Submitted:

21 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

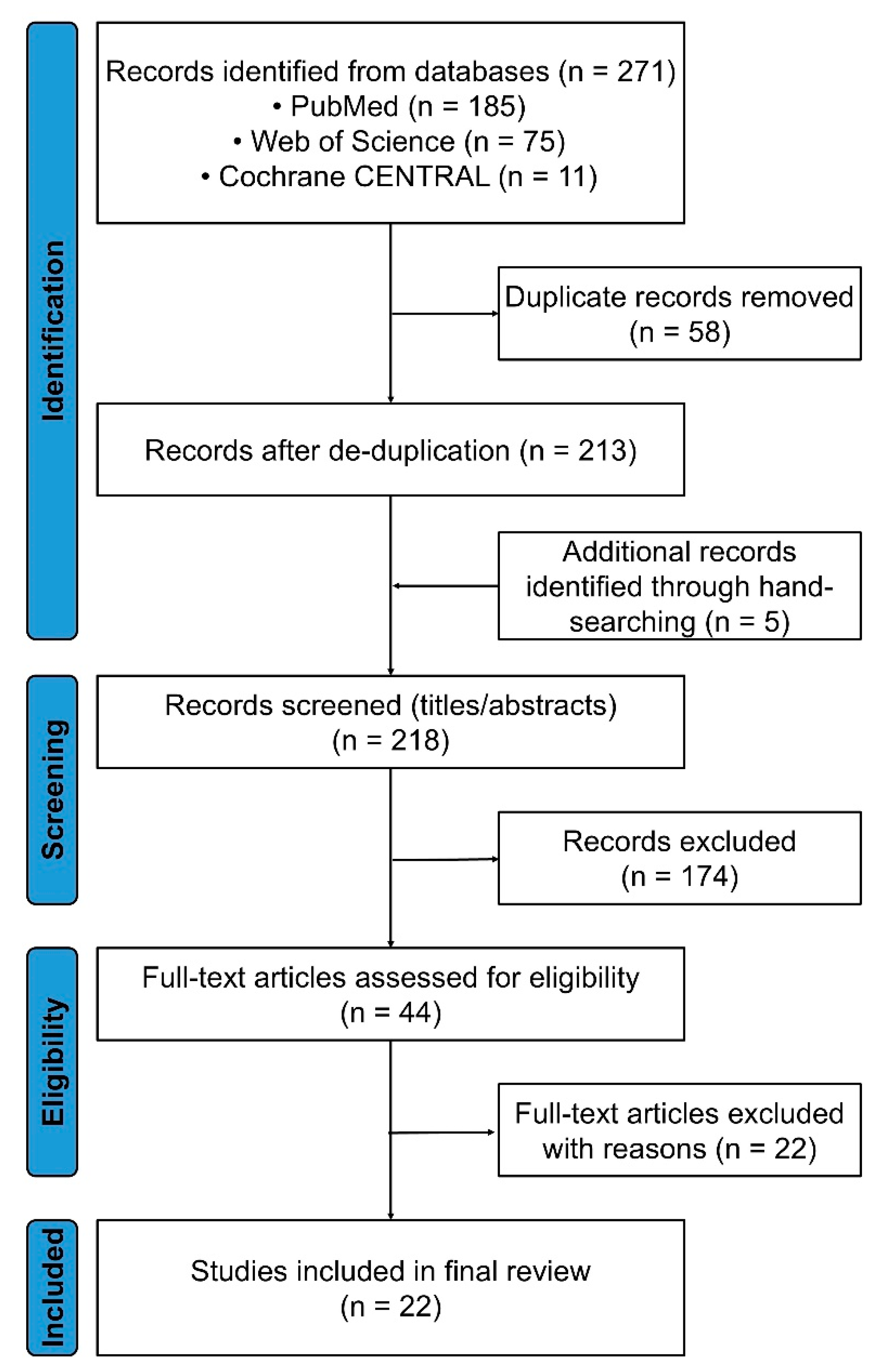

2.1. Framework and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Risk-of-Bias Appraisal

2.7. Data Synthesis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

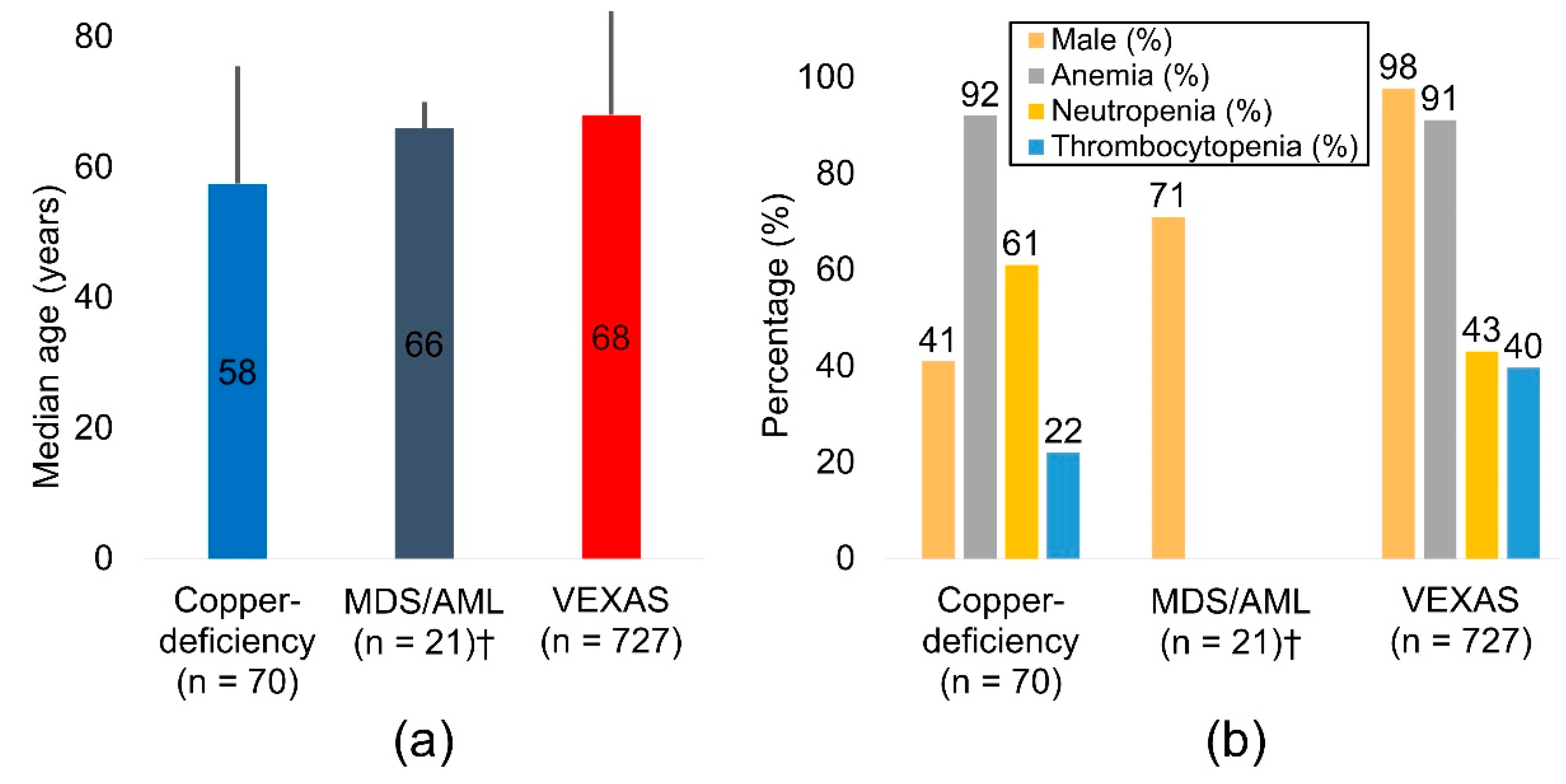

3.1. Demographic and Hematologic Landscape

3.2. Molecular and Morphologic Correlates

3.3. Algorithm Performance

3.4. Risk of Bias Overview

3.5. Summary of Key Findings

3.6. What This Review Adds

3.7. Mechanistic Perspectives on Vacuole Biology

3.8. Clinical Implications

3.9. Limitations and Potential Biases

3.10. Future Directions

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huff, J.D.; Keung, Y.K.; Thakuri, M.; Beaty, M.W.; Hurd, D.D.; Owen, J.; Molnar, I. Copper deficiency causes reversible myelodysplasia. Am J Hematol 2007, 82, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregg, X.T.; Reddy, V.; Prchal, J.T. Copper deficiency masquerading as myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood 2002, 100, 1493–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, D.B.; Ferrada, M.A.; Sikora, K.A.; Ombrello, A.K.; Collins, J.C.; Pei, W.; Balanda, N.; Ross, D.L.; Ospina Cardona, D.; Wu, Z. , et al. Somatic Mutations in UBA1 and Severe Adult-Onset Autoinflammatory Disease. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 2628–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. bmj 2021, 372. [Google Scholar]

- NIHR. PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/home.

