1. Introduction

Being diagnosed with cancer challenges a person's entire life situation, not only leading to physical changes but also mental and emotional ones. The changed life situation also affects family caregivers. However, all individuals are unique and each person reacts to and copes with the situation differently. Allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HCT) is an intensive curative treatment primarily for haematological malignancies with a significant risk of relapse and severe complications, including graft-versus-host disease and complex infections [

1,

2]. The treatment trajectory begins with an initial hospitalisation period of 4–6 weeks, followed by an intensive post-discharge care phase lasting approximately three months and continuing with a prolonged rehabilitation period of 6-12 months. Throughout the allo-HCT process, patients face multifaceted challenges that give rise to physical, psychological, existential and social needs [

1,

2,

3,

4]. These needs are highly individual and dynamic, varying in type and intensity both between patients and over the course of the treatment trajectory [

5].

The social network of family and friends as well as the healthcare team have been shown to be vital in the care of allo-HCT patients [

6]. At the same time, the life situation of family caregivers is profoundly impacted as they navigate their own worries about living with a seriously ill relative [

6], as well as assuming significant responsibilities, providing both physical and psychological support to the patient [

7]. The needs of family caregivers are also highly individual and evolve over time [

8].

To provide patients with the most effective care, medical and nursing interventions must be carefully tailored to the unique circumstances of each individual. This highlights the importance of person-centredness as a key approach to meeting the complex and evolving needs of both patients and their family caregivers [

9,

10]. Registered nurses (RNs) play a pivotal role in this process, as they are uniquely positioned to assess and manage patient symptoms and offer person-centred support to both patients and family caregivers [

11,

12]. However, there is currently no universal person-centred nursing model, as well as a lack of intervention studies evaluating such models in the allo-HCT context. Robust documentation of assessed and addressed needs is essential to support continuity and enhance the perceived quality of care. Research consistently highlights discrepancies between clinical actions and documentation, showing that only a fraction of nursing activities or physician interventions are documented in medical records [

13,

14].

In this research project, person-centred nursing is inspired by McCormack and McCance’s person-centred nursing theory [

15] as well as by the University of Gothenburg Centre for Person-centred Care (GPCC) [

16]. Our person-centred nursing approach highlights three core components: the patient’s narrative, partnership and a shared care plan (described in

Box 1), which are systematically integrated by using structured conversation tools designed to assess and address individual needs of both the patient and family caregivers. The process involves four stages: 1) introducing the tool to the patient and family caregiver separately to encourage them to reflect on their current problems and needs, 2) engaging patients and family caregivers in structured conversations with an RN, where they can articulate and prioritise their own identified needs while the nurse facilitates the conversation in a collaborative dialogue, recognising the expertise of the patient or family caregiver as an essential component of the partnership, 3) collaboratively creating a shared care plan that outlines specific support interventions, which may be addressed immediately, managed independently by the patient or family caregiver, or coordinated with the healthcare team, and 4) conducting nurse-led support interventions to address the identified needs, including preparing and supporting patients and family caregivers to manage side effects, needs and distress.

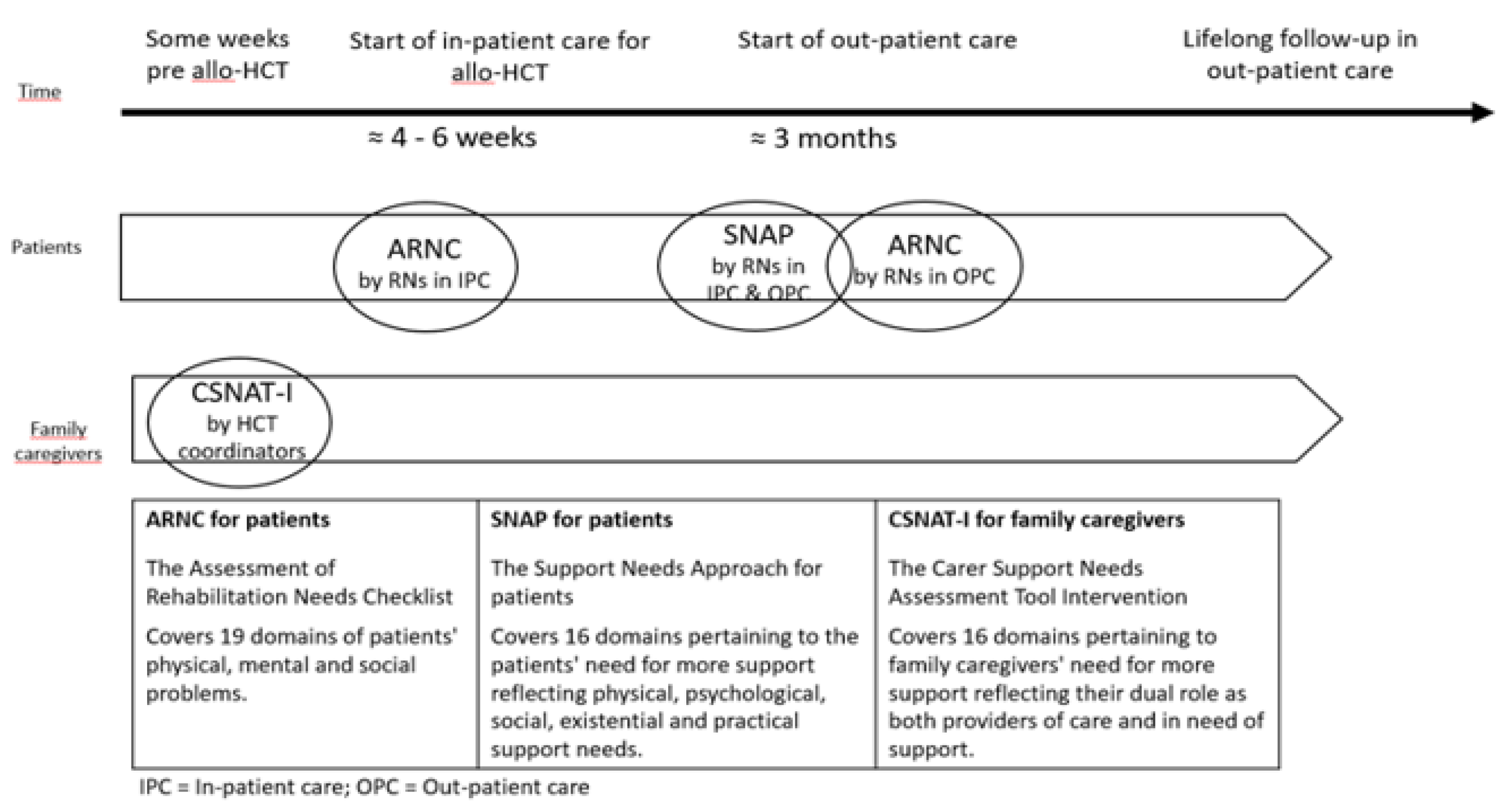

Two conversation tools were selected for patients: The Assessment of Rehabilitation Needs Checklist (ARNC) [

