1. Introduction: The Digital Vanguard: Transforming the Operating Theatre

Digital technologies are converging in the present surgical wave, radically changing every step of the surgical process—from preparation to recovery. This technological convergence is producing a surgical scene that is more data-rich and integrated than ever before.

Robotics and Intelligent Systems: Originally a gimmick, robotic-assisted surgery is now a developing discipline. Offering doctors improved dexterity, tremor reduction, and better eyesight via high-definition 3D imaging (Boal et al., 2024; Fong et al., 2024; Hussain et al., 2025), systems like the da Vinci platform have been utilized in millions of procedures. Force-feedback technology included in the newest generations of these robots, such as the da Vinci 5, enables surgeons to “feel” the tissue they are working on—a critical step toward reproducing the tactile sensation of open surgery (Abdelwahab et al., 2024). The IDEAL Framework evaluates new surgical technologies, especially minimally invasive surgery. It includes four stages: Idea (concept), Development/Exploration (testing), Assessment (effectiveness and safety), and Surveillance (long-term monitoring). This ensures robotic surgical platforms are tested and validated before clinical use, enhancing patient safety and informed decision-making among surgeons(

Figure 1 (c.f., Boal et al., 2024).

The da Vinci 4th generation robots are advanced surgical systems used in minimally invasive surgeries(See

Figure 2 (c.f., Boal et al., 2024)), allowing surgeons to perform complex procedures with greater precision and control. These robots feature enhanced technology, such as improved imaging and instrument capabilities, which help in reducing recovery times and minimizing patient trauma. In the context of the review article, these robots are part of the evaluation of current robotic platforms, assessing their effectiveness and safety through the IDEAL Framework.

KANDUO Robot

® Surgical System, developed by Suzhuo Kangduo Robot Co., Ltd., assists minimally invasive surgeries (

Figure 3, c.f.,(Boal et al., 2024)). It enhances surgical precision and reduces recovery times through smaller incisions. The review evaluates robotic surgical systems, including KANDUO, for effectiveness and safety based on evaluation frameworks.

Hinotori Surgical Robot(see

Figure 4 (c.f., Togami et al., 2023)), developed by Medicaroid Corporation, assists surgeons in minimally invasive surgeries, enhancing precision and control, thus improving safety and potentially reducing recovery times. It is evaluated using the IDEAL Framework to ensure safety and effectiveness before widespread use.

The WEGO MicroHand S Surgical Robot System is a type of robotic technology designed for minimally invasive surgeries(

Figure 5 (c.f., Marchegiani et al., 2023, which means it allows surgeons to perform operations through small incisions rather than large openings. This system is part of a growing trend in surgical robotics that aims to improve precision and reduce recovery times for patients.

The Revo-I system is a robotic surgical platform developed by Meerecompany Inc. that is designed to assist surgeons in performing minimally invasive surgeries, as depicted in

Figure 6 (c.f., ., Boal et al., 2024). This system aims to improve precision and reduce recovery time for patients by allowing surgeries to be done through smaller incisions. The evaluation of the Revo-I system, like other robotic platforms, follows the IDEAL Framework to ensure it is safe and effective before widespread use in hospitals.

Shurui Technology Co., Ltd., based in Beijing, develops robotic surgical systems for minimally invasive surgery, allowing smaller incisions and faster recovery, as illustrated by

Figure 7 (c.f., Boal et al., 2024). The review article evaluates Shurui’s platforms for effectiveness and safety using the IDEAL Framework, assessing new surgical technologies at various development stages.

Beyond seasoned veterans, a fresh generation of more specialized and affordable robots is coming into being. Systems like the TMINI for knee surgery and the Symani for microsurgery are making robotic assistance available for a wider variety of procedures (Śliwczyński et al., 2024). This development opens the path for tele-surgery, which allows a specialist to work on a patient from hundreds or even many thousands of miles away—a talent with great promise for giving care to far-off and underprivileged areas (Sarin et al., 2024).

2. The AI Co-Pilot and AR Navigator

In the operating room, artificial intelligence (AI) is fast becoming an essential co-pilot. Medical images such CT and MRI scans can be examined by artificial intelligence algorithms to produce patient-specific 3D models for pre-operative planning that aids surgeons in predicting anatomical variances and possible complications (Kumar et al., 2023). Real-time decision assistance from artificial intelligence during the treatment helps, for instance by highlighting essential structures or analyzing tissue to discriminate between cancerous and healthy cells (Gayet et al., 2024). Operating as a complex navigational system, Augmented Reality (AR) works in harmony with artificial intelligence. AR combines 3D models and key data onto the surgeon’s view of the patient whether via a headset or a surgical microscope. This gives the surgeon “x-ray vision,” which allows them to see the underlying anatomy—like blood vessels and nerves—as if they were transparent (Jin et al., 2021). The flowchart(

Figure 8 (c.f., Jin et al., 2021 )) illustrates how a system of telestration mentoring works by showing the steps involved in video sharing and annotation during surgical training or procedures. Telestration mentoring allows experienced surgeons to provide real-time guidance to trainees by overlaying notes or drawings on video feeds, enhancing the learning experience. This method helps improve surgical skills by allowing for immediate feedback and clarification during the procedure.