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernan, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savovic, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I. , et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurnari, C.; Pagliuca, S.; Durkin, L.; Terkawi, L.; Awada, H.; Kongkiatkamon, S.; Zawit, M.; Hsi, E.D.; Carraway, H.E.; Rogers, H.J. , et al. Vacuolization of hematopoietic precursors: an enigma with multiple etiologies. Blood 2021, 137, 3685–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchino, K.; Quang, L.V.; Enomoto, M.; Nakano, Y.; Yamada, S.; Matsumura, S.; Kanasugi, J.; Takasugi, S.; Nakamura, A.; Horio, T. , et al. Cytopenia associated with copper deficiency. EJHaem 2021, 2, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfdanarson, T.R.; Kumar, N.; Hogan, W.J.; Murray, J.A. Copper deficiency in celiac disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 2009, 43, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfdanarson, T.R.; Kumar, N.; Li, C.Y.; Phyliky, R.L.; Hogan, W.J. Hematological manifestations of copper deficiency: a retrospective review. Eur J Haematol 2008, 80, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, A.; Leone, F.; Caggiano, V.; Hinojosa-Azaola, A.; Martin-Nares, E.; Guaracha-Basanez, G.A.; Torres-Ruiz, J.; Ayumi Kawakami-Campos, P.; Hissaria, P.; Callisto, A. , et al. Efficacy and safety of conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in VEXAS syndrome: real-world data from the international AIDA network. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16, 1539756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, M.M.; El Fassi, D.; Nielsen, C.T.H.; Krintel, S.B.; Graudal, N.; Hansen, J.W. Treatment experiences with focus on IL-6R inhibition in patients with VEXAS syndrome and a case of remission with azacytidine treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2025, 64, 826–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjadj, J.; Nguyen, Y.; Mouloudj, D.; Bourguiba, R.; Heiblig, M.; Aloui, H.; McAvoy, C.; Lacombe, V.; Ardois, S.; Campochiaro, C. , et al. Efficacy and safety of targeted therapies in VEXAS syndrome: retrospective study from the FRENVEX. Ann Rheum Dis 2024, 83, 1358–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, A.; Tsuchida, N.; Uchiyama, Y.; Horita, N.; Kobayashi, S.; Kishimoto, M.; Kobayashi, D.; Matsumoto, H.; Asano, T.; Migita, K. , et al. Efficient detection of somatic UBA1 variants and clinical scoring system predicting patients with variants in VEXAS syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2024, 63, 2056–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusne, Y.; Ghorbanzadeh, A.; Dulau-Florea, A.; Shalhoub, R.; Alcedo, P.E.; Nghiem, K.; Ferrada, M.A.; Hines, A.; Quinn, K.A.; Panicker, S.R. , et al. Venous and arterial thrombosis in patients with VEXAS syndrome. Blood 2024, 143, 2190–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, L.; Caratsch, L.; Lotscher, F.; Seitz, L.; Seitz, P.; Coattrenec, Y.; Seebach, J.; Vilinovszki, O.; Balabanov, S.; Nilsson, J. , et al. VEXAS syndrome: a Swiss national retrospective cohort study. Swiss Med Wkly 2024, 155, 3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, D.B.; Bodian, D.L.; Shah, V.; Mirshahi, U.L.; Kim, J.; Ding, Y.; Magaziner, S.J.; Strande, N.T.; Cantor, A.; Haley, J.S. , et al. Estimated Prevalence and Clinical Manifestations of UBA1 Variants Associated With VEXAS Syndrome in a Clinical Population. JAMA 2023, 329, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascaro, J.M.; Rodriguez-Pinto, I.; Poza, G.; Mensa-Vilaro, A.; Fernandez-Martin, J.; Caminal-Montero, L.; Espinosa, G.; Hernandez-Rodriguez, J.; Diaz, M.; Rita-Marques, J. , et al. Spanish cohort of VEXAS syndrome: clinical manifestations, outcome of treatments and novel evidences about UBA1 mosaicism. Ann Rheum Dis 2023, 82, 1594–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, A.S.; Koster, M.J.; Bock, A.R.; Go, R.S.; Warrington, K.J.; Olteanu, H.; Lasho, T.L.; Patnaik, M.M.; Reichard, K.K. Targeted testing of bone marrow specimens with cytoplasmic vacuolization