2. Case Presentation

A 57-year-old Irish gentleman with a pre-existing background history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and a 60 pack year smoking history presented to hospital with a left-sided painless neck mass, dry cough and decreased appetite. Notably, this was directly preceded by a dental procedure within the previous month. The patient also reported that the timing of symptom onset was accompanied by left-sided dental pain, the side on which the recent procedure had taken place. On examination a firm, fixed, left-sided non-tender neck mass was appreciable, however the remainder of the physical examination on admission was unremarkable. The patient denied any other constitutional symptoms such as weight loss, lethargy, night sweats etc.

Haematological investigations on admission revealed a normocytic, normochromic anaemia, with a haemoglobin of 12.5g/dL (range 14-18). The white blood cell count was marginally elevated at 10.2 x 10 9/L (4-10), however neutrophil, lymphocyte and eosinophil values were within normal ranges. Urea and electrolytes were unremarkable. The ESR was notably raised however, at over 120mm/HR (<14). CRP was assessed two days later, and found to be 58.5mg/L (<10). No microorganisms were grown via peripheral blood cultures.

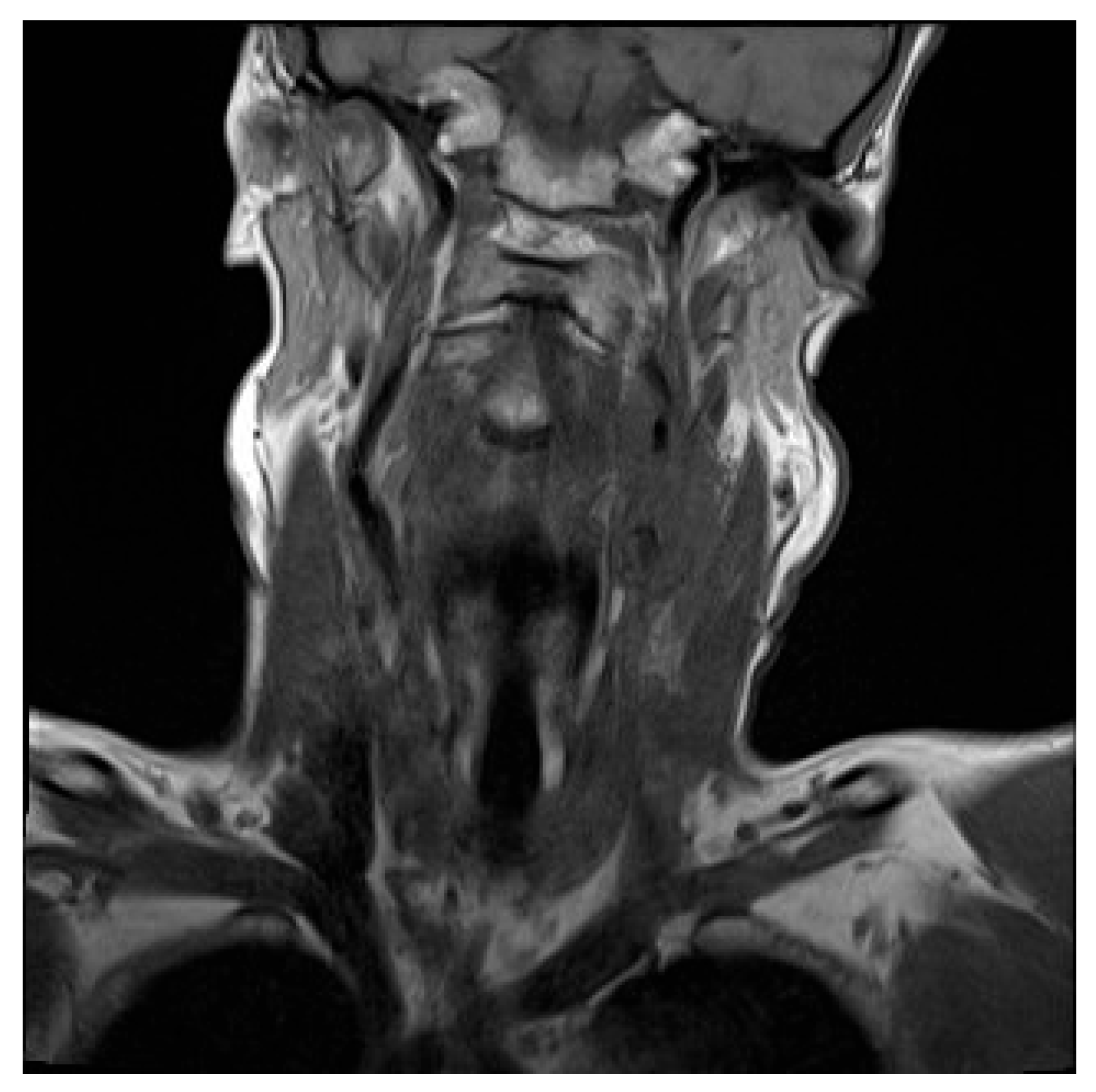

Initial contrast-enhanced CT neck revealed a large left-sided neck mass, measuring 3.5 by 4.6cm. Further characterisation by contrast-enhanced MRI showed the neck mass to be encasing the upper common carotid artery, the carotid bulb and the internal carotid artery on the left side. This mass was also compressing the left internal jugular vein, occluding it and resulting in thrombosis (

