1. Summary

This study introduces an extended cross-country dataset on educational quality, spanning 101 countries, from 1970 to 2023. The dataset harmonizes mathematics and science test scores for secondary students from major international assessments—Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), and the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA)—and imputes missing values using two methods: (i) linear interpolation and (ii) machine learning prediction based on the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO), incorporating a diverse set of economic and educational indicators.

Key features of the dataset include:

A balanced panel of harmonized test scores for 15-year-olds, aligned with the TIMSS.

Annual educational quality indicators for the 15–19 age cohort, spanning 1970–2023.

Educational quality indexes for the working-age population (ages 15–64) for 2015 and 2023, incorporating population weights and estimated returns to test scores.

This dataset supports cross-country research on education, human capital, and development by offering enhanced temporal coverage and broader country representation. It complements existing data sources and is publicly available for further use.

2. Data Description

The dataset is available in two formats: CSV and Stata (. dta), and includes panel data spanning 101 countries from 1970 to 2023. It comprises three main panel datasets.

Test Score (1970–2023): Includes harmonized and imputed test scores at approximately four-year intervals for 15-year-olds using two estimation methods.

Annual Educational Quality for Ages 15–19 (1970–2023): Provides yearly measures for the 15–19 cohort constructed from harmonized test score estimates.

Working-Age Educational Quality Index (2015, 2023): Aggregated indicators for the 15–64 population, incorporating population weights and estimated wage return variables. The dataset also includes identifiers (Country Name, ISO3 code, Year) and an indicator for the availability of original observed test scores.

Table 1 summarizes the key variables in the dataset.

The variables Tscore_INT and Tscore_ML represent harmonized test scores derived through interpolation and machine learning, respectively. A harmonized dataset of test score for 15-year-olds from 1970 to 2023 was constructed using original observed data from international assessments, including TIMSS, PISA, and earlier IEA studies. To construct a balanced panel, 581 missing values out of 1,212 potential country–year observations were imputed using two methods: linear interpolation and LASSO regression based on economic and education predictors.

The variables Tscore1519_INT and Tscore1519_ML represent annual educational quality indicators for the 15–19 age cohort. The educational quality indexes (Q_INT and Q_ML) for the working-age population (ages 15–64) are derived from cohort-level scores.

3. Methods

3.1. Data on International Test Scores

The dataset compiles international assessment results in mathematics and science for secondary students across 101 countries from 1970 to 2023 (

Table 2). The primary data sources are TIMSS and PISA.

Launched in 1995, the TIMSS assesses mathematics and science achievement at Grades 4 and 8 every four years. Grade 8 scores are used as proxy for secondary school quality. The 2023 cycle included 72 participating countries and regional benchmarks.

First administered in 2000, PISA evaluates reading, mathematics, and science literacy among 15-year-olds. The dataset includes eight PISA waves through 2022, covering 81 countries and territories.

To extend coverage to earlier decades, the study incorporates results from the IEA’s First and Second International Mathematics Studies and the Second International Science Study conducted during the 1970s and 1980s, as well as the International Assessment of Educational Progress (1988, 1990–1991).

The data excluded countries from the final sample based on two criteria: (i) the absence of nationally representative samples (e.g., China and India) and (ii) missing key national indicators in the World Bank’s economic and education statistics, which are essential for panel construction and data imputation.

The analysis covers 12 key assessment years between 1970 and 2023 (1970, 1980, 1984, 1990, 1995, 1999, 2003, 2007, 2011, 2015, 2019, and 2023), yielding an unbalanced panel of 101 countries, with 805 mathematics and 828 science observations. TIMSS served as the reference metric, with all scores anchored to its 1995 scale (mean = 500, SD = 100). PISA scores were mapped onto this scale using equi-percentile linking [

1], aligning cumulative distributions across assessments. This approach is supported by strong cross-country correlations between TIMSS and PISA: 0.88 for mathematics and 0.91 for science.

