1. Introduction

Cancer pain is a complex and multifaceted symptom affecting about 40–70% of patients with cancer (1,2). A recent meta-analysis by Snijders et al. showed a decline in the prevalence and severity of pain over the past decade. However, the prevalence remains high (54.6%), especially in advanced, metastatic, and terminal cancer patients (1). Pain continues to be the most prevalent symptom during and after the cancer treatment and may be debilitating up to three months after curative treatment. However, patients who are not eligible for anti-cancer treatments frequently report moderate to severe pain (3). Cancer pain significantly affects the patient’s quality of life, leading to decreased functionality, emotional distress, cognitive dysfunction, and reduced survival rates (1,3,4,5).

A cohort study by Perez et al. estimated the prevalence of pain in long-term cancer survivors and found that at least 40% of cancer survivors had persistent pain. Pain was neuropathic in at least half of cancer survivors and a frequent health determinant, causing sleep disorders, mood alteration, and fatigue (6).

“We can ignore even pleasure. But pain insists upon being attended to.” -C.S. Lewis

Managing cancer pain is critical to improving the quality of life and survival rates. Cancer pain management has evolved significantly over the decades due to increased awareness and knowledge, improved pain assessment tools, a multidisciplinary approach to cancer, and novel treatment strategies (1).

This review provides an in-depth analysis of the historical evolution of cancer pain, its pathophysiology and types, contemporary assessment techniques, conventional and advanced treatment modalities, and discusses how a personalized treatment approach can improve outcomes and patient experiences.

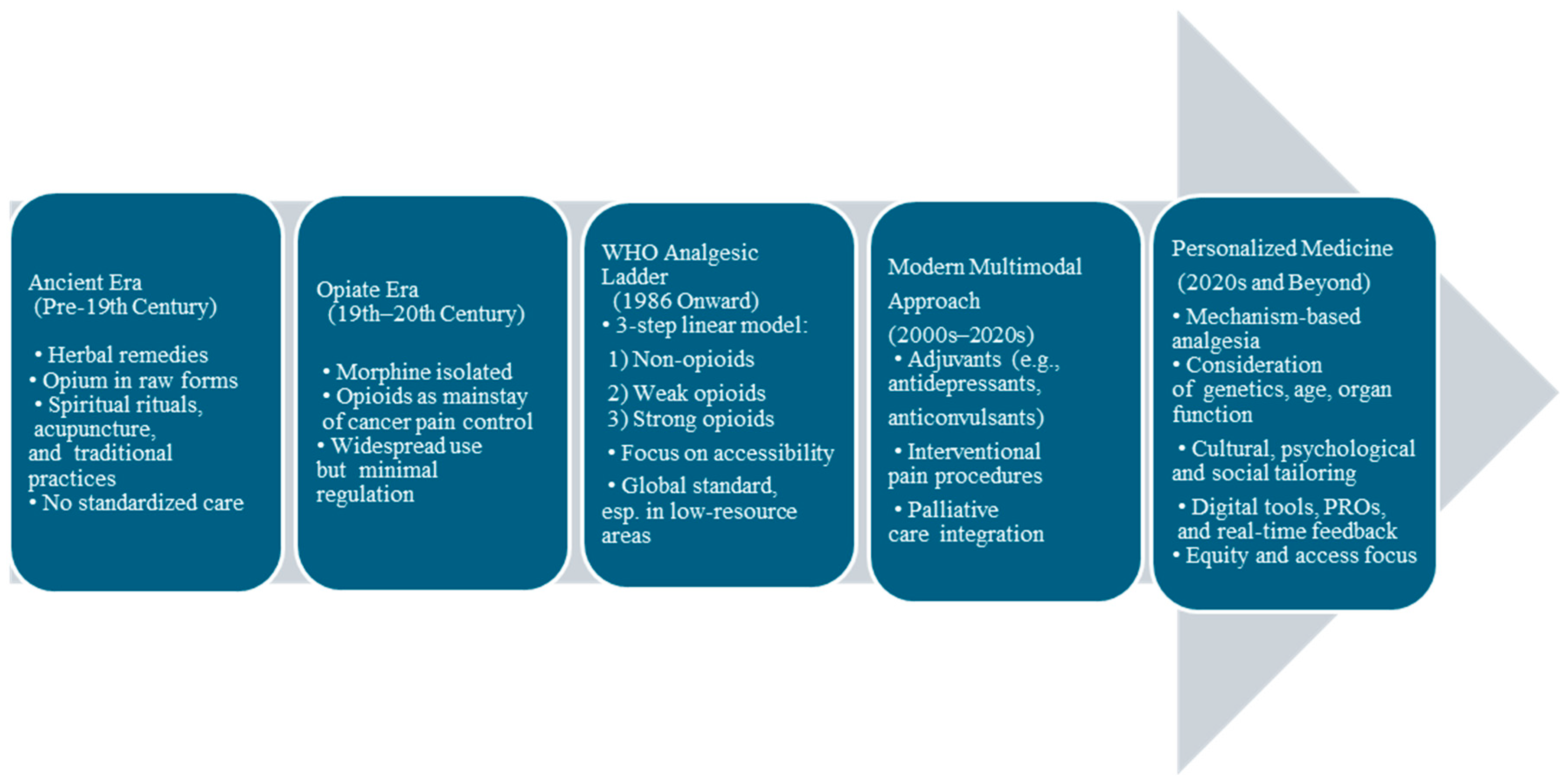

2. The Evolution of Cancer Pain: From Tradition to Personalization (Figure 1)

Historically, cancer pain was overlooked. During the Middle Ages, it was considered a punishment that was managed through spiritual rituals, acupuncture, or herbal remedies.

The 19th century marked a turning point with the isolation of morphine in 1806. To this day, morphine remains the single most widely used analgesic medication on earth and appears on the list of the World Health Organization’s essential medicines (7). In 1883, came heroine, which was sold over the counter for pain control (8). Opioids quickly became the drugs of choice to manage pain, induce sleep, improve mood, and manage mental health conditions. This led to their widespread use, proliferation of side effects, morbidity, potentially life-threatening respiratory depression, and opioid addiction.

In 1914, the United States government recognized the potential for opioid abuse and misuse and approved the Harrison Narcotics Act, which prohibited the use of prescription opioids for nonmedical use (9).

The opioid crisis started in the mid-to-late 1990s. It was characterized by three waves: overdose deaths from prescription opioids began rising in 1996 due to increased prescription rates and the introduction of OxyContin. Heroin contributed to a second wave in 2010, especially severe in the Northeast and South census regions. The prevalence of synthetic opioids, primarily illicit fentanyl, drove a sharp third wave commencing in 2013. By the time the crisis was declared a public health emergency on October 26, 2017, opioid overdoses had already claimed hundreds of thousands of lives (10).

Cancer pain management was complicated by the opioid crisis, with mounting uncertainty about how to provide appropriate management of pain while also balancing risks for opioid misuse in cancer survivors, leading to a careful assessment of pain as well as risk factors for substance use disorders by clinicians (11).

The World Health Organization’s Analgesic Ladder, introduced in 1986, became a cornerstone for cancer pain management, promoting a stepwise approach to pain relief based on severity using non-opioids, weak opioids, and potent opioids that significantly improved palliative cancer care (12).

Further innovations have occurred in the late 20th and 21st centuries, including patient-controlled analgesia, nerve blocks, neuromodulation, targeted therapies, integrative approaches, and an updated WHO ladder incorporating a fourth step. The field of palliative care has expanded to include a more holistic approach, focusing on the physical, emotional, and psychological aspects of cancer pain, making it a personalized experience for every patient (13,14).

Figure 1.

Evolution of Cancer Pain Management.

Figure 1.

Evolution of Cancer Pain Management.

3. Pathophysiology and Types of Cancer Pain.

Cancer pain is multifactorial, involving nociceptive (somatic or visceral) pain, neuropathic pain, and/or a mix of both (15,16,17).

3.1. Nociceptive Pain

Nociceptive pain arises from the activation of nociceptors due to tissue damage, commonly caused by tumor invasion into bones, muscles, or visceral organs.

Bone metastases are the most common cause of cancer-related somatic pain and are associated with poor prognosis and survival (18). Approximately 75% of patients with advanced cancer experience bone pain. Cancer-induced bone pain (CIBP) is a mixed-mechanism pain involving inflammatory, neuropathic, ischemic, and cancer-specific mechanisms (19). Metastasis to bone disrupts skeletal homeostasis by disturbing the balance between osteoblastic bone formation and osteoclast-mediated bone destruction (20). Bone pain has been correlated with osteoclast-mediated bone resorption. Tumor cells release endothelin (ET), stimulating the proliferation of osteoblasts. Activated osteoblasts release receptor activators of nuclear factor-kappa-Β ligand (RANKL), which signal osteoclast proliferation and maturation to enhance osteoclast-mediated bone matrix destruction. Osteoclasts generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and acidosis by releasing protons, resulting in the activation of various receptors and ligand-gated ion channels like P2X receptors, transient receptor potential V1 receptors, and acid-sensing ion channels type 3 expressed on bone-innervating sensory neurons. Tumor cells, stromal cells, and activated immune cells release a variety of mediators, including endothelin, nerve growth factors, protons, and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and prostaglandin (PG)E2, that stimulate nociceptors (21). The acidic microenvironment is thought to be a key mechanism driving bone pain as bone is a hypoxic tissue, leading to enhanced cancer-induced acidosis (22,23).

