Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

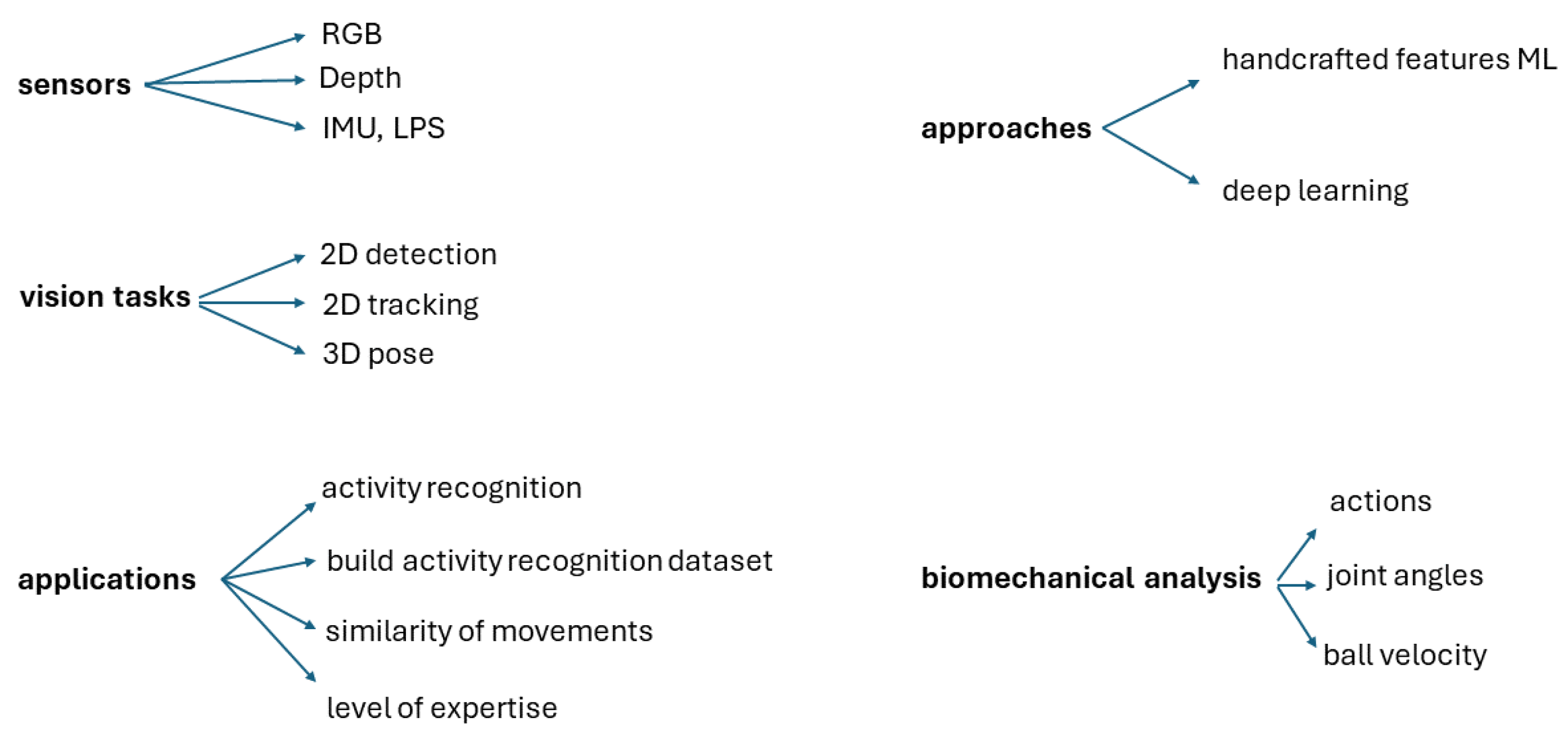

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. H3DD Dataset of Handball Overarm Throws

