1. Introduction

Eukaryotic translational control of RNA is one of an important level of the regulation of gene expression. Most translational regulation occurs at the initiation stage [

1,

2]. Translation initiation is regulated on global and RNA-specific bias. Global translation involves the modification of the translational machinery, induces ribosomes and eukaryotic initiation factors (eIFs) such as eIF4E or eIF2α [

3]. Whereas RNA-specific translational regulation frequently occurs through the action of trans-acting factors [

4], including small RNAs and RNA binding proteins (RBPs).

RNA binding motif protein 24 (RBM24) is an RNA-binding protein that plays crucial roles in regulating the stability [

5,

6,

7], splicing [

8,

9,

10,

11] and translation initiation [

12] of target RNAs. Our previous study have indicated that RBM24 can modulate the translation of hepatitis C virus (HCV) by targeting the internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) located on the 5' region of viral RNA and subsequently inhibits the formation of the 80S translation initiation complex [

13]. Later, similar inhibition of 80S assembly by RBM24 has been observed in other 5' capped viral RNAs [

14,

15]. Theoretically, when regulating translation initiation, RNA-binding proteins is considered necessarily affecting the translation machinery, directly or indirectly, while binding target mRNAs [

16]. RBM24 inhibits the translation of tumor protein p53 (

TP53) mRNA through interacting with eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) [

12]. However, the inhibition of 80S ribosome assembly by RBM24 on HCV IRES and other capped RNAs cannot be explained by RBM24-eIF4E interaction: firstly, as an integral component of cap binding complex eIF4F, eIF4E is believed regulating eukaryotic translation at the 48S pre-initiation complex formation stage, not the 60S joining stage [

2]; Secondly, HCV IRES mediates translation initiation through a distinct pathway, in which eIF4F complex, eIF1, and even eIF2α are believed dispensable or at least not strictly necessary [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Therefore, it is of interest to search for other molecules, beside eIF4E, in the translation machinery that affected by RBM24.

HCV IRES mediated translation initiation involves 40S small subunit, 60S large subunit, eIF3 complex and eIF5B [

20,

26]. In this study, we hypothesized that RBM24 may interact with these translation machinery components while binding target RNAs to achieve 80S assembly inhibition. To test this hypothesis, we performed IP-MS and then selected some molecules from the results and investigate their interaction with RBM24. The data presented herein revels ribosomal protein L3 (RPL3/uL3), a core component of 60S large subunit and part of the ribosomal peptidyl transferase center (PTC) [

27], as an interaction partner of RBM24. Further results demonstrated that RBM24 enhances the interaction between RPL3 and eIF6. The Eukaryotic initiation factor eIF6 is an anti-association factor that prevents the joining of the 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits [

28,

29]. These findings provided a probably explanation to RBM24 mediated 80S assembly inhibition observed in previous studies.

2. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

2.1. RBM24 Interacts With RPL3 in Both IP and Pulldown Assays

Previous studies have indicated that RBM24 inhibits 80s assembly in both cap-dependent and HCV IRES mediated translation [

13,

14,

15]. Theoretically, to inhibit translation, RBM24 need to interfere with the translation machinery while binding mRNAs. RBM24 was reported interaction with eIF4E [

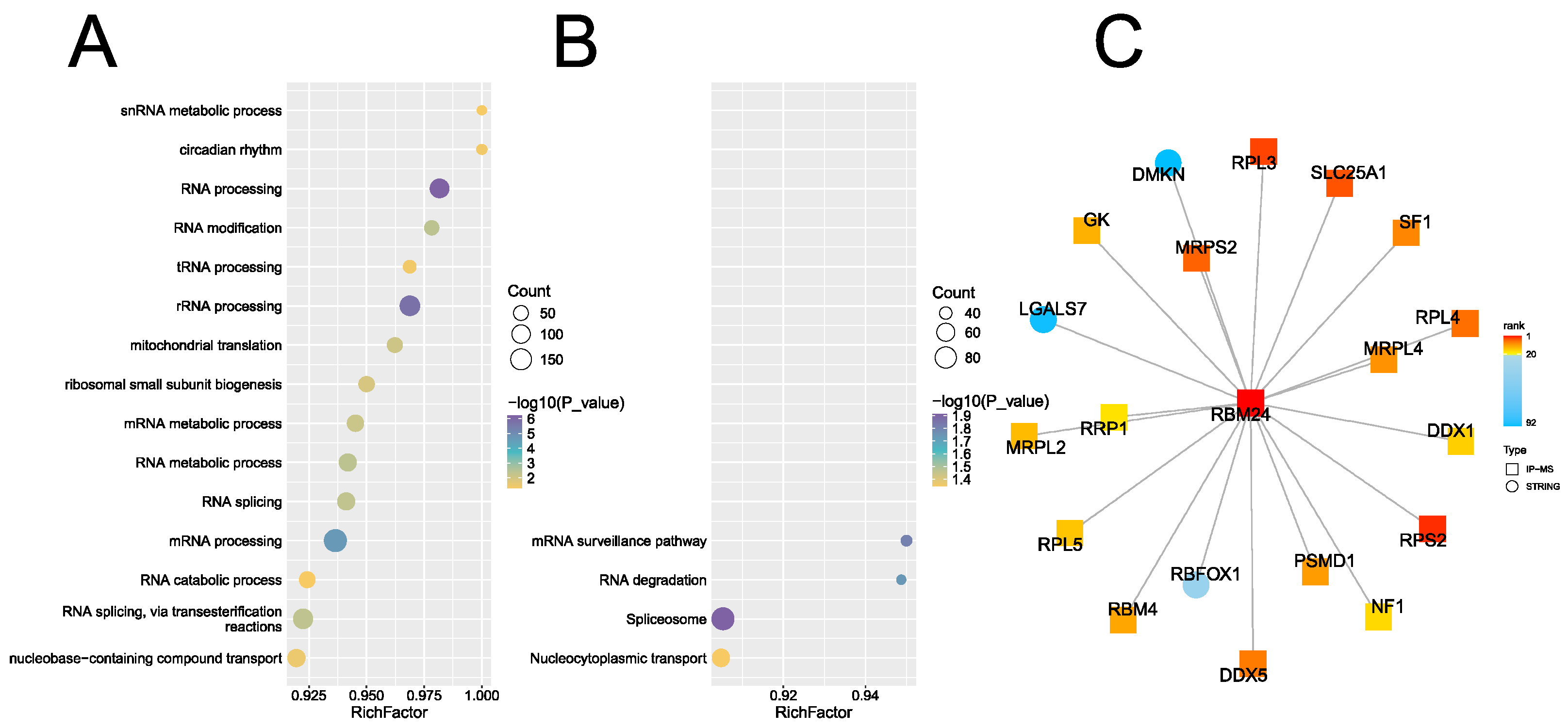

12], which is considered dispensable for HCV IRES mediated translation. Since HCV IRES need less factors or complexes of that 5' cap, we assumed that there are additional interaction partners exists among these indispensable "less", including eIF3, 40S, 60S and eIF5B. To test this hypothesis, we performed IP-MS analysis after pcDNA3.1-Flag-RBM24 plasmid transfection into 293T cells and immunoprecipitation with Flag antibody. Proteins with log2 fold change >2 was defined as "interactor" of RBM24 according to the mass spectrometry service provider's instruction. These "interactor" proteins were enriched in RNA splicing related processes (GO, Figure A) or pathways (KEGG, figure B). This result was consistent with the known function of RBM24. We also identified ribosomal proteins such as RPL3 as "interactor" in MCC subnetwork (

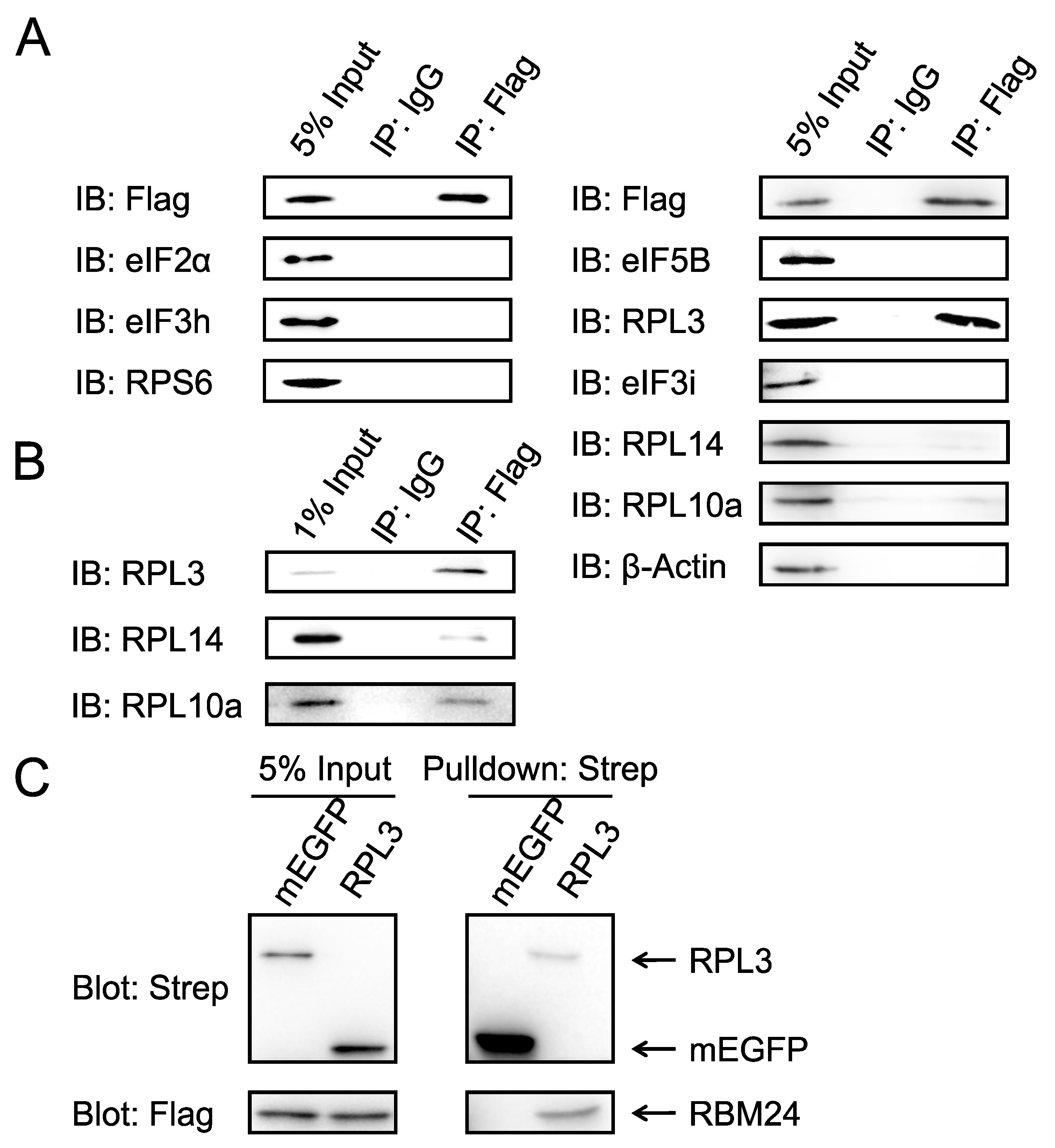

Figure 1C). However, considering that translation initiation was neither a bioprocess in GO nor a pathway in KEGG, we decided to select translation related proteins from the full IP-MS result list manually. As listed in sheet "IP-MS(Bait_RBM24)" of file "Supplementary_File_S3_IP-MS_and_TRAP-DIA.xls", 28 RPSs, 40 RPLs, 22 eIFs, 3 eEFs, 20 MRPSs and 25 MRPLs were detected. Among these detected, 27 of 28 RPSs, 35 of 40 RPLs, and all of the eIFs, eEFs, MRPSs and MRPLs were identified as "interactor" proteins of RBM24. Considering both the signal intensity in IP-MS and the commercial availability of antibodies, from that identified as "interactor", RPS6, RPL14, RPL3 and eIF3i were selected for further co-IP-WB validation. RPL10a (identified as "unspecific") was also included in co-IP-WB validation. From that not detected in IP-MS, eIF3h was included because it located at a distant place from eIF3i in eIF3. eIF2α and eIF5B were included for their reported importance in tRNA joining and 60S subunit joining, respectively. eIF4E, a reported interactor of RBM24 which was also identified as an interactor of RBM24 in our IP-MS result, was not included because it was considered dispensable for HCV IRES mediated translation. β-Actin, which was not detected by IP-MS, was included as an putative negative control. Assuming that the proteins in translation machinery were highly expressed and sufficient for co-IP detection, pcDNA3.1-Flag-RBM24 was transfected into 293T cells without co-transfecting target plasmid. IP was performed with Flag antibody, and the antibodies against each of the targets were used to detect co-precipitated endogenous proteins. Luckily, at this very first round of validation, a robust band of RPL3 in the "IP: Flag" column was detected, indicating a strong association between RBM24 and RPL3 (

Figure 2A). The association of RBM24 with RPL14 and RPL10a were also detected, but were extremely weak (

Figure 2A) compared to that of RPL3, and can only be obviously observed (

Figure 2B) when lowering the loading amount of the "input" from 5% to 1%, despite of that the signal intensity of RPL14 was greater than that of RPL3 in IP-MS. Association of RBM24 with eIF2α, eIF3i, eIF3h, eIF5B were not detected (

Figure 2A). Surprisely, RPS6, identified as "interactor" of RBM24 in IP-MS with signal intensity greater than all other proteins included in this first round of validation, was not detected associated with RBM24.