Nociceptors in the cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary systems, as well as the head and neck, mediate visceral pain. Tumors can cause irritation of the mucosal and serosal surfaces, torsion of the mesentery, and distention or contraction of a hollow viscus that can stimulate nociceptors or perineural invasion. Visceral pain is often diffuse and poorly localized. Due to the convergence of visceral and somatic inputs into the central nervous system, visceral pain can be referred to as somatic pain. Visceral pain can also trigger autonomic nerve signals and can be associated with nausea, diaphoresis, or vasoconstriction (24,25). Pain is the third most prevalent complaint among patients with pancreatic cancer and is caused mainly by perineural invasion (17). In addition, several genes known to be linked to pain are upregulated in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord in murine models of pancreatic cancer, including Ccl12, Pin1, and Notum (26). In head and neck cancers, mechanical stimulation leads to the continuous production of serine proteases within the tumor microenvironment, resulting in pain (27).

3.2. Neuropathic Pain

Neuropathic pain is experienced by 20–40% of patients with cancer occurring as purely neuropathic in 20% of patients and mixed with nociceptive pain in 40% of patients. About two-thirds of neuropathic pain in cancer patients is due to direct tumor involvement; around 20% results from cancer treatment, and 10–15% from comorbid diseases (28). A burning sensation characterizes neuropathic pain; however, it can sometimes manifest as decreased sensation or muscle weakness (29). Compared to nociceptive pain, neuropathic pain is more debilitating, requires greater analgesics, and is associated with poor physical and social functioning (6,30).

Neuropathic cancer pain due to direct tumor infiltration can occur due to nerve compression and ischemia, demyelination, and axonal degeneration, and include radiculopathies, plexopathies, cranial neuralgia, peripheral neuropathies, cancer-induced bone pain, leptomeningeal metastases, and spinal cord compression (29). Cancer-mediated immune effects can lead to paraneoplastic neurological syndromes such as paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration and sensory neuronopathy (30).

Cancer-treatment-induced neuropathic pain can result from chemotherapy, surgery, or radiation therapy. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) is a common, dose-limiting side effect of chemotherapy that may begin in the first two months of treatment and persist for months or years after discontinuation of chemotherapy. Chemotherapeutic agents that cause peripheral neuropathy include platinum-based drugs (such as cisplatin and oxaliplatin), taxanes (paclitaxel and docetaxel), vinca alkaloids (vincristine), thalidomide, and bortezomib. CIPN mechanisms include mitochondrial dysfunction in sensory neurons, disruption of axonal transport, activation of sodium and calcium channels leading to hyperexcitability, neuronal injury and inflammation, oxidative stress, and the release of inflammatory cytokines (29,30). Surgical treatments may cause direct damage to peripheral nerves. In contrast, the mechanisms underlying radiation-induced neuropathy are not entirely understood. Still, they may result from nerve compression caused by radiation-induced fibrosis or direct nerve and blood vessel injury due to microvascular changes (31).

3.3. Cancer Pain Syndromes

Cancer pain syndromes are categorized as acute or chronic depending on the onset and duration of pain (Table). Understanding cancer pain syndromes is essential to know the etiology and prognosis of the pain and guide therapeutic interventions (32).

3.3.1. Acute Cancer Pain Syndrome

Acute cancer pain syndromes are mainly associated with diagnostic or therapeutic interventions; however, they may also be caused by direct tumor infiltration or antineoplastic therapy. The diagnostic and therapeutic interventions that lead to acute pain include blood sampling, lumbar puncture, biopsy, injections, pleurodesis, chest tube insertions, paracentesis, percutaneous biliary stent placement, vascular embolization, suprapubic catheterization, and nephrostomy tube insertion. Acute pain syndrome caused by the tumor itself merits urgent intervention as it may result from bone metastases, pathological fracture, hemorrhage into the tumor, superior vena cava syndrome, venous thromboembolism, or obstruction/perforation of a hollow viscus. Antineoplastic therapy can cause acute pain syndrome due to mucositis, myalgias, arthralgias, bone pain, hand-foot syndrome, headaches or chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (32).

3.3.2. Chronic Cancer Pain Syndrome

Chronic cancer-related pain is defined as chronic pain caused by the primary cancer itself or metastases. Antineoplastic therapy can also cause chronic pain due to neuropathy, arthralgias, osteoporosis, headache, lymphedema, or post-surgical pain (32, 33). Recently, chronic cancer pain has been classified as International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) to develop more individualized treatment plans for these patients and to stimulate research into these pain syndromes (34).

4. Assessment of Cancer Pain

Accurate assessment of cancer pain is essential for effective management. Cancer pain should be evaluated at every clinical visit, incorporating a comprehensive pain history, a physical examination, a psychosocial assessment, and appropriate diagnostic investigations. Self-report is the gold standard of evaluation; however, in practice, patients may be reluctant to accurately report their pain due to concerns about side effects or addiction to pain medications, not wanting to ‘complain’ about pain, trying to ensure that doctors prioritize cancer treatment over symptom control; or misconceptions about the inevitability of pain (35,36).

Pain Assessment Tools

Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs) in cancer pain are critical tools for understanding the patient’s subjective experience of pain. PROs guide treatment adjustments in real-time, improving quality of life.

Several validated PRO scales and tools can be used to assess cancer pain intensity:

Unidimensional pain scales: Unidimensional scales are a straightforward method for assessing only one aspect of pain, specifically its intensity. These scales may help determine the severity of acute pain.

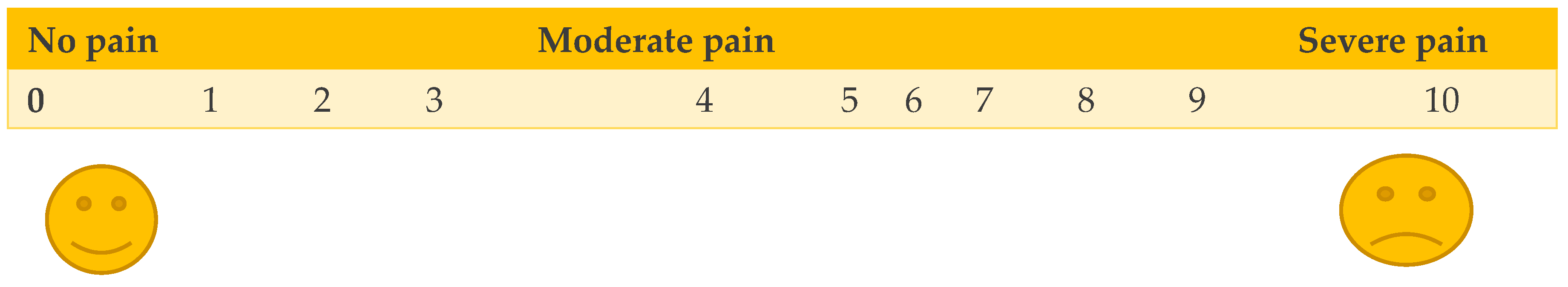

The Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) are the most used unidimensional pain scales (37).

The visual analog scale (VAS) is among the most frequently used pain scales in the United States. It consists of a horizontal (or vertical) line, usually 10 cm in length, the left end of which signifies no pain, while the right end signifies the worst possible pain. This visual depiction of pain levels helps patients communicate the intensity of their pain. The distance is measured in millimeters and interpreted as follows: no pain, 1 to 3 cm; mild pain, 4 to 6 cm; moderate pain, 7 to 10 cm; and severe pain.

In NRS, patients may be asked to circle numbers equally spaced on a page or verbally rate pain intensity using a scale of 0–10, in which 0 represents “no pain” and 10 represents “the worst pain imaginable.”

The advantages of numeric scales include their simplicity, reproducibility, and sensitivity to small changes in pain; however, they are inadequate for assessing neuropathic pain, which requires specialized scales (38).

Multidimensional pain scales:

Multidimensional pain scales have been developed to reflect the multidimensionality of the pain experience. They are more complex, but measure the intensity, nature, and location of the pain, as well as its impact on activity or mood. These are particularly helpful in cases involving complex or persistent acute or chronic pain. These include the McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) and the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI).

McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ)

The MPQ provides a quantitative measure of pain, allowing for the distinction between its sensory and emotional aspects. It can also be beneficial to detect a response to treatment. It consists of four parts and takes 5–15 minutes to complete. It primarily consists of different adjectives used to describe pain in three dimensions: sensory, affective, and evaluative. The words are subdivided into 20 subclasses that are tiered to represent relative intensity. Distribution, temporal pattern, and intensity of pain are also evaluated (39).

Brief Pain Inventory (BPI)

BPI quantifies both pain intensity and interference or impact on function. It is used for patients with cancer, human immunodeficiency virus, and arthritis. It takes 5–15 minutes to complete and utilizes 11 numeric scales to assess pain intensity, mood, ability to work, relationships, sleep, enjoyment of life, and the impact of pain on general activity. The Brief Pain Inventory can measure the progress of a patient with a progressive disease, indicating whether the patient is showing improvement or decline in their mood and activity level. Evaluating function is essential in overall pain management (40).

In patients with cognitive deficits, observing pain-related behaviors such as facial expressions, body movements, verbalization, or vocalizations, as well as changes in interpersonal interactions, is an alternative strategy for assessing the presence of pain (but not its intensity). Different observational scales are available in the literature, but none of them is validated in other languages (41,42).

5. Treatment of Cancer Pain

Correct identification of the etiology and the characteristic of pain is mandatory to achieve optimal pain control in cancer patients and survivors. The concept of metamorphic pain management, which integrates interdisciplinary care teams, helps tailor treatment, provide innovative options, and offer better supportive care (43).

The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed Guidelines (the last set issued in 1996) for the pharmacological and radiotherapeutic management of cancer pain, providing evidence-based guidance for initiating and managing cancer pain.

