1. Introduction.

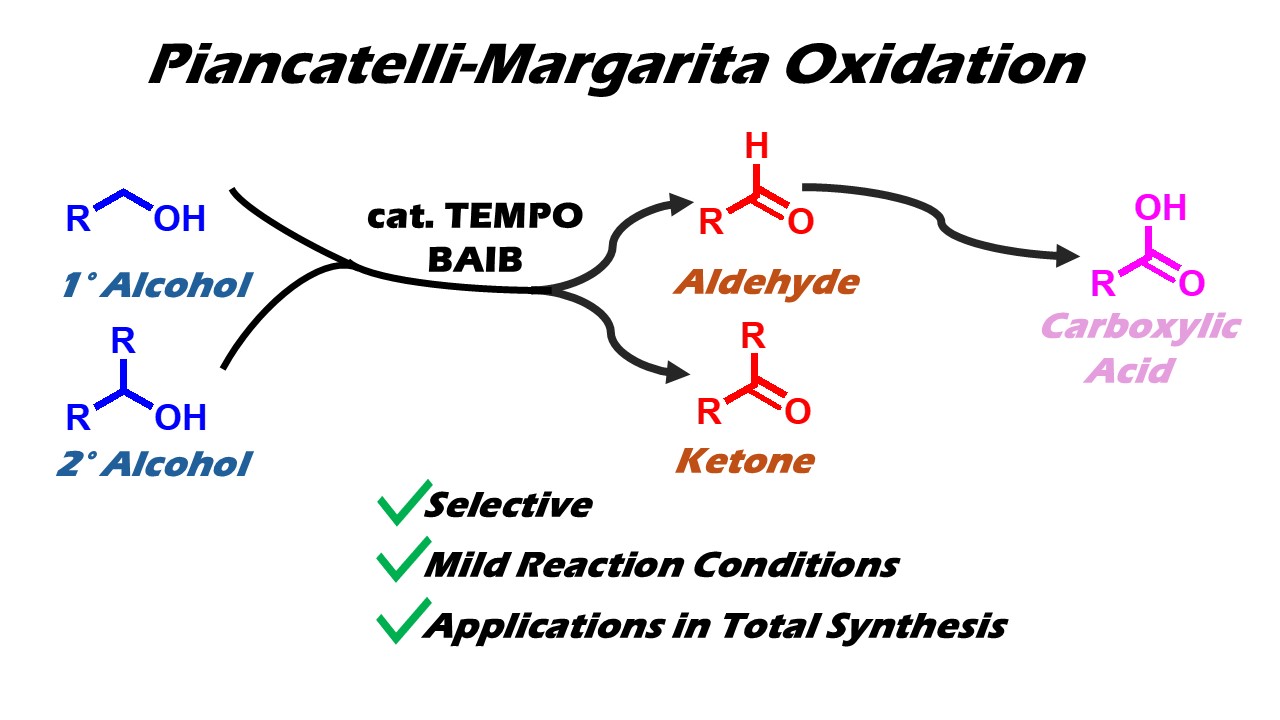

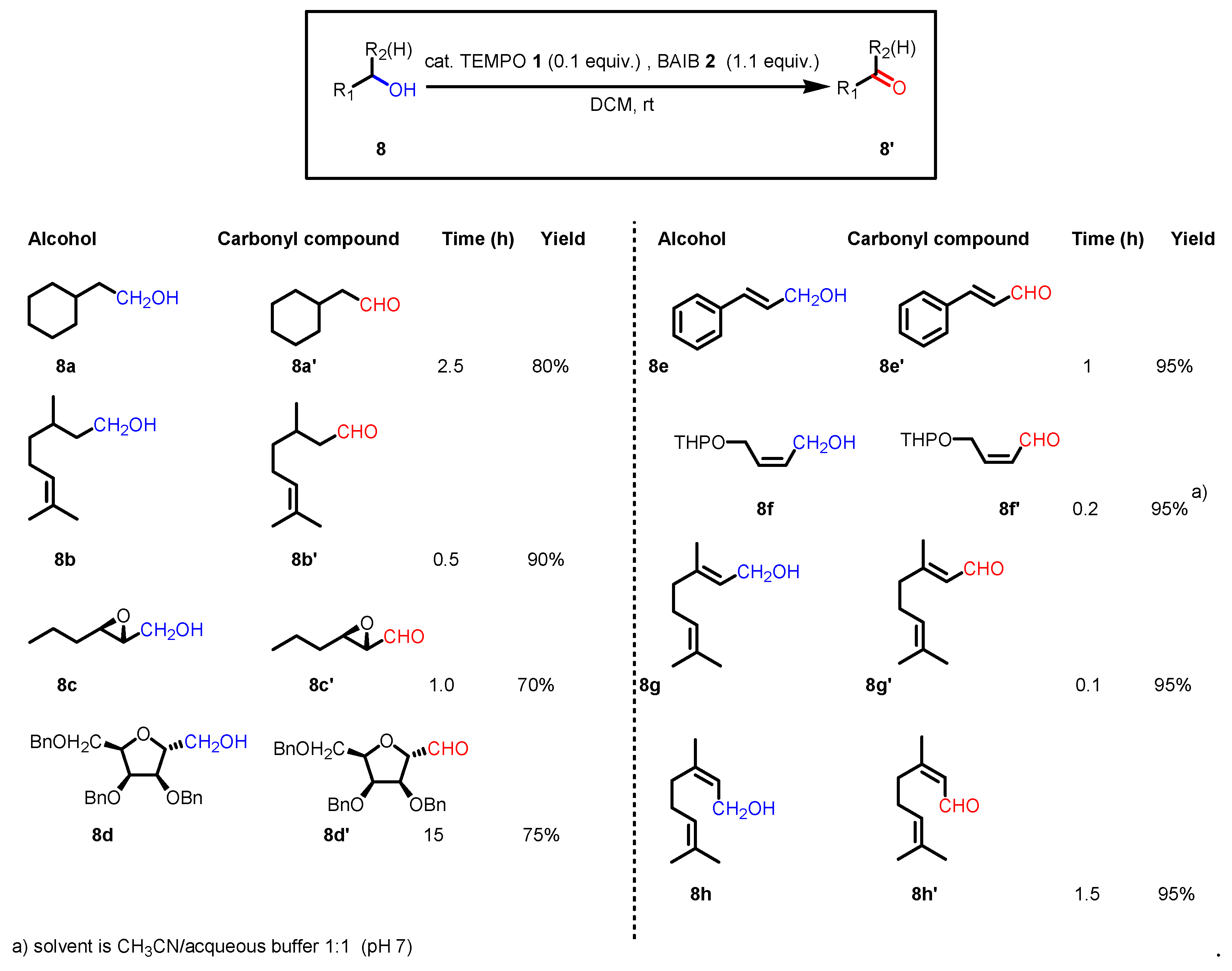

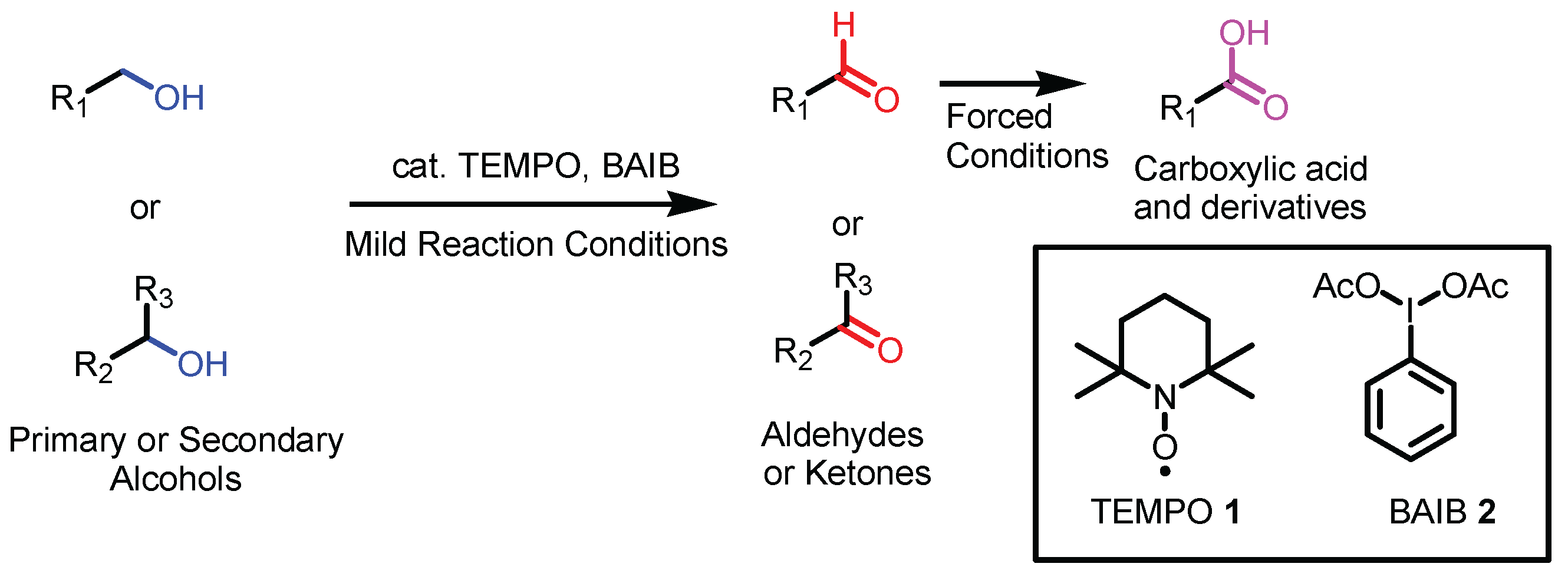

Back in 1997, funding and instrumentation were limited at the chemistry department at Roma Sapienza. No exact mass spectrometer was available; the NMR instrument was an old Gemini 200 MHz and there was limited access to a 300 MHz instrument. However, something was not limited: scientific creativity and most of all, scientific freedom. Professor Giovanni Piancatelli left his then-first-year PhD student Roberto Margarita free to test new ideas and reactions. While most of the ideas they attempted lead to non-useful reactions, one of them developed into an very interesting oxidation methodology: the combination of a catalytic amount of TEMPO

1, ((2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxyl) or (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxidanyl) and BAIB

2 (bis(acetoxy)iodobenzene, also known as PIDA, phenyliodine(III) diacetate, or phenyl-λ

3-iodanediyl diacetate) which acted as the stoichiometric oxidant. The combination of these two reagents leads to a unique methodology for the oxidation of primary and secondary alcohols to aldehydes and ketones (

Scheme 1), with the possibility of further in situ over-oxidation of the aldehyde to a carboxylic moiety if the reaction conditions are forced. Since the publication of the original paper in 1997 [

1], this methodology has been applied several times on various complex substrates, on small and large scale. This reaction should not be confused with the Piancatelli Rearrangement, a unique chemical transformation also developed by Prof Piancatelli in 1976, which was nearly forgotten for decades and recently surged to popularity [

2].

The initial J. Org. Chem. article on the oxidation of alcohols, co-authored by Prof- Piancatelli and Dr. Margarita, has been cited over 750 times to date. Sadly, Roberto Margarita, after a brilliant career in the industry with BMS and Corden Pharma, departed in his forties, and in June 2025 Prof. Piancatelli also passed away.

As said earlier, researchers have applied this transformation hundreds of times over the last decades. There appears to be no existing review specifically on this subject. Those who were the most entitled to write it, Piancatelli and Margarita, published just another paper on this subject, an invited contribution on Organic Synthesis [3, 4]. A measure of success for a new transformation in organic chemistry is how many times unrelated researchers cite this work, rather than relying on many self-citations, which is the case with the Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation.

The purpose of this Review is to describe a useful tool in organic synthesis and remember two brilliant scientists through the most well-known reaction they developed together. Additionally, the review will present some selected examples on complex molecules and in total synthesis, to illustrate its wide applicability. To keep the material to a manageable amount and give a timely report, I decided to select (with few exceptions) only papers published from the year 2020 and on. Special attention was dedicated to large-scale (tens of grams) reactions, because nowadays only transformations that use environmentally benign conditions are normally scaled up to these amounts. The fact that such large-scale reactions are reported is indirect evidence of the robustness of this reaction. I hope that this review can be of interest to academic and industrial scientists who need an easy, safe, and reliable protocol for the oxidation of alcohols.

3. Selected examples of Piancatelli-Margarita Oxidation applications in synthesis: large-scale reactions and small molecules.

In this section, it will be presented some examples published in the recent literature since 2020.

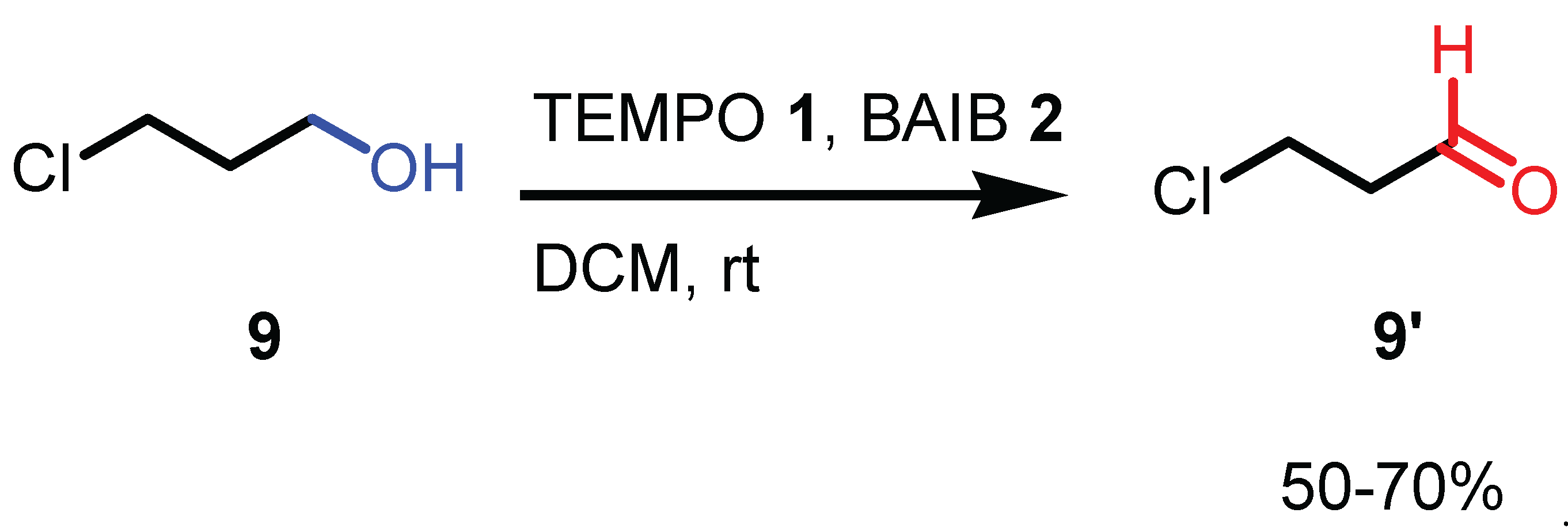

While reactions conducted on large molecules can be impressive, transformations of molecules with very few carbon atoms can also be difficult. Not always the synthesis of “small” molecules equals “easy”. First, a small molecule usually has a boiling point that is close to the solvent employed. Second, small molecules are often water-soluble, therefore their purification via phase extraction can be difficult. Third, small molecules, especially if bearing one or more reactive groups, can be quite unstable, making reactions difficult to reproduce if conditions are not exactly controlled.

Keeping these aspects in mind, O’Reilly and coworkers attempted the oxidation of 3-chloro propanol

9 to 3-chloro propanal

9’ with catalytic TEMPO

1 and BAIB

2 [

16]. The yields are given as a range (50-70%), since during purification and concentration

in vacuo some decomposition of the aldehyde

9’ to acrolein via HCl elimination occurred. This was not a major issue, since aldehyde

9’ can be telescoped in DCM solution to the next reaction. However, in their synthesis of azetidines, they ultimately chose a different procedure based on the hydrolysis of acrolein diacetal, because it was found to be more convenient. Nevertheless, TEMPO

1/BAIB

2 oxidation has been proved to be effective in preparing the elusive aldehyde

9’ (

Scheme 6).

