Background

“Adolescent girls are a powerful force for global change. With the right support at the right time, they can help deliver on the Sustainable Development Goals and reshape our world,” said UNICEF Executive Director Catherine Russell.

However, a particularly significant yet underreported issue is adolescent endometriosis; it often manifests distinct clinical characteristics such as severe dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, or gastrointestinal symptoms, overlapping with those experienced in a range of gynaecological and gastrointestinal conditions, and these symptoms are often normalized or dismissed as typical period pain. In low and middle income countries most of the women do not get the needed right support on the time (Tragantzopoulou, 2024).

Endometriosis, a chronic gynaecological condition affecting an estimated 10% of women and individuals assigned female at birth, is characterised by the growth of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus, leading to symptoms such as dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, infertility, low-mood and systemic inflammatory responses (Smolarz et al, 2021). While its impact on adult populations has been increasingly acknowledged, adolescence endometriosis remains underdiagnosed and undertreated despite evidence suggesting that the onset of symptoms often begins in adolescence (Polak et al., 2013)

Life Course of Endometriosis

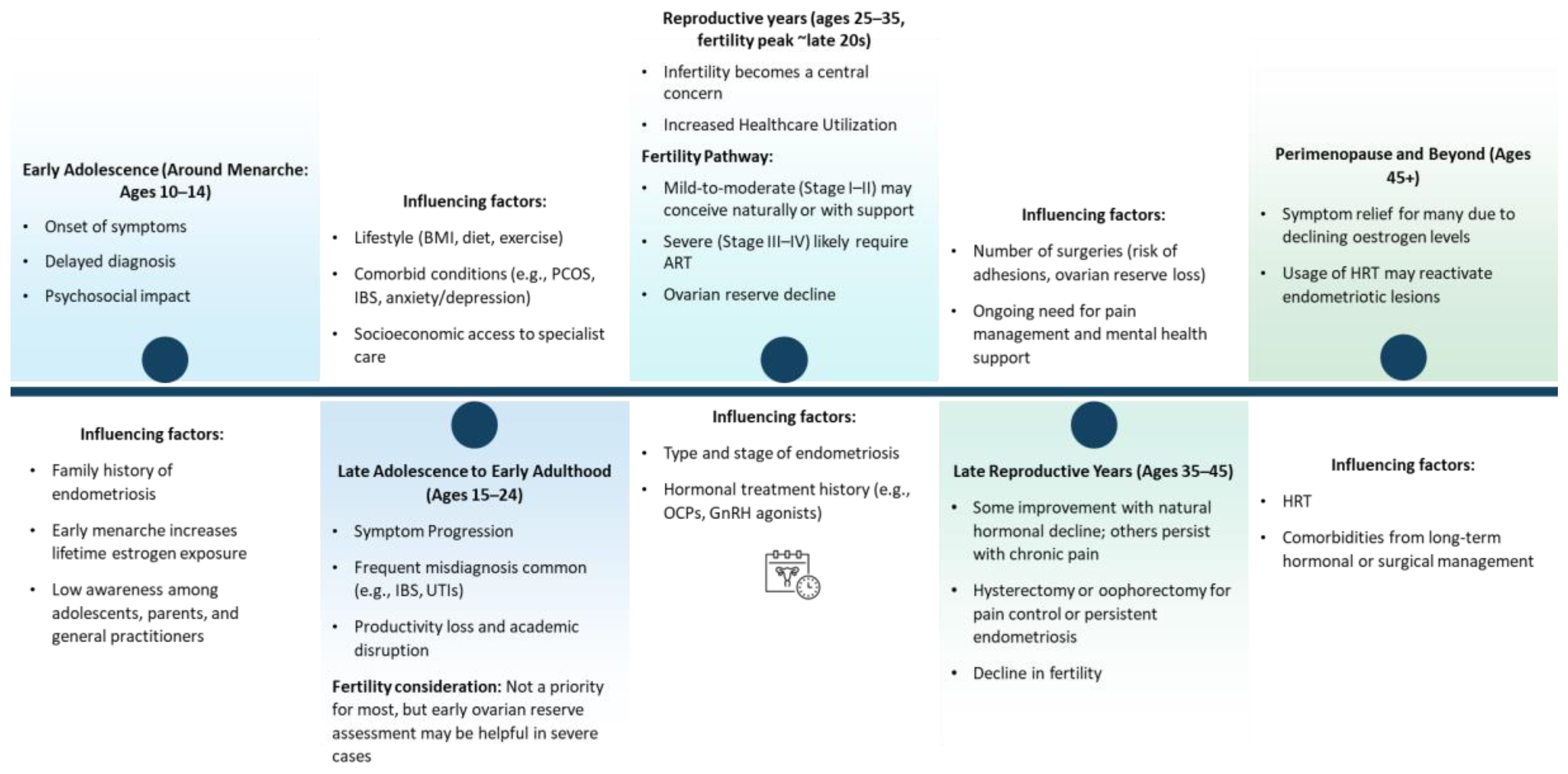

The life course trajectory of endometriosis beginning at menarche and extending through reproductive maturity and into menopause involves a dynamic interplay of biological, clinical, and psychosocial factors. The following figure depicts a longitudinal understanding of the condition’s onset, progression, and impact across key developmental stages:

Figure 1.

Life course of endometriosis.

Figure 1.

Life course of endometriosis.

