Introduction

The Aquatic Origins of Life: A Geochemical and Physiological Context

The Primordial Ocean: Cradle of Life

The leading hypothesis for abiogenesis posits that life first emerged within the aqueous environments of early Earth, approximately 3.8–4.0 billion years ago [

1,

2]. These primordial oceans, formed under the influence of intense volcanic activity, hydrothermal fluxes and atmospheric transformation, were chemically dynamic and devoid of free oxygen. Volcanic outgassing contributed key volatile compounds such as CO

2, N

2, SO

2, and H

2S, while the weathering of igneous rocks released essential cations and anions into solution [

3]. The result was a mineral-rich, mildly acidic, and reducing aqueous medium capable of supporting complex prebiotic chemistry.

Key electrolytes identified in these early marine environments included sodium (Na

+), chloride (Cl

−), potassium (K

+), calcium (Ca

2+), magnesium (Mg

2+), sulfate (SO

42−), and bicarbonate (HCO

3−). Their relative proportions were governed by geochemical equilibria involving mineral precipitation, hydrothermal interactions, and seawater-rock exchange. Notably, Na

+ and Cl

− were present in significant concentrations, creating a hypotonic milieu favorable for the spontaneous formation of lipid vesicles precursors of protocells [

4].

The discovery of mineral-rich hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor has reinforced the plausibility of submarine environments as potential cradles for life. These vents not only provided essential chemical gradients and heat but also catalyzed reactions via naturally occurring transition metal sulfides. Such microenvironments may have supported the polymerization of amino acids, nucleotides, and the formation of protocell membranes, a critical step toward the emergence of cellular life [

5].

The recognition that amniotic fluid is not merely a passive cushion, but an active biochemical reservoir, invites a more nuanced understanding of its evolutionary role. Beyond ionic balance, amniotic fluid contributes to lung maturation through surfactant regulation, gastrointestinal development via fetal swallowing, and immune priming through bioactive molecules such as cytokines and exosomes [

6].

Evolutionary Continuity: Ionic Parallels in Amniotic Fluid

A remarkable evolutionary echo is observed in the similarity between the ionic composition of early ocean water and that of amniotic fluid, the protective liquid that envelops the fetus during development [

7]. Both media contain comparable concentrations of Na

+, K

+, Cl

−, and HCO

3− ions essential for osmotic balance, cellular excitability, and pH regulation. This chemical congruence suggests a deep evolutionary conservation of the aqueous environment in which early life, and by extension, human life, develops (

Table 1).

The fetal milieu may be viewed as a microcosmic recapitulation of Earth’s ancient seas. The biochemical conditions present in amniotic fluid maintain an optimal ionic and pH environment for fetal cell proliferation, enzymatic activity, and organogenesis. These parallels underscore a physiological continuity that transcends geological eras.

Claude Bernard’s Legacy and the Evolution of Homeostasis

The emergence of homeostatic mechanisms marked a critical step in the evolution of life. Claude Bernard’s concept of the “milieu intérieur”, later expanded by Walter Cannon as “homeostasis”, emphasizes the necessity for internal constancy amidst external fluctuation [

8,

9]. From the earliest single-celled organisms to complex multicellular species, life has depended on the maintenance of ionic gradients and fluid balance.

The semipermeable lipid bilayer of the cell membrane, embedded with transport proteins, permits selective exchange of solutes. Mechanisms such as the Na+/K+-ATPase pump and various ion channels generate and preserve electrochemical gradients that are indispensable for membrane potential, signal transduction, nutrient uptake, and waste elimination.

Modern extracellular fluids, interstitial fluid, plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, retain an ionic composition reminiscent of ancestral seawater. Enzymatic pathways and cellular functions have evolved under these ionic constraints, further reinforcing the notion that the internal milieu of modern organisms is chemically imprinted by their evolutionary past.

The concept of homeostasis was revolutionary because introduced the idea that organisms are not passive responders to their environments, but rather active regulators of their internal states. This regulation is achieved through complex negative feedback mechanisms involving neural, endocrine, and paracrine signaling systems. For example, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis plays a central role in modulating physiological responses to stress, while the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system is essential for maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance [

10,

11].

In the context of pregnancy, homeostasis acquires an even more critical dimension. The maternal-fetal interface represents a dual system of regulatory interactions, whereby maternal physiological systems adapt to support fetal development without compromising maternal health. Placental endocrine function, fetal fluid exchange, and amniotic fluid composition are all finely tuned through homeostatic mechanisms. Disturbances in these systems, such as in cases of preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, or intrauterine growth restriction, illustrate the consequences of disrupted homeostasis at the maternal-fetal boundary [

12].