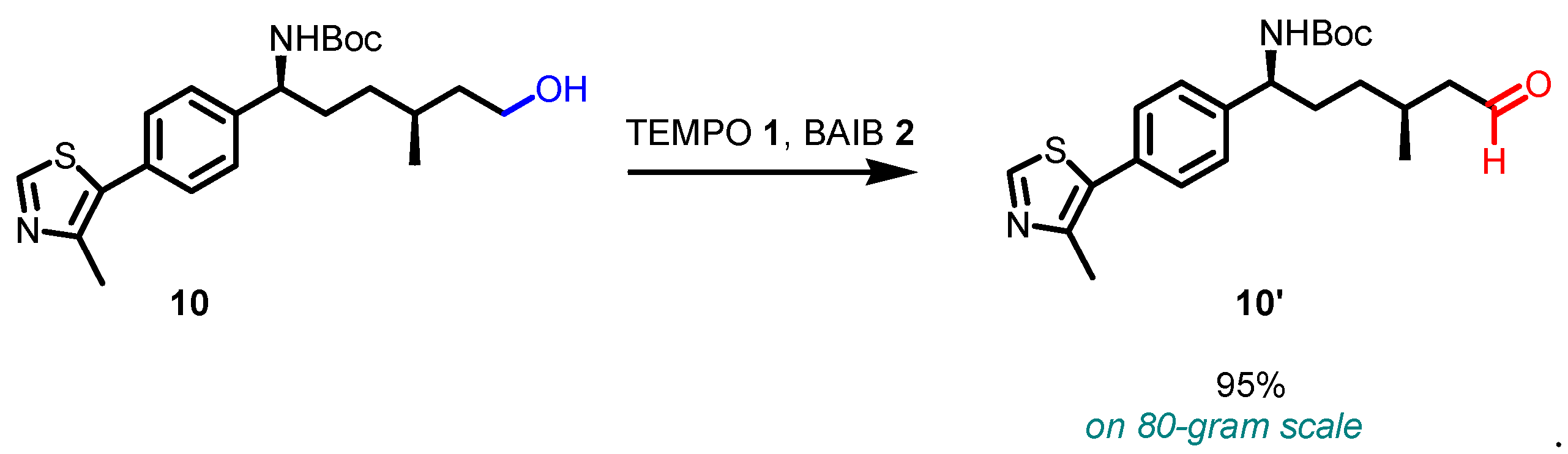

For their preparation of the anticancer agent BI 1810284, the industrial researchers of the group of Reevs reported an eighty-gram scale Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation of alcohol

10 to aldehyde

10’. In this reaction were employed 80 g of alcohol

10 (90% purity), 2.8 g of TEMPO

1, and 68 g of BAIB

2 and after a work-up and concentration were obtained 116 g of aldehyde

10’ (58% purity), most likely in a mixture with iodobenzene. An aliquot was purified, and the purity of the aldehyde was evaluated to be 95% [

17]. Since purifications are expensive on a large-scale, it is not unusual that products are directly telescoped to the following steps. The by-product of Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation is iodobenzene, a relatively inert compound. This renders the reaction attractive when purifications should be avoided, as in industrial large-scale reactions (

Scheme 7).

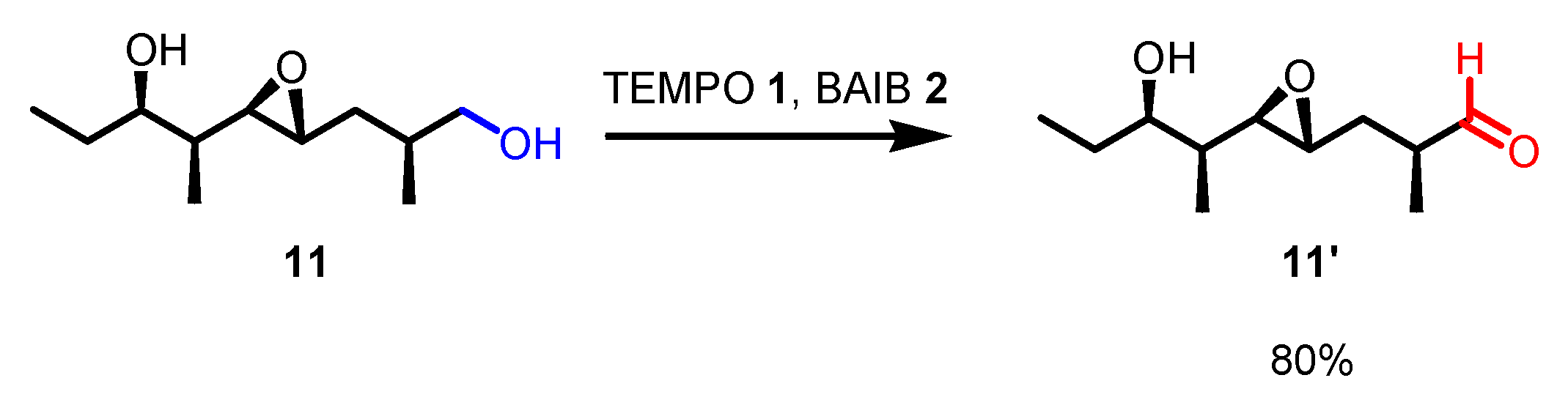

In their total synthesis of pladienolide A, Rhoades, Rheingold, O’Malley and Wang depicted a protective group-free sequence. One of the key steps was the oxidation of the primary alcohol functional group of intermediate

11 to aldehyde

11’, despite the presence of a secondary alcohol and of a reactive epoxide functionality. This task was successfully achieved by using the Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation, obtaining aldehyde

11’ in 80% yields [

18] (

Scheme 8).

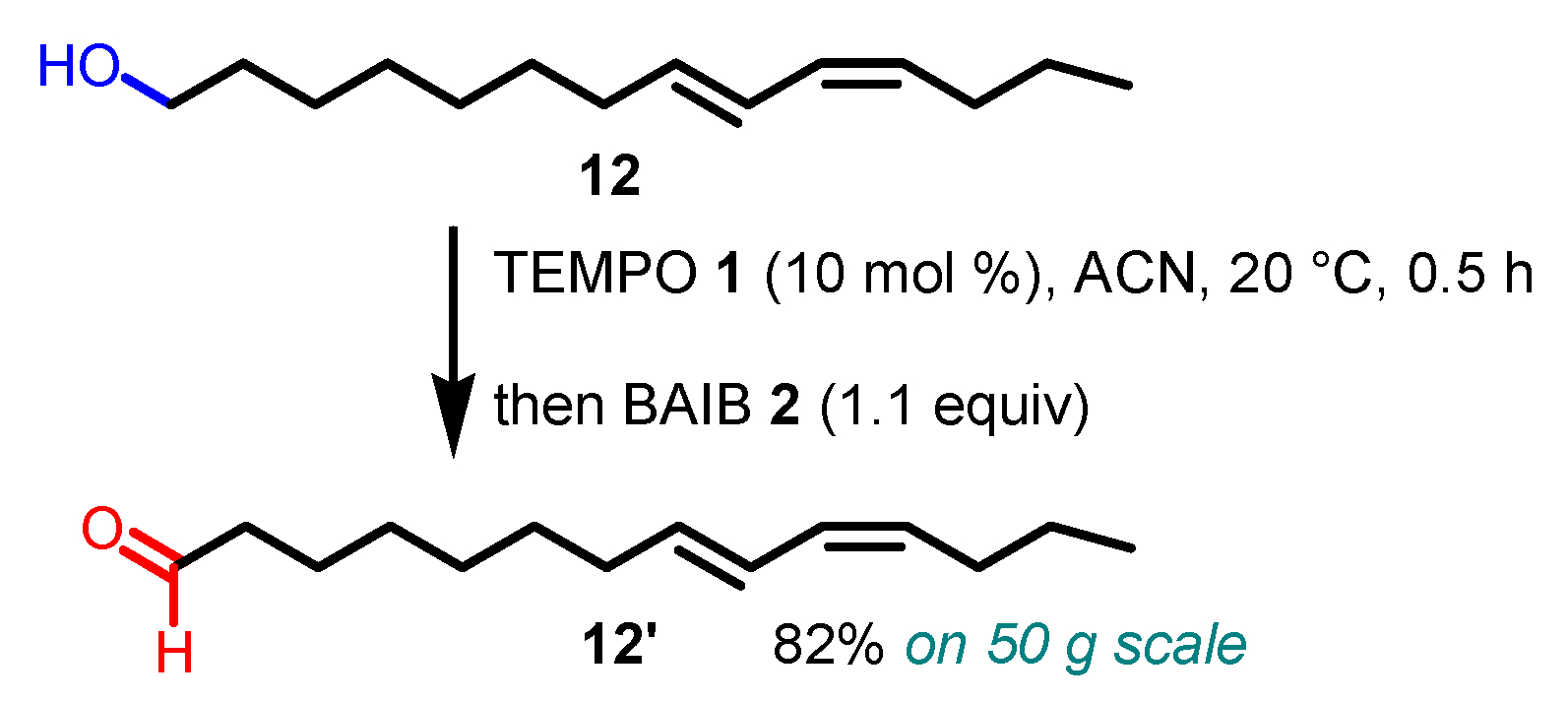

Gayon, Lefevre, and coworkers, in their large-scale synthesis of the sex pheromone of the horse-chestnut leaf miner, planned the oxidation of alcohol

12 to the desired target molecule

12’ [

19]. The final reaction was run on a fifty-gram scale, using 51 grams of alcohol

12, 3.8 grams of TEMPO

1, and 85 grams of BAIB

2 (

Scheme 9). According to the authors, this synthesis is easily scalable. Biodegradable pheromones can be a valuable alternative method in insect control if compared to other synthetic insecticides. Nevertheless, the preparation of pheromones must employ eco-friendly conditions, and to develop a synthesis with these characteristics was the goal of the industrial researchers.

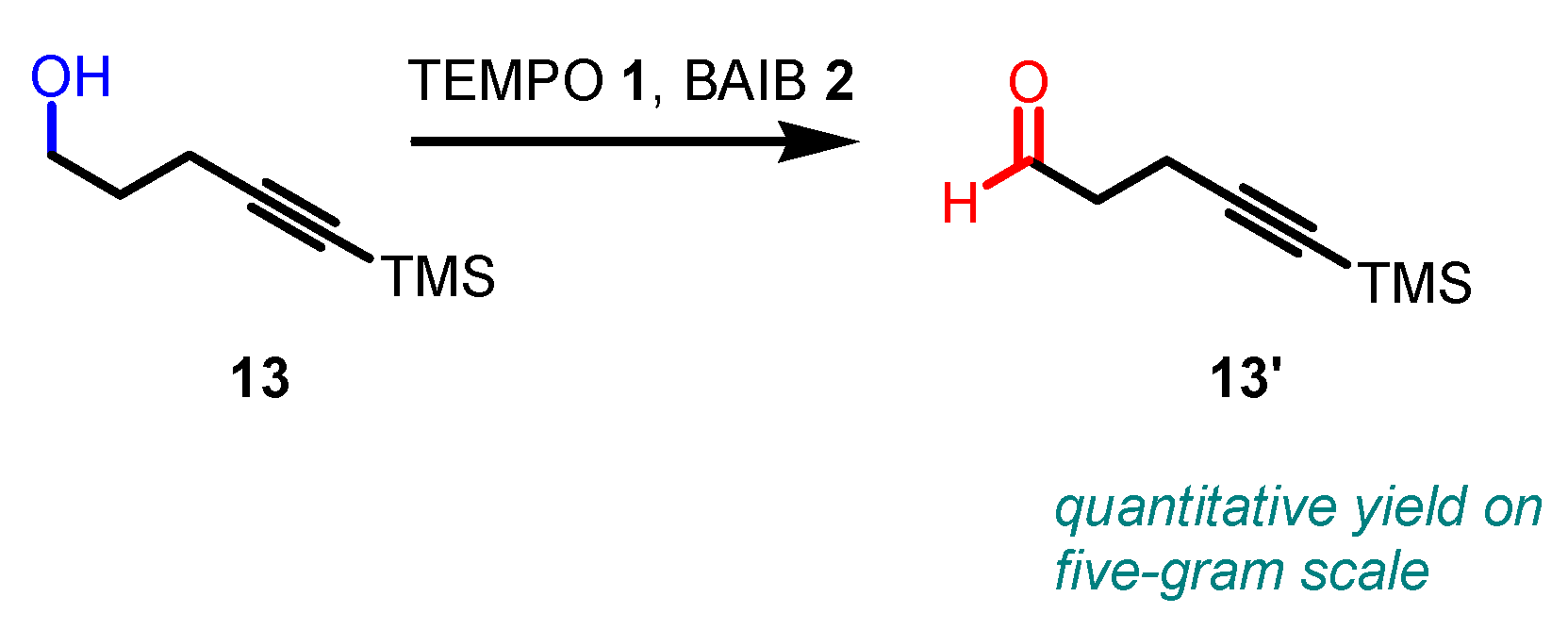

During their asymmetric synthesis of (-)-dehydrocostus lactone, [

20] Metz and co-workers employed oxidation reactions in several steps. In some instances, these authors exploited Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation. They commenced their synthesis with the preparation of aldehyde

13’ from alcohol

13, on a five-gram scale. Aldehyde

13’ was obtained in quantitative yields either with Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation or Swern oxidation (

Scheme 10).

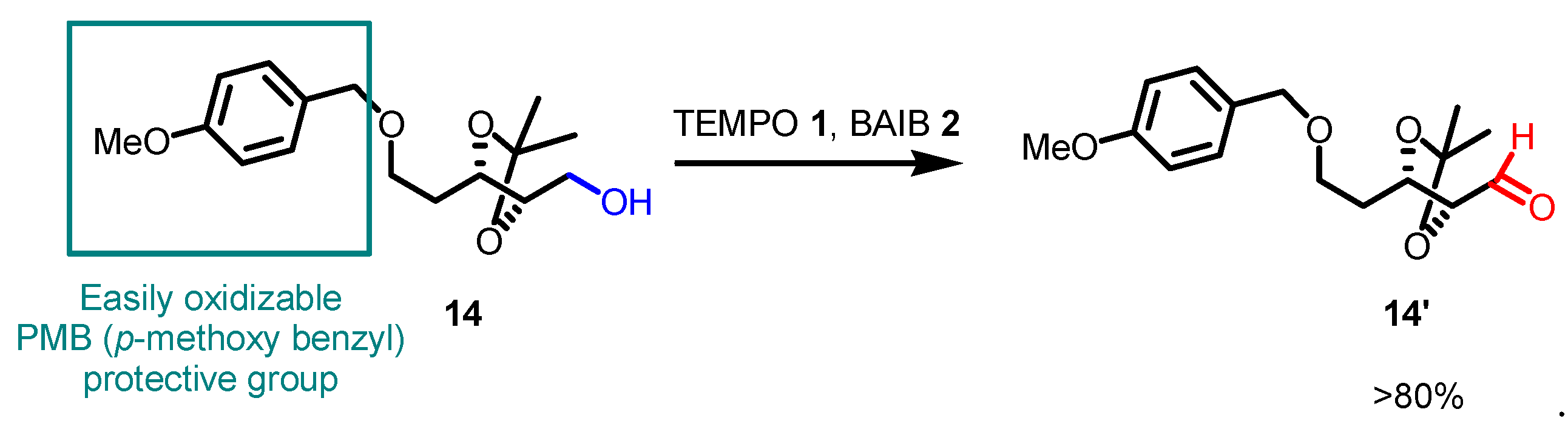

A useful protective group for the alcoholic moiety is the PMB or

p-methoxybenzyl group. This protective group can be removed either with catalytic hydrogenation or using a mild oxidant, giving back the free alcohol functionality. Gosh and Hsu, in their total synthesis of (+)-EBC-23, an anticancer agent from the Australian Rainforest, showed that the PMB protective group of intermediate

14 is not affected by the Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation protocol, giving aldehyde

14’ in good yields [

21]. This transformation is part of a four-step sequence in which the intermediate alcohol

14 is telescoped from the previous reaction in DCM solution. 80% yields are reported for the entire sequence (

Scheme 11).

In their total synthesis of the pseudopterosin A-F agylcone, Schmalz and co-workers employed the Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation on primary alcohol

15 to give aldehyde

15’ [

22]. The reaction proceeded in good yields despite the presence of an electron-rich aromatic ring which can, in principle, be easily oxidized and instead is not affected. The yield of this reaction (including the previous double bond hydrogenation) is 75% (

Scheme 12).

