Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

01 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

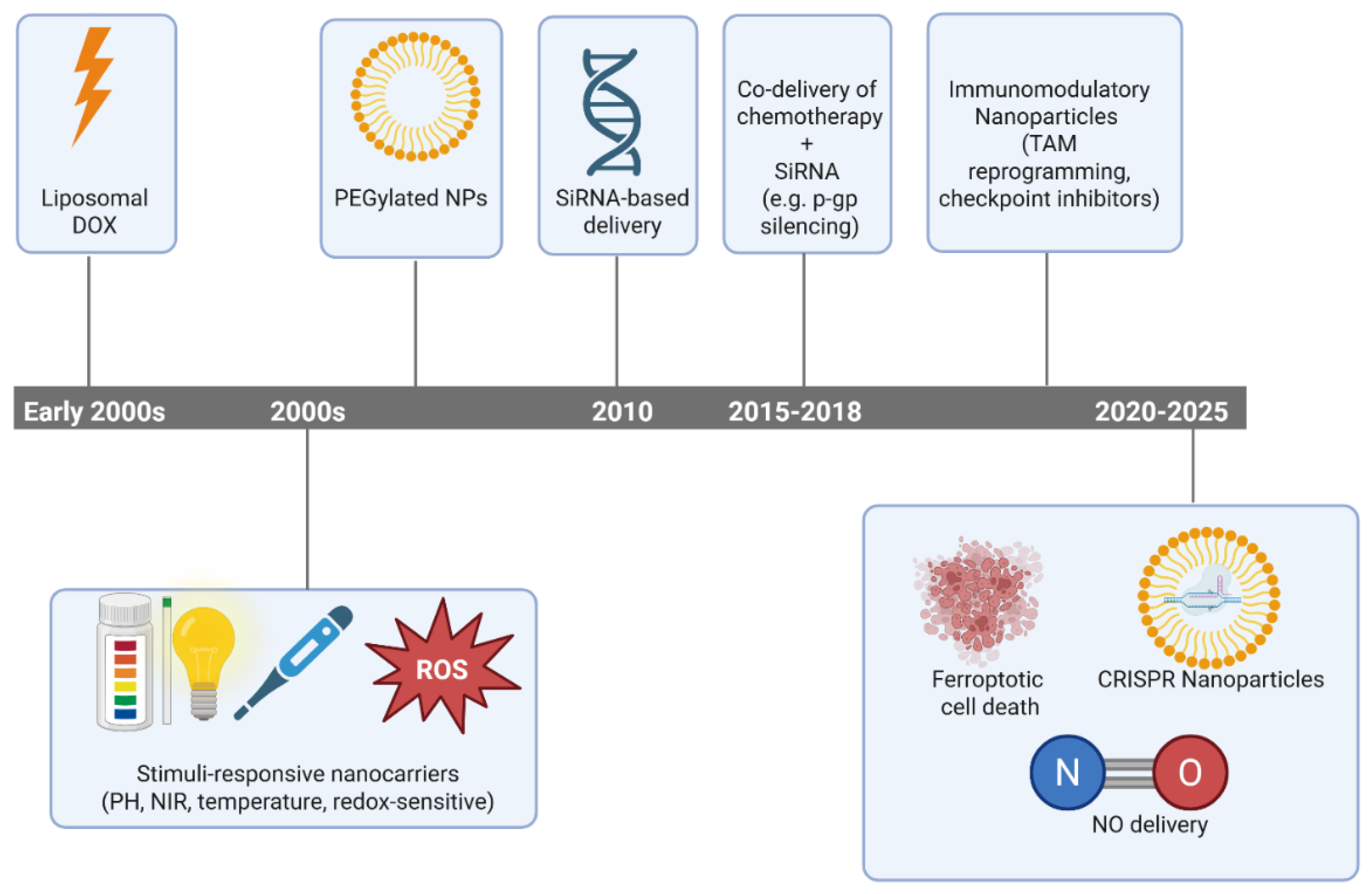

1. Introduction

2. Mechanisms of MDR in Cancer

2.1. Drug Efflux Transporters

2.2. Apoptosis Evasion

2.3. Enhanced DNA Repair

2.4. Tumor Microenvironment (TME)-Induced Resistance

2.5. Epigenetic Reprogramming

3. Strategies to Overcome Multidrug Resistance

3.1. Nanocarriers Inhibiting Drug Efflux Pumps (P-gp, MRP2, etc.)

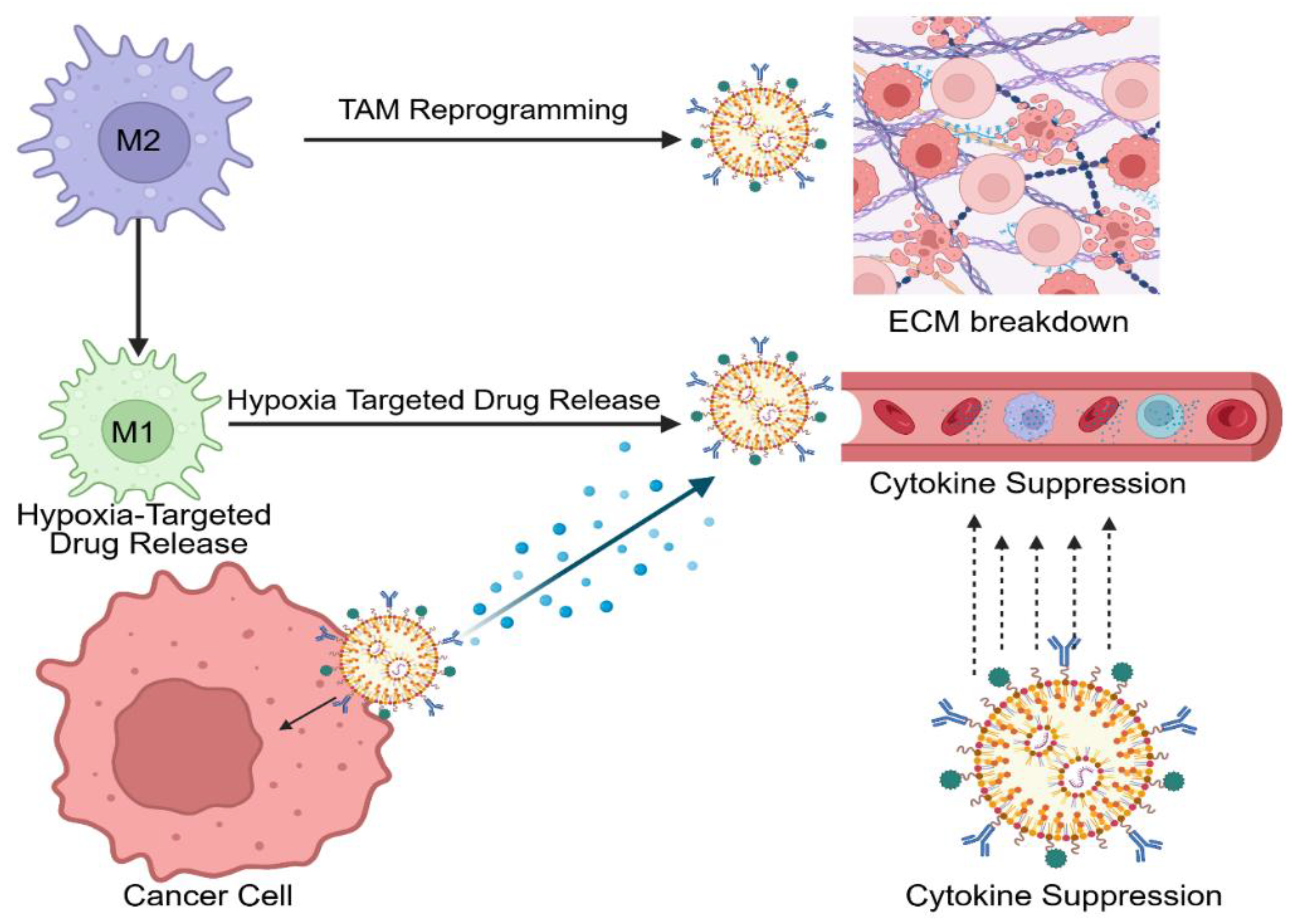

3.2. Modulating the Tumor Microenvironment (TME)

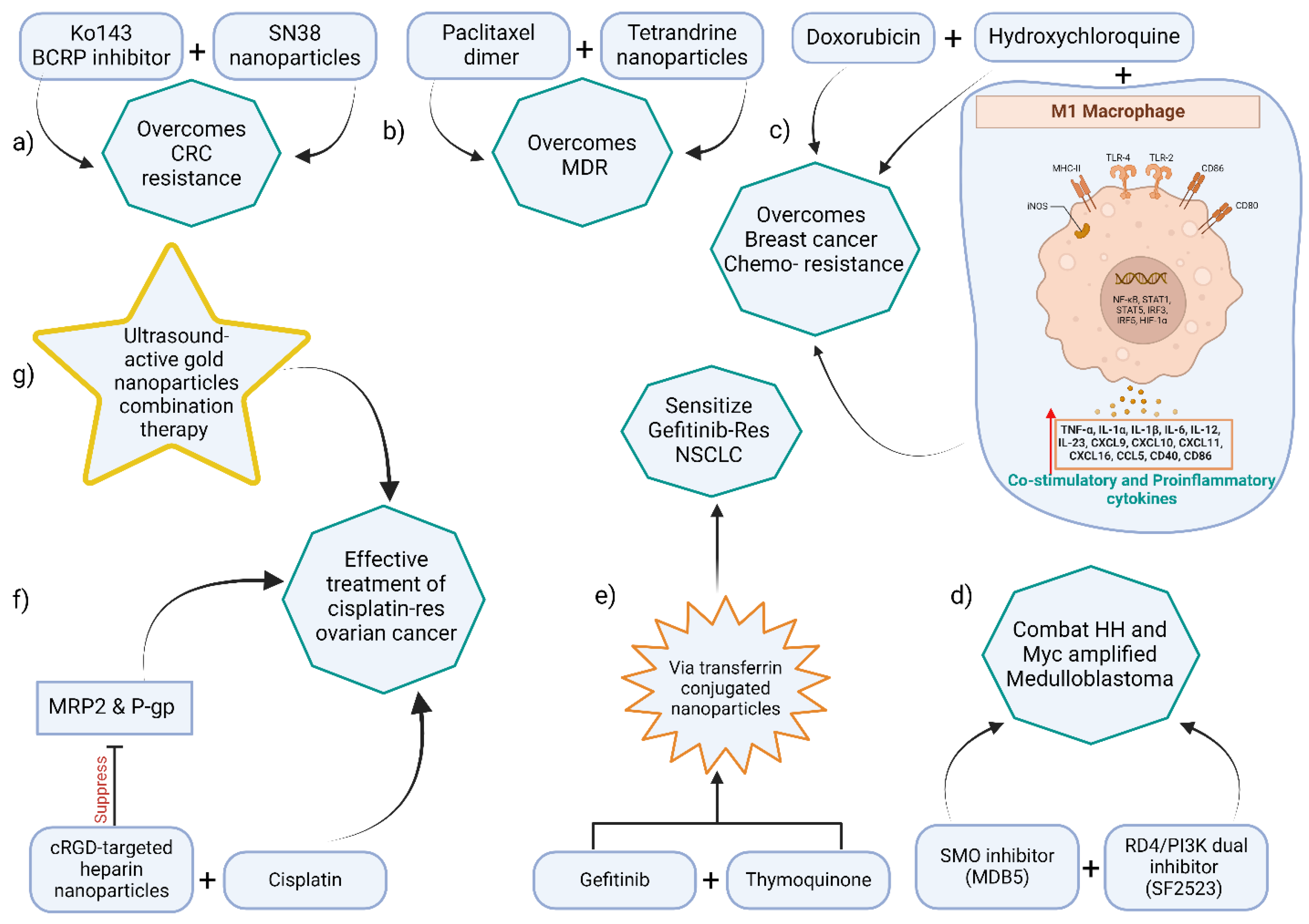

3.3. Dual and Multi-Drug Co-Delivery Nanosystems

3.3.1. Chemotherapy–chemosensitizer combination

3.3.2. Dual chemotherapies

3.3.3. Drug–gene combinations

| Nanoformulation | Drugs/Agents | Cancer Model | Key Outcomes (synergy) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymeric NP (mPEG-PLGA) | Paclitaxel dimer prodrug + Tetrandrine | MDR HeLa cells (cervical) | Enhanced uptake and ROS; ≈50% higher apoptosis vs. single drug |

| Polymeric NP (PEG-coated) | SN-38 (prodrug) + Ko143 (BCRP inhibitor) | BCRP-overexpressing CRC xenograft | Reversed irinotecan resistance; ~10-fold ↓ IC₅₀ |

| Transferrin-PLGA NP | Gefitinib (EGFR-TKI) + Thymoquinone | Gefitinib-resistant NSCLC (A549/GR) | Re-sensitized to gefitinib; suppressed EMT (increased E-cadherin) |

| cRGD–Heparin NP | Cisplatin + Olaparib (PARP inhibitor) | Cisplatin-resistant ovarian | Inhibited P-gp/MRP2, ↑ DNA damage; overcame cisplatin resistance |