Moreover, recent advances in systems biology and computational modeling have underscored the multiscale nature of homeostasis, from gene expression and intracellular signaling to organ-level dynamics and whole-body physiology. Homeostatic regulation is now understood to be a product of network-level coordination, often involving redundant pathways that provide resilience against environmental insults. This complexity is particularly evident during fetal development, where precise temporal and spatial regulation of gene networks governs morphogenesis, organogenesis, and immune tolerance.

The thermodynamic and kinetic favorability of prebiotic reactions in hydrothermal vent environments has been increasingly supported by geochemical modeling and experimental simulations [

13]. Alkaline hydrothermal systems, in particular, offer a pH and redox gradient across mineral interfaces that could have served as natural electrochemical reactors, catalyzing the formation of essential organic molecules such as amino acids, nucleotides, and simple peptides. These environments also provided compartmentalization through porous mineral matrices, facilitating the concentration and stabilization of reactive intermediates critical for the origin of life.

Ultimately, Claude Bernard’s insight laid the foundation for modern physiology, biomedicine, and developmental biology. His legacy is particularly salient in the study of maternal-fetal health, where the principles of homeostasis inform our understanding of how intrauterine environments support, or disrupt, the trajectory of human development [

14,

15].

Physiological Implications: Water Compartments and Dynamic Equilibrium

Water, the fundamental medium of biochemical reactions and molecular transport, comprises approximately 60% of the human body by weight, with variation depending on age, sex, and body composition. Intracellular fluid accounts for roughly two-thirds of total body water, while extracellular fluid, including interstitial fluid, plasma, and transcellular fluids, constitutes the remaining third.

The dynamic exchange between these compartments is governed by osmotic gradients, hydrostatic pressures and membrane permeability. Water homeostasis is intricately regulated by neuroendocrine mechanisms involving the hypothalamus, antidiuretic hormone (ADH), renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), and atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP). These pathways maintain plasma osmolality, blood volume, and systemic arterial pressure [

16].

Interstitial fluid serves as a crucial intermediary between blood plasma and the intracellular environment, facilitating nutrient delivery, waste removal, and signal transduction. Its composition closely mirrors that of plasma, with the exception of large proteins that are generally retained within the vasculature. This similarity underscores the fluid’s role as a physiological conduit and its evolutionary continuity with marine environments.

Moreover, the analogy between interstitial fluid dynamics and seawater circulation in porous substrates highlights an evolutionary adaptation: both systems maintain chemical gradients necessary for life by enabling diffusion-driven transport. Even minute disturbances in electrolyte balance, such as those caused by dehydration, fluid overload, or toxicant exposure, can disrupt cellular function, alter membrane potentials and impair organ systems [

17].

In the fetal context, amniotic fluid represents a unique extracellular compartment that supports growth and development. It functions not only as a cushion against mechanical trauma but also as a critical regulator of temperature, hydration, and biochemical signaling. The fetal swallowing of amniotic fluid contributes to gastrointestinal tract maturation and renal excretion, which in turn influences amniotic fluid volume. This cyclical exchange exemplifies a tightly regulated aquatic microenvironment shaped by homeostatic principles.

Ultimately, the orchestration of fluid compartments, from the cellular to the systemic level, reflects a complex yet evolutionarily conserved mechanism for sustaining life in a water-based milieu.

The stability of this fluid architecture, like that of early marine habitats, ensures cellular viability and organismal integrity. Even minor perturbations in electrolyte balance can lead to profound physiological consequences, illustrating the fragile equilibrium inherited from our aquatic ancestry [

18].

Environmental Toxicants and Microplastics and Nanoplastics (MNPs): A New Threat to Life’s Aquatic Niche

Prenatal exposure to environmental toxicants has long been recognized as a major determinant of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. Compounds such as heavy metals (e.g., lead, mercury), persistent organic pollutants (e.g., dioxins, PCBs), nicotine, and pharmaceutical residues can induce oxidative stress, disrupt endocrine signaling and alter epigenetic regulation during key windows of fetal vulnerability [

26].

More recently, MNPs, defined as synthetic polymer particles <5 mm and <1 μm in diameter, respectively, have emerged as novel and pervasive environmental contaminants. Originating from both the fragmentation of larger plastic debris and primary microplastic products, these particles have been detected in marine, freshwater, terrestrial, and atmospheric compartments [

27]. Their ubiquitous presence in the biosphere increases the likelihood of human exposure through ingestion, inhalation, and dermal contact [

28,

29].

Every year, an estimated 11 million metric tons of plastic waste enter the world’s oceans, a figure projected to nearly triple by 2040 without urgent mitigation efforts [

30,

31].