In

Figure 9 (c.f., Jin et al., 2021)) (Jarc and colleagues created proprietary 3D mentoring software. Remote mentors, using standard video game controllers, may overlay 3D pointers (A), 3D hands (B), and 3-dimensional (3D) tools (C) on the surgery field videostream, which was then displayed to the trainer.

Figure 10 (c.f., Jin et al., 2021 ) describes the use of 3D models in surgery, specifically focusing on cranial anatomy. These models help surgeons visualize and understand the complex structures of the skull and brain before performing an operation. By mapping the coordinates of the surgical area to the 3D model, surgeons can better plan and navigate the procedure, leading to improved outcomes and reduced risks during surgery.

This innovation is especially important in improving accuracy in sensitive operations such neurosurgery and in avoiding accidental damage to components like the bile duct throughout gallbladder surgery (Pilavaki et al., 2023; Di Ieva, 2024).

3. Minimally Invasive and Non-Invasive Horizons

The tendency to lessen patient trauma keeps pushing the limits of minimum invasive surgery (MIS). Less pain, less scarring, and faster recovery times result from more procedures carried out via single, small incisions or even natural openings (Cummings et al., 2025).

Figure 11 (c.f., Cummings et al., 2025) refers to a standard method used to identify and record the presence of lesions, which are abnormal growths or areas of tissue damage, either on the mucosal surface (like the lining of organs) or just beneath it (submucosal). It emphasizes the importance of non-invasive techniques, meaning methods that do not require surgery or significant physical intrusion, for screening potential pre-cancerous conditions. This approach is crucial for early detection and diagnosis, helping to improve patient outcomes in surgical practices.