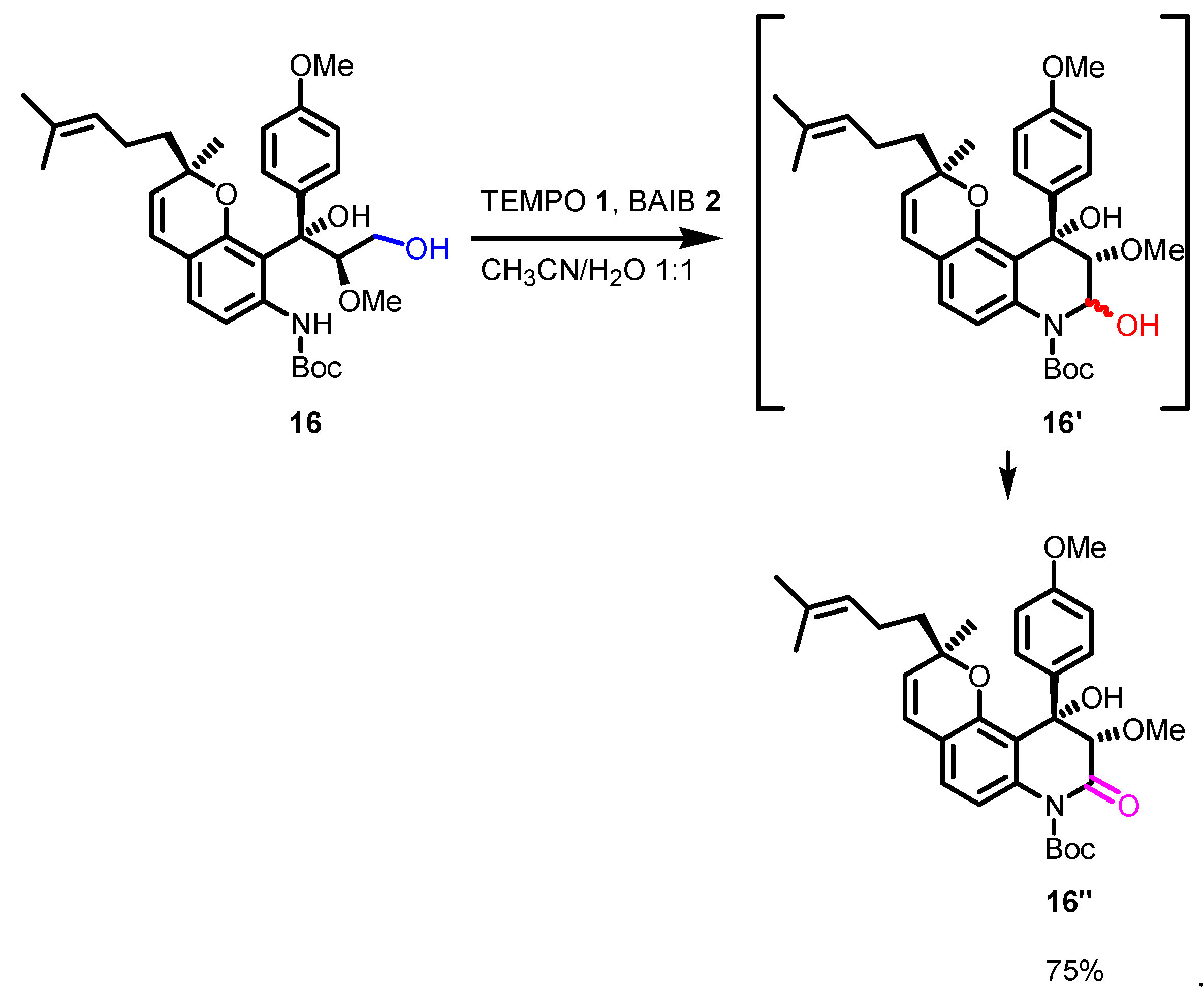

An example of the chemoselectivity of Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation was reported by Hanessian and co-workers in their synthesis of insecticide metabolite yaequinolones J1 and J2. These authors needed an oxidation method for primary alcohol

16 that would afford an intermediate, the N-protected hemiaminal

16’ which can undergo further oxidation to a lactam, specifically N-Boc dihydroquinolin-2-one

16’. They tested several oxidants (PDC, Corey−Schmidt, PCC), but none of them was as effective and selective as the TEMPO

1/BAIB

2 combination. The hemiaminal intermediate

16 c be detected by NMR analysis after 3 h before further oxidation to the lactam took place. The authors state that, to the best of their knowledge, the TEMPO/BAIB reagent combination was used here for the first time for the direct synthesis of an N-Boc lactam from a primary alcohol [

23]. It is worth noticing that neither the enol ether functionality, the aryl methoxy group nor the labile acid-sensitive benzylic tertiary alcohol were affected (

Scheme 13).

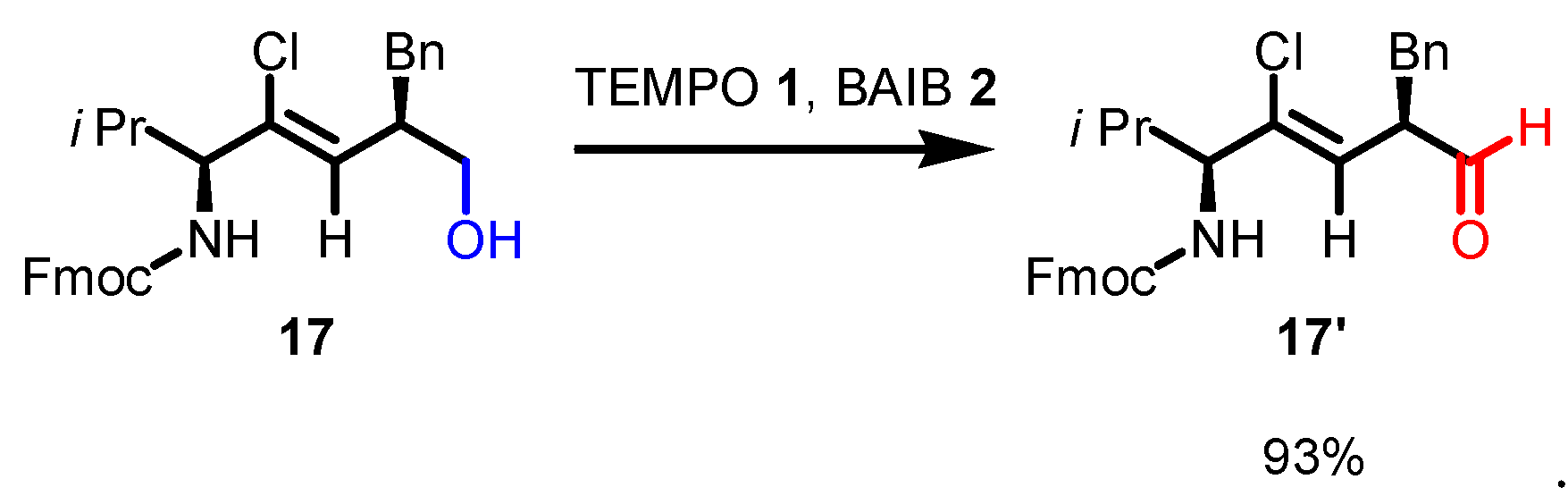

To develop a synthesis of chloroalkene dipeptide isosteres, Tamamura

et al. resorted to Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation for omoallylic alcohol

17 to aldehyde

17’ in 93% yield [

24] (

Scheme 14). The following step of their synthesis is the oxidation of the aldehyde functionality to a carboxylate, which was achieved by means of Pinnick oxidation. It is surprising that the authors used a two-step oxidation protocol, since forcing the reaction conditions would presumably lead to the same carboxylate. However, no explanation is given in the original paper.

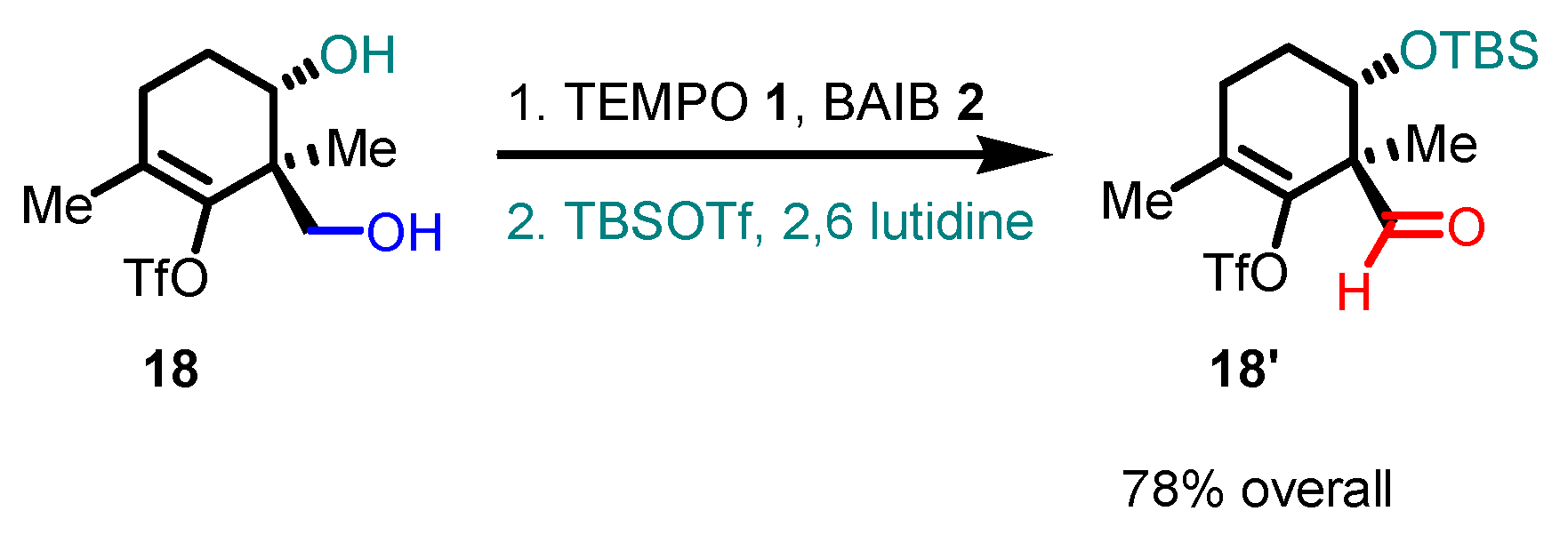

Another example of oxidation of the primary alcohol in the presence of a double bond and a secondary alcohol was reported by Sarpong and co-workers in their studies towards the synthesis of diverse taxane cores, specifically in the oxidation of alcohol

18 to aldehyde

18’, to give, after TBS protection of the secondary alcohol functional group, the taxane C-ring fragment [

25]. This two-step sequence has 78% yields (

Scheme 15).

In the original paper by Piancatelli and Margarita [

1], it was reported that phenylthiol and phenylselenium functional groups are not affected by their oxidation methodology. This is noteworthy, since the phenylthiol and phenylselenium groups are usually introduced into molecules to generate a double bond upon oxidation, for example with NaIO

4. Their findings on the selective alcohol group oxidation are confirmed by the work of Gardiner

et al., in their efforts towards the synthesis of heparan sulfate- and dermatan sulfate-related oligosaccharides. The Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation of alcohol

19 afforded [2.2.2] bicyclic lactone

19’ in 73% yields using the “forced” conditions (acetonitrile and water) [

26] (

Scheme 16).

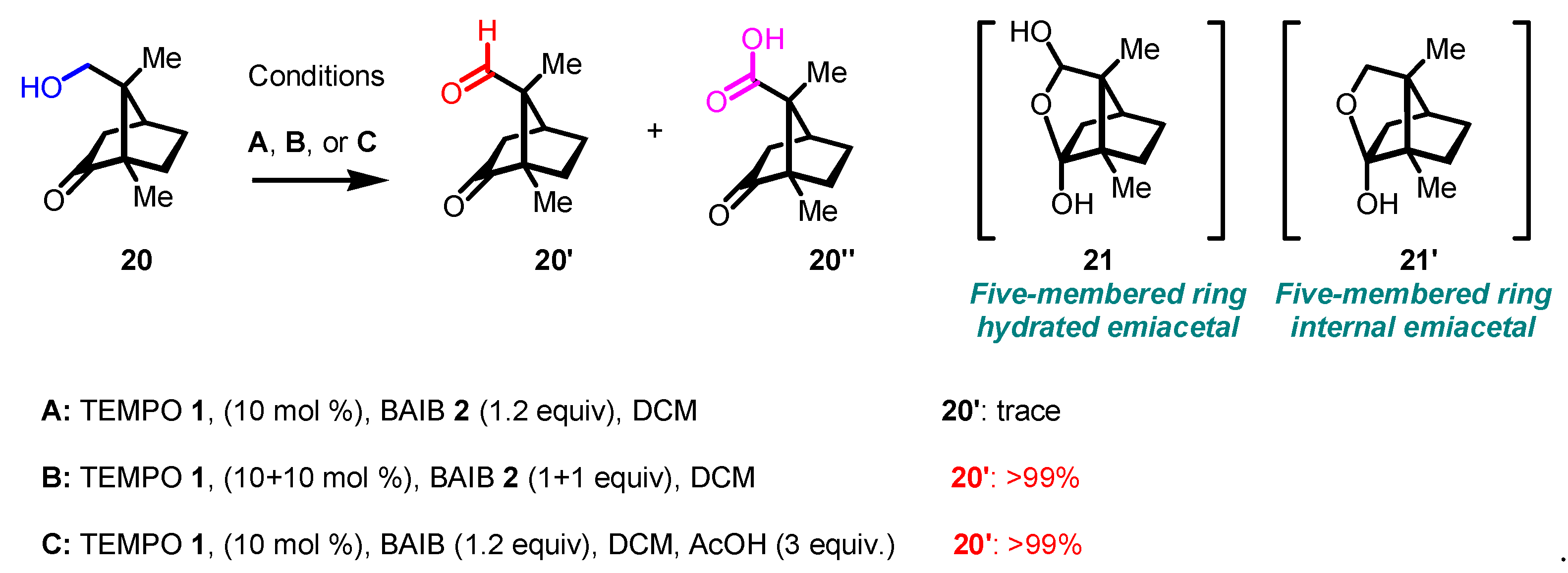

Sarpong and coworkers solved an intriguing problem in their studies towards the synthesis of the longiborneol sesquiterpenoids. [

27] Their goal was to oxidize the alcohol functionality of intermediate

20 to the corresponding aldehyde in compound

20’.

However, when they used Dess-Martin periodinane

7 or other oxidation methods (Ley−Griffith oxidation) their product was instead carboxylic acid

20’’. They hypothesized that the over-oxidized compound

20’’ can be derived from the fast oxidation of internal hydrate acetal

21. Then testing the standard conditions of Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation (

Scheme 17, conditions

A) none of the desired aldehyde

20’ was isolated. They also hypothesized that an analogue internal acetal of

21, specifically compound

21’¸can prevent the oxidation. They then tested two new approaches: the addition of a second equivalent of BAIB

2 (conditions

B) or the addition of 3 equivalents of acetic acid (conditions

C) in order to break the internal acetal. Both these modifications were successful, delivering the desired aldehyde

20’ in 99% yield (

Scheme 17).

The formation of internal emiketal was also an issue faced during the synthesis of the ABC ring system of kadlongilactones reported by Wang and Chen [

28]. The ketone

22a existed as a mixture with emiketal

22b which was detected by NMR. Also, in this case, the oxidation to the corresponding lactone

22’ required more equivalents of BAIB

2 (2.5 equiv. according to the supporting information of the article, see

Scheme 18).