| Doxorubicin liposome + HCQ* | Doxorubicin + Hydroxychloroquine | DOX-resistant breast cancer | Restored apoptosis; polarized TAMs to M1 (↑TNFα, IL-12) |

3.4. Tumor-Specific Targeting and Active Delivery Systems

3.5. Nanotechnology in Specific Cancers: Colorectal, Breast, Ovarian, and Kidney

3.5.1. Colorectal Cancer (CRC)

3.5.2. Breast Cancer

3.5.3. Ovarian Cancer

3.5.4. Kidney (Renal Cell) Cancer

3.6. Emerging Strategies: Ferroptosis, Autophagy Modulation, Nitric Oxide, and Gene Therapy

3.6.1. Ferroptosis Induction

3.6.2. Autophagy Inhibition

3.6.3. Nitric Oxide (NO) Delivery

3.6.4. Gene Therapy and RNA Interference

3.7. Stimuli-Responsive Nanotherapies: Ultrasound, Photothermal, and Sonodynamic Approaches

3.7.1. Photothermal Therapy (PTT)

3.7.2. Ultrasound and Sonodynamic Therapy (SDT)

3.7.3. Other External Triggers

3.8. Innovative and Underexplored Nanomedicine Strategies for MDR Cancers

3.8.1. Magnetic Nanoparticles for Theranostics and Targeted Therapy

3.8.2. Intratumoral Administration of Nano Drug Delivery Systems

3.8.3. Polydopamine (PDA) Nanoparticles in Drug Delivery and Immune Modulation

3.8.4. Inorganic Nanoparticles in Overcoming Resistance

3.8.5. Oral Nanoformulations for Colorectal Cancer

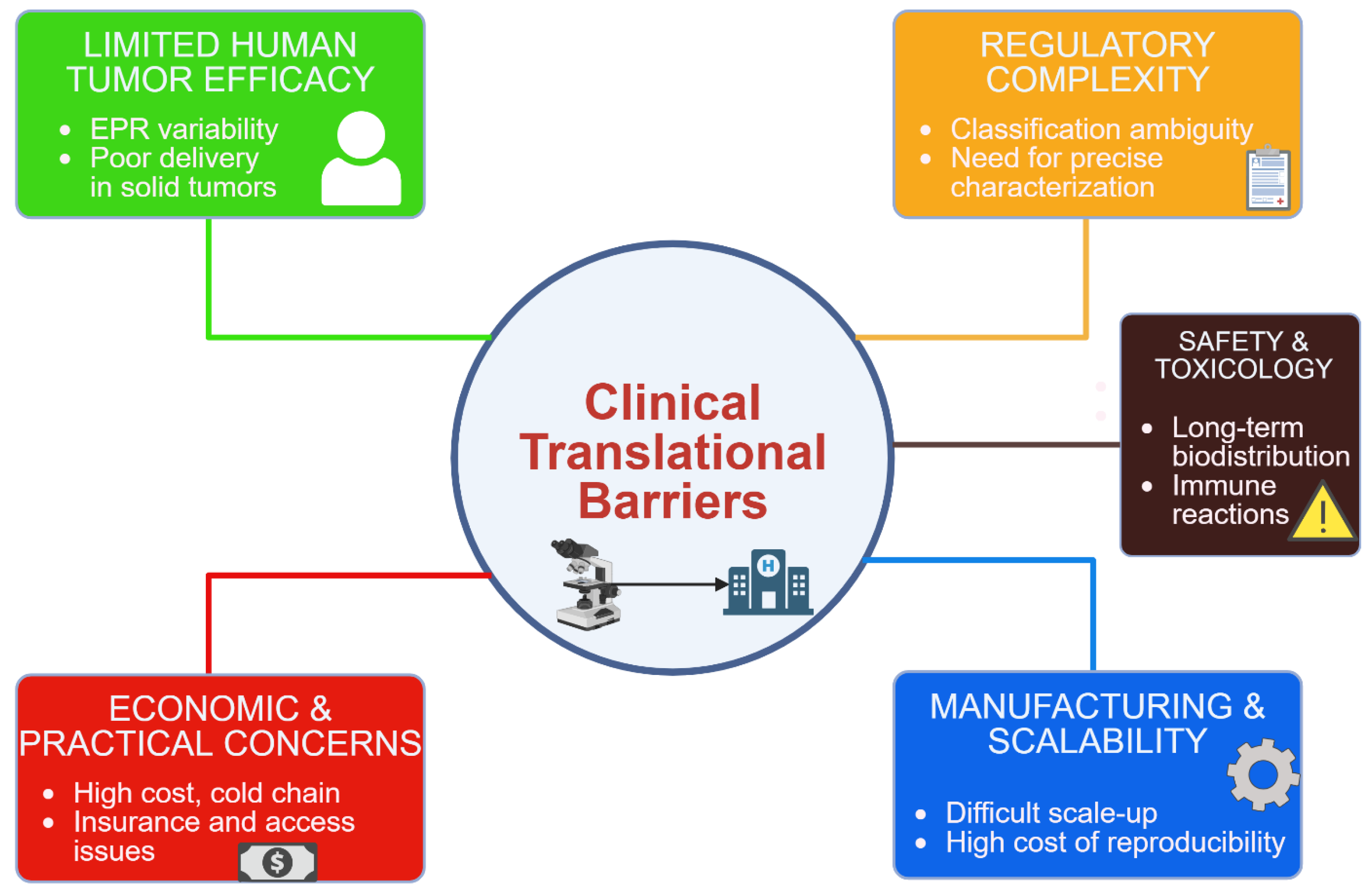

4. Clinical Translation: Limitations and Challenges

4.1. Sandardization and Characterization:

4.2. Safety and Toxicity Concerns

4.3. Manufacturing and Scalability

4.4. Efficacy in Human Tumors

4.5. Economic and Practical Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024, 74, 229–263. [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 209–249. [CrossRef]

