Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

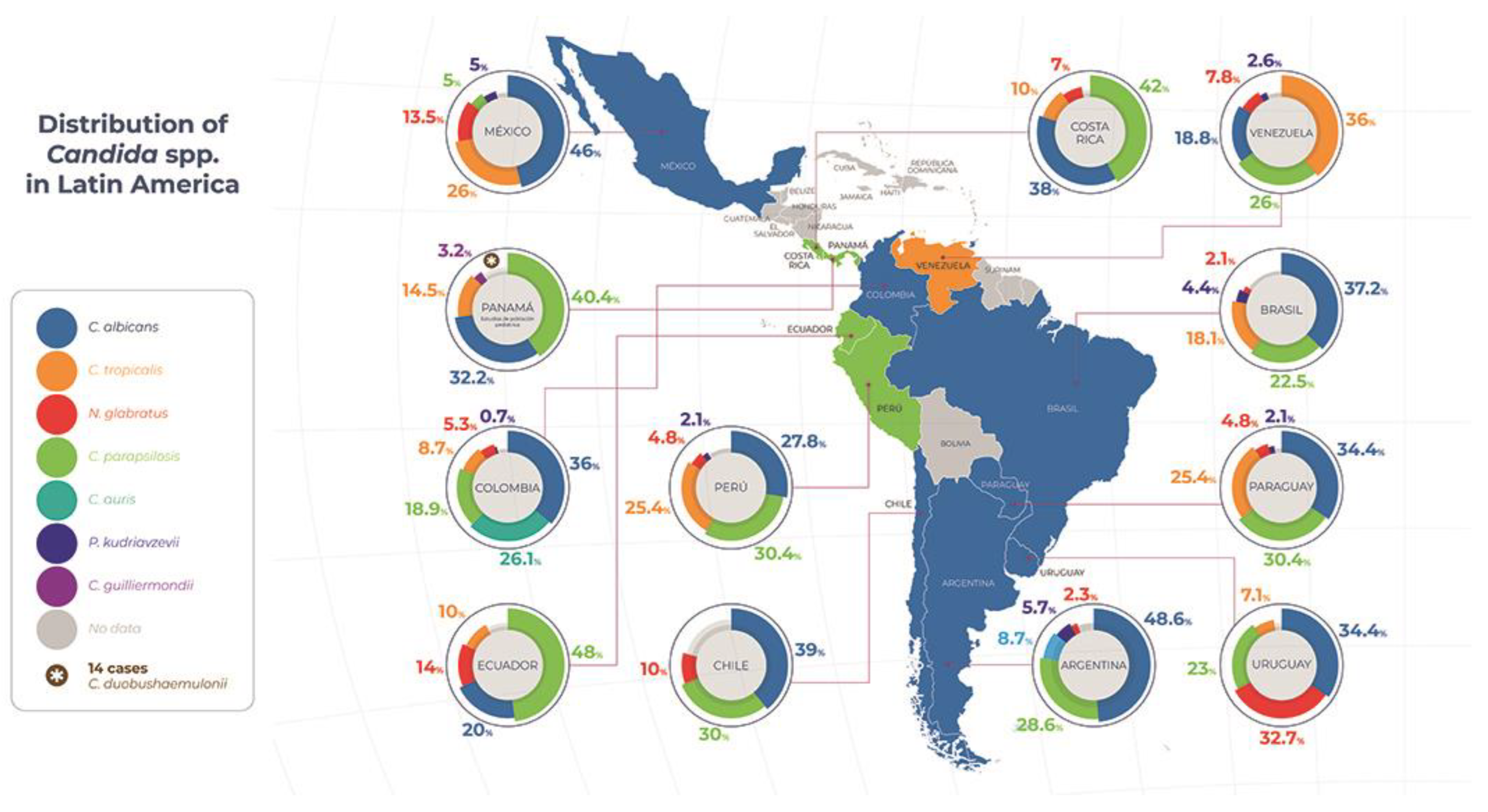

2. Epidemiology of IC in Latin America

3. Risk factors for IC in Latin America

4. Diagnosis of IC in Resource-Limited Settings

Situation in Latin America: Challenges, Barriers, and Obstacles

5. Regional Antifungal Resistance Patterns

- 1.

- Candida parapsilosis

- 2.

- Candida tropicalis

- 3.

- Nakaseomyces glabratus (formerly C. glabrata)

- 4.

- Pichia kudriavzevii (formerly C krusei)

- 5.

- Other emerging yeast-like strains

- •

- Candida haemulonii complex: this yeast is emerging as an invasive pathogen, with reports in several hospitals in the region, including Mexico, Panama, and Brazil. In Brazil, it has been identified in 0.3% of cases, mainly from chronic wounds and blood cultures, and is associated with critically ill patients. It is characterized by a multidrug resistance profile, particularly to AmB and FCZ, and is often misidentified by conventional methods. Therefore, molecular diagnostics or MALDI-TOF are required for accurate identification, as well as active mycological surveillance and timely adjustment of empirical antifungal treatment (91,92).

- •

- Candida duobushaemulonii: this yeast represents an emerging threat in the context of nosocomial infections, with a marked tendency to behave as an invasive, underdiagnosed, and multidrug-resistant pathogen. It should be considered an emerging yeast of relevance in the Latin American hospital setting. The national surveillance of C. auris carried out in Panama between November 2016 and May 2017 evidenced this, and a significant number of cases of invasive infections caused by this strain were unexpectedly identified. Of the 36 suspected isolates sent to the national reference laboratory, 17 (47%) were confirmed as C. duobushaemulonii, affecting 14 patients hospitalized in six health centers in the country (37).

- •

- Meyerozyma guilliermondii complex (formerly Candida guilliermondii): considered an emerging group of opportunistic yeasts, especially in immunocompromised and hospitalized patients. Globally, it accounts for approximately 1% to 5% of candidemia cases, but its importance is increasing due to three main factors: its genetic and taxonomic diversity, an unfavorable antifungal profile, and the difficulties associated with its diagnostic identification. In Latin America, it accounts for up to 7% of candidemia cases in Peru, with the spread of M. caribbica and clade 2 of M. guilliermondii sensu stricto, both associated with azole resistance, being particularly noteworthy. In addition, multiple isolates with resistance to FCZ, AmB, and echinocandins have been documented in Brazil. Given this situation, it is crucial to incorporate molecular identification methods, establish robust antifungal surveillance systems, and adjust empirical antifungal treatment according to the local susceptibility profile. Azole resistance in this complex can vary between 40% and 70%, reinforcing the need for an individualized therapeutic approach (93).