By examining the results of RPL3, RPL14, RPL10a and RPS6 in IP-MS and subsequent co-IP-WB validations described above, we proposed that RBM24-RPL3 interaction was more likely directly, not indirectly. To demonstrate this opinion, we expressed C-terminal Twin Strep tagged RPL3 and N-terminal Flag tagged RBM24 as recombinant proteins, and perform Strep tag pulldown with these purified recombinant proteins. C-terminal Twin Strep tagged recombinant mEGFP (A206K) was incorporated as a putative negative control. The monomerizational mutation A206K [

30] was introduced into EGFP because that recombinant EGFP with C-ter Twin Strep tag forms perfect dimmer even after been boiled in a buffer containing 2% SDS and 50 mM DTT (data not shown). Both RPL3 and mEGFP band detected by Strep-Tactin-HRP appeared in "Pulldown: Strep" panel, indicating a successful Strep tag pulldown assay (

Figure 2C). The recombinant RBM24 protein, which was detected by Flag antibody, was not co-precipitated by mEGFP, revealing that mEGFP is a real, no longer a putative, negative control for RBM24 interaction (

Figure 2C). The co-precipitated RBM24 band appeared in "RPL3" column of "Pulldown: Strep" panel indicated a direct interaction between RPL3 and RBM24 (

Figure 2C).

2.2. RBM24 Binds Both Exposed and 28S-embeded Region of RPL3

RPL3 is an indispensable component of 60S subunit that forms part of the ribosomal peptidyl transferase center (PTC) [

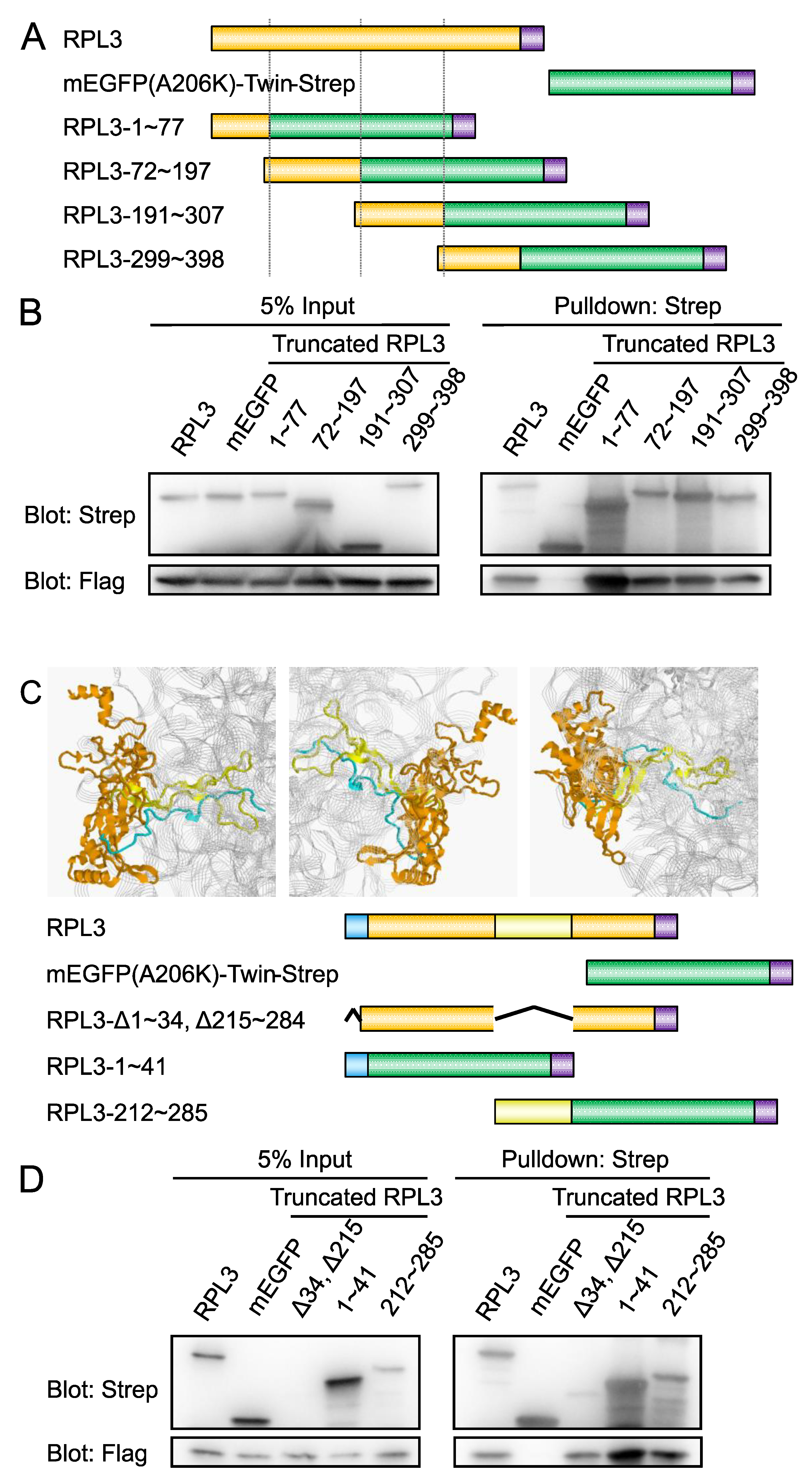

27]. The position and function of RPL3 in 60S subunit are well studied. Therefore, further exploration of that which regions of RPL3 interact with RBM24 may help to the understanding of how RBM24 block 60S joining. We split RPL3 at the regions that not contact with other molecules according to PDBe-KB [

31], and constructed 4 RPL3 truncated fragments (

Figure 3A). These fragments were then fusion expressed with C-ter mEGFP and Twin Strep tag, and purified as recombinant proteins, namely RPL3-1~77, RPL3-72~197, RPL3-191~307, RPL3-299~398 (

Figure 3A). These 4 truncated RPL3 were then subjected to Strep tag pulldown assay as bait. The full length RPL3 was incorporated as positive control, and the mEGFP with C-ter Twin Strep tag was incorporated as negative control. The results revealed that RPL3 co-precipitated RBM24, while mEGFP did not, demonstrated a successful pulldown assay (

Figure 3B). Surprisingly, all of the 4 truncated RPL3 fragments co-precipitated RBM24 (

Figure 3B). These results suggested that one RPL3 molecule may binds multiple RBM24 molecules, and provided a possible explanation for the robust co-IP signal in

Figure 2A and 2B. However, we could not infer how RBM24 affect RPL3 form these results.

Since RBM24 interacted with all 4 of the RPL3 fragments 1~77, 72~197, 191~307, 299~398, we assumed that RBM24 may also interact with 28S-embeded regions of RPL3, and affect RPL3-28S binding. As a large subunit protein, the 3D structure of RPL3 in the large subunit is well studied. We downloaded 6ZMI [

32], a recent human 60S structure at the time point performing the assays of

Figure 3, and label the 28S-embeded regions in RPL3. As shown in

Figure 3C, the 1~43 (cyan) and 212~285 (yellow) residues of RPL3 inserted into 28S rRNA (white string), the rest (orange) of the residues in RPL3 located on the surface of 28S rRNA. We constructed 3 RPL3 truncated fragments according to this 3D structure and expressed them as recombinant proteins, namely RPL3-Δ1~34, Δ215~284 (RPL3-Δ34, Δ215 for short), RPL3-1~41, RPL3-212~285 (

Figure 3C). RPL3-1~41 and RPL3-212~285 were fusion expressed with C-ter mEGFP and Twin Strep tag, while RPL3-Δ1~34, Δ215~284 was fusion expressed with C-ter Twin Strep tag without mEGFP. These 3 truncated RPL3 fragments were then subjected to Strep tag pulldown assay as baits. Again, RBM24 was co-precipitated by all of these 3 RPL3 fragments (

Figure 3D). This result revealed that RBM24 binds to Both Exposed and 28S-embeded Region of RPL3.

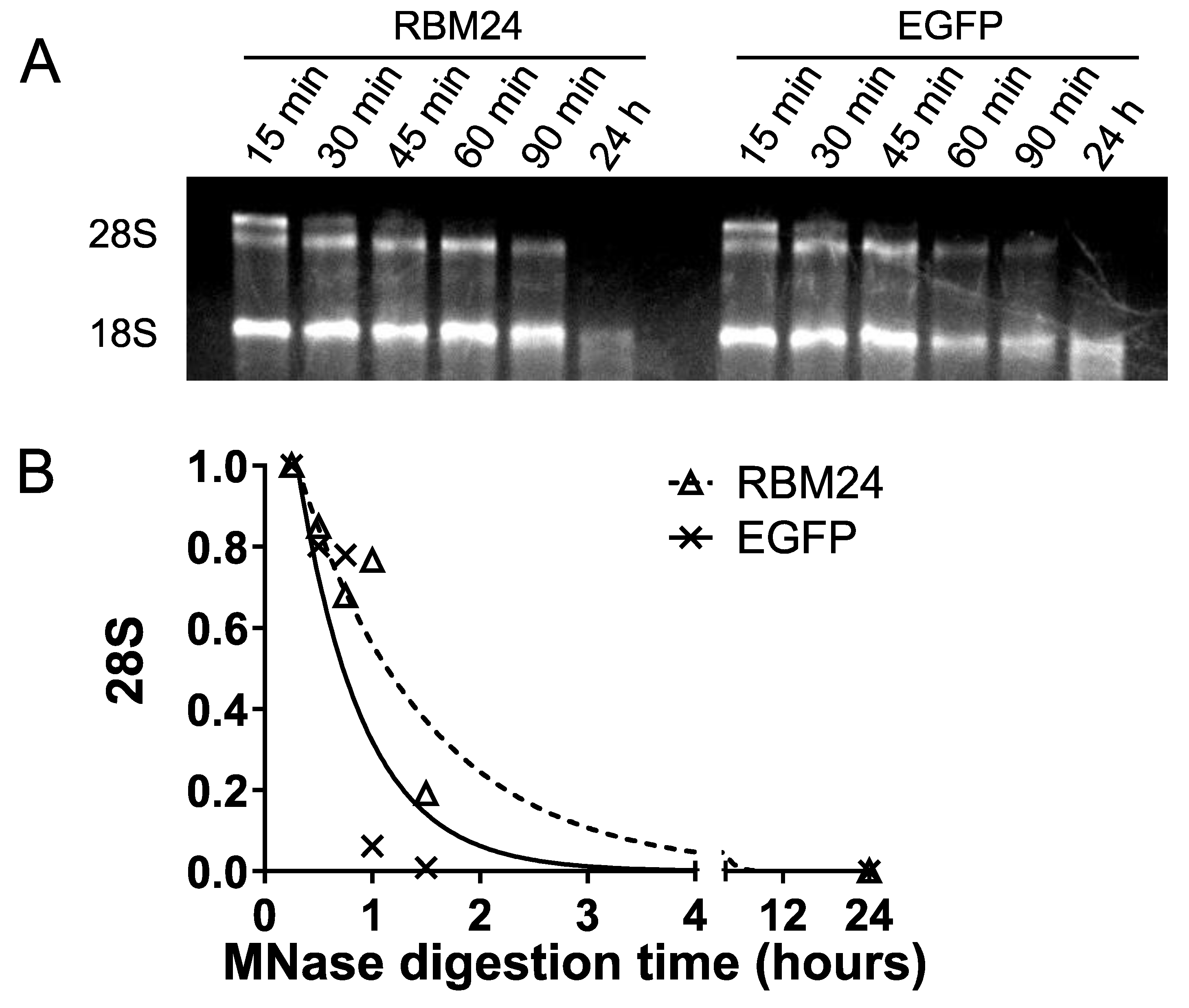

2.3. RBM24 does not Vulnerate 28S rRNA to Micrococcal Nuclease

Since RBM24 interacts with the 1~41 and 212~285 regions of RPL3 that deeply inserted into 28S rRNA, we assumed that RBM24 may interfere with RPL3-28S interaction and destabilize 60S ribosome, vulnerate 28S rRNA to nuclease (Figure 4B). To test this hypothesis, we transfected pcDNA3.1-Flag-RBM24 and pcDNA3.1-msEGFP1.8 [

33] into 293T cells, collected the cell lysates, and treated them with micrococcal nuclease (MNase) plus CaCl

2 for 15~90 min. As shown in

Figure 5A, both 28S and 18S are stabilized, or at least not destabilized nor vulnerated, against MNase. Since 18S rRNA was also significantly stabilized here, 28S alone, not 28S/18S, was used for gray density analysis with ImageJ (

Figure 5B). From this result, we concluded that the probability of that RBM24 stripping RPL3 off from 60S subunit were very low, and aborted further binding assay that explore the effect of RBM24 on RPL3-28S interaction.