To extend comparability to pre-1995 assessments (IEA and IAEP), US-based National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores were employed as a temporal anchor, leveraging the US’ consistent participation and applying variance equalization across Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.

After the harmonization procedures were completed, the average achievement score for each country–year was computed as the simple mean of the mathematics and science scores. In cases where only one participant was available, that score was used as the representative achievement value for that year.

Of the 1,212 potential country–year observations (101 countries × 12 years), 631 were observed, leaving 581 missing values (48%). These missing values were imputed using a combination of linear interpolation and LASSO regression based on economic and educational predictors. The two methods yielded highly consistent estimates (correlation = 0.967), enabling the construction of a balanced panel.

The LASSO model draws on 501 fully observed predictors from the World Bank’s Development Indicators and Education Statistics [

2,

3], selected from an initial pool of 3,442 variables. To improve predictive accuracy, existing test score data were incorporated—specifically, country-level mean scores and the nearest available assessment for each year

t, prioritizing earlier observations in cases of equidistant data points. This approach adheres to standard machine learning practices [

4,

5]. In line with standard protocols, the data were split into training (80%) and validation (20%) sets, and a grid search with tenfold cross-validation was applied to minimize Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE). The final model, trained on the full dataset, achieves an RMSE of 15.7 and an out-of-sample R² of 0.905.

