1. Introduction

The extensive generation of data across various domains—including scientific research, commercial activities, and social platforms—has markedly transformed the landscape of data analytics. This transformation necessitates sophisticated frameworks capable of extracting valuable insights from vast, heterogeneous datasets. A pivotal aspect in this endeavor is ensuring data quality, as it directly impacts the reliability and precision of analyses conducted thereafter. Consequently, the process of data cleaning has ascended to a critical preliminary stage within preprocessing workflows. Its primary role includes addressing inconsistencies, rectifying errors, managing missing entries, and discarding irrelevant attributes, thus preparing datasets for subsequent analytical processes [

1,

2].

However, traditional approaches to data cleaning encounter considerable challenges in the context of modern data environments, characterized by their sheer volume, swift generation pace, and intricate structures. These challenges call for adaptive strategies adept at managing the complexities inherent in big data scenarios. The exploratory phase holds particular significance as it involves uncovering hidden patterns, structural inconsistencies, and outliers within datasets. Contemporary techniques employ a combination of statistical analysis and visualization-driven methodologies—such as clustering algorithms and automated anomaly detection—to identify irregularities within data [

3,

4]. Additionally, feature exploration utilizes dimensionality reduction methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE), which transform complex high-dimensional datasets into more interpretable visual forms, thereby facilitating intuitive comprehension [

5,

6].

Addressing missing data presents a formidable challenge within the realm of data cleaning, as incomplete records can distort analytical results. A foundational understanding of the mechanisms underlying missingness—such as Missing Completely at Random (MCAR), Missing at Random (MAR), and Missing Not at Random (MNAR)—informs the selection of appropriate imputation strategies [

7]. Current methodologies range from simple techniques like mean or median substitution to sophisticated model-based frameworks, including k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) and Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE), both designed to restore missing values while preserving the dataset’s statistical properties [

8,

9].

Feature selection is instrumental in enhancing data quality, as it involves identifying variables that significantly contribute to predictive modeling. This process can be broadly categorized into three approaches: filter-based, wrapper-based, and embedded methods [

10]. Filter methods assess feature relevance through statistical measures independent of any model, whereas wrapper techniques evaluate subsets of features via iterative model training and validation. Embedded methodologies integrate the feature selection process within the learning algorithm itself, exemplified by regularization approaches like LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) and Ridge regression that aim to balance model complexity for optimal predictive performance [

11,

12].

The transition from conventional data cleaning techniques to modern computational frameworks highlights the necessity of scalable solutions in today’s big data landscape. Ensemble learning algorithms, such as Random Forest and Gradient Boosting, have gained prominence for their dual roles in feature selection and handling missing data. Random Forest employs an ensemble aggregation of decision trees to implicitly rank features and includes mechanisms for imputing missing values [

13]. On the other hand, Gradient Boosting focuses on refining predictions by iteratively minimizing residual errors and incorporates feature selection within its boosting framework [

14].

Recent advancements in data cleaning have increasingly utilized artificial intelligence and machine learning to automate and refine preprocessing tasks. Deep learning architectures, particularly neural networks, have demonstrated efficacy in nonlinear imputation and anomaly detection, offering scalable solutions for complex data structures [

15]. Autoencoders, a type of unsupervised neural network model, are adept at detecting and correcting data irregularities by learning compressed representations that retain essential information [

16].

Recent advancements in large language models have further introduced complex challenges in the domain of scientific content generation, particularly with regard to the integrity and reliability of automatically produced academic material. The emergence of domain-specific preprints generated with minimal human oversight exemplifies this trend, spanning topics from adversarial attacks on wireless networks [

17], to fraud detection systems leveraging machine learning techniques [

18], and even assessments of cryptographic resilience in the post-quantum era [

19]. Additional works have explored the intersection of IoT and AI in applications such as indoor localization [

20] and cloud service architectures tailored for pervasive sensing environments [

21]. While these outputs adhere to formal academic standards and maintain topical relevance, they underscore the necessity of reinforcing fairness and accountability—both within the models that generate knowledge and in the broader ecosystem where such content is disseminated. In summary, the escalating complexity and scale of big data underscore the critical need for multidisciplinary approaches to data cleaning. By integrating statistical principles with advancements in machine learning and artificial intelligence, contemporary methodologies effectively tackle the diverse challenges associated with large-scale data analysis. This review provides a comprehensive examination of these cutting-edge techniques, underscoring their potential to enhance data quality and ensure robust analytical outcomes within the big data paradigm.

