Submitted:

08 July 2025

Posted:

09 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- An online traffic obfuscation experimental network is established, which is an operational network link between smart home devices and their external router that enables real-time capture and dynamic obfuscation of traffic patterns (including packet size and timing characteristics) while maintaining normal device operation.

- The implemented platform supports three fundamental obfuscation primitives: fake traffic injection, packet padding, and packet segmentation, and provides an extensible architecture for integrating and evaluating novel complex obfuscation methods through continuous online validation.

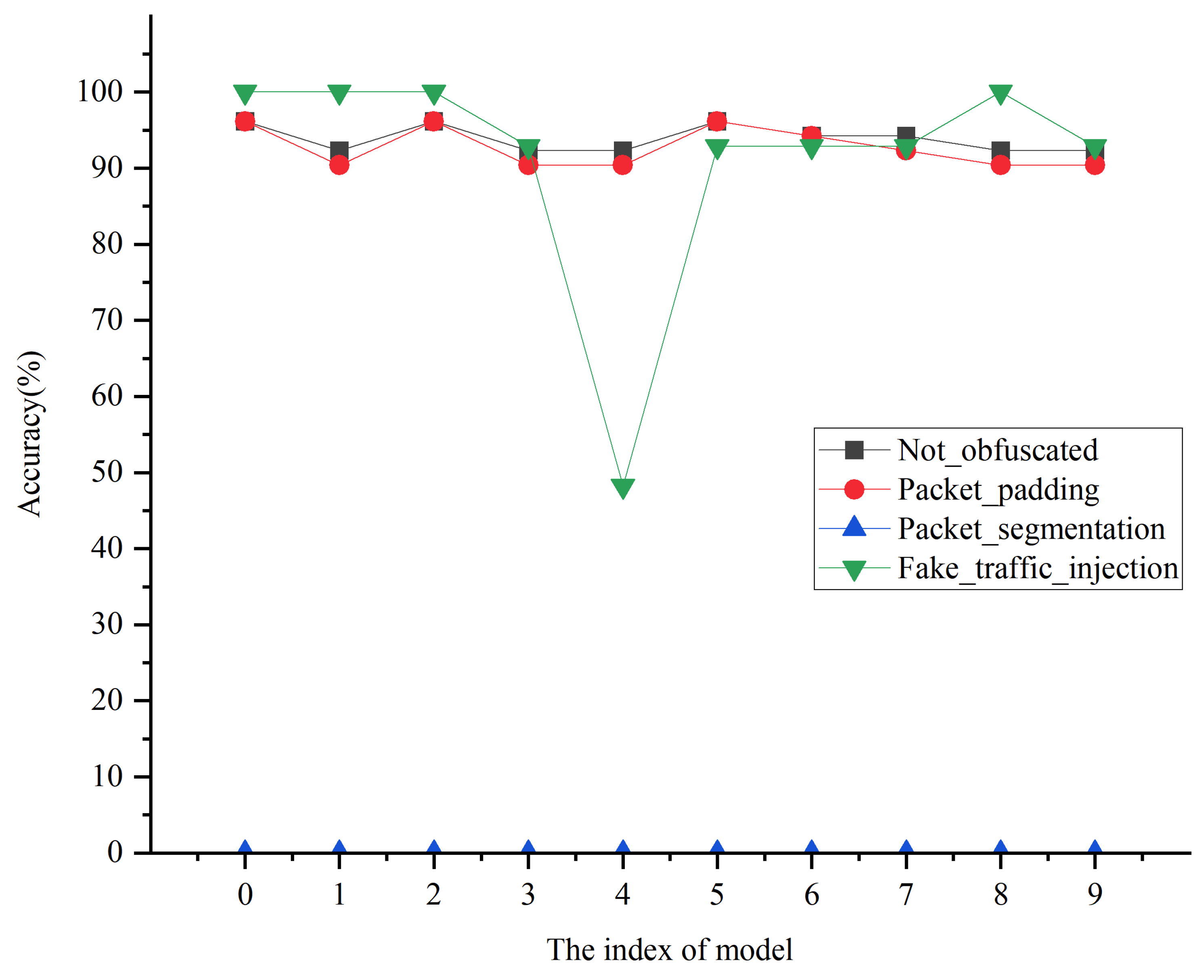

- Our evaluation confirms the framework’s ability to preserve device connectivity and functional integrity during obfuscation. While the basic techniques demonstrate partial effectiveness against traffic analysis (consistent with existing literature), the results highlight the need for developing advanced composite methods building upon these foundational approaches to achieve stronger protection.