Plastic is responsible for significant damage to human health, economy and environment. This damage occurs at every stage of its life cycle, from the extraction of coal, oil, and gas (which are the main raw materials in 98% of plastic materials), to the recycling process and to its final disposal. The pervasiveness of plastic in all environments is well documented [

32].

The greatest vulnerability to the toxic effects of pollutants occurs during fetal life and in the first years of life. In this period, with differentiated times, occur maturation of the following: 1) organs and systems, 2) metabolic, endocrine, immunological systems, 3) hepatic and renal detoxification mechanisms, 4) skin and blood-brain barrier [

33].

Once internalized, MNPs can cross epithelial barriers, enter systemic circulation and accumulate in organs, including reproductive tissues. Importantly, they also act as vectors for co-contaminants, adsorbing hydrophobic chemicals such as phthalates, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and heavy metals onto their surfaces. These adsorbed toxicants may be co-delivered into sensitive biological compartments, amplifying their harmful potential [

34,

35].

Recent studies have confirmed the presence of MNPs in critical maternal and neonatal matrices, including: placenta [

36], amniotic fluid [

37], and human breast milk [

38].

These findings challenge the assumption that the intrauterine and early postnatal environments are insulated from environmental pollution. The concept of the fetus developing in a pristine sanctuary is increasingly untenable in the face of accumulating evidence that synthetic particles permeate the maternal-fetal interface.

The potential for MNPs to interfere with fetal programming, immune system maturation, long-term metabolic outcomes and with the vitality of trophoblastic cells [

39] is of growing concern [

40]. An association was found between the presence of microplastics in meconium, and reduced microbiota diversity [

41]. Other studies showed that microplastic levels in the placenta correlated with reduced birth weight, Apgar scores at 1 minute and with reduced fetal growth in IUGR pregnancies [

42]. Furthermore, the presence of MPs in the placenta was correlated with premature birth [

43].

Emerging data suggest that prenatal and perinatal exposure to MNPs may have profound effects on neurodevelopment [

44].The developing fetal brain is highly vulnerable to environmental insults due to the ongoing processes of cell proliferation, migration, differentiation, synaptogenesis, and myelination. MNPs, along with the chemical contaminants they carry, have been shown in animal models to cross the blood-brain barrier and accumulate in brain tissues, where they induce oxidative stress and neuroinflammation [

45,

46]. This raises the possibility that MNPs exposure could interfere with the molecular signaling pathways essential for neurodevelopment, including those mediated by neurotrophic factors, neurotransmitters, and endocrine signals [

47].

Animal studies report changes in behavior, learning capacity, and synaptic plasticity in offspring exposed to MNPs in utero, supporting the hypothesis that these particles may act as neurodevelopmental disruptors [

48].

In this context, the amniotic fluid, so chemically similar to ancient seawater, has become a repository for anthropogenic contaminants, reflecting not only our evolutionary past but also our modern ecological impact.

Longitudinal human studies are urgently needed to confirm these associations and to elucidate the dose-response relationship between MNP burden and neurocognitive outcomes across the lifespan.