2.4. RBM24 Enhances the Interaction Between the RPL3 and eIF6

RPL3 is not reported directly involved in 60S-40S joining. If we concluded that RBM24 could not affect 60S stability through interaction with RPL3, we would have to assume another explanation for how RBM24 block 80S assembly. Such a possible explanation could be that, through binding RPL3, RBM24 blocks factors necessary for 60S joining, and/or recruits factors suppressing 60S joining (Figure 4C). A ribosome affinity capture assay was designed to explore these possibilities. Since RPL3 also functions in ribosome-free forms [

34,

35], overexpression of RPL3 with transfected plasmid probably generate vast of ribosome-free RPL3 and fail the ribosome affinity capture assay. To avoid this, we generated a cell line with homozygous endogenous C-ter Twin Strep tagged RPL3 based on 293T cells through CRISPR/Cas9 mediated knock-in, namely 3A8. The details of this cell line were described in "Supplementary_File_S5_Supplementary_Methods.doc". The 3A8 cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1-Flag-RBM24 or pcDNA3.1-msEGFP1.8 plasmid and subjected to ribosome affinity capture assay (

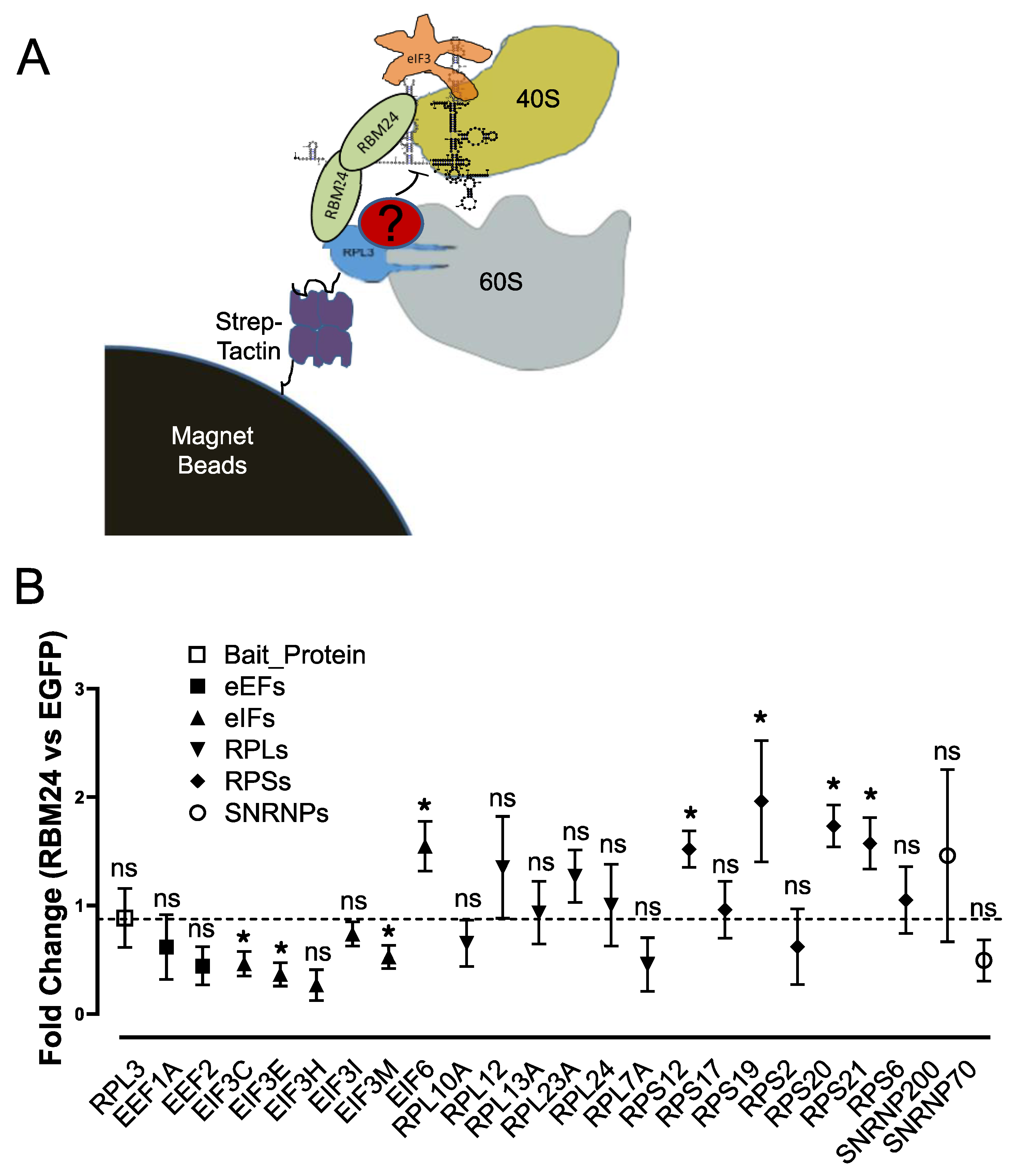

Figure 6A), and the ribosome associated proteins were quntified by mass spectrometry (Data-Independent Acquisition, DIA). HCV IRES was incorporated in this assay. Poly[I:C] and ATP was introduced to inactivate eIF2α, in order to further abolish the involvement of capped mRNA that survived from MNase treating. The intensity of quantified proteins was normalized with the intensity of a streptavidin variant, and list as fold change (RBM24 transfected group vs EGFP transfected group) in "Supplementary_File_S3_IP-MS_and_TRAP-DIA.xls". Some proteins of our interesting were plot as dots corresponding to their intensity fold change, as shown in

Figure 6B. The intensity of the bait protein RPL3 itself (dash line) on the beads was not significant changed. Some of proteins from eIF3 complex were significantly lowered by RBM24, indicating the translation inhibition effect of RBM24. All the detected RPLs were not significant changed between RBM24 transfected and EGFP transfected groups further supported the implication that RBM24 does not affect 60S stability. Some of the RPSs that relatively distant from RPL3 in 80S, such as RPS12, RPS19, RPS20, RPS21, were significantly more associated with RPL3 in RBM24 transfected group, while some of the RPSs that relatively proximate to RPL3 in 80S, such as RPS2 and RPS6, remains not significant changed. Interestingly, eIF6, a known anti-association factor that prevents the joining of the 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits [

28,

29], was significantly more associated with RPL3 in RBM24 transfected group (

Figure 6B).

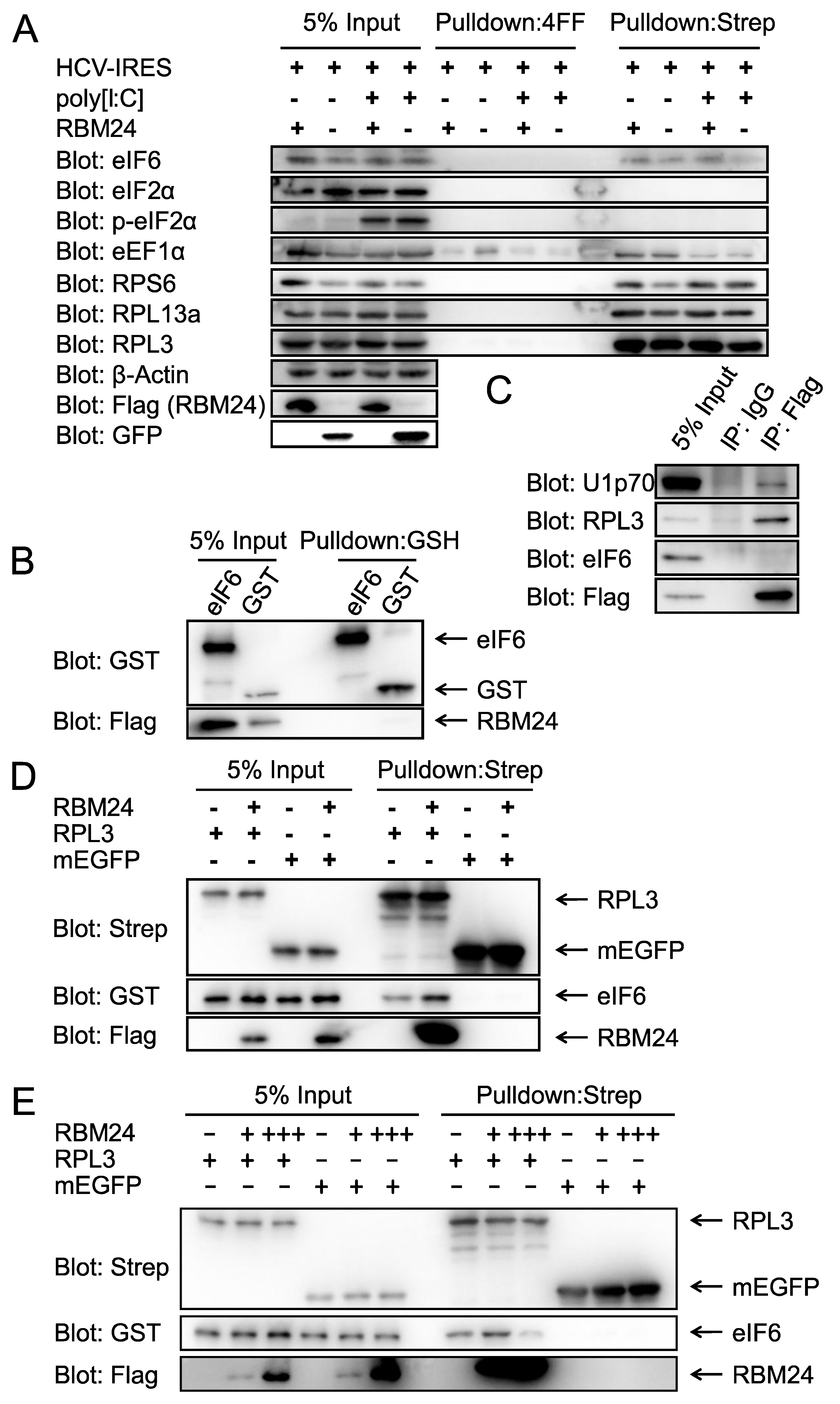

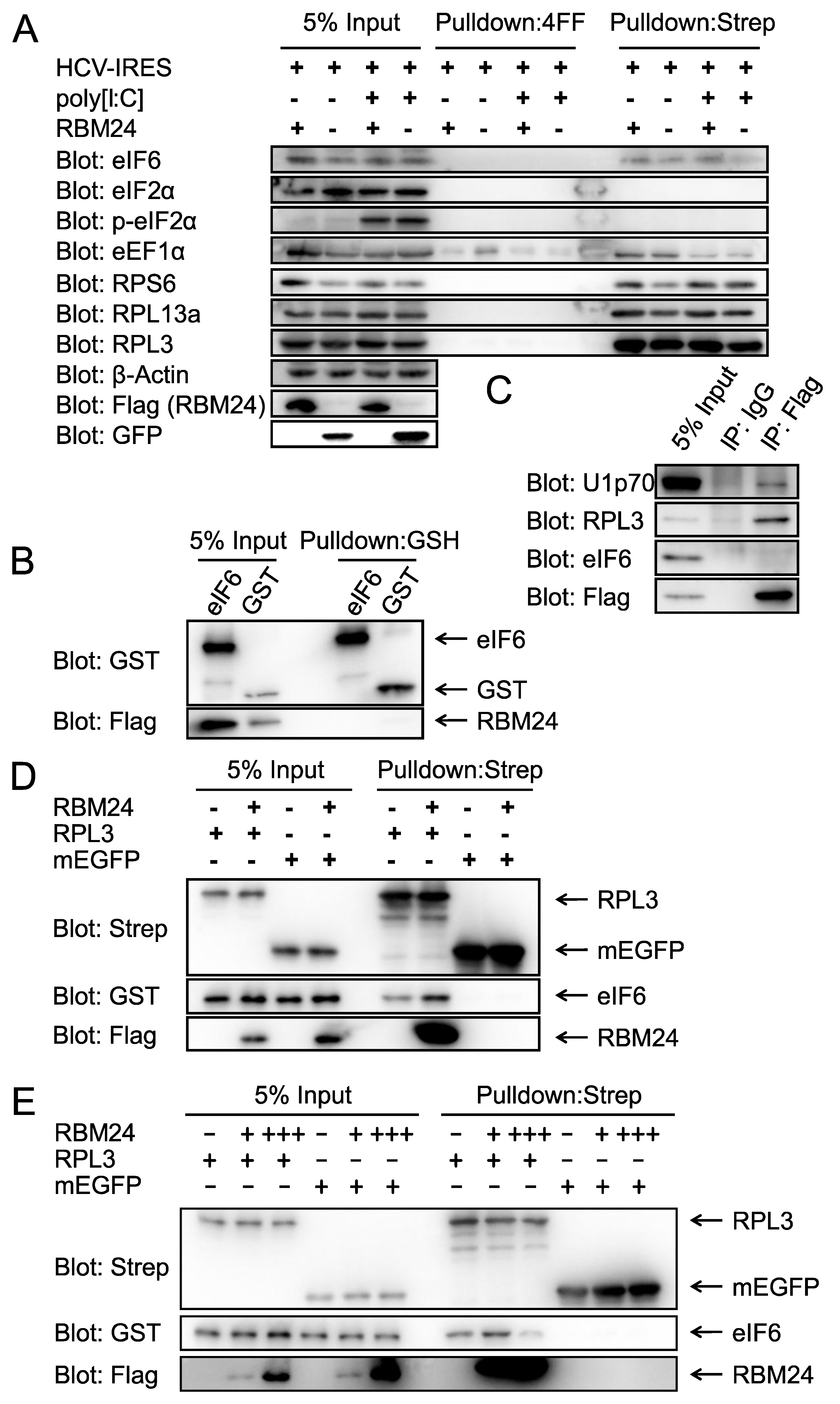

The ribosome captured beads generated from the same procedure were then subjected to WB validation (

Figure 7A). As shown in

Figure 7A, The present of RPL3 and RPL13a in "Pulldown: Strep" demonstrated successful large unit capture, and p-eIF2α in "5% Input" demonstrated successful poly[I:C] treatment. The association of eIF6 with large subunit was significantly enhanced in RBM24 transfected group compared with mEGFP transfected group when eIF2α was deactivated by phosphorylation (

Figure 7A). Since eIF6 is an anti-association factor, enhanced eIF6 binding to 60S could be a good explanation for 80S assembly inhibition induced by RBM24.