2. Related Work

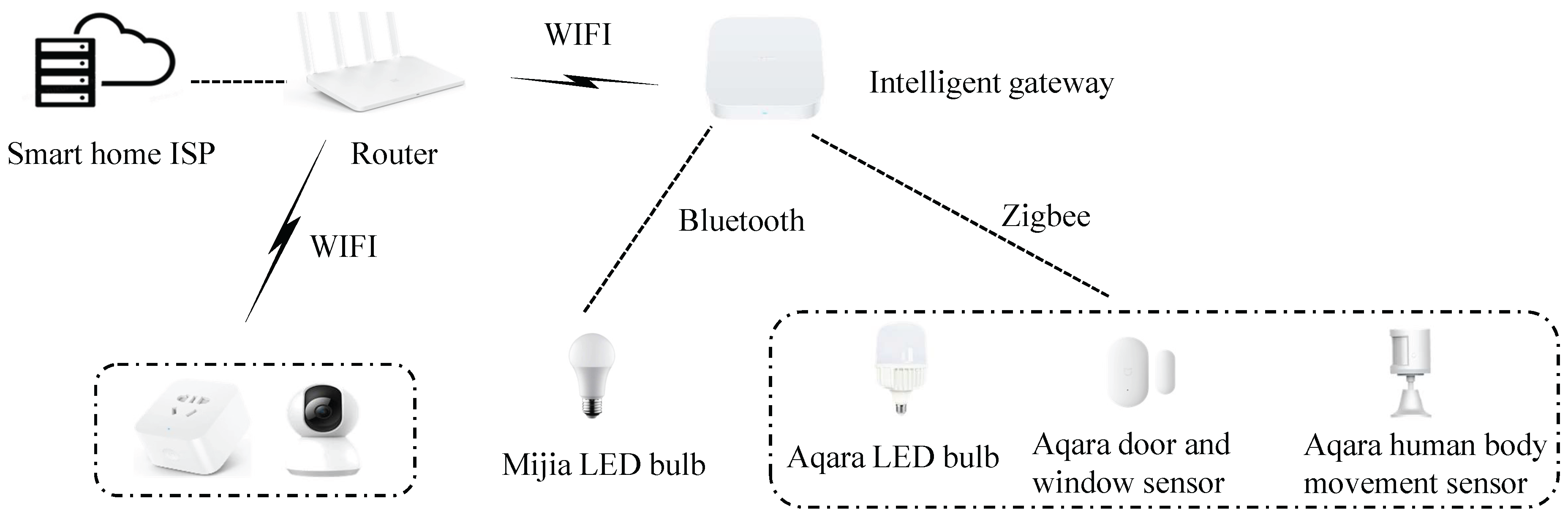

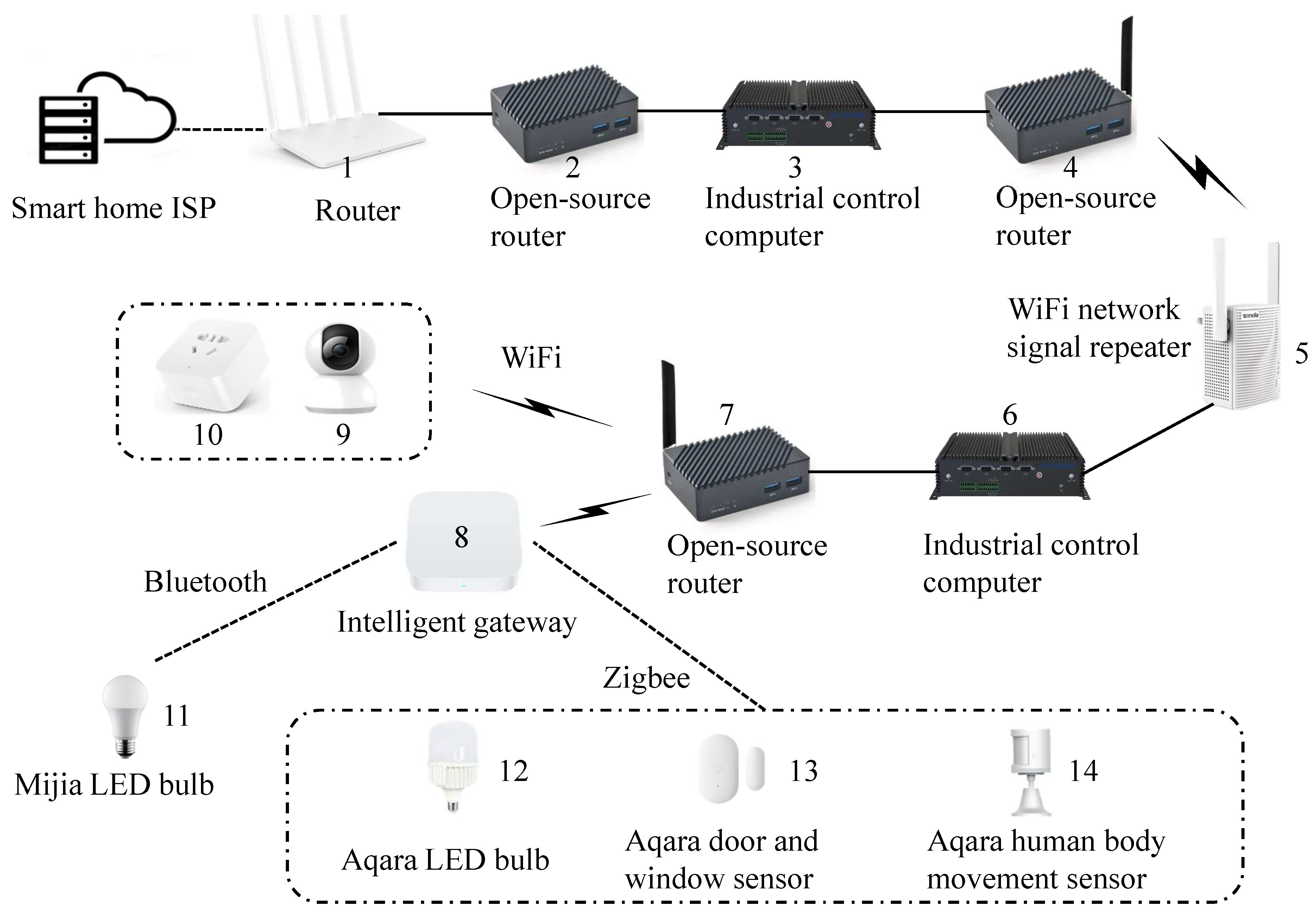

3. Online Traffic Obfuscation Experimental Network

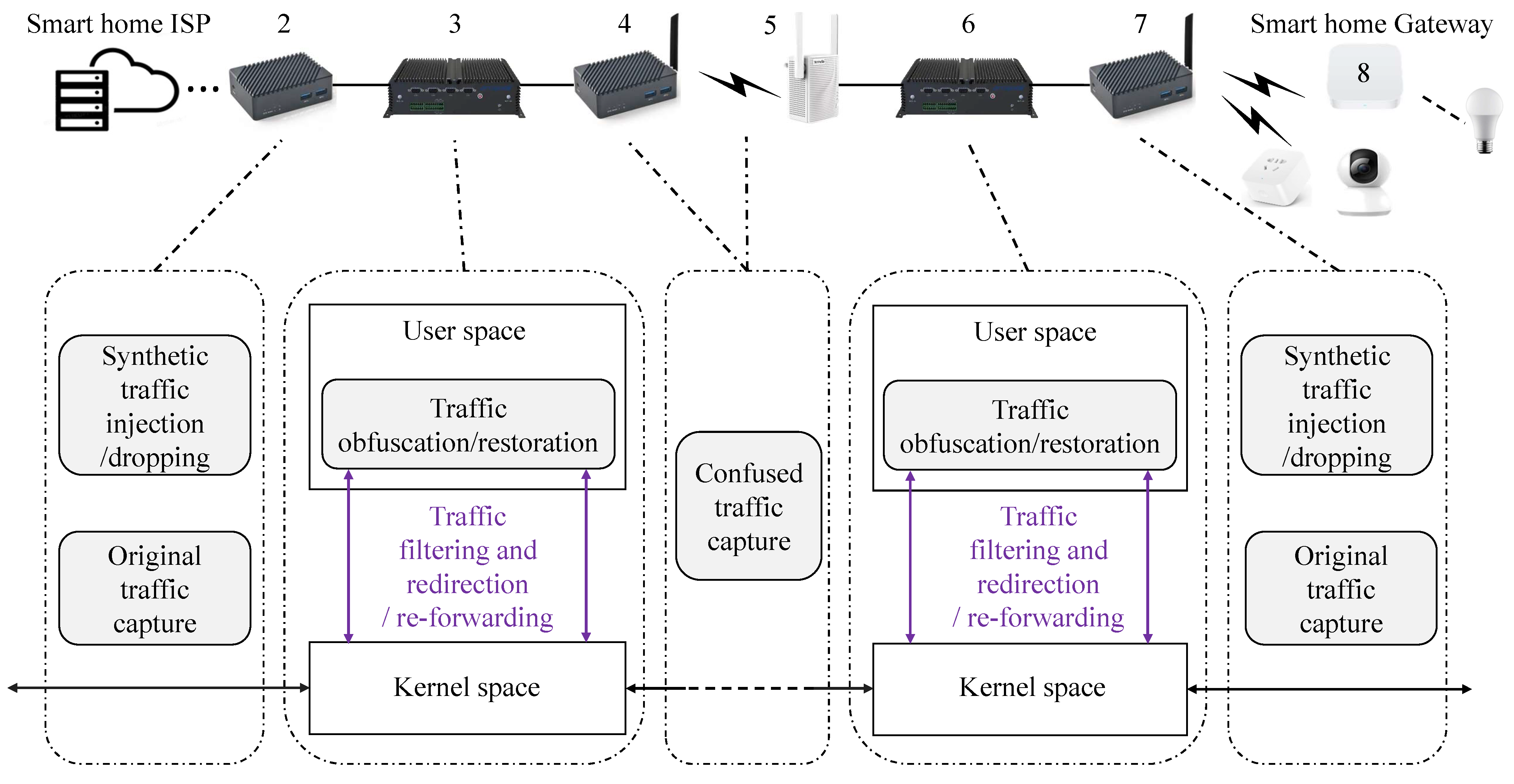

4. Online Traffic Obfuscation Experimental Framework

- (a)

-

Synthetic traffic injection/terminationBased on the interaction traffic (captured in PCAP files) between the server and smart home devices, synthetic packets are constructed and injected from node 2 (or node 7). Subsequently, these packets assist node 3 (or node 6) in completing the injection of fake traffic, which is subsequently terminated at node 7 (or node 2).

