Submitted:

16 July 2025

Posted:

17 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Hydrogels

2.1. Types of Hydrogels Used in Energy Applications

2.1.1. Natural Hydrogels

2.1.2. Synthetic Hydrogels

2.1.3. Composite Hydrogels

2.1.4. Carbon-Based Hydrogels

2.1.5. Conductive Polymer Hydrogels

2.1.6. MOF Hydrogels

2.2. Preparation Methods of Hydrogels

2.2.1. Materials for Hydrogel Formation

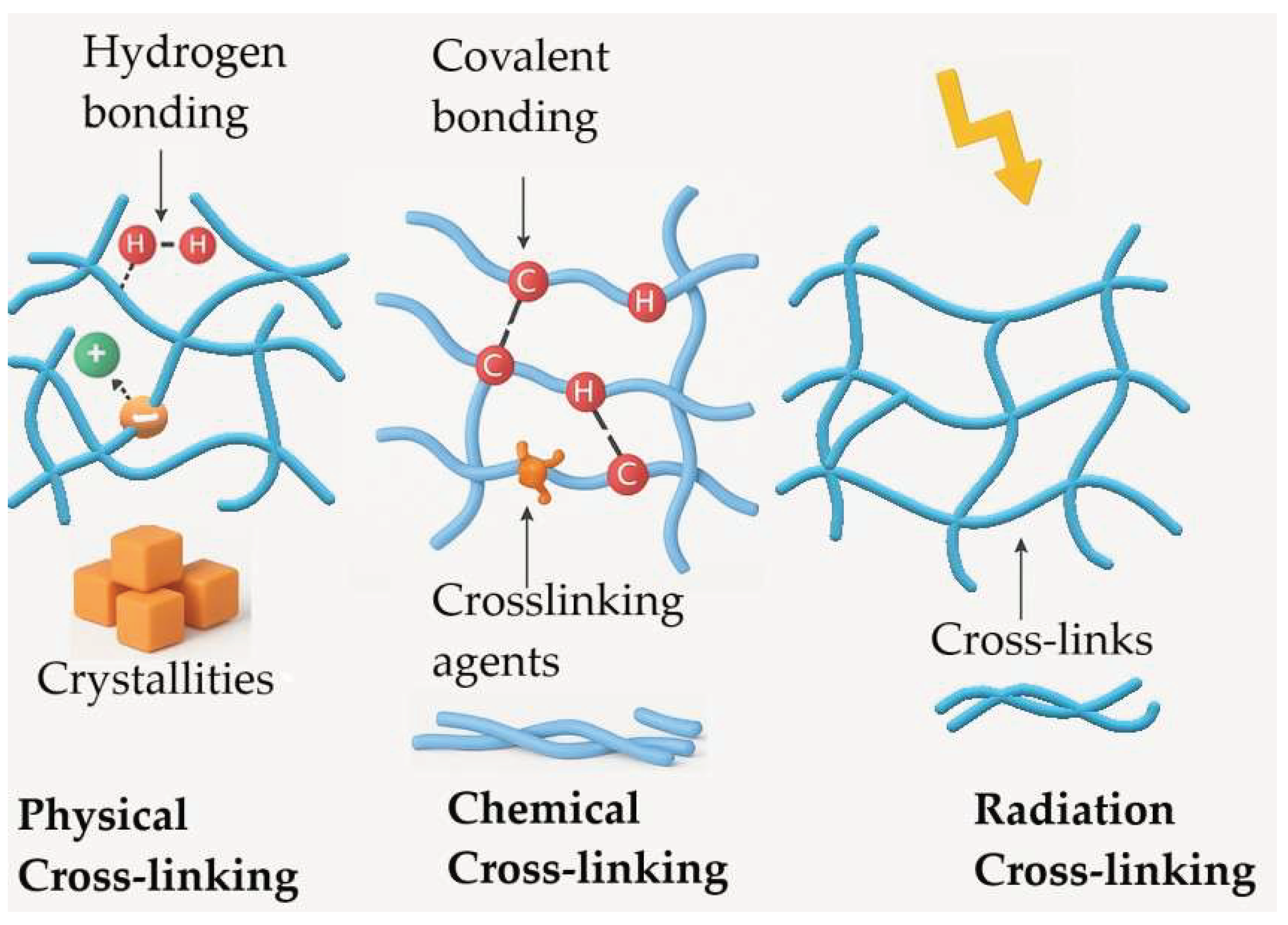

