Introduction

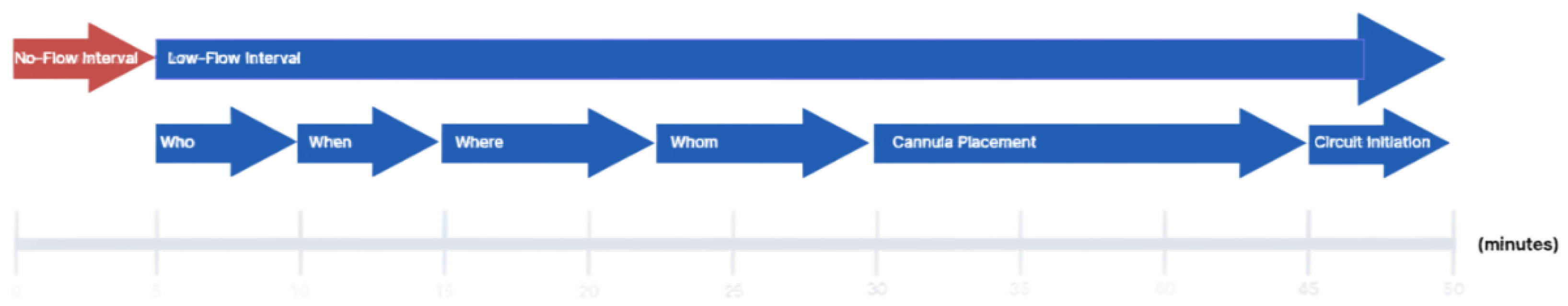

In-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) continues to carry a high mortality rate despite widespread use of advanced cardiac life support (ACLS). Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR) has emerged as a promising intervention for select patients in refractory cardiac arrest. While growing evidence supports its use in improving survival; particularly in high-volume centers with structured protocols—the technical and operational processes involved in ECPR initiation remain variably reported in the literature. Moreover, comprehensive reviews systematically evaluating the evidence guiding each step of ECPR implementation are limited. In this review, we examine the current literature on ECPR performance metrics through a stepwise analysis of the VA-ECMO initiation process, utilizing the framework proposed by the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO –

Figure 1). Our goal is to identify evidence-based best practices, committee consensus, and to highlight components of the process that require further investigation and standardization in the context of IHCA.

Method

We performed a narrative literature review focused on the technical and practical aspects of ECPR implementation for in-hospital cardiac arrest. Studies were identified through a broad search with PubMed utilizing terms such as “ECPR,” “extracorporeal CPR,” “VA-ECMO,” “in-hospital cardiac arrest,” “cannulation,” and “ECMO implementation” spanning 2015–2024. The evidence was organized using a stepwise framework adapted from the ELSO Red Book, including patient selection (Who), timing (When), cannulation environment (Where), team composition (Whom), cannula placement, and circuit initiation. We included studies that discussed logistical considerations, procedural steps, or performance benchmarks in ECPR delivery. While we primarily focus on system assessment of ECPR in IHCA, we included studies of ECPR in the context of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) and non-arrest VA-ECMO implementation to form a comprehensive synthesis where data and guidelines on IHCA were lacking; pediatric populations were excluded. The aim was to synthesize performance metrics that reflect real-world practice variation and identify opportunities for evidence-based standardization.

Who

The use of extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR) in refractory cardiac arrest is supported by evidence [

1,

2]. However, it continues to be a very complex and resource intensive process with lot of variability in execution around the world. Many centers have their own protocols and guidelines. Candidate selection continues to be one of the most vital decisions in this endeavor. There is significant variability in eligibility criteria for ECPR candidacy across all the reviewed articles. Lenient or liberal criteria comes with a risk of lower proportion of patients having favorable outcome from ECPR and simultaneously strict criteria though increases the favorable outcome proportion comes with risk of a smaller number of potential survivors getting ECPR [

3,

4].

Contraindications for ECPR are suggested when ECPR will not successfully bridge to recovery or alternative destination therapy like mechanical circulatory assist device or despite cardiovascular recovery there will be no meaningful neurological recovery. Candidates are also ruled out for practical reasons like technical limitations like high BMI and if ECMO doesn’t align with patient’s wishes [

5].

Multiple factors considered in candidate selection can be enumerated as follows-

Age

Age limit continues to be one of the factors with highest variability in the protocol. Age range limit range from 50-80 years most common being 75 years, 70 and 65 years [

3]. Age limit of 75 years is most common among all the protocols. Consensus being higher the age, poorer the outcomes. the age, poorer the outcomes.

Witnessed vs Non Witnessed Cardiac Arrest

This is the next common criteria to determine the candidacy for ECPR. According to the review by done by Alenazi et al. almost 68 percent of the systems had witnessed cardiac arrest as one of the criteria to determine the candidacy for ECPR [

3].

