1. Introduction

Lawmaking petitions allow citizens to request new legislation, amendments to existing laws, or advocate for policy reforms, ensuring that the public’s voice is represented in legislative processes and decision-making. These petitions address critical domains such as economic development, healthcare, education, transportation systems, and sustainable urban growth, aligning governmental actions with societal priorities [

1,

2].

The petition process in parliamentary settings generally involves four stages: submission, admissibility assessment, consideration, and closure. Petitions may be either handwritten or electronic, and they can be submitted in physical or digital form, depending on the legislative framework of the respective jurisdiction. Despite the growing adoption of electronic petition systems, handwritten lawmaking petitions submitted in physical form using standardized templates (hereafter written petitions) remain a central element of the petition process in many European parliaments and continue to serve as the primary method in various regions worldwide [

3].

For a written petition to be deemed admissible, it must contain a valid handwritten signature from each signatory and meet the minimum number of signatories required by law, typically ranging from tens of thousands to several hundred thousand, depending on jurisdictional and demographic factors. A valid handwritten signature includes both a personal identifier (hereafter ID), which is a unique alphanumeric code assigned to each individual, and the personal signature.

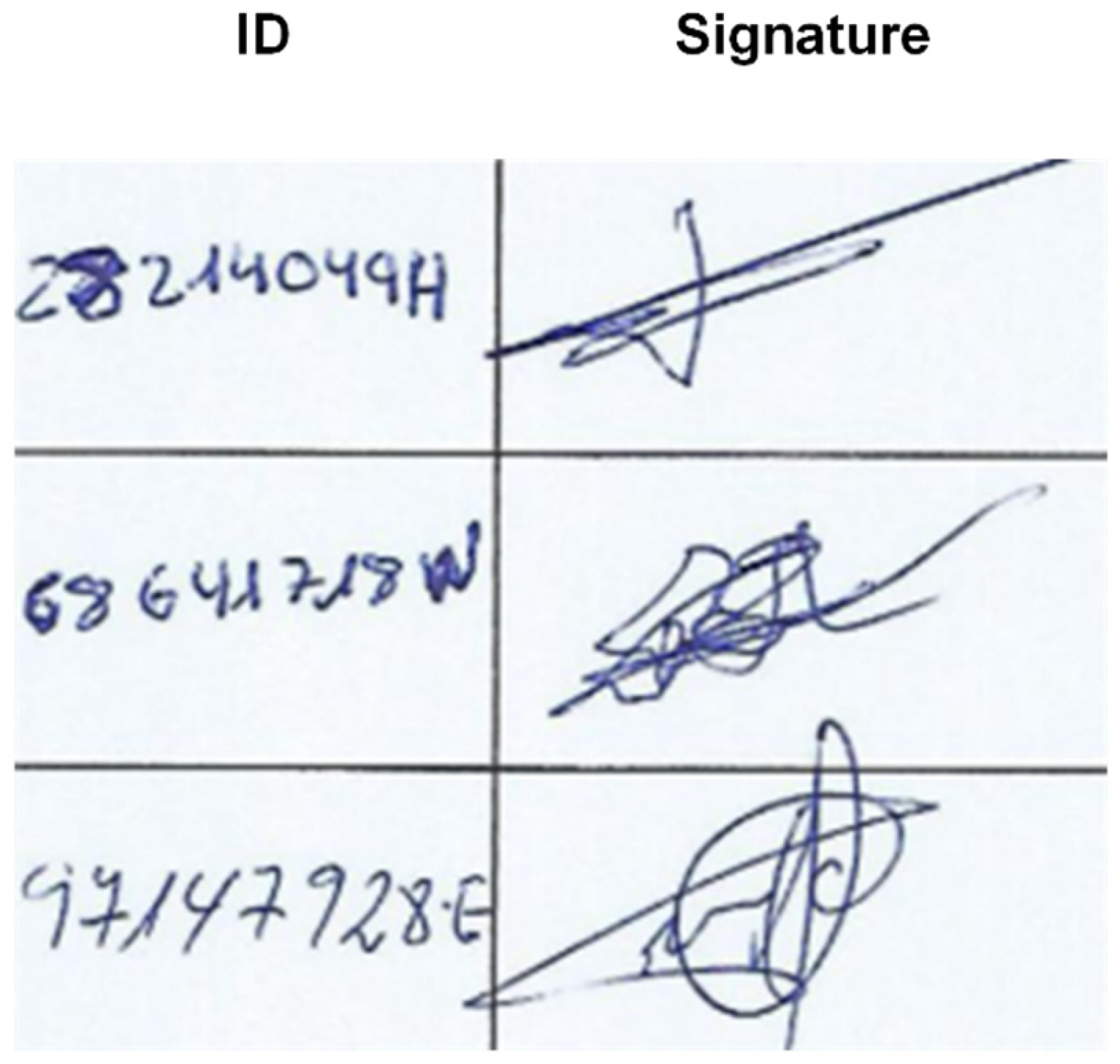

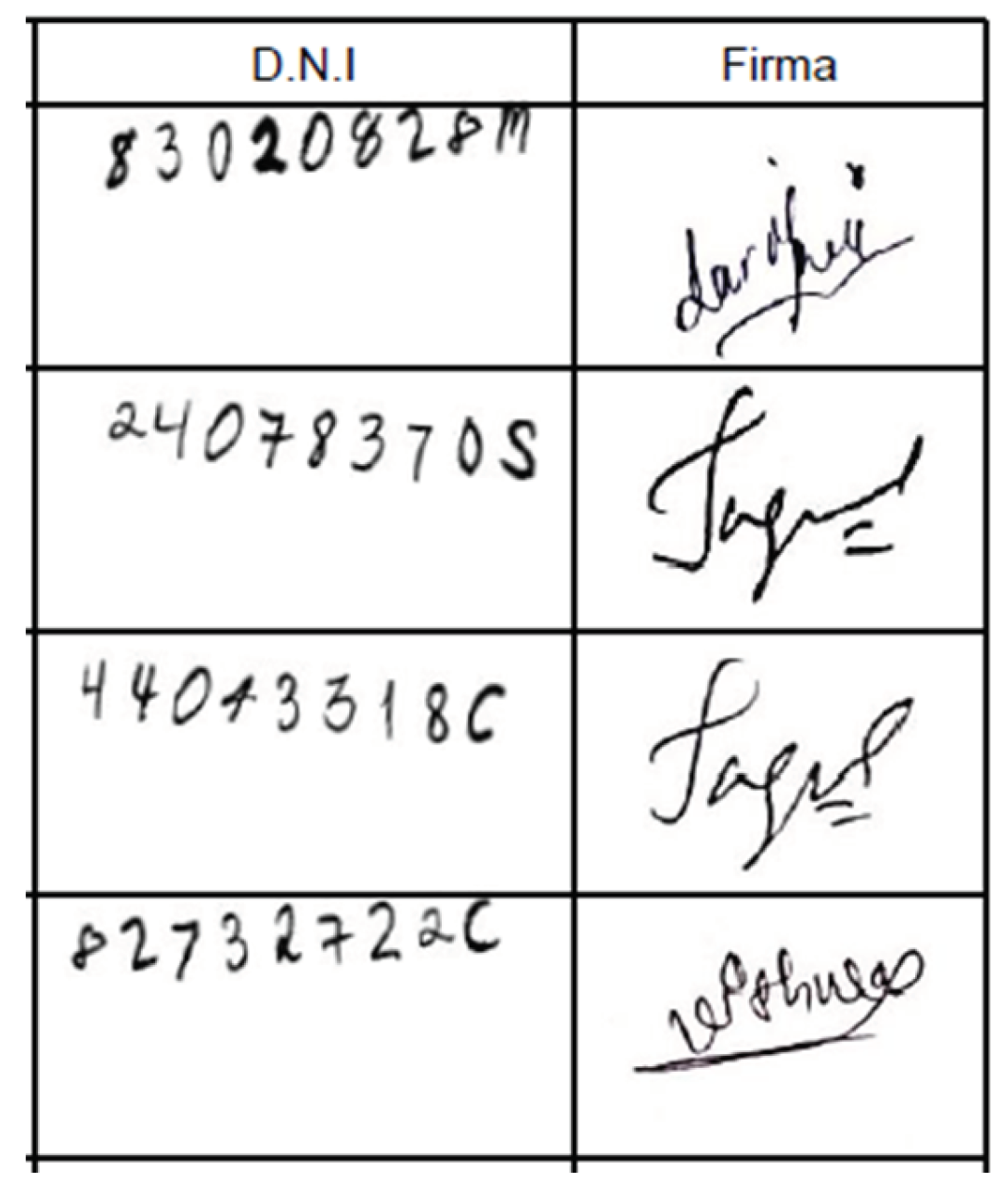

Figure 1 presents an example of a simulated written petition containing three human-performed handwritten signatures that do not include real personal data, as might be submitted to the Parliament of the Canary Islands, Spain. In the example, each ID associated with each signatory comprises nine characters: eight digits followed by one letter, consistent with the format defined by the Spanish Home Office [

5].

Handwritten signature verification (HSV) is a critical process for determining the admissibility of a written petition. It entails the detection and recognition of each signatory’s ID, the validation of its authenticity, and the confirmation of a corresponding signature. Traditionally, this process has been carried out manually, making it labor-intensive, time-consuming, and prone to human error, given the high volume of signatories and the variability in handwriting styles. Furthermore, verification inaccuracies, such as the failure to identify a valid ID, can lead to the rejection of a petition if the legally required threshold of valid signatories is not met.

To address these issues, systems like Optical Character Recognition (OCR), a challenging research topic in computer vision (CV) and natural language processing (NLP), provide a viable solution for converting scanned handwritten documents into machine-readable formats [

6] and automating the recognition of handwritten IDs while confirming the presence of the corresponding signature.