2.2. Hardware and Software

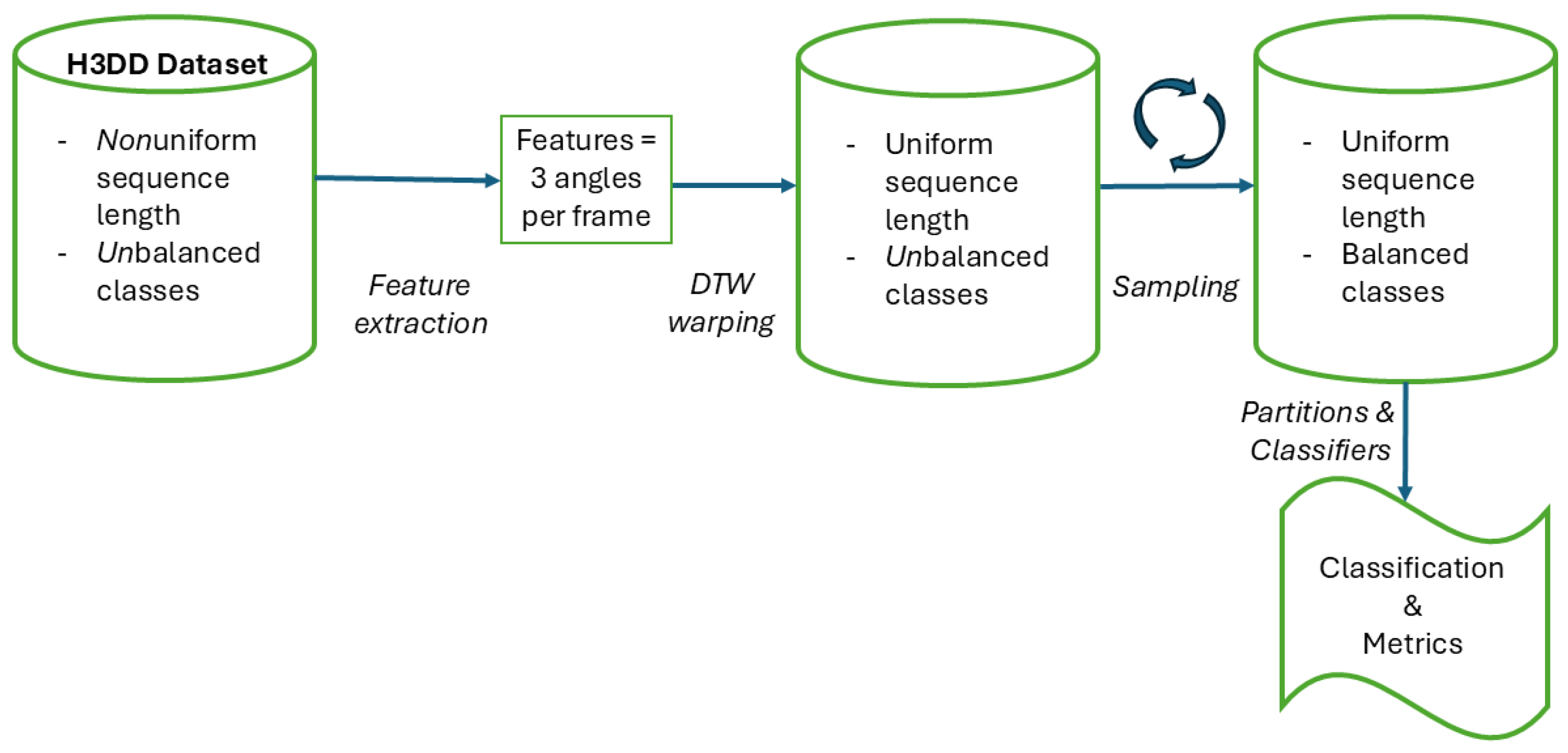

2.3. Method

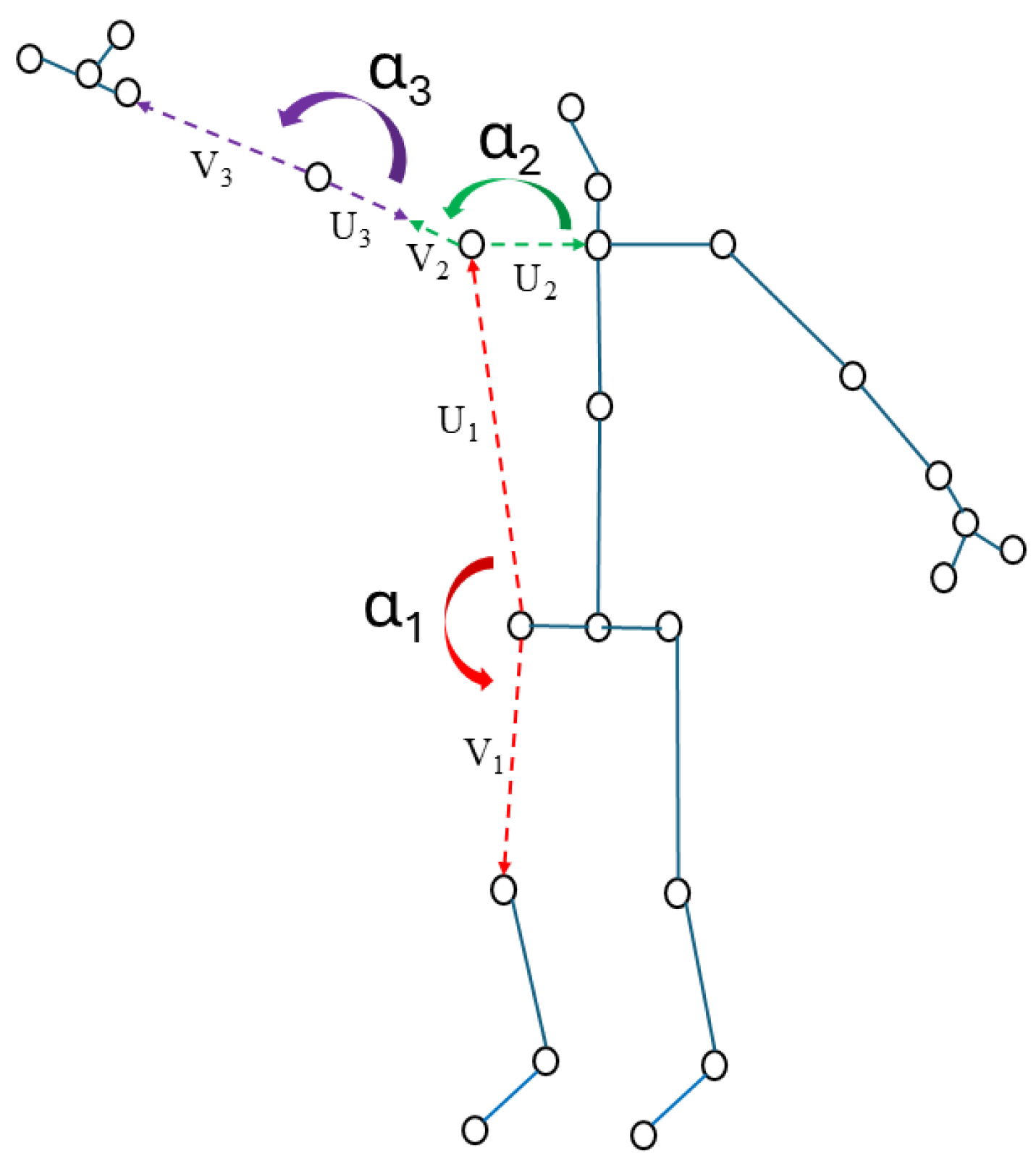

2.4. Features

2.5. Uniform Sequence Length and Alignment

2.6. Balanced Classes

2.7. Classification

3. Experiments and Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ashley, K. Applied machine learning for health and fitness; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, C.M. Pattern recognition and machine learning; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Host, K.; Ivasic-Kos, M. An overview of human action recognition in sports based on computer vision. Heliyon 2022, 8(6), E09633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, J.K.; Ryoo, M.S, Human activity analysis: a review. ACM Computing Surveys 2011, 43 (3) 16 1-43.

- Lo Presti, L.; La Cascia, M. 3D skeleton-based human action classification: A survey. Pattern Recognition 2016, 53 130-147.

- Elaoud, A.; Barhoumi, W.; Zagrouba ,E., et al. Skeleton-based comparison of throwing motion for handball players. J Ambient Intell Human Comput 2020,11 (4) 419-431.

- Van den Tillaar, R.; Bhandurge, S.; Stewart, T. Detection of different throw types and ball velocity with IMUs and machine learning in team handball. In ISBS Proceedings Archive, Liverpool, U.K. 2020.

- Pobar, M.;. Ivasic-Kos, M. Mask R-CNN and Optical Flow Based Method for Detection and Marking of Handball Actions. In 11th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, BioMedical Engineering and Informatics, Beijing, China, 13-15 October 2018.