The clinical guidelines and recommendations are organized into three focal areas:

Analgesia of cancer pain: This addresses the choice of analgesic medicine when initiating pain relief and the choice of opioid for maintenance of pain relief, including optimization of rescue medication, route of administration, and opioid rotation and cessation.

Adjuvant medicines for cancer pain: This includes the use of steroids, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants as adjuvant medicines (44).

Management of pain related to bone metastases: This incorporates the use of bisphosphonates and radiotherapy to manage bone metastases.

5.1. The Original WHO Analgesic Ladder

The original WHO analgesic ladder, proposed in 1986, remains the cornerstone of cancer pain treatment: This comprises a three-step approach (

Table 1) (12):

WHO recommendations on the proper use of analgesics include:

| Oral administration of analgesics |

Whenever possible, the oral form should be preferred. |

| Analgesics should be given at regular intervals. |

Prescribe the dosage to be taken at regular intervals based on the patient’s level of pain. The dosage of medication should be adjusted until the patient is comfortable and experiencing relief from their symptoms. |

| Analgesics should be prescribed according to pain intensity. |

Pain medications should be prescribed after a proper assessment of the pain using pain scales. |

| Dosing pain medication should be adapted to the individual. |

There is no standardized dosage for treating pain. The correct dosage will provide adequate pain relief. |

| Analgesics should be prescribed with meticulous attention to detail. |

The regularity of analgesic administration is crucial for effective pain treatment. Once the distribution of medication over a day is established, it is ideal to provide the patient with a written personal program. In this way, the patient, his family, and medical staff will all have the necessary information about when and how to administer the medications. |

5.2. The Revised WHO Analgesic Ladder

The revised WHO analgesic ladder integrates a fourth step and includes consideration of neurosurgical procedures such as brain stimulators. Invasive techniques, such as nerve blocks and neurolysis (eg, phenolization, alcoholization, thermocoagulation, and radiofrequency are used at the fourth step (45-47). The new fourth step is recommended for the treatment of chronic pain.

This new adaptation of the analgesic ladder adds new opioids, such as tramadol, oxycodone, hydromorphone, and buprenorphine, and also new ways of administering them, such as by transdermal patch, that did not exist in 1986 (48). Methadone, in step 3, is crucial because it is currently instrumental in the treatment of cancer pain and is also very useful in the rotation of opioids (47,49).

Adjuvant medications include steroids, anxiolytics, antidepressants, hypnotics, anticonvulsants, antiepileptic-like gabapentinoids (gabapentin and pregabalin), membrane stabilizers, sodium channel blockers, and N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonists for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Cannabinoids can be added to this group of adjuvant medications, not only because they hold a place as adjuvants in the care of palliative cancer patients and patients affected by AIDS, but also because they can be used to offer a better quality of life to patients with chronic pain. They can also be used to treat chronic neuropathic pain (50,51).

This version of the analgesic ladder can be used in a bidirectional fashion: the slower upward pathway for chronic pain and cancer pain, and the faster downward direction for intense acute pain, uncontrolled chronic pain, and breakthrough pain. The advantage of this proposal is that one can ascend slowly, one step at a time, in the case of chronic pain, and, if necessary, increase the rate of climb according to the intensity of the pain. However, one can start directly at the fourth step, in extreme cases, to control pain of high intensity, using patient-controlled analgesia pumps for continuous intravenous, epidural, or subdural administration. When the pain is controlled, one can “step down” to medications from step 3.

5.3. Pharmacological Options

5.3.1. Non-Opioid Analgesics (Table 3)

5.3.1.1. Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDS)

NSAIDS are used in mild to moderate cancer pain and in combination with opioids for more severe pain. NSAIDS cause inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, which are key in the synthesis of prostaglandins that mediate inflammation, pain, and fever. There are two types of COX enzymes: COX-1 and COX-2. Non-selective NSAIDS like Ibuprofen, Naproxen, and Ketorolac inhibit both COX enzymes, whereas Celecoxib selectively inhibits COX-2, leading to a different side-effect profile. Gastric bleeding and renal impairment have been associated with COX-1 inhibition, whereas COX-2 inhibition leads to increased risk of thrombosis (52). NSAIDs have ceiling effects with no therapeutic gain and increased adverse effects by increasing doses beyond recommended dosages, unlike opioids that can be titrated for pain relief (52).

5.3.3.2. Acetaminophen (Paracetamol)

Acetaminophen weakly inhibits central COX enzymes, particularly COX-2, in the brain and spinal cord. Unlike NSAIDS, it does not inhibit COX-1 or COX-2 effectively in peripheral tissues, thereby lacking a vigorous anti-inflammatory activity. Acetaminophen is frequently used in combination with opioids or NSAIDS for multimodal pain control. Acetaminophen is associated with hepatotoxicity at higher doses, so doses should not exceed 4000 mg per day (53).

5.3.3.3. Adjuvant Analgesics

Antidepressants such as serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), e.g., Duloxetine, and tricyclic antidepressants (TCIs), e.g., Amitriptyline and Nortriptyline, and anticonvulsants like Gabapentin and Pregabalin are used to treat neuropathic pain and used as adjuvant therapies with non-opioid and opioid medications for additive benefit. However, their use is limited by side effects like drowsiness, urinary retention, and constipation, especially in elderly patients (53,54).

5.3.3.4. Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids, such as dexamethasone and prednisone, have anti-inflammatory effects and may be beneficial in managing inflammatory pain. Corticosteroids reduce peritumoral edema, which helps to improve pain in brain metastases and malignant spinal cord compression by causing tumor shrinkage. Corticosteroids also cause neuroimmune modulation that may help neuropathic pain. Corticosteroids should be used at the lowest effective dose due to a range of adverse effects, including hyperglycemia, gastric ulceration, osteoporosis, immunosuppression, and neuropsychiatric manifestations (55).

5.3.3.5. N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) Receptor Antagonists

Ketamine, an NMDA receptor antagonist, is often used in low doses in palliative care settings for refractory neuropathic pain (53). Amantadine is another NMDA receptor antagonist that has shown some benefit in alleviating neuropathic pain (56).

5.3.3.6. Cannabinoids

Cannabinoids produce an analgesic effect by activating CB1 receptors present in the CNS and nerve terminals and CB2 receptors in peripheral immune cells. Cannabinoids like delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) may be used as an alternative or substitute in patients who are unable to take opioids and NSAIDs in cancer pain, mainly neuropathic pain. Cannabinoids also stimulate appetite and alleviate anxiety. Their use is limited by cognitive impairment, sedation, and legal issues (57).

5.3.3.7. Bisphosphonates and RANKL Inhibitors

Bisphosphonates have a high affinity for bone, reduce the activity of osteoclasts, and inhibit bone resorption, thereby alleviating bone pain. Bisphosphonates also affect the bone microenvironment and reduce the invasion of tumor cells, thereby delaying the development of bone metastases in high-risk, early-stage cancers. They may also have direct tumor cytotoxicity and antiangiogenic activity. Bisphosphonates reduce skeletal-related events (SREs) in many malignancies, including multiple myeloma, breast, prostate, and other solid tumors. The most commonly used bisphosphonates are zoledronic acid and pamidronate. Bisphosphonates are generally well tolerated. The significant side effects include acute-phase reactions, renal toxicity, electrolyte abnormalities, and osteonecrosis of the jaw (58,59).

Receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand (RANKL) is crucial for the formation, function, and survival of osteoclasts, which leads to skeletal destruction in bone metastases. Denosumab is a fully human anti-RANKL antibody that reduces skeletal adverse events and bone pain in cancer patients with bone metastases (60,61).

5.3.3.8. Topical Agents

Topical analgesics such as 8% capsaicin and 5% lidocaine patches are great alternatives for pain management and an essential part of multimodal analgesia. The rationale of topical drugs is based on their ability to block or inhibit the pain pathway locally or peripherally, with minimum systemic uptake. They are easy to use with direct access to target sites and minimal systemic adverse effects. They are mainly effective in neuropathic pain (62).

5.3.3.9. Antispasmodics

Antispasmodics and muscle relaxants such as baclofen and hyoscine have been used as adjunctive therapies for pain control, especially muscle-spasm-related pain and visceral pain (56).

5.3.3.10. Novel Non-Opioid Drugs

Haloperidol is a high-affinity, irreversible sigma-1 receptor antagonist with analgesic potential, apart from being an antipsychotic drug. Sigma-1 receptors are over-expressed in neuropathic pain. Haloperidol has been shown to benefit neuropathic pain, pain from fibrosis, and radiation necrosis in some studies. Haloperidol may be used as an adjuvant to opioid medications (63).

Mirogabalin besylate is a gabapentinoid approved for the treatment of neuropathic pain in Japan since 2019. Mirogabalin, like pregabalin, blocks presynaptic voltage-gated calcium channels, which prevents neurotransmitter release across the synapse. Mirogabalin has been shown to improve neuropathic pain in pancreatic cancer and oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy. The side effects include dizziness, headache, and constipation (63).

Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) belongs to a group of endogenous bioactive lipids called ALI Amides that modulate non-neuronal neuroinflammatory responses to neuropathic injury and systemic inflammation. In clinical studies, PEA was found to improve oxaliplatin-induced neuropathic pain and as an adjunct for opioid analgesia (63).

Clonidine is an alpha2 adrenoceptor agonist and an imidazoline2 receptor agonist found to be beneficial as an adjunctive therapy for cancer-related pain and neuropathic pain (63).

Table 2.

Summary of Non-Opioid Medications for Cancer Pain.

Table 2.

