Submitted:

06 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background and Preliminaries

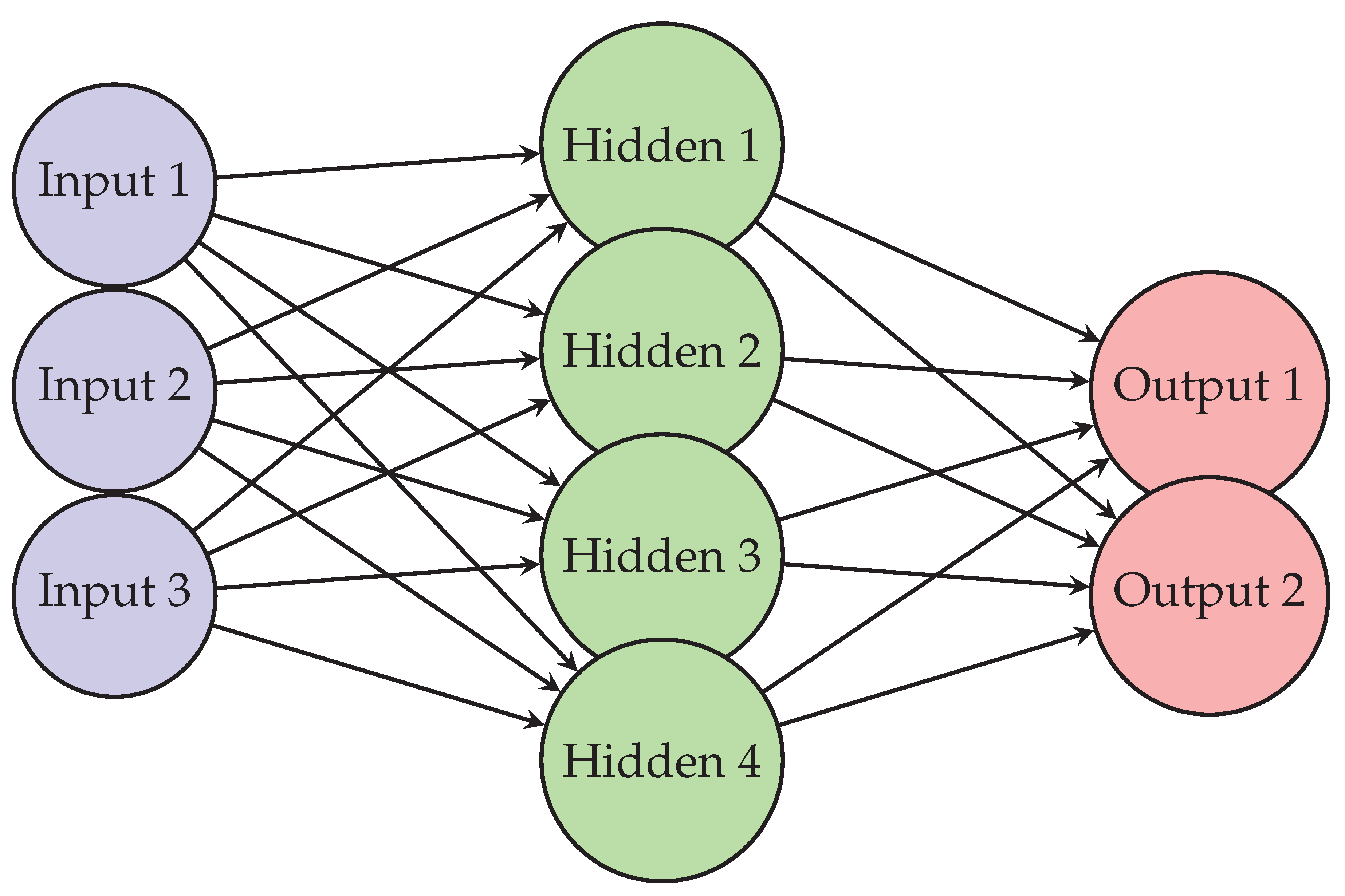

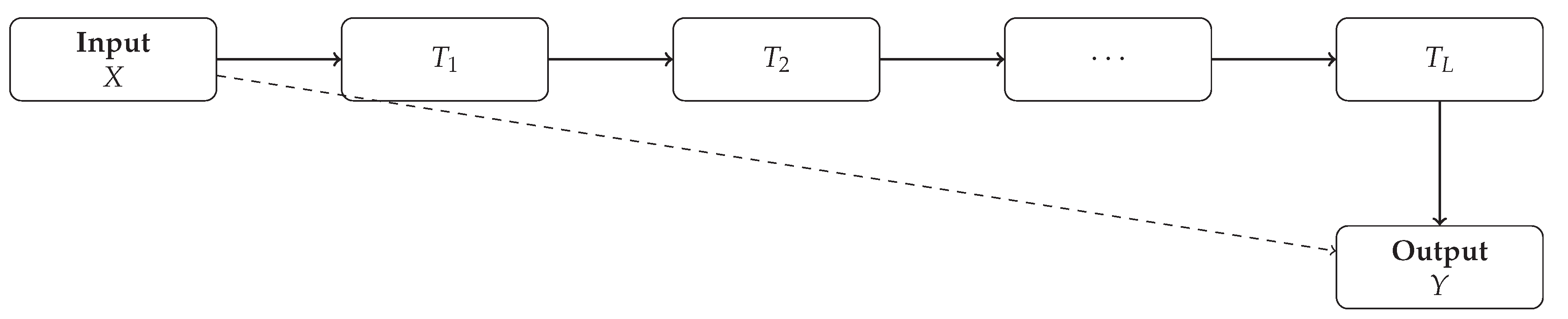

2.1. Deep Neural Networks

2.2. Theoretical Foundations

- -

- Optimization Theory: Analyzes the convergence properties of gradient-based methods, particularly in non-convex settings typical of deep networks.

- -

- Statistical Learning Theory: Provides generalization bounds and capacity measures such as VC-dimension, Rademacher complexity, and uniform stability.

- -

- Approximation Theory: Studies the expressivity of neural networks, including universal approximation theorems and the role of depth and width [10].

- -

- Information Theory: Offers tools for understanding compression, mutual information, and the information bottleneck principle in learning dynamics.

2.3. Motivating the Need for Theory-Guided Training

3. Taxonomy of Theory-Trained Deep Neural Networks

3.1. Optimization-Guided Networks

- -

- Networks trained with provably convergent optimization schemes tailored for non-convex landscapes [15].

- -

- Methods that exploit gradient flow dynamics or adaptive step sizes inspired by theoretical insights.

3.2. Regularization and Generalization-Driven Networks

- -

- Architectures designed to enforce low-complexity function classes.

- -

- Training methods that minimize generalization bounds, such as PAC-Bayes inspired algorithms or margin-based objectives.

3.3. Expressivity-Optimized Networks

3.4. Information-Theoretic Training Paradigms

3.5. Hybrid Approaches

4. Theoretical Foundations of Optimization in Deep Neural Networks

5. Generalization Theory in Deep Neural Networks

6. Information-Theoretic Perspectives on Deep Learning

7. Theory-Informed Training Paradigms

7.1. Optimization-Theoretic Approaches