2. Methods

The methodologies employed in constructing advanced data cleaning pipelines for big data analytics are grounded in a systematic approach that integrates a variety of computational techniques. This section delineates the procedures and algorithms utilized to enhance data quality, focusing on data exploration, handling missing values, and feature selection. Our discussion provides concrete examples, illustrating how these methodologies are applied in practice to prepare datasets for subsequent analysis.

2.1. Data Exploration

Data exploration is the initial step in the data cleaning process, essential for understanding the underlying structure and nuances of the dataset. This stage often employs a blend of statistical summaries and visualization techniques to identify outliers, trends, and data distribution patterns. For instance, consider a dataset comprising customer transaction records for a retail organization. The exploration phase involves generating descriptive statistics such as mean, median, standard deviation, and variance for key variables like transaction amount and customer age. Visualization tools, such as histograms and scatter plots, are utilized to visually spot anomalies and relationships between different variables [

5].

To manage high-dimensional data, dimensionality reduction techniques like PCA are frequently applied. PCA transforms the original variables into principal components, which are linear combinations optimized to capture the maximum variance within the dataset. This process aids in visualizing the structure of the data by reducing it to two or three dimensions, thus assisting in identifying clusters and outliers that may warrant further examination [

6].

2.2. Handling Missing Values

Missing data is a prevalent issue that can significantly impair the quality of analytical insights. Addressing this challenge involves determining the nature of the missingness and selecting appropriate imputation techniques. In a practical scenario, such as patient data in a healthcare database, missing values might occur due to various reasons, including unrecorded values or data corruption. The initial step is to assess whether the data is Missing Completely at Random (MCAR), Missing at Random (MAR), or Missing Not at Random (MNAR) [

7].

For data assumed to be MCAR or MAR, imputation strategies like Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) or k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) are commonly employed. MICE generates multiple datasets by imputing missing values based on predictive models, ensuring that the uncertainty of imputed values is adequately represented [

9]. In the context of our healthcare dataset, MICE could be used to fill in gaps for patient measurements based on other correlated measurements. Alternatively, k-NN imputation substitutes missing values using averages of the nearest neighbors in the feature space, leveraging the similarity between patient records to approximate missing data effectively [

8].

2.3. Feature Selection

Feature selection is critical to improving the performance of predictive models by identifying the most relevant variables. This process not only reduces computational complexity but also enhances model interpretability. Various methods are applied, including filter, wrapper, and embedded methods. For example, in a financial fraud detection system, feature selection might involve using algorithms such as Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with a decision tree model to determine which transaction attributes most effectively contribute to identifying fraudulent activities [

10].

Embedded methods, such as those exemplified by the LASSO regression model, automatically perform variable selection during model training by applying a penalty to the coefficients of less important features. This approach is highly effective in scenarios where multicollinearity is present, as it inherently reduces the dataset’s dimensionality while retaining those features that contribute the most to prediction accuracy [

11]. Similarly, ensemble methods like Random Forest provide inherent feature importance scores, guiding the selection of features that significantly contribute to the classification or regression tasks [

13].

2.4. Integration of Algorithms

The integration of these methods within a cohesive data cleaning pipeline is critical for ensuring maximal data utility and analytical accuracy. Consider the case of preparing an environmental dataset collected from sensor arrays distributed across various geographic locations. Initially, data exploration techniques are applied to understand environmental patterns and identify anomalies related to sensor malfunctions or data transmission errors. Subsequently, missing sensor readings are imputed using model-based techniques like MICE to maintain temporal continuity in analyses like climate modeling.

Feature selection then narrows down the vast array of potential environmental attributes to those most relevant for modeling purposes. In this scenario, the use of RFE with a Gradient Boosting Machine to refine the features ensures that computational resources are optimized, and the most influencing environmental factors are prioritized for subsequent analyses [

14].