17] and The Support Needs Approach for patients (SNAP) [

18] while one conversation tool was selected for family caregivers, The Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool Intervention (CSNAT-I) [

19,

20]. The ARNC, developed in Sweden, encompasses 19 domains of patients' physical, mental, social and existential problems. Recommended by the National Care programme for Cancer Rehabilitation in Sweden as a tool to assess cancer rehabilitation needs in patients, it is currently being implemented in Swedish cancer care (RCC 2020) and has been validated in a Swedish cancer population [

17]. The SNAP, developed in the UK for patients diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [

18], includes 16 domains covering the patients' self-identified physical, psychological, social, existential and practical support needs, and was recently translated into Swedish and validated [

21]. The CSNAT-I, also developed in the UK in the context of palliative care, includes 16 domains pertaining to family caregivers' self-reported support needs, reflecting their dual role as both providers of care and persons in need of support [

19,

20]. It has been translated into Swedish and validated in a Swedish context [

22] and applied in previous studies by our research group on support for family caregivers in allo-HCT [

8,

23,

24]. A brochure about available support for family caregivers was developed and tested in our previous feasibility study of the CSNAT-I [

24] and is now available at the two Swedish allo-HCT centres where this study was conducted.

The aim of this study was to examine the feasibility of a person-centred nursing model targeting patient and family caregiver needs in the allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation context.

Box 1. Our person-centred nursing model.

Our person-centred nursing model has been designed to address the complex and multifaceted individual needs of both patients and family caregivers within the clinical context of allo-HCT, ensuring a relevant and holistic approach to care. Its development is grounded in established theories, previous research, clinical and pedagogical expertise, as well as the perspectives of end-users. The process was guided by the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions [32], with particular focus on ensuring applicability in clinical settings. Therefore, the model has been developed using Experienced Based Co-Design (EBCD), a participatory research approach that brings together healthcare staff and patients to collaboratively improve the quality of care [31]. Key stakeholders in the research project include managers, “Champions” (selected RNs who have a central role in the project by functioning as a link between the clinics and the researchers), patients and family caregivers at the two largest allo-HCT centres in Sweden participating in the research project. The nursing model includes web-based education for healthcare staff about person-centred nursing and the nursing model with its three tools and how to use them. The education was also developed in a co-creation context [31] and is evaluated in another paper.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

This study employed a feasibility design, focusing on two key aspects: practicality, i.e., the extent to which the model could be applied as intended, and acceptability, i.e., the extent to which participants using the model find it appropriate and satisfactory [

25]. Three aspects of practicality were examined: whether the tools and subsequent conversations were conducted as intended, whether identified needs of patients and family caregivers were addressed by RNs, and the support interventions conducted. Acceptability was examined by analysing the extent to which patients, family caregivers and RNs who used the model found the tools and conversations appropriate and satisfactory. The reporting of this study follows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 extension checklist for pilot and feasibility trials.

2.2. Sample and Procedure

Participants were consecutively recruited from March to September 2023 from the two largest HCT centres in Sweden, in Stockholm and Lund. Inclusion criteria were adult (≥18 years) patients planned to undergo allo-HCT and one of their family caregivers who were able to read and speak Swedish and without cognitive impairment. Patients who met the inclusion criteria were consecutively informed briefly about the ongoing study by the HCT coordinators, all of whom were RNs, and asked to nominate a family caregiver involved in their everyday life. With the patient’s consent, the HCT coordinator forwarded the contact details of the patient and family caregiver to the study coordinator, who then contacted the patient by telephone to provide more detailed information about the study and invite them to participate. If the patient agreed to participate, they were asked to permit the study coordinator to contact the family caregiver to invite them to participate as well. Upon agreement, written study information was provided by post. If the patient consented, the family caregiver received both written and oral information about the study and was invited to participate. A total of 76 patients were assessed for eligibility during this period. Of these, 11 did not meet the inclusion criteria, nine due to non-Swedish language proficiency and two due to cognitive impairment, leaving 65 patients eligible for participation. Among the eligible participants there was a total attrition of 29 patients, due to declining participation (n=17), administrative failures (n=6), lack of response (n=4) and cancelled or postponed transplantation (n=2), resulting in 36 patients included in the study (55% participation rate). Three patients declined family caregiver participation, while all but one of the invited family caregivers agreed to participate, resulting in the inclusion of 32 family caregivers (97% participation rate). No eligibility criteria changes were made after commencement of the recruitment. The characteristics of the 36 patients and 32 family caregivers are presented in

Table 1.

A description of the three conversation tools (ARNC, SNAP and CSNAT-I) and the time points at which they were used are presented in

Figure 1. All RNs working in the participating wards conducted the conversations using these tools.

2.3. Data Collection

To examine the practicality of the model, data were collected by gathering all completed conversation tools (ARNC in in-patient care n=31, ARNC in out-patient care n=33, SNAP n=24 and CSNAT-I n=30), as well as data from the RNs’ documentation in the patients’ medical records from conversations conducted using the ARNC (in-patient care n=34, out-patient care n=35) and SNAP (n=28). Additionally, data from the RNs’ documentation of support plans when using the CSNAT-I (n=30) were collected. No modifications were made to the predefined criteria or procedures for assessing the practicality or acceptability of the model after the start of the study. To examine the acceptability of the care model, data were collected by semi-structured individual telephone interviews with patients (n=16) and family caregivers (n=15) by three of the authors (AO, CL, KB) and one PhD student using an interview guide. The interviews were intended to evaluate the participants’ experiences of the model and its different parts and whether they found it appropriate and satisfactory. The median duration of the interviews was 40 minutes (range 17-135 min) for patients and 18 minutes (range 9-24 min) for family caregivers. The likely explanation for the longer duration of the patient interviews is the inclusion of additional questions about self-care, reported in another paper. Semi-structured focus group interviews, conducted either digitally or in person, were held with RNs who had used the tools in patient conversations. The interviews were led by three of the authors (AK, AO, LE) and one PhD student, using an interview guide. The interviews were intended to evaluate the RNs’ experiences of the model and the different parts of the model. In total, 16 RNs participated in four focus group interviews: one at each of the two in-patient care units, one with “Champions” (selected RNs who had a central role in the project by functioning as a link between the centres and the research group) together with RNs from one of the out-patient care units, and one with the HCT coordinators from both centres. The median duration of these interviews was 53 minutes (range 46-58 min). All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

2.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to present the characteristics of the participants. To examine the practicality of the model, i.e., whether the tools and subsequent conversations were conducted as intended, data from completed conversation tools and the documentation pertaining to the conversations were summarised. Furthermore, to examine whether identified needs were addressed by RNs and what support interventions were conducted, data from the tools and documentation of the conversations were analysed and summarised.