- (b)

-

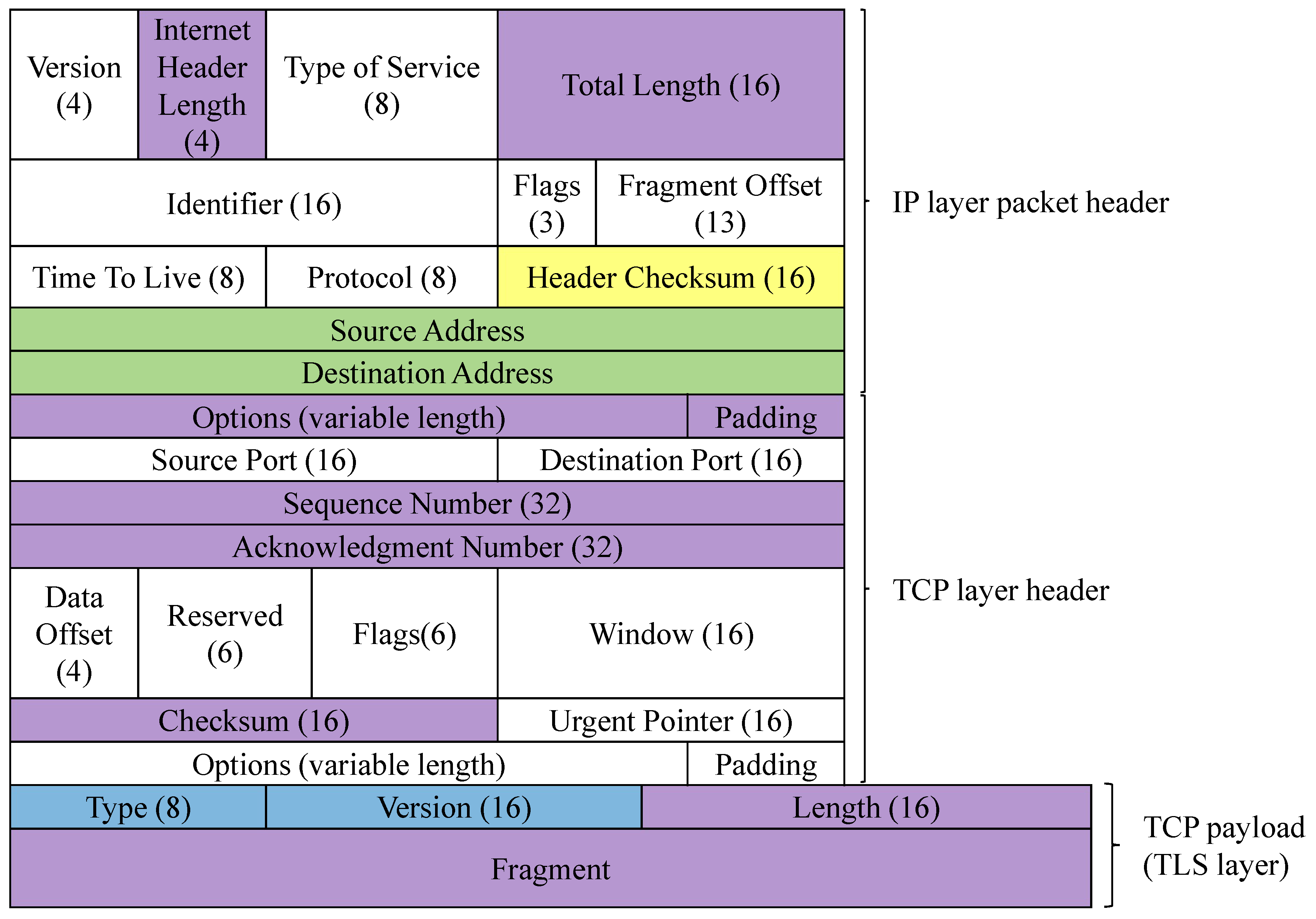

Traffic filtering and redirectionAt nodes 3 and 6, packets are filtered and redirected based on the specified source address or destination address. For instance, the following commands are used to filter and redirect traffic associated with IP address 192.168.2.175 to NFQUEUE queue 1:iptables -A FORWARD -s 192.168.2.175 -j NFQUEUE --queue-num 1iptables -A FORWARD -d 192.168.2.175 -j NFQUEUE --queue-num 1NFQUEUE is a target in the Netfilter framework that enables packets to be passed from the kernel space to user-space programs for processing. User-space programs can utilize the NetfilterQueue library in Python to read packets from a specified queue and determine whether to accept, drop, or alter the packets as required. The structure of these packets is illustrated in Figure 4, where the numbers in parentheses represent bit lengths. The fields highlighted in the figure indicate where modifications occur: green fields are modified during fake traffic injection, blue during packet segmentation, purple during both padding and segmentation, and yellow during all three operations. Since the data is transmitted over the Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocol, the TCP payload, also referred to as the TLS layer, consists of the , , , and . Here, the and fields record information about the TLS protocol, while the field specifies the length (in bytes) of the .

- (c)