to identify previously undiagnosed cases of VEXAS syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2023, 62, 3947–3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Cullen, T.; Sumpton, D.; Damodaran, A.; Heath, D.; Bosco, A.; Doo, N.W.; Kidson-Gerber, G.; Cheong, A.; Lawford, R. , et al. VEXAS syndrome: lessons learnt from an early Australian case series. Intern Med J 2022, 52, 658–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekinian, A.; Zhao, L.P.; Chevret, S.; Desseaux, K.; Pascal, L.; Comont, T.; Maria, A.; Peterlin, P.; Terriou, L.; D’Aveni Piney, M. , et al. A Phase II prospective trial of azacitidine in steroid-dependent or refractory systemic autoimmune/inflammatory disorders and VEXAS syndrome associated with MDS and CMML. Leukemia 2022, 36, 2739–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgin-Lavialle, S.; Terrier, B.; Guedon, A.F.; Heiblig, M.; Comont, T.; Lazaro, E.; Lacombe, V.; Terriou, L.; Ardois, S.; Bouaziz, J.D. , et al. Further characterization of clinical and laboratory features in VEXAS syndrome: large-scale analysis of a multicentre case series of 116 French patients. Br J Dermatol 2022, 186, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comont, T.; Heiblig, M.; Riviere, E.; Terriou, L.; Rossignol, J.; Bouscary, D.; Rieu, V.; Le Guenno, G.; Mathian, A.; Aouba, A. , et al. Azacitidine for patients with Vacuoles, E1 Enzyme, X-linked, Autoinflammatory, Somatic syndrome (VEXAS) and myelodysplastic syndrome: data from the French VEXAS registry. Br J Haematol 2022, 196, 969–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrada, M.A.; Savic, S.; Cardona, D.O.; Collins, J.C.; Alessi, H.; Gutierrez-Rodrigues, F.; Kumar, D.B.U.; Wilson, L.; Goodspeed, W.; Topilow, J.S. , et al. Translation of cytoplasmic UBA1 contributes to VEXAS syndrome pathogenesis. Blood 2022, 140, 1496–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, N.; Kunishita, Y.; Uchiyama, Y.; Kirino, Y.; Enaka, M.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Taguri, M.; Yamanaka, S.; Takase-Minegishi, K.; Yoshimi, R. , et al. Pathogenic UBA1 variants associated with VEXAS syndrome in Japanese patients with relapsing polychondritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2021, 80, 1057–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrada, M.A.; Sikora, K.A.; Luo, Y.; Wells, K.V.; Patel, B.; Groarke, E.M.; Ospina Cardona, D.; Rominger, E.; Hoffmann, P.; Le, M.T. , et al. Somatic Mutations in UBA1 Define a Distinct Subset of Relapsing Polychondritis Patients With VEXAS. Arthritis Rheumatol 2021, 73, 1886–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takami, A.; Uchino, K. Discovering the hidden link: hematological disorders caused by copper deficiency. Int J Hematol 2025, 10.1007/s12185-025-04036-7. [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.S.; Mortensen, M.; Simon, A.K. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. Cell Cycle 2011, 10, 1719–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierro, F.; Fazio, M.; Murdaca, G.; Stagno, F.; Gangemi, S.; Allegra, A. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Myelodysplastic Syndrome: Roles in Development, Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savy, C.; Bourgoin, M.; Cluzeau, T.; Jacquel, A.; Robert, G.; Auberger, P. VEXAS, Chediak-Higashi syndrome and Danon disease: myeloid cell endo-lysosomal pathway dysfunction as a common denominator? Cell Mol Biol Lett 2025, 30, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, E.L.; Gonzalez-Ibanez, A.M.; Mendoza, P.; Ruiz, L.M.; Riedel, C.A.; Simon, F.; Schuringa, J.J.; Elorza, A.A. Copper deficiency-induced anemia is caused by a mitochondrial metabolic reprograming in erythropoietic cells. Metallomics 2019, 11, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty-Raju, N.; Cook, R.; Erber, W.N. Vacuolated neutrophils in ethanol toxicity. Br J Haematol 2004, 127, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbadry, M.I.; Mabed, M. Bone Marrow Vacuolization at the Crossroads of Specialties: Molecular Insights and Diagnostic Challenges. Eur J Haematol 2025. [CrossRef]

