1. Background

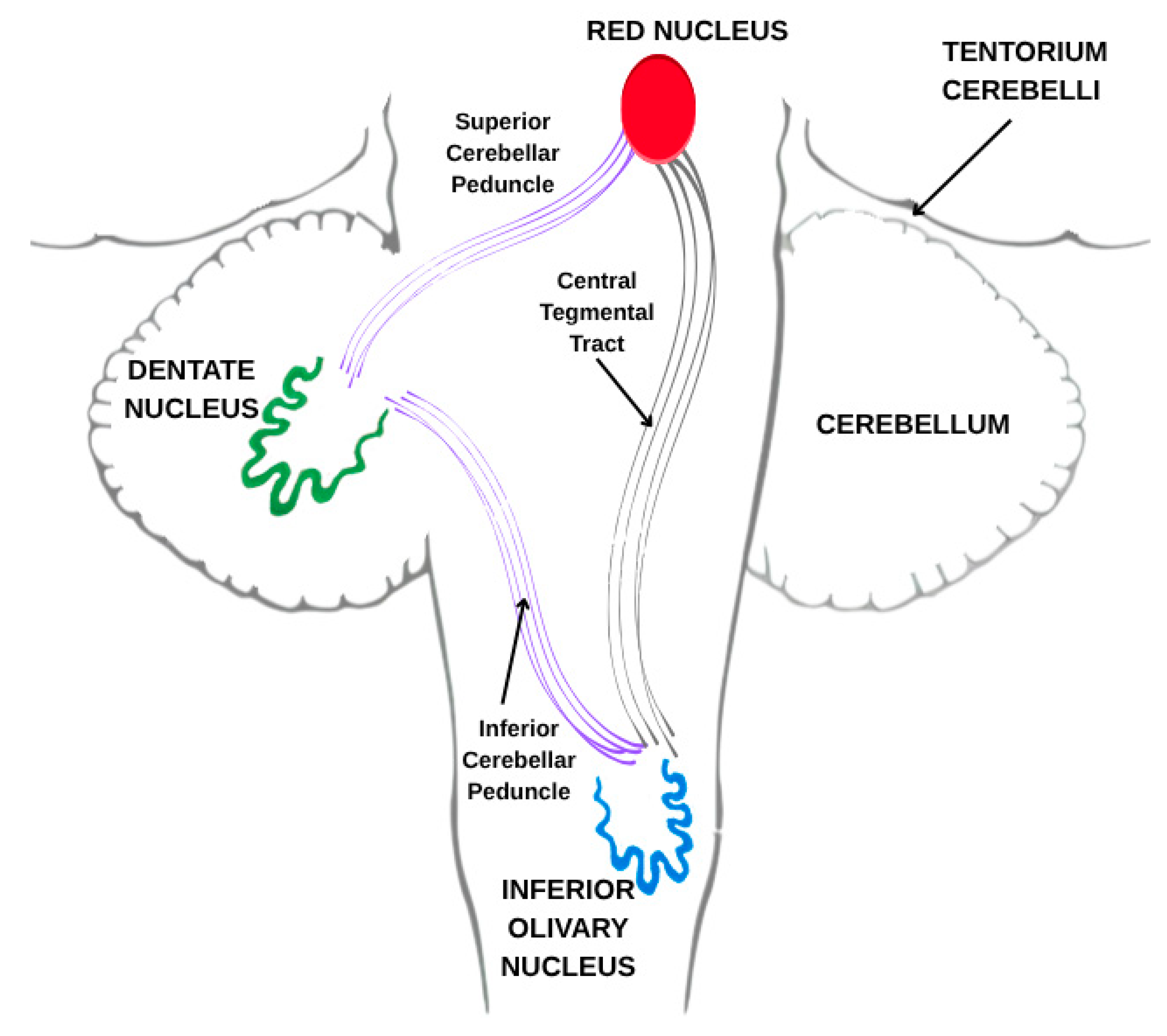

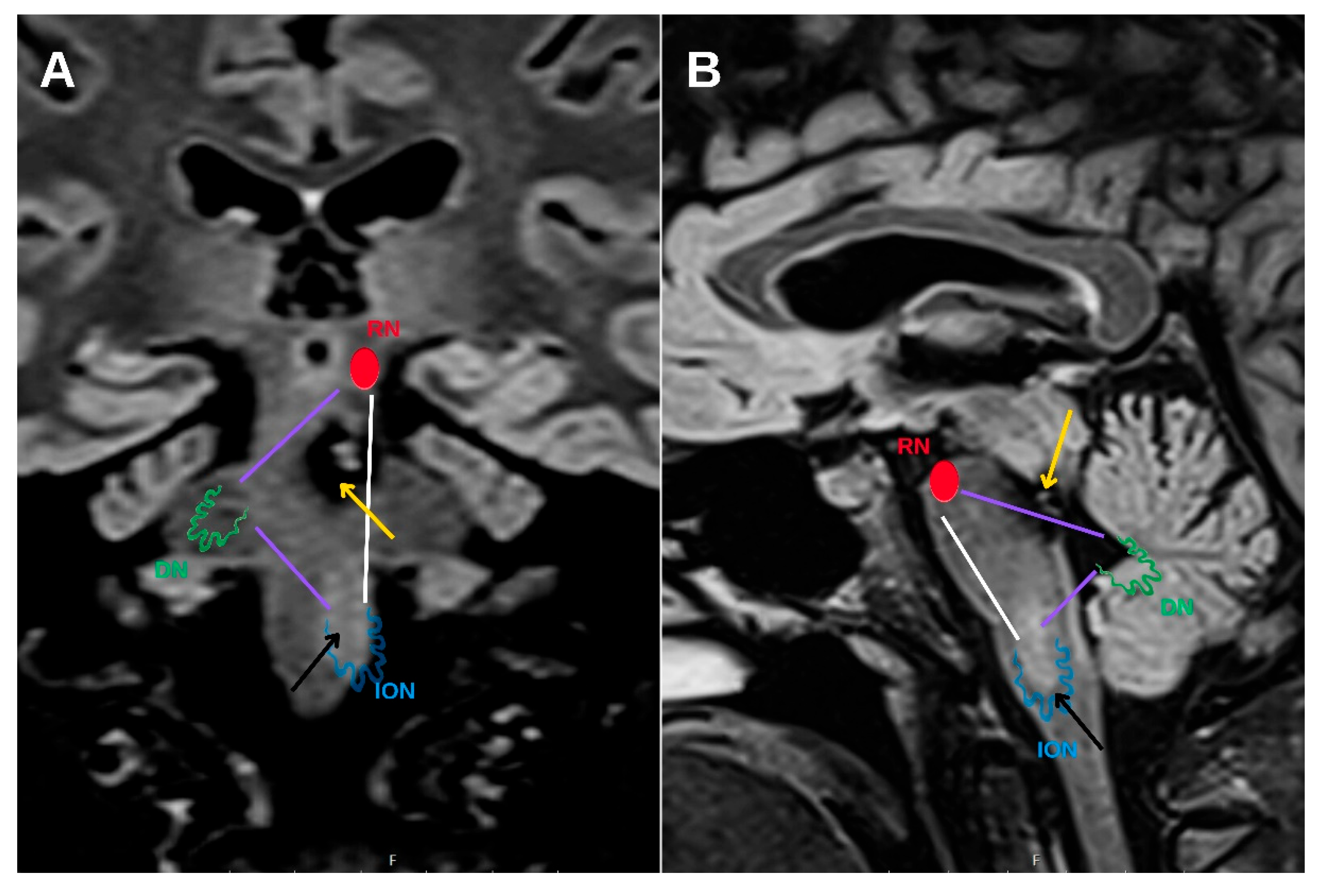

Hypertrophic olivary degeneration (HOD) is an uncommon form of trans-synaptic degeneration that affects the dentato-rubro-olivary pathway, also known as the Guillain–Mollaret triangle (

Figure 1). This neural circuit includes the red nucleus in the midbrain, the ipsilateral inferior olivary nucleus (ION) in the medulla oblongata, and the contralateral dentate nucleus of the cerebellum, interconnected via the central tegmental tract and superior cerebellar peduncle [

1]. Disruption of any component within this triangle—typically as a result of ischemic stroke, hemorrhage, surgical trauma, or demyelinating disease [

2,

3]—can lead to secondary degeneration of the ION.

Unlike most neurodegenerative processes, which are characterized by atrophy, HOD is defined by hypertrophy of the ION, often accompanied by vacuolar degeneration, astrocytic gliosis, and neuronal enlargement [

4]. This distinctive pathophysiology likely reflects a combination of denervation hypersensitivity, reactive gliosis, and impaired synaptic input, and is often associated with delayed clinical symptoms. These may include palatal tremor, ocular myoclonus, nystagmus, or other signs of brainstem dysfunction, which typically emerge weeks to months following the primary insult [

4].