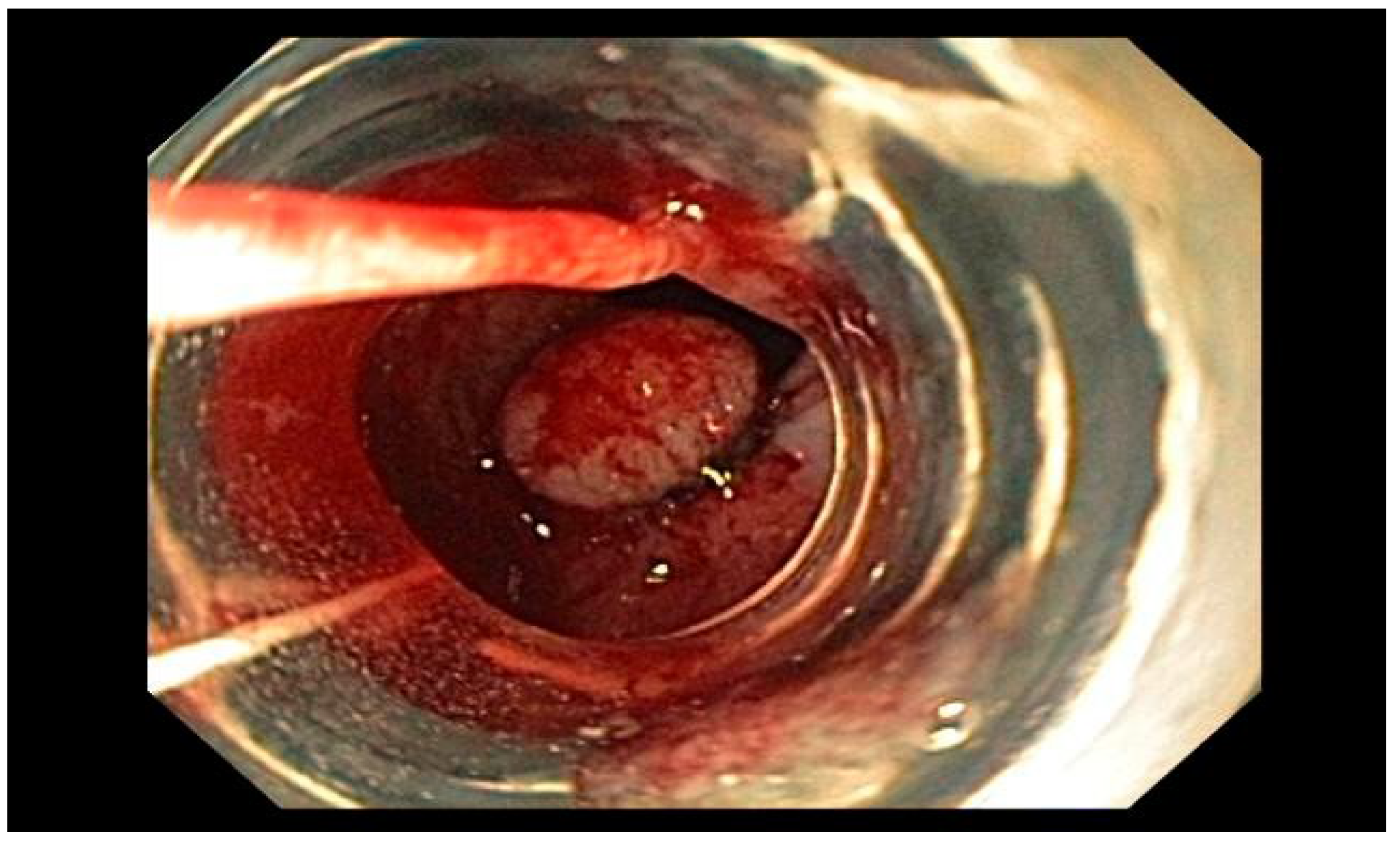

Visible mucosal lesions in the Barrett’s segment, which can include conditions like high-grade dysplasia and early-stage adenocarcinomas (T1a and T1b), can be treated using endoscopic resection techniques. One common method is called endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), which can be done using techniques like Cap-assisted EMR or multiband mucosectomy. The main goal of these procedures is to evaluate how deeply the cancer has invaded the tissue, which helps in determining the appropriate treatment, as in

Figure 12 (c.f., Cummings et al., 2025).