1. Early Adolescence (Ages 10–14; Around Menarche)

The onset of endometriosis often coincides with menarche, yet early symptoms such as dysmenorrhea, pelvic pain, gastrointestinal disturbances, and fatigue are frequently normalised or misattributed to typical pubertal changes (Greene et al., 2009). This under-recognition and normalisation contribute to significant diagnostic delays, with an average delay of 7–11 years (Greene et al., 2009, Nezhat et al., 2025). In addition, there are significant psychosocial consequences during this stage, including school absenteeism, limited social participation, and increased vulnerability to mental health disorders such as anxiety and low self-esteem (Gallagher et al., 2018).

Some of the contributing factors at this stage include a family history of endometriosis (Liakopoulou et al., 2022), early menarche (<12 years), associated with prolonged oestrogen exposure over the life course (Lu et al., 2023) and limited awareness among adolescents, parents, and primary care providers (Simpson et al., 2021).

2. Late Adolescence to Early Adulthood (Ages 15–24)

During this phase, symptoms often become more complex and persistent, including chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and non-cyclical pain, with overlapping urological and gastrointestinal symptoms (DiVasta et al., 2018, Wüest et al., 2023). The initial consultations typically involve general practitioners or gynaecologists, however, misdiagnosis remains common, with symptoms often attributed to conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or urinary tract infections (Zuber et al., 2022). Endometriosis also causes significant distress in individuals which eventually reduces academic performance and limits their early career development due to pain and fatigue (Soliman et al., 2017) Fertility, while generally may not be an immediate concern, it may still require early assessment of ovarian reserve particularly in individuals presenting with severe form of the disease.

This phase is further influenced by multiple factors such as lifestyle-related determinants like body mass index (BMI), dietary patterns, and physical activity levels (Lalla et al., 2024), comorbidities including polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), IBS, anxiety, and depression (Smorgick et al., 2013, UK, 2020, Balun et al., 2019) and disparities in access to specialist care, particularly for individuals from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds (Medina-Perucha et al., 2022).

3. Reproductive Years (Ages 25–35, Fertility Peak ~Late 20s)

As individuals approach peak reproductive age, infertility becomes a predominant concern, with approximately 30–50% of those with endometriosis experiencing subfertility (Smolarz et al., 2021). Diagnostic rates increase during this period, often due to fertility challenges or escalating pain.

And therefore, the treatment pathways become more intensive, involving hormonal therapies, and in some cases, surgical interventions. In addition to these, assisted reproductive technologies (ART) are frequently utilised, especially among individuals with advanced stages of endometriosis. Ovarian reserve may be adversely affected by both the condition as well as the surgical management (e.g., cystectomy for endometriomas) (Fadhlaoui et al., 2014a).

Key determinants during this period include age at first childbirth and fertility postponement, disease phenotype and stage (e.g., superficial peritoneal, ovarian, or deep infiltrating endometriosis) and a history of hormonal suppression therapy (e.g., oral contraceptives, GnRH agonists/antagonists).

4. Late Reproductive Years (Ages 35–45)

In the late reproductive phase, symptoms may fluctuate, with some individuals reporting improvement due to declining oestrogen levels, while others continue to experience debilitating symptoms. Surgical interventions such as hysterectomy or oophorectomy may be utilised for pain management (Clinic, n.d.). This stage is further complicated by fertility challenges resulting from both advancing age and endometriosis-related reproductive tract pathology. Additionally, other key influencing factors include previous surgical history, which may contribute to pelvic adhesions and reduced ovarian reserve and ongoing needs for pain management.

5. Perimenopause and Beyond (Ages 45+)

Perimenopausal hormonal decline typically leads to regression of endometriotic lesions in many individuals, resulting in symptom relief (Broster, 2022). However, some women continue to experience symptoms due to residual disease or inflammation. While many women experience symptom relief after menopause, others may have ongoing or even new symptoms, particularly if using hormone replacement therapy (HRT). HRT, especially unopposed oestrogen, can reactivate endometriotic lesions (Gemmell et al., 2017). Therefore, HRT significantly affects this phases to balance menopausal symptom relief with risk of disease reactivation along with long-term health implications from chronic hormonal or surgical treatment, including effects on bone mineral density and cardiovascular health (Gemmell et al., 2017).

Delayed Diagnosis: A Systemic Failure

True prevalence of adolescent endometriosis is not clear due to a significant delay in adolescent endometriosis diagnosis around the world. A study involving 1418 women from 10 countries found a mean diagnostic delay of 6.7 years for endometriosis symptoms, with a mean delay of 11.6 years for unmarried women (Rahmioglua and Zondervana, 2024).

This delay is multifactorial, stemming from normalization of menstrual pain, inadequate awareness among healthcare professionals, and limited access to diagnostic tools like laparoscopy (De Corte et al., 2024).

A large-scale cross-sectional study conducted by Greene et al. (2009) involving 4,334 women with surgically confirmed endometriosis found that two-thirds of participants reported the onset of symptoms during adolescence. Notably, these individuals tended to delay seeking medical attention, often attributing their symptoms to "normal" period pain or encountering dismissive attitudes from caregivers and healthcare providers (Greene et al., 2009).

In many places, laparoscopic procedures are primarily reserved for fertility treatments (Mousa et al., 2021), meaning young girls and teenagers suffering from severe symptoms may not be able to receive the necessary investigation in time.

According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists’ committee opinion, at least two thirds of adolescent girls with chronic pelvic pain or dysmenorrhea unresponsive to hormonal therapies and NSAIDs will be diagnosed with endometriosis at the time of diagnostic laparoscopy ((ACOG), 2018, DiVasta et al., 2018). However, according to the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology 2022 Guideline, Laparoscopy is no longer the diagnostic gold standard and it is now only recommended in patients with negative imaging results and/or where empirical treatment was unsuccessful or inappropriate (DiVasta et al., 2018).

