1. Introduction

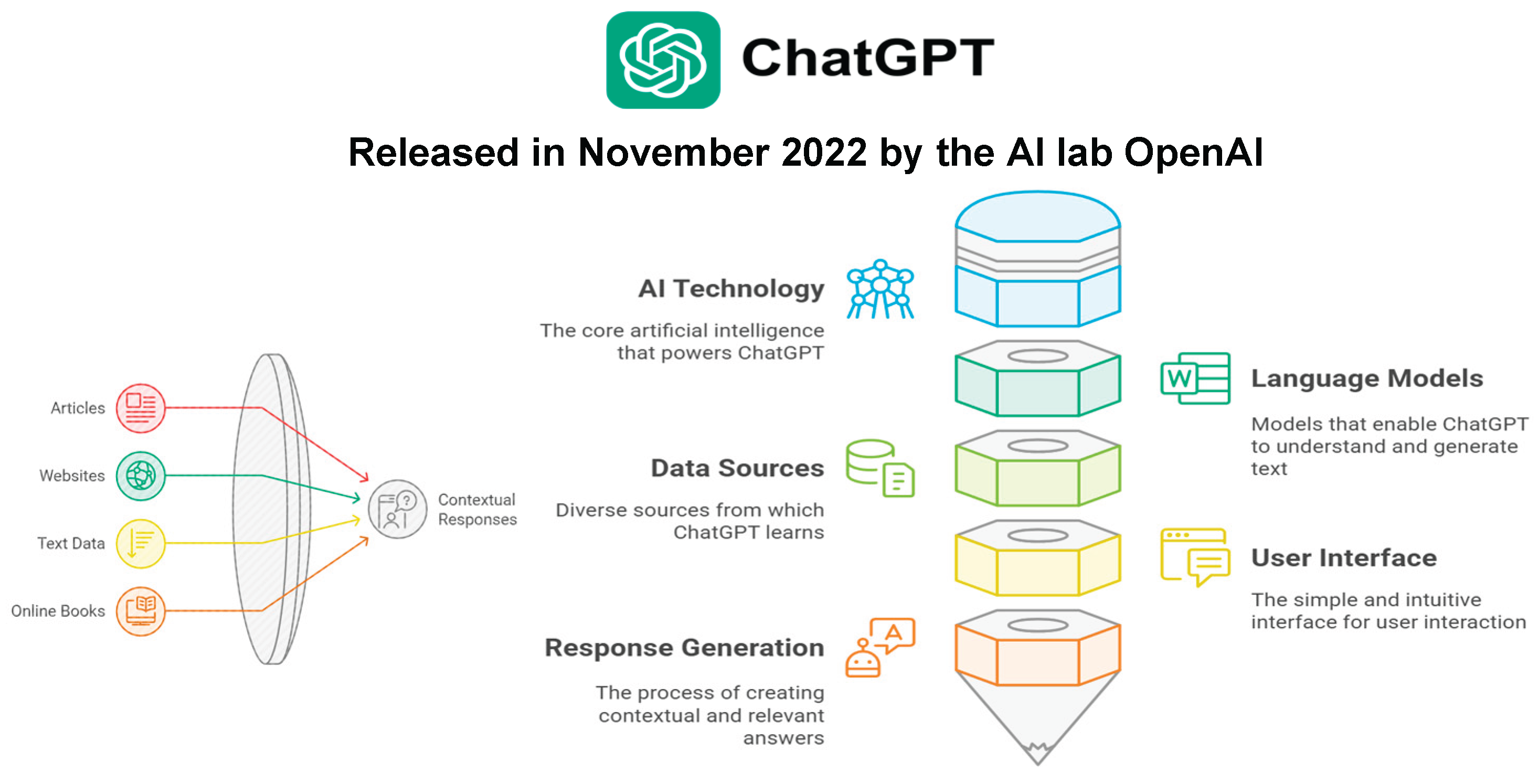

ChatGPT (Chat.openai.com - Chat Generative Pre-Trained Transformer) is an artificial intelligence (AI) tool released in November 2022 by the AI lab OpenAI (OpenAI Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA). It is a large language model trained on several text datasets from various sources, including articles, websites, text data, online books, and more, to recognize patterns, interpret, and generate human-like textual responses to a wide range of questions using a simple interface. The interface utilizes large language models that can access recall vast amounts of information encoded in their parameters, interact with the user, and learn from each conversation [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13],

Figure 1.

ChatGPT can be applied in different fields such as education, medicine, and research [

13]. However, users may be aware about the accuracy of its responses, as the information provided could vary in reliability [

6]. This is influenced by the data used to train ChatGPT, as well as the user’s own education and background [

13]. This article aims to identify the applications, limitations, and future directions for ChatGPT in medical genetics.