In conclusion, advanced data cleaning methodologies constitute a multi-step approach that integrates exploration, imputation, and feature selection to optimize data quality. By utilizing a combination of established statistical practices and modern algorithmic techniques, these pipelines prepare data for robust analytical applications across diverse fields, thus underpinning high-quality insights and strategic decision-making.

3. Innovative Approaches for Data Exploration

The exploration phase within data analysis is fundamental to revealing obscure insights and anomalies in intricate datasets. Beyond conventional statistical summaries, modern methodologies incorporate machine learning models and sophisticated visualization techniques, thereby deepening our comprehension of data structures. Prominently, clustering algorithms such as K-means and DBSCAN have become powerful instruments in exploratory analysis. These tools facilitate the categorization of data into coherent groups while uncovering intrinsic patterns [

3].

For instance, in the context of marketing, K-means clustering is instrumental in dissecting consumer behavior to pinpoint distinct purchasing trends. Businesses leverage this method to segment customers based on common attributes like transaction frequency and average expenditure. The selection of an optimal number of clusters typically involves the elbow criterion, which strikes a balance between model complexity and explanatory power, thus preventing overfitting. This technique allows companies to develop precise marketing strategies by identifying homogeneous consumer segments [

22].

The challenge posed by high-dimensional data can be addressed through dimensionality reduction techniques. While Principal Component Analysis (PCA) remains prevalent, other methods such as Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) and non-linear approaches like Locally Linear Embedding (LLE) provide substantial advantages. In fields such as image processing, LLE is particularly beneficial as it maintains the geometric relationships in pixel data, thereby improving tasks like facial recognition by minimizing noise and redundancy [

23].

Visualization plays a pivotal role in transforming abstract data into actionable insights. Tools such as Tableau and Power BI offer interactive environments that enable users to engage with datasets dynamically. These platforms support the creation of adaptive dashboards, which respond in real-time to user interactions, thereby expediting strategic decision-making processes. By utilizing these advanced technologies, analysts can identify latent patterns that underpin effective data preprocessing strategies [

24].

4. Innovative Imputation Methods for Missing Data

Current trends in managing missing data emphasize model-based and machine learning-driven techniques for imputation. Traditional methods, such as mean or median imputation, can offer simplistic solutions but often at the cost of introducing biases into the dataset. Instead, advanced imputation methods leverage the predictive power of supervised learning algorithms to estimate missing values more accurately.

One such example is the use of matrix factorization methods, such as Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) and Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF), which decompose the data matrix into lower-dimensional matrices to reconstruct missing entries. These techniques are particularly useful in recommendation systems, where they can predict user preferences by filling in missing ratings [

25].

Moreover, ensemble learning methods, specifically MissForest—a random forest-based algorithm—have shown promise in accurately imputing mixed-type data. MissForest iteratively estimates missing values using a set of randomized decision trees, exploiting both numerical and categorical feature relationships [

26]. In medical research, we observe the use of MissForest for handling missing clinical data, leading to more reliable patient outcome predictions without being hindered by incomplete records.

Furthermore, deep learning models, particularly Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), are being explored for data imputation. GANs can model complex distributions by generating synthetic samples that mimic the original dataset structure, offering an innovative approach for filling in missing data, especially in multimodal datasets such as text and image data [

27]. These cutting-edge imputation methods provide robust frameworks for dealing with missing data, ensuring data integrity and enhancing the subsequent analyses’ validity.

5. Strategic Feature Selection Paradigms

The formulation of robust predictive models is intrinsically linked to the meticulous identification of pivotal features, especially in contexts involving datasets with extensive dimensionality. As an essential phase of data preprocessing, feature selection incorporates a broad spectrum of methodologies aimed at boosting model efficacy and enhancing interpretability. Notably, the practice of ranking features emerges as a vital technique, providing a quantifiable assessment of each variable’s significance in relation to a specific goal. In classification scenarios, this process typically employs statistical measures such as mutual information and chi-square tests—concepts thoroughly investigated in seminal works on feature selection [

28].

