Submitted:

16 July 2025

Posted:

17 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

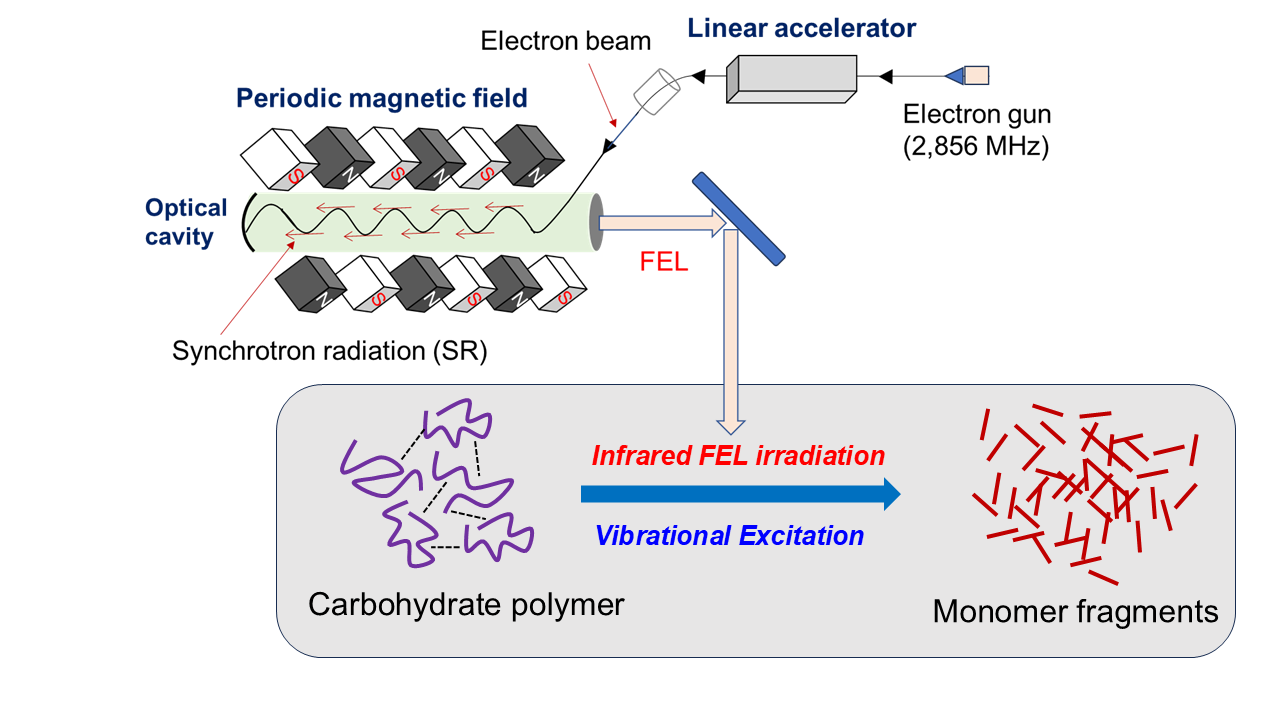

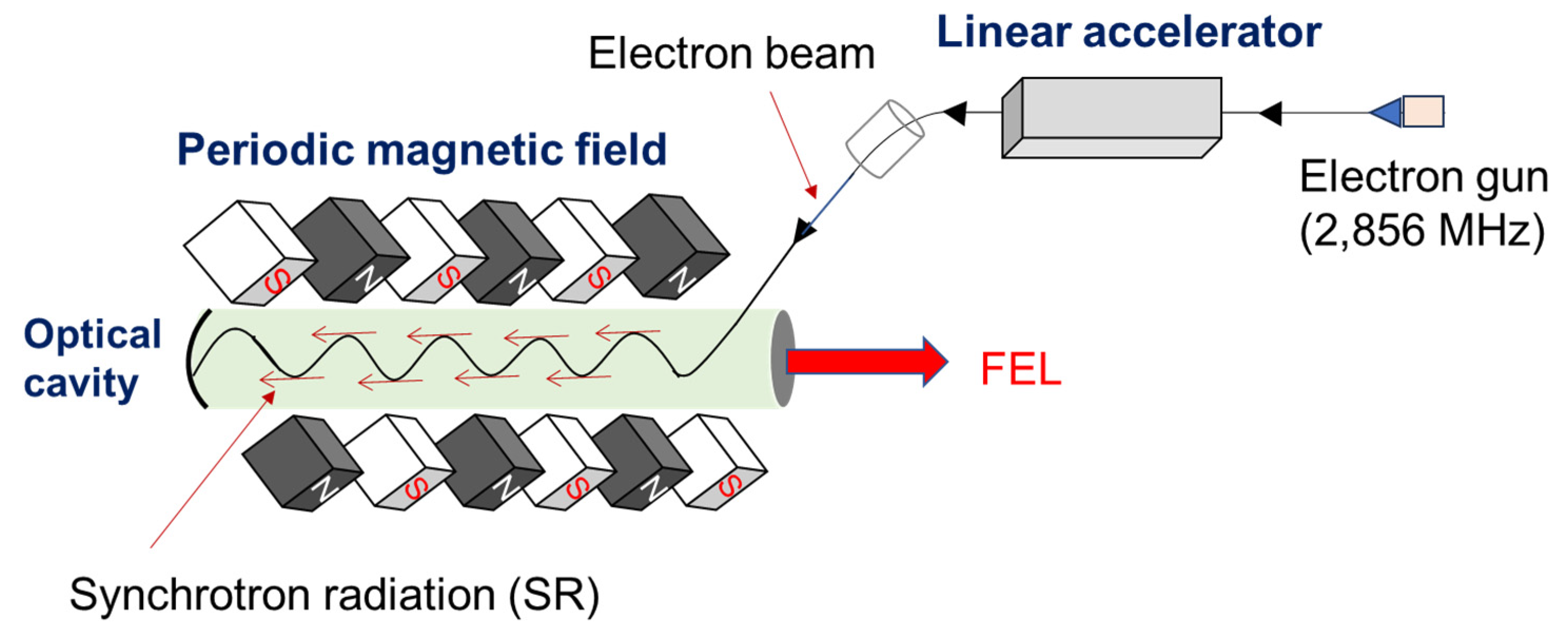

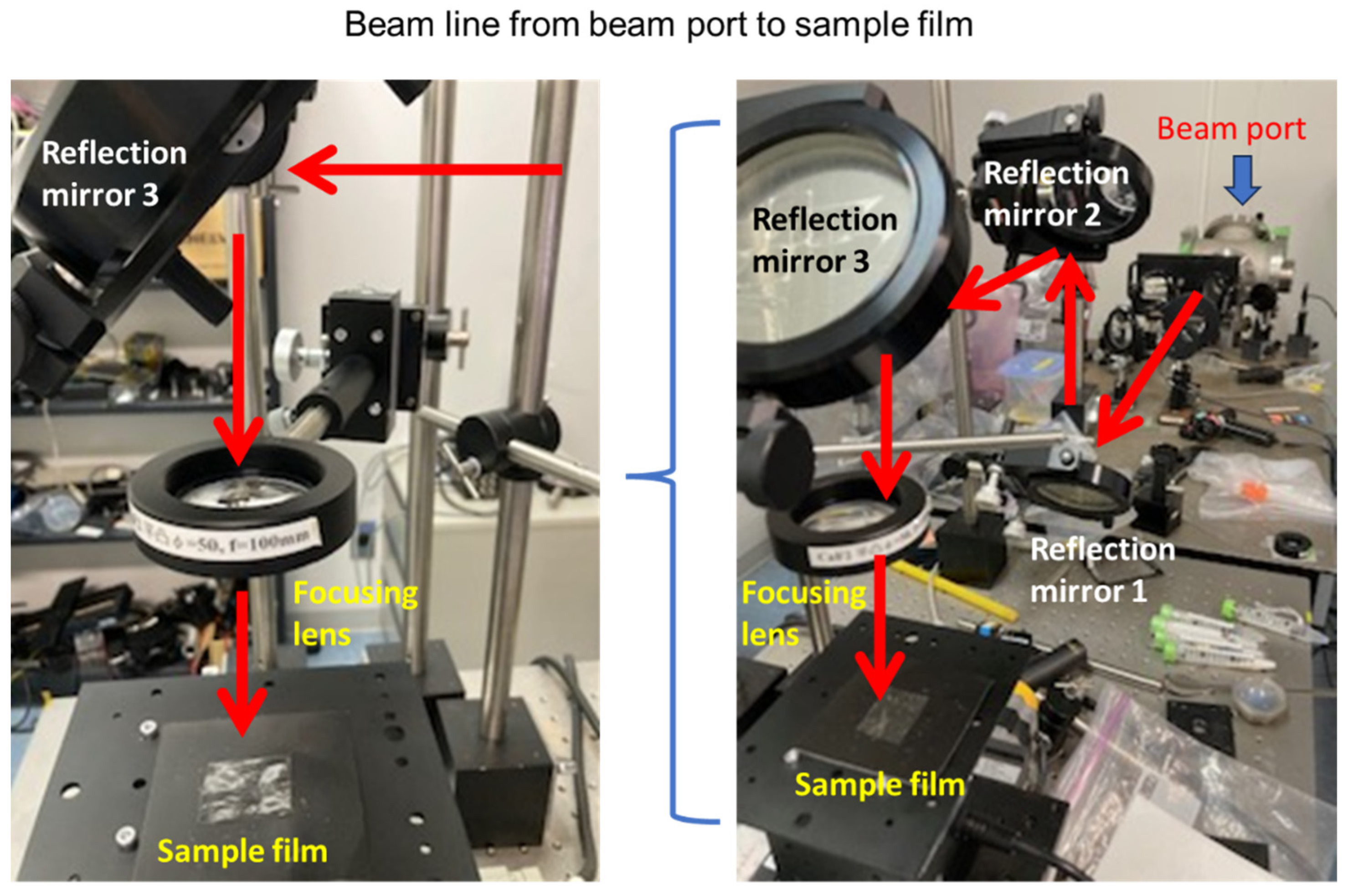

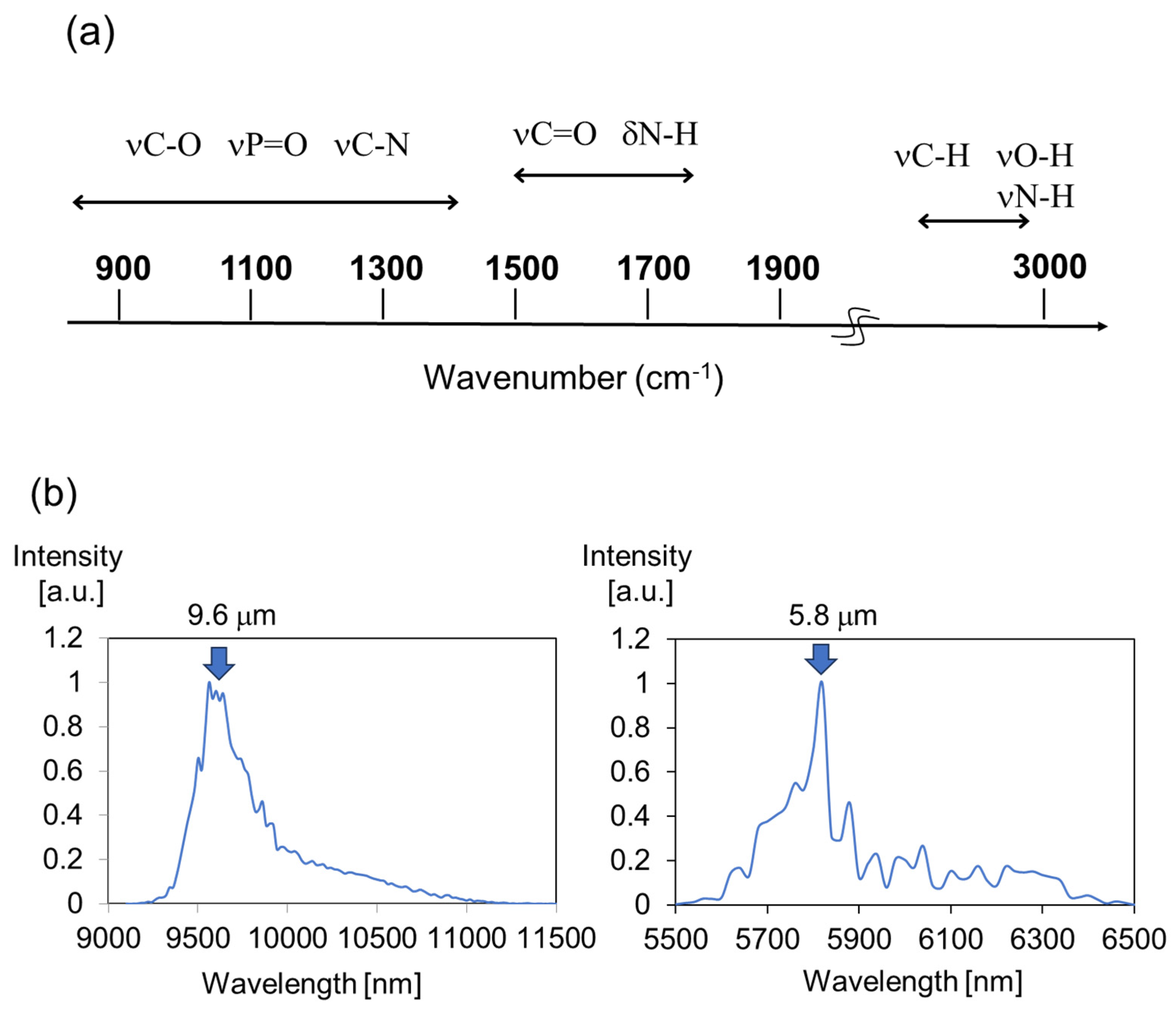

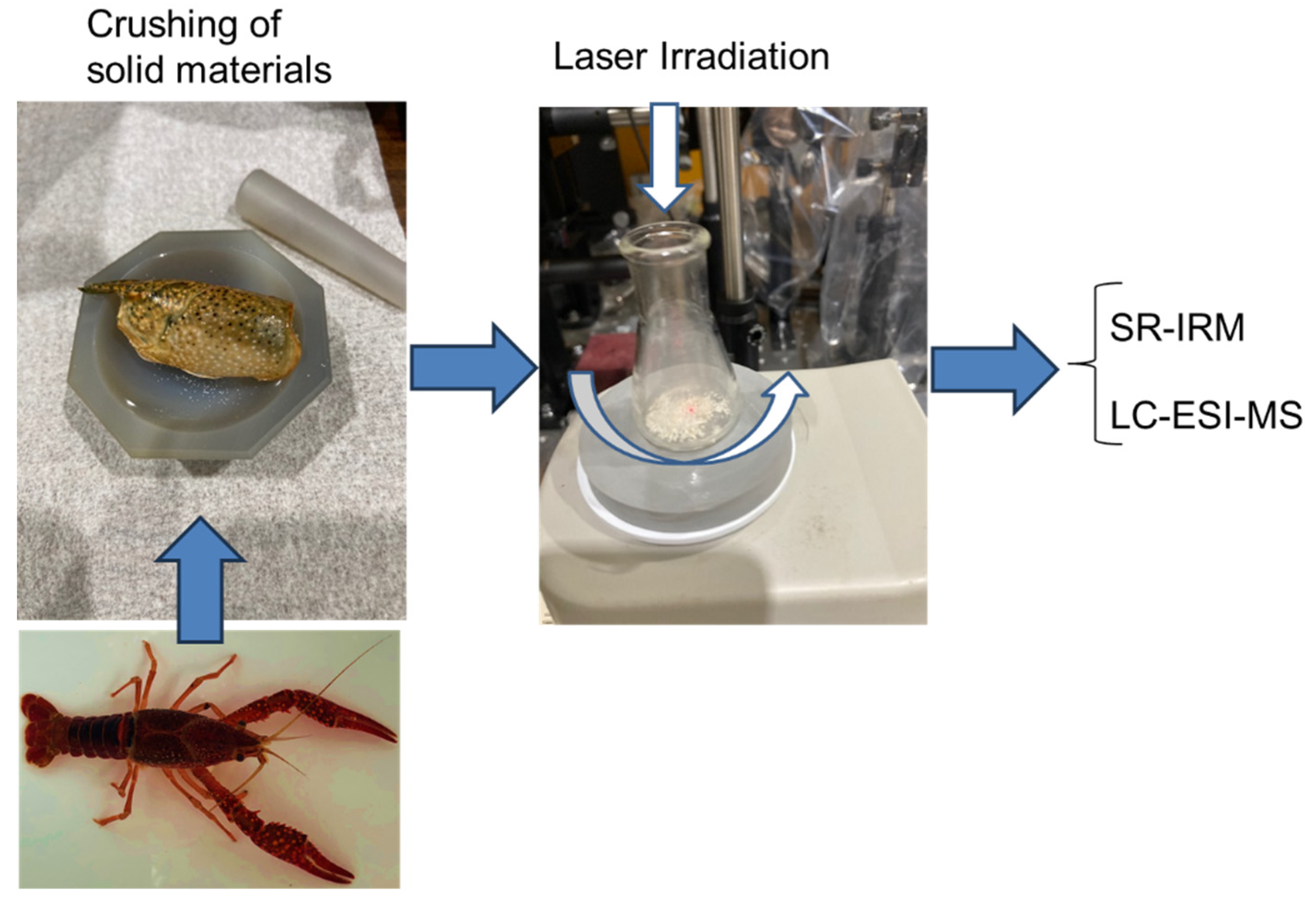

2. Feature of Method

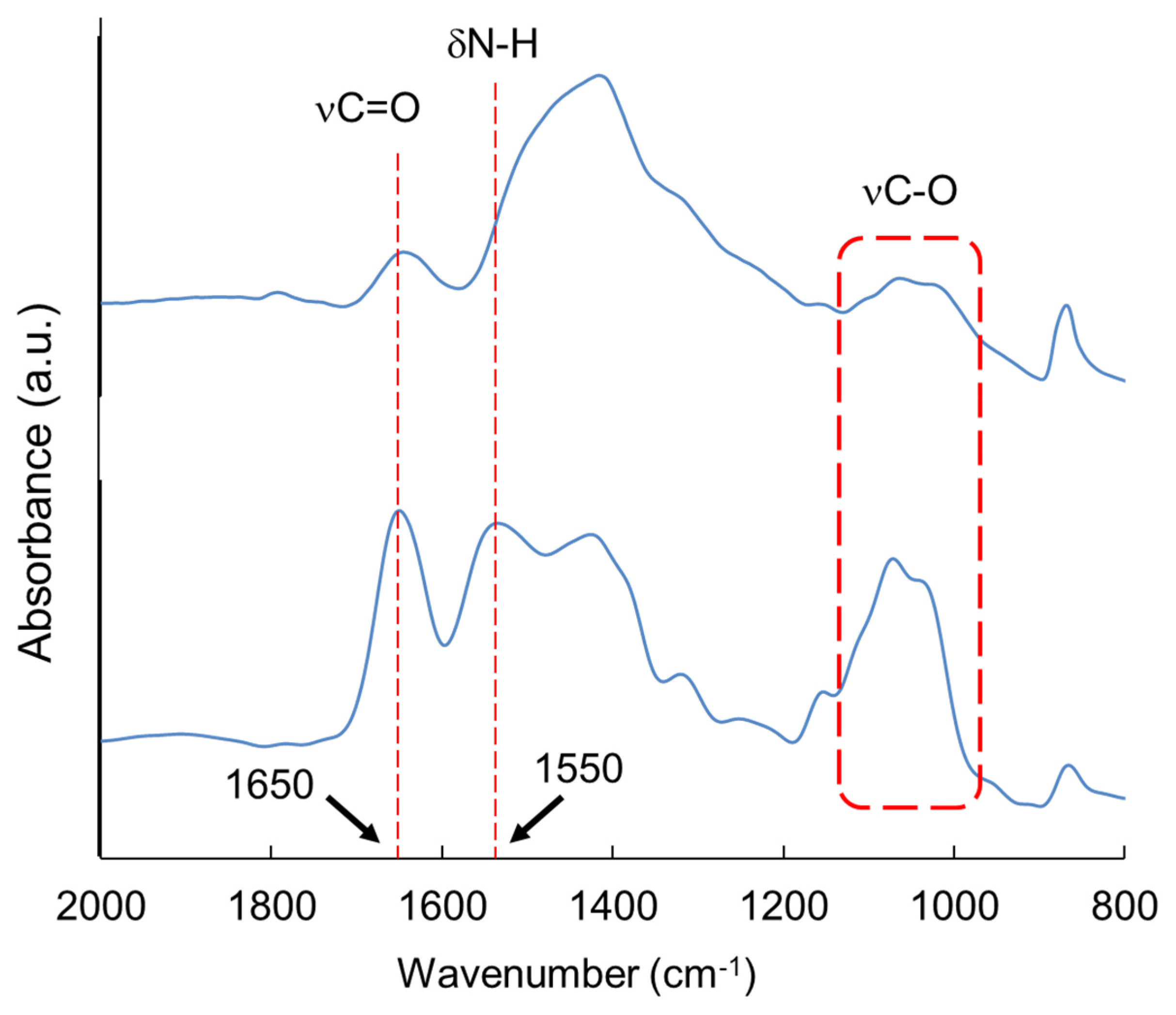

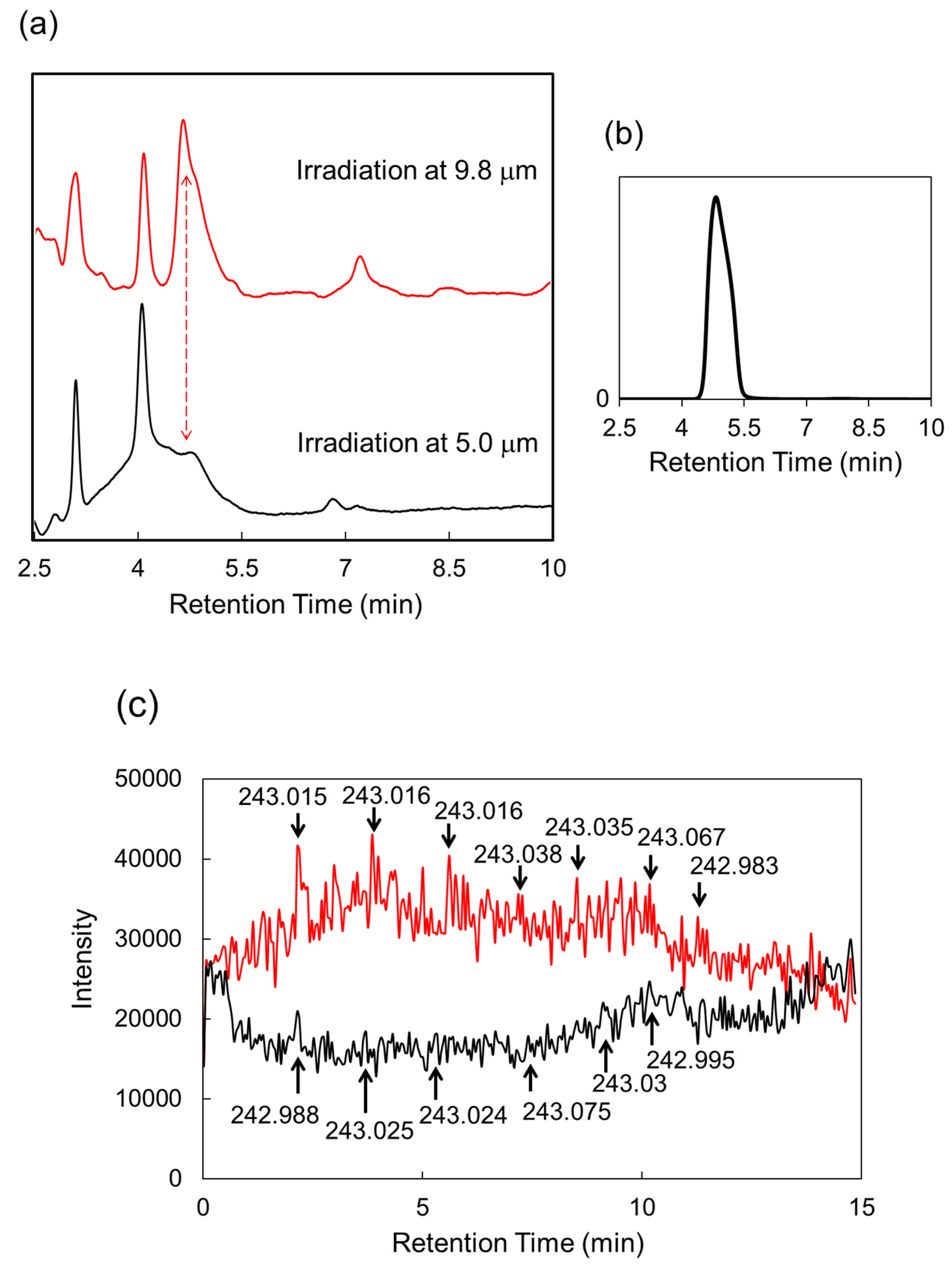

3. Analysis of Chitin

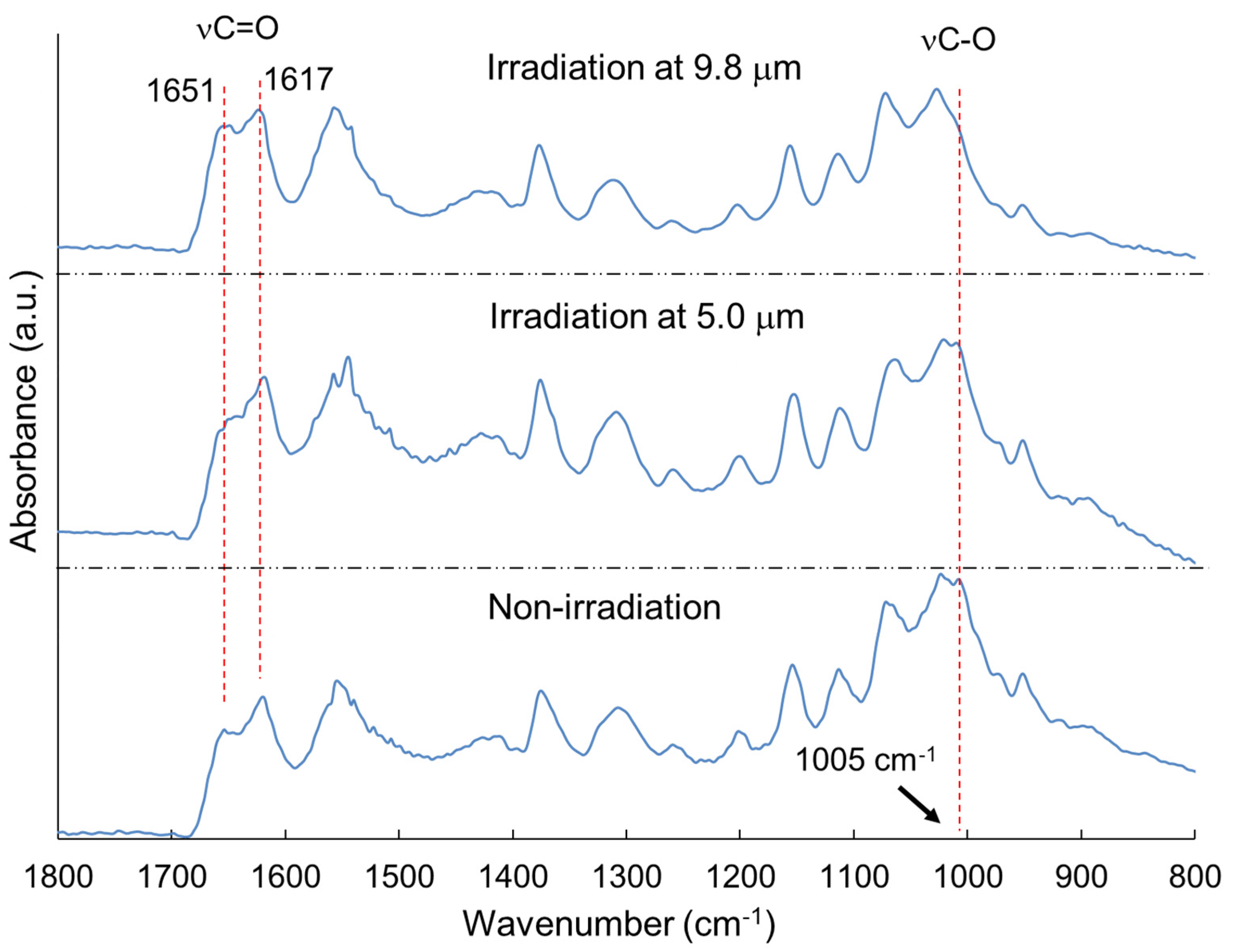

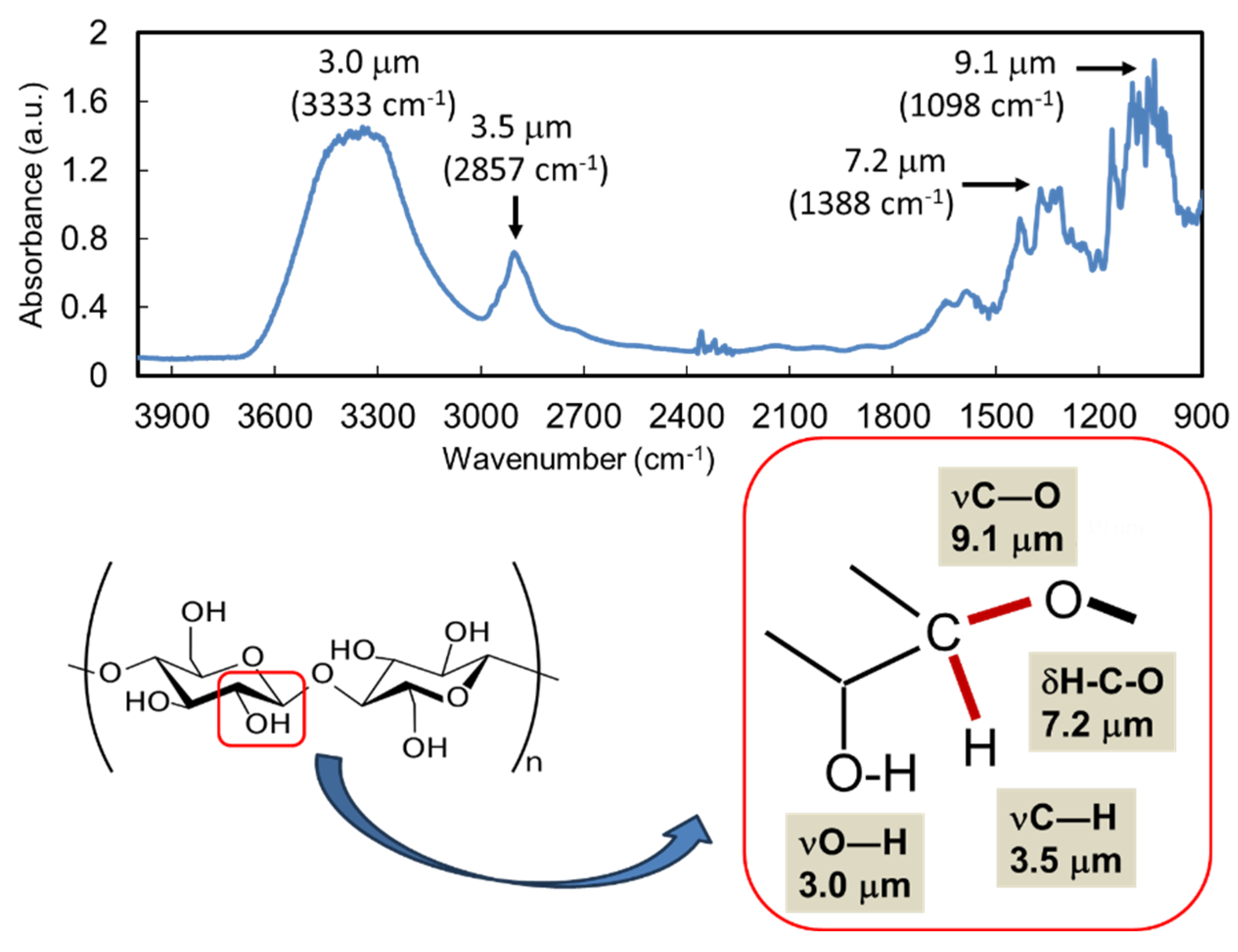

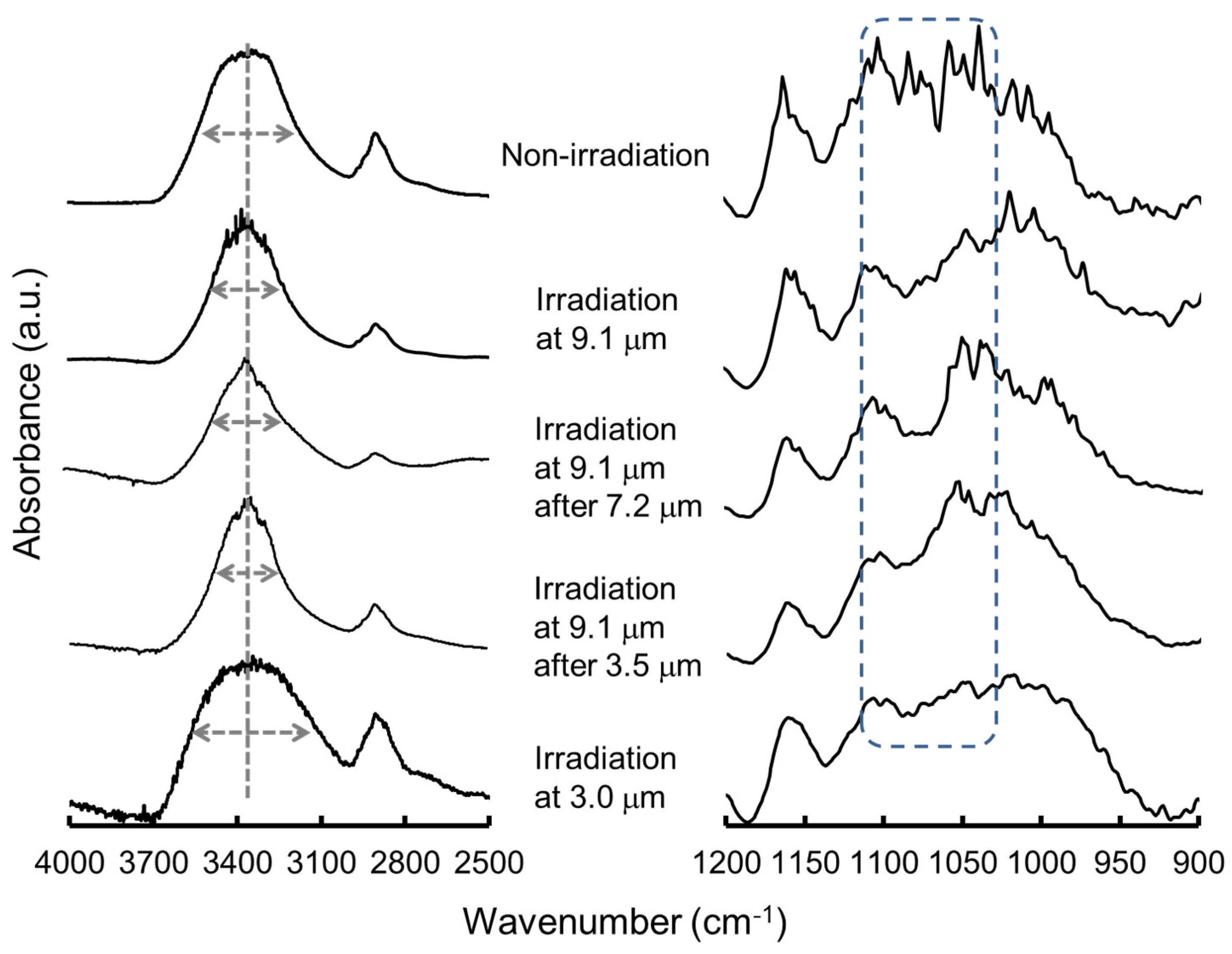

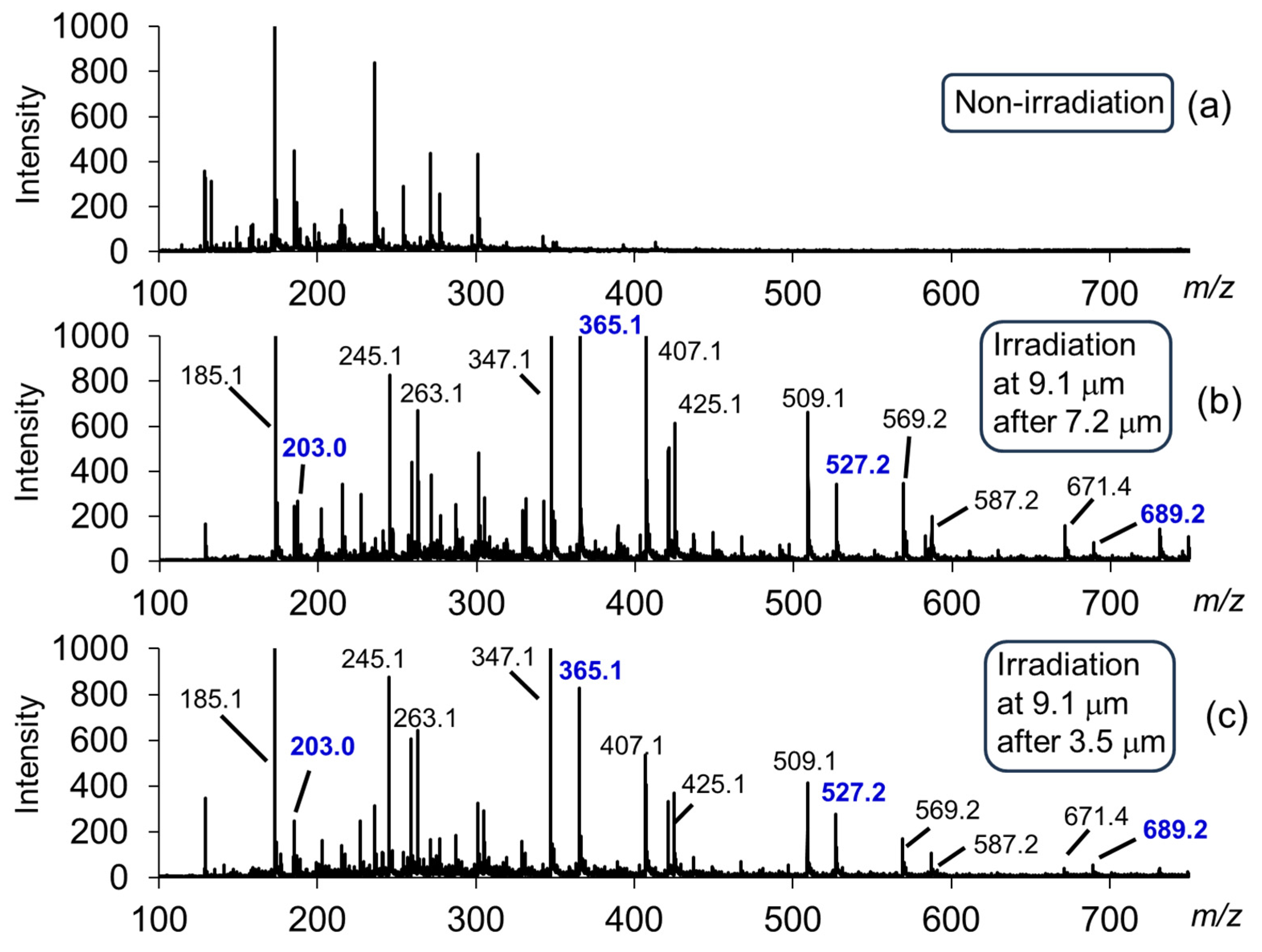

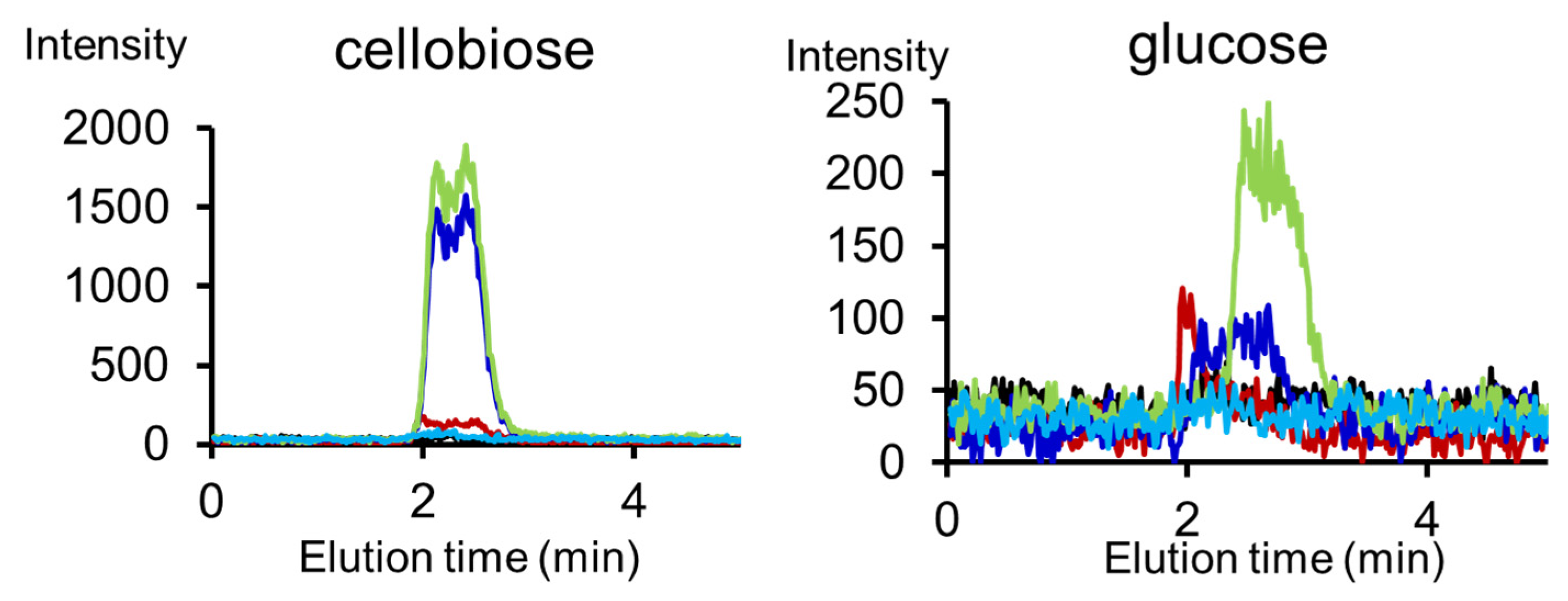

4. Analysis of Cellulose

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FEL | Free electron laser |

| IRMPD | Infrared multi photon dissociation |

| SR-IRM | Synchrotron radiation infrared microscopy |

| ESI-MS | Electron spray ionization mass spectrometry |

| SR | Synchrotron radiation |

| VE | Vibrational excitation |

| EB | Electron beam |

| RF | Radiofrequency |

| HPLC | High performance liquid chromatography |

| CE | Capillary electrophoresis |

| NIR | Near infrared |

| AFM | Atomic force microscopy |

| SEC | Size-exclusion chromatography |

