1. Introduction

When researching speaker cabinets or enclosures, it is essential to consider the predominant use of wood and wood-based materials in the industry. Agglomerated materials are often preferred for their uniform properties, however, the distinct properties of solid wood are significant and should not be underestimated [

1,

2]. Solid wood is characterized not only by its unique aesthetics, but also by its natural composition, which is particularly valued in the current context [

3].

In this research, we focused on the potential use and increase of the added value of preparatory wood species, especially birch. In the climatic conditions of the Czech Republic, birch is an underappreciated preparation tree, but its properties and parameters make it certainly not an inferior tree. It is anticipated that with the projected decline of currently dominant commercial species, the prevalence of pioneer tree species in forest stands will rise. Consequently, the volume of wood from these species available on the market will also increase. Although often undervalued and considered to have lower economic worth, the potential of pioneer tree species for various applications has been extensively documented by several researchers [

4,

5,

6,

7]. For instance, Borůvka et al. [

8] clearly demonstrated the feasibility of substituting beech wood with birch. Li et al. [

9] highlighted the importance of leveraging this knowledge to promote the use of these species in products with higher added value. Among the pioneer species, birch has been the most extensively studied, though in certain regions it is regarded not as a pioneer, but as a key commercial species. Studies on birch wood in Central Europe have been conducted by Borůvka et al. [

8] and Dudík et al. [

10]. In general, it will be necessary to pay attention to birch as such in Europe not only from the point of view of changes in climatic conditions, but also in a socio-economic context [

11].

As observed in research [

12] birch wood shows the highest values of acoustic wave resistance for both methods used to determine this parameter. In the ultrasonic method, birch wood had an average acoustic resistance value of 33.3·10-5 kg/m

2·s and in the resonance method it was 32.6·10-5 kg/m

2·s. In the case of maple wood, the mean acoustic resistance values were lower in both cases, they were measured at 25.9·10-5 kg/m

2·s for the ultrasonic method and 24.9·10-5 kg/m

2·s for the resonance method. Birch wood achieved also the highest mean values of the acoustic constant in both measurements, reaching 8.5 m

4/kg·s in the ultrasonic method and 8.1 m

4/kg·s in the resonance method. Požgaj et al. [

13] reported slightly lower values for this wood species, at 7.5 m

4/kg·s. For maple, values of 7.1 and 6.8 m

4/kg·s were observed, which are higher than those reported by Požgaj et al. [

13] and Bucur [

14] in their work on maple wood, where a value of 5.8 m

4/kg·s was cited.

The acoustic performance of loudspeakers is profoundly influenced by the construction of their enclosures, including factors such as shape and material properties [

15]. While conventional shapes and commonly used materials dominate the market, they do not always produce optimal sound quality. This study seeks to investigate the impact of various design elements on the sonic performance of loudspeakers using Sound Pressure Level (SPL) measurements and focuses on how these factors can improve or degrade sound output [

16]. Design plays an important role in this issue, and it is in the design and construction of speakers that there is potential for possible innovations and improvements in the frequency characteristics of individual speakers [

17].

2. Materials and Methods

Birch was chosen as a representative of the preparatory wood and therefore also the input wood for production. At the same time, thanks to its properties, it offers itself as an ideal raw material for the production of speaker enclosures, as a product with added value. For comparison, we present the density values of birch for the production of baffles which was 630 ± 31 (AVE ± SD) kg/m3 and medium density fibreboard (MDF), as a material often used for these purposes (749 ± 7 kg/m3). At the same time, we present the density of maple (602 ± 18 kg/m3), which was also used in the past for the production of identical baffles as a representative of wood with good acoustic properties used, among other things, for the production of acoustic musical instruments.