- •

- Candida rugosa: this emerging yeast has gained relevance in the context of invasive infections, particularly in cases of candidemia, due to its worrying resistance profile to azoles. It has established itself as an opportunistic pathogen of growing importance, especially in Latin America, where it has a prevalence approximately seven times higher than in other geographical regions. In Brazil, C. rugosa accounts for up to 2.7% of isolates in ICUs, with FCZ resistance rates reaching 64.9%, and AmB-resistant isolates have also been reported. Its low sensitivity to classic azoles—FCZ (35.7%) and VCZl (55.8%)—makes these antifungals high-risk therapeutic options (94).

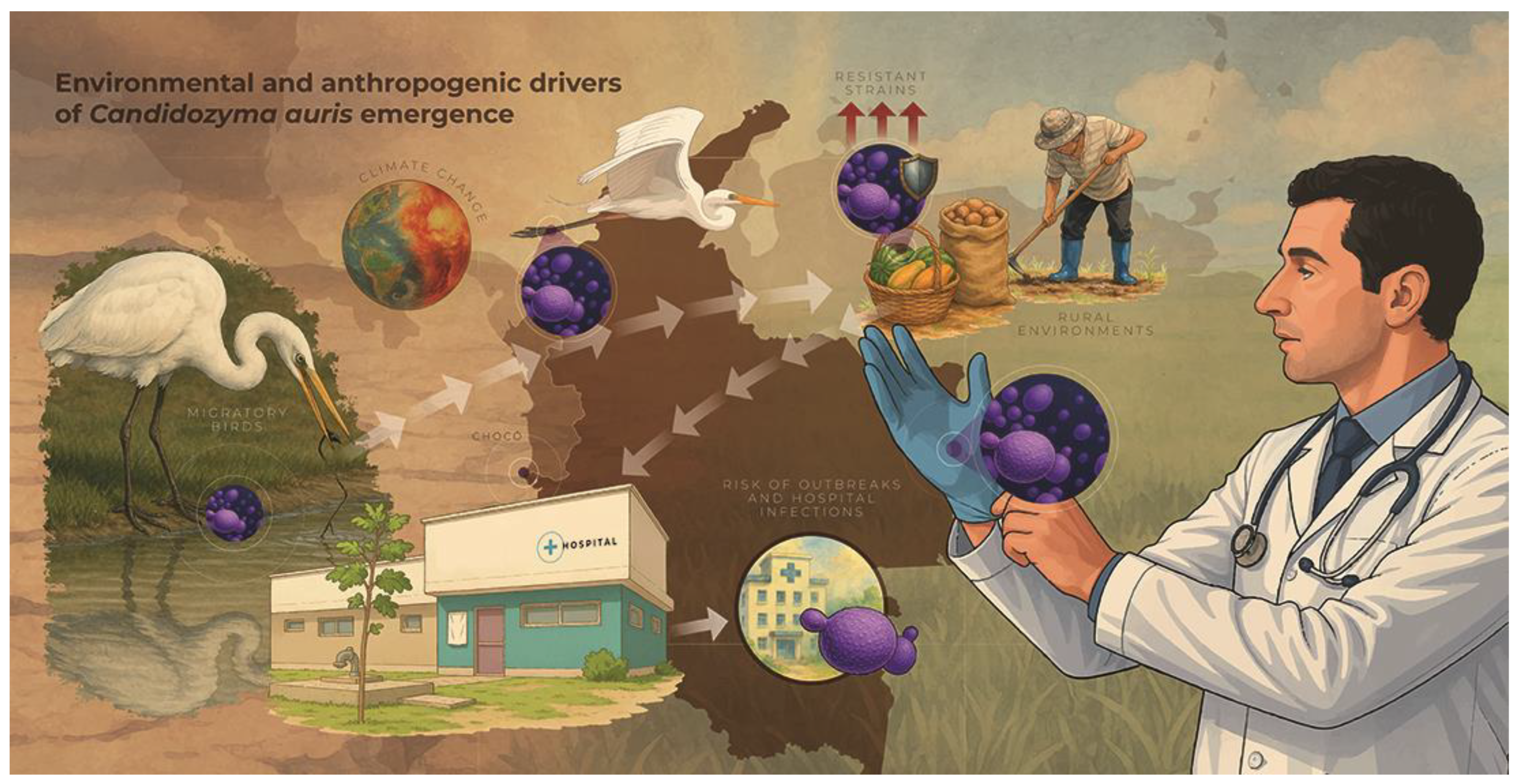

Candidozyma auris (Candida auris) in Latin America

6. Impact of Climate Change on Fungal Infections (Invasive Candidiasis)

7. Access to Health Services and Inequalities in the Region

8. Impact of Housing and Environment on IC in Latin America

Other Invasive Mycoses

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest

References

- Campion EW, Kullberg BJ, Arendrup MC. Invasive Candidiasis. Campion EW, editor. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2025 Apr 29];373(15):1445–56. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26444731/. [CrossRef]

- Pappas PG, Lionakis MS, Arendrup MC, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Kullberg BJ. Invasive candidiasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018 May 11;4. [CrossRef]

- Lass-Flörl C, Kanj SS, Govender NP, Thompson GR, Ostrosky- Zeichner L, Govrins MA. Invasive candidiasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers [Internet]. 2024 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Apr 29];10(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38514673/. [CrossRef]

- Soriano A, Honore PM, Puerta-Alcalde P, Garcia-Vidal C, Pagotto A, Gonçalves-Bradley DC, et al. Invasive candidiasis: current clinical challenges and unmet needs in adult populations. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Apr 29];78:1569–85. [CrossRef]

- Pappas PG, Lionakis MS, Arendrup MC, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Kullberg BJ. Invasive candidiasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers [Internet]. 2018 May 11 [cited 2025 Apr 29];4. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29749387/. [CrossRef]

- Noppè E, Robert J, Eloff P, Keane S, Martin-Loeches I. A Narrative Review of Invasive Candidiasis in the Intensive Care Unit. Therapeutic Advances in Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine [Internet]. 2024 Jan 12 [cited 2025 Apr 29];19:29768675241304684. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11693998/. [CrossRef]

- Koehler P, Stecher M, Cornely OA, Koehler D, Vehreschild MJGT, Bohlius J, et al. Morbidity and mortality of candidaemia in Europe: an epidemiologic meta-analysis. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2019 Oct 1;25(10):1200–12. [CrossRef]

- Seagle EE, Jackson BR, Lockhart SR, Jenkins EN, Revis A, Farley MM, et al. Recurrent Candidemia: Trends and Risk Factors Among Persons Residing in 4 US States, 2011–2018. Open Forum Infect Dis [Internet]. 2022 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Apr 29];9(10):ofac545. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9620433/. [CrossRef]

- Toda M, Williams SR, Berkow EL, Farley MM, Harrison LH, Bonner L, et al. Population-Based Active Surveillance for Culture-Confirmed Candidemia — Four Sites, United States, 2012–2016. MMWR Surveillance Summaries [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Apr 29];68(8):1–17. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31557145/. [CrossRef]