To examine the acceptability of the model and the use of the three conversation tools (ARNC, SNAP and CSNAT-I), content analysis was applied to the interviews [

26]. The transcribed patient interviews were read through independently several times by two of the authors (AMK, LE), the transcribed interviews with family caregivers by one author (LE) and the transcribed focus group interviews with RNs by two authors (AMK, AS). When identifying meaning units among the experiences associated with each tool and labelling them with codes, it emerged that the participants' experiences of using the tools could be divided into the following categories: positive, negative, neutral and both positive and negative. Discussion and further analysis among four of the authors (AMK, AS, LE and JW) led to the data being categorised and quantified based on each participant’s experiences of each tool (

Table 2). Furthermore, the content analysis led to descriptions of the experiences associated with each tool. All authors read and validated the entire result, with adjustments made until consensus was achieved.

3. Results

The result is presented with reference to practicality, i.e., to what extent the model could be carried out as intended and acceptability, i.e., the extent to which participants found the model appropriate and satisfactory. Practicality includes whether the tools were used and the conversations conducted as intended, if identified needs were addressed and what support interventions were described in the documentation. Acceptability includes participants’ overall experiences of using the three different tools and participating in the conversations.

3.1. Practicality of the Model

3.1.1. Use of Tools and the Subsequent Conversation

The results show that the different parts of the model, i.e., the three conversation tools (ARNC, SNAP and CSNAT-I) and the subsequent conversations, were applied as intended to 78-97% of the participants in the study. The ARNC was applied as intended to the highest extent, in 94% of the in-patients and 97% of the out-patients, while the SNAP was applied as intended in 78% of patients and CSNAT-I in 88% of family caregivers.

3.1.2. Identified Needs Addressed

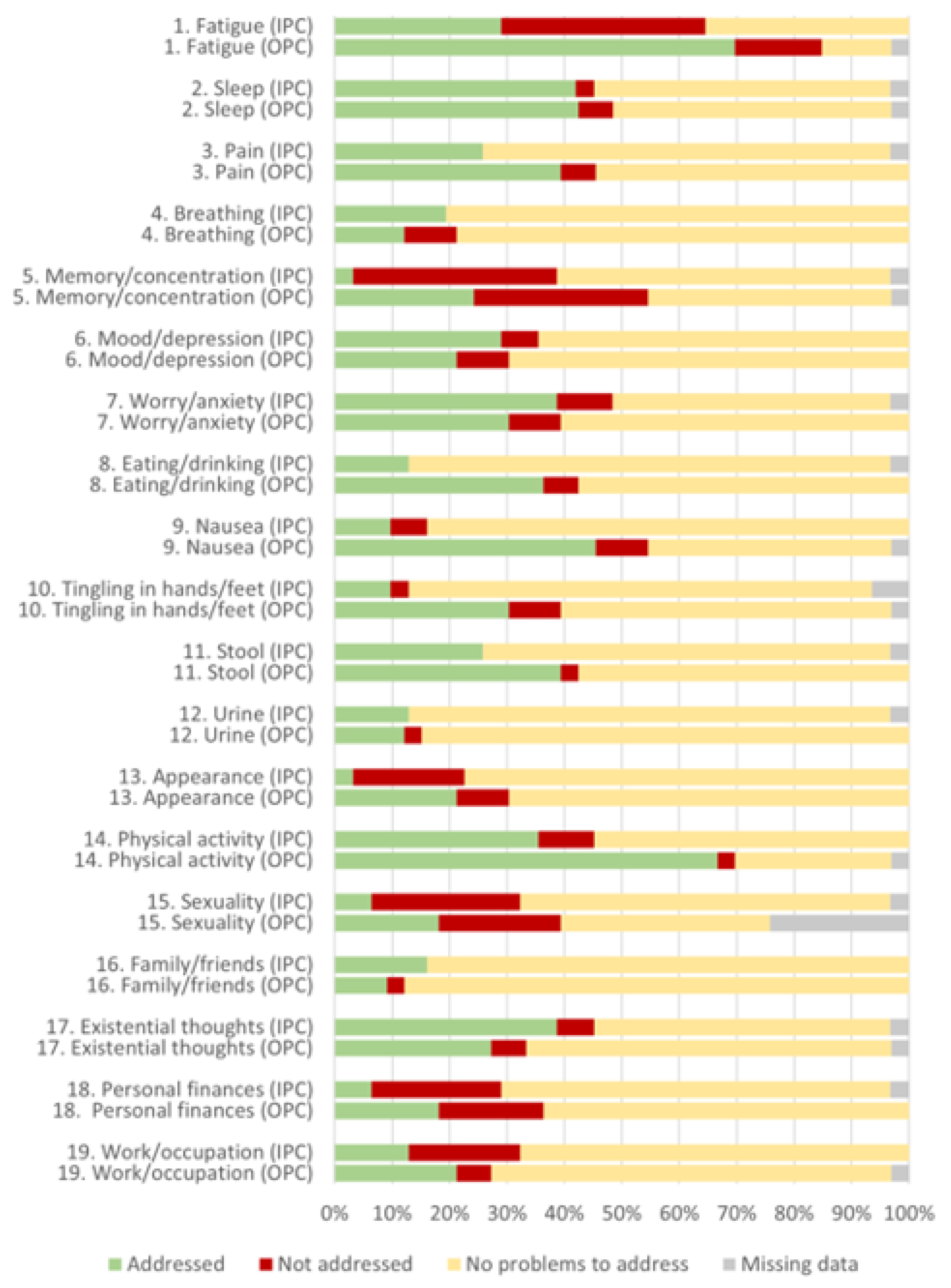

According to the ARNC, many patients reported problems, indicating that their individual needs were identified, of which the majority were addressed in both in-patient and out-patient care (