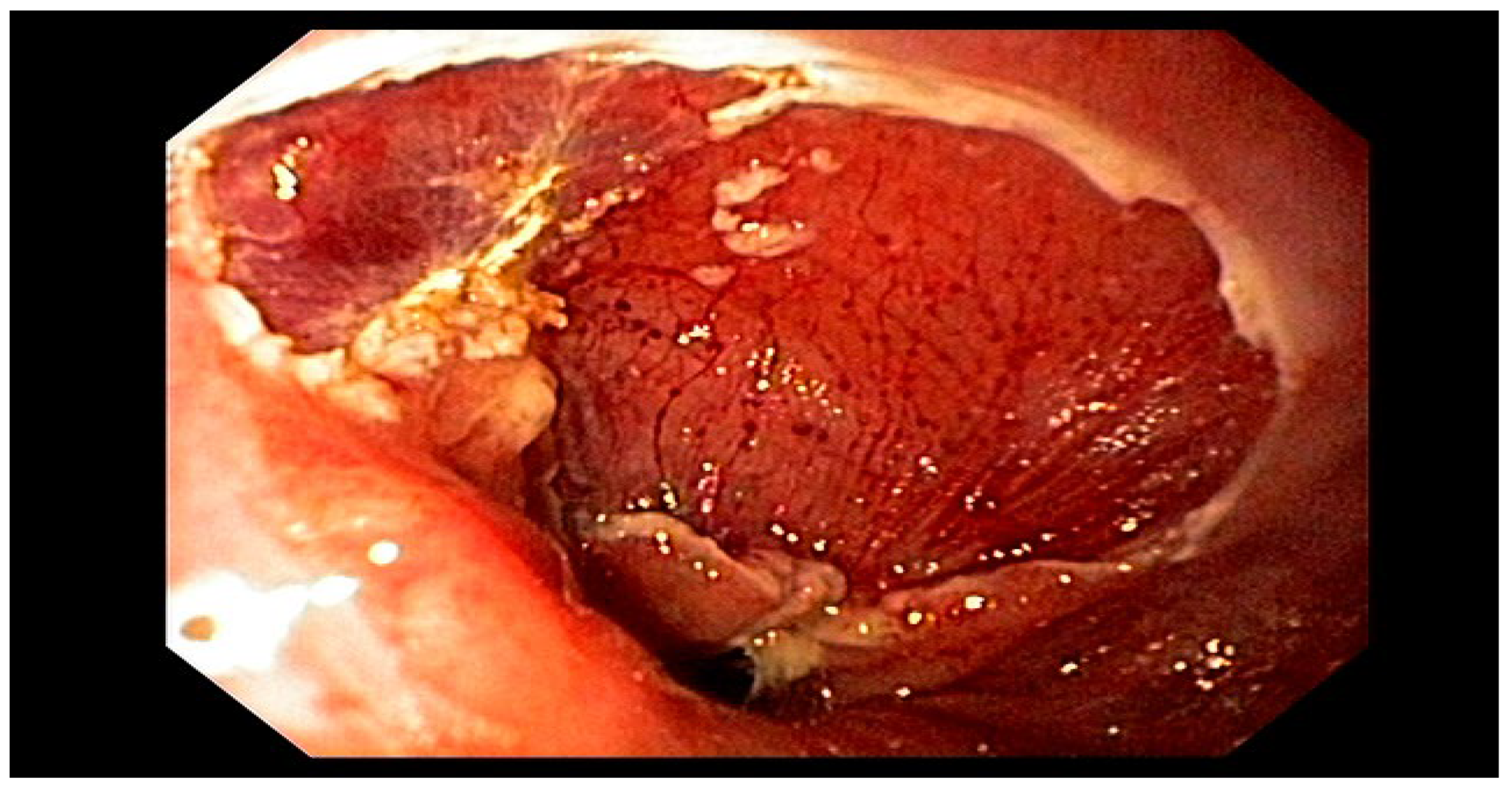

EMR and ESD are procedures to remove abnormal esophageal tissue, especially in Barrett’s esophagus patients. Their main goal is accurate cancer staging, but they may also cure the disease if margins are negative. Studies show staging can change for 20-30% of patients, impacting cancer classification, as in

Figure 13 (Cummings et al., 2025).

From cardiac valve replacements to gastrointestinal operations, sophisticated endoscopes and catheter-based instruments enable surgeons to execute difficult procedures without the need for huge, open incisions (Markan et al., 2025). Looking ahead, technology like high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) offers a step toward totally non-invasive treatments whereby damaged tissue might be eliminated deep within the body without a single cut (Vuille-dit-Bille, 2020).

4. A New Geometry of Healing: Fractal Geometric Surgery

Fractal geometry presents an innovative approach to grasp and engage with the biological structures themselves, while robotics and artificial intelligence improve current methods. Objects with fractal patterns—that is, self-similarity at various sizes— abound in the human body. Though fractal mathematics (Mageed & Bhat, 2022 ; Mageed & Mohamed, 2023; Mageed, 2023; Mageed, 2024 a-h; Mageed & Li, 2025a; Mageed & Li, 2025b; Mageed, 2025a; Mageed, 2025b; Nayak & Mishra, 2023) deftly models them, the branching networks of blood vessels, the complicated folding of the cortex of the brain, the air channels of the lungs, and the ducts of the kidneys challenge conventional Euclidean geometry description.

Fractal analysis has already shown its worth as a diagnostic tool. A strong biomarker is the “fractal dimension” of a tumor’s vascular network or boundary on an MRI or histology slide—a non-integer number quantifying complexity. A higher fractal dimension suggests more irregular, sophisticated, and chaotic patterns—which frequently correlate with malignancy and aggressiveness (Baish and Jain, 2000; Gazit et al. , 1997).

This enables a quantitative, objective evaluation of features pathologists have long described qualitatively. Beyond merely observation, the emerging idea of Fractal Geometric Surgery aims to enable active intervention. The idea is to create surgical approaches honoring the innate fractal logic of the body. A surgeon seeks to remove malignant tissue while conserving as much normal, functional tissue as possible when resecting a liver or lung tumor, for example. Planning a resection along fractal lines rather than simple straight lines could theoretically maximize organ preservation and function given the fractal branching pattern of the blood supply and airways in these organs (Szasz, 2021).

Although the design of a “ fractal Scalpel” is still in the theoretical phase, the ideas are guiding the creation of smart surgical systems. Following paths that cause the least disturbance to the fractal vascular tree supporting the surrounding healthy tissue, an AI-guided laser or robotic tool could be set to ablate a tumor. In oncology, where the line between curative resection and severe organ damage is sometimes extremely small (Lookian et al. , 2022; Di leva, 2024), this method may be transforming.