MRI plays a central role in the identification and staging of HOD. The hallmark imaging features include T2-weighted and FLAIR hyperintensity within the ION, frequently accompanied by olivary enlargement in the earlier stages [

5]. These findings evolve in a predictable temporal pattern, which has been categorized into a widely used three-stage MRI classification system (

Table 1) [

6,

7]. This staging system reflects both the imaging progression and underlying histopathological changes, thereby providing a framework for interpreting longitudinal radiological findings in affected patients.

While HOD has been most reported in the setting of pontine infarction or cerebellar hemorrhage, its development following hemorrhage from a cavernous malformation (CM)—particularly in the mesencephalon—is rare and sparsely documented in the literature [

1,

3,

8,

9,

10,

11]. CMs are vascular lesions composed of dilated, thin-walled capillary channels without intervening brain parenchyma. When located within the brainstem, they pose a high risk for neurological sequelae due to the compact arrangement of critical tracts and nuclei. Hemorrhage from a mesencephalic CM has the potential to damage the central tegmental tract, thereby predisposing to the development of HOD.

Given the often-delayed onset of symptoms and the non-specific nature of olivary signal changes, recognition of HOD requires a high index of suspicion [

7,

12]. Without appropriate clinical context, the characteristic imaging findings may be misinterpreted as representing neoplastic, inflammatory, or infectious pathology. Moreover, the presence of olivary hypertrophy—rather than atrophy—can lead to further diagnostic uncertainty. Awareness of the temporal radiological evolution of HOD and familiarity with its MRI classification are therefore essential for accurate diagnosis and to prevent unnecessary investigations.

This case report presents the radiological and clinical evolution of HOD in a patient with a hemorrhage in the posterior mesencephalon near the red nucleus, highlighting the characteristic imaging features, tractographic evidence of trans-synaptic degeneration, and the relevance of staged MRI interpretation in clinical practice.

2. Case Report

A 53-year-old woman with no prior neurological history presented in December 2023 with acute-onset left-sided sensory disturbances, including facial and limb hypoesthesia, accompanied by central facial paresis and gait instability. Neurological examination revealed hypoesthesia in the maxillary (V2) and mandibular (V3) branches of the left trigeminal nerve, diminished sensation throughout the left hemibody, and impaired coordination on the ipsilateral side. Horizontal binocular nystagmus was evident during leftward gaze, and gait testing demonstrated Romberg instability. The patient remained alert and oriented, with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 15, a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 2, and a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of 2.