| MALLS | Multiple-angle laser light scattering |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| HPAEC-PAD | High-performance anion exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometry detection |

| MALDI-MSI | Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-mass spectrometry imaging |

| PAS | Photoacoustic spectroscopy |

| TG | Thermogravimetric |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| SEM | Scanning-electron microscope |

| MS | Mass spectrometry |

| ATR | Attenuated total reflectance |

| LC-MS | Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry |

| TLC | Thin-layer chromatography |

References

- Yu H, Chen X. Carbohydrate post-glycosylational modifications. Org Biomol Chem. 2007 Mar 21;5(6):865-72. [CrossRef]

- Su L, Hendrikse SIS, Meijer EW. Supramolecular glycopolymers: How carbohydrates matter in structure, dynamics, and function. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2022 Aug;69:102171. [CrossRef]

- Wisnovsky S, Bertozzi CR. Reading the glyco-code: New approaches to studying protein-carbohydrate interactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2022 Aug;75:102395. [CrossRef]

- Voiniciuc C, Pauly M, Usadel B. Monitoring Polysaccharide Dynamics in the Plant Cell Wall. Plant Physiol. 2018 Apr;176(4):2590-2600. [CrossRef]

- Sandhu AP, Randhawa GS, Dhugga KS. Plant cell wall matrix polysaccharide biosynthesis. Mol Plant. 2009 Sep;2(5):840-50. [CrossRef]

- Bayer, IS. Hyaluronic Acid and Controlled Release: A Review. Molecules. 2020 Jun 6;25(11):2649. [CrossRef]

- El Masri R, Crétinon Y, Gout E, Vivès RR. HS and Inflammation: A Potential Playground for the Sulfs? Front Immunol. 2020 Apr 3;11:570. [CrossRef]

- Muthukrishnan S, Mun S, Noh MY, Geisbrecht ER, Arakane Y. Insect Cuticular Chitin Contributes to Form and Function. Curr Pharm Des. 2020;26(29):3530-3545. [CrossRef]

- Qiu S, Zhou S, Tan Y, Feng J, Bai Y, He J, Cao H, Che Q, Guo J, Su Z. Biodegradation and Prospect of Polysaccharide from Crustaceans. Mar Drugs. 2022 May 2;20(5):310. [CrossRef]

- Koirala P, Bhandari Y, Khadka A, Kumar SR, Nirmal NP. Nanochitosan from crustacean and mollusk byproduct: Extraction, characterization, and applications in the food industry. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024 Mar;262(Pt 1):130008. [CrossRef]

- Wear MP, Jacobs E, Wang S, McConnell SA, Bowen A, Strother C, Cordero RJB, Crawford CJ, Casadevall A. Cryptococcus neoformans capsule regrowth experiments reveal dynamics of enlargement and architecture. J Biol Chem. 2022 Apr;298(4):101769. [CrossRef]