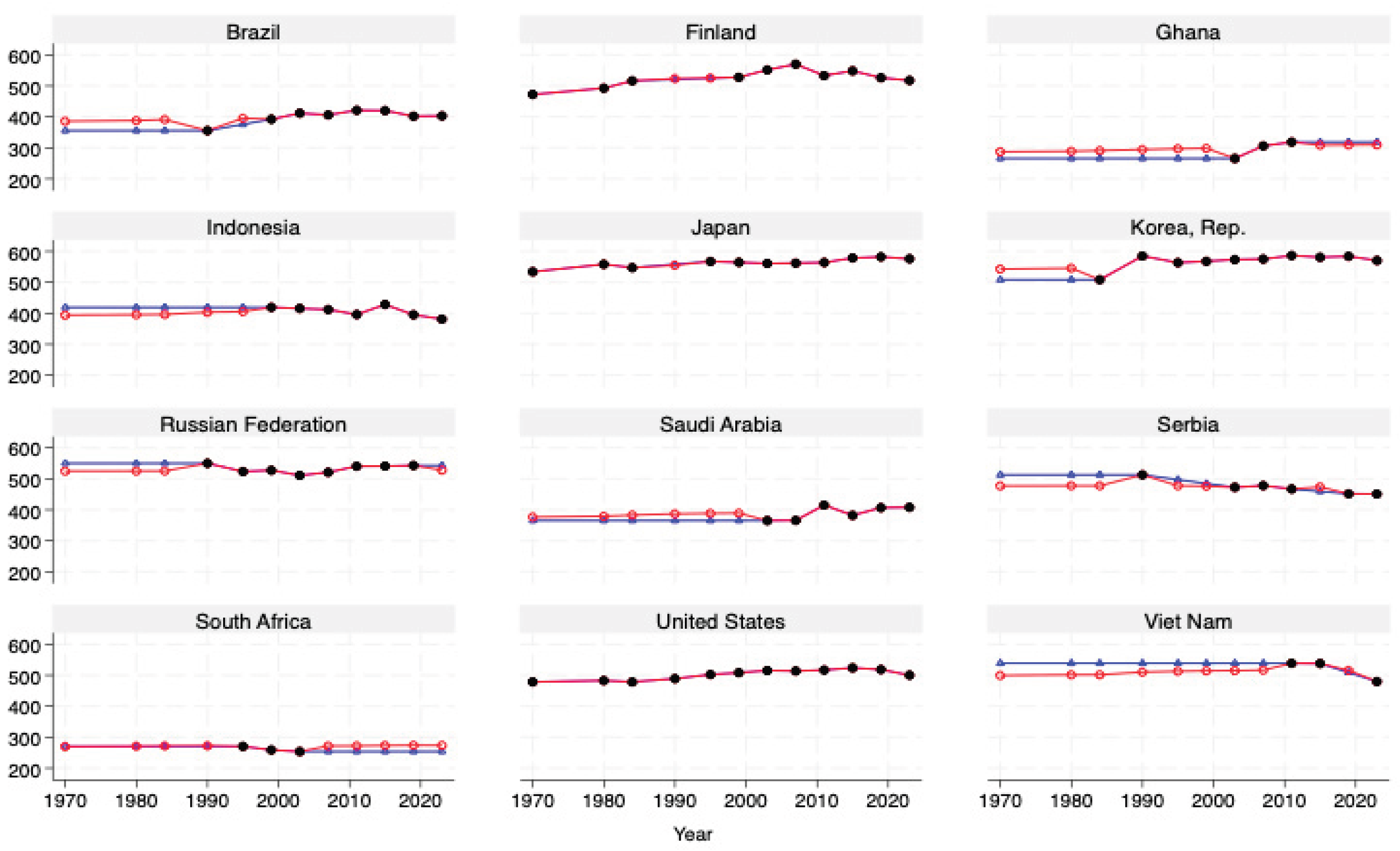

Figure 1 depicts the evolution of test scores from 1970 to 2023 for the 12 of 101 selected countries. The figure distinguishes between three data sources: solid black dots represent harmonized scores derived from original observations from international assessments (including TIMSS, PISA, and earlier IEA studies); hollow blue triangles indicate interpolation-based estimates; and hollow red circles denote machine-learning estimates generated using LASSO regression.

The selected countries span a broad range of geographic regions and development stages—from high-performing East Asian economies, such as Japan and the Republic of Korea, which consistently maintain average scores above 500, to lower-performing countries, such as Ghana and South Africa, which start from a lower baseline. The figure highlights diverse national trajectories: Japan demonstrates consistently high performance, while Brazil shows gradual improvement beginning in the 1990s. In contrast, countries such as Indonesia and Finland displayed declining trends in recent years. The interpolated and machine learning estimates align closely for most countries; however, discrepancies emerge in a few cases—notably in Ghana and Serbia—where early year extrapolations differ between the two approaches.

3.2. Constructing a Measure of Educational Quality

Annual educational quality data for the 15–19 age group were constructed based on the estimated test scores of 15-year-olds. Using the selected estimation methods—interpolation, and machine learning—these values were labeled as Tscore1519_INT and Tscore1519_ML, respectively. The study assumes that educational quality in year t corresponds to the test scores of 15-year-olds assessed in that year, aligning with the design of international assessments that routinely evaluate cognitive skills at age 15. For example, the educational quality of the 15–19 age group in 2023 was calculated as the population-weighted average of annual educational quality from 2019 to 2023. Since assessments are typically conducted at four-year intervals, interpolation was employed to generate an annual dataset.

In addition, an index of educational quality was constructed for the working-age population,

, defined as

where a is the age groups (15–19, 20–24, ..., 60-64);

is the population share in age group

a at time

t,

is the normalized test score for group

a at time

t and corresponds to the normalized Tscore1519.

indicates the return to “normalized” test score, which is set at 9.5%, based on the estimated wage return to one standard deviation in test score (Lee and Lee [

6],

Table 2, Column 2).

The methodology relies on two key assumptions designed to ensure empirical feasibility, given the structure of international assessment data.

First, it is assumed that remains consistent across cohorts and countries.

Second, a uniform quality score is assigned to all individuals within a cohort, regardless of their educational track. For example, members of the 15–19 age group in 2023 received the same score irrespective of whether they attended primary, secondary, or tertiary institutions. This implies that the cohort assessed at age 15 in 2015 is assumed to have received the same quality of education throughout their schooling, both prior to and following the assessment.