2.2.2. Physical Cross-Linking

2.2.3. Chemical Cross-Linking

2.2.4. Irradiation-Based Cross-Linking

2.3. Structural and Morphological Characterization

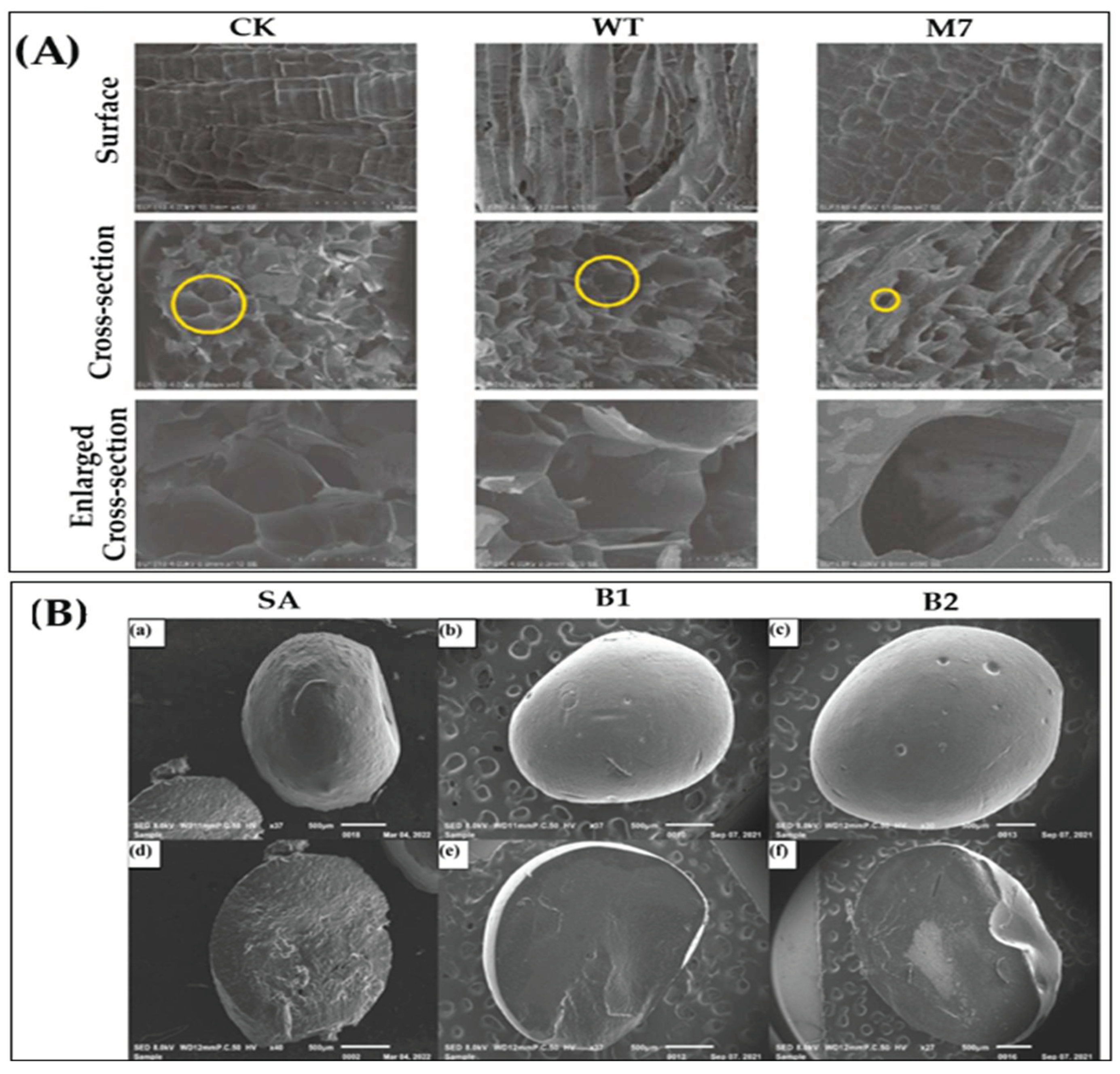

2.3.1. Microstructural Performance

2.3.2. Morphology Study

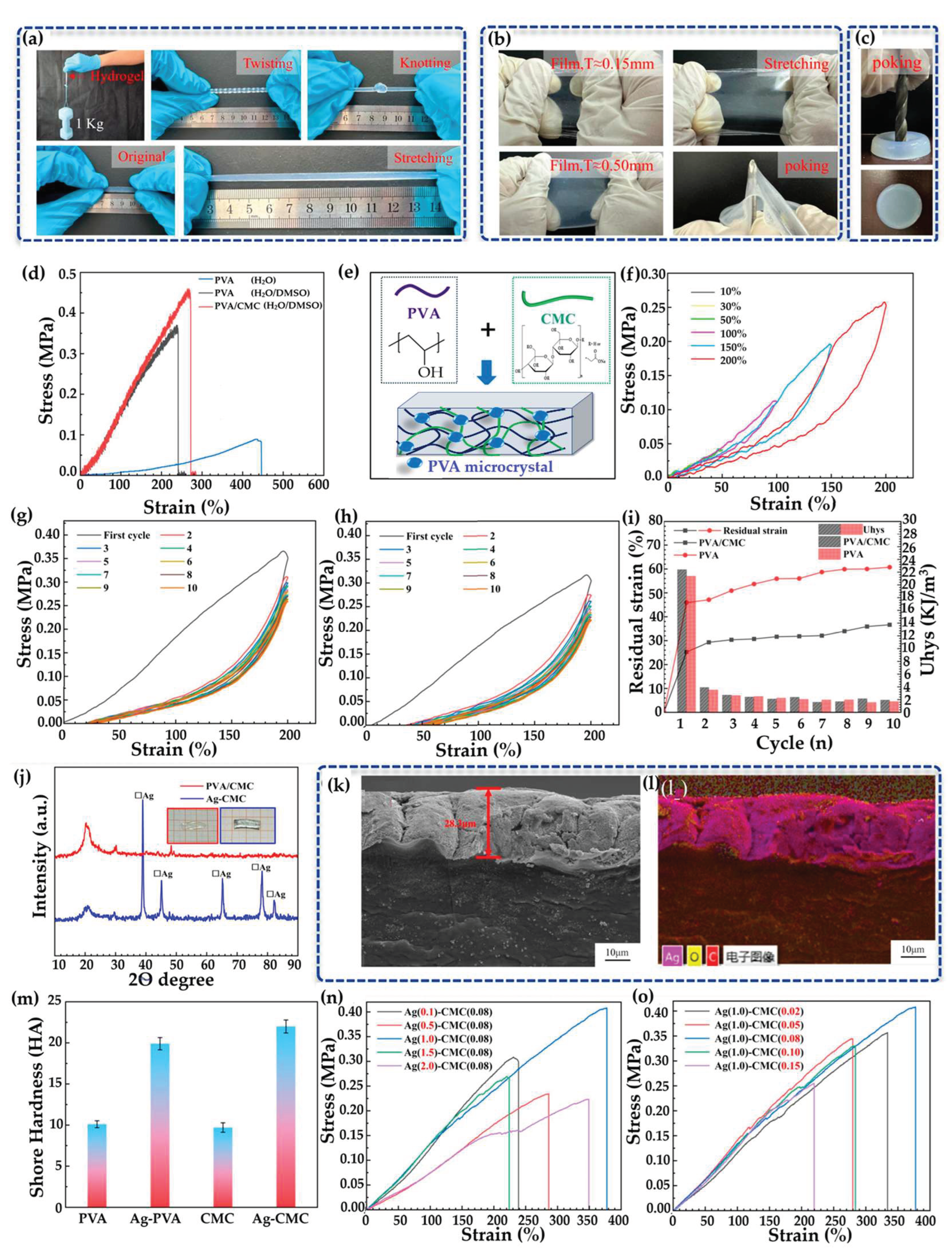

2.3.3. Mechanical Properties and Performance of Hydrogels

2.3.4. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.3.5. Viscoelastic Properties

