1. Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer death in women worldwide [

1]. In reality, BC is a heterogeneous disease encompassing multiple subtypes, each with different molecular characteristics, prognoses, and responses to therapies, and characterized for the presence of cell surface receptors, such as estrogen receptors (ER), progesterone receptors (PR) and the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) [

2]. They are generally divided into at least four major molecular subtypes: Luminal A and Luminal B (~30-70% of cases of breast cancers), HER2 tumors (~ 30%), and the subtypes lacking ER, PR and HER2, referred to as triple negative breast cancer (TNBC; ~15-20%). Patients diagnosed with TNBC have increased recurrence and the poorest diagnosis [

3]. TNBC are unresponsive to current targeted therapies and are thus treated with conventional chemotherapies. However, even with combination treatment regimens, survival rates remain low. In fact, metastatic BC is associated with a lethal outcome and is generally considered incurable [

4], the median survival of patient with metastatic BC being less than one year [

2,

3]. Moreover, because the global incidence of BC is projected to rise by 38% and its related deaths by 68% by 2050 [

5], novel and more effective compounds than existing conventional therapeutic agents are critically needed to fight primary and metastatic BC.

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a cellular program where epithelial cells lose their polarized structure and acquire a more mesenchymal-like phenotype, enhancing their migratory and invasive capabilities [

6]. In malignant diseases, this transformation is assumed to be a critical step in the progression of tumor cells from both the pre-invasive to invasive state, and from organ confined to metastatic disease [

7]. During EMT, cancer cells are typically characterized by a decreased expression of E-cadherin and increased expression of N-cadherin, vimentin as well as expression of cellular proteases. Oncogenic EMT is thus associated with increased tumor cell motility, invasiveness, metastasis, and resistance to therapy in BC [

6,

7].

Chronic inflammation [

8] and EMT [

9,

10,

11,

12] plays a crucial role in BC progression and are strongly linked to the development of metastatic disease, which is the leading cause of death in BC patients [

1,

2,

3,

5]. Recent clinical and experimental data suggest that derived factors from tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) plays a crucial role in the regulation of EMT in BC [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Activated TAMs release cytokines and other factors that directly interact with BC cells, leading to increased cell adhesion, motility, and invasion, hallmarks of EMT [

9,

10,

11,

12]. TAMs, particularly M1-polarized macrophages (MØs), release high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL6 and TNFα, which mediates the respective activation of JAK/STAT3 [

15,

16] and NFκB/p38 MAPK signaling pathways [

17,

18]. In BC cells, the signaling pathways TNFα/NFκB and IL6/STAT3 are known to promote tumor progression via activation of key EMT-related transcription factors, such as Twist, Snail1, Slug and ZEB1 [

9,

10,

11,

12,

15,

16,

17,

18]. These transcription factors are responsible for inducing the expression of so-called mesenchymal proteins or markers, while inhibiting the expression of epithelial cell-specific proteins [

6]. For instance, it has been shown that TNFα/NFκB signaling pathway can play a role in the overexpression of matrix metalloproteases (MMPs), including MMP2 and MMP9, as well as vimentin, a protein that composes the intermediate filaments of mesenchymal cells via the transcription factor Snail1 [

19,

20]. Also, it has been shown that activated IL6/STAT3 signaling pathway inhibits the expression of E-cadherin, a protein present in the adherens junctions of epithelia, in addition to inducing the expression of vimentin and N-cadherin via the activation of the transcription factors Snail1 and Twist1 [

21,

22].

Therefore, therapeutic targeting of pro-tumor inflammatory mediators and signaling pathways has strong biological rationale to develop new therapeutic approaches. In this optic, an aminobenzoic acid derivative, namely DAB-1, was initially identified in our laboratory as a potential drug to target cancer-related inflammation [

23,

24]. Our studies indicated that treatment with DAB-1 has no obvious effect on normal mice development without any signs of vital organs dysfunction, and that tumor is one of the main sites of DAB-1 accumulation. In addition, using preclinical models of murine bladder cancer, we demonstrated that repeated intraperitoneal injections of DAB-1 inhibited tumor growth by 90% and stopped the formation of pulmonary metastasis, likely by inhibiting TNFα/NFκB and IL6/STAT3 signaling pathways [

24].

In our quest for a more efficient cancer treatment, the structure of DAB-1 was modified to provide a second-generation molecule named DAB-2-28, with enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological properties compared to DAB-1 [

25,

26]. Data from in vitro studies revealed that DAB-2-28 has less cytotoxic activity with greater efficiency than DAB-1 to inhibit the production of nitric oxide (NO) as well as the activation of pro-inflammatory signaling pathways IL6/STAT3 and TNFα/NFκB. Moreover, while DAB-2-28 exhibited similar anti-inflammatory activity in vivo to DAB-1 in a model of carrageenan-induced acute inflammation, it efficiently inhibited the expression of the enzymes iNOS and COX-2 in peritoneal MØs. Notably, DAB-2-28 was more efficient to inhibit tumor development in models of murine bladder cancer. Thus, our studies provided preclinical proof-of-principle for DAB-2-28 molecule in the treatment of cancer-related inflammation [

25,

26].

In this study, we hypothesize that DAB-2-28 could act on BC cells by inhibiting key inflammatory pathways involved in tumor progression and metastasis development. DAB-2-28 would particularly act on those activated by MØ-derived factors that promote the EMT process, as well as tumor migration and invasion.

2. Results

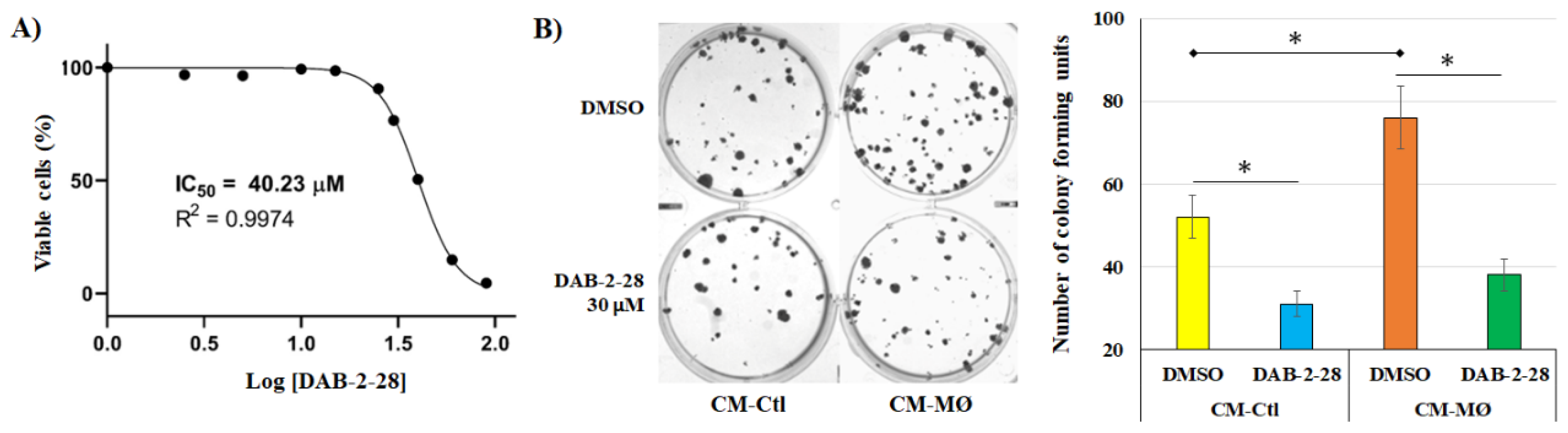

2.1. Impact of DAB-2-28 on the Viability and Proliferation of MCF-7 Cells Stimulated with Macrophage-Derived Factors

Our previous studies confirmed that the negative effects of both DAB-1 and DAB-2-28 on bladder cancer cell viability are not caused by an increase in cell death but rather by the arrest of cell proliferation [

23,

24,

25,

26]. We also demonstrated that the optimal doses of DABs required to affect the activation induced by pro-tumor signals in vitro in bladder cancer cells without affecting their viability are between 10 and 50 μM. Thus, before investigating the impact of DAB-2-28 on the various parameters related to the EMT process induced in MCF-7 breast cancer cells by MØ-derived factors, we began by investigating the viability and proliferation of MCF-7 cells in response to different concentrations of DAB-2-28. The cell viability assay (MTT) performed showed that the concentration of DAB-2-28 at which the number of viable (or metabolically active) MCF-7 cells was reduced by 50% (IC

50) compared to the control was 40.2 ± 1.7 μM (

Figure 1A).

Next, to study the survival and proliferation of MCF-7 cells in response to cotreatment with MØ-derived factors and DAB-2-28, a colony formation assay was performed (

Figure 1B). The colony formation assay (or clonogenic assay) is an in vitro cell survival assay based on the ability of a single cell to survive, proliferate, and develop into a large colony through clonal expansion [

27]. To quantify the clonogenic activity of the cells under study, the colony to be counted was defined as a cell cluster of at least 50 cells, all originating from the division of a single cell. To perform the colony formation assay with MCF-7 cells, a 30 μM dose of DAB-2-28 was used on the basis that MCF-7 cells viability rate was established at approximately 77% after DAB-2-28 treatment at this dose (

Figure 1A). The results of the clonogenic assay show an increase in the number of colonies when the cells were stimulated with CM-MØ compared to CM-Ctl. However, with DAB-2-28 pretreatment, the number of colonies formed by MCF-7 cells declined when they were stimulated with both CM-Ctl and CM-MØ, with a decrease estimated at 40% and 51%, respectively (

Figure 1B).

From these data, for the rest of the experiments, we used a 30 µM concentration to ensure that treatments with DAB-2-28 were not excessively toxic to cells.

2.2. Effects of Macrophage-Derived Factors and DAB-2-28 on the Induction of EMT in MCF-7 Cells

It is well established that in the tumor microenvironment, MØs promote cancer cell survival and invasion through the production of numerous inflammatory mediators that participate in extracellular matrix remodeling, angiogenesis, and suppression of antitumor immune responses [

13,

14]. MØ-derived factors are also thought to act on cancer cells and promote the typical features of EMT, including activation of pro-EMT transcription factors (Twist1, Snail, and ZEB) associated with a loss of E-cadherin expression and an increase in vimentin, as well as an increase in invasive potential via the expression of MMP2 and/or MMP9 [

13,

14]. To determine whether MØ-derived factors induce the EMT process in MCF-7 cells, we conducted a comparative study of soluble factors present in CM-Ctl and CM-MØ by evaluating their ability to induce a morphological change in mesenchymal phenotype and to regulate the expression of an epithelial marker, the cell surface glycoprotein E-cadherin, and a mesenchymal marker, the transcription factor Snail1.

