1. Introduction

Denture stomatitis is a common inflammatory condition affecting the mucosa underlying complete dentures and, in some populations, has been found in up to two-thirds of denture wearers [

1,

2]. This multifactorial condition results from factors such as poor oral hygiene, immunosuppression, and microbial activity, namely Candida albicans [

3,

4]. Previous studies have explored adding various antifungal agents to the surface or incorporating them into the denture base itself [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Recently, a study found that the addition of small amounts of organo-selenium (0.5%) into poly methyl methacrylate (PMMA) denture base did indeed act as an antifungal agent by inhibiting C. albicans biofilm formation and growth [

18]. Organoselenium is a biocidal agent that functions through the catalytic generation of superoxide radicals (O2 •−) from the oxidation of thiols [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. These radicals have been shown to inhibit microbial biofilms in bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus, and recently C. albicans [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. These biofilms play a key role in the development of denture stomatitis.

The cause of denture stomatitis is multifactorial and affects a large percentage of people wearing complete dentures [

24]. Poor denture hygiene, poor fit, and continuous wearing of the denture can lead to denture plaque and the accumulation of biofilm, causing an inflammatory and erythematous mucosal response of the denture-bearing areas. In a small population of denture wearers, symptoms such as pain, itching, or a burning sensation due to denture stomatitis can occur [

24]. Although denture stomatitis is multifactorial and there are no clear cause-and-effect relationships, C. albicans has been identified as the major causative microbial agent [

25].

To prevent or treat denture stomatitis, many factors must be assessed to account for its multifactorial causes. Practices such as removing dentures at night, maintaining oral and denture hygiene are important. Another important factor to address is the fit of the denture, as an ill-fitting and poorly fabricated denture can be irritating to the mucosa, causing inflammation and ulcerations.

Denture bases should exhibit certain material properties, including: they must be biocompatible (nontoxic or irritating); they must have adequate physical properties (low solubility, low sorption of oral fluids, good thermal conductivity, and high abrasion, creep and craze resistance); and they must have adequate mechanical properties (high flexural, transverse, and impact strength, high modulus of elasticity, long fatigue life, and low density). The most used denture base material is poly methyl methacrylate (PMMA), although it still has limitations [

26]. PMMA is polymerized through addition polymerization mediated by free radicals to produce the denture base. To obtain a free radical, an activator such as heat, chemicals, light, or electromagnetic radiation must excite the initiator. The initiator sets off a cascade of events that lead to polymerization, resulting in a product that can be post-processed, finished, and polished for delivery to a patient. Through the various steps and materials that are used when processing PMMA, it has the potential to be harmful not only to the patient but the technician. The processing protocol of PMMA should be strictly followed to avoid unfavorable outcomes such as biodegradation in the oral cavity or release of residual monomer. Since the 1940s, PMMA has been the most used denture base material and has demonstrated the ability to withstand the complexity of the oral environment [

26]. Care must be taken if any alterations or additions are made to PMMA to maintain its successful capabilities.

Treatment of denture stomatitis is a process that involves identifying the risk factors and recognizing the signs and symptoms, followed by initial and definitive management [

27]. Patients presenting with edematous, inflamed mucosa should be carefully examined to assess oral hygiene practices and determine whether there are any contributory medical conditions or medications. Initial management includes patient education on prevention, and oral and prosthesis care. Definitive treatment includes the prescription of antifungals to combat the presence of Candida within the oral cavity and the prosthesis should be disinfected or replaced. These interventions can alter the environment in which Candida flourishes, thereby reducing the possibility of developing denture stomatitis. The prescriptions of antifungals that inhibit the growth of the fungi have been successful in the past, but patient compliance is necessary. An agent that could be incorporated into the PMMA denture base that inhibits the growth of C. albicans, is desirable. A study completed in 2021, by AlMojel et al, found that the incorporation and application of 0.5% and 1% organoselenium in and on heat-polymerized PMMA disks inhibited the growth of C. albicans biofilm [

19]. It has been proven that the incorporation of such compounds into PMMA denture bases has promising antimicrobial properties. But, it has yet to be studied how the addition of organoselenium affects the mechanical and physical properties of PMMA.