- Gow NAR, Latge JP, Munro CA. The Fungal Cell Wall: Structure, Biosynthesis, and Function. Microbiol Spectr. 2017 May;5(3):10.1128/microbiolspec.funk-0035-2016. [CrossRef]

- Roth C, Weizenmann N, Bexten N, Saenger W, Zimmermann W, Maier T, Sträter N. Amylose recognition and ring-size determination of amylomaltase. Sci Adv. 2017 Jan 13;3(1):e1601386. [CrossRef]

- Myers AM, Morell MK, James MG, Ball SG. Recent progress toward understanding biosynthesis of the amylopectin crystal. Plant Physiol. 2000 Apr;122(4):989-97. [CrossRef]

- Brust H, Orzechowski S, Fettke J. Starch and Glycogen Analyses: Methods and Techniques. Biomolecules. 2020 Jul 9;10(7):1020. [CrossRef]

- Aditya T, Allain JP, Jaramillo C, Restrepo AM. Surface Modification of Bacterial Cellulose for Biomedical Applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Jan 6;23(2):610. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, UP. Analysis of Cellulose and Lignocellulose Materials by Raman Spectroscopy: A Review of the Current Status. Molecules. 2019 Apr 27;24(9):1659. [CrossRef]

- Chen W, Cao P, Liu Y, Yu A, Wang D, Chen L, Sundarraj R, Yuchi Z, Gong Y, Merzendorfer H, Yang Q. Structural basis for directional chitin biosynthesis. Nature. 2022 Oct;610(7931):402-408. [CrossRef]