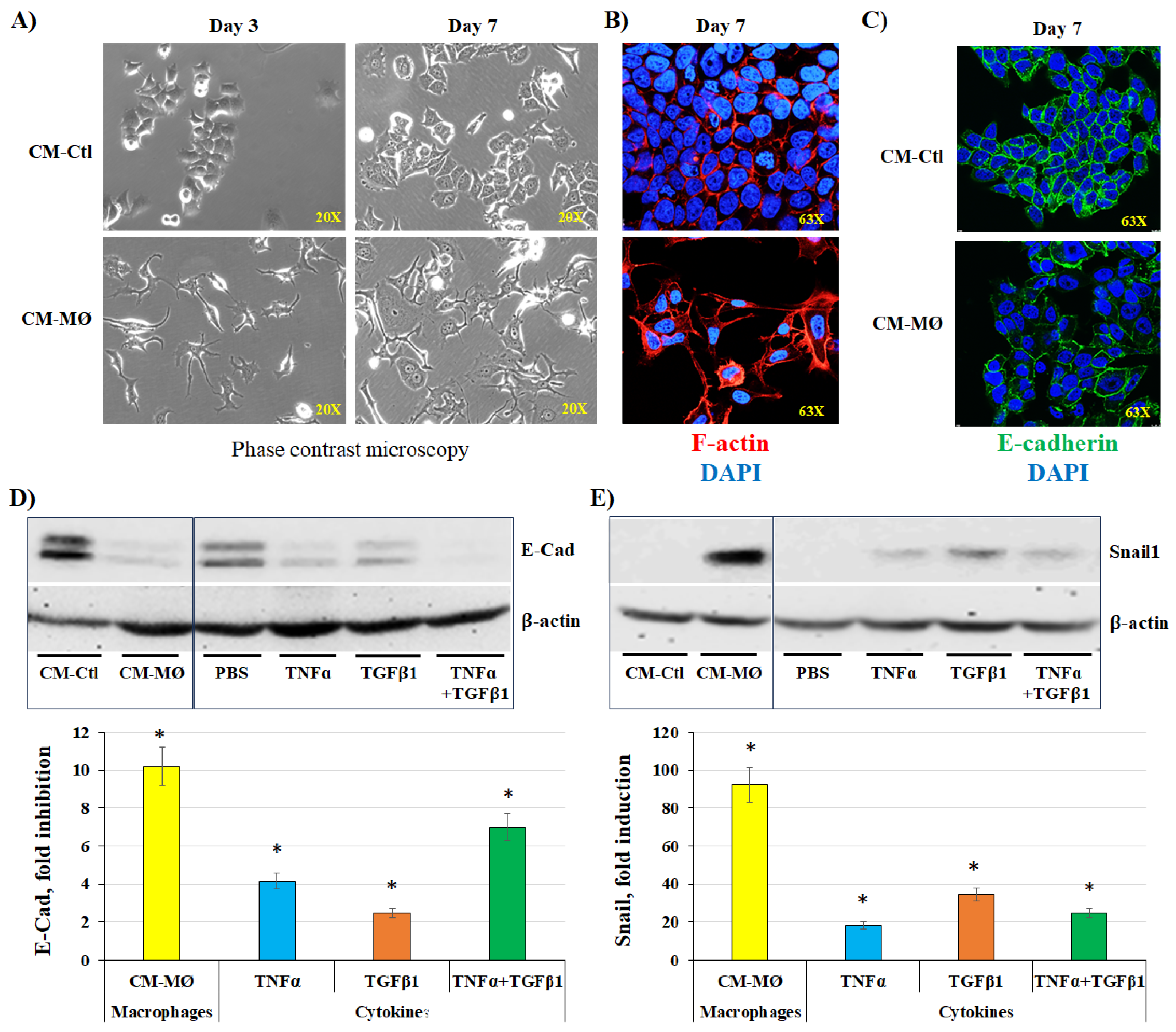

2.2.1. Induction of EMT by Macrophage-Derived Factors

In a first series of experiments, MCF-7 cells were stimulated with CM-Ctl or CM-MØ for 7 days, and cell morphology was monitored throughout incubation under both conditions. Pictures were taken under a phase-contrast microscope on days 3 and 7 (

Figure 2A). Data obtained by phase contrast microscopy and immunofluorescence indicate that MCF-7 cells adopt a different morphology when incubated with CM-MØ. The cells were found with a more irregular and elongated shape with several cytoplasmic extensions, which is characteristic of mesenchymal cells [

28]. In contrast, cells incubated with CM-Ctl maintained a rather regular and rounded shape, characteristic of epithelial cells (

Figure 2A). On day 7 of incubation with both CM, the conformation of actin filaments inside cancer cells was verified by immunofluorescence by labeling them with phalloidin (

Figure 2B; red staining). Images obtained by fluorescence microscopy show that the conformation of actin filaments is disrupted when MCF-7 cells were incubated with CM-MØ compared to CM-Ctl. Indeed, in epithelial cells, actin filaments are arranged at cell junctions, all around plasma membranes, a pattern that we observed in cells incubated with CM-Ctl (

Figure 2B). When cells were incubated with CM-MØ, actin filaments formed a network of stress fibers like that present in mesenchymal cells [

7], as we observed by the presence of a cluster of fibers in the cytoplasm of MCF-7 cells (

Figure 2B; F-actin).

The expression of epithelial and mesenchymal markers was studied by immunofluorescence (IF) and the western blot (WB) technics in MCF-7 cells stimulated with CM-Ctl and CM-MØ. To validate and further support these results, cells were also stimulated with three MØ-derived factors known to induce EMT, namely IL6, TNFα, and TGFβ1 [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Regarding the epithelial marker E-cadherin, IF microscopy images show a marked decrease in E-cadherin expression at the plasma membrane of MCF-7 cells stimulated with CM-MØ compared to CM-Ctl (

Figure 2C; E-Cad). The results of the WB analysis indicate that when MCF-7 cells were stimulated with CM-MØ, the expression of E-cadherin is inhibited by approximately 10-fold compared to stimulation with CM-Ctl, whereas, compared to PBS, the inhibition rates of E-cadherin were evaluated to 4-fold, 2-fold, and 7-fold when the cells were respectively stimulated with TNFα alone, TGFβ1 alone, or the combination of TNFα plus TGFβ1 (

Figure 2D). In contrast to E-cadherin, WB analysis indicated that the expression of the mesenchymal marker Snail1 increase of approximately 92-fold when MCF-7 cells were stimulated with CM-MØ compared to CM-Ctl (Figure 9C). In cells exposed to PBS (control) and cytokines with pro-EMT activity, induction rates were evaluated to 18-fold, 34-fold, and 24-fold when the cells were stimulated with TNFα alone, TGFβ1 alone, or the combination of TNFα plus TGFβ1, respectively (

Figure 2D).

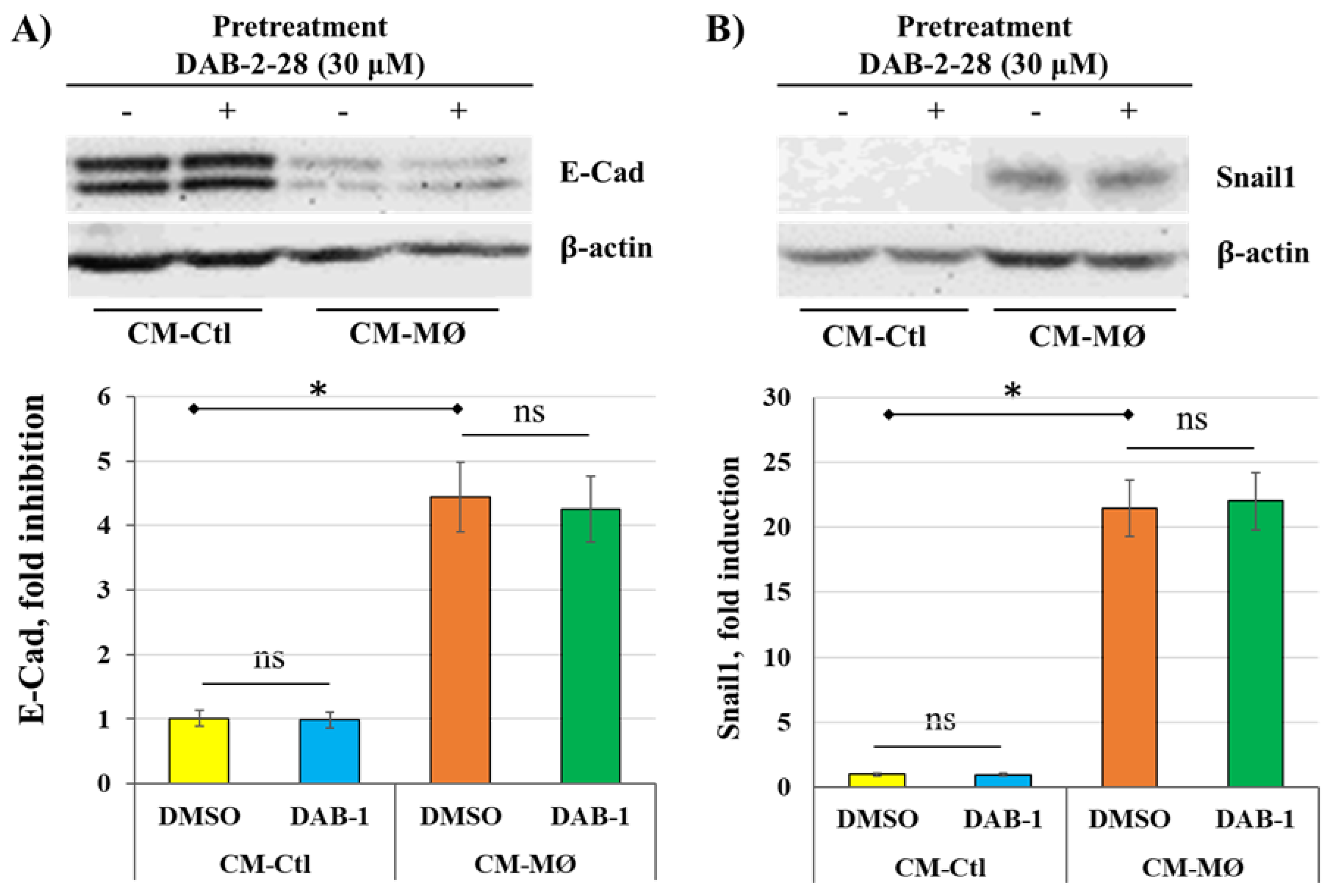

2.2.2. Effect of DAB-2-28 On Cellular Features Associated with EMT

To determine whether DAB-2-28 affects the cellular characteristics typically associated with the EMT process induced by MØs-derived factors in MCF-7 cells, biochemical and biological analyses were performed to study a) the expression of Snail1 and E-cadherin, by WB; b) cell invasion, using a Boyden chamber microinvasion assay; c) cell motility, by a wound healing assay; d) the activation and expression of the metalloproteinase MMP9, using gelatin zymography and WB, respectively; and e) the induction of signaling pathways involved in tumor progression and EMT, by WB.

As previously observed, the study on Snail1 and E-cadherin expression indicates that, compared to CM-Ctl, CM-MØ induces a significant decrease in E-cadherin expression (

Figure 3A) as well as a strong expression of Snail1 (

Figure 3B) in MCF-7 cells not pretreated with DAB-2-28. However, the differential expression of E-cadherin and Snail1 proteins induced by factors present in CM-MØ was not affected in cells pretreated with DAB-2-28 (

Figure 3).