3. Hydrogel-Based Materials in Energy Storage Applications

3.1. Hydrogels in Batteries

3.2. Hydrogels in Li-ion Batteries

3.2.1. Hydrogel-Derived Electrodes

3.2.2. Hydrogel-Derived Binders

3.2.3. Hydrogel Electrolytes for Aqueous Lithium-Ion Batteries

3.2.4. Hydrogels Under Extreme Conditions

3.3. Hydrogels for Sodium-Ion Batteries

3.3.1. Hydrogel Electrolytes for Sodium-Ion Batteries

3.3.2. Hydrogel Anodes for Sodium-Ion Batteries

3.3.3. Hydrogel Cathodes for Sodium-Ion Batteries

3.4. Hydrogel Electrolytes for Zinc-Ion Battery

3.4.1. High-Voltage Hydrogel-Based Zinc-Ion Batteries

3.4.2. Self-Healing Hydrogel-Based Zn-Ion Batteries

3.5. Hydrogels for Magnesium-Ion Batteries

3.5.1. Hydrogels as Electrolyte for MIBs

3.5.2. Hydrogel-Derived Anodes for MIBs

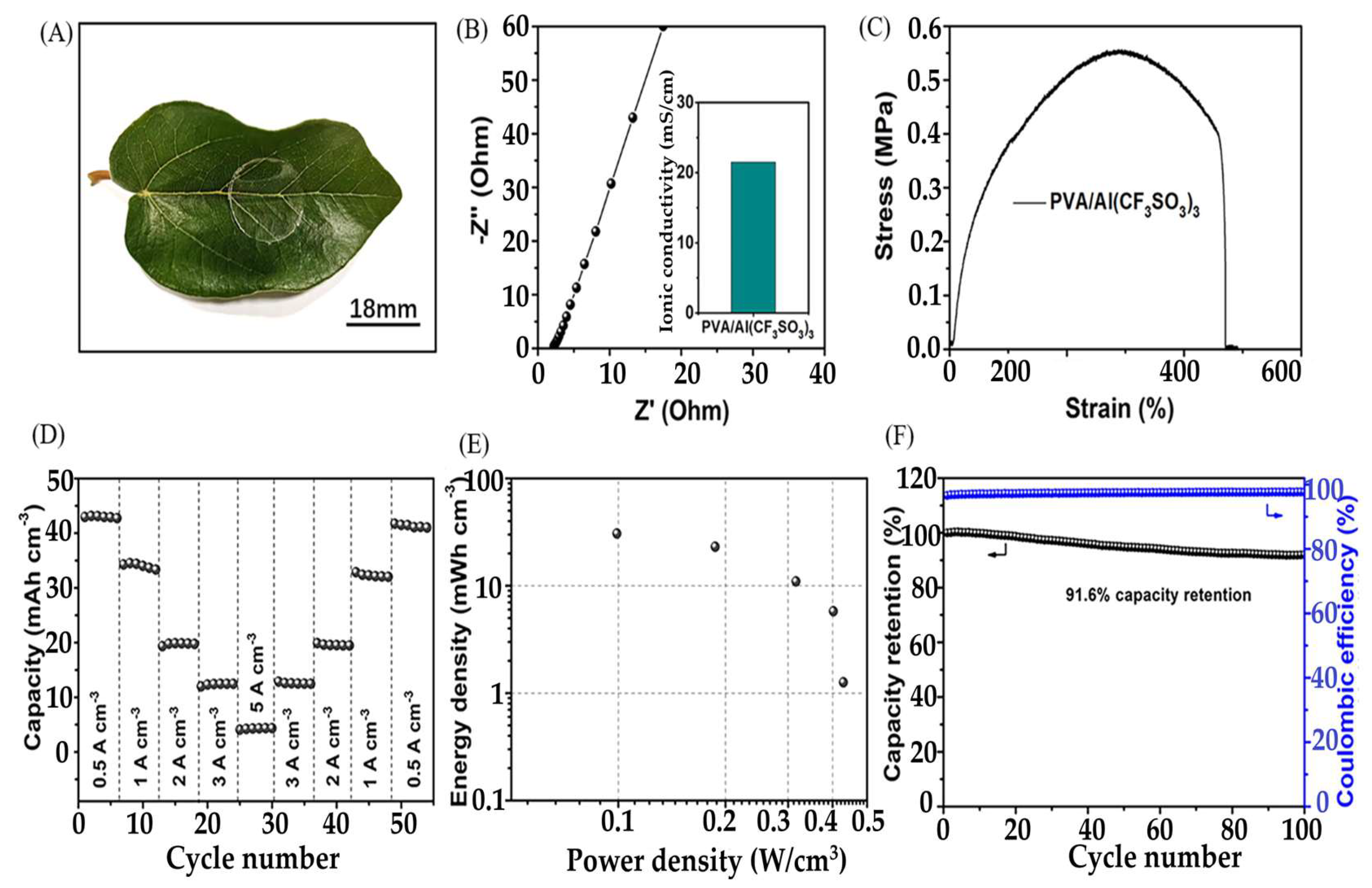

3.6. Hydrogels for Aluminum-Ion Batteries

3.6.1. Hydrogels as Electrolytes for AIBs

4. Challenges and Future Perspectives

4.1. Current Limitations in Hydrogel Applications

- Mechanical Strength and Durability: Despite their impressive flexibility, many hydrogels face limitations in mechanical strength and durability, particularly when subjected to harsh operating conditions such as temperature extremes, high humidity, or mechanical deformation. This results in performance degradation, which limits their use in long-term applications like wearable electronics or energy storage systems [258].

- Ionic Conductivity: The ionic conductivity of hydrogels, while suitable for some applications like supercapacitors, is often lower than that of traditional solid-state electrolytes or metal-based conductors. The challenge lies in optimizing the hydrogel matrix to improve ion transport without compromising other desirable properties such as biocompatibility and environmental.

- Scalability and Manufacturing: The scalability of hydrogel-based devices, especially for large-scale energy storage applications, remains a significant hurdle. Many hydrogel-based systems are difficult to manufacture uniformly at a large scale while maintaining consistent performance.

- Environmental and Biodegradability Concerns: While hydrogels are often considered eco-friendly, the degradation products of some synthetic hydrogels may raise concerns regarding their long-term environmental impact. Research is ongoing to develop fully biodegradable hydrogels that can break down harmlessly in natural environments.

4.2. Potential Solutions and Advancements

- Composite Hydrogels: The incorporation of conductive materials such as carbon nanotubes, graphene, and metallic nanoparticles into hydrogel matrices has shown promise in enhancing mechanical strength and conductivity. These composite hydrogels can offer the dual benefits of improved performance and flexibility, addressing the mechanical and conductivity issues simultaneously.

- 3D Printing and Smart Fabrication Techniques: Advances in 3D printing and other smart fabrication methods are enabling the precise control of hydrogel structures, allowing for the creation of hydrogels with tailored properties for specific energy applications. This includes optimizing pore structures for ion transport or adjusting the polymer networks for improved mechanical integrity.

- Self-Healing Hydrogels: Self-healing hydrogels, which can repair damage autonomously, offer an exciting avenue to overcome the durability challenges faced by hydrogels. By integrating dynamic covalent bonds or reversible cross-linking strategies, hydrogels can recover their function after being subjected to mechanical or environmental stress, which is crucial for ensuring long-term device reliability.

- Biodegradable and Sustainable Hydrogels: Research into biodegradable and bio-based hydrogels, such as those derived from polysaccharides, is advancing rapidly. These hydrogels not only mitigate environmental concerns but also possess excellent biocompatibility, which is essential for energy devices that interact with the human body, such as wearable sensors and bioelectronics.

4.3. Future Research Directions

- Interdisciplinary Collaboration: There is a growing need for interdisciplinary research that combines materials science, chemistry, and engineering to create hydrogels with optimized properties for specific applications. Collaborations between researchers in fields such as nanotechnology, organic electronics, and biomaterials are key to developing next-generation hydrogels for energy storage and conversion systems.

- High-Performance Batteries: Further research into the optimization of hydrogels for batteries, particularly for hybrid systems that combine both, is an exciting prospect. Focus should be on improving the energy density, stability, and cycling life of these devices through innovative hydrogel formulations.

5. Conclusion

5.1. Summary of Key Points

5.2. Impact of Hydrogels on the Future of Energy Materials and Devices

5.3. Final Thoughts

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elbinger, L.; Enke, M.; Ziegenbalg, N.; Brendel, J.C.; Schubert, U.S. Beyond Lithium-Ion Batteries: Recent Developments in Polymer-Based Electrolytes for Alternative Metal-Ion-Batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2024, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shi, P.; Xiang, H.; Liang, X.; Yu, Y. High-Safety Nonaqueous Electrolytes and Interphases for Sodium-Ion Batteries. Small 2019, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Xue, L.; Xin, S.; Goodenough, J.B. A High-Energy-Density Potassium Battery with a Polymer-Gel Electrolyte and a Polyaniline Cathode. Angew. Chemie 2018, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.S.; Ko, J.M.; Kim, D.W. Preparation and Characterization of Gel Polymer Electrolytes for Solid State Magnesium Batteries. In Proceedings of the Electrochimica Acta; 2004; Vol. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Qin, H.; Alfred, M.; Ke, H.; Cai, Y.; Wang, Q.; Huang, F.; Liu, B.; Lv, P.; Wei, Q. Reaction Modifier System Enable Double-Network Hydrogel Electrolyte for Flexible Zinc-Air Batteries with Tolerance to Extreme Cold Conditions. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanbua, C.; Sirichaibhinyo, T.; Rattanawongwiboon, T.; Lertsarawut, P.; Chanklinhorm, P.; Ummartyotin, S. Gamma Radiation-Induced Crosslinking of Ca2+ Loaded Poly(Acrylic Acid) and Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Diacrylate Networks for Polymer Gel Electrolytes. South African J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, A.; Köhler, T.; Biswas, S.; Stöcker, H.; Meyer, D.C. A Flexible Solid-State Ionic Polymer Electrolyte for Application in Aluminum Batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.X.; Song, P.; Wang, P.Y.; Chen, X.X.; Chen, T.; Yao, X.H.; Zhao, W.G.; Zhang, D.Y. Cartilage Structure-Inspired Elastic Silk Nanofiber Network Hydrogel for Stretchable and High-Performance Supercapacitors. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Liang, Q.; Mugo, S.M.; An, L.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, Y. Self-Healing and Shape-Editable Wearable Supercapacitors Based on Highly Stretchable Hydrogel Electrolytes. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadesse, M.G.; Lübben, J.F. Review on Hydrogel-Based Flexible Supercapacitors for Wearable Applications. Gels 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungureanu, C.; Răileanu, S.; Zgârian, R.; Tihan, G.; Burnei, C. State-of-the-Art Advances and Current Applications of Gel-Based Membranes. Gels 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wu, C.H.; Li, F.; Wang, X.; Chen, S.C. Enhancing the Proton Exchange Membrane in Tubular Air-Cathode Microbial Fuel Cells through a Hydrophobic Polymer Coating on a Hydrogel. Materials (Basel). 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Kim, M.; Jo, N.; Kim, K.M.; Lee, C.; Kwon, T.H.; Nam, Y.S.; Ryu, J. Amine-Rich Hydrogels for Molecular Nanoarchitectonics of Photosystem II and Inverse Opal TiO2 toward Solar Water Oxidation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armand, M.; Tarascon, J.M. Building Better Batteries. Nature 2008, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, P.G.; Scrosati, B.; Tarascon, J.M. Nanomaterials for Rechargeable Lithium Batteries. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 2008, 47.