- -

- Adaptive Gradient Methods with Theoretical Guarantees: Algorithms such as Adam, AdaGrad, and their variants have been analyzed to better understand convergence rates and stability in non-convex settings [37].

- -

- Implicit Regularization through Gradient Descent: Recent works show that gradient-based optimization implicitly biases solutions towards simpler models, leading to better generalization without explicit regularization.

- -

- Optimization in the Overparameterized Regime: Theory-driven approaches leverage the Neural Tangent Kernel (NTK) and mean-field analysis to explain and improve training dynamics when networks are heavily overparameterized [38].

7.2. Regularization and Generalization Techniques

- -

- PAC-Bayesian Training: Training frameworks that optimize PAC-Bayes bounds by incorporating prior distributions over parameters and minimizing expected risk [39].

- -

- Margin-Based Objectives: Encouraging large margins in the feature space to improve robustness and reduce overfitting.

- -

- Norm-Based Regularization: Using weight norms or path norms with provable generalization guarantees [40].

7.3. Architecture and Expressivity-Driven Training

- -

- Depth vs [41]. Width Trade-offs: Architectures designed based on universal approximation theorems to optimize representational capacity.

- -

- Sparse and Structured Networks: Leveraging theoretical sparsity results to build compact, efficient models.

- -

- Activation Function Design: Theoretical insights guide the choice and modification of activation functions to improve gradient flow and expressivity [42].

7.4. Information-Theoretic Training Strategies

- -

- Information Bottleneck Principle: Training objectives that compress intermediate representations while preserving relevant information about the output [43].