- Ricotta EE, Lai YL, Babiker A, Strich JR, Kadri SS, Lionakis MS, et al. Invasive Candidiasis Species Distribution and Trends, United States, 2009–2017. J Infect Dis [Internet]. 2020 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Apr 29];223(7):1295. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8030726/. [CrossRef]

- Quindós G. Epidemiology of candidaemia and invasive candidiasis. A changing face. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2014 Jan;31(1):42–8. [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Xu YC, Hsueh PR. Epidemiology of candidemia and antifungal susceptibility in invasive Candida species in the Asia-Pacific region. Future Microbiol. 2016 Nov 1;11(11):1461–77. [CrossRef]

- Giacobbe DR, Maraolo AE, Simeon V, Magnè F, Pace MC, Gentile I, et al. Changes in the relative prevalence of candidaemia due to non-albicans Candida species in adult in-patients: A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Mycoses [Internet]. 2020 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Apr 29];63(4):334–42. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31997414/. [CrossRef]

- Murray CJ, Ikuta KS, Sharara F, Swetschinski L, Robles Aguilar G, Gray A, et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet [Internet]. 2022 Feb 12 [cited 2025 Apr 5];399(10325):629–55. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/action/showFullText?pii=S0140673621027240. [CrossRef]

- Frías-De-león MG, Hernández-Castro R, Conde-Cuevas E, García-Coronel IH, Vázquez-Aceituno VA, Soriano-Ursúa MA, et al. Candida glabrata Antifungal Resistance and Virulence Factors, a Perfect Pathogenic Combination. Pharmaceutics [Internet]. 2021 Oct 1 [cited 2025 May 12];13(10):1529. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8538829/. [CrossRef]

- Giacobbe DR, Maraolo AE, Simeon V, Magnè F, Pace MC, Gentile I, et al. Changes in the relative prevalence of candidaemia due to non-albicans Candida species in adult in-patients: A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Mycoses [Internet]. 2020 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Apr 29];63(4):334–42. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31997414/. [CrossRef]

- Nucci M, Queiroz-Telles F, Alvarado-Matute T, Tiraboschi IN, Cortes J, Zurita J, et al. Epidemiology of Candidemia in Latin America: A Laboratory-Based Survey. PLoS One [Internet]. 2013 Mar 19 [cited 2025 Apr 29];8(3):e59373. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0059373. [CrossRef]

- Nucci M, Queiroz-Telles F, Tobón AM, Restrepo A, Colombo AL. Epidemiology of opportunistic fungal infections in latin America. Clinical Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2010 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Apr 29];51(5):561–70. Available from: https://dx.doi.org/10.1086/655683. [CrossRef]

- da Silva RB, Neves RP, Hinrichsen SL, de Lima-Neto RG. Candidemia in a public hospital in Northeastern Brazil: Epidemiological features and risk factors in critically ill patients. Rev Iberoam Micol [Internet]. 2019 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Apr 29];36(4):181–5. Available from: https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-revista-iberoamericana-micologia-290-articulo-candidemia-in-public-hospital-in-S1130140619300567. [CrossRef]

- da Matta DA, Souza ACR, Colombo AL. Revisiting Species Distribution and Antifungal Susceptibility of Candida Bloodstream Isolates from Latin American Medical Centers. Journal of Fungi 2017, Vol 3, Page 24 [Internet]. 2017 May 17 [cited 2025 May 1];3(2):24. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2309-608X/3/2/24/htm. [CrossRef]

- Wille MP, Guimarães T, Campos Furtado GH, Colombo AL. Historical trends in the epidemiology of candidaemia: analysis of an 11-year period in a tertiary care hospital in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2025 Apr 29];108(3):288. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4005563/. [CrossRef]

- Hamburger FG, Gales AC, Colombo AL. Systematic Review of Candidemia in Brazil: Unlocking Historical Trends and Challenges in Conducting Surveys in Middle-Income Countries. Mycopathologia [Internet]. 2024 Aug 1 [cited 2025 May 12];189(4). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38940953/. [CrossRef]

- Cortés JA, Ruiz JF, Melgarejo-Moreno LN, Lemos E V. Candidemia en Colombia. Biomédica [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 May 1];40(1):195. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7357379/. [CrossRef]

- Alexander Salinas Cesar. CARACTERÍSTICAS CLÍNICAS, MICROBIOLÓGICAS Y DESENLACES DE LA CANDIDIASIS INVASORA EN ADULTOS EN UN HOSPITAL DE ALTA COMPLEJIDAD [Internet]. [Bogota]: Universidad del Rosario; 2020 [cited 2025 May 1]. Available from: https://repository.urosario.edu.co/server/api/core/bitstreams/f33a1a7a-13f7-48ac-b4f8-6c2025c7bdc9/content.

- Ortiz-Roa C, Valderrama-Rios MC, Sierra-Umaña SF, Rodríguez JY, Muñetón-López GA, Solórzano-Ramos CA, et al. Mortality Caused by Candida auris Bloodstream Infections in Comparison with Other Candida Species, a Multicentre Retrospective Cohort. Journal of Fungi [Internet]. 2023 Jul 1 [cited 2025 May 12];9(7). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37504704/. [CrossRef]

- Tiraboschi IN, Pozzi NC, Farías L, García S, Fernández NB. Epidemiología, especies, resistencia antifúngica y evolución de las candidemias en un hospital universitario de Buenos Aires, Argentina, durante 16 años. Revista Chilena de Infectologia [Internet]. 2017 Oct 1 [cited 2025 May 1];34(5):431–40. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29488584/. [CrossRef]

- Riera FO, Caeiro JP, Denning DW. Burden of serious fungal infections in Argentina. Journal of Fungi [Internet]. 2018 Jun 1 [cited 2025 May 1];4(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29695056/. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez L, Bustamante B, Huaroto L, Agurto C, Illescas R, Ramirez R, et al. A multi-centric Study of Candida bloodstream infection in Lima-Callao, Peru: Species distribution, antifungal resistance and clinical outcomes. PLoS One [Internet]. 2017 Apr 1 [cited 2025 May 1];12(4):e0175172. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5395148/. [CrossRef]

- Mesa1 LM, Arcaya2 NM, Pineda S3 MR, Luengo3 HB, Calvo4 BM. Candidemia en el Hospital Universitario de Maracaibo, Estado Zulia, Venezuela 2000-2002. Revista de la Sociedad Venezolana de Microbiología [Internet]. 2005 [cited 2025 May 1];25(2):109–13. Available from: http://ve.scielo.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1315-25562005000200010&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es.