For adolescents, menstrual pain is often dismissed as a normal part of puberty, with cultural stigmas surrounding menstruation further silencing their experiences. Moreover, primary care providers may lack training to recognize atypical presentations of endometriosis in adolescents, such as non-cyclic pelvic pain or gastrointestinal symptoms mimicking irritable bowel syndrome (Sachedina and Todd, 2020).

This situation further worsens in young adolescents due to self-esteem issues. Young women who endure severe pain daily hide their pain due to embarrassment or fear of being perceived as weak. These early, invisible struggles can shape their reproductive future in silence (Sims et al., 2021).

Along with this lack of funding from organizations like the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which allocated just 0.038% of the 2022 health budget to the condition, despite it affecting 6.5 million women in the US and over 190 million globally, further increasing its burden leads adolescent women to suffer in silence without proper diagnosis (Ellis et al., 2022).

The reliance on laparoscopy, the gold standard for diagnosis, poses additional barriers due to its invasive nature and the reluctance to perform surgical procedures on young individuals. This diagnostic hesitancy perpetuates a cycle of misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment, leaving adolescents in a prolonged state of untreated pain and disease progression (Surrey, 2019).

Psychosocial Impact

The psychosocial burden of adolescence endometriosis is profound, affecting education, social development, and mental health. Chronic pain and fatigue often lead to school absenteeism, academic underperformance, and withdrawal from extracurricular activities, which are critical to socialization during adolescence (Missmer et al., 2021) The lack of understanding and validation from peers and authority figures exacerbates feelings of isolation and stigma.

Furthermore, untreated symptoms can contribute to mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression, and body image issues. Adolescents navigating the challenges of managing a chronic illness and the psychological upheavals of puberty are at heightened risk of developing long-term emotional and relational difficulties. The connection between prolonged exposure to endometriosis-associated pain and trauma, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), warrants critical consideration. Chronic pain, such as that caused by endometriosis, alters brain function, particularly in areas associated with emotional regulation, memory, and fear processing (Taylor, Kotlyar and Flores, 2021). Over time, this can dysregulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, a key system involved in the stress response, predisposing individuals to PTSD. Persistent pain can create a state of hypervigilance, where the brain becomes sensitized to pain and other stressors. This constant state of alertness mirrors the experience of trauma survivors, where even minor triggers can evoke outsized physical and emotional responses.

Unresolved trauma from adolescent endometriosis often manifests in adulthood as chronic anxiety and depression, rooted in the prolonged pain and emotional invalidation experienced during formative years (Delanerolle et al., 2021). These mental health challenges can complicate interpersonal dynamics, as individuals who withdrew from peers in adolescence may struggle to build trusting relationships later in life. Additionally, the burden of managing a poorly understood illness without adequate support can limit opportunities for post-traumatic growth, impeding personal development, resilience, and self-efficacy, thereby affecting overall quality of life.

Adolescent Endometriosis: A Silent Threat to Future Fertility

Adolescent who are suffering from endometriosis, may not even aware that their fertility being affected until they reached adult stage and wanted to start a family. By then, their precious time and ovarian reserve may already be lost.

Substantial delays between the first onset of symptoms and confirmed endometriosis not just lead them life with unbearable pain with emotional consequences it can lead to irreversible long-term effects on their fertility. Even under the best conditions, for a health couple clinical recognized pregnancy in one cycle or so called monthly fecundity rate is only about 15 to 20% (Kamel, 2010). As women age, this natural monthly chance gradually declines, which is expected (Delbaere et al., 2020). But for women with endometriosis, their monthly fecundity rate drops as low as 2 to 10%, depending on the severing of the disease (Fadhlaoui et al., 2014b).

The exact mechanism by which endometriosis impacts fertility remains unclear, and a cause-and-effect relationship has not been established. This does not mean that all women with endometriosis are subfertile or need assisted reproductive technology. However, there are also substantial studies that have proposed how endometriosis alters fertility potential through several mechanisms, such as distorted pelvic anatomy (OLIVE and PRITTS, 2002), impaired ovary function, affected endometrial receptivity (Marquardt et al., 2019), and reduced oocyte and embryo quality.

The management of Endometriosis associated with infertility in women requires a tailored approach considering patient’s age, disease severity, and their reproductive goals (Ferrero et al., 2018). Current treatments are focuses on improving fecundity by removing or reducing ectopic endometrial implants and restoring normal pelvic anatomy.

European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) 2022 guidelines suggest, to use Endometriosis Fertility Index (EFI) in contemporary treatment planning. EFI considers multiple factors, including the functional status of the reproductive organs and historical fertility data, to provide a personalized estimate of pregnancy potential. It helps clinicians to choose their treatment plan which patients will more benefit from (Adamson and Pasta, 2010).

A wide spectrum of treatment options has been examined, including expectant management, medical treatment, surgical treatment, and assisted reproductive technology. While various treatment strategies are available, the clinical effectiveness of some interventions has come under scrutiny (Ferrero et al., 2018).