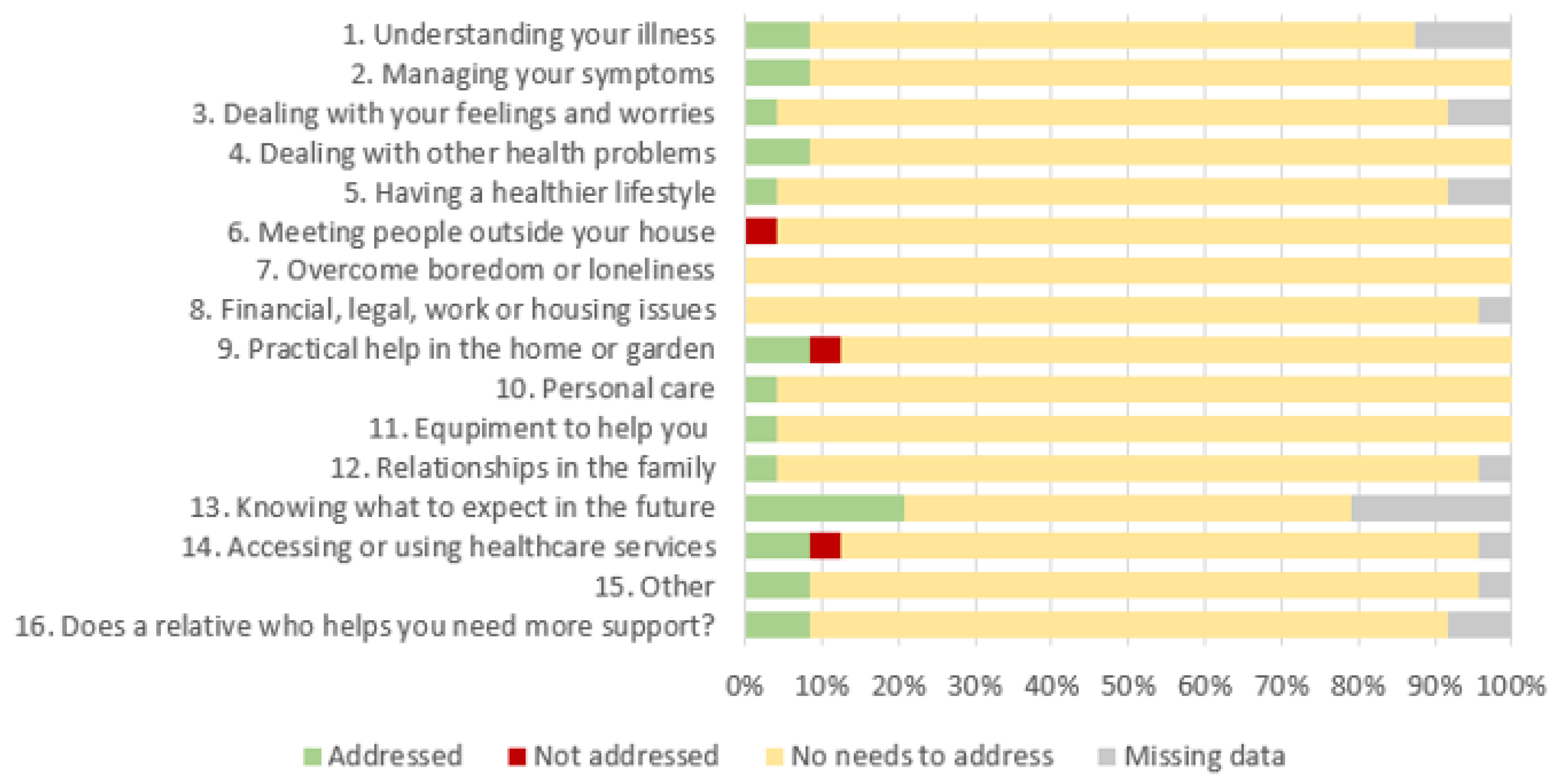

Figure 2). However, in general a higher proportion of identified needs were addressed in out-patient care compared to in-patient care. In all ARNC domains there was at least one patient whose needs were not addressed. Additionally, needs were less often addressed by the RN in the following domains: fatigue, memory/concentration, mood/depression, appearance, sexuality, personal finances and work/occupation. According to the SNAP few patients reported support needs, but most of those mentioned were addressed (

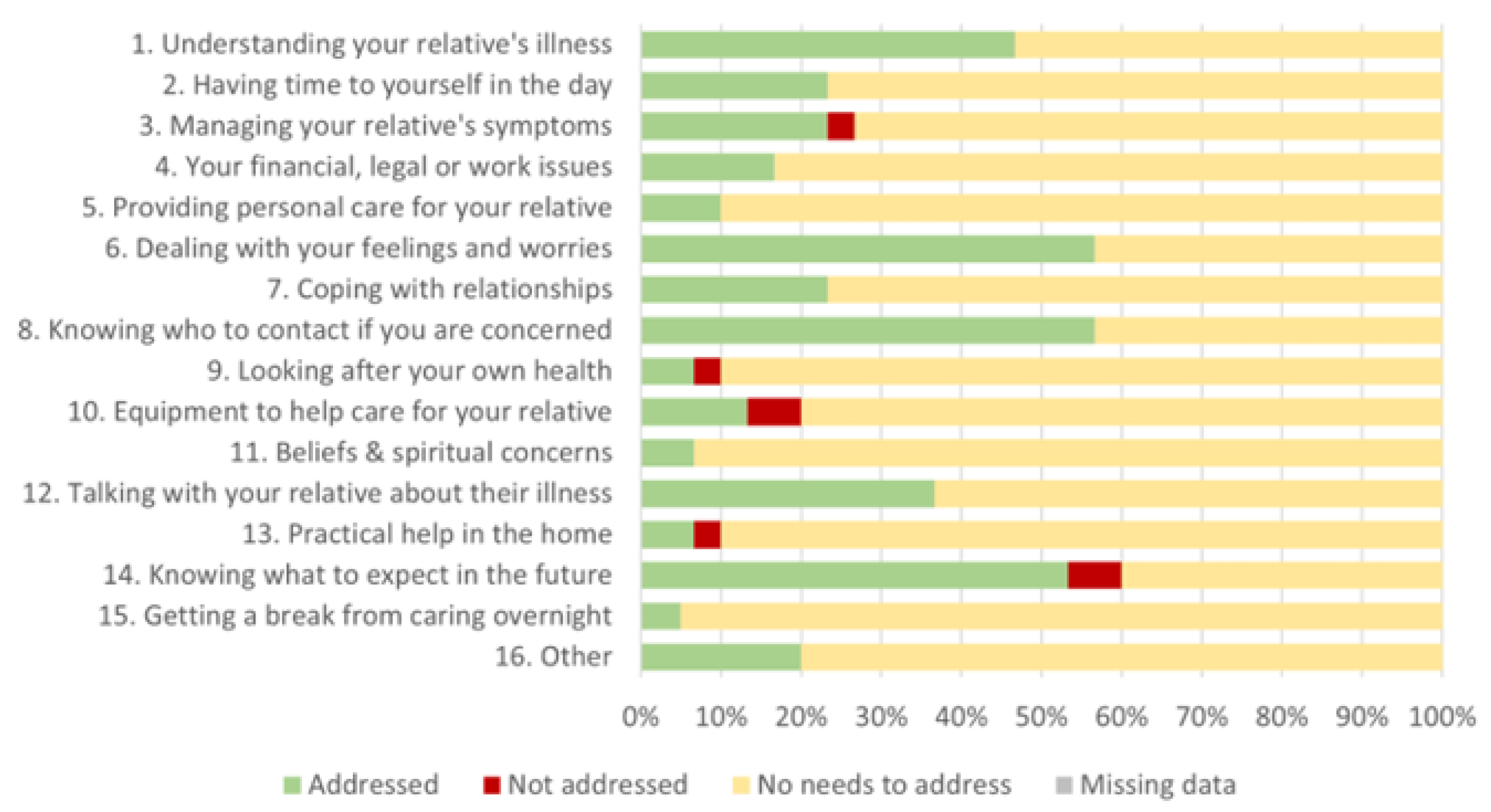

Figure 3). The most common domain in the SNAP in which patients had a support need was “knowing what to expect in the future”, which in all cases was addressed by the RN. Two domains were not reported by any of the patients: “overcome boredom or loneliness” and “financial, legal, work or housing issues”. However, in the following domains support needs were less often addressed: meeting people, practical support and gaining access to services in healthcare services. According to the CSNAT-I, many family caregivers had support needs and most of the identified needs were addressed (

Figure 4). All domains in the CSNAT-I were used. The most common need was “knowing what to expect in the future”, but this was not always addressed by the RN. Furthermore, support needs in the domain “Equipment to help care for your relative” were less often addressed.