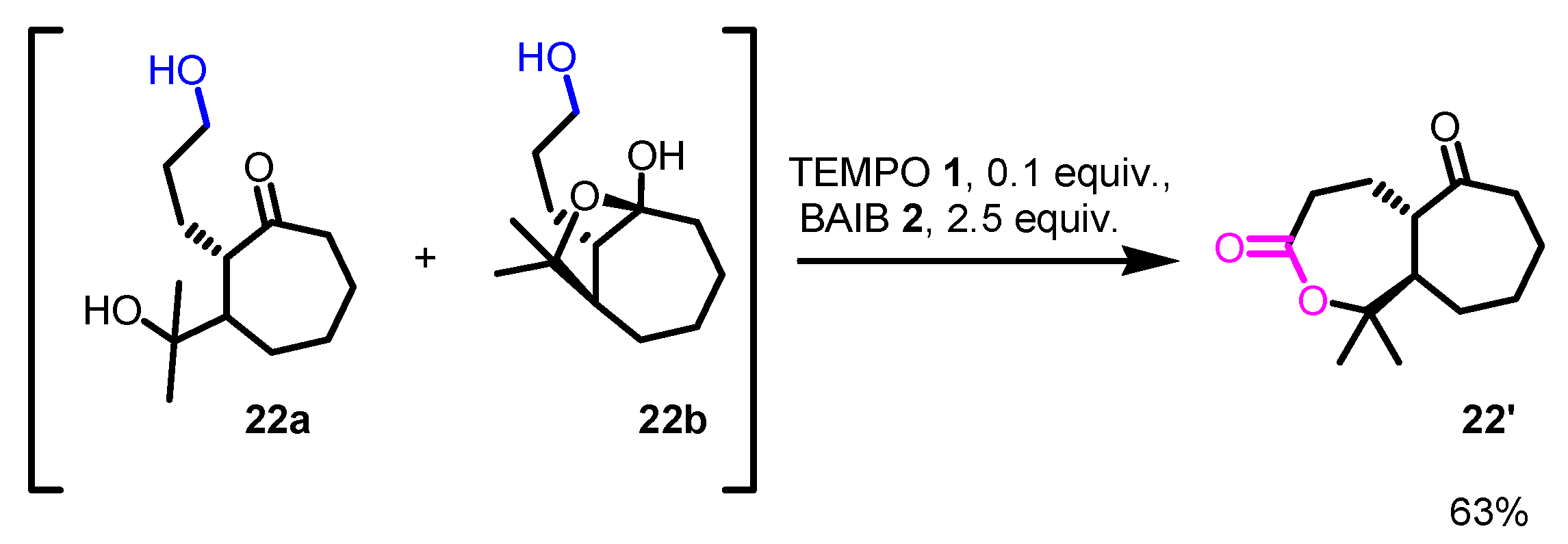

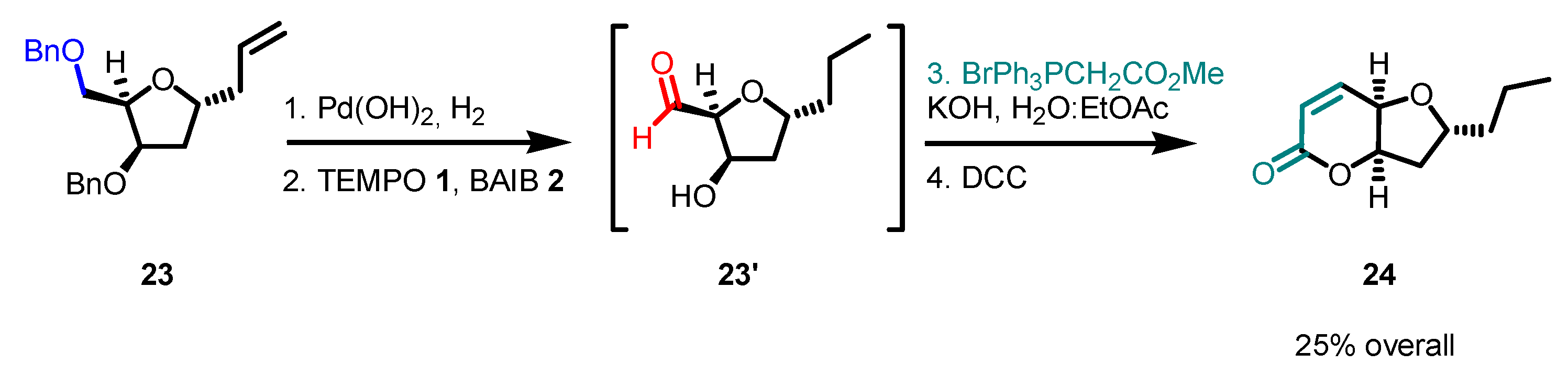

Being a versatile and robust reaction, the Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation can be incorporated in some standard synthetic sequences. One of these is the primary-alcohol oxidation-Wittig reaction. An interesting example is reported by Cordero-Vargas, Sartillo-Piscil, and co-workers in their synthesis of (+)-lasionectrin [

29]. Tetrahydrofuran intermediate

23 was first subject to simultaneous double bond reduction and primary alcohol deprotection, and then to the oxidation of the alcoholic function to give intermediate

23’. This compound was then subject to the Wittig-Horner reaction with the resulting methyl (triphenylphosphanylidene)acetate and hydrolysis of the methyl ester, to give, after DCC-mediated intramolecular lactonization, the desired compound

24 in 25% overall yields (

Scheme 19).

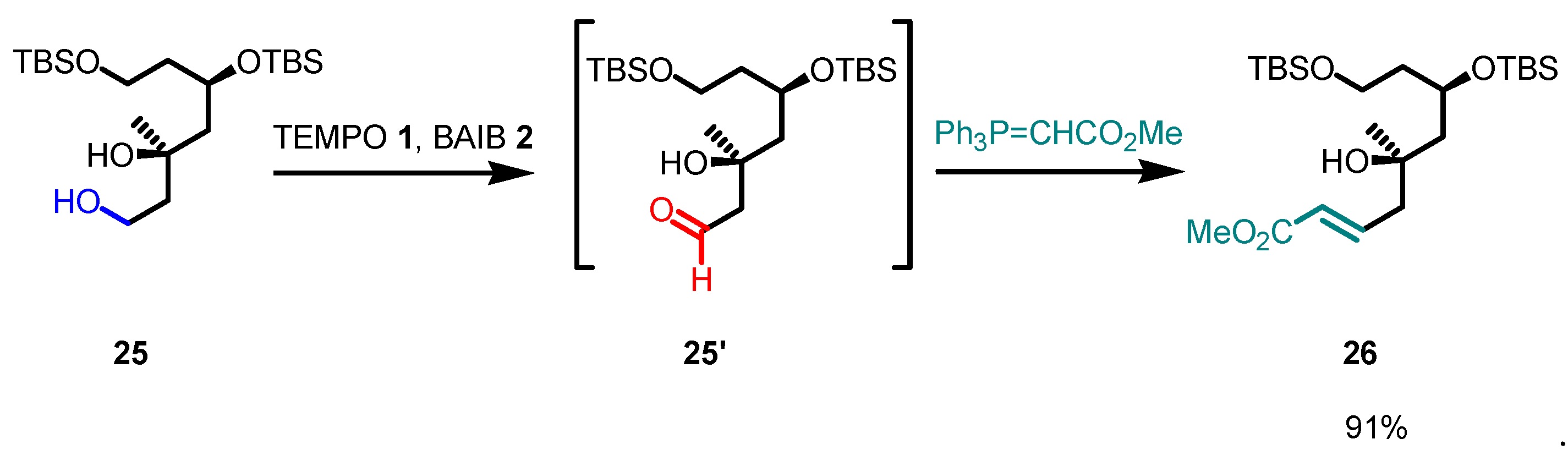

A similar example was reported by Takamura and co-workers during their synthetic approach towards the preparation of scabrolide F [

30]. Thus, double-protected intermediate

25 was first oxidized with the standard Piancatelli-Margarita protocol to give aldehyde

25’, and then subjected to Wittig-Horner reaction to give alkene

26 in 91% overall yield (

Scheme 20).

It is well-known that esters can be reduced to the corresponding aldehydes using DIBAL-H reduction. However, it can be difficult to dose the exact amount equivalent of the reducing reagent and, since aldehydes are easily reduced with respect to esters, often the result is the formation of a primary alcohol, incomplete reduction of a mixture of compounds. From a practical point of view, it can be more convenient to use a two-step sequence: first total reduction of the ester to primary alcohol and then partial re-oxidation to the aldehyde. Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation can be conveniently and successfully employed in the second step. A recent example can be found in the work of Saito, Shimokawa, and Yorimitsu in their studies of the dioxasilepanyl groups [

31]. These authors first reduced ester

27 to the primary alcohol

28¸ and then re-oxidized it to the desired compound

28’ in 85% and 91% yields respectively (77% overall,

Scheme 21).

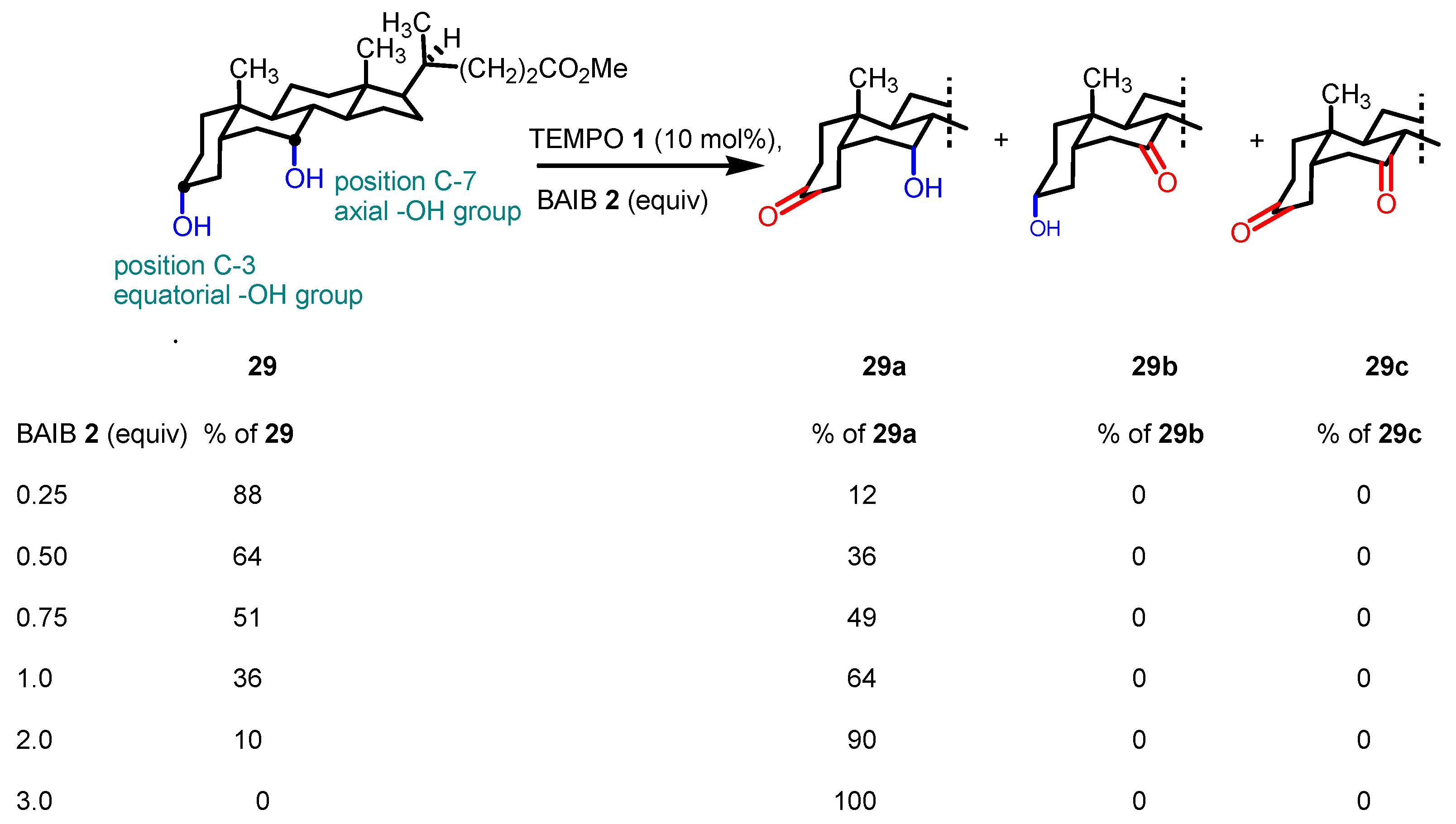

Kaspar and Kudova investigated the selectivity of oxidizing agents towards axial and equatorial hydroxyl groups. Among the several oxidants tested, there was the combination TEMPO

1/BAIB

2. Methyl chenodeoxycholate

29 bears both an axial and an equatorial group in blocked positions. When this compound was reacted with catalytic TEMPO

1 and an increasing amount of BAIB only the formation of axial-oxidized compound

29a was observed; no amount of equatorial-oxidized compound

29b or diketone

29c could be detected [

32], see

Scheme 22.