-

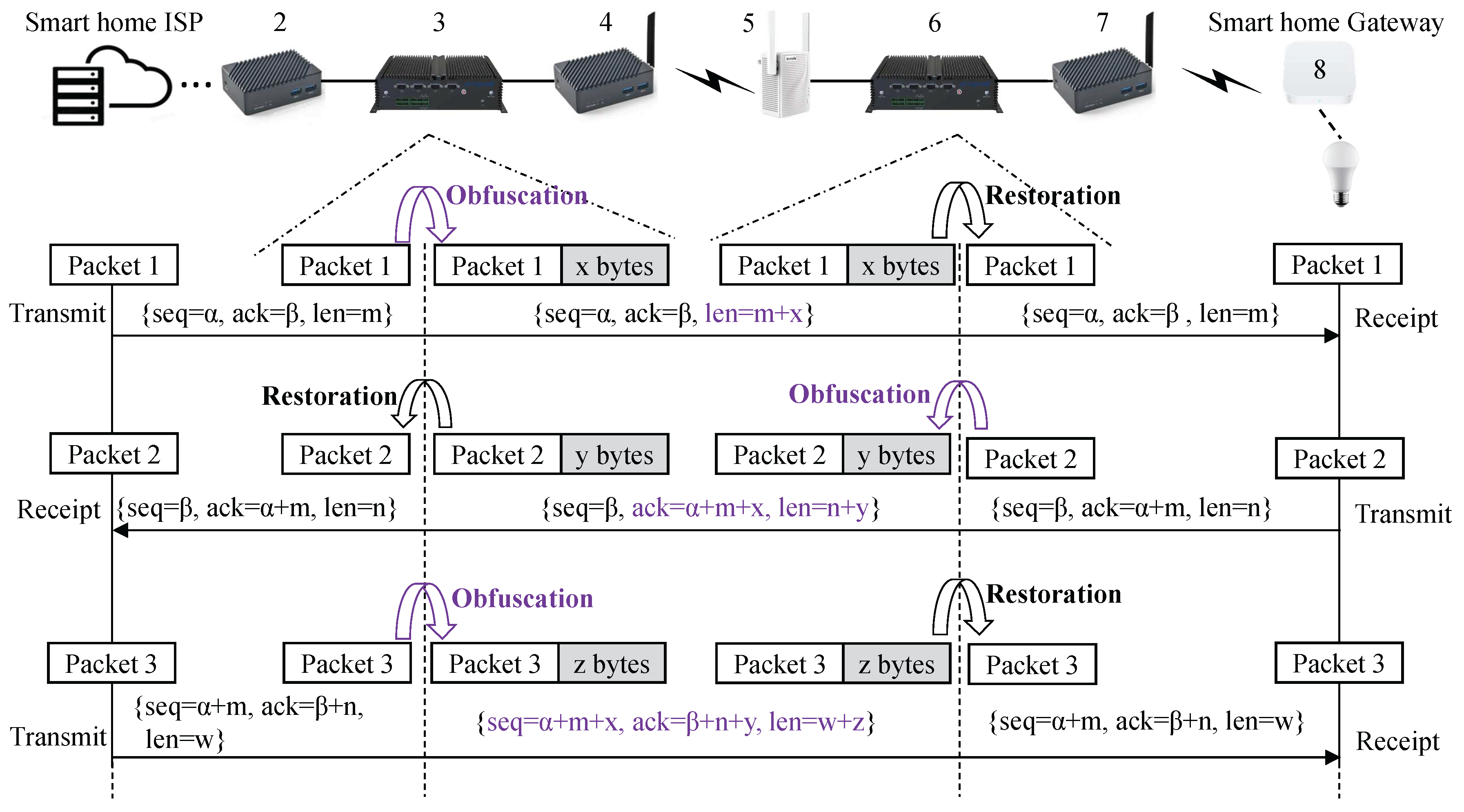

Traffic obfuscation/restorationAt node 3, the downlink traffic (from the server to the home device) is obfuscated, and its characteristics are randomized to decrease the identifiability of specific device traffic. Prior to reaching the home device, the obfuscated downlink traffic is restored to its original content at node 6 as required. Similarly, the uplink traffic (from the home device to the server) undergoes the same process at nodes 6 and 3, respectively, ensuring efficient bidirectional obfuscation and restoration.

- (d)

-

Traffic re-forwardingAfter the specified traffic is obfuscated or restored in user space, it is subsequently reinjected into kernel space and re-forwarded via the packet.accept() method of the NetfilterQueue library, ensuring normal communication.

4.1. Fake Traffic Injection

-

Synthetic traffic injection/terminationSynthetic traffic is a foundational type of traffic specifically designed to enable controllability and emulate real device behavior, serving as a critical support mechanism for fake traffic injection strategies. On nodes 2 and 7, leveraging the captured device traffic (PCAP files), the Scapy library is employed to synthesize and inject network traffic, thereby simulating realistic bidirectional communication processes. This approach circumvents the operating system’s TCP/IP protocol stack, enabling direct transmission of custom packets via Scapy’s send() function, thus enhancing controllability.In the packet injection process, various fields of IP and TCP layers can be modified flexibly as required. Additionally, packets without TCP "Reserved" field can be constructed, as this field are generally unused in the network traffic of real devices, making the structure of the generated traffic more closely aligned with actual traffic patterns. Although no actual transport-layer connection (e.g., a TCP three-way handshake) is established, key parameters such as timestamps, IP and port combinations, and sequence numbers can be utilized to reconstruct a seemingly legitimate and continuous bidirectional communication trace. The synthetic traffic constructed on node 2 eventually reaches the destination node 7, and vice versa, with the traffic from node 7 ultimately arriving at node 2, thereby completing the termination process.