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Parkin, D.M.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Bray, F. Cancer Statistics for the Year 2020: An Overview. Int J Cancer 2021. [CrossRef]

- Emran, T.B.; Shahriar, A.; Mahmud, A.R.; Rahman, T.; Abir, M.H.; Siddiquee, M.F.-R.; Ahmed, H.; Rahman, N.; Nainu, F.; Wahyudin, E.; et al. Multidrug Resistance in Cancer: Understanding Molecular Mechanisms, Immunoprevention and Therapeutic Approaches. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.A.; Fawell, S.; Floc’h, N.; Flemington, V.; McKerrecher, D.; Smith, P.D. Challenges and Opportunities in Cancer Drug Resistance. Chem Rev 2021, 121, 3297–3351. [CrossRef]

- Roszkowska, M. Multilevel Mechanisms of Cancer Drug Resistance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 12402. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X. Drug Resistance and Combating Drug Resistance in Cancer. Cancer Drug Resist 2019, 2, 141–160. [CrossRef]

- Vasan, N.; Baselga, J.; Hyman, D.M. A View on Drug Resistance in Cancer. Nature 2019, 575, 299–309. [CrossRef]

- Huddleston, C.; Mani, C.; Sah, N.; Courtney, E.; Reese, K.; Stroever, S.; Palle, K.; Reedy, M.B. Evaluating Efficacy of Cervical HPV-HR DNA Testing as Alternative to PET/CT Imaging for Posttreatment Cancer Surveillance: Retrospective Proof-of-Concept Study. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2025, OF1–OF5. [CrossRef]

- Huddleston, C.; Fakhreddine, A.B.; Stroever, S.; Young, R.; Sah, N.; Palle, K.; Reedy, M. Abstract 1305: Comparison of HPV-DNA Testing to PET-CT Imaging as Prognostic Test Following Definitive Treatment for Cervical Cancer: A Retrospective Proof-of-Concept Study. Cancer Research 2024, 84, 1305. [CrossRef]

- Sabir, S.; Thani, A.S.B.; Abbas, Q. Nanotechnology in Cancer Treatment: Revolutionizing Strategies against Drug Resistance. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2025, 13, 1548588. [CrossRef]

- Souri, M.; Soltani, M.; Moradi Kashkooli, F.; Kiani Shahvandi, M. Engineered Strategies to Enhance Tumor Penetration of Drug-Loaded Nanoparticles. J Control Release 2022, 341, 227–246. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Liu, X.; Lu, X.; Tian, J. Nanoparticle Drug Delivery Systems for Synergistic Delivery of Tumor Therapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Rehman, M.U.; Khan, A.; Imtiyaz, Z.; Ali, S.; Makeen, H.A.; Rashid, S.; Arafah, A. Current Nano-Therapeutic Approaches Ameliorating Inflammation in Cancer Progression. Semin Cancer Biol 2022, 86, 886–908. [CrossRef]

- Rehman, M.U.; Khan, A.; Imtiyaz, Z.; Ali, S.; Makeen, H.A.; Rashid, S.; Arafah, A. Current Nano-Therapeutic Approaches Ameliorating Inflammation in Cancer Progression. Semin Cancer Biol 2022, 86, 886–908. [CrossRef]

- Wilkens, S. Structure and Mechanism of ABC Transporters. F1000Prime Rep 2015, 7, 14. [CrossRef]

- Alfarouk, K.O.; Stock, C.-M.; Taylor, S.; Walsh, M.; Muddathir, A.K.; Verduzco, D.; Bashir, A.H.H.; Mohammed, O.Y.; Elhassan, G.O.; Harguindey, S.; et al. Resistance to Cancer Chemotherapy: Failure in Drug Response from ADME to P-Gp. Cancer Cell Int 2015, 15, 71. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Seebacher, N.; Shi, H.; Kan, Q.; Duan, Z. Novel Strategies to Prevent the Development of Multidrug Resistance (MDR) in Cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 84559–84571. [CrossRef]

- Targeting Interleukin-6 as a Strategy to Overcome Stroma-Induced Resistance to Chemotherapy in Gastric Cancer - PubMed Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30927911/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Chen, S.-Q.; Li, J.-Q.; Wang, X.-Q.; Lei, W.-J.; Li, H.; Wan, J.; Hu, Z.; Zou, Y.-W.; Wu, X.-Y.; Niu, H.-X. EZH2-Inhibitor DZNep Enhances Apoptosis of Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells in Presence and Absence of Cisplatin. Cell Div 2020, 15, 8. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.W.; Hao, W.J.; Li, Y.W.; Li, Y.X.; Zhao, B.C.; Lu, D. Hsa-miRNA-143-3p Reverses Multidrug Resistance of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer by Inhibiting the Expression of Its Target Protein Cytokine-Induced Apoptosis Inhibitor 1 In Vivo. J Breast Cancer 2018, 21, 251–258. [CrossRef]

- Venkatadri, R.; Muni, T.; Iyer, A.K.V.; Yakisich, J.S.; Azad, N. Role of Apoptosis-Related miRNAs in Resveratrol-Induced Breast Cancer Cell Death. Cell Death Dis 2016, 7, e2104. [CrossRef]

- Archer, T.C.; Ehrenberger, T.; Mundt, F.; Gold, M.P.; Krug, K.; Mah, C.K.; Mahoney, E.L.; Daniel, C.J.; LeNail, A.; Ramamoorthy, D.; et al. Proteomics, Post-Translational Modifications, and Integrative Analyses Reveal Molecular Heterogeneity within Medulloblastoma Subgroups. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 396-410.e8. [CrossRef]

- Devi, G.R.; Finetti, P.; Morse, M.A.; Lee, S.; de Nonneville, A.; Van Laere, S.; Troy, J.; Geradts, J.; McCall, S.; Bertucci, F. Expression of X-Linked Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein (XIAP) in Breast Cancer Is Associated with Shorter Survival and Resistance to Chemotherapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 2807. [CrossRef]

- Targeting P53 Pathways: Mechanisms, Structures and Advances in Therapy | Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41392-023-01347-1 (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Peiris-Pagès, M.; Bonuccelli, G.; Sotgia, F.; Lisanti, M.P. Mitochondrial Fission as a Driver of Stemness in Tumor Cells: mDIVI1 Inhibits Mitochondrial Function, Cell Migration and Cancer Stem Cell (CSC) Signalling. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 13254–13275. [CrossRef]

- Kashatus, D.F. The Regulation of Tumor Cell Physiology by Mitochondrial Dynamics. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018, 500, 9–16. [CrossRef]

- Fas Receptor - an Overview | ScienceDirect Topics Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/biochemistry-genetics-and-molecular-biology/fas-receptor (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Leonard, B.C.; Johnson, D.E. Signaling by Cell Surface Death Receptors: Alterations in Head and Neck Cancer. Adv Biol Regul 2018, 67, 170–178. [CrossRef]

- Henke, E.; Nandigama, R.; Ergün, S. Extracellular Matrix in the Tumor Microenvironment and Its Impact on Cancer Therapy. Front Mol Biosci 2020, 6, 160. [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Huang, G.; Song, H.; Chen, Y.; Chen, L. Cancer Associated Fibroblasts: An Essential Role in the Tumor Microenvironment. Oncol Lett 2017, 14, 2611–2620. [CrossRef]

- Sobanski, T.; Rose, M.; Suraweera, A.; O’Byrne, K.; Richard, D.J.; Bolderson, E. Cell Metabolism and DNA Repair Pathways: Implications for Cancer Therapy. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 633305. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, G.R.; Sethi, I.; Sadida, H.Q.; Rah, B.; Mir, R.; Algehainy, N.; Albalawi, I.A.; Masoodi, T.; Subbaraj, G.K.; Jamal, F.; et al. Cancer Cell Plasticity: From Cellular, Molecular, and Genetic Mechanisms to Tumor Heterogeneity and Drug Resistance. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2024, 43, 197–228. [CrossRef]

- Torborg, S.R.; Li, Z.; Chan, J.E.; Tammela, T. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Plasticity in Cancer. Trends Cancer 2022, 8, 735–746. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Shao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Wang, F.X.C.; Mu, J.; Li, J.; Yao, H.; Chen, K. Role of Tumor Microenvironment in Cancer Progression and Therapeutic Strategy. Cancer Med 2023, 12, 11149–11165. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.M.; Simon, M.C. Tumor Microenvironment. Curr Biol 2020, 30, R921–R925. [CrossRef]

- Hassan Venkatesh, G.; Abou Khouzam, R.; Shaaban Moustafa Elsayed, W.; Ahmed Zeinelabdin, N.; Terry, S.; Chouaib, S. Tumor Hypoxia: An Important Regulator of Tumor Progression or a Potential Modulator of Tumor Immunogenicity? Oncoimmunology 10, 1974233. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Bian, C.; Wang, H.; Su, J.; Meng, L.; Xin, Y.; Jiang, X. Prediction of Immunotherapy Efficacy and Immunomodulatory Role of Hypoxia in Colorectal Cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2022, 14, 17588359221138383. [CrossRef]

