Submitted:

28 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

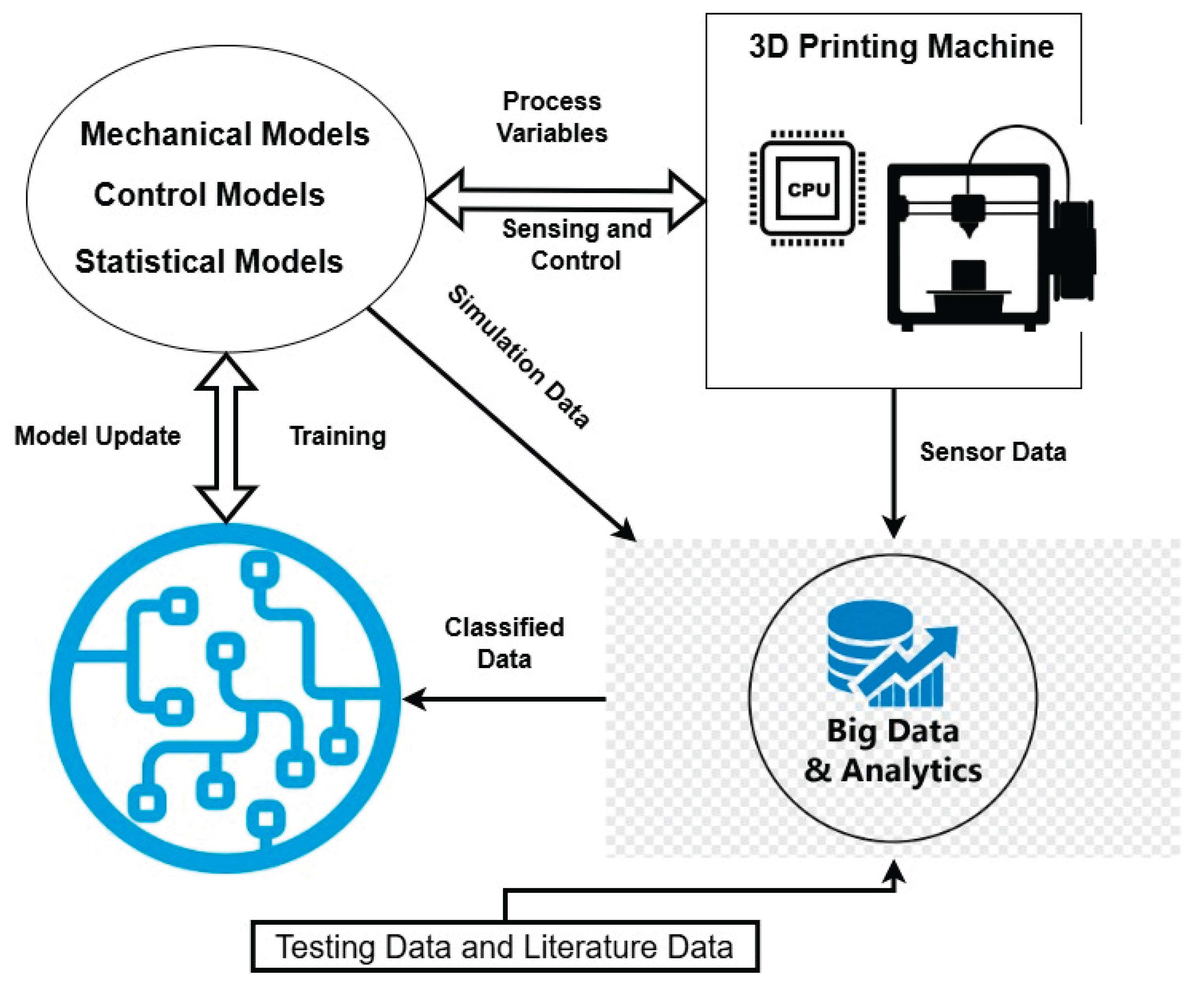

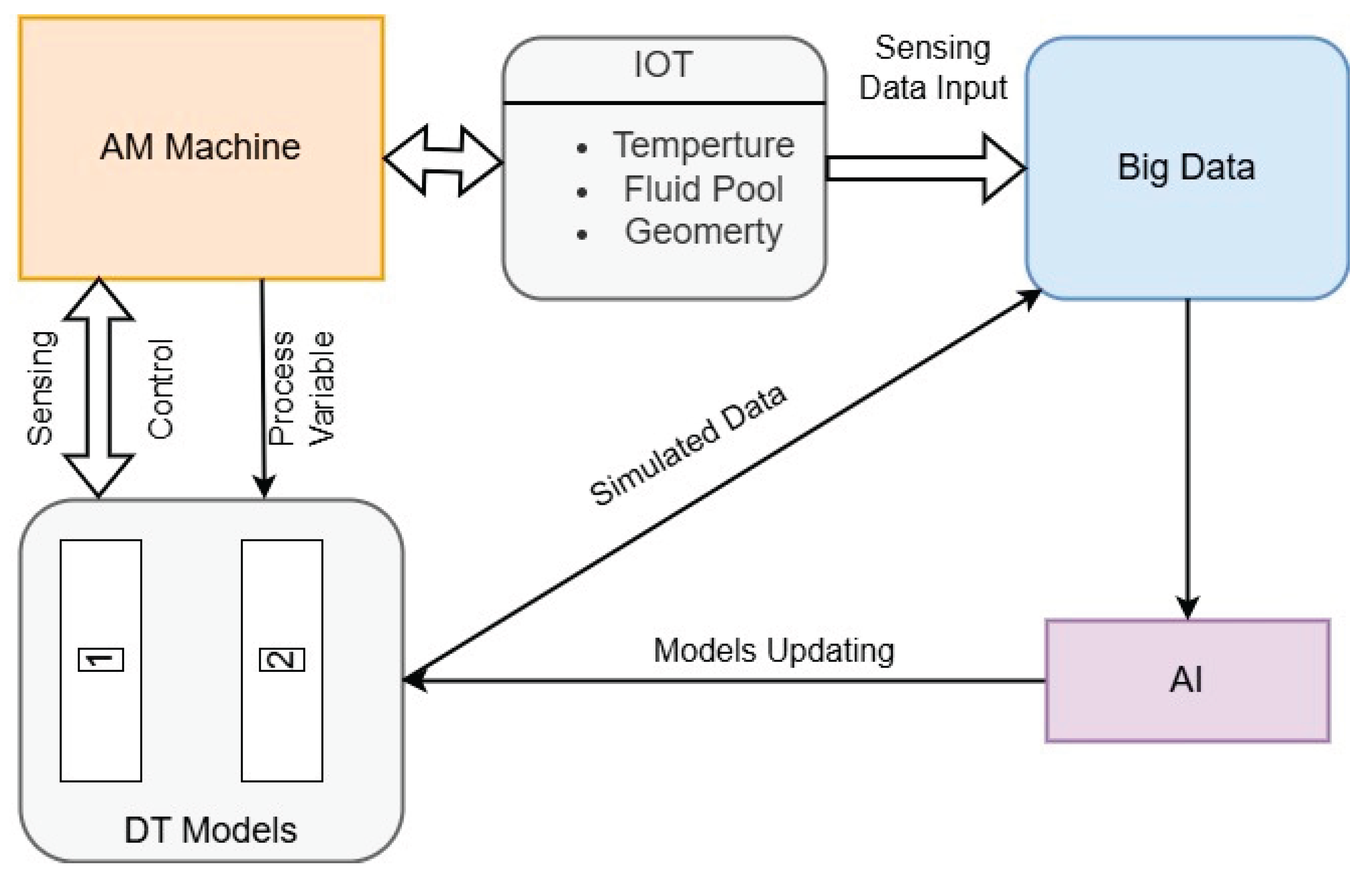

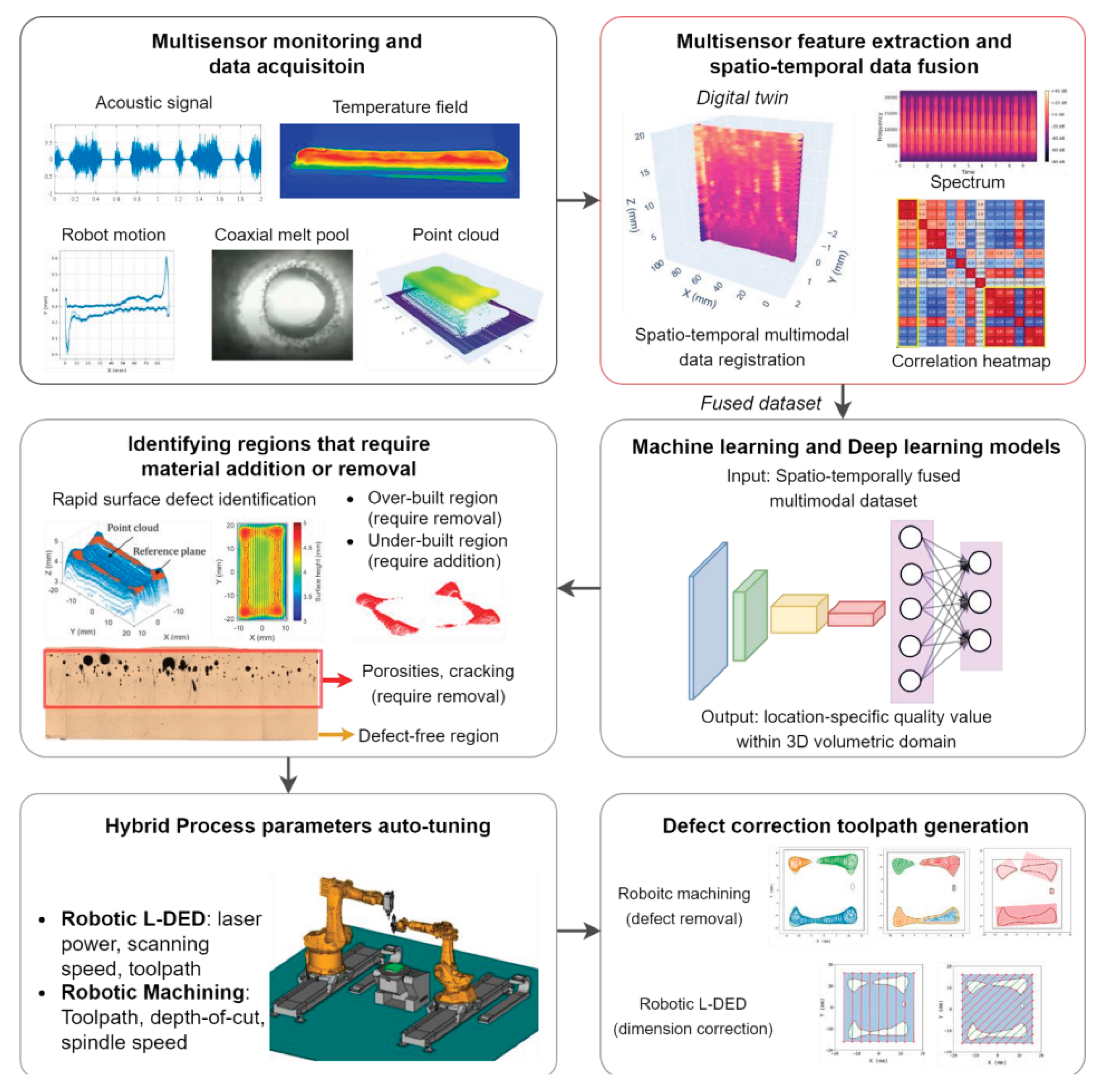

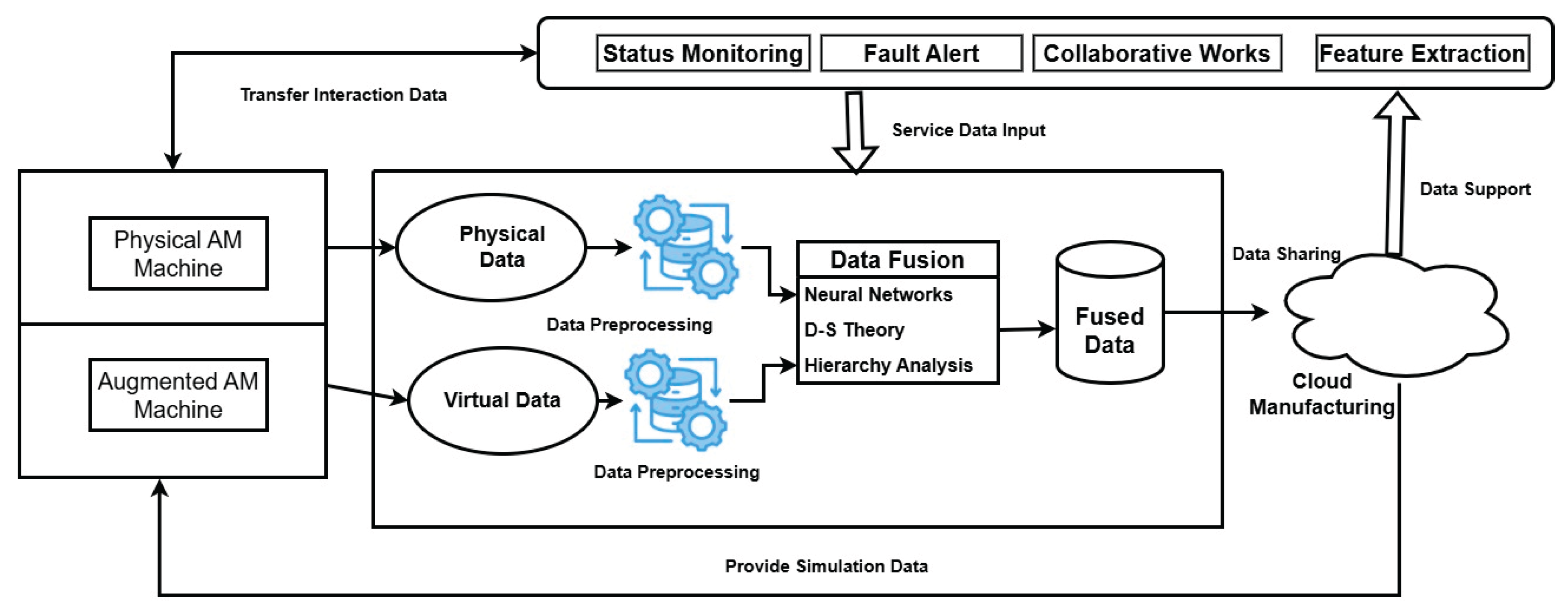

