, R. F. (n.d.). Large Orthoepic Dictionary of the Russian Language. Gramota.ru. Retrieved from https://gramota.ru/poisk?Query=скoбка&mode=slovari&dicts%5B%5D=49.

- Kostomarov, V. G. (2015). The language of the present moment: The concept of correctness. In Russian Speech, 122–126.

- Kuznetsov, V. O. (2012). Types of idiolects in a modern city (based on the linguistic situation in Bryansk). Bulletin of Moscow University. Series 9. Philology, (2), 90–98.

- Nikolaeva, T. M., Kalenchuk, M. L., Kasatkin, L. L., & Kasatkina, R. F. (2013). Large Orthoepic Dictionary of the Russian Language. Literary pronunciation and stress in the early 21st century: Norm and its variants. Issues of Linguistics, (4), 144–148.

- Petrov, A. V., Timofeeva, N. Yu., & Chepurina, I. V. (2023). Urban speech as an object of linguistic research: Oral and written varieties. Vestnik of the Baltic Federal University named after I. Kant. Series: Philology, Pedagogy, Psychology, (1), 5–15.

- Prokhorova, I. O. (2014). “The knight of Russian orthoepy”: On the 140th anniversary of the birth of D. N. Ushakov. RUDN Journal of Education. Languages and Specialties Series, (1), 161–165.

- Solovyeva, A. A. (2022). Etiquette expressions in bilingualism: A sociolinguistic analysis. Moscow.

- Ushakov, D. N. (1968) Moscow pronunciation. Russkaya Rech. Retrieved from https://russkayarech.ru/ru/archive/1968-2/43-49.

- Filippova, I. N. (2021). Explicit phonology errors in dubbed film translation. Bulletin of Moscow University. Series 22. Translation Theory, (4), 179–193.

- Shatin, V. Yu. (2022). On comparative pairs of labial phonemes in Kostroma and Poshekhonye dialects of the 17th century and their subsequent fate. Bulletin of Moscow University. Series 9. Philology, (4), 29–38.

- Yakovleva, E. A. (2019). Linguistic urban studies: Achievements, problems, prospects (based on the study of the language of multiethnic Ufa). Russian Humanitarian Journal, (6), 419–434.

-

Large Orthoepic Dictionary (1989) (R. I. Avanesov, Ed.). Moscow.

-

Sociolinguistic Terms Dictionary. (2006). Institute of Linguistics RAS. Retrieved from https://iling-ran.ru/library/sociolingva/slovar/sociolinguistics_dictionary.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).