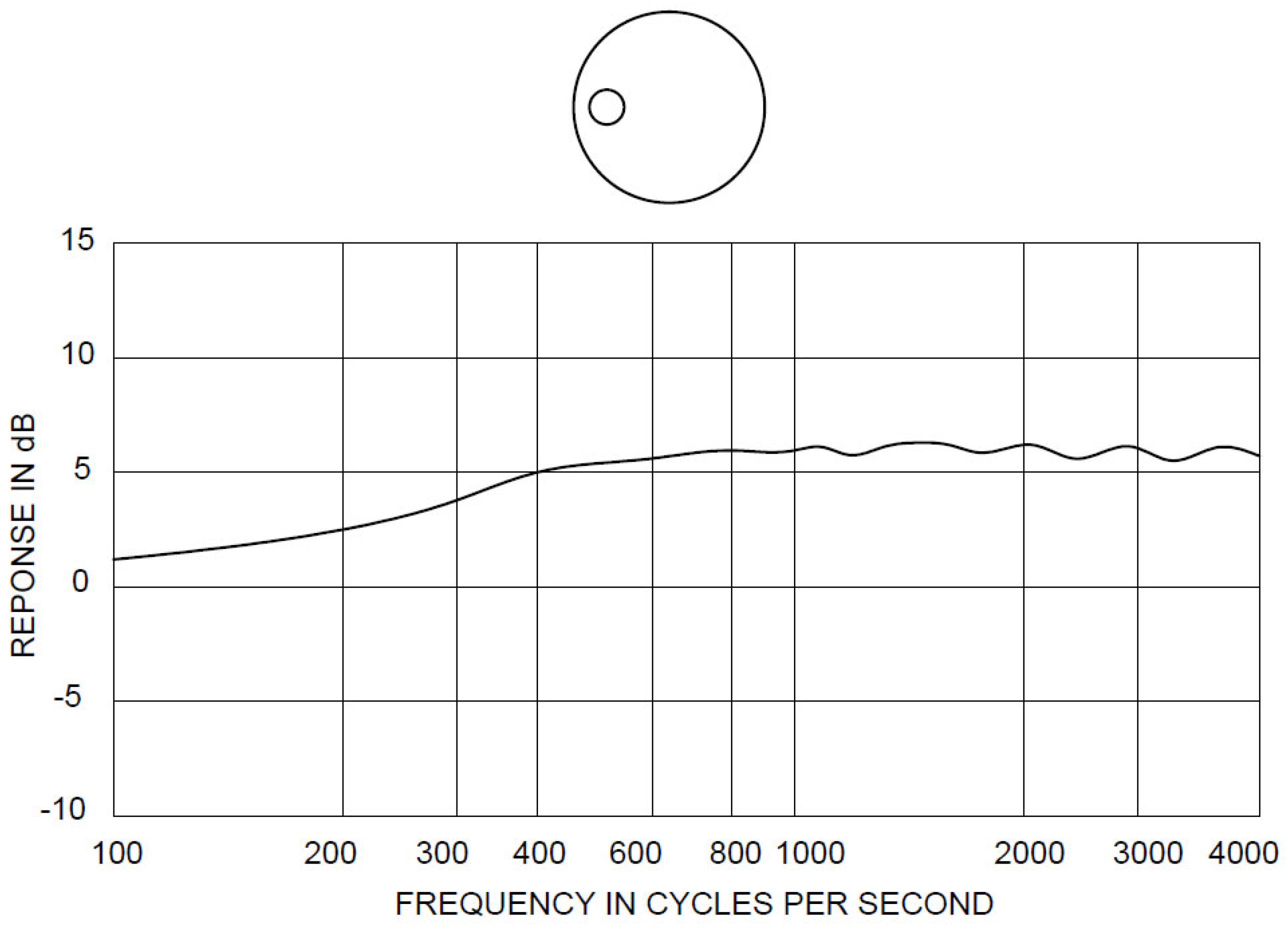

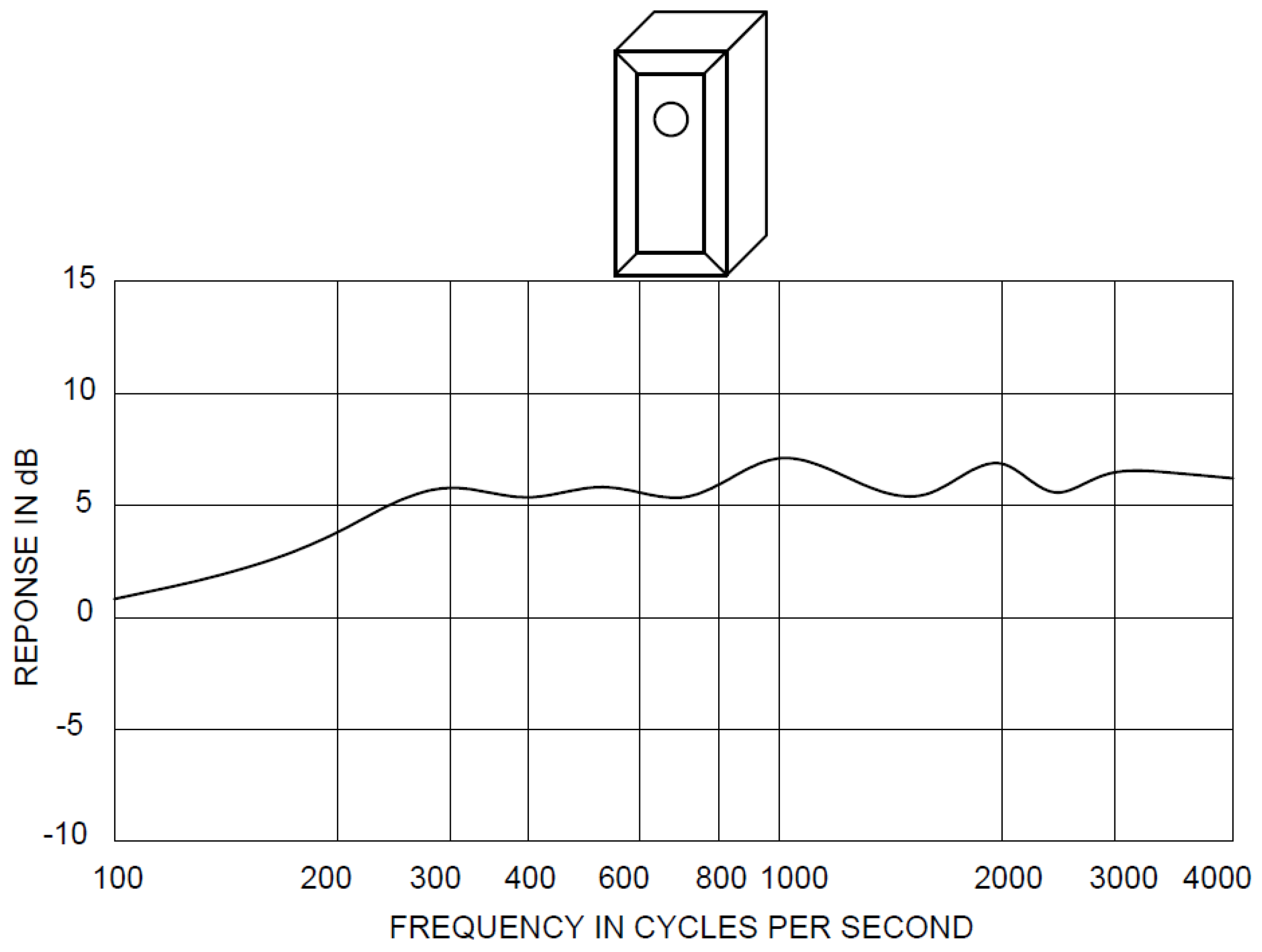

At the beginning, a design proposal was created, which was based on the already known resonance characteristics of basic geometric shapes. The spherical shape of the enclosure

Figure 1 shows the smoothest curve, and the block with beveled front edges with an eccentric speaker behaves well (

Figure 2) But the spherical shape of the baffle is very complicated to manufacture. At the same time, the goal was to create a new design that would stand out among several loudspeaker enclosures due to its uniqueness. We decided on an interesting combination of already known shapes and this resulted in a new sound box in the shape of a drop.