Summary of Non-Opioid Medications for Cancer Pain.

| Drug Class |

Examples |

Best for |

| NSAIDS |

Ibuprofen, Naproxen, Ketorolac, Celecoxib |

Mild pain, Bone pain, and Inflammation. |

| Acetaminophen |

Paracetamol |

Mild pain, adjunct use. |

| Antidepressants |

Duloxetine, Amitriptyline, Nortriptyline |

Neuropathic pain |

| Anticonvulsants |

Gabapentin, Pregabalin |

Neuropathic pain |

| Corticosteroids |

Dexamethasone, Prednisone |

Bone pain, edema, nerve compression. |

| NMDA receptor antagonists |

Ketamine |

Refractory neuropathic pain |

| Cannabinoids |

THC, CBD |

Neuropathic pain, appetite stimulant, anxiolytic |

| Bisphosphonates |

Zoledronic acid, Pamidronate |

Bone metastases, Bone pain |

| RANKL inhibitors |

Denosumab |

Bone metastases, Bone pain |

| Topical agents |

Lidocaine patch, Capsaicin |

Localized neuropathic pain |

| Antispasmodics |

Hyoscine, Baclofen |

Visceral/Muscle-related pain |

| Novel drugs |

Haloperidol, Mirogabalin, PEA, Clonidine |

Neuropathic pain, adjunct use. |

5.3.2. Opioid Analgesics

Opioids are the cornerstone in cancer pain management because of their effectiveness, ease of titration, and reliability. Opioids act by binding to opioid receptors (delta, kappa, or mu), primarily the mu opioid receptors (MORs), present in both the peripheral and central nervous systems. Opioids are the first-line approach for moderate to severe cancer pain (64). Opioids are effective analgesics against breakthrough cancer pain, defined as a transient flare of pain that occurs on a background of relatively well-controlled baseline pain, of moderate to severe intensity, with rapid onset (minutes), and of relatively short duration (median, 30 minutes) (65).

Despite the effectiveness of opioids, the opioid epidemic, due to misuse and addiction, created tension between effective pain relief and safety/regulatory concerns. Cancer patients faced challenges post-epidemic because of stricter prescribing laws, fear among physicians and pharmacists, and payer restrictions leading to under-prescription, premature tapering, insurance denials, and refusal to fill even appropriately prescribed opioids (10,11).

Opioid analgesics are categorized as either agonists, antagonists, or partial agonists depending on the response they produce after interacting with the opioid receptors.

The most commonly used opioid analgesics for cancer pain include morphine, methadone, buprenorphine, fentanyl, hydromorphone, oxycodone, tramadol, codeine, and dihydrocodeine. Tramadol, codeine, and dihydrocodeine are weak opioids and are used for mild to moderate pain in combination with non-opioid analgesics. Potent opioids like morphine, methadone, buprenorphine, fentanyl, hydromorphone, and oxycodone are the mainstay of analgesic therapy in treating moderate to severe cancer pain. Tapentadol is a new class of analgesic having µ-opioid receptor agonist and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitory actions, considered as an alternative to morphine and oxycodone, especially when opioid toxicities are an issue (66). Morphine, methadone, and fentanyl patches are considered essential medicines in the WHO list of analgesics for cancer pain (67).

5.3.2.1. Tramadol

Tramadol is a centrally acting analgesic often used for mild to moderate cancer pain, classified as step 2 in the WHO analgesic ladder. Tramadol has a dual mechanism of action: it is a weak agonist of μ-opioid receptors and inhibits the reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin (68). Tramadol has also been found to be effective in neuropathic cancer pain and appears to improve the quality of life (69). Tramadol may be used as a bridge between non-opioids and potent opioids for moderate pain and offers some benefits in terms of a lower side-effect profile, like less constipation, lower risk of respiratory depression, and safer use in elderly patients. The limitations of tramadol use include lowered seizure threshold, mainly when used with antidepressants, increased risk of serotonin syndrome, variable metabolism, and limited potency for moderate to severe cancer pain. Tramadol is used at a starting dose of 25-50 mg every 6 hours with a maximum dose of 400 mg per day (68).

5.3.2.2. Codeine

Codeine is a weak opioid analgesic and, like tramadol, is used at step 2 of the WHO analgesic ladder. Codeine is a prodrug and is metabolized to morphine in the liver. Codeine is typically recommended at doses between 30 mg and 60 mg for use in mild to moderate pain. In most people, 5% to 10% of codeine is converted to morphine; a 30 mg dose of codeine is considered equivalent to a 3 mg dose of morphine. The studies indicate that codeine is more effective than a placebo for cancer pain, but with increased risk of nausea, vomiting, and constipation, and inadequate analgesia for more severe cancer pain (70).

5.3.2.3. Dihydrocodeine

Dihydrocodeine is another weak opioid used for mild to moderate cancer pain. Dihydrocodeine primarily exerts its analgesic action through μ-opioid receptors, with lesser effects through κ-opioid receptors and δ-opioid receptors. Dihydrocodeine is superior to tramadol in cancer pain, twice as strong as codeine, and the metabolite dihydromorphine is likewise twice as potent as morphine (71).

5.3.2.4. Morphine

Oral morphine is the first choice for moderate to severe cancer pain because of its wide availability, cost-effectiveness, and decades of clinical use and evidence. Morphine is predominantly a MOR agonist but also acts on delta and kappa receptors. Morphine is used at step 3 of the WHO analgesic ladder, may be used when there is an inadequate response to step 2 analgesics, for end-of-life/palliative care, bone metastases, visceral pain, and dyspnea in cancer. Morphine has a short half-life and is primarily metabolized in the liver to two active metabolites, morphine-3-glucuronide (M3G) and morphine-6-glucuronide (M6G). Morphine is available in multiple formulations, oral tablets, oral liquid, suppository, and solution for intravenous (IV) and subcutaneous (SC) use, which makes it a favorable opioid among clinicians. The limitations of morphine use include tolerance and dependence, caution in renal dysfunction, and side-effects of nausea, constipation, and sedation (72).

5.3.2.5. Oxycodone

Oxycodone is a MOR agonist with some kappa receptor activity used for moderate to severe cancer pain as an alternative to morphine. Oxycodone has higher oral bioavailability than morphine and can be safely used in renal dysfunction and in patients who are intolerant to morphine. The side effect profile of oxycodone is similar to morphine (73).

5.3.2.6. Hydromorphone

Hydromorphone is a pure MOR agonist and five to seven times more potent than morphine when given orally. Like morphine, multiple dosage forms of hydromorphone are available, including oral liquid, oral tablet, suppository, and solution for IV or SC use. Hydromorphone is a preferred potent opioid for severe or escalating pain, safer in renal impairment, allows rapid titration, and is effective in small doses. Oral hydromorphone is 4-5 times stronger than oral morphine, whereas IV formulation is seven times stronger than IV morphine (74).

5.3.2.7. Fentanyl

Fentanyl is a selective MOR agonist used as maintenance for severe and chronic cancer pain. It is highly lipophilic and available in IV, transdermal, and oral transmucosal formulations. Transdermal fentanyl may be preferred over oral opioids in cases of poor gastrointestinal absorption, dysphagia, or constipation. Fentanyl is 80-100 times more potent than morphine and can be safely used in renal dysfunction. For opioid -tolerant patients, the transdermal patch starts at a dose of 12-25 mcg/hour and is changed every 72 hours. The transdermal patch is extremely heat sensitive. External heat exposure increases the absorption of fentanyl, leading to potential overdose and respiratory depression. Transmucosal, buccal, and nasal forms are used for breakthrough cancer pain (75).

5.3.2.8. Methadone

Methadone is a long-acting opioid with MOR agonist and NMDA receptor antagonist properties. Methadone also inhibits the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine. These properties make methadone a suitable option for cancer patients with neuropathic pain in addition to nociceptive pain. Methadone is equally effective to morphine for cancer pain with higher oral bioavailability, lower cost, longer duration of action, and safer use in renal dysfunction. The toxicity profile of methadone is similar to that of morphine and fentanyl. Methadone causes QT prolongation in a dose-dependent manner, so ECG monitoring is required in patients who require > 30 mg/day (76). The fact that methadone alleviates opioid cravings makes it a suitable option to use in opioid addiction treatment (77).

5.3.2.9. Tapentadol

Tapentadol is a new class of analgesics having a central mechanism of action with synergistic MOR agonist and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitory actions. It is effective in both opioid-naive patients and those already taking opioids. By having a lower µ-opioid receptor binding affinity, it has fewer opioid-related toxicities such as constipation and nausea. Tapentadol has been shown in a range of studies to be an effective analgesic. It thus should be considered as an alternative to morphine and oxycodone, especially when opioid toxicities are an issue (66).

5.3.3. American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Guidelines on Use of Opioids for Cancer Pain

The following clinical practice guideline recommendations were developed based on a systematic review of the medical literature (

Table 3) (78).

Table 3.

ASCO Recommendations on Opioid Use for Cancer Pain.

Table 3.

ASCO Recommendations on Opioid Use for Cancer Pain.

| Questions |

Recommendations |

| Initiation of opioids |

All patients with cancer having moderate-to-severe pain should be offered opioids unless contraindicated.

Clinicians, patients, and caregivers should discuss goals related to functional outcomes, potential side effects, and the importance of adhering to the prescribed regimen. |

| Choice of opioids |

Any opioid approved by the FDA or other regulatory agencies for pain treatment. Choice is based on factors such as pharmacokinetic properties, including bioavailability, route of administration, half-life, neurotoxicity, and cost of the differing drugs. |

| Initial dose and titration |

Begin with the lowest effective dose of short-acting opioids and PRN (as needed). Early assessment and frequent titration are essential to achieve optimal pain control.

Patients on non-opioid drugs may continue those after opioid initiation if they provide additional analgesia and are not contraindicated.