Base on these results, we assumed that RBM24 might interact with eIF6 and RPL3 simultaneously, through which RBM24 enhance 60S association of eIF6. To test this hypothesis, we refer to our IP-MS result described above, and found eIF6 an "interactor" (log FC > 2) ("Supplementary_File_S3_IP-MS_and_TRAP-DIA.xls"). Further, we purchased GST tagged eIF6 recombinant protein and performed GST-pulldown assay to investigate the interaction between eIF6 and RBM24. Unfortunately, no visible signal of RBM24 co-pulldown by eIF6 was observed, indicating that RBM24 does not interact with eIF6 (

Figure 7B). We then performed co-IP assay to further validate this result. Considering RPL3 a too robust positive control to falsify an interaction, the p70 protein of U1 snRNP (gene name

SNRNP70, another "interactor" of RBM24 in our IP-MS result and a putative interactor we implied from reported [

9], labeled U1p70) was included as another positive control. Again, in this co-IP assay, there were no detectable association between RBM24 and eIF6 (

Figure 7C). Thus, we concluded that there are no interaction between RBM24 and eIF6, or even if there were, the binding affinity would be lower than the detection threshold of GST-pulldown and co-IP assays.

Base on these results, we updated our hypothesis, now assuming that the binding of RBM24 on RPL3 and induce some changes that enhance RPL3-eIF6 interaction. This hypothesis still included the assumption that RPL3 would interact with eIF6. RPL3-eIF6 interaction can be inferred from 3D models [

36], but lack of directly supporting experimental data. Thus, we continue to perform the 3 factors Strep tag pulldown assay incorporated Twin Strep tagged RPL3, GST tagged eIF6 and Flag tagged RBM24. As shown in

Figure 7D, eIF6 was co-precipitated by RPL3 alone, indicating a direct interaction between RPL3 and eIF6. When RBM24 was incorporated, RPL3 co-precipitated increased amount of eIF6, indicating an enhanced RPL3-eIF6 interaction induced by RBM24 (

Figure 7D). Next, we raise the amount of recombinant RBM24 protein in the 3 factors Strep tag pulldown assay and found that, RBM24 enhanced RPL3-eIF6 interaction when it was at the same amount (50 pmol) of RPL3, but inhibited RPL3-eIF6 interaction when it was 4X overdosed (200 pmol) of RPL3 (

Figure 7E). This result suggested that the regulation of RBM24 on RPL3-eIF6 interaction is dose-dependent. In summary, these results showed that RBM24 interact with RPL3, and enhance RPL3-eIF6 interaction without interact with eIF6.

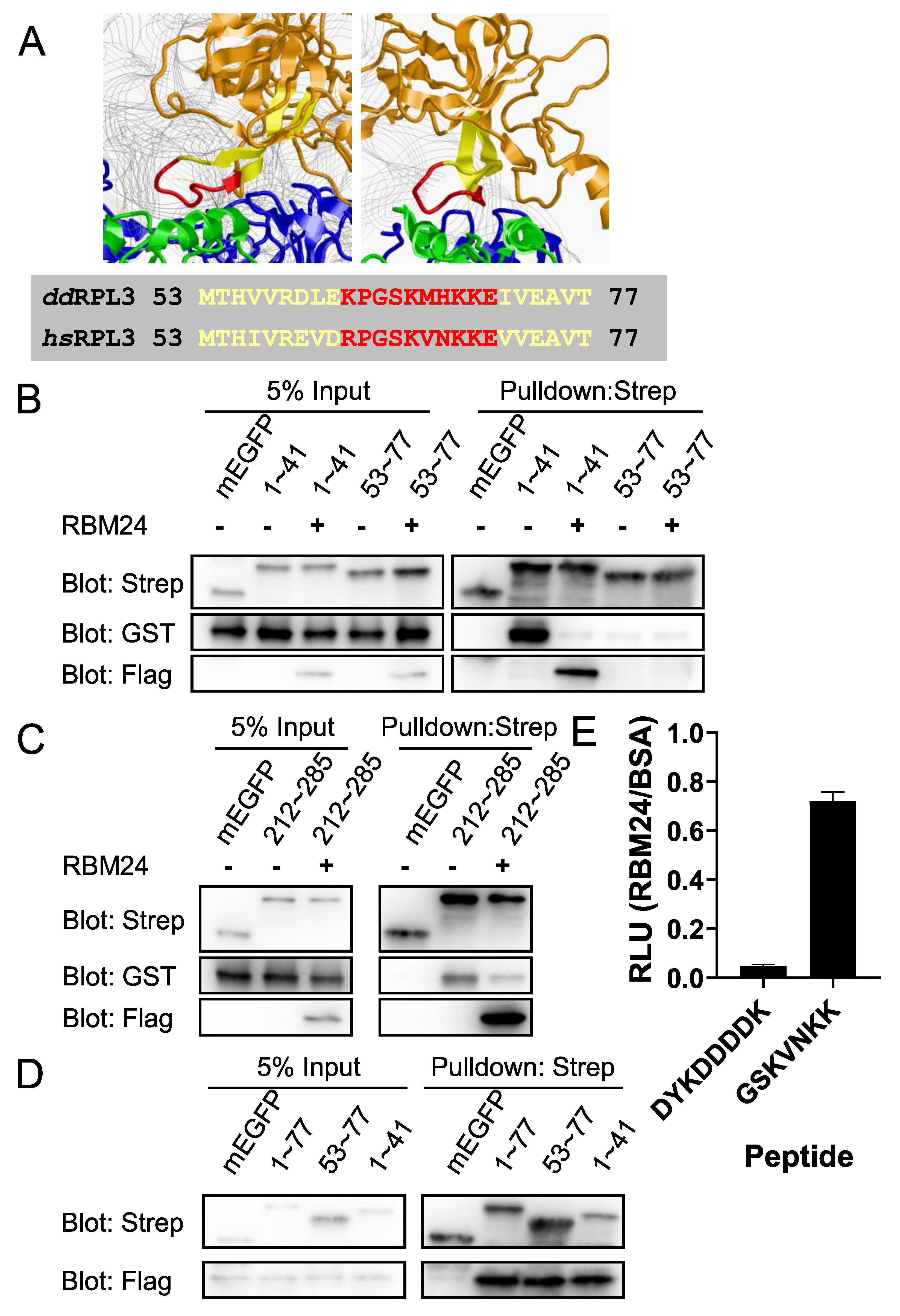

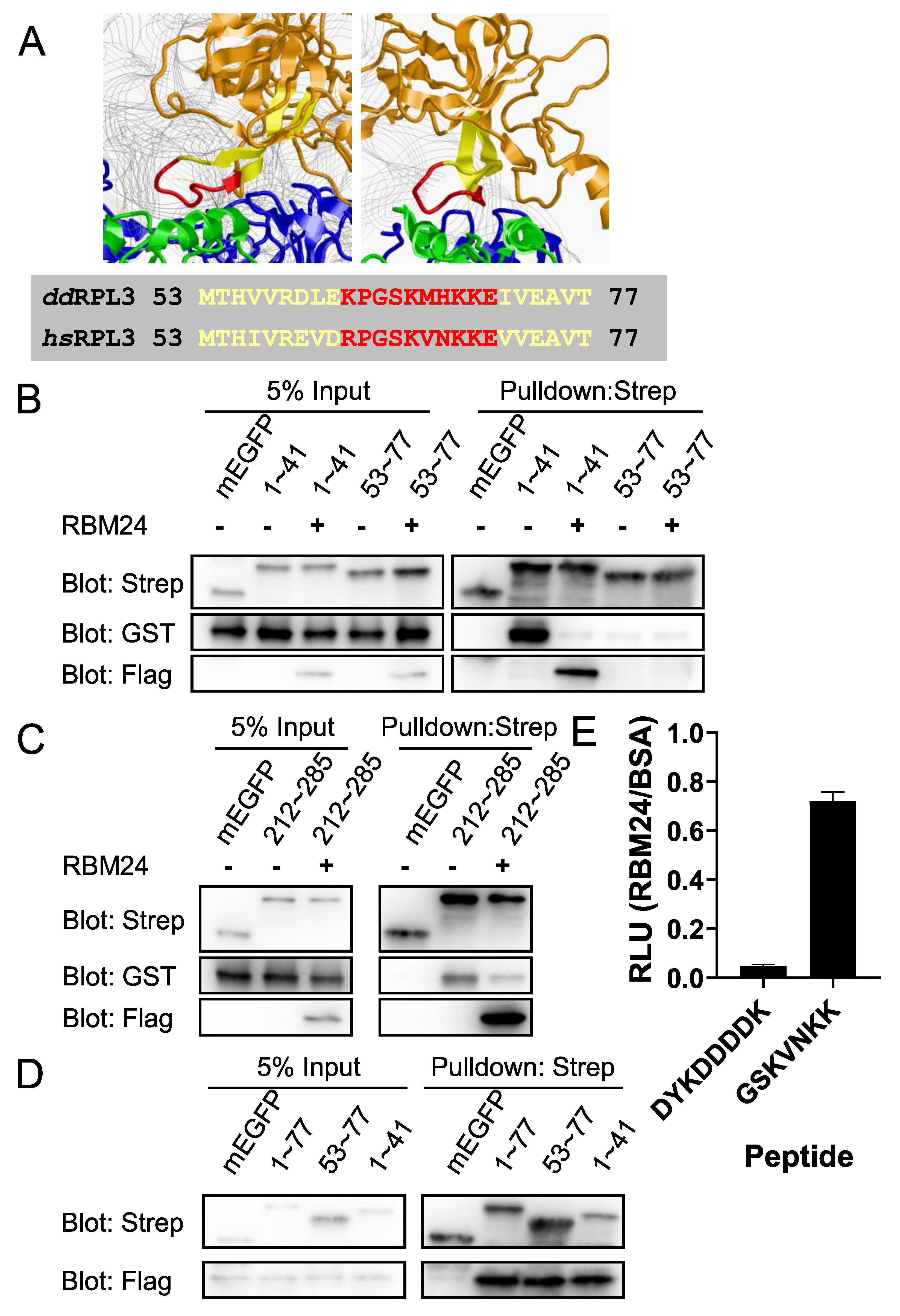

2.5. RBM24 Blocks the Binding of eIF6 to 28S-embeded Regions in RPL3

RPL3-eIF6 interaction can be inferred from 3D models. We downloaded a 3D model, 6QKL [

36], a 3D model of

Dictyostelium discoideum eIF6 binds to

Dictyostelium discoideum 60S subunit. By analyzing this model, we found that the only residues in RPL3 (orange) contacted with eIF6 (green) in 6Å range were 62~71 (red) (

Figure 8A). We constructed a truncated human RPL3, RPL3-53~77 (yellow in

Figure 8A), fusion expressed with C-ter mEGFP and Twin Strep tag. Note that the 53~77 residues in

Homo. sapiens RPL3 was numbered the same as

Dictyostelium discoideum RPL3 shown in

Figure 8A. The RPL3-53~77 protein was then subjected to 3 factors Strep tag pulldown assay. The result revealed that, eIF6 indeed interacted with RPL3-53~77 region, but in a much weak manner (

Figure 8B). Surprisingly, eIF6 interacted with RPL3-1~41, a 28S-embeded region, much stronger than that with RPL-53~77 (

Figure 8B). Additional assay revealed that eIF6 interacted robustly with RPL3-212~285, another 28S-embeded region (

Figure 8C). Incorporating of RBM24 at the same amount (50 pmol) of RPL3 fragments blocked the binding of eIF6 to RPL3-1~41 and RPL3-212~285, while did not affect the binding of eIF6 to RPL3-53~77 (

Figure 8B & 8C). Also, the result showed that RBM24 was not co-precipitated by RPL3-53~77 in the present of eIF6 (

Figure 8B). We then perform Strep tag pulldown with RPL3-53~77 without incorporating of eIF6, and the result showed that, in the absence of eIF6, RPL3-53~77 co-precipitated RBM24 (

Figure 8D). In summary, RBM24 blocked the binding of eIF6 to RPL3-1~41 and RPL3-212~285, while did not blocks the binding of eIF6 to RP3-53~77.