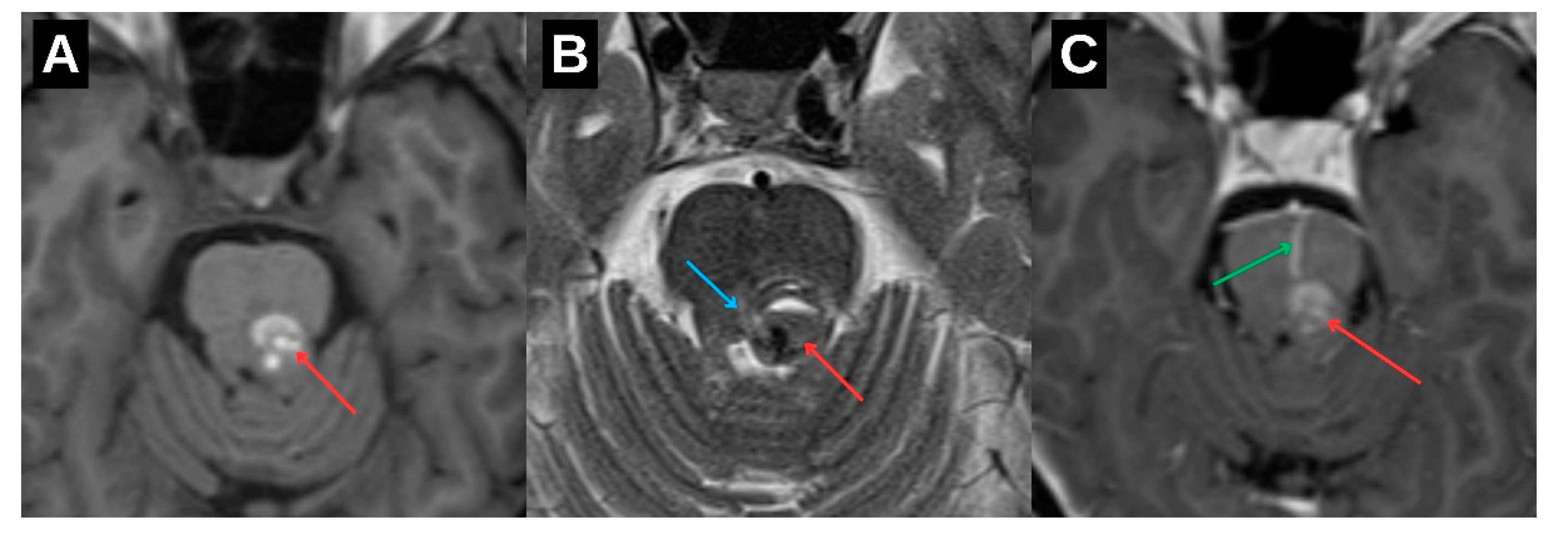

Initial neuroimaging with non-contrast computed tomography followed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a hemorrhagic lesion located in the dorsal portion of the upper brainstem, involving the left mesencephalon and extending toward the pontomesencephalic junction (

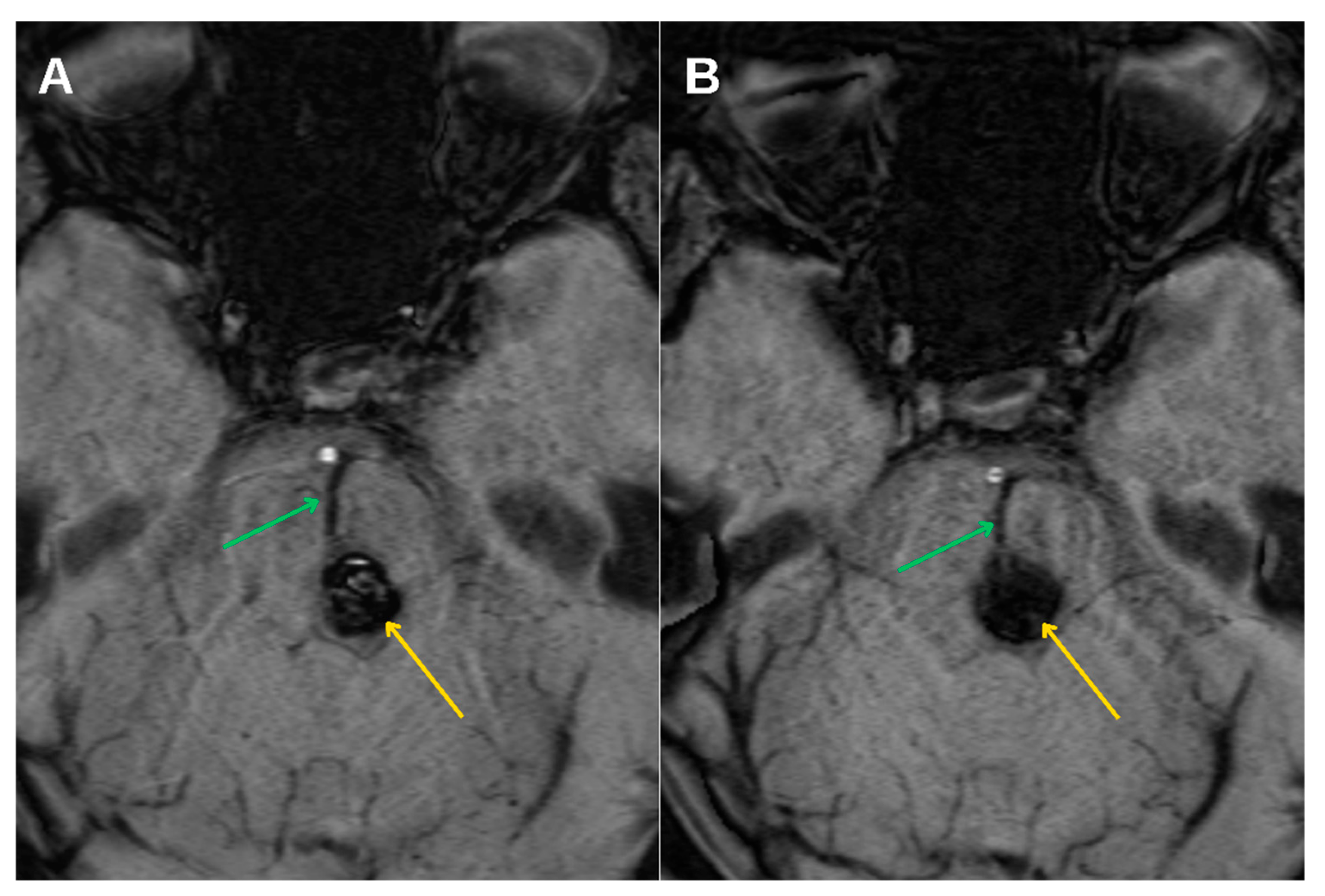

Figure 2). The lesion demonstrated imaging characteristics typical of a cavernous malformation, accompanied by a venous angioma (