- Anand S, Azimi B, Lucena M, Ricci C, Candito M, Zavagna L, Astolfi L, Coltelli MB, Lazzeri A, Berrettini S, Moroni L, Danti S, Mota C. Chitin nanofibrils modulate mechanical response in tympanic membrane replacements. Carbohydr Polym. 2023 Jun 15;310:120732. [CrossRef]

- Rubinson KA, Chen Y, Cress BF, Zhang F, Linhardt RJ. Heparin’s solution structure determined by small-angle neutron scattering. Biopolymers. 2016 Dec;105(12):905-13. [CrossRef]

- Qiao M, Lin L, Xia K, Li J, Zhang X, Linhardt RJ. Recent advances in biotechnology for heparin and heparan sulfate analysis. Talanta. 2020 Nov 1;219:121270. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Zhao S, Wang J, Chen Y, Li H, Li JP, Kan Y, Zhang T. Methods for determining the structure and physicochemical properties of hyaluronic acid and its derivatives: A review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024 Dec;282(Pt 6):137603. [CrossRef]

- Marcotti S, Maki K, Reilly GC, Lacroix D, Adachi T. Hyaluronic acid selective anchoring to the cytoskeleton: An atomic force microscopy study. PLoS One. 2018 Oct 25;13(10):e0206056. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Xu X, Zhang Q, Zhang D, Xie X, Zhou H, Wu Z, Liu R, Pang J. Review of Konjac Glucomannan Structure, Properties, Gelation Mechanism, and Application in Medical Biology. Polymers (Basel). 2023 Apr 12;15(8):1852. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Fu A, Hui H, Jia F, Wang H, Zhao T, Wei J, Zhang P, Lang W, Li K, Hu X. Structure characterization and preliminary immune activity of a glucomannan purified from Allii Tuberosi Semen. Carbohydr Res. 2025 Mar;549:109375. [CrossRef]

- Du B, Meenu M, Liu H, Xu B. A Concise Review on the Molecular Structure and Function Relationship of β-Glucan. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Aug 18;20(16):4032. [CrossRef]

- Pourtalebi Jahromi L, Rothammer M, Fuhrmann G. Polysaccharide hydrogel platforms as suitable carriers of liposomes and extracellular vesicles for dermal applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2023 Sep;200:115028. [CrossRef]

- Yonggang Wang1,2 •Yanjun Jing1,2 • Feifan Leng1,2 • Shiwei Wang1,2 •Fan Wang1,2 • Yan Zhuang1,2 • Xiaofeng Liu1,2 • Xiaoli Wang3 • Xueqing Ma4, Establishment and Application of a Method for Rapid Determination of Total Sugar Content Based on Colorimetric Microplate. Sugar Tech (July-Aug 2017) 19(4):424–431.