Within the bioinformatics sector, characterized by datasets rich with numerous gene expression markers, integrating recursive feature elimination (RFE) with classifiers like support vector machines (SVMs) has demonstrated its efficacy as a potent method for pinpointing biologically relevant biomarkers [

29]. This technique incrementally discards less pertinent features in an iterative fashion, thereby bolstering classification precision while concurrently simplifying model complexity through deliberate dimensionality reduction.

A noteworthy progression in feature selection is the advent of embedded methods that seamlessly incorporate variable selection into the model training phase. LASSO regression exemplifies this category, utilizing L1 regularization to concurrently perform feature selection and model regularization—a dual advantage crucial in financial risk modeling where both stability and interpretability are paramount [

11].

In the landscape of big data analytics, cutting-edge tools like Boruta have been devised to gauge feature importance. By juxtaposing the performance of original features against randomly created "shadow" variables during model training, Boruta adeptly distinguishes genuinely significant predictors from extraneous noise [

30]. These varied methodologies underscore the necessity of leveraging domain-specific frameworks for feature selection to enhance predictive modeling across diverse disciplines, ensuring that data preparation is closely aligned with analytical goals and anticipated results.

In conclusion, embracing these sophisticated feature selection techniques embodies a progressive strategy to navigate the intricacies inherent in large-scale datasets. By embedding such methods into data preprocessing workflows, researchers not only refine data quality but also lay down a systematic groundwork for deriving actionable insights and underpinning evidence-based decision-making processes.

6. Empirical Observations and Comparative Evaluation

This investigation provides a comprehensive evaluation of various data preprocessing techniques across multiple datasets. The focus is on their efficacy in exploratory data analysis, managing missing values, and determining feature relevance. Through thorough empirical assessments, this study offers quantitative insights into the effectiveness of different algorithmic methods, supported by both numerical measures and visual depictions.

6.1. Exploration Through Unsupervised Learning

This subsection delves into the performance of clustering (K-means, DBSCAN) and dimensionality reduction (PCA) techniques in revealing latent data structures and detecting anomalies.

Table 1 displays a comparative evaluation of these methods applied to a dataset from retail transactions, with metrics assessing their proficiency in forming consistent clusters and identifying outliers.

The analysis reveals that DBSCAN’s density-based strategy is particularly adept at outlier detection, especially in scenarios with diverse cluster configurations. The combination of PCA followed by K-means shows a commendable balance between enhancing cluster separation and reducing false positives in anomaly detection [

3].