- Aguilar G, Araujo P, Lird G, Insaurralde S, Kawabata A, Ayala E, et al. Identificación y perfil de sensibilidad de Candida spp. aisladas de hemocultivos en hospitales de Paraguay. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública [Internet]. 2020 Sep 1 [cited 2025 May 1];44(1):e34. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7498287/. [CrossRef]

- Macedo-Viñas M, Denning DW. Estimating the Burden of Serious Fungal Infections in Uruguay. Journal of Fungi [Internet]. 2018 Mar 1 [cited 2025 May 1];4(1):37. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5872340/. [CrossRef]

- Carbia M, Medina V, Bustillo C, Martínez C, González MP, Ballesté R. Study of Candidemia and its Antifungal Susceptibility Profile at the University Hospital of Montevideo, Uruguay. Mycopathologia [Internet]. 2023 Dec 1 [cited 2025 May 1];188(6):919–28. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37314581/. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Montes M del R, Duarte-Escalante E, Martínez-Herrera E, Acosta-Altamirano G, Frías-De León MG. Current status of the etiology of candidiasis in Mexico. Rev Iberoam Micol [Internet]. 2017 Oct 1 [cited 2025 May 2];34(4):203–10. Available from: https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-revista-iberoamericana-micologia-290-articulo-current-status-etiology-candidiasis-in-S1130140617300864. [CrossRef]

- Corzo-León DE, Perales-Martínez D, Martin-Onraet A, Rivera-Martínez N, Camacho-Ortiz A, Villanueva-Lozano H. Monetary costs and hospital burden associated with the management of invasive fungal infections in Mexico: a multicenter study. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2018 Sep 1 [cited 2025 May 2];22(5):360. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9428020/. [CrossRef]

- Corzo-León DE, Armstrong-James D, Denning DW. Burden of serious fungal infections in Mexico. Mycoses [Internet]. 2015 Oct 1 [cited 2025 May 2];58:34–44. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26449505/. [CrossRef]

- Gousy N, Adithya Sateesh B, Denning DW, Latchman K, Mansoor E, Joseph J, et al. Fungal Infections in the Caribbean: A Review of the Literature to Date. Journal of Fungi [Internet]. 2023 Dec 1 [cited 2025 May 2];9(12). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38132779/. [CrossRef]

- Ramos R, Caceres DH, Perez M, Garcia N, Castillo W, Santiago E, et al. Emerging Multidrug-Resistant Candida duobushaemulonii Infections in Panama Hospitals: Importance of Laboratory Surveillance and Accurate Identification. J Clin Microbiol [Internet]. 2018 Jul 1 [cited 2025 May 12];56(7):e00371-18. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6018349/. [CrossRef]

- la Garza PR de, Cruz-de la Cruz C de la, Bejarano JIC, Romo AEL, Delgado JV, Ramos BA, et al. A multicentric outbreak of Candida auris in Mexico: 2020 to 2023. Am J Infect Control [Internet]. 2024 Dec 1 [cited 2025 May 4];52(12). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39059713/. [CrossRef]

- Gousy N, Adithya Sateesh B, Denning DW, Latchman K, Mansoor E, Joseph J, et al. Fungal Infections in the Caribbean: A Review of the Literature to Date. Journal of Fungi [Internet]. 2023 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Jun 7];9(12). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38132779/. [CrossRef]

- Márquez F, Iturrieta I, Calvo M, Urrutia M, Godoy-Martínez P, Márquez F, et al. Epidemiología y susceptibilidad antifúngica de especies causantes de candidemia en la ciudad de Valdivia, Chile. Revista chilena de infectología [Internet]. 2017 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Jun 11];34(5):441–6. Available from: http://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0716-10182017000500441&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira CS, Colombo AL, Francisco EC, de Lima B, Gandra RF, de Carvalho MCP, et al. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of Candidemia in eight medical centers in the state of Parana, Brazil: Parana Candidemia Network. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2021 Jan 1 [cited 2025 May 8];25(1):101041. Available from: https://www-sciencedirect-com.ez.urosario.edu.co/science/article/pii/S1413867020301689?utm_source=chatgpt.com. [CrossRef]

- de Almeida BL, Agnelli C, Guimarães T, Sukiennik T, Lima PRP, Salles MJC, et al. Candidemia in ICU Patients: What Are the Real Game-Changers for Survival? Journal of Fungi [Internet]. 2025 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Apr 29];11(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39997446/. [CrossRef]

- Motoa G, Muñoz JS, Oñate J, Pallares CJ, Hernández C, Villegas MV. Epidemiology of Candida isolates from Intensive Care Units in Colombia from 2010 to 2013. Rev Iberoam Micol [Internet]. 2016 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Apr 29];34(1):17–22. Available from: https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-revista-iberoamericana-micologia-290-articulo-epidemiology-candida-isolates-from-intensive-S1130140616300286. [CrossRef]

- Ortíz Ruiz G, Osorio J, Valderrama S, Álvarez D, Elías Díaz R, Calderón J, et al. Factores de riesgo asociados a candidemia en pacientes críticos no neutropénicos en Colombia. Med Intensiva [Internet]. 2016 Apr 1 [cited 2025 May 8];40(3):139–44. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26725105/. [CrossRef]

- Riera FO, Caeiro JP, Angiolini SC, Vigezzi C, Rodriguez E, Icely PA, et al. Invasive Candidiasis: Update and Current Challenges in the Management of This Mycosis in South America. Antibiotics [Internet]. 2022 Jul 1 [cited 2025 May 9];11(7). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35884131/. [CrossRef]

- Vazquez JA, Whitaker L, Zubovskaia A. Invasive Candidiasis in the Intensive Care Unit: Where Are We Now? J Fungi (Basel) [Internet]. 2025 Mar 27 [cited 2025 May 9];11(4). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/40278079. [CrossRef]

- Thomas-Rüddel DO, Schlattmann P, Pletz M, Kurzai O, Bloos F. Risk Factors for Invasive Candida Infection in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Chest [Internet]. 2022 Feb 1 [cited 2025 May 9];161(2):345–55. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34673022/. [CrossRef]

- Oñate JM, Rivas P, Pallares C, Saavedra CH, Martínez E, Coronell W, et al. Colombian consensus on the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Candida Spp. disease in children and adults,. Infectio [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 May 8];23(3):271–304. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0123-93922019000300271&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en. [CrossRef]

- Cornely OA, Sprute R, Bassetti M, Chen SCA, Groll AH, Kurzai O, et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of candidiasis: an initiative of the ECMM in cooperation with ISHAM and ASM. Lancet Infect Dis [Internet]. 2025 May [cited 2025 May 8];25(5):e280–93. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39956121/. [CrossRef]

- Riera F, Cortes Luna J, Rabagliatti R, Scapellato P, Caeiro JP, Chaves Magri MM, et al. Antifungal stewardship: the Latin American experience. Antimicrobial Stewardship & Healthcare Epidemiology [Internet]. 2023 Dec 5 [cited 2025 May 8];3(1):e217. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antimicrobial-stewardship-and-healthcare-epidemiology/article/antifungal-stewardship-the-latin-american-experience/E5CB1CC83BF1CC032E1A774F52BEB4FE. [CrossRef]