A systematic approach was used to link test scores with age cohorts across different time periods. This methodology maintains consistent temporal relationships while accounting for cohort progression. For example, the 15–19 age cohort in 2015 (20–24 in 2020) incorporated the test scores from 2011–2015.

4. Data Analysis

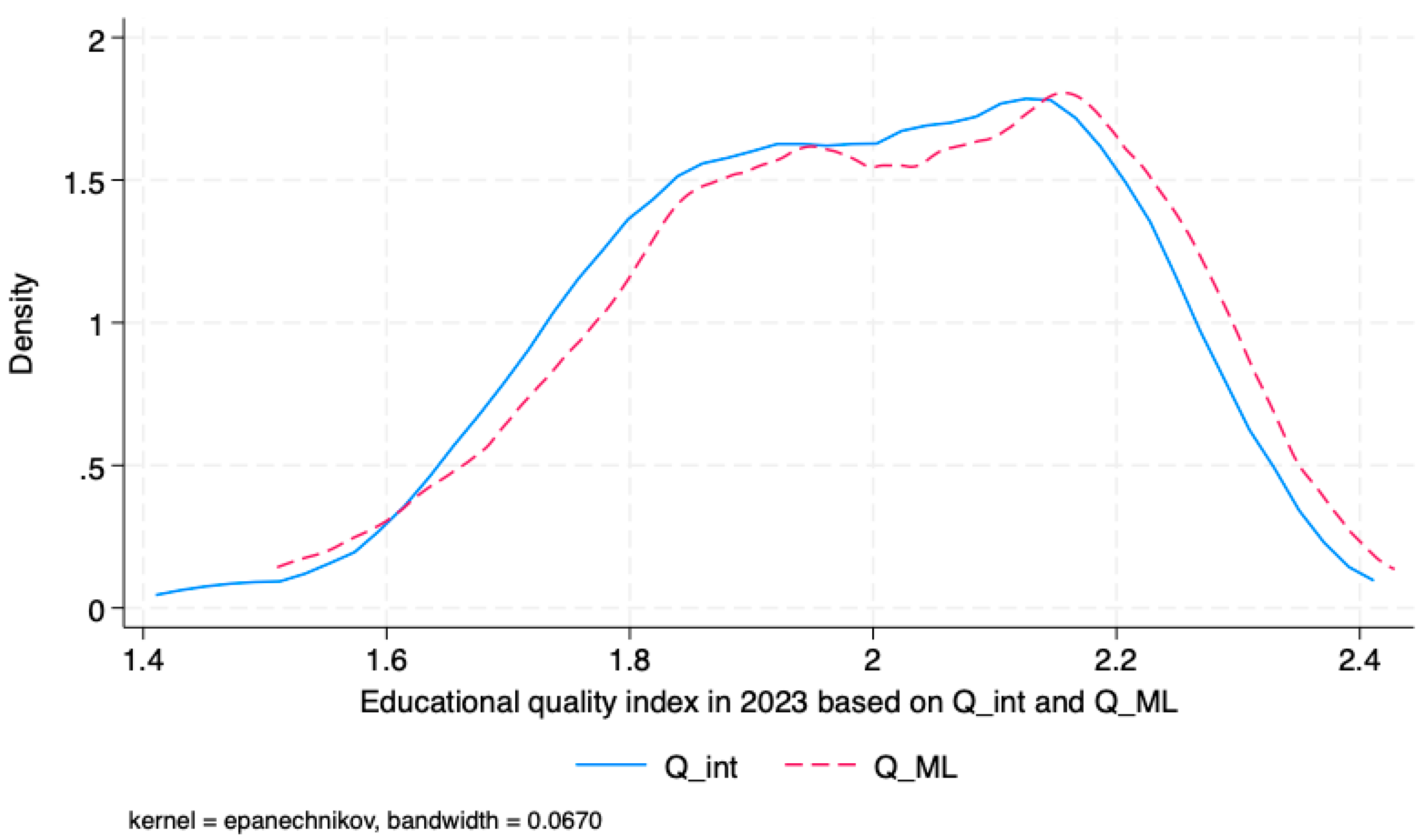

Figure 2 presents the distribution of educational quality index for the working-age population across 101 countries in 2023, comparing the estimates derived from the interpolation and machine learning approaches. Both methods yield broadly similar distributions, each exhibiting a roughly symmetric shape centered around a value close to 2.0.