Multi-Disciplinary Team Approach for Adolescence Endometriosis

The complex and multisystemic nature of endometriosis, particularly among adolescents, necessitates a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach to ensure effective and holistic care. This model integrates diverse clinical and allied health expertise to address the physical, psychological, and functional dimensions of the disease. Based on current practices in some hospitals, an MDT typically comprises of core clinical specialists such as gynaecologists, colorectal surgeons, gastroenterologists, urologists, radiologists, pain psychologists, and pelvic floor physiotherapists. Supporting this core group, allied healthcare professionals including nutritionists, psychotherapists, and specialist nurses further ensure the continuity and quality of care (Hospital, n.d., Centre, 2021). NHS England also advocates for the establishment of dedicated endometriosis centres with MDTs to manage complex cases in line with national standards (England, n.d., (NICE), 2024)

The MDT approach represents best practice in managing adolescent endometriosis, integrating medical, surgical, psychological, and lifestyle-based interventions to deliver holistic, patient-centred care. Multiple studies have consistently highlighted the benefits of MDT-led care in improving clinical outcomes, including pain management, quality of life, and post-surgical recovery particularly in severe cases such as deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) (Nasser et al., 2016, Ulrich et al., 2021, Greco, 2003). For instance, a 2016 study involving 87 women reported significant improvements in pain and quality of life at both 6- and 12-months following MDT-guided intervention (Nasser et al., 2016). Similarly, a 2021 case series emphasised the value of collaborative pre-operative planning involving subspecialist surgeons, which led to improved surgical outcomes for patients with DIE (Ulrich et al., 2021). However, successful implementation requires coordinated interprofessional collaboration, adequate staffing, and shared decision-making frameworks. Challenges such as limited resources and infrastructure may hinder widespread adoption, yet the MDT model remains a robust framework for enhancing outcomes and quality of life in young individuals living with this complex, chronic condition (Centre, 2021).

Prospective Medical Modalities for Management

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) is expected to issue new guidance recommending the use of relugolix–estradiol–norethisterone acetate (commonly referred to as relugolix combination therapy or by the brand name Ryeqo) as a long-term daily oral treatment for endometriosis. This intervention represents a potential paradigm shift in the pharmacological management of the condition, which historically has relied on gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, oral contraceptives, and surgical interventions.

According to NICE, approximately 1,000 women annually in England could benefit from Ryeqo therapy. It is proposed that this treatment will offer multiple potential advantages over conventional options. These include a more rapid onset of symptom relief compared to injectable alternatives, oral administration that enables at-home use and reduces the need for frequent clinical visits, and combined hormonal components that eliminate the requirement for additional add-back therapy. Moreover, Ryeqo is associated with a faster return to normal hormonal function upon discontinuation, enhancing its suitability as a flexible and patient-centred option. Additionally, NICE has recommended Ryeqo for individuals with moderate to severe endometriosis who have not responded to existing medical or surgical treatments. Once approved, the therapy will be accessible through routine NHS commissioning channels ((NICE), Expected publication 16 April 2025).

Ryeqo represents a promising development in endometriosis treatment, yet its integration into care pathways requires careful consideration. Despite NHS availability, disparities in access persist due to regional, socioeconomic, and diagnostic barriers, especially among adolescents and marginalised groups. Currently positioned as a second- or third-line therapy, delaying its use may postpone symptom relief for some patients, a strategy not yet fully supported by long-term evidence. While it offers convenience and promotes patient autonomy, Ryeqo should not replace comprehensive, multidisciplinary care essential for managing the broader psychosocial and functional impacts of endometriosis. Concerns also remain regarding its long-term safety particularly in younger populations and its cost-effectiveness. As its inclusion in NICE guidelines is anticipated, ongoing evaluation will be vital to ensure equitable access, appropriate use, and integration within holistic care models.

Role of Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) in Endometriosis

According to the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) 2022 guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis, for women with endometriosis experiencing infertility, ART, including In Vitro Fertilization (IVF), is considered an appropriate treatment option, particularly when tubal function is compromised.

In 2009, over 1400 live births were reported from 5600 IVF cycles in patients with endometriosis. However, there is controversy regarding the effectiveness of IVF for endometriosis patients compared to other infertility causes. A recent report showed an average delivery rate of 39.1% for endometriosis patients compared to 33.2% for all infertility patients, suggesting similar or slightly increased success in IVF compared to other infertility causes. However, there is a consistent trend for higher cycle cancellation rate and lower number of oocytes were obtained from endometriosis patients (Khine et al., 2016, Senapati et al., 2016).

Policy Landscape

National and international policies aimed at addressing endometriosis in adolescents are gradually evolving in response to growing awareness of the disease's early onset and long-term consequences. Although several countries have introduced frameworks and clinical guidelines targeting adolescent populations, significant policy gaps and systemic challenges remain.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, NICE provides clinical guidance for the diagnosis and management of endometriosis, including specific recommendations for adolescents. The guidelines advocate for early referral of young women (aged 17 and under) with suspected or confirmed endometriosis to age-appropriate services, including paediatric and adolescent gynaecology clinics, specialist gynaecology services, or accredited endometriosis centres, depending on local service availability ((UK), 2017). These guidelines acknowledge the need for specialised care pathways for adolescents presenting with complex or persistent symptoms. In addition to clinical guidelines, there are policy efforts in the UK emphasising menstrual health education within schools. Recent parliamentary initiatives advocate for the integration of endometriosis awareness into the national curriculum, aiming to improve symptom recognition and health-seeking behaviours among students (Parliament, 2024).

United States

In the United States, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ((ACOG)) provides adolescent-specific recommendations for the management of endometriosis, which focuses on cautious, evidence-based approach tailored to the developmental needs and risks unique to adolescent patients. These recommendations emphasise on conservative surgical intervention in conjunction with hormonal therapies such as combined oral contraceptives and progestins. It also discourages the long-term use of GnRH agonists outside of specialised care contexts, due to concerns regarding bone mineral density and other adverse effects. ACOG also recommends non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as the first-line pharmacologic treatment, while strongly discouraging narcotics outside multidisciplinary pain management teams ((ACOG), 2018).