Initial Rhythm

Shockable rhythm (VT/VF) is considered as a strong predicter of improved outcomes. Shockable rhythm usually is indicative of shorter no flow time as compared to non-shockable rhythm (PEA or asystole). As per Alenazi et al. 30 percent of systems included initial rhythm as criteria to determine candidacy for ECPR. Pozzi et al. changed their institutional protocol to only include shockable rhythm for ECPR and their neurological outcome improved from 4.4% to 23.5% [

6].

Presence of Comorbidities

Goal of ECPR is to bridge the patient with cardiac arrest to recovery, heart transplant or to long term mechanical circulatory devices like LVAD. Patients who have chronic end stage organ dysfunction or malignancy are usually not considered the candidates for ECPR. Bourcier et al. eliminated patients >80 years old, with preexisting multiorgan dysfunction, ventilator dependency >1 month, bedridden >1 month or not independent, intracranial hemorrhage or infarct, uncontrollable bleeding, terminal stage malignancy [

7]. Other prognostic factors to be considered before candidacy are lactate levels (>5mmol/L symbolizes poor prognosis), dilated pupils are also considered as poor prognosis. Brain Near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) is another potential way to assess prognosis for ECPR [

8].An analysis of ELSO registry showed 2.3-fold increase in mortality after ECPR in patients with BMI >40.0 kg/m2. In addition to all indications mentioned “potential organ donation” has also been considered as indication to proceed with ECPR.

When

No flow time- Time from cardiac arrest to start of chest compression is considered as no flow time. No flow time cut offs vary from zero to 20 mins and less than 5min being the most frequently being used [

3].

Low flow time- Low flow time can be defined as time from initiation of chest compressions to start of ECMO flow. In recent consensus ECPR is recommended for patients in whom ROSC is not achieved within 10-15 mins and had no contraindication to ECPR [

9]. Low flow time cut off varies from 15 mins to 150 mins- 60 mins being the most common cutoff [

3]. It is important to consider that to initiate the ECMO flow within that time, ECPR candidacy should be discussed within 10-15 mins of ECPR [

10]. As per Wengenmayer et al. survival rates were 67% in patients (

n = 14) with a CPR duration shorter than 20 minutes and 29% (

n = 33), 10% (

n = 43), and 6% (

n = 43) after 20–45, 45–60, and 60–135 minutes of mechanical CPR, respectively. Sim et al. performed a retrospective study which compared low flow time <20 min, 20-40 min and >40 min and neurological outcomes were significantly better with lower low flow time at 3 months and 6 months [

11].

Where

Patients can be cannulated at the bedside or in interventional catheterization lab. For an outside hospital arrest scoop and ride or stay and play approaches are suggested [

12]. According to the multicenter prospective study in north America- stay and play strategy has no added benefit beyond CPR time beyond 15-20 mins [

13]. Continuing good quality CPR during transport, reduces the risk caused by interruption of CPR. Cohort study of 2515 patients from ELSO registry showed overall mortality was 67.6% and was higher for cardiac arrest in ICU and acute care hospital bed. Also, it showed that moving the patient to different location for ECPR cannulation did not give any additional benefits [

14].

Team Composition and Coordination (By Whom)

ECPR demands the rapid orchestration of a highly trained multidisciplinary team. Most programs include a cardiac surgeon or interventional cardiologist, intensivist or anesthesiologist, perfusionist, ECMO-trained registered nurse, and increasingly a clinical pharmacist. Several institutions report improved outcomes with the inclusion of full-time intensivist and ECMO pharmacists within the team structure, ensuring around-the-clock expertise and coordinated decision-making.

Team structure and responsibilities ultimately depend on institutional protocols and system design. Coordination requires a highly trained team to run parallel tasks of managing ongoing cardiopulmonary resuscitation while simultaneously coordinating ECPR implementation logistics.

Cannula Placement

Cannula Site Selection

Current guidelines from major societies emphasize the femoral vessels as the recommended site for VA-ECMO cannulation in the setting of ECPR. This preference is based on the importance of rapid access, feasibility of percutaneous cannulation, and the ability to initiate support outside of procedural suites [

15,

16]. This approach is particularly advantageous in emergent settings where minimizing low-flow interval is critical. Bilateral cannulation is preferred due to associated lower risk of compartment syndrome, bleeding, and in-hospital morality [

17].

Alterative cannulation sites include axillary and subclavian arteries. Upper arterial access offers theoretical advantages, including reduced risk of differential hypoxemia and facilitating patient mobilization. However, these approaches are associated with increased procedural complexity, higher bleeding risk, potential hyperperfusion of the ipsilateral upper extremity, and a greater incidence of vascular complications [

18,

19]. Ultimately, cannulation site selection should be individualized accounting for patient anatomy (e.g., morbid obesity, severe iliofemoral disease, or prior vascular surgery), clinical context, and the expertise of the cannulating team [

16,

20,

21]. Importantly, there are no randomized controlled trials directly comparing cannulation site strategies, with most recommendations based on observational data and expert consensus.

