Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

10 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Methodology

2.2. Design Results

3. Discussion

4. Conclusion

References

- Zhou, M., Sun, C., Naghavi, S. A., Wang, L., Tamaddon, M., Wang, J., & Liu, C. (2024, February). The design and manufacturing of a Patient-Specific wrist splint for rehabilitation of rheumatoid arthritis. Materials & Design, 238, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Srikanth, S. A., & Bharanidaran, R. (2017, June). Design of a compliant mechanism based prosthetic foot. International Journal of Mechanical and Production, 7(3), 33-42.

- Steck, P., Scherb, D., Witzgall, C., Miehling, J., & Wartzack, S. (2023, May 2). Design and Additive Manufacturing of a Passive Ankle–Foot Orthosis Incorporating Material Characterization for Fiber-Reinforced PETG-CF15. Additive Manufacturing of Composites, Volume II, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Rajput, S., Burde, H., Singh, U. S., Kajaria, H., & Bhagchandani, R. K. (2021). Optimization of prosthetic leg using generative design and compliant mechanism. 3rd International Conference on Materials, Manufacturing and Modelling, 46(17), 8708-8715. [CrossRef]

- Yan, W., Ding, M., Kong, B., Xi, X., & Zhou, M. (2019, July 13). Lightweight Splint Design for Individualized Treatment of Distal Radius Fracture. Journal of Medical Systems, 43, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Cazon, A., Kelly, S., Paterson, A. M., Bibb, R. J., & Campbell, R. I. (2017, July 8). Analysis and comparison of wrist splint designs using the finite element method: Multi-material three-dimensional printing compared to typical existing practice with thermoplastics. Journal of Engineering in Medicine, 231(9). [CrossRef]

- Singer, J. C., & Lamontagne, M. (2008, January). The effect of functional knee brace design and hinge misalignment on lower limb joint mechanics. Clinical Biomechanics, 23(1), 52-59. [CrossRef]

- Robert Lachaine, X., Dessery, Y., Belzile, É. L., & Corbeil, P. (2022, July). Knee braces and foot orthoses multimodal treatment of medial knee osteoarthritis. Gait & Posture, 96, 251-256. [CrossRef]

- Briard, T., Segonds, F., & Zamariola, N. (2020, August 3). G-DfAM: a methodological proposal of generative design for additive manufacturing in the automotive industry. International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing (IJIDeM), 14, 875-886. [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.-E., Seo, K.-J., Ha, S., & Kim, H. (2023). Effects of community ambulation training with 3D-printed ankle–foot orthosis on gait and functional improvements: a case series of three stroke survivors. Frontiers in Neurology, 14, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Oka, T., Wada, O., Asai, T., Maruno, H., & Mizuno, K. (2020). Importance of knee flexion range of motion during the acute phase after total knee arthroplasty. Physical Therapy Research, 23(2), 143-148. [CrossRef]

- Farah, S., Anderson, D. G., & Langer, R. (2016, December 15). Physical and mechanical properties of PLA, and their functions in widespread applications — A comprehensive review. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 107, 367-392. [CrossRef]

- Vukasovic, T., Vivanco, J. F., Celentano, D., & García-Herrera, C. (2019, August 8). Characterization of the mechanical response of thermoplastic parts fabricated with 3D printing. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 104, 4207-4218. [CrossRef]

- Kok, C.L.; Dai, Y.; Lee, T.K.; Koh, Y.Y.; Teo, T.H.; Chai, J.P. A Novel Low-Cost Capacitance Sensor Solution for Real-Time Bubble Monitoring in Medical Infusion Devices. Electronics 2024, 13, 1111. [CrossRef]

- García-Ávila, J.; Rodríguez, C.A.; Vargas-Martínez, A.; Ramírez-Cedillo, E.; Martínez-López, J.I. E-Skin Development and Prototyping via Soft Tooling and Composites with Silicone Rubber and Carbon Nanotubes. Materials 2021, 15, 256.

- Klute, G. K., C. F. Kallfelz, and J. M. Czerniecki, Mechanical properties of prosthetic limbs: adapting to the patient. J Rehabil Res Dev, 2001. 38(3): p. 299-307.