Doses should be increased by 25%-50%, but patient factors such as frailty, comorbidities, and organ function must be taken into consideration. |

| Opioids in renal or hepatic dysfunction |

Morphine, meperidine, codeine, and tramadol should be avoided unless there are no alternatives.

Methadone can be given safely in renal impairment.

Fentanyl, oxycodone, and hydromorphone should be carefully titrated and frequently monitored for adverse effects. |

| Opioids for Breakthrough Pain |

In patients receiving opioids around the clock, short-acting opioids at a dose of 5%-20% of the daily regular morphine equivalent daily dose should be prescribed for breakthrough pain. |

| Opioid Rotation |

Opioid rotation should be offered to patients with inadequate pain relief, intolerable side effects, logistical or cost concerns, or trouble with the route of opioid administration or absorption. |

5.3.4. Choice of Opioid for Cancer Pain

Selecting the right opioid and dose is key to safe and effective cancer pain control. This requires careful assessment of patients to determine the type and severity of pain, history of opioid use, renal or hepatic dysfunction, cognitive status, and the route of administration required.

In opioid-naïve patients with moderate to severe pain, any short-acting selective MOR agonist may be used at low doses (

Table 4) (79). The options include oral morphine, oral oxycodone, hydromorphone, or transdermal fentanyl (

Table 5).

Patients who require multiple doses of short-acting drugs daily should be switched to a long-acting formulation (80) (

Table 6). Morphine or hydromorphone may be preferred over oxycodone due to once-daily dosing. Transdermal fentanyl may be preferred over oral morphine in case of constipation.

5.3.5. Opioid Dose Titration in Cancer Pain

Opioid dose adjustment is always required to optimize the regimen and sustain its benefits over time. This requires reassessment of the pain every 24 hours to look for adequate pain control, intolerable side-effects, and whether the patient is requiring more frequent prn doses > 2-3 per day. In cases of inadequate analgesia, the dose of an opioid can be increased until a favorable balance between analgesia and side effects is obtained, or the patient develops intolerable and unmanageable side effects. The need for a relatively high dose (e.g., a dose equivalent to >200 mg morphine) in an individual patient should prompt careful reassessment. The total daily dose should be increased by 25-50%. Ideally, the interval between dose escalations should be long enough to allow a new steady state (which requires five to six half-lives, irrespective of the route or drug) to be approached following each dose adjustment. For patients with severe pain, more rapid dose escalation is needed. As the dose of the fixed-schedule opioid regimen is increased, the dose of the PRN drug must also be increased. In most cases, the dose of this short-acting medication should remain in the range of 5 to 15 percent of the total daily dose (81,82).

In cases of poorly responsive pain, opioid rotation is done, which is defined as a switch from one opioid to another to provide better outcomes. The starting dose of the replacing drug must be close enough to its predicted equianalgesic dose to prevent the development of withdrawal or unintentional overdose (83). For opioid conversion, calculate the total 24-hour dose of the current opioid and convert to morphine oral equivalent (MME) by using equivalence ratios (

Table 7). The starting dose of all major opioids is equivalent to 30 mg of morphine per day orally.

5.3.6. Breakthrough Cancer Pain

Breakthrough pain is a transitory, acute pain that occurs on a background of adequately controlled chronic pain. Breakthrough pain is severe in intensity, has a rapid onset, and usually lasts < 30 minutes. Breakthrough pain is distinct from background pain, requires specific assessment, and should be treated with fast-acting interventions. Clinically significant breakthrough pain is usually managed by prescribing a rescue drug, which is generally a short-acting opioid such as immediate-release morphine, oxycodone, hydromorphone, or oxymorphone. The breakthrough doses are usually 10-15% of the total daily opioid dose, given every 2-4 hours prn (84).

5.4. Interventional Therapies for Cancer Pain

Interventional therapies may be helpful for cancer patients who are poorly responsive to opioid analgesics or develop intolerable side effects. Interventional therapies include invasive analgesic techniques such as injections, ablations, infusion therapies, neuromodulation, and some minimally invasive surgical techniques (85,86).

Epidural and Intrathecal Analgesia: Delivery of opioids/local anesthetics or other adjuvants such as clonidine/ketamine to opioids via spinal routes for severe pain. Cancer patients with a longer survival expectancy (>3 months) may benefit from implantable systems, such as a permanent intrathecal catheter and subcutaneous pump. In contrast, patients with a shorter life expectancy may be treated with epidural therapy using an implanted system, such as a catheter or port-a-Cath connected to an external PCA pump.

Nerve Blocks: Targeted injections for localized pain, such as celiac plexus block for pancreatic cancer. Which is highly effective with a success rate of 80–90% for pancreatic cancer pain. Intercostal nerve blocks help reduce pain from primary or metastatic cancers of the chest wall and pleura. They can also be used for post-mastectomy and implant pain, and post-herpetic intercostal neuralgia.

Neuromodulation: refers to the application of electrical stimulation to nerves to alter pain signaling. Neuromodulation encompasses spinal cord stimulation (SCS) and dorsal root ganglion (DRG) stimulation, primarily used for managing neuropathic pain and in cases that are refractory to other treatments.

Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA) – Used for intractable pain from bone metastases. RFA uses radio waves to heat an area of nerve tissue to destroy it.

Minimally invasive surgical procedures like kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty for painful vertebral metastases or compression fractures without neurologic sequelae. Palliative Surgery may be used for tumor debulking in cases of obstruction-related pain or tumor bleeding.

Radiotherapy: Effective for bone metastases and spinal cord compression pain.

5.5. Integrative Therapies for Cancer Pain

Integrative therapies such as acupuncture, hypnosis, massage, and mindfulness-based therapies have shown efficacy in multimodal pain management. The Society for Integrative Oncology and ASCO recommend acupuncture for aromatase inhibitor–related joint pain, as well as reflexology or acupressure for general cancer pain or musculoskeletal pain. Additionally, hypnosis is recommended for patients who experience procedural pain, and massage is suggested for patients experiencing pain during palliative or hospice care (87).

6. Biomarkers in Cancer Pain

Biomarkers in cancer pain are a rapidly evolving area of research aimed at identifying objective, measurable indicators that can predict, diagnose, or monitor pain in patients with cancer. These biomarkers can help personalize pain management strategies and improve outcomes (88,89). In cancer pain, several types of biomarkers are under investigation:

Inflammatory Biomarkers: Cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α are elevated in patients with cancer pain, especially those with bone metastases or neuropathic pain. C-reactive protein (CRP) correlates with systemic inflammation and the severity of pain.

Genetic and Epigenetic Biomarkers: Polymorphisms in genes like OPRM1 (μ-opioid receptor), COMT (catechol-O-methyltransferase), and CYP2D6 can influence opioid response, metabolism, and susceptibility to pain. Epigenetic changes (e.g., DNA methylation in pain-related genes) may modulate individual pain perception (89).

Neurotransmitters and Neuromodulators: Substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) are involved in nociceptive transmission and may be elevated in chronic and neuropathic cancer pain. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is implicated in pain sensitization and the development of chronicity (89).

Neuroimaging Biomarkers: Functional MRI (fMRI) and PET scans can detect altered activity in pain-processing brain regions, potentially serving as objective pain biomarkers in the future (89)

Metabolomic and Microbiome Biomarkers: Metabolomic changes, such as high lactate levels, which are linked to muscle pain, may help understand the metabolic changes in pain disorders. Gut flora compositions may help identify the links between gut health and chronic pain (89).

7. Personalized Approach to Cancer Pain Management: Integrating Precision Medicine

While WHO guidelines provide effective pain relief for about 75% of cancer patients, they often fall short in addressing the complex, multidimensional nature of cancer pain (90). Cancer pain is highly individualized, influenced by diverse pain mechanisms, tumor characteristics, and patient-specific factors. Precision medicine tailors pain assessment and treatment to each patient’s unique biological and genetic profile, while the personalized approach tailors care for the whole patient. Integrating both offers the most effective, equitable, and compassionate cancer pain management (91,92,93).

Therefore, a multimodal strategy is essential, incorporating:

Pain Mechanisms, Phenotypes, and Biomarkers: Cancer pain can be nociceptive, neuropathic, or mixed. For instance, bone metastases typically cause inflammatory nociceptive pain, whereas nerve compression results in neuropathic pain, which may be less responsive to opioids. Many patients experience overlapping pain mechanisms, necessitating a combination of opioids and adjuvant therapies. Precision pain medicine involves systematically identifying the dominant pain phenotype (nociceptive, neuropathic, or mixed) in each patient, which guides the choice of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic therapies. Emerging biomarkers are being explored to define pain phenotypes better and guide individualized treatment strategies (88,89).

Tumor Type, Stage, and Treatment: Pain varies by cancer type, location, stage, and treatment received. Advanced malignancies (such as pancreatic or head and neck cancers) and interventions like surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation often intensify pain, requiring both pharmacologic and interventional approaches tailored to the patient’s clinical context.

Patient-Specific Factors: Individual characteristics, including age, genetics, organ function, prior opioid exposure, and psychosocial factors, significantly influence pain perception and management. Older adults may have altered drug metabolism and heightened sensitivity to opioids, necessitating careful dosing and monitoring. Genetic variations, such as in CYP2D6, COMT, and OPRM1, can influence how patients metabolize and respond to analgesics, especially opioids. Testing for these variants may help clinicians select the most effective drugs and dosages, reducing side effects and improving pain control (89,93). Comorbidities like renal or hepatic dysfunction require thoughtful opioid selection and dose adjustments. Psychological factors (depression, anxiety), substance use, cultural background, language barriers, and health literacy all impact pain expression, reporting, and treatment adherence. Addressing these factors is crucial for equitable and adequate pain control.