- Sajina, R.; Ivasic-Kos, M. 3D pose estimation and tracking in handball actions using a monocular camera. J Imaging 2022, 8(11), 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Host, K.; Pobar, M.; Ivasic-Kos, M. Analysis of Movement and Activities of Handball Players Using Deep Neural Networks. J Imaging 2023, 9(4), 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, R. M. L.; Menezes, R. P.; Russomanno, T. G. : et al. Measuring handball players trajectories using an automatically trained boosting algorithm. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin 2010, 14(1), 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Host, K.; Ivasic-Kos,M.; Pobar, M. Tracking Handball Players with the DeepSORT Algorithm. In 9th International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods, Valletta, Malta, 22-24 February 2020.

- Lefevre, T.; Guignard, B.; Karcher, C.; et al. A deep dive into the use of local positioning system in professional handball: Automatic detection of players' orientation, position and game phases to analyze specific physical demands. Plos One 2023, 18(8), e0289752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Tillaar; R.; Ettema G. A three-dimensional analysis of overarm throwing in experienced handball players. Journal of Applied Biomechanics 2007, 23 (1) 12-19.

- Direkoǧlu, C.; O’Connor N.E. Temporal segmentation and recognition of team activities in sports. Machine Vision and Applictions 2018, 29 (3) 891-913.

- Pobar, M.; Ivasic-Kos, M. Active player detection in handball scenes based on activity measures. Sensors 2020, 20 (5) 1475.

- Mathworks. Key Features and Differences in the Kinect V2 Support.

- https://la.mathworks.com/help/imaq/key-features-and-differences-in-the-kinect-v2-support.html (accesed on 10 12 2024).

- Mathworks. DTW. Distance between signals using dynamic time warping.

- https://la.mathworks.com/help/signal/ref/dtw.html?lang=en accesed on 10 12 2024).

- Mathworks. Classification learner App. https://la.mathworks.com/help/stats/classification-learner app.html?lang=en.

- (accesed on 10 12 2024).

- Elaud, A. 2018. H3DD dataset of experts and beginners handball shots. https://github.com/Elaoud/H3DD-dataset.

- Murphy, K.P. 2022. Probabilistic Machine Learning. MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

- Hapkova, I.; Estriga, L.; Rot, C. 2019. Teaching handball, Volume 1: Teacher Guidelines, Handball at School, fun, passion and health. International Handball Federation, Basel, Switzerland.

| Characteristic | Expert | Beginner |

| Right-handed | 14 | 37 |

| Left-handed | 4 | 7 |

| Total | 18 | 44 |

| Frames range | 7 | 6 - 22 |

| Model Number | Model Type | Hyperparameters |

| 1 | Tree | Maximum number of splits: 100; Split criterion: Gini's diversity index; Surrogate decision splits: Off |

| 2 | Tree | Maximum number of splits: 20; Split criterion: Gini's diversity index; Surrogate decision splits: Off |

| 3 | Tree | Maximum number of splits: 4; Split criterion: Gini's diversity index; Surrogate decision splits: Off |

| 4 | Linear Discriminant | Covariance structure: Full |

| 5 | Quadratic Discriminant | Covariance structure: Full |

| 6 | Binary GLM Logistic Regression | None |

| 7 | Efficient Logistic Regression | Learner: Logistic regression; Solver: Auto; Regularization: Auto; Regularization strength (Lambda): Auto; Relative coefficient tolerance (Beta tolerance): 0.0001; Multiclass coding: One-vs-One |

| 8 | Efficient Linear SVM | Learner: SVM; Solver: Auto; Regularization: Auto; Regularization strength (Lambda): Auto; Relative coefficient tolerance (Beta tolerance): 0.0001; Multiclass coding: One-vs-One |

| 9 | Naive Bayes | Distribution name for numeric predictors: Gaussian; Distribution name for categorical predictors: Not Applicable |

| 10 | Naive Bayes | Distribution name for numeric predictors: Kernel; Distribution name for categorical predictors: Not Applicable; Kernel type: Gaussian; Support: Unbounded; Standardize data: Yes |

| 11 | SVM | Kernel function: Linear; Kernel scale: Automatic; Box constraint level: 1; Multiclass coding: One-vs-One; Standardize data: Yes |

| 12 | SVM | Kernel function: Quadratic; Kernel scale: Automatic; Box constraint level: 1; Multiclass coding: One-vs-One; Standardize data: Yes |

| 13 | SVM | Kernel function: Cubic; Kernel scale: Automatic; Box constraint level: 1; Multiclass coding: One-vs-One; Standardize data: Yes |