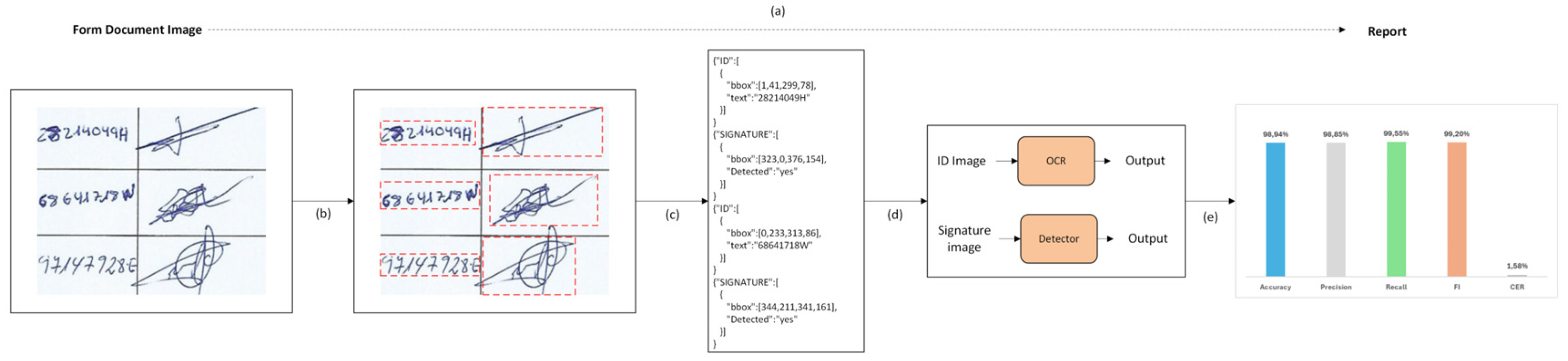

Figure 2 presents the architecture of the OCR pipeline designed for the HSV task applied to written petitions. These petitions follow a form-based format, and the pipeline consists of four key modules:

Scanning: Physical documents containing the written petitions from signatories are digitized into images.

Text detection: The image is segmented into meaningful components. Each component is identified by a bounding box, one enclosing the signatory’s handwritten ID and another enclosing the corresponding signature.

Text recognition: Each ID is recognized by the recognizer component, while each signature is detected by the signature detector.

Results: The validity of each recognized ID is verified, ensuring that it is paired with a signature. A report is generated based on the results using predefined metrics.

Traditional OCR pipelines primarily rely on machine learning (ML) approaches, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [

7] for handwritten text detection and recognition tasks. While CNNs have proven effective in image classification, object detection, and printed text recognition, they face limitations when applied to handwritten text. These limitations include the need for a separate language model, such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [

8], to convert visual features into text sequences. This additional step can introduce errors due to misalignment between the CNN output and the language model predictions, making the system challenging to scale for handwriting styles [

9]. Consequently, such models are unsuitable for the HSV problem addressed in this paper, where verification mistakes can invalidate valid petitions.

The emergence of transformer-based models offers a new approach to be explored. Their ability to capture long-range dependencies through self-attention mechanisms makes them particularly well-suited for sequence-based tasks like text detection and handwriting recognition. Despite recent advances in the application of transformers to these tasks, several challenges persist in the context addressed by this paper. These include: investigate their adaptability to previously unseen data, substantial data requirements, as their effective performance depends on large amounts of annotated data, that in this context are scarce and costly to obtain; difficulties in fine-tuning the model for the specific domain, which requires retraining the model on labeled datasets; the need to comply with privacy laws such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [

4], since datasets contain sensitive personal information like IDs and signatures; and high computational demands, which can hinder deployment in resource-constrained environments such as parliamentary settings.

This paper introduces a proof of concept (PoC) OCR system based on a transformer-centric solution to address the challenges of HSV applied to written petitions. The proposed system not only automates the HSV process but also tackles data scarcity by developing privacy-compliant synthetic datasets that simulate handwriting styles. Developed and evaluated in collaboration with the Canary Islands Parliament, the system complies with institutional legal and technical constraints and demonstrates significant improvements in accuracy compared to traditional CRNN-based frameworks. The main contributions are summarized as follows:

Transformer-based approach: Introducing a method for HSV applied to written petitions using exclusively transformer-based models, which enhances accuracy compared to CRNN-based frameworks.

Privacy-compliant synthetic datasets: Developing synthetic datasets of varying sizes that simulate handwriting styles while adhering to GDPR. This approach addresses data scarcity and evaluates the effectiveness of model training.

Viability of transformer-based models for real-world problems: Investigating the transferability and adaptability of transformer models for detecting and recognizing IDs applied to written petitions.

Comprehensive Evaluation: Assessing performance using a verification, validation, and testing (VVT) framework with dual metrics: (1) ML-based ID-level accuracy for evaluating the system’s ability to correctly recognize IDs as whole entities and (2) NLP-based character-level accuracy for fine-grained text recognition errors.

Parliamentary application: Implementing and evaluating the system within a real-world parliamentary setting, where computational resources are limited, demonstrating its practical feasibility and effectiveness for the automation of a manual process.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 discusses related work;

Section 3 describes the methodology;

Section 4 details the specific methods and materials used, with a focus on a transformer-centric approach;

Section 5 presents the results;

Section 6 discusses the findings; and

Section 7 provides concluding remarks.

2. Related Work

2.1. Optical Character Recognition

Traditional OCR systems typically consist of two main modules: a text detection module and a text recognition module. Text detection aims to localize all text blocks within the text image and is generally framed as an object detection problem. In contrast, text recognition involves converting the detected visual features into natural language tokens, transforming them into digital text. This task is often approached as an encoder-decoder problem, where the encoder processes the detected text to extract meaningful features and creates a compact representation of the visual information. This representation is then passed to the decoder, which sequentially generates the corresponding textual output.

Due to the advances of deep learning, approaches to detecting and recognizing handwritten text can be classified into two main categories: (1) CRNN-based OCR models and (2) Transformer-based OCR models.

In the following two subsections, we will describe how both models address text detection and recognition tasks.

2.1.1. Text Detection

The conventional techniques for text detection using CNN-based approaches include Faster R-CNN [

10], Mask R-CNN [

11], EAST [

12], CRAFT [

13], and YOLO [

14]. These models are trainable end-to-end, meaning they can directly learn to predict text features from raw image inputs without requiring hand-crated features or separate steps like manual feature extraction. However, they differ in several aspects: (1) output granularity: some models, such as Faster R-CNN, YOLO, and EAST, predict bounding boxes for detected text regions, localizing the text within the image. Other models, like Mask R-CNN, predict more complex shapes such as masks, which provide pixel-level segmentation of the text regions, offering a more detailed representation; and (2) speed vs. accuracy trade-offs: models like YOLO and EAST are designed to be particularly fast and efficient, making them suitable for real-time applications. They strike a balance between speed and detection accuracy. In contrast, Mask R-CNN and Faster R-CNN are more accurate in text detection but are computationally more expensive, making them better suited for applications where precision is a higher priority than speed.

Text detection in form-based documents involves a preliminary step, such as identifying where tables are located (a.k.a. table detection) and subsequently inferring the table structure from the document by identifying the individual pieces that make up a table, like rows, columns, and cells (a.k.a. table structure recognition) [

15]. While earlier approaches were based on general-purpose architectures such as Faster R-CNN [

16], current methods often rely on training transformer-based object detection models, such as DETR [

17], for both table detection and structure recognition. Currently, these transformer-based models have shown better results compared to Faster R-CNN [

18].

2.1.2. Text Recognition

Early methods treated the problem of recognizing text as a general image classification, focused on CNN end-to-end OCR models [

19,

20]. Other approaches utilized a CNN-based encoder for image understanding, capturing spatial hierarchies and local patterns, while an RNN-based decoder was employed for text generation, to handle sequences and predict the next token based on the previously generated ones. While CNNs have proven highly effective in image classification, object detection, and recognizing printed text, and have been foundational in the development of OCR systems, they face different limitations when applied to handwritten text detection and recognition. These limitations include integration issues, ensuring that outputs from CNNs are properly aligned with inputs to RNNs, which adds complexity to the architectural design. Additionally, error propagation is a concern; since RNNs process data sequentially, any error in the CNN output (e.g., misclassifying a character) can propagate through the RNN and lead to incorrect text predictions. CNNs also tend to be inefficient with irregular text, particularly when it is rotated or curved.

Recent progress in deep learning models has led to significant improvements by leveraging transformer-based models, a deep learning architecture introduced by Vaswani et al. [

21] and originally developed for NLP tasks. The key innovation of transformers is the self-attention mechanism, which enables the model to weigh the importance of different words (or tokens) in a sequence, regardless of their distance from each other. This allows the model to attend to different parts of the sequence simultaneously and capture long-range dependencies. This contrasts with earlier sequence models like RNNs and LSTMs, which process tokens in order and struggle to capture long-range dependencies.

Transformer-based models can be trained on massive amounts of text data to learn general representations, resulting in pre-trained language models (PLMs) such as BERT, GPT, and T5. These PLMs can then be fine-tuned with labeled data to perform specific tasks. Transformer-based models have also been adapted for vision tasks, such as Vision Transformers (ViTs), which divide an image into fixed-size patches, treat each patch as a token (similar to words in NLP), and process them using self-attention mechanisms. This approach enables ViTs to model global relationships between different parts of an image more effectively than CNNs, particularly for tasks that require understanding long-range dependencies [

22].