2.1. Production of Enclosures

The basis for this study was the creation of two types of baffles. In the first case, it is a hand-made baffle according to the design proposal, as you can see in

Figure 3. This baffle was made using a lathe from naturally weathered birch wood. The second variant is a sound box of classic cubic shape (

Figure 4), which was made using CNC technology from the same birch wood trunk. The same wood species offers an ideal opportunity to compare the design drop-shape sound box with the well-known block shape. Each shape of the enclosure was produced three times, and the frequency characteristics were measured on all six enclosures in order to eliminate manufacturing errors as much as possible, which could show up during the measurement.

Speaker driver that was used to measure the characteristics of the individual enclosures was the same each time to make the results comparable. It was specifically a Dayton RS 75-4 converter. The inverter characteristics are described in

Table 1 below.

2.2. Software and Measurements

Utilizing the Room EQ Wizard (REW) software for room acoustics and audio analysis we measured Sound Pressure Level (SPL). This is a crucial metric in audio engineering, as it quantifies how loud a sound is perceived and is essential for evaluating the performance of audio equipment, including loudspeakers. The sound pressure level is defined as.

where

p is the acoustic pressure and

pref is a reference pressure. The factor of

20 comes from the fact that the intensity of the sound wave is proportional to

p2. For sound in air, the reference pressure is defined as

20 μPa (2×10−5 Pa).

Measuring Sound Pressure Level is essential for understanding and optimizing loudspeaker performance. By using REW software, you can easily conduct precise SPL measurements, analyse frequency responses, and make informed decisions to enhance audio quality in various environments. Whether for home audio setups or professional sound systems, SPL measurements provide valuable insights into loudspeaker behaviour and acoustic performance [

18].

In

Figure 5 we can see the user interface of the REW software. This software is used to measure the sound pressure level (SPL), which we deal with in this article. In addition, also for other measurements like: Frequency Response-Measures how different frequencies are reproduced by your loudspeaker or audio system. Impulse Response-Captures how a system reacts to a short burst of sound. Waterfall Plot Analysis-Visualizes the decay of sound over time for different frequencies. Phase Response Measurement-Analyzes the phase relationship between different frequencies. Room Mode Calculations-Identifies problematic low-frequency resonances in a room. Cumulative Spectral Decay Plot-Displays energy decay over time for different frequencies. Equalization Suggestions-Generates recommendations for EQ adjustments based on measured frequency response. Speaker and Microphone Calibration-Allows for the calibration of measurement microphones to ensure accurate readings. Provides a means to correct microphone sensitivity and frequency response. Multi-Channel Measurements-Supports measurements for surround sound systems and multi-channel setups. Comparison of Measurements-Enables users to overlay different measurement graphs to compare performance under various conditions (e.g., different speaker placements or settings).

In this study, we employed the retuned harmonic signal method, commonly referred to as “retuned sine” or “Sine Sweep” [

19]. This technique was implemented to accurately measure the loudspeaker’s impulse response. The methodology involves exciting the system with a harmonic signal whose frequency increases over time in an exponential manner. The system’s response to this signal is recorded, enabling the extraction of the impulse response through subsequent processing. This can be achieved either by filtering the recorded signal with an inverse filter or by performing division in the spectral domain, though the latter method does have certain limitations [

20].

One of the significant advantages of using the retuned harmonic signal method is its ability to separate harmonic distortions from the primary response, thereby providing a clearer and more accurate measurement of the loudspeaker’s performance. For this study, the measurements were conducted at a high sampling frequency of 192 kHz with a 16-bit depth, ensuring a detailed capture of the audio signal. The duration of the sine sweep was set to 512,000 samples, equivalent to 2.7 seconds [

21]. This duration was deliberately chosen to be longer than the room’s reverberation time to avoid any adverse effects on the measurement accuracy. To ensure reliability, each measurement was repeated four times.

The timing reference for the measurements was maintained using the feedback connection of the sound card, ensuring precise synchronization. The loudspeaker system was strategically positioned at a height of approximately 1.5 meters. The microphone, essential for capturing the audio response, was placed at a distance of 0.5 meters from the loudspeaker. This setup was designed to optimize the accuracy and reliability of the measurements, thereby facilitating a comprehensive analysis of the loudspeaker’s impulse response.