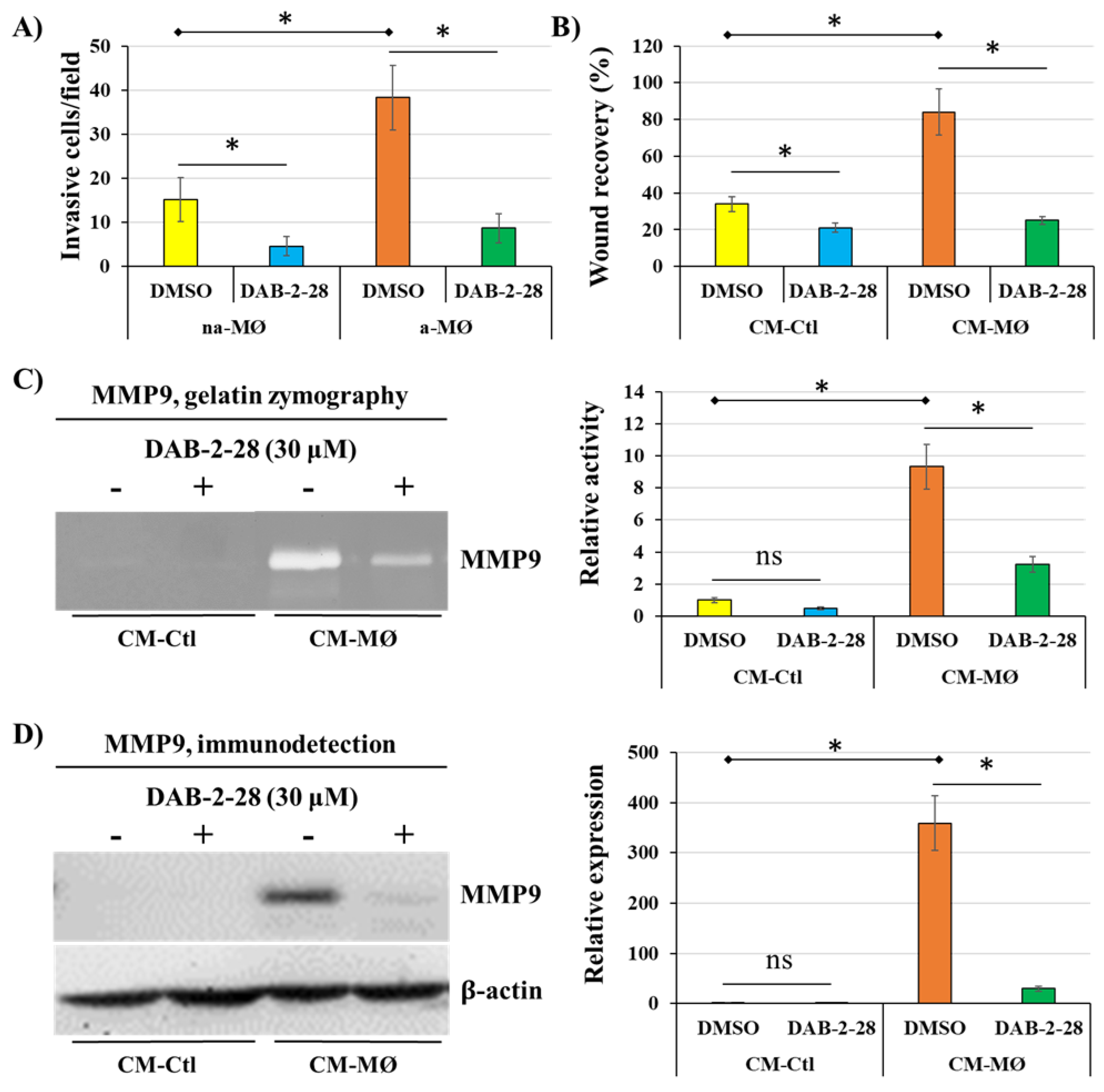

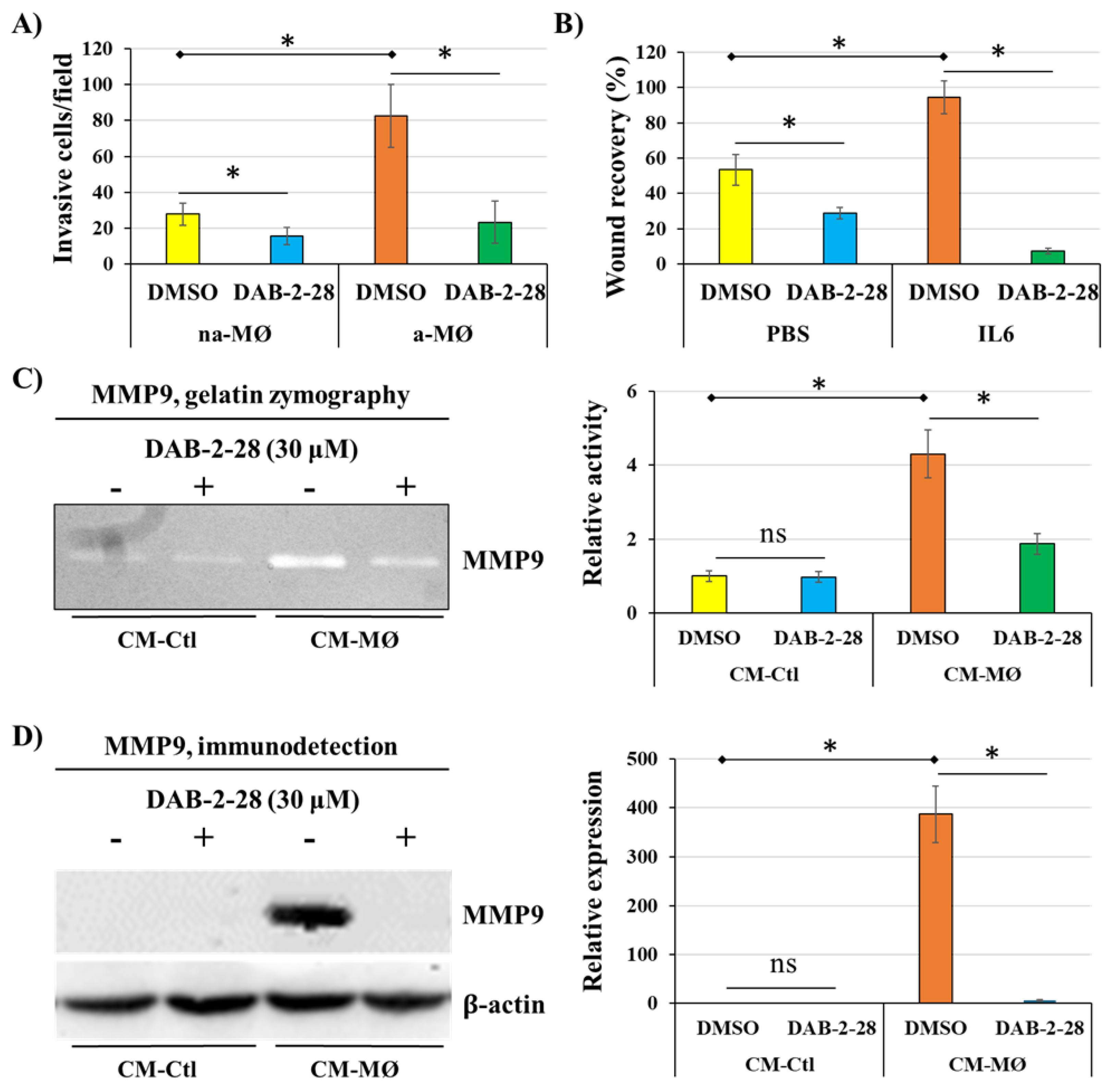

Next, a series of experiments were performed to evaluate the impact of DAB-2-28 on the invasive potential acquired when epithelial-phenotype MCF-7 cancer cells undergo EMT in response to MØ-derived factors (

Figure 4). First, invasion assays were performed by cocultures of MCF-7 cells with non-activated (na-MØ) or activated (a-MØ) MØs to allow paracrine interactions between cancer cells and MØs. To quantify the invasive activity of MCF-7 cells, we counted the invasive cells per field, depending on the culture and pretreatment conditions. As reported in

Figure 4A, without DAB-2-28 pretreatment, the number of invasive MCF-7 cells was approximately 2.5 times greater when cocultured with a-MØ, compared to the number of cells cocultured with na-MØ. In contrast, when pretreatments with 30 μM DAB-2-28 were performed, the number of invasive MCF-7 cells significantly decreased (

Figure 4A).

Next, migration assays were performed with MCF-7 cells pretreated with vehicle (DMSO) or 30 μM DAB-2-28, and then stimulated with CM-Ctl or CM-MØ. To quantify the motility/migration properties of MCF-7 cells, we assessed the percentage of wound closure. The percentage of wound closure was calculated from the wound area measured on image captures taken at the initial (t = 0 h) and final (t = 24 h) times of the experiment. The results reported in

Figure 4B show that, without DAB-2-28 pretreatment, MCF-7 cells were more motile when stimulated with CM-MØ compared to CM-Ctl, with wound closures at t = 24 h being evaluated at 83%. In contrast, DAB-2-28 pretreatments significantly decreased the wound closure ability of CM-MØ-stimulated MCF-7 cells, with wound closure percentages at t = 24 h being 27% with 30 μM DAB-2-28 (

Figure 4B).

To further document the effect of DAB-2-28 on the invasive potential of MCF-7 cells in response to MØ-derived factors, the MMP9 proteinase was studied for its activation using gelatin zymography (

Figure 4C) and its expression by WB (

Figure 4D). An increase in MMP9 gelatinase activity was observed when cells were stimulated with CM-MØ, while it was decreased by 30 μM DAB-2-28 treatment (

Figure 4C). Similarly, an increase in MMP9 protein expression was induced when cells were stimulated with CM-MØ, and this inductive effect was inhibited when they were pretreated with 30 μM DAB-2-28 (

Figure 4D).

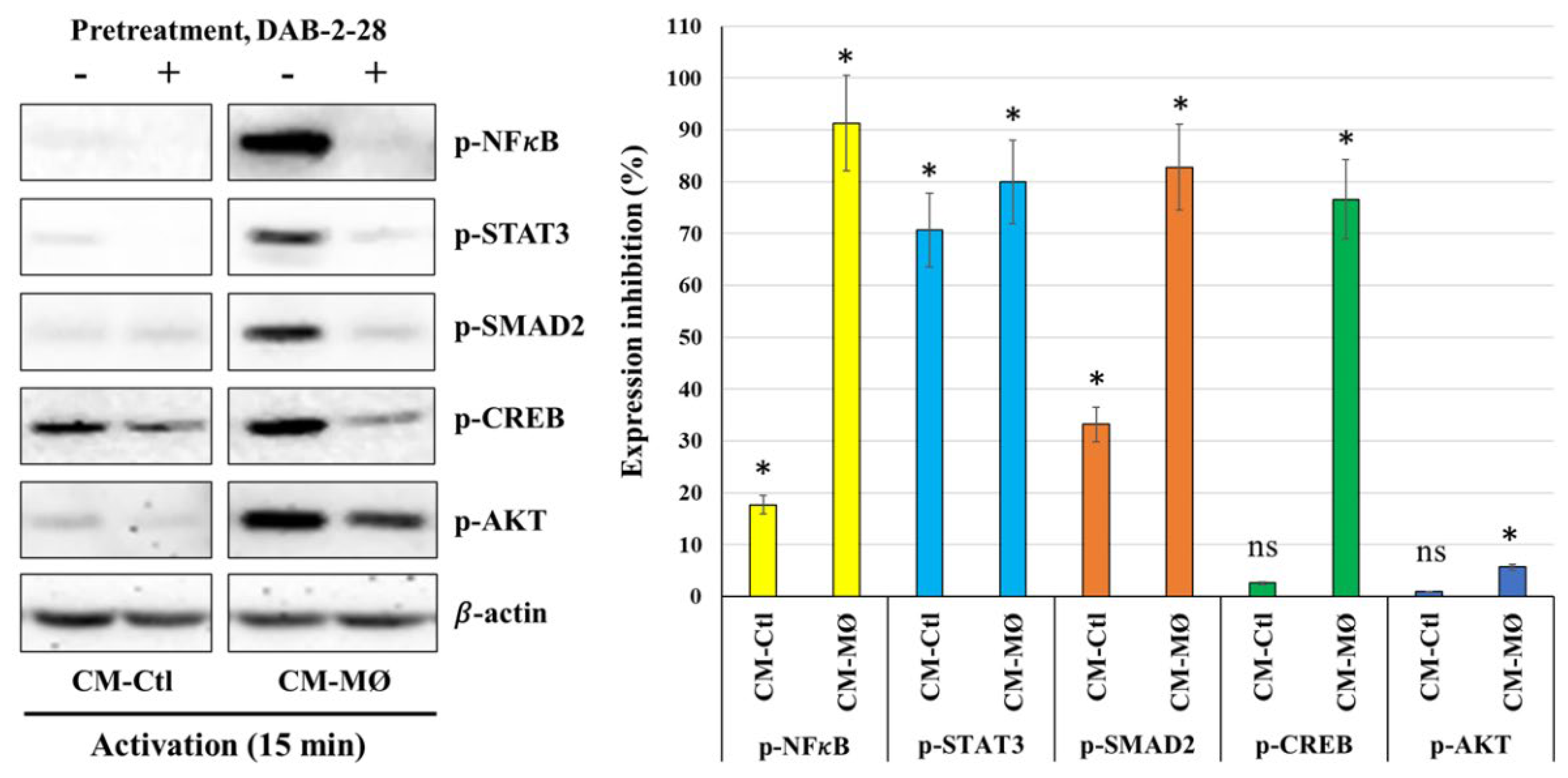

Finally, a cell signaling study was performed to better understand the antitumoral action mechanism of DAB-2-28 on EMT initiation in MCF-7 cells in response to MØ-derived factors (

Figure 5). In this study, cells were first pretreated with DAB-2-28 (30 μM) or DMSO for 1 h and then stimulated with CM-Ctl or CM-MØ for 15 min. The data reported in

Figure 5 show that the phosphorylation levels of NF-κB, STAT3, AKT and SMAD2 proteins were significantly increased when MCF-7 cells were subjected to 15 min activation by CM-MØ. Of note, this increase in the activation of pro-TEM signaling proteins was greatly inhibited when cells were pretreated with DAB-2-28, except for AKT. The results obtained also show relatively high levels of the active/phosphorylated form of CREB protein in both CM-Ctl and CM-MØ-stimulated MCF-7 cells. However, the levels of the active/phosphorylated form of CREB protein were decreased after pretreatment with DAB-2-28 and activation with both CM-Ctl and CM-MØ (

Figure 5).