- Fey, N. P., A. K. Silverman, and R. R. Neptune, The influence of increasing steady-state walking speed on muscle activity in below-knee amputees. J Electromyogr Kinesiol, 2009.

- Rogati, G.; Caravaggi, P.; Leardini, A. Design principles, manufacturing, and evaluation techniques of custom dynamic ankle-foot orthoses: A review study. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2022, 15, 38.

- Rossetos, I.; Gantes, C.J.; Kazakis, G.; Voulgaris, S.; Galanis, D.; Pliarchopoulou, F.; Soultanis, K.; Lagaros,N.D. Numerical Modeling and Nonlinear Finite Element Analysis of Conventional and 3D-Printed SpinalBraces. Applied Sciences 2024,14, 1735. Number: 5 Publisher: Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. [CrossRef]

- Witzgall, C.; Völkl, H.; Wartzack, S. Derivation and Validation of Linear Elastic Orthotropic Material Properties for Short Fibre Reinforced FLM Parts. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 101.

- R. Bharanidaran and S. A. Srikanth, “A new method for designing a compliant mechanism-based displacement amplifier,” in IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 2016, vol. 149, no.1.

- C. L. Kok, T. H. Teo, Y. Y. Koh, Y. Dai, B. K. Ang and J. P. Chai, “Development and Evaluation of an IoT-Driven Auto-Infusion System with Advanced Monitoring and Alarm Functionalities,” 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Singapore, Singapore, 2024, pp. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liang, J.; Xu, N.; Zeng, L.; Du, C.; Du, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Yu, M.; Liu, Z. 3D-printed brace in the treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a study protocol of a prospective randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2020,10, e038373. Publisher: British Medical Journal Publishing Group Section: Surgery. [CrossRef]

- Redaelli, D.F.; Abbate, V.; Storm, F.A.; Ronca, A.; Sorrentino, A.; De Capitani, C.; Biffi, E.; Ambrosio, L.;Colombo, G.; Fraschini, P. 3D printing orthopedic scoliosis braces: a test comparing FDM with thermoforming. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2020,111, 1707–1720.

- Frangedaki, E.; Sardone, L.; Marano, G.C.; Lagaros, N.D. Optimisation-driven design in the architectural, engineering and construction industry. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Structures and Buildings2023,176, 998–1009, [https://doi.org/10.1680/jstbu.22.00032]. [CrossRef]

- Scherb, D.; Steck, P.; Wartzack, S.; Miehling, J. Integration of musculoskeletal and model order reduced FE simulation for passive ankle foot orthosis design. In Proceedings of the 27th Congress of the European Society of Biomechanics, Porto, Portugal, 26–29 June 2022.

- Mayer, J.; Wartzack, S. Computational Geometry Reconstruction from 3D Topology Optimization Results: A New Parametric Approach by the Medial Axis. Comput. Des. Appl. 2023, 20, 960–975.

- Andreassen, E.; Clausen, A.; Schevenels, M.; Lazarov, B.; Sigmund, O. Efficient topology optimization in MATLAB using 88 lines of code. Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization 2011,43, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xiaojian, et al. “Topological design and additive manufacturing of porous metals for bone scaffolds and orthopedic implants: a review.” Biomaterials 83 (2016): 127-141.

- Kok, C.L.; Tan, T.C.; Koh, Y.Y.; Lee, T.K.; Chai, J.P. Design and Testing of an Intramedullary Nail Implant Enhanced with Active Feedback and Wireless Connectivity for Precise Limb Lengthening. Electronics 2024, 13, 1519.

- Agache PG, Monneur C, Leveque JL, Rigal JD (1980) Mechanical proper-ties and young’s modulus of human skin in vivo. Archives of Dermatological Research 269(3):221–232. [CrossRef]

- Wohlers, T., Campbell, R. I., Huff, R., Diegel, O., & Kowen, J.: Wohlers report 2019: 3D printing and additive manufacturing state of the industry. Wohlers Associates (2019).