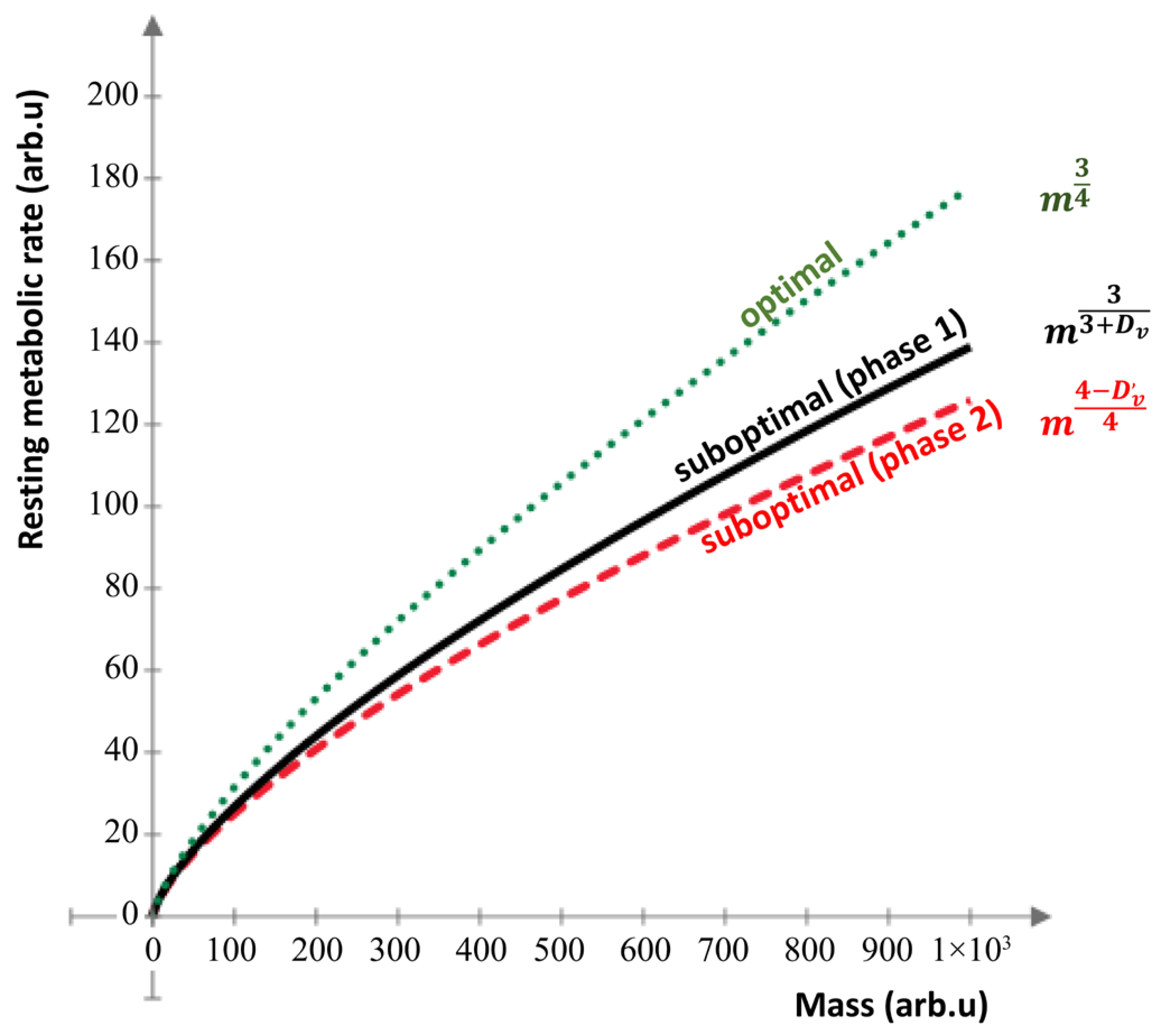

In (Szasz, 2021), the author discussed how the growth of cancerous tumors affects their energy needs and blood vessel structures. The “volume dimension” refers to how the tumor’s energy demand is ideally four-dimensional, but the actual conditions are not optimal, leading to lower efficiency in energy transport. By measuring the fractal dimension of the tumor’s blood vessels, the author calculates scaling exponents that indicate how well the tumor can meet its energy needs; these exponents are lower than optimal, showing that the tumor struggles to maximize its growth potential, as visualized by

Figure 14 (Szasz, 2021).

The measurements of vascular fractal dimensions in tumors indicate that the scaling exponent(Szasz, 2021), which ideally should be , is often lower due to the conditions affecting tumor growth and blood vessel development. For instance(Szasz, 2021), in some cases, the scaling exponent was found to be around 0.64 or 0.68, which is closer to the conventional value of , suggesting that tumors adapt their blood supply to optimize energy use under limited nutrient conditions. Additionally(Szasz, 2021), various cancer treatments can alter the vascular structure, impacting the fractal dimensions and the efficiency of energy supply in tumors, making fractal analysis a useful tool for evaluating treatment effectiveness.

