Submitted:

15 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Proposes a novel ACR mechanism that enhances YOLOv8-based object detection by incorporating contextual information surrounding insulator defects, improving classification accuracy and localization precision in complex scenarios.

- Designs an adaptive multi-scale context extraction strategy that dynamically selects context region sizes based on the object’s relative area, enabling better detection of small or partially occluded faults in power transmission insulators.

- Integrates a lightweight attention-based refinement network, including spatial and channel attention modules, which refines the bounding boxes and recalibrates confidence scores without significantly increasing computational cost.

- Conducts a comprehensive evaluation across 25 YOLO model variants (YOLOv8 through YOLOv12), demonstrating consistent improvements in mean Average Precision (mAP), particularly for lower-capacity models with limited baseline accuracy.

- Validates the approach using real-world UAV datasets containing high-resolution images of insulators under varying environmental and fault conditions, proving its robustness and practical applicability to real-time inspection in power systems.

2. Related Works

3. Methodology

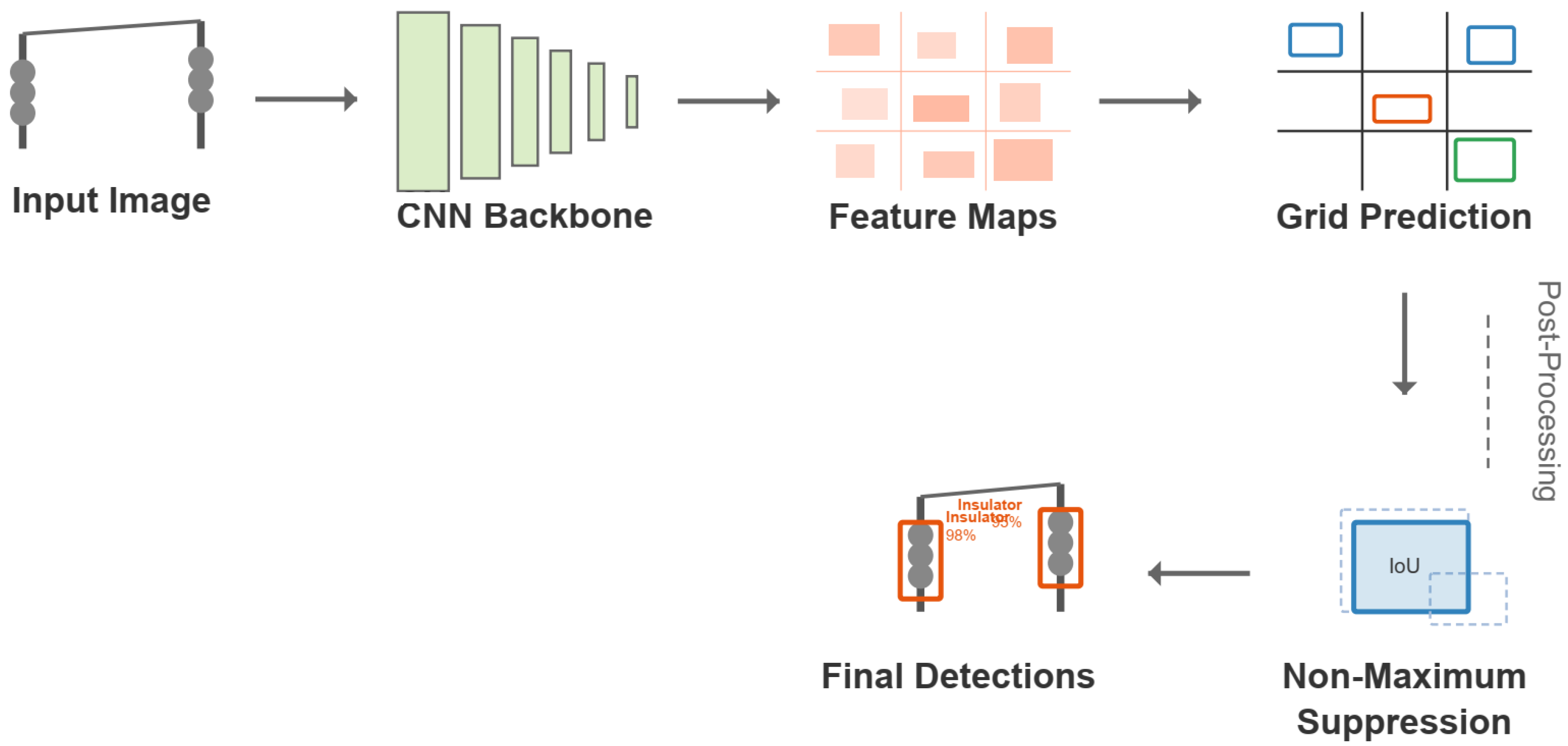

3.1. YOLO Detection Framework

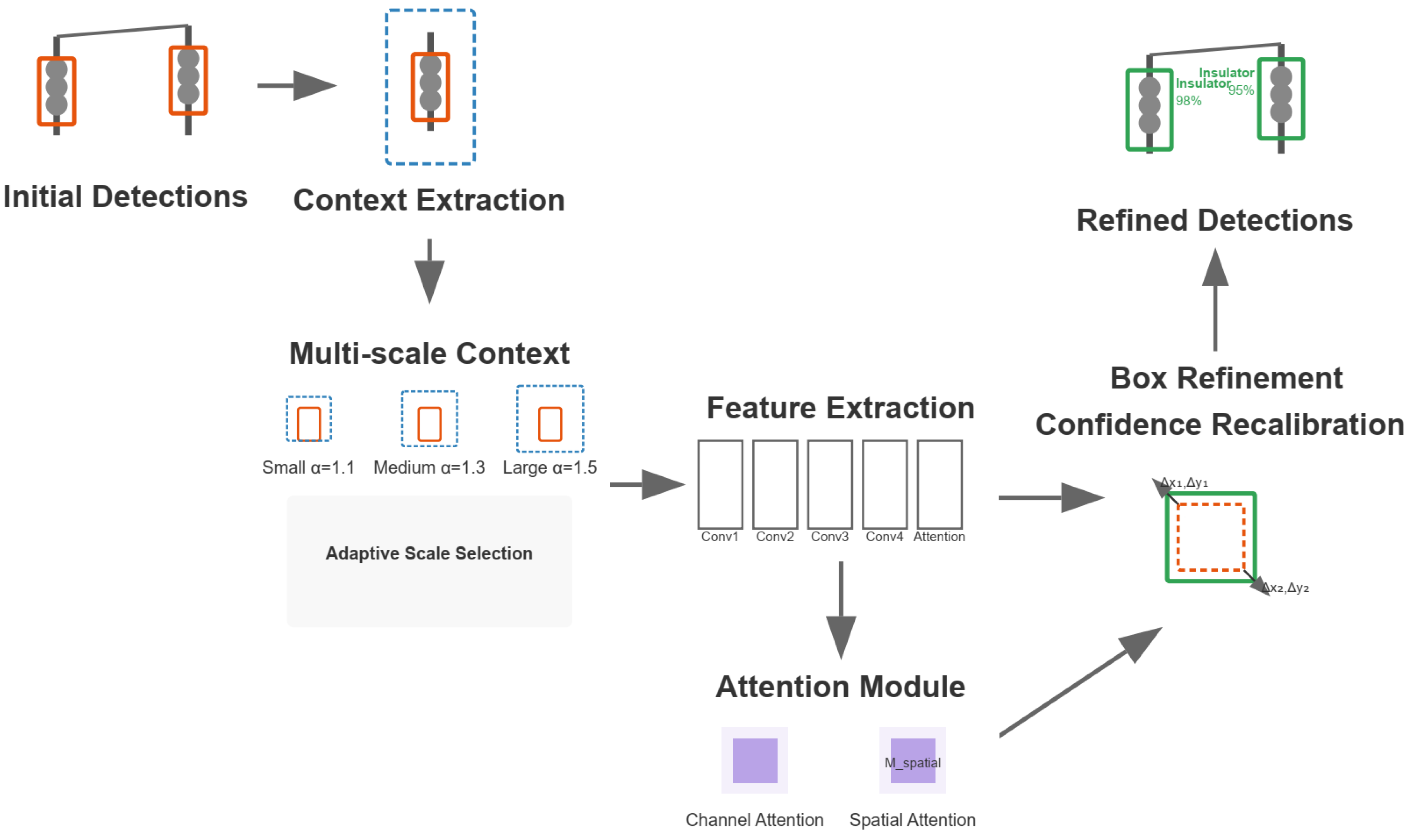

3.2. Adaptive Context Refinement

3.3. Context Extraction and Neural Architecture

3.4. Spatial Attention and Feature Fusion

3.5. Box Refinement and Confidence Recalibration

3.6. Training Methodology

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Performance Evaluation Metrics

