1. Introduction

Epidemiologic studies indicate a link between sleep disturbances, including short (1) and long (2) sleep duration, sleep apnea (3), insomnia (4) as well as mistimed sleep (5), and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Biological pathways implicated in the association between sleep disturbance and CVD include cardiovascular autonomic control, oxidative stress, inflammatory responses and endothelial dysfunction (6). Notably, most of the evidence is based on acute sleep deprivation, whereas the evidence for the effects of chronic sleep deprivation in healthy individuals is lacking. Mistimed sleep, has also been shown to increase cardiometabolic risk factors independently of sleep disturbance (7). Shift work, which is associated with mistimed and inadequate sleep, has also been shown to be a risk factor for CVD (8), yet the underlying mechanisms are yet to be fully understood.

The hemostatic system has a significant impact on cardiovascular morbidity (9). Impaired endothelial function is an early sign of vascular abnormality preceding clinically overt cardiovascular disease (10). The intact endothelium regulates vascular tone and repair capacity, maintaining pro-inflammatory, anti-inflammatory, and coagulation homeostasis. Alteration of these homeostatic pathways results in endothelial dysfunction before structural changes in the vasculature (11).

The relationship between sleep and the balance of endothelial function has been explored in various studies (12,13). Based on a systematic review of 24 studies, sleep deprivation, including short sleep, restricted sleep, acute total sleep deprivation, sleeping outside the 7-9-h range, and deprived sleep associated with shift work, are all associated with micro- and/or macro-vascular endothelial function (13). However, these studies are typically between-subjects’ designs and are based on single assessment methods for both sleep and endothelial function. Sleep measurements that have been used include polysomnography (14), actigraphy (12), and subjective sleep assessments (15); whereas endothelial function is typically measured as peripheral arterial tonometry (14), heart rate variability (16), or brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (FMD) (15).

Furthermore, few have examined these associations in the context of chronic shift work. A recent scoping review has suggested that the evidence of an effect of shift work on endothelial function is scarce (17). We have previously shown, in a comparative cross-sectional study design, that shift working female hospital nurses, likely not at risk for cardiovascular disease, demonstrated higher coagulation markers than their day-working counterparts. These associations were partially explained by sleep quality (18).

In order to further understand this association between endothelial and coagulation dynamics and their role in the link between sleep disturbances and cardiovascular morbidity in healthy individuals, including shift workers, it is essential to use a range of assessment tools—such as repeated measurements at different time points and a variety of endothelial and hemostatic markers.

The main objective of the present study was to assess the contribution of sleep duration measured as total sleep time (TST) and quality measured by sleep efficiency (SEF) and wake after sleep onset (WASO) on endothelial and hemostatic functions in healthy shift-working and day-working hospital nurses, at two time points, morning and evening. We hypothesized that poor sleep quality and shorter sleep duration are associated with impaired endothelial and hemostatic markers, and that these relationships are moderated by time-of-day (morning / evening hemostatic measurements) and work schedule (shift / day work).

2. Materials and Methods

Study design: The study was a prospective repeated measures design, comparing hemostatic and endothelial markers, measured in the morning and evening, and sleep duration and quality, measured over 7-14 days, in female hospital nurses working shift or daywork schedules.

Participants: The study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of Rambam Health Care Campus, No. 0303-18-RMB. Inclusion criteria consisted of female nurses age 25-50 years, body mass index (BMI) ≤30, and working at least 75% of full-time job (32 hours per week) on either regular day work or rotating day-evening-night shifts. Exclusion criteria were the presence of diabetes, hypertension, pregnancy or postpartum period, use of any chronic medications (excluding hormonal replacement treatments). Based on these criteria, nurses were identified from the Rambam Health Care Campus staff database and convenience sampling was conducted by sending out information via internal hospital communication platforms, WhatsApp, and personal correspondence. Volunteers completed a screening questionnaire including age, weight, height, chronic illness, pregnancy status, and total experience in nursing. Quota sampling was completed after recruitment of 105 nurses (53 shift workers, 52 day workers). Five nurses were subsequently excluded from analysis due to COVID-19 infection. All participants signed written informed consent.

Endothelial and Coagulation Evaluation

Reagents and antibodies: A single-chain GS3 heparanase gene construct, comprising the 8 and 50 kDa heparanase subunits (8+50), was purified from conditioned medium of baculovirus-infected cells. GS3 heparanase was assayed for the presence of bacterial endotoxin (Biological Industries, Beit Haemek, Israel) using the gel-clot technique (limulus amebocyte lysate – LAL test) and found to contain <10 pg/ml of endotoxin (19).

Endothelial function assessment. To assess endothelial status, we performed noninvasive endothelial function tests with the EndoPAT system (Itamar Medical Ltd. Caesarea, Israel), a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-cleared non-invasive test to evaluate the level of endothelial function. EndoPAT assesses digital flow-mediated dilation during reactive hyperemia using measurements from both arms – occluded side that is applied by near-diastolic external pressure and control side (20,21). EndoPAT provides an endothelial function Reactive Hyperemia Index (RHI) that is the post-to-pre-occlusion signal ratio in the occluded side, normalized to the control side. Reactive hyperemia is a well-established technique for noninvasive assessment of peripheral microvascular function and a predictor of all-cause cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (22). Low index indicates an endothelial dysfunction.