- Russo, R.; Becuwe, M.; Frayret, C.; Stevens, P.; Toussaint, G. Optimization of Disodium Naphthalene Dicarboxylates Negative Electrode for Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Sodium Batteries. ECS Meet. Abstr. 2022, MA2022-01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Tang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Ruan, Z.; Ma, L.; Yang, Q.; Wang, D.; Zhi, C. Hydrogel Electrolytes for Flexible Aqueous Energy Storage Devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, N.; Cui, Y. Promises and Challenges of Nanomaterials for Lithium-Based Rechargeable Batteries. Nat. Energy 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Huang, H.S.; Wang, Y.Y.; Zhang, Y.S.; Chakravarthy, R.D.; Yeh, M.Y.; Lin, H.C.; Wei, J. Stretchable, Adhesive, and Biocompatible Hydrogel Based on Iron–Dopamine Complexes. Polymers (Basel). 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, G.; Chou, S.L.; Tang, Y. Electrochemical Energy Storage Devices Working in Extreme Conditions. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantaray, S.; Mohanty, D.; Satpathy, S.K. Academic Editors: Zetian Tao and César Augusto Correia de Sequeira Molecules Exploring Recent Developments in Graphene-Based Cathode Materials for Fuel Cell Applications: A Comprehensive Overview. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Segura Zarate, A.Y.; Gontrani, L.; Galliano, S.; Bauer, E.M.; Donia, D.T.; Barolo, C.; Bonomo, M.; Carbone, M. Green Zinc/Galactomannan-Based Hydrogels Push up the Photovoltage of Quasi Solid Aqueous Dye Sensitized Solar Cells. Sol. Energy 2024, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünlü, B.; Türk, S.; Özacar, M. Novel Anti-Freeze and Self-Adhesive Gellan Gum/P3HT/LiCl Based Gel Electrolyte for Quasi Solid Dye Sensitized Solar Cells. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanti, P.K.; K. , D.J.; Swapnalin, J.; Vicki Wanatasanappan, V. Advancements and Prospects of MXenes in Emerging Solar Cell Technologies. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2025, 285, 113540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Liu, Z.; Qu, J.; Meng, C.; He, L.; Li, L.; Yang, X.; Cao, Y.; Han, K.; Zhang, Y. High-Performance Organic–Inorganic Hybrid Conductive Hydrogels for Stretchable Elastic All-Hydrogel Supercapacitors and Flexible Self-Powered Integrated Systems. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2403358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyoshima, Y.; Kawamura, A.; Takashima, Y.; Miyata, T. Design of Molecularly Imprinted Hydrogels with Thermoresponsive Drug Binding Sites. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, D.C.S.; Costa, P.D.C.; Gomes, M.C.; Chandrakar, A.; Wieringa, P.A.; Moroni, L.; Mano, J.F. Universal Strategy for Designing Shape Memory Hydrogels. ACS Mater. Lett. 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Dai, Z.; Sheng, X.; Xia, D.; Shao, P.; Yang, L.; Luo, X. Conducting Polymer Hydrogels as a Sustainable Platform for Advanced Energy, Biomedical and Environmental Applications. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Song, H.-S.; Mahamudul, M.; Rumon, H.; Mizanur, M.; Khan, R.; Jeong, J.-H. Toward Intelligent Materials with the Promise of Self-Healing Hydrogels in Flexible Devices. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Zhong, W.; Li, T.; Han, J.; Sun, X.; Tong, X.; Zhang, Y. A Review of Self-Healing Electrolyte and Their Applications in Flexible/Stretchable Energy Storage Devices. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, R.; Laberty-Robert, C.; Pelta, J.; Tarascon, J.M.; Dominko, R. Self-Healing: An Emerging Technology for Next-Generation Smart Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhao, H.; Song, K.; Han, F.; Liu, Z.; Tian, Q. Flexible and Stretchable Implantable Devices for Peripheral Neuromuscular Electrophysiology. Nanoscale 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, C.; Kim, A.; Lim, D.Y.; Ullah, A.; Kim, D.Y.; Lim, S.I. Lim, H.-R. Hydrogel-Based Biointerfaces: Recent Advances, Challenges, and Future Directions in Human-Machine Integration. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Bae, J.; Zhao, F.; Yu, G. Functional Hydrogels for Next-Generation Batteries and Supercapacitors. Trends Chem. 2019, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.; Gund, G.S.; Qi, K.; Nakhanivej, P.; Liu, H.; Li, F.; Xia, B.Y.; Park, H.S. Hybridization Design of Materials and Devices for Flexible Electrochemical Energy Storage. Energy Storage Mater. 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Xu, X. Evolution and Application of All-in-One Electrochemical Energy Storage System. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Feng, A.; Mao, S.; Onggowarsito, C.; Stella Zhang, X.; Guo, W.; Fu, Q. Hydrogels in Solar-Driven Water and Energy Production: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 492, 152303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recent Advances, Y.; Duan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, P.; Mao, Y. Citation: Duan, H Recent Advances of Stretchable Nanomaterial-Based Hydrogels for Wearable Sensors and Electrophysiological Signals Monitoring. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Huyan, C.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, X.; Torun, H.; Mulvihill, D.; Xu, B. Bin; Chen, F. Conductive Polymer Based Hydrogels and Their Application in Wearable Sensors: A Review. Mater. Horizons 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.; Lee, H.S.; Jeong, H.; Kim, D.-H. Recent Advances in Conductive Hydrogels for Soft Biointegrated Electronics: Materials, Properties, and Device Applications. Wearable Electron. 2024, 1, 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gashti, M.P.; María, J.; Moreno, C.; Chelu, M.; Popa, M. Academic Editors: Massimo Mariello Eco-Friendly Conductive Hydrogels: Towards Green Wearable Electronics. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Sharma, R.; Pani, B.; Sarkar, A.; Tripathi, M. Engineering the Future with Hydrogels: Advancements in Energy Storage Devices and Biomedical Technologies †. New J. Chem 2024, 48, 10347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.N.; Meena, A.; Nam, K.W. Gels in Motion: Recent Advancements in Energy Applications. Gels 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, A.S.; Kannan, K.; Henry, J.; Aepuru, R.; Shanmugaraj, K.; Pabba, D.P.; Sathish, M. Advancements in Hydrogel Materials for Next-Generation Energy Devices: Properties, Applications, and Future Prospects. Cellulose 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 14 Ref 4.

- Chen, J.; Liu, F.; Abdiryim, T.; Liu, X. An Overview of Conductive Composite Hydrogels for Flexible Electronic Devices. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2024, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, M.M. El Production of Polymer Hydrogel Composites and Their Applications. 2023, 31, 2855–2879. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zheng, S.Y.; Xiao, R.; Yin, J.; Wu, Z.L.; Zheng, Q.; Qian, J. Constitutive Behaviors of Tough Physical Hydrogels with Dynamic Metal-Coordinated Bonds. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2020, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Chu, C.R.; Payne, K.A.; Marra, K.G. Injectable in Situ Forming Biodegradable Chitosan-Hyaluronic Acid Based Hydrogels for Cartilage Tissue Engineering. Biomaterials 2009, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, A.S.; Premanand, R.; Ragupathi, I.; Rao Bhaviripudi, V.; Aepuru, R.; Kannan, K.; Shanmugaraj, K. Comprehensive Review of Hydrogel Synthesis, Characterization, and Emerging Applications. 2024. [CrossRef]