7.1. Framework for Personalized Cancer Pain Management

We propose a five-domain framework to address the complexity of cancer pain (

Table 8):

Biological – Pain mechanism, tumor type, biomarkers

Pharmacologic – Opioid sensitivity, prior exposure, drug metabolism

Psychological – Mental health, coping skills, support systems

Sociocultural – Language, beliefs, stigma, access to care

Functional - Performance status, Caregiver availability, Ability to manage complex regimens

Multidisciplinary teams should assess these domains and construct individualized care plans.

8. New Advances in Cancer Pain Management

8.1. Targeted Therapies

8.1.1. Protein Kinase Inhibitors

Various protein kinases, such as tropomyosin-related kinases (Trks) including TrkA, TrkB and TrkC, protein kinases A, G, and C, p38 MAPK (p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase), ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase), PKG (protein kinase G), mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin), MNKs (MAPK-interacting kinases), cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) such as CDK5 have emerged as potential targets that directly affect pain signaling pathways (94,95). The involvement of nerve growth factor (NGF) and its receptor TrkA in chronic pain is now well established, and therapies that target NGF-TrkA, have demonstrated significant analgesic activity (96). Tanezumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting NGF, has shown efficacy in treating pain associated with bone metastases (97). The development of novel protein kinase inhibitors for cancer pain management remains challenging and requires a deeper understanding of their role in pain mechanisms.

8.1.2. Ion Channel Inhibitors

Ion channel inhibitors have shown promise in managing neuropathic pain and cancer-induced bone pain. Voltage-gated ion channels, including sodium (NaV), calcium (CaV), and potassium (KV) channels, play a pivotal role in modulating neuronal excitability and pain signal transmission following nerve injury. NaV channels play a relevant role in the development and maintenance of neuropathic pain. Studies in animals and humans have validated sodium channels, mainly NaV1.7, NaV1.8, and NaV1.9, as viable targets for pain treatment. VX-548, a selective NaV1.8 blocker, has been approved by the FDA for moderate to severe acute pain. It is being studied for its potential in treating neuropathic pain, offering an alternative to opioids, with a favorable side effect profile and no addictive potential. Among CaV channels, CaV2.1 (P/Q-type) and CaV2.2 (N-type) are particularly important in neuronal excitability, synaptic transmission, and pain signaling. Ziconotide, has been established as an effective blocker of CaV2.2 channels for treating severe chronic neuropathic pain. C2230 is a novel blocker of CaV2.2 channels, reported for its potential as an analgesic across various pain models. Among potassium (KV) channels, KV1.2 channels have been identified as molecular actors in the pathophysiology of neuropathic pain; however, they have not yet been used as a therapeutic target. Due to the complexity of neuropathic pain and the considerable diversity of ion channels, significant challenges exist in investigating voltage-gated ion channels in the context of neuropathic pain (98).

Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) ion channels have been shown to modulate pain perception characterized by nociceptive and neuropathic pain, with a possible role in the pathogenesis of cancer-induced bone pain (CIBP) as well. TRV channels are divided into: TRPC (canonical), TRPA (Ankyrin), TRPM (melastatins), TRPML (mucolipins), TRPP (polycystins), TRPV (vanilloids), and TRPN (no mechanoreceptor potential C channels) with different properties. TRP ion channels are implicated in bone metabolism and in various diseases, including osteoporosis and bone metastases. TRPV1 and TRPV2 are involved with multiple myeloma progression, while TRPM7 promotes disease dissemination. TRPV1 is also known as “capsaicin receptor”, because of its sensitivity to vanilloid capsaicin. TRPV1 was first assessed in bone cancer pain in 2005, when it was found that most sensory neurons in tumorous bone expressed TRPV1, and subcutaneous administration of its antagonist, JNJ-17203212, reduced pain-induced behaviors. The use of TRPV1 antagonists resulted in reduced sensitivity to nociception in preclinical pain models, with special regard to CIBP, with variability in their analgesic effects, possibly due to differences in their pharmacological properties. Resiniferatoxin (RTX), an ultra-potent capsaicin analogue, acts as a TRPV1 agonist and has been tested in patients with advanced cancer and refractory pain with a favorable response. Many other TRP channel modulators are under study and may be an appealing field of research in CIBP (99).

8.2. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Digital Health

AI is being increasingly integrated into healthcare to enhance patient safety across various processes, including pain assessment. Traditional pain assessment methods can be subjective and influenced by multiple factors, leading to a misinterpretation of pain levels. AI-driven camera-based methods have emerged as alternatives to conventional methods for PROs, eliminating the need for physical contact. They are particularly beneficial for patients with difficulty communicating verbally, such as infants or those with dementia. AI for face recognition can capture facial expressions to recognize pain. These camera-based approaches can be integrated into pain management protocols for cancer patients in inpatient and home care settings. Contact-Sensor approaches, such as electrodermal activity (EDA), electrocardiogram (ECG), and electroencephalography (EEG), may be used for pain evaluation. Other methods include incorporating AI algorithms in audio events and voice recognition for pain assessment. Advances in AI are beginning to transform the treatment and relief of cancer-related pain as we navigate the field of oncology (100).

9. Challenges in Advancing Precision and Personalized Cancer Pain

While precision and personalized medicine offer promising avenues for improving cancer pain management, several critical challenges must be addressed to realize their potential fully:

-

Tumor and Patient Heterogeneity

The complex interplay between tumor biology, pain mechanisms, and individual patient variability makes it challenging to predict pain experiences and tailor interventions effectively. Differences in pain phenotypes and underlying pathophysiology contribute to inconsistent treatment outcomes (101).

-

Limited Biomarkers and Pharmacogenomic Tools

The lack of validated biomarkers and genetic predictors of pain perception and analgesic response hinders the development of personalized analgesic regimens. Progress in pharmacogenomics remains slow, limiting clinicians’ ability to optimize treatment based on individual genetic profiles (89).

-

Data Complexity and Integration

Leveraging high-throughput genomic and clinical data requires sophisticated infrastructure and analytic frameworks. Challenges in standardization, data sharing, and interoperability limit the practical use of precision tools in clinical settings (102).

-

Access and Equity

The high cost of genomic testing and precision diagnostics, along with geographic and systemic barriers, restricts access for many patients, particularly those in low-resource or underserved settings, exacerbating existing disparities in pain management and cancer care (102).

-

Digital Health Integration

Cancer pain management is complex and often unfolds within the context of competing personal goals and limited resources. Digital health technologies, such as mobile apps and remote symptom monitoring platforms, offer opportunities to personalize pain tracking and improve patient–clinician communication. However, the challenge lies in ensuring that these tools truly add value without overburdening patients, caregivers, or clinicians. Solutions must be intuitive, adaptive, and seamlessly integrated into care workflows to be effective and equitable (103).

10. Conclusions

Cancer pain management has evolved significantly, from historical under-treatment to modern multimodal and targeted approaches. While opioids remain a cornerstone, newer pharmacological and interventional strategies, including targeted therapies, neuromodulation, and integrative therapies, offer promising alternatives. The integration of AI-driven pain assessment and digital health tools further refines individualized treatment strategies. Central to this evolution is the recognition that cancer pain is complex and deeply personal, requiring care tailored to each patient’s unique biology, psychology, and sociocultural factors. While advances in precision and personalized medicine are transforming cancer pain management, challenges related to tumor and patient heterogeneity, biomarker validation, data complexity, access, clinical implementation, safety, and inclusivity must be addressed to realize the full potential of these innovations.

References

- Snijders R.A.H., Brom L., Theunissen M., van den Beuken-van Everdingen M.H.J. Update on Prevalence of Pain in Patients with Cancer 2022: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers. 2023;15:591. [CrossRef]

- Mestdagh F, Steyaert A, Lavand’homme P. Cancer Pain Management: A Narrative Review of Current Concepts, Strategies, and Techniques. Curr Oncol. 2023 Jul 18;30(7):6838-6858. PMID: 37504360; PMCID: PMC10378332. [CrossRef]

- Evenepoel M., Haenen V., De Baerdemaecker T., Meeus M., Devoogdt N., Dams L., Van Dijck S., Van der Gucht E., De Groef A. Pain Prevalence During Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2022;63:e317–e335. [CrossRef]

- Kroenke K., Theobald D., Wu J., Loza J.K., Carpenter J.S., Tu W. The association of depression and pain with health-related quality of life, disability, and health care use in cancer patients. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2010;40:327–341. [CrossRef]

- Ośmiałowska E., Misiąg W., Chabowski M., Jankowska-Polańska B. Coping Strategies, Pain, and Quality of Life in Patients with Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2021;10:4469. [CrossRef]

- Pérez C, Ochoa D, Sánchez N, Ballesteros AI, Santidrián S, López I, Mondéjar R, Carnaval T, Villoria J, Colomer R. Pain in Long-Term Cancer Survivors: Prevalence and Impact in a Cohort Composed Mostly of Breast Cancer Survivors. Cancers (Basel). 2024 Apr 20;16(8):1581. PMID: 38672663; PMCID: PMC11049399 . [CrossRef]

- Hamilton GR, Baskett TF. In the arms of Morpheus the development of morphine for postoperative pain relief. Can J Anaesth. 2000 Apr;47(4):367-74. PMID: 10764185 . [CrossRef]

- Berridge V. Heroin prescription and history. N Engl J Med. 2009 Aug 20;361(8):820-1. PMID: 19692694 . [CrossRef]

- Brook K, Bennett J, Desai SP. The Chemical History of Morphine: An 8000-year Journey, from Resin to de-novo Synthesis. J Anesth Hist. 2017 Apr;3(2):50-55. Epub 2017 Apr 5. PMID: 28641826 . [CrossRef]

- Laing R, Donnelly CA. Evolution of an epidemic: Understanding the opioid epidemic in the United States and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on opioid-related mortality. PLoS One. 2024 Jul 9;19(7):e0306395. PMID: 38980856; PMCID: PMC11233025 . [CrossRef]

- Paice JA. Cancer pain management and the opioid crisis in America: How to preserve hard-earned gains in improving the quality of cancer pain management. Cancer. 2018 Jun 15;124(12):2491-2497. Epub 2018 Mar 2. PMID: 29499072 . [CrossRef]

- Ventafridda V, Saita L, Ripamonti C, De Conno F. WHO guidelines for the use of analgesics in cancer pain. Int J Tissue React. 1985;7(1):93-6. PMID: 2409039.