European Union

The European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) has published comprehensive guidelines that include recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis in adolescents. The ESHRE guidelines emphasise the role of imaging particularly transvaginal and pelvic MRI in diagnostic accuracy, and advocate for surgical interventions, including laparoscopy, to be performed only by experienced endometriosis surgeons when clinically indicated. Additionally, postoperative hormonal suppression is strongly advised to prevent symptom recurrence and reduce the risk of disease progression (Group, 2022)

Barriers to Effective Management

Management of adolescence endometriosis is hindered by several factors, including limited research on age-specific treatment protocols, lack of access to specialized care, and systemic healthcare inequities. Current treatment options, such as hormonal therapies and pain management, are often adapted from adult guidelines without considering the unique physiological and developmental needs of adolescents.

Additionally, disparities in healthcare access disproportionately affect adolescents from marginalized communities, particularly in low-resource settings. Economic barriers, inadequate insurance coverage, and geographic inaccessibility to specialists exacerbate inequalities in diagnosis and treatment. For transgender and non-binary adolescents, gender-affirming care is often inaccessible, compounding the challenges they face in receiving appropriate and sensitive care for endometriosis (del Mar Pastor Bravo and Linander, 2024)

Severe endometriosis can lead to tissue damage, infertility, and premature ovarian failure. According to the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) 2022 guidelines, Adolescent with endometriosis should be counselled on the impact of endometriosis and surgical intervention on ovarian reserve and future fertility. And it further emphasised that fertility preservation options like oocyte or ovarian tissue cryopreservation should be dissussed. However,In low -middle income countries fertility preservation facilities are most available in private sectors limits the usage of these facilities among patients with endometriosis (Afferri et al., 2021, Asiimwe et al., 2022, Somigliana et al., 2015)

Although countries like the UK, US, and EU member states have established some degree of policy infrastructure for adolescent endometriosis, significant gaps remain in policy implementation, and enforcement. Advocacy organisations such as Endometriosis UK have called for greater governmental accountability and action, emphasising the need for standardised menstrual education, timely referrals, and mandatory training for general practitioners and school health staff. The absence of universal screening protocols and variability in healthcare provider knowledge contribute to protracted diagnostic timelines and fragmented care (UK, n.d.)

Several Organizations such as World Endometriosis Organizations (WEO), World Endometriosis Society (WES), World Endometriosis Research foundation (WERF) are closely working with World Health Organization (WHO) and Regional and National Organizations for Endometriosis for improving health outcomes for people with endometriosis (Adamson et al., 2010). Despite their efforts global disparities persist. In many low- and middle-income countries, awareness of endometriosis especially in younger populations is minimal. Cultural taboos surrounding menstruation, limited access to specialist care, and a dearth of adolescent-specific healthcare services contribute to systemic underdiagnosis and undertreatment.

Impact on Low-Middle-Income Countries

The impact of adolescent endometriosis in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is profound, exacerbating existing health inequities and creating a cycle of social, economic, and health challenges. The following outlines the major impacts;

Stigma: In many LMICs, cultural taboos around menstruation discourage adolescents from seeking care, perpetuating delays in diagnosis and treatment. Menstrual pain is often normalised, even when debilitating. Misunderstanding and stigmatisation of menstrual-related issues may lead to shame and withdrawal from social interactions, further impacting mental health and well-being

Minimal awareness: A lack of awareness among healthcare providers and communities about endometriosis further delays diagnosis, with many attributing symptoms to psychosomatic or non-gynaecological causes. This is can be profoundly challenging for parents to understand and provide the necessary support to their adolescent child.

Education disruption: Chronic pain and fatigue associated with adolescent endometriosis often led to frequent absenteeism, academic underachievement, and school dropouts, limiting future opportunities for affected individuals

Gender inequity: In patriarchal societies, the condition can exacerbate gender disparities, as girls and young women are disproportionately burdened with unaddressed health challenges, limiting their societal and economic participation

Body Image and Identity: Adolescence is a time of heightened self-awareness and body image development. Chronic pain and related symptoms, such as bloating, weight fluctuations, or scars from surgeries, can erode self-esteem, contributing to shame and body dysmorphia. Cultural expectations around menstruation and femininity may exacerbate the psychological burden. Adolescents may internalize feelings of inadequacy or fear about their reproductive future, especially in communities where fertility is highly valued, creating a chronic source of stress and worry.

Scarcity of specialists: LMICs often lack Endometriosis specialists, particularly in rural regions where resource-strapped systems can leave adolescent girls undiagnosed or misdiagnosed. For transgender and non-binary adolescents, the compounded barriers of accessing gender-affirming care in LMICs make it even harder to address endometriosis, amplifying feelings of isolation. Poor management of adolescent endometriosis increases the risk of infertility and chronic pain in adulthood, perpetuating health burdens and affecting future generations.

Missed Opportunities for Research

Missed opportunities for research into adolescent endometriosis in growing populations lead to compounding issues: misdiagnosis, inadequate treatment, and a widening gap between healthcare needs and available resources (Simpson et al., 2021). Misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis is common, with many teenagers suffering in silence or being told their pain is "just part of being a woman." This results in unnecessary emotional and physical distress, and in some cases, irreversible complications like infertility. In LMICs, this perpetuates cycles of inequity, economic strain, and poor health outcomes. Addressing this gap is not only a matter of improving individual well-being but also a crucial investment in public health, economic stability, and gender equity. Global disease burden may be further exacerbated when governments and global health organisations are less likely to allocate resources to address a condition if its prevalence, impact, and economic costs are not well-documented.