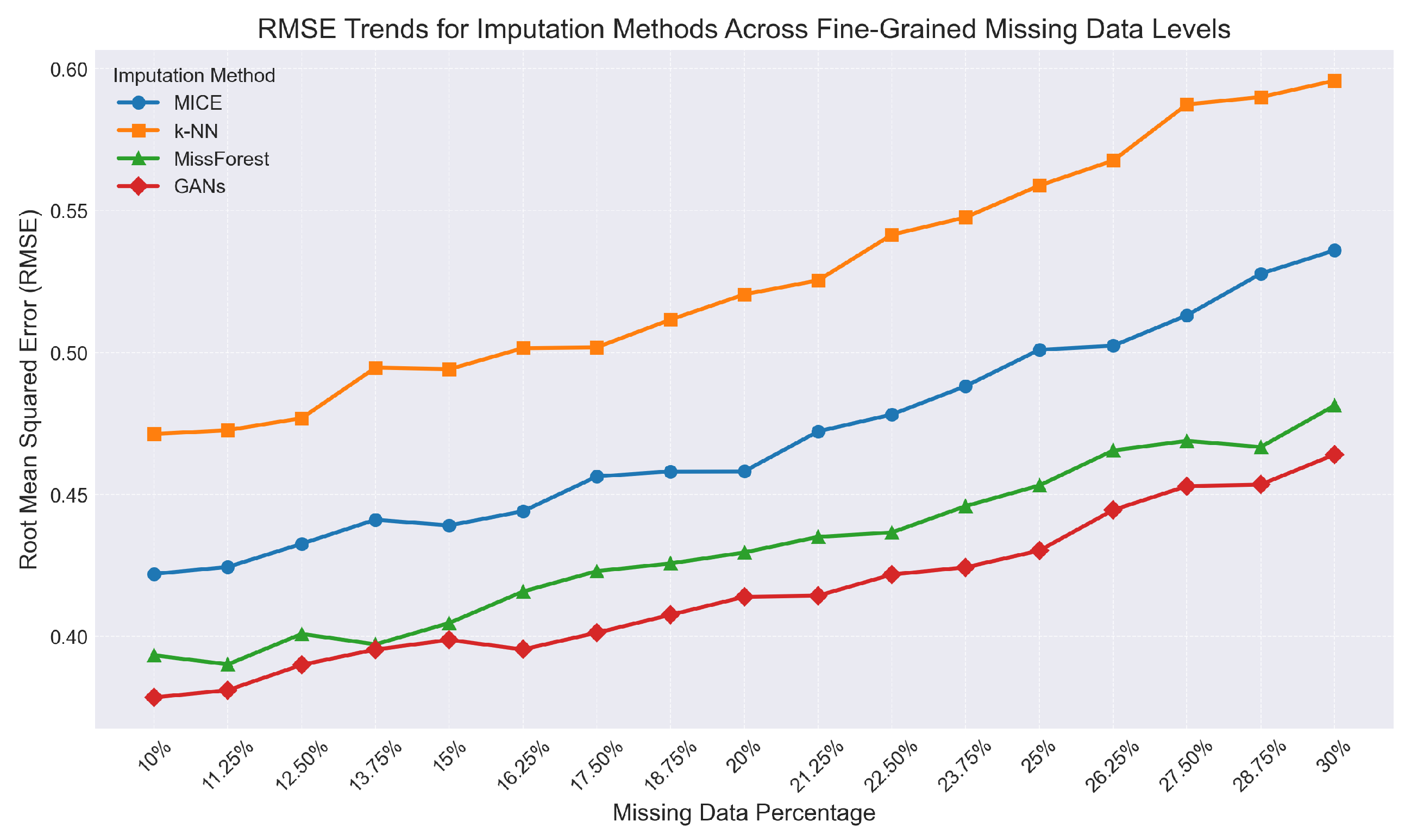

6.2. Balancing Computational Load and Accuracy in Missing Data Imputation

This subsection examines the performance of imputation algorithms (MICE, k-NN, MissForest, GANs) on a healthcare dataset with artificially induced missingness at 10%, 20%, and 30%. The evaluation is based on RMSE values and computational efficiency, as detailed in

Table 2 and illustrated in

Figure 1.

The results indicate that tree-based imputation (MissForest) and generative adversarial networks (GANs) provide the highest accuracy across all levels of missingness, though with a substantial increase in computational demand. This underscores the necessity of balancing precision needs with considerations for scalability [

27].

6.3. Optimizing Feature Selection: Precision Versus Efficiency

This subsection evaluates the efficacy of feature selection algorithms (RFE, LASSO, Boruta) on a synthetic bioinformatics dataset with predefined predictive relationships. The assessment focuses on three key metrics: the number of selected features, model accuracy, and computational time, as summarized in

Table 3.

The findings demonstrate that Boruta’s permutation-based method achieves the highest model accuracy and F1-score, indicating its effectiveness in identifying biologically significant features while minimizing noise. Conversely, LASSO is noted for its computational efficiency in high-dimensional datasets due to its ability to induce sparsity [

11,

30].

6.4. Integration of Empirical Insights

The detailed empirical analysis highlights the complex interplay between algorithmic precision, computational demands, and domain-specific requirements in data preprocessing. The results emphasize that unsupervised learning techniques are particularly valuable for understanding data structure and detecting anomalies, while advanced imputation methods enhance accuracy at the expense of increased resource usage.

In feature selection, the balance between model performance and computational efficiency underscores the importance of selecting algorithms that align with specific analytical objectives and dataset characteristics. These insights collectively support the development of adaptive preprocessing pipelines that dynamically reconcile analytical thoroughness with practical constraints.