-

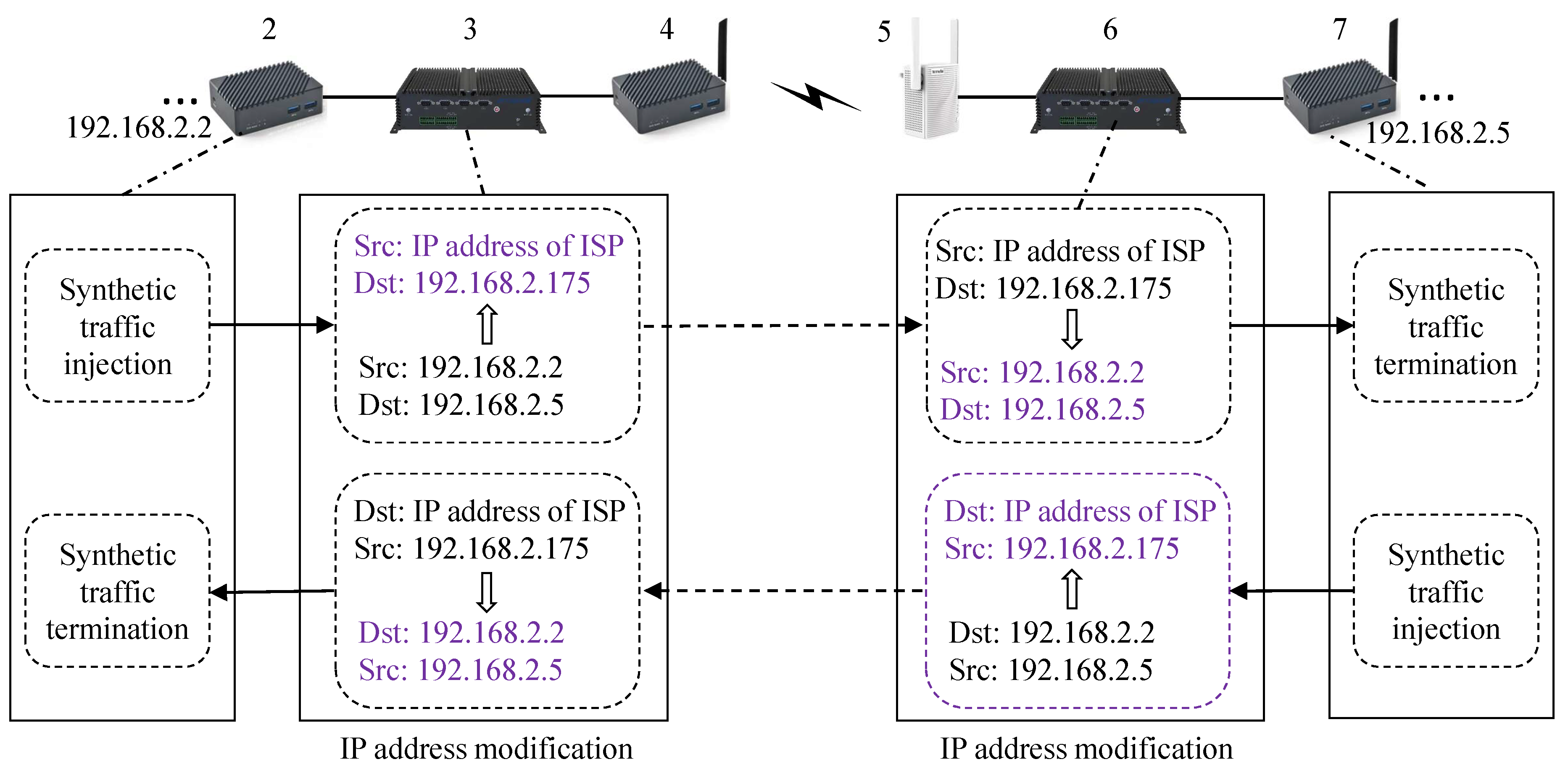

IP address modificationFor downlink traffic, the process of fake traffic injection and elimination is as follows. Traffic originating from node 2 and destined for node 7 is intercepted in user space from kernel space at node 3. Subsequently, the source address of the packet is modified from 192.168.2.2 to the IP address of the smart home server, while the destination address is modified to the IP address of a device within the smart home network (e.g., 192.168.2.175). The modified packet is then reinjected into kernel space for re-forwarding. At node 6, traffic with a source address corresponding to the smart home server IP and with a designated destination address (e.g., 192.168.2.175) is again intercepted in user space. The source and destination addresses of the packet are subsequently restored to 192.168.2.2 and 192.168.2.5, respectively. Finally, the modified traffic is reinjected into kernel space for further forwarding.For uplink traffic, similar to the aforementioned process, fake traffic injection and elimination operations are carried out at nodes 6 and 3, respectively.

4.2. Packet Padding

4.2.1. Implementation Principles of Packet Padding

-

Packet paddingAt node 3, the packets destined for home devices are intercepted into the user space. The TCP payload of each packet is extended with a random-length padding. This padding is encrypted using the encryption method agreed upon between nodes 3 and 6, and the corresponding length information is stored in the IP header field. The padding consists of random characters and is appended to the end of the TCP payload. Several fields are modified, including the IP , , , and fields; the TCP (), (), and fields; as well as the TLS field. The positions of these fields are illustrated in Figure 4. Subsequently, the padded packet is re-forwarded.

-

Packet restorationAt node 6, the packets destined for home devices are intercepted again into the user space. The packet is restored by removing a specific number of characters from the end of the TCP payload, where the number of characters to be removed is obtained from the IP header field. The relevant fields need to be modified. Subsequently, the restored packet is re-forwarded.