- Liapis, K.; Vrachiolias, G.; Spanoudakis, E.; Kotsianidis, I. Vacuolation of early erythroblasts with ring sideroblasts: a clue to the diagnosis of linezolid toxicity. Br J Haematol 2020, 190, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbach, L.M.; Caviles, A.P.; Mitus, W.J. Chloramphenicol toxicity. Reversible vacuolization of erythroid cells. N Engl J Med 1960, 263, 724–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballo, O.; Stratmann, J.; Serve, H.; Steffen, B.; Finkelmeier, F.; Brandts, C. Blast vacuolization in AML patients indicates adverse-risk AML and is associated with impaired survival after intensive induction chemotherapy. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0223013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Chen, Y.H.; Mina, A.; Altman, J.K.; Kim, K.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, X.; Jennings, L.; Sukhanova, M. Unique morphologic and genetic characteristics of acute myeloid leukemia with chromothripsis: a clinicopathologic study from a single institution. Hum Pathol 2020, 98, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, H.S. The hematological complications of alcoholism. Alcohol Health Res World 1997, 21, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Shang, B.; Pei, Y.; Shi, M.; Niu, X.; Dou, L.; Drokow, E.K.; Xu, F.; Bai, Y.; Sun, K. A higher percentage of leukemic blasts with vacuoles predicts unfavorable outcomes in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res 2021, 109, 106638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khambatta, S.; Nguyen, D.L.; Beckman, T.J.; Wittich, C.M. Kearns-Sayre syndrome: a case series of 35 adults and children. Int J Gen Med 2014, 7, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellanne-Chantelot, C.; Schmaltz-Panneau, B.; Marty, C.; Fenneteau, O.; Callebaut, I.; Clauin, S.; Docet, A.; Damaj, G.L.; Leblanc, T.; Pellier, I. , et al. Mutations in the SRP54 gene cause severe congenital neutropenia as well as Shwachman-Diamond-like syndrome. Blood 2018, 132, 1318–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Guhde, G.; Suter, A.; Eskelinen, E.L.; Hartmann, D.; Lullmann-Rauch, R.; Janssen, P.M.; Blanz, J.; von Figura, K.; Saftig, P. Accumulation of autophagic vacuoles and cardiomyopathy in LAMP-2-deficient mice. Nature 2000, 406, 902–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanelli, M.; Ruggeri, L.; Sanguedolce, F.; Zizzo, M.; Martino, G.; Genua, A.; Ascani, S. Parvovirus B19 Infection in a Patient with Common Variable Immunodeficiency. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2021, 13, e2021026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inai, K.; Noriki, S.; Iwasaki, H.; Naiki, H. Risk factor analysis for bone marrow histiocytic hyperplasia with hemophagocytosis: an autopsy study. Virchows Arch 2014, 465, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CMS. 25CLABQ2. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/fee-schedules/clinical-laboratory-fee-schedule-clfs/files/25CLABQ2.