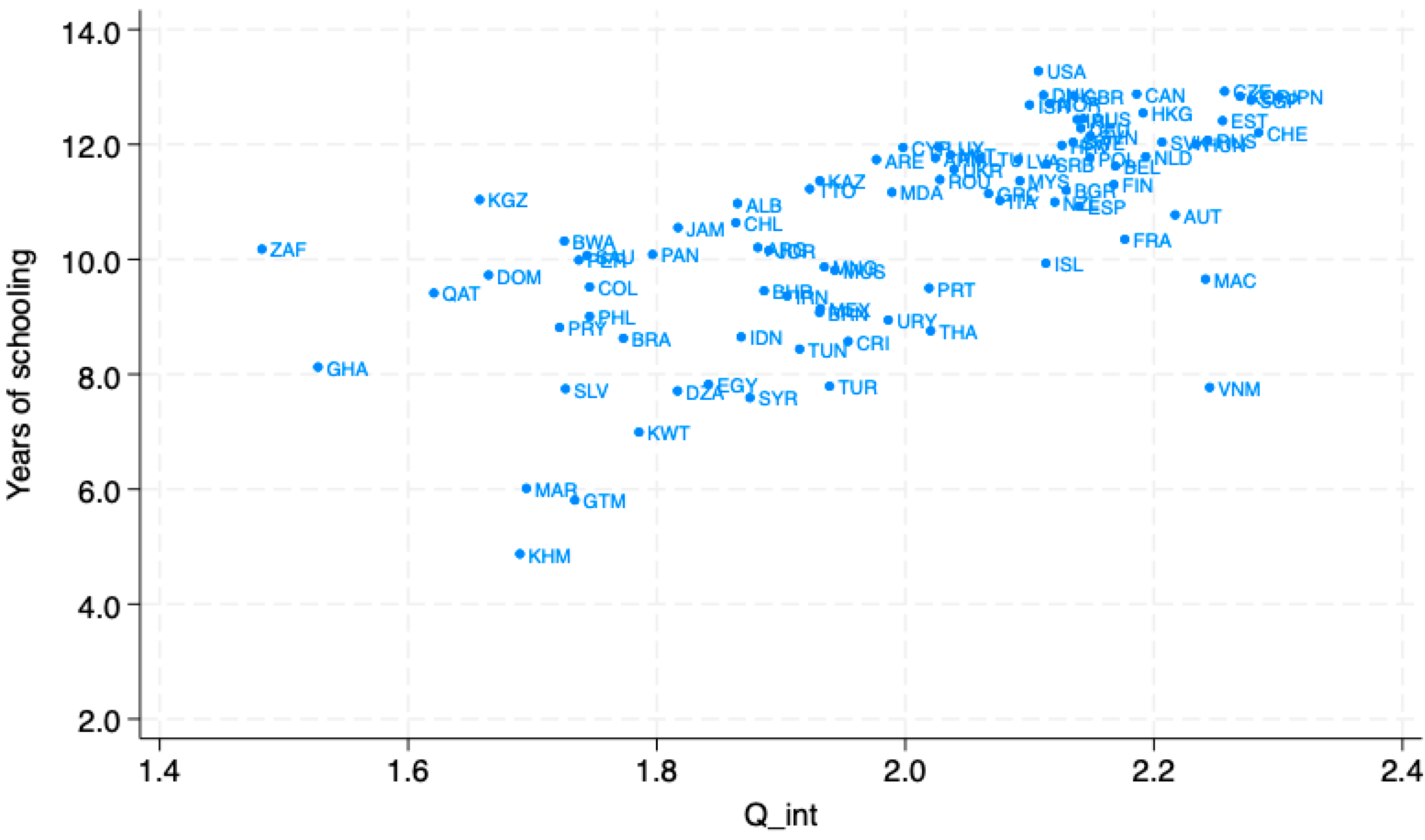

Figure 3 plots educational quality, measured by the Q interpolation index, against educational quantity, represented by the average years of schooling among adults aged 25–64, based on Barro and Lee [