- Kazakova, A.N.; Lukina, M.M.; Anufrieva, K.S.; Bekbaeva, I.V.; Ivanova, O.M.; Shnaider, P.V.; Slonov, A.; Arapidi, G.P.; Shender, V.O. Exploring the Diversity of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts: Insights into Mechanisms of Drug Resistance. Front Cell Dev Biol 2024, 12, 1403122. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T. Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Tumor Immunity. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 583084. [CrossRef]

- Sui, H.; Dongye, S.; Liu, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, L.; Jin, C.Q.; Yao, M.; Gong, Z.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, K.; et al. Immunotherapy of Targeting MDSCs in Tumor Microenvironment. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 990463. [CrossRef]

- Gregg, C. Starvation and Climate Change—How to Constrain Cancer Cell Epigenetic Diversity and Adaptability to Enhance Treatment Efficacy. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Hajji, N.; García-Domínguez ,Daniel J; Hontecillas-Prieto ,Lourdes; O’Neill ,Kevin; de Álava ,Enrique; and Syed, N. The Bitter Side of Epigenetics: Variability and Resistance to Chemotherapy. Epigenomics 2021, 13, 397–403. [CrossRef]

- Lai, T.-Y.; Ko, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.-L.; Lin, S.-F. The Way to Malignant Transformation: Can Epigenetic Alterations Be Used to Diagnose Early-Stage Head and Neck Cancer? Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1717. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, F. Combating P-Glycoprotein-Mediated Multidrug Resistance Using Therapeutic Nanoparticles. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2013, 19, 6655–6666.

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Hao, J.; Liu, P.; Liu, X. Understanding Efflux-Mediated Multidrug Resistance in Botrytis Cinerea for Improved Management of Fungicide Resistance. Microbial Biotechnology 2025, 18, e70074. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, D.; Tang, S.; Aslam, S.; Ahmad, M.; To, K.K.W.; Wang, F.; Huang, Z.; Cai, J.; Fu, L. UMMS-4 Enhanced Sensitivity of Chemotherapeutic Agents to ABCB1-Overexpressing Cells via Inhibiting Function of ABCB1 Transporter.

- Nie, Y.; Fu, G.; Leng, Y. Nuclear Delivery of Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery Systems by Nuclear Localization Signals. Cells 2023, 12, 1637. [CrossRef]

- Kievit, F.M.; Wang, F.Y.; Fang, C.; Mok, H.; Wang, K.; Silber, J.R.; Ellenbogen, R.G.; Zhang, M. Doxorubicin Loaded Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Overcome Multidrug Resistance in Cancer in Vitro. Journal of Controlled Release 2011, 152, 76–83. [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Xu, Y.; Chen, F.; Yu, D.; Liang, H.; Liang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, J.; Tan, H.; et al. Mitochondria-Targeted and pH-Triggered Charge-Convertible Polymeric Micelles for Anticancer Therapy. Materials & Design 2022, 224, 111290. [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Dong, S.; Zeng, Q. Functional Nucleic Acid Nanostructures for Mitochondrial Targeting: The Basis of Customized Treatment Strategies. Molecules 2025, 30, 1025. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Luo, J.; Guo, W.; Sun, L.; Lin, L. Targeting M2-like Tumor-Associated Macrophages Is a Potential Therapeutic Approach to Overcome Antitumor Drug Resistance. npj Precis. Onc. 2024, 8, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, B.B.; Sousa, D.P.; Conniot, J.; Conde, J. Nanomedicine-Based Strategies to Target and Modulate the Tumor Microenvironment. Trends in Cancer 2021, 7, 847–862. [CrossRef]

- Extracellular Matrix Remodeling in Tumor Progression and Immune Escape: From Mechanisms to Treatments | Molecular Cancer | Full Text Available online: https://molecular-cancer.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12943-023-01744-8 (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Mestiri, S.; Sami, A.; Sah, N.; El-Ella, D.M.A.; Khatoon, S.; Shafique, K.; Raza, A.; Mathkor, D.M.; Haque, S. Cellular Plasticity and Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Role of T and NK Cell Immune Evasion and Acquisition of Resistance to Immunotherapies. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2025, 44, 27. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Luo, W.; Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Lou, Y.; Mao, J.; Chen, J.; Wu, F.; Hou, J.; et al. A Collagenase-Decorated Cu-Based Nanotheranostics: Remodeling Extracellular Matrix for Optimizing Cuproptosis and MRI in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. J Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22, 689. [CrossRef]

- Iqubal, M.K.; Kaur, H.; Md, S.; Alhakamy, N.A.; Iqubal, A.; Ali, J.; Baboota, S. A Technical Note on Emerging Combination Approach Involved in the Onconanotherapeutics. Drug Deliv 29, 3197–3212. [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, T.J.; Sah, N.; Palle, K.; Rumbley, J.; Mereddy, V.R. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Benzofuran Piperazine Derivatives as Potential Anticancer Agents. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2023, 93, 129425. [CrossRef]

- Gabizon, A.; Ohana, P.; Amitay, Y.; Gorin, J.; Tzemach, D.; Mak, L.; Shmeeda, H. Liposome Co-Encapsulation of Anti-Cancer Agents for Pharmacological Optimization of Nanomedicine-Based Combination Chemotherapy. Cancer Drug Resist 2021, 4, 463–484. [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.; Zhang, A.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Q.; Sun, F.; Tang, B. Nanocarriers Containing Platinum Compounds for Combination Chemotherapy. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 1050928. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Han, X.; Xiong, H.; Gao, Y.; Xu, B.; Zhu, G.; Li, J. Cancer Nanomedicine: Emerging Strategies and Therapeutic Potentials. Molecules 2023, 28, 5145. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Borlongan, M.; Hemminki, A.; Basnet, S.; Sah, N.; Kaufman, H.L.; Rabkin, S.D.; Saha, D. Viral Vectors Expressing Interleukin 2 for Cancer Immunotherapy. Human Gene Therapy 2023, 34, 878–895. [CrossRef]

- Chehelgerdi, M.; Chehelgerdi, M.; Allela, O.Q.B.; Pecho, R.D.C.; Jayasankar, N.; Rao, D.P.; Thamaraikani, T.; Vasanthan, M.; Viktor, P.; Lakshmaiya, N.; et al. Progressing Nanotechnology to Improve Targeted Cancer Treatment: Overcoming Hurdles in Its Clinical Implementation. Mol Cancer 2023, 22, 169. [CrossRef]

- YU, B.; TAI, H.C.; XUE, W.; LEE, L.J.; LEE, R.J. Receptor-Targeted Nanocarriers for Therapeutic Delivery to Cancer. Mol Membr Biol 2010, 27, 286–298. [CrossRef]

- Nethi, S.K.; Bhatnagar, S.; Prabha, S. Synthetic Receptor-Based Targeting Strategies to Improve Tumor Drug Delivery. AAPS PharmSciTech 2021, 22, 93. [CrossRef]

- Altuwaijri, N.; Atef, E. Transferrin-Conjugated Nanostructured Lipid Carriers for Targeting Artemisone to Melanoma Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 9119. [CrossRef]

- Scheeren, L.E.; Nogueira-Librelotto, D.R.; Macedo, L.B.; de Vargas, J.M.; Mitjans, M.; Vinardell, M.P.; Rolim, C.M.B. Transferrin-Conjugated Doxorubicin-Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles with pH-Responsive Behavior: A Synergistic Approach for Cancer Therapy. J Nanopart Res 2020, 22, 72. [CrossRef]

- Tosca, E.M.; Ronchi, D.; Facciolo, D.; Magni, P. Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement of Animal Experiments in Anticancer Drug Development: The Contribution of 3D In Vitro Cancer Models in the Drug Efficacy Assessment. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1058. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.S.; Barros, A.S.; Costa, E.C.; Moreira, A.F.; Correia, I.J. 3D Tumor Spheroids as in Vitro Models to Mimic in Vivo Human Solid Tumors Resistance to Therapeutic Drugs. Biotechnol Bioeng 2019, 116, 206–226. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, P.; Zou, Q.; Li, X.; Fu, J.; Luo, Y.; Liang, X.; Jin, Y. Co-Delivery of Gemcitabine and Paclitaxel in cRGD-Modified Long Circulating Nanoparticles with Asymmetric Lipid Layers for Breast Cancer Treatment. Molecules 2018, 23, 2906. [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Hwang, K.; Lu, Y. Recent Developments of Liposomes as Nanocarriers for Theranostic Applications. Theranostics 2016, 6, 1336–1352. [CrossRef]

- Macedo, L.B.; Nogueira-Librelotto, D.R.; Mathes, D.; Pieta, T.B.; Mainardi Pillat, M.; Rosa, R.M. da; Rodrigues, O.E.D.; Vinardell, M.P.; Rolim, C.M.B. Transferrin-Decorated PLGA Nanoparticles Loaded with an Organoselenium Compound as an Innovative Approach to Sensitize MDR Tumor Cells: An In Vitro Study Using 2D and 3D Cell Models. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2306. [CrossRef]

- Sah, N.; Shaik, A.A.; Acharya, G.; Dunna, M.; Silwal, A.; Sharma, S.; Khan, S.; Bagchi, S. Receptor-Based Strategies for Overcoming Resistance in Cancer Therapy. Receptors 2024, 3, 425–443. [CrossRef]