Blood coagulation parameters. Ten milliliters of blood were drawn to 3.2% citrated tubes at 6:00-9:00 and 18:00-21:00, before EndoPAT assessment. Plasma was obtained by centrifugation (1500g for 15 min at room temperature). All coagulation assays were performed on the thawed frozen plasma samples. Plasma samples were frozen after a second centrifugation at 2000g for 15 min in aliquots, at −70±5 °C. Prior to testing, plasma aliquots were thawed in a 37±0.5 °C water bath for 15 min, after which von Willebrand factor (vWF) assay was performed on the STA-R Evolution analyzer (Diagnostica Stago, Gennevilliers, France). STA-Liatest® vWF:ag kits were employed to measure vWF level. Total PAI-1 level was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with Asserachrom® PAI-1 (Diagnostica Stago, Gennevilliers, France).

Heparanase procoagulant activity assay (HPA). A basic experiment of factor Xa generation was performed in the following manner, with given concentrations as the final ones. We incubated 25 µl of the plasma, recombinant human factor VII (0.04 μM), and plasma-derived human factor X (1.4 μM) in a 50 μl assay buffer [0.06 M Tris, 0.04 M NaCl, 2mMCaCl2, 0.04%w/v bovine serum albumin, pH 8.4] to a total volume of 125 μl in a 96-well sterile plate. After 15 minutes at 37 °C, the chromogenic substrate to factor Xa was added (1 mM). After 20 minutes, the reaction was stopped with 50 μl of glacial acetic acid and the level of Xa generation was determined using an ELISA plate reader (PowerWave XS; BioTek, VT, USA). Heparins were shown to abrogate the TF/heparanase complex (23). In parallel, the same assay was performed except that fondaparinux (2.5 μg/ml) was added to the assay buffer. Bovine factor Xa diluted in the assay buffer was used to generate a standard curve. The subtraction of the first assay result from the second assay result determined Heparanase procoagulant activity (24).

Heparanase ELISA. Wells of microtiter plates were coated (18 h, 4 °C) with 2 μg/ml of anti-Heparanase monoclonal antibody 4B11 in 50 μl coating buffer (0.05 M Na2CO3, 0.05 M NaHCO3, pH 9.6). The plate was covered with adhesive plastic and incubated overnight at 4°C. The next day, wells were blocked with 2% BSA in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature (23°C). Diluted samples (100μl) were loaded in duplicates and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature, followed by the addition of 100 μl polyclonal antibody 63 IgG (1 μl/ml) for an additional period of 2 hours at room temperature. HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:20,000) in blocking buffer was added (1 hour, room temperature) and the reaction was visualized by the addition of 100 μl chromogenic substrate (TMB; MP Biomedicals, Berlin, Germany) for 15 minutes. The reaction was stopped with 100 μl H2SO4 and absorbance at 450 nm was measured using the ELISA plate reader. Plates were washed four times with washing buffer (PBS, pH 7.4 containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20) after each step. As a reference for quantification, a standard curve was established by serial dilutions of recombinant 8+50 GS3 Heparanase (390 pg/ml-25 ng/ml) (25).

Study Procedures

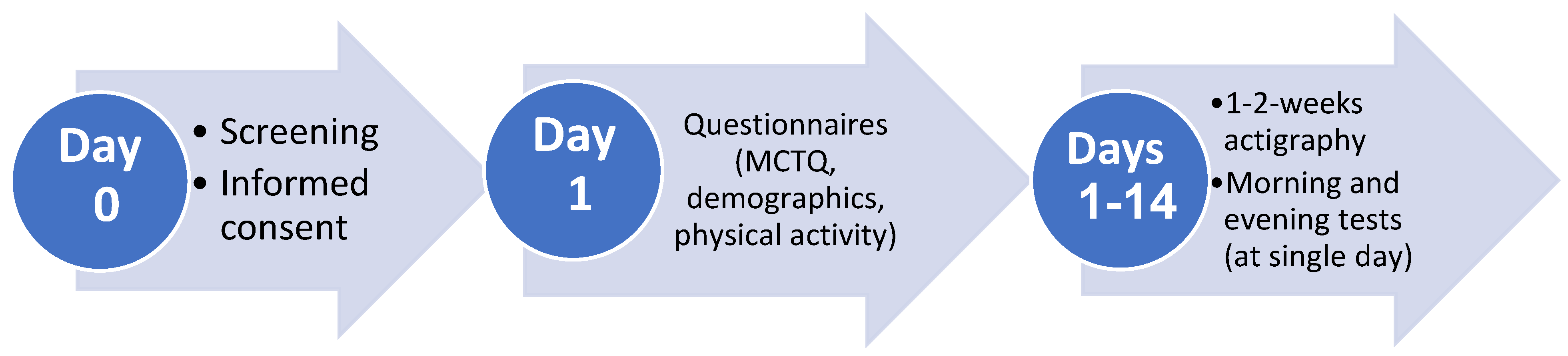

Figure 1 presents the study timeline. Within 48-hrs after recruitment and informed consent, demographic and clinical questionnaires were completed and Actiwatches were handed to participants. The latter were worn on the non-dominant wrist for a 1-2-week period with concurrently completed daily sleep logs, which were used to determine time in bed. During this period of activity monitoring, participants underwent EndoPAT testing, followed by blood drawing, on a day when they were scheduled for a morning shift (day and shift workers) or an evening shift (shift workers). Morning measurements were conducted between 6:00-9:00 and evening measurements were conducted between 18:00-21:00 within 24-hrs, in the Thrombosis and Hemostasis Unit at Rambam Health Care Campus by a qualified nurse.

Statistical Analysis

Data was analyzed using SPSS software for Windows, version 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA). Means and standard deviations along with skewness and kurtosis were computed for continuous variables and frequency and percent were computed for categorical data. For the sleep parameters, both means and standard deviations were averaged per participant.