4.2.2. Key Algorithms for Packet Padding

| Algorithm 1 Calculate , and at Node 3 |

|

Input: , , , , , l, ,

Output: , ,

|

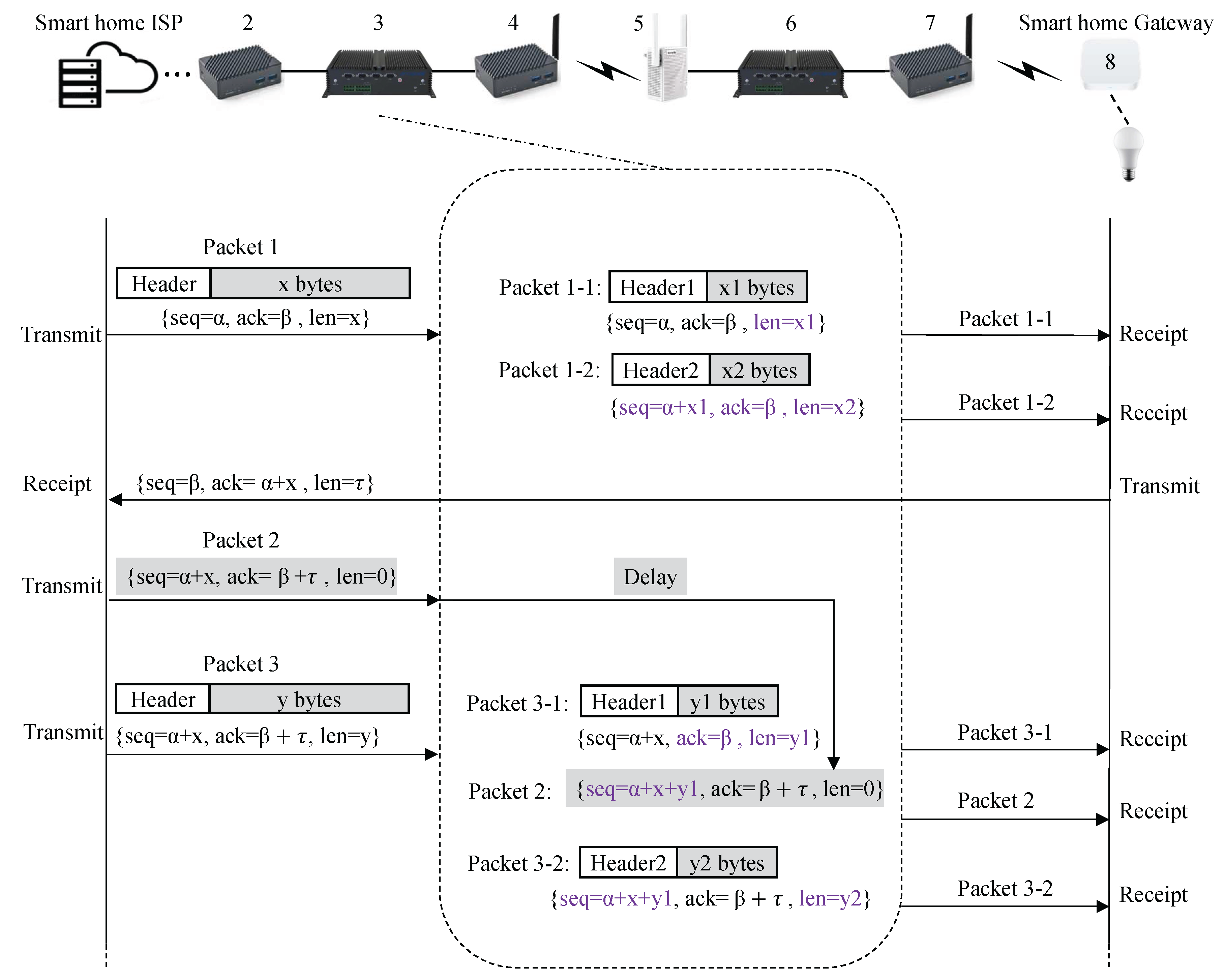

4.3. Packet Segmentation

5. Performance Analysis

5.1. Continuous Connectivity and Functionality of Devices

5.2. Traffic Statistical Characteristics

5.3. Device Event Recognition Rate

5.3.1. The Impact of False Traffic Injection on the Device Event Recognition Rate

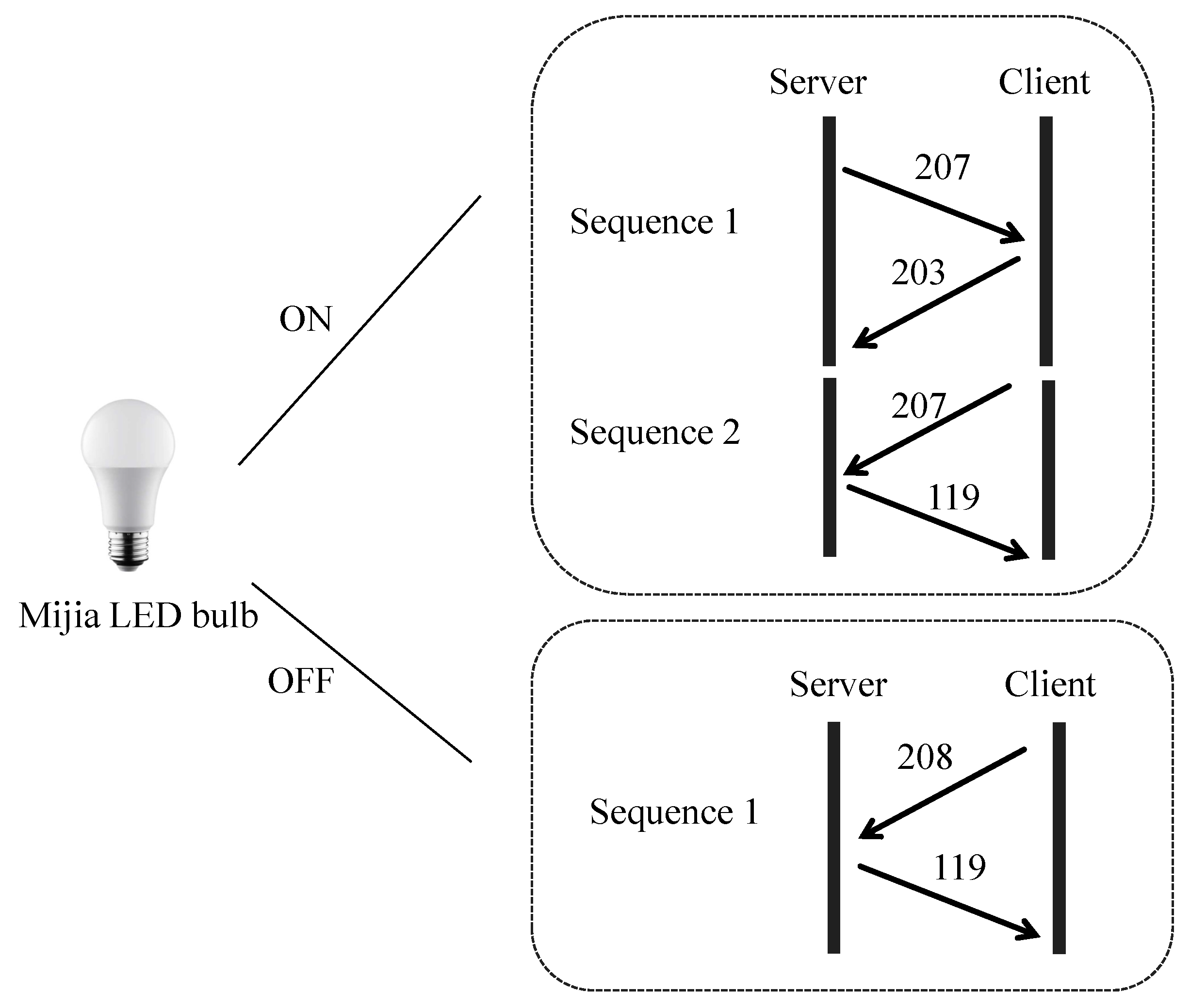

- Data Preparation and Model Training: The on/off event fingerprint features of the Mijia LED bulb are extracted from a CSV file. Labels are uniformly appended, and the data are merged. Additionally, the direction and event types are encoded for further processing. Subsequently, the sequence of packets within these fingerprints (comprising combinations of packet size and direction) is utilized to train a random forest classifier, enabling accurate recognition of device types and their corresponding events.