2.6. RPL3 Derived Peptide Rescues RBM24 Mediated Translation Inhibition

As mentioned above, the only residues in RPL3 that contacted with eIF6 in 6Å range in 3D model 6QKL [

36] were 62~71 (

Figure 8A), we hypothesized that: if RBM24 mediated translation inhibition were operated through enhancing eIF6-RPL3 interaction, a peptide derived from these contacting residues would block the interaction between eIF6 and 60S subunit, and then rescue the translation inhibition mediated by RBM24. To test this hypothesis, we designed an in vitro translation assay incorporating peptide competitor derived from eIF6 contacting region of RPL3. The residues in RPL3 within 4Å range of eIF6 in 6QKL are: 64, 65, 66, 68, 70, based on this, human RPL3-64~70 (GSKVNKK) was selected as peptide competitor, with Flag peptide (DYKDDDDK) as control peptide. In the initial attempts, we calculated peptide amount according to recombinant RBM24 protein. However, adding peptide at 10X overdose to RBM24 did not rescue the translation inhibition of RBM24 (

Figure S6A). Here, we realized that the peptide is a competitor of RPL3, not RBM24, and the amount of RPL3 in our in vitro translation system was theoretically extremely large according to the technical support of Promega. We then revised the experiment design, raised the peptide amount to a comparable level of estimated RPL3 in RRL. As indicated in

Figure 8E, The RLU (RBM24/BSA, or RLU fold change) of peptide DYKDDDDK group was significantly (t-test) lower than 1, indicating the translation inhibition effect of RBM24, which is in consistent with previous results [13-15]. The RLU (RBM24/BSA) of peptide GSKVNKK group was significantly (t-test) more approaching 1 compared with peptide DYKDDDDK group, suggesting a successful rescue of translation inhibition (Fig 5E). We also performed IP-depletion of eIF6 in RRL for rescue of translation inhibition. As shown in

Figure S6B, while eIF6 was IP-depleted, the translation inhibition of RBM24 was significantly (though visually not, it was indeed significant by t-test) rescued. These results suggested that disrupting of RPL3-eIF6 interaction attenuated the translation inhibition effect of RBM24, and elucidated that the mechanism of RBM24 mediated translation inhibition on HCV IRES was operated through enhancing the RPL3-eIF6 interaction.

2.7. Cellular IRES Candidates Potentially Targeted by RBM24

For all the experiments described above that the cap-independent translation inhibition of RBM24 was tested, HCV IRES, a viral RNA element, was used as a cap-independent translation model. However, since RBM24 is not generously considered an innate immune gene, and also considered that our co-pulldown assay did not incorporated any RNA, it would be reasonable to assume that RBM24 regulates cellular cap-independent translation in a similar manner of that regulates viral IRES. To confirm this assumption, we perform a RIP-seq assay, to find the cellular 5'UTR candidates that may targeted by RBM24. In this assay, purified cellular total RNA and purified recombinant RBM24 were used to exclude the indirect RNA binding (Such as RBM24 binds TP53 5' UTR through eIF4E as reported [

12]). The purified RNA was fragmented before adding RBM24, in order to exclude 5' UTR reads generated by RBM24 binding at 3' UTR, splicing box or other regions. Reads mapped to 5' UTR region of transcripts were counted and listed in "Supplementary_File_S4_RIP(Bait_RBM24).xls". As shown in these tables,

TP53, a reported indirect target of RBM24, was not appeared, indicated successful exclusion of indirect RNA binding by using recombinant protein and purified RNA. However,

CDKN1A, or simply as p21, a known gene of which 3' UTR was targeted by RBM24, did appeared in the list, indicated Imperfect exclusion of long range RNA binding by fragmentation before adding RBM24. Since the counts of

CDKN1A (ENST00000244741) 5' UTR were 16, 1, 4 in three replicates, we considered 16 as the cut-off counts value for transcripts of which 5' UTR was binding by RBM24. From the results, we can implied that the 5' UTR of RBM24 itself and some other RPLs (RPL38, RPL36, RPL41, e.g.) was targeted by RBM24 protein, while the 5' UTR of RPL3 or eIF6 was not. Every individual 5' UTR region binding by RBM24 protein implied from this result needs further validations.

3. Discussion

RBM24 inhibits 80S assembly in both cap-dependent and HCV IRES mediated translation [

13,

14,

15], of which the mechanism has still not been fully elucidated. In this study, by assuming that RBM24 may affect translation machinery while binding mRNAs, we identified ribosomal large subunit protein RPL3/uL3 as an interaction partner of RBM24. Further investigation revealed that RBM24 enhance the binding of eIF6, an anti-association factor, to RPL3. These findings provided a probably explanation for 80S assembly inhibition induced by RBM24 observed in previous works[

13,

14,

15].

RBM24 is well known as a splicing regulator [

8,

9,

10,

11], and was reported promotes splice site recognition of U1 snRNP [

9]. We observed co-precipitation of U1 snRNP p70 protein in both IP-MS and co-IP-WB results. Considering that the RNA binding of p70 is Mg

2+ dependent and that our IP system contains EDTA, it would be likely that RBM24 directly, rather than indirectly, interact with p70. We observed binding of RBM24 to 28S-embeded regions of RPL3, from which we can infer that RBM24 may also bind to ribosome-free RPL3. Further considering the self-interaction of RBM24 [

13], it would be reasonable to assume that RBM24 could relocate ribosome-free RPL3 to U1 snRNP, and incorporate RPL3 into the splicing machinery. However, the RPL3 associated U1 p70 protein in our DIA result was not significant changed between RBM24 and EGFP group, from which we implied that RPL3 itself can incorporated into splicing machinery without the help of RBM24. Currently we do not have sufficient data to confirm or falsify these two assumptions.

Besides RPL3, there are other two L3 proteins in human cells. One is RPL3L, a L3-like protein with similar tissue specific expression pattern of that RBM24 [

37]. It has been reported that there were 11 transcripts identified significantly altered transcription efficiency upon RPL3L deletion [

38], 6 of these 11 had identified putative IRES elements in their 5' UTRs [

39]. In

Homo. sapiens, RPL3L shares 76% identity at protein level of RPL3, and the identity decreases to 60% for RPL3-55~75 and decreases to 43% for RPL3-64~70 [

40]. It would be reasonable to assume that RPL3L would not interact with eIF6, or interact with eIF6 in a different manner of that RPL3, result in a putative different translation regulation pattern by RBM24. Another L3 protein in human cells is MRPL3, the mitochondrial L3 protein. Since mitochondrial translation machinery resembles that of prokaryotes rather than of eukaryotes and does not involve eIF6, it would be not likely that RBM24 would regulate mitochondrial translation. It would be interesting to explore the interplay of RBM24 and these alternatives of RPL3 in future works.

The anti-association activity of eIF6 was reported coupled with 60S recycling [

29]. Considering the result that RBM24 enhance eIF6-60S association especially when eIF2α was inactivated, we can assume that: When eIF2α was inactivated, all the available ribosomes can be used for the translation of eIF2α-independent mRNAs, and the accumulation of RBM24 on certain mRNAs attenuates this putative over-reaction through enhancing the association of eIF6, which then recycles and reserves available 60S, benefits the cells recovering from stress. The RNA binding activity of RBM24 may regulate the local concentration of RBM24, increase RBM24 amount around specified RNAs. In this hypothesis, the transient translation inhibition may result in an overall or long-term translation enhancement [

41], which provides an alternative explanation for our previous result that RBM24 facilitates HCV replication despite its translation inhibition effect [

13]. However, currently we do not have sufficient data to confirm or falsify this assumption.

Besides RPL3 (uL3), RPL23 (uL14), RPL24 (eL24) and the sarcin-ricin loop (SRL) of 28S rRNA are also involved in eIF6-60S binding. RPL3 also functions in ribosome-free forms [

34,

35]. In cells, by defining eIF6 binding on 28S-embeded RPL3 residues as a "wrong binding", we can assume that the eIF6-60S binding would be further enhanced by RBM24 through blocking the interaction between eIF6 and ribosome-free RPL3. However, one of our Strep tag pulldown assay were performed with purified recombinant proteins in the absent of other proteins, RNAs and 28S-embeded region of RPL3. The result of this assay suggested that RBM24 alone can enhance eIF6-RPL3 interaction without the involvement of other factors. In the case of in vitro assays with purified proteins, considering that RBM24 does not interact with eIF6, it would be difficult for us to hypothesize the mechanism how RBM24 enhance eIF6-RPL3 interaction. Considering that RBM24 interacted with RPL3-53~77 in the absent of eIF6 while did not interacted with RPL3-53~77 in the present of eIF6 (Fig5B, D), we can assume that RBM24 works as a protectant occupying RPL3-53~77 residues until eIF6 presents. When 4X overdose of RPL3, RBM24 inhibits instead of enhances RPL3-eIF6 interaction (Fig 4E). However, it is likely that this inhibits could only be observed in assays incorporate recombinant proteins, because that in cells the 4X overdose of RPL3 cannot be achieved in cells even when overexpressing by transfecting pcDNA3.1 based plasmid. Another possible explanation could be that RBM24 induces some conformation changes of RPL3 upon binding, but currently we do not have sufficient data to confirm or falsify this assumption.

RBM24 is a gene not been considered restrict its function to innate immune. Thus, the translation regulation pattern of RBM24 concluded from viral IRES model would be generalized to the translation regulation of human genes especially that undergo cap-independent translation. In this work, Through RIP-seq, we get a list of transcripts, of which RBM24 protein binding to the 5' UTR region. In this result, the 5' UTR of RBM24 transcript itself was the most bonded 5'UTR by RBM24 protein ("Supplementary_File_S4_RIP(Bait_RBM24).xls"). This would not be a false positive result from plasmid contamination, because: 1) We use purified recombinant RBM24, not plasmid, to perform RIP; 2) The 5' UTR region of RBM24 (ENST00000379052.10:R.1-221, or GRCh38.p14.Chr6: 17281361-17281580) was never cloned in our lab and was not included in any of our plasmids. This result revealed a potential feedback regulation of RBM24. As mentioned above, RPL3L shares 76% identity with RPL3 of the whole protein but only 43% of the eIF6 contacting region. Here we assumed that The RPL3L-containing 60S overcome the feedback regulation of RBM24, allow vast translation of RBM24 transcripts. This assumption also allowed RPL3L-containing ribosomes to translate other transcripts of which translation were inhibited by RBM24. These assumptions might be important, because that RPL3L-containing ribosomes were reported not codon occupancy biased nor transcripts biased vs. RPL3-containing ribosomes [

38]. However, currently we do not have sufficient data to confirm or falsify this assumption. Other 5' UTRs potentially targeted by RBM24 (e.g. RPL38, RPLP1, RPL5, H4C11, PTMA, H1-0, H1-4, FTL, EIF1, SLIT2, RPL37A, for full list, refer to the supplementary files) may also of great interest, but will not be investigated in our works here or anymore.

In summary, we found that RBM24 interacts with RPL3 and regulates RPL3-eIF6 interaction, which provides a possible explanation for 80S assembly inhibition induced by RBM24.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture and Transfection

293T cells (kindly provided by Prof. Hongbing Shu) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (CellMax, CGM314.05) supplemented with 2 mM of Ala-Gln (OKA, D10184, 0.2 μm PES filtered), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (CellMax, SA211.02) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Antibiotics were not incorporated unless otherwise stated. Plasmids were transfected into cells using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, L3000015) or Lipo8000 (Beyotime, C0533) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

4.2. Plasmids

pcDNA3.1 (-) and a panel of Luciferase reporter plasmids were kindly provided by Prof. Hongbing Shu. lentiCRISPRv2 originally from prof. Feng Zhang's lab [

42] was also kindly provided by Prof. Hongbing Shu. pET28a (+) was kindly provided by Prof. Haibo Jia. Other plasmids were described in "Supplementary_File_S1_plasmids_sequences.7z" and deposited to Addgene (available at

https://www.addgene.org/browse/article/28243088/). For all plasmids constructed in this work, the inserts or regions modified during molecular cloning were validated by sanger sequencing (Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.). Plasmids backbone and/or unmodified regions were not sequenced. Molecular cloning method used in this work was seamless cloning (Bio Basic Inc., B632219), except for that containing inserts with or near Gibson incompatible sequences such as 6xHis tag. Plasmids with modifications near Gibson incompatible sequences were constructed through traditional or golden gate cloning method. Primers, oligos, Enzymes and

E. coli strains were described in "Supplementary_File_S2_Oligos_Antibodies_Enzymes_and_Strains.xls".

4.3. Recombinant Proteins

Glutathione S-Transferase (GST) (Bio Basic Inc., D610271) and GST-eIF6 (Proteintech, Ag0324) were purchased from commercial sources; other recombinant proteins were expressed and purified as described below. Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells were transformed with the expressing plasmids of each protein respectively. A positive monocolony was inoculated into 25 mL of LB medium containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin and grown at 37°C, 250 rpm in a shaker for 4 hours. Cells were then induced with 0.4 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 16 hours at 23~30°C, 180 rpm and were then harvested by centrifuge and resuspended in 1.7 mL low imidazole buffer (300 mM NaCl, 50 mM TRIS (pH 8.0), 0.05% ProClean 300 (Beyotime, ST853), 20% glycerol, and 10 mM imidazole) with 0.4% Nonidet P-40, 0.07% β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME), 0.25 mM phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and 1 tablet per 50 mL cOmplete™ EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche, 04 693 132 001). Next, the cells were lysed by adding 51 μL of 20% Octyl β-D-1-thioglucopyranoside (OTG) (Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology, S11173, Cas No. 85618-21-9) and rotating vertically at 23~30°C for 0.5~1 hours. The lysate was clarified by centrifuge and filtration through a 0.22 μm PES filter. The supernatant was loaded onto a 2.0 mL tube containing 0.2 ml (bed volume) 10 mM imidazole balanced Ni-NTA HP agarose (Henghuibio, HA-0711) and rotated vertically at 4°C for 1~16 hours. The supernatant and beads were then loaded into a minispin empty column (Beyotime, FCL108), and washed sequentially with 10 mM and 40 mM imidazole buffer (600 μL X2 and 600 μL X5, respectively) by centrifuge at 100 xg, 1 min. For recombinant RBM24 protein, additionally washed with 100 mM imidazole buffer (600 μL X2). The protein was eluted by adding 180 μL of 500 mM (or 800 mM for RBM24) imidazole buffer, rotating vertically at 37°C for 15 min, and centrifuging at 700 xg, 2 min. The 180 μL eluent was loaded onto a minispin column containing 600 μL bed volume of RNA binding buffer (high potassium) (240 mM KCl, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.0~7.6), 5 mM MgCl2, 20% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% IPEGAL CA-630) intensively pre-equilibrated Sephadex G-50, incubated at 23~30°C for 2~5 min, centrifuged at 700 xg, 2 min, quantified through a modified Bradford method [43-45] and stored at -80°C. For recombinant proteins with molecular weight (M.W.) < 30 kDa, Sephadex G-25 was used instead of Sephadex G-50. The "μg" values measured by modified Bradford method were converted to "pmol" and further validated (and calibrated if necessary) by western blot densitometry analysis.