Figure 3). Given the absence of acute hydrocephalus, mass effect, or clinical deterioration, a conservative therapeutic approach was adopted. The patient was managed with intravenous corticosteroids and osmotic agents to reduce perilesional edema and was initiated on symptomatic treatment with gabapentinoids to address neuropathic symptoms. No surgical intervention was indicated at that time, and the patient exhibited gradual clinical improvement.

Subsequent imaging follow-up after three months demonstrated expected interval evolution of the hemorrhagic component, with partial resorption of blood products and reduced surrounding edema. However, the patient continued to report intermittent paresthesia involving the right limbs and perioral region, suggesting persistent dysfunction along brainstem sensory pathways. A high-resolution follow-up MRI with contrast was performed six months after the initial episode, including T2-weighted, FLAIR, and susceptibility-weighted sequences, to evaluate for delayed complications.

The imaging study demonstrated a new finding of hypertrophy and T2/FLAIR hyperintensity involving the left inferior olivary nucleus. These changes were not present on initial imaging and were interpreted as consistent with evolving hypertrophic olivary degeneration (HOD). The underlying cavernous malformation remained stable in size, without signs of rebleeding, and no new lesions were identified elsewhere in the brainstem. The absence of mass effect, diffusion restriction, or contrast enhancement excluded alternative pathologies such as neoplasm, infection, or demyelination [

13,

14].

Further progression of olivary changes was noted on repeat MRI performed 1.5 years after the initial hemorrhagic event, which demonstrated continued enlargement of the inferior olivary nucleus, with the craniocaudal diameter reaching approximately 1.6 cm and anteroposterior thickness of 0.5 cm. (

Figure 4C) Signal abnormalities on T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences persisted, while no atrophy was observed. These radiological findings were consistent with Stage 2 in the traditional 3-stage classification of HOD, representing the hypertrophic phase.