Recent work suggests that combining transformer-based models for image and language processing can enhance feature representation by replacing the CNN backbone with image transformers and using language transformers instead of RNNs for more robust textual modeling. TrOCR exemplifies this approach [

23], a transformer-based OCR model that employs architectures similar to ViT and DeiT [

24] as its encoder and RoBERTa (a pre-trained BERT-style model) [

25] as its decoder. The model is initially pre-trained on a large-scale dataset of synthetically generated data for image understanding and language modeling and can then be fine-tuned with labeled datasets for specific tasks. The model focuses solely on the text recognition task, excluding the text detection phase.

While this model has been fine-tuned for various domain-specific applications, such as recognizing historical documents in archives [

26], interpreting medical prescriptions [

9], and processing scanned receipts in financial settings [

27], adapting it to the HSV task for lawmaking petitions introduces new challenges.

Therefore, our objective is to propose an OCR pipeline that relies exclusively on a transformer-based approach suitable for deployment in real-world legal settings. First, we explore the integration of the TrOCR model with an upstream transformer model responsible for locating IDs and corresponding signatures without relying on complex pre-processing steps. Second, we address the scarcity of available annotated datasets for model fine-tuning. In our target environment, the collection and annotation of large datasets is both time-consuming and legally sensitive due to privacy concerns. Nevertheless, such data is critical for accommodating the variability of handwriting styles. We thus investigate whether the TrOCR model can perform effectively using synthetic datasets of varying sizes generated automatically, without human annotation. Third, we assess the model’s performance in a resource-constrained setting without access to a Graphics Processing Unit (GPU), which is typically required for transformer-based architectures.

By addressing these challenges, we aim to assess the adaptability and viability of the TrOCR model for real-world HSV tasks in the legal domain, under constraints such as limited computational resources, reliance on synthetic data for fine-tuning, and the need for integration with other transformer-based models.

3. Methodology

The proposed OCR system for the HSV task applied to written petitions was designed, developed, and tested collaboratively by researchers from the University of La Laguna (ULL) and the Chief Information Officer (CIO) of the Parliament of the Canary Islands. The methodology follows the established principles of scientific research in information systems design [

28] and comprises five stages: (1) problem identification and motivation, (2) definition of solution objectives, (3) system design and development, (4) evaluation, and (5) demonstration.

In the first stage, the problem and its objectives were analyzed within a real-world context, highlighting the need for an efficient and automated system capable of performing HSV with minimal manual intervention.

The system design phase centered on the formalization of a modular processing pipeline composed exclusively of transformer-based models. This pipeline architecture was implemented during the development stage, ensuring seamless integration between components and facilitating both automation and scalability.

Subsequently, the system was evaluated through a verification, validation, and testing (VVT) framework [

29]. The demonstration activity included presenting the system to the CIO of the Parliament of the Canary Islands as part of the testing phase, to assess its practical applicability in an operational environment.

The following sections provide a detailed account of each stage.

Section 3.1 and 3.2 cover the first two stages of the methodology.

Section 4 describes the proposed OCR pipeline method, while

Section 5 reports the evaluation results, and

Section 6 discusses the main findings within the VVT framework.

3.1. Problem Identification and Motivation

In the Parliament of the Canary Islands, verifying the voter status of signatories for citizen-proposed bills is a legal requirement currently carried out manually [

30]. This process is time-consuming and prone to error, and becomes increasingly unsustainable given the high volume of signatories per petition. This challenge is exemplified by the most recent popular initiative bill submitted in March 2023 (reference 10L/PPLP-0036), concerning volcanoes in the Canary Islands, which required the verification of over 22,000 citizens (

https://www.parcan.es/iniciativas/tramites.py?id_iniciativa=10L/PPLP-0036).

3.2. Solution Objectives

The proposed OCR system is designed to automate the verification of handwritten IDs and their corresponding signatures. The primary objectives of the system are as follows:

Automatic and Efficient Verification: Accurately identify and validate handwritten IDs, ensuring correct pairing with their corresponding signatures.

Performance Evaluation: Generate detailed reports using predefined metrics to summarize verification outcomes, including the number of successfully verified IDs and those that failed verification.

Data Privacy Compliance: Ensure compliance with the GDPR by employing synthetic datasets that simulate handwritten petition forms.

The system must process petition forms in which each page is treated as an image instance containing handwritten IDs and signatures. The output must include the successfully verified IDs and those flagged for manual review.

To ensure the system aligns with both procedural and technical requirements of the Parliament, the following constraints must be met:

Number of Signatories: According to parliamentary regulations, popular legislative initiatives must include at least 15,000 signatures, or signatures from 50% of the electorate in an island constituency if the initiative pertains solely to that region.

Document Format: Each page must follow a predefined tabular layout designed to record handwritten IDs and signatures. These documents are provided in PDF format and processed as images, simulating scanned, human-completed forms to ensure compatibility with OCR models.

ID Format: Each ID must conform to the official format specified by the Spanish Home Office [

5], consisting of eight numeric digits followed by a single alphabetic character (see

Figure 1).

Signature Requirement: Each signatory must provide a handwritten signature alongside the ID number.

Transformer-Based Architecture: The system must rely exclusively on transformer-based models designed to be efficient and viable for use in resource-constrained environments typical of parliamentary institutions.

Dataset Preparation: Two distinct datasets must be dynamically generated to support system development and evaluation: (1) the ID Dataset, which simulates handwriting styles for IDs to facilitate TrOCR model fine-tuning and (2) the Form Document (FD) Dataset, representing the written petition and containing a minimum of 15,000 representative samples of handwritten IDs and signatures. This dataset is designed for system evaluation while ensuring compliance with GDPR. Both datasets are generated on demand based on user-defined parameters, such as the number of IDs for the ID dataset and the number of pages and signatories per page for the FD dataset. This approach enables flexible dataset creation tailored to different evaluation scenarios.

4. Materials and Methods

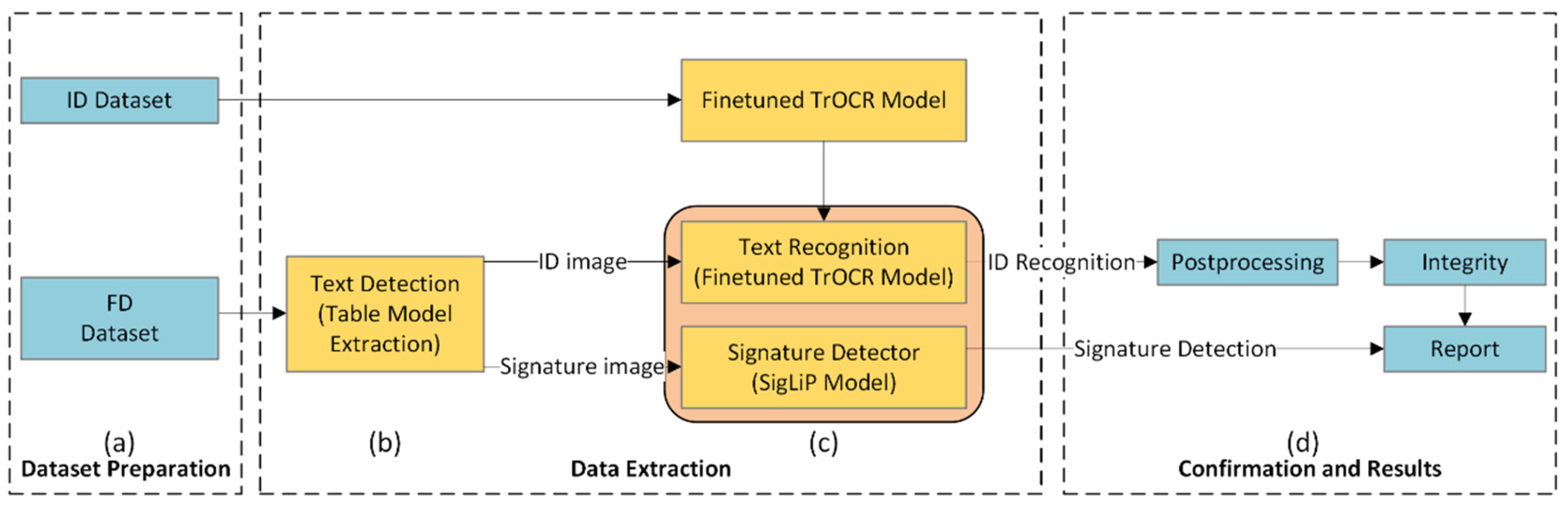

The proposed OCR system is structured as a modular pipeline designed to support the automation and scalability required for processing large volumes of written petitions. As illustrated in

Figure 3, the pipeline comprises three main modules:

Dataset preparation: Described in

Section 4.1, this module performs two key functions: (1) generating the ID dataset and (2) generating the FD dataset.

Data extraction: This core module consists of three submodules: text detection, text recognition, and signature detection. The text detection submodule identifies the bounding boxes corresponding to handwritten IDs and signatures within the table image and the coordinates of table rows and columns. The text recognition submodule extracts ID values from the detected regions, while the signature detection submodule verifies whether a handwritten signature accompanies each detected ID.

Confirmation and Results: Once an ID is recognized, it is validated against the official format specified by the Spanish Home Office. Finally, the system generates a report summarizing the results based on predefined performance metrics.

4.1. Dataset Preparation

A key requirement for developing and testing the proposed transformer-based OCR system is access to datasets containing annotated handwritten IDs and corresponding signatures. However, obtaining such datasets poses significant challenges, as they involve personal data and are subject to strict restrictions under the GDPR. Moreover, the dataset must include diverse and well-annotated samples to support effective ID recognition. Additionally, while the TrOCR model has been pre-trained on printed text and fine-tuned on English handwritten text, it has not been specifically fine-tuned for handwritten IDs.