Figure 1).

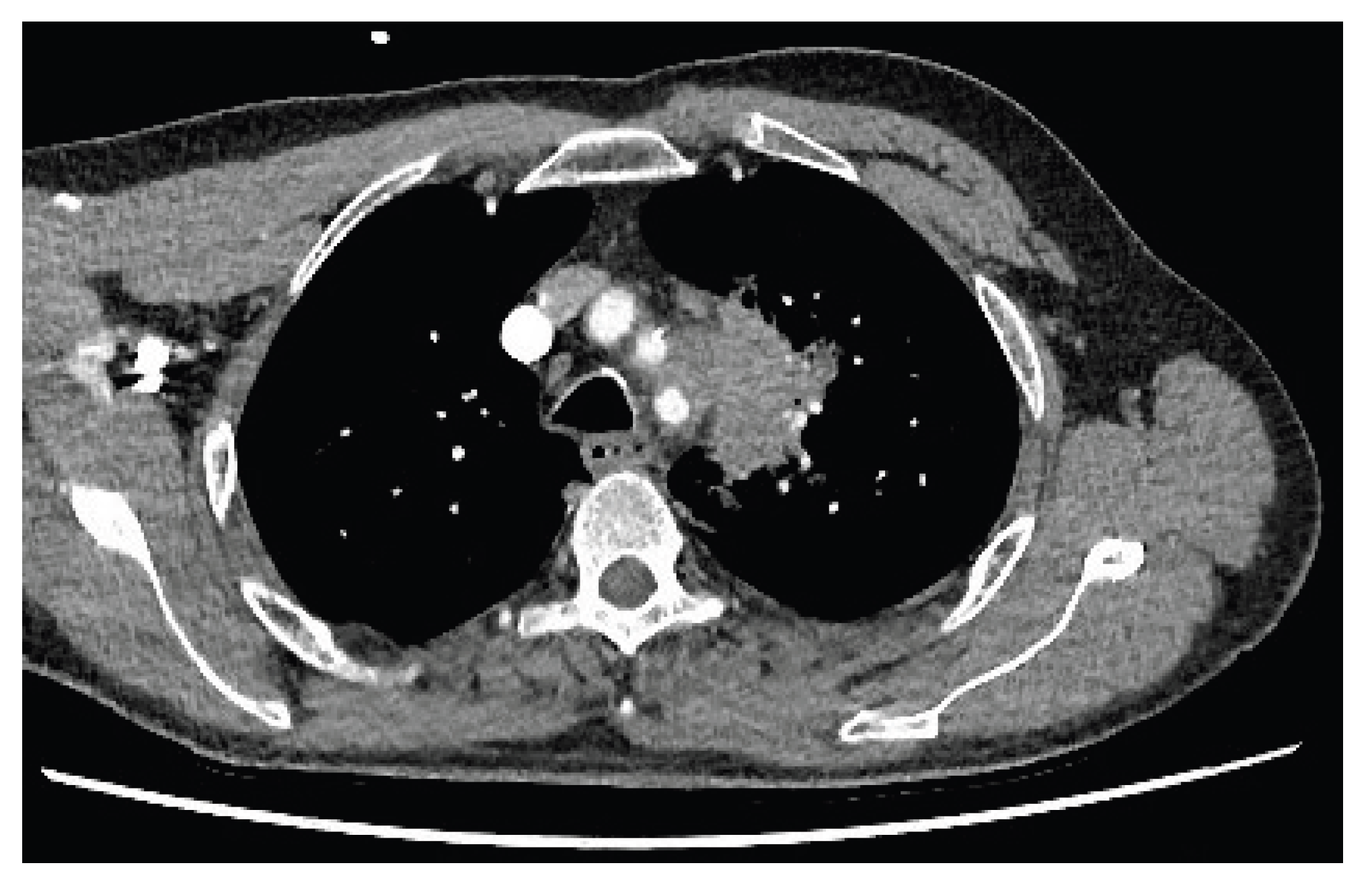

During further investigation, contrast-enhanced CT of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis revealed a 5.5cm mass in the upper lobe of the left lung (

Figure 2). Notably this mass appeared to invade through tissue planes, encroaching into the mediastinum and involving the arch and proximal descending aorta. There were no other lung findings or suspicious bony lesions.