If a biofilm-inhibiting denture base that retains its physical properties can be formulated, denture stomatitis could be drastically reduced in patients. The prevalence of this inflammatory condition ranges from 15 to 70% among denture wearers [

5], and prevention is key.

Since organoselenium has been proven to be a useful antifungal and has been shown to successfully inhibit the growth and formation of C. albicans, this study aims to elucidate its effects on PMMA denture base material properties. If the antifungal works but the denture base becomes more prone to fracture or there are alterations in its structural capabilities, then the usefulness of organoselenium becomes clinically insignificant. The null hypothesis is that the incorporation of organoselenium into the PMMA denture base would negatively affect its physical and mechanical properties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples Production and Experimental Grouping

PMMA samples were fabricated following ANSI/ADA specification No. 12 for denture base polymer (Lucitone – Dentsply Sirona). Using baseplate wax 141, samples with the following dimensions were created: a width of 10mm, a length of 22mm, and a thickness of 2mm. The wax samples were flasked and invested using type III dental stone. The wax was boiled out, leaving a mold within the flasked dental stone. A thin layer of separating medium was applied to the stone and allowed to dry. Heat-polymerized acrylic resin Lucitone 199 powder and monomer were mixed according to the manufacturer's instructions3. 0% (control), 0.5%, and 1.0% organoselenium concentrations were incorporated into the monomer before mixing it into the powder. Acrylic was packed into the mold cavity after reaching the doughy stage, followed by trial packing. After packing was finished, processing was completed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, 1 ½ hours in water at 163° ± 2°F (73°C ± 1°C), followed by 1/2 hour in boiling water at 212°C. After processing was completed, post-processing steps included trimming away the excess acrylic from the edges of each sample, and then the samples were sonicated in an ultrasonic bath with water to remove any stone debris. The samples were then stored in room temperature water to avoid desiccation until used.

Following fabrication, the samples were randomly into 3 groups, 0%, 0.5%, and 1% organoselenium, with 47 samples in each. Within each group, 22 samples were used to measure flexural stress and elastic modulus, 22 samples for microhardness, and 3 samples for scanning electron microscopic (SEM) examination.

2.2. Flexural Stress and Elastic Modulus

An Instron machine (Instron, Norwood, MA, USA) was used to perform the 3-point bend test. 22 samples from each group (0%, 0.5%, 1.0% organoselenium) were used. Each sample was positioned 20 mm apart over the supports, and a 196 N load was applied with the mode set at 1 mm/min crosshead speed until fracture or dismounting from the supports [

6]. The flexural stress as well as the elastic modulus was recorded.

2.3. Microhardness Test

Each of the 22 samples from one group (0%, 0.5%, 1.0% organoselenium) was secured and placed on the microhardness tester. Three indentations were made using a Vicker’s diamond under a 50 g load applied for 15 seconds, the indentations spaced 100 µm apart from each other. Then the dimensions of each indentation were measured and averaged for each sample [

28].