From a quality improvement perspective, performance metrics related to site selection are inherently limited, given the patient-specific nature of these decisions. However, we propose tracking the frequency and distribution of cannulation sites across ECPR cases as a useful system-level metric. Monitoring this distribution may help identify trends, operator preferences, deviations from protocol, and facilitate retrospective analysis to inform future research and guideline development regarding optimal cannulation site selection.

Cannula Size Selection

Effective ECPR relies heavily on appropriate cannula selection to optimize circuit flow and minimize complications. Current adult practice typically involves the use of venous drainage cannula ranging from 21 to 29 French (Fr) and arterial return cannula between 15 and 19 Fr [

15]. The decision regarding cannula size should be individualized based on patient specific factors including vessel caliber, body surface area (BSA), and relatedly the anticipated flow requirements necessary to maintain adequate end-organ perfusion.

A recurring pattern observed in the literature is that smaller cannulas are more frequently employed in bedside ECPR settings, while larger cannulas are more commonly used in environments such as the catheterization laboratory or operating room [

22,

23]. This variation likely reflects the increased comfort of proceduralists with image guided techniques, which facilitate the placement of larger cannulas with greater precision. Despite the higher flow potential offered by larger cannulas, existing evidence suggests that comparable clinical outcomes may be achieved using smaller cannulas, with the added benefit of a reduced complication profile. This includes lower rates of distal limb ischemia, bleeding, vascular trauma, and infection [

22]. Concerns of increased risk of hemolysis as a complication of smaller catheter sizes is not supported by the literature [

24,

25]. Although further research is warranted to determine the optimal cannula size relative to physiologic and anatomic variables, current data support a strategy of selecting the smallest cannulas capable of achieving sufficient flows, thereby balancing the goals of perfusion adequacy and complication minimization.

From a systems-based standpoint, incorporating performance metrics related to cannula size into ECPR quality improvement efforts may enhance program readiness and response efficiency. While time-based performance metrics specific to cannula sizing are limited, readiness metrics can be readily implemented. We propose routine daily audits to verify the availability of a full range of sterile arterial and venous cannula sizes, ensuring preparedness for the unpredictable and time sensitive nature of ECPR deployment. Furthermore, although cannula sizing is often nuanced and subject to provider judgment, we propose the adoption of standardized protocols that encourage the use of the smallest cannula size capable of delivering target flows. Specifically, cannula selection should aim to support a cardiac index of 2.2 to 2.4 L/min/m

2, guided by calculated or estimated BSA [

15]. While precise determination of vessel caliber and anatomic suitability may be limited in emergent situations, this approach may remote consistency in clinical practice while supporting both timely cannulation and the reduction of complications. Additional avenues for performance tracking may include retrospective audits correlating cannula size to achieved flow rates based on BSA and complication incidents. Over time, such data could refine institutional best practices and help facilitate benchmarking across ECPR centers.

Cannula Insertion

While surgical cutdown is associated with lower rates of vascular complications, percutaneous cannulation is generally favored in the ECPR setting due to its association with shorter flow initiation [

26,

27]. Given that the low-flow interval Is among the few modifiable predictors of survival and neurologic outcome, prioritizing techniques that expedite cannulation is critical to optimizing patient outcomes [

28].

Percutaneous access can be performed using either surface anatomical landmarks or image guidance. Landmark-based techniques have been associated with increased rates of cannula malposition and prolonged cannulation times when compared to image-guided approaches. In contrast, ultrasound guidance has consistently demonstrated improved first-pass success rates, reduced mechanical complications, and shorter time to cannulation [

21,

29,

30,

31]. Fluoroscopy offers the advantage of real time confirmation of guidewire and cannula position, particularly in patients with complex or atypical anatomy. However, it has not shown a consistent time advantage over ultrasound guidance [

32]. Moreover, the need to transport a patient undergoing active conventional CPR to a fluoroscopy capable procedure suite can introduce delays and compromise the quality of chest compressions during transit, negating theoretical benefit in procedural accuracy [

33].

In the context of ECPR program development and quality improvement, we propose cannulation techniques should be assessed through a dual lens of readiness and time-based performance. Readiness metrics should include daily verification of functional ultrasound machines, consistent availability of sterile probe covers and vascular access kits, and established protocols to ensure that all necessary equipment is immediately accessible wherever cannulation is anticipated. Time performance metrics may include the measurement of skin to wire and skin to cannula intervals, which provide granular insights into procedural efficiency. Monitoring these metrics over time enables identification of workflow bottlenecks and guides targeted interventions such as simulation-based training, staffing model optimization, and equipment standardization.

Cannula Position Confirmation

Accurate and timely placement of the venous drainage and arterial return cannulas is essential for ensuring effective flow and minimizing complications [

15,

34,

35]. In the context of peripheral femoro-femoral ECPR, the venous cannula should ideally be advanced into the inferior vena cava at the junction of the right atrium to optimize preload reduction in circuit drainage. The arterial cannula tip should be positioned within the iliac or distal abdominal aorta and oriented cephalad to ensure effective retrograde aortic perfusion.