- Barantsevich N, Barantsevich E. Diagnosis and Treatment of Invasive Candidiasis. Antibiotics [Internet]. 2022 Jun 1 [cited 2025 May 11];11(6):718. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9219674/. [CrossRef]

- Bassetti M, Giacobbe DR, Vena A, Wolff M. Diagnosis and Treatment of Candidemia in the Intensive Care Unit. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;40(4):524–39. [CrossRef]

- Kassim A, Pflüger V, Premji Z, Daubenberger C, Revathi G. Comparison of biomarker based Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) and conventional methods in the identification of clinically relevant bacteria and yeast. BMC Microbiol. 2017 May 25;17(1). [CrossRef]

- Van Veen SQ, Claas ECJ, Kuijper EJ. High-throughput identification of bacteria and yeast by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry in conventional medical microbiology laboratories. J Clin Microbiol [Internet]. 2010 Mar [cited 2025 May 11];48(3):900–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20053859/. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen MH, Wissel MC, Shields RK, Salomoni MA, Hao B, Press EG, et al. Performance of candida real-time polymerase chain reaction, β-D-glucan assay, and blood cultures in the diagnosis of invasive candidiasis. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2012 May 1;54(9):1240–8. [CrossRef]

- Cortés JA, Valderrama-Rios MC, Peçanha-Pietrobom PM, Júnior MS, Diaz-Brochero C, Robles-Torres RR, et al. Evidence-based clinical standard for the diagnosis and treatment of candidemia in critically ill patients in the intensive care unit. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 May 11];29(1):104495. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11846572/. [CrossRef]

- Avni T, Leibovici L, Paul M. PCR diagnosis of invasive candidiasis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Microbiol [Internet]. 2011 Feb [cited 2025 May 11];49(2):665–70. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21106797/. [CrossRef]

- Nieto M, Robles JC, Causse M, Gutiérrez L, Cruz Perez M, Ferrer R, et al. Polymerase Chain Reaction Versus Blood Culture to Detect Candida Species in High-Risk Patients with Suspected Invasive Candidiasis: The MICAFEM Study. Infect Dis Ther [Internet]. 2019 Sep 1 [cited 2025 May 11];8(3):429–44. Available from: https://link-springer-com.ez.urosario.edu.co/article/10.1007/s40121-019-0248-z. [CrossRef]

- Tang DL, Chen X, Zhu CG, Li ZW, Xia Y, Guo XG. Pooled analysis of T2 Candida for rapid diagnosis of candidiasis. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2019 Sep 11 [cited 2025 May 11];19(1):1–8. Available from: https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-019-4419-z. [CrossRef]

- Monday LM, Acosta TP, Alangaden G. T2Candida for the Diagnosis and Management of Invasive Candida Infections. Journal of Fungi 2021, Vol 7, Page 178 [Internet]. 2021 Mar 3 [cited 2025 May 11];7(3):178. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2309-608X/7/3/178/htm. [CrossRef]

- Mallick DC, Kaushik N, Goyal L, Mallick L, Singh P. A Comprehensive Review of Candidemia and Invasive Candidiasis in Adults: Focus on the Emerging Multidrug-Resistant Fungus Candida auris. Diseases [Internet]. 2025 Mar 24 [cited 2025 May 9];13(4). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/40277804. [CrossRef]

- Sexton DJ, Bentz ML, Welsh RM, Litvintseva AP. Evaluation of a new T2 Magnetic Resonance assay for rapid detection of emergent fungal pathogen Candida auris on clinical skin swab samples. Mycoses [Internet]. 2018 Oct 1 [cited 2025 May 11];61(10):786–90. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29938838/. [CrossRef]

- Sexton DJ, Bentz ML, Welsh RM, Litvintseva AP. Evaluation of a new T2 Magnetic Resonance assay for rapid detection of emergent fungal pathogen Candida auris on clinical skin swab samples. Mycoses [Internet]. 2018 Oct 1 [cited 2025 May 11];61(10):786–90. Available from: /doi/pdf/10.1111/myc.12817. [CrossRef]

- Mikulska M, Calandra T, Sanguinetti M, Poulain D, Viscoli C. The use of mannan antigen and anti-mannan antibodies in the diagnosis of invasive candidiasis: recommendations from the Third European Conference on Infections in Leukemia. Crit Care [Internet]. 2010 Dec 8 [cited 2025 May 11];14(6):R222. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3219989/. [CrossRef]

- Falci DR, Pasqualotto AC. Clinical mycology in Latin America and the Caribbean: A snapshot of diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities. Mycoses [Internet]. 2019 Apr 1 [cited 2025 May 11];62(4):368–73. Available from: /doi/pdf/10.1111/myc.12890. [CrossRef]

- Riera F, Caeiro JP, Cornely OA, Salmanton-García J, Reyes NDA, Morales A, et al. The Argentinian landscape of mycological diagnostic capacity and treatment accessibility. Med Mycol [Internet]. 2023 Jun 5 [cited 2025 May 11];61(6):58. Available from: https://dx-doi-org.ez.urosario.edu.co/10.1093/mmy/myad058. [CrossRef]

- Cortés JA, Reyes P, Gómez CH, Cuervo SI, Rivas P, Casas CA, et al. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics and risk factors for mortality in patients with candidemia in hospitals from Bogotá, Colombia. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2025 May 1];18(6):631–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25181401/. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Moreno CA, Cortes JA, Denning DW. Burden of fungal infections in Colombia. Journal of Fungi [Internet]. 2018 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Jun 11];4(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29561795/. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Bustos V, Cabanero-Navalon MD, Ruiz-Saurí A, Ruiz-Gaitán AC, Salavert M, Tormo M, et al. What do we know about candida auris? State of the art, knowledge gaps, and future directions. Microorganisms [Internet]. 2021 Oct 1 [cited 2025 May 8];9(10). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34683498/. [CrossRef]

- Escandón P, Cáceres DH, Lizarazo D, Lockhart SR, Lyman M, Duarte C. Laboratory-based surveillance of Candida auris in Colombia, 2016–2020. Mycoses. 2022 Feb 1;65(2):222–5. [CrossRef]

- Escandón P, Lockhart SR, Chow NA, Chiller TM. Candida auris: a global pathogen that has taken root in Colombia. Biomédica [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 May 4];43(Suppl 1):278. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10599714/. [CrossRef]

- Escandón P, Lockhart SR, Chow NA, Chiller TM. Candida auris: a global pathogen that has taken root in Colombia. Biomédica [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Apr 29];43(Suppl 1):278. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10599714/. [CrossRef]