7], for the year 2015. The scatterplot reveals a generally positive relationship between the two measures (correlation = 0.67), indicating that countries with higher educational quality also tend to exhibit longer average durations of schooling.

The upper-right quadrant features the strongest performers, countries that combine high educational quality with extensive schooling. The US exemplifies this pattern (13.33 years; Q = 2.11), along with Japan (12.83 years; Q = 2.30), the Republic of Korea (12.84 years; Q = 2.27), and Singapore (12.77 years; Q = 2.28). Germany (12.28 years; Q = 2.14) and other European countries also cluster in this high-performance group, reflecting strong systems in both educational access and learning outcomes.

In contrast, some countries exhibit substantial educational quantity, but comparatively low quality. South Africa stands out with 10.18 years of schooling, but the lowest Q score in the dataset (1.48) indicating persistent challenges in translating schooling into learning. Qatar exhibited a similar pattern, with 9.41 years of schooling and a Q-score of 1.62.

The lower-left quadrant includes countries grappling with the dual challenge of limited educational access and low quality. Ghana (8.13 years; Q = 1.53), and Cambodia (4.87 years; Q = 1.69) exemplify this group, where resource constraints impede both school participation and learning outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-W. L.; methodology, H. L. and J.-W. L.; software, H.L.; validation, H. L. and J.-W. L. formal analysis: H. L. and J. W. L. investigation, H. L. and J.-W. L.; data curation, H. L.; writing—original draft preparation, H. L. and J.-W. L. writing —review and editing, H. L. and J. W. L.; visualization, H. L.; supervision, J.-W. L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the findings of this study are publicly available at

http://www.barrolee.com. The repository provides (i) the test-score database with original and imputed international assessment scores for 1970–2023, (ii) annual educational-quality series for the 15–19 age cohort (1970–2023), and (iii) educational-quality indices for the working-age population (ages 15–64) for 2015 and 2023. The data were provided under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0, International (CC BY 4.0) license, allowing for unrestricted use with appropriate attribution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PISA |

Programme for International Student Assessment |

| TIMSS |

Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study |

| IEA |

International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement |

| CSV |

Comma Separated Values |

| IAEP |

International Assessment of Educational Progress |

| LASSO |

Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator |

| OECD |

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| NCES |

National Center for Education Statistics |

| RMSE |

Root Mean Squared Error |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| NAEP |

National Assessment of Educational Progress |

| UN |

United Nations |

References

- Braun, H.I.; Holland, P.W. Observed-score test equating: A mathematical analysis of some ETS equating procedures. In Test Equating, Holland, PW, Rubin, D.B., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, 1982; pp. 9–49. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank; World Development Indicators, 2025. Available online: https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators (accessed on 14 Jun 2025).

- World Bank. Education statistics, 2025. Available online: https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/education-statistics (accessed on 14 Jun 2025).

- Che, Z.; Purushotham, S.; Cho, K.; Sontag, D.; Liu, Y. Recurrent neural networks for multivariate time series with missing values. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, R.J.; Rubin, D.B. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data, 3rd ed.; New York: John Wiley & Sons; United States, 2019.

- Lee, H.; Lee, J.W. Educational quality and disparities in income and growth across countries. J. Econ. Growth 2024, 29, 361–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R.J.; Lee, J.W. A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950–2010. J. Dev. Econ. 2013, 104, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).