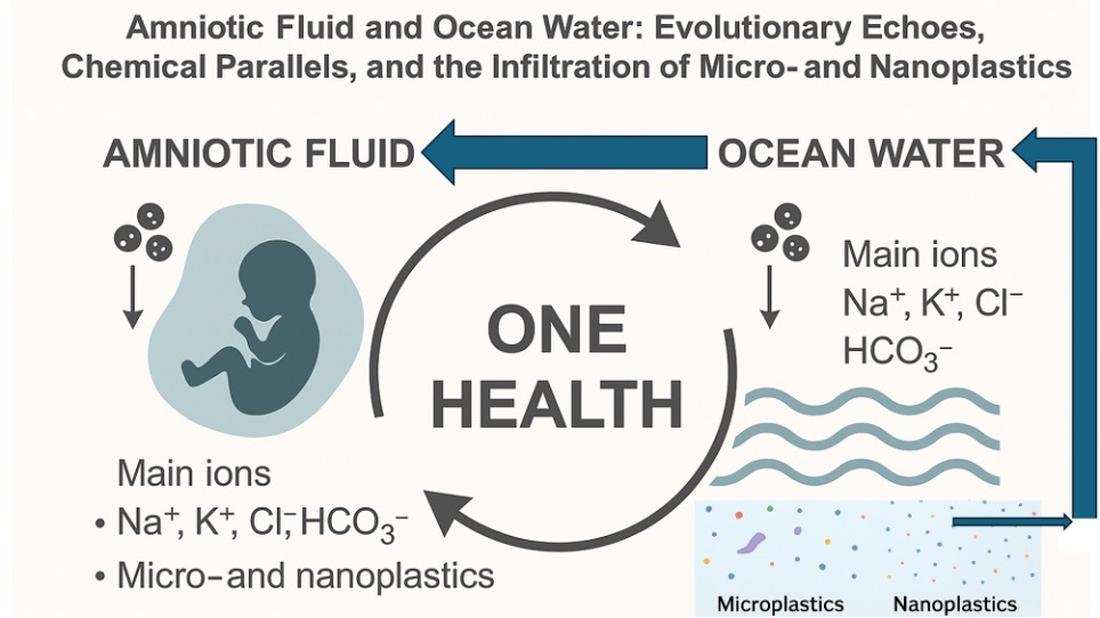

The One Health Paradigm: Linking Ocean and Amniotic Fluid

The One Health paradigm offers a unifying conceptual framework that recognizes the interdependence of human, animal, and environmental health. Originally applied to zoonotic disease surveillance and ecosystem preservation, the One Health approach has expanded to include the study of environmental pollutants and their systemic effects across biological domains [

49,

50].

Microplastics and nanoplastics exemplify the need for this integrative perspective. Their widespread environmental dissemination and biological accumulation demonstrate that synthetic particles do not respect taxonomic, geographical, or physiological boundaries. What is found in the depths of the ocean is now also detected within the intrauterine environment (

Figure 1).

One Health is not merely a conceptual tool but a practical model that enables the detection, monitoring, and mitigation of complex contaminant pathways across marine, terrestrial, and clinical environments. The trophic transfer of MNPs across marine food webs, from plankton to fish to humans, illustrates the continuity of exposure across species and ecosystems [

51,

52]. Likewise, the presence of the same contaminants in umbilical cord blood, amniotic fluid and placenta confirms the intergenerational and cross-species implications of pollution [

36].

This model calls for transdisciplinary collaboration, integrating marine biologists, obstetricians, epidemiologists, chemists, and environmental engineers. Current research silos often fail to capture the continuity between oceanic plastic load and fetal plastic exposure. A unified surveillance system, anchored in the One Health framework, could map this continuum, enabling early warning systems and regulatory responses [

53]. Incorporating One Health into educational curricula, from secondary school to medical training, can cultivate a new generation of professionals who understand that fetal well-being is linked to environmental stewardship. The paradigm also has profound ethical implications: it challenges anthropocentric notions of health and invites a planetary ethic of responsibility, acknowledging that protecting the fetus also means protecting the planet that nourishes the fetus itself [

54].

The amniotic fluid and ocean water are chemically and symbolically linked: both are aqueous matrices that sustain life, buffered by evolutionary processes and now disrupted by human activity. The translocation of plastic particles from marine systems into fetal compartments epitomizes the global reach of pollution and its implications for intergenerational health.

Addressing this crisis demands coordinated, cross-sectoral efforts involving marine biologists, obstetricians, toxicologists, public health officials and policy-makers. By adopting a One Health strategy, we can better understand and mitigate the continuum of exposure that bridges ecosystems and embryonic development.