- Ashique, S.; Bhowmick, M.; Pal, R.; Khatoon, H.; Kumar, P.; Sharma, H.; Garg, A.; Kumar, S.; Das, U. Multi Drug Resistance in Colorectal Cancer- Approaches to Overcome, Advancements and Future Success. Advances in Cancer Biology - Metastasis 2024, 10, 100114. [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Liu, Y.; Yang, N.; Zhang, T.; Hou, J.; He, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.; Shen, J.; Jiang, H.; et al. Combination of miR159 Mimics and Irinotecan Utilizing Lipid Nanoparticles for Enhanced Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 570. [CrossRef]

- Sah, N.; Luna, P.; Mani, C.; Gmeiner, W.; Palle, K. Abstract 6178: A Novel Second-Generation Nano-Fluoropyrimidine to Treat Metastatic Colorectal Cancer and Overcome 5-Fluorouracil Resistance. Cancer Research 2023, 83, 6178. [CrossRef]

- Sah, N.; Luna, P.; Mani, C.; Gmeiner, W.; Palle, K. A Novel Fluoropyrimidine Drug to Treat Recalcitrant Colorectal Cancer. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 2023, 385, 441. [CrossRef]

- Okechukwu, C.C.; Ma, X.; Sah, N.; Mani, C.; Palle, K.; Gmeiner, W.H. Enhanced Therapeutic Efficacy of the Nanoscale Fluoropyrimidine Polymer CF10 in a Rat Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastasis Model. Cancers 2024, 16, 1360. [CrossRef]

- Lainetti, P. de F.; Leis-Filho, A.F.; Laufer-Amorim, R.; Battazza, A.; Fonseca-Alves, C.E. Mechanisms of Resistance to Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer and Possible Targets in Drug Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1193. [CrossRef]

- Murren, J.R.; Durivage, H.J.; Buzaid, A.C.; Reiss, M.; Flynn, S.D.; Carter, D.; Hait, W.N. Trifluoperazine as a Modulator of Multidrug Resistance in Refractory Breast Cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1996, 38, 65–70. [CrossRef]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Streltsov, D.A.; Ezhov, A.A.; Kudryashova, E.V. Smart pH- and Temperature-Sensitive Micelles Based on Chitosan Grafted with Fatty Acids to Increase the Efficiency and Selectivity of Doxorubicin and Its Adjuvant Regarding the Tumor Cells. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1135. [CrossRef]

- Butt, A.M.; Amin, M.C.I.M.; Katas, H.; Abdul Murad, N.A.; Jamal, R.; Kesharwani, P. Doxorubicin and siRNA Codelivery via Chitosan-Coated pH-Responsive Mixed Micellar Polyplexes for Enhanced Cancer Therapy in Multidrug-Resistant Tumors. Mol Pharm 2016, 13, 4179–4190. [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Song, Z.; Wu, B.; Yang, X.; Chen, F.; Wang, X. Hyaluronic Acid-Modified and Doxorubicin-Loaded Au Nanorings for Dual-Responsive and Dual-Imaging Guided Targeted Synergistic Photothermal Chemotherapy Against Pancreatic Carcinoma. Int J Nanomedicine 2024, 19, 13429–13442. [CrossRef]

- Intelligent MoS2 Nanotheranostic for Targeted and Enzyme-/pH-/NIR-Responsive Drug Delivery To Overcome Cancer Chemotherapy Resistance Guided by PET Imaging | ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces Available online: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsami.7b17506.

- Cao, Y.; Ren, Q.; Hao, R.; Sun, Z. Innovative Strategies to Boost Photothermal Therapy at Mild Temperature Mediated by Functional Nanomaterials. Materials & Design 2022, 214, 110391. [CrossRef]

- Macedo, L.B.; Nogueira-Librelotto, D.R.; Mathes, D.; Pieta, T.B.; Mainardi Pillat, M.; Rosa, R.M. da; Rodrigues, O.E.D.; Vinardell, M.P.; Rolim, C.M.B. Transferrin-Decorated PLGA Nanoparticles Loaded with an Organoselenium Compound as an Innovative Approach to Sensitize MDR Tumor Cells: An In Vitro Study Using 2D and 3D Cell Models. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2306. [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Shi, T.; Liu, J.; Pei, Z.; Liu, J.; Ren, X.; Li, F.; Qiu, F. Dual-Drug Codelivery Nanosystems: An Emerging Approach for Overcoming Cancer Multidrug Resistance. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 161, 114505. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; Cho, H.; Kim, K. Overcoming Cancer Drug Resistance with Nanoparticle Strategies for Key Protein Inhibition. Molecules 2024, 29, 3994. [CrossRef]

- Luobin, L.; Wanxin, H.; Yingxin, G.; Qinzhou, Z.; Zefeng, L.; Danyang, W.; Huaqin, L. Nanomedicine-Induced Programmed Cell Death in Cancer Therapy: Mechanisms and Perspectives. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Mao, W.; Rodriguez-Aguayo, C.; Mangala, L.S.; Bartholomeusz, G.; Iles, L.R.; Jennings, N.B.; Ahmed, A.A.; Sood, A.K.; Lopez-Berestein, G.; et al. Paclitaxel Sensitivity of Ovarian Cancer Can Be Enhanced by Knocking down Pairs of Kinases That Regulate MAP4 Phosphorylation and Microtubule Stability. Clin Cancer Res 2018, 24, 5072–5084. [CrossRef]

- Demuytere, J.; Carlier, C.; Van de Sande, L.; Hoorens, A.; De Clercq, K.; Giordano, S.; Morosi, L.; Matteo, C.; Zucchetti, M.; Davoli, E.; et al. Preclinical Activity of Two Paclitaxel Nanoparticle Formulations After Intraperitoneal Administration in Ovarian Cancer Murine Xenografts. Int J Nanomedicine 2024, 19, 429–440. [CrossRef]

- Nagumo, Y.; Villareal, M.O.; Isoda, H.; Usui, T. RSK4 Confers Paclitaxel Resistance to Ovarian Cancer Cells, Which Is Resensitized by Its Inhibitor BI-D1870. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2023, 679, 23–30. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.; Silva, P.M.A.; Coelho, R.; Pinto, C.; Resende, A.; Bousbaa, H.; Almeida, G.M.; Ricardo, S. Generation of Two Paclitaxel-Resistant High-Grade Serous Carcinoma Cell Lines With Increased Expression of P-Glycoprotein. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 752127. [CrossRef]

- Summey, R.; Uyar, D. Ovarian Cancer Resistance to PARPi and Platinum-Containing Chemotherapy. Cancer Drug Resist 2022, 5, 637–646. [CrossRef]

- The Future of Ovarian Cancer: Innovation, Treatment and Hope Available online: https://www.icr.ac.uk/about-us/icr-news/detail/the-future-of-ovarian-cancer--innovation--treatment-and-hope (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Kaur, P.; Singh, S.K.; Mishra, M.K.; Singh, S.; Singh, R. Nanotechnology for Boosting Ovarian Cancer Immunotherapy. Journal of Ovarian Research 2024, 17, 202. [CrossRef]

- Kamli, H.; Li, L.; Gobe, G.C. Limitations to the Therapeutic Potential of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors and Alternative Therapies for Kidney Cancer. Ochsner J 2019, 19, 138–151. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Gao, Y.; Duan, X.; Fu, Q.; Chu, C.; Pan, X.; Cui, X.; Sun, Y. Cuprous Oxide Nanoparticles Trigger ER Stress-Induced Apoptosis by Regulating Copper Trafficking and Overcoming Resistance to Sunitinib Therapy in Renal Cancer. Biomaterials 2017, 146, 72–85. [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Zeng, T.; Liang, X.; Wu, W.; Zhong, F.; Wu, W. Cell Death-Related Molecules and Biomarkers for Renal Cell Carcinoma Targeted Therapy. Cancer Cell International 2019, 19, 221. [CrossRef]

- Lei, G.; Tang, L.; Yu, Y.; Bian, W.; Yu, L.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Du, J. The Potential of Targeting Cuproptosis in the Treatment of Kidney Renal Clear Cell Carcinoma. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 167, 115522. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, K.; Zhang, J.; Gao, H.; Xu, X. Progress in the Treatment of Drug-Loaded Nanomaterials in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 167, 115444. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Meng, Y.; Li, D.; Yao, L.; Le, J.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zeng, F.; Chen, X.; Deng, G. Ferroptosis in Cancer: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Strategies. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 1–30. [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Xiao, W.; Hu, Z.; Liu, X.; Yuan, M. A Systematic Review of Nanoparticle-Mediated Ferroptosis in Glioma Therapy. Int J Nanomedicine 2025, 20, 5779–5797. [CrossRef]

- Carlos, A.; Mendes, M.; Cruz, M.T.; Pais, A.; Vitorino, C. Ferroptosis Driven by Nanoparticles for Tackling Glioblastoma. Cancer Letters 2025, 611, 217392. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Zhang, B.; Li, B.; Wu, H.; Jiang, M. Cold and Hot Tumors: From Molecular Mechanisms to Targeted Therapy. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 1–65. [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, A.; Mohanty, A.; Park, I.-K. Inorganic Nanomedicine—Mediated Ferroptosis: A Synergistic Approach to Combined Cancer Therapies and Immunotherapy. Cancers 2024, 16, 3210. [CrossRef]