- ROE, JH. The determination of sugar in blood and spinal fluid with anthrone reagent. J Biol Chem. 1955 Jan;212(1):335-43.

- Omondi S, Kosgei J, Agumba S, Polo B, Yalla N, Moshi V, Abong’o B, Ombok M, McDermott DP, Entwistle J, Samuels AM, Ter Kuile FO, Gimnig JE, Ochomo E. Natural sugar feeding rates of Anopheles mosquitoes collected by different methods in western Kenya. Sci Rep. 2022 Nov 29;12(1):20596. [CrossRef]

- Clarke AJ, Cox PM, Shepherd AM. The chemical composition of the egg shells of the potato cyst-nematode, Heterodera rostochiensis Woll. Biochem J. 1967 Sep;104(3):1056-60. [CrossRef]

- BOWNESS, JM. Application of the carbazole reaction to the estimation of glucuronic acid and flucose in some acidic polysaccharides and in urine. Biochem J. 1957 Oct;67(2):295-300. [CrossRef]

- Felz S, Vermeulen P, van Loosdrecht MCM, Lin YM. Chemical characterization methods for the analysis of structural extracellular polymeric substances. Water Res. 2019 Jun 15;157:201-208. [CrossRef]

- Wang HC, Lee AR. Recent developments in blood glucose sensors. J Food Drug Anal. 2015 Jun;23(2):191-200. [CrossRef]

- Ge J, Mao W, Wang X, Zhang M, Liu S. The Fluorescent Detection of Glucose and Lactic Acid Based on Fluorescent Iron Nanoclusters. Sensors (Basel). 2024 May 27;24(11):3447. [CrossRef]

- Hase S, Hara S, Matsushima Y. Tagging of sugars with a fluorescent compound, 2-aminopyridine. J Biochem. 1979 Jan;85(1):217-20. [CrossRef]

- Rothenberg BE, Hayes BK, Toomre D, Manzi AE, Varki A. Biotinylated diaminopyridine: an approach to tagging oligosaccharides and exploring their biology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 Dec 15;90(24):11939-43. [CrossRef]

- Volpi N, Maccari F, Linhardt RJ. Capillary electrophoresis of complex natural polysaccharides. Electrophoresis. 2008 Aug;29(15):3095-106. [CrossRef]

- Szigeti M, Meszaros-Matwiejuk A, Molnar-Gabor D, Guttman A. Rapid capillary gel electrophoresis analysis of human milk oligosaccharides for food additive manufacturing in-process control. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2021 Mar;413(6):1595-1603. [CrossRef]

- Yuling Wang, Xingqi Ou, Qais Ali Al-Maqtari, Hong-Ju He, Norzila Othman. Evaluation of amylose content: Structural and functional properties, analytical techniques, and future prospects. Food Chemistry: X 24 (2024) 101830. [CrossRef]

- Rachelle M. Ward, Qunyu Gao, Hank de Bruyn, Robert G. Gilbert, and Melissa A. Fitzgerald, Improved Methods for the Structural Analysis of the Amylose-Rich Fraction from Rice Flour. Biomacromolecules 2006, 7, 866–876. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. P. Mua and D. S. Jackson, Relationships between Functional Attributes and Molecular Structures of Amylose and Amylopectin Fractions from Corn Starch. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 3848−3854.

- Jia X, Xu J, Cui Y, Ben D, Wu C, Zhang J, Sun M, Liu S, Zhu T, Liu J, Lin K, Zheng M. Effect of Modification by β-Amylase and α-Glucosidase on the Structural and Physicochemical Properties of Maize Starch. Foods. 2024 Nov 24;13(23):3763. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Xu, J.; Guo, D.; Long, C.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Huang, H.; Wen, P.; He, H.; He, X. Research on the Relationship between the Amylopectin Structure and the Physicochemical Properties of Starch Extracted from Glutinous Rice. Foods 2023, 12, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conroy, L.R. , Clarke, H.A., Allison, D.B. et al. Spatial metabolomics reveals glycogen as an actionable target for pulmonary fibrosis. Nat Commun 14, 2759 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Csóka, L. , Csoka, W., Tirronen, E. et al. Integrated analysis of cellulose structure and properties using solid-state low-field H-NMR and photoacoustic spectroscopy. Sci Rep 15, 2195 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Díez, D.; Urueña, A.; Piñero, R.; Barrio, A.; Tamminen, T. Determination of Hemicellulose, Cellulose, and Lignin Content in Different Types of Biomasses by Thermogravimetric Analysis and Pseudocomponent Kinetic Model (TGA-PKM Method). Processes 2020, 8, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triunfo, M. , Tafi, E., Guarnieri, A. et al. Characterization of chitin and chitosan derived from Hermetia illucens, a further step in a circular economy process. Sci Rep 12, 6613 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Jolanta Kumirska, Małgorzata Czerwicka, Zbigniew Kaczyński, Anna Bychowska, Krzysztof Brzozowski, Jorg Thöming and Piotr Stepnowski. Application of Spectroscopic Methods for Structural Analysis of Chitin and Chitosan. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 1567–1636. [CrossRef]

- Pierre Mourier, Pascal Anger, Céline Martinez, Fréderic Herman, Christian Viskov. Quantitative compositional analysis of heparin using exhaustive heparinase digestion and strong anion exchange chromatography. Analytical Chemistry Research 3 (2015) 46–53. [CrossRef]

- Anthony, J. Anthony J. Devlin, Courtney J. Mycroft-West, Jeremy E. Turnbull, Marcelo Andrade de Lima, Marco Guerrini, Edwin A. Yates, Mark A. Skidmore. Analysis of Heparin Samples by Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy in the Solid State. ACS Cent. Sci. 2023, 9(3), 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Hernández, L.A.; Camacho-Ruíz, R.M.; Arriola-Guevara, E.; Padilla-Camberos, E.; Kirchmayr, M.R.; Corona-González, R.I.; Guatemala-Morales, G.M. Validation of an Analytical Method for the Simultaneous Determination of Hyaluronic Acid Concentration and Molecular Weight by Size-Exclusion Chromatography. Molecules 2021, 26, 5360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felipe Rivas, Osama K. Zahid, Heidi L. Reesink, Bridgette T. Peal, Alan J. Nixon, Paul L. DeAngelis, Aleksander Skardal, Elaheh Rahbar1 & Adam R. Hall. Label-free analysis of physiological hyaluronan size distribution with a solid-state nanopore sensor. NATURE COMMUNICATIONS (2018) 9:1037. [CrossRef]

- Omar Ishrud, Muhammad Zahid, Viqar Uddin Ahmad, and Yuanjiang Pan. Isolation and Structure Analysis of a Glucomannan from the Seeds of Libyan Dates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 3772–3774. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace Lu, Cassandra L. Crihfield, Srikanth Gattu, Lindsay M. Veltri, and Lisa A. Holland. Capillary Electrophoresis Separations of Glycans. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 7867–7885. [CrossRef]

- Tang Z, Huang G. Extraction, structure, and activity of polysaccharide from Radix astragali. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022 Jun;150:113015. [CrossRef]

- Karnaouri A, Chorozian K, Zouraris D, Karantonis A, Topakas E, Rova U, Christakopoulos P. Lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases as powerful tools in enzymatically assisted preparation of nano-scaled cellulose from lignocellulose: A review. Bioresour Technol. 2022 Feb; 345:126491. [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, T. , Nagase A., Hayakawa K., Teshima F., Tanaka K., Zen H., Shishikura F., Sei N., Sakai T., Hayakawa Y. Infrared Free-Electron Laser: A Versatile Molecular Cutter for Analyzing Solid-State Biomacromolecules. ACS Omega 2025 Apr 2;10(14):13860-13867. [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, T.; Sakai, T.; Zen, H.; Sumitomo, Y.; Nogami, K.; Hayakawa, K.; Yaji, T.; Ohta, T.; Tsukiyama, K.; Hayakawa, Y. Cellulose Degradation by Infrared Free Electron Laser. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 9064−9068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, T.; Zen, H.; Sakai, T.; Sumitomo, Y.; Nogami, K.; Hayakawa, K.; Yaji, T.; Ohta, T.; Nagata, T.; Hayakawa, Y. Degradation of Lignin by Infrared Free Electron Laser. Polymers 2022, 14, 2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helburn R, Nolan K. Characterizing biological macromolecules with attenuated total reflectance-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy provides hands-on spectroscopy experiences for undergraduates. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2022 Jul;50(4):381-392. [CrossRef]

- Johnson JB, Walsh KB, Naiker M, Ameer K. The Use of Infrared Spectroscopy for the Quantification of Bioactive Compounds in Food: A Review. Molecules. 2023 Apr 4;28(7):3215. [CrossRef]