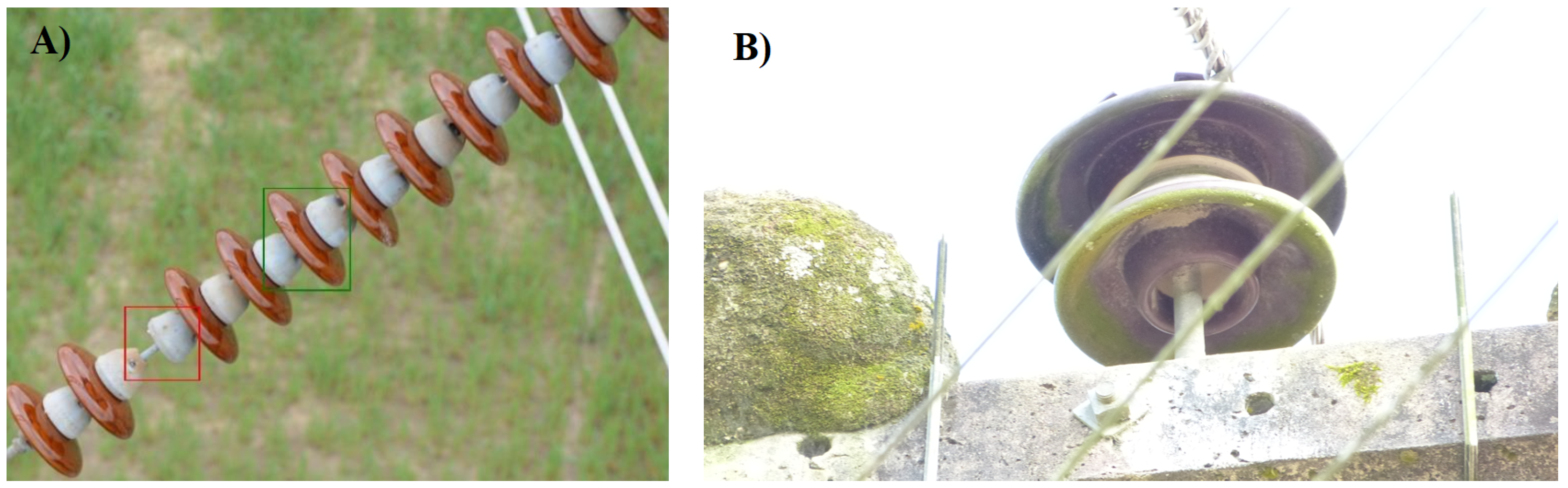

4.2. Dataset

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Training Methodology

5.2. Implementation Details

- 1.

- Data Configuration: A custom YAML configuration generator that creates the required dataset specification with appropriate paths and class definitions.

- 2.

-

Memory Management: Implementation of memory optimization techniques including:

- Dynamic garbage collection

- CUDA cache emptying between training runs

- Automatic mixed precision (AMP) to reduce memory footprint

- Minimal worker threads to reduce parallel processing overhead

- 3.

-

Adaptive Training: The framework includes fallback mechanisms to handle potential memory limitations:

- Automatic reduction of batch size and image resolution if out-of-memory errors occur

- Optional subset training on reduced dataset samples for preliminary model validation

- Device-agnostic implementation with CPU fallback capability

- 4.

-

Evaluation Metrics: The training process tracks multiple performance indicators including:

- Precision and recall for class-specific performance

- mAP at IoU thresholds of 0.5 (mAP@0.5) and 0.5:0.95 (mAP@0.5:0.95)