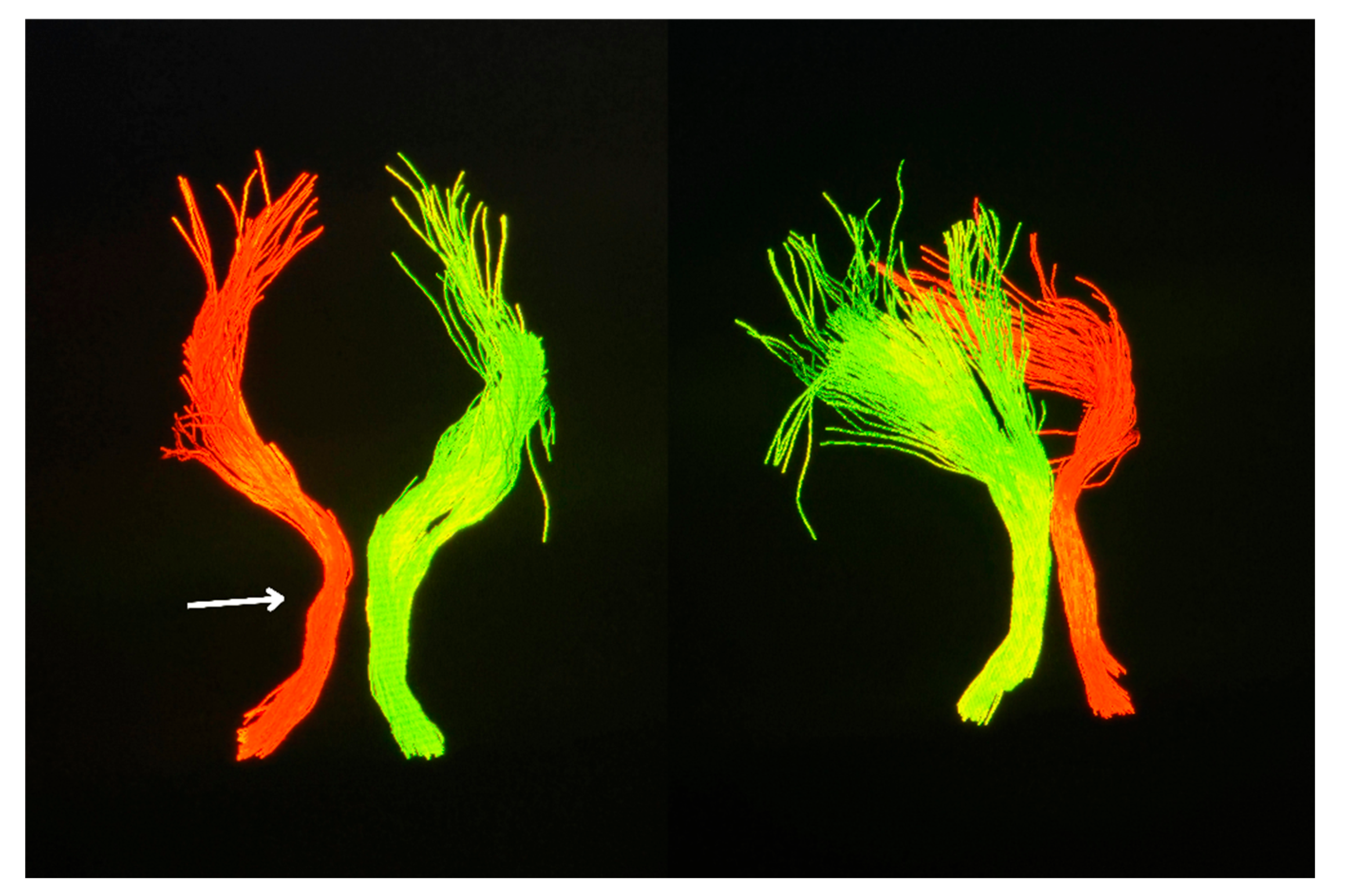

Clinically, the patient remained functionally stable with no deterioration in higher cortical function or motor strength. However, for the first time during follow-up, a palatal tremor was identified on examination—an involuntary, rhythmic movement of the soft palate—classically associated with interruption of the dentato-rubro-olivary pathway (Video S1). This clinical sign further supported involvement of the Guillain–Mollaret triangle. Complementary diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) revealed partial disruption and reduced fiber integrity in the left central tegmental tract, confirming the presence of trans-synaptic degeneration originating from the prior brainstem hemorrhage. (

Figure 5)

When considered in combination, the clinical and radiological findings established a diagnosis of hypertrophic olivary degeneration as a delayed complication of hemorrhage from a cavernous malformation in the posterior mesencephalon near the red nucleus. The temporal evolution, characteristic MRI features, and tractography abnormalities illustrated the classic progression of HOD and highlighted the importance of recognizing this entity in the context of delayed-onset neurological symptoms following brainstem injury.

3. Discussion

HOD represents a distinct form of trans-synaptic degeneration characterized by hypertrophy rather than atrophy of the ION, most frequently resulting from disruption of the dentato-rubro-olivary pathway, commonly referred to as the Guillain–Mollaret triangle [

1]. This anatomical circuit comprises the contralateral dentate nucleus, the ipsilateral red nucleus, and the ipsilateral ION, interconnected via the superior cerebellar peduncle and the central tegmental tract. Lesions affecting any component of this circuit—particularly the central tegmental tract—may lead to secondary degeneration of the ION (

Figure 6).

While the majority of HOD cases described in the literature are associated with ischemic stroke, surgical intervention, or demyelinating disease affecting the pons or cerebellum [

2,

3], development of HOD following hemorrhage due to a mesencephalic CM is rare. CMs are low-flow vascular malformations composed of thin-walled capillary channels lacking intervening brain parenchyma. When located within the brainstem, they carry a heightened risk of symptomatic hemorrhage due to the high density of functionally critical neural pathways in this region. Several cases of HOD associated with cavernous malformations have been reported in the literature; however, instances following spontaneous hemorrhage from a brainstem CM—as opposed to post-surgical or radiosurgical cases—remain exceedingly rare [

1]. In the presented case, hemorrhagic involvement of the posterior mesencephalon resulted in disruption of the central tegmental tract, thereby precipitating HOD.