Lack of Epidemiological data: the paucity of data on adolescent endometriosis undermines efforts to advocate for comprehensive research, advocate for resources and implement effective interventions

Missed research potential: limited research infrastructure in LMICs prevent local solutions that aligned to cultural and socioeconomic context, leaving care strategies reliant on data and practices from high-income countries which may not be transferrable.

Settings and inclusivity: Adolescents in rural areas might face unique barriers to accessing care compared to their urban counterparts

Culturally appropriate interventions: Research is essential to identify effective, low-cost, and culturally acceptable treatments, particularly in resource-constrained settings. Without research tailored to the specific needs of LMICs, treatment guidelines rely on studies from high-income countries, which often use expensive therapies or technologies inaccessible in LMICs. The absence of culturally sensitive interventions also risks poor adherence to treatments, leading to worsening health outcomes.

Call to Action

Addressing adolescent endometriosis requires a multifaceted approach: An MDT approach for managing adolescent endometriosis due to the complex, multisystemic nature of the condition. Adolescents often face diagnostic delays, stigma, and fragmented care, which can be mitigated by coordinated input from gynaecologists, pain specialists, psychologists, and allied health professionals. An MDT ensures early, holistic intervention improving symptom control, mental health outcomes, and quality of life while supporting adolescents through a critical developmental phase.

Raising Awareness and Training: Educational initiatives targeting healthcare providers, educators, and parents are essential to dismantle misconceptions about menstruation and equip stakeholders with the knowledge to recognize and respond to symptoms of endometriosis early

School-based interventions: Incorporate menstrual health education and support systems in schools to reduce absenteeism and stigma

Improving Diagnostic Pathways: Investment in non-invasive diagnostic tools, such as biomarkers and imaging advancements, can reduce reliance on laparoscopy and facilitate earlier diagnosis.

Personalised Treatment Protocols: Research focusing on the unique needs of adolescents is crucial for developing age-appropriate therapies that minimize side effects and promote long-term health outcomes.

Enhancing Psychosocial Support: Integrating mental health services into endometriosis care models can address the emotional and psychological impact of the condition, promoting holistic well-being.

Promoting Equity in Care: Policies ensuring affordable, accessible, and inclusive care are critical to overcoming systemic barriers, particularly for adolescents in marginalized populations. Foster collaborations between LMICs and high-income countries to share resources, research, and expertise tailored to diverse settings.

This call to action is a reminder that we need to do better healthcare systems must evolve to meet the needs of young women with endometriosis, and patients must feel heard and supported.

Conclusions

Adolescence endometriosis represents a critical yet neglected intersection of gynaecological, developmental, and psychosocial health. By addressing these challenges, LMICs can mitigate the far-reaching impact of adolescent endometriosis, improving quality of life for affected individuals and advancing gender equity and health outcomes on a broader scale. This work can help healthcare systems in HICs better cater to immigrant populations. By perpetuating delays in diagnosis, dismissing symptoms, and offering inadequate management, society fails young individuals during a pivotal stage of life. A shift towards inclusive, evidence-based, and adolescent-centered approaches is essential to redress these shortcomings and empower affected adolescents to lead healthier, more fulfilling lives. Only by addressing the systemic gaps in awareness, research, and care can the silent suffering of adolescence endometriosis be transformed into an opportunity for meaningful progress in global health equity.

Author Contributions

GD conceptualised this paper. GD and PK wrote the first draft. All authors commented and agreed on all versions of the manuscript.

References

- De Corte, P. et al. (2024) ‘Time to Diagnose Endometriosis: Current Status, Challenges and Regional Characteristics—A Systematic Literature Review’, BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, pp. 118–130. [CrossRef]

- Delanerolle, G. et al. (2021) ‘A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Endometriosis and Mental-Health Sequelae; The ELEMI Project’, Women’s Health, 17. [CrossRef]

- del Mar Pastor Bravo, M. and Linander, I. (2024) ‘Access to healthcare among transgender and non-binary youth in Sweden and Spain: A qualitative analysis and comparison’, PLoS ONE, 19(5 May), pp. 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Missmer, S.A. et al. (2021) ‘Impact of endometriosis on life-course potential: A narrative review’, International Journal of General Medicine, 14, pp. 9–25. [CrossRef]

- Polak, G. et al. (2013) ‘Endometriosis in adolescents’, Wiadomości lekarskie (Warsaw, Poland : 1960), 66(2), pp. 192–194. [CrossRef]

- Sachedina, A. and Todd, N. (2020) ‘Dysmenorrhea, endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain in adolescents’, JCRPE Journal of Clinical Research in Pediatric Endocrinology, 12(Suppl 1), pp. 7–17. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, C.N., Lomiguen, C.M. and Chin, J. (2021) ‘Combating Diagnostic Delay of Endometriosis in Adolescents via Educational Awareness: A Systematic Review’, Cureus, 13(5), pp. 0–7. [CrossRef]

- Smolarz, B., Szyłło, K. and Romanowicz, H. (2021) ‘Endometriosis: Epidemiology, classification, pathogenesis, treatment and genetics (review of literature)’, International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(19). [CrossRef]

- Surrey, E. (2019) ‘Diagnosing endometriosis: Is laparoscopy the gold standard?’, OBG Management, S3(April), pp. 1–6.

- Taylor, H.S., Kotlyar, A.M. and Flores, V.A. (2021) ‘Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: clinical challenges and novel innovations’, The Lancet, 397(10276), pp. 839–852. [CrossRef]

- (ACOG), T. A. C. o. O. a. G. 2018. Dysmenorrhea and Endometriosis in the Adolescent.