2.4. Scanning Electron Microscope Examination

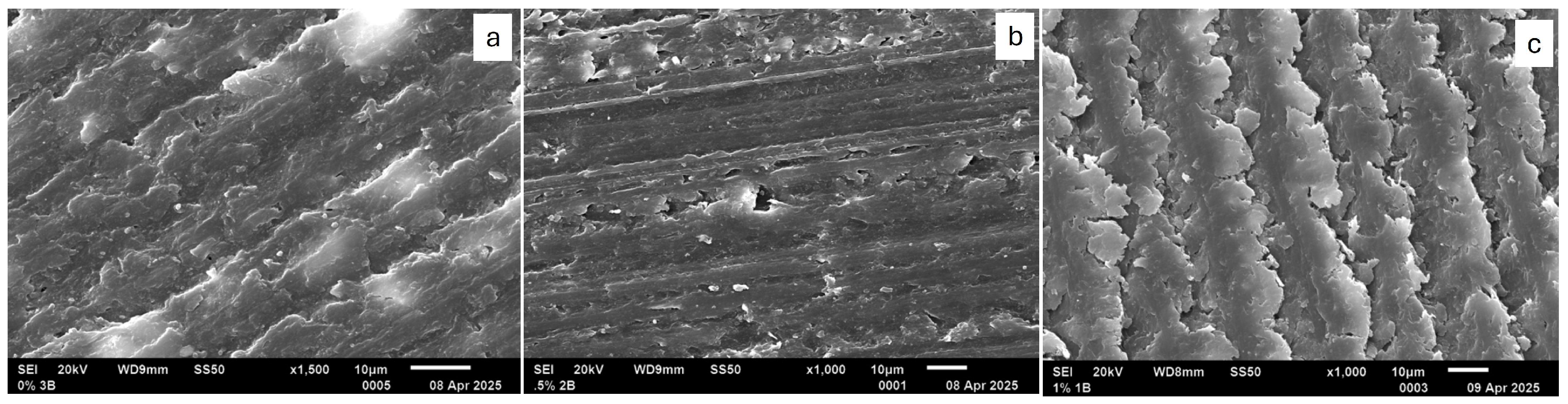

Three samples from each group (0%, 0.5%, 1.0% organoselenium) were prepared by cross-sectioning them in order to view the internal layers of the PMMA denture material and to mount for SEM. The sectioned samples were then sonicated to remove any cutting debris. The samples were dried and mounted for SEM. Each sample was then gold-sputter-coated. The mounted samples were inserted into the SEM and images were captured (JCM-5700; JEOL Ltd, Peabody, MA, USA) for each sample under a magnification of x1000 to analyze the smooth surface and cross-sectional topography for smoothness, porosities, and voids. After collecting the SEM images, each was shown to three isolated persons, having them analyze the data and give their feedback on what they see.

2.5. Sample Size and Power Calculation

A power analysis was conducted to determine the sample size. To have an 80% power to detect a significant difference between the control, 0.5%, and 1% organoselenium concentration with an alpha value of 0.05 and an effect size of 0.40 (large), a sample size of 22 for each subgroup (0%, 0.5%, 1.0% organoselenium) was needed for the outcome measurement. However, 25 samples were used for each group to account for damage during processing.

3. Results

Although measures were taken to maintain the exact sizes for each sample, due to the nature of the heat compression molding technique and material, there were slight variations in sample sizes. There was a statistically significant difference [F(2, 68) = 1074.48, p<.001] in flexural stress among the three groups (

Figure 1). Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated that the mean flexural stress for the 0% group (90.89±6.86) was statistically significantly (p<.001) higher than the 0.5% group (34.70±3.93) and the 1% group (35.43±2.33).

There was a statistically significant difference in elastic modulus among the groups [F(2, 68) = 241.97, p < .001]. Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test showed that the mean elastic modulus for the 0% samples (1801.78±213.41) was statistically significantly (p<.001) higher than the 0.5% samples (822.35±151.50) and the 1% samples (930.29±130.37), as shown in

Figure 2.

A one-way between-subjects ANOVA was conducted to determine whether surface microhardness (SMH) significantly differed among the 0%, 0.5%, and 1% groups. The result showed a statistically significant difference in SMH among the groups [F(2, 60) = 4.57, p = 0.014]. Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test revealed that the mean SMH for the 0% group (31.29±13.31) was significantly higher than the SMH for the 1% group (20.85±9.49) at the α level of .05 as shown in

Figure 3, but there was no significant difference for the 0% and 0.5% (28.52±11.65) samples. The association between SMH and modulus or flexural stress was not significant in all groups (0%, 0.5%, 1%).

When samples were examined with SEM, as seen in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, there were structural differences observed in each group. The 0.5% appeared smoother when compared to the other two groups. 1% samples appeared layered with different sizes of islands. When reviewing the cross-sectional surface, the group that had more voids, porosities, and irregularities was the 1% samples. 0.5% had fewer irregularities, were smoother, and appeared to have fewer voids and porosities.

4. Discussion

A denture base with an antimicrobial effect would be an outstanding achievement, but its physical and mechanical properties should not be negatively affected [

6]. The results from previous studies have shown that it is possible to incorporate organoselenium into PMMA denture base material and limit/inhibit the growth of Candida [

19,

29]. If we could help a patient by incorporating organoselenium into their denture and, in turn, decrease the possibility of them experiencing denture stomatitis without adding to their responsibilities or taking away from the success of their denture, it would be ideal. Organoselenium incorporated into materials does not leach out, increasing its safety, and has led to an increase in the application of selenium and selenium-containing compounds in the fields of dentistry, orthopedics, and ophthalmology [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

29]. For these reasons, the present study investigated the mechanical and physical properties of PMMA denture base after the incorporation of organoselenium. ANSI/ADA Specification No. 12 describes the requirements and specifications for denture base polymers. Since the oral cavity can be a harsh environment for materials that need to withstand changing temperatures, acidities, and textures of food, there needs to be a standard. The material also must be biocompatible and non-toxic.