3.1.3. Support Interventions Conducted

The most common support interventions when using the ARNC were that the RNs provided direct support during the conversation (73% of the RNs in out-patient care and 42% in in-patient care) and followed-up or initiated drug treatment (64% of the RNs in out-patient care and 42% in in-patient care). The most common support intervention when using the SNAP was collaborating with other professionals and units (21% of the RNs), while when using the CSNAT-I the most common support intervention was direct support during the conversation (70% of the RNs) (

Table 3). More support interventions were described in out-patient than in-patient care. Furthermore, the individuals’ own resources were rarely documented when using any of the three tools.

3.2. Acceptability of the Nursing Model

3.2.1. Overall Experiences of Using the Tools and Subsequent Conversations

The analysis of the interviews showed that most patients, family caregivers and RNs found the care model acceptable, expressing that using the tools and having the conversations was experienced as appropriate and satisfactory. In general, the conversation tools and conversations were perceived as separate parts of the care, not as parts of a complete model. In total, 78% of the participants were positive or both positive and negative about using the ARNC, 41% about the SNAP and 95% about the CSNAT-I (

Table 2). However, some patients and family caregivers expressed neutral experiences, i.e., when no needs were identified the tools and conversations were perceived as less appropriate, while other patients and RNs described predominantly negative aspects of using the tools and the subsequent conversations. More detailed descriptions of participants’ experiences of using the three conversation tools and the conversations are presented below.

3.2.2. Experiences of Using the ARNC Tool

Patients and RNs generally found using this tool appropriate and satisfactory. They experienced it as straightforward, simple and valuable, in admissions to both in-patient and out-patient care. Patients valued the relevance and understood the purpose of the domains, noting that the tool also enhanced communication with healthcare professionals and facilitated the monitoring of problems across various health domains. Patients also reported increased awareness of specific health issues and felt supported in managing symptoms. They valued the tool’s ability to encourage self-reflection on current and potential future needs, particularly regarding employment and financial matters as they relate to ongoing health issues. Information provided about additional support services, such as financial counselling, was particularly appreciated.

The appropriateness of the tool experienced by both patients and RNs concerned the fact that the domains were perceived as relevant, facilitating an overview of which domains to focus on and identifying where patients needed more information and support. The tool enabled an open dialogue where patients felt more involved in choosing what to discuss and made it easier for them to put their feelings into words, which helped the RNs to understand patients’ needs and focus on important areas. Patients felt acknowledged and supported by the RN. RNs experienced that the conversations focused on the troublesome aspects, meaning that they did not have to spend much time on areas where the patient did not indicate any needs, which was timesaving, efficient and enabled them to adjust the care. The tool facilitated a good structure for their conversations with patients and allowed the RNs to offer self-care advice as well as support from other healthcare professionals. Patients also expressed satisfaction with the way in which the tool facilitated open conversations about sensitive domains such as sexuality and made these conversations more approachable and comfortable, which some patients found empowering. RNs stated that using the tool was appropriate in terms of raising domains that RNs usually do not discuss. Some patients expressed ambivalence about the benefit of the tool because it made them think more about their health issues.

RNs also reported that the tool was not experienced as appropriate in all situations, e.g., when patients were not interested in nor willing to share their feelings or experiences. RNs also experienced that older patients and those with cognitive difficulties could find using the tool challenging, but that the participation of family caregivers was often valuable in such situations, as they could help describe the patient’s perspective. However, some RNs also observed that that the presence of family caregivers during the conversations could restrict patients, especially in the domain pertaining to family and relatives. An unsatisfactory aspect experienced by RNs was when there was no possibility of being alone with the patient, which made it difficult to have a confidential conversation and follow up the identified needs.

Some RNs experienced that the tool was not appropriate for patients who considered that they had no needs, as they found it pointless. Patients without major concerns also described a sense of superfluousness and some were unsure about the tool’s ability to highlight relevant issues in relation to the amount of information already provided during standard care. Some patients noted a lack of conversation after completion of the tool, which left them sceptical about the tool’s actual benefit. Some RNs experienced dissatisfaction when required interventions did not take place due to the RN’s lack of confidence or knowledge, as well as when there was a sense that a domain was inadequate, which especially applied to the domains of appearance and sexuality.

3.2.3. Experiences of Using the SNAP Tool

Patients experienced the SNAP tool as satisfactory with its comprehensive approach to addressing a broad range of concerns, which were often not initially considered by the patients themselves. The RNs’ mutual understanding was that the tool might be useful for this group of patients, as many of the domains were considered relevant.

Patients experienced that the domains within the tool were proof that the healthcare team was engaged beyond routine care. They found the conversations with RNs beneficial, as they helped to clarify and address domains raised in the tool. A segment of patients described their feelings about the appropriateness of the tool as neutral, acknowledging that while the tool was straightforward to use and included relevant domains, it did not alter their care process or reveal new insights. These patients acknowledged the potential appropriateness of the tool for others who might have more pressing or unaddressed needs, and for patients who were not active or lacked support. Some patients expressed that they had not experienced any impact or changes to their life situation or care from using the tool, which led to scepticism regarding its appropriateness and purpose, hence it was experienced as a bureaucratic exercise rather than a meaningful part of care. Concerns were also raised about the lack of follow-up on issues identified through the tool, leading to questions about its overall purpose and efficacy.

A few patients expressed a need for the tool to be more adaptable to their changing health circumstances, suggesting that its content seemed too general or disconnected from their current situation. Patients who already felt well-supported through existing healthcare processes or personal support systems suggested that the tool might be more effective if introduced at varying stages of care, as many participants noted that their needs were already being met through standard care interactions. The patients pointed out that its appropriateness seemed greater for post-discharge scenarios rather than during an active hospital stay, which would potentially lead to more thoughtfulness and reflective conversations after adjustment to their home environment. RNs also expressed that the timing of using the tool was not optimal and believed it was used too early in the care process. Suggestions about suitable time points for the tool were raised and the RNs thought it would be relevant to use 2-3 months, or even 6-12 months after transplantation. Furthermore, the RNs stated that they had not really understood how to use the tool and how to address some of the domains. Additionally, in some cases the tool was used at the same time as the ARNC, which the RNs found pointless.