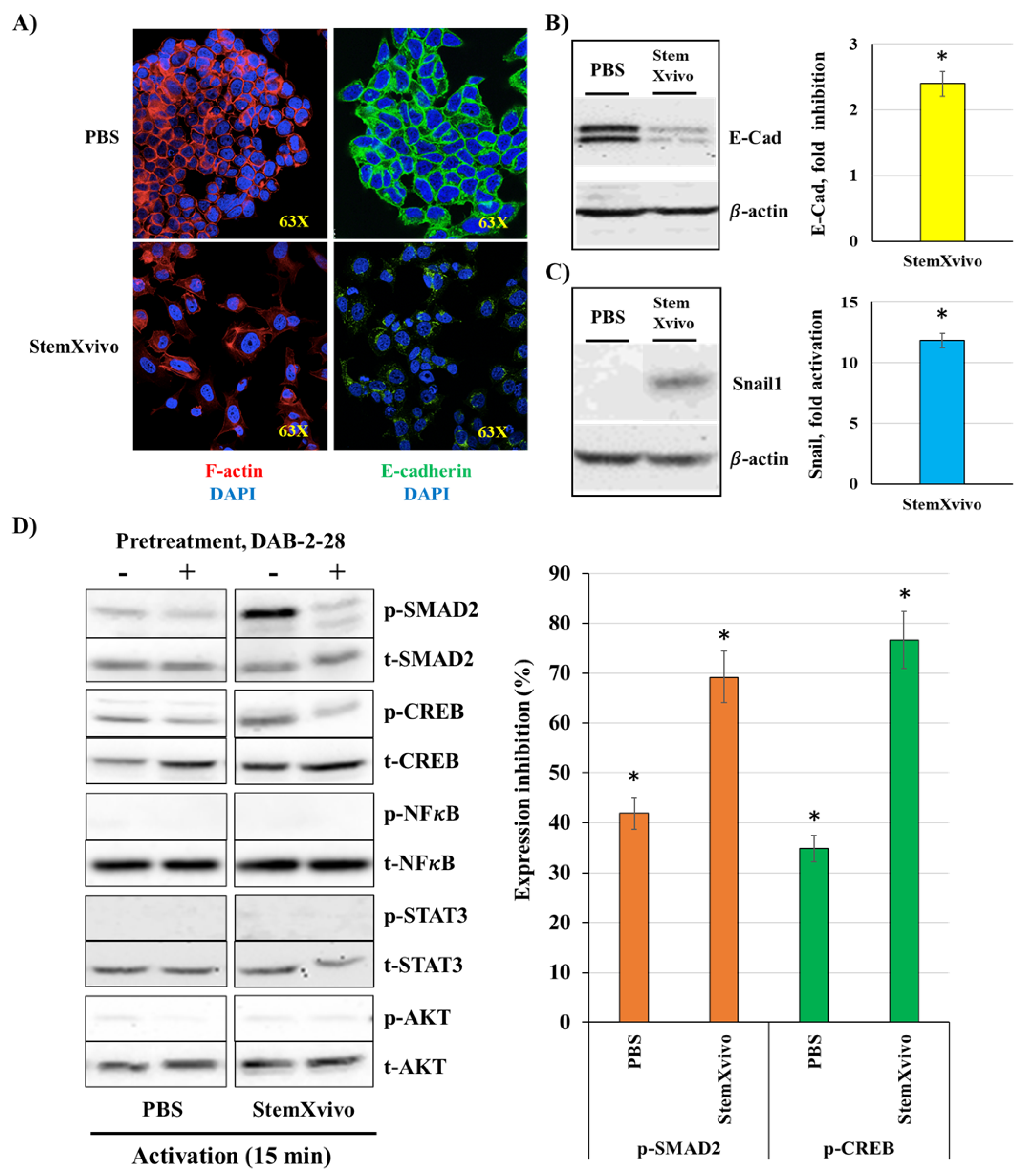

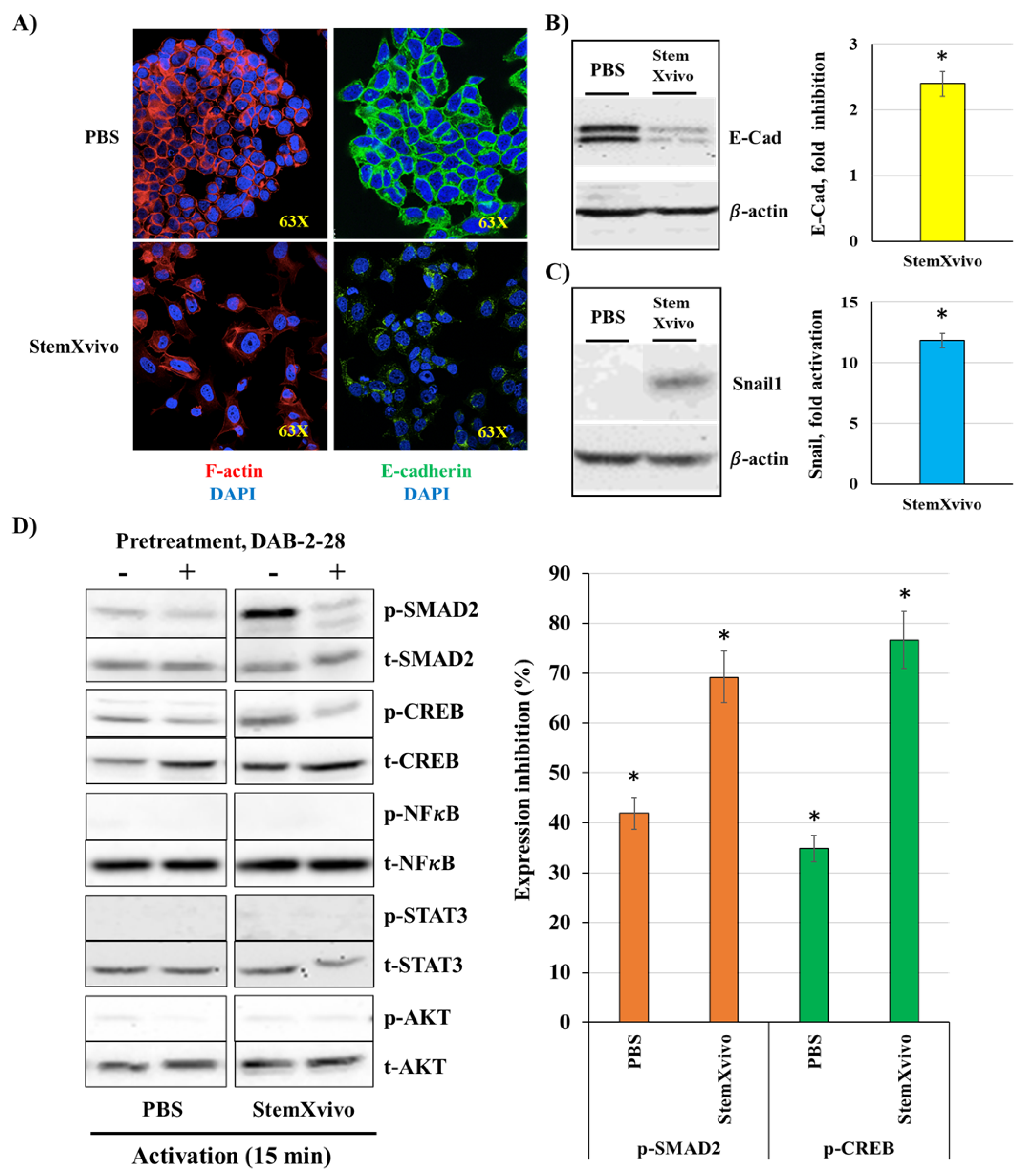

2.3. Induction of EMT in MCF-7 Cells by The StemXvivo Reagent

Our results indicated that MØ-derived factors induce TEM in MCF-7 cells, but DAB-2-28 molecule did not affect the expression of Snail1 or E-cadherin. However, this small molecule can inhibit other parameters related to EMT and tumor aggressiveness, such as invasion and pro-tumor signaling pathways. Subsequently, we opted for an alternative method of EMT induction using the StemXvivo

® EMT Inducing Media reagent. The objective of the experiments performed was twofold: to determine which pathways are activated by the StemXvivo reagent and which are inhibited by treatment with DAB-2-28. The StemXvivo reagent is a culture medium supplement containing several factors, including antibodies against human E-cadherin protein and human TGFβ cytokine. It has been designed to induce EMT in several cell lines, including MCF-7 cells [

29]. First, we confirmed the ability of this reagent to induce EMT in MCF-7 cells by observing the presence of E-cadherin and then the conformation of actin filaments (phalloidin labeling) by immunofluorescence (

Figure 6A) and the expression of Snail1 and E-cadherin by WB (

Figure 6B-C). Analysis of the microscopy images showed a decrease in E-cadherin expression by immunofluorescence as well as a change in the conformation of actin filaments in cells stimulated with the StemXvivo reagent (

Figure 6A). In addition, WB analyses revealed an increase in Snail1 expression and a decrease in E-cadherin expression (

Figure 6B-C). For signaling studies, MCF-7 cells were pretreated for 1 h with 30 μM DAB-2-28 and then stimulated with StemXvivo for 15 min (

Figure 6D). The study was limited to the immunodetection of proteins in the phosphorylated form of the most relevant pro-TEM signaling proteins, including NFκB, STAT3, SMAD2, and CREB. The results reported in

Figure 6D show low or no detection of NFκB, STAT3, and AKT proteins in the active form under both conditions, but an increase in the active form of SMAD2 and CREB proteins induced by the StemXvivo reagent. Of note, densitometry analysis shows that DAB-2-28 inhibits the activation of SMAD2 and CREB proteins when induced by the StemXvivo reagent (

Figure 6D).

2.4. Antitumor Effect of DAB-2-28 on Triple-Negative MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cells

To test the antitumoral effects of DAB-2-28 on cells with a mesenchymal phenotype, several experiments were performed with the triple-negative MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line. First, we determined the effect of DAB-2-28 on cell invasion, using a Boyden chamber invasion assay (

Figure 7A), and cell motility, using a wound closure migration assay (

Figure 7B). The results reported in

Figure 7A show that coculture with activated MØs (a-MØ) increases the number of invasive cells per field, compared to coculture with non-activated MØs (na-MØ). Furthermore, pretreatment with 30 μM DAB-2-28 efficiently decreased the number of invasive cells when MDA-MB-231 cells were cocultured with both, na-MØs and a-MØs (

Figure 7A).

Our published studies have demonstrated that activation of the IL6/STAT3 pathway plays a major role in the induction of cell motility, especially in MØs and bladder cancer cells [

23]. The results reported in

Figure 7B confirm that stimulation with IL6 induces migration of MDA-MB-231 cells, with approximately 90% wound closure after 24 h of incubation with IL6, compared to 50% with PBS. However, MDA-MB-231 cells become less motile and less efficient to close the wound following DAB-2-28 treatment, the wound closure level being approximately 30% when incubated with PBS and 10% with IL6 (

Figure 7B).

Next, to better understand the inhibitory mechanism of DAB-2-28 on the invasive capacity of MDA-MB-231 cells, we determined MMP9 activation (

Figure 7C) and expression (

Figure 7D). Gelatin zymography results show that stimulation of MDA-MB-231 cells with CM-MØ increases MMP9 gelatinase activity, compared to stimulation with CM-Ctl. In addition, pretreatment with DAB-2-28 at 30 μM decreases the activity of MMP9 secreted by MDA-MB-231 cells stimulated with CM-MØ (

Figure 7C). WB results demonstrate that MMP9 expression is significantly induced by CM-MØ stimulation and that this increase was completely inhibited when cells were pretreated with 30 μM DAB-2-28 (

Figure 7D).