The summary of the structure of calculation in this context refers to two main components: biophysical considerations and mathematical descriptions(Szasz, 2021). The biophysical considerations involve understanding how the physical properties of tumors(Szasz, 2021), like their blood supply and growth patterns, affect their metabolism. The mathematical description provides a way to quantify these relationships using equations and models(Szasz, 2021), helping researchers analyze how cancerous tissues optimize their energy intake based on their vascular structure and nutrient demands.

Figure 15.

The Computation Structure Overview.

Figure 15.

The Computation Structure Overview.

5. Overcoming the Challenges: Open Challenges on the Path to the Future

The journey towards this technologically advanced surgical future is fraught with significant challenges that must be addressed to ensure its benefits are realized safely, equitably, and effectively.

5.1. Economic and Accessibility Barriers

Cost is the current biggest barrier. Millions of dollars are invested in robotic surgical systems, with significant continuing expenses for upkeep and proprietary instruments (Chatterjee et al. , 2024; Oslock et al., 2024). This high price tag restricts their accessibility to well-financed institutions in affluent countries, therefore exacerbating disparities in healthcare access and threatening to broaden the divide in global health equity (Sherif et al. , 2023).

The Human Factor: Training and Skill Evolution

Incorporating these new technologies calls for a paradigm change in surgical training. Becoming competent with robotic systems and AI-powered tools calls for specialized, rigorous training programs (Collins et al. , 2022). Simulators and virtual reality systems are becoming very important, yet a steep learning curve persists. Moreover, the possible deterioration of conventional open surgical expertise is a valid worry. Less ready to manage circumstances when the technology fails or a conversion to an open surgery is required (Fairag et al. , 2024), a generation of surgeons trained primarily on robotic platforms might be less prepared.

5.2. Ethical and Legal Quagmires

Rising autonomy of surgical systems brings up severe legal and moral issues. Who is responsible should an artificial intelligence algorithm give erroneous advice or a surgical robot fails, hence harming a patient? Is it the surgeon employing the equipment, the hospital buying it, or the company making it? (Vashishts et al. , 2024; Mengxuan, 2023). Setting distinct lines of responsibility is a difficult endeavor that present legal systems are ill-suited to address (Sumathi et al., 2023).

Furthermore, surgical artificial intelligence is prone to the same prejudices that plague other artificial intelligence systems. Should algorithms be taught using information from a particular demographic, their accuracy may be lower for other groups, therefore worsening healthcare inequities (Altshuler , 2025). Another important consideration is guaranteeing data privacy and security as these strongly linked systems manage enormous volumes of sensitive patient information and so become possible cyber-attack targets (Elendu et al. , 2023).

Integration and Interoperability

Equipment from many different makers fills the contemporary operating room. Making sure these different systems may interact easily is a significant technical issue. Incompatibility might cause inefficiencies and possibly safety hazards. Though a “smart operating room” where the surgical robot, imaging systems, patient monitors, and electronic health records are all part of an integrated network, the vision of such a facility is still evolving (Vuille-dit-Bille, 2020; Van der Merwe & Casselman, 2023).

6. Conclusion

A rush of creativity is redefining the terrain of surgery. Artificial intelligence is supplementing the surgeon’s mind, robotic systems are extending his hands, and augmented reality is improving his sight. These next-generation instruments are more accurate, less intrusive, and more successful. Emerging ideas like fractal geometric surgery point toward a significantly more revolutionary future in which therapies are created in tune with the body’s own intricate biological structure. Still, the way ahead is not a straight path of development.

The great price of these technologies, the deep ethical issues they present, and the practical difficulties of integration and training are major obstacles that must be carefully and actively tackled. The future of surgery will be about developing a strong synergy between human surgeons and machines rather than about replacing them. Assuring that these amazing breakthroughs become a new age of safer, more efficient, and more accessible surgical treatment for everyone will call a multi-disciplinary effort from ethicists, engineers, data scientists, and clinicians.

References

- Abdelwahab, S.I.; Taha, M.M.E.; Farasani, A.; Jerah, A.A.; Abdullah, S.M.; Aljahdali, I.A. . & Hassan, W. Robotic surgery: bibliometric analysis, continental distribution, and co-words analysis from 2001 to 2023. Journal of Robotic Surgery 2024, 18, 335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