| 14 | SVM | Kernel function: Gaussian; Kernel scale: 1.1; Box constraint level: 1; Multiclass coding: One-vs-One; Standardize data: Yes |

| 15 | SVM | Kernel function: Gaussian; Kernel scale: 4.6; Box constraint level: 1; Multiclass coding: One-vs-One; Standardize data: Yes |

| 16 | SVM | Kernel function: Gaussian; Kernel scale: 18; Box constraint level: 1; Multiclass coding: One-vs-One; Standardize data: Yes |

| 17 | KNN | Number of neighbors: 1; Distance metric: Euclidean; Distance weight: Equal; Standardize data: Yes |

| 18 | KNN | Number of neighbors: 10; Distance metric: Euclidean; Distance weight: Equal; Standardize data: Yes |

| 19 | KNN | Number of neighbors: 100; Distance metric: Euclidean; Distance weight: Equal; Standardize data: Yes |

| 20 | KNN | Number of neighbors: 10; Distance metric: Cosine; Distance weight: Equal; Standardize data: Yes |

| 21 | KNN | Number of neighbors: 10; Distance metric: Minkowski (cubic); Distance weight: Equal; Standardize data: Yes |

| 22 | KNN | Number of neighbors: 10; Distance metric: Euclidean; Distance weight: Squared inverse; Standardize data: Yes |

| 23 | Ensemble | Ensemble method: AdaBoost; Learner type: Decision tree; Maximum number of splits: 20; Number of learners: 30; Learning rate: 0.1; Number of predictors to sample: Select All |

| 24 | Ensemble | Ensemble method: Bag; Learner type: Decision tree; Maximum number of splits: 25; Number of learners: 30; Number of predictors to sample: Select All |

| 25 | Ensemble | Ensemble method: Subspace; Learner type: Discriminant; Number of learners: 30; Subspace dimension: 11 |

| 26 | Ensemble | Ensemble method: Subspace; Learner type: Nearest neighbors; Number of learners: 30; Subspace dimension: 11 |

| 27 | Ensemble | Ensemble method: RUSBoost; Learner type: Decision tree; Maximum number of splits: 20; Number of learners: 30; Learning rate: 0.1; Number of predictors to sample: Select All |

| 28 | Neural Network | Number of fully connected layers: 1; First layer size: 10; Activation: ReLU; Iteration limit: 1000; Regularization strength (Lambda): 0; Standardize data: Yes |

| 29 | Neural Network | Number of fully connected layers: 1; First layer size: 25; Activation: ReLU; Iteration limit: 1000; Regularization strength (Lambda): 0; Standardize data: Yes |

| 30 | Neural Network | Number of fully connected layers: 1; First layer size: 100; Activation: ReLU; Iteration limit: 1000; Regularization strength (Lambda): 0; Standardize data: Yes |

| 31 | Neural Network | Number of fully connected layers: 2; First layer size: 10; Second layer size: 10; Activation: ReLU; Iteration limit: 1000; Regularization strength (Lambda): 0; Standardize data: Yes |

| 32 | Neural Network | Number of fully connected layers: 3; First layer size: 10; Second layer size: 10; Third layer size: 10; Activation: ReLU; Iteration limit: 1000; Regularization strength (Lambda): 0; Standardize data: Yes |

| 33 | Kernel | Learner: SVM; Number of expansion dimensions: Auto; Regularization strength (Lambda): Auto; Kernel scale: Auto; Multiclass coding: One-vs-One; Standardize data: Yes; Iteration limit: 1000 |

| 34 | Kernel | Learner: Logistic Regression; Number of expansion dimensions: Auto; Regularization strength (Lambda): Auto; Kernel scale: Auto; Multiclass coding: One-vs-One; Standardize data: Yes; Iteration limit: 1000 |

| Train/test rate | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 | TNR |

| 70/30 | 72.85 | 76.66 | 65.71 | 70.76 | 80.00 |

| 80/20 | 76.66 | 85.71 | 70.58 | 77.41 | 84.61 |

| 90/10 | 90.47 | 87.50 | 87.50 | 87.50 | 92.30 |

| Method | Precision | Recall | Accuracy | F1 |

| KNN unbalanced Dataset | 37.71 | 58.67 | 57.44 | 43.33 |

| KNN balanced Dataset | 55.73 | 82.95 | 56.95 | 65.75 |

| Proposed Method | 85.71 | 70.58 | 76.66 | 77.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).