- UNC. UBA1Q Mutation Quantitative Detection, DDPCR (VEXAS Syndrome). Available online: https://www.uncmedicalcenter.org/mclendon-clinical-laboratories/available-tests/uba1q-mutation-quantitative-detection-ddpcr-vexas-syndrome/.

- University, J.H. Myeloid Panel, NGS, Blood. Available online: https://pathology.jhu.edu/test-directory/leukemia-panel-ngs-blood-2.

- Vianna, P.G.; Press, R.D.; Stehr, H.; Yang, F.; Gojenola, L.; Zehnder, J.L.; Gotlib, J. Clinical Utility of a Multi-Gene Next-Generation Sequencing Myeloid Panel in an Academic Hematology Practice. Blood 2019, 134, 1408–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Gao, S.; Gao, Q.; Patel, B.A.; Groarke, E.M.; Feng, X.; Manley, A.L.; Li, H.; Ospina Cardona, D.; Kajigaya, S. , et al. Early activation of inflammatory pathways in UBA1-mutated hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in VEXAS. Cell Rep Med 2023, 4, 101160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoneanu, A.; Rezus, II; Burlui, A. M.; Richter, P.; Bratoiu, I.; Mihai, I.R.; Macovei, L.A.; Rezus, E. Autoimmunity and Autoinflammation: Relapsing Polychondritis and VEXAS Syndrome Challenge. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaramida, A.; Obwar, S.G.; Nordstrom, A.E.H.; Ericsson, M.; Saldanha, A.; Ivanova, E.V.; Griffin, G.K.; Khan, D.H.; Belizaire, R. Sensitivity to targeted UBA1 inhibition in a myeloid cell line model of VEXAS syndrome. Blood Adv 2023, 7, 7445–7456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.F.; Chi, C.W.; Huang, Y.C.; Tsai, T.H.; Chen, Y.J. Anti-Cancer Effects of Oxygen-Atom-Modified Derivatives of Wasabi Components on Human Leukemia Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, M.J.; Lasho, T.L.; Olteanu, H.; Reichard, K.K.; Mangaonkar, A.; Warrington, K.J.; Patnaik, M.M. VEXAS syndrome: Clinical, hematologic features and a practical approach to diagnosis and management. Am J Hematol 2024, 99, 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | First Author | Year | Country | Primary diagnosis | N | Median Age, y | Range, y | Male (%) | Anemia (%) | Neutropenia (%) | Thrombocytopenia (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gurnari [8] | 2021a† | USA/Italy/France | Copper-deficiency | 2 | 57.5 | 42-73 | 50% | NA | NA | NA |

| 2 | Uchino [9] | 2021 | Japan | Copper-deficiency | 15 | 69 | 33-88 | 67% | 100% | 47% | 53% |

| 3 | Halfdanarson [10] | 2009 | USA | Copper-deficiency | 5 | 46 | 37-55 | 0% | 50% | 50% | 0% |

| 4 | Halfdanarson [11] | 2008 | USA | Copper-deficiency | 40 | 57.5 | 28-83 | 45% | 98% | 63% | 15% |

| 5 | Huff [1] | 2007 | USA | Copper-deficiency | 8 | 43.5 | 32-71 | 0% | 75% | 88% | 13% |

| 6 | Gurnari [8] | 2021b† | USA/Italy/France | MDS/AML | 21 | 66 | 49-92 | 71% | NA | NA | NA |

| 7 | Vitale [12] | 2025 | Italy/Mexico/Other‡ | VEXAS | 36 | 65 | NA | 100% | 92% | 44% | 47% |

| 8 | Johansen [13] | 2025 | Denmark | VEXAS | 16 | 74 | 51-78 | 100% | 100% | NA | 0% |

| 9 | Hadjadj [14] | 2024 | France | VEXAS | 110 | 71 | 68-79 | 99% | 100% | NA | 17% |