- (NICE), N. I. f. H. a. C. E. 2024. Endometriosis: diagnosis and management [Online]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng73/chapter/recommendations [Accessed 12 April 2025].

- (NICE), N. I. f. H. a. C. E. Expected publication 16 April 2025. Relugolix–estradiol–norethisterone for treating symptoms of endometriosis [ID3982] (Draft) [Online]. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-ta10873 [Accessed 12 April 2025].

- (UK), N. G. A. 2017. Endometriosis: diagnosis and management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

- Adamson, G. D., Kennedy, S. & Hummelshoj, L. 2010. Creating Solutions in Endometriosis: Global Collaboration through the World Endometriosis Research Foundation. Journal of Endometriosis, 2, 3-6. [CrossRef]

- Adamson, G. D. & Pasta, D. J. 2010. Endometriosis fertility index: the new, validated endometriosis staging system. Fertility and Sterility, 94, 1609-1615. [CrossRef]

- Afferri, A., Allen, H., Booth, A., Dierickx, S., Pacey, A. & Balen, J. 2021. Barriers and facilitators for the inclusion of fertility care in reproductive health policies in Africa: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Human Reproduction Update, 28, 190-199. [CrossRef]

- Asiimwe, S., Osingada, C. P., Mbalinda, S. N., Muyingo, M., Ayebare, E., Namutebi, M. & Muwanguzi, P. A. 2022. Women’s experiences of living with involuntary childlessness in Uganda: a qualitative phenomenological study. BMC Women's Health, 22, 532. [CrossRef]

- Balun, J., Dominick, K., Cabral, M. D. & Taubel, D. 2019. Endometriosis in adolescents: a narrative review. Pediatric Medicine, 2. [CrossRef]

- Broster, A. 2022. What is Perimenopause & How Has it Been Linked to Endometriosis? [Online]. Endometriosis Foundation of America. Available: https://www.endofound.org/what-is-perimenopause-how-has-it-been-linked-to-endometriosis [Accessed 12 April 2025].

- Centre, S. M. E. 2021. Your Multidisciplinary Treatment Team for Endometriosis [Online]. Available: https://drseckin.com/your-multidisciplinary-treatment-team-for-endometriosis/ [Accessed 12 April 2025].

- Clinic, M. n.d. Endometriosis [Online]. Available: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/endometriosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20354656 [Accessed].

- Delbaere, I., Verbiest, S. & Tydén, T. 2020. Knowledge about the impact of age on fertility: a brief review. Ups J Med Sci, 125, 167-174. [CrossRef]

- DiVasta, A. D., Vitonis, A. F., Laufer, M. R. & Missmer, S. A. 2018. Spectrum of symptoms in women diagnosed with endometriosis during adolescence vs adulthood. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 218, 324.e1-324.e11. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, K., Munro, D. & Clarke, J. 2022. Endometriosis Is Undervalued: A Call to Action. Front Glob Womens Health, 3, 902371. [CrossRef]

- England, N. n.d. NHS STANDARD CONTRACT FOR COMPLEX GYNAECOLOGY- SEVERE ENDOMETRIOSIS.

- Fadhlaoui, A., Bouquet de la Jolinière, J. & Feki, A. 2014a. Endometriosis and infertility: how and when to treat? Front Surg, 1, 24. [CrossRef]

- Fadhlaoui, A., Bouquet de la Jolinière, J. & Feki, A. 2014b. Endometriosis and Infertility: How and When to Treat? Frontiers in Surgery, Volume 1 - 2014. [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, S., Giulio, E. & and Barra, F. 2018. Current and emerging treatment options for endometriosis. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 19, 1109-1125. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, J. S., DiVasta, A. D., Vitonis, A. F., Sarda, V., Laufer, M. R. & Missmer, S. A. 2018. The Impact of Endometriosis on Quality of Life in Adolescents. J Adolesc Health, 63, 766-772. [CrossRef]

- Gemmell, L. C., Webster, K. E., Kirtley, S., Vincent, K., Zondervan, K. T. & Becker, C. M. 2017. The management of menopause in women with a history of endometriosis: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update, 23, 481-500. [CrossRef]

- Greco, C. D. 2003. Management of adolescent chronic pelvic pain from endometriosis: a pain center perspective. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol, 16, S17-9. [CrossRef]

- Greene, R., Stratton, P., Cleary, S. D., Ballweg, M. L. & Sinaii, N. 2009. Diagnostic experience among 4,334 women reporting surgically diagnosed endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility, 91, 32-39. [CrossRef]

- Group, E. E. G. D. 2022. Endometriosis Guideline of European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryolog.

- Hospital, C. n.d. Cromwell Hospital - International Centre for Endometriosis [Online]. Available: https://www.cromwellhospital.com/services-specialties/international-centre-for-endometriosis/ [Accessed 12 April 2025].