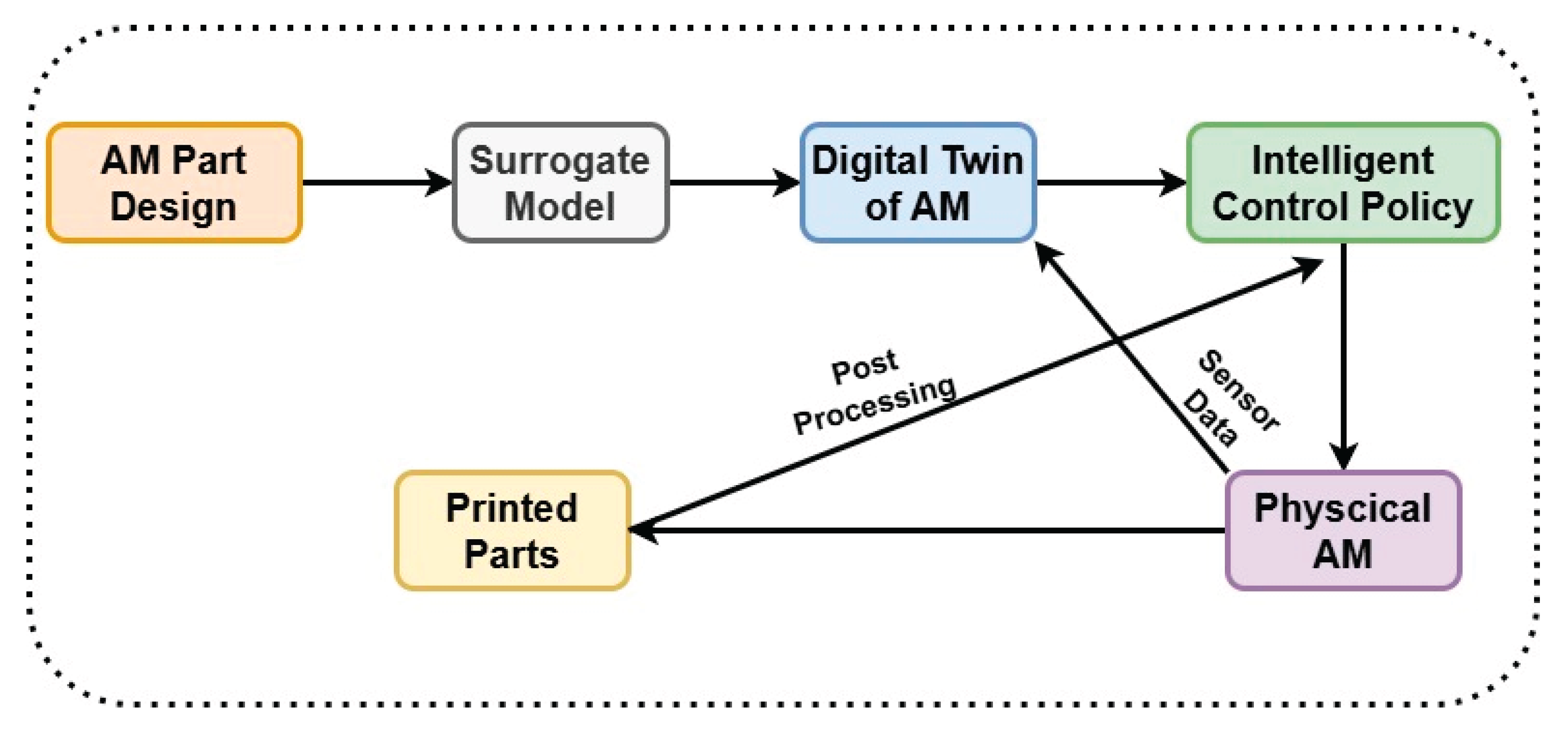

2. Digital Twin Technology in Additive Manufacturing

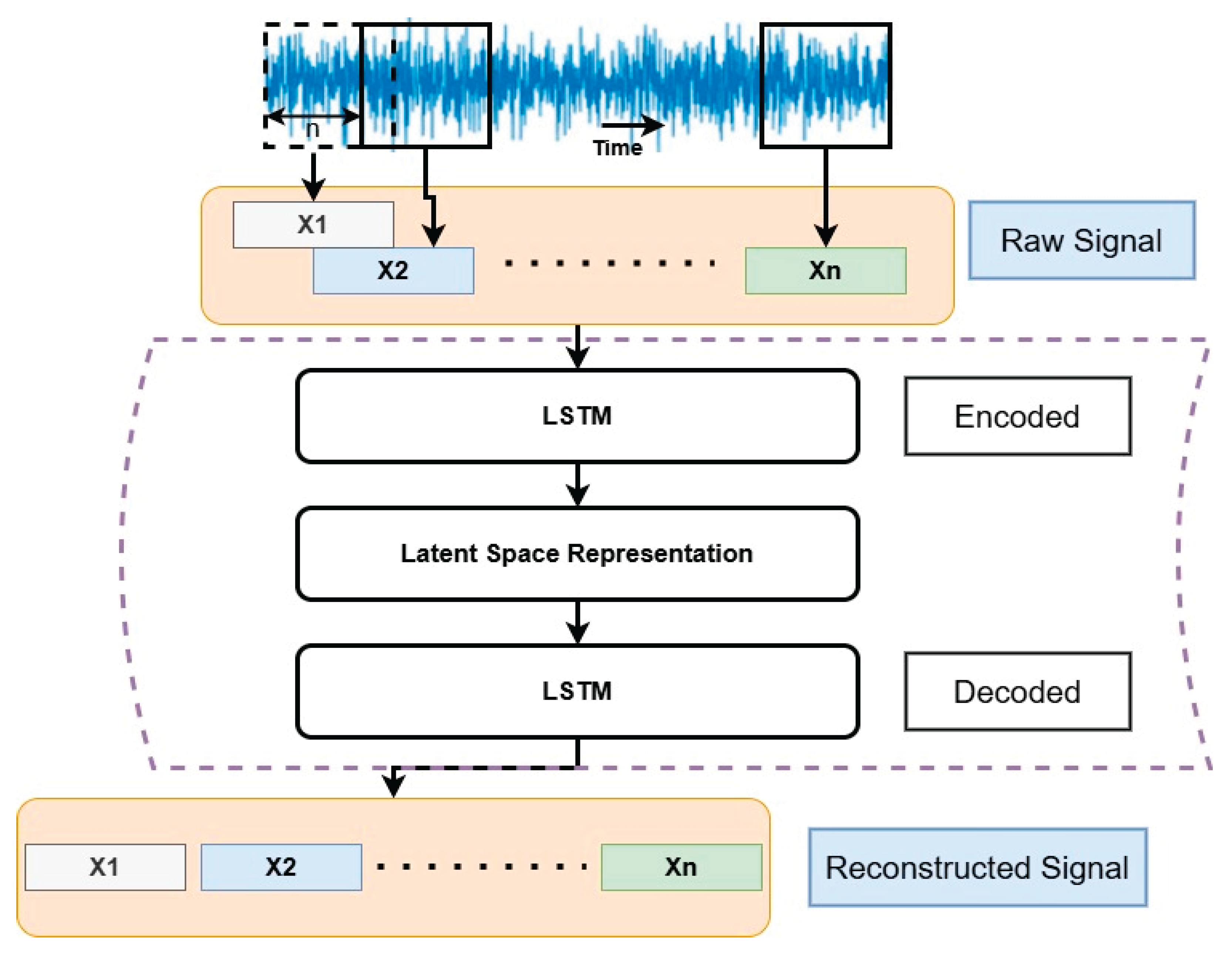

3. Modular AI for System Reconfiguration and Optimization (AI/ML Algorithms)