3. Results and Discussion

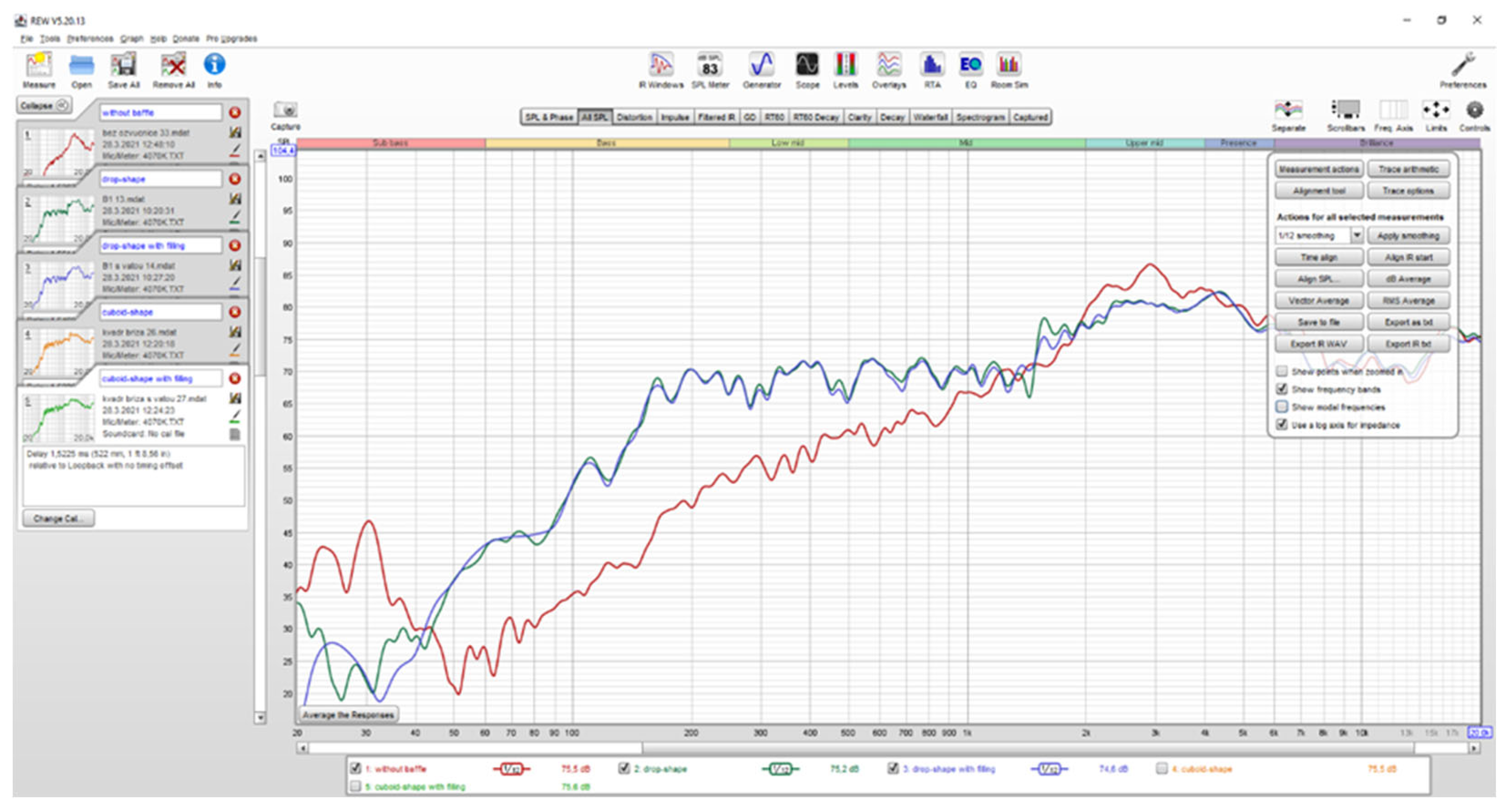

The output of the measurement of the acoustic parameters are graphs showing the frequency and impedance characteristics of the loudspeaker inserted in different types of enclosures. The areas of all graphs are determined by the frequency range of 20-20,000 Hz. The sound pressure level is in the range of 30-100 dB and the impedance is between -20 and 120 Ω. For greater clarity, the curves are smoothed by a value of 1/12.