3.2.4. Experiences of Using the CSNAT-I Tool

Family caregivers and RNs generally found the tool appropriate and satisfactory. Several family caregivers experienced that the tool itself was user-friendly and identified domains in which they needed more support, such as ‘Dealing with your feelings and worries’ and ‘Knowing who to contact if you are concerned’, highlighting the fact that these areas might not have otherwise been raised. Several family caregivers experienced that the tool helped them to voice their emotions and concerns more openly, reducing anxieties about the ill person’s condition. The conversation validated their experiences and emotional burden, providing them with comfort and a sense of being included in the patient’s care. The use of the tool offered an opportunity to feel acknowledged and supported by the RNs. One common benefit experienced by family caregivers was that the systematic use of tools with conversations improved communication between family caregivers and healthcare professionals and they appreciated receiving practical advice and guidance on available resources to address their needs. Some family caregivers, however, experienced that the tool and the conversation were supplementary rather than essential because they did not align with their needs or were unnecessary due to the fact that they already had a functioning support system. A few family caregivers expressed that some domains were not relevant, e.g., ‘Practical help in the home’ and ‘Providing personal care for your relative’, especially if they were not living with the patient or providing hands-on care. Some highlighted that using the tool raised concerns they had not previously considered, which led to increased anxiety. However, they acknowledged that this might be useful for other family caregivers.

All RNs agreed that it was satisfying to have conversations with family caregivers based on the CSNAT-I tool. Most RNs stated that the tool provided a good structure for the conversation and found it appropriate to ask family caregivers about their support needs. The vast majority experienced that they had sufficient knowledge to be able to give advice and manage what arose in the conversations. However, at the same time they revealed that the most common domain that family caregivers wanted to discuss was worries about what to expect in the future, which felt uncomfortable as it is impossible to foresee the future, thus the RNs were unable to provide an answer to support the family caregiver. Several RNs stated that giving the family caregivers a previously developed brochure about available support was helpful in the conversation and family caregivers appreciated this information about the availability of extra resources. One RN expressed that although all domains in the tool were not relevant on every occasion, it provided an opportunity to inform the family caregivers about where they could seek help at a later stage of the transplantation process. However, RNs revealed that these conversations could be tough and challenging due to the emotional impact on family caregivers. A few RNs also stated that it was difficult to ensure that the conversation did not take too long, because some family caregivers had a great need of support. All RNs who conducted these conversations were HCT coordinators and they expressed that someone else might be better suited to conducting these conversations due to their lack of time and a perception that this was not really part of their work. The HCT coordinators also experienced confidentiality issues in that it could feel as if they were keeping secrets from the patient after the conversation with the family caregiver.

The use of the CSNAT-I to engage family caregivers in the care process before patients’ admission to inpatient care was generally well received. Some family caregivers and RNs felt that the conversations occurred too early, addressing domains that were not immediately relevant, and with a need for follow-up of CSNAT-I conversations.

4. Discussion

The results show that our person-centred nursing model targeting the needs of patients and family caregivers in the context of allo-HCT is feasible in terms of practicality and acceptability from the perspectives of patients, family caregivers and RNs. Using conversation tools and subsequent conversations facilitates the creation of a structure for the assessment of patient and family caregiver needs, where the individual situation of each patient and family caregiver is seen holistically. The model was largely conducted as intended and the two conversation tools, the ARNC and CSNAT-I, were generally perceived as positive. However, the experiences of using the SNAP conversation tool were less positive in this context and when no needs were identified, the tools and the conversations were experienced as less appropriate. In general, the conversation tools and conversations were perceived as separate parts of the care, not as parts of a complete model. In addition, challenges emerged regarding addressing sensitive topics, following up identified needs and the issue of who is best suited to conduct conversations with family caregivers.

Our findings align with earlier studies that highlight the complex and multifaceted needs and challenges of patients following allo-HCT [

1,

2]. These needs and challenges, which change over time, underscore the importance of person-centred nursing for addressing the diverse physical, psychological, existential and social needs of patients and their family caregivers. The structured nature of our nursing model facilitated discussions that allowed patients and family caregivers to express their concerns and needs, which is consistent with previous research demonstrating the value of person-centred frameworks in enhancing communication and engagement in cancer care [

27].

Structured tools such as the ARNC and SNAP have been validated in previous studies for their effectiveness in identifying patient needs. Our findings confirm their utility in facilitating meaningful conversations, particularly in addressing broad physical, mental and social issues through the ARNC [

17] and self-reported psychological and existential needs through the SNAP [

18].

The positive experience of the ARNC by both patients and RNs in the present study supports the comprehensive goal of person-centred nursing to focus the care on patients’ unique needs and preferences [

15,

16]. Our findings suggest that the sensitive domains included in the ARNC, such as sexuality, appearance and financial issues, may require additional attention in clinical practice. Although these domains were highlighted by the tool, they were often avoided during conversations, likely due to their sensitive nature or RNs feeling unprepared or uncomfortable discussing them, despite their central role in the psychological and social needs described in previous research [

3,

4]. Interesting and worth highlighting is the fact that the “financial, legal, work or housing issues’ domain in the ARNC was not used by any patients, but in the interviews they valued the tool’s ability to prompt self-reflection, particularly regarding employment and financial matters. Targeted training, practical resources and clinical guidelines have been shown to be essential for bridging this gap and can significantly enhance healthcare professionals’ confidence and competence in addressing sensitive topics [

28,

29]. Our nursing model includes a web-based education for healthcare staff about person-centred nursing as well as the nursing model itself with its three tools. However, the RNs expressed a lack of knowledge regarding some domains addressing sensitive topics, showing a need for additional or more detailed education and training.

The SNAP tool was perceived as less useful during the timeframe in which it was used in this study, with both patients and RNs suggesting it might be more effective if introduced later in the care trajectory, such as during the rehabilitation phase. This finding aligns with previous research showing that patients’ needs evolve over time and that careful consideration of when to introduce supportive tools is crucial [

18]. Adjusting the timing of such interventions could enhance their relevance and utility in addressing the evolving challenges faced by patients undergoing allo-HCT. The ARNC and the SNAP were used in close connection after in-patient care, with the ARNC about patients’ problems and the SNAP about patients’ support needs. One assumption is that patients are not used to being asked about their needs and that they already receive sufficient attention from healthcare professionals, therefore the SNAP tool was experienced as superfluous by both patients and RNs.

The findings show positive experiences from both family caregivers and RNs that the CSNAT-I provided family caregivers with an opportunity to articulate their concerns and facilitated collaboration between family caregivers and healthcare professionals, as described in our previous feasibility study of the CSNAT-I in this context [

24]. This also aligns with the key principles of person-centred nursing, such as narratives, partnerships and shared care plans [

15,

16]. Our nursing model recognised and validated family caregivers’ experiences, helping them feel acknowledged and emotionally prepared, which in turn strengthened their ability to provide effective support to the patient. Some family caregivers did not live together with the patient and therefore found certain domains regarding physical care for the patient less relevant. Most family caregivers in the present study were positive (63% positive and 31% positive and negative) about having a CSNAT-I conversation with a RN, while all family caregivers (100%) in our first feasibility study were satisfied about using the CSNAT-I [

24]. This difference is likely due to the fact that in the present study family caregivers had only one conversation before the transplantation, compared to one before and one about 6 weeks after transplantation in the earlier study [

24]. Two conversations over time seem to better provide family caregivers with support and increase their well-being. Improved well-being of family caregivers is beneficial not only for the individual family caregiver, but also reduces family caregivers’ healthcare utilization and costs, benefiting society [

30] The negative experiences regarding using the CSNAT-I conversations in the present study were mainly from the RNs conducting these conversations. The RNs experienced the conversations as emotionally demanding, time-consuming and outside the scope of these HCT coordinators' work assignment. Involving other professionals, such as social workers or psychologists, could help distribute responsibilities while maintaining the model’s holistic approach [

31,

32] and enhance care quality but also support healthcare providers, potentially reducing burnout and improving their sense of efficacy [

33]. The CSNAT-I has demonstrated its capacity to identify and address diverse needs, ensuring that all family caregivers are offered support, regardless of their circumstances and therefore universal implementation of the tool could improve equity in access to family caregiver support.