-

Applied Swarm Intelligence; Altshuler, Y., Ed.; CRC Press, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Boal, M.; Di Girasole, C.G.; Tesfai, F.; Morrison, T.E.M.; Higgs, S.; Ahmad, J.; Arezzo, A.; Francis, N. Evaluation status of current and emerging minimally invasive robotic surgical platforms. Surg. Endosc. 2023, 38, 554–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S.; Das, S.; Ganguly, K.; Mandal, D. Advancements in robotic surgery: innovations, challenges and future prospects. J. Robot. Surg. 2024, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, J.W.; Marcus, H.J.; Ghazi, A.; Sridhar, A.; Hashimoto, D.; Hager, G.; Arezzo, A.; Jannin, P.; Maier-Hein, L.; Marz, K.; et al. Ethical implications of AI in robotic surgical training: A Delphi consensus statement. Eur. Urol. Focus 2022, 8, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, D.; Wong, J.; Palm, R.; Hoffe, S.; Almhanna, K.; Vignesh, S. Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Staging and Multimodal Therapy of Esophageal and Gastric Tumors. Cancers 2021, 13, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Ieva, A. Computational fractal-based analysis of MR susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) in neuro-oncology and neurotraumatology. In The Fractal Geometry of the Brain; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2024; pp. 445–468. [Google Scholar]

- Elendu, C.; Amaechi, D.C.M.; Elendu, T.C.B.; Jingwa, K.A.M.; Okoye, O.K.M.; Okah, M.M.J.; Ladele, J.A.M.; Farah, A.H.; Alimi, H.A.M. Ethical implications of AI and robotics in healthcare: A review. Medicine 2023, 102, e36671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairag, M.; Almahdi, R.H.; Siddiqi, A.A.; Alharthi, F.K.; Alqurashi, B.S.; Alzahrani, N.G. . & Alshehri Sr, R. Robotic revolution in surgery: diverse applications across specialties and future prospects review article. Cureus 2024, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, Y.; Erhunmwunsee, L.; Pigazzi, A.; Podolsky, D.; Portenier, D.D. Robotic General Surgery; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gayet, B.; de Trogoff, E.; Osdoit, A. The Evolution of Minimally Invasive Robotic Surgery: Addressing Limitations and Forging Ahead? In Artificial Intelligence and the Perspective of Autonomous Surgery (pp. 119–137); Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M.; Jaffar-Karballai, M.; Kayali, F.; Jubouri, M.; Surkhi, A.O.; Bashir, M.; Murtada, A. How robotic platforms are revolutionizing colorectal surgery techniques: a comparative review. Expert Rev. Med Devices 2025, 22, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, M.L.; Brown, M.M.; Patwa, D.; Nirmalan, A.; Edwards, P.A. Telemedicine, telementoring, and telesurgery for surgical practices. Current problems in surgery 2021, 58, 100986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Immersive virtual and augmented reality in healthcare: an IoT and blockchain perspective; Kumar, R., Jain, V., Han, G.T.W., Touzene, A., Eds.; CRC Press, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lookian, P.P.; Chen, E.X.; Elhers, L.D.; Ellis, D.G.; Juneau, P.; Wagoner, J.; Aizenberg, M.R. The Association of Fractal Dimension with Vascularity and Clinical Outcomes in Glioblastoma. World Neurosurg. 2022, 166, e44–e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mageed, I.A.; Bhat, A.H. Generalized Z-Entropy (Gze) and fractal dimensions. Appl. Math. 2022, 16, 829–834. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I.A.; Mohamed, M. (2023). Chromatin can speak Fractals: A review.

- Mageed, I.A. (2023a, November). Fractal Dimension (Df) of Ismail’s Fourth Entropy (with Fractal Applications to Algorithms, Haptics, and Transportation. In 2023 international conference on computer and applications (ICCA) (pp. 1–6). IEEE.

- Mageed, I.A. The Fractal Dimension Theory of Ismail’s Third Entropy with Fractal Applications to CubeSat Technologies and Education. Complexity Analysis and Applications 2024, 1, 66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I.A. (2024b). Fractal Dimension of the Generalized Z-Entropy of The Rényian Formalism of Stable Queue with Some Potential Applications of Fractal Dimension to Big Data Analytics.

- Mageed, I.A. Fractal Dimension (Df) Theory of Ismail’s Entropy (IE) with Potential Df Applications to Structural Engineering. J. Intell. Commun. 2024, 3, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. A Theory of Everything: When Information Geometry Meets the Generalized Brownian Motion and the Einsteinian Relativity. J Sen Net Data Comm 2024, 4, 01–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I.A. The Generalized Z-Entropy’s Fractal Dimension within the Context of the Rényian Formalism Applied to a Stable M/G/1 Queue and the Fractal Dimension’s Significance to Revolutionize Big Data Analytics. J Sen Net Data Comm. 2024, 4, 01–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I.A. Do You Speak The Mighty Triad?(Poetry, Mathematics and Music) Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. MDPI preprints 2024.

- Mageed, I.A. (2024g). Human-Trust Based Feedback Control (HTBFC) Five-.

- Dimensional Manifold Info-Geometric Analysis and how HTBEC Impacts Robotics.