- F1-score for balanced evaluation of precision and recall

5.3. Experimental Framework

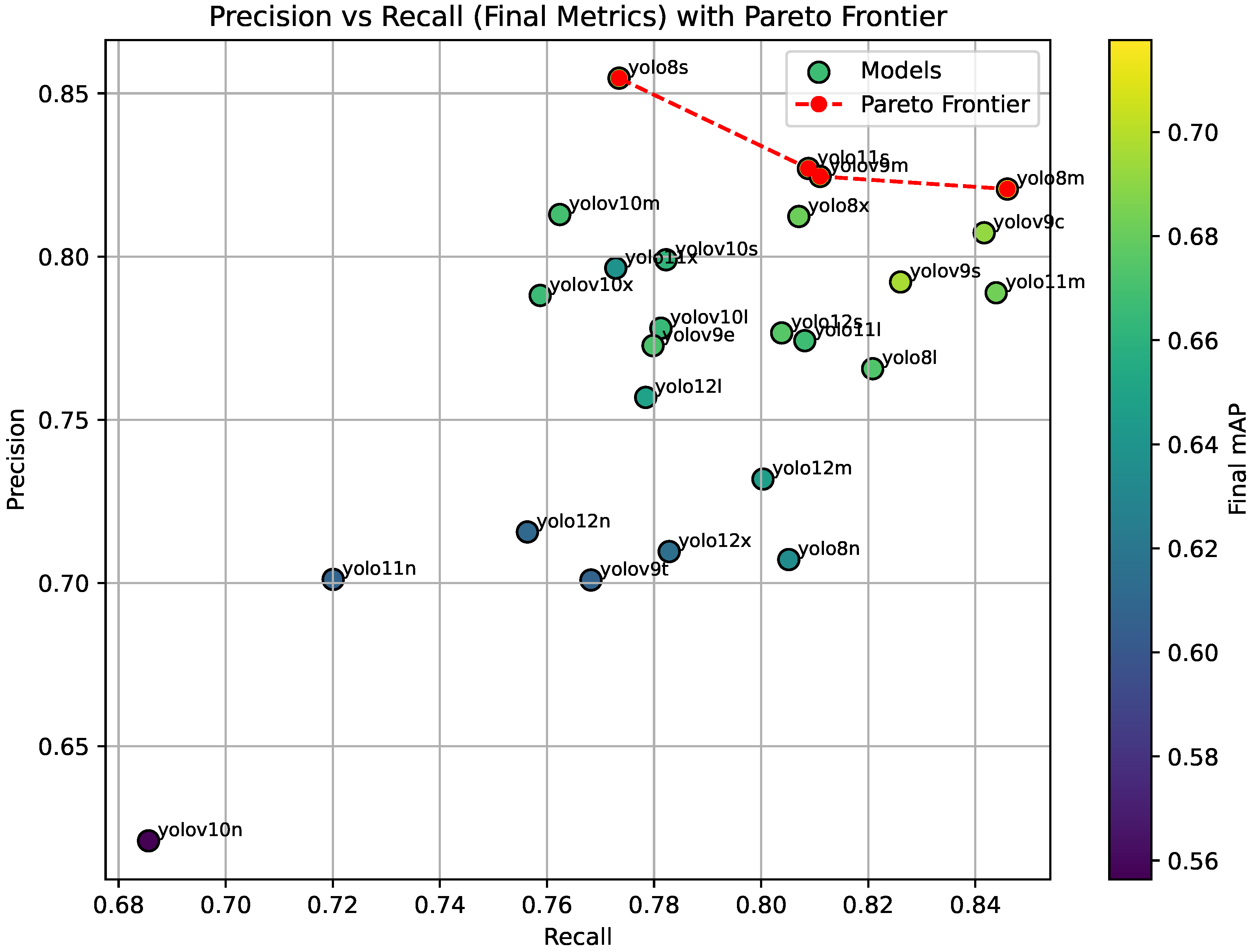

5.4. Baseline Analysis with YOLO Variants

5.5. Refinement Analysis and Cross-Generation Comparison

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, M.; Mohanta, J.; Sanyal, A. Inspection and identification of transmission line insulator breakdown based on deep learning using aerial images. Electric Power Systems Research 2022, 211, 108199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, A.; Sartori, A.; Stefenon, S.F.; Meyer, L.H.; Nied, A. Comparison of artificial intelligence techniques to failure prediction in contaminated insulators based on leakage current. Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems 2022, 42, 3285–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias Velásquez, R.M. Insulation failure caused by special pollution around industrial environments. Engineering Failure Analysis 2019, 102, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberironaghi, A.; Ren, J.; El-Gindy, M. Defect Detection Methods for Industrial Products Using Deep Learning Techniques: A Review. Algorithms 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seman, L.O.; Stefenon, S.F.; Mariani, V.C.; Coelho, L.S. Ensemble learning methods using the Hodrick–Prescott filter for fault forecasting in insulators of the electrical power grids. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2023, 152, 109269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefenon, S.F.; Oliveira, J.R.; Coelho, A.S.; Meyer, L.H. Diagnostic of insulators of conventional grid through LabVIEW analysis of FFT signal generated from ultrasound detector. IEEE Latin America Transactions 2017, 15, 884–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljalaud, F.; Kurdi, H.; Youcef-Toumi, K. Autonomous Multi-UAV Path Planning in Pipe Inspection Missions Based on Booby Behavior. Mathematics 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Zhou, W.; Wang, K.; Wang, J.; Wang, R.; Deng, H.; Liu, G. Defect detection of small cotter pins in electric power transmission system from UAV images using deep learning techniques. Electrical Engineering 2023, 105, 1251–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, M.P.; Stefenon, S.F.; Singh, G.; Matsuo, M.V.; Perez, F.L.; Leithardt, V.R.Q. Evaluation of visible contamination on power grid insulators using convolutional neural networks. Electrical Engineering 2023, 105, 3881–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Mao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, T.; Zeng, K.; Xie, H.; Wang, Y. Balancing Accuracy and Efficiency With a Multiscale Uncertainty-Aware Knowledge-Based Network for Transmission Line Inspection. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2025, 21, 2829–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrador Rivas, A.E.; Abrão, T. Faults in smart grid systems: Monitoring, detection and classification. Electric Power Systems Research 2020, 189, 106602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preduș, M.F.; Popescu, C.; Răduca, E.; Hațiegan, C. Study of the Accelerated Degradation of the Insulation of Power Cables under the Action of the Acid Environment. Energies 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, X.; Zhao, X. A insulator defect detection network based on improved YOLOv7 for UAV aerial images. Measurement 2025, 253, 117410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefenon, S.F.; Singh, G.; Souza, B.J.; Freire, R.Z.; Yow, K.C. Optimized hybrid YOLOu-Quasi-ProtoPNet for insulators classification. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution 2023, 17, 3501–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefenon, S.F.; Yow, K.C.; Nied, A.; Meyer, L.H. Classification of distribution power grid structures using inception v3 deep neural network. Electrical Engineering 2022, 104, 4557–4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas-Gutierres, L.F.; Maresch, K.; Morais, A.M.; Nunes, M.V.; Correa, C.H.; Martins, E.F.; Fontoura, H.C.; Schmidt, M.V.; Soares, S.N.; Cardoso, G.; et al. Framework for decision-making in preventive maintenance: Electric field analysis and partial discharge diagnosis of high-voltage insulators. Electric Power Systems Research 2024, 233, 110447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, U.; Rahman, M.; Islam, M.R.; Hossain, M.A.; Sheikh, M.R.I.; Hossain, M. Adversarial training-based robust model for transmission line’s insulator defect classification against cyber-attacks. Electric Power Systems Research 2025, 245, 111585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefenon, S.F.; Seman, L.O.; Pavan, B.A.; Ovejero, R.G.; Leithardt, V.R.Q. Optimal design of electrical power distribution grid spacers using finite element method. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution 2022, 16, 1865–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefenon, S.F.; Americo, J.P.; Meyer, L.H.; Grebogi, R.B.; Nied, A. Analysis of the electric field in porcelain pin-type insulators via finite elements software. IEEE Latin America Transactions 2018, 16, 2505–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Zhu, R.; Ge, L.; Cao, D.; Yang, Z. Mitigating Class Imbalance Issues in Electricity Theft Detection via a Sample-Weighted Loss. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2025, 21, 1754–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefenon, S.F.; Seman, L.O.; Sopelsa Neto, N.F.; Meyer, L.H.; Mariani, V.C.; Coelho, L.d.S. Group method of data handling using Christiano-Fitzgerald random walk filter for insulator fault prediction. Sensors 2023, 23, 6118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Q.; Kang, W.; Yang, X.; Wang, Q.; Huang, Q. Intelligent recognition and sustainable security protection strategies for abnormal behavior of power grid operation data based on multidimensional digital portrait and deep neural networks. Discover Artificial Intelligence 2025, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Qiu, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Miao, X.; Zhuang, S. Insulator Fault Detection in Aerial Images Based on Ensemble Learning With Multi-Level Perception. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 61797–61810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, G. IF-YOLO: An Efficient and Accurate Detection Algorithm for Insulator Faults in Transmission Lines. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 167388–167403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, B.J.; Stefenon, S.F.; Singh, G.; Freire, R.Z. Hybrid-YOLO for classification of insulators defects in transmission lines based on UAV. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2023, 148, 108982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Xu, M.; Cheng, X.; Zhao, Z. An Insulator in Transmission Lines Recognition and Fault Detection Model Based on Improved Faster RCNN. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2021, 70, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Xu, W.; Wang, Z.; Yu, S.; Zeng, P.; Ju, Z. Analysis on the Impact of Data Augmentation on Target Recognition for UAV-Based Transmission Line Inspection. Complexity 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Li, T.; Li, Q.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, M.; Wang, R.; Yuan, Q.; Liu, K.; Qin, L. Improved Algorithm for Insulator and Its Defect Detection Based on YOLOX. Sensors 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Qing, Y.; Wang, C.; Lan, T.; Yao, R. Detection of Insulator Defects With Improved ResNeSt and Region Proposal Network. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 184841–184850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuang, F.; Wei, S.; Li, Y.; Gu, X.; Lu, Z. Detail R-CNN: Insulator Detection Based on Detail Feature Enhancement and Metric Learning. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2023, 72, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, J.; Li, B. ARG-Mask RCNN: An Infrared Insulator Fault-Detection Network Based on Improved Mask RCNN. Sensors 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.; Zuo, C.; Wei, W. Detection and Evaluation Method of Transmission Line Defects Based on Deep Learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 38448–38458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; He, Z.; Shi, B.; Zhong, T. Research on Recognition Method of Electrical Components Based on YOLO V3. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 157818–157829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Yang, Z.; Xu, H.; Hu, G.; Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Lai, S.; Zeng, H. Search like an eagle: A cascaded model for insulator missing faults detection in aerial images. Energies 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Cortes, C.O. A Convolutional Neural Network for Detecting Faults in Power Distribution Networks along a Railway: A Case Study Using YOLO. Applied Artificial Intelligence 2021, 35, 2067–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Zhu, X.; Liao, C.; Shi, D.; Qu, W. Detection of Transmission Line Insulator Defects Based on an Improved Lightweight YOLOv4 Model. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liquan, Z.; Mengjun, Z.; Ying, C.; Yanfei, J. Fast Detection of Defective Insulator Based on Improved YOLOv5s. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Xin, M.; Liao, J.; Xie, Q. A Light-Weight Network for Small Insulator and Defect Detection Using UAV Imaging Based on Improved YOLOv5. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Wu, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Xu, W. Insulator-Defect Detection Algorithm Based on Improved YOLOv7. Sensors 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Zhang, W.; Wu, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, C. ID-YOLOv7: an efficient method for insulator defect detection in power distribution network. Frontiers in Neurorobotics 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wei, X.; Zhang, L.; Yu, L.; Chen, Y.; Tu, M. YOLO v7-ECA-PConv-NWD Detects Defective Insulators on Transmission Lines. Electronics (Switzerland) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Jiang, W.; Zou, D.; Weng, W.; Li, H. An Insulator Fault Diagnosis Method Based on Multi-Mechanism Optimization YOLOv8. Applied Sciences 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Chen, Y.; An, P.; Hong, H.; Hu, J.; Huang, T. UAV-YOLOv8: A Small-Object-Detection Model Based on Improved YOLOv8 for UAV Aerial Photography Scenarios. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Z.; He, Y.; Lin, S.; Yi, T.; Li, M. SnakeNet: An adaptive network for small object and complex background for insulator surface defect detection. Computers and Electrical Engineering 2024, 117, 109259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Qin, L.; Deng, X.; Liu, K. MFI-YOLO: Multi-Fault Insulator Detection Based on an Improved YOLOv8. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2024, 39, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, X.; Feng, L.; Zhai, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Q. MCI-GLA Plug-In Suitable for YOLO Series Models for Transmission Line Insulator Defect Detection. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2024, 73, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, H.; Lv, G.; Chen, J. A2MADA-YOLO: Attention Alignment Multiscale Adversarial Domain Adaptation YOLO for Insulator Defect Detection in Generalized Foggy Scenario. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2025, 74, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadykova, D.; Pernebayeva, D.; Bagheri, M.; James, A. IN-YOLO: Real-Time Detection of Outdoor High Voltage Insulators Using UAV Imaging. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2020, 35, 1599–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Chen, K.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, M. CACS-YOLO: A Lightweight Model for Insulator Defect Detection Based on Improved YOLOv8m. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2024, 73, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhu, C.; Wang, G. IL-YOLO: An Efficient Detection Algorithm for Insulator Defects in Complex Backgrounds of Transmission Lines. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 14532–14546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhu, C.; Wang, G. ID-YOLO: A Multimodule Optimized Algorithm for Insulator Defect Detection in Power Transmission Lines. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2025, 74, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Rao, Z.Q.; Ding, B.; Li, S.J. Research on Defect Detection Method of Railway Transmission Line Insulators Based on GC-YOLO. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 102635–102642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Lu, Y.; Gao, Q.; Li, X.; Yu, X.; Song, Y. LiteYOLO-ID: A Lightweight Object Detection Network for Insulator Defect Detection. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2024, 73, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Feng, D.; Zhang, Q.; Li, S. HRD-YOLOX Based Insulator Identification and Defect Detection Method for Transmission Lines. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 22649–22661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Liu, J.; Liu, J. DRR-YOLO: A Study of Small Target Multi-Modal Defect Detection for Multiple Types of Insulators Based on Large Convolution Kernel. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 26331–26344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Jiang, W. LA-YOLO: Bidirectional Adaptive Feature Fusion Approach for Small Object Detection of Insulator Self-Explosion Defects. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2024, 39, 3387–3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Mei, K.; Cao, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, G. LDDFSF-YOLO11: A Lightweight Insulator Defect Detection Method Focusing on Small-Sized Features. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 90273–90292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, B.; Cui, Y.; et al. Research on improved YOLOv8 algorithm for insulator defect detection. Journal of Real-Time Image Processing 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Miao, S.; Kang, R.; Cao, L.; Zhang, L.; Ren, Y. Insulator Defect Detection Algorithm Based on Improved YOLOv11n. Sensors 2025, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefenon, S.F.; Seman, L.O.; Singh, G.; Yow, K.C. Enhanced insulator fault detection using optimized ensemble of deep learning models based on weighted boxes fusion. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2025, 168, 110682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, D. Person re-identification based on improved attention mechanism and global pooling method. Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation 2023, 94, 103849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Stefenon, S.F.; Yow, K.C. Interpretable visual transmission lines inspections using pseudo-prototypical part network. Machine Vision and Applications 2023, 34, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Hou, S.; Yang, F.; Li, Z. Transmission Lines Insulator State Detection Method Based on Deep Learning. Applied Sciences 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefenon, S.F.; Cristoforetti, M.; Cimatti, A. Towards Automatic Digitalization of Railway Engineering Schematics. In Proceedings of the AIxIA 2023 – Advances in Artificial Intelligence, Rome, Italy, 2023; Vol. 22; pp. 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Li, B.; Chen, Y.; Qu, S.; Cheng, T.; Zhou, J. Precision in Aerial Surveillance: Integrating YOLOv8 With PConv and CoT for Accurate Insulator Defect Detection. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 49062–49075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahy, S.; Karmakar, S. Real-Time Condition Monitoring of Transmission Line Insulators Using the YOLO Object Detection Model With a UAV. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2024, 73, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefenon, S.F.; Seman, L.O.; Klaar, A.C.R.; Ovejero, R.G.; Leithardt, V.R.Q. Hypertuned-YOLO for interpretable distribution power grid fault location based on EigenCAM. Ain Shams Engineering Journal 2024, 15, 102722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefenon, S.F.; Cristoforetti, M.; Cimatti, A. Automatic digitalization of railway interlocking systems engineering drawings based on hybrid machine learning methods. Expert Systems with Applications 2025, 281, 127532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.; Kulkarni, P. Insulator Defect Detection. https://ieee-dataport.org/competitions/insulator-defect-detection, 2021. [Accessed ]. 8 May.