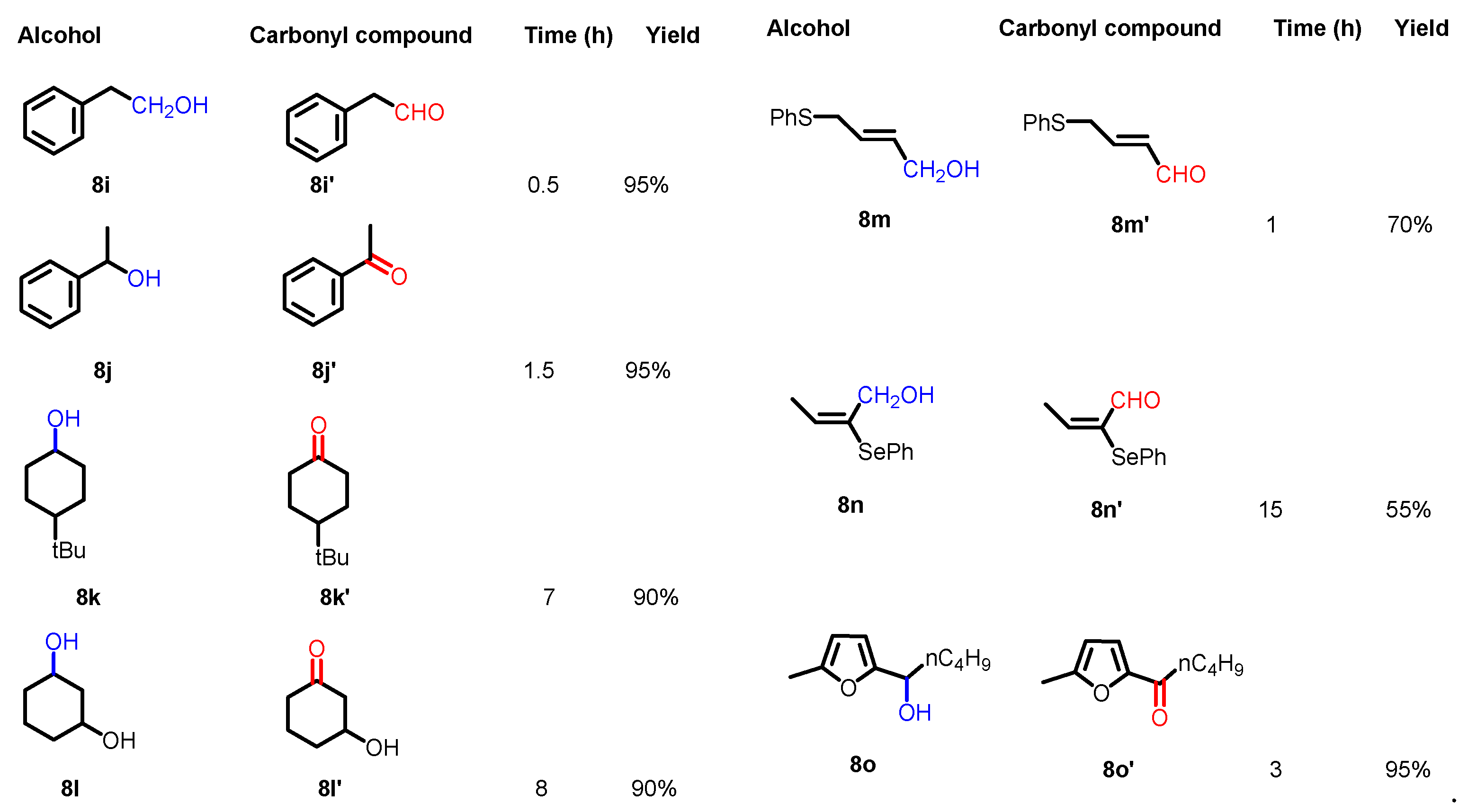

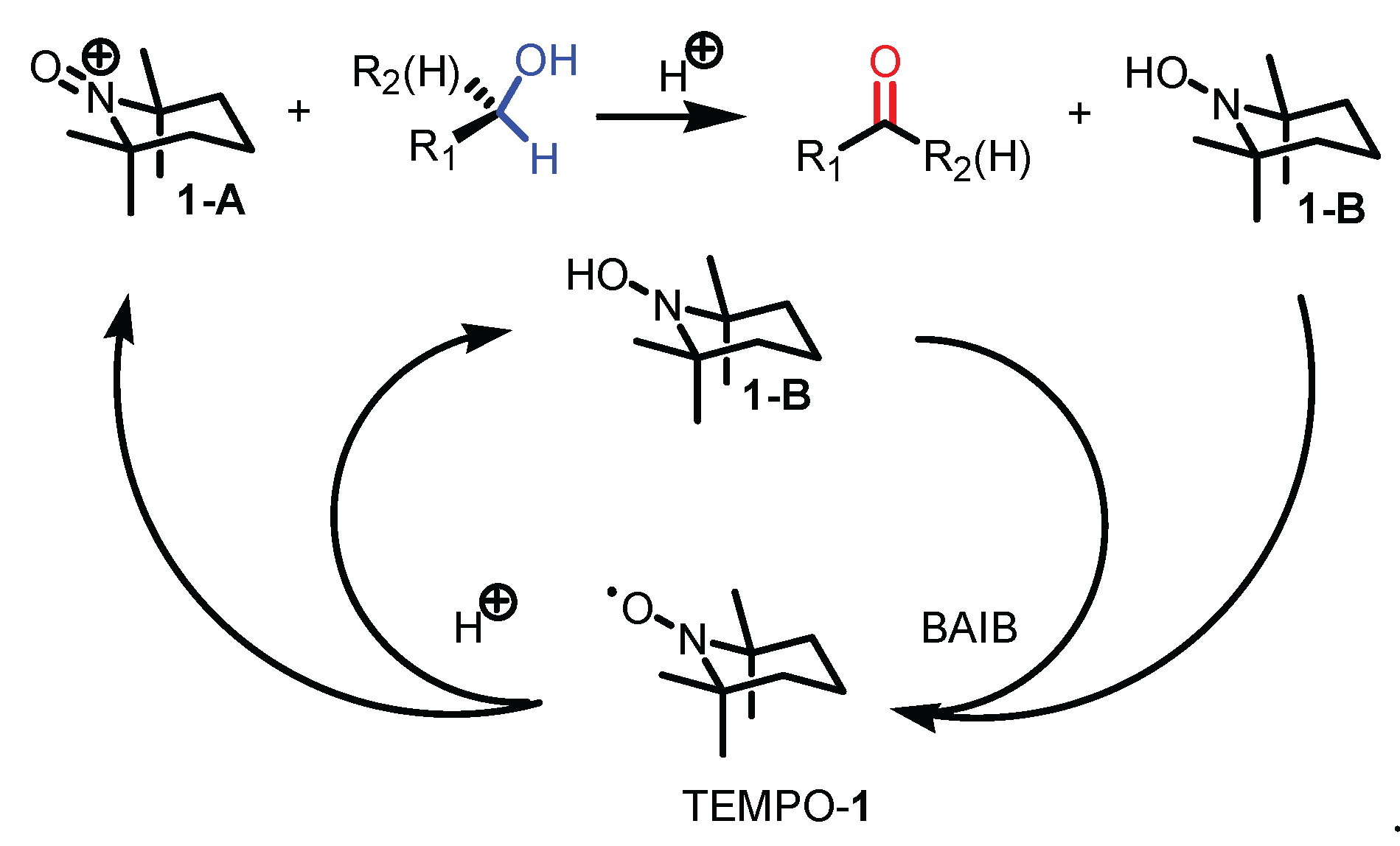

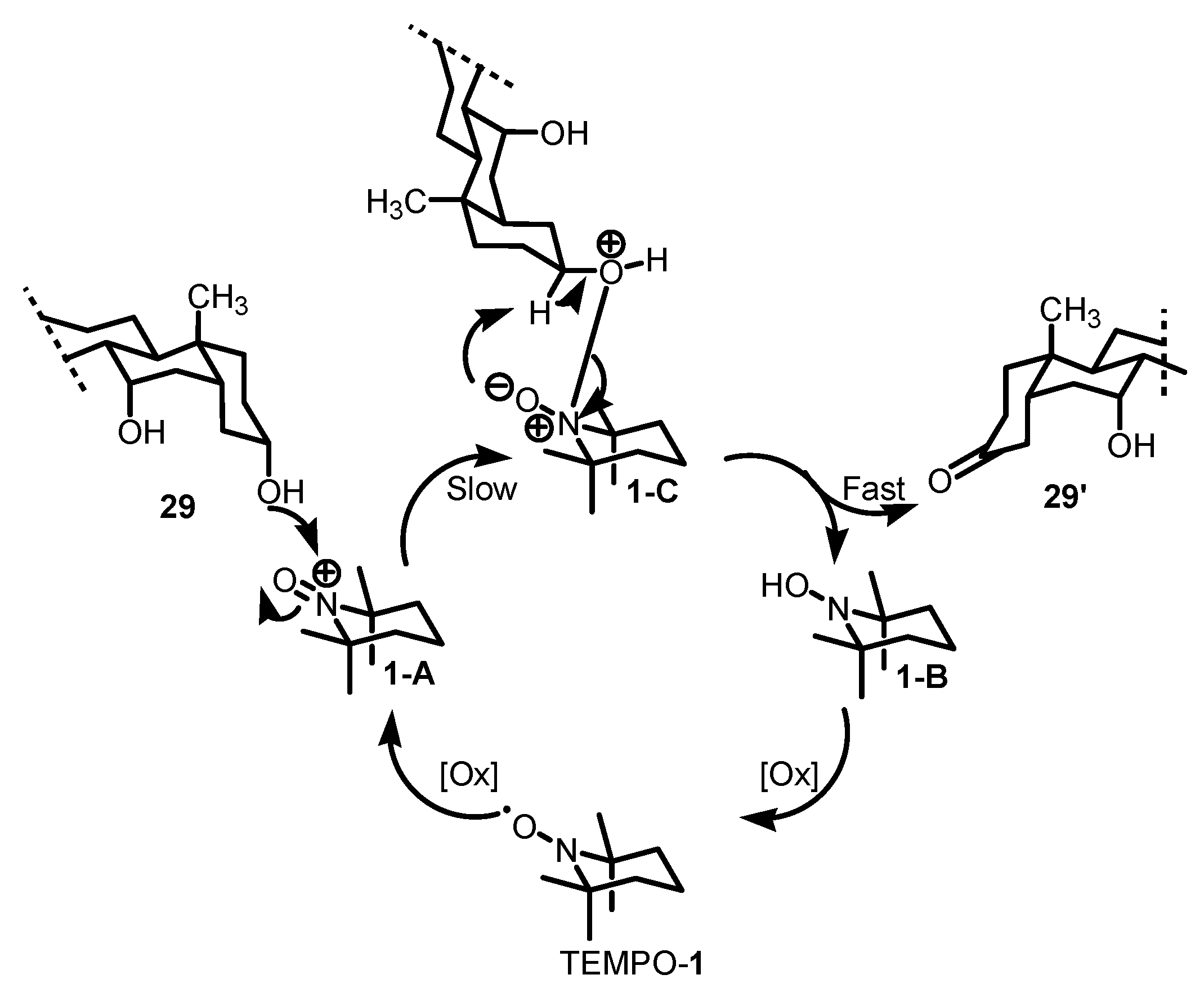

This selectivity was reversed with other hypervalent iodine (III) oxidants such as Dess-Martin periodinane

7, confirming that in Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation the oxidizing molecule is the organic aminoxy radical TEMPO

1. The authors hypothesized that this selectivity can arise from the steric hindrance around the C7 hydroxy group, leaving only the C3 hydroxy group accessible (see mechanism in

Scheme 23).

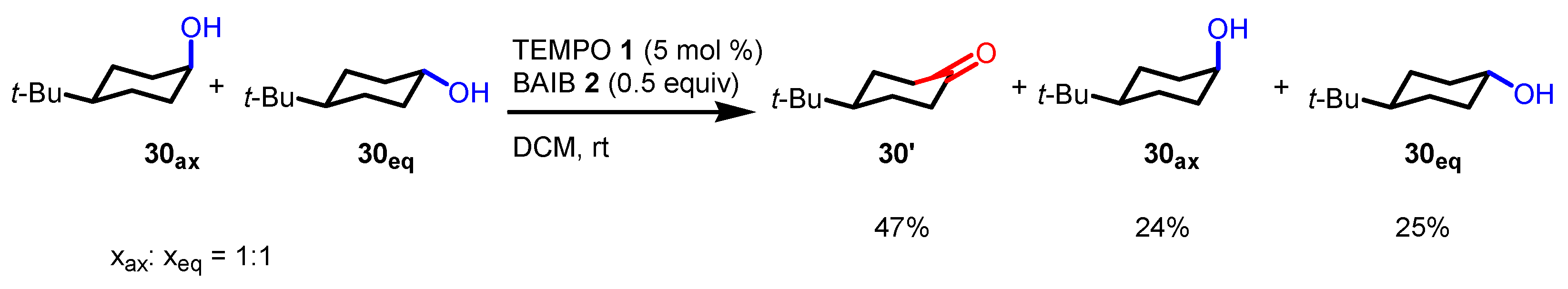

The authors also studied the oxidation of

cis 4-

t-butyl cyclohexanol

30ax, in which, due to the bulky

t-butyl group, the hydroxy moiety is conformationally blocked in the axial position and of

trans 4-

t-butyl cyclohexanol

30eq, where the hydroxy group is instead fixed in the equatorial position, but in this case they found that ketone

30’ was formed consuming in equal amounts

cis 4-

t-butyl cyclohexanol

30ax and of

trans 4-

t-butyl cyclohexanol

30eq. They hypothesize that the reason why this reaction is non-selective now is that no significant steric hindrance is present around the axial or equatorial hydroxy group (

Scheme 24). Their results are relevant, because they suggest that TEMPO

1 /BAIB

2 combination can be quite sensitive to steric factors.

4. Noteworthy applications of Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation in carbohydrate chemistry: examples from the recent literature.

Oxidation in carbohydrate chemistry is an especially challenging transformation since it operates on polyoxygenated structures which, in the case of polysaccharides, are also acid-sensitive moieties. A first example of the oxidation of a protected sugar moiety was reported in the original paper by Piancatelli and Margarita [

1], specifically the oxidation of five-membered sugar

8d to aldehyde

8d’. As seen before, forcing the reaction condition also carboxylic acid moiety can be obtained.

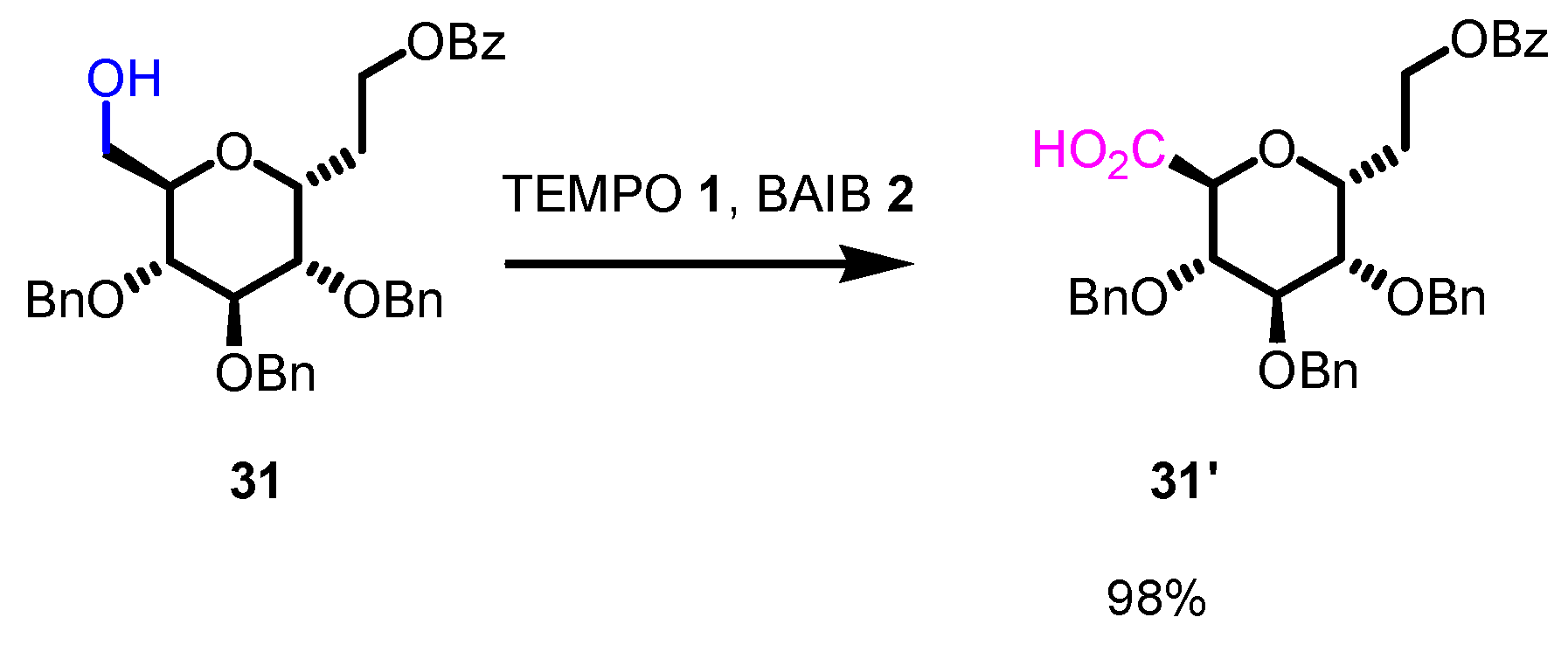

In a recent

J. Am. Chem. Soc. paper by Li

et al, the authors needed an efficient oxidation protocol for the transformation of the primary alcohol function of protected sugar

31 into carboxylate

31’ [

33]. This one of the first reactions towards the synthesis of 6-deoxy-D-/L-heptopyranosyl fluorides and was conducted on 1 g scale (see supporting information of this article) with catalytic TEMPO

1 (0.3 equiv.) and excess BAIB

2(2.5 equiv.) to afford compound

31’ in excellent yields (98%, see

Scheme 25).

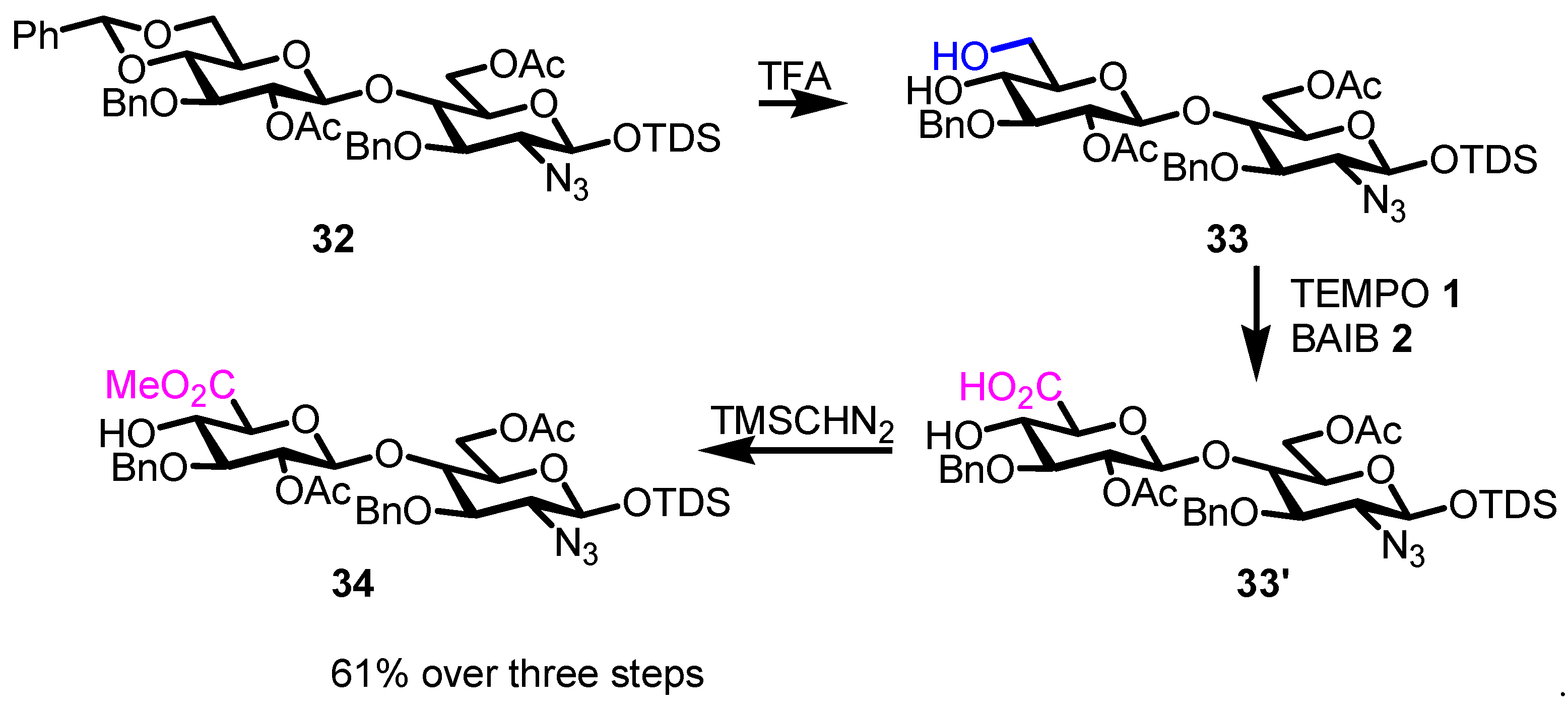

A similar oxidation procedure was incorporated in a three-step sequence, as reported by Boons in 2020, for the preparation of a disaccharide unit for the synthesis of heparan sulfate oligosaccharides [

34]. These consecutive reactions were run on 1 g scale and involved first the TFA-mediated selective cleavage of the acetal on disaccharide

32; then, the TEMPO

1-catalyzed/BAIB oxidation of the primary alcohol of intermediate

33 to give carboxylate

33’ in a mixture of DCM, and finally the formation of the methyl ester

34 using trimethyl silyl diazomethane (TMSCHN

2). The entire sequence has a satisfying yield of 61%, despite the presence of several functional and protective groups (see

Scheme 26).