- -

- Mutual Information Maximization: Methods that maximize mutual information between inputs and learned features to encourage informative representations [44].

- -

- Entropy-Regularized Training: Introducing entropy constraints to promote robustness and diversity in learned features [45].

8. Applications and Case Studies

8.1. Computer Vision

- -

- Provably Robust Networks: Models trained with adversarial robustness guarantees using optimization-based regularization and certification methods [46].

- -

- Efficient Architectures: Sparse and structured networks informed by approximation theory have reduced model size without sacrificing accuracy [47].

8.2. Natural Language Processing

8.3. Scientific Computing and Physics

- -

- Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs): Networks trained with PDE constraints that leverage approximation theory to solve complex physical systems.

- -

- Uncertainty Quantification: PAC-Bayes-based methods providing principled uncertainty estimates in scientific prediction tasks [50].

8.4. Healthcare and Medical Imaging

- -

- Robust Diagnostic Models: Training with margin-based objectives to improve resistance to data shifts and adversarial attacks [51].

- -

- Data-Efficient Learning: Leveraging theory-inspired regularization to train with limited annotated medical data.

9. Open Challenges and Future Directions

9.1. Bridging Theory and Practice

9.2. Scalability of Theory-Informed Methods

9.3. Understanding Generalization in Overparameterized Regimes

9.4. Robustness and Safety Guarantees

9.5. Interpretable and Explainable Models

9.6. Unified Theoretical Frameworks

9.7. Data Efficiency and Transfer Learning

10. Conclusion

References

- Gupta, A.; Mishra, B. Neuroevolving monotonic PINNs for particle breakage analysis. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Conference on Artificial Intelligence (CAI). IEEE; 2024; pp. 993–996. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Du, J.; Zhang, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, H.; Nie, C. Aerodynamic Performance Improvement of a Highly Loaded Compressor Airfoil with Coanda Jet Flap. Journal of Thermal Science 2022, 31, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, A.M.; Fan, Z. Fixed-time attitude tracking control for rigid spacecraft without angular velocity measurements. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2019, 67, 6795–6805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunning, D.; Aha, D. DARPA’s explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) program. AI magazine 2019, 40, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, G.K.R.; Hemachandra, A.; Ng, S.K.; Low, B.K.H. PINNACLE: PINN Adaptive ColLocation and Experimental points selection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.07662, arXiv:2404.07662 2024.

- Li, Z. Neural operator: Learning maps between function spaces. In Proceedings of the 2021 Fall Western Sectional Meeting. AMS; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Mishra, B.K. Globally optimized dynamic mode decomposition: A first study in particulate systems modelling. Theoretical and Applied Mechanics Letters 2024, p. 100563.

- Bengio, Y.; Bengio, S.; Cloutier, J. Learning a synaptic learning rule; Citeseer, 1990.

- Tartakovsky, A.M.; Marrero, C.O.; Perdikaris, P.; Tartakovsky, G.D.; Barajas-Solano, D. Physics-informed deep neural networks for learning parameters and constitutive relationships in subsurface flow problems. Water Resources Research 2020, 56, e2019WR026731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, S.; He, D.; Wang, L. Is L2 Physics-Informed Loss Always Suitable for Training Physics-Informed Neural Network? arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.02016 2022. arXiv:2206.02016 2022.

- Schmidhuber, J. Evolutionary principles in self-referential learning, or on learning how to learn: the meta-meta-... hook. PhD thesis, Technische Universität München, 1987.

- arXiv:cs.LG/1803.02999].

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Duan, J.; Karniadakis, G.E. Learning and meta-learning of stochastic advection–diffusion–reaction systems from sparse measurements. European Journal of Applied Mathematics 2021, 32, 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharazmi, E.; Cai, M.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, G.; Karniadakis, G.E. Identifiability and predictability of integer-and fractional-order epidemiological models using physics-informed neural networks. Nature Computational Science 2021, 1, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psaros, A.F.; Kawaguchi, K.; Karniadakis, G.E. Meta-learning PINN loss functions. Journal of computational physics 2022, 458, 111121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wolff, T.; Lincopi, H.C.; Martí, L.; Sanchez-Pi, N. Mopinns: an evolutionary multi-objective approach to physics-informed neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference Companion, 2022, pp.