2. Methods

This scoping review was conducted following the SALSA framework to develop a narrative qualitative analysis. We systematically searched the PubMed database and Google Scholar for relevant publications between December 1, 2022, and October 31, 2024. The keywords used in our search included a combination of “ChatGPT and medical genetics,” “ChatGPT and clinical genetics,” “ChatGPT and genetic counseling,” “ChatGPT and molecular laboratory,” and “ChatGPT and ethical issues.”

We included articles on the application of ChatGPT in medical genetics that were written in English from December 1, 2022, to October 31, 2024. We excluded non-open access articles, as well as comments, opinions, and letters to the editor. We screened titles and abstracts to eliminate irrelevant studies in the first round. We then reviewed the full texts of selected articles. From these, we extracted data and made a matrix review of relevant articles that included benefits, and limitations associated with ChatGPT,

Table 1.

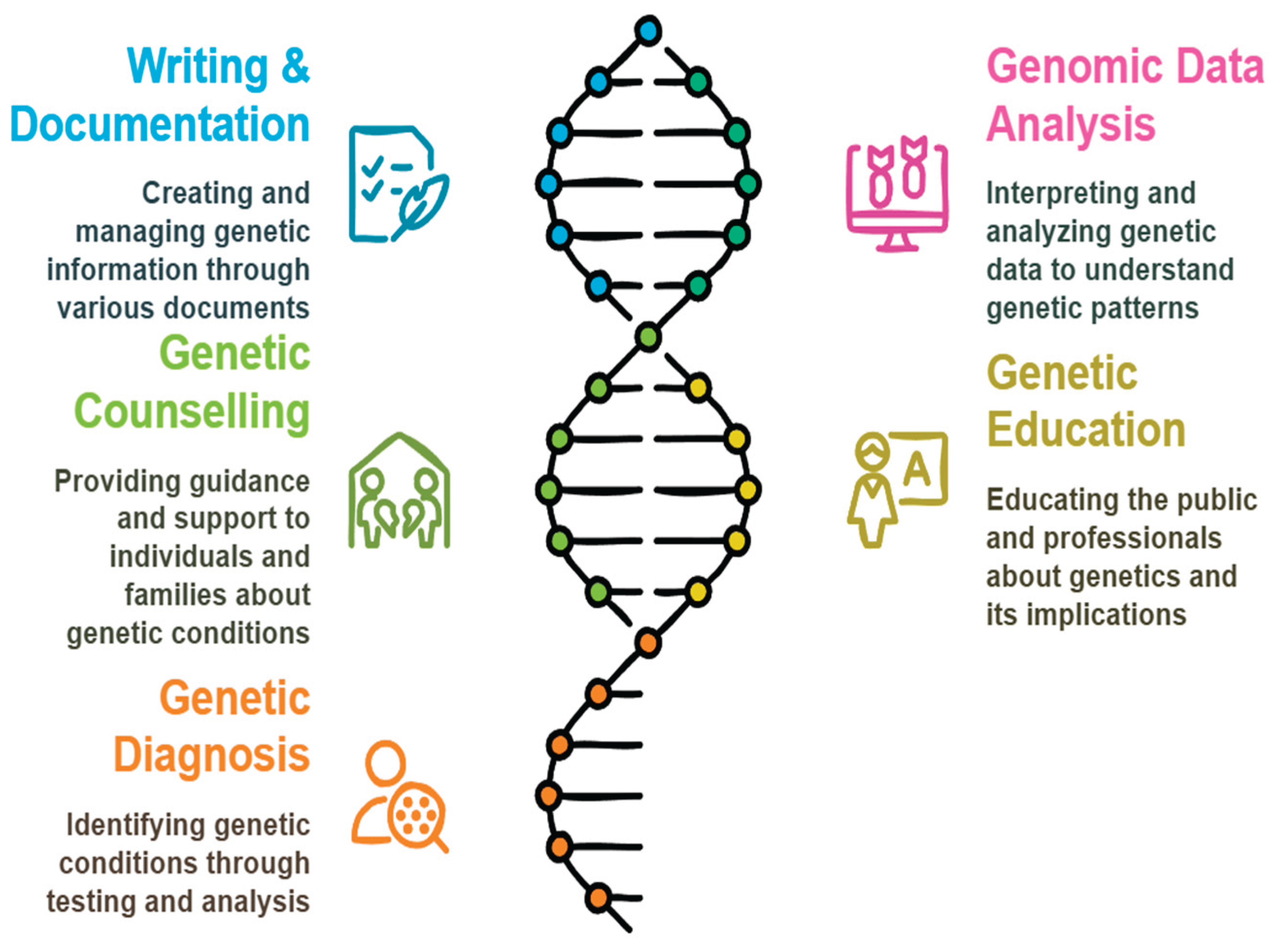

We categorized the ChatGPT applications into five categories: 1. Writing case reports, articles, experiments, and medical or educational documents; 2. Analyzing genomic data; 3. Providing genetic counselling; 4. Offering genetic education; and 5. Assisting in genetic diagnose,