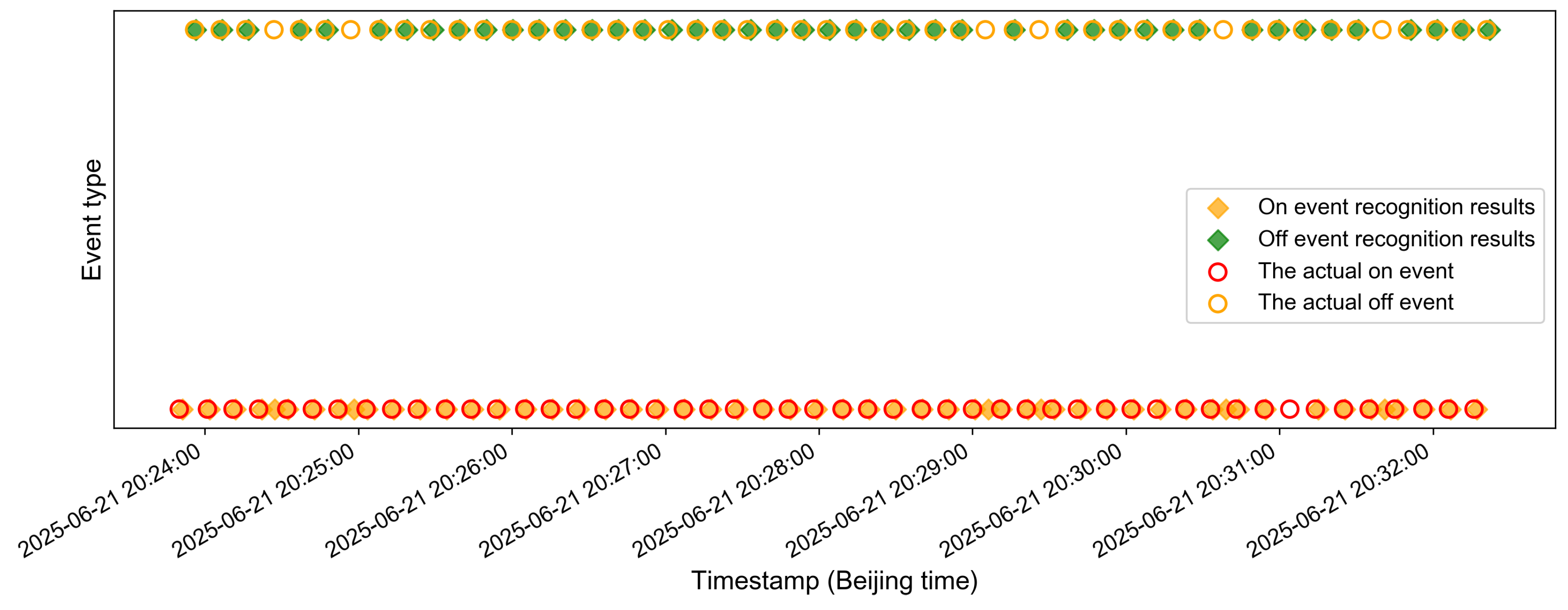

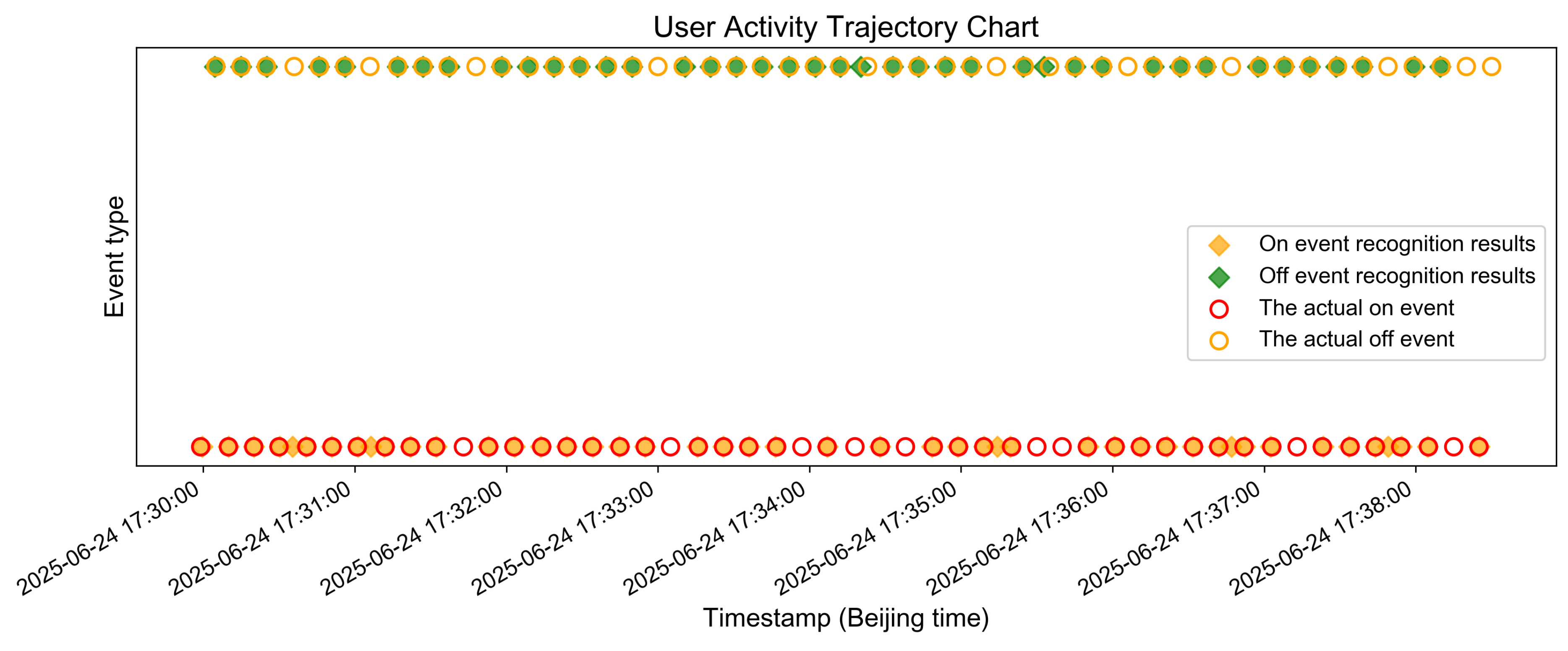

- Traffic Analysis and Device Event Recognition: The size of TCP packets and their timestamp information are extracted from the PCAP file and matched with the features of the packet sequences in the training set in terms of timing to filter out the time segments that meet the requirements. After that, the matched data sequences are predicted using the trained model to recognize the device events corresponding to them. The recognition results for Mijia LED bulb On/Off events before and after fake traffic injection are presented in Figure 10 and Figure 11, respectively.

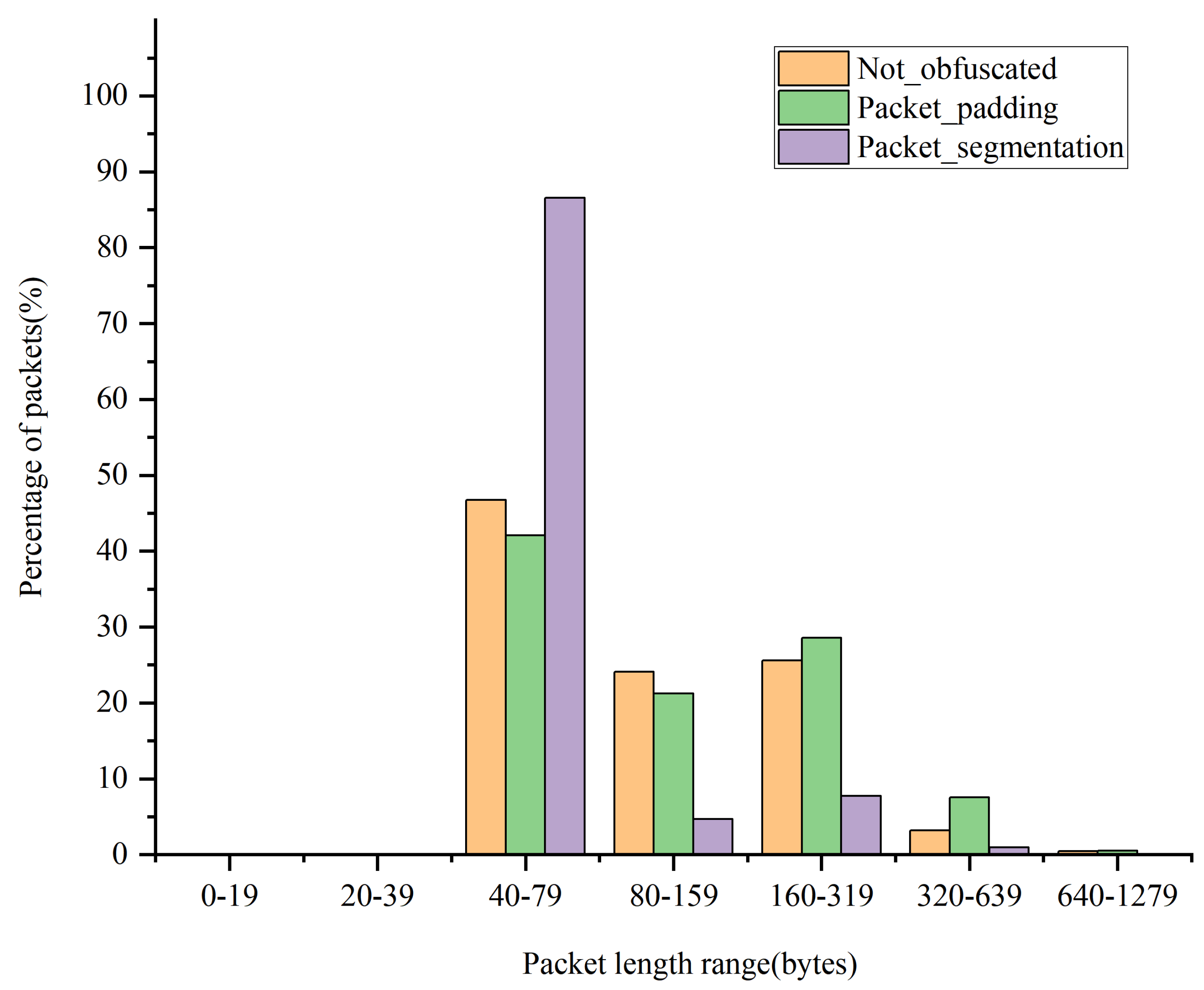

5.3.2. The Impact of Packet Padding and Segmentation on the Device Event Recognition Rate

5.4. Device Recognition Rate

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grand View Research. Smart Home Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Product (Security & Access Controls, Lighting Control), By Protocol (Wired, Wireless, Hybrid), By Application (New Construction, Retrofit), By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2025-2030. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/smart-homes-industry, 2025.