- More, A.P.; Chapekar, S. Irradiation Assisted Synthesis of Hydrogel: A Review. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 5839–5908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.S.; Islam, M.; Hasan, M.K.; Nam, K.-W. AComprehensive Review of Radiation-Induced Hydrogels: Synthesis, Properties, and Multidimensional Applications. Gels 2024, 10, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.A.; Jeong, J.O.; Park, S.H. State-of-the-Art Irradiation Technology for Polymeric Hydrogel Fabrication and Application in Drug Release System. Front. Mater. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickett, T.A.; Amoozgar, Z.; Tuchek, C.A.; Park, J.; Yeo, Y.; Shi, R. Rapidly Photo-Cross-Linkable Chitosan Hydrogel for Peripheral Neurosurgeries. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishihara, M.; Obara, K.; Nakamura, S.; Fujita, M.; Masuoka, K.; Kanatani, Y.; Takase, B.; Hattori, H.; Morimoto, Y.; Ishihara, M.; et al. Chitosan Hydrogel as a Drug Delivery Carrier to Control Angiogenesis. J. Artif. Organs 2006, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigoin, J.; Payré, B.; Moncla, J.M.; Escudero, M.; Goudouneche, D.; Ferri-Angulo, D.; Calmon, P.-F.O.; Vaysse, L.; Kemoun, P.; Malaquin, L.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Electron Microscopy Techniques for Hydrogel Microarchitecture Characterization: SEM, Cryo-SEM, ESEM, and TEM. 2025, 10, 14687–14698. [CrossRef]

- Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, S.; Biermann, M.; Kara, S.; Stefan Jopp, cd; Meyer, J. A Novel Characterization Technique for Hydrogels-in Situ Rheology-Raman Spectroscopy for Gelation and Polymerization Tracking †. Cite this Mater. Adv 2024, 5, 6957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppas, N.A.; Keys, K.B.; Torres-Lugo, M.; Lowman, A.M. Poly(Ethylene Glycol)-Containing Hydrogels in Drug Delivery. J. Control. Release 1999, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Long, M.; Zheng, N.; Deng, Y.; Wang, Q.; Osire, T.; Xia, X. Microstructural, Physicochemical Properties, and Interaction Mechanism of Hydrogel Nanoparticles Modified by High Catalytic Activity Transglutaminase Crosslinking. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Camargo, S.; Román-Guerrero, A.; Alvarez-Ramirez, J.; Alpizar-Reyes, E.; Velázquez-Gutiérrez, S.K.; Pérez-Alonso, C. Microstructural Influence on Physical Properties and Release Profiles of Sesame Oil Encapsulated into Sodium Alginate-Tamarind Mucilage Hydrogel Beads. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Lalhall, A.; Puri, S.; Wangoo, N. Design of Fmoc-Phenylalanine Nanofibrillar Hydrogel and Mechanistic Studies of Its Antimicrobial Action against Both Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yao, J.; Li, L.; Zhu, F.; Liu, Z.; Zeng, X.; Yu, X.; Huang, Z. Reinforced Polyaniline/Polyvinyl Alcohol Conducting Hydrogel from a Freezing–Thawing Method as Self-Supported Electrode for Supercapacitors. J. Mater. Sci. 2016, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Chen, R.; Yang, S.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Huang, J. Facile Fabrication of MnO2-Embedded 3-D Porous Polyaniline Composite Hydrogel for Supercapacitor Electrode with High Loading. High Perform. Polym. 2020, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lali Raveendran, R.; Valsala, M.; Sreenivasan Anirudhan, T. Development of Nanosilver Embedded Injectable Liquid Crystalline Hydrogel from Alginate and Chitosan for Potent Antibacterial and Anticancer Applications. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2023, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Chang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Q.; Guo, M.; Zhao, J.; Wu, S.; Ma, Y. Advanced In-Situ Functionalized Conductive Hydrogels with High Mechanical Strength for Hypersensitive Soft Strain Sensing Applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhadir, K.H.; Alsberg, E.; Mooney, D.J. Hydrogels for Combination Delivery of Antineoplastic Agents. Biomaterials 2001, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medha; Sethi, S. ; Mahajan, P.; Thakur, S.; Sharma, N.; Singh, N.; Kumar, A.; Kaur, A.; Kaith, B.S. Design and Evaluation of Fluorescent Chitosan-Starch Hydrogel for Drug Delivery and Sensing Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 274, 133486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enoch, K.; C. S, R.; Somasundaram, A.A. Tuning the Rheological Properties of Chitosan/Alginate Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering Application. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 697, 134434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.; Hu, K.H.; Butte, M.J.; Chaudhuri, O. Strain-Enhanced Stress Relaxation Impacts Nonlinear Elasticity in Collagen Gels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Li, B.; Xie, M.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, H.; Qiu, L.; Huang, L.; et al. Triple-Crosslinked Double-Network Alginate/Dextran/Dendrimer Hydrogel with Tunable Mechanical and Adhesive Properties: A Potential Candidate for Sutureless Keratoplasty. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 344, 122538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacopardo, L.; Guazzelli, N.; Nossa, R.; Mattei, G.; Ahluwalia, A. Engineering Hydrogel Viscoelasticity. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2019, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, W.; Wang, P.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Ji, Z.; Fei, J.; Ma, Z.; He, N.; Huang, Y. Nanostructure Design Strategies for Aqueous Zinc-Ion Batteries. ChemElectroChem 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Yang, J.L.; Liu, K.; Fan, H.J. Hydrogels Enable Future Smart Batteries. ACS Nano. 2022, 16, 15528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Li, L.; Yue, S.; Jia, S.; Wang, C.; Zhang, D. Electrolytes for Aluminum-Ion Batteries: Progress and Outlook. Chem. Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202402017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.K.; Zhao, C.Z.; Du, J.; Zhang, X.Q.; Chen, A.B.; Zhang, Q. Research Progresses of Liquid Electrolytes in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Small 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Zhao, L.; Li, Y.; Qin, X.; Li, J.; Han, W.; Wang, L. Review of Design Routines of MXene Materials for Magnesium-Ion Energy Storage Device. Small 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.; Dhankhar, M. Sodium Ion (Na+) Batteries–a Comprehensive Review. Mater. Nanosci. 2024, 11, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janek, J.; Zeier, W.G. A Solid Future for Battery Development. Nat. Energy 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldoon, J.; Bucur, C.B.; Gregory, T. Quest for Nonaqueous Multivalent Secondary Batteries: Magnesium and Beyond. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Ahmed, M.S.; Han, D.; Bari, G.A.K.M.R.; Nam, K.-W. Electrochemical Storage Behavior of a High-Capacity Mg-Doped P2-Type Na2/3Fe1−yMnyO2 Cathode Material Synthesized by a Sol–Gel Method. Gels 2024, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Kim, D.H.; Shin, J.H.; Jang, J.E.; Ahn, K.H.; Lee, C.; Lee, H. Ionic Conduction and Solution Structure in LiPF6 and LiBF4 Propylene Carbonate Electrolytes. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Qian, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, X.; Goodenough, J.B.; Yu, G. Polar Polymer-Solvent Interaction Derived Favorable Interphase for Stable Lithium Metal Batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Chen, J.; Qing, T.; Fan, X.; Sun, W.; von Cresce, A.; Ding, M.S.; Borodin, O.; Vatamanu, J.; Schroeder, M.A.; et al. 4.0 V Aqueous Li-Ion Batteries. Joule 2017, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feig, V.R.; Tran, H.; Lee, M.; Bao, Z. Mechanically Tunable Conductive Interpenetrating Network Hydrogels That Mimic the Elastic Moduli of Biological Tissue. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Ahmed, M.S.; Faizan, M.; Ali, B.; Bhuyan, M.M.; Bari, G.A.K.M.R.; Nam, K.-W. Review on the Polymeric and Chelate Gel Precursor for Li-Ion Battery Cathode Material Synthesis. Gels 2024, 10, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohzuku, T.; Ueda, A. Solid-State Redox Reactions of LiCoO2 (R3m) for 4 Volt Secondary Lithium Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1994, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Rui, X.; Qi, D.; Luo, Y.; Leow, W.R.; Chen, S.; Guo, J.; Wei, J.; Li, W.; et al. Conductive Inks Based on a Lithium Titanate Nanotube Gel for High-Rate Lithium-Ion Batteries with Customized Configuration. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shi, Y.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yu, G. In Situ Reactive Synthesis of Polypyrrole-MnO2 Coaxial Nanotubes as Sulfur Hosts for High-Performance Lithium-Sulfur Battery. Nano Lett. 2016, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, X.; Jiang, L.; Wu, C.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, X.; Hu, B.; Yi, L. The Effects of Electrolyte on the Supercapacitive Performance of Activated Calcium Carbide-Derived Carbon. J. Power Sources 2013, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Zhou, W.; Yu, H.; Pu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, C. Template Synthesis of Hierarchical Mesoporous δ-MnO2 Hollow Microspheres as Electrode Material for High-Performance Symmetric Supercapacitor. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, M.; Chen, B.; Leung, D.Y.C.; Xuan, J.; Wang, H. A Hydrogel Template Synthesis of TiO2 Nanoparticles for Aluminium-Ion Batteries. In Proceedings of the Energy Procedia; 2017; Vol. 105. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, K.A.; Lim, H.S.; Sun, Y.K.; Suh, K. Do α-Fe2O3 Submicron Spheres with Hollow and Macroporous Structures as High-Performance Anode Materials for Lithium Ion Batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, G.; Ishihara, Y.; Kanamori, K.; Miyazaki, K.; Yamada, Y.; Nakanishi, K.; Abe, T. Facile Preparation of Monolithic LiFePO4/Carbon Composites with Well-Defined Macropores for a Lithium-Ion Battery. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, H.; Bae, J.; Chung, S.H.; Zhang, W.; Manthiram, A.; Yu, G. Nanostructured Host Materials for Trapping Sulfur in Rechargeable Li–S Batteries: Structure Design and Interfacial Chemistry. Small Methods 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yu, G.; Cha, J.J.; Wu, H.; Vosgueritchian, M.; Yao, Y.; Bao, Z.; Cui, Y. Improving the Performance of Lithium-Sulfur Batteries by Conductive Polymer Coating. ACS Nano 2011, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.J.; Kang, J.G.; Kim, D.W. Fibrin Biopolymer Hydrogel-Templated 3D Interconnected Si@C Framework for Lithium Ion Battery Anodes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introduction and Adhesion Theories. In Adhesives Technology Handbook; 2009.