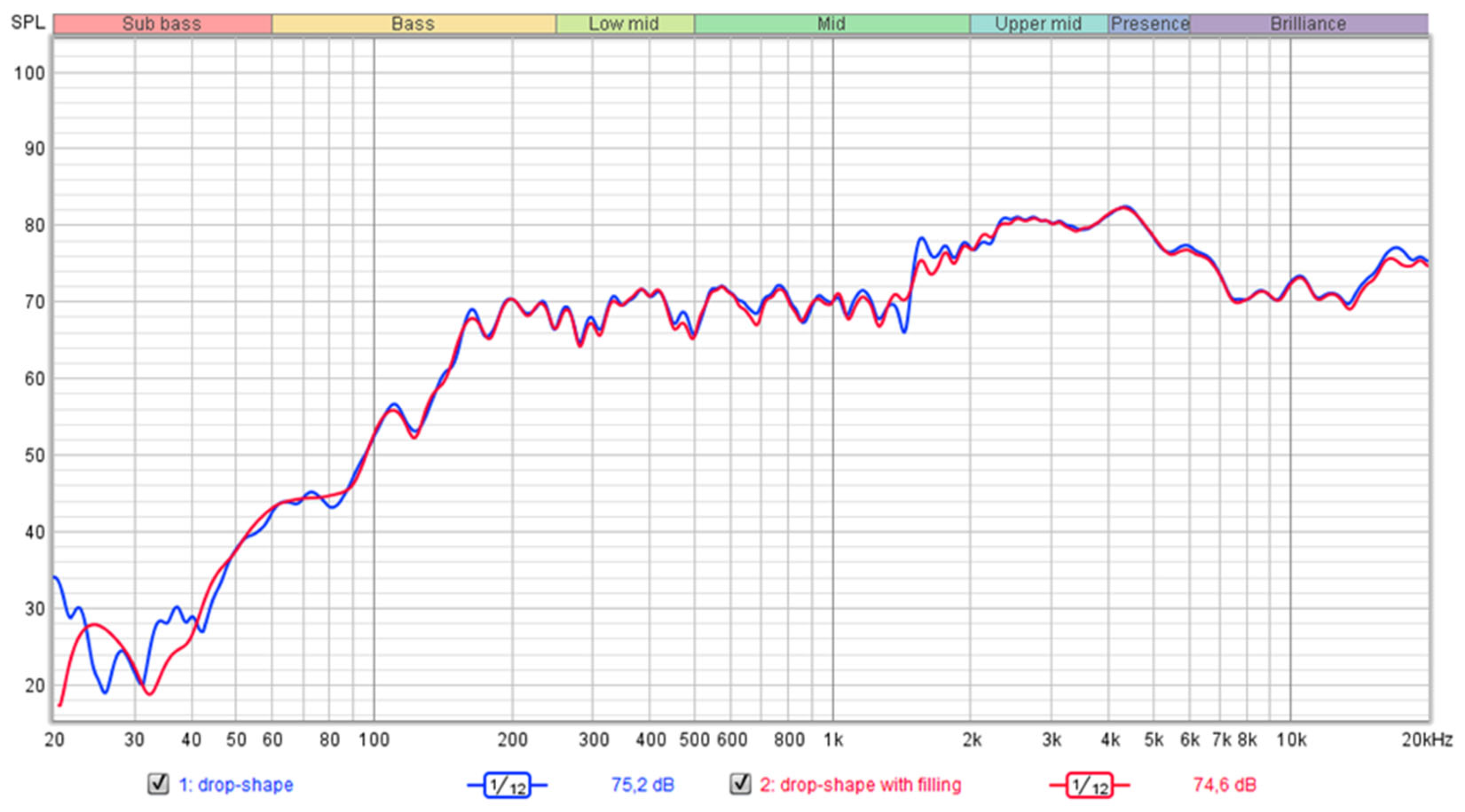

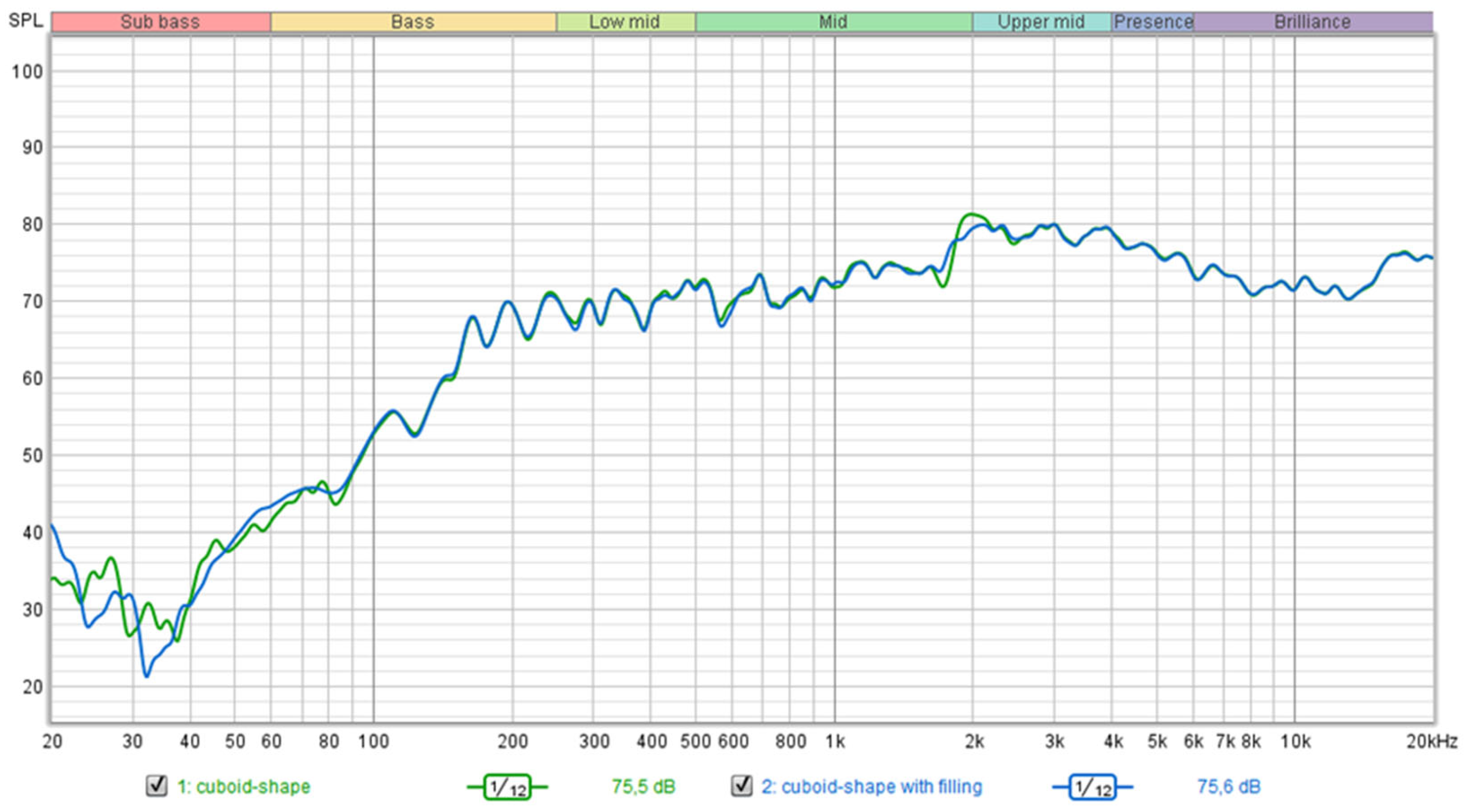

Given the absence of significant sound differences between various types of wood in prior research, our study primarily focuses on comparing different baffle shapes and the impact of acoustic filling, as illustrated in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. First, we evaluated the differences between teardrop-shaped baffles made of birch wood, comparing those without damping material to those with damping material. [