In the present study, the effect of organoselenium on the mechanical properties of the PMMA, including the flexural stress and elastic modulus, was statistically significant when compared with samples without organoselenium, negatively impacting how we can use it in PMMA. The addition of organoselenium lowered the flexural stress and elastic modulus in comparison with samples without organoselenium. Therefore, the null hypothesis of the present study was accepted. Flexural stress is when an outside source applies a force and causes a material to bend or deform, whereas elastic modulus is a material’s resistance to being deformed [

6]. Both properties that denture bases need to function well in the oral cavity, withstanding the chewing forces, parafunctional habits, and abrasive forces. The Group without organoselenium (0% concentration) displayed superior flexural stress and elastic modulus resistance under force application, suggesting that the PMMA demonstrated enhanced properties in the absence of organoselenium.

Organoselenium interacts with the denture base resin through covalent bonding [

20], whereas the setting reaction of the PMMA denture base material utilized in this study primarily follows a free radical polymerization mechanism. Previous investigations into the incorporation of nanoparticles into denture base materials have indicated that the mechanical properties of PMMA denture material are significantly affected by their interactions with the polymeric matrix. The covalent bonding and free radical polymerization interaction may be a contributing factor to the differences observed in flexural strength and elastic modulus when organoselenium is introduced. Additionally, critical factors such as particle concentration, morphology, and size significantly influence these mechanical properties [

30]. In the study conducted by Balos et al, enhanced particle distribution within PMMA denture material was correlated with an increase in elastic modulus [

31]. In contrast, the insufficient particle dispersion in the present study may have contributed to the observed decrease in elastic modulus.

A study by Castro et al. revealed that flexural strength in PMMA resins containing silver nanoparticles was diminished due to poor dispersion during manual incorporation of the material [

32]. Moreover, it has been documented in previous studies that the addition of specific monomers to denture base materials can compromise flexural strength, primarily due to the formation of clusters that function as impurities, thereby creating zones of stress concentration. This issue is again associated with manual mixing techniques [

33,

34]. The present study utilized manual incorporation methods, which may have contributed to the reduction in flexural strength noted with increasing concentrations of organoselenium. As a result, exploring alternative mixing techniques may prove advantageous for enhancing the integration of organoselenium into the polymer matrix.

The SMH was significantly higher in samples without organoselenium compared to those containing 1% organoselenium. However, no significant difference was observed between the 0% and 0.5% samples. In a separate investigation by AlZayyat et al., it was reported that higher concentrations of SiO2 incorporated into denture base resins resulted in increased voids and porosity, which subsequently reduced the flexural strength of the PMMA denture material [

30]. Cross-sectional analysis in the present study revealed that the group with the highest concentration of organoselenium exhibited a greater number of voids, porosities, and surface irregularities, while the group devoid of organoselenium displayed the least. Consequently, the increases in voids and porosity associated with organoselenium incorporation likely contributed to the observed decrease in flexural strength and SMH.

In terms of physical properties, the group with 0.5% organoselenium demonstrated a smoother surface, potentially creating a less conducive environment for the proliferation of Candida albicans. Although the 0% group appeared less porous than the 0.5% samples, its surface texture was comparatively less smooth.

Some of the limitations in the design of the present study were a) maintaining a uniform sample size that can better account for the volumetric and linear shrinkage of PMMA, and b) the viscosity of organoselenium, making it difficult to pipette. As organoselenium is becoming increasingly used in dentistry, more studies are needed on incorporating it into denture material if it is to be used as an antimicrobial and still maintain physical and mechanical properties.

5. Conclusions

Within the limits of the present study, incorporation of organoselenium into PMMA denture base negatively affected its physical and mechanical properties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.T.A.; methodology, A.D. and S.A.; formal analysis, A.C.O.; investigation, M.G. and S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, T.G. and V.V.; writing—review and editing, M.V. and T.O.O.; supervision, B.T.A. and S.J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author (B.T.A.).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank SelenBio, Inc., Austin, Texas, USA for their support in providing the Organoselenium used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- National Institutes of Health. World’s older population grows dramatically (2016). Available form: https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/worlds-older-population-grows-dramatically/ Accessed: 2/10/2025.