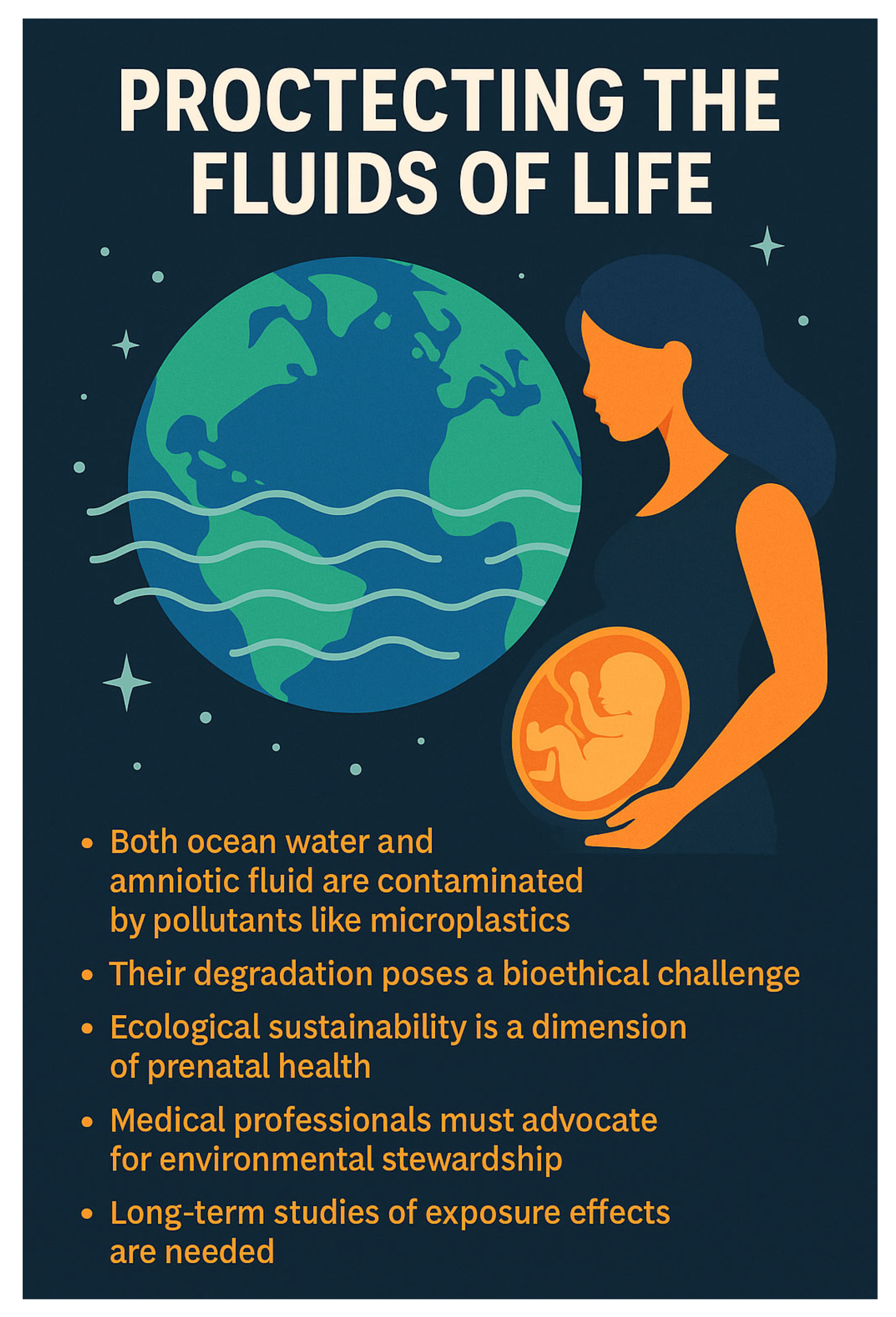

Conclusions: Protecting the Fluids of Life

Amniotic fluid is not merely a by-product of pregnancy; it is an evolutionary innovation that reflects the primordial marine environments from which life originated. Its ionic composition, buffering capacity and biologically active constituents create an ideal microenvironment for fetal development, an echo of Earth’s early oceans.

Today, both of these vital fluids, ocean water and amniotic fluid, are contaminated by synthetic pollutants, particularly MNPs. This dual pollution of planetary and intrauterine waters serves as a stark reminder of the interwoven fates of ecology and human health.

Safeguarding future generations requires an urgent commitment to reducing plastic pollution, enhancing monitoring systems for emerging contaminants and protecting the aquatic environments that cradle life in its earliest stages. In doing so, we preserve not only the health of individuals but the integrity of the evolutionary lineage that connects all life forms.

In addition, the degradation of these life-sustaining fluids represents not only a medical and environmental emergency but also a bioethical challenge. If intrauterine life is now vulnerable to artificial contaminants previously confined to industrial waste, then the scope of perinatal care must broaden to include environmental stewardship.

Medical professionals, especially obstetricians and neonatologists, must now advocate for ecological sustainability as a dimension of prenatal health (

Figure 2). Hospitals and labs cannot be isolated from the ecosystem; rather, the integrity of pregnancy outcomes is inextricably linked to the integrity of the biosphere.

Furthermore, transdisciplinary collaboration must evolve from academic rhetoric to policy enforcement. The acknowledgment of MNPs exposure as a public health threat requires integration of clinical data, toxicological thresholds, and regulatory frameworks.

Long-term cohort studies tracking prenatal exposure to plastic derivatives and associated outcomes in neurodevelopment, immune regulation and metabolic programming must become standard scientific practice [

55]

Above all, the amniotic fluid must not become the final destination for humanity’s waste. Its contamination is not merely symbolic; it is mechanistically implicated in disruptions to fetal physiology and developmental trajectories.

To defend the fluids of life is to defend the origin, continuity, and future of life itself. From the geological depths of hydrothermal vents to the intimacy of the womb, water has been the universal medium of existence and we must now protect it with equal universality and urgency [

56].