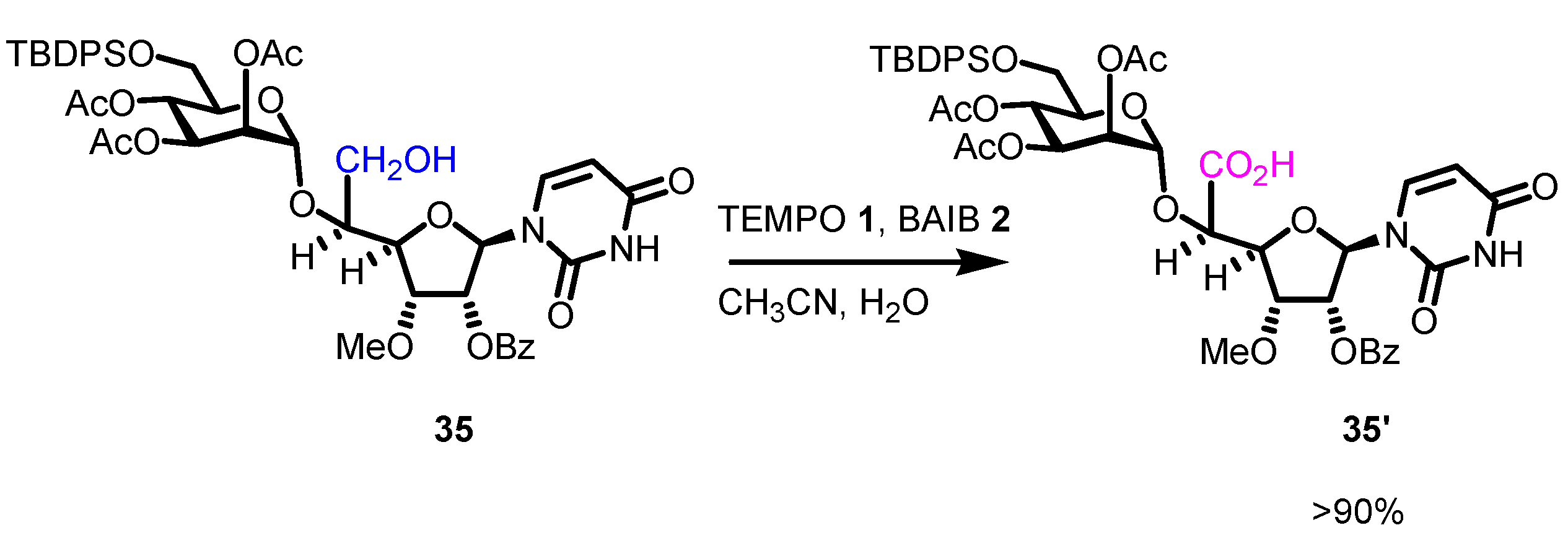

While working towards the total synthesis of the natural substance capuramycin, Xiao and co-workers needed to oxidize the primary alcohol function on compound

35 to a carboxylate moiety [

35]. The usual combination of catalytic TEMPO and BAIB in acetonitrile and water proved effective, accessing intermediate

35’ in a gratifying over 90% yield (

Scheme 27).

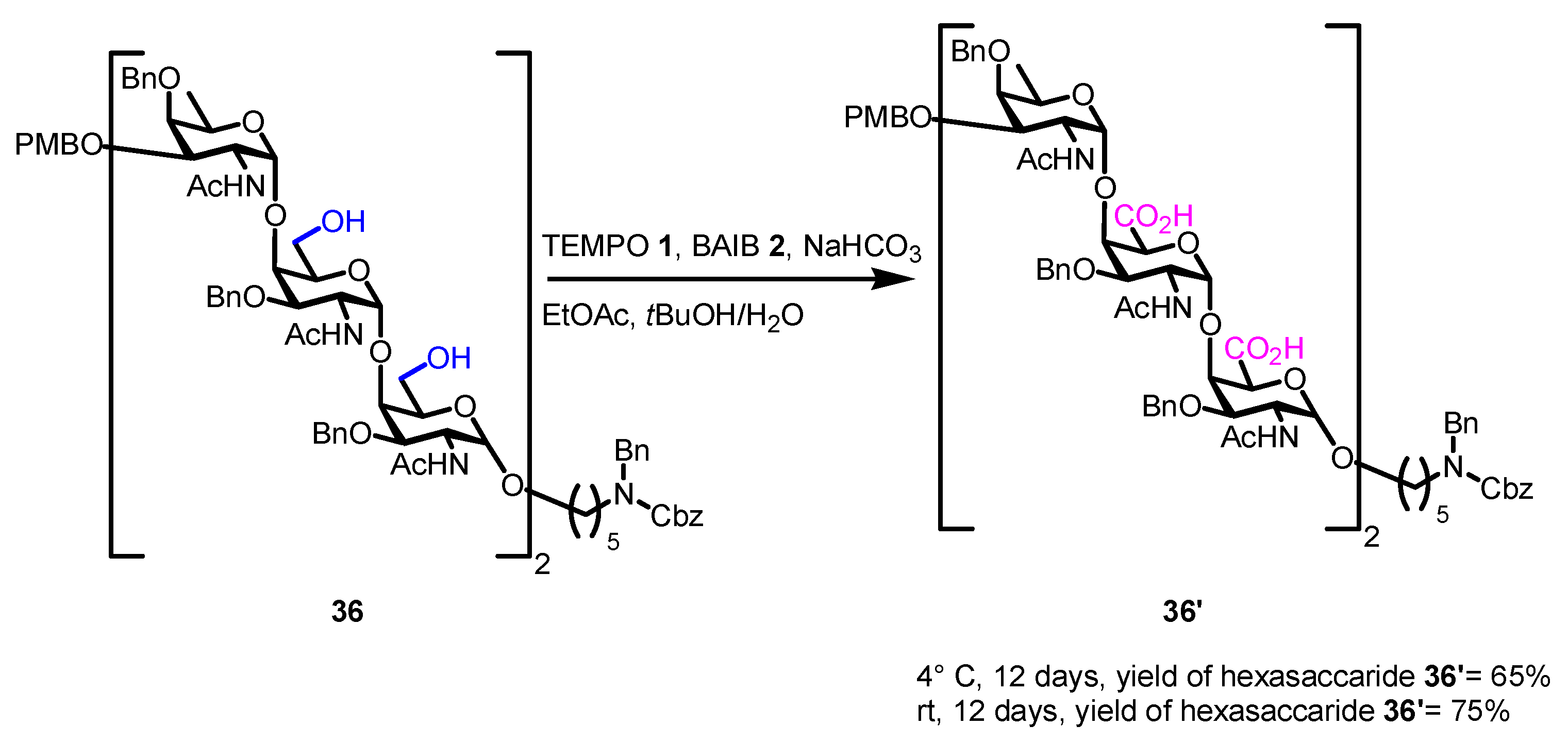

An impressive example of TEMPO

1/BAIB

2 multiple oxidations on complex molecules was reported by the group of Codée while synthesizing a set of

Staphylococcus Aureus capsular polysaccharides [

36]. These authors needed to oxidize a primary alcohol functional group to a carboxylic moiety. They modified the original protocol, using instead a mixture of ethyl acetate and

t-butanol/water with the addition of sodium bicarbonate. They tested their improved condition reaction on some substrates and even on the complex molecule hexasaccharide

36, which also contains an easily oxidizable protective group (PMB=

p-methoxybenzyl). As mentioned before, this moiety can normally be cleaved by mild oxidation with DDQ (2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1.4-benzoquinone). Despite this, hexasaccharide

36’ was obtained in 65% yield after 12 days, and, if the reaction time is shortened to 6 days and the reaction temperature is increased to room temperature, the yield rose to 75% (

Scheme 28).

5. Selected examples of Piancatelli-Margarita Oxidation applications in total synthesis: late-stage intermediates and endgame.

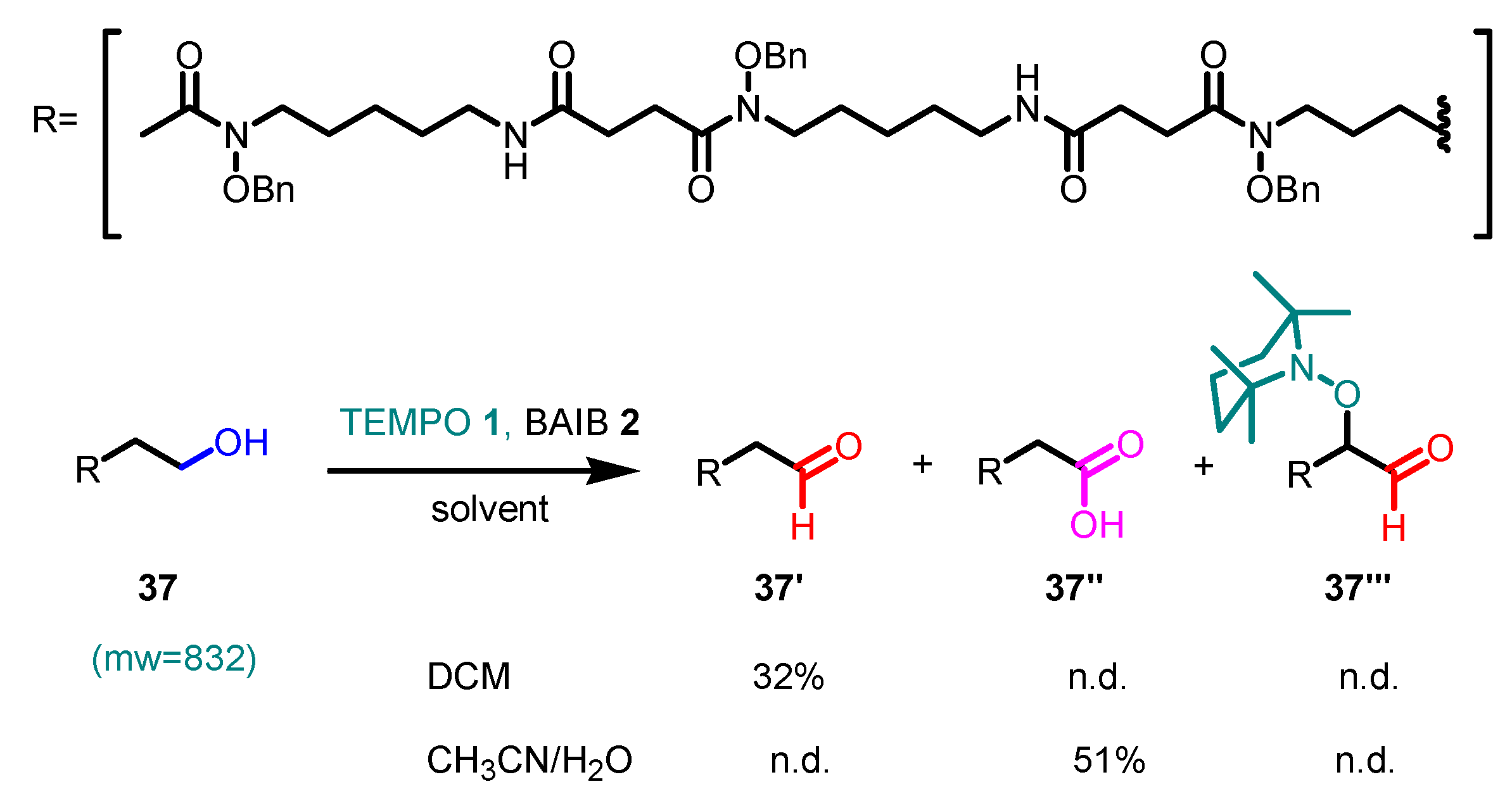

The strength, effectiveness, and usefulness of a methodology are ultimately proven by its application in total synthesis. Only a robust methodology can pass this crucial test which involves selectivity (are other functional groups affected?), large- and small-scale tests, and efficacy on a complex molecule. While the reaction on a simple substrate can be incorrectly reported, a low-yielding transformation in a multistep sequence can dramatically drop the global yield, to a level at which no significant amount of the final product can be detected. Therefore, when a reaction is incorporated in one or more complex successful total syntheses, this is the best possible guarantee that it works, at least to some extent.

Reactions on molecules with high molecular weight represent a unique challenge. Reactions on similar small molecules can give a similar outcome. As an example, it is expected that an oxidation on a five-carbon primary alcohol would a similar reaction on a six-carbon primary alcohol, but the outcome might change dramatically if the same reaction is then run on a primary alcohol which has twenty carbon atoms or more. Organic molecules with few atoms can have a limited number of possible conformations. The number of conformations increases exponentially with the number of atoms, and therefore the functional group can be “hidden” in a specific conformation. This is especially true with molecules with long chains. Therefore, finding a successful reaction on long-chain molecules is not straightforward. Chambron and co-workers were studying an enantiopure bifunctional chelator for

89Zr-immuno PET. Specifically, they were looking for a tetradentate ligand or zirconium [

37]. One of the reactions they needed was the oxidation of primary alcohol

37 whose molecular weight is more than 800 Dalton. Even on this complex molecule, the Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation works well, affording aldehyde

37’ in 32% yields if the usual reaction conditions are used (DCM as the solvent) and carboxylic acid

37’’ in 51% yields if the solvent is changed to an acetonitrile/water mixture. These authors did not detect any of the TEMPO

1-substrate adducts (

Scheme 29).