To address these challenges and reduce the time and effort required to prepare such data, we propose a method for automatically generating synthetic annotated datasets of varying sizes. This approach ensures the diversity needed for fine-tuning the recognition model and evaluating its performance, all while remaining GDPR-compliant. Our method for creating datasets involves extracting and merging annotated handwritten characters, including digits and letters, from the most relevant sources, as well as applying data augmentation techniques to further enhance their diversity and variety.

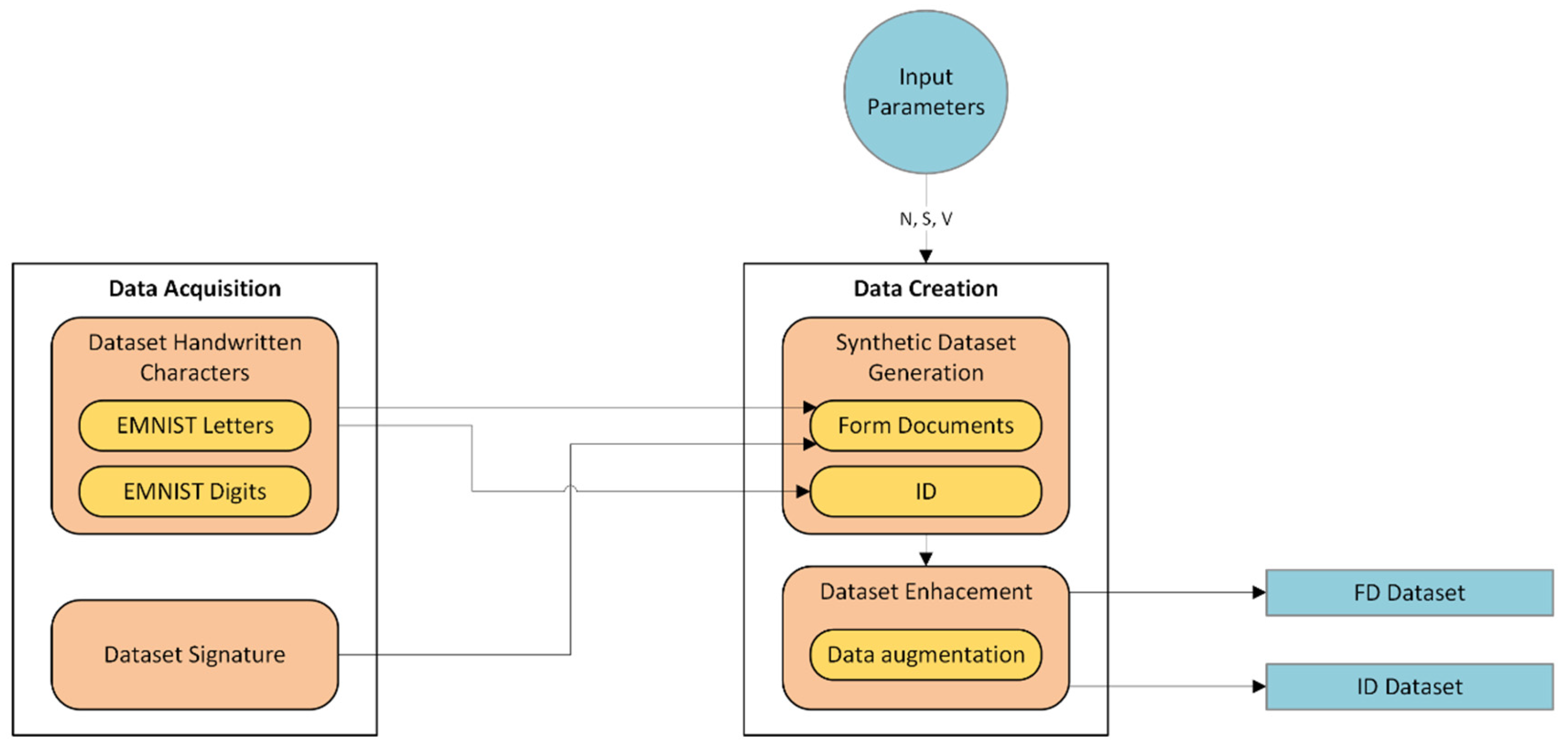

The dataset preparation module involves two key stages, as illustrated in

Figure 4:

Data Acquisition: This stage involves identifying and collecting handwritten characters and signatures.

Data Creation: In this stage, the synthetic dataset generation process and the dataset enhancement process are applied to create two datasets: the ID Dataset and the FD Dataset. The ID Dataset is intended for fine-tuning the TrOCR model and requires, as an input parameter, the number of handwritten IDs to be generated (denoted as V). The FD Dataset simulates written petition documents and takes as input the number of pages (denoted as N) and the number of signatories per page (denoted as S), each containing both handwritten IDs and signatures. During the synthetic dataset generation process, ID images are automatically produced according to the specified parameters V and N, using unique combinations of eight digits followed by one letter, following the format established by the Spanish Home Office. In the FD Dataset, each generated ID image is paired with a corresponding synthetic signature image. Subsequently, the dataset enhancement process is applied. This involves data augmentation techniques aimed at increasing variability in handwritten styles across both datasets.

The components of each stage in the dataset preparation module are detailed below.

4.1.1. Handwritten Character Acquisition

The aim focuses on identifying the most appropriate datasets containing handwritten digits and letters to support the generation of synthetic ID images. The EMNIST dataset was selected due to its suitability as a benchmark for handwritten character recognition tasks [

31]. Derived from the NIST Special Database 19 (SD19) [

32], EMNIST includes over 800,000 manually verified and labeled samples contributed by nearly 3,700 writers [

33], converted into a standardized 28×28-pixel image format. This ensures a diverse and representative collection of handwritten characters, which is essential for constructing a robust dataset that captures natural variation in handwriting styles.

The EMNIST dataset provides six predefined subsets: ByClass, ByMerge, Letters, Digits, and MNIST. Some subsets, such as ByClass and ByMerge, exhibit class imbalance and are thus less suitable for model fine-tuning. Therefore, the Letters and Digits splits were selected due to their balanced class distributions. The Letters split comprises 26 alphabetic classes (a–z), combining upper and lowercase letters into a single set with a total of 145,600 samples. The Digits split includes 10 numeric classes (0–9), totaling 280,000 samples. These characteristics make EMNIST an ideal source for generating synthetic data in both the ID and FD datasets.

4.1.2. Handwritten Signature Acquisition

The objective is to identify and collect handwritten signature image samples to accompany each ID in the FD dataset. For this purpose, a publicly available dataset by Suresh et al. [

34], developed for handwritten signature recognition using deep learning, was selected. The dataset contains 2,500 signature images from 25 unique individuals, with 100 signatures per individual, each provided in a 224×224-pixel image format.

4.1.3. Synthetic Dataset Generation

The synthetic dataset generation process, the first step of the data creation phase, produces two distinct datasets: the ID Dataset and the FD Dataset. The FD Dataset is generated in PDF format, with each page containing a table image consisting of S rows and two columns, one for handwritten IDs and one for corresponding handwritten signatures, representing the specified number of signatories per page.

In accordance with the format defined by the Spanish Home Office, each ID consists of a unique combination of eight digits followed by one letter. To simulate this structure, ID images are constructed by concatenating randomly sampled digits from the EMNIST Digits dataset (280,000 samples; see

Section 4.1.1) and a letter from the EMNIST Letters dataset (145,600 samples). These components are combined to form a complete ID image that adheres to the official Spanish ID generation algorithm. For the ID Dataset, the process takes as input the number of IDs to be generated (denoted as

V) and outputs a dataset in image format, with each entry representing a complete ID image.

4.1.4. Synthetic Dataset Enhancement

The synthetic dataset enhancement process, the second step in the data creation phase, aims to increase the variability and realism of the generated ID images by applying data augmentation techniques. These techniques produce more diverse and representative handwritten samples for each ID generated in the previous step (see

Section 4.1.3). Four image transformations are applied to both the FD and ID datasets: random rotations (ranging from −5° to 5°), Gaussian blurring, image downscaling, and upscaling.

Algorithm 1 presents the algorithm used to generate the FD dataset. This algorithm creates a specified number of pages (N), each containing a table image with S rows corresponding to signatories. Each signatory is assigned a synthetic ID composed of eight digits and a control letter, and is paired with a corresponding handwritten signature.

| |

Input: number of pages N, number of signers S

Output: PDF form document dataset FD

|

1:

2:

3:

4:

5:

6:

7:

8:

9:

10:

11:

12:

13:

14:

15: |

Initialize FD ← {}

for n = 1 to N do

Initialize T[S]← {} // Signatories Table

for s = 1 to S do

Initialize ID ← {} // Identification Number Image

Initialize F ← {} // Signature Image

ID ← Image of eight handwritten numbers randomly generated from EMNIST Digits

ID ← Concat a control letter generated from EMNIST Letters, following the Spanish ID algorithm

ID ← Apply random image transformations: rotations (from -5 to 5 degrees), Gaussian blurring, image downscaling, and upscaling

F ← Randomly generated handwritten signature

T[S] = [ID, F]

end for

FD[n] = T

end for

Return FD

|

The algorithm for generating the ID dataset follows a similar approach but only requires the number of ID images to be generated as input.

Figure 5 shows representative examples of ID and signature images extracted from the FD dataset.

4.2. Data Extraction

This module comprises three submodules, as illustrated in

Figure 3: text detection, text recognition, and signature detection. Each submodule is implemented using a transformer-based model. The following subsections describe each submodule.

4.2.1. Text Detection

The text detection submodule identifies the locations of handwritten IDs and signatures within the FD dataset. Its primary objective is to localize all ID and signature regions on each page image.