- Li, G.; Li, C.; Li, G.; Yu, D.; Song, Z.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, W. Development of Conductive Hydrogels for Fabricating Flexible Strain Sensors. Small 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, A.; Haag, R.; Schedler, U. Hydrogels and Their Role in Biosensing Applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, F.; Manthiram, A. A Review of the Design of Advanced Binders for High-Performance Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lee, S.H.; Cho, M.; Kim, J.; Lee, Y. Cross-Linked Chitosan as an Efficient Binder for Si Anode of Li-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yao, R.; Wang, S.; Wei, Y.; Chen, B.; Liang, W.; Tian, C.; Nie, C.; Li, D.; Chen, Y. Rational Design of Stretchable and Conductive Hydrogel Binder for Highly Reversible SiP2 Anode. J. Energy Chem. 2023, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Liu, F.; Liu, Y.; Dong, J.; Liu, M.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L. Self-Assembled Three-Dimensional Si/Carbon Frameworks as Promising Lithium-Ion Battery Anode. J. Power Sources 2023, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Z.; Di, S.; Chen, L.; Wu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, C.; Zhang, N.; Liu, X.; Chen, G. Random Copolymer Hydrogel as Elastic Binder for the SiO XMicroparticle Anode in Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, P.; Sun, C.; Gao, C.; Li, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Dong, S.; Cui, G. Dual Network Electrode Binder toward Practical Lithium-Sulfur Battery Applications. ACS Energy Lett. 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; To, J.W.F.; Wang, C.; Lu, Z.; Liu, N.; Chortos, A.; Pan, L.; Wei, F.; Cui, Y.; Bao, Z. A Three-Dimensionally Interconnected Carbon Nanotube-Conducting Polymer Hydrogel Network for High-Performance Flexible Battery Electrodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yan, C.; Xu, L.; Xu, N.; Wu, X.; Jiang, Z.; Zhu, S.; Diao, G.; Chen, M. Super Flexible Cathode Material with 3D Cross-Linking System Based on Polyvinyl Alcohol Hydrogel for Boosting Aqueous Zinc Ion Batteries. ChemElectroChem 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ding, J.; Liu, Z.; Wei, Y.; Cheng, W.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.C.; Zhang, W.; Wang, B.; et al. Novel-Designed Cobweb-like Binder by “Four-in-One” Strategy for High Performance SiO Anode. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, Z.Y.; Wu, J.H.; Li, J.T.; Huang, L.; Sun, S.G. A High-Performance Alginate Hydrogel Binder for the Si/C Anode of a Li-Ion Battery. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ye, T.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, L.; Li, F.; He, E.; Zhang, Y. Ultrasoft All-Hydrogel Aqueous Lithium-Ion Battery with a Coaxial Fiber Structure. Polym. J. 2022, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Li, B.Q.; Zhang, X.Q.; Huang, J.Q.; Zhang, Q. A Perspective toward Practical Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Bo, R.; Taheri, M.; Di Bernardo, I.; Motta, N.; Chen, H.; Tsuzuki, T.; Yu, G.; Tricoli, A. Metal-Organic Frameworks/Conducting Polymer Hydrogel Integrated Three-Dimensional Free-Standing Monoliths as Ultrahigh Loading Li-S Battery Electrodes. Nano Lett. 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.L.; Gong, Y.D.; Miao, C.; Wang, Q.; Nie, S.Q.; Xin, Y.; Wen, M.Y.; Liu, J.; Xiao, W. Sn Nanoparticles Embedded into Porous Hydrogel-Derived Pyrolytic Carbon as Composite Anode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Rare Met. 2022, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Liu, K.; Sheng, N.; Zhang, M.; Liu, W.; Liu, H.; Dai, L.; Zhang, X.; Si, C.; Du, H.; et al. Biopolymer-Based Hydrogel Electrolytes for Advanced Energy Storage/Conversion Devices: Properties, Applications, and Perspectives. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.S.; Islam, M.; Raut, B.; Yun, S.; Kim, H.Y.; Nam, K.-W. A Comprehensive Review of Functional Gel Polymer Electrolytes and Applications in Lithium-Ion Battery. Gels 2024, 10, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Chen, X. All-Temperature Flexible Supercapacitors Enabled by Antifreezing and Thermally Stable Hydrogel Electrolyte. Nano Lett. 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Chen, S.; Wang, D.; Yang, Q.; Mo, F.; Liang, G.; Li, N.; Zhang, H.; Zapien, J.A.; Zhi, C. Super-Stretchable Zinc–Air Batteries Based on an Alkaline-Tolerant Dual-Network Hydrogel Electrolyte. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, C.; Chi, X.; Wen, B.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y. Water/Sulfolane Hybrid Electrolyte Achieves Ultralow-Temperature Operation for High-Voltage Aqueous Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Lv, T.; Dong, K.; Liu, Y.; Qi, Y.; Cao, S.; Chen, T. Ultrafast Self-Assembly of Supramolecular Hydrogels toward Novel Flame-Retardant Separator for Safe Lithium Ion Battery. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Bai, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Zheng, J.; Chen, G.; Huang, B. Self-Protecting Aqueous Lithium-Ion Batteries. Small 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zeng, S.; Li, W.; Lin, H.; Zhong, H.; Zhu, H.; Mai, Y. Stretchable Hydrogel Electrolyte Films Based on Moisture Self-Absorption for Flexible Quasi-Solid-State Batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, F.; Shi, Y.; Goodenough, J.B.; Yu, G. A 3D Nanostructured Hydrogel-Framework-Derived High-Performance Composite Polymer Lithium-Ion Electrolyte. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 2018, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Tan, D.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, T.; Hu, F.; Sun, N.; Huang, J.; Fang, C.; Ji, R.; Bi, S.; et al. High-Performance Fully-Stretchable Solid-State Lithium-Ion Battery with a Nanowire-Network Configuration and Crosslinked Hydrogel. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhao, S.; Fei, J.; Wei, L.; Chen, J.; Wang, C.; Qi, R.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y. . AFlexible RechargeableZinc–Air Battery with Excellent Low-Temperature Adaptability. Angew.Chem. Int.Ed. 2020, 59, 4793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Wang, X.; Tang, H.; Wang, J.; Hao, Q.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, K.; Schmidt, O.G. Antifreezing Hydrogel with High Zinc Reversibility for Flexible and Durable Aqueous Batteries by Cooperative Hydrated Cations. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Chen, J.; Ji, X.; Pollard, T.P.; Lü, X.; Sun, C.J.; Hou, S.; Liu, Q.; Liu, C.; Qing, T.; et al. Aqueous Li-Ion Battery Enabled by Halogen Conversion–Intercalation Chemistry in Graphite. Nature 2019, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strachan, N.; Fais, B.; Daly, H. Reinventing the Energy Modelling–Policy Interface. Nat. Energy 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Floch, P.; Yao, X.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Nian, G.; Sun, Y.; Jia, L.; Suo, Z. Wearable and Washable Conductors for Active Textiles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuk, H.; Zhang, T.; Parada, G.A.; Liu, X.; Zhao, X. Skin-Inspired Hydrogel-Elastomer Hybrids with Robust Interfaces and Functional Microstructures. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.Y.; Keplinger, C.; Whitesides, G.M.; Suo, Z. Ionic Skin. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, L.; Borodin, O.; Gao, T.; Olguin, M.; Ho, J.; Fan, X.; Luo, C.; Wang, C.; Xu, K. “Water-in-Salt” Electrolyte Enables High-Voltage Aqueous Lithium-Ion Chemistries. Science (80-. ). 