- Stefenon, S.F. Inspection of Electrical Power Distribution Grid. https://github.com/SFStefenon/InspectionDataSet, 2023. [Accessed ]. 8 May.

| Model | Final mAP | Final Precision | Final Recall |

|---|---|---|---|

| yolo8l | 0.673160 | 0.765651 | 0.820825 |

| yolo8m | 0.717706 | 0.820685 | 0.845983 |

| yolo8n | 0.634158 | 0.707193 | 0.805160 |

| yolo8s | 0.690742 | 0.854654 | 0.773468 |

| yolo8x | 0.681275 | 0.812279 | 0.807037 |

| yolov9c | 0.691740 | 0.807288 | 0.841653 |

| yolov9e | 0.671942 | 0.772708 | 0.779811 |

| yolov9m | 0.695113 | 0.824548 | 0.811013 |

| yolov9s | 0.696710 | 0.792208 | 0.826039 |

| yolov9t | 0.606963 | 0.700928 | 0.768216 |

| yolov10l | 0.664870 | 0.778065 | 0.781277 |

| yolov10m | 0.669379 | 0.812874 | 0.762396 |

| yolov10n | 0.556448 | 0.621034 | 0.685595 |

| yolov10s | 0.662223 | 0.799026 | 0.782245 |

| yolov10x | 0.666366 | 0.788095 | 0.758736 |

| yolo11l | 0.666793 | 0.774235 | 0.808157 |

| yolo11m | 0.682998 | 0.788911 | 0.843897 |

| yolo11n | 0.607671 | 0.701113 | 0.720074 |

| yolo11s | 0.686071 | 0.826978 | 0.808819 |

| yolo11x | 0.637785 | 0.796459 | 0.772851 |

| yolo12l | 0.649314 | 0.756868 | 0.778446 |

| yolo12m | 0.646290 | 0.731834 | 0.800345 |

| yolo12n | 0.610553 | 0.715652 | 0.756351 |

| yolo12s | 0.675353 | 0.776610 | 0.803838 |

| yolo12x | 0.614661 | 0.709647 | 0.782829 |

| Model | Original mAP | Refined mAP | mAP | % Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| yolo8l | 0.673160 | 0.703000 | 0.029840 | 4.43 |

| yolo8m | 0.717706 | 0.723700 | 0.005994 | 0.84 |

| yolo8n | 0.634158 | 0.687200 | 0.053042 | 8.36 |

| yolo8s | 0.690742 | 0.714600 | 0.023858 | 3.45 |

| yolo8x | 0.681275 | 0.702600 | 0.021325 | 3.13 |

| yolov9c | 0.691740 | 0.724500 | 0.032760 | 4.74 |

| yolov9e | 0.671942 | 0.702400 | 0.030458 | 4.53 |

| yolov9m | 0.695113 | 0.724400 | 0.029287 | 4.21 |

| yolov9s | 0.696710 | 0.722500 | 0.025790 | 3.70 |

| yolov9t | 0.606963 | 0.673300 | 0.066337 | 10.93 |

| yolov10l | 0.664870 | 0.745300 | 0.080430 | 12.10 |

| yolov10m | 0.669379 | 0.723600 | 0.054221 | 8.10 |

| yolov10n | 0.556448 | 0.683800 | 0.127352 | 22.89 |

| yolov10s | 0.662223 | 0.730800 | 0.068577 | 10.36 |

| yolov10x | 0.666366 | 0.732200 | 0.065834 | 9.88 |

| yolo11l | 0.666793 | 0.709700 | 0.042907 | 6.43 |

| yolo11m | 0.682998 | 0.700700 | 0.017702 | 2.59 |

| yolo11n | 0.607671 | 0.651200 | 0.043529 | 7.16 |

| yolo11s | 0.686071 | 0.692700 | 0.006629 | 0.97 |

| yolo11x | 0.637785 | 0.701500 | 0.063715 | 9.99 |

| yolo12l | 0.649314 | 0.698100 | 0.048786 | 7.51 |

| yolo12m | 0.646290 | 0.706700 | 0.060410 | 9.35 |

| yolo12n | 0.610553 | 0.671000 | 0.060447 | 9.90 |

| yolo12s | 0.675353 | 0.705400 | 0.030047 | 4.45 |

| yolo12x | 0.614661 | 0.688200 | 0.073539 | 11.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).