Since each page in the FD dataset follows a table structure, with rows corresponding to signatories and two columns representing ID and signature entries (see

Section 4.1), this submodule takes each page image as input and outputs the coordinates of the bounding boxes that enclose the relevant regions. This step is essential, as the subsequent submodule requires the extracted region containing the sequence of tokens that represent the ID to be recognized.

To perform this task, a transformer-based object detection method is employed. Specifically, the Table Transformer model proposed by Smock et al. [

18] is used. This model, trained on the Pub

Tables 1M dataset, which comprises one million annotated tables, detects and interprets the structure of tables in document images. Based on this structure, the bounding boxes for each ID and signature are computed by iterating through the rows of each table.

For every bounding box identified, two image segments are extracted from the input image: one containing the ID and the other the corresponding signature. These segments are then forwarded to the subsequent submodules for ID recognition and signature verification.

4.2.2. Text Recognition

The text recognition submodule is implemented as an end-to-end text recognition transformer model, based on the TrOCR architecture proposed by Li et al. [

23]. TrOCR employs an image transformer as the encoder and a text transformer as the decoder. The authors present three model variants: small, base, and large, containing 62 million, 334 million, and 558 million parameters, respectively. This range allows a trade-off between computational efficiency and representational capacity, enhancing the model’s ability to capture fine-grained image details. While the large model achieves the highest performance, it is also the most computationally demanding.

The pretrained TrOCR models were initially trained on large-scale synthetic datasets, comprising hundreds of millions of printed text line images. These models were subsequently fine-tuned on the IAM Handwritten dataset, which is widely used for handwritten text recognition, and the SROIE dataset, which contains over one thousand scanned receipt images.

For this work, we adopt the large, fine-tuned version of the TrOCR model, initially trained on the IAM Handwritten dataset, to develop the text recognition submodule. This model integrates a BeiT transformer [

35] as the encoder and RoBERTa [

25] as the decoder, enabling image-to-text sequence processing. To adapt the model for recognizing handwritten IDs, we further fine-tuned it using our ID datasets. As a result, in the fine-tuned model, the encoder processes patches from ID images to extract relevant features, while the decoder generates the corresponding text sequence for the ID.

4.2.3. Signature Detection

Signature detection within the predefined bounding boxes is approached as a zero-shot image classification task. To accomplish this, we adapted the SigLIP (Sigmoid Loss for Language-Image Pre-training) transformer-based model, originally designed for vision and language tasks, to the problem of signature detection. SigLIP processes individual image-text pairs directly without requiring a global normalization based on pairwise similarities [

36]. Consequently, our task is framed as a binary classification problem in which images are classified as either “signature,” indicating the presence of a signature within the bounding box, or “no signature,” indicating its absence.

4.3. Confirmation and Results

This module is responsible for verifying the validity of each ID recognized by the data extraction module. It ensures the accuracy and compliance of the recognized data through a structured process. The module consists of three submodules, which are described in detail below:

4.3.1. Post-Processing

The decoder of the TrOCR model may produce incorrect characters at certain positions within the text sequence that do not conform to the structural definition of an ID (a unique combination of eight digits followed by one letter). Typical errors include the introduction of non-alphanumeric characters such as punctuation marks (e.g., commas, colons, dashes, periods), unexpected whitespace, substitution of uppercase letters for lowercase letters, and the misclassification of numbers as letters or vice versa. To address these issues, the post-processing submodule refines the ID text sequences through the following steps:

Removal of non-alphanumeric characters (step 1): All non-alphanumeric characters, including whitespace and punctuation marks, are filtered out.

Capitalization correction (step 2): All lowercase letters are converted to their uppercase equivalents.

Substitution of visually similar letters with numbers (step 3): When a digit is expected in the first eight positions but a letter is detected, it is replaced by the most visually similar number based on the following mapping: (“A” → “4”, “B” → “3”, “G” → “6”, “I” → “1”, “O” → “0”, “P” → “9”, “S” → “5”, “T” → “7”, and “Z” →”2”). Additionally, certain non-alphanumeric characters are replaced with similar digits: (“/”, “(“, “)”, “!” → “1”, and “&” → “8”).

Substitution of visually similar numbers with letters (step 4): When a letter is expected in the last position of the text sequence but a digit is detected, it is replaced by the most visually similar letter according to the following mapping: (“0” → “O”, “7” → “T”, “2” → “Z”, “3” → “B”, “4” → “A”, “5” → “S”, and “6” → “G”, and “9” → “P”).

4.3.2. Integrity

Following the corrections performed by the postprocessing submodule, the integrity submodule is responsible for ensuring the accuracy and integrity of each ID. This process encompasses several key functionalities aimed at verifying the conformity of the IDs to their structural and algorithmic requirements:

Alignment with the Structural Definition of an ID: This functionality verifies that each ID adheres to the structural format, consisting of a unique combination of eight numerical digits followed by one alphabetic character.

Control Character Validation: This step ensures that the ID’s control character is defined according to the algorithm established for Spanish IDs, maintaining the integrity of the identification process.

Anomaly Detection: This process identifies potential issues, such as duplicate IDs, to ensure that all IDs are unique.

4.3.3. Report

The report submodule is responsible for generating summaries of the validation outcomes. Its primary functions include:

Error Reporting: This component lists all IDs that failed validation.

Performance Metrics: This component evaluates the accuracy and reliability of the text recognition submodule used for ID recognition. By employing both ML and NPL metrics, it assesses the effectiveness of the recognition process. These metrics contribute to a comprehensive evaluation of the system’s overall performance.

5. Results

The transformer-based OCR system was evaluated as a prototype for potential real-world implementation within the Parliament of the Canary Islands. The VVT framework [

29] assessed the system’s performance and practical utility. The experimental setup and the results of the verification and validation process used in the evaluation are described below.

5.1. Experimental Setup

5.1.1. Environment

The system was implemented using Python 3.13, with Pytorch as the deep learning framework, and the large version of the pre-trained TrOCR model fine-tuned on the IAM handwritten dataset [

23]. It was further fine-tuned on our custom ID datasets to enhance the model’s ability to recognize handwritten IDs, as detailed in

Section 4.1.

All training and evaluation tasks were conducted on a system equipped with an Intel Core™ i7-10700 CPU (2.9 GHz) and 32 GB of RAM, aiming to assess the system’s performance and feasibility in resource-constrained parliamentary environments. For comparison purposes, the baseline model was evaluated on a more powerful setup comprising an Intel Core™ i7-11800H CPU (2.3 GHz), an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3050 GPU, and 32 GB of RAM.

5.1.2. Datasets

Two synthetic datasets were generated, as described in

Section 4.1:

ID Dataset: Five fine-tuning sets of varying sizes (V = 100, 1,000, 2,000, 3,000, and 4,000 samples) were created, each containing annotated ID samples to evaluate the TrOCR model’s robustness as the training set size increases. Training was conducted for three epochs using a learning rate of 5.0 × 10⁻⁶.

FD Dataset: This dataset simulates the Parliament’s real-world operational procedures (see

Section 3.2) and serves as a test set to evaluate the performance of three transformer-based models: the Table Transformer for text detection, TrOCR for ID recognition, and SigLIP for signature detection. In accordance with procedural requirements, popular legislative initiatives must include a minimum of 15,000 signatures. To reflect this, the dataset was generated using input parameters of

N = 1,500 pages and

S = 10 signatories per page, yielding 15,000 synthetic signatory records. This version is referred to as FDD-S. Additionally, a smaller subset was created to evaluate TrOCR’s performance on authentic handwriting samples. This subset consists of

N = 50 pages with

S = 10 signatories per page, resulting in 500 real-world signatory records. Referred to as FDD-R, it is used to assess the model’s generalization capabilities to real-world data. Importantly, both the 15,000 synthetic samples and the 500 real-world samples were reserved exclusively for testing and were not used during any stage of the fine-tuning process.

5.1.3. Metrics

The performance was evaluated from both NLP and ML perspectives:

Precision: measures the ratio of correctly predicted positive characters to the total predicted positives. It quantifies how many of the ID’s characters predicted by the model are correct:

Where TP (true positives) corresponds to the number of correctly recognized characters and FP (false positives) to the number of incorrectly recognized characters.

Accuracy: represents the ratio of correctly predicted characters to the total number of characters in the actual ID:

Recall: measures the ratio of correctly predicted characters to the total number of actual positive characters. It focuses on how many of the real positive instances were correctly identified by the model:

Where FN (false negatives) represents the number of unrecognized characters.

F1-Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall:

Character Error Rate (CER): measures the number of character-level errors, including insertions, deletions, and substitutions required to transform the model’s prediction into the correct ID:

Where S corresponds to the number of substitutions, D to the number of deletions, I to the number of insertions, and N to the total number of characters in the actual ID.

Precision: measures the proportion of correctly recognized IDs among all IDs predicted as correct:

Where TP (true positives) corresponds to the number of IDs correctly identified as positive and FP (false positives) to the number of IDs incorrectly identified as positive.

Accuracy: represents the proportion of all correct predictions (positive and negative) relative to the total predictions:

Where TN (true negatives) refers to the number of IDs correctly identified as negative, while FN (false negatives) represents the number of valid IDs that the model incorrectly predicts as not matching the ground truth.

Recall: measures the proportion of correctly recognized IDs out of all IDs that should have been recognized:

F1-Score: is the harmonic mean of precision and recall:

5.1.4. Baseline Model

We use the CRNN model [

37] as the baseline model, as it has traditionally been the state of the art for text recognition. The CRNN model consists of convolutional layers for image feature extraction, recurrent layers for sequence modeling and final frame label prediction, and a transcription layer to convert frame predictions into the final label sequence.