Descriptive statistics were computed for demographic data, sleep parameters and hemostatic markers of the entire sample and compared by work schedule group type using the chi-square test of independence for categorical data and t-test for continuous variables. Pearson’s correlation was used to assess the relationship between all sleep parameters and endothelial markers. False detection rate (FDR) was used to correct for multiple correlations. As TST was not correlated with any of the endothelial outcomes, it was not included in the subsequent analyses.

Multiple regression was performed to predict markers of endothelial function by work schedule (day/shift), time of measurement (morning/evening), and average sleep measures separately (SEF, WASO), and 2- and 3-way interactions, controlling for age. Models were performed for morning and evening endothelial function measurements separately, unless no significant difference was found between the two time points. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

Sleep parameters were approximately normally distributed as assessed by skewness and kurtosis (not shown). The coagulation tests were also approximately normally distributed except for heparanase procoagulant activity (HPA). Log transformation of HPA was performed in order to make the data more symmetric.

One hundred nurses (mean age 39.6±7.6) participated. Sleep episodes per 24-hrs were recorded for an average of 9 consecutive days (SD: 2.6; range 4-14). A total of 15 participants had follow-up periods shorter than 7 days (ranging from 4 to 6 days). Of these, 2 participants had data for 4 days due to a technical malfunction in the watch, while 13 participants wore it for 5–6 days due to compliance issues. Per all 873 sleep episodes, TST ranged from 1.15 to 15.8 hours (mean 6.43 hours, SD:1.84 hours), SEF ranged from 54.8% to 99.9% (mean 85.5%, SD: 6.1%), WASO ranged from 0 to 131 minutes (mean 33.5 min., SD:17.3 min). Mean averaged TST per participant was 6.48 (SD: 0.93, range 4.44-9.40). Mean averaged SEF per participant was 85.7% (SD: 3.8, range 78.6-95.4%). Mean averaged WASO per participant was 33.5 minutes (SD: 10.3, range 11.6-55.9 minutes). Over all nurses, 28% slept on average less than 6 hours a night (12 day workers, 16 shift workers), 42% had SEF less than 85% (14 dayworkers, 28 shift workers) and 93% had WASO greater than 20 minutes [60% more than 30 minutes WASO].

Table 1 presents demographics, sleep parameters and the hemostatic tests for all nurses and by work schedule (shift/day). Nurses who worked shifts were 8.7 years younger (mean difference: 8.7 years, se: 1.2 years; 95% CI: 6.2-11.1 years younger) and worked 9.6 fewer years (mean difference: 9.6 years, se: 1.3 years; 95% CI: 7.0-12.2 fewer years) than their day shift counterparts. After adjusting for age nurses who worked shifts worked nearly 2 years fewer than their day shift counterparts (F (1, 97) =4.77, p=.03; mean difference 1.97 fewer years, se: 0.90, 95% CI: 0.18-3.77 fewer years).

There was no statistically significant difference in average TST between shift and day workers (mean difference of 6 minutes) Average SEF was lower in shift compared to day workers (mean difference: -2.06%. se: 0.7%; 95% CI: -3.5- -0.6%) but this is not a clinically meaningful difference. Similarly, there was no statistically significant difference in average WASO (mean difference 2.9 min). After adjusting for age, there was no significant difference in SEF (F (1, 97) =1.29, p=.26).

There was a statistically significant difference in RHI (FDR corrected p<.001) and PAI-1 (FDR corrected p=.048) evening levels, with shift workers having significantly lower evening RHI (mean difference: -0.182, se: .051; 95% CI: -.285- -.080), higher evening PAI1 (mean difference: 2.75, se:1.03; 95% CI: 0.70-4.80). Shift workers tended to have higher morning and evening Heparinase and morning HPA (FDR corrected p’s <.082). After adjusting for age there remained a statistically significant difference in evening RHI (F (1, 97) =4.29, p=.04) and PAI-1 (F (1, 97) =8.20, p=.005), but not morning Heparanase ELISA (F (1, 97) =0.35, p=.56) or morning Heparanase Procoagulant Activity (F (1, 97) =0.16, p=.69).

Correlations Between Sleep Parameters and Endothelial Markers for Whole Sample

Significant correlations were maintained following FDR for correlations between sleep parameters and endothelial markers for whole sample. Pearson correlations (

Table 2) revealed that TST was not correlated with any endothelial marker. SEF was statistically significantly positively correlated with both morning and evening RHI and statistically significantly negatively correlated with both morning and evening PAI-1, Heparanase ELISA and HPA. WASO was negatively correlated with morning and evening RHI and positively correlated with both morning and evening PAI-1, Heparanase ELISA and was not correlated with heparanase procoagulant activity.

After correcting for age, SEF was positively correlated with both morning and evening RHI (r= morn: r= .290, p=.004; even: r= .355, p<.001) and negatively correlated with both morning and evening PAI-1 (morn: r=-.696, p<.001; even: r= -.529, p<.001) and heparanase (morn: r=-.389, p<.001; even: r= -.338, p<.001) and proactive coagulant Heparanase (morn: r=-.391, p<.001; even: r= -.361, p<.001). WASO was positively correlated with both morning and evening PAI-1 (morn: r=.575, p<.001; even: r= .385, p<.001), Heparanase ELISA (morn: r=.334, p<.001; even: r= .331, p<.001) and HPA (morn: r= .340, p<.001; even: r=.355, p<.001).

In summary, as we predicted poor sleep quality as denoted by low SEF and high WASO were correlated with poor endothelial function (lower RHI) and elevated coagulation markers.