The evidence presented here reinforces the critical need to customize data cleaning protocols according to the unique features of each dataset and the goals of subsequent analyses, ensuring that preprocessing steps maintain the integrity and efficacy of downstream modeling efforts.

7. Discussion

This section critically examines the empirical findings concerning contemporary data cleaning frameworks within the realm of big data analytics. Herein, we dissect both their strengths and limitations, drawing attention to practical considerations for implementation challenges as well as trends in the evolution of data preprocessing technologies.

7.1. Interpretation of Results

Through a comparative analysis, this study delves into several exploratory data analysis methodologies—including K-means clustering, DBSCAN, and PCA—to elucidate their pivotal roles in unearthing latent patterns within extensive datasets. Particularly, DBSCAN stands out for its robust anomaly detection capabilities in environments characterized by non-uniform data distribution, thus proving advantageous in multifaceted, heterogeneous contexts [

3]. Nonetheless, this adaptability comes at the cost of heightened computational demands, posing significant hurdles for real-time analytics or systems with limited resources.

The examination of imputation strategies unveils a nuanced interplay between precision and computational feasibility. State-of-the-art techniques such as MissForest and GAN-based methodologies have demonstrated exceptional accuracy in maintaining statistical robustness, especially when faced with substantial missing data [

26,

27]. While GANs excel at replicating intricate data distributions, their intensive resource requirements necessitate careful consideration of their applicability within specific operational contexts.

Within feature selection, our research reaffirms the efficacy of regularization-based embedded strategies such as LASSO in reducing overfitting risks through penalization mechanisms [

11]. The Boruta algorithm also emerges as a dependable alternative, systematically identifying variables that contribute to model interpretability across various domains [

30]. Nevertheless, evaluating features remains computationally intensive, especially when dealing with high-dimensional datasets.

7.2. Limitations and Open Questions

Our investigation highlights several limitations inherent in the studied methodologies, indicating directions for future research. Although advanced imputation methods like MissForest and GANs demonstrate robust performance, their efficacy is contingent upon certain assumptions regarding missing data mechanisms (e.g., MCAR, MAR), which may not be applicable in practical scenarios, potentially introducing biases [

7]. Future inquiries should aim to develop adaptive models capable of handling missing not at random (MNAR) situations, possibly through the integration with auxiliary data or synthetic data generation.

Exploratory techniques such as PCA and clustering algorithms often necessitate domain-specific expertise for optimal parameter calibration, including decisions on dimensionality thresholds and cluster numbers. Inadequate configurations can lead to distorted outcomes, underscoring the necessity for automated systems that minimize reliance on specialist knowledge [

22].

In terms of feature selection, embedded methods—despite their efficiency—sometimes fail to capture complex interactions crucial for modeling intricate systems. Incorporating mechanisms for interaction detection or developing hybrid frameworks that amalgamate diverse selection methodologies could address this limitation, enhancing the overall efficacy of feature selection processes.

7.3. Broader Implications for Big Data Analytics

The adoption of these data cleaning techniques holds transformative potential for analytical workflows within big data ecosystems. By ensuring meticulous preprocessing of datasets, organizations can derive more precise insights, thereby facilitating informed decision-making across various sectors including healthcare, finance, and marketing [

8]. This capability amplifies the extraction of actionable intelligence from expansive data repositories.

Advanced exploratory tools empower stakeholders to customize cleaning protocols and model designs in alignment with specific analytical objectives, ensuring coherence between preprocessing phases and subsequent tasks. Concurrently, robust imputation strategies mitigate risks associated with data degradation, preserving the integrity of inferences derived from incomplete datasets [

28].

Efficient feature selection further refines big data analytics by decreasing dimensionality, resulting in swifter model training and more interpretable outcomes—elements crucial in regulated sectors such as finance and healthcare where transparency is paramount [

22]. However, the scalability of these advantages hinges on resource availability, necessitating judicious assessment of infrastructure prerequisites.