Two primary imaging modalities are employed to confirm proper cannula positioning: transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and fluoroscopy. Fluoroscopy is commonly utilized in catheterization laboratories to guide both guidewire and cannula advancement, offering real time confirmation of vascular trajectory and positioning. By contrast, in emergency or ICU based ECPR scenarios where fluoroscopy is often unavailable and rapid cannulation is essential, TEE provides a practical and effective alternative. Indeed, TEE offers high-quality, real-time visualization of cannula placement without interrupting ongoing chest compressions or delaying circuit initiation [

36,

37,

38,

39].

The literature supports the use of both TEE and fluoroscopy, with TEE offering utility for visualizing venous cannula position, confirming right heart decompression, and excluding complications such as intracardiac thrombus or cannula mal-position [

15,

34]. With respect to arterial cannula confirmation, while TEE is limited with respect to direct visualization of the peripheral arterial return cannula tip, it can be utilized to both confirm guidewire passage into the descending aorta and exclude wire malposition in the cardiac chambers [

15,

40]. Although no randomized controlled trials definitively favor one modality over the other, expert consensus emphasizes the importance of employing some form of real-time imaging to confirm cannula location as a standard practice. Transesophageal echocardiography has been highlighted in multiple feasibility studies and consensus statements for its ability to be rapidly deployed, maintain image quality during active compressions, and minimize hands-off time [

20,

38,

41]. Accordingly, major guidelines recommend TEE as the preferred modality for cannula confirmation when available with transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) or fluoroscopy considered acceptable alternatives. At minimum, bedside ultrasound guidance is considered a foundational standard for placement.

From a quality improvement perspective, we propose tracking imaging utilization rate defined as the proportion of ECPR cases in which TEE, TTE, or fluoroscopy is employed to confirm cannula positioning intuitively serves as a valuable performance metric. Routine tracking of this measure can help ensure imaging protocols are consistently followed, and that training gaps or equipment deficiencies are rapidly identified. Furthermore, we propose skin-to-cannula-position confirmation time as a time performant metric to monitor team responsiveness and procedural efficiency across varied clinical environments.

Adding opportunities for system optimization may include implementing standardized imaging protocols within ECPR checklists, conducting regular multidisciplinary simulations focused on cannula placement and confirmation, or integrating post case debriefs that explicitly review imaging timelines and findings. These efforts may help promote consistency across operators to ensure imaging is both timely and accurate in addition to supporting institutional learning.

Cannula Placement Associated Complications

Complications related to ECMO cannulation during ECPR represent a significant source of morbidity and mortality. While these complications may arise from each distinct phase, namely cannula assize selection, insertion, and positioning, they frequently overlap. The Extracorporeal Life Support Organization provides a standardized framework for classifying ECMO related complications as either medical or mechanical, which has been widely adopted in both clinical practice and research reporting.

Medical complications related to ECMO cannula placement are the most prevalent and include infection, bleeding, vascular injury (e.g., dissection, perforation, pseudoaneurysm), limb ischemia, compartment syndrome, and rarely cardiac tamponade. Among these complications, bleeding and limb ischemia are especially common in the context of ECPR. Bleeding rates associated with cannulation may range from 15-46%, while limb ischemia occurs up to 20%, and infection rates as high as 11%, and cardiac tamponade at ~2-3% [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. Access site selection also impacts complication risk, with higher bleeding rates reported in axillary and subclavian approaches compared to femoral access [

18,

19].

Mechanical complications related to cannula placement include cannula dislodgement, kinking, inadequate sizing, migration, and malposition. Improper cannula positioning can result in inadequate venous drainage, insufficient arterial flow, or increased circuit pressures, all of which compromise support [

15,

16,

42].

Many of these complications are reducible through adherence to evidence-based practices. Indeed, expert consensus emphasizes standardization and protocolization of all phases of cannula placement [

15,

16]. This includes bilateral femoro-femoral site selection, utilizing the smallest cannula capable of achieving adequate flow, employing image guided percutaneous cannulation, and confirming position with transesophageal echocardiography or fluoroscopy. Consistent application of these strategies, supported by structured team training and performance review, can reduce procedural risk.

To ensure ongoing improvement, routine surveillance of complications is essential. Participation in structured quality reporting platforms, such as the Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation (GWTG-R) for IHCA and the ELSO Quality Reporting Platform for ECMO-related complications, enables institutions to benchmark outcomes, receive feedback, and guide targeted quality improvement efforts [

49,

50]. The ELSO registry, the largest international ECMO database, provides a standardized framework for tracking ECPR-related complications. Transparent reporting not only supports institutional learning but also contributes to broader efforts aimed at improving ECPR safety and efficacy across centers.

Circuit Initiation

Initiating extracorporeal circulation during ECPR is a time-sensitive and precise process that marks the transition from vascular access to active hemodynamic support. Once appropriate cannula placement is confirmed, the next step involves connecting the patient to the ECMO circuit to reestablish systemic circulation. This process comprises 3 essential steps: verifying correct inflow and outflow line orientation to avoid reversal, performing a sterile wet to wet connection to maintain circuit integrity and minimize air entrainment, and initiating and confirming adequate circuit flow to restore circulation [

2,

51].