As TST was not correlated with any of the endothelial markers, regression models were performed only with SEF and WASO.

Multiple Regression Models:

RHI:

SEF: A main effect was found for SEF, so that increased SEF was significantly associated with increased average RHI. Although the time by SEF interaction was not statistically significant, it should be noted that an association between SEF and RHI was found in the evening RHI (b=.029, se: .011, p=.011, 95% CI: .007 to .051) but not morning RHI (b=.018, se: ,011, p=.10, 95% CI: -0.004 to .041). For every 5% increase in SEF, evening RHI increased by 0.145.

No main effects were found for time of measurement or shift pattern, and no 2- or 3-way interactions were found.

WASO: A significant main effect was found for WASO so that increased WASO was associated with decreased average RHI (b=-.005, se: ,002, p=.010, 95% CI: -0.009 to -.001). For every 20-minute increase in WASO RHI decreased by 0.100 units.

No main effects were found for time of measurement or shift pattern, and no 2- or 3-way interactions were found.

PAI-1:

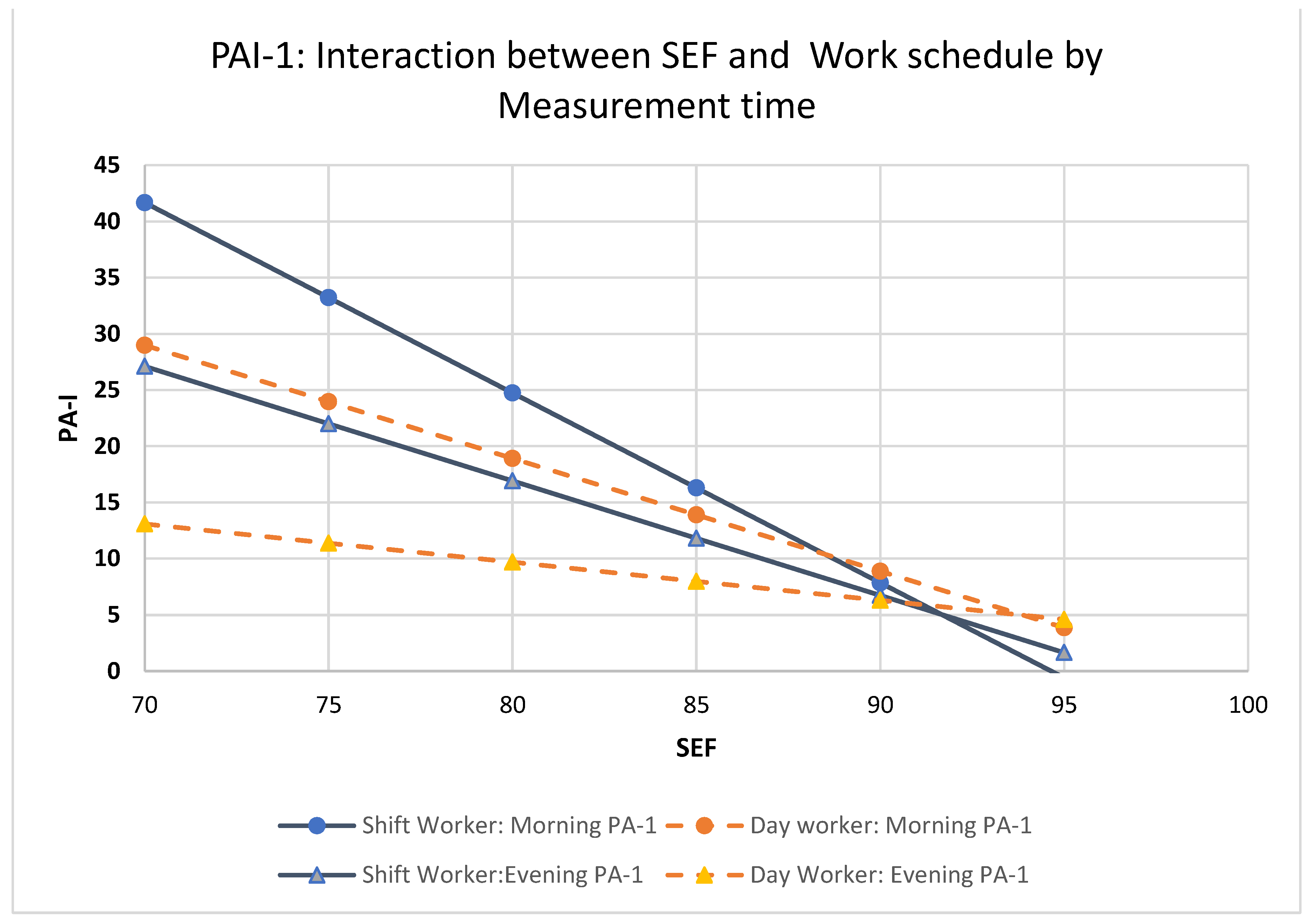

SEF: Main effects were found for time of measurement, shift pattern and SEF; there was a 2-way interaction between time of measurement and SEF and shift by SEF but no three-way interaction between time of measurement, shift and SEF. Post hoc analysis (see

Figure 2) revealed that for day workers, both morning PAI-1 (b=-1.004, se: .161, 95% CI: -1.328 to -0.681 p<.001) and evening PAI-1 (b=-0.344, se: .148, 95% CI: -0.642 to -0.047 p=.024) declined with increasing SEF. Among day workers, for every 5 percent increase in SEF morning PAI-1 decreased by 5.02 units whereas evening PAI-1 decreased by 1.72 units. Morning PAI-1 slope was statistically significantly different as compared to evening PAI-1 slope (t=3.02, p=.003). Increasing SEF had greater impact on PAI-1 decrease in the morning as compared to the evening.