The pathophysiological hallmark of HOD lies in its paradoxical hypertrophic response. Histologically, it is characterized by neuronal vacuolization, astrocytic gliosis, and neuronal enlargement. The underlying mechanism is thought to involve a combination of trans-synaptic degeneration, disinhibition, and denervation hypersensitivity. Clinically, HOD may manifest with delayed-onset neurological signs, including palatal tremor, ocular myoclonus, and nystagmus [

15]. In the current case, palatal tremor became apparent 18 months after the initial hemorrhage, during the established hypertrophic phase (stage 2) of the classical MRI-based staging system, characterized by persistent olivary enlargement and T2/FLAIR hyperintensity.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) remains the cornerstone of HOD diagnosis and staging. The condition demonstrates a predictable radiological progression: T2-weighted and FLAIR hyperintensity of the ION without hypertrophy in the early phase (stage 1), evolving into hypertrophy with persistent signal hyperintensity (stage 2), and eventually normalization or mild atrophy with persistent hyperintensity (stage 3). In this patient, serial MRI examinations at 6 months and again at 1.5 years post-hemorrhage demonstrated the expected imaging evolution. This case also provides a rare opportunity to illustrate the dynamic radiological progression of HOD over time, as visualized in

Figure 4. Such longitudinal documentation is uncommon in the literature, underscoring the value of systematic follow-up. Crucially, the absence of mass effect, contrast enhancement, or diffusion restriction helped exclude neoplastic, infectious, or demyelinating etiologies [

14].

An important adjunct in this case was diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), which demonstrated partial disruption of the left central tegmental tract. DTI-based tractography, while not routinely employed in clinical practice, offers unique value in delineating microstructural integrity and confirming trans-synaptic degeneration along the dentato-rubro-olivary pathway [

5]. In this context, it served to anatomically validate the presumed mechanism underlying the observed radiological and clinical findings.

Given the high concentration of critical neural tracts in the brainstem, cavernous malformations (CMs) in this location warrant meticulous long-term clinical and radiological follow-up. Although many brainstem CMs remain asymptomatic or present with subtle symptoms, they are associated with a significantly higher annual risk of hemorrhage compared to supratentorial lesions—particularly following an initial bleeding event. Even minor or clinically silent hemorrhages may result in irreversible damage to adjacent white matter pathways, potentially leading to delayed complications such as hypertrophic olivary degeneration. This underscores the importance of serial high-resolution MRI, not only to monitor lesion stability and detect signs of rebleeding, but also to identify secondary neurodegenerative changes in a timely manner. Follow-up strategies should be individualized based on lesion size, location, prior hemorrhagic history, and evolving symptomatology, with a low threshold for repeat imaging in the presence of new or unexplained neurological signs.

Currently, there are no disease-modifying therapies for HOD. Management is symptomatic, and interventions such as gabapentinoids, anticholinergics, or botulinum toxin have shown variable efficacy in treating palatal tremor. Stereotactic procedures may be considered in drug-refractory cases [

4,

16]. In the present case, no specific treatment for the tremor was initiated, given its limited functional impact. Nevertheless, the emergence of new neurological signs long after the initial hemorrhagic event underscores the importance of long-term clinical and radiological surveillance in patients with brainstem CMs, even in the absence of rebleeding or overt progression of the primary lesion.

In summary, this case illustrates the diagnostic significance of recognizing HOD as a delayed complication of brainstem cavernoma hemorrhage. It highlights the role of high-resolution MRI and advanced neuroimaging techniques such as DTI in confirming diagnosis and understanding pathophysiology. Increased awareness of this entity may help prevent misdiagnosis and unnecessary investigations in patients presenting with delayed-onset brainstem symptoms.

4. Conclusions

HOD is another rare and frequently underrecognized complication of brainstem injury, most commonly associated with disruption of the Guillain–Mollaret triangle. Recognition of its characteristic MRI features—particularly olivary hypertrophy accompanied by persistent T2/FLAIR hyperintensity—is essential for accurate diagnosis. This case demonstrates that hemorrhage from a cavernous malformation in the posterior mesencephalon can result in delayed trans-synaptic degeneration of the inferior olivary nucleus, with a typical temporal evolution on MRI and clinical manifestation of palatal tremor.

The findings underscore the importance of long-term clinical and radiological monitoring in patients with brainstem cavernomas, even when initial symptoms appear to resolve. Future studies may further elucidate the role of tractography in predicting and characterizing the progression of HOD, as well as the potential benefits of targeted symptomatic therapies, particularly in patients who develop tremor or other signs of brainstem dysfunction.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S., A.B. and M.R.; methodology, S.S., A.B. and M.R; software, S.S., A.B.; validation, S.S., A.B., A.K. and E.M.; formal analysis, S.S.; investigation, M.R.; resources, S.S., A.B., M.R., K.R., A.K. and E.M; data curation, S.S., A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S., A.B.; writing—review and editing, A.B., A.K.; visualization, A.B., K.R., S.S. and M.R.; supervision, A.B.; project administration, A.B.; funding acquisition, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee for Clinical Research at the Development Society of Pauls Stradins Clinical University Hospital (protocol code Nr. 300625-4L and date of approval: 30.06.2025.)