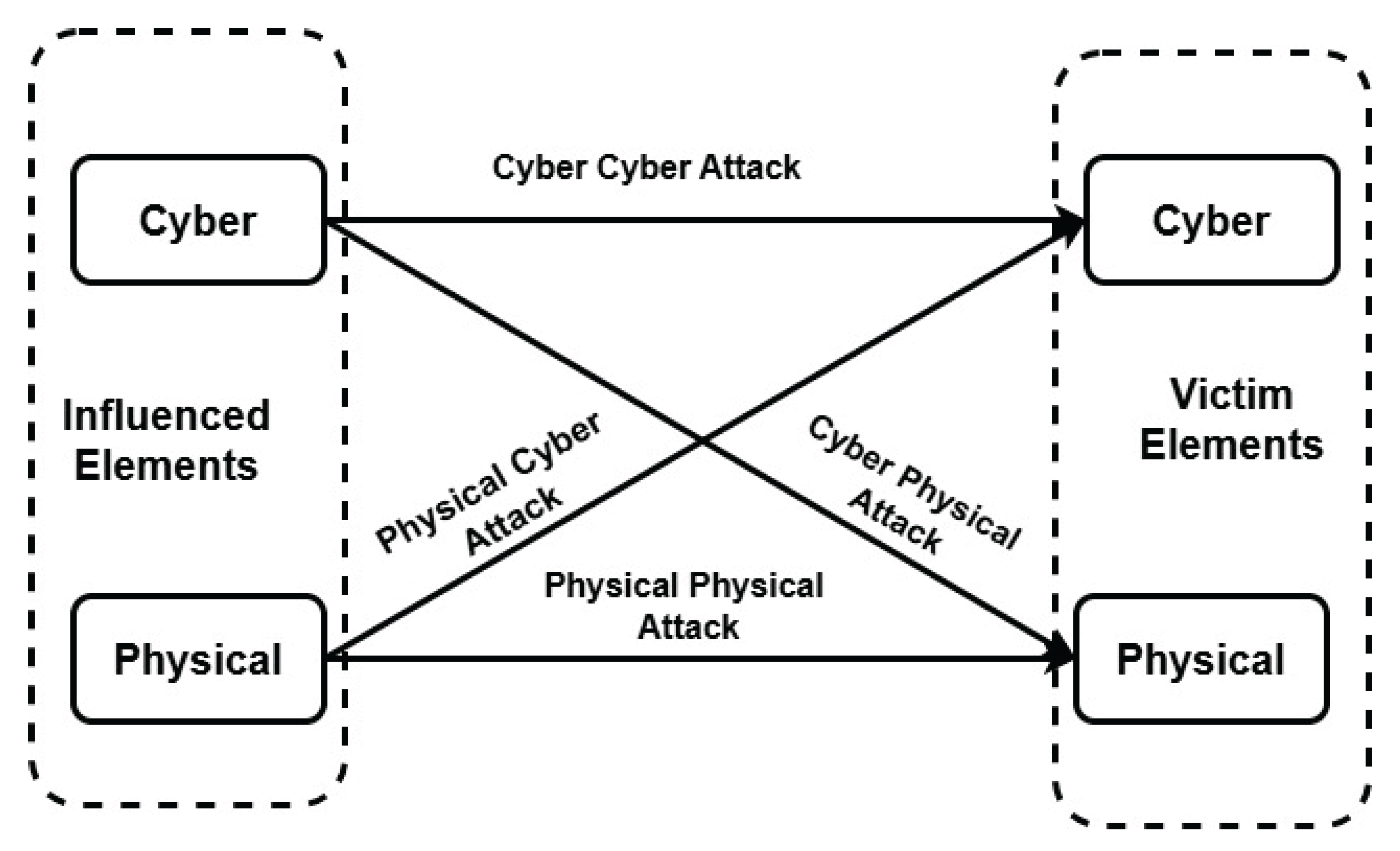

4. Cyber Security in Additive Manufacturing

- STL or G-code file of the object produced in a lab environment.

- The audio signal was recorded during manufacturing.

- The audio fingerprint was calculated, encrypted, and appended to the G-code file.

5. Challenges and Possible Solutions

5.1. Cybersecurity Vulnerabilities

5.2. Possible Solutions

- Shi et al. (2023) proposed using side-channel data—such as acoustic signals and vibrations—in combination with AI-based anomaly detection to increase the accuracy of attack detection and hence support real-time monitoring operations.

- Blockchain technology is recommended for inclusion to create unalterable audit trails for important design files, including STL and G-code. Blockchain technology's distributed ledger enables the verification of manufacturing operations' legality by preventing unauthorized access and ensuring the authenticity of files throughout the production process [76,77].

- Developing advanced encryption techniques in conjunction with blockchain technology will help ensure the security of the transport