- Ataei, M.; Salehipour, H. XLB: A differentiable massively parallel lattice Boltzmann library in Python. Computer Physics Communications 2024, 300, 109187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Herrera, C.; Grandits, T.; Plank, G.; Perdikaris, P.; Sahli Costabal, F.; Pezzuto, S. Physics-informed neural networks to learn cardiac fiber orientation from multiple electroanatomical maps. Engineering with Computers 2022, 38, 3957–3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karniadakis, G.E.; Kevrekidis, I.G.; Lu, L.; Perdikaris, P.; Wang, S.; Yang, L. Physics-informed machine learning. Nature Reviews Physics 2021, 3, 422–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Liu, Z.; Kudyshev, Z.A.; Boltasseva, A.; Cai, W.; Liu, Y. Deep learning for the design of photonic structures. Nature Photonics 2021, 15, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Wan, X.; Yang, C. DAS-PINNs: A deep adaptive sampling method for solving high-dimensional partial differential equations. Journal of Computational Physics 2023, 476, 111868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, J.; Caruana, R.; Mitchell, T.; Pratt, L.Y.; Silver, D.L.; Thrun, S. Learning to learn: Knowledge consolidation and transfer in inductive systems. In Proceedings of the NIPS Workshop, 1995., http://plato. acadiau. ca/courses/comp/dsilver/NIPS95_LTL/transfer. workshop.

- Willard, J.; Jia, X.; Xu, S.; Steinbach, M.; Kumar, V. Integrating scientific knowledge with machine learning for engineering and environmental systems. ACM Computing Surveys 2022, 55, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, C.; Abbeel, P.; Levine, S. Model-agnostic meta-learning for fast adaptation of deep networks. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2017; pp. 1126–1135. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, S.J.; Yang, Q. A survey on transfer learning. IEEE Transactions on knowledge and data engineering 2009, 22, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, S.; Di Cola, V.S.; Giampaolo, F.; Rozza, G.; Raissi, M.; Piccialli, F. Scientific machine learning through physics–informed neural networks: Where we are and what’s next. Journal of Scientific Computing 2022, 92, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Ma, L.; Jin, Y.; Du, W.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, H. A survey on knee-oriented multiobjective evolutionary optimization. IEEE transactions on evolutionary computation 2022, 26, 1452–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Karniadakis, G.E. L-HYDRA: Multi-head physics-informed neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.02152, arXiv:2301.02152 2023.

- Viana, F.A.; Subramaniyan, A.K. A survey of Bayesian calibration and physics-informed neural networks in scientific modeling. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2021, 28, 3801–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrin, R.; Bullwinkel, B.; Mattheakis, M.; Protopapas, P. Transfer learning with physics-informed neural networks for efficient simulation of branched flows. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.00214, arXiv:2211.00214 2022.

- Li, Z.; Kovachki, N.; Azizzadenesheli, K.; Liu, B.; Bhattacharya, K.; Stuart, A.; Anandkumar, A. Fourier neural operator for parametric partial differential equations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.08895, arXiv:2010.08895 2020.

- Kho, J.; Koh, W.; Wong, J.C.; Chiu, P.H.; Ooi, C.C. Design of turing systems with physics-informed neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI). IEEE; 2022; pp. 1180–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Négiar, G.; Mahoney, M.W.; Krishnapriyan, A.S. Learning differentiable solvers for systems with hard constraints. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.08675, arXiv:2207.08675 2022.

- Yang, S.; Tian, Y.; He, C.; Zhang, X.; Tan, K.C.; Jin, Y. A gradient-guided evolutionary approach to training deep neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2021, 33, 4861–4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Cheung, K.C.; Ng, M.K. Svd-pinns: Transfer learning of physics-informed neural networks via singular value decomposition. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI). IEEE; 2022; pp. 1443–1450. [Google Scholar]

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G.E. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. Journal of Computational Physics 2019, 378, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Mao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yin, M.; Karniadakis, G.E. Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) for fluid mechanics: A review. Acta Mechanica Sinica 2021, 37, 1727–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Beatson, A.; Oktay, D.; McGreivy, N.; Adams, R.P. Meta-pde: Learning to solve pdes quickly without a mesh. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.01604, arXiv:2211.01604 2022.

- Pratt, L.Y.; Mostow, J.; Kamm, C.A. Direct transfer of learned information among neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ninth National conference on Artificial intelligence-Volume 2, 1991, pp. 584–589.