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere gratitude to Riga Stradins University, particularly the Department of Radiology, for its academic support and contributions to this research. We also extend our appreciation to Pauls Stradins Clinical University Hospital, including the Institute of Diagnostic Radiology and the Clinic of Neurology, for providing invaluable expertise, facilities, and clinical insights to our study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HOD |

Hypertrophic olivary degeneration |

| ION |

Inferior olivary nucleus |

| MRI |

Magnetic resonance imaging |

| FLAIR |

Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery |

| PD |

Proton density |

| CM |

Cavernous malformation |

| DTI |

Diffusion tensor imaging |

| CT |

Computed tomography |

| GCS |

Glasgow Coma Scale |

| NIHSS |

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale |

| mMRS |

Modified Rankin Scale |

References

- Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; et al. Hypertrophic olivary degeneration: A comprehensive review focusing on etiology. Brain Res. 2019, 1718, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eetvelde RVan Lemmerling, M.; Backaert, T.; et al. Imaging Features of Hypertrophic Olivary Degeneration. J Belg Soc Radiol 2016, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akar, S.; Drappatz, J.; Hsu, L.; Blinder, R.A.; Black, P.M.L.; Kesari, S. Hypertrophic olivary degeneration after resection of a cerebellar tumor. J Neurooncol. 2008, 87, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilikete, C.; Desestret, V. Hypertrophic olivary degeneration and palatal or oculopalatal tremor. Front Neurol 2017, 8, 272140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, D.; Gulati, Y.S.; Malik, V.; Mohimen, A.; Sibi, E.; Reddy, D.C. MRI and MR tractography in bilateral hypertrophic olivary degeneration. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2014, 24, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, M.; Versnick, E.; Tuite, P.; et al. Hypertrophic olivary degeneration: metaanalysis of the temporal evolution of MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000, 21, 1073–1077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Li, Z.; Guo, C.; et al. Hypertrophic olivary degeneration: a description of four cases of and a literature analysis. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2022, 12, 3480–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacHt, S.; Hänggi, D.; Turowski, B. Hypertrophic olivary degeneration following pontine cavernoma hemorrhage: A typical change accompanying lesions in the Guillain-Mollaret triangle. Clin Neuroradiol. 2009, 19, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asal, N.; Yılmaz, Ö.; Turan, A.; Yiğit, H.; Duymuş, M.; Tekin, E. Hypertrophic olivary degeneration after pontine hemorrhage. Neuroradiology. 2012, 54, 413–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wein, S.; Yan, B.; Gaillard, F. Hypertrophic olivary degeneration secondary to pontine haemorrhage. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2015, 22, 1213–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogan, S.N. Hypertrophic Olivary Degeneration and Holmes Tremor: Case Report and Review of the Literature. World Neurosurg. 2020, 137, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaller-Paule, M.A.; Steidl, E.; Shrestha, M.; et al. Multicenter Prospective Analysis of Hypertrophic Olivary Degeneration Following Infratentorial Stroke (HOD-IS): Evaluation of Disease Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, and MR-Imaging Aspects. Front Neurol. 2021, 12, 675123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houssni, J.E.L.; Ridah, S.M.; Jellal, S.; et al. Unusual co-occurrence of hypertrophic inferior olivary degeneration with infratentorial cavernomatosis and orbital cavernous hemangioma. Radiol Case Rep. 2024, 20, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrakchi, S.; Hsain, I.H.; Guelzim, Y.; et al. Hypertrophic olivary degeneration secondary to a Guillain Mollaret triangle cavernoma: Two case report. Radiol Case Rep. 2024, 19, 3538–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilikete, C.; Desestret, V. Hypertrophic olivary degeneration and palatal or oculopalatal tremor. Front Neurol 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menéndez, D.F.S.; Cury, R.G.; Barbosa, E.R.; Teixeira, M.J.; Fonoff, E.T. Hypertrophic Olivary Degeneration and Holmes’ Tremor Secondary to Bleeding of Cavernous Malformation in the Midbrain. Tremor and Other Hyperkinetic Movements. 2014, 4, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).