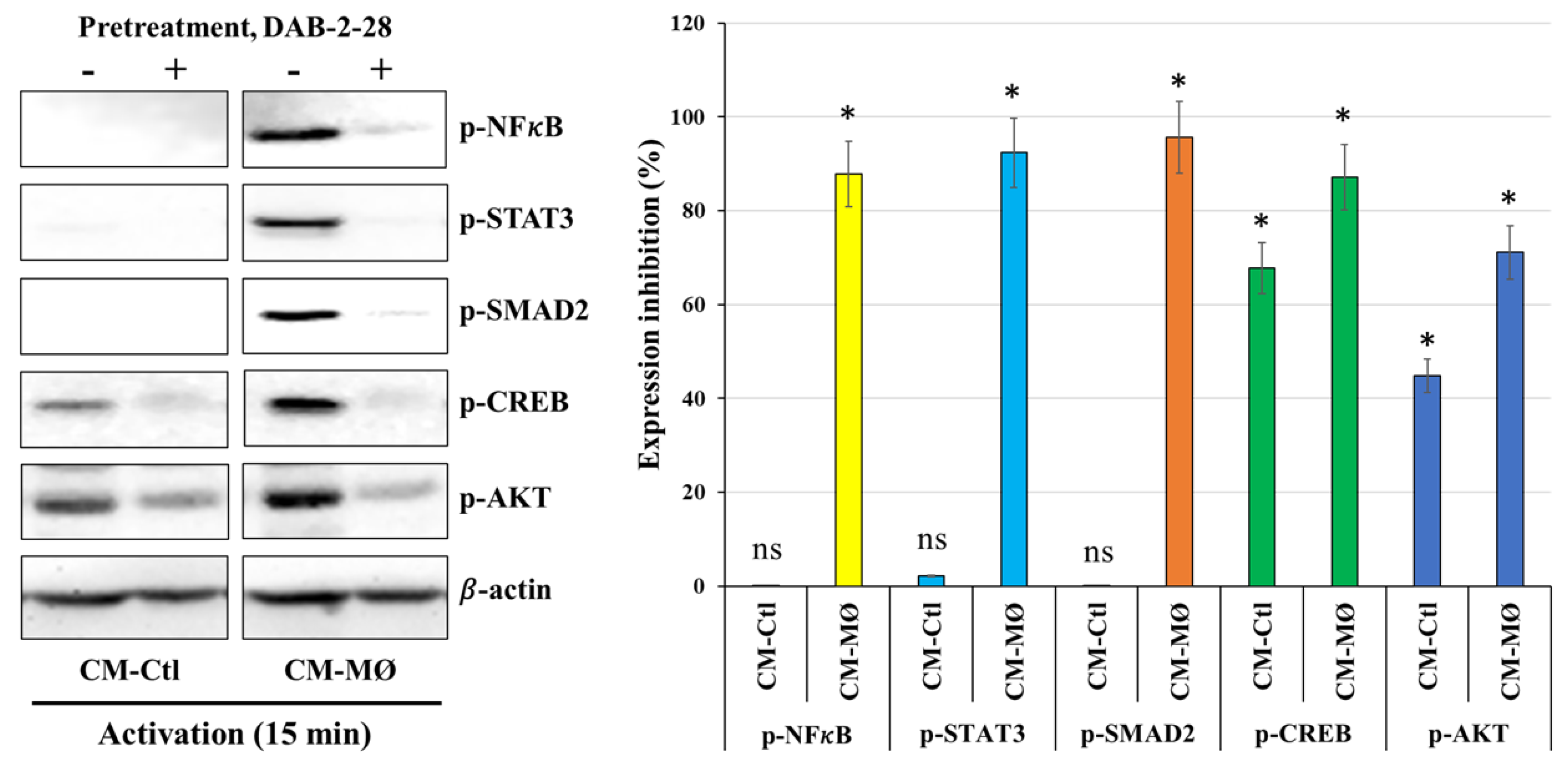

Finally, a signaling study was performed to determine which signaling pathways are affected by DAB-2-28 in MDA-MB-231 cells stimulated with CM-Ctl or CM-MØ. The WB results reported in

Figure 8 indicate that the expression levels of NFκB, STAT3, SMAD2, CREB, and AKT in the phosphorylated form are increased upon activation with CM-MØ compared to CM-Ctl. Furthermore, DAB-2-28 pretreatment inhibits the expression of these phosphorylated proteins. Analysis of CREB and AKT proteins indicates that they are expressed in the active and phosphorylated form in both CM-Ctl and CM-MØ-stimulated cells. However, CREB and AKT protein activation levels are greatly inhibited by pretreatment with 30 μM DAB-2-28 followed by stimulation with MØ-derived factors (

Figure 8).

3. Discussion and Conclusion

Despite advancements in early detection and therapeutic strategies, cancer relapse is still a major limitation and a major cause of reduced patient survival and quality of life [

4], hence the urge to develop better anticancer drugs against primary and metastatic breast cancer. Indeed, compelling studies indicated that EMT and chronic inflammation are interconnected processes [

30] that substantially contribute to the progression and spread of breast tumor cells [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Chronic inflammation, often orchestrated by TAMs, can induce EMT in BC cells, promoting their migration, invasion, and metastasis [

13,

14]. In turn, EMT can also stimulate TAMs and the production of pro-inflammatory factors, creating a positive feedback loop that can significantly accelerate cancer progression and metastasis [

30]. In this context, our data is in line with previous studies showing that macrophage-derived factors, such as IL6, TGFβ1 and TNFα, could be responsible for inducing EMT-related changes in epithelial cancerous cells [

8,

9,

31,

32,

33]. Those changes include activation of pro-EMT transcription factors (Snail, Twist1, ZEB), which are associated with decreased expression of E-cadherin, as well as an increase of tumor invasive potential via MMP2 and/or MMP9 overexpression [

6,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Then, we and others propose that targeting either inflammatory cells and factors or EMT pathways could potentially inhibit the metastatic process in breast cancer.

Small molecules are being investigated as potential therapeutic agents to modulate EMT, particularly in cancer and fibrosis [

34]. Several signaling pathways, such as TGFβ/SMAD, TNFα/NFκB, and IL6/STAT3 are known to regulate EMT [

8,

9,

31,

32,

33]. Some small molecules were identified and characterized for their ability to target EMT-related pathways and processes, mainly in combination therapies. Examples include Trametinib, a MEK inhibitor, in combination with Taselisib, a PI3K inhibitor, and Tivantinib, a Met receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in combination with erlotinib, an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of non–small-cell lung cancer [

35,

36]. Preclinical studies have also showed the effectiveness of targeted small molecule inhibitors in killing cancer cells or preventing tumor growth. For instance, Gleevec, a multiple tyrosine kinases inhibitor, is used in the clinic for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia [

37], and Gefitinib, an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer [

38].

In our laboratories, DABs molecules were originally identified for their anti-inflammatory and antitumor properties [

23,

24]. In further studies using preclinical models of invasive bladder cancer, we demonstrated that optimized DAB-2-28 is the more efficient DAB molecule in reducing the development of tumors. We also demonstrated that DAB-2-28 efficiently inhibits cytokine-induced activation of pro-inflammatory pathways in M1 macrophages and murine bladder cancer cell lines [

25,

26]. Overall, these previous studies offered preclinical proof-of-principle for DAB-2-28 molecule in the treatment of cancer linked to inflammation.

Our fundamental motivation for designing and optimizing DAB molecules is to question whether targeted compounds previously selected to regulate cancer-related inflammation can also be used to effectively inhibit EMT signaling. Here, we provide evidence suggesting that DAB-2-28 may also inhibit EMT initiation or maintenance, since the EMT program is modulated by similar signaling pathways for which this molecule has an efficient inhibitory impact, namely TNFα/NFκB, IL6/STAT3, and TGFβ/SMAD.

Importantly, we have shown that DAB-2-28 negatively regulates the migration and invasion capacities of both MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells in response to macrophage-derived factors, probably by decreasing MMP9 gelatinase activity, and inhibiting activation of the key pro-EMT proteins NFκB, STAT3, AKT, and SMAD2. In fact, by degrading collagens, fibronectin, laminin, and other structural proteins of the extracellular matrix, MMPs play a critical role in mediating EMT and thus stimulating tumor promotion and metastasis [

39]. Considered as attractive therapeutic targets, numerous promising small molecule MMP inhibitors exposing varying degrees of potency and selectivity were discovered [

40]. However, while some of them advanced into clinical trials, they were generally unsuccessful due to poor oral bioavailability, low selectivity among MMP isoforms, or intolerable side effects due to simultaneous inhibition of non-target metalloproteases. Small molecules containing a marcaptoacyl function for MMP catalytic zinc chelation, such as Rebimastat (BMS-275291), is an example of promising MMP2/MMP9 inhibitor that failed to be incorporated into adjuvant therapy due to severe musculoskeletal toxicity showed in a Phase II trial for early breast cancer [

41]. The development of selective MMP inhibitors that are effective against metastatic breast cancer has also been considered. Small molecules pyrimidinetrione-based and bisphosphonic-based MMP inhibitors were shown to reduce primary tumor growth and tumor-induced bone osteolysis in preclinical models of metastatic breast cancer [

42,

43].

In conclusion, chronic inflammation and EMT are closely linked in BC, with each process potentially influencing and exacerbating the other, ultimately contributing to the development of metastatic disease. While promising, the development of safe and effective EMT-targeting drugs continues to face significant challenges but is still an active area of research. From our previous studies, DAB-2-28 has emerged as a new «lead» molecule having the advantage of being more effective than other DABs with a much lower cytotoxic activity, and therefore, it would be more suitable for use as therapeutic agent in a clinical setting. Accordingly, we propose that the diverse antitumoral properties of this small molecule can be exploited therapeutically in humans, especially for patients whose current treatments are unable to prevent tumor relapses, the risk of progression, and even the eradication of recurrent, resistant, and metastatic tumors.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Models

The human breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231, as well as the human monocyte cell line THP-1, were purchased from ATCC (American Type Culture Collection). THP-1 cell line is a widely used model to represent MØs derived from blood monocytes [

23]. Among human breast cancer cell lines, MCF-7 cells are used in breast cancer studies to represent luminal A cancers, differentiated cancer cells that resemble the healthy phenotype of a mammary gland epithelial cell. The MDA-MB-231 cell line represents a more aggressive and invasive TNBC. These cells are more dedifferentiated and resemble a mesenchymal phenotype [

44,

45]. They are used in this study to represent cells that have undergone dedifferentiation toward a mesenchymal phenotype.

4.2. Cell Culture and Reagents

The cells were cultured in complete culture medium consisting of RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM HEPES, and 50 μg/mL gentamicin. The cells were kept in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO

2. All culture media, HBSS (Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution), PBS (Phosphate-buffered saline), serum, and reagents were purchased from Wisent Bioproducts (Saint-Bruno, Canada). As previously described [

25,

26], DAB-2-28 was synthetized using DAB-1 as the starting material in a three-step reaction sequence. DAB-2-28 was initially dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Chemical Company, Oakville, Canada Sigma) to prepare DAB-2-28 stock solutions, which were 1000-fold diluted in PBS before use. Then, a solution of 0.1% DMSO in PBS was used as vehicle.

4.3. Production of Macrophage Conditioned Medium

Conditioned medium from non-activated and activated MØs was produced to stimulate cancer cells in several experiments. First, to differentiate THP-1 monocytes into MØs, the cells were placed in a 6-well plate (3 x 106 cells/well) and treated with 80 ng/mL PMA (phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate; Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) in complete culture medium for 48 h. Subsequently, MØs were polarized toward a pro-inflammatory phenotype with complete culture medium containing 5 ng/mL of IFN-γ and 25 ng/mL of TNF-α (Peprotech Inc., Montreal, Canada) for 24 h. For non-activated MØs, the PMA-containing culture medium was replaced with fresh complete culture medium (without PMA and cytokines). Then, the culture medium was changed to fresh, serum-free medium, in which the cells were incubated for 48 h. After incubation, the supernatant was harvested, yielding the conditioned medium of activated MØs (CM-MØ) and the conditioned medium of non-activated MØs, which served as a control (CM-Ctl).