- Kamel, R. M. 2010. Management of the infertile couple: an evidence-based protocol. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, 8, 21. [CrossRef]

- Khine, Y. M., Taniguchi, F. & Harada, T. 2016. Clinical management of endometriosis-associated infertility. Reproductive Medicine and Biology, 15, 217-225. [CrossRef]

- Lalla, A. T., Onyebuchi, C., Jorgensen, E. & Clark, N. 2024. Impact of lifestyle and dietary modifications for endometriosis development and symptom management. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol, 36, 247-254. [CrossRef]

- Liakopoulou, M. K., Tsarna, E., Eleftheriades, A., Arapaki, A., Toutoudaki, K. & Christopoulos, P. 2022. Medical and Behavioral Aspects of Adolescent Endometriosis: A Review of the Literature. Children (Basel), 9. [CrossRef]

- Lu, M. Y., Niu, J. L. & Liu, B. 2023. The risk of endometriosis by early menarche is recently increased: a meta-analysis of literature published from 2000 to 2020. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 307, 59-69. [CrossRef]

- Marquardt, R. M., Kim, T. H., Shin, J.-H. & Jeong, J.-W. 2019. Progesterone and Estrogen Signaling in the Endometrium: What Goes Wrong in Endometriosis? International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20, 3822. [CrossRef]

- Medina-Perucha, L., Pistillo, A., Raventós, B., Jacques-Aviñó, C., Munrós-Feliu, J., Martínez-Bueno, C., Valls-Llobet, C., Carmona, F., López-Jiménez, T., Pujolar-Díaz, G., Flo Arcas, E., Berenguera, A. & Duarte-Salles, T. 2022. Endometriosis prevalence and incidence trends in a large population-based study in Catalonia (Spain) from 2009 to 2018. Women's Health, 18, 17455057221130566. [CrossRef]

- Mousa, M., Al-Jefout, M., Alsafar, H., Becker, C. M., Zondervan, K. T. & Rahmioglu, N. 2021. Impact of Endometriosis in Women of Arab Ancestry on: Health-Related Quality of Life, Work Productivity, and Diagnostic Delay. Frontiers in Global Women's Health, Volume 2 - 2021. [CrossRef]

- Nasser, S., Mitchell, A., Limdi, S., Byrne, P. & Ahmad, G. 2016. A Multidisciplinary Team Approach to Severe Endometriosis. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology, 23, S181. [CrossRef]

- Nezhat, C. R., Oskotsky, T. T., Robinson, J. F., Fisher, S. J., Tsuei, A., Liu, B., Irwin, J. C., Gaudilliere, B., Sirota, M., Stevenson, D. K. & Giudice, L. C. 2025. Real world perspectives on endometriosis disease phenotyping through surgery, omics, health data, and artificial intelligence. npj Women's Health, 3, 8. [CrossRef]

- OLIVE, D. L. & PRITTS, E. A. 2002. The Treatment of Endometriosis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 955, 360-372.

- Parliament, U. 2024. Endometriosis Education in Schools [Online]. Available: https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2024-05-21/debates/C187898F-E330-4406-A0C0-B835898BF7D6/EndometriosisEducationInSchools [Accessed 12 April 2025].

- Rahmioglua, N. & Zondervana, K. T. 2024. Endometriosis: disease mechanisms and health disparities. Bull World Health Organ. [CrossRef]

- Senapati, S., Sammel, M. D., Morse, C. & Barnhart, K. T. 2016. Impact of endometriosis on in vitro fertilization outcomes: an evaluation of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technologies Database. Fertility and Sterility, 106, 164-171.e1. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, C. N., Lomiguen, C. M. & Chin, J. 2021. Combating Diagnostic Delay of Endometriosis in Adolescents via Educational Awareness: A Systematic Review. Cureus, 13, e15143. [CrossRef]

- Sims, O. T., Gupta, J., Missmer, S. A. & Aninye, I. O. 2021. Stigma and Endometriosis: A Brief Overview and Recommendations to Improve Psychosocial Well-Being and Diagnostic Delay. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 8210. [CrossRef]

- Smolarz, B., Szyłło, K. & Romanowicz, H. 2021. Endometriosis: Epidemiology, Classification, Pathogenesis, Treatment and Genetics (Review of Literature). Int J Mol Sci, 22. [CrossRef]

- Smorgick, N., Marsh, C. A., As-Sanie, S., Smith, Y. R. & Quint, E. H. 2013. Prevalence of pain syndromes, mood conditions, and asthma in adolescents and young women with endometriosis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol, 26, 171-5. [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A. M., Coyne, K. S., Gries, K. S., Castelli-Haley, J., Snabes, M. C. & Surrey, E. S. 2017. The Effect of Endometriosis Symptoms on Absenteeism and Presenteeism in the Workplace and at Home. J Manag Care Spec Pharm, 23, 745-754. [CrossRef]

- Somigliana, E., Viganò, P., Filippi, F., Papaleo, E., Benaglia, L., Candiani, M. & Vercellini, P. 2015. Fertility preservation in women with endometriosis: for all, for some, for none? Hum Reprod, 30, 1280-6. [CrossRef]

- Tragantzopoulou, P. 2024. Endometriosis and stigmatization: A literature review. Journal of Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain Disorders, 16, 117-122. [CrossRef]

- UK, A. E. 2020. Endometriosis in the UK: time for change; APPG on Endometriosis Inquiry Report 202. Endometriosis UK.

- UK, E. n.d. Urgent Government action needed to improve education for young people and healthcare practitioners: Launch of Endometriosis Action Month.

- Ulrich, A., MD, Arabkhazaeli, M., MD, Dellacerra, G., DO, Malcher, F., MD & Lerner, V., MD 2021. A Multidisciplinary Approach to the Patient with Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol Cases. [CrossRef]

- Wüest, A., Limacher, J. M., Dingeldein, I., Siegenthaler, F., Vaineau, C., Wilhelm, I., Mueller, M. D. & Imboden, S. 2023. Pain Levels of Women Diagnosed with Endometriosis: Is There a Difference in Younger Women? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol, 36, 140-147. [CrossRef]

- Zuber, M., Shoaib, M. & Kumari, S. 2022. Magnetic resonance imaging of endometriosis: a common but often hidden, missed, and misdiagnosed entity. Pol J Radiol, 87, e448-e461. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).