- Skowron, M.; Janicki, A.; Mazurczyk, W. Traffic Fingerprinting Attacks on Internet of Things Using Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 20386–20400. [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.S.; Islam, M.S.; Hossain, M.S.; Das, A. Detecting Smart Home Device Activities Using Packet-Level Signatures From Encrypted Traffic. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing 2025, 22, 1070–1081. [CrossRef]

- Apthorpe, N.; Reisman, D.; Feamster, N. Closing the Blinds: Four Strategies for Protecting Smart Home Privacy From Network Observers. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP) Workshop on Technology and Consumer Protection (ConPro ’17), IEEE, San Jose, CA, USA, 25, May 2017; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Jmila, H.; Blanc, G.; Shahid, M.R.; Lazrag, M. A Survey of Smart Home IoT Device Classification Using Machine Learning-Based Network Traffic Analysis. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 97117–97141. [CrossRef]

- Datta, T.; Apthorpe, N.; Feamster, N. A Developer-Friendly Library for Smart Home IoT Privacy-Preserving Traffic Obfuscation. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM Special Interest Group on Data Communication (SIGCOMM) Workshop on IoT Security and Privacy (IoT S&P ’18), ACM, Budapest, Hungary, 20, Aug. 2018; pp. 43–48. [CrossRef]

- Apthorpe, N.; Huang, D.Y.; Reisman, D.; Narayanan, A.; Feamster, N. Keeping the Smart Home Private with Smart (er) IoT Traffic Shaping. In Proceedings of the 2017 Privacy Enhancing Technologies Symposium (PETS), Minneapolis, USA, 18-21 Jul. 2019; Vol. 2019, p. 128–148. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Kennedy, S.; Li, H.; Hudson, K.; Atluri, G.; Wei, X.; Sun, W.; Wang, B. Fingerprinting Encrypted Voice Traffic on Smart Speakers with Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 13th ACM Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks (WiSec ’20), ACM, Linz, Austria, 8-10, Jul. 2020; pp. 254–265. [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, A.; Granley, J.; Yue, C. Attacking and Protecting Tunneled Traffic of Smart Home Devices. In Proceedings of the Tenth ACM Conference on Data and Application Security and Privacy (CODASPY ’20), ACM, New Orleans, LA, USA, 16-15, Mar. 2020; pp. 259–270. [CrossRef]

- Sivanathan, A.; Sherratt, D.; Gharakheili, H.H.; Radford, A.; Wijenayake, C.; Vishwanath, A.; Sivaraman, V. Characterizing and Classifying IoT Traffic in Smart Cities and Campuses. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS), IEEE, Atlanta, GA, USA, 1-4, May 2017; pp. 559–564. [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, A.J.; de Araujo-Filho, P.F.; Bezerra, J.d.M.; Campelo, D.R. Adaptive Packet Padding Approach for Smart Home Networks: A Tradeoff Between Privacy and Performance. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2021, 8, 3930–3938. [CrossRef]

- Sivanathan, A.; Gharakheili, H.H.; Loi, F.; Radford, A.; Wijenayake, C.; Vishwanath, A.; Sivaraman, V. Classifying IoT Devices in Smart Environments Using Network Traffic Characteristics. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing 2019, 18, 1745–1759. [CrossRef]

- Brahma, J.; Sadhya, D. Preserving Contextual Privacy for Smart Home IoT Devices With Dynamic Traffic Shaping. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 11434–11441. [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Dubois, D.J.; Choffnes, D.; Mandalari, A.M.; Kolcun, R.; Haddadi, H. Information Exposure From Consumer IoT Devices: A Multidimensional, Network-Informed Measurement Approach. In Proceedings of the ACM Internet Measurement Conference (IMC ’19), ACM, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 21-23, Oct. 2019; pp. 267–279. [CrossRef]

- Alyami, M.; Alkhowaiter, M.; Al Ghanim, M.; Zou, C.; Solihin, Y. MAC-Layer Traffic Shaping Defense Against WiFi Device Fingerprinting Attacks. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), IEEE, Rhodes, Greece, 30 Jun.–03 Jul. 2022; pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Shen, F.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Lv, X. A Novel Traffic Obfuscation Technology for Smart Home. Electronics 2023, 12, 3477. [CrossRef]

- Alyami, M.; Alghamdi, A.; Alkhowaiter, M.A.; Zou, C.; Solihin, Y. Random Segmentation: New Traffic Obfuscation against Packet-Size-Based Side-Channel Attacks. Electronics 2023, 12, 3816. [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, A.J.; Bezerra, J.M.; Campelo, D.R. Packet Padding for Improving Privacy in Consumer IoT. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), IEEE, Natal, Brazil, 25-28 Jun. 2018; pp. 00925–00929. [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, I.; Antikainen, M.; Tarkoma, S. Protecting IoT-environments against Traffic Analysis Attacks with Traffic Morphing. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE international conference on pervasive computing and communications workshops (PerCom Workshops), IEEE, Kyoto, Japan, 11-15 Mar. 2019; pp. 196–201. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Yang, C.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Shao, J. Smart home: Keeping privacy based on Air-Padding. IET Information Security 2021, 15, 156–168. [CrossRef]

- Trimananda, R.; Varmarken, J.; Markopoulou, A.; Demsky, B. Packet-Level Signatures for Smart Home Devices. In Proceedings of the Network and Distributed Systems Security (NDSS) Symposium, San Diego, CA, USA, 23-26 Feb. 2020; pp. 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Ma, X.; Li, J.; Luo, X.; Xue, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Feng, L.; Guan, X. An Input-Agnostic Hierarchical Deep Learning Framework for Traffic Fingerprinting. In Proceedings of the 32nd USENIX security symposium (USENIX Security 23), Anaheim, CA, USA, 9-11 Aug. 2023; pp. 589–606. https://www.usenix.org/system/files/usenixsecurity23-qu.pdf.

- Shen, M.; Ji, K.; Gao, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhu, L.; Xu, K. Subverting Website Fingerprinting Defenses with Robust Traffic Representation. In Proceedings of the 32nd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 23), Anaheim, CA, USA, 9-11 Aug. 2023; pp. 607–624. https://www.usenix.org/system/files/usenixsecurity23-shen-meng.pdf.

| No | IP address | Equipment name | Network mode | Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 192.168.2.1 | Router | Ethernet | Ordinary home router |

| 2 | 192.168.2.2 | Open-source router | Ethernet | Nanopi R5S OpenWrt OS 4G Memory |

| 3 | 192.168.2.21 | Industrial control computer | Ethernet | Ubuntu OS G590-Pentium 7505 CPU DDR4 8G Memory |

| 4 | 192.168.2.3 | Open-source router | Ethernet / WiFi | Nanopi R5S OpenWrt OS 4G Memory |

| 5 | 192.168.2.4 | WiFi repeater | Ethernet / WiFi | Tenda WiFi network repeater |

| 6 | 192.168.2.22 | Industrial control computer | Ethernet | Ubuntu OS G590-Pentium 7505 CPU DDR4 8G Memory |

| 7 | 192.168.2.5 | Open-source router | Ethernet / WiFi | Nanopi R5S OpenWrt OS 4G Memory |

| 8 | 192.168.2.175 | Intelligent gateway | WiFi / Zigbee / Bluetooth | Xiaomi intelligent multi-mode gateway |

| 9 | 192.168.2.149 | Camera | WiFi | Xiaomi intelligent camera |

| 10 | 192.168.2.204 | Smart socket | WiFi | Xiaomi smart socket |

| 11 | / | LED bulb | Bluetooth | Mijia LED bulb |

| 12 | / | LED bulb | Zigbee | Aqara LED bulb |

| 13 | / | Door/window sensor | Zigbee | Aqara door and window sensor |

| 14 | / | Human body movement sensor | Zigbee | Aqara human body movement sensor |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).