Figure 2. Finally, we analyzed the benefits, limitations, and ethical issues of using ChatGPT in the field of medical genetics,

Figure 3.

3. Applications of ChatGPT in Medical Genetics

The applications of ChatGPT in medical genetics are synthetized in the

Table 1 and

Figure 2.

3.1. Application in the Literature Review and Writing Case Reports, Research Articles, and Medical or Educational Documents

ChatGPT can assist clinicians in accessing up-to-date clinical insights, treatments, and recommendations for common diseases. It can also aid in writing case reports, research articles, and different medical or educational documents.

ChatGPT can identify, summarize, and analyze studies based on directed questions or prompts. It can also provide information about clinical characteristics, epidemiology, disease markers, genes, and other aspects related to genetic diseases [

2,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

Furthermore, ChatGPT has the capability to generates text for different types of documents and questionaries in a clear and understandable format. This mekes written content more accessible, enhances clarity, synthesizes evidence, provides references, and supports the organizatin and presentation of complex genetic data [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

3.2. Application in Patient and Genomic Data Analysis

Advanced and paid versions of ChatGPT can integrate and analyze a broader and more complex range of human genetic and health-related phenotype data in medical genetics that help interpret the gene, phenotype, disease information, and significance of genetic variants [

6,

11]. For example, Cureus Journal published case reports in which ChatGPT wrote the genetic information related to de syndrome [

2,

8,

9]. Additionally, it generates patient-friendly genetic counseling documents and summaries of genetic results, implications, and recommended actions for common genetic conditions [

11,

12]. However, ChatGPT struggles with rare diseases where little or no data and information are available [

4,

6,

13].

3.3. Application in Genetic Counselling

Genetic counseling is a communication process that informs, educates, and supports individuals and their families with a genetic disorder. Its objective is to help them understand and adapt to the physical, mental, familial, and social implications of the patients’ genetic condition and empower them to decision-making. Its benefits are improving risk perception and knowledge and decreasing decisional conflict and emotional distress [

12]. Genetic counseling involves interpreting genetic test results, assessing familial and personal risk, and communicating complex genetic information to patients [

12]. The integration of AI tools like ChatGPT can significantly augment these processes by enhancing communication, education, and interpretation. ChatGPT can generate personalized, understandable explanations of genetic conditions, inheritance patterns, and testing options, aiding clinicians in conveying complex information effectively. It can also prepare frequently asked questions, clarify misconceptions, and provide emotional support through empathetic language [

11].

4. Benefits

Medical genetics and genetic counseling professionals can improve efficiency and save time finding sources, writing drafts or various documents, and checking grammar using ChtGPT [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. It is knowledgeable about common topics in multiple areas, diseases, recommendations, treatments, and other prompts [

1,

11,

13]. Additionally, ChatGPT can help generate text more quickly and assist in reading and discussing recent papers [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. It is particularly beneficial in medical genetics, where staying current is crucial for raising community awareness about ongoing research and treatments. Moreover, ChatGPT enables researchers to analyze larger datasets, which can help reduce false positive detections in their findings [

11]. It can also provide historical data on related genes or genomic positions, facilitating the assessment of similar methods or past results and assisting with data management and document preparation. Its capabilities highlight the significant potential of chatbots in academic research in medical genetics [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

13].

4.1. Efficiency and Time-Saving

The speed at which ChatGPT generates text in response to a prompt provides a significant advantage for medical genetics, molecular laboratory, genetic counseling, and the diagnostic process. Identifying which variants are clinically relevant and contribute to specific phenotypes during exome, genome, or gene panel sequencing analysis is crucial for medical genetics but can be time-consuming. ChatGPT has the potential to lighten the workload of clinical geneticists and could also serve as a second opinion when verifying suggested causative variants before applying the newly discovered genetic knowledge in a clinical setting [

5,

7,

9,

11].

The precision of deep learning applications in interpreting the clinical relevance of variants of uncertain significance offers additional time advantages by facilitating updates and reducing the large volume of such results. The automated, real-time generation of text could lead to substantial time savings in genome projects, increasing the proportion of patients receiving diagnosis within the genetic result’s timeline [

4].