4.4. 28.S Degradation Assay and Urea-Agarose Gel Electrophoresis

293T cells were lysed with translating ribosome affinity purification (TRAP) lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.0~7.6, 150 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5% CHAPS, 1 mM DTT, 100 U/mL rRNasin® (Promega, N2515) and cOmplete cocktail; RVC and cyclohexmide was not incorporated.) and filtered through a 0.45 μm PES filter. The lysate containing 28S rRNA was treated by adding 1 μL/mL micrococcal nuclease (NEB, M0247S) and 0.75 mM CaCl2 and incubating at 25°C. The degradation reactions were terminated by 3 mM EGTA at 15 min, 30 min, 45 min, 60 min, 90 min, 24 h. The total RNA was extracted with NucleoZol (MACHEREY-NAGEL, 740404) following the manufacturer's instructions and dissolved in 2X miRNA Deionized Formamide Gel Loading Buffer (Sangon, B548651).

3% urea-agarose gel was prepared with 1 X TAE containing 4 M urea, boiled by microwaving, added GelRed, and solidified at 4°C (The gel did NOT solidify at 25°C). The RNA samples were incubated at 80°C for 5 min and cooled immediately on ice for 5 min, loaded into gel, and electrophoresed at 40~60 V for 2~5 h in 1 X TAE (with 4 M urea). To prevent gel melting during electrophoresis, the horizon electrophoresis tank was immersed in ice-water bath to the same height of the buffer inside the tank. The gel was then imaged in a Bio-Rad GelDoc imager, and analyzed with ImageJ [

46].

4.5. In vitro Transcription

The DNA templates for in vitro transcription were produced by PCR or restriction enzyme digestion as previously described [

13]. RNA fragments were then generated by in vitro transcription of these DNA templates with a ScriptMAX® Thermo T7 Transcription Kit (Toyobo, TSK-101) at 42°C for 4h, or 50°C for 2h if the templates were high GC. Biotin-16-UTP (Roche, 11388908910) or DIG-11-UTP (Jena Bioscience, NU-821-DIGX) was added to the reaction as required to produce labeled RNA. These RNA fragments were then digested with TURBO™ DNase (Ambion®, AM2238) at 37°C for 30 min, purified with NucleoZol and dissolved in appropriate buffer.

4.6. Western Blot, Co-Immunoprecipitation and IP-MS Analyses

The procedure for Western blotting and co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) was the same as previously described [

47] with certain exceptions described below. For RPL3 and its fragments that exhibited extremely poor PVDF binding in Towbin system, an adopted [

48,

49] and modified procedure for electrical blotting was utilized: the gel containing RPL3 fragments was blotted in 1X TAE buffer supplemented with 0.02% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 10% isopropyl alcohol (IPA) at 400 mA for 0.5~1 hours. For blots involves Strep II or Twin Strep tag, 0.5 % crude ovalbumin (Sigma, A5253), which theoretically containing avidin according to the manufacturer's technical supports, was used instead of 5% skimmed milk. Reprobing was performed as described [

50,

51] if necessary. Antibodies and streptavidin variants were listed in "Supplementary_File_S2_Oligos_Antibodies_Enzymes_and_Strains.xls". For IP-MS, the IP procedure was the same as described of the corresponding IP-WB in the results, with 5X amount of beads, antibodies and lysates. The beads for IP-MS were additionally washed with PBS for 3 times and send to a IP-MS service provider (SpecAlly Life Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan).

4.7. Twin Strep Tag Pulldown and GST Pulldown

For Twin Strep tag pulldown, 50 pmol of each combination of recombinant proteins was mixed and incubated in 220 μL Basic IP Buffer (50 mM TRIS, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with 2mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.1 mM PMSF, 1 tablet per 50 mL cOmplete Cocktail at 30°C for 30 min. 5% Input was taken at this time point, incubated at 95°C for 10 min with 2x Laemmli buffer, and stored at -80°C. MagStrep "type3" XT beads (IBA LifeSciences, 2-4090-002) were washed twice with Basic IP Buffer, resuspended in 100 μL Basic IP Buffer (with DTT, PMSF and cOmplete) per 20 μL initial beads, and aliquoted. The aforementioned protein mixtures were then added to the beads and rotated vertically at 26~30°C for 2~4 hours. The beads were washed 7 times with Basic IP Buffer (with DTT and PMSF, without cOmplete) by magnetic separation, incubated at 95°C for 10 min with 2x Laemmli buffer, and subjected to western blotting together with the 5% input aforementioned. For GST pulldown, the beads used were GST-Sefinose Resin 4FF (Bio Basic Inc., C600031) and the washing step was performed by centrifuging at 2000 xg, 1min. Other procedures were the same.

4.8. Endogenous Tagging of RPL3

Endogenous tagging (CRISPR/cas9 mediated Knock-in) of RPL3 in 293T cells was performed through an adopted [

52,

53] and modified method. Cas9 gRNAs were designed with E-CRISP [

54]. Two Cas9-sgRNA plasmids and one single strand oligo donor nucleotides (ssODN) were transiently co-transfected into SCR7 and RS-1 treated 293T cells. Monoclonal cells with homozygous C-terminal Twin Strep tagged RPL3 were isolated by limiting dilution, identified by colony PCR, and validated by sanger sequencing and western blot. The monoclone was named 3A8 because it was from the A8 well of the 3rd 96 well plate we screened. Details were included in "Supplementary_File_S5_Supplementary_Methods.doc".

4.9. Ribosome Affinity Capture and Quantification Mass Spectrometry

The 3A8 cells were lysed with translating ribosome affinity purification (TRAP) lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.0~7.6, 150 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5% CHAPS, 1 mM DTT, 100 U/mL rRNasin® and cOmplete cocktail; RVC and cyclohexmide was not incorporated.) and filtered through a 0.45 μm PES filter. Endogenous mRNA was removed by adding 1 μL/mL micrococcal nuclease (NEB, M0247S) and 0.75 mM CaCl

2 and incubating at 25°C for 15 min. The reaction was then terminated by adding EGTA to 3 mM. 50 pmol of HCV IRES (JFH1 1~360) RNA and/or (0.5 μg/mL poly[I:C] + 2 mM ATP) were added to 1600 μg total protein containing nuclease treated lysates. The mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 30 min. Strep-Tactin®XT 4Flow® high capacity (IBA LifeSciences, 2-5030-002) or Sepharose 4FF beads were wash twice with TRAP wash buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.0~7.6, 150 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1% CHAPS, 0.2 mM DTT, 10 U/mL rRNasin®, 400 μM RVC and cOmplete cocktail; cyclohexmide was not incorporated.). The beads were blocked and RNase removal [

55] by resuspending in TRAP wash buffer supplemented with 1% BSA (molecular biology grade) and 20 mM DTT and rotating at 37°C for 1 hour. The treated beads were washed 5 times with TRAP wash buffer and aliquoted. The aforementioned lysates were then added to the beads in a ratio of 800 μg total protein to 40 μL initial beads, and rotated at 30°C for 4 hours. The beads were washed in TRAP wash buffer by rotating at 30°C for 5 min and centrifuging at 2000 g, 1min, 30°C. The beads were then incubated at 95°C for 10 min with 2x Laemmli buffer, and subjected to western blotting. For quantification mass spectrometry (Data-Independent Acquisition, DIA), the procedure was the same but with 5X amount of beads, recombinant proteins, RNA, reagents and lysates. The beads were washed additionally with RNase-free PBS and send to a DIA service provider (SpecAlly Life Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan). The quantification data were normalized using the protein sequence of a streptavidin variant (PDB ID: 6QBB[

56]) and then presented as fold change of every protein quantified on the beads from RBM24 transfected group vs. EGFP transfected group.

4.10. PDB Files Visualizing

Structure files (PDB ID: 6ZMI [

32] and 6QKL [

36]) were downloaded from RCSB PDB database [

57,

58]. The molecules of interest were extracted from the PDB files with Swiss-PdbViewer [

59]. The intermolecular contacting residues in 6Å and 4Å range were labeled with "Residues close to an other chain" in the "select" menu of Swiss-PdbViewer [

59]. The 3D models were visualized with RasMol 2.7.5 [

60].

4.11. Peptide Competition Assay

Flag (DYKDDDDK) and

Homo sapiens RPL3 64-70 (GSKVNKK) were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. The peptides were resolved in water to the concentration of 50 μg/μL and subjected to in vitro translation as described [

13]. The amount of RNA, peptides and proteins used in successful attemptions were: 1 μg of HCV IRES fused luciferase RNA (JFH1-1~398-Luc) per 200 μL of initial rabbit reticulocyte lysate (RRL, Promega, L4960), 0.5 mg of peptides (DYKDDDDK or GSKVNKK, in 10 μL RNase-free water) per 100 μL initial RRL, 50 pmol of recombinant proteins (RBM24 or BSA (NEB, B9001S), in 15 μL RNA binding buffer) per 50 μL initial RRL. The assay mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 0.5 h in a Thermal Cycler T100 with 42°C hot lid. After incubated, the assay mixtures were diluted 5X in PBS, mixed with same volume (after diluted) of Steady-Glo (Promega, E2520) and incubated at 23~30°C for 5 min, and measured with a BLT Lux-T020 luminometer. Translation inhibition activities of RBM24 were defined as the relative luminescence unit (RLU) of RBM24/BSA.

4.12. RNA Immunoprecipitation Followed by High Throughput Sequencing

Total RNA from three 10cm dish of 293T cells were extracted with NucleoZol and fragmented with NEBNext® Magnesium RNA Fragmentation Module (E6150) at 94°C for 5 min. The fragmented total RNA was then precipitated by adding RNase free NaAc and Ethanol according to E6150's manual. The fragmented total RNA was resolved in RNA folding buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.0~7.6, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2), refolding by heating at 65°C for 2 min followed by natural cooling at 23~30°C and aliqouted equally into 3 1.5 mL tubes. 400 μL RNA binding buffer (high potassium) containing 200 pmol of recombinant Flag-RBM24 was then added to each tube and incubated at 30 °C for 30 min. A+G beads precharged with anti-Flag antibody and washed 4X with RNA binding buffer was then added to these tubes and rotated at 23~30°C for additional 2~4 h. The beads were washed 5X with RNA binding buffer and send to a high throughput sequencing service provider (Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.). The RNA co-precipitated was eluted by vortex rigorously in TRIzol as our instruction by the service provider and subjected to high throughput sequencing. The reads mapping to 5' UTR region of transcripts were counted. Reads that cannot mapping to 5' UTR region were excluded.

5. Conclusions

RBM24 enhance RPL3-eIF6 interaction both in transltion complex and in artificial system involves only the three purified proteins without RNAs; RBM24 interact with RPL3 but not with eIF6; RBM24 blocks eIF6 binding to 28S embeded region of RPL3, but not blocks eIF6 binding to known eIF6 contacting region of RPL3 in 80S subunit.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, C.H., G.W. and M.Q.; methodology, C.H.; software, N/A.; validation, C.H., T.Y. and Y.X.; formal analysis, C.H.; investigation, C.H.; resources, S.J., W.X., G.W., M.Q., .; data curation, C.H.; writing—original draft preparation, C.H.; writing—review and editing, C.H., G.W., M.Q.; visualization, C.H.; supervision, M.Q.; project administration, M.Q.; funding acquisition, W.X. and M.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof. Hongbing Shu and Prof. Ding Ma for the material and technical supports for the start-up of our laboratory, and to Prof. Peng Gong and Prof. Haibo Jia for the technical supports for prokaryotic expression and purification of recombinant proteins. We are grateful to Dr. Florian Heigwer (E-CRISP) for the technical supports for CRISPR/cas9 gRNA design.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lin, Y.; May, G.E.; Kready, H.; Nazzaro, L.; Mao, M.; Spealman, P.; Creeger, Y.; McManus, C.J. Impacts of uORF codon identity and position on translation regulation. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, 9358-9367. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz681. [CrossRef]

- Sonenberg, N.; Hinnebusch, A.G. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell 2009, 136, 731-745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.042. [CrossRef]

- Ryoo, H.D.; Vasudevan, D. Two distinct nodes of translational inhibition in the Integrated Stress Response. BMB Rep 2017, 50, 539-545. https://doi.org/10.5483/bmbrep.2017.50.11.157. [CrossRef]

- Hershey, J.W.B.; Sonenberg, N.; Mathews, M.B. Principles of Translational Control. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2019, 11. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a032607. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Qian, Y.; Xu, E.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X. Rbm24, an RNA-binding protein and a target of p53, regulates p21 expression via mRNA stability. J Biol Chem 2014, 289, 3164-3175. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M113.524413. [CrossRef]