5.2. Verification

The verification process evaluates whether the prototype meets the requirements, objectives, and dataset preparation criteria defined in

Section 3.

Requirements Verification: All specified requirements were fully implemented and validated, including the number of signatories, the form document template, the ID format, the inclusion of handwritten signatures, and the transformer-based processing approach. This validation was carried out by researchers of ULL and the CIO of the Parliament of the Canary Islands, ensuring compliance with the predefined specifications.

Objectives Verification: All project objectives were successfully achieved. The PoC delivered an automated solution for HSV applied to written petitions. It also generated synthetic datasets of various sizes to fine-tune the TrOCR model and evaluate the system’s performance, while adhering to data protection requirements under the GDPR. User involvement was minimal, limited to entering parameters N (number of pages), S (number of signatories per page), and V (dataset size).

Dataset Preparation: The dataset preparation process followed the method outlined in

Section 4.1. Synthetic data generation techniques produced realistic representations of handwritten signatures, ensuring strict compliance with data privacy regulations.

5.3. Validation

The validation process assessed the performance of the data extraction module, focusing on three submodules: text detection, text recognition, and signature detection.

5.3.1. Text Detection Results

The Table Transformer model [

18] was evaluated to ensure the accurate calculation of bounding box coordinates for each ID and signature across all rows of the table structure on every page of the FD dataset. The model successfully detected the corresponding bounding boxes for all pages processed.

5.3.2. Text Recognition Results

To evaluate the performance of the TrOCR model [

23] in recognizing IDs, we conducted six distinct experiments. These evaluations incorporated both NLP and ML metrics. The experiments were designed to analyze the impact of varying fine-tuning dataset sizes and post-processing configurations. All experiments were carried out using both the FFD-S (synthetic dataset) and FDD-R (real-world dataset).

To investigate how the size of the fine-tuning dataset influences model performance, we generated five datasets of sizes

V = 100, 1,000, 2,000, 3,000, and 4,000. Two post-processing configurations were evaluated: (1) applying only steps 1 and 2, and (2) applying the full set of post-processing steps, as described in

Section 4.3.1. Based on these factors, the following experiments were carried out:

Original Model (No Fine-tuning, No Post-processing): The first experiment evaluated the original model without any fine-tuning or post-processing.

Original Model (No Fine-tuning, Post-processing Applied): This experiment assessed the original model without fine-tuning but with post-processing. Two variations were tested: (1) applying only steps 1 and 2, and (2) applying all four post-processing steps.

Fine-tuned Model (No Post-processing): In this experiment, the model was fine-tuned on custom ID datasets of varying sizes (V=100 to 4,000) without applying any post-processing steps.

Fine-tuned Model (Post-processing Applied with Steps 1 and 2): This configuration combined fine-tuning with post-processing steps 1 and 2 to assess their joint effect.

Fine-tuned Model (Post-processing Applied with Steps 1, 2, 3, and 4): The model was fine-tuned on datasets of varying sizes and subjected to all four post-processing steps.

Comparison with Baseline Model: The best-performing configuration from the above experiments was compared against the baseline model to evaluate performance improvements.

Table 1 presents the results of experiments 1 and 2. The key findings are as follows: the results reveal a performance gap between synthetic and real handwriting data, with lower accuracy and F1 scores observed on FFD-R across all evaluation metrics. For both datasets, the application of post-processing techniques proves essential. Without post-processing (NPS), performance remains limited, particularly under the ML-based evaluation, as this requires the correct recognition of complete ID strings as unified entities. Applying basic post-processing (PS1) substantially improves performance, especially for the synthetic dataset, where the F1 score increases from 9.71% to 64.72%. The most comprehensive post-processing configuration (PS2) yields the highest results across both datasets, achieving an F1 score of 81.51% on FFD-S and 58.22% on FFD-R. These findings underscore the effectiveness of post-processing in mitigating character-level errors, compensating for the absence of fine-tuning.

Table 2 summarizes the results of experiment 3, which involved fine-tuning the model on progressively larger datasets (

V=100 to 4,000). Both NLP and ML evaluation metrics show incremental improvements as the dataset size increases, particularly up to

V = 3,000. Results reported in

Table 3 and

Table 4 further indicate that post-processing has no effect when applied after fine-tuning, suggesting that fine-tuning itself is the principal factor contributing to performance improvements. For instance, the NLP-based accuracy on the FDD-S dataset improved from 97.74% at

V = 100 to 98.91% at

V = 3,000. However, the outcomes remained consistent regardless of whether post-processing was applied. Similar patterns were observed in the ML-based metrics across all configurations, reinforcing the conclusion that fine-tuning is the dominant contributor to the observed gains.

Table 5 presents a comparative evaluation of the CRNN and fine-tuned TrOCR models on both FDD-S and real FDD-R datasets using NLP and ML evaluation metrics. The results demonstrate a performance gap between the two models across all metrics and datasets. On the synthetic dataset (FDD-S), the CRNN model achieved a performance, with an NLP F1 score of 81.21% and a Character Error Rate (CER) of 29.76%. However, its performance on ML metrics was notably poor, achieving an F1 score of only 1.59%. In contrast, the TrOCR model fine-tuned on 3,000 samples reached an NLP F1 score of 99.39% with a CER of just 1.09%, and demonstrated a superior ML F1 score of 95.30%. The same trend holds for the real handwriting dataset (FDD-R). For this dataset, CRNN obtained an NLP F1 score of 66.22% and an ML F1 score of 0.76%, indicating limited generalization to authentic handwritten input. Meanwhile, TrOCR fine-tuned on 3,000 samples outperformed CRNN by a wide margin, achieving an NLP F1 score of 84.71% and an ML F1 score of 88.96%.

These results indicate that the transformer-based TrOCR model, when fine-tuned with a sufficiently large synthetic dataset, outperforms the traditional CRNN architecture in both synthetic and real-world scenarios.

5.3.3. Signature Detection Results

The SigLIP transformer-based model [

36] was evaluated as a binary classification task to confirm the presence of signatures in conjunction with the IDs detected. For all pages processed from the FD dataset, the model achieved perfect accuracy and precision, with 100% in both metrics. Consequently, the model successfully predicted both the presence and absence of signatures across all instances.

6. Discussion

The key findings obtained from experiments one to six for text recognition are as follows:

Post-processing: Post-processing steps improved both metrics when the model was not fine-tuned, as the TrOCR decoder introduced incorrect characters at certain positions within the text sequence that did not conform to the structural definition of an ID (a unique combination of eight digits followed by one letter). Typical errors included the insertion of non-alphanumeric characters (e.g., commas, colons, dashes, periods), unexpected whitespace, substitution of uppercase with lowercase letters, and misclassification of numbers as letters or vice versa. Applying all post-processing steps reduced character-level errors and improved ID-level accuracy, delivering the best results under non-fine-tuned conditions. However, the effects of post-processing were negligible once the model was fine-tuned, indicating that fine-tuning is essential for achieving optimal performance.

Fine-tuning: Fine-tuning on custom datasets, particularly larger datasets, significantly boosted the TrOCR model’s performance, especially for synthetic data (FDD-S). Synthetic data benefits more significantly from fine-tuning than real-world data. The results indicate the importance of scaling training datasets to achieve better outcomes.

Real-world Data Challenges: While the results for both metrics from real-world data were promising for the Parliament of the Canary Islands, with an accuracy of 84.31% for the NLP metric and 80.04% for the ML metric, it was observed that the TrOCR model performed better on synthetic data (FDD-S) compared to real-world data (FDD-R) across all experiments. Despite this, the results demonstrate the effectiveness of using only synthetic data for training.

CRNN vs TrOCR: The CRNN model yielded lower performance compared to TrOCR, suggesting that TrOCR’s architecture is better suited for both synthetic and real-world data. Specifically, TrOCR outperformed CRNN across all evaluation metrics, from both the NLP and ML perspectives.

Overall, the experiments suggest that the TrOCR model performs best when fine-tuned on a sufficiently large, synthetic dataset, with no improvements observed from post-processing. The CRNN model lags behind TrOCR, especially in handling real-world data.

To ensure a comprehensive evaluation, the system was tested by the CIO of the Parliament of the Canary Islands. These trials focused on performance metrics (outlined in

Section 5.3) and compliance with the requirements and objectives specified in

Section 3. The CIO’s assessment revealed the following insights:

Effectiveness of the Transformer-Based Approach: The transformer-based architecture demonstrated effectiveness in automating handwritten signature verification. As detailed in

Section 5.3, the system achieved the target accuracy levels, fulfilling the objectives related to performance. Error rates, including false positives, false negatives, and misclassifications, were evaluated from both NLP and ML perspectives and were found to be comparable to human-level performance. While the system performed slightly better on synthetic data than on real handwriting samples, the results remain satisfactory, especially considering that real-world data were not available for training due to GDPR constraints. The model’s ability to generalize to authentic inputs supports the viability of this approach in practical settings.

Efficiency and Minimal Manual Intervention: The HSV task has traditionally been performed manually, making it labor-intensive, time-consuming, and prone to human error. The PoC demonstrated its potential to improve efficiency by automating the process, thereby reducing the need for manual intervention.

Scalability and Compliance: The system dynamically generated synthetic datasets, ensuring scalability while adhering to GDPR requirements. This capability allows the solution to accommodate varying scenarios without compromising data protection standards.

Feasibility of the Solution: The testing phase demonstrated that the proposed system is feasible for practical deployment, even when developed using CPU-based hardware. The solution leverages transformer-based models and performs for its intended tasks, such as text detection, text recognition, and signature detection. Despite the absence of GPU hardware, the system proved practical for deployment in parliamentary institutions with limited computational resources. Additionally, the use of synthetic datasets eliminates reliance on sensitive real-world data, addressing privacy concerns while supporting the fine-tuning of transformer models.