Similarly, for shift workers, both morning PAI-1 (b=-1.686, se: .240, 95% CI: -2.169 to -1.202 p<.001) and evening PA (b=-1.054, se: .188, 95% CI: -1.432 to -0.675 p<.001) declined with increasing SEF. Among shift workers for every 5 percent increase in SEF morning PAI-1 decreased 8.43 units whereas evening PAI-1 decreased by 5.27 units. Morning PAI-1 decline was statistically significantly different as compared to evening PAI-1 (t=2.07, p=.039).

WASO: Main effects were found for time of measurement, shift pattern, and WASO. In addition, there were 2-way interactions between time of measurement and WASO, and shift pattern and WASO. There was no 3-way interaction. For morning PAI-1, a main effect was found for WASO (b=.216, Se:.099, p=0.033, 95% CI: 0.02 to 0.41) and there was an interaction between shift pattern and WASO (night shift b=.309, se:.124, p=0.014, 95% CI: .064 to 0.56). For day workers a 20 min increase in WASO resulted in a 4.32-unit increase in morning PAI-1 whereas in night shift workers a 20 min increase in WASO resulted in a 2.32-unit increase in morning PAI-1.

For evening PAI-1, an interaction was found between shift pattern and WASO (Night shift: b=.265, se: .098 p=.008, 95% CI: .07) such that a 20 min increase in WASO resulted in a 0.32-unit increase in evening PAI-1. There was no association between WASO and evening PAI-1 for day workers.

Heparanase ELISA

There were no differences between morning and evening Heparanase ELISA measurements.

SEF: A main effect was found for SEF. There was no SEF by shift interaction. Increased SEF was significantly associated with a decrease in Heparanase ELISA (b=-134.70 se=34.74, p<.001, 95% CI: -203.65 to -65.74). For every 5 % increase in SEF Heparanse Elisa decreased by 673.5 (pg/mL).

WASO: A main effect was found for WASO. There was no WASO by shift interaction. Increased WASO was significantly associated with an increase Heparanase ELISA (b=44.08 se=12.41, p<.001, 95% CI: 19.44 to 68.71). A 20-minute increase in WASO was associated with an 881.6 (pg/mL) unit increase in Heparanase ELISA.

Heparanase Procoagulant Activity (HPA)

There were no differences between morning and evening (log) Heparanase Procoagulant Activity measurements.

SEF: A main effect was found for SEF. There was no interaction between shift and SEF. A 5% increase in SEF resulted in a -0.10 decrease in the log of HPA (b=-.020, se: -0.03 to -0.01).

WASO: A main effect was found for WASO; there was no 2-way interaction between shift and WASO. Increased WASO was significantly associated with increased HPA (b=.007, se: .002, 95% CI: .003 to .010). A 20-minute increase in WASO was associated with a 0.14 increase in the log of HPA.

VWF: There was no main effect of time, shift type nor was there a main effect of either of the sleep variables.

4. Discussion

The present research explores for the first time the associations between sleep parameters and vascular function measured in the morning and evening considering possible diurnal variation of endothelial and coagulation markers, and using different methods of evaluation of endothelial function. We hypothesized that an association would be observed between sleep measures and endothelial coagulation markers, reflecting a potential link between sleep quality and vascular health. Our findings support this hypothesis and provide important insights into the relationship between sleep and endothelial function. In line with study hypotheses, we found associations between sleep measures and endothelial and coagulation markers, and these associations interacted with work schedules (shift/day), and time-of-day of the measurements (morning/evening).

First, we found that poor sleep quality, specifically SEF and WASO were associated with impaired endothelial and coagulation markers such as reactive hyperemia index (RHI), plasmin activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) and heparanase - markers that reflect both functional and structural changes in vascular health. Findings support a cross-sectional study that reported that lower actigraphy based sleep efficiency (but not sleep duration or subjective sleep quality) was associated with impaired endothelial function measured by brachial FMD (26).

Endothelial function as measured by the Reactive Hyperemia Index (RHI, EndoPAT) showed reduction in vascular responsiveness in individuals with impaired sleep and such tendency was observed at both morning and evening measurements. Higher SEF was significantly linked to increased evening RHI, suggesting better endothelial function later in the day among individuals with more consolidated sleep. Although the time by SEF interaction was not statistically significant overall, the evening-specific association (b = 0.029, p = 0.011) indicates that improvements in sleep efficiency may have a more pronounced benefit on vascular reactivity during the evening compared to the morning. This aligns with emerging evidence showing that sleep quality, particularly efficiency, plays a crucial role in cardiovascular health through mechanisms involving endothelial function (27), and even mild sleep restriction may increase endothelial oxidative stress in female persons (28). Conversely, increased WASO was associated with decreased average RHI (b = -0.005, p = .010), further reinforcing that fragmented sleep may impair endothelial responsiveness, potentially elevating cardiovascular risk.