Currently, there are few metrics to help guide measurement and continuous improvement of this process. However, if each of these steps is unstandardized or delayed, they can theoretically introduce avoidable inefficiencies that prolong low-flow interval [

52]. As such, optimization of circuit initiation represents an important systems level target for both training and continuous performance monitoring.

In alignment with prior sections, we once again propose a dual categorization of tracking metrics for circuit initiation. With respect to system readiness metrics, we propose routine daily audits to verify a pre-primed ECMO circuit is dedicated to ECPR, development of and adherence to a standardized protocol for confirming inflow and outflow line identification and connection, and development and adherence to a wet-to-wet connection protocol. Each of these elements should be subject to structured documentation and ongoing audit to ensure that ECPR teams remain equipped and aligned in the event of ECPR system activation.

Time-performance metrics may include the interval from confirmed cannula placement to wet-to-wet circuit connection, and from cannula position to achieve full flow verification. This data can be tracked alongside clinical outcomes to identify bottlenecks, assess team performance, and guide simulation training or protocol revisions. The incorporation of standardized checklists and cognitive aids to promote reliability during circuit initiation.

Complications related to circuit initiation include but are not limited to air embolism, connection errors, raceway or circuit rupture, heat exchanger malfunction, oxygenator failure, and pump malfunction [

52,

53,

54]. Consistent reporting of these events to the ELSO Quality Reporting Platform supports institutional learning and contributes to global benchmarking efforts aimed at improving safety and reliability in ECPR.

Table 1.

Summary of proposed performance metrics for ECPR implementation in the setting of in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA), organized by process step. Quality metrics reflect patient-level characteristics that influence candidacy and outcomes, including age, rhythm, comorbidities, and estimated low-flow interval. Readiness metrics evaluate system preparedness, such as point-of-care availability, team designation, and equipment readiness. Time-performant metrics quantify key procedural intervals, including cannula placement and circuit initiation benchmarks. Together, these metrics provide a structured framework for continuous quality improvement and standardized performance evaluation in ECPR programs.

Table 1.

Summary of proposed performance metrics for ECPR implementation in the setting of in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA), organized by process step. Quality metrics reflect patient-level characteristics that influence candidacy and outcomes, including age, rhythm, comorbidities, and estimated low-flow interval. Readiness metrics evaluate system preparedness, such as point-of-care availability, team designation, and equipment readiness. Time-performant metrics quantify key procedural intervals, including cannula placement and circuit initiation benchmarks. Together, these metrics provide a structured framework for continuous quality improvement and standardized performance evaluation in ECPR programs.