Ultrasound-guided biopsies of the neck mass subsequently showed no evidence of neoplastic disease. Biopsied lymph nodes were also benign. Furthermore, a fibrous tissue segment on the biopsy showed reactive fibroblastic proliferation, with elongated spindle stromal cells (which were negative for cytokeratin, TTF-1, CK 56 and p63 on immunohistochemistry), along with mixed acute and chronic inflammatory cells.

CT-guided percutaneous biopsy of the lung mass was then carried out. As before, the sections showed no malignancy. Evidence of both acute and chronic inflammatory cells was again seen, with fibroblast-like spindle cell proliferation. This fibro-inflammatory picture was noted to be similar in appearance to the recent neck biopsy. Notably however, gram positive rods were isolated from the lung biopsy tissue. Initially described as organisms resembling Actinomyces, they were later identified as the Cellulosimicrobium species using 16S rRNA gene sequencing analysis.

Differential Diagnosis: Given the complex nature of this case, the differential diagnosis was broad and constantly evolving over time. On initial presentation, prior to biopsy the initial impression was of a likely metastatic lung neoplasm. Indeed, the possibility of two separate neoplastic processes in both the neck and lung was also actively considered. The inability to identify evidence of malignancy on multiple biopsies necessitated the consideration of alternative diagnoses.

Due to the presenting neck mass, combined with the subsequent jugular vein occlusion on imaging, Lemierres disease was also briefly considered; discarded due to the presence of a concomitant lung mass as well as the inability to isolate the classically causative anaerobic organism, Fusobacterium necrophorum. Other diagnoses such as sarcoidosis were also outruled during the course of work-up (In the case of sarcoidosis largely due to the absence of granulomatous disease on multiple biopsies). Indeed, prior to the isolation of Cellulosimicrobium on lung biopsy, a variety of other potential bacterial organisms, such as Mycobacterium Tuberculosis, Nocardia and Actinomyces were also considered. Fungal pathology such as coccidioiodomycosis and blastomycosis were also in the differential, disregarded after an inability to isolate on numerous cultures, as well as biopsies.

An important differential to acknowledge is that of inflammatory pseudotumour (IPT). IPTs represent a rare heterogenous disease process known by several terms, including inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour, pseudosarcoma, myxoid hamartoma, fibrous xanthoma, plasma cell granuloma and inflammatory myofibrohistiocytic proliferation [

5]. The cause is unknown, and multiple hypotheses attempt to explain it’s aetiology. These include attributing it to a true primary neoplasm, an immune-mediated response to various infectious organisms (eg EBV,

Mycobacterium,

Nocardia, Actinomyces,

Escherichia coli,

Klebsiella, HIV) [

5,

6], inflammatory response to a causative low-grade neoplasm [

7], trauma, and IgG4-associated disease [

6]. Histopathological findings of these space-occupying lesions are varied, including spindle cell proliferation, acute and chronic inflammatory changes (eg lymphocytes and plasma cells), myofibroblasts, fibroblasts, collagen and granulation tissue [

5,

6,

7,

8]. IPTs can vary widely in their location, but are largely found in the viscera or soft tissues [

7].

Another inflammatory condition considered in the differential was that of IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD). This fibroinflammatory process can manifest in multiple systems and the majority of cases see multiple focal areas involved at the time of presentation [

9] Specific to this case, IgG4-RD can manifest as lung lesions, some of which present as solid lung nodules [

10,

11]. Although it should be noted that the pancreas and salivary glands are the most commonly affected sites [

9]. While fibroblastic and spindle cell proliferation was indeed seen, many associated features such as obliterative phlebitis, storiform pattern fibroblastic proliferation, an abnormally raised ratio of IgG4-positive cells to IgG-positive cells and lymphoplasmocytic inflammation with eosinophil abundance were not reported on histopathological examination. Furthermore, serum concentrations of IgG4 were not noted to be abnormally elevated.

Management and Follow up: Given the complex nature of this presentation, management of this case was ever-evolving with the differential and was multi-disciplinary in nature. Biopsying required the consultation of numerous services such as otolaryngology and radiology. Multiple sub-specialised pathologists consulted on the interpretation of biopsies.