- Wilson J, Stack C, Hester J. Recent advances in cancer pain management. F1000Prime Rep. 2014 Feb 3;6:10. PMID: 24592322; PMCID: PMC3913037 . [CrossRef]

- Kettyle G. Multidisciplinary Approach to Cancer Pain Management. Ulster Med J. 2023 Jan;92(1):55-58. Epub 2023 Jan 6. PMID: 36762129; PMCID: PMC9899029.

- Falk S, Bannister K, Dickenson AH. Cancer pain physiology. Br J Pain. 2014 Nov;8(4):154-62. PMID: 26516549; PMCID: PMC4616725 . [CrossRef]

- Pahuta M, Laufer I, Lo SL, et al. Defining Spine Cancer Pain Syndromes: A Systematic Review and Proposed Terminology. Global Spine Journal. 2025;15(1_suppl):81S-92S. [CrossRef]

- Haroun R, Wood JN, Sikandar S. Mechanisms of cancer pain. Front Pain Res (Lausanne). 2023 Jan 4;3:1030899. PMID: 36688083; PMCID: PMC9845956 . [CrossRef]

- Coleman RE. Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity. Clin Cancer Res. 2006 Oct 15;12(20 Pt 2):6243s-6249s. PMID: 17062708 . [CrossRef]

- Foley KM. Treatment of cancer-related pain. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;(32):103-4. PMID: 15263049 . [CrossRef]

- Lipton A. Pathophysiology of bone metastases: how this knowledge may lead to therapeutic intervention. J Support Oncol. (2004) 2(3):205–13; discussion 13–4, 16–7, 19–20. PMID: 15328823.

- Jones DH, Nakashima T, Sanchez OH, Kozieradzki I, Komarova SV, Sarosi I, et al. Regulation of cancer cell migration and bone metastasis by RANKL. Nature. (2006) 440(7084):692–6. [CrossRef]

- Akech J, Wixted JJ, Bedard K, van der Deen M, Hussain S, Guise TA, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Languino LR, Altieri DC, Pratap J, Keller E, Stein GS, Lian JB. Runx2 association with progression of prostate cancer in patients: mechanisms mediating bone osteolysis and osteoblastic metastatic lesions. Oncogene. 2010 Feb 11;29(6):811-21. Epub 2009 Nov 16. PMID: 19915614; PMCID: PMC2820596 . [CrossRef]

- Eliasson P, Jönsson JI. The hematopoietic stem cell niche: low in oxygen but a nice place to be. J Cell Physiol. 2010 Jan;222(1):17-22. PMID: 19725055 . [CrossRef]

- Regan JM, Peng P. Neurophysiology of cancer pain. Cancer Control. 2000;7(2):111-119.

- Sikandar S, Dickenson AH. Visceral pain – the ins and outs, the ups and downs. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2012;6(1):17-26.

- Wang L, Xu H, Ge Y, et al. Establishment of a murine pancreatic cancer pain model and microarray analysis of pain-associated genes in the spinal cord dorsal horn. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16(4):4429-4436. [CrossRef]

- Lam DK, Schmidt BL. Serine proteases and protease-activated receptor 2-dependent allodynia: a novel cancer pain pathway. Pain. 2010;149(2):263-272. [CrossRef]

- Edwards HL, Mulvey MR, Bennett MI. Cancer-Related Neuropathic Pain. Cancers (Basel). 2019 Mar 16;11(3):373. PMID: 30884837; PMCID: PMC6468770 . [CrossRef]

- Yoon SY, Oh J. Neuropathic cancer pain: prevalence, pathophysiology, and management. Korean J Intern Med. 2018 Nov;33(6):1058-1069. Epub 2018 Jun 25. PMID: 29929349; PMCID: PMC6234399 . [CrossRef]

- Rayment C, Hjermstad MJ, Aass N, et al. Neuropathic cancer pain: prevalence, severity, analgesics and impact from the European Palliative Care Research Collaborative-Computerised Symptom Assessment study. Palliat Med. 2013;27(8):714-721. [CrossRef]

- Delanian S, Lefaix JL, Pradat PF. Radiation-induced neuropathy in cancer survivors. Radiother Oncol. 2012;105(3):273-282. [CrossRef]

- Portenoy RK, Ahmed E. Cancer Pain Syndromes. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2018 Jun;32(3):371-386. Epub 2018 Mar 22. PMID: 29729775 . [CrossRef]

- Paice JA, Portenoy R, Lacchetti C, et al. Management of Chronic Pain in Survivors of Adult Cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(27):3325-45.

- Bennett MI, Kaasa S, Barke A, Korwisi B, Rief W, Treede RD; IASP Taskforce for the Classification of Chronic Pain. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic cancer-related pain. Pain. 2019 Jan;160(1):38-44. [CrossRef]

- Fink RM, Gallagher E. Cancer Pain Assessment and Measurement. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2019 Jun;35(3):229-234. Epub 2019 Apr 26. PMID: 31036386 . [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen R, Liubarskiene Z, Møldrup C, Christrup L, Sjøgren P, Samsanavieiene J. Barriers to cancer pain management: a review of empirical research. Medicina (Kaunas) 2009;45(6):427–33.

- Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, Caraceni A, Hanks GW, Loge JH, Fainsinger R, Aass N, Kaasa S; European Palliative Care Research Collaborative (EPCRC). Studies comparing Numerical Rating Scales, Verbal Rating Scales, and Visual Analogue Scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011 Jun;41(6):1073-93. [CrossRef]

- Correll, Darin J. The Measurement of Pain: Objectifying the Subjective. Steven D. Waldman, MD, JD. Pain Management. 2nd. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2011. 191-201.

- Main, Chris J. Pain Assessment in Context: A State of the Science Review of the McGill Pain Questionnaire 40 years on. Pain. July 2016. 157(7):1387-1399.

- Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994 Mar. 23(2):129-38.

- Kaasalainen S. Pain assessment in older adults with dementia: using behavioral observation methods in clinical practice. J Gerontol Nurs. 2007 Jun;33(6):6-10. [CrossRef]

- van Herk R, van Dijk M, Baar FP, Tibboel D, de Wit R. Observation scales for pain assessment in older adults with cognitive impairments or communication difficulties. Nurs Res. 2007 Jan-Feb;56(1):34-43. [CrossRef]

- Lemaire A, George B, Maindet C, Burnod A, Allano G, Minello C. Opening up disruptive ways of management in cancer pain: the concept of multimorphic pain. Support Care Cancer. 2019 Aug;27(8):3159-3170. [CrossRef]

- Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Backonja M, Farrar JT, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS, Kalso EA, Loeser JD, Miaskowski C, Nurmikko TJ, Portenoy RK, Rice ASC, Stacey BR, Treede RD, Turk DC, Wallace MS. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations. Pain. 2007 Dec 5;132(3):237-251. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Schaffer G. Is the WHO analgesic ladder still valid? Twenty-four years of experience. Can Fam Physician. 2010 Jun;56(6):514-7, e202-5. PMID: 20547511; PMCID: PMC2902929.

- Gómez-Cortéz MD, Rodríguez-Huertas F. Reevaluación del segundo escalón de la escalera analgésica de la OMS. Rev Soc Esp Dolor. 2000;7(6):343–4.

- Vargas-Schaffer G. Tratamiento del dolor oncologico y cuidados paliativos en pediatría. In: Morales Pola EA, editor. Manual de clinica del dolor y cuidados paliativos. Chiapas, Mexico: Universidad autonoma de Chiapas; 2002. pp. 195–206.

- Vargas-Schaffer G, Godoy D. Conceptos básicos del uso de opioides en el tratamiento del dolor oncológico. Rev Venez Oncol. 2004;16(2):103–14.

- Bruera E, Palmer JL, Bosnjak S, Rico MA, Moyano J, Sweeney C, et al. Methadone versus morphine as a first-line strong opioid for cancer pain: a randomized double-blind study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(1):185–92. [CrossRef]

- Clark AJ, Lynch ME, Ware M, Beaulieu P, McGilveray IJ, Gourlay D. Guidelines for the use of cannabinoid compounds in chronic pain. Pain Res Manage. 2005;10(Suppl A):44A–6A. [CrossRef]

- Moulin DE, Clark AJ, Gilron I, Ware MA, Watson CP, Sessle BJ, et al. Pharmacological management of chronic neuropathic pain—consensus statement and guidelines from the Canadian Pain Society. Pain Res Manag. 2007;12(1):13–21. [CrossRef]

- Mercadante S. The use of anti-inflammatory drugs in cancer pain. Cancer treatment reviews. 2001 Feb 1;27(1):51-61.

- Howard A, Brant JM. Pharmacologic management of cancer pain. InSeminars in Oncology Nursing 2019 Jun 1 (Vol. 35, No. 3, pp. 235-240). WB Saunders.

- Kane CM, Mulvey MR, Wright S, Craigs C, Wright JM, Bennett MI. Opioids combined with antidepressants or antiepileptic drugs for cancer pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliative medicine. 2018 Jan;32(1):276-86.