4.4. Cell Viability Assay (MTT Assay)

MTT assays were performed to evaluate the effect of DAB-2-28, at different concentrations, on cell viability in MCF-7 cells, as previously described. Briefly, cells were plated in 96-well plates (5 × 103 cells/well) and incubated to allow them to adhere. The next day, they were treated with DAB-2-28 for 24 h at concentrations ranging from 2.5 to 90 μM in complete culture medium. Then, the compound MTT (tetrazolium 3,(4,5 dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphennyltetrazolium bromide; Sigma Chemical Company, Oakville, Canada) was added to each well to obtain a final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL, and the plate was incubated for 3 h. During this incubation period, viable cells reduced MTT to purple formazan crystals, which are insoluble in aqueous media. After 3 h of incubation, the supernatant was aspirated and 100 μL of an acidic isopropanol-based solubilization solution was added to each well, solubilizing the crystals and producing a homogeneous solution whose blue color intensity was quantified by colorimetry using a spectrophotometer (Biotek, synergy HT) at a wavelength of 580 nm. In this assay, the optical density is proportional to the number of viable (or metabolically active) cells in each well.

4.5. Colony Formation Assay

A colony formation assay was performed to assess the survival and clonogenic activity of cancer cells in response to MØ-derived factors and the influence of DAB-2-28 on this process [

27]. To do this, cells were first cultured in 24-well plates (1.5 x 10

5 cells/well) and incubated for 48 h in 500 μL of CM-Ctl and CM-MØ diluted 1:3 in complete culture medium. After 48 h of incubation, cells were treated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or DAB-2-28 (30 μM) for 1 h and then harvested and counted. Treated cells were cultured in a 6-well plate (200 cells/well) and incubated for 21 days in complete culture medium (1.5 mL) to allow adhered cells to form colonies. After 3 weeks, colonies were fixed with formalin solution (10% v/v), stained with crystal violet solution (0.01% v/v), and then counted using a phase contrast optical microscope.

4.6. Induction of EMT in MCF-7 Cells

A protocol was developed to induce EMT in MCF-7 cells using macrophage-derivedconditioned media and StemXvivo (EMT inducing media supplement, R&D Systems). StemXvivo is a culture medium supplement specifically designed to induce EMT in several cell lines [

29], including MCF-7 cells. Thus, it was used as an alternative method to induce EMT to compare the effect of MØs-conditioned media. MCF-7 cells were cultured in 6-well plates (1.75 x 10

5 cells/well) and incubated with 1.5 mL of CM-Ctl and CM-MØ diluted 1:3 or StemXvivo and PBS diluted 1:100 with culture medium containing 2.5% FBS, for 7 days, replacing with a fresh dilution on day 4. The evolution of EMT in MCF-7 cells was checked during the experiment by observing cell morphology and pictures were taken by phase contrast microscopy at 20x magnification. After 7 days, cells were harvested by trypsin treatment and lysed in TNE-based lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, pH 8.0), containing 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors. Then, the total concentration of proteins in the cell lysates was measured by colorimetric assay (DC protein assay kit) before immunodetection of proteins of interest by western blot.

4.7. Western Blot

Western blot (WB) was used to confirm the induction of EMT in MCF-7 cells by CM-MØ and to perform signaling studies in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells. Cell lysates were prepared differently depending on the experiment. Proteins in cell lysates were separated in a 10% polyacrylamide gel and then transferred to a PVDF membrane as previously described. Primary antibodies against E-cadherin, Snail1, MMP9, and total (t-) and phosphorylated (p-) form of STAT3, NFκB, AKT, SMAD2, and CREB were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA) and β-actin from Sigma Chemical Company (Oakville, Canada). The secondary antibody (Anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked antibody) was purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). The chemiluminescence solution (SuperSignal West Femto) used to detect the HRP signal was obtained from ThermoFisher Scientific. β-actin was also used as a reference point in densitometric analyses performed to assess the relative expression of the proteins under study by calculating the ratio of the protein of interest to β-actin.

4.7.1. Cell Lysates to Verify EMT Induction

The preparation of cell lysates to verify E-cadherin expression after incubation of cells in CM-MØ is described above (subsection 4.3). The same protocol was followed to verify E-cadherin expression in cells incubated with the cytokines TNFα (25 ng/mL), TGFβ1 (5 ng/mL), and TNFα + TGFβ1 or with StemXvivo reagent (1:100). To verify Snail1 expression, cells were cultured in 24-well plates (2.0 x 105 cells/well) and incubated with CM-Ctl, CM-MØ, PBS, TNFα (25 ng/mL), TGFβ1 (5 ng/mL), TNFα + TGFβ1 or StemXvivo for 6 h. To study MMP9 expression, cells were incubated with CM-Ctl and CM-MØ for 24 h. In some experiments, pretreatment with vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or 30 μM DAB-2-28 for 1 h was performed before incubation with MØ-derived conditioned media or cytokines.

4.7.2. Cell Lysates for Signaling Studies

Cells were cultured in 24-well plates (2.0 x 105 cells/well) for 24 h. Cells were then starved for 3 h in serum-free culture medium before pretreatment with vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or 30 μM DAB-2-28 for 1 h and stimulation with MØ-derived conditioned media, PBS or StemXvivo for 15 min. Cells were directly recovered in 200 μL of 95 ˚C heated lysis buffer containing 1% (v/v) SDS and protease and phosphatase inhibitors. For the preparation of homogeneous cell lysates, β-mercaptoethanol at a final concentration of 10% (v/v) was added and the samples heated to 95 ˚C prior to WB analysis.

4.8. Immunofluorescence

The expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin and the conformation of actin filaments (phalloidin) were observed by immunofluorescence (IF) on MCF-7 cells. Cells (4 × 104 cells/coverslip) were plated on sterile square coverslips placed at the bottom of wells of a 6-well plate. Coverslips were incubated with 1.5 mL of conditioned media of MØs (1:3), PBS or StemXvivo (1:100) diluted in complete culture medium for 7 days, with a change to fresh dilutions on day 4. After 7 days, cells were fixed on the coverslips with 10% formalin for 20 min at room temperature, followed by washing with PBS. Then, the coverslips were incubated with blocking buffer (1X PBS / 5% goat serum / 0.3% Triton X-100) for 1 h and washed with PBS. The coverslips were incubated for 18 h with the primary antibody (anti-E-cadherin, 1:200) diluted in antibody dilution buffer (1X PBS / 1% BSA / 0.3% Triton) and then with the secondary antibody (Anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor conjugate 488, 1:1000) diluted in the same buffer for 30 min. Visualization of actin filaments was performed by incubating cells fixed on the coverslips with the fluorochrome-coupled anti-phalloidin antibody (1:20) diluted in PBS for 20 min. Finally, the coverslips were washed with PBS and slide-mounted with a solution containing DAPI (ProLong Gold Antifade; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), and then observed for image capture with a Leica SP8 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems Inc., Concord, Canada).

4.9. Boyden Chamber Invasion Assay

The effect of DAB-2-28 on the invasive potential of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells stimulated by soluble MØ-derived factors was assessed using a Boyden chamber invasion assay (HTS Transwell System; from Corning, New York, USA), as previously described [

46]. The Boyden chamber consists of an insert that fits inside the wells of a 24-well plate, which contains a polycarbonate filter with 0.4 μM pores. The filter was covered with a layer of BME (Cultrex Basement Membrane Extract, Trevigen, MD, USA) diluted 1:10 (v/v) in serum-free culture medium, which forms a natural extracellular matrix. The BME was left to solidify overnight in a 37 °C incubator, with 500 µL of serum free medium in the lower chamber. The next day, MCF-7 or MDA-MB-231 cells (5 x 10

5 cells in 100 mL of culture media) pretreated during 60 min with vehicle (DMSO 0.1%) or DAB-2-28 (30 µM) were deposited on the BME layer covering the filter, while non-activated and activated MØs (5 x 10

4 cells) were placed at the bottom of the well below the insert. The cells were left to invade for 48 h, after which the top side of the transwell insert, containing the BME and the non-invasive cells, was wiped using a cotton swab. The invasive cells, which were found on the bottom side of the transwell’s polycarbonate membrane, were fixed using a 10% formalin solution. The membrane was then cut out of the transwell insert and mounted on a microslide using the ProLong Gold Antifade mountant with DAPI (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). The slides were observed under fluorescent microscopy (63 x) and five fields were chosen at random for each condition to count the number of invasive cells in each field. The results are presented in the form of a graph, representing the number of invasive cells per field, according to the treatment condition.

4.10. Migration Assay (Wound-Healing Assay)

The effect of DAB-2-28 on the migration potential of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells was studied using wound-healing assays. MCF-7 (1.5 x 105 cells/well) and MDA-MB-231 (2 x 105 cells/well) cells were cultured in a 24-well plate and allowed to adhere for 24 h. When cells reached 70-80% confluency, they were treated with vehicle (DMSO 0.1%) or DAB-2-28 (30 μM) for 60 min. Then, two horizontal wounds were formed using p200 pipette tips, and cell debris was removed by washing twice with HBSS. Then, for MCF-7 cells, the culture medium was replaced with 500 μL of diluted (1:3) CM-Ctl or CM-MØ for 48 h, and for MDA-MB-231 cells with culture medium containing 25 ng/mL with IL6 for 24 h. Pictures of the wounds were taken at t = 0 h and at t = 48 h for MCF-7 cells and at t = 24 h for MDA-MB-231 cells. Images. Wound areas were analyzed and quantified with ImageJ software to calculate the percentage of wound closure.

4.11. Gelatin Zymography

Gelatin zymography was performed to study the impact of DAB-2-28 in the activation level of MMP9 proteases secreted by MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cancer cells in response to MØ-derived factors. First, the cells were cultured in 6-well plates (6.0 x 105 cells/well) and allowed to adhere for 24 h. The next day, the culture medium was replaced with 1.5 mL of diluted (1:3) CM-Ctl or CM-MØ for 48 h Then, the CM was removed, and the cells were pretreated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or 30 μM DAB-2-28 for 1 h. The cells were then washed 3 times with HBSS and incubated with serum-free culture medium. At this step, it is important to wash the cells thoroughly with HBSS so that no trace of FBS remains, as it contains MMPs. After 24 h of incubation, the supernatant was harvested and centrifuged to precipitate cell debris. The proteins in the supernatant were assayed by colorimetry (DC protein assay kit) to analyze the same amount of protein per sample (3 μg of protein). The proteins from the samples were then fractionated on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, containing 1% porcine gelatin. After separation, the acrylamide gel was recovered and washed twice (30 min) with washing buffer. The gel was then placed in incubation buffer for 18 h in a 37 °C incubator with shaking to allow the gelatinases to degrade the gelatin in the gel. The gel was finally stained with a Coomassie blue solution until it turned blue, then destained with a destaining solution until clear bands appeared. The destained bands correspond to the locations where the gelatin had been degraded by the hydrolytic activity of the proteases MMP-2 and MMP9, for which gelatin is the specific substrate. The MMPs were then identified based on their molecular weight, by the height of the degraded gelatin bands, using the molecular weight marker as a reference point. The gel image was then captured using a white light transilluminator, allowing for better visualization of the degraded gelatin bands, which appeared as white bands against the blue background of the stained gel.