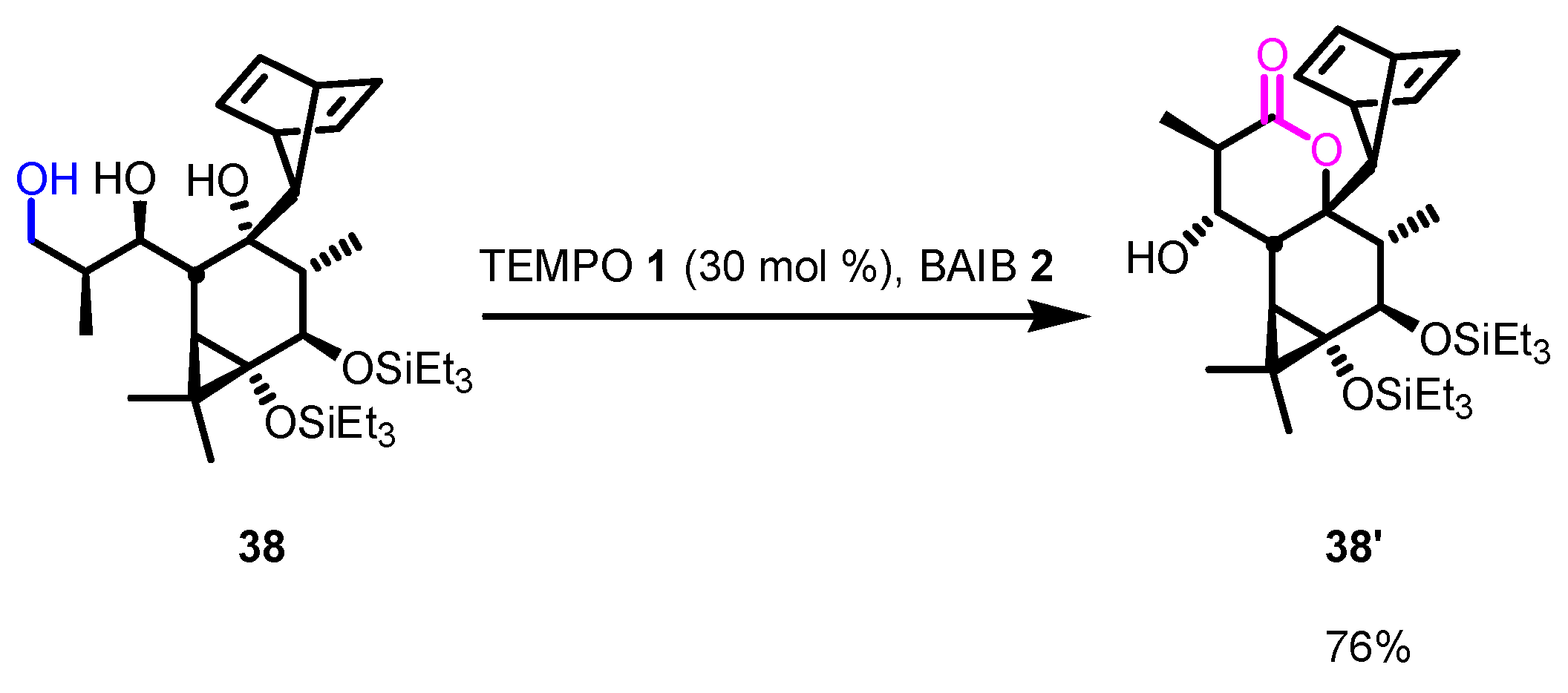

Carreira and Fadel reported in 2023 the first enantioselective total synthesis of (+)-pedrolide, a tigliane-derived diterpenoid, showing an unprecedently reported skeleton. One of their late-stage key transformations was the selective oxidation of the primary alcohol of intermediate

38 to give lactone

38’ in 76% yield using of what they called “Piancatelli’s and Margarita’s TEMPO oxidation protocol [

38], see

Scheme 30.

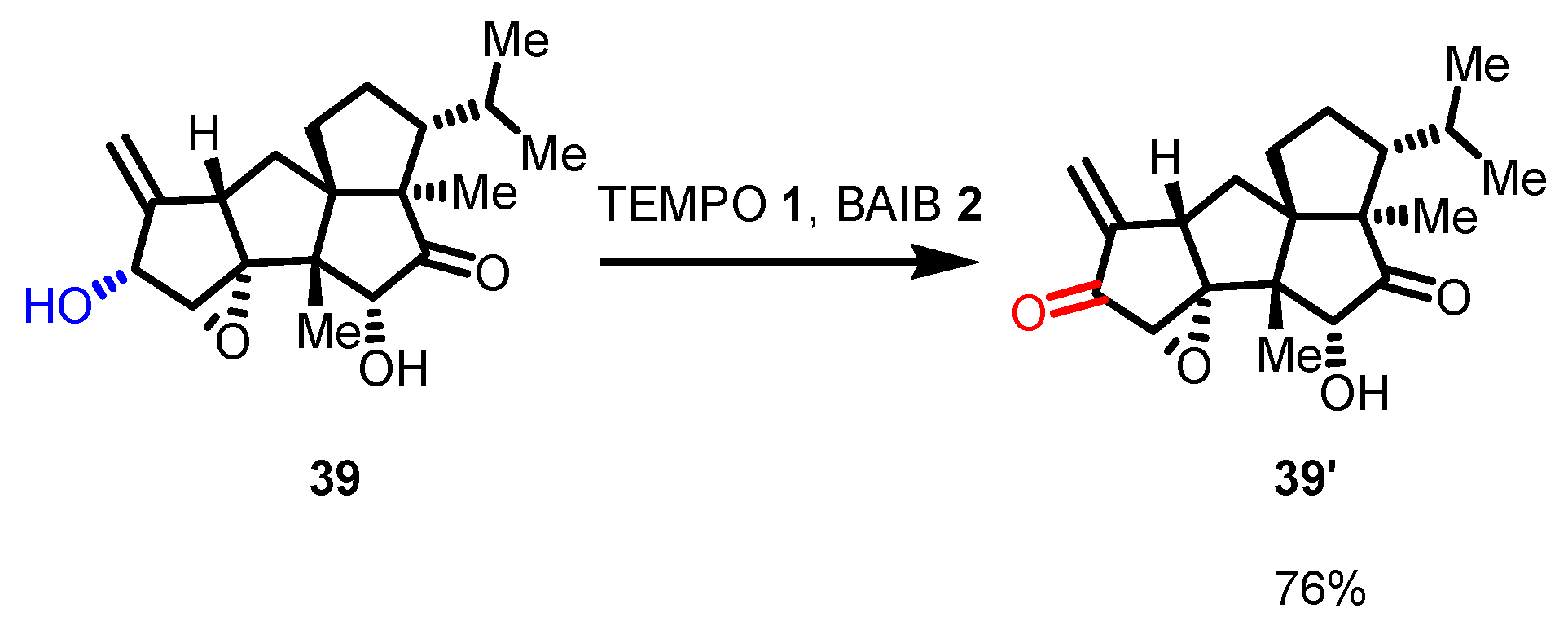

A selectivity between secondary alcohols oxidation has been reported by Hao, Ding, and co-workers in their synthesis of (−)-crinipellins [

39]. In this case, the different reactivity of the two secondary hydroxy groups on compound

39 was beacuse the allylic hydroxy group can be easily oxidized. The reaction proceeded in good yields (76%) to give enone

39’ (

Scheme 31).

A selective oxidation (primary alcohol vs secondary alcohol) was also needed by Woo and co-workers in their enantioselective synthesis of sangliferin A. These researchers installed a hydroxy group in a stereocontrolled manner on intermediate

40 [

40]. The configuration of the C36 stereocenter was correct. Unfortunately, the configuration obtained at the C35 stereocenter was the opposite of the target compound. This was not unexpected, since hydroboration would most likely have occurred on the less hindered

Re face of the C35-C36 double bond, because the

Si face of compound

42 is hindered by the methyl group in the C34 position. To solve this issue, the authors had to re-oxidize the secondary alcoholic function (and most likely also the primary one) using Dess-Martin periodinane

7 and then operate a selective reduction on compound

43. In this case, both the methyl groups on the C34 and C36 positions direct the attack of the hydride on the less hindered

Re face of the ketone on the C35 position of compound

43. Finally, the primary alcoholic function was oxidized with the standard Piancatelli-Margarita conditions to give aldehyde

43’ in 24% overall yield over four steps (

Scheme 32).

Although protective groups introduction and removal is often (but not always) high-yielding and straightforward, the addition of these two steps in a long total synthesis is better avoided, considering also the possible loss of precious material in the purification procedures. It is then more desirable to find instead a chemoselective reaction, rather than rely on protective groups.

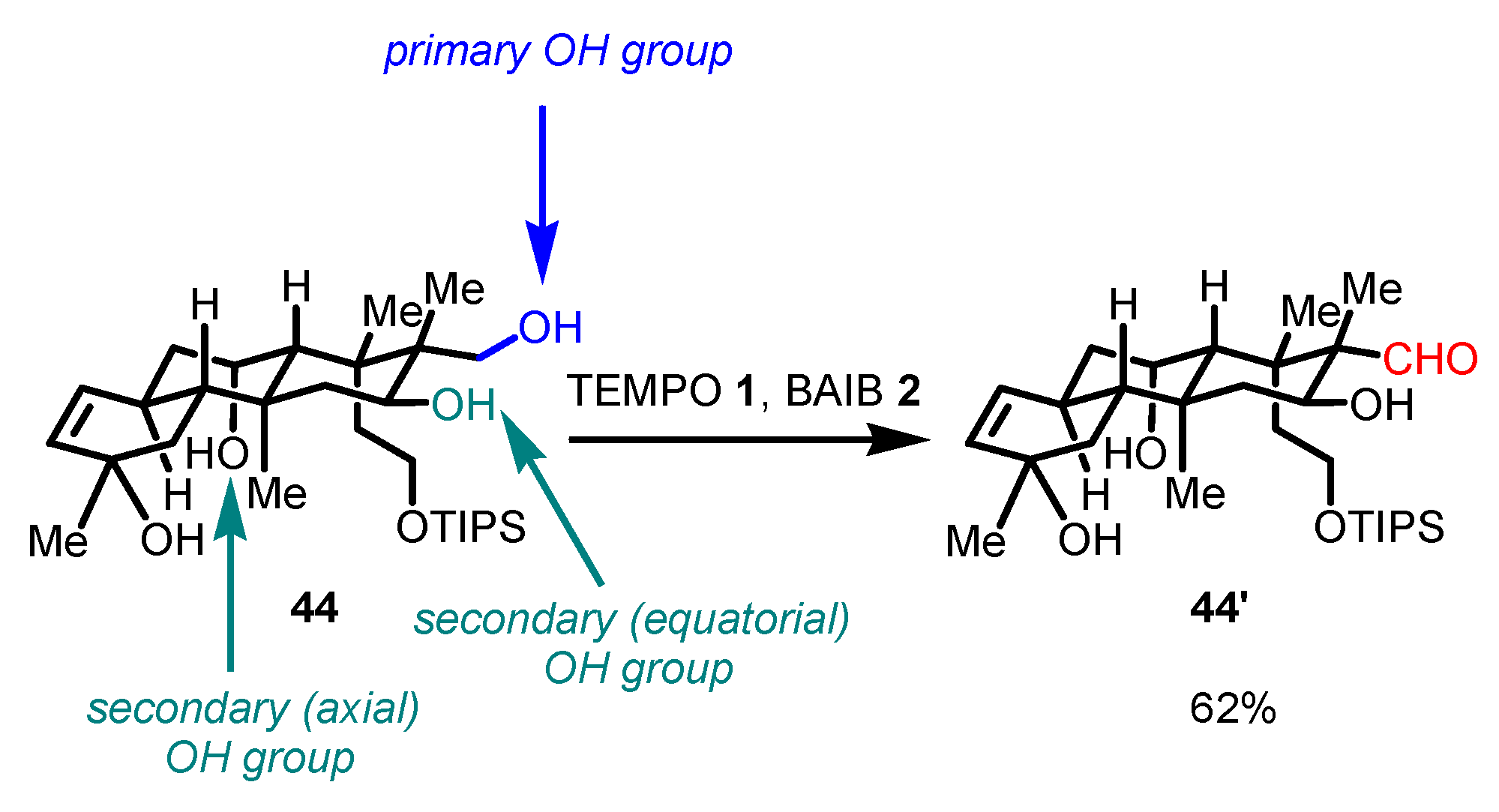

The issue of selective oxidation of a primary alcohol group in the presence of a secondary alcohol functionality was encountered by Gao and co-workers in a late synthetic step of their sequence during their efforts towards the synthesis of norzoanthamine [

41]. The problem was solved by employing the selective Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation. In this case, intermediate

44 had three different hydroxy groups: one primary hydroxy group and two secondary alcoholic groups, an axial and an equatorial one. Using the Piancatelli-Margarita reaction, it was possible to oxidize only the primary alcohol group to give aldehyde

44’ in 62% yield (

Scheme 33).

Another impressive example of selective primary hydroxy group oxidation in the presence of a secondary one at an advanced synthetic step was reported by Paterson and co-workers in their approach towards the synthesis of actinoallolides [42, 43]. Thus, the selective oxidation of alcohol

45 gave aldehyde

45’ in excellent yield (90%, see

Scheme 34).

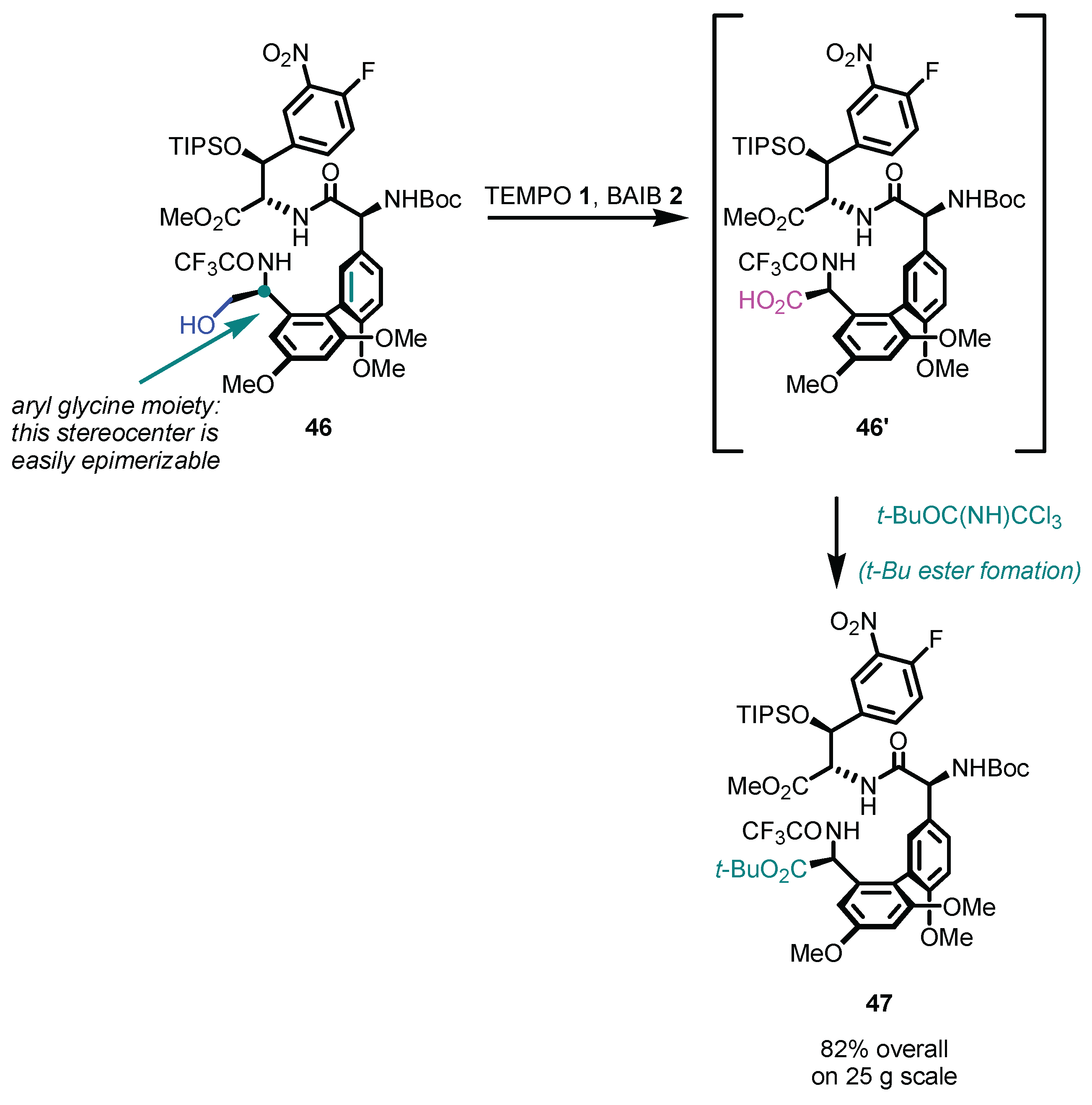

As the last example, I will present an important example of the work of Boger and co-workers in their synthesis of vancomycin and its analogue tetrachlorovancomycin [

44,

45], because it summarizes all the aspects we have encountered in this review (mild condition, selectivity, applicability in telescopic reactions applicability on large scale and on complex molecules). A late intermediate in the synthesis of vancomycin (compound

46) was subject to oxidation to carboxylic acid

46’ on an impressive 25-gram scale. A

t-butyl ester was then formed by using

t-butyl 2,2,2-trichloroacetimidate in an excellent 82 overall yield (

Scheme 35).