PAI-1 as a fibrinolysis suppressor and prothrombotic enzyme was negatively correlated with sleep quality. The present findings as in our previous study (18, 29) underscore an association between sleep quality parameters, SEF and WASO, and levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), with both circadian timing and shift schedule playing significant moderating roles. Both day and shift-working nurses showed statistically significant declines in PAI-1 levels with increasing SEF, with a stronger effect observed in the morning samples. Notably, a 5% increase in SEF was associated with a reduction of 5.02 units in morning PAI-1 among day workers and 8.43 units among shift workers, indicating greater vulnerability of shift workers to sleep-related hemostatic dysregulation. These findings are consistent with prior studies reporting elevated PAI-1 levels among shift-working nurses compared to daytime workers, suggesting subclinical coagulation activation likely due to circadian misalignment and chronic sleep disruption (18,29). Similarly, increased WASO was positively associated with morning PAI-1, particularly in night-shift nurses, further supporting a link between fragmented sleep and prothrombotic changes. Elevated PAI-1 levels in the morning - especially among shift workers - highlight the role of disrupted sleep and circadian misalignment in creating a prothrombotic state (30). These hemostatic response of PAI-1 to poor sleep may represent early biomarkers of increased cardiovascular risk in this occupational group (31), warranting further investigation into interventions that promote sleep continuity and circadian alignment in shift-working nurses. These PAI-1 finding were consistent with our previous report (18) when we described the association between coagulation markers and sleep quality

Heparanase, a marker of endothelial glycocalyx degradation, was significantly higher in shift workers during both time points, reinforcing our hypothesis that sleep insufficiency may contribute to endothelial damage. To our knowledge, it was the first time when heparanase markers evaluated at morning and evening hours in order to explore diurnal dynamics of the markers. In this study, both Heparanase ELISA and Heparanase Procoagulant Activity (HPA) were significantly associated with sleep parameters, SEF and WASO. Increased SEF was significantly linked to lower Heparanase ELISA levels and reduced HPA, suggesting that better sleep continuity may suppress heparanase expression and its procoagulant effects. Conversely, higher WASO, indicative of more fragmented sleep, was associated with elevated levels of both Heparanase ELISA and HPA, reinforcing the role of disrupted sleep in enhancing procoagulant activity. These findings are consistent with previous research indicating elevated heparanase levels in shift-working nurses compared to daytime workers, potentially contributing to increased cardiovascular risk in this population (18). Experimental studies have also shown that sleep fragmentation increases sympathetic nervous system activity (32) and cortisol levels (33), promoting metabolic and hemostatic dysregulation (34). These physiological stress responses could upregulate heparanase, known to enhance tissue factor activity and initiate coagulation cascades. Together, these findings underscore the potential mechanistic link between impaired sleep and heightened coagulation risk via heparanase pathways, emphasizing the need for targeted sleep interventions among healthcare shift workers to mitigate cardiovascular risk.

These results align with previous research (18, 29) suggesting that poor sleep may contribute to endothelial and coagulation dysregulation, potentially mediated through increased inflammatory (35) and coagulation responses (36). Sleep duration (TST) was not in any association with endothelial and coagulation markers at any time of day.

In line with previous findings, elevated levels of von Willebrand factor (VWF) - a large multimeric glycoprotein secreted by endothelial cells involved in platelet adhesion - may reflect endothelial activation (37) and an increased prothrombotic state, highlighting a potential mechanism contributing to elevated cardiovascular risk (38). Surprisingly, no significant associations were found for sleep parameters and VWF in our present study. These discrepancies may be due to small sample size and due to relatively young age of participants (39.6±7.6). However general population studies have described a weak association between plasma VWF and the risk of CVD (39), on the other hand it is considered significant risk marker for CVD in older adults (40).

The findings of multiple regression underscore the significance of sleep quality in influencing vascular and procoagulant biomarkers among nurses. Higher SEF was associated with improved endothelial function. This aligns with recent research suggesting that better sleep continuity enhances cardiovascular recovery and reduces pro-thrombotic states (41). Conversely, increased sleep fragmentation (WASO) was consistently linked to adverse outcomes, including decreased RHI and elevated PAI-1, Heparanase, and HPA levels, which are all markers of impaired vascular health and heightened thrombotic risk. These results are supported by prior evidence indicating that fragmented sleep is associated with systemic inflammation (42) and endothelial dysfunction (43). The differential effects observed between morning and evening measurements suggest potential diurnal variability in biomarker responses to sleep parameters, emphasizing the importance of temporal context in interpreting physiological data.

By focusing on healthy participants, the study establishes a baseline understanding of physiological norms, enabling earlier detection of endothelial dysfunction related to sleep disturbances. This could lead to innovative screening tools or lifestyle interventions aimed at improving cardiovascular health.

However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of our study. These include the small sample size, with a specific focus only on healthy female nurses. In addition, 93% of the nurses (shift and day workers) had WASO over 20 minutes indicating that most of the sample had poor sleep quality. This calls into question how representative the sample was, or alternatively, whether the 20-min benchmark for WASO should be used in this setting. Moreover, sleep quality was measured at the time of or after blood collection. To establish causality, sleep measurements should have been done prior to blood collection. However, sleep measurements were performed in nurses’ ecological setting and we considered them to represent their typical sleep.

In conclusion, our findings underscore the importance of adequate sleep in maintaining vascular health. The observed associations between sleep measures and endothelial function and coagulation activation suggest a possible pathway through which sleep disruption may contribute to further cardiovascular risk. Further research is needed to elucidate these mechanisms and explore potential interventions to mitigate vascular health risks associated with poor sleep.

Acknowledgments

Statistical support was provided by Paula S., Herer (Biostatistician MSc., MPH), whose expertise greatly contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data.