Future Directions and Implications for Policy and Research

The growing detection of MNPs in critical biological fluids, including amniotic fluid, raises urgent concerns for fetal development, reproductive health, and long-term disease trajectories. This emerging evidence mandates coordinated action on several levels:

Clinical Research: There is a pressing need for prospective cohort studies and toxicological models to investigate the effects of MNPs and associated endocrine disruptors during pregnancy. Particular attention should be given to fetal neurodevelopment, immune programming, and epigenetic modulation.

Such studies should utilize integrative approaches combining metabolomics, transcriptomics, and epigenomics to characterize fetal responses to plastic-derived contaminants. Investment in green chemistry is essential for developing truly biodegradable, non-toxic alternatives to current polymer-based plastics. Research should prioritize the design of materials that degrade into inert, non-bioaccumulative products [

57].

Analytical Methods: Standardized, sensitive and reproducible methods must be developed to detect and quantify MNPs in human biological matrices, including amniotic fluid, placenta, and cord blood. New advancements in high-resolution spectroscopy (e.g., pyrolysis-GC/MS, micro-FTIR) and nanoscale imaging should be incorporated into standardized protocols to detect ultrafine plastic particles in biological matrices. These technologies will improve detection sensitivity and specificity, reducing false negatives in fetal and neonatal samples. Regulatory bodies such as the FDA, EMA and WHO must define acceptable thresholds for MNPs concentrations in human biological matrices. This will require interdisciplinary consensus on toxicity benchmarks and risk assessment methodologies, facilitating global harmonization of standards. Establishing open-access databases for MNPs concentrations in environmental and clinical samples would enhance transparency and global cooperation. These repositories could include metadata on sampling techniques, population demographics and geographical distribution, fostering meta-analyses and public health modeling.

Environmental Policy: Governments and regulatory agencies must urgently implement stricter controls on plastic production and disposal, with an emphasis on banning non-essential single-use plastics and improving microplastic filtration in wastewater systems. A tax on plastic manufacturing and subsidies for biodegradable alternatives could shift market behavior. Legislative frameworks like the EU’s REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation, and Restriction of Chemicals) should be adapted globally to include MNPs as emerging contaminants.

One Health Integration: Policy frameworks should embed the One Health perspective, recognizing that protecting marine ecosystems is intrinsically linked to safeguarding intrauterine environments and, ultimately, human reproductive health. Establishing international research consortia linking oceanographers, obstetricians, toxicologists, and environmental chemists is critical for implementing a One Health surveillance system. This system should monitor sentinel species (e.g., plankton, mollusks, marine mammals) and human pregnancy biomarkers in tandem.

Public Awareness: Educational campaigns should inform people about the routes of plastic exposure, its reproductive risks and actionable steps to reduce contact.

Integrating MNP-related content into medical and environmental science curricula could prepare the next generation of professionals to address this issue proactively [

58,

59,

60].

Understanding the molecular and systemic effects of MNPs during pregnancy will be essential not only for fetal safety but also for redefining our interaction with the synthetic materials that saturate the biosphere [

61].

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, but the study did not require ethical approval, since it is a literature review study, and did not involve human and animal subjects. Ultimately, ethical review and approval for this study are not applicable for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Branscomb, E.; Russell, M.J. Frankenstein or a Submarine Alkaline Vent: Who is Responsible for Abiogenesis? BioEssays. 2018, 40, 1700182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brack, A. Life in the solar system. Adv Space Res. 1999, 24, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Du, Y. Hypothesis for Molecular Evolution in the Pre-Cellular Stage of the Origin of Life. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2025, 16, e70001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, M.J.; Barge, L.M.; Bhartia, R.; et al. The drive to life on wet and icy worlds. Astrobiology. 2014, 14, 308–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Branscomb, E.; Russell, M.J. Frankenstein or a Submarine Alkaline Vent: Who is Responsible for Abiogenesis?: Part 2: As life is now, so it must have been in the beginning. Bioessays. 2018, 40, e1700182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, V.J.; Deshmukh, M.; Wallach, T. The Molecular Ecology of Amniotic Fluid. J Reprod Immunol. 2024, 158, 104093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliburska, J.; Kocyłowski, R.; Komorowicz, I.; et al. Concentrations of Mineral in Amniotic Fluid and Their Relations to Selected Maternal and Fetal Parameters. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2016, 172, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cooper, S.J. From Claude Bernard to Walter Cannon. Emergence of the concept of homeostasis. Appetite. 2008, 51, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billman, G.E. Homeostasis: The Underappreciated and Far Too Often Ignored Central Organizing Principle of Physiology. Front Physiol. 2020, 11, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rasmussen, J.M.; Thompson, P.M.; Entringer, S.; Buss, C.; Wadhwa, P.D. Fetal programming of human energy homeostasis brain networks: Issues and considerations. Obes Rev. 2022, 23, e13392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Homeostasis: The Underappreciated and Far Too Often Ignored Central Organizing Principle of Physiology. Front Physiol. 2020, 11, 200. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, R.M.; Labad, J.; Buss, C.; Ghaemmaghami, P.; Raikkonen, K. Transmitting biological effects of stress in utero: implications for mother and offspring. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013, 38, 1843–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, W.; Baross, J.; Kelley, D.; Russell, M.J. Hydrothermal vents and the origin of life. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008, 6, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmaso, N.; Tomasi, S.; Vaccarino, F.M. Neurodevelopmental origins of health and disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2014, 27, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, S.J. From Claude Bernard to Walter Cannon. Emergence of the concept of homeostasis. Appetite. 2008, 51, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobias, A.; Ballard, B.D.; Mohiuddin, S.S. Physiology, Water Balance. [Updated 2022 Oct 3]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541059/.