- Acharya, G.; Mani, C.; Sah, N.; Saamarthy, K.; Young, R.; Reedy, M.B.; Sobol, R.W.; Palle, K. CHK1 Inhibitor Induced PARylation by Targeting PARG Causes Excessive Replication and Metabolic Stress and Overcomes Chemoresistance in Ovarian Cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Targeting Metabolic and DNA Damage Checkpoint Indu...: Full Text Finder Results Available online: https://resolver-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.ttuhsc.edu/openurl?sid=google&auinit=G&aulast=Acharya&atitle=Targeting+Metabolic+and+DNA+Damage+Checkpoint+Induces+Excessive+DNA+Damage+and+Causes+Synergistic+Lethality+in+GLShigh+Chemoresistant+Ovarian+Cancer+Cells&title=Environmental+and+Molecular+Mutagenesis&volume=65&date=2024&spage=18&issn=0893-6692 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Long, X.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chang, J.; He, B.; Sun, Y.; Liang, Y. Autophagy-Targeted Nanoparticles for Effective Cancer Treatment: Advances and Outlook. NPG Asia Mater 2022, 14, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Rosenkrans, Z.T.; Luo, Q.-Y.; Lan, X.; Cai, W. Exploiting Nanomaterial-Mediated Autophagy for Cancer Therapy. Small Methods 2019, 3, 1800365. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; He, J.; Li, Z.; Fan, B.; Zhang, L.; Man, X. Targeting Autophagy in Urological System Cancers: From Underlying Mechanisms to Therapeutic Implications. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 2024, 1879, 189196. [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chang, J.; He, B.; Sun, Y.; Liang, Y. Autophagy-Targeted Nanoparticles for Effective Cancer Treatment: Advances and Outlook. NPG Asia Mater 2022, 14, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Chen, M.; Liu, J.; Du, S.; Ren, C.; Zhang, J. Nanomedicine for Cancer Targeted Therapy with Autophagy Regulation. Front Immunol 2024, 14, 1238827. [CrossRef]

- Dowaidar, M. Guidelines for the Role of Autophagy in Drug Delivery Vectors Uptake Pathways. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30238. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Li, X.; Cheng, Y.; Jian, H.; Ma, X.; Zheng, R.; Wu, X.; Xu, K.; et al. Nitric Oxide Stimulated Programmable Drug Release of Nanosystem for Multidrug Resistance Cancer Therapy. Nano Lett 2019, 19, 6800–6811. [CrossRef]

- de la Cruz-Ojeda, P.; Flores-Campos, R.; Dios-Barbeito, S.; Navarro-Villarán, E.; Muntané, J. Role of Nitric Oxide in Gene Expression Regulation during Cancer: Epigenetic Modifications and Non-Coding RNAs. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 6264. [CrossRef]

- Cauwenbergh, T.; Ballet, S.; Martin, C. Peptide Hydrogel-Drug Conjugates for Tailored Disease Treatment. Materials Today Bio 2025, 31, 101423. [CrossRef]

- Falcone, N.; Ermis, M.; Tamay, D.G.; Mecwan, M.; Monirizad, M.; Mathes, T.G.; Jucaud, V.; Choroomi, A.; Barros, N.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Peptide Hydrogels as Immunomaterials and Their Use in Cancer Immunotherapy Delivery. Adv Healthc Mater 2023, 12, e2301096. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Ambudkar, S.V.; Rajendra Prasad, N. Emerging Nanotechnology-Based Therapeutics to Combat Multidrug-Resistant Cancer. J Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 423. [CrossRef]

- Ashique, S.; Garg, A.; Hussain, A.; Farid, A.; Kumar, P.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Nanodelivery Systems: An Efficient and Target-specific Approach for Drug-resistant Cancers. Cancer Med 2023, 12, 18797–18825. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Li, X.; Cheng, Y.; Jian, H.; Ma, X.; Zheng, R.; Wu, X.; Xu, K.; et al. Nitric Oxide Stimulated Programmable Drug Release of Nanosystem for Multidrug Resistance Cancer Therapy. Nano Lett 2019, 19, 6800–6811. [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilpour, D.; Ghomi, M.; Zare, E.N.; Sillanpää, M. Recent Advances in DNA Nanotechnology for Cancer Detection and Therapy: A Review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2025, 307, 142136. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.; Videira, M. Dual Approaches in Oncology: The Promise of siRNA and Chemotherapy Combinations in Cancer Therapies. Onco 2025, 5, 2. [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Liu, D.; Cao, Z.; Zheng, N.; Mao, C.; Liu, S.; He, L.; Liu, S. Research Status and Prospect of Non-Viral Vectors Based on siRNA: A Review. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 3375. [CrossRef]

- Yhee, J.Y.; Song, S.; Lee, S.J.; Park, S.-G.; Kim, K.-S.; Kim, M.G.; Son, S.; Koo, H.; Kwon, I.C.; Jeong, J.H.; et al. Cancer-Targeted MDR-1 siRNA Delivery Using Self-Cross-Linked Glycol Chitosan Nanoparticles to Overcome Drug Resistance. Journal of Controlled Release 2015, 198, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Mir, S.A.; Hamid, L.; Bader, G.N.; Shoaib, A.; Rahamathulla, M.; Alshahrani, M.Y.; Alam, P.; Shakeel, F. Role of Nanotechnology in Overcoming the Multidrug Resistance in Cancer Therapy: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 6608. [CrossRef]

- Maimaitijiang, A.; He, D.; Li, D.; Li, W.; Su, Z.; Fan, Z.; Li, J. Progress in Research of Nanotherapeutics for Overcoming Multidrug Resistance in Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 9973. [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Mai, W.X.; Zhang, H.; Xue, M.; Xia, T.; Lin, S.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Ji, Z.; Zink, J.I.; et al. Co-Delivery of an Optimal Drug/siRNA Combination Using Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticle to Overcome Drug Resistance in Breast Cancer In Vitro and In Vivo. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 994–1005. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-K.; Cheong, H.; Kim, M.-Y.; Jin, H.-E. Therapeutic Targeting in Ovarian Cancer: Nano-Enhanced CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing and Drug Combination Therapy. Int J Nanomedicine 2025, 20, 3907–3931. [CrossRef]

- Omy, T.R.; Sah, N.; Reedy, M.; Acharya, G.; Palle, K. Abstract 3090: miRNA-221-5p-Mediated Epigenetic Regulation Promotes Chemoresistance and Offers Therapeutic Potential in Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Research 2025, 85, 3090. [CrossRef]

- Sah, N.; Peddibhotla, S.; Richardson, B.; Luna, P.; Bansal, N.A.; Mani, C.; Reedy, M.; Palle, K. Abstract A084: Oncogenic Role for Upregulated Lymphoblastic Leukemia Derived Sequence-1 in the Progression of Ovarian Cancer and Its Metastasis. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2023, 32, A084. [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Liu, D.; Cao, Z.; Zheng, N.; Mao, C.; Liu, S.; He, L.; Liu, S. Research Status and Prospect of Non-Viral Vectors Based on siRNA: A Review. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 3375. [CrossRef]

- Maimaitijiang, A.; He, D.; Li, D.; Li, W.; Su, Z.; Fan, Z.; Li, J. Progress in Research of Nanotherapeutics for Overcoming Multidrug Resistance in Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 9973. [CrossRef]

- Agiba, A.M.; Arreola-Ramírez, J.L.; Carbajal, V.; Segura-Medina, P. Light-Responsive and Dual-Targeting Liposomes: From Mechanisms to Targeting Strategies. Molecules 2024, 29, 636. [CrossRef]

- Rout, B.; Maharana, S.K.; Jain, A. Stimuli-Responsive Nanoparticles: A Novel Approach for Melanoma Treatment. J Nanopart Res 2025, 27, 34. [CrossRef]

- Szwed, M.; Jost, T.; Majka, E.; Gharibkandi, N.A.; Majkowska-Pilip, A.; Frey, B.; Bilewicz, A.; Fietkau, R.; Gaipl, U.; Marczak, A.; et al. Pt-Au Nanoparticles in Combination with Near-Infrared-Based Hyperthermia Increase the Temperature and Impact on the Viability and Immune Phenotype of Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 1574. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhang, S.; Tian, Y.; Cheng, W.; Jing, H. Research Progress of Nanomedicine-Based Mild Photothermal Therapy in Tumor. Int J Nanomedicine 2023, 18, 1433–1468. [CrossRef]

- Gold Nanoparticles in Photothermal Therapy - CD Bioparticles Available online: https://www.cd-bioparticles.com/support/gold-nanoparticles-in-photothermal-therapy.html (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Ayana, G.; Ryu, J.; Choe, S. Ultrasound-Responsive Nanocarriers for Breast Cancer Chemotherapy. Micromachines (Basel) 2022, 13, 1508. [CrossRef]

- Pourmadadi, M.; Tajiki, A.; Hosseini, S.M.; Samadi, A.; Abdouss, M.; Daneshnia, S.; Yazdian, F. A Comprehensive Review of Synthesis, Structure, Properties, and Functionalization of MoS2; Emphasis on Drug Delivery, Photothermal Therapy, and Tissue Engineering Applications. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2022, 76, 103767. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-H.; Lu, I.-L.; Liu, T.-I.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Chiang, W.-H.; Lin, S.-C.; Chiu, H.-C. Indocyanine Green/Doxorubicin-Encapsulated Functionalized Nanoparticles for Effective Combination Therapy against Human MDR Breast Cancer. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2019, 177, 294–305. [CrossRef]