- Bonfanti, A.; Bruno, G.; Cipriani, C. The Challenges of the Nonlinear Regime for Physics-Informed Neural Networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.03864, arXiv:2402.03864 2024.

- Liu, Y.; Liu, W.; Yan, X.; Guo, S.; Zhang, C.a. Adaptive transfer learning for PINN. Journal of Computational Physics 2023, 490, 112291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Perdikaris, P. Long-time integration of parametric evolution equations with physics-informed deeponets. Journal of Computational Physics 2023, 475, 111855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, N.; Wong, J.C.; Ooi, C.C.; Gupta, A.; Chiu, P.H.; Ong, Y.S. Neuroevolution of physics-informed neural nets: benchmark problems and comparative results. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Companion Conference on Genetic and Evolutionary Computation, 2023, pp. 2144–2151.

- Lu, L.; Meng, X.; Mao, Z.; Karniadakis, G.E. DeepXDE: A deep learning library for solving differential equations. SIAM review 2021, 63, 208–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, W.; Lee, K.; Rim, D.; Park, N. Hypernetwork-based meta-learning for low-rank physics-informed neural networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Yu, X.; Perdikaris, P. When and why PINNs fail to train: A neural tangent kernel perspective. Journal of Computational Physics 2022, 449, 110768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudabadbozchelou, M.; Jamali, S. Rheology-informed neural networks (RhINNs) for forward and inverse metamodelling of complex fluids. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Avila Belbute-Peres, F.; Chen, Y.f.; Sha, F. HyperPINN: Learning parameterized differential equations with physics-informed hypernetworks. In Proceedings of the The symbiosis of deep learning and differential equations; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Ye, Z.; Liu, H.; Ji, S.; Wang, Z.; Yang, K.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Chu, H.; Yu, F.; et al. Meta-auto-decoder for solving parametric partial differential equations. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 23426–23438. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Ong, Y.S.; Yao, S.; Liu, H.; Luo, J. Choose appropriate subproblems for collaborative modeling in expensive multiobjective optimization. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 2021, 53, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, P.W.; Hamrick, J.B.; Bapst, V.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, A.; Zambaldi, V.; Malinowski, M.; Tacchetti, A.; Raposo, D.; Santoro, A.; Faulkner, R.; et al. Relational inductive biases, deep learning, and graph networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.01261, arXiv:1806.01261 2018.

- Garbet, X.; Idomura, Y.; Villard, L.; Watanabe, T. Gyrokinetic simulations of turbulent transport. Nuclear Fusion 2010, 50, 043002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Rueden, L.; Mayer, S.; Beckh, K.; Georgiev, B.; Giesselbach, S.; Heese, R.; Kirsch, B.; Pfrommer, J.; Pick, A.; Ramamurthy, R.; et al. Informed Machine Learning–A taxonomy and survey of integrating prior knowledge into learning systems. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2021, 35, 614–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, T.; Wang, H.; Núñez, A.; Dollevoet, R. Transfer learning for improved generalizability in causal physics-informed neural networks for beam simulations. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2024, 133, 108085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Wang, Z.; Fuest, F.; Jeon, Y.J.; Gray, C.; Karniadakis, G.E. Flow over an espresso cup: inferring 3-D velocity and pressure fields from tomographic background oriented Schlieren via physics-informed neural networks. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2021, 915, A102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandel, N.; Weinmann, M.; Neidlin, M.; Klein, R. Spline-pinn: Approaching pdes without data using fast, physics-informed hermite-spline cnns. in Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2022, Vol. 36, pp. 8529–8538.

- Chiu, P.H.; Wong, J.C.; Ooi, C.; Dao, M.H.; Ong, Y.S. CAN-PINN: A fast physics-informed neural network based on coupled-automatic–numerical differentiation method. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2022, 395, 114909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Wang, H.; Chugh, T.; Guo, D.; Miettinen, K. Data-driven evolutionary optimization: An overview and case studies. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2018, 23, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prantikos, K.; Chatzidakis, S.; Tsoukalas, L.H.; Heifetz, A. Physics-informed neural network with transfer learning (TL-PINN) based on domain similarity measure for prediction of nuclear reactor transients. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 16840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zniyed, Y.; Nguyen, T.P.; et al. Enhanced network compression through tensor decompositions and pruning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Roscher, R.; Bohn, B.; Duarte, M.F.; Garcke, J. Explainable machine learning for scientific insights and discoveries. Ieee Access 2020, 8, 42200–42216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).