| Process Step |

Quality Metrics |

| Who |

Age

Cardiac Arrest

Rhythm

Comorbidities

Lactate

BMI

Estimated no-flow interval

Low-flow interval |

< 75 years

Witnessed

Shockable

Absence of end stage or terminal disease

< 5

< 40 kg/m2

< 5 minutes

< 60 minutes |

| When |

Discuss candidacy |

10 mins |

| Where |

Point of Care |

Yes |

| Whom |

Designated Institutional Team |

Yes |

| |

Readiness Metrics |

Time Performant Metrics |

Cannula Placement

Site Selection

Size Selection

Insertion

Position Confirmation

|

Site Assessment by Ultrasound

Cannulas Readily Available

Insertion by Ultrasound Guidance

TEE or Fluoroscopy Available |

Skin-to-wire time, Skin-to-cannula time

Time to Position Confirmation |

| Circuit Initiation |

ECMO Pre-Primed Circuit

Wet-to-wet Protocol |

Wet-to-Wet Connection Time

Time to Targeted Flow |

References

- Kim, H.; Cho, Y. H. Role of extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation in adults. Acute Crit Care 2020, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Charrière, A.; Assouline, B.; Scheen, M.; Mentha, N.; Banfi, C.; Bendjelid, K.; Giraud, R. ECMO in Cardiac Arrest: A Narrative Review of the Literature. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenazi, A.; Aljanoubi, M.; Yeung, J.; Madan, J.; Johnson, S.; Couper, K. Variability in patient selection criteria across extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR) systems: A systematic review. Resuscitation 2024, 204, 110403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diehl, A.; Read, A. C.; Southwood, T.; Buscher, H.; Dennis, M.; Nanjayya, V. B.; Burrell, A. J. C. The effect of restrictive versus liberal selection criteria on survival in ECPR: a retrospective analysis of a multi-regional dataset. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2023, 31, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, J.; Alves, B. R.; Padrao, E. M. H.; Fountain, J.; Jensen, C.; Henderson, J. C.; Fan, E.; Michel, E.; Medlej, K.; Crowley, J. C. Candidacy Decision Making for Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (ECPR): Lessons from a Single-Center Retrospective Analysis. Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia. [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, M.; Grinberg, D.; Armoiry, X.; Flagiello, M.; Hayek, A.; Ferraris, A.; Koffel, C.; Fellahi, J. L.; Jacquet-Lagrèze, M.; Obadia, J. F. Impact of a Modified Institutional Protocol on Outcomes After Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation for Refractory Out-Of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2022, 36, 1670–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourcier, S.; Desnos, C.; Clément, M.; Hékimian, G.; Bréchot, N.; Taccone, F. S.; Belliato, M.; Pappalardo, F.; Broman, L. M.; Malfertheiner, M. V. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation for refractory in-hospital cardiac arrest: A retrospective cohort study. International Journal of Cardiology 2022, 350, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, N.; Nishiyama, K.; Callaway, C. W.; Orita, T.; Hayashida, K.; Arimoto, H.; Abe, M.; Endo, T.; Murai, A.; Ishikura, K.; et al. Noninvasive regional cerebral oxygen saturation for neurological prognostication of patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a prospective multicenter observational study. Resuscitation 2014, 85, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A. S. C.; Tonna, J. E.; Nanjayya, V.; Nixon, P.; Abrams, D. C.; Raman, L.; Bernard, S.; Finney, S. J.; Grunau, B.; Youngquist, S. T.; et al. Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Adults. Interim Guideline Consensus Statement From the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization. Asaio j 2021, 67, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wengenmayer, T.; Rombach, S.; Ramshorn, F.; Biever, P.; Bode, C.; Duerschmied, D.; Staudacher, D. L. Influence of low-flow time on survival after extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (eCPR). Crit Care 2017, 21, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J. H.; Kim, S. M.; Kim, H. R.; Kang, P. J.; Kim, H. J.; Lee, D.; Lee, S. W.; Choi, I. C. Time to initiation of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation affects the patient survival prognosis. J Intern Med 2024, 296, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wengenmayer, T.; Tigges, E.; Staudacher, D. L. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation in 2023. Intensive Care Med Exp 2023, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunau, B.; Kime, N.; Leroux, B.; Rea, T.; Van Belle, G.; Menegazzi, J. J.; Kudenchuk, P. J.; Vaillancourt, C.; Morrison, L. J.; Elmer, J.; et al. Association of Intra-arrest Transport vs Continued On-Scene Resuscitation With Survival to Hospital Discharge Among Patients With Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Jama 2020, 324, 1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzeffi, M.; Zaaqoq, A.; Curley, J.; Buchner, J.; Wu, I.; Beller, J.; Teman, N.; Glance, L. Survival after extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation based on in-hospital cardiac arrest and cannulation location: An analysis of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry. Critical Care Medicine 2024, 52, 1906–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorusso, R.; Whitman, G.; Milojevic, M.; Raffa, G.; McMullan, D. M.; Boeken, U.; Haft, J.; Bermudez, C. A.; Shah, A. S.; D’Alessandro, D. A. 2020 EACTS/ELSO/STS/AATS expert consensus on post-cardiotomy extracorporeal life support in adult patients. ASAIO J 2020, 67, 12–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt, A. M.; Copeland, H.; Deswal, A.; Gluck, J.; Givertz, M. M.; 1, T. F.; 2, T. F.; 3, T. F.; 4, T. F. The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation/Heart Failure Society of America Guideline on Acute Mechanical Circulatory Support. J Card Fail 2023, 29, 304–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panchal, A. R.; Berg, K. M.; Hirsch, K. G.; Kudenchuk, P. J.; Del Rios, M.; Cabañas, J. G.; Link, M. S.; Kurz, M. C.; Chan, P. S.; Morley, P. T.; et al. 2019 American Heart Association Focused Update on Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support: Use of Advanced Airways, Vasopressors, and Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation During Cardiac Arrest: An Update to the American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2019, 140, e881–e894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moussa, M. D.; Rousse, N.; Abou Arab, O.; Lamer, A.; Gantois, G.; Soquet, J.; Liu, V.; Mugnier, A.; Duburcq, T.; Petitgand, V.; et al. Subclavian versus femoral arterial cannulations during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: A propensity-matched comparison. J Heart Lung Transplant 2022, 41, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawda, R.; Marszalski, M.; Piwoda, M.; Molsa, M.; Pietka, M.; Filipiak, K.; Miechowicz, I.; Czarnik, T. Infraclavicular, Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Approach to the Axillary Artery for Arterial Catheter Placement: A Randomized Trial. Crit Care Med 2024, 52, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitzberger, F. F.; Haas, N. L.; Coute, R. A.; Bartos, J.; Hackmann, A.; Haft, J. W.; Hsu, C. H.; Hutin, A.; Lamhaut, L.; Marinaro, J.; et al. ECPR: Expert Consensus on PeRcutaneous Cannulation for Extracorporeal CardioPulmonary Resuscitation. Resuscitation 2022, 179, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegas, A.; Wells, B.; Braum, P.; Denault, A.; Miller Hance, W. C.; Kaufman, C.; Patel, M. B.; Salvatori, M. Guidelines for Performing Ultrasound-Guided Vascular Cannulation: Recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2025, 38, 57–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Cho, Y. H.; Sung, K.; Park, T. K.; Lee, G. Y.; Lee, J. M.; Song, Y. B.; Hahn, J. Y.; Choi, J. H.; Choi, S. H.; et al. Impact of Cannula Size on Clinical Outcomes in Peripheral Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. ASAIO J 2019, 65, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, H.; Landes, E.; Truby, L.; Fujita, K.; Kirtane, A. J.; Mongero, L.; Yuzefpolskaya, M.; Colombo, P. C.; Jorde, U. P.; Kurlansky, P. A.; et al. Feasibility of smaller arterial cannulas in venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015, 149, 1428–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, P. R.; Hodgson, C. L.; Bellomo, R.; Gregory, S. D.; Raman, J.; Stephens, A. F.; Taylor, K.; Paul, E.; Wickramarachchi, A.; Burrell, A. Smaller Return Cannula in Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Does Not Increase Hemolysis: A Single-Center, Cohort Study. ASAIO J 2023, 69, 1004–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, A. F.; Wickramarachchi, A.; Burrell, A. J. C.; Bellomo, R.; Raman, J.; Gregory, S. D. Hemodynamics of small arterial return cannulae for venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Artif Organs 2022, 46, 1068–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saiydoun, G.; Gall, E.; Boukantar, M.; Fiore, A.; Mongardon, N.; Masi, P.; Bagate, F.; Radu, C.; Bergoend, E.; Mangiameli, A.; et al. Percutaneous angio-guided versus surgical veno-arterial ECLS implantation in patients with cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2022, 170, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, F.; Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Du, Z.; Rycus, P.; Tonna, J. E.; Alexander, P.; Lorusso, R.; Fan, E.; et al. Percutaneous versus surgical cannulation for femoro-femoral VA-ECMO in patients with cardiogenic shock: Results from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry. J Heart Lung Transplant 2022, 41, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, C.; Hao, X.; Rycus, P.; Tonna, J. E.; Alexander, P.; Fan, E.; Wang, H.; Yang, F.; Hou, X. Percutaneous cannulation is associated with lower rate of severe neurological complication in femoro-femoral ECPR: results from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry. Ann Intensive Care 2023, 13, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatsutsumi, K.; Endo, A.; Costantini, T. W.; Takayama, W.; Morishita, K.; Otomo, Y.; Inoue, A.; Hifumi, T.; Sakamoto, T.; Kuroda, Y.; et al. Time-saving effect of real-time ultrasound-guided cannulation for extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A multicenter retrospective cohort study. Resuscitation 2023, 191, 109927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voicu, S.; Henry, P.; Malissin, I.; Dillinger, J. G.; Koumoulidis, A.; Magkoutis, N.; Yannopoulos, D.; Logeart, D.; Manzo-Silberman, S.; Péron, N.; et al. Improving cannulation time for extracorporeal life support in refractory cardiac arrest of presumed cardiac cause - Comparison of two percutaneous cannulation techniques in the catheterization laboratory in a center without on-site cardiovascular surgery. Resuscitation 2018, 122, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitov, A.; Frankel, H. L.; Blaivas, M.; Kirkpatrick, A. W.; Su, E.; Evans, D.; Summerfield, D. T.; Slonim, A.; Breitkreutz, R.; Price, S.; et al. Guidelines for the Appropriate Use of Bedside General and Cardiac Ultrasonography in the Evaluation of Critically Ill Patients-Part II: Cardiac Ultrasonography. Crit Care Med 2016, 44, 1206–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, S.; Tachibana, S.; Toyohara, T.; Sonoda, H.; Yamakage, M. Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A retrospective study comparing the outcomes of fluoroscopy. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H. J.; Lee, J. W.; Joo, K. H.; You, Y. H.; Ryu, S.; Kim, S. W. Point-of-Care Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Cannulation of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: Make it Simple. J Emerg Med 2018, 54, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoara, A.; Skubas, N.; Ad, N.; Finley, A.; Hahn, R. T.; Mahmood, F.; Mankad, S.; Nyman, C. B.; Pagani, F.; Porter, T. R.; et al. Guidelines for the Use of Transesophageal Echocardiography to Assist with Surgical Decision-Making in the Operating Room: A Surgery-Based Approach: From the American Society of Echocardiography in Collaboration with the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2020, 33, 692–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussey, P. T.; von Mering, G.; Nanda, N. C.; Ahmed, M. I.; Addis, D. R. Echocardiography for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Echocardiography 2022, 39, 339–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teran, F.; Prats, M. I.; Nelson, B. P.; Kessler, R.; Blaivas, M.; Peberdy, M. A.; Shillcutt, S. K.; Arntfield, R. T.; Bahner, D. Focused Transesophageal Echocardiography During Cardiac Arrest Resuscitation: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020, 76, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmiston, T.; Sangalli, F.; Soliman-Aboumarie, H.; Bertini, P.; Conway, H.; Rubino, A. Transoesophageal echocardiography in cardiac arrest: From the emergency department to the intensive care unit. Resuscitation 2024, 203, 110372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krammel, M.; Hamp, T.; Hafner, C.; Magnet, I.; Poppe, M.; Marhofer, P. Feasibility of resuscitative transesophageal echocardiography at out-of-hospital emergency scenes of cardiac arrest. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 20085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fair, J.; Mallin, M. P.; Adler, A.; Ockerse, P.; Steenblik, J.; Tonna, J.; Youngquist, S. T. Transesophageal Echocardiography During Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Is Associated With Shorter Compression Pauses Compared With Transthoracic Echocardiography. Ann Emerg Med 2019, 73, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estep, J. D.; Nicoara, A.; Cavalcante, J.; Chang, S. M.; Cole, S. P.; Cowger, J.; Daneshmand, M. A.; Hoit, B. D.; Kapur, N. K.; Kruse, E.; et al. Recommendations for Multimodality Imaging of Patients With Left Ventricular Assist Devices and Temporary Mechanical Support: Updated Recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2024, 37, 820–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fair, J.; Tonna, J.; Ockerse, P.; Galovic, B.; Youngquist, S.; McKellar, S. H.; Mallin, M. Emergency physician-performed transesophageal echocardiography for extracorporeal life support vascular cannula placement. Am J Emerg Med 2016, 34, 1637–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodie, D.; Slutsky, A. S.; Combes, A. Extracorporeal Life Support for Adults With Respiratory Failure and Related Indications: A Review. JAMA 2019, 322, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, D.; Yang, I. X.; Ling, R. R.; Syn, N.; Poon, W. H.; Murughan, K.; Tan, C. S.; Choong, A. M. T. L.; MacLaren, G.; Ramanathan, K. Vascular Complications of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis. Crit Care Med 2020, 48, e1269–e1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, A. Y.; Khanh, L. N.; Joung, H. S.; Guerra, A.; Karim, A. S.; McGregor, R.; Pawale, A.; Pham, D. T.; Ho, K. J. Limb ischemia and bleeding in patients requiring venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Vasc Surg 2021, 73, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalia, A. A.; Lu, S. Y.; Villavicencio, M.; D’Alessandro, D.; Shelton, K.; Cudemus, G.; Essandoh, M.; Ortoleva, J. Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation: Outcomes and Complications at a Quaternary Referral Center. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2020, 34, 1191–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Hachamovitch, R.; Kittleson, M.; Patel, J.; Arabia, F.; Moriguchi, J.; Esmailian, F.; Azarbal, B. Complications of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for treatment of cardiogenic shock and cardiac arrest: a meta-analysis of 1,866 adult patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2014, 97, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonna, J. E.; Boonstra, P. S.; MacLaren, G.; Paden, M.; Brodie, D.; Anders, M.; Hoskote, A.; Ramanathan, K.; Hyslop, R.; Fanning, J. J.; et al. Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry International Report 2022: 100,000 Survivors. ASAIO J 2024, 70, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basílio, C.; Anders, M.; Rycus, P.; Paiva, J. A.; Roncon-Albuquerque, R. Cardiac Tamponade Complicating Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: An Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry Analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2024, 38, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, K. M.; Cheng, A.; Panchal, A. R.; Topjian, A. A.; Aziz, K.; Bhanji, F.; Bigham, B. L.; Hirsch, K. G.; Hoover, A. V.; Kurz, M. C.; et al. Part 7: Systems of Care: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2020, 142, S580–S604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rali, A. S.; Abbasi, A.; Alexander, P. M. A.; Anders, M. M.; Arachchillage, D. J.; Barbaro, R. P.; Fox, A. D.; Friedman, M. L.; Malfertheiner, M. V.; Ramanathan, K.; et al. Adult Highlights From the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry: 2017-2022. ASAIO J 2024, 70, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C. S.; Wieruszewski, E. D.; Nei, S. D.; Vollmer, N. J.; Mattson, A. E.; Wieruszewski, P. M. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A primer for pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2023, 80, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrams, D.; MacLaren, G.; Lorusso, R.; Price, S.; Yannopoulos, D.; Vercaemst, L.; Bělohlávek, J.; Taccone, F. S.; Aissaoui, N.; Shekar, K.; et al. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation in adults: evidence and implications. Intensive Care Med 2022, 48, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamis-Holland, J. E.; Menon, V.; Johnson, N. J.; Kern, K. B.; Lemor, A.; Mason, P. J.; Rodgers, M.; Serrao, G. W.; Yannopoulos, D.; Cardiology, I. C. C. C. a. t. A. C. C. a. G. C. C. o. t. C. o. C.; et al. Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory Management of the Comatose Adult Patient With an Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024, 149, e274–e295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K. M.; Wan, W. T. P.; Ling, L.; So, J. M. C.; Wong, C. H. L.; Tam, S. B. S. Management of Circuit Air in Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Single Center Experience. ASAIO J 2022, 68, e39–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).