A key finding was the lack of systematic follow-up on needs identified through the tools and conversations. This highlights a critical gap in integrating the tools into a broader system of education, care planning and follow-up, leading to the risk of identified needs being overlooked and failure to fully achieve the holistic goals of the nursing model. Using the SNAP and CSNAT-I requires training, which the participating nurses received, but apparently it was insufficient, showing the importance of repeated and continuous training. Research has consistently shown that structured follow-up documentation significantly improves continuity of care and patient satisfaction [

34]. Developing clear documentation that assigns accountability for revisiting identified needs could help to ensure that patient and family caregiver concerns are effectively integrated into ongoing care. Clearer forms of follow-up documentation are necessary to improve continuity of care, enhance patient and family caregiver satisfaction and ensure that identified needs, including emotional ones, are systematically addressed in subsequent care interactions.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths that contribute to its robustness and relevance. Based on a sample from two allo-HCT centres, it captures insights from geographically diverse settings, which strengthens the transferability of the findings. One strength of the study is that inclusion was made consecutively with few exceptions, to ensure equity in access to support. The use of validated tools (ARNC, SNAP and CSNAT-I) enabled a structured and systematic approach to identifying and addressing patient and family caregiver needs, while the quantitative and qualitative design allowed for a comprehensive evaluation of the model's feasibility. Furthermore, the involvement of champions in the planning and development of the model (

Box 1) enhanced its clinical relevance and practicality, aligning with participatory research principles that emphasize the value of engaging frontline professionals in intervention design.

Despite these strengths, the study also has significant limitations. Certain patient groups were excluded, such as those with language barriers and cognitive impairments and not all wanted to participate, which may reduce the transferability and generalizability of the findings. One limitation is that characteristics of the participating RNs, such as age and work experience, were not collected and can therefore not be presented. Another limitation was the reliance on RNs’ documentation, which may not fully capture the width of care activities or interventions performed.

4.2. Recommendations for Further Research

To build on the findings of this study, future research should focus on further development of the collaborative creation of a shared care plan, including self-care, nursing interventions and follow-up covering all the needs addressed in the tools included in our nursing model. Longitudinal studies are particularly needed to assess the long-term impact of the model on patient and family caregiver outcomes, especially during the rehabilitation phase when needs evolve significantly. Additionally, expanding the study to include varied demographic and other clinical contexts would strengthen the evidence for its effectiveness and generalizability.

Studies investigating the economic impact of family caregiver inclusion could offer valuable insights into the cost-effectiveness of supporting family caregivers in allo-HCT. Research in this area would provide a stronger foundation for advocating for family caregiver-focused interventions, aligning with the broader goals of improving healthcare efficiency and reducing societal costs.

4.3. Implications for Clinical Practice

The results indicate that RNs who use tools such as the ARNC and CSNAT-I to systematically identify and respond to patient and family caregiver needs can help improve equity in access to support in the context of allo-HCT. However, there are practical challenges involved in using our nursing model. To adequately address the holistic needs identified in the conversations, RNs require further targeted training, access to practical resources and clear clinical guidelines on when to use each tool and avoid simultaneous use, to cope with the holistic needs identified in the conversations and be part of a multidisciplinary team that can address them. Additionally, their role within the multidisciplinary care team must be supported and clarified. In addition, there is a need to enhance the follow-up of assessed and addressed needs by improving continuity of care and developing clearer care plans in a partnership between the RN, the care team, the patient and family caregiver. By addressing these practical challenges, our nursing model has the potential to serve as a sustainable and effective approach to person-centred nursing in allo-HCT, improving outcomes for both patients and family caregivers while supporting healthcare providers in delivering holistic care.

5. Conclusions

This feasibility study highlights a nursing model as a promising framework for delivering person-centred nursing to patients and family caregivers during allo-HCT. The model demonstrated practicality and acceptability across multiple aspects of care, offering a structured approach to addressing the complex needs of this group of patients. However, challenges were identified that require further attention, including staff training and clear clinical guidelines, improved support for addressing sensitive topics and stronger systems for follow-up and resource allocation. By refining the implementation process, providing targeted training for healthcare professionals and addressing structural barriers such as time and resource limitations, our nursing model has the potential to significantly enhance the quality of care and support offered to patients and their families.

With further development, the model offers a promising foundation for sustainable person-centred nursing in the allo-HCT context, aligning with broader goals to improve patient outcomes, support family caregiver well-being and strengthen the overall quality of care delivery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.K., A.O., K.B., C.L.H., and J.W.; methodology, A.M.K., A.O., K.B., C.L.H., and J.W.; software, A.O., and J.W.; validation, A.M.K., C.L.H., and J.W.; formal analysis, A.M.K., L.E., A.O., A.S., K.B., C.L.H., and J.W.; investigation, A.M.K., L.E., A.O., K.B., C.L.H., and J.W.; resources, A.M.K., and J.W.; data curation, A.M.K., A.O., and J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.K., and J.W.; writing—review and editing, A.M.K., and J.W.; visualization, A.M.K., and J.W.; supervision, A.M.K., K.B., C.L.H. and J.W.; project administration, A.M.K., K.B., C.L.H. and J.W.; funding acquisition, A.M.K., K.B., C.L.H. and J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Sjöberg Foundation (Grant number 2021-01-14:7).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden (No. 2022-03688-01).

Informed Consent Statement:

The consent form for participation was distributed to all participants. Informed consent was obtained verbally and in writing from all subjects involved in the study. In the written and oral information, the voluntary nature of participation was emphasised, including the right to withdraw from the study at any time without any impact on patient care or implications for family caregivers or RNs. Furthermore, that data would be treated confidentially and the identity of the participants protected. The researchers in the research group were responsible for the study and had no care relationship with the patients or family caregivers, nor any professional or personal relationships with RNs.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to ethical and legal considerations related to participant confidentiality. However, de-identified datasets may be made available from the corresponding author and principal investigator upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank everyone who agreed to participate in this study as well as the HCT coordinators who helped to recruit them, and Katarina Holmberg who assisted with data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Allo-HCT |

Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation |

| ACRN |

The Assessment of rehabilitation Needs Checklist |

| EBCD |

Experienced Based Co-Design |

| CSNAT-I |

The Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool Intervention |

| GPCC |

Gothenburg Centre for Person-centred Care |

| IPC |

In-patient care |

| MRC |

Medical Research Council |

| OPC |

Out-patient care |

| RN |

Registered Nurse |

| SNAP |

The Support Needs Approach for patients |

References

- Gyurkocza, B.; Rezvani, A.; Storb, R.F. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: the state of the art. Expert Rev Hematol. 2010, 3, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syrjala, K.L.; Martin, P.J.; Lee, S.J. Delivering care to long-term adult survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2012, 30, 3746–3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, L.V.; Holmberg, K.; Lundh Hagelin, C.; Wengström, Y.; Bergkvist, K.; Winterling, J. Symptom Burden and Recovery in the First Year After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Cancer Nurs. 2023, 46, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuba, K. , Esser, P.; Scherwath, A.; Schirmer, L.; Schulz-Kindermann, F.; Dinkel, A., et al. Cancer-and-treatment-specific distress and its impact on posttraumatic stress in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Psychooncology. 2017, 26, 1164–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Lans, M.C.M.; Witkamp, F.E.; Oldenmenger, W.H.; Broers, A.E.C. Five Phases of Recovery and Rehabilitation After Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Qualitative Study. Cancer Nurs. 2019, 42, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergkvist, K.; Larsen, J.; Johansson, U.B.; Mattsson, J.; Fossum, B. Family members' life situation and experiences of different caring organisations during allogeneic haematopoietic stem cells transplantation-A qualitative study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poloméni, A.; Lapusan, S.; Bompoint, C.; Rubio, M.T.; Mohty, M. The impact of allogeneic-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation on patients' and close relatives' quality of life and relationships. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2016, 21, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisch, A.M.; Bergkvist, K.; Alvariza, A.; Årestedt, K.; Winterling, J. Family caregivers' support needs during allo-HSCT-a longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer. 2021, 29, 3347–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, N.; Moons, P.; Taft, C.; Boström, E.; Fors, A. Observable indicators of person-centred care: an interview study with patients, relatives and professionals. BMJ Open. 2022, 12, e059308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Sullivan, A.; Winterling, J.; Malmborg Kisch, A.; Bergkvist, K.; Edvardsson, D.; Wengström, Y. , et al. Healthcare Professionals' Ratings and Views of Person-Centred Care in the Context of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Health Serv Insights. 2025, 18, 11786329241310735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.H.; Sloane, D.; Griffiths, P.; Rafferty, A.M.; Bruyneel, L.; McHugh, M. , et al. Nursing skill mix in European hospitals: cross-sectional study of the association with mortality, patient ratings, and quality of care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017, 26, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öhlén, J.; Sawatzky, R.; Pettersson, M.; Sarenmalm, E.K.; Larsdotter, C.; Smith, F. , et al. Preparedness for colorectal cancer surgery and recovery through a person-centred information and communication intervention - A quasi-experimental longitudinal design. PLoS One. 2019, 14, e0225816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chisholm, C.D.; Weaver, C.S.; Whenmouth, L.F.; Giles, B.; Brizendine, E.J. A comparison of observed versus documented physician assessment and treatment of pain: the physician record does not reflect the reality. Ann Emerg Med. 2008, 52, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Marinis, M.G.; Piredda, M.; Pascarella, M.C.; Vincenzi, B.; Spiga, F.; Tartaglini, D. , et al. 'If it is not recorded, it has not been done!'? consistency between nursing records and observed nursing care in an Italian hospital. J Clin Nurs. 2010, 19, 1544–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, B.; McCance, T.V. Development of a framework for person-centred nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2006, 56, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, I.; Swedberg, K.; Taft, C.; Lindseth, A.; Norberg, A.; Brink, E. , et al. Person-centered care--ready for prime time. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011, 10, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlsson-Nevo, E.; Fogelkvist, M.; Lundqvist, L.O.; Ahlgren, J.; Karlsson, J. Validation of the Assessment of Rehabilitation Needs Checklist in a Swedish cancer population. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2024, 8, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardener, A.C.; Ewing, G.; Mendonca, S.; Farquhar, M. Support Needs Approach for Patients (SNAP) tool: a validation study. BMJ Open. 2019, 9, e032028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, G.; Austin, L.; Diffin, J.; Grande, G. Developing a person-centred approach to carer assessment and support. Br J Community Nurs. 2015, 20, 580–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, G.; Brundle, C.; Payne, S.; Grande, G. The Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) for use in palliative and end-of-life care at home: a validation study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013, 46, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagelin, C.L.; Holm, M.; Axelsson, L.; Rosén, M.; Norell, T.; Godoy, Z.S. , et al. The Support Needs Approach for Patients (SNAP): content validity and response processes from the perspective of patients and nurses in Swedish specialised palliative home care. BMC Palliat Care. 2025, 24, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvariza, A.; Holm, M.; Benkel, I.; Norinder, M.; Ewing, G.; Grande, G. , et al. A person-centred approach in nursing: Validity and reliability of the Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2018, 35, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergkvist, K.; Winterling, J.; Kisch, A.M. Support in the context of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation - The perspectives of family caregivers. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020, 46, 101740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisch, A.M.; Bergkvist, K.; Adalsteinsdóttir, S.; Wendt, C.; Alvariza, A.; Winterling, J. A person-centred intervention remotely targeting family caregivers' support needs in the context of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation-a feasibility study. Support Care Cancer. 2022, 30, 9039–9047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.J.; Kreuter, M.; Spring, B.; Cofta-Woerpel, L.; Linnan, L.; Weiner, D. , et al. How we design feasibility studies. Am J Prev Med. 2009, 36, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venetis, M.K.; Robinson, J.D.; Turkiewicz, K.L.; Allen, M. An evidence base for patient-centered cancer care: a meta-analysis of studies of observed communication between cancer specialists and their patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2009, 77, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, L.F.; Palacios, L.A.G.; Pelger, R.C.M.; Elzevier, H.W. Can the provision of sexual healthcare for oncology patients be improved? A literature review of educational interventions for healthcare professionals. J Cancer Surviv. 2020, 14, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epner, D.E.; Baile, W.F. Difficult conversations: teaching medical oncology trainees communication skills one hour at a time. Acad Med. 2014, 89, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girgis, A.; Lambert, S.; Johnson, C.; Waller, A.; Currow, D. Physical, psychosocial, relationship, and economic burden of caring for people with cancer: a review. J Oncol Pract. 2013, 9, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donetto, S.; Pierri, P.; Tsianakas, V.; Robert, G. Experience based Co-design and Healthcare Improvement: Realizing Participatory design in the Public Sector. The Design Journal. 2015, 18, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M. , et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. Bmj. 2021, 374, n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupo, F.N.; Arnaboldi, P.; Santoro, L.; D'Anna, E.; Beltrami, C.; Mazzoleni, E.M. , et al. The effects of a multimodal training program on burnout syndrome in gynecologic oncology nurses and on the multidisciplinary psychosocial care of gynecologic cancer patients: an Italian experience. Palliat Support Care. 2013, 11, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garment, A.R.; Lee, W.W.; Harris, C.; Phillips-Caesar, E. Development of a structured year-end sign-out program in an outpatient continuity practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2013, 28, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).