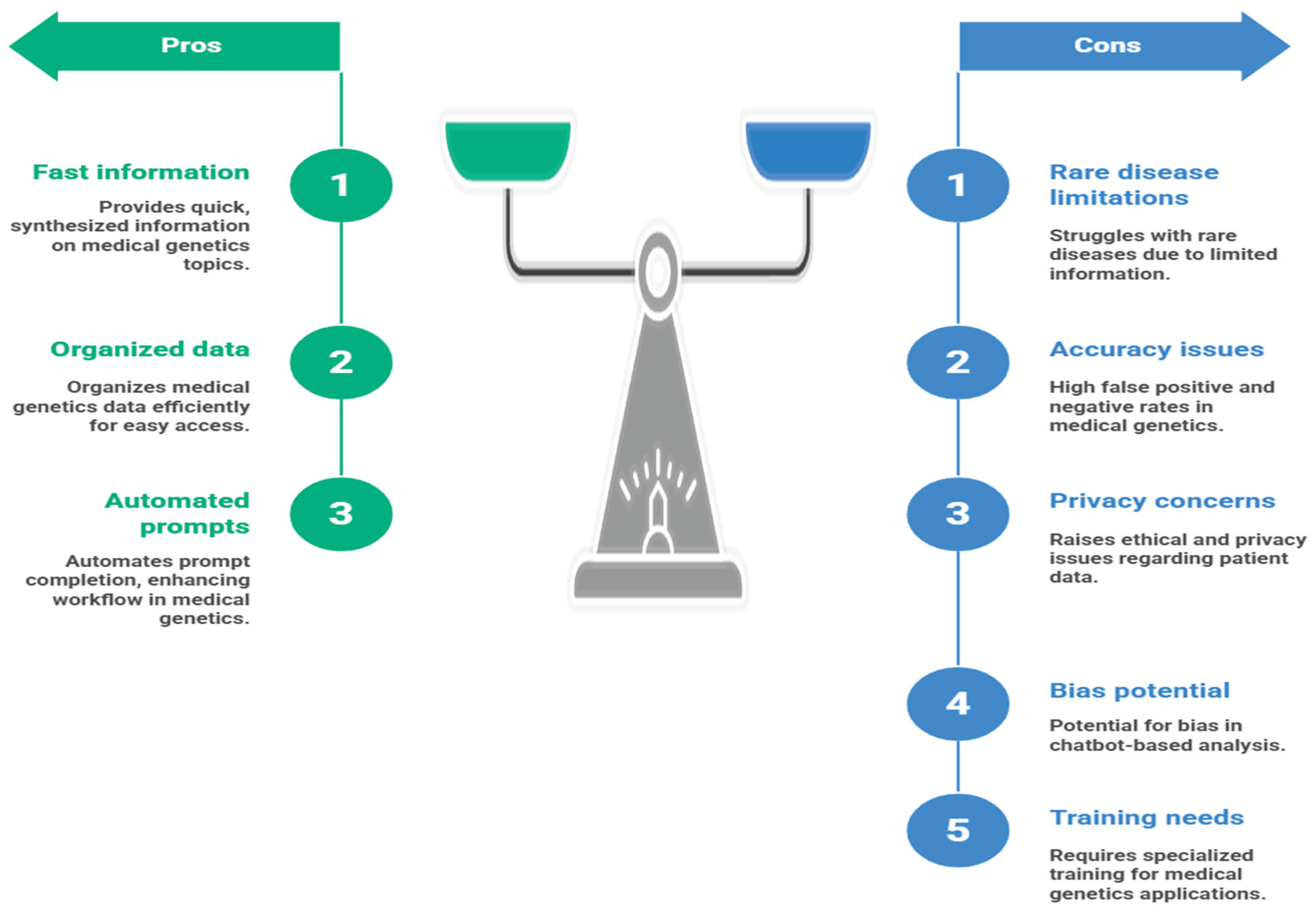

5. Limitations

We conducted a scoping review of the literature on the application of ChatGPT in the field of medical genetics, which is an emerging and evolving area. The primary focus of ChatGPT’s use is to automate prompt completion and provide fast, synthesized, and organized information related to medical genetics. However, there are limitations when it comes to rare diseases, as they are infrequent and have limited available information [

4,

6,

13]. There is a need for clearer guidelines, as the recognition of a disease’s phenotype for diagnosis is not very precise [

4,

5,

6,

13]. This reality indicates that ChatGPT requires further training and development to specialize in medical genetics [

4,

6].