- Awad, N.S.; Paul, V.; AlSawaftah, N.M.; ter Haar, G.; Allen, T.M.; Pitt, W.G.; Husseini, G.A. Ultrasound-Responsive Nanocarriers in Cancer Treatment: A Review. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 2021, 4, 589–612. [CrossRef]

- Al Refaai, K.A.; AlSawaftah, N.A.; Abuwatfa, W.; Husseini, G.A. Drug Release via Ultrasound-Activated Nanocarriers for Cancer Treatment: A Review. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1383. [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Hu, D.; Yuan, L.; Yu, Y.; Li, Y.; Qian, Z. Newly Developed Gas-Assisted Sonodynamic Therapy in Cancer Treatment. Acta Pharm Sin B 2023, 13, 2926–2954. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Hu, J.-R.; Tian, Y.; Lei, Y.-M.; Hu, H.-M.; Lei, B.-S.; Zhang, G.; Sun, Y.; Ye, H.-R. Nanosensitizer-Assisted Sonodynamic Therapy for Breast Cancer. J Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 281. [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Shu, H.; Su, C.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, T.; Nie, F. cRGD-Targeted Gold-Based Nanoparticles Overcome EGFR-TKI Resistance of NSCLC via Low-Temperature Photothermal Therapy Combined with Sonodynamic Therapy. Biomater. Sci. 2023, 11, 1677–1691. [CrossRef]

- Collins, V.G.; Hutton, D.; Hossain-Ibrahim, K.; Joseph, J.; Banerjee, S. The Abscopal Effects of Sonodynamic Therapy in Cancer. Br J Cancer 2025, 132, 409–420. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, M.; Tu, K. The Crosstalk between Sonodynamic Therapy and Autophagy in Cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.-G.; Park, J.-H.; Khang, D. Sonodynamic and Acoustically Responsive Nanodrug Delivery System: Cancer Application. Int J Nanomedicine 2024, 19, 11767–11788. [CrossRef]

- Foglietta, F.; Giacone, M.; Durando, G.; Canaparo, R.; Serpe, L. Sonodynamic Treatment Triggers Cancer Cell Killing by Doxorubicin in P-Glycoprotein-Mediated Multidrug Resistant Cancer Models. Advanced Therapeutics 2024, 7, 2400070. [CrossRef]

- Tharkar, P.; Varanasi, R.; Wong, W.S.F.; Jin, C.T.; Chrzanowski, W. Nano-Enhanced Drug Delivery and Therapeutic Ultrasound for Cancer Treatment and Beyond. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2019, 7, 324. [CrossRef]

- Bañobre-López, M.; Teijeiro, A.; Rivas, J. Magnetic Nanoparticle-Based Hyperthermia for Cancer Treatment. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother 2013, 18, 397–400. [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, C.; Jin, B.; Sun, T.; Sun, K.; Wang, S.; Fan, Z. Advances in Smart Nanotechnology-Supported Photodynamic Therapy for Cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Chen, W.; Clement, S.; Guller, A.; Zhao, Z.; Engel, A.; Goldys, E.M. Controlled Gene and Drug Release from a Liposomal Delivery Platform Triggered by X-Ray Radiation. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 2713. [CrossRef]

- Gibney, M. X-Ray-Triggered Liposomes Deliver Precisely Controlled Cancer Treatment | Fierce Pharma Available online: https://www.fiercepharma.com/r-d/x-ray-triggered-liposomes-deliver-precisely-controlled-cancer-treatment (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Lv, W.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Shu, H.; Su, C.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, T.; Nie, F. cRGD-Targeted Gold-Based Nanoparticles Overcome EGFR-TKI Resistance of NSCLC via Low-Temperature Photothermal Therapy Combined with Sonodynamic Therapy. Biomater. Sci. 2023, 11, 1677–1691. [CrossRef]

- Spoială, A.; Ilie, C.-I.; Motelica, L.; Ficai, D.; Semenescu, A.; Oprea, O.-C.; Ficai, A. Smart Magnetic Drug Delivery Systems for the Treatment of Cancer. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 876. [CrossRef]

- BSN, A.B.B.L. Magnetic Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery Available online: https://www.news-medical.net/health/Magnetic-Nanoparticles-for-Drug-Delivery.aspx (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Ren, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, B.; Cheng, J.; Cai, X.; Liu, R.; Xia, G.; Wu, W.; Wang, S.; Ding, J.; et al. Multifunctional Magnetic Fe3O4 Nanoparticles Combined with Chemotherapy and Hyperthermia to Overcome Multidrug Resistance. Int J Nanomedicine 2012, 7, 2261–2269. [CrossRef]

- Yun, W.S.; Kim, J.; Lim, D.-K.; Kim, D.-H.; Jeon, S.I.; Kim, K. Recent Studies and Progress in the Intratumoral Administration of Nano-Sized Drug Delivery Systems. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2225. [CrossRef]

- Katopodi, T.; Petanidis, S.; Floros, G.; Porpodis, K.; Kosmidis, C. Hybrid Nanogel Drug Delivery Systems: Transforming the Tumor Microenvironment through Tumor Tissue Editing. Cells 2024, 13, 908. [CrossRef]

- Koirala, M.; DiPaola, M. Overcoming Cancer Resistance: Strategies and Modalities for Effective Treatment. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1801. [CrossRef]

- Acter, S.; Moreau, M.; Ivkov, R.; Viswanathan, A.; Ngwa, W. Polydopamine Nanomaterials for Overcoming Current Challenges in Cancer Treatment. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1656. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Gong, H.; Gao, M.; Zhu, W.; Sun, X.; Feng, L.; Fu, T.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z. Polydopamine Nanoparticles as a Versatile Molecular Loading Platform to Enable Imaging-Guided Cancer Combination Therapy. Theranostics 2016, 6, 1031–1042. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, B.; Xu, Q.; Mao, W.; Tian, J.; Yang, K.; Wang, F. Radionuclide Imaging-Guided Chemo-Radioisotope Synergistic Therapy Using a 131I-Labeled Polydopamine Multifunctional Nanocarrier. Mol Ther 2018, 26, 1385–1393. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Lin, X.; Liu, F.; Sun, X.; Song, K.; Jiang, C.; Zhao, F.; Li, X. Bioactive Polydopamine Nanomedicines-Assisted Cancer Immunotherapy. Materials Today Bio 2025, 32, 101864. [CrossRef]

- Długosz, O.; Matyjasik, W.; Hodacka, G.; Szostak, K.; Matysik, J.; Krawczyk, P.; Piasek, A.; Pulit-Prociak, J.; Banach, M. Inorganic Nanomaterials Used in Anti-Cancer Therapies:Further Developments. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1130. [CrossRef]

- Newton Amaldoss, M.J.; Sorrell, C.C. ROS Modulating Inorganic Nanoparticles: A Novel Cancer Therapeutic Tool. Recent Adv Drug Deliv Formul 2022, 16, 84–89. [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, A.; Mohanty, A.; Park, I.-K. Inorganic Nanomedicine—Mediated Ferroptosis: A Synergistic Approach to Combined Cancer Therapies and Immunotherapy. Cancers 2024, 16, 3210. [CrossRef]

- Bharde, A. Targeting Redox Homeostasis in Tumor Cells Using Nanoparticles. In Handbook of Oxidative Stress in Cancer: Therapeutic Aspects; Springer, Singapore, 2022; pp. 1–17 ISBN 9789811612473.

- Pareek, A.; Kumar, D.; Pareek, A.; Gupta, M.M. Advancing Cancer Therapy with Quantum Dots and Other Nanostructures: A Review of Drug Delivery Innovations, Applications, and Challenges. Cancers (Basel) 2025, 17, 878. [CrossRef]

- He, Z.-Y.; Jin, Z.-H.; Zhan, M.; Qin, Z.; Li, Z.; Xu, T. Advances in Quantum Dot-Mediated siRNA Delivery. Chinese Chemical Letters 2017, 28, 1851–1856. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Chen, L.; Huang, W.; Gao, Z.; Jin, M. Current Advances of Nanomaterial-Based Oral Drug Delivery for Colorectal Cancer Treatment. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 557. [CrossRef]

- Kanojia, N.; Thapa, K.; Verma, N.; Rani, L.; Sood, P.; Kaur, G.; Dua, K.; Kumar, J. Update on Mucoadhesive Approaches to Target Drug Delivery in Colorectal Cancer. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2023, 87, 104831. [CrossRef]

- Gvozdeva, Y.; Staynova, R. pH-Dependent Drug Delivery Systems for Ulcerative Colitis Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 226. [CrossRef]

- Jakobušić Brala, C.; Karković Marković, A.; Kugić, A.; Torić, J.; Barbarić, M. Combination Chemotherapy with Selected Polyphenols in Preclinical and Clinical Studies—An Update Overview. Molecules 2023, 28, 3746. [CrossRef]

- C. de S. L. Oliveira, A.L.; Schomann, T.; de Geus-Oei, L.-F.; Kapiteijn, E.; Cruz, L.J.; de Araújo Junior, R.F. Nanocarriers as a Tool for the Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1321. [CrossRef]

- 4dm1n_diversatechnologies Overcoming Regulatory Hurdles in Clinical Translation of Nanomedicine. DIVERSA 2025.