- Chew KTL, Lew HL, Date E, Fredericson M (2007) Current evidence and clinical applications of therapeutic knee braces. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation 86(8):678–686. [CrossRef]

- Bethke K (2005) The second skin approach: skin strain field analysis and mechanical counter pressure prototyping for advanced spacesuit design. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Diridollou S, Black D, Lagarde J, Gall Y, Berson M, Vabre V, Patat F, VaillantL (2000) Sex- and site-dependent variations in the thickness and mechanical properties of human skin in vivo. International Journal of Cosmetic Science22(6):421–435. [CrossRef]

- Kok, C.L.; Ho, C.K.; Teo, T.H.; Kato, K.; Koh, Y.Y. A Novel Implementation of a Social Robot for Sustainable Human Engagement in Homecare Services for Ageing Populations. Sensors 2024, 24, 4466. [CrossRef]

- Kuo, T.C., Huang, S.H., Zhang, H.C.: Design for manufacture and design for ‘X’: concepts, applications, and perspectives. Comput. Ind. Eng. 41(3), 241–260 (2001).

- Laverne, F., Segonds, F., Anwer, N., etal.: Assembly based methods to support product innovation in design for additive manufacturing: an exploratory case study. J. Mech. Des. 137, 121701 (2015).

- Molimard J, Navarro L (2013) Uncertainty on fringe projection technique: a Monte-Carlo-based approach. Optics and Laser in Engineering 51(7):840–847.

- Guo, X., Zhang, W., Zhang, J., etal.: Explicit structural topology optimization based on moving morphable components (MMC) with curved skeletons. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 310, 711–748 (2016).

- Deckers JP, Vermandel M, Geldhof J, Vasiliauskaite E, Forward M, PlasschaertF. Development and clinical evaluation of laser-sintered ankle foot orthoses. Plastics Rubber Composites. (2018) 47:42–6. [CrossRef]

- J. Kong, L. Siek and C. L. Kok, “A 9-bit body-biased vernier ring time-to-digital converter in 65 nm CMOS technology,” 2015 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Lisbon, Portugal, 2015, pp. 1650-1653. [CrossRef]

- Wimmer MA, Nechtow W, et al.: Knee flexion and daily activities in patients following total knee replacement: a comparison with ISO standard 14243. Biomed Res Int. 2015 Aug 11. [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen HS, Nakayama H, R aaschou HO, Olsen TS. Recovery of walking function in stroke patients: the Copenhagen Stroke Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (1995) 76:27–32. [CrossRef]

- Silva SM, Corrêa JCF, Pereira GS, Corrêa FI. Social participation following a stroke: an assessment in accordance with the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Disabil Rehabil. (2019) 41:879–86. [CrossRef]

- Ebert JR, Munsie C, et al.: Guidelines for the early restoration of active knee flexion after total knee arthroplasty: implications for rehabilitation and early intervention. Arch Phys Med Rehabil.2014; 95: 1135-1140.

- Jakobsen TL, Christensen M, et al.: Reliability of knee joint range of motion and circumference measurements after total knee arthroplasty: does tester experience matter? Physiother ResInt. 2010; 15: 126-134.

- Hesse S, Werner C, Matthias K, Stephen K, Berteanu M. Non–velocity-related effects of a rigid double-stopped ankle-foot orthosis on gait and lower limb muscle activity of hemiparetic subjects with an equinovarus deformity. Stroke. (1999) 30:1855–61. [CrossRef]

- Bangor A, Kortum PT, Miller JT. An empirical evaluation of the system usability scale. Intl J Hum Comp Int. (2008) 24:574–94. [CrossRef]

- Gatha NM, Clarke HD, et al.: Factors affecting postoperative range of motion after total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. 2004;17: 196-202.