4.12. Statistical Analyses

Data obtained from the experiments are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism software, version 9.4 (GraphPad). Means were obtained from at least three independent experiments, and the difference between groups was analyzed using a one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey post-test. Statistical differences were considered significant at a p-value < 0.05.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.R.M. and G.B.; methodology, C.R.M., G.B., L.F., and Y.O.; validation, L.F., Y.O., and J.G.; formal analysis, C.R.M., I.P., and L.F.; investigation, L.F., J.G., and Y.O.; resources, J.G.; writing—original draft preparation, L.F. and C.R.M.; writing—review and editing, C.R.M., L.F., I.P., and G.B.; supervision, C.R.M., and G.B.; project administration, C.R.M.; funding acquisition, C.R.M., and G.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Cancer Research Society (CRS: number 22471) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR; number 392334). This work was also sponsored by a grant from Aligo Innovation (number 150923), and the “Ministère de l’Économie et de l’Innovation”, Québec Government to C. Reyes-Moreno and G. Bérubé.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The human breast cancer cell lines, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231, and the human monocytic cell line THP-1 were obtained from ATCC (Rockville, MD, USA).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec (FRSQ) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) for financial support (M.Sc. scholarship) to L. Fortin and Y. Oufqir, respectively.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BC |

Breast cancer |

| CM |

Conditioned media |

| Ctl |

Control |

| DMSO |

Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| EMT |

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

| IF |

Immunofluorescence |

| MØ |

Macrophage |

| MMPs |

Matrix metalloproteases |

| PBS |

Phosphate-buffered saline |

| TAMs |

Tumor-associated macrophages |

| TNBC |

Triple negative breast cancer |

| WB |

Western blot |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.A. The clinical behavior of different molecular subtypes of breast cancer. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2021, 29, 100469. [CrossRef]

- Burguin, A.; Diorio, C.; Durocher, F. Breast Cancer Treatments: Updates and New Challenges. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 808. [CrossRef]

- Westphal, T.; Gampenrieder, S.P.; Rinnerthaler, G.; Greil, R. Cure in metastatic breast cancer. memo - Magazine of European Medical Oncology, 2018, 11, 172-179. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Harper, A.; McCormack, V.; Sung, H.; Houssami, N.; Morgan, E.; Mutebi, M.; Garvey, G.; Soerjomataram, I.; Fidler-Benaoudia, M.M. Global patterns and trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality across 185 countries. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1154–1162. [CrossRef]

- Dongre, A.; Weinberg, R.A. New insights into the mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and implications for cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 69–84. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hong, W.; Wei, X. The molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies of EMT in tumor progression and metastasis. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Danforth, D.N. The Role of Chronic Inflammation in the Development of Breast Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 3918. [CrossRef]

- Famta, P.; Shah, S.; Dey, B.; Kumar, K.C.; Bagasariya, D.; Vambhurkar, G.; Pandey, G.; Sharma, A.; Srinivasarao, D.A.; Kumar, R.; et al. Despicable role of epithelial–mesenchymal transition in breast cancer metastasis: Exhibiting de novo restorative regimens. Cancer Pathog. Ther. 2024, 3, 30–47. [CrossRef]

- Fedele, M.; Cerchia, L.; Chiappetta, G. The Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Breast Cancer: Focus on Basal-Like Carcinomas. Cancers 2017, 9, 134. [CrossRef]

- Lima, J.F.; Nofech-Mozes, S.; Bayani, J.; Bartlett, J.M.S. EMT in Breast Carcinoma—A Review. J. Clin. Med. 2016, 5, 65. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Sarkissyan, M.; Vadgama, J.V. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Breast Cancer. J Clin Med, 2016, 5. [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Marchesi, F.; Di Mitri, D.; Garlanda, C. Macrophage diversity in cancer dissemination and metastasis. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2024, 21, 1201–1214. [CrossRef]

- Stavrou, M.; Constantinidou, A. Tumor associated macrophages in breast cancer progression: implications and clinical relevance. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1441820. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-W.; Xia, W.; Huo, L.; Lim, S.-O.; Wu, Y.; Hsu, J.L.; Chao, C.-H.; Yamaguchi, H.; Yang, N.-K.; Ding, Q.; et al. Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition Induced by TNF-α Requires NF-κB–Mediated Transcriptional Upregulation of Twist1. Cancer research, 2012, 72, 1290-1300. [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Li, R.; Han, M. Tumor-associated macrophages induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition and promote lung metastasis in breast cancer by activating the IL-6/STAT3/TGM2 axis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 143, 113387. [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.; Srinivasarao, D.A.; Famta, P.; Shah, S.; Vambhurkar, G.; Shahrukh, S.; Singh, S.B.; Srivastava, S. The portrayal of macrophages as tools and targets: A paradigm shift in cancer management. Life Sci. 2023, 316, 121399. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, B.P. TNF-α/NF-κB/Snail pathway in cancer cell migration and invasion. British Journal of Cancer, 2010, 102, 639-644. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Fang, Z.; Ma, J. Regulatory mechanisms and clinical significance of vimentin in breast cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 133, 111068. [CrossRef]

- Strouhalova, K.; Přechová, M.; Gandalovičová, A.; Brábek, J.; Gregor, M.; Rosel, D. Vimentin Intermediate Filaments as Potential Target for Cancer Treatment. Cancers 2020, 12, 184. [CrossRef]

- Gyamfi, J.; Lee, Y.H.; Eom, M.; Choi, J. Author Correction: Interleukin-6/STAT3 signalling regulates adipocyte induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer cells (Scientific Reports, (2018), 8, 1, (8859). Scientific reports, 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, N.J.; Sasser, A.K.; E Axel, A.; Vesuna, F.; Raman, V.; Ramirez, N.; Oberyszyn, T.M.; Hall, B.M. Interleukin-6 induces an epithelial–mesenchymal transition phenotype in human breast cancer cells. Oncogene 2009, 28, 2940–2947. [CrossRef]

- Hamelin-Morrissette, J.; Cloutier, S.; Girouard, J.; Belgorosky, D.; Eiján, A.M.; Legault, J.; Reyes-Moreno, C.; Bérubé, G. Identification of an anti-inflammatory derivative with anti-cancer potential: The impact of each of its structural components on inflammatory responses in macrophages and bladder cancer cells. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 96, 259–268. [CrossRef]

- Girouard, J.; Belgorosky, D.; Hamelin-Morrissette, J.; Boulanger, V.; D'ORio, E.; Ramla, D.; Perron, R.; Charpentier, L.; Van Themsche, C.; Eiján, A.M.; et al. Molecular therapy with derivatives of amino benzoic acid inhibits tumor growth and metastasis in murine models of bladder cancer through inhibition of TNFα/NFΚB and iNOS/NO pathways. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 176, 113778. [CrossRef]

- Cloutier, F.; Oufqir, Y.; Fortin, L.; Leclerc, M.-F.; Girouard, J.; Tajmir-Riahi, H.-A.; Reyes-Moreno, C.; Bérubé, G. Design of novel 4-maleimidylphenyl-hydrazide molecules displaying anti-inflammatory properties: Refining the chemical structure. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2022, 5. [CrossRef]

- Oufqir, Y.; Fortin, L.; Girouard, J.; Cloutier, F.; Cloutier, M.; Leclerc, M.-F.; Belgorosky, D.; Eiján, A.M.; Bérubé, G.; Reyes-Moreno, C. Synthesis of new para-aminobenzoic acid derivatives, in vitro biological evaluation and preclinical validation of DAB-2-28 as a therapeutic option for the treatment of bladder cancer. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2022, 6. [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, C.; Bagga, M.; Kaur, A.; Westermarck, J.; Abankwa, D.; Rota, R. ColonyArea: An ImageJ Plugin to Automatically Quantify Colony Formation in Clonogenic Assays. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e92444. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Antin, P.; Berx, G.; Blanpain, C.; Brabletz, T.; Bronner, M.; Campbell, K.; Cano, A.; Casanova, J.; Christofori, G.; et al. Guidelines and definitions for research on epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2020, 21, 341-352. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Herr, G.; Johnson, W.; Resnik, E.; Aho, J. Induction and analysis of epithelial to mesenchymal transition. J Vis Exp, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Carmona, M.; Lesage, J.; Cataldo, D.; Gilles, C. EMT and inflammation: inseparable actors of cancer progression. Mol. Oncol. 2017, 11, 805–823. [CrossRef]

- Scimeca, M.; Antonacci, C.; Colombo, D.; Bonfiglio, R.; Buonomo, O.C.; Bonanno, E. Emerging prognostic markers related to mesenchymal characteristics of poorly differentiated breast cancers. Tumor Biol. 2015, 37, 5427–5435. [CrossRef]

- Stavrou, M.; Constantinidou, A. Tumor associated macrophages in breast cancer progression: implications and clinical relevance. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1441820. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, M.; Yin, J.; Li, P.; Zeng, S.; Zheng, G.; He, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, F.; et al. Tumor-associated macrophages promote epithelial–mesenchymal transition and the cancer stem cell properties in triple-negative breast cancer through CCL2/AKT/β-catenin signaling. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 20, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Chen, D.; Vaziri, N.D.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, Y. Small molecule inhibitors of epithelial-mesenchymal transition for the treatment of cancer and fibrosis. Med. Res. Rev. 2019, 40, 54–78. [CrossRef]

- Sato, H.; Yamamoto, H.; Sakaguchi, M.; Shien, K.; Tomida, S.; Shien, T.; Ikeda, H.; Hatono, M.; Torigoe, H.; Namba, K.; et al. Combined inhibition of MEK and PI3K pathways overcomes acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2018, 109, 3183–3196. [CrossRef]

- Scagliotti, G.; Pawel, J.v.; Novello, S.; Ramlau, R.; Favaretto, A.; Barlesi, F.; Akerley, W.; Orlov, S.; Santoro, A.; Spigel, D.; et al. Phase III Multinational, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Tivantinib (ARQ 197) Plus Erlotinib Versus Erlotinib Alone in Previously Treated Patients With Locally Advanced or Metastatic Nonsquamous Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2015, 33, 2667-2674. [CrossRef]

- Hochhaus, A.; Druker, B.; Sawyers, C.; Guilhot, F.; Schiffer, C.A.; Cortes, J.; Niederwieser, D.W.; Gambacorti-Passerini, C.; Stone, R.M.; Goldman, J.; et al. Favorable long-term follow-up results over 6 years for response, survival, and safety with imatinib mesylate therapy in chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia after failure of interferon-α treatment. Blood, 2008, 111, 1039-1043. [CrossRef]

- Mok, T.S.; Wu, Y.-L.; Thongprasert, S.; Yang, C.-H.; Chu, D.-T.; Saijo, N.; Sunpaweravong, P.; Han, B.; Margono, B.; Ichinose, Y.; et al. Gefitinib or Carboplatin–Paclitaxel in Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 947–957. [CrossRef]

- Khalili-Tanha, G.; Radisky, E.S.; Radisky, D.C.; Shoari, A. Matrix metalloproteinase-driven epithelial-mesenchymal transition: implications in health and disease. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.J. Matrix metalloproteinases as therapeutic targets in breast cancer. Front. Oncol. 2023, 12, 1108695. [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.D.; Saphner, T.J.; Waterhouse, D.M.; Chen, T.-T.; Rush-Taylor, A.; Sparano, J.A.; Wolff, A.C.; Cobleigh, M.A.; Galbraith, S.; Sledge, G.W. A Randomized Phase II Feasibility Trial of BMS-275291 in Patients with Early Stage Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 1971–1975. [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Huang, D.; Blick, T.; Connor, A.; Reiter, L.A.; Hardink, J.R.; Lynch, C.C.; Waltham, M.; Thompson, E.W.; Bogyo, M. An MMP13-Selective Inhibitor Delays Primary Tumor Growth and the Onset of Tumor-Associated Osteolytic Lesions in Experimental Models of Breast Cancer. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e29615. [CrossRef]

- Tauro, M.; Shay, G.; Sansil, S.S.; Laghezza, A.; Tortorella, P.; Neuger, A.M.; Soliman, H.; Lynch, C.C. Bone-Seeking Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 Inhibitors Prevent Bone Metastatic Breast Cancer Growth. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 494–505. [CrossRef]

- Boon Yin, K., The Mesenchymal-Like Phenotype of the MDA-MB-231 Cell Line. 2011.

- Eiden, C.; Ungefroren, H. The Ratio of RAC1B to RAC1 Expression in Breast Cancer Cell Lines as a Determinant of Epithelial/Mesenchymal Differentiation and Migratory Potential. Cells 2021, 10, 351. [CrossRef]

- Dufresne, M.; Dumas, G.; Asselin, É.; Carrier, C.; Pouliot, M.; Reyes-Moreno, C. Pro-inflammatory type-1 and anti-inflammatory type-2 macrophages differentially modulate cell survival and invasion of human bladder carcinoma T24 cells. Mol. Immunol. 2011, 48, 1556–1567. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Effects of DAB-2-28 on MCF-7 cell viability and survival. (A) Representative dose-response curve using MTT cell proliferation assay and IC50 calculation using different doses of DAB-2-28 (2.5–90 μM). (B) Representative images and graphical analysis of the number of colonies formed after 21 days of incubation. Colonies were stained with crystal violet and counted. * p < 0.01 denotes a significant difference between the cell groups.