22]

Figure 6 showing the results for the birch shell shows the change in the course of the frequency curve in certain areas. These are mainly deviations around the frequency of 1500 Hz in mid frequency, where the influence of the damping material is noticeable, thanks to which the frequency curve has a smoother course [

23,

24]. The deflections are probably caused by standing waves in space. Thanks to the damping cotton, this resonance is reduced by about 2 dB. There are no significant differences in the curve except for the greater deflection of the undamped cover.

The frequency curve shown at the bottom shows the ripple caused by the resonance of the enclosure in addition to the main deflection caused by the speaker. It is located at the same frequency as the frequency response. It is largely eliminated by the damping material and is therefore particularly noticeable in the curve showing the undamped case. Differences in the main deflection of the compared prototypes may be due to measurement errors.

Figure 7 shows the frequency and impedance characteristics of the birch box enclosure. The frequency characteristic curve undulating in the frequency range around 1700 Hz in mid frequency, where the influence of the speaker became apparent. In this case too, it is a resonance of the return wave in the enclosure. In this case, the unwanted vibration of the enclosure is also caused by the diffraction effect, which occurs on the front edge inside the box shape enclosure. After adding damping material, the deflections are suppressed and reduced by 2 to 4 dB.

Furthermore, there is a slight protrusion of the undamped cabinet curve around the 1700 Hz region. This is the same cause as the frequency deviation in the same part of the graph. Even here, the peak could be eliminated by using damp material.

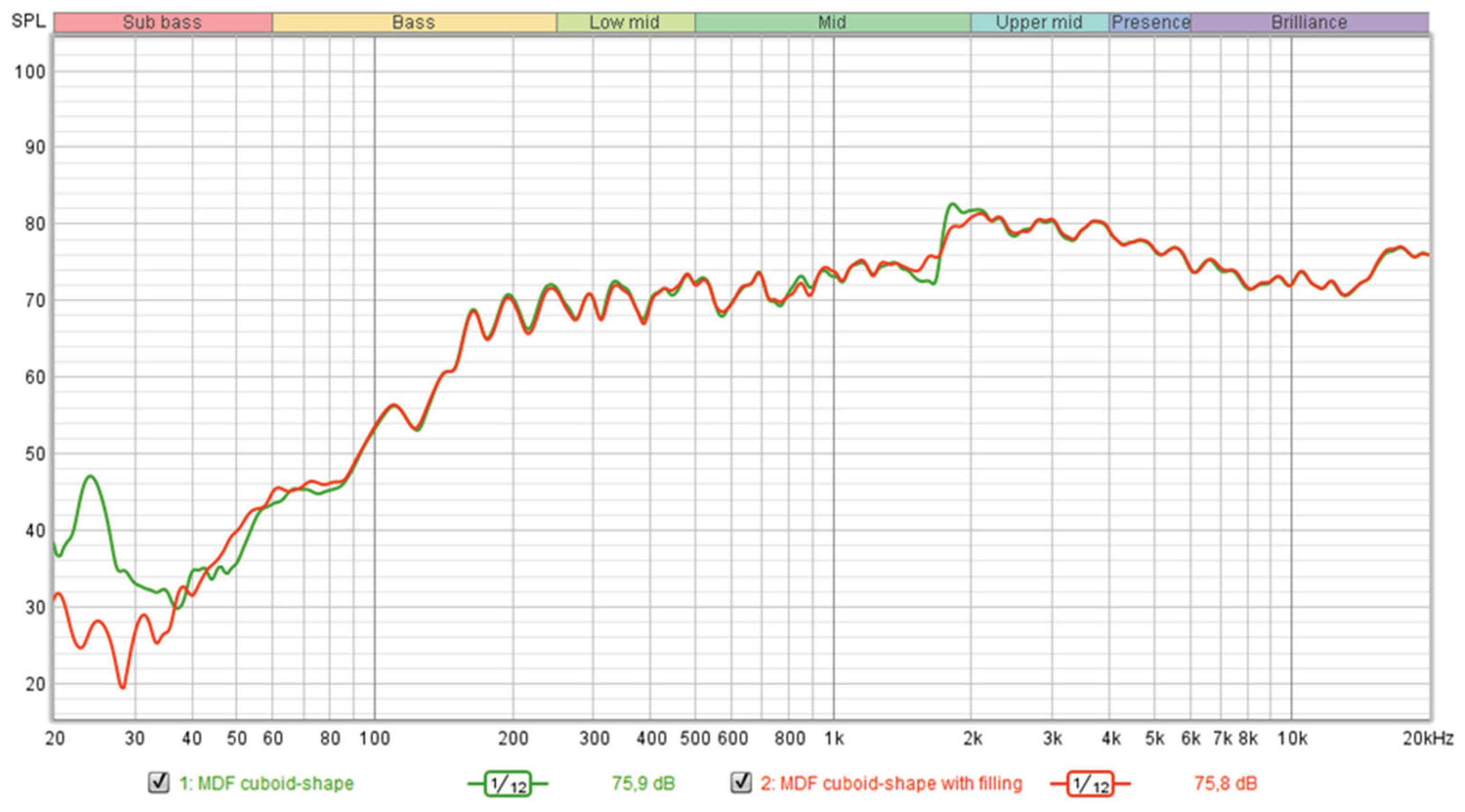

Figure 8 shows the frequency characteristics of a block cabinet made of medium density fiberboard. The MDF baffle was made for the possibility of comparison with a representative of the frequently used baffle material [

25]. If we compare

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, we can state that the differences between the individual curves are very negligible. This fact gives us the possibility of using preparatory woods and increasing their added value. In addition, the acoustic properties (especially of birch and poplar) are comparable to, for example, maple, which is used to make musical instruments [

12,

26].