- Escandón P, Chow NA, Caceres DH, Gade L, Berkow EL, Armstrong P, et al. Molecular Epidemiology of Candida auris in Colombia Reveals a Highly Related, Countrywide Colonization With Regional Patterns in Amphotericin B Resistance. Clinical Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2019 Jan 1 [cited 2025 May 5];68(1):15–21. Available from: https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy411. [CrossRef]

- Lanna M, Lovatto J, de Almeida JN, Medeiros EA, Colombo AL, García-Effron G. Epidemiological and Microbiological aspects of Candidozyma auris (Candida auris) in Latin America: A literature review. Journal of Medical Mycology [Internet]. 2025 Jun 1 [cited 2025 May 4];35(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40215876/. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Parada I, Agudelo-Quintero E, Prado-Molina DG, Serna-Trejos JS. Current situation of Candida auris in Colombia, 2021. Anales de la Facultad de Medicina. 2021;82(3):242–3. [CrossRef]

- Zuluaga Rodríguez A, de Bedout Gómez C, Agudelo Restrepo CA, Hurtado Parra H, Arango Arteaga M, Restrepo Moreno Á, et al. Sensibilidad a fluconazol y voriconazol de especies de Candida aisladas de pacientes provenientes de unidades de cuidados intensivos en Medellín, Colombia (2001–2007). Rev Iberoam Micol [Internet]. 2010 Jul 1 [cited 2025 May 1];27(3):125–9. Available from: https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-revista-iberoamericana-micologia-290-articulo-sensibilidad-fluconazol-voriconazol-especies-candida-S1130140610000616. [CrossRef]

- Colombo AL, Cortes JA, Zurita J, Guzman-Blanco M, Alvarado Matute T, de Queiroz Telles F, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis of candidemia in Latin America. Rev Iberoam Micol [Internet]. 2013 Jul 1 [cited 2025 May 11];30(3):150–7. Available from: https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-revista-iberoamericana-micologia-290-articulo-recommendations-for-diagnosis-candidemia-in-S1130140613000533. [CrossRef]

- Govrins M, Lass-Flörl C. Candida parapsilosis complex in the clinical setting. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2023 22:1 [Internet]. 2023 Sep 6 [cited 2025 May 12];22(1):46–59. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41579-023-00961-8. [CrossRef]

- Govender NP, Patel J, Magobo RE, Naicker S, Wadula J, Whitelaw A, et al. Emergence of azole-resistant Candida parapsilosis causing bloodstream infection: Results from laboratory-based sentinel surveillance in South Africa. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy [Internet]. 2016 Jul 1 [cited 2025 May 12];71(7):1994–2004. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27125552/. [CrossRef]

- Corzo-Leon DE, Peacock M, Rodriguez-Zulueta P, Salazar-Tamayo GJ, MacCallum DM. General hospital outbreak of invasive candidiasis due to azole-resistant Candida parapsilosis associated with an Erg11 Y132F mutation. Med Mycol [Internet]. 2021 Jul 1 [cited 2025 May 12];59(7):664–71. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33305313/. [CrossRef]

- Ceballos-Garzon A, Peñuela A, Valderrama-Beltrán S, Vargas-Casanova Y, Ariza B, Parra-Giraldo CM. Emergence and circulation of azole-resistant C. albicans, C. auris and C. parapsilosis bloodstream isolates carrying Y132F, K143R or T220L Erg11p substitutions in Colombia. Front Cell Infect Microbiol [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 May 12];13. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37026059/. [CrossRef]

- Franconi I, Rizzato C, Poma N, Tavanti A, Lupetti A. Candida parapsilosis sensu stricto Antifungal Resistance Mechanisms and Associated Epidemiology. Journal of Fungi [Internet]. 2023 Aug 1 [cited 2025 May 12];9(8):798. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10456088/. [CrossRef]

- Ning Y, Xiao M, Perlin DS, Zhao Y, Lu M, Li Y, et al. Decreased echinocandin susceptibility in Candida parapsilosis causing candidemia and emergence of a pan-echinocandin resistant case in China. Emerg Microbes Infect [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 May 12];12(1). Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/22221751.2022.2153086. [CrossRef]

- Daneshnia F, de Almeida Júnior JN, Ilkit M, Lombardi L, Perry AM, Gao M, et al. Worldwide emergence of fluconazole-resistant Candida parapsilosis: current framework and future research roadmap. Lancet Microbe [Internet]. 2023 Jun 1 [cited 2025 May 12];4(6):e470–80. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37121240/. [CrossRef]

- Favarello LM, Nucci M, Queiroz-Telles F, Guimarães T, Salles MJ, Sukiennik TCT, et al. Trends towards lower azole susceptibility among 200 Candida tropicalis bloodstream isolates from Brazilian medical centres. J Glob Antimicrob Resist [Internet]. 2021 Jun 1 [cited 2025 May 12];25:199–201. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33812048/. [CrossRef]

- Spruijtenburg B, Baqueiro CCSZ, Colombo AL, Meijer EFJ, de Almeida JN, Berrio I, et al. Short Tandem Repeat Genotyping and Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Latin American Candida tropicalis Isolates. Journal of Fungi [Internet]. 2023 Feb 1 [cited 2025 May 12];9(2):207. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2309-608X/9/2/207/htm. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Herrera E, Frías-De-león MG, Hernández-Castro R, García-Salazar E, Arenas R, Ocharan-Hernández E, et al. Antifungal Resistance in Clinical Isolates of Candida glabrata in Ibero-America. Journal of Fungi 2022, Vol 8, Page 14 [Internet]. 2021 Dec 26 [cited 2025 May 12];8(1):14. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2309-608X/8/1/14/htm. [CrossRef]

- Colombo AL, Garnica M, Aranha Camargo LF, Da Cunha CA, Bandeira AC, Borghi D, et al. Candida glabrata: An emerging pathogen in Brazilian tertiary care hospitals. Med Mycol [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2025 Jun 17];51(1):38–44. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22762208/. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen TA, Kim HY, Stocker S, Kidd S, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Dao A, et al. Pichia kudriavzevii (Candida krusei): A systematic review to inform the World Health Organisation priority list of fungal pathogens. Med Mycol [Internet]. 2024 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Jun 17];62(6). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38935911/. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen TA, Kim HY, Stocker S, Kidd S, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Dao A, et al. Pichia kudriavzevii (Candida krusei): A systematic review to inform the World Health Organisation priority list of fungal pathogens. Med Mycol [Internet]. 2024 Jun 1 [cited 2025 May 12];62(6):myad132. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11210618/. [CrossRef]

- Françoiseid U, Desnos-Ollivier M, Govic Y Le, Sitbon K, Valentino R, Peugny S, et al. Candida haemulonii complex, an emerging threat from tropical regions? PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2023 Jul 1 [cited 2025 May 12];17(7):e0011453. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10437918/. [CrossRef]