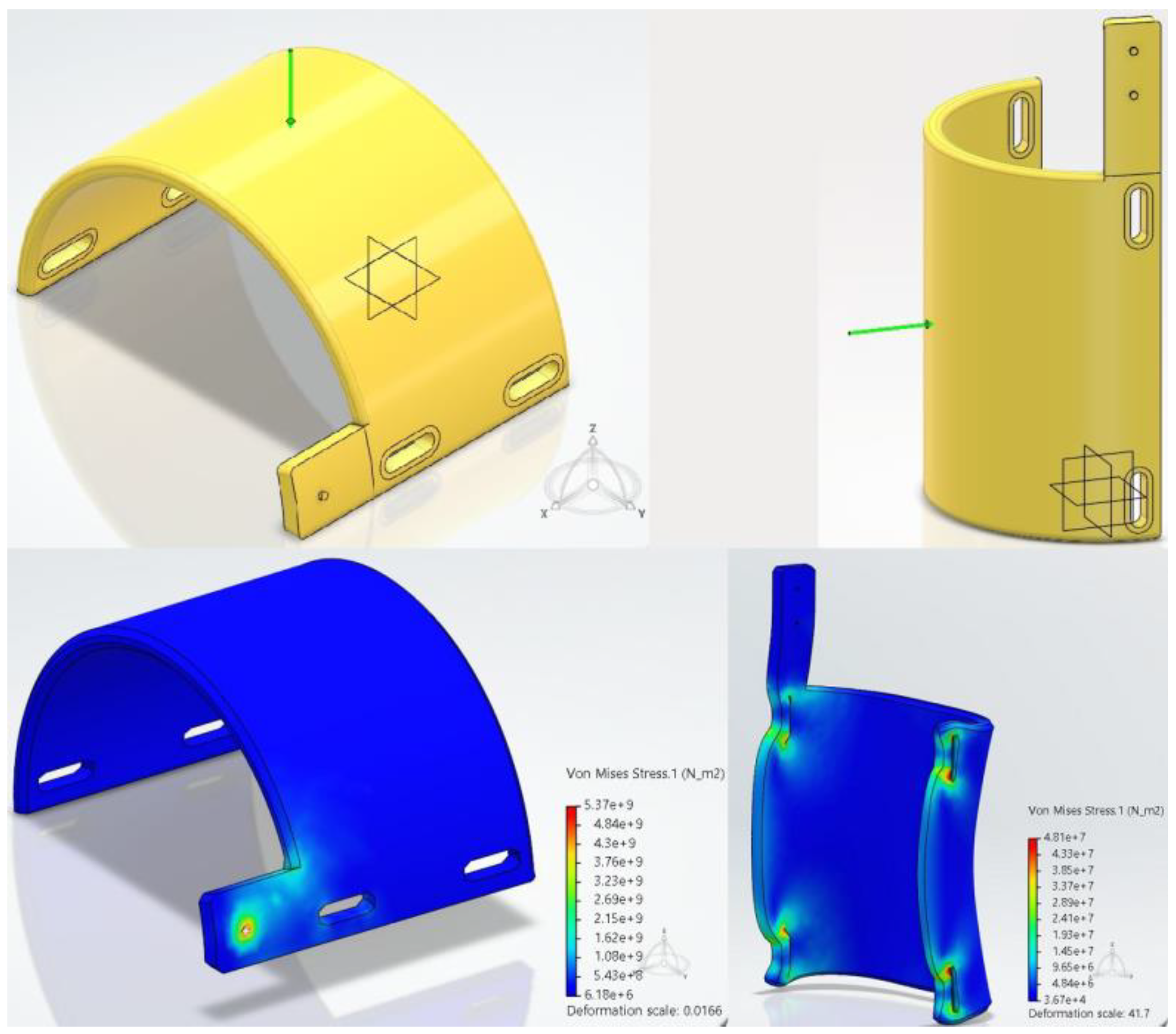

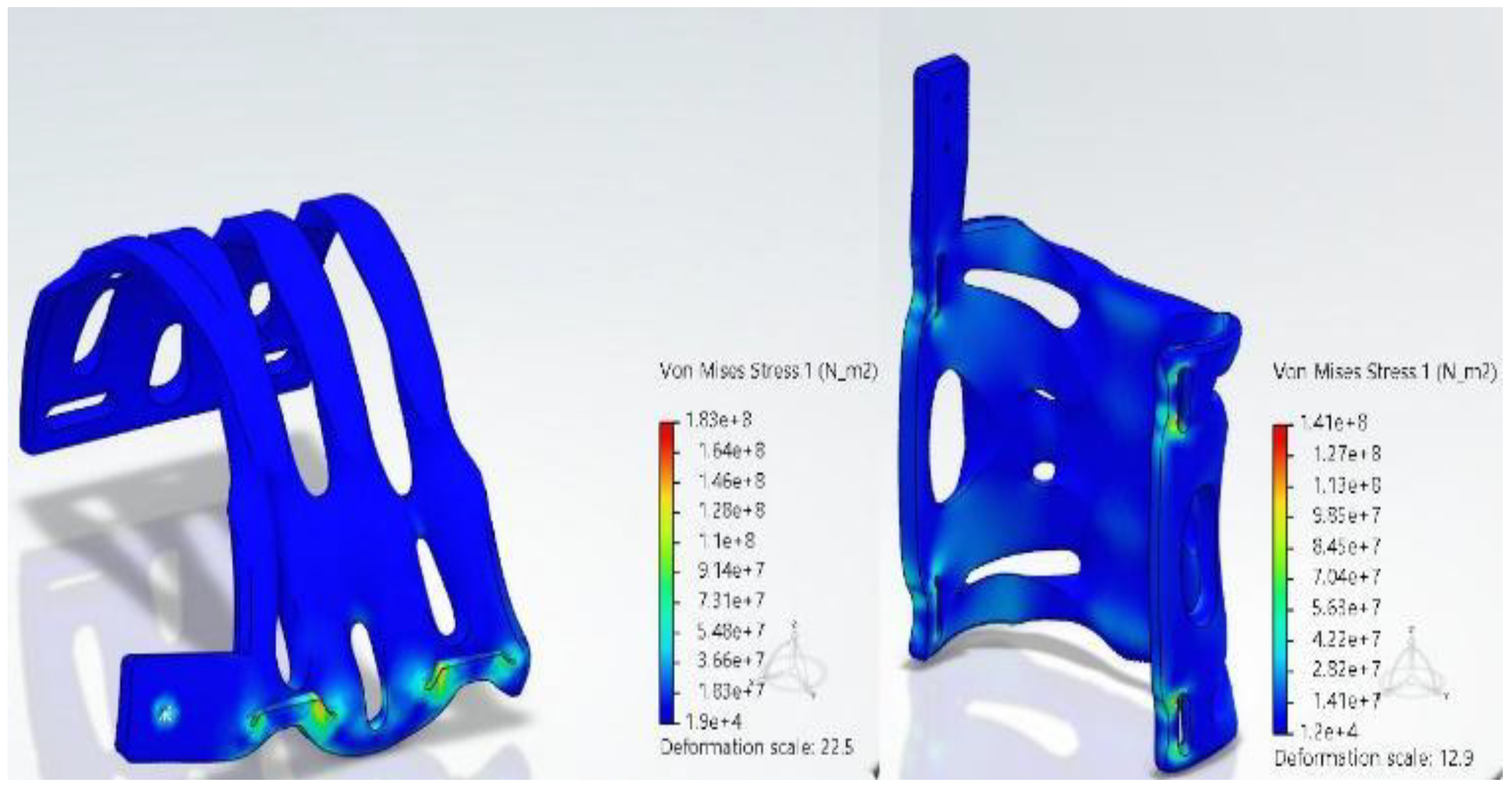

| Braces and Mass Constraints | Mass (kg) | Von Mises Stress (Nm2) | Displacement (mm) | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thigh, 100% | 0.131 | 5.37 × 109 | 0.94 | — |