Hardware Limitations: While the solution was successfully implemented using general-purpose CPU-based equipment, the evaluation underscored the need for advanced hardware with GPU or TPU capabilities to fully leverage the potential of transformer-based models. Although the system operates efficiently for its current objectives, fine-tuning processes require significant computational power, which could be improved with GPU acceleration to enhance processing speed.

Knowledge Gaps in Public Institutions: The CIO noted that public institutions lack expertise in transformer-based models. This highlights the need for collaboration between universities, research centers, and public institutions to drive the adoption of AI-driven innovations.

Adaptation to new programming paradigms: Public administration has traditionally relied on computing paradigms focused on algorithm design and programming, where the primary objective is to create new algorithms to solve problems directly. The shift from traditional computing to fine-tuning transformer models introduces a data-centric approach. Traditional software development focuses on deterministic, rule-based algorithms and uses general-purpose tools, whereas fine-tuning transformer models requires specialized frameworks like PyTorch, along with significant computational resources (e.g., GPUs, TPUs). This new paradigm emphasizes iterative experimentation. Unlike traditional development, fine-tuning involves adapting pre-trained models to the specific task and addressing ethical concerns like algorithmic bias.

In summary, the testing process confirmed the system’s ability to meet its intended objectives and validated its readiness for real-world implementation. Addressing hardware limitations and bridging institutional knowledge gaps will be essential for scaling the solution and fostering broader adoption of transformer-based models in legislative and other public sector applications.

7. Conclusions

Transformer-based models represent the state of the art in NLP and CV. However, their adaptability to new, previously unseen data, real-world data scarcity, and high computational demands pose significant challenges when developing viable solutions within institutional settings. This paper presented a proof of concept OCR system to address the HSV problem in a parliamentary context. Developed and tested in collaboration with the Parliament of the Canary Islands, the proposed system meets procedural and technical requirements, demonstrating the feasibility of automating this task through a transformer-centric approach. It addresses challenges such as handwriting variability and compliance with data privacy regulations while evaluating the practicality of deployment in resource-constrained parliamentary environments. The key findings and contributions are as follows:

Transformer-Based Adaptation: This work shows how transformer-based models, specifically the Table Extraction Model, TrOCR, and SigLIP, can be effectively integrated and adapted for HSV. The proposed system outperforms conventional CRNN frameworks in both synthetic and real-world scenarios.

Privacy-Compliant Data Generation: To overcome limitations on accessing available real handwritten data, synthetic datasets were generated to simulate realistic handwriting styles. These datasets comply with data protection regulations and enabled effective model training.

Performance Evaluation: System performance was assessed using a VVT framework and ML/NLP-based metrics. Results demonstrated strong performance when training and testing on synthetic data, achieving 98.91% character-level accuracy and 90.48% ID-level accuracy. When tested on real data, trained only on synthetic samples, the system achieved 84.31% and 80.04% in character-level and ID-level accuracy, respectively. These findings validate the effectiveness of fine-tuning TrOCR on privacy-compliant datasets for ID recognition under real-world variability.

Operational Feasibility: The results confirm that it is possible to perform the HSV task with a transformer-centric approach with low computational costs, facilitating its adoption in real-life institutional settings. CIO feedback emphasized limited AI expertise in public institutions, underlining the need for stronger collaboration between academia and government.

Institutional Impact: According to the CIO, automating the HSV task for written petitions offers substantial advantages. It streamlines workflows, reduces verification time, and allows legislative bodies to manage a greater volume of petitions efficiently.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.SN. and I.M.H.; methodology, E.S.N, and I.M.H.; software, E.SN. and I.M.H.; validation, E.SN. and I.M.H.; formal analysis, E.SN. and I.M.H.; investigation, E.SN. and I.M.H; resources, E.SN. and I.M.H.; data curation, E.SN. and I.M.H; writing E.S.N.; visualization, E.S.N.; supervision, E.S.N.; project administration, E.S.N.; funding acquisition, E.S.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain through the projects PID2023-151073NB-I00, TED2021-131019B-I00, and PDC2022-134013-I00.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CIO |

Chief Information Officer |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| CV |

Computer Vision |

| ID |

Personal Identifier |

| FD |

Form Document |

| FFD-R |

Real-World Form Document Dataset |

| FFD-S |

Synthetic Form Document Dataset |

| GDPR |

General Data Protection Regulation |

| HSV |

Handwritten Signature Verification |

| NLP |

Natural Language Processing |

| OCR |

Optical Character Recognition |

| PLM |

Pre-trained language model |

| PoC |

Proof of concept |

| RNN |

Recurrent Neural Network |

| VVT |

Verification, Validation, and Testing |

| ULL |

Universidad de La Laguna |

References

- Smith, G. Democratic Innovations: Designing Institutions for Citizen Participation. In Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Rosenberger S, Seisl B, Stadlmair J, Dalpra, E. What Are Petitions Good for? Institutional Design and Democratic Functions. Parliamentary Affairs, 2022, 25(1):217-237. [CrossRef]

- Tibúrcio, T. Rules, procedures and practices of the right to petition parliaments. A fundamental right to a process. European Parliament, Study commissioned by the Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs, 2023. Brussels: European Union.

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). Official Journal of the European Union, OJL 119 4.5.2016, pp. 1–88.

- Spanish Home Office (2005). Basic Regulatory Regulations. Royal Decree 1553/2005, of December 23, regulating the issuance of the national identity document. https://www.interior.gob. (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Pal, U.; Chaudhuri, B. Optical character recognition: A review. Pattern Recognition 2014, 47, 2–20. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, R.; Ghanshala, KK.; Joshi, R. Convolutional neural network (CNN) for image detection and recognition. Proceedings of 2018 IEEE 1st International Conference on Secure Cyber Computing and Communication, Jalandhar, 15-17 December 2018; pp. 278–282. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Y.; Lee, C. Recurrent neural networks for handwritten word recognition. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; pp. 1747–26.

- Cheema, MDA.; Shaiq, MD.; Mirza, F.; Kamal, A.; Naeem, MA. Adapting multilingual vision language transformers for low-resource Urdu optical character recognition (OCR). PeerJ Comput Sci 2024, 10, e1964. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. Proceedings of 29th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems - Volume 1, Montreal, Canada, 7-15 December 2015; pp. 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollar, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22-29 October 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, D.; Xiong, Y. EAST: An efficient and accurate scene text detector. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition pp. 2642–2651. Honolulu, Honolulu, USA, 21-26 July 2017; pp. 2642–2651. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, J.; Lee, B.; Kim, K.; Lee, H. Character region awareness for the detection of text in the wild. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Korea, 27-28 October 2019. pp. 9368–9377. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, USA, 27-30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Kashi, R.; Lopresti, D.; Nagy, G.; Wilfong, G. Why table ground-truthing is hard. Proceedings of Sixth International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition; pp. 129–13.

- Schreiber, S.; Agne, S.; Wolf, I.; Dengel, A.; Ahmed, S. DeepDeSRT: Deep Learning for detection and structure recognition of tables in document images. In 2017 14th IEEE IAPR International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Volume 1, pp. 1162–1167. Kyoto, Japan, 9-15 November 2017.

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to end object detection with transformers. In 16th European Conference on Computer Vision, pp. 213–229. Online, 23-28 August 2020.

- Smock, B.; Pesala, R.; Abraham, R. PubTables-1M: Towards Comprehensive Table Extraction from Unstructured Documents. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, Louisiana, 19-24 June 2022; pp. 4634–4642. [Google Scholar]

- Afzal, M.; Capobianco, S.; Malik, M.; Marinai, S.; Breuel, T.; Dengel, A.; Liwicki, M. Deepdocclassifier: Document classification with deep convolutional neural network. In 2015 13th International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, pp. 1111–1115. Nancy, France, 23-26 August 2015.

- Kang, L.; Kumar, J.; Ye, P.; Li, Y.; Doermann, D. Convolutional neural networks for document image classification. Proceedings of 22nd International Conference on Pattern Recognition 2014, Stockholm, Sweden, 24-28 August 2014; pp. 3168–3172. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L. ; Gomez, A; Kaiser, Ł; Lolosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. Long Beach, CA, USA, 4-9 December 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Springenberg, J. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. Proceedings of 9th International Conference on Learning Representations. Austria, 3-7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Lv, T.; Chen, J.; Cui, L.; Lu, Y.; Florencio, D.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Wei, F. TrOCR: Transformer-Based Optical Character Recognition with Pre-trained Models. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Seventh AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; pp. 13094–14.

- Touvron, H.; Cord, M.; Douze, M.; Massa, F.; Sablayrolles, A.; Jegou, H. Training data efficient image transformers & distillation through attention. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18-24 July 2021; Volume 139, pp. 10347–10357. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. RoBERTa: A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach. arXiv:1907.11692, 2019.

- Ströbel, P.; Hodel, T.; Boente, W.; Volk, M. The Adaptability of a Transformer-Based OCR Model for Historical Documents. In Coustaty, M., Fornés, A. (eds) Document Analysis and Recognition – ICDAR 2023 Workshops Proceedings, pp. 34-48. San José, CA, USA, 24-26 August 2023.

- Huang, Z.; Chen, K.; He, J.; Bai, X.; Karatzas, D.; Lu, S.; Jawahar, C. Competition on Scanned Receipt OCR and Information Extraction. Proceedings of 2019 International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Sydney, Australia, 22-25 September 2019; pp. 1516–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peffers, K.; Tuunanen, T.; Rothenberger, M.; Chatterjee, S. A Design Science Research Methodology for Information Systems Research. Journal of Management Information Systems 2007, 24, 45–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, A. Verification, Validation and Testing of Engineered Systems. In Wiley, Hoboken, 2010.