- de Almeida JN, Assy JGPL, Levin AS, del Negro GMB, Giudice MC, Tringoni MP, et al. Candida haemulonii Complex Species, Brazil, January 2010–March 2015 - Volume 22, Number 3—March 2016 - Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2016 Mar 1 [cited 2025 May 12];22(3):561–3. Available from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/22/3/15-1610_article. [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi R, Lotfali E, Rezaei K, Madinehzad SA, Tafti MF, Aliabadi N, et al. Meyerozyma guilliermondii species complex: review of current epidemiology, antifungal resistance, and mechanisms. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology [Internet]. 2022 Dec 1 [cited 2025 May 12];53(4):1761. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9679122/. [CrossRef]

- Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Colombo AL, Kibbler C, Ng KP, Gibbs DL, et al. Candida rugosa, an Emerging Fungal Pathogen with Resistance to Azoles: Geographic and Temporal Trends from the ARTEMIS DISK Antifungal Surveillance Program. J Clin Microbiol [Internet]. 2006 Oct 1 [cited 2025 May 12];44(10):3578. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1594768/. [CrossRef]

- Misas E, Escandón PL, Gade L, Caceres DH, Hurst S, Le N, et al. Genomic epidemiology and antifungal-resistant characterization of Candida auris , Colombia, 2016–2021 . mSphere [Internet]. 2024 Feb 28 [cited 2025 May 5];9(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38299868/. [CrossRef]

- Chow NA, Muñoz JF, Gade L, Berkow EL, Li X, Welsh RM, et al. Tracing the evolutionary history and global expansion of candida auris using population genomic analyses. mBio [Internet]. 2020 Mar 1 [cited 2025 May 5];11(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32345637/. [CrossRef]

- Sabino R, Veríssimo C, Pereira ÁA, Antunes F. Candida auris, an agent of hospital-associated outbreaks: Which challenging issues do we need to have in mind? Microorganisms [Internet]. 2020 Feb 1 [cited 2025 May 8];8(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32012865/. [CrossRef]

- Casadevall A, Kontoyiannis DP, Robert V. On the emergence of candida auris: climate change, azoles, swamps, and birds. mBio. 2019;10(4). [CrossRef]

- Escandón P. Novel Environmental Niches for Candida auris: Isolation from a Coastal Habitat in Colombia. Journal of Fungi 2022, Vol 8, Page 748 [Internet]. 2022 Jul 19 [cited 2025 May 4];8(7):748. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2309-608X/8/7/748/htm. [CrossRef]

- Lanna M, Lovatto J, de Almeida JN, Medeiros EA, Colombo AL, García-Effron G. Epidemiological and Microbiological aspects of Candidozyma auris (Candida auris) in Latin America: A literature review. Journal of Medical Mycology [Internet]. 2025 Jun 1 [cited 2025 May 1];35(2):101546. Available from: https://www-sciencedirect-com.ez.urosario.edu.co/science/article/pii/S1156523325000150?utm_source=chatgpt.com. [CrossRef]

- Du H, Bing J, Hu T, Ennis CL, Nobile CJ, Huang G. Candida auris: Epidemiology, biology, antifungal resistance, and virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2020 Oct 22;16(10). [CrossRef]

- Frías-De-León MG, García-Salazar E, Reyes-Montes M del R, Duarte-Escalante E, Acosta-Altamirano G. Opportunistic Yeast Infections and Climate Change: The Emergence of Candida auris. 2022 [cited 2025 May 8];161–79. Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-89664-5_10. [CrossRef]

- Patricia Escandón, Carolina Duarte, Sandra Rivera. Alerta por emergencia global de infecciones invasivas causadas por la levadura multirresistente, Candida auris [Internet]. Bogota; [cited 2025 Jun 15]. Available from: https://www.ins.gov.co/buscador-eventos/Informacin%20de%20laboratorio/Alerta-por%20emergencia-Candida%20auris-Colombia.pdf.

- Clara-Noguera M, Orozco S, Lizarazo D, Escandón P, Clara-Noguera M, Orozco S, et al. Prevalencia de Candida auris en departamentos de Colombia durante la vigilancia por el laboratorio (2018-2021). Infectio [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 15];28(4):241–5. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0123-93922024000400241&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=es. [CrossRef]

- Naz S, Fatima Z, Iqbal P, Khan A, Zakir I, Ullah H, et al. An introduction to climate change phenomenon. Building Climate Resilience in Agriculture: Theory, Practice and Future Perspective. 2021 Oct 21;3–16.

- Jaramillo A, Mendoza-Ponce A. Climate Change Overview. 2022 [cited 2025 May 8];1–18. Available from: https://link-springer-com.ez.urosario.edu.co/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-89664-5_1.

- Sedik S, Egger M, Hoenigl M. Climate Change and Medical Mycology. Infect Dis Clin North Am [Internet]. 2024 Mar 1 [cited 2025 May 8];39(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39701899/. [CrossRef]

- Van Rhijn N, Bromley M. The consequences of our changing environment on life threatening and debilitating fungal diseases in humans. Journal of Fungi [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 May 8];7(5). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34067211/. [CrossRef]

- Seidel D, Wurster S, Jenks JD, Sati H, Gangneux JP, Egger M, et al. Impact of climate change and natural disasters on fungal infections. Lancet Microbe [Internet]. 2024 Jun 1 [cited 2025 May 8];5(6):e594–605. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/action/showFullText?pii=S2666524724000399. [CrossRef]

- Sharma C, Kadosh D. Perspective on the origin, resistance, and spread of the emerging human fungal pathogen Candida auris. PLoS Pathog [Internet]. 2023 Mar 1 [cited 2025 May 8];19(3 March). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36952448/. [CrossRef]

- Misseri G, Ippolito M, Cortegiani A. Global warming “heating up” the ICU through Candida auris infections: The climate changes theory. Crit Care. 2019 Dec 19;23(1). [CrossRef]

- Van Rhijn N, Bromley M. The consequences of our changing environment on life threatening and debilitating fungal diseases in humans. Journal of Fungi. 2021;7(5). [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Bustos V, Cabanero-Navalon MD, Ruiz-Saurí A, Ruiz-Gaitán AC, Salavert M, Tormo M, et al. What do we know about candida auris? State of the art, knowledge gaps, and future directions. Microorganisms [Internet]. 2021 Oct 1 [cited 2025 May 5];9(10). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34683498/. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Bustos V, Cabañero-Navalon MD, Ruiz-Gaitán A, Salavert M, Tormo-Mas MÁ, Pemán J. Climate change, animals, and Candida auris: insights into the ecological niche of a new species from a One Health approach. Clinical Microbiology and Infection [Internet]. 2023 Jul 1 [cited 2025 May 8];29(7):858–62. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36934871/. [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Hamm P, Torres-Cruz TJ. The Impact of Climate Change on Human Fungal Pathogen Distribution and Disease Incidence. Curr Clin Microbiol Rep [Internet]. 2024 Sep 1 [cited 2025 May 8];11(3):140–52. Available from: https://link-springer-com.ez.urosario.edu.co/article/10.1007/s40588-024-00224-x. [CrossRef]