- Foulkes, R.; Man, E.; Thind, J.; Yeung, S.; Joy, A.; Hoskins, C. The Regulation of Nanomaterials and Nanomedicines for Clinical Application: Current and Future Perspectives. Biomater Sci 2020, 8, 4653–4664. [CrossRef]

- Agrahari, V.; and Hiremath, P. Challenges Associated and Approaches for Successful Translation of Nanomedicines Into Commercial Products. Nanomedicine 2017, 12, 819–823. [CrossRef]

- Desai, N. Challenges in Development of Nanoparticle-Based Therapeutics. AAPS J 2012, 14, 282–295. [CrossRef]

- Safety Concerns with Nanotechnology in Medicine - Society for Brain Mapping and Therapeutics 2024.

- Dobrovolskaia, M.A.; Aggarwal, P.; Hall, J.B.; McNeil, S.E. Preclinical Studies To Understand Nanoparticle Interaction with the Immune System and Its Potential Effects on Nanoparticle Biodistribution. Mol Pharm 2008, 5, 487–495. [CrossRef]

- Desai, N. Challenges in Development of Nanoparticle-Based Therapeutics. AAPS J 2012, 14, 282–295. [CrossRef]

- Bedőcs, P.; Szebeni, J. The Critical Choice of Animal Models in Nanomedicine Safety Assessment: A Lesson Learned From Hemoglobin-Based Oxygen Carriers. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 584966. [CrossRef]

- Sah, N.; Ramaiah, B.; Koneri, R. Sulfasalazine-Induced Drug Rash with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms Syndrome in a Seronegative Spondyloarthritis Patient: A Case Report. Indian Journal of Pharmacology 2021, 53, 391. [CrossRef]

- Varghese, J.; Sah, N.; Ramaiah, B. PDG50 Obstacles in the IV to ORAL Antibiotic Shift for Eligible Patients at a Tertiary Care Hospital. Value in Health 2020, 23, S527. [CrossRef]

- Sah, N.; Ramaiah, B.; Abdulla; Gupta, A.K.; Thomas, S.M. Noncompliance with Prescription-Writing Guidelines in an OutpatientDepartment of a Tertiary Care Hospital: A Prospective, Observational Study. rjps 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Varghese, J.; Sah, N.; Thomas, S.M.; Jose, J.C.; Ramaiah, B.; Koneri, R. PDG6 Clinical Evaluation of Skin and Soft Tissue Infections in Inpatient Versus Outpatient Setting at a Tertiary Care Hospital - a Prospective Study. Value in Health 2020, 23, S521–S522. [CrossRef]

- Sah, N.; Ramaiah, B.; Koneri, R. The Pharmacist Role in Clinical Audit at an Indian Accredited Hospital: An Interventional Study. IJOPP 2019, 12, 117–125. [CrossRef]

- 4dm1n_diversatechnologies Overcoming Regulatory Hurdles in Clinical Translation of Nanomedicine. DIVERSA 2025.

- Agrahari, V.; and Hiremath, P. Challenges Associated and Approaches for Successful Translation of Nanomedicines Into Commercial Products. Nanomedicine 2017, 12, 819–823. [CrossRef]

- Agrahari, V.; and Hiremath, P. Challenges Associated and Approaches for Successful Translation of Nanomedicines Into Commercial Products. Nanomedicine 2017, 12, 819–823. [CrossRef]

- Clark, B. Lab to Industry: Scaling Up Nanotechnology for Practical Applications. Journal of Nanomaterials & Molecular Nanotechnology 2024, 2024.

- Policy Statements & Letters | Advocacy | ASGCT - American Society of Gene & Cell Therapy | ASGCT - American Society of Gene & Cell Therapy Available online: https://www.asgct.org/advocacy/policy-statement-landing/2023/manufacturing-changes-and-comparability-for-human (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Nguyen, H.-M.; Sah, N.; Humphrey, M.R.M.; Rabkin, S.D.; Saha, D. Growth, Purification, and Titration of Oncolytic Herpes Simplex Virus. J Vis Exp 2021, 10.3791/62677. [CrossRef]

- Nanomedicine Market Share, Size & Growth Report | 2032 Available online: https://www.skyquestt.com/report/nanomedicine-market (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Đorđević, S.; Gonzalez, M.M.; Conejos-Sánchez, I.; Carreira, B.; Pozzi, S.; Acúrcio, R.C.; Satchi-Fainaro, R.; Florindo, H.F.; Vicent, M.J. Current Hurdles to the Translation of Nanomedicines from Bench to the Clinic. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2022, 12, 500–525. [CrossRef]

- Navigating Nanomedicine Regulatory Requirements in 2024 Available online: https://www.izon.com/news/navigating-nanomedicine-regulatory-requirements-in-2023 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Richmond, A.; Su, Y. Mouse Xenograft Models vs GEM Models for Human Cancer Therapeutics. Dis Model Mech 2008, 1, 78–82. [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Pan, D.; Gong, Q.; Gu, Z.; Luo, K. Enhancing Drug Penetration in Solid Tumors via Nanomedicine: Evaluation Models, Strategies and Perspectives. Bioactive Materials 2024, 32, 445–472. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Dou, H.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, S.; Xiao, M. Extracellular Matrix Remodeling in Tumor Progression and Immune Escape: From Mechanisms to Treatments. Molecular Cancer 2023, 22, 48. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Cho, H.; Lim, D.-K.; Joo, M.K.; Kim, K. Perspectives for Improving the Tumor Targeting of Nanomedicine via the EPR Effect in Clinical Tumors. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 10082. [CrossRef]

- Swetha, K.L.; Roy, A. Tumor Heterogeneity and Nanoparticle-Mediated Tumor Targeting: The Importance of Delivery System Personalization. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2018, 8, 1508–1526. [CrossRef]

- Ph.D, D.P.B. Nanomedicine: Advantages and Disadvantages Available online: https://www.azonano.com/article.aspx?ArticleID=6707 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Bosetti, R.; and Jones, S.L. Cost–Effectiveness of Nanomedicine: Estimating the Real Size of Nano-Costs. Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 1367–1370. [CrossRef]

- Hejmady, S.; Singhvi ,Gautam; Saha ,Ranendra Narayan; and Dubey, S.K. Regulatory Aspects in Process Development and Scale-up of Nanopharmaceuticals. Therapeutic Delivery 2020, 11, 341–343. [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Adhikari, S.; Deka, D.; Baildya, N.; Sahare, P.; Banerjee, A.; Paul, S.; Bisgin, A.; Pathak, S. An Updated Review on the Role of Nanoformulated Phytochemicals in Colorectal Cancer. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023, 59, 685. [CrossRef]

- Degobert, G.; Aydin, D. Lyophilization of Nanocapsules: Instability Sources, Formulation and Process Parameters. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1112. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, B.; Anderson, A.; Lakey, K.; Hickham, L.; Sah, N.; Mani, C.; Palle, K.; Reedy, M. Assessing the Need and Implementation of Health Literacy Testing for New Gynecologic Oncology Patients in West Texas: A Prospective Pilot Study. Texas Public Health Journal 2025, 77, 18–24.

- Wei, A.; Mehtala, J.G.; Patri, A.K. Challenges and Opportunities in the Advancement of Nanomedicines. J Control Release 2012, 164, 236–246. [CrossRef]

- Deb, T. Nanomedicine Statistics and Facts (2025). Market.us Media 2025.

- Rodríguez-Gómez, F.D.; Monferrer, D.; Penon, O.; Rivera-Gil, P. Regulatory Pathways and Guidelines for Nanotechnology-Enabled Health Products: A Comparative Review of EU and US Frameworks. Front Med (Lausanne) 2025, 12, 1544393. [CrossRef]

- Tracey, S.R.; Smyth, P.; Barelle, C.J.; Scott, C.J. Development of next Generation Nanomedicine-Based Approaches for the Treatment of Cancer: We’ve Barely Scratched the Surface. Biochem Soc Trans 2021, 49, 2253–2269. [CrossRef]

- 4dm1n_diversatechnologies Overcoming Regulatory Hurdles in Clinical Translation of Nanomedicine. DIVERSA 2025.

- Clinical Trial Designs Incorporating Predictive Biomarkers. Available online: https://www.broadinstitute.org/publications/broad7862 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Wang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Wong, K.-C.; Li, X. Nature-Inspired Multiobjective Patient Stratification from Cancer Gene Expression Data. Information Sciences 2020, 526, 245–262. [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Xie, J.; Yang, F.; Luo, Y.; Du, J.; Xiang, H. Advances and Prospects of Precision Nanomedicine in Personalized Tumor Theranostics. Front Cell Dev Biol 2024, 12, 1514399. [CrossRef]

| Stimulus | Mechanism (effects) | Representative Cancer Model/Type |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound (US)/SDT | Cavitation increases drug uptake; triggers ROS from sonosensitizers (deep penetration) | Pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, brain (glioblastoma) |

| Photothermal (PTT) | NIR light → nanoparticle heats tumor (45–60°C), causing protein denaturation and cell death (efflux-independent) | Skin, head/neck, breast tumors (where NIR penetrates) |

| Chemophotodynamic (PDT) | Light activates photosensitizer → ROS (singlet O₂); synergizes with chemo | Superficial tumors, MDR melanoma models |

| Sonodynamic (US + sensitizer) | Ultrasound activates sensitizer → ROS; deep-tissue effect | Deep tumors (brain, pancreas) |

| Hyperthermia | Elevated temperature triggers drug release (thermosensitive liposomes) and tumor cell death | Liver (HCC), prostate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).