Microbiological input was a key factor for ongoing guidance in this case. As the differential evolved, so too did the antibiotic regimen. Initial antibiotic therapy consisted of intravenous ceftriaxone and metronidazole when Lemierre’s was suspected. This regimen was later changed to empiric TB treatment, as well as meropenem to cover Nocardia. Following the identification of gram positive rods described as resembling Actinomyces from the lung biopsy tissue, high dose intravenous penicillins were used. This in turn coincided with the presenting neck mass decreasing in size on clinical examination. It is important to note that steroids were not administered in conjunction with this antibiotic therapy. Given the growth of gram positive rods resemblant of Actinomyces as well the invasion through tissue planes on imaging, the patient was discharged on 1g of oral amoxicillin three times daily for a year to cover Actinomyces. This was tolerated without any undue side effects. This year-long course was continued following identification of the Cellulosimicrobium species from lung biopsy tissue.

Due to compression of the left internal jugular vein by the neck mass and consequent thrombosis, haematology was closely involved in care. Initially commenced on low molecular weight heparin on admission, this was changed to 5mg apixaban twice daily for four months following discharge. This was subsequently reduced to 2.5mg twice daily and continued for six months. Follow up CT and Doppler ultrasound scans noted continued thrombosis of the external jugular vein, but that good collaterals had developed. The impression was that this vessel was chronically thrombosed and stable in nature, and so anticoagulation was discontinued.

Following discharge, the patient has remained well despite some residual neck discomfort. On clinical examination it has been noted that the neck swelling has decreased in size. This was confirmed on follow up imaging and CT Thorax also showed reduction in size of the lung mass. Follow up inflammatory markers were also shown to be reduced. The patient remains in regular outpatient follow up.

3. Discussion

The

Cellulosimicrobium species consists of gram positive, branched bacilli, known for their bright yellow-coloured colonies [

1]. It has in rare cases been attributable to pathogenesis in humans, owing to C.

funkei and C.

terrum. Literature review by Rivero et al. in 2019 identified only 43 cases of infections in humans caused by this organism (along with an additional case that they themselves describe) [

2]. Technical difficulties regarding misidentifying cultures of the species as other coryneforms (with subsequent dismissal as skin flora) may also have a part to play in the scarcity of reported cases [

4,

12]. Technological advancements such whole-genomic sequencing may lead to increases in

Cellulosimicrobium isolation going forward.

Cases of

Cellulosimicrobium tend to be foreign body-related or involve patients who are immunocomprimised [

2,

3,

4]. Rivero et al deemed 26 (60%) of their described cases to have underlying immune dysfunction [

2]. Furthermore, 29 (67%) of cases were foreign body-related [

2]. More recent literature review by Ioannou et al. identified only 40 cases of infections attributable to

Cellulosimicrobium [

13]. They also identified a large proportion of potentially foreign body-associated cases. Six (15%) of patients underwent surgery within three months of

Cellulosimicrobium isolation. Eleven (27.5%) patients had a central venous catheter in situ, 6 (15%) were receiving dialysis and 4 (10%) had cardiac valve prostheses [

13]. This is in concordance with Rivero et al. Interestingly, Ioannou et al. identified vancomycin to have the lowest rate of antimicrobial resistance (0 of 29 cases) [

13].

There is no “typical” presentation in the existing literature, and presentations include manifestations as central venous catheter-related bacteraemia, peritonitis, endocarditis, meningitis, endopthalmitis, pneumonia, soft tissue infection, osteomyelitis, suppurative arthritis, pyonephrosis, axillary abscess and bacteraemia of unknown source. Given the scarcity of existing literature and the inability to identify a similar presentation, we believe this case represents a potential novel presentation of Cellulosimicrobium pathogenesis in humans. Given the abundance of iatrogenic seeding of the organism in the existing literature, we believe this case was likely attributable to the patient’s recent dental procedure.

However, it would be remiss not to acknowledge the diagnostic uncertainty surrounding this case (discussed at length). An important highlighted differential is that of IPT. However, there are a number of reasons we have attributed the presentation to Cellulosimicrobium. First and foremost, the isolation of the organism on lung tissue biopsy. Other reasons include the timing of presentation in relation to a recently preceding dental procedure, as well as the reduction of lesion sizes, and normalisation of ESR and CRP with antibiotic therapy.

Indeed, even if this presentation is attributable to IPT, as mentioned previously one hypothesis regarding the aetiology of IPTs is a response to various infectious organisms. Suspected organisms include Actinomyces, to which Cellulosimicrobium is closely related, belonging to the Actinomycetales order. This may therefore represent a case of Cellulosimicrobium-related IPT (of which we have been unable to find a documented case of in the existing literature).

Rising numbers of immunocompromised patients in the community, as well as increasing usage of prostheses, long-term catheters etc may pose a risk of increasing numbers of Cellulosimicrobium infections in humans going forward. Thus our case adds to the small body of existing literature.