- George ME, Gaitor TT, Cluck DB, Henao-Martínez AF, Sells NR, Chastain DB. The impact of climate change on the epidemiology of fungal infections: implications for diagnosis, treatment, and public health strategies. Ther Adv Infect Dis [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 May 8];12:20499361251313840. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11815821/. [CrossRef]

- Seidel D, Wurster S, Jenks JD, Sati H, Gangneux JP, Egger M, et al. Impact of climate change and natural disasters on fungal infections. Lancet Microbe [Internet]. 2024 Jun 1 [cited 2025 May 8];5(6):e594–605. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38518791/. [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti A, Sood P. On the emergence, spread and resistance of Candida auris: Host, pathogen and environmental tipping points. J Med Microbiol [Internet]. 2021 Feb 18 [cited 2025 May 8];70(3). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33599604/. [CrossRef]

- Casadevall A, Kontoyiannis DP, Robert V. On the emergence of candida auris: climate change, azoles, swamps, and birds. mBio [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 May 8];10(4). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31337723/. [CrossRef]

- Colombo AL, Garnica M, Aranha Camargo LF, Da Cunha CA, Bandeira AC, Borghi D, et al. Candida glabrata: An emerging pathogen in Brazilian tertiary care hospitals. Med Mycol [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2025 May 8];51(1):38–44. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22762208/. [CrossRef]

- Kneale M, Bartholomew JS, Davies E, Denning DW. Global access to antifungal therapy and its variable cost. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy [Internet]. 2016 Dec 1 [cited 2025 May 8];71(12):3599–606. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27516477/. [CrossRef]

- Valladales-Restrepo LF, Ospina-Cano JA, Aristizábal-Carmona BS, López-Caicedo DF, Toro-Londoño M, Gaviria-Mendoza A, et al. Study of Prescription-Indication of Outpatient Systemic Anti-Fungals in a Colombian Population. A Cross-Sectional Study. Antibiotics [Internet]. 2022 Dec 1 [cited 2025 May 8];11(12):1805. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9774786/. [CrossRef]

- Van Zyl C, Badenhorst M, Hanekom S, Heine M. Unravelling ‘low-resource settings’: a systematic scoping review with qualitative content analysis. BMJ Glob Health [Internet]. 2021 Jun 3 [cited 2025 May 8];6(6):5190. Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/content/6/6/e005190. [CrossRef]

- Laks M, Guerra CM, Miraglia JL, Medeiros EA. Distance learning in antimicrobial stewardship: innovation in medical education. BMC Med Educ [Internet]. 2019 Jun 7 [cited 2025 May 8];19(1):191. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6555969/. [CrossRef]

- Barteit S, Guzek D, Jahn A, Bärnighausen T, Jorge MM, Neuhann F. Evaluation of e-learning for medical education in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Comput Educ [Internet]. 2020 Feb 1 [cited 2025 May 8];145:103726. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7291921/. [CrossRef]

- Otero P, Hersh W, Luna D, González Bernaldo De Quirós F. A medical informatics distance-learning course for Latin America: Translation, implementation and evaluation. Methods Inf Med. 2010;49(3):310–5. [CrossRef]

- GAFFI y OPS unen fuerzas para combatir las infecciones causadas por hongos en América Latina y el Caribe - OPS/OMS | Organización Panamericana de la Salud [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 8]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/es/noticias/14-5-2024-gaffi-ops-unen-fuerzas-para-combatir-infecciones-causadas-por-hongos-america.

- De Fátima Dos Santos A, Alves HJ, Nogueira JT, Torres RM, Do Carmo Barros Melo M. Telehealth distance education course in latin America: Analysis of an experience involving 15 countries. Telemedicine and e-Health [Internet]. 2014 Aug 1 [cited 2025 May 8];20(8):736–41. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24901742/. [CrossRef]

- Jenks JD, Aneke CI, Al-Obaidi MM, Egger M, Garcia L, Gaines T, et al. Race and ethnicity: Risk factors for fungal infections? PLoS Pathog. 2023 Jan 1;19(1). [CrossRef]

- Jenks JD, Prattes J, Wurster S, Sprute R, Seidel D, Oliverio M, et al. Social determinants of health as drivers of fungal disease. EClinicalMedicine [Internet]. 2023 Dec 1 [cited 2025 May 12];66:102325. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10694587/. [CrossRef]

- Karen del Carmen Morales-Ramírez RASSCPFAFEDERMP. Environmental and Social Determinants Related to Candidiasi. In: Payam Behzadi, editor. Candida albicans - Epidemiology and Treatment [Internet]. Iran: IntechOpen; 2024 [cited 2025 May 12]. p. 1–122. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/1180029. [CrossRef]

- Graham H, White PCL. Social determinants and lifestyles: integrating environmental and public health perspectives. Public Health [Internet]. 2016 Dec 1 [cited 2025 May 12];141:270–8. Available from: https://www-sciencedirect-com.ez.urosario.edu.co/science/article/pii/S0033350616302505. [CrossRef]

- Brito-Santos F, Barbosa GG, Trilles L, Nishikawa MM, Wanke B, Meyer W, et al. Environmental Isolation of Cryptococcus gattii VGII from Indoor Dust from Typical Wooden Houses in the Deep Amazonas of the Rio Negro Basin. PLoS One [Internet]. 2015 Feb 17 [cited 2025 May 12];10(2):e0115866. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0115866. [CrossRef]

| Diagnostic method | Main advantages | Main limitations | Availability in Latin America |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood culture | - Reference standard: isolation, identification, and susceptibility testing | - Prolonged duration (3–4 days) - Moderate sensitivity (21%–71%) |

Widely available in most hospitals |

| 1,3-β-D-glucan (serum) | - High sensitivity for invasive candidiasis (92%) - Useful for ruling out systemic infection |

- Low specificity (positive in other mycoses) - High cost |

Absent in most centers |

| Mannan/Antimannan (serum) | - Allows detection of circulating Candida antigens | - Reduced sensitivity (55%–60%) - Interlaboratory variability |

Very scarce: infrequent clinical use |

| Quantitative PCR (in blood) | - Results in a few hours - Sensitivity 92%; specificity 95% | - Requires reference laboratory and highly trained personnel | Only 20% of centers in Argentina |

| T2Candida (magnetic resonance imaging) | - Direct and rapid detection (3–5 hours) - Sensitivity 91%; specificity 99% |

- Very high cost - Only five specific strains |

Almost unavailable; very limited data |

| MALDI-TOF MS | - Identification of strains in minutes from the culture | - Expensive equipment - Requires previous cultivation |

Available in 20–50% of high-volume laboratories |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).