2015, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zheng, Y.; Zartashia, M.; Shan, Y.; Noor, H.; Lou, H.; Hou, X. Aqueous Dual-Electrolyte Full-Cell System for Improving Energy Density of Sodium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Luo, J.; Guo, X.; Chen, J.; Cao, Y.; Chen, W. Aqueous Rechargeable Sodium-Ion Batteries: From Liquid to Hydrogel. Batteries 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, X.; Niederberger, M.; Lizundia, E. A Sodium-Ion Battery Separator with Reversible Voltage Response Based on Water-Soluble Cellulose Derivatives. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.; Zang, X.; Hou, W.; Li, C.; Huang, Q.; Hu, X.; Sun, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Ma, F. Construction of Three-Dimensional Electronic Interconnected Na3V2(PO4)3/C as Cathode for Sodium Ion Batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Lu, Y.; Li, H.; Tao, Z.; Chen, J. High-Performance Aqueous Sodium-Ion Batteries with Hydrogel Electrolyte and Alloxazine/CMK-3 Anode. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Ma, Z.; Lin, H.; Rui, K.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Du, M.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, J.; et al. Hydrogel Self-Templated Synthesis of Na 3 V 2 (PO 4 ) 3 @C@CNT Porous Network as Ultrastable Cathode for Sodium-Ion Batteries. Compos. Commun. 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Chi, X.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y. Cost Attractive Hydrogel Electrolyte for Low Temperature Aqueous Sodium Ion Batteries. J. Energy Storage 2021, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, N.; Tien, S.; Lizundia, E.; Niederberger, M. Hierarchical Nanocellulose-Based Gel Polymer Electrolytes for Stable Na Electrodeposition in Sodium Ion Batteries. Small 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, S.; Li, L.; Wen, D.; Peng, X.; Zhang, H. Urchin-like MoS2/MoO2 Microspheres Coated with GO Hydrogel: Achieve a Long-Term Cyclability as Anode for Sodium Ion Batteries. Mater. Today Sustain. 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, J.P.; Fu, N.; Zhou, W. Bin; Liu, B.; Deng, Q.; Wu, X.W. Comprehensive Review on Zinc-Ion Battery Anode: Challenges and Strategies. InfoMat 2022, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Ang, E.H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, M.; Du, W.; Li, C.C. High-Voltage Zinc-Ion Batteries: Design Strategies and Challenges. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Wang, K.; Pei, P.; Wei, M.; Liu, X.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, P. Zinc Dendrite Growth and Inhibition Strategies. Mater. Today Energy 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhi, C.; Chen, S. Recent Advances in Electrolytes for “Beyond Aqueous” Zinc-Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Shi, L.; Wang, K.; Wang, B.; Li, L.; Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, Z.; Ali, W.; et al. An Overview and Future Perspectives of Rechargeable Zinc Batteries. Small 2020, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selis, L.A.; Seminario, J.M. Dendrite Formation in Li-Metal Anodes: An Atomistic Molecular Dynamics Study. RSC Adv. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Chao, Y.; Li, M.; Xiao, Y.; Li, R.; Yang, K.; Cui, X.; Xu, G.; Li, L.; Yang, C.; et al. A Review of Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) and Dendrite Formation in Lithium Batteries. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, N.; Ojanguren, A.; Kundu, D.; Lizundia, E.; Niederberger, M. Bottom-Up Design of a Green and Transient Zinc-Ion Battery with Ultralong Lifespan. Small 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.L.; Li, J.; Zhao, J.W.; Liu, K.; Yang, P.; Fan, H.J. Stable Zinc Anodes Enabled by a Zincophilic Polyanionic Hydrogel Layer. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Hyun Park, S.; Joung, D.; Kim, C. Sustainable Biopolymeric Hydrogel Interphase for Dendrite-Free Aqueous Zinc-Ion Batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, J.; Shen, X.; Wen, Z.; Wang, X.; Peng, L.; Zeng, J.; Zhao, J. Ultra-Stable and Highly Reversible Aqueous Zinc Metal Anodes with High Preferred Orientation Deposition Achieved by a Polyanionic Hydrogel Electrolyte. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Yu, H.; Fei, B.; Xin, J.H. Single-Ion Conducting Double-Network Hydrogel Electrolytes for Long Cycling Zinc-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Wang, Y.; Lu, C.; Zhou, S.; He, Q.; Hu, Y.; Feng, M.; Wan, Y.; Lin, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Modulation of Hydrogel Electrolyte Enabling Stable Zinc Metal Anode. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, W.; Mo, F.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Qiu, Y.; Huang, Y. Self-Healable Hydrogel Electrolyte for Dendrite-Free and Self-Healable Zinc-Based Aqueous Batteries. Mater. Today Phys. 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, H.; Gao, A.; Ling, J.; Yi, F.; Hao, J.; Li, Q.; Shu, D. Fundamental Study on Zn Corrosion and Dendrite Growth in Gel Electrolyte towards Advanced Wearable Zn-Ion Battery. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Qin, J.; Yang, S.; Shen, P.; Hu, Y.; Yang, K.; Luo, H.; Xu, J. A Mechanically Durable Hybrid Hydrogel Electrolyte Developed by Controllable Accelerated Polymerization Mechanism towards Reliable Aqueous Zinc-Ion Battery. Energy Storage Mater. 2023, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Yang, H.; Cui, W.; Fadillah, L.; Huang, T.; Xiong, Z.; Tang, C.; Kowalski, D.; Kitano, S.; Zhu, C.; et al. High Strength Hydrogels Enable Dendrite-Free Zn Metal Anodes and High-Capacity Zn-MnO2batteries via a Modified Mechanical Suppression Effect. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, L.; Guo, W.; Chang, C.; Wang, J.; Cong, Z.; Pu, X. High-Performance Dual-Ion Zn Batteries Enabled by a Polyzwitterionic Hydrogel Electrolyte with Regulated Anion/Cation Transport and Suppressed Zn Dendrite Growth. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Li, J.; Zhao, S.; Jiao, Y.; Chen, J.; Tan, Y.; Brett, D.J.L.; He, G.; Parkin, I.P. Investigation of a Biomass Hydrogel Electrolyte Naturally Stabilizing Cathodes for Zinc-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Meng, T.; Zheng, X.; Li, T.; Brozena, A.H.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Clifford, B.C.; Rao, J.; Hu, L. Nanocellulose-Carboxymethylcellulose Electrolyte for Stable, High-Rate Zinc-Ion Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Hong, H.; Yang, S.; Zhang, R.; Wang, X.; Jin, X.; Xiong, B.; Bai, S.; Zhi, C. Lean-Water Hydrogel Electrolyte for Zinc Ion Batteries. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Yuan, D.; Ponce de León, C.; Jiang, Z.; Xia, X.; Pan, J. Current Progress and Future Perspectives of Electrolytes for Rechargeable Aluminum-Ion Batteries. Energy Environ. Mater. 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, R.; Wu, H.; Jiang, Z.; Zheng, A.; Yu, H.; Chen, M. Flexible Hydrogel Compound of V2O5/GO/PVA for Enhancing Mechanical and Zinc Storage Performances. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, G.; Ye, L.; He, J.; Xu, W.; Hong, S.; Chen, W.; Li, M.C.; Liu, C.; Mei, C. High-Energy and Dendrite-Free Solid-State Zinc Metal Battery Enabled by a Dual-Network and Water-Confinement Hydrogel Electrolyte. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, R.; Hu, Y.; Wang, R.; Shen, J.; Mao, Y.; Wu, Q.; Wang, B. Achieving Highly Reversible Zn Anodes by Inhibiting the Activity of Free Water Molecules and Manipulating Zn Deposition in a Hydrogel Electrolyte. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Hu, J.; Wei, X.; Zhang, K.; Xiao, X.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Q.; Yu, J.; Zhou, G.; Xu, B. A Recyclable Biomass Electrolyte towards Green Zinc-Ion Batteries. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Qin, B.; Passerini, S. High-Voltage Operation of a V2O5 Cathode in a Concentrated Gel Polymer Electrolyte for High-Energy Aqueous Zinc Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Yao, Y.; Dai, L.; Jiao, M.; Ding, B.; Yu, Q.; Tang, J.; Liu, B. Sustainable and High-Performance Zn Dual-Ion Batteries with a Hydrogel-Based Water-in-Salt Electrolyte. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, K.; Cheng, X.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y.; Li, P.; Wang, B.; Peng, H. Polymers for Flexible Energy Storage Devices. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2023, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anupama Devi, V.K.; Shyam, R.; Palaniappan, A.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Oh, T.H.; Nathanael, A.J. Self-Healing Hydrogels: Preparation, Mechanism and Advancement in Biomedical Applications. Polymers (Basel). 2021, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Wan, F.; Bi, S.; Zhu, J.; Niu, Z.; Chen, J. A Self-Healing Integrated All-in-One Zinc-Ion Battery. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 2019, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, B.; Cheng, J. Multi-Healable, Mechanically Durable Double Cross-Linked Polyacrylamide Electrolyte Incorporating Hydrophobic Interactions for Dendrite-Free Flexible Zinc-Ion Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Long, J.; Shen, Z.; Jin, X.; Han, T.; Si, T.; Zhang, H. A Self-Healing Flexible Quasi-Solid Zinc-Ion Battery Using All-In-One Electrodes. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Cui, X.; Pan, Q. Self-Healable Hydrogel Electrolyte toward High-Performance and Reliable Quasi-Solid-State Zn-MnO2 Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Tang, Z.; Luo, L.; Yang, W.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Z.; Fan, X.H. Self-Healing Solid Polymer Electrolyte with High Ion Conductivity and Super Stretchability for All-Solid Zinc-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.S.; Yu, C.; Liu, Y.; Sun, K.; Shen, C.; Huang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, J.S.; et al. Self-Adapting and Self-Healing Hydrogel Interface with Fast Zn2+ Transport Kinetics for Highly Reversible Zn Anodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Han, T.; Lin, X.; Zhu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H. An Integrated Flexible Self-Healing Zn-Ion Battery Using Dendrite-Suppressible Hydrogel Electrolyte and Free-Standing Electrodes for Wearable Electronics. Nano Res. 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, A.; Hao, J.; Li, X.; Ling, J.; Yi, F.; Li, Q.; Shu, D. Soaking-Free and Self-Healing Hydrogel for Wearable Zinc-Ion Batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Hu, Y.; Ji, S.; Luo, H.; Zhai, C.; Yang, K. A Self-Healing Nanocomposite Hydrogel Electrolyte for Rechargeable Aqueous Zn-MnO2 Battery. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Cheng, R.; Sun, X.; Xu, H.; Li, Z.; Sun, F.; Zhan, Y.; Zou, J.; Laine, R.M. Organic Cathode Materials for Rechargeable Magnesium-Ion Batteries: Fundamentals, Recent Advances, and Approaches to Optimization. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Kilian, S.; Rashad, M. Uncovering Electrochemistries of Rechargeable Magnesium-Ion Batteries at Low and High Temperatures. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, H.; Jiang, C.; Tang, Y. Multi-Ion Strategies towards Emerging Rechargeable Batteries with High Performance. Energy Storage Mater. 2019, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Dou, Y.; Lian, R.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Y. Understanding Rechargeable Magnesium Ion Batteries via First-Principles Computations: A Comprehensive Review. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.; Kim, D.; Lee, M.; Nam, K.W. Challenges and Possibilities for Aqueous Battery Systems. Commun. Mater. 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deivanayagam, R.; Ingram, B.J.; Shahbazian-Yassar, R. Progress in Development of Electrolytes for Magnesium Batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2019, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ding, Y.; Sun, Y.; Ren, Y.; Yang, J.; Yin, B.; Li, H.; Zhang, S.; Ma, T. Emerging Rechargeable Aqueous Magnesium Ion Battery. Mater. Reports Energy 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Xu, X.; Qu, G.; Deng, J.; Zhu, Y.; Fang, C.; Fontaine, O.; Hiralal, P.; Zheng, J.; Zhou, H. An Aqueous Magnesium-Ion Battery Working at −50 °C Enabled by Modulating Electrolyte Structure. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Xia, W.; Liu, Q.; Hu, J.; Wei, T.; Ling, Y.; Liu, B.; et al. In-Situ Synthesis of Bi Nanospheres Anchored in 3D Interconnected Cellulose Nanocrystal Derived Carbon Aerogel as Anode for High-Performance Mg-Ion Batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziam, H.; Larhrib, B.; Hakim, C.; Sabi, N.; Ben Youcef, H.; Saadoune, I. Solid-State Electrolytes for beyond Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Ji, Z.; Feng, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Hu, M.; Fei, J.; Gan, W.; et al. A High-Performance Flexible Aqueous Al Ion Rechargeable Battery with Long Cycle Life. Energy Storage Mater. 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, P.; Ji, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Ling, W.; Liu, J.; Hu, M.; Zhi, C.; Huang, Y. Rechargeable Quasi-Solid-State Aqueous Hybrid Al3+/H+ Battery with 10,000 Ultralong Cycle Stability and Smart Switching Capability. Nano Res. 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T.; He, B.; Zhou, T.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xin, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Y.; Wei, L. Stretchable Fiber-Shaped Aqueous Aluminum Ion Batteries. EcoMat 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hydrogel Type | Source/Composition | Properties | Applications | Advantages | Challenges | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Hydrogels | Alginate, chitosan, cellulose | Biocompatibility, biodegradability, high gelation ability | Electrolytes, separators in batteries and supercapacitors | Renewable, environmentally friendly | Mechanical strength, scalability | [42] |

| Synthetic Hydrogels | Polyacrylamide (PAM), polyethylene oxide (PEO), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) | High water content, tunable mechanical properties, high ionic conductivity | Electrolytes, separators in batteries and supercapacitors | Customizable properties, high ionic conductivity | Environmental impact, mechanical robustness | [44] |

| Composite Hydrogels | Graphene oxide + polymer matrix, nanoparticles + polymer matrix | Enhanced mechanical properties, high electrical conductivity | Electrodes in batteries, supercapacitors | Enhanced properties, multifunctionality | Complexity in synthesis, cost | [44] |

| Carbon-based Hydrogels | Graphene, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) | High electrical conductivity, mechanical strength | Electrodes in batteries, supercapacitors | High electrical conductivity, mechanical strength | Scalability, cost | [45] |

| Conductive Polymer Hydrogels | Polyaniline, polypyrrole | High electrical conductivity, flexibility | Electrodes, sensors, supercapacitors | High electrical conductivity, flexibility | Stability, environmental impact | [46] |

| Metal-Organic Framework (MOF) Hydrogels | MOFs + polymer matrix | High porosity, tunable properties | Electrolytes, gas storage, sensors | High porosity, tunable properties | Synthesis complexity, cost | [47] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).