Currently, the clinical impacts and potential biases arising from chatbot-based analysis assistance are underexplored. As the model’s accuracy and the complexity of its outcomes improve, it will be essential to critically evaluate the implications and benefits of using chatbot-generated information, along with resources for updating the model [

13].

It requires more indications and the recognition of the phenotype for the diagnosis of the disease is not as precise and requires better training and development of ChatGPT to specialize it in the field of medical genetics [

4,

5,

6]. To date, the clinical and possible bias-producing impacts of chatbot-based analysis assistance are underinvestigated, although as the model’s accuracy and complexity of the outcomes increase, the potential implications and utility of chatbot-based model information will need to be critically appraised, alongside resources for model adaptation updates.

5.1. Accuracy and Reliability

Studies demonstrated that ChatGPT had poor performance and reliability in rare genetic diseases and conditions with a heterogeneous clinical spectrum or atypical presentation [

4,

6,

13,

14,

15]. Users should be aware of these limitations, as errors could potentially harm patients in clinical and therapeutic environments and lead to legal issues for which ChatGPT cannot be held responsible.

Finally, the applications of ChatGPT in genetics, from both medical and research perspectives, present advantages and disadvantages, as illustrated in

Figure 3. These aspects require further examination and establishing legislation for patient and data protection.

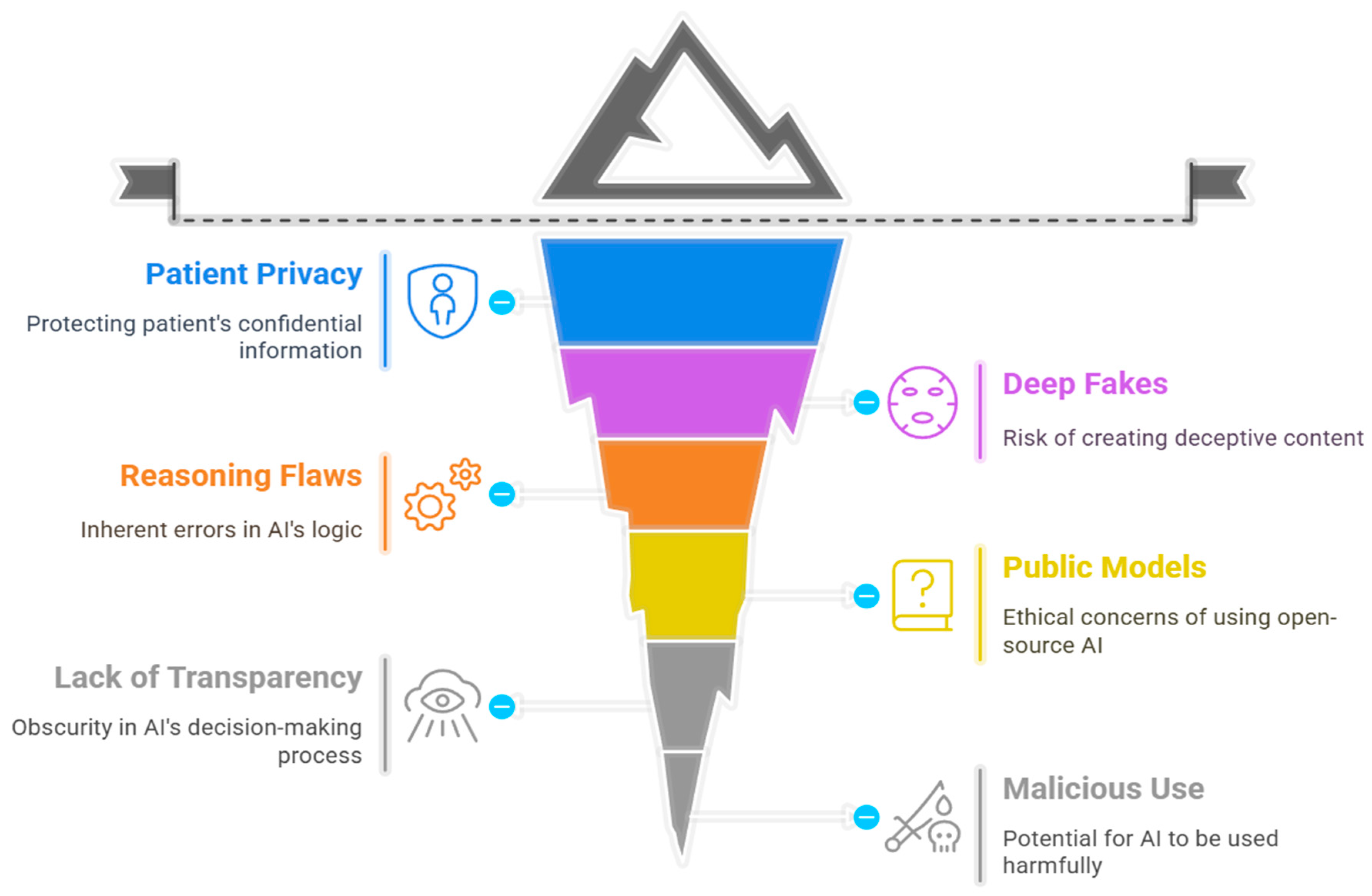

6. Ethical Issues

ChatGPT presents specific moral and social implications in the field of medical genetics. It raises several ethical issues, such as patient privacy, the risk of deepfakes, flawed reasoning, and challenges associated with public models. Therefore, regulations and safeguards must evolve to address these concerns as technology advances. It is crucial to emphasize the importance of mitigating the risks associated with these models, as their output can be indistinguishable from those created by humans [

13],

Figure 4.

In medical genetics, data security is a significant concern. LLM could exacerbate this issue due to the potential for automatically generating highly sophisticated fake clinical narratives, which could be misused for malicious purposes [

10,

13]. Additionally, erroneous and fake information may arise from training based on unreliable data [

10,

13]. Therefore, the creators and managers of ChatGPT should closely supervise its training and input processes. Furthermore, regulatory institutions must establish appropriate legislation, protections, and controls to address these challenges effectively.

6.1. Informed Consent and Data Privacy