- Leppert W, Buss T. The role of corticosteroids in the treatment of pain in cancer patients. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012 Aug;16(4):307-13. [CrossRef]

- Nersesyan H, Slavin KV. Current aproach to cancer pain management: Availability and implications of different treatment options. Therapeutics and clinical risk management. 2007 Jun 30;3(3):381-400.

- Jose A, Thomas L, Baburaj G, Munisamy M, Rao M. Cannabinoids as an Alternative Option for Conventional Analgesics in Cancer Pain Management: A Pharmacogenomics Perspective. Indian J Palliat Care. 2020 Jan-Mar;26(1):129-133. [CrossRef]

- Body JJ, Mancini I. Bisphosphonates for cancer patients: why, how, and when? Support Care Cancer. 2002 Jul;10(5):399-407. [CrossRef]

- Wong R, Wiffen PJ. Bisphosphonates for the relief of pain secondary to bone metastases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;2002(2):CD002068. [CrossRef]

- Hamdy NA. Denosumab: RANKL inhibition in the management of bone loss. Drugs Today (Barc). 2008 Jan;44(1):7-21. [CrossRef]

- Tsourdi E, Rachner TD, Rauner M, Hamann C, Hofbauer LC. Denosumab for bone diseases: translating bone biology into targeted therapy. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011 Dec;165(6):833-40. Epub 2011 Aug 18. Erratum in: Eur J Endocrinol. 2012 Jan;166(1):137. PMID: 21852390 . [CrossRef]

- Choi E, Nahm FS, Han WK, Lee PB, Jo J. Topical agents: a thoughtful choice for multimodal analgesia. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2020 Oct;73(5):384-393. [CrossRef]

- Davis MP. Novel drug treatments for pain in advanced cancer and serious illness: a focus on neuropathic pain and chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Palliat Care Soc Pract. 2024 Jul 31;18:26323524241266603. [CrossRef]

- Sah D, Shoffel-Havakuk H, Tsur N, Uhelski ML, Gottumukkala V, Cata JP. Opioids and Cancer: Current Understanding and Clinical Considerations. Curr Oncol. 2024 May 30;31(6):3086-3098. [CrossRef]

- Portenoy RK, Hagen NA. Breakthrough pain: definition, prevalence and characteristics. Pain. 1990 Jun 1;41(3):273-81.

- Boland JW. Tapentadol for the management of cancer pain in adults: an update. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2023 Jun 1;17(2):90-97. [CrossRef]

- Fallon M, Giusti R, Aielli F, Hoskin P, Rolke R, Sharma M, Ripamonti CI; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Management of cancer pain in adult patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2018 Oct 1;29(Suppl 4):iv166-iv191. [CrossRef]

- Leppert W. Tramadol as an analgesic for mild to moderate cancer pain. Pharmacol Rep. 2009 Nov-Dec;61(6):978-92. [CrossRef]

- Arbaiza D, Vidal O. Tramadol in the treatment of neuropathic cancer pain: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Drug Investig. 2007;27(1):75-83. [CrossRef]

- Straube C, Derry S, Jackson KC, Wiffen PJ, Bell RF, Strassels S, Straube S. Codeine, alone and with paracetamol (acetaminophen), for cancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Sep 19;2014(9):CD006601. [CrossRef]

- Leppert W. Dihydrocodeine as an opioid analgesic for the treatment of moderate to severe chronic pain. Curr Drug Metab. 2010 Jul;11(6):494-506. [CrossRef]

- Penson RT, Joel SP, Gloyne A, Clark S, Slevin ML. Morphine analgesia in cancer pain: role of the glucuronides. J Opioid Manag. 2005 May-Jun;1(2):83-90. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Hansen M, Bennett MI, Arnold S, Bromham N, Hilgart JS. Oxycodone for cancer-related pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Aug 22;8(8):CD003870. [CrossRef]

- Quigley C, Wiffen P. A systematic review of hydromorphone in acute and chronic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003 Feb;25(2):169-78. [CrossRef]

- Hadley G, Derry S, Moore RA, Wiffen PJ. Transdermal fentanyl for cancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Oct 5;2013(10):CD010270. [CrossRef]

- Mammana G, Bertolino M, Bruera E, Orellana F, Vega F, Peirano G, Bunge S, Armesto A, Dran G. First-line methadone for cancer pain: titration time analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2021 Nov;29(11):6335-6341. [CrossRef]

- Samet JH, Botticelli M, Bharel M. Methadone in Primary Care - One Small Step for Congress, One Giant Leap for Addiction Treatment. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 5;379(1):7-8. [CrossRef]

- Paice JA, Bohlke K, Barton D, Craig DS, El-Jawahri A, Hershman DL, Kong LR, Kurita GP, LeBlanc TW, Mercadante S, Novick KLM, Sedhom R, Seigel C, Stimmel J, Bruera E. Use of Opioids for Adults With Pain From Cancer or Cancer Treatment: ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2023 Feb 1;41(4):914-930. [CrossRef]

- Huang R, Jiang L, Cao Y, Liu H, Ping M, Li W, Xu Y, Ning J, Chen Y, Wang X. Comparative Efficacy of Therapeutics for Chronic Cancer Pain: A Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Jul 10;37(20):1742-1752. [CrossRef]

- Chou R, Clark E, Helfand M. Comparative efficacy and safety of long-acting oral opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003 Nov;26(5):1026-48. [CrossRef]

- Jost L, Roila F, ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Management of cancer pain: ESMO clinical recommendations. Ann Oncol 2008; 19 Suppl 2:ii119.

- Cormie PJ, Nairn M, Welsh J, Guideline Development Group. Control of pain in adults with cancer: summary of SIGN guidelines. BMJ 2008; 337:a2154.

- Reddy A, Yennurajalingam S, Pulivarthi K, Palla SL, Wang X, Kwon JH, Frisbee-Hume S, Bruera E. Frequency, outcome, and predictors of success within 6 weeks of an opioid rotation among outpatients with cancer receiving strong opioids. Oncologist. 2013;18(2):212-20. [CrossRef]

- Caraceni A, Martini C, Zecca E, et al.; Working Group of an IASP Task Force on Cancer Pain. Breakthrough pain characteristics and syndromes in patients with cancer pain. An international survey. Palliat Med. 2004 Apr;18(3):177-83. [CrossRef]

- Kurita GP, Sjøgren P, Klepstad P, Mercadante S. Interventional Techniques for the Management of Cancer-Related Pain: Clinical and Critical Aspects. Cancers. 2019; 11(4):443. [CrossRef]

- Habib MH, Schlögl M, Raza S, Chwistek M, Gulati A. Interventional pain management in cancer patients-a scoping review. Ann Palliat Med. 2023 Nov;12(6):1198-1214. [CrossRef]

- Mao JJ, Ismaila N, Bao T et al.Integrative Medicine for Pain Management in Oncology: Society for Integrative Oncology-ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2022 Dec 1;40(34):3998-4024. [CrossRef]

- Calapai F, Mondello E, Mannucci C, Sorbara EE, Gangemi S, Quattrone D, Calapai G, Cardia L. Pain Biomarkers in Cancer: An Overview. Curr Pharm Des. 2021;27(2):293-304. [CrossRef]

- Mackey S, Aghaeepour N, Gaudilliere B, Kao MC, Kaptan M, Lannon E, Pfyffer D, Weber K. Innovations in acute and chronic pain biomarkers: enhancing diagnosis and personalized therapy. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2025 Feb 5;50(2):110-120. [CrossRef]

- Carlson CL. Effectiveness of the World Health Organization cancer pain relief guidelines: an integrative review. Journal of pain research. 2016 Jul 22:515-34.

- Hui D, Bruera E. A personalized approach to assessing and managing pain in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Jun 1;32(16):1640-6. [CrossRef]

- Raad M, López WOC, Sharafshah A, Assefi M, Lewandrowski KU. Personalized Medicine in Cancer Pain Management. J Pers Med. 2023 Jul 28;13(8):1201. [CrossRef]

- Nijs J, Lahousse A, Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C et al. Towards precision pain medicine for pain after cancer: the Cancer Pain Phenotyping Network multidisciplinary international guidelines for pain phenotyping using nociplastic pain criteria. Br J Anaesth. 2023 May;130(5):611-621. [CrossRef]

- Giraud F, Pereira E, Anizon F, Moreau P. Recent Advances in Pain Management: Relevant Protein Kinases and Their Inhibitors. Molecules. 2021; 26(9):2696. [CrossRef]

- Yousuf MS, Shiers SI, Sahn JJ, Price TJ. Pharmacological manipulation of translation as a therapeutic target for chronic pain. Pharmacological reviews. 2021 Jan 1;73(1):59-88.

- Mantyh, P.W.; Koltzenburg, M.; Mendell, L.M.; Tive, L.; Sheldon, D.L. Antagonism of nerve growth factor-TrkA signaling and the relief of pain. Anesthesiology 2011, 115, 189–204.

- Sopata M, Katz N, Carey W, Smith MD, Keller D, Verburg KM, West CR, Wolfram G, Brown MT. Efficacy and safety of tanezumab in the treatment of pain from bone metastases. Pain. 2015 Sep;156(9):1703-1713. PMID: 25919474 . [CrossRef]

- Felix R, Corzo-Lopez A, Sandoval A. Voltage-Gated Ion Channels in Neuropathic Pain Signaling. Life. 2025; 15(6):888. [CrossRef]

- Coluzzi F, Scerpa MS, Alessandri E, Romualdi P, Rocco M. Role of TRP Channels in Cancer-Induced Bone Pain. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(3):1229. [CrossRef]