| 10 | Maeda [15] | 2024 | Japan | VEXAS | 89 | 69 | 62-77 | 91% | 74% | NA | 15% |

| 11 | Kusne [16] | 2024 | USA | VEXAS | 119 | 64.5 | 39-86 | 100% | 90% | NA | NA |

| 12 | Wolff [17] | 2024 | Switzerland | VEXAS | 17 | 74 | 59-77 | 100% | 100% | NA | NA |

| 13 | Beck [18] | 2023 | USA | VEXAS | 11 | 65 | 55-85 | 82% | 100% | NA | 91% |

| 14 | Mascaro [19] | 2023 | Spain | VEXAS | 42 | 67 | 52-86 | 100% | 87% | 41% | 48% |

| 15 | Hines [20] | 2023 | USA | VEXAS | 8 | 65.5 | 39-75 | 100% | 88% | NA | 100% |

| 16 | Islam [21] | 2022 | Australia | VEXAS | 3 | 67 | 67-69 | 100% | 100% | 67% | 67% |

| 17 | Mekinian [22] | 2022 | France | VEXAS | 12 | 76 | 73-78 | 100% | NA | NA | NA |

| 18 | Georgin-Lavialle [23] | 2022 | France | VEXAS | 116 | 71 | 66-76 | 96% | NA | NA | NA |

| 19 | Comont [24] | 2022 | France | VEXAS | 11 | 64 | 54-73 | 100% | 100% | NA | NA |

| 20 | Ferrada [25] | 2022 | USA/UK/Germany | VEXAS | 83 | 66 | 41-80 | 100% | 97% | NA | 83% |

| 21 | Tsuchida [26] | 2021 | Japan | VEXAS | 14 | 72 | 43-93 | 93% | 64% | NA | NA |

| 22 | Ferrada [27] | 2021 | USA/UK | VEXAS | 13 | 56 | 45-70 | 100% | 100% | NA | NA |

| 23 | Gurnari [8] | 2021c† | USA/Italy/France | VEXAS | 2 | 65.5 | 65-66 | 100% | NA | NA | NA |

| 24 | Beck [3] | 2020 | USA/UK | VEXAS | 25 | 64 | 45-80 | 100% | 96% | NA | NA |

| N | Median age, y | Male (%) | Anemia (%) | Neutropenia (%) | Thrombocytopenia (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper-deficiency | 70 | 57.5 | 41% | 92% | 61% | 22% |

| MDS/AML† | 21 | 66.0 | 71% | NA | NA | NA |

| VEXAS | 727 | 68.0 | 98% | 91% | 43% | 40% |

| Cause or risk factor | Principal mechanism(s) |

|---|---|

| Insufficient intake | Poor dietary copper (restrictive or malnourished diets; unfortified homemade enteral formulas) |

| Malabsorption | Post-gastrectomy or RYGB; extensive small-bowel disease or resection; chronic diarrhea or inflammatory bowel disease |

| Excess zinc supplementation | Gastrointestinal competition and metallothionein induction trap copper in enterocytes, increasing fecal loss (e.g., prolonged zinc therapy for Wilson disease, cirrhosis, or dialysis) |

| Chronic acid suppression (PPIs, H2-blockers) | Persistently reduced gastric acidity limits copper solubilization and intestinal absorption |

| Long-term enteral or parenteral nutrition | Trace-element omission or undersupplementation; risk rises with duration of support |

| Other gastrointestinal factors | Markedly reduced absorptive surface (short-bowel syndrome), chronic pancreatitis, or pancreatic exocrine insufficiency |

| Category | Representative disorders/exposures | Core pathophysiology | Characteristic clinical / morphologic clues | Key references |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clonal/autoinflammatory | VEXAS (UBA1) | Defective ubiquitylation; endoplasmic-reticulum stress and chronic inflammation | Numerous rounded, lipid-poor vacuoles in early myeloid and erythroid precursors; relapsing chondritis; Sweet-like rash | [3] |