As chatbots are increasingly used for health-related purposes and even for educational applications, it is important to protect the identities of their participants. A medical ChatGPT version has been trained with health data to provide better model performance. However, this training method may magnify privacy risks and increase the probability of data de-anonymization. Also, with the rise of multimodal language models, chatbot developers risk unintentionally violating individual privacy rights, so controlling and supervising the ChatGPT training is important.

Medical professionals have ethical guidelines and risk losing the trust of their patients if they do not respect them. As such, bots intended for health education, data collection, or assisting previously recorded patient queries should always keep the person’s anonymity [

15]. In addition to developer responsibility, ethical bot use extends to the implementation phase to ensure compliance with data protection regulations. The industry is responsible for developing research initiatives that make their privacy and confidentiality protocols more explicit and verify their efficacy accordingly. Also, patients should ask for their data privacy consent and have details about how information will be stored, protected, and shared, allowing them to provide informed, meaningful consent. Legal representatives should be capable of providing valid consent on behalf of those disenfranchised. Participants should be capable of withdrawing their consent at any time if given access to recordings or transcripts, allowing for removing any relevant parts if preferred.

7. Discussion

The applications of ChatGPT in medical genetics are writing case reports, articles, experiments, and medical or educational documents; analyzing genomic data; providing genetic counseling; offering genetic education; and assisting in genetic diagnosis. However, its accuracy responses depend on its previous training information, data availability, and user prompt [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

13,

14]. Studies demonstrated poor ChatGPT accuracy in diagnosing rare and atypical presentations of common conditions [

4,

6,

13,

14]. As well as, the accuracy of the response is worse in ultra-rare diseases and extremely atypical presentation of the common disease, which has poor or no information.

ChatGPT can be trained with rare disease data to improve the validity of its responses and diagnostic accuracy. It can also improve its performance by integrating ChatGPT with genetic databases or tools such as OMIM, Genereviews, Human Phenotype Ontology, and other sources.

Another important aspect to address regarding the use of chatGPT in medical genetics is the ethical issues, such as loss of privacy and malicious use of chatGPT [

6], which can cause harm. Therefore, better legislation and controls are needed.