- Perić, M.; Miličić, B.; Pfićer, J.K.; Živković, R.; Arsenijević, V.A. A Systematic Review of Denture Stomatitis: Predisposing Factors, Clinical Features, Etiology, and Global Candida spp. Distribution. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, F.L.; Wilson, D.; Hube, B. Candida albicanspathogenicity mechanisms. Virulence 2013, 4, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, J.S.; Mitchell, A.P. Genetic control of Candida albicans biofilm development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 9, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarborough, A.; Cooper, L.; Duqum, I.; Mendonca, G.; McGraw, K.; Stoner, L. Evidence Regarding the Treatment of Denture Stomatitis. J. Prosthodont. 2016, 25, 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, M.M.; Al-Thobity, A.M.; Fouda, S.M.; Näpänkangas, R.; Raustia, A. Flexural and Surface Properties of PMMA Denture Base Material Modified with Thymoquinone as an Antifungal Agent. J. Prosthodont. 2020, 29, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda, S.M.; Gad, M.M.; Ellakany, P.; Al-Thobity, A.M.; Al-Harbi, F.A.; Virtanen, J.I.; Raustia, A. The effect of nanodiamonds on candida albicans adhesion and surface characteristics of PMMA denture base material - an in vitro study. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2019, 27, e20180779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, G.; Berzins, D.W.; Dhuru, V.B.; Periathamby, A.R.; Dentino, A. Physical Properties of Denture Base Resins Potentially Resistant to Candida Adhesion. J. Prosthodont. 2007, 16, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanie, T.; Arikawa, H.; Fujii, K.; Inoue, K. Physical and mechanical properties of PMMA resins containing γ-methacryloxypropyltrimethoxysilane. J. Oral Rehabilitation 2004, 31, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, T.R.; Regis, R.R.; Bonatti, M.R.; de Souza, R.F. Influence of incorporation of fluoroalkyl methacrylates on roughness and flexural strength of a denture base acrylic resin. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2009, 17, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirizadeh, A.; Atai, M.; Ebrahimi, S. Fabrication of denture base materials with antimicrobial properties. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2018, 119, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Gong, H.; Zhang, J.; Guo, X.; Yan, M.; Zhu, S. Effects of antibacterial coating on monomer exudation and the mechanical properties of denture base resins. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2017, 117, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Harbi, F.A.; Abdel-Halim, M.S.; Gad, M.M.; Fouda, S.M.; Baba, N.Z.; AlRumaih, H.S.; Akhtar, S. Effect of Nanodiamond Addition on Flexural Strength, Impact Strength, and Surface Roughness of PMMA Denture Base. J. Prosthodont. 2018, 28, E417–E425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Sun, J.; Lan, J.; Qi, Q. Effect of a denture base acrylic resin containing silver nanoparticles onCandida albicansadhesion and biofilm formation. Gerodontology 2014, 33, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagnoni, M.A.; Pero, A.C.; Ramos, S.M.M.; Marra, J.; Paleari, A.G.; Rodriguez, L.S. Antimicrobial activity and surface properties of an acrylic resin containing a biocide polymer. Gerodontology 2012, 31, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, G.; Huang, S.; Knoernschild, K.; Sukotjo, C.; Campbell, S.; Bishal, A.K.; Barão, V.A.; Wu, C.D.; Taukodis, C.G.; Yang, B. Improving Polymethyl Methacrylate Resin Using a Novel Titanium Dioxide Coating. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, D.; Sweet, S.; Challacombe, S.; Walter, J. Adherence of Candida albicans to denture-base materials with different surface finishes. J. Dent. 1998, 26, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revised American Dental Association Specification, No. 12 for denture base polymers. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1975, 90, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMojel, N.; AbdulAzees, P.A.; Lamb, E.M.; Amaechi, B.T. Determining growth inhibition of Candida albicans biofilm on denture materials after application of an organoselenium-containing dental sealant. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2023, 129, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.; Enos, T.; Luth, K.; Hamood, A.; Ray, C.; Mitchell, K.; Reid, T.W. Organo-Selenium-Containing Polyester Bandage Inhibits Bacterial Biofilm Growth on the Bandage and in the Wound. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.; Hamood, A.; Mosley, T.; Gray, T.; Jarvis, C.; Webster, D.; Amaechi, B.; Enos, T.; Reid, T. Organo-Selenium-containing Dental Sealant Inhibits Bacterial Biofilm. J. Dent. Res. 2013, 92, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.; Arnett, A.; Jarvis, C.; Mosley, T.; Tran, K.; Hanes, R.; Webster, D.; Mitchell, K.; Dominguez, L.; Hamood, A.; et al. Organo-Selenium Coatings Inhibit Gram-Negative and Gram-Positive Bacterial Attachment to Ophthalmic Scleral Buckle Material. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2017, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, P.L.; Hammond, A.A.; Mosley, T.; Cortez, J.; Gray, T.; Colmer-Hamood, J.A.; Shashtri, M.; Spallholz, J.E.; Hamood, A.N.; Reid, T.W. Organoselenium Coating on Cellulose Inhibits the Formation of Biofilms byPseudomonas aeruginosaandStaphylococcus aureus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 3586–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gendreau, L.; Loewy, Z.G. Epidemiology and Etiology of Denture Stomatitis. J. Prosthodont. 2011, 20, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susewind, S.; Lang, R.; Hahnel, S. Biofilm formation and Candida albicans morphology on the surface of denture base materials. Mycoses 2015, 58, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqutaibi, A.Y.; Baik, A.; Almuzaini, S.A.; Farghal, A.E.; Alnazzawi, A.A.; Borzangy, S.; Aboalrejal, A.N.; AbdElaziz, M.H.; Mahmoud, I.I.; Zafar, M.S. Polymeric Denture Base Materials: A Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhajar, E.; Ali, K.; Zulfiqar, G.; Al Ansari, K.; Raja, H.Z.; Bishti, S.; Anweigi, L. Management of Chronic Atrophic Candidiasis (Denture Stomatitis)—A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2023, 20, 3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, A.A.E.-L.; Elrahim, R.A.A.; El Hakim, A.F.A.; Harby, N.M.; Helal, M.A. Evaluation of Surface Properties and Elastic Modulus of CAD-CAM Milled, 3D Printed, and Compression Moulded Denture Base Resins. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2022, 12, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawadi, A.; AbdulAzees, P.A.; Lin, C.; Haney, S.J.; Hanlon, J.P.; Angelara, K.; Taft, R.M.; Amaechi, B.T. Application of organoselenium in inhibiting Candida albicans biofilm adhesion on 3D printed denture base material. J. Prosthodont. 2023, 33, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzayyat, S.T.; Almutiri, G.A.; Aljandan, J.K.; Algarzai, R.M.; Khan, S.Q.; Akhtar, S.; Ateeq, I.S.; Gad, M.M. Effects of SiO2 Incorporation on the Flexural Properties of a Denture Base Resin: An In Vitro Study. Eur. J. Dent. 2021, 16, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balos, S.; Puskar, T.; Potran, M.; Milekic, B.; Koprivica, D.D.; Terzija, J.L.; Gusic, I. Modulus, Strength and Cytotoxicity of PMMA-Silica Nanocomposites. Coatings 2020, 10, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, D.T.; Valente, M.L.; da Silva, C.H.; Watanabe, E.; Siqueira, R.L.; Schiavon, M.A.; Alves, O.L.; dos Reis, A.C. Evaluation of antibiofilm and mechanical properties of new nanocomposites based on acrylic resins and silver vanadate nanoparticles. Arch. Oral Biol. 2016, 67, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regis, R.R.; Zanini, A.P.; Della Vecchia, M.P.; Silva-Lovato, C.H.; Paranhos, H.F.O.; de Souza, R.F. Physical Properties of an Acrylic Resin after Incorporation of an Antimicrobial Monomer. J. Prosthodont. 2011, 20, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, L.S. , Paleari A.G., Giro G., Junior N.M.D.O., Pero A.C., Compagnoni M.A. Chemical Characterization and Flexural Strength of a Denture Base Acrylic Resin with Monomer 2-Tert-Butylaminoethyl Methacrylate. J. Prosthodont. 2012;22:292–297.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).