-

Adv Mach Lear Art Inte. 2024, 5, 01–11.

- Mageed, I.; A. Info-Geometric Analysis of Human-Trust Based Feedback Control (HTBFC) Five-Dimensional Manifold with HTBFC Applications to Robotics. Preprints 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. Fractals Across the Cosmos: From Microscopic Life to Galactic Structures. Preprints 2025. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2025b). Surpassing Beyond Boundaries: Open Mathematical Challenges in.

- AI- Driven Robot Control. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.; Li, H. (2025a).The Golden Ticket :Searching the Impossible Fractal. S: Golden Ticket.

- Geometrical Parallels to solve the Millennium, P vs. NP Open Problem. Preprints.

- https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202506.0119.v1.

- Mageed, I.; Li, H. (2025b). Reaching the pinnacle of the digital world open mathematical.

- problems in AI-driven robot control. Soft computing fusion with applications 2025, 2, 75–85.

- https://doi.org/10.22105/scfa.v2i2.54.

- Marchegiani, F.; Siragusa, L.; Zadoroznyj, A.; Laterza, V.; Mangana, O.; Schena, C.A.; Ammendola, M.; Memeo, R.; Bianchi, P.P.; Spinoglio, G.; et al. New Robotic Platforms in General Surgery: What’s the Current Clinical Scenario? Medicina 2023, 59, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markan, S.; Verma, M.M.; Garg, V. (2025). Transformation of India’s Med-tech Ecosystem for Surpassing the Valleys of Death for Societal Impact: A Need for a Multi-sectoral Approach. In Innovations in Healthcare Technologies in India: An Initiative of ICMR-CIBioD (Centre for Innovation and Bio-Design) (pp. 119–126). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Mengxuan, C.H.E.N. PRIVACY PROTECTION AND ROBOCARE IN LONG TERM CARE. Revista Facultății de Drept Oradea, 2023, 1, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak, S.R.; Mishra, J. Analysis of medical images using fractal geometry. In Research anthology on improving medical imaging techniques for analysis and intervention; IGI Global, 2023; pp. 1547–1562. [Google Scholar]

- Oslock, W.M.; Jeong, L.D.; Perim, V.; Hua, C.; Wei, B. Robotic surgical education: a systematic review of strategies trainees and attendings can utilize to optimize skill development. AME Surg. J. 2024, 4, 19–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilavaki, P.; Ardakani, A.G.; Gikas, P.; Constantinidou, A. Osteosarcoma: Current Concepts and Evolutions in Management Principles. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarin, A.; Samreen, S.; Moffett, J.M.; Inga-Zapata, E.; Bianco, F.; Alkhamesi, N.A.; Owen, J.D.; Shahi, N.; DeLong, J.C.; Stefanidis, D.; et al. Upcoming multi-visceral robotic surgery systems: a SAGES review. Surg. Endosc. 2024, 38, 6987–7010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherif, Y.A.; Adam, M.A.; Imana, A.; Erdene, S.; Davis, R.W. Remote Robotic Surgery and Virtual Education Platforms: How Advanced Surgical Technologies Can Increase Access to Surgical Care in Resource-Limited Settings. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2023, 37, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Śliwczyński, A.; Szymański, M.; Wierzba, W.; Furlepa, K.; Korcz, T.; Brzozowska, M.; Glinkowski, W. (2024). Robotic-Assisted Surgery in Urology: Adoption and Impact in Poland.

- Sumathi, S.; Suganya, K.; Swathi, K.; Sudha, B.; Poornima, A.; Varghese, C.A.; Aswathy, R. A Review on Deep Learning-driven Drug Discovery: Strategies, Tools and Applications. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2023, 29, 1013–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szasz, A. Vascular Fractality and Alimentation of Cancer. Int. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 12, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togami, S.; Higashi, T.; Tokudome, A.; Fukuda, M.; Mizuno, M.; Yanazume, S.; Kobayashi, H. The first report of surgery for gynecological diseases using the hinotori™ surgical robot system. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2023, 53, 1034–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Merwe, J.; Casselman, F. Minimally invasive surgical coronary artery revascularization—Current status and future perspectives in an era of interventional advances. Journal of Visualized Surgery 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashisht, N.; Goyal, W.; Choudhary, S.; Jayakumar, S.S.; Patil, S.; Mohapatra, C.K.; Srividya, A. Ethical and Legal Challenges in the Use of Robotics for Critical Surgical Interventions. Semin. Med Writ. Educ. 2024, 3, 501–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuille-dit-Bille, R.N. Special issue on surgical innovation: new surgical devices, techniques, and progress in surgical training. Journal of International Medical Research 2020, 48, 0300060519897649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).