Each of the enclosures has its pros and cons. in the case of a teardrop-shaped enclosure, standing waves occur inside the space and the frequency characteristic is thus adversely affected [

27]. On the other hand, with a box structure, there is, as can be expected, a diffraction effect caused by the sharp edges inside the enclosure [

28,

29]. We tried to eliminate this phenomenon, and that’s why we created a drop-shaped design in which there are no sharp edges [

30]. However, it can be seen from the graphs that despite the diffraction effect of the box-shaped enclosure, it has a smoother frequency response than the drop-shaped enclosure. However, the differences are not significant [

3,

31]. By using the inner filling, these differences were even more erased. It can therefore be said that the damping material has a positive effect on the frequency response if the enclosure shows any imperfections, which are also reported in their publications Newell and Holland [

3], Eargle [

32], Walker [

33] and Bauer [

34]. However, it must be added that this solution is not entirely ideal, and it would be better to focus further research on the development of a new, better design of the enclosure, which will offer not only an innovative appearance, but also an ideal course of the frequency curve, even without the need to install internal filling. For further research, for example, a box design with rounded inner edges and a sufficiently rigid structure to prevent unwanted vibrations of the enclosure walls may appear to be ideal [

35,

36]. It would also be advisable to use a bass-reflex on the back of the speaker [

37,

38].

4. Conclusions

When evaluating the frequency characteristics of the loudspeakers, clear differences were observed between the cube-shaped and the teardrop-shaped enclosures. Specifically, the cube-shaped housing demonstrated a more consistent and balanced frequency response compared to the teardrop design. These results highlight the critical impact of cabinet geometry, both external and internal, on sound propagation. However, it is important to note that while these differences are measurable, the extent of their impact may vary depending on specific design parameters and environmental conditions. In conclusion, it is necessary to add that the damping material in the form of glass wool smoothed the frequency curve even better and the differences between the individual shapes of the baffles were thus eliminated to the maximum.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.H. and V.B.; methodology, P.H. and V.B.; software, P.H.; validation, V.B.; formal analysis, P.H.; investigation, P.H. and V.B.; resources, P.H.; data curation, V.B.; writing—original draft preparation, P.H.; writing—review and editing, V.B.; visualization, P.H.; supervision, V.B.; project administration, V.B.; funding acquisition, P.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Internal Grant Agency of the Faculty of Forestry and Wood of the Czech University of Life Sciences, Prague, Czech Republic, IGA A_01_24.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript. More detailed datasets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Czech University of Life Sciences, Prague, Czech Republic, for providing the equipment and space to carry out our research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AVE |

Average |

| CNC |

Computer numerical control |

| MDF |

Medium density fiberboard |

| REW |

Room EQ Wizard |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| SPL |

Sound pressure level |

References

- Cherradi, Y.; Rosca, I.C.; Cerbu, C.; Kebir, H.; Guendouz, A.; Benyoucef, M. Acoustic properties for composite materials based on alfa and wood fibers. Applied Acoustics 2021, 174, 107759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čulík, M. Drevo a jeho využitie vo výrobe hudobných nástrojov. vedecká štúdia (Wood and its use in the production of musical instruments), a scientific study; Technical University in Zvolen: Zvolen, 2013; ISBN 978-80-228-2511-5. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, P.; Holland, K. Loudspeakers for music recording and reproduction; Routledge, 2018; ISBN 9781315149202. [Google Scholar]

- Kol, H.S.; Keskin, H.; Korkut, S.; Akbulut, T. Laminated veneer lumber from Rowan (Sorbus aucuparia Lipsky). African journal of agricultural research 2009, 4, 1101–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Warmbier, K.; Wilczyński, A.; Danecki, L. Properties of one-layer experimental particleboards from willow (Salix viminalis) and industrial wood particles. In Eur. J. Wood Prod. 2013, 71, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balatinecz, J.; Mertens, P.; Boever, L.D.; Yukun, H.; Jin JuWan, J.J.; Acker, J.V. Properties, processing and utilization. In Poplars and willows: trees for society and the environment; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2014; pp. 527–561. [Google Scholar]

- Van Acker, J.; Defoirdt, N.; Van den Bulcke, J. Enhanced potential of poplar and willow for engineered wood products. In Proceedings of the 2nd Conference on Engineered Wood Products based on Poplar/willow Wood; 2016; pp. 187–210. [Google Scholar]