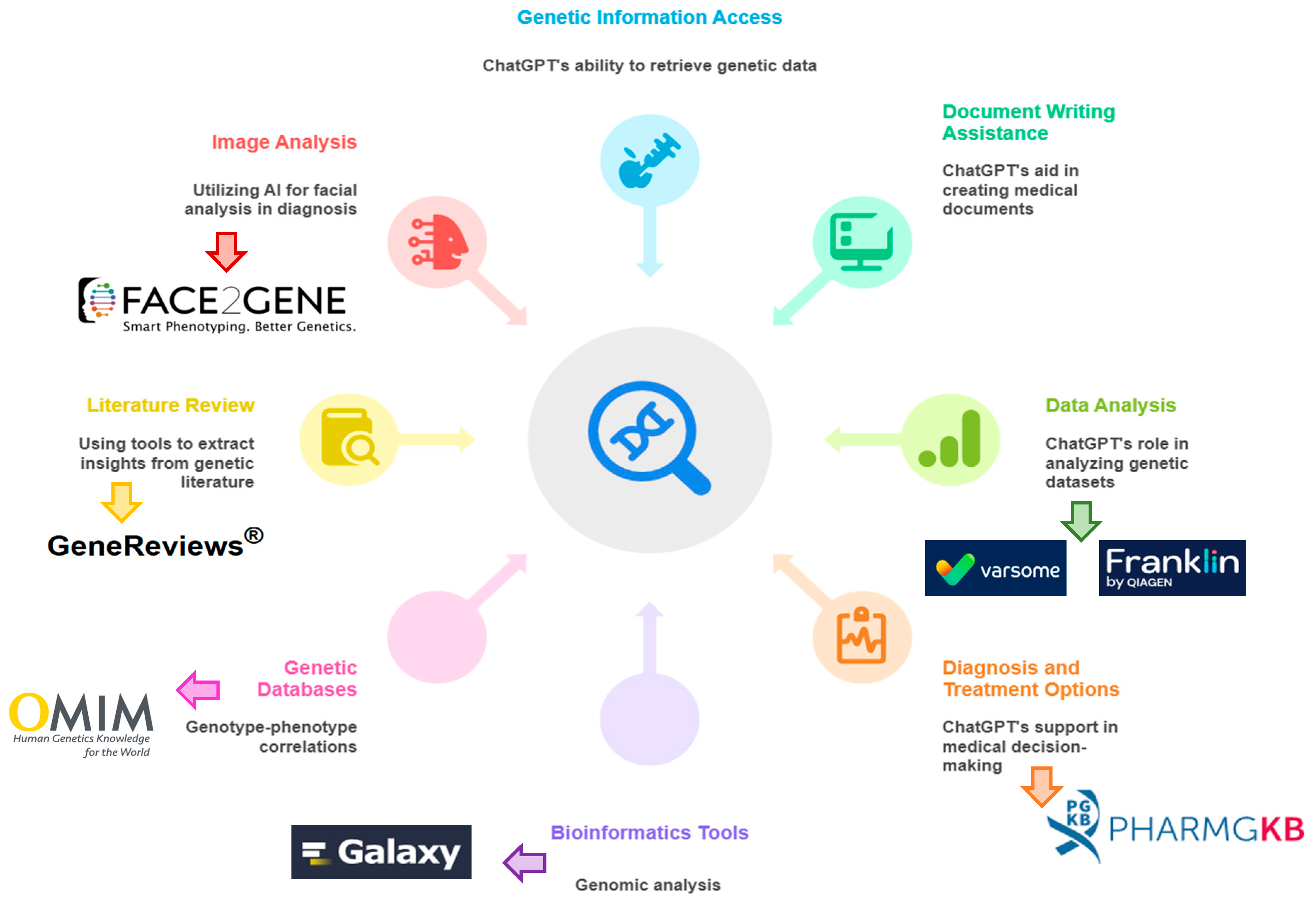

8. Conclusion and Future Directions

ChatGPT can be helpful in Medical Genetics by providing access to genetic information, assisting with document writing, performing data analysis, and aiding in diagnosis and treatment options. However, using ChatGPT cautiously and verifying its responses is essential, especially when dealing with rare diseases, as it may generate inaccurate information or hallucinate facts. Users must have foundational knowledge about the topics they are researching through ChatGPT since it is still in development and not specifically designed for genetic medical purposes [

13].

Furthermore, ChatGPT can be integrated with other tools to enhance its utility in this field. For instance, combining ChatGPT with bioinformatics tools could assist in analyzing genomic sequences, such as using variant callers and gene annotation software. Additionally, linking ChatGPT with specialized genetic databases, like OMIM and ClinVar, could provide valuable insights into genotype-phenotype correlations and generate more accurate, up-to-date diagnosis responses.

Figure 5.

Conclusion and Futere integration to other tools.

Figure 5.

Conclusion and Futere integration to other tools.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.P. and M.A.; methodology, H.P. and M.A.; validation, M.A. and H.P.; formal analysis, H.P. and M.A.; investigation, M.A.; resources, M.A.; data curation, M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.; writing—review and editing, M.A. and H.P.; visualization, M.A.; supervision, H.P.; project administration, H.P. Authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statements

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data Sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledge

Grammarly assisted with grammar corrections, ChatGPT helped summarize the literature review and writing in English, and Napkin AI helped develop the figures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aradhya, Swaroop, Flavia M. Facio, Hillery Metz, Toby Manders, Alexandre Colavin, Yuya Kobayashi, Keith Nykamp, Britt Johnson, and Robert L. Nussbaum. “Applications of artificial intelligence in clinical laboratory genomics.” In American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, vol. 193, no. 3, p. e32057. Hoboken, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2023.