References

- Badran, M., Yassin, B. A., Fox, N., Laher, I., & Ayas, N. (2015). Epidemiology of Sleep Disturbances and Cardiovascular Consequences. The Canadian journal of cardiology, 31(7), 873–879. [CrossRef]

- Sabanayagam, C., & Shankar, A. (2010). Sleep duration and cardiovascular disease: results from the National Health Interview Survey. Sleep, 33(8), 1037–1042. [CrossRef]

- Salari, N., Khazaie, H., Abolfathi, M., Ghasemi, H., Shabani, S., Rasoulpoor, S., Mohammadi, M., Rasoulpoor, S., & Khaledi-Paveh, B. (2022). The effect of obstructive sleep apnea on the increased risk of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurological sciences : official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology, 43(1), 219–231. [CrossRef]

- Sofi, F., Cesari, F., Casini, A., Macchi, C., Abbate, R., & Gensini, G. F. (2014). Insomnia and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. European journal of preventive cardiology, 21(1), 57–64. [CrossRef]

- Tobaldini, E., Costantino, G., Solbiati, M., Cogliati, C., Kara, T., Nobili, L., & Montano, N. (2017). Sleep, sleep deprivation, autonomic nervous system and cardiovascular diseases. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 74(Pt B), 321–329. [CrossRef]

- McHill, A. W., Melanson, E. L., Wright, K. P., Jr, & Depner, C. M. (2024). Circadian misalignment disrupts biomarkers of cardiovascular disease risk and promotes a hypercoagulable state. The European journal of neuroscience, 60(7), 5450–5466. [CrossRef]

- Wong, P. M., Hasler, B. P., Kamarck, T. W., Muldoon, M. F., & Manuck, S. B. (2015). Social Jetlag, Chronotype, and Cardiometabolic Risk. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, 100(12), 4612–4620. [CrossRef]

- Wong, R., Crane, A., Sheth, J., & Mayrovitz, H. N. (2023). Shift Work as a Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factor: A Narrative Review. Cureus, 15(6), e41186. [CrossRef]

- Lowe, G. D. O., Peters, S. A. E., Rumley, A., Tunstall-Pedoe, H., & Woodward, M. (2022). Associations of Hemostatic Variables with Cardiovascular Disease and Total Mortality: The Glasgow MONICA Study. TH open : companion journal to thrombosis and haemostasis, 6(2), e107–e113. [CrossRef]

- Ross R. (1986). The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis--an update. The New England journal of medicine, 314(8), 488–500. [CrossRef]

- Krüger-Genge, A., Blocki, A., Franke, R. P., & Jung, F. (2019). Vascular Endothelial Cell Biology: An Update. International journal of molecular sciences, 20(18), 4411. [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, H., Noda, A., Tamura, A., Nagai, M., Okuda, M., Okumura, T., Yasuma, F., & Murohara, T. (2022). Association of sleep-wake rhythm and sleep quality with endothelial function in young adults. Sleep science (Sao Paulo, Brazil), 15(3), 267–271. [CrossRef]

- Holmer, B. J., Lapierre, S. S., Jake-Schoffman, D. E., & Christou, D. D. (2021). Effects of sleep deprivation on endothelial function in adult humans: a systematic review. GeroScience, 43(1), 137–158. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F., Wu, Y., Feng, G., Ni, X., Xu, Z., & Gozal, D. (2018). Polysomnographic correlates of endothelial function in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep medicine, 52, 45–50. [CrossRef]

- Behl, M., Bliwise, D., Veledar, E., Cunningham, L., Vazquez, J., Brigham, K., & Quyyumi, A. (2014). Vascular endothelial function and self-reported sleep. The American journal of the medical sciences, 347(6), 425–428. [CrossRef]

- Wehrens, S. M., Hampton, S. M., & Skene, D. J. (2012). Heart rate variability and endothelial function after sleep deprivation and recovery sleep among male shift and non-shift workers. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health, 38(2), 171–181. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P. D., Friedman, J. C., Ding, S., Miller, R. S., Martin-Gill, C., Hostler, D., & Platt, T. E. (2023). Acute Effect of Night Shift Work on Endothelial Function with and without Naps: A Scoping Review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 20(19), 6864. [CrossRef]

- Nadir, Y., Saharov, G., Hoffman, R., Keren-Politansky, A., Tzoran, I., Brenner, B., & Shochat, T. (2015). Heparanase procoagulant activity, factor Xa, and plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 are increased in shift work female nurses. Annals of hematology, 94(7), 1213–1219. [CrossRef]

- Nadir, Y., Brenner, B., Zetser, A., Ilan, N., Shafat, I., Zcharia, E., Goldshmidt, O., & Vlodavsky, I. (2006). Heparanase induces tissue factor expression in vascular endothelial and cancer cells. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis: JTH, 4(11), 2443–2451. [CrossRef]

- Hayden J, O’Donnell G, deLaunois I, O’Gorman C. Endothelial Peripheral Arterial Tonometry (Endo-PAT 2000) use in paediatric patients: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2023; 13: e062098.

- Hansen AS, Butt JH, Holm-Yildiz S, Karlsson W, Kruuse C. Validation of Repeated Endothelial Function Measurements Using EndoPAT in Stroke. Front Neurol 2017; 8: 178.

- Rajai N, Toya T, Sara JD, Rajotia A, Lopez-Jimenez F, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Prognostic value of peripheral endothelial function on major adverse cardiovascular events above traditional risk factors. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2023; 30: 1781-8.

- Nadir Y, Brenner B, Gingis-Velitski S, et al. Heparanase induces tissue factor pathway inhibitor expression and extracellular accumulation in endothelial and tumor cells. Thromb Haemost 2008; 99: 133-41.

- Nadir, Y., Kenig, Y., Drugan, A., Shafat, I., & Brenner, B. (2011). An assay to evaluate heparanase procoagulant activity. Thrombosis research, 128(4), e3–e8.