As big data systems expand, striking a balance between analytical precision and operational efficiency grows increasingly intricate. Emerging paradigms like multi-cloud architectures and edge computing present opportunities to manage computational demands more adeptly, though their successful deployment requires thorough evaluation of system capabilities and processing constraints.

In summation, the integration of advanced data cleaning methodologies is central to contemporary big data analytics, enhancing both data quality and analytical reliability. Future research should concentrate on devising adaptive, scalable solutions that align with the dynamic progression of big data environments.

References

- Carlo Batini and Monica Scannapieco. Data and Information Quality: Dimensions, Principles and Techniques, 2016.

- Erhard Rahm and Hong Hai, Do. Data cleaning: Problems and current approaches. Bull. IEEE Comput. Soc. Tech. Comm. Data Eng. 2000, 23, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Charu, C. Aggarwal. Data Mining: The Textbook. Springer, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, L. Villars, Carl W. Olofson, and Matthew Eastwood. Big data: What it is and why you should care. White Paper, IDC 2011, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ian Jolliffe. Principal Component Analysis. Springer, 2011.

- Laurens Van der Maaten and Geoffrey Hinton. Visualizing data using t-sne. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2008, 9, 2579–2605. [Google Scholar]

- Donald, B. Rubin. Inference and missing data. Biometrika 1976, 63, 581–592. [Google Scholar]

- Olga Troyanskaya, Michael Cantor, Gavin Sherlock, Pat Brown, Trevor Hastie, Robert Tibshirani, David Botstein, and Russ B. Altman. Missing value estimation methods for dna microarrays. Bioinformatics 2001, 17, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stef Van Buuren and Karin Groothuis-Oudshoorn. Mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in r. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 45, 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Girish Chandrashekar and Ferat Sahin. A survey on feature selection methods. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2014, 40, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert Tibshirani. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodological) 1996, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, E. Hoerl and Robert W. Kennard. Ridge regression: Biased estimation for nonorthogonal problems. Technometrics 1970, 12, 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Leo Breiman. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerome, H. Friedman. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Ian Goodfellow, Yoshua Bengio, and Aaron Courville. Deep Learning. MIT Press, 2016.

- Geoffrey, E. Hinton and Ruslan R. Salakhutdinov. Reducing the dimensionality of data with neural networks. Science 2006, 313, 504–507. [Google Scholar]

- Arimondo Scrivano. Adversarial attacks and mitigation strategies on wifi networks. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Arimondo Scrivano. Fraud detection pipeline using machine learning: Methods, applications, and future directions. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Arimondo Scrivano. A comparative study of classical and post-quantum cryptographic algorithms in the era of quantum computing. Preprint. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Arimondo Scrivano. Advances in indoor positioning systems: Integrating iot and machine learning for enhanced accuracy. Preprint. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Arimondo Scrivano. Cloud service architectures for internet of things (iot) integration: Analyzing efficient cloud computing models and architectures tailored for iot environments. Preprint. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Anil, K. Jain. Data clustering: 50 years beyond k-means. In Pattern Recognition Letters, volume 31, pages 651–666, 2010.

- Joshua, B. Tenenbaum, Vin de Silva, and John C. Langford. A global geometric framework for nonlinear dimensionality reduction. Science 2000, 290, 2319–2323. [Google Scholar]

- Pieter Adriaans and Dolf Zantinge. Data Mining. Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc. 1996.

- Yehuda Koren, Robert Bell, and Chris Volinsky. Matrix factorization techniques for recommender systems. Computer 2009, 42, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel J., J. Stekhoven and Peter Bühlmann. Missforest—non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Jinsung Yoon, James Jordon, and Mihaela Schaar. Gain: Missing data imputation using generative adversarial nets. arXiv, 2018; arXiv:1806.02920.

- Isabelle Guyon and André Elisseeff. An introduction to variable and feature selection. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 1157–1182. [Google Scholar]

- Isabelle Guyon, Jason Weston, Stephen Barnhill, and Vladimir Vapnik. Gene selection for cancer classification using support vector machines. Mach. Learn. 2002, 46, 389–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michał Kursa and Witold Rudnicki. Feature selection with the boruta package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 36, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).