Figure 1.

Effects of DAB-2-28 on MCF-7 cell viability and survival. (A) Representative dose-response curve using MTT cell proliferation assay and IC50 calculation using different doses of DAB-2-28 (2.5–90 μM). (B) Representative images and graphical analysis of the number of colonies formed after 21 days of incubation. Colonies were stained with crystal violet and counted. * p < 0.01 denotes a significant difference between the cell groups.

Figure 2.

Effects of macrophage-derived factors on cell morphology and E-cadherin and Snail1 expression by MCF-7 cells. (A, B) Representative images of cell morphology changes assessed by phase-contrast microscopy (Days 3 and 7) and immunofluorescence (Day 7) after cell incubation with CM-Ctl or CM-MØ. (C) E-cadherin expression by immunofluorescence after incubation of cells with CM-Ctl or CM-MØ for 7 days. (D, E) Representative images and densitometric analyses of E-cadherin (E-Cad) and Snail1 expression in MCF-7 cells stimulated with controls (CM-Ctl or PBS), CM-MØ, TNFα, TGF-β, or TNF-α + TGF-β, for 7 days for E-cadherin, and 6 h for Snail1. Data are expressed as fold induction or fold inhibition compared to controls. * p < 0.01 denotes significant differences compared to controls (CM-Ctl or PBS).

Figure 2.

Effects of macrophage-derived factors on cell morphology and E-cadherin and Snail1 expression by MCF-7 cells. (A, B) Representative images of cell morphology changes assessed by phase-contrast microscopy (Days 3 and 7) and immunofluorescence (Day 7) after cell incubation with CM-Ctl or CM-MØ. (C) E-cadherin expression by immunofluorescence after incubation of cells with CM-Ctl or CM-MØ for 7 days. (D, E) Representative images and densitometric analyses of E-cadherin (E-Cad) and Snail1 expression in MCF-7 cells stimulated with controls (CM-Ctl or PBS), CM-MØ, TNFα, TGF-β, or TNF-α + TGF-β, for 7 days for E-cadherin, and 6 h for Snail1. Data are expressed as fold induction or fold inhibition compared to controls. * p < 0.01 denotes significant differences compared to controls (CM-Ctl or PBS).

Figure 3.

Effects of DAB-2-28 on Snail1 and E-cadherin expression induced by macrophage-derived factors in MCF-7 cells. Representative images and graphical analyses of E-cadherin (A) and (B) Snail1 expression observed by western blot in MCF-7 cells pretreated with 30 μM DAB-2-28 for 1 h and stimulated with CM-MØ for 7 days to assess E-cadherin (E-Cad) expression, or for 6 h to assess Snail1 expression. * p < 0.05 denotes a significant difference between CM-Ctl and CM-MØ. ns: non-significant difference of DAB-2-28 compared to DMSO.

Figure 3.

Effects of DAB-2-28 on Snail1 and E-cadherin expression induced by macrophage-derived factors in MCF-7 cells. Representative images and graphical analyses of E-cadherin (A) and (B) Snail1 expression observed by western blot in MCF-7 cells pretreated with 30 μM DAB-2-28 for 1 h and stimulated with CM-MØ for 7 days to assess E-cadherin (E-Cad) expression, or for 6 h to assess Snail1 expression. * p < 0.05 denotes a significant difference between CM-Ctl and CM-MØ. ns: non-significant difference of DAB-2-28 compared to DMSO.

Figure 4.

Effects of DAB-2-28 on the invasive potential and motility of MCF-7 cells stimulated by macrophage-derived factors. (A) Graphical analysis representing the number of invasive cells per field, when cells were pretreated for 1 h with DMSO or DAB-2-28 (30 μM) and stimulated in coculture with non-activated (na-MØ) or activated (a-MØ) macrophages during 48 h. (B) Graphical analyses of cell migration assays performed with MCF-7 cells pretreated with DMSO or DAB-2-28 (30 μM) for 1 h, and stimulated with CM-Ctl and CM-MØ during 48 h. (C and D) Representative images and graphical analysis of gelatin zymography and western immunoblotting assays to assess, respectively, the activation and the expression of the matrix metalloproteinase MMP9. MCF-7 cells were pretreated with DMSO or DAB-2-28 (30 μM) for 1 h and stimulated with CM-Ctl or CM-MØ during 24 h. * p < 0.01 denotes a significant difference between the cell groups.

Figure 4.

Effects of DAB-2-28 on the invasive potential and motility of MCF-7 cells stimulated by macrophage-derived factors. (A) Graphical analysis representing the number of invasive cells per field, when cells were pretreated for 1 h with DMSO or DAB-2-28 (30 μM) and stimulated in coculture with non-activated (na-MØ) or activated (a-MØ) macrophages during 48 h. (B) Graphical analyses of cell migration assays performed with MCF-7 cells pretreated with DMSO or DAB-2-28 (30 μM) for 1 h, and stimulated with CM-Ctl and CM-MØ during 48 h. (C and D) Representative images and graphical analysis of gelatin zymography and western immunoblotting assays to assess, respectively, the activation and the expression of the matrix metalloproteinase MMP9. MCF-7 cells were pretreated with DMSO or DAB-2-28 (30 μM) for 1 h and stimulated with CM-Ctl or CM-MØ during 24 h. * p < 0.01 denotes a significant difference between the cell groups.

Figure 5.

Effect of DAB-2-28 on the activation of pro-tumor signaling pathways induced by macrophage-derived factors in MCF-7 cells. Representative images and graphical analyses of selected pro-tumor and pro-TEM signaling pathways immunodetected by WB. Cells were pretreated with DAB-2-28 or DMSO for 1 h and activated with CM-Ctl or CM-MØ for 15 min. Representative images of total protein expression are not shown to simplify the figure. The graph represents the relative expression inhibition of each phosphorylated protein induced under DAB-2-28 treatment compared to DMSO. * p < 0.05 denotes significant differences between control DMSO (-) and DAB-2-28 (+).

Figure 5.

Effect of DAB-2-28 on the activation of pro-tumor signaling pathways induced by macrophage-derived factors in MCF-7 cells. Representative images and graphical analyses of selected pro-tumor and pro-TEM signaling pathways immunodetected by WB. Cells were pretreated with DAB-2-28 or DMSO for 1 h and activated with CM-Ctl or CM-MØ for 15 min. Representative images of total protein expression are not shown to simplify the figure. The graph represents the relative expression inhibition of each phosphorylated protein induced under DAB-2-28 treatment compared to DMSO. * p < 0.05 denotes significant differences between control DMSO (-) and DAB-2-28 (+).

Figure 6.

Effect of DAB-2-28 on StemXvivo-induced TEM parameters in MCF-7 cells. (A) Representative images of F-actin (phalloidin; red), and E-cadherin (E-Cad) expression assessed by immunofluorescence after cell incubation with StemXvivo reagent. (B, C) Representative images and graphical analyses of E-Cad and Snail1 expression in MCF-7 cells stimulated with PBS or StemXvivo reagent. Cells were incubated for 6 hours for Snail1 and 7 days for E-cadherin. Data are expressed as fold inhibition or fold induction compared to PBS. * p < 0.01; StemXvivo versus PBS. D) Representative images and graphical analyses showing the effect of DAB-2-28 on StemXvivo-induced activation of pro-tumor signaling pathways in MCF-7 cells. The graph represents the relative expression inhibition of each phosphorylated protein induced under DAB-2-28 treatment compared to DMSO. Phosphorylated proteins for which there is no induction are not plotted. * p < 0.05 denotes significant differences be-tween control DMSO (-) and DAB-2-28 (+).

Figure 6.

Effect of DAB-2-28 on StemXvivo-induced TEM parameters in MCF-7 cells. (A) Representative images of F-actin (phalloidin; red), and E-cadherin (E-Cad) expression assessed by immunofluorescence after cell incubation with StemXvivo reagent. (B, C) Representative images and graphical analyses of E-Cad and Snail1 expression in MCF-7 cells stimulated with PBS or StemXvivo reagent. Cells were incubated for 6 hours for Snail1 and 7 days for E-cadherin. Data are expressed as fold inhibition or fold induction compared to PBS. * p < 0.01; StemXvivo versus PBS. D) Representative images and graphical analyses showing the effect of DAB-2-28 on StemXvivo-induced activation of pro-tumor signaling pathways in MCF-7 cells. The graph represents the relative expression inhibition of each phosphorylated protein induced under DAB-2-28 treatment compared to DMSO. Phosphorylated proteins for which there is no induction are not plotted. * p < 0.05 denotes significant differences be-tween control DMSO (-) and DAB-2-28 (+).

Figure 7.

Effects of macrophage-derived factors and DAB-2-28 on cell invasion and motility, as well as on MMP9 activation and expression in MDA-MB-231 cells. (A) Graphical analysis representing the number of invasive cells per field, when cells were pretreated for 1h with DMSO or DAB-2-28 (30 μM) and stimulated in coculture with non-activated (na-MØ) or activated (a-MØ) macrophages during 48 h. (B) Graphical analyses of cell migration assays performed with MCF-7 cells pretreated with DMSO or DAB-2-28 (30 μM) for 1 h, and stimulated with 25 ng/mL IL6 during 24 h. (C and D) Representative images of gelatin zymography and western immunoblotting assays to assess, respectively, the activation and the expression of matrix metalloproteinase MMP9. MDA-MB-231 cells were pretreated with DMSO or DAB-2-28 (30 μM) for 1h and stimulated with CM-Ctl or CM-MØ for 24h. * p < 0.01 denotes a significant difference between the cell groups.

Figure 7.

Effects of macrophage-derived factors and DAB-2-28 on cell invasion and motility, as well as on MMP9 activation and expression in MDA-MB-231 cells. (A) Graphical analysis representing the number of invasive cells per field, when cells were pretreated for 1h with DMSO or DAB-2-28 (30 μM) and stimulated in coculture with non-activated (na-MØ) or activated (a-MØ) macrophages during 48 h. (B) Graphical analyses of cell migration assays performed with MCF-7 cells pretreated with DMSO or DAB-2-28 (30 μM) for 1 h, and stimulated with 25 ng/mL IL6 during 24 h. (C and D) Representative images of gelatin zymography and western immunoblotting assays to assess, respectively, the activation and the expression of matrix metalloproteinase MMP9. MDA-MB-231 cells were pretreated with DMSO or DAB-2-28 (30 μM) for 1h and stimulated with CM-Ctl or CM-MØ for 24h. * p < 0.01 denotes a significant difference between the cell groups.

Figure 8.

Effect of macrophage-derived factors and DAB-2-28 on the activation of pro-tumor signaling pathways in MDA-MB-231 cells. Representative images and graphical analyses of selected pro-tumor signaling pathways immunodetected by WB. Cells were pretreated with DAB-2-28 or DMSO for 1 h and activated with CM-Ctl or CM-MØ for 15 min. Representative images of total protein expression are not shown to simplify the figure. The graph represents the relative expression inhibition of each phosphorylated protein induced under DAB-2-28 treatment compared to DMSO. * p < 0.05 denotes significant differences between control DMSO (-) and DAB-2-28 (+).

Figure 8.

Effect of macrophage-derived factors and DAB-2-28 on the activation of pro-tumor signaling pathways in MDA-MB-231 cells. Representative images and graphical analyses of selected pro-tumor signaling pathways immunodetected by WB. Cells were pretreated with DAB-2-28 or DMSO for 1 h and activated with CM-Ctl or CM-MØ for 15 min. Representative images of total protein expression are not shown to simplify the figure. The graph represents the relative expression inhibition of each phosphorylated protein induced under DAB-2-28 treatment compared to DMSO. * p < 0.05 denotes significant differences between control DMSO (-) and DAB-2-28 (+).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).