- Afzal, Iraj, Samin Rahman, Faiz Syed, Ofek Hai, Roman Zeltser, and Amgad N. Makaryus. “Transient ischemic attack in a patient with Poland syndrome with dextrocardia.” Cureus 15, no. 4 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Guo, Kairui, Mengjia Wu, Zelia Soo, Yue Yang, Yi Zhang, Qian Zhang, Hua Lin et al. “Artificial intelligence-driven biomedical genomics.” Knowledge-Based Systems 279 (2023): 110937. [CrossRef]

- Mehnen, Lars, Stefanie Gruarin, Mina Vasileva, and Bernhard Knapp. “ChatGPT as a medical doctor? A diagnostic accuracy study on common and rare diseases.” MedRxiv (2023): 2023-04.

- Labbé, Thomas, Pierre Castel, Jean-Michel Sanner, and Majd Saleh. “ChatGPT for phenotypes extraction: one model to rule them all?.” In 2023 45th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), pp. 1-4. IEEE, 2023.

- Rane, Nitin. “Contribution and Challenges of ChatGPT and Similar Generative Artificial Intelligence in Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology.” Genetics and Molecular Biology (October 16, 2023) (2023).

- Stier, Quirin, and Michael C. Thrun. “Deriving Homogeneous Subsets from Gene Sets by Exploiting the Gene Ontology.” Informatica 34, no. 2 (2023): 357-386.

- Mansur, Maureen, Thomas J. Jacob, Helen Wong, and Ilya Tarascin. “Cat eye syndrome with a unique liver and dermatological presentation.” Cureus 15, no. 4 (2023).

- McCormick, Benjamin J., and Razvan M. Chirila. “ANKRD26 gene variant of uncertain significance in a patient with acute myeloid leukemia.” Cureus 15, no. 3 (2023): e36152. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Xiao, Yuang Qi, Kejiang Chen, Guoqiang Chen, Xi Yang, Pengyuan Zhu, Weiming Zhang, and Nenghai Yu. “Gpt paternity test: Gpt generated text detection with gpt genetic inheritance.” CoRR (2023).

- McGrath, Scott P., Beth A. Kozel, Sara Gracefo, Nykole Sutherland, Christopher J. Danford, and Nephi Walton. “A comparative evaluation of ChatGPT 3.5 and ChatGPT 4 in responses to selected genetics questions.” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 31, no. 10 (2024): 2271-2283.

- Veach, Patricia McCarthy, Dianne M. Bartels, and Bonnie S. LeRoy. “Coming full circle: a reciprocal-engagement model of genetic counseling practice.” Journal of genetic counseling 16 (2007): 713-728. [CrossRef]

- Zampatti, Stefania, Cristina Peconi, Domenica Megalizzi, Giulia Calvino, Giulia Trastulli, Raffaella Cascella, Claudia Strafella, Carlo Caltagirone, and Emiliano Giardina. “Innovations in Medicine: Exploring ChatGPT’s Impact on Rare Disorder Management.” Genes 15, no. 4 (2024): 421. [CrossRef]

- Shikino, Kiyoshi, Taro Shimizu, Yuki Otsuka, Masaki Tago, Hiromizu Takahashi, Takashi Watari, Yosuke Sasaki et al. “Evaluation of ChatGPT-Generated Differential diagnosis for Common diseases with atypical presentation: descriptive research.” JMIR Medical Education 10 (2024): e58758. [CrossRef]

- Baumer, David, Julia Brande Earp, and Fay Cobb Payton. “Privacy of medical records: IT implications of HIPAA.” ACM SIGCAS Computers and Society 30, no. 4 (2000): 40-47.

- Venkatapathappa, Priyanka, Ayesha Sultana, K. S. Vidhya, Romy Mansour, Venkateshappa Chikkanarayanappa, and Harish Rangareddy. “Ocular Pathology and Genetics: Transformative Role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Anterior Segment Diseases.” Cureus 16, no. 2 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Huang, Jingwei, Donghan M. Yang, Ruichen Rong, Kuroush Nezafati, Colin Treager, Zhikai Chi, Shidan Wang et al. “A critical assessment of using ChatGPT for extracting structured data from clinical notes.” npj Digital Medicine 7, no. 1 (2024): 106. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Jinge, Zien Cheng, Qiuming Yao, Li Liu, Dong Xu, and Gangqing Hu. “Bioinformatics and biomedical informatics with ChatGPT: Year one review.” Quantitative Biology 12, no. 4 (2024): 345-359. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).