- Soulby AJ, Heal JW, Barrow MP, Roemer RA, O’Connor PB. Does deamidation cause protein unfolding? A top-down tandem mass spectrometry study. Protein Sci. 2015 May;24(5):850-60. [CrossRef]

- Smith SI, Guziec FS Jr, Guziec L, Brodbelt JS. Interactions of sulfur-containing acridine ligands with DNA by ESI-MS. Analyst. 2009 Oct;134(10):2058-66. [CrossRef]

- Theisen A, Wootton CA, Haris A, Morgan TE, Lam YPY, Barrow MP, O’Connor PB. Enhancing Biomolecule Analysis and 2DMS Experiments by Implementation of (Activated Ion) 193 nm UVPD on a FT-ICR Mass Spectrometer. Anal Chem. 2022 Nov 15;94(45):15631-15638. [CrossRef]

- J.J. Valle, J.R. Eyler, J. Oomens, D.T. Moore, A.F.G. van der Meer, G. von Helden, G. Meijer, C.L. Hendrickson, A.G. Marshall, G.T. Blakney, Free electron laser-Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry facility for obtaining infrared multiphoton dissociation spectra of gaseous ions, Rev. Sci. Instrum. 76 (2) (2005) 023103. [CrossRef]

- Zavalin A, Hachey DL, Sundaramoorthy M, Banerjee S, Morgan S, Feldman L, Tolk N, Piston DW. B Kinetics of a collagen-like polypeptide fragmentation after mid-IR free-electron laser ablation. Biophys. J. 2008 Aug;95(3):1371-81. [CrossRef]

- P G O’Shea, H P Freund. Free-electron lasers. Status and applications. Science 2001 Jun 8;292(5523):1853-8. [CrossRef]

- F. Glotin, R. Chaput, D. Jaroszynski, R. Prazeres, and J.-M. Ortega. Infrared subpicosecond laser pulses with a free-electron laser. Phys. Rev. Lett. 71, 2587 (1993). [CrossRef]

- Zen, H.; Suphakul, S.; Kii, T.; Masuda, K.; Ohgaki, H. Present status and perspectives of long wavelength free electron lasers at Kyoto University. Phys. Procedia 2016, 84, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zen, H.; Hajima, R.; Ohgaki, H. Full characterization of superradiant pulses generated from a free-electron laser oscillator. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayakawa, Y.; Sato, I.; Hayakawa, K.; Tanaka, T. First lasing of LEBRA FEL at Nihon University at a wavelength of 1. 5 μm. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 2002, 483, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, K.; Hayakawa, K.; Hayakawa, Y.; Inagaki, M.; Nogami, K.; Sakai, T.; Tanaka, T.; Zen, H. Pulse Structure Measurement of Near-Infrared FEL in Burst-Mode Operation of LEBRA Linac. In Proceedings of FEL2012; Nara, Japan, 2012, p 472.

- Sakai, T.; Hayakawa, K.; Tanaka, T.; Hayakawa, Y.; Nogami, K.; Sei, N. Evaluation of Bunch Length by Measuring Coherent Synchrotron Radiation with a Narrow-Band Detector at LEBRA. Condens. Matter 2020, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Kawasaki, H. Zen, K. Ozaki, H. Yamada, K. Wakamatsu and S. Ito. Application of mid-infrared free-electron laser for structural analysis of biological materials. J. Synchrotron Rad. (2021). 28, 28-35. [CrossRef]

- Kakoulli, I. , Prikhodko, S.V., Fischer, C., Cilluffo, M., Uribe, M., Bechtel, H.A., Fakra, S.C. and Marcus, M.A. (2013) Distribution and Chemical Speciation of Arsenic in Ancient Human Hair Using Synchrotron Radiation. Analytical Chemistry, 86, 521-526. [CrossRef]

- Ling, S., Qi, Z., Knight, D.P., Huang, Y., Huang, L., Zhou, H., Shao, Z. and Chen, X. (2013) Insight into the Structure of Single Antheraea pernyi Silkworm Fibers Using Synchrotron FTIR Microspectroscopy. Biomacromolecules, 14, 1885-1892. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Sun J, Yu L, Zhang C, Bi J, Zhu F, Qu M, Jiang C, Yang Q. Extraction and characterization of chitin from the beetle Holotrichia parallela Motschulsky. Molecules. 2012 Apr 17;17(4):4604-11. [CrossRef]

- Zainol Abidin NA, Kormin F, Zainol Abidin NA, Mohamed Anuar NAF, Abu Bakar MF. The Potential of Insects as Alternative Sources of Chitin: An Overview on the Chemical Method of Extraction from Various Sources. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Jul 15;21(14):4978. [CrossRef]

- Kimura S, et al. Infrared and terahertz spectromicroscopy beam line BL6B(IR) at UVSOR-II. Infrared Phys Technol. 2006; 49: 147–51. [CrossRef]

- Devi A, Bajar S, Kour H, Kothari R, Pant D, Singh A. Lignocellulosic Biomass Valorization for Bioethanol Production: a Circular Bioeconomy Approach. Bioenergy Res. 2022;15(4):1820-1841. [CrossRef]

- Zhan Y, Wang M, Ma T, Li Z. Enhancing the potential production of bioethanol with bamboo by γ-valerolactone/water pretreatment. RSC Adv. 2022 Jun 7;12(26):16942-16954. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C. Industrial-Scale Production and Applications of Bacterial Cellulose. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020 Dec 22;8:605374. [CrossRef]

- Sharma A, Thakur M, Bhattacharya M, Mandal T, Goswami S. Commercial application of cellulose nano-composites - A review. Biotechnol Rep (Amst). 2019 Feb 15;21:e00316. [CrossRef]

- Šaravanja A, Pušić T, Dekanić T. Microplastics in Wastewater by Washing Polyester Fabrics. Materials (Basel). 2022 Apr 6;15(7):2683. [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Mateo C, van der Meer Y, Seide G. Analysis of the polyester clothing value chain to identify key intervention points for sustainability. Environ Sci Eur. 2021;33(1):2. [CrossRef]

- Xue Y, Lofland S, Hu X. Thermal Conductivity of Protein-Based Materials: A Review. Polymers (Basel). 2019 Mar 11;11(3):456. [CrossRef]

- Wu R, Ma L, Liu XY. From Mesoscopic Functionalization of Silk Fibroin to Smart Fiber Devices for Textile Electronics and Photonics. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2022 Feb;9(4):e2103981. [CrossRef]

- Al-Tohamy R, Ali SS, Li F, Okasha KM, Mahmoud YA, Elsamahy T, Jiao H, Fu Y, Sun J. A critical review on the treatment of dye-containing wastewater: Ecotoxicological and health concerns of textile dyes and possible remediation approaches for environmental safety. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2022 Feb;231:113160. [CrossRef]

- Sałdan, A.; Król, M.; Wo’ zniakiewicz, M.; Ko’ scielniak, P. Application of Capillary Electromigration Methods in the Analysis of Textile Dyes—Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristin H. Cochran, Jeremy A. Barry, David C. Muddiman, and David Hinks. Direct Analysis of Textile Fabrics and Dyes Using Infrared Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 831−836.

- Pelch KE, McKnight T, Reade A. 70 analyte PFAS test method highlights need for expanded testing of PFAS in drinking water. Sci Total Environ. 2023 Jun 10;876:162978. [CrossRef]

- Nancy Wolf, Lina Müller, Sarah Enge, Tina Ungethüm & Thomas J. Simat (2024) Analysis of PFAS and further VOC from fluoropolymer-coated cookware by thermal desorption-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (TD-GC-MS), Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A, 41:12, 1663-1678. [CrossRef]

| Carbohydrate polymers | Analytical techniques | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Amylose | NIR, Raman, CE, AFM SEC, MALLS, 1H NMR |

40 41 |

| Amylopectin | SEC, MALLS, DSC SEM, XRD, FT-IR, 1H NMR, HPAEC-PAD, DSC, RVA |

42 43 |

| Glycogen | MALDI-MSI, N-glycosidase hydrolysis | 45 |

| Cellulose |

1H NMR, PAS TG |

46 47 |

| Chitin | FT-IR, XRD, SEM XRD, FT-IR, UV-Vis, MS, 13C NMR |

48 49 |

| Heparin | LC-MS, SAX ATR-FTIR |

50 51 |

| Hyaluronic acid | HPLC-SEC Nanopore sensor |

52 53 |

| Glucomannan | TLC, FT-IR, 13C NMR | 54 |

| N-Glycan | CE, MALDI-MS, ESI-MS | 55 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).