- Xu, E.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, Y.; Cho, S.J.; Chen, X. RNA-binding protein RBM24 regulates p63 expression via mRNA stability. Mol Cancer Res 2014, 12, 359-369. https://doi.org/10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0526. [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Lu, T.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Kong, S.H.; Shi, D.L. Rbm24 controls poly(A) tail length and translation efficiency of crystallin mRNAs in the lens via cytoplasmic polyadenylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 7245-7254. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1917922117. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Hung, L.H.; Licht, T.; Kostin, S.; Looso, M.; Khrameeva, E.; Bindereif, A.; Schneider, A.; Braun, T. RBM24 is a major regulator of muscle-specific alternative splicing. Dev Cell 2014, 31, 87-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2014.08.025. [CrossRef]

- Ohe, K.; Yoshida, M.; Nakano-Kobayashi, A.; Hosokawa, M.; Sako, Y.; Sakuma, M.; Okuno, Y.; Usui, T.; Ninomiya, K.; Nojima, T., et al. RBM24 promotes U1 snRNP recognition of the mutated 5' splice site in the IKBKAP gene of familial dysautonomia. RNA 2017, 23, 1393-1403. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.059428.116. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Lin, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.G.; Fu, W.; Guo, L.Y.; Pan, L.; Kong, X.; Zhang, M.K.; Lu, Y.H., et al. Rbm24 Regulates Alternative Splicing Switch in Embryonic Stem Cell Cardiac Lineage Differentiation. Stem Cells 2016, 34, 1776-1789. https://doi.org/10.1002/stem.2366. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Kong, X.; Zhang, M.; Yang, X.; Xu, X. RNA binding protein 24 deletion disrupts global alternative splicing and causes dilated cardiomyopathy. Protein Cell 2019, 10, 405-416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13238-018-0578-8. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, E.; Mohibi, S.; de Anda, D.M.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X. Rbm24, a target of p53, is necessary for proper expression of p53 and heart development. Cell Death Differ 2018, 25, 1118-1130. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-017-0029-8. [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Zhao, K.; Yao, Y.; Guo, J.; Gao, X.; Yang, Q.; Guo, M.; Zhu, W.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C., et al. RNA binding protein 24 regulates the translation and replication of hepatitis C virus. Protein Cell 2018, 9, 930-944. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13238-018-0507-x. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Yang, B.; Cao, H.; Zhao, K.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Pei, R.; Chen, J., et al. RBM24 stabilizes hepatitis B virus pregenomic RNA but inhibits core protein translation by targeting the terminal redundancy sequence. Emerg Microbes Infect 2018, 7, 86. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41426-018-0091-4. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Sun, H.; Chen, Y.; Tian, L.; Huang, D.; Liu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wen, Z.; Yang, B., et al. RBM24 inhibits the translation of SARS-CoV-2 polyproteins by targeting the 5'-untranslated region. Antiviral Res 2023, 209, 105478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2022.105478. [CrossRef]

- Godet, A.C.; David, F.; Hantelys, F.; Tatin, F.; Lacazette, E.; Garmy-Susini, B.; Prats, A.C. IRES Trans-Acting Factors, Key Actors of the Stress Response. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20040924. [CrossRef]

- Kieft, J.S. Viral IRES RNA structures and ribosome interactions. Trends Biochem Sci 2008, 33, 274-283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2008.04.007. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Querol-Audi, J.; Mortimer, S.A.; Arias-Palomo, E.; Doudna, J.A.; Nogales, E.; Cate, J.H. Two RNA-binding motifs in eIF3 direct HCV IRES-dependent translation. Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41, 7512-7521. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkt510. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, C.S.; Doudna, J.A. Structural and mechanistic insights into hepatitis C viral translation initiation. Nat Rev Microbiol 2007, 5, 29-38. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro1558. [CrossRef]

- Lukavsky, P.J. Structure and function of HCV IRES domains. Virus Res 2009, 139, 166-171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2008.06.004. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H.; Unbehaun, A.; Loerke, J.; Behrmann, E.; Collier, M.; Burger, J.; Mielke, T.; Spahn, C.M. Structure of the mammalian 80S initiation complex with initiation factor 5B on HCV-IRES RNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2014, 21, 721-727. https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2859. [CrossRef]

- Dmitriev, S.E.; Terenin, I.M.; Andreev, D.E.; Ivanov, P.A.; Dunaevsky, J.E.; Merrick, W.C.; Shatsky, I.N. GTP-independent tRNA delivery to the ribosomal P-site by a novel eukaryotic translation factor. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 26779-26787. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M110.119693. [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, Z.A.; Oguro, A.; Nakamura, Y.; Kieft, J.S. Translation initiation by the hepatitis C virus IRES requires eIF1A and ribosomal complex remodeling. Elife 2016, 5. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.21198. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Almela, E.; Williams, H.; Sanz, M.A.; Carrasco, L. The Initiation Factors eIF2, eIF2A, eIF2D, eIF4A, and eIF4G Are Not Involved in Translation Driven by Hepatitis C Virus IRES in Human Cells. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 207. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00207. [CrossRef]

- Terenin, I.M.; Dmitriev, S.E.; Andreev, D.E.; Shatsky, I.N. Eukaryotic translation initiation machinery can operate in a bacterial-like mode without eIF2. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2008, 15, 836-841. https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.1445. [CrossRef]

- Niepmann, M.; Gerresheim, G.K. Hepatitis C Virus Translation Regulation. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21072328. [CrossRef]

- Meskauskas, A.; Dinman, J.D. Ribosomal protein L3: gatekeeper to the A site. Mol Cell 2007, 25, 877-888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.015. [CrossRef]

- Ceci, M.; Gaviraghi, C.; Gorrini, C.; Sala, L.A.; Offenhauser, N.; Marchisio, P.C.; Biffo, S. Release of eIF6 (p27BBP) from the 60S subunit allows 80S ribosome assembly. Nature 2003, 426, 579-584. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02160. [CrossRef]

- Jaako, P.; Faille, A.; Tan, S.; Wong, C.C.; Escudero-Urquijo, N.; Castro-Hartmann, P.; Wright, P.; Hilcenko, C.; Adams, D.J.; Warren, A.J. eIF6 rebinding dynamically couples ribosome maturation and translation. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 1562. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29214-7. [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, D.A.; Violin, J.D.; Newton, A.C.; Tsien, R.Y. Partitioning of lipid-modified monomeric GFPs into membrane microdomains of live cells. Science 2002, 296, 913-916. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1068539. [CrossRef]

- consortium, P.D.-K. PDBe-KB: collaboratively defining the biological context of structural data. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, D534-D542. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab988. [CrossRef]

- Thoms, M.; Buschauer, R.; Ameismeier, M.; Koepke, L.; Denk, T.; Hirschenberger, M.; Kratzat, H.; Hayn, M.; Mackens-Kiani, T.; Cheng, J., et al. Structural basis for translational shutdown and immune evasion by the Nsp1 protein of SARS-CoV-2. Science 2020, 369, 1249-1255. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abc8665. [CrossRef]

- Valbuena, F.M.; Fitzgerald, I.; Strack, R.L.; Andruska, N.; Smith, L.; Glick, B.S. A photostable monomeric superfolder green fluorescent protein. Traffic 2020, 21, 534-544. https://doi.org/10.1111/tra.12737. [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Pagliara, V.; Albano, F.; Esposito, D.; Sagar, V.; Loreni, F.; Irace, C.; Santamaria, R.; Russo, G. Regulatory role of rpL3 in cell response to nucleolar stress induced by Act D in tumor cells lacking functional p53. Cell Cycle 2016, 15, 41-51. https://doi.org/10.1080/15384101.2015.1120926. [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Russo, G. Ribosomal Proteins Control or Bypass p53 during Nucleolar Stress. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18010140. [CrossRef]

- Weis, F.; Giudice, E.; Churcher, M.; Jin, L.; Hilcenko, C.; Wong, C.C.; Traynor, D.; Kay, R.R.; Warren, A.J. Mechanism of eIF6 release from the nascent 60S ribosomal subunit. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2015, 22, 914-919. https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.3112. [CrossRef]

- Uhlen, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallstrom, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, A.; Kampf, C.; Sjostedt, E.; Asplund, A., et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015, 347, 1260419. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1260419. [CrossRef]

- Milenkovic, I.; Santos Vieira, H.G.; Lucas, M.C.; Ruiz-Orera, J.; Patone, G.; Kesteven, S.; Wu, J.; Feneley, M.; Espadas, G.; Sabido, E., et al. Dynamic interplay between RPL3- and RPL3L-containing ribosomes modulates mitochondrial activity in the mammalian heart. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, 5301-5324. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad121. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.H.; Wang, C.Y.; Tsai, H.C.; Liu, C.T. Human IRES Atlas: an integrative platform for studying IRES-driven translational regulation in humans. Database (Oxford) 2021, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/database/baab025. [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, J.S.; Agarwala, R. COBALT: constraint-based alignment tool for multiple protein sequences. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 1073-1079. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btm076. [CrossRef]

- Gandin, V.; Miluzio, A.; Barbieri, A.M.; Beugnet, A.; Kiyokawa, H.; Marchisio, P.C.; Biffo, S. Eukaryotic initiation factor 6 is rate-limiting in translation, growth and transformation. Nature 2008, 455, 684-688. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07267. [CrossRef]

- Sanjana, N.E.; Shalem, O.; Zhang, F. Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nat Methods 2014, 11, 783-784. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3047. [CrossRef]

- Ku, H.K.; Lim, H.M.; Oh, K.H.; Yang, H.J.; Jeong, J.S.; Kim, S.K. Interpretation of protein quantitation using the Bradford assay: comparison with two calculation models. Anal Biochem 2013, 434, 178-180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2012.10.045. [CrossRef]

- Rabilloud, T. Optimization of the cydex blue assay: A one-step colorimetric protein assay using cyclodextrins and compatible with detergents and reducers. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0195755. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195755. [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Xue, H.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, H.; Jin, J.; Wang, Q. Increasing the amount of phosphoric acid enhances the suitability of Bradford assay for proteomic research. Electrophoresis 2019, 40, 1107-1112. https://doi.org/10.1002/elps.201800430. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 2012, 9, 671-675. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2089. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Pei, R.; Guo, M.; Han, Q.; Lai, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, M.; Chen, X. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 gamma is involved in hepatitis C virus replication and assembly. J Virol 2012, 86, 13025-13037. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01785-12. [CrossRef]

- Bolt, M.W.; Mahoney, P.A. High-efficiency blotting of proteins of diverse sizes following sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Anal Biochem 1997, 247, 185-192. https://doi.org/10.1006/abio.1997.2061. [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, M.A. Electrotransfer of proteins in an environmentally friendly methanol-free transfer buffer. Anal Biochem 2008, 373, 377-379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2007.08.007. [CrossRef]

- Yeung, Y.G.; Stanley, E.R. A solution for stripping antibodies from polyvinylidene fluoride immunoblots for multiple reprobing. Anal Biochem 2009, 389, 89-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2009.03.017. [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Cui, Y.; Helbing, D.L. Inactivation of Horseradish Peroxidase by Acid for Sequential Chemiluminescent Western Blot. Biotechnol J 2020, 15, e1900397. https://doi.org/10.1002/biot.201900397. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimi, K.; Kunihiro, Y.; Kaneko, T.; Nagahora, H.; Voigt, B.; Mashimo, T. ssODN-mediated knock-in with CRISPR-Cas for large genomic regions in zygotes. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 10431. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10431. [CrossRef]

- Nagahora, H.T., JP) METHOD FOR PREPARING LONG-CHAIN SINGLE-STRANDED DNA. 2019.

- Heigwer, F.; Kerr, G.; Boutros, M. E-CRISP: fast CRISPR target site identification. Nat Methods 2014, 11, 122-123. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2812. [CrossRef]

- Pasloske, B.L.A., TX), Wu, William (Austin, TX) Method and reagents for inactivating ribonucleases RNase A, RNase I and RNase T1. 2004.

- Schmidt, T.G.M.; Eichinger, A.; Schneider, M.; Bonet, L.; Carl, U.; Karthaus, D.; Theobald, I.; Skerra, A. The Role of Changing Loop Conformations in Streptavidin Versions Engineered for High-affinity Binding of the Strep-tag II Peptide. J Mol Biol 2021, 433, 166893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2021.166893. [CrossRef]

- Burley, S.K.; Bhikadiya, C.; Bi, C.; Bittrich, S.; Chao, H.; Chen, L.; Craig, P.A.; Crichlow, G.V.; Dalenberg, K.; Duarte, J.M., et al. RCSB Protein Data Bank (RCSB.org): delivery of experimentally-determined PDB structures alongside one million computed structure models of proteins from artificial intelligence/machine learning. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, D488-D508. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac1077. [CrossRef]

- Berman, H.M.; Westbrook, J.; Feng, Z.; Gilliland, G.; Bhat, T.N.; Weissig, H.; Shindyalov, I.N.; Bourne, P.E. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res 2000, 28, 235-242. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [CrossRef]

- Guex, N.; Peitsch, M.C. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 1997, 18, 2714-2723. https://doi.org/10.1002/elps.1150181505. [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, H.J. Recent changes to RasMol, recombining the variants. Trends Biochem Sci 2000, 25, 453-455. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01606-6. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Chen, T.; Wu, S.; Yang, C.; Bai, M.; Shu, K.; Li, K.; Zhang, G.; Jin, Z.; He, F., et al. iProX: an integrated proteome resource. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, D1211-D1217. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky869. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Ma, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, N.; Lu, Y.; Fu, Y.; Yang, C.; Li, M.; Wu, S., et al. iProX in 2021: connecting proteomics data sharing with big data. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, D1522-D1527. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab1081. [CrossRef]

- Sayers, E.W.; Bolton, E.E.; Brister, J.R.; Canese, K.; Chan, J.; Comeau, D.C.; Connor, R.; Funk, K.; Kelly, C.; Kim, S., et al. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, D20-D26. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab1112. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

IP-MS with RBM24 as bait protein. (A) GO Biological Process enrichment. (B) KEGG pathway enrichment. (C) MCC subnetwork analysis.