- Borůvka, V.; Dudík, R.; Zeidler, A.; Holeček, T. Influence of Site Conditions and Quality of Birch Wood on Its Properties and Utilization after Heat Treatment. Part I—Elastic and Strength Properties, Relationship to Water and Dimensional Stability. Forests 2019, 10, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Bao, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Bao, Y.; Yu, W. Influence of density on properties of compressed weeping willow (Salix babylonica) wood panels. Forest Products Journal 2017, 67, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudík, R.; Borůvka, V.; Zeidler, A.; Holeček, T.; Riedl, M. Influence of Site Conditions and Quality of Birch Wood on Its Properties and Utilization after Heat Treatment. Part II—Surface Properties and Marketing Evaluation of the Effect of the Treatment on Final Usage of Such Wood. Forests 2020, 11, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, H.; Verkasalo, E.; Claessens, H. Potential of Birch (Betula pendula Roth and B. pubescens Ehrh.) for Forestry and Forest-Based Industry Sector within the Changing Climatic and Socio-Economic Context of Western Europe. Forests 2020, 11, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horák, P.; Borůvka, V.; Novák, D.; Kozel, J. Acoustic Parameters of Birch Wood Compared to Maple Wood and Medium Density Fibreboard. In Unleashing The Potential of Wood-based Materials; University of Zagreb: Croatia, 7 December 2023; pp. 75–82. ISBN 978-953-292-083-3. [Google Scholar]

- Požgaj, A.; Chovanec, D.; Kurjatko, S.; Babiak, M. Štruktúra a Vlastnosti Dreva (Structure and Properties of Wood); Príroda: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1993; p. 485. ISBN 80-07-00600-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bucur, V. Acoustics of Wood; Springer: Germany, 2006; p. 394. ISBN 978-3-540-30594-1. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, H.F. Direct radiator loudspeaker enclosures. Journal of the Audio Engineering Society 1969, 17, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, M.J. Handbook of acoustics; John Wiley & Sons: River Street, Hoboken, 1998; ISBN 978-0-471-25293-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielsson, A.; Lindström, B.; Till, O. Loudspeaker frequency response and perceived sound quality. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 1991, 90, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossing, T. (Ed.) Springer handbook of acoustics; Springer Science & Business Media. LLC: New York, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-387-30446-5. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, N. ACOUSTIC CHARACTERIZATION OF ROOMS USING DIRECTIONAL AND OMNIDIRECTIONAL SOURCES. Ph.D. dissertation, Brigham Young University-Idaho, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Farina, A. Advancements in impulse response measurements by sine sweeps. Audio engineering society convention 2007, 122. Audio Engineering Society. [Google Scholar]

- Toft, R. Digital Audio: Sampling, Dither, and Bit Depth. Technical Matters. 2024, p. 11. Available online: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/popmusicforum_techmatters/11.

- Kozel, J. Analysis of the acoustic parameters of wood-based speaker enclosures. diploma thesis, Department of Wood processing and Biomaterials, Faculty of Forestry and Wood Sciences, Czech University of Life Sciences, Prague, Czechia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, J.; Shen, Y.; Feng, X. Comments on” A Diffractive Study on the Relation Between Finite Baffle and Loudspeaker Measurement”. Journal of the Audio Engineering Society 2021, 69, 294–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’appolito, J. Testing Loudspeakers: Which Measurements Matter, Part 1. Audioxpress, 2016, [Online] 10. 11. [Cited: 23. 5. 2024.]. Available online: https://audioxpress.com/article/testing-loudspeakers-which-measurements-matter-part-1.

- Cobianchi, M.; Rousseau, M. Modelling the Sound Radiation by Loudspeaker Cabinets; Comsol Conference: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Horák, P.; Borůvka, V. Acoustic Parameters of Pioneer Wood Species. In 11TH HARDWOOD CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS; University of Sopron: Hungary, 2024; pp. 219–223. ISBN 978-963-334-518-4. [Google Scholar]

- Červenka, M.; Šoltés, M.; Bednařík, M. Optimal shaping of acoustic resonators for the generation of high-amplitude standing waves. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2014, 136, 1003–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirsch, C.; Ewert, S.D. Effects of measured and simulated diffraction from a plate on sound source localization. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2024, 155.5, 3118–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J. R. Fundamentals of diffraction. Journal of the Audio Engineering Society 1997, 45, 347–356. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell, J.A.; Hixson, E.L. Constant-Beamwidth One-Octave Bandwidth End-Fire Line Array of Loudspeakers; Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology: Pasadena, CA, 1995; Paper; Available online: https://aes2.org/publications/elibrary-page/?id=7936.

- Dobrucki, A. Diffraction correction of frequency response for loudspeaker in rectangular baffle. Archives of Acoustics 2006, 31, 537–542. [Google Scholar]

- Eargle, J. Loudspeaker handbook; Springer Science & Business Media: Boston, US, 2003; ISBN 978-1-4419-5390-2. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, P.J. The loudspeaker in the home. Journal of the British Institution of Radio Engineers 1953, 13, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, B.B. Acoustic damping for loudspeakers; Transactions of the IRE Professional Group on Audio; University of Minnesota: US, 1953; Volume 3, pp. 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, J. Computation of diffraction for loudspeaker enclosures. Journal of the Audio Engineering Society 1989, 37, 353–362. [Google Scholar]

- Klippel, W.; Schlechter, J. Distributed mechanical parameters of loudspeakers, part 1: Measurements. Journal of the Audio Engineering Society 2009. Available online: https://aes2.org/publications/elibrary-page/?id=14830.

- Bezzola, A.; Kubota, G.S.; Devantier, A. Acoustic Mass and Resistance as Function of Drive Level for Straight, Bent, and Flared Loudspeaker Ports. Audio Engineering Society Convention 2020, 149. Audio Engineering Society. [Google Scholar]

- Ahonen, J.; Karjalainen, M.; Rauhala, J.; Tikander, M. Perception and physical behavior of loudspeaker nonlinearities at bass frequencies in closed vs. reflex enclosures. Audio Engineering Society Convention 2008, 124. Audio Engineering Society. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).