Scheme 1.

The Piancatelli-Margarita Oxidation reaction [

1]. .

Scheme 1.

The Piancatelli-Margarita Oxidation reaction [

1]. .

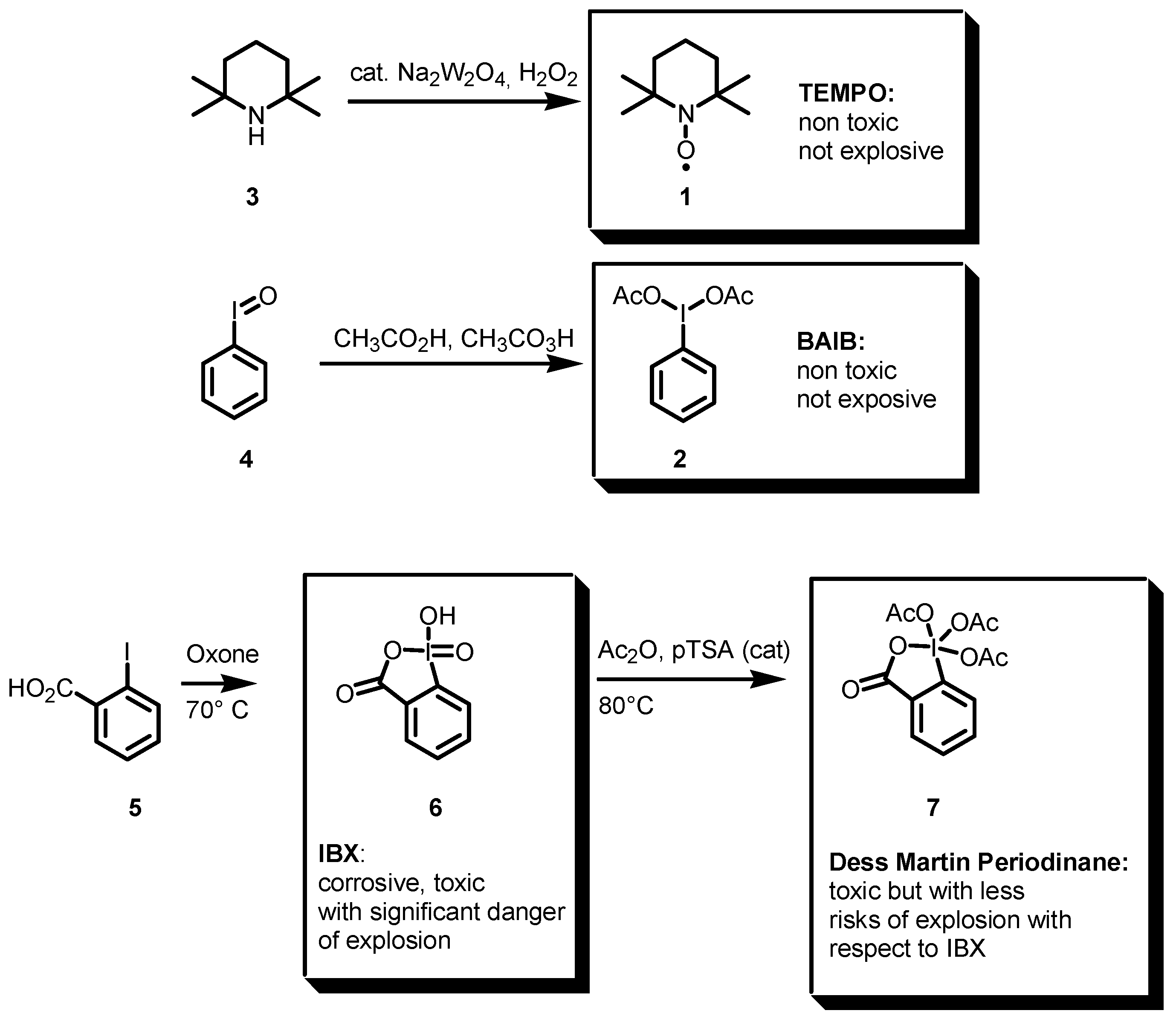

Scheme 2.

Structure of TEMPO 1, BAIB 2 and of some hypervalent iodine (III) compounds. .

Scheme 2.

Structure of TEMPO 1, BAIB 2 and of some hypervalent iodine (III) compounds. .

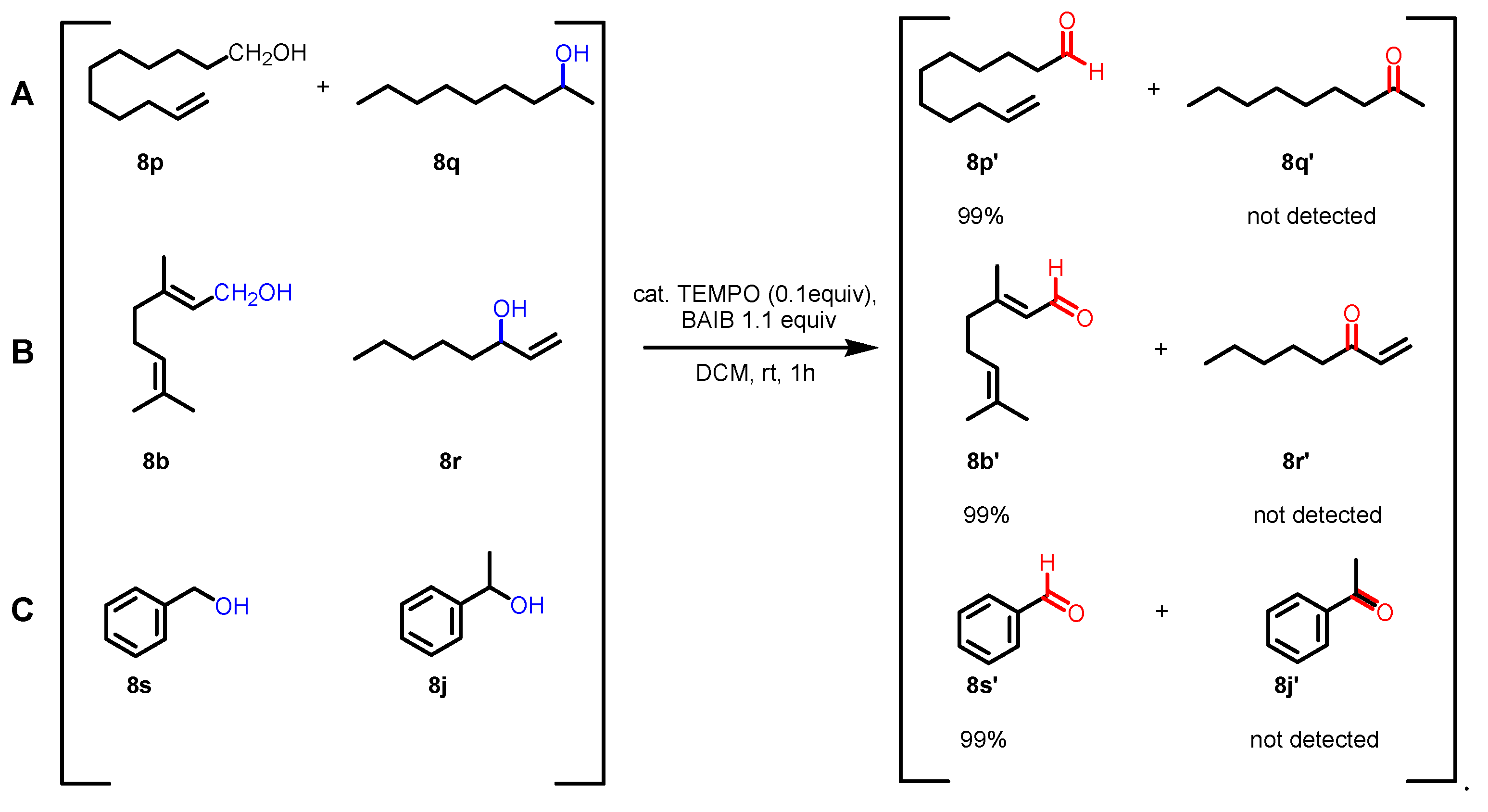

Scheme 4.

Selectivity in the Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation.

Scheme 4.

Selectivity in the Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation.

Scheme 6.

Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation of a small molecule (chloro-alcohol 9) to afford in good yield the unstable aldehyde 9’.

Scheme 6.

Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation of a small molecule (chloro-alcohol 9) to afford in good yield the unstable aldehyde 9’.

Scheme 7.

Large-scale Piancatelli-Margarita reaction of an amine bearing a thiazole unit. (Boc= t-butyloxycarbonyl-).

Scheme 7.

Large-scale Piancatelli-Margarita reaction of an amine bearing a thiazole unit. (Boc= t-butyloxycarbonyl-).

Scheme 8.

Chemoselective oxidation of the primary alcoholic function of epoxide 11 in the presence of an unprotected secondary alcohol group.

Scheme 8.

Chemoselective oxidation of the primary alcoholic function of epoxide 11 in the presence of an unprotected secondary alcohol group.

Scheme 9.

Large-scale oxidation of alcohol 12 to aldehyde 12’.

Scheme 9.

Large-scale oxidation of alcohol 12 to aldehyde 12’.

Scheme 10.

Oxidation of primary alcohol 13 in the presence of an alkyne functional group. (TMS= trimethylsilyl-).

Scheme 10.

Oxidation of primary alcohol 13 in the presence of an alkyne functional group. (TMS= trimethylsilyl-).

Scheme 11.

Oxidation of the alcoholic functionality of compound 14 without affecting the PMB (p-methoxybenzyl-) protective group.

Scheme 11.

Oxidation of the alcoholic functionality of compound 14 without affecting the PMB (p-methoxybenzyl-) protective group.

Scheme 12.

Chemoselective oxidation of the alcohol function of compound 15 despite the presence of an electron-rich aryl moiety.

Scheme 12.

Chemoselective oxidation of the alcohol function of compound 15 despite the presence of an electron-rich aryl moiety.

Scheme 13.

Oxidation of the primary alcohol in compound 16, emiaminal 16’ formation, and its oxidation to afford lactam 16’’. (Boc= t-butyloxycarbonyl-).

Scheme 13.

Oxidation of the primary alcohol in compound 16, emiaminal 16’ formation, and its oxidation to afford lactam 16’’. (Boc= t-butyloxycarbonyl-).

Scheme 14.

Oxidation of the primary alcohol in compound 17 without affecting the chloro-substituted double bond. (Fmoc= fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl-).

Scheme 14.

Oxidation of the primary alcohol in compound 17 without affecting the chloro-substituted double bond. (Fmoc= fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl-).

Scheme 15.

Selective oxidation of alcohol 18 to aldehyde 18’ in the presence of a secondary alcohol group and a double bond. (Tf= trifluoromethansulfonyl-; TBS= t-butyldimethylsilyl-).

Scheme 15.

Selective oxidation of alcohol 18 to aldehyde 18’ in the presence of a secondary alcohol group and a double bond. (Tf= trifluoromethansulfonyl-; TBS= t-butyldimethylsilyl-).

Scheme 16.

Chemoselective oxidation and lactonization of compound 19 without affecting the phenylthiol functional group.

Scheme 16.

Chemoselective oxidation and lactonization of compound 19 without affecting the phenylthiol functional group.

Scheme 17.

Oxidation of the alcoholic functionality of 20 with excess BAIB 2 or in the presence of acetic acid.

Scheme 17.

Oxidation of the alcoholic functionality of 20 with excess BAIB 2 or in the presence of acetic acid.

Scheme 18.

Oxidation and lactonization on the mixture of compounds 22a-b.

Scheme 18.

Oxidation and lactonization on the mixture of compounds 22a-b.

Scheme 19.

Tandem double bond reduction, alcohol oxidation, Wittig reaction, and DCC- (dicicyclohexyl carbodiimide) mediated lactonization on compound 23.

Scheme 19.

Tandem double bond reduction, alcohol oxidation, Wittig reaction, and DCC- (dicicyclohexyl carbodiimide) mediated lactonization on compound 23.

Scheme 20.

Tandem oxidation and Wittig reaction on compound 25. (TBS= t-butyldimethylsilyl-).

Scheme 20.

Tandem oxidation and Wittig reaction on compound 25. (TBS= t-butyldimethylsilyl-).

Scheme 21.

Two-step preparation of aldehyde 28’ from ester 27, via initial reduction to alcohol 28 and oxidation.

Scheme 21.

Two-step preparation of aldehyde 28’ from ester 27, via initial reduction to alcohol 28 and oxidation.

Scheme 22.

Axial-equatorial selectivity in Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation.

Scheme 22.

Axial-equatorial selectivity in Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation.

Scheme 23.

Possible explanation of the axial-equatorial selectivity in Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation.

Scheme 23.

Possible explanation of the axial-equatorial selectivity in Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation.

Scheme 24.

Nonselective axial-equatorial selectivity in compounds 30.

Scheme 24.

Nonselective axial-equatorial selectivity in compounds 30.

Scheme 25.

Oxidation of the primary alcohol of sugar 31 to give carboxylic acid 31’. (Bz= benzoyl-).

Scheme 25.

Oxidation of the primary alcohol of sugar 31 to give carboxylic acid 31’. (Bz= benzoyl-).

Scheme 26.

A three-step sequence for deprotection of primary alcohol, oxidation, and Me-esterification on functionalized disaccharide 33’.

Scheme 26.

A three-step sequence for deprotection of primary alcohol, oxidation, and Me-esterification on functionalized disaccharide 33’.

Scheme 27.

The oxidation of the primary alcohol on intermediate 35 to carboxylic acid 35’. (TBDPS= t-butyldiphenylsilyl-; Bz= benzoyl-).

Scheme 27.

The oxidation of the primary alcohol on intermediate 35 to carboxylic acid 35’. (TBDPS= t-butyldiphenylsilyl-; Bz= benzoyl-).

Scheme 28.

Four alcoholic functions are oxidized under modified conditions to give hexasaccharide 36’. (PMB= p-methoxybenzyl-; Cbz= benzyloxycarbonyl-).

Scheme 28.

Four alcoholic functions are oxidized under modified conditions to give hexasaccharide 36’. (PMB= p-methoxybenzyl-; Cbz= benzyloxycarbonyl-).

Scheme 29.

Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation of high molecular weight compound 37.

Scheme 29.

Piancatelli-Margarita oxidation of high molecular weight compound 37.

Scheme 30.

Primary vs secondary alcohol selectivity and lactonization in the synthesis of intermediate 38’.

Scheme 30.

Primary vs secondary alcohol selectivity and lactonization in the synthesis of intermediate 38’.

Scheme 31.

Selective oxidation of the secondary allylic function alcohol in compound 39.

Scheme 31.

Selective oxidation of the secondary allylic function alcohol in compound 39.

Scheme 32.

Selective oxidation of a primary alcohol functional group in compound 43. (TBS=t-butyldimethylsilyl-).

Scheme 32.

Selective oxidation of a primary alcohol functional group in compound 43. (TBS=t-butyldimethylsilyl-).

Scheme 33.

The selective oxidation of the primary alcohol functional group of intermediate 44 in the presence of two secondary alcohol groups. (TIPS= triisopropylsilyl-).

Scheme 33.

The selective oxidation of the primary alcohol functional group of intermediate 44 in the presence of two secondary alcohol groups. (TIPS= triisopropylsilyl-).

Scheme 34.

Selective oxidation of the primary alcohol of compound 45 to give aldehyde 45’ in excellent yields. (TMS=trimethylsilyl-; TES= triethylsilyl-).

Scheme 34.

Selective oxidation of the primary alcohol of compound 45 to give aldehyde 45’ in excellent yields. (TMS=trimethylsilyl-; TES= triethylsilyl-).

Scheme 35.

Large-scale oxidation of the alcohol functionality of compound 46 without observing epimerization of aryl glycinate and subsequent t-butyl ester formation to give intermediate 47. (Boc= t-butyloxycarbonyl; TIPS= triisopropylsilyl-).

Scheme 35.

Large-scale oxidation of the alcohol functionality of compound 46 without observing epimerization of aryl glycinate and subsequent t-butyl ester formation to give intermediate 47. (Boc= t-butyloxycarbonyl; TIPS= triisopropylsilyl-).