Figure 1.

IP-MS with RBM24 as bait protein. (A) GO Biological Process enrichment. (B) KEGG pathway enrichment. (C) MCC subnetwork analysis.

Figure 2.

RBM24 interacts with RPL3. (A) 293T cells transfected with pcDNA3.1-Flag-RBM24 were lysed and subjected to IP with anti-Flag antibody (IP:Flag) with normal mouse IgG (IP:IgG) as control, the endogenous targets indicated were detected by WB respectively. (B) Lowering the "input" from 5% to 1% of that panel A. (C) Recombinant RPL3 and RBM24 proteins were mixed and subjected to Strep tag pulldown by MagStrep "type3" XT beads (Pulldown:Strep), RPL3 was C-ter Twin Strep tagged and RBM24 was N-ter Flag tagged. Recombinant mEGFP (A206K) protein with C-ter Twin Strep tag (mEGFP) was incorporated as control.

Figure 2.

RBM24 interacts with RPL3. (A) 293T cells transfected with pcDNA3.1-Flag-RBM24 were lysed and subjected to IP with anti-Flag antibody (IP:Flag) with normal mouse IgG (IP:IgG) as control, the endogenous targets indicated were detected by WB respectively. (B) Lowering the "input" from 5% to 1% of that panel A. (C) Recombinant RPL3 and RBM24 proteins were mixed and subjected to Strep tag pulldown by MagStrep "type3" XT beads (Pulldown:Strep), RPL3 was C-ter Twin Strep tagged and RBM24 was N-ter Flag tagged. Recombinant mEGFP (A206K) protein with C-ter Twin Strep tag (mEGFP) was incorporated as control.

Figure 3.

RBM24 interacts with truncated RPL3 fragments. (A) Diagram of truncated RPL3 fragments. The dot lines indicate truncating sites, which are at regions not contacting other molecules acording to PDBe-KB. (B) Strep tag pulldown using recombinant RBM24 protein and RPL3 fragments (1~77, 72~197, 191~307 and 299~398) shown in panel A. RBM24 was flag tagged, RPL3 fragments were mEGFP and Twin Strep tagged. (C) RPL3 truncates according to structure. Upper panel indicated the embedded (1~41 in cyan and 212~285 in yellow) and exposed (Δ1~34, Δ215~284 in orange) regions of RPL3, lower are diagram of RPL3 fragments corresponding to these regions. (D) Strep tag pulldown using recombinant RBM24 protein and RPL3 fragments (1~41, 212~285, Δ1~34, Δ215~284) shown in panel C, RBM24 was Flag tagged, all RPL3 fragments were Twin Strep tagged, 1~41 and 212~285 fragments were mEGFP tagged, Δ1~34, Δ215~284 was indicated as Δ34, Δ215 for short and not mEGFP tagged.

Figure 3.

RBM24 interacts with truncated RPL3 fragments. (A) Diagram of truncated RPL3 fragments. The dot lines indicate truncating sites, which are at regions not contacting other molecules acording to PDBe-KB. (B) Strep tag pulldown using recombinant RBM24 protein and RPL3 fragments (1~77, 72~197, 191~307 and 299~398) shown in panel A. RBM24 was flag tagged, RPL3 fragments were mEGFP and Twin Strep tagged. (C) RPL3 truncates according to structure. Upper panel indicated the embedded (1~41 in cyan and 212~285 in yellow) and exposed (Δ1~34, Δ215~284 in orange) regions of RPL3, lower are diagram of RPL3 fragments corresponding to these regions. (D) Strep tag pulldown using recombinant RBM24 protein and RPL3 fragments (1~41, 212~285, Δ1~34, Δ215~284) shown in panel C, RBM24 was Flag tagged, all RPL3 fragments were Twin Strep tagged, 1~41 and 212~285 fragments were mEGFP tagged, Δ1~34, Δ215~284 was indicated as Δ34, Δ215 for short and not mEGFP tagged.

Figure 5.

28S MNase resistance assay. (A) 293T cells transfected with pcDNA3.1-Flag-RBM24 (RBM24) or pcDNA3.1-msEGFP1.8 (EGFP) were lysed, treated with MNase for the indicated time periods and subjected to 4M urea-agarose electrophoresis. (B) Gray density analysis of the 28S bands in panel A.

Figure 5.

28S MNase resistance assay. (A) 293T cells transfected with pcDNA3.1-Flag-RBM24 (RBM24) or pcDNA3.1-msEGFP1.8 (EGFP) were lysed, treated with MNase for the indicated time periods and subjected to 4M urea-agarose electrophoresis. (B) Gray density analysis of the 28S bands in panel A.

Figure 6.

Ribosome affinity capture followed by quantification mass spectrometry. (A) Schematic diagram of ribosome affinity capture. Twin strep tag was homozygous knock-in at C terminal of RPL3. The whole translation machinery was captured. (B) Fold change of some selected proteins associated with large subunit (in ribosome affinity capture assay, RPL3 as bait) in RBM24 transfected group vs EGFP transfected group. X axis, gene name of the selected proteins. Y axis, fold change, 1 for not changed, >1 for increased 60S associated in RBM24 group, <1 for decreased 60S associated in RBM24 group. Dash line, fold change of bait protein RPL3 (endogenous affinity tag knocked-in, ~0.882, not significant changed between two groups). *, 60S association significant (t-test) changed between two groups. ns, 60S association not significant (t-test) changed between two groups.

Figure 6.

Ribosome affinity capture followed by quantification mass spectrometry. (A) Schematic diagram of ribosome affinity capture. Twin strep tag was homozygous knock-in at C terminal of RPL3. The whole translation machinery was captured. (B) Fold change of some selected proteins associated with large subunit (in ribosome affinity capture assay, RPL3 as bait) in RBM24 transfected group vs EGFP transfected group. X axis, gene name of the selected proteins. Y axis, fold change, 1 for not changed, >1 for increased 60S associated in RBM24 group, <1 for decreased 60S associated in RBM24 group. Dash line, fold change of bait protein RPL3 (endogenous affinity tag knocked-in, ~0.882, not significant changed between two groups). *, 60S association significant (t-test) changed between two groups. ns, 60S association not significant (t-test) changed between two groups.

Figure 7.

The interplay of RBM24, RPL3 and eIF6. (A) 3A8 cells (a endogenous RPL3 C-ter Twin Strep tagged 293T monoclone) transfected with pcDNA3.1-Flag-RBM24 (RBM24 +) or pcDNA3.1-msEGFP1.8 (RBM24 -) were lysed and subjected to ribosome affinity capture by Strep-Tactin®XT 4Flow® high capacity beads (Pulldown:Strep). Poly[I:C] was added as indicated to inactivate eIF2α. Sepharose 4FF beads (Pulldown:4FF) were incorporated as "empty beads" control. Endogenous targets were detected by WB respectively. (B) Recombinant GST-eIF6 and Flag-RBM24 proteins were mixed and subjected to GST pulldown by GST-Sefinose Resin 4FF (Pulldown:GSH). Recombinant GST protein (GST) was incorporated as control. (C) 293T cells transfected with pcDNA3.1-Flag-RBM24 were lysed and subjected to IP with anti-Flag antibody (IP:Flag) with normal mouse IgG (IP:IgG) as control, endogenous RPL3, eIF6 and p70 subunit of U1 snRNP (U1p70) were detected by WB respectively. (D) Recombinant RPL3-TwStrep (RPL3) and/or Flag-RBM24 (RBM24) proteins were mixed with GST-eIF6 and subjected to Strep tag pulldown (Pulldown:Strep), Recombinant mEGFP(A206K)-TwStrep (mEGFP) was incorporated as control. (E) 50 pmol of recombinant RPL3-TwStrep (RPL3) and/or different amount (50 pmol as "+" and 200 pmol as "+++") of Flag-RBM24 (RBM24) proteins were mixed with 50 pmol of GST-eIF6 and subjected to Strep tag pulldown (Pulldown:Strep), 50 pmol of recombinant mEGFP(A206K)-TwStrep (mEGFP) was incorporated as control.

Figure 7.

The interplay of RBM24, RPL3 and eIF6. (A) 3A8 cells (a endogenous RPL3 C-ter Twin Strep tagged 293T monoclone) transfected with pcDNA3.1-Flag-RBM24 (RBM24 +) or pcDNA3.1-msEGFP1.8 (RBM24 -) were lysed and subjected to ribosome affinity capture by Strep-Tactin®XT 4Flow® high capacity beads (Pulldown:Strep). Poly[I:C] was added as indicated to inactivate eIF2α. Sepharose 4FF beads (Pulldown:4FF) were incorporated as "empty beads" control. Endogenous targets were detected by WB respectively. (B) Recombinant GST-eIF6 and Flag-RBM24 proteins were mixed and subjected to GST pulldown by GST-Sefinose Resin 4FF (Pulldown:GSH). Recombinant GST protein (GST) was incorporated as control. (C) 293T cells transfected with pcDNA3.1-Flag-RBM24 were lysed and subjected to IP with anti-Flag antibody (IP:Flag) with normal mouse IgG (IP:IgG) as control, endogenous RPL3, eIF6 and p70 subunit of U1 snRNP (U1p70) were detected by WB respectively. (D) Recombinant RPL3-TwStrep (RPL3) and/or Flag-RBM24 (RBM24) proteins were mixed with GST-eIF6 and subjected to Strep tag pulldown (Pulldown:Strep), Recombinant mEGFP(A206K)-TwStrep (mEGFP) was incorporated as control. (E) 50 pmol of recombinant RPL3-TwStrep (RPL3) and/or different amount (50 pmol as "+" and 200 pmol as "+++") of Flag-RBM24 (RBM24) proteins were mixed with 50 pmol of GST-eIF6 and subjected to Strep tag pulldown (Pulldown:Strep), 50 pmol of recombinant mEGFP(A206K)-TwStrep (mEGFP) was incorporated as control.

Figure 8.

The interplay of RBM24 and eIF6 with RPL3 fragments. (A) Residues in RPL3 in close proximity to eIF6. Orange: RPL3; Green: eIF6; Blue: other proteins; White string: 28S rRNA; Red: RPL3-64~71 within 6Å range to eIF6; Yellow: RPL3-53~77 for fusion protein construction. (B) Recombinant RPL3-1~41-mEGFP-TwStrep (1~41) or RPL3-53~77-mEGFP-TwStrep (53~77) proteins were mixed with GST-eIF6 and subjected to Strep tag pulldown (Pulldown:Strep) in the present or absent of Flag-RBM24, Recombinant mEGFP(A206K)-TwStrep (mEGFP) was incorporated as control. (C) Recombinant RPL3-212~285-mEGFP-TwStrep (1~41) protein were mixed with GST-eIF6 and subjected to Strep tag pulldown (Pulldown:Strep) in the present or absent of Flag-RBM24, Recombinant mEGFP(A206K)-TwStrep (mEGFP) was incorporated as control. (D) Recombinant RPL3-1~77-mEGFP-TwStrep (1~77), RPL3-53~77-mEGFP-TwStrep (53~77) and RPL3-1~41-mEGFP-TwStrep (1~41) proteins were mixed with Flag-RBM24 subjected to Strep tag pulldown (Pulldown:Strep) in the absent of GST-eIF6, Recombinant mEGFP(A206K)-TwStrep (mEGFP) was incorporated as control.

Figure 8.

The interplay of RBM24 and eIF6 with RPL3 fragments. (A) Residues in RPL3 in close proximity to eIF6. Orange: RPL3; Green: eIF6; Blue: other proteins; White string: 28S rRNA; Red: RPL3-64~71 within 6Å range to eIF6; Yellow: RPL3-53~77 for fusion protein construction. (B) Recombinant RPL3-1~41-mEGFP-TwStrep (1~41) or RPL3-53~77-mEGFP-TwStrep (53~77) proteins were mixed with GST-eIF6 and subjected to Strep tag pulldown (Pulldown:Strep) in the present or absent of Flag-RBM24, Recombinant mEGFP(A206K)-TwStrep (mEGFP) was incorporated as control. (C) Recombinant RPL3-212~285-mEGFP-TwStrep (1~41) protein were mixed with GST-eIF6 and subjected to Strep tag pulldown (Pulldown:Strep) in the present or absent of Flag-RBM24, Recombinant mEGFP(A206K)-TwStrep (mEGFP) was incorporated as control. (D) Recombinant RPL3-1~77-mEGFP-TwStrep (1~77), RPL3-53~77-mEGFP-TwStrep (53~77) and RPL3-1~41-mEGFP-TwStrep (1~41) proteins were mixed with Flag-RBM24 subjected to Strep tag pulldown (Pulldown:Strep) in the absent of GST-eIF6, Recombinant mEGFP(A206K)-TwStrep (mEGFP) was incorporated as control.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).