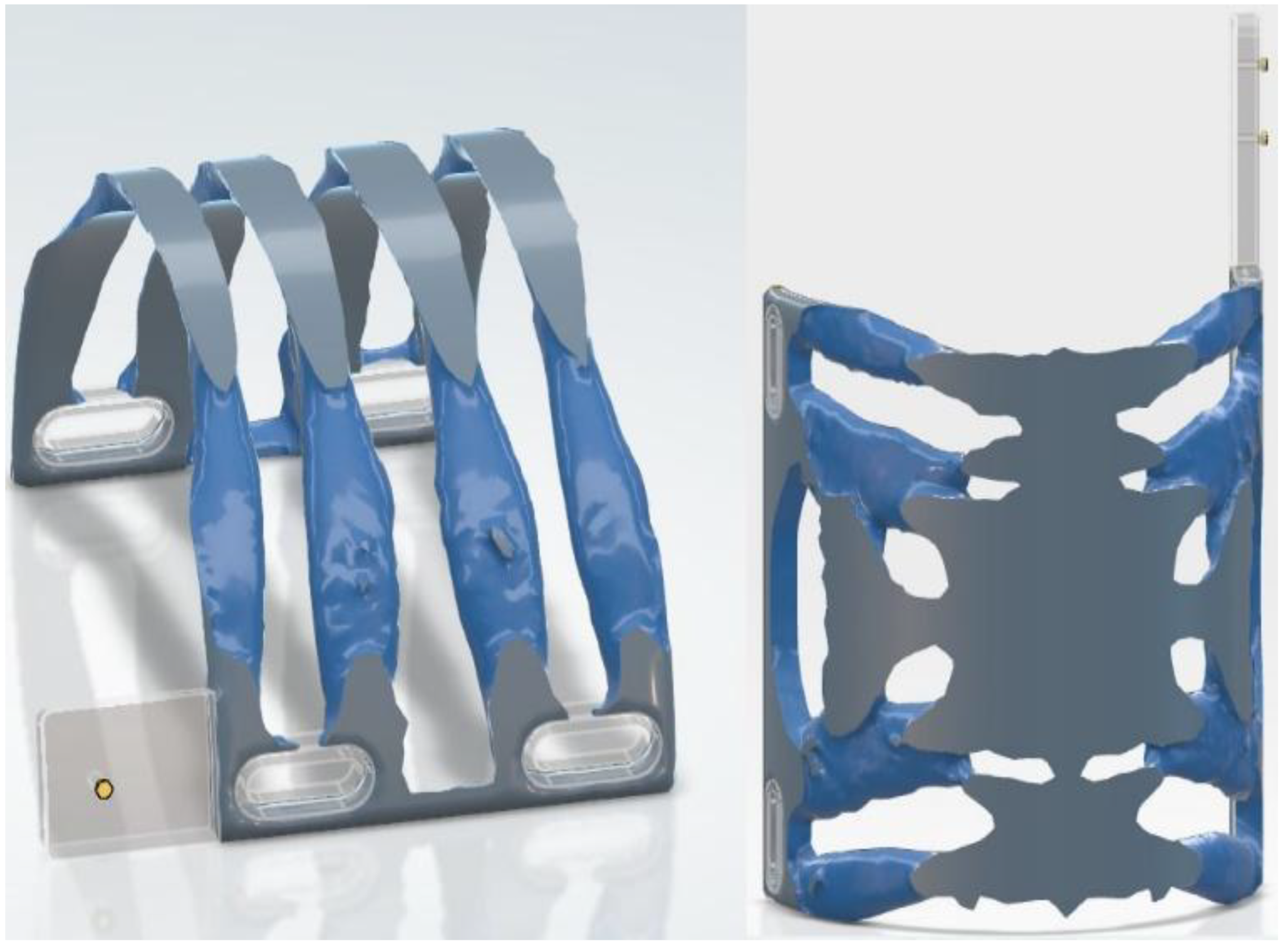

| Thigh, 50% | 0.080 | 1.87 × 108 | 0.84 | 60.87 |

| Thigh, 45% | 0.071 | 1.98 × 108 | 1.22 | 65.87 |

| Thigh, 40% | 0.062 | 2.45 × 108 | 2.99 | 43.91 |

| Shin, 100% | 0.199 | 4.81 × 107 | 0.46 | — |

| Shin, 50% | 0.137 | 1.41 × 108 | 1.48 | 57.31 |

| Shin, 45% | 0.122 | 1.58 × 108 | 1.83 | 54.38 |

| Shin, 40% | 0.109 | 1.83 × 108 | 2.16 | 39.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).