- Parliament of the Canary Islands. Regulations of the Parliament of the Canary Islands. Official Gazette, X Legislature, Number 183, 10L/PRRRP-0003, 2023. https://www.parcan.es/pub/reglamento.pdf. (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Baldominos, A.; Saez, Y.; Isasi, P. A Survey of Handwritten Character Recognition with MNIST and EMNIST. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9(15), 3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIST. NIST Special Database 19. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/srd/nist-special-database-19 (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Grother, P.; Hanaoka, K. NIST Special Database 19 Handprinted Forms and Characters Database. Technical Report 2016; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA.

- Suresh P, Giri S, Shakyac S. Deep learning based handwritten signature recognition. In NCE Journal of Science and Engineering (NJSE) (2020): 21.

- Bao, H.; Fong, L.; Wei, F. BEiT: BERT PreTraining of Image Transformers. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Learning Representations. Online, 25-29 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, X.; Mustafa, B.; Kolesnikov, A.; Beye, L. Sigmoid Loss for Language Image Pre-Training. arXiv:2303.15343T, 2023.

- Shi, B.; Bai, X.; Yao, C. An end-to-end trainable neural network for image-based sequence recognition and its application to scene text recognition. IEEE PAMI 2016, 39, 2298–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Cropped section of a simulated written petition image illustrating three human-performed handwritten signatures, each comprising an ID and signature that identify the respective signatories endorsing the simulated petition.

Figure 1.

Cropped section of a simulated written petition image illustrating three human-performed handwritten signatures, each comprising an ID and signature that identify the respective signatories endorsing the simulated petition.

Figure 2.

OCR Pipeline for HSV applied to Form-based Documents. (a) The objective is to identify and validate each ID, confirm that it is accompanied by a signature, and generate a report based on predefined metrics. (b) The pipeline begins with converting physical documents into digital images. (c) Text detection follows, locating the IDs and signatures of each signatory. (d) Each detected ID is passed to a recognizer, while each detected signature is sent to a signature detector to confirm its presence alongside the ID. (e) The validity of each recognized ID is verified, and a report summarizing the results is generated.

Figure 2.

OCR Pipeline for HSV applied to Form-based Documents. (a) The objective is to identify and validate each ID, confirm that it is accompanied by a signature, and generate a report based on predefined metrics. (b) The pipeline begins with converting physical documents into digital images. (c) Text detection follows, locating the IDs and signatures of each signatory. (d) Each detected ID is passed to a recognizer, while each detected signature is sent to a signature detector to confirm its presence alongside the ID. (e) The validity of each recognized ID is verified, and a report summarizing the results is generated.

Figure 3.

OCR Pipeline for HSV Applied to Written Petitions Using Transformer-based Models. (a) The pipeline begins with dataset preparation, including the generation of the ID Dataset for fine-tuning the TrOCR model and the FD Dataset for creating written petition forms used in system evaluation. (b) The text detection submodule locates handwritten IDs and signatures for each signatory using a transformer-based table extraction model. (c) Detected IDs are processed by the fine-tuned TrOCR model to extract the corresponding digital text, while signatures are analyzed using a transformer-based image classification model to confirm their presence alongside the associated IDs. (d) Each recognized ID is validated, and a summary report is generated.

Figure 3.

OCR Pipeline for HSV Applied to Written Petitions Using Transformer-based Models. (a) The pipeline begins with dataset preparation, including the generation of the ID Dataset for fine-tuning the TrOCR model and the FD Dataset for creating written petition forms used in system evaluation. (b) The text detection submodule locates handwritten IDs and signatures for each signatory using a transformer-based table extraction model. (c) Detected IDs are processed by the fine-tuned TrOCR model to extract the corresponding digital text, while signatures are analyzed using a transformer-based image classification model to confirm their presence alongside the associated IDs. (d) Each recognized ID is validated, and a summary report is generated.

Figure 4.

Synthetic Dataset Preparation Architecture. The figure illustrates the architecture for preparing dynamic synthetic datasets, where N represents the number of pages with handwritten IDs and signatures, S denotes the number of signatories per page for the FD dataset, and V indicates the number of handwritten IDs to be generated for the ID dataset.

Figure 4.

Synthetic Dataset Preparation Architecture. The figure illustrates the architecture for preparing dynamic synthetic datasets, where N represents the number of pages with handwritten IDs and signatures, S denotes the number of signatories per page for the FD dataset, and V indicates the number of handwritten IDs to be generated for the ID dataset.

Figure 5.

Examples of four synthetically generated handwritten IDs and corresponding signatures for four signatories, extracted from the FD dataset. D.N.I. refers to “ID” and Firma means “signature” in Spanish.

Figure 5.

Examples of four synthetically generated handwritten IDs and corresponding signatures for four signatories, extracted from the FD dataset. D.N.I. refers to “ID” and Firma means “signature” in Spanish.

Table 1.

NLP and ML metric results for the TrOCR model without fine-tuning on ID datasets. FFD-S: FD dataset with N= 1,500 pages containing synthetic data. FFD-R: FD Dataset with N= 50 pages containing real human handwriting data. NPS: No post-processing steps applied. PS1: Post-processing with step 1 and step 2. PS2: Comprehensive post-processing, including step 1, step 2, step 3.

Table 1.

NLP and ML metric results for the TrOCR model without fine-tuning on ID datasets. FFD-S: FD dataset with N= 1,500 pages containing synthetic data. FFD-R: FD Dataset with N= 50 pages containing real human handwriting data. NPS: No post-processing steps applied. PS1: Post-processing with step 1 and step 2. PS2: Comprehensive post-processing, including step 1, step 2, step 3.

|

|

NPL metrics |

ML metrics |

| Model |

Postprocessing

Method |

Accuracy |

Precision |

Recall |

F1 |

CER |

Accuracy |

Precision |

Recall |

F1 |

TrOCR

FDD-S |

NPS |

69.11 |

70.02 |

86.65 |

77.45 |

30.89 |

8,08 |

96,21 |

8,09 |

9,71 |

TrOCR

FDD-S |

PS1 |

83.36 |

85.54 |

84.83 |

85.18 |

16.64 |

51.06 |

86.01 |

51.88 |

64.72 |

TrOCR

FDD-S |

PS2 |

84.38 |

86.58 |

84.67 |

85.61 |

15.62 |

69.96 |

92.26 |

73.26 |

81.51 |

TrOCR

FDD-R |

NPS |

56.08 |

57.01 |

73.62 |

64.25 |

43.92 |

5.08 |

100 |

5.08 |

9.66 |

TrOCR

FDD-R |

PS1 |

70.31 |

72.52 |

71.82 |

72.16 |

29.69 |

38.04 |

72.98 |

38.86 |

50.71 |

TrOCR

FDD-R |

PS2 |

71.36 |

73.54 |

71.67 |

72.59 |

28.64 |

46.93 |

69.24 |

50.23 |

58.22 |

Table 2.

NLP and ML metric results for the TrOCR model, fine-tuned on ID datasets of varying sizes (V =100, 1,000, 2,000, 3,000, 4,000) with no post-processing steps applied. FFD-S: FD dataset with N= 1,500 pages containing synthetic data. FFD-R: FD Dataset with N= 50 pages containing real human handwriting data.

Table 2.

NLP and ML metric results for the TrOCR model, fine-tuned on ID datasets of varying sizes (V =100, 1,000, 2,000, 3,000, 4,000) with no post-processing steps applied. FFD-S: FD dataset with N= 1,500 pages containing synthetic data. FFD-R: FD Dataset with N= 50 pages containing real human handwriting data.

| |

|

NPL metrics |

ML metrics |

| Model |

ID (V) |

Accuracy |

Precision |

Recall |

F1 |

CER |

Accuracy |

Precision |

Recall |

F1 |

TrOCR

FDD-S |

100 |

97.74 |

98.84 |

98.84 |

98.84 |

2.26 |

80.00 |

88.89 |

88.89 |

88.89 |

TrOCR

FDD-S |

1000 |

98.02 |

98.86 |

98.84 |

98.84 |

1.98 |

81.96 |

88.44 |

88.86 |

88.64 |

TrOCR

FDD-S- |

2000 |

98.11 |

98.86 |

98.86 |

98.86 |

1.89 |

82.32 |

88.44 |

88.84 |

88.63 |

TrOCR

FDD-S |

3000 |

98.91 |

99.89 |

98.91 |

99.39 |

1.09 |

90.48 |

96.04 |

94.59 |

95.30 |

TrOCR

FDD-S |

4000 |

98.14 |

98.82 |

98.84 |

98.82 |

1.86 |

89.32 |

91.02 |

91.24 |

91.12 |

TrOCR

FDD-R |

100 |

83.64 |

84.36 |

84.52 |

84.43 |

16.36 |

73.22 |

80.02 |

80.00 |

80.00 |

TrOCR

FDD-R |

1000 |

84.00 |

84.34 |

84.36 |

84.34 |

16.00 |

74.21 |

84.06 |

82.24 |

83.14 |

TrOCR

FDD-R |

2000 |

84.06 |

84.51 |

84.48 |

84.49 |

15.94 |

78.44 |

86.02 |

86.44 |

86.22 |

TrOCR

FDD-R |

3000 |

84.31 |

84.58 |

84.86 |

84.71 |

15.69 |

80.04 |

88.96 |

88.96 |

88.96 |

TrOCR

FDD-R |

4000 |

83.98 |

84.52 |

84.32 |

84.41 |

16.02 |

80.01 |

86.02 |

86.24 |

86.12 |

Table 3.