- Shafat, I., Zcharia, E., Nisman, B., Nadir, Y., Nakhoul, F., Vlodavsky, I., & Ilan, N. (2006). An ELISA method for the detection and quantification of human heparanase. Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 341(4), 958–963.

- Hill, L. K., Wu, J. Q., Hinderliter, A. L., Blumenthal, J. A., & Sherwood, A. (2021). Actigraphy-Derived Sleep Efficiency Is Associated with Endothelial Function in Men and Women with Untreated Hypertension. American Journal of Hypertension, 34(2), 207–211. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D. C., Ziegler, M. G., Milic, M. S., Ancoli-Israel, S., Mills, P. J., Loredo, J. S., Von Känel, R., & Dimsdale, J. E. (2014). Endothelial function and sleep: associations of flow-mediated dilation with perceived sleep quality and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. Journal of sleep research, 23(1), 84–93. [CrossRef]

- Shah, R., Shah, V. K., Emin, M., Gao, S., Sampogna, R. V., Aggarwal, B., Chang, A., St-Onge, M. P., Malik, V., Wang, J., Wei, Y., & Jelic, S. (2023). Mild sleep restriction increases endothelial oxidative stress in female persons. Scientific reports, 13(1), 15360. [CrossRef]

- Saharov, G., Nadir, Y., Zoran, I., Keren, A., Brenner, B., & Shochat, T. (2013). Hemostatic markers in shift working female nurses. Sleep Medicine, 14(1), e251-e266. [CrossRef]

- Scheer, F. A., & Shea, S. A. (2014). Human circadian system causes a morning peak in prothrombotic plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) independent of the sleep/wake cycle. Blood, 123(4), 590–593. [CrossRef]

- Tofler, G. H., Massaro, J., O’Donnell, C. J., Wilson, P. W. F., Vasan, R. S., Sutherland, P. A., Meigs, J. B., Levy, D., & D’Agostino, R. B., Sr (2016). Plasminogen activator inhibitor and the risk of cardiovascular disease: The Framingham Heart Study. Thrombosis research, 140, 30–35. [CrossRef]

- Wright, K. P., Jr, Drake, A. L., Frey, D. J., Fleshner, M., Desouza, C. A., Gronfier, C., & Czeisler, C. A. (2015). Influence of sleep deprivation and circadian misalignment on cortisol, inflammatory markers, and cytokine balance. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 47, 24–34. [CrossRef]

- Schlagintweit, J., Laharnar, N., Glos, M., Zemann, M., Demin, A. V., Lederer, K., Penzel, T., & Fietze, I. (2023). Effects of sleep fragmentation and partial sleep restriction on heart rate variability during night. Scientific reports, 13(1), 6202. [CrossRef]

- Erem, C., Nuhoglu, I., Yilmaz, M., Kocak, M., Demirel, A., Ucuncu, O., & Onder Ersoz, H. (2009). Blood coagulation and fibrinolysis in patients with Cushing’s syndrome: increased plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, decreased tissue factor pathway inhibitor, and unchanged thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor levels. Journal of endocrinological investigation, 32(2), 169–174. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Cao, Y., Xu, X., Wang, C., Ni, Q., Lv, X., Yang, C., Zhang, Z., Qi, X., & Song, G. (2023). Sleep Deprivation Promotes Endothelial Inflammation and Atherogenesis by Reducing Exosomal miR-182-5p. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology, 43(6), 995–1014. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, K. A., Zheng, H., Kravitz, H. M., Sowers, M., Bromberger, J. T., Buysse, D. J., Owens, J. F., Sanders, M., & Hall, M. (2010). Are inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers related to sleep characteristics in mid-life women? Study of Women’s Health across the Nation sleep study. Sleep, 33(12), 1649–1655. [CrossRef]

- Doddapattar, P., Dhanesha, N., Chorawala, M. R., Tinsman, C., Jain, M., Nayak, M. K., Staber, J. M., & Chauhan, A. K. (2018). Endothelial Cell-Derived Von Willebrand Factor, But Not Platelet-Derived, Promotes Atherosclerosis in Apolipoprotein E-Deficient Mice. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology, 38(3), 520–528. [CrossRef]

- Rumley, A., Lowe, G. D., Sweetnam, P. M., Yarnell, J. W., & Ford, R. P. (1999). Factor VIII, von Willebrand factor and the risk of major ischaemic heart disease in the Caerphilly Heart Study. British journal of haematology, 105(1), 110–116.

- Vischer U. M. (2006). von Willebrand factor, endothelial dysfunction, and cardiovascular disease. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis: JTH, 4(6), 1186–1193. [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, A., Roldán, V., Rivera-Caravaca, J. M., Hernández-Romero, D., Valdés, M., Vicente, V., Lip, G. Y., & Marín, F. (2017). Does von Willebrand factor improve the predictive ability of current risk stratification scores in patients with atrial fibrillation? Scientific reports, 7, 41565. [CrossRef]

- Yiallourou, S. R., & Carrington, M. J. (2021). Improved sleep efficiency is associated with reduced cardio-metabolic risk: Findings from the MODERN trial. Journal of sleep research, 30(6), e13389. [CrossRef]

- Vallat, R., Shah, V. D., Redline, S., Attia, P., & Walker, M. P. (2020). Broken sleep predicts hardened blood vessels. PLoS biology, 18(6), e3000726.

- Münzel, T., Hahad, O., & Daiber, A. (2021). Sleepless in Seattle: Sleep Deprivation and Fragmentation Impair Endothelial Function and Fibrinolysis in Hypertension. Hypertension (Dallas,Tex: 1979), 78(6), 1841-1843. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).