- Molecular Biology and Physiology of Water and Solute Transport. Edited by Stefan Hohmann Găteborg University Găteborg, Sweden and S~ren Nielsen Institute of Anatomy University of Ărhus Ărhus, Denmark. ISBN 978-1-4613-5439-0 ISBN 978-1-4615-1203-5 (eBook). 2000 Springer Science+Business Media New York. [CrossRef]

- Sterling, P. Allostasis: a model of predictive regulation. Physiol Behav. 2012, 106, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Gao, B.; Lei, L.; et al. Intercellular flow dominates the poroelasticity of multicellular tissues. Nat Phys. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Huo, X.; Cheng, Z.; et al. Early-life exposure to widespread environmental toxicants and maternal-fetal health risk: A focus on metabolomic biomarkers. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 739, 139626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzsimmons, E.D.; Bajaj, T. Embryology, Amniotic Fluid. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jul 17. [PubMed]

- Pullano, J.G.; Cohen-Addad, N.; Apuzzio, J.J.; et al. Water and salt conservation in the human fetus and newborn. I. Evidence for a role of fetal prolactin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1989, 69, 1180–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NOAA Sea water. Available from: https://www.noaa.gov/jetstream/ocean/sea-water.

- LibreTexts. Chemistry and Geochemistry of the Oceans. Available from: https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Environmental_Chemistry/Geochemistry_(Lower)/02%3A_The_Hydrosphere/2.03%3A_Chemistry_and_geochemistry_of_the_oceans.

- EBSCOhost. Seawater Composition. Available from: https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/oceanography/seawater-composition.

- Dai, Y.; Huo, X.; Cheng, Z.; et al. Early-life exposure to widespread environmental toxicants and maternal-fetal health risk: A focus on metabolomic biomarkers. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 739, 139626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, J.; Ma, Y.; Ruan, J.; et al. The invisible Threat: Assessing the reproductive and transgenerational impacts of micro- and nanoplastics on fish. Environ Int. 2024, 183, 108432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Płotka-Wasylka, J.; Mulkiewicz, E.; Lis, H.; et al. Endocrine disrupting compounds in the baby’s world—A harmful environment to the health of babies. Sci Total Environ. 2023, 881, 163350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Han, R.; Yao, Z.; et al. Intergenerational transfer of micro(nano)plastics in different organisms. J Hazard Mater. 2025, 488, 137404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 30.Jambeck et al., 2015; Lau et al., 2020]." Jambeck JR, Geyer R, Wilcox C, et al. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, W.W.Y.; Shiran, Y.; Bailey, R.M.; et al. Evaluating scenarios toward zero plastic pollution. Science. 2020, 369, 1455–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

https://annalsofglobalhealth.org/articles/10.5334/aogh.4056.