| Nutritional/metabolic | Copper-deficiency, zinc excess, folate/B12 /B6 deficiency, ethanol, lead | Mitochondrial or ER dysfunction caused by trace-element imbalance or toxin | Vacuoles disappear after copper repletion or ethanol abstinence; increased zinc-to-copper ratio; macro-ovalocytes in vitamin deficiencies | [1,33,34] |

| Drug/toxin | Chloramphenicol, linezolid, methotrexate, gilteritinib, erythropoietin-stimulating agents, benzene, arsenic, isoniazid, imatinib, azacitidine, high-dose cytotoxic chemotherapy | Inhibition of mitochondrial protein synthesis, direct marrow injury, or pyridoxine depletion (isoniazid) | Vacuoles regress after drug withdrawal; in isoniazid toxicity: ring sideroblasts and vacuolated late erythroblasts reversible with pyridoxine | [34,35,36] |

| Myeloid neoplasms | MDS, AML, therapy-related MDS/AML, MDS/MPN overlap | Abortive autophagy and reactive-oxygen accumulation driven by high-risk cytogenetic lesions | More than 20% vacuolated blasts is associated with poor induction response; monosomy 7 or complex karyotype common | [37,38,39,40] |

| Myeloproliferative spectrum | Primary myelofibrosis, CMML, MDS/MPN RS-T | Persistent DNA-damage signaling | Chronic cytopenia with dysplasia; leukoerythroblastosis; marrow fibrosis; occasional vacuolization, sometimes in overlapping inflammatory syndromes (e.g., VEXAS) | [3,34] |

| Inherited marrow-failure/sideroblastic | Shwachman–Diamond, SIFD, Pearson, Kearns–Sayre, Menkes, telomere disorders | Ribosome or iron–sulfur-cluster biogenesis defects | Early-onset cytopenia, pancreatic insufficiency, telomere shortening; NGS panel diagnostic | [34,41] |

| Inherited marrow-failure/congenital neutropenia | Severe congenital neutropenia (SRP54) | Dysfunction of SRP54 GTPase; ER stress and impaired granulopoiesis | Early-onset profound neutropenia with promyelocyte arrest; numerous vacuolated myeloblasts/promyelocytes | [42] |

| Inherited lysosomal/autophagy defects | Chediak–Higashi (CHS: LYST), Danon disease (LAMP2) | Defective lysosomal trafficking or membrane proteins; impaired autophagy with giant vacuoles | CHS: partial albinism, neutropenia, giant azurophilic granules in precursors / platelets; Danon: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, skeletal myopathy, intellectual disability, enlarged vacuolated lysosomes in marrow precursors | [31,43] |

| Immune/infectious | infectious, Severe aplastic anemia, autoimmune hepatitis cytopenia, parvovirus B19 pure red-cell aplasia, secondary HLH | Marrow suppression mediated by interferon-γ and TNF-α | Profound reticulocytopenia; ferritin > 10 000 ng/mL; elevated soluble IL-2 receptor | [44,45] |

| Miscellaneous/artifact | Delayed slide preparation or prolonged room-temperature storage† | Degenerative cytoplasmic change occurring ex vivo | A repeat smear prepared within minutes eliminates vacuoles | [34] |

| Domain | Typical findings suggestive of VEXAS |

|---|---|

| Constitutional/inflammatory | Persistent fever, drenching sweats, weight loss, markedly elevated C-reactive protein or ferritin despite high-dose corticosteroids |

| Dermatologic | Neutrophilic dermatoses such as Sweet syndrome, vasculitic purpura, livedo reticularis, auricular or nasal chondritis-like erythema |

| Cartilage and joints | Relapsing polychondritis, inflammatory arthritis, costochondritis |

| Pulmonary | Sterile interstitial or organizing pneumonitis, alveolitis, exudative pleural effusions |

| Hematologic | Macrocytic anemia, thrombocytopenia or pancytopenia, cytoplasmic vacuoles in erythroid and myeloid precursors |

| Thrombotic/vasculitic | Unprovoked deep-vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, systemic or cutaneous vasculitis, cerebral vasculitic events |

| Treatment pattern | Transient steroid response; refractoriness to conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; dependence on high-dose steroids or Janus kinase inhibitors |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).