- Chauhan, R.; Archibong, A.E.; Ramesh, A. Imprinting and Reproductive Health: A Toxicological Perspective. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 16559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rubin, A.E.; Zucker, I. Interactions of microplastics and organic compounds in aquatic environments: A case study of augmented joint toxicity. Chemosphere. 2022, 289, 133212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Guo, J.L.; Xue, J.C.; et al. Phthalate metabolites: Characterization, toxicities, global distribution, and exposure assessment. Environ Pollut. 2021, 291, 118106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragusa, A.; Svelato, A.; Santacroce, C.; et al. Plasticenta: First evidence of microplastics in human placenta. Environ Int. 2021, 146, 106274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Liang, L.; Li, Q.; et al. Association between microplastics in human amniotic fluid and pregnancy outcomes: Detection and characterization using Raman spectroscopy and pyrolysis GC/MS. J Hazard Mater. 2025, 482, 136637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragusa, A.; Notarstefano, V.; Svelato, A.; et al. Raman Microspectroscopy Detection and Characterisation of Microplastics in Human Breastmilk. Polymers 2022, 14, 2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ragusa, A.; Cristiano, L.; Di Vinci, P.; Familiari, G.; Nottola, S.A.; Macchiarelli, G.; Svelato, A.; De Luca, C.; Rinaldo, D.; Neri, I.; Facchinetti, F. Artificial plasticenta: how polystyrene nanoplastics affect in-vitro cultured human trophoblast cells. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2025, 13, 1539600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lopez, G.L.; Lamarre, A. The impact of micro- and nanoplastics on immune system development and functions: Current knowledge and future directions. Reprod Toxicol. 2025, 135, 108951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Liu, X.; Guo, J.; Yang, R.; Wang, H.; Sun, Y.; Chen, B.; Dong, R. The Association Between Microplastics and Microbiota in Placentas and Meconium: The First Evidence in Humans. Environ Sci Technol. 2023, 57, 17774–17785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amereh, F.; Amjadi, N.; Mohseni-Bandpei, A.; Isazadeh, S.; Mehrabi, Y.; Eslami, A.; Naeiji, Z.; Rafiee, M. Placental plastics in young women from general population correlate with reduced foetal growth in IUGR pregnancies. Environ Pollut. 2022, 314, 120174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halfar, J.; Čabanová, K.; Vávra, K.; Delongová, P.; Motyka, O.; Špaček, R.; Kukutschová, J.; Šimetka, O.; Heviánková, S. Microplastics and additives in patients with preterm birth: The first evidence of their presence in both human amniotic fluid and placenta. Chemosphere. 2023, 343, 140301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prüst, M.; Meijer, J.; Westerink, R.H.S. The plastic brain: neurotoxicity of micro- and nanoplastics. Particle and Fibre Toxicology. 2020, 17, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhao, S.; Li, M.; et al. Maternal exposure to polystyrene microplastics causes neurobehavioral impairments in mouse offspring via oxidative stress and apoptosis pathways. Environmental Science & Technology. 2022, 56, 8262–8270. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.; Jiang, R.; Hu, S.; et al. Polystyrene microplastics induced neurotoxicity in murine offspring via maternal exposure. Chemosphere. 2023, 320, 135828. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Halimu, G.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Internalization and toxicity: A preliminary study of effects of nanoplastic particles on human lung epithelial cell. Science of The Total Environment. 2019, 694, 133794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zada, L.; Miodownik, M.; Rowson, J.; et al. Developmental neurotoxicity of environmental nanoplastics: emerging evidence and future perspectives. NeuroToxicology. 2024, 97, 128–137. [Google Scholar]

- WHO One Health. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/one-health#tab=tab_1.

- Pitt, S.J.; Gunn, A. The One Health Concept. Br J Biomed Sci. 2024, 81, 12366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- MacKendrick, N. Plastic childhood: An environmental sociology of toys. Sociol Perspect. 2014, 57, 507–529. [Google Scholar]

- Trasande, L.; et al. Environmental chemicals in pregnancy and early childhood: An overview of global threats to healthy development. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2020, 223, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rummel, C.D.; Löder, M.G.J.; Fricke, N.F.; et al. Plastic ingestion by pelagic and demersal fish from the North Sea and Baltic Sea. Mar Pollut Bull. 2016, 102, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature. 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrigan, P.J. Pollution and children’s health. Sci Total Environ. 2018, 650 Pt 2, 2389–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vethaak, A.D.; Legler, J. Microplastics and human health. Science. 2021, 371, 672–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Chatterjee, S. Microplastic pollution, a threat to marine ecosystem and human health: a short review. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2017, 24, 21530–21547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, R.; Weder, C.; Petri-Fink, A.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B. Emergence of nanoplastic in the environment and possible impact on human health. Environ Sci Technol. 2019, 53, 1748–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, T.S.; Cole, M.; Lewis, C. Interactions of microplastic debris throughout the marine ecosystem. Nat Ecol Evol. 2017, 1, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rist, S.; Almroth, B.C.; Hartmann, N.B.; Karlsson, T.M. A critical perspective on early communications concerning human health aspects of microplastics. Sci Total Environ. 2018, 626, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetu, S.G.; Sarker, I.; Schrameyer, V.; et al. Plastic leachates impair growth and oxygen production in Prochlorococcus, the ocean’s most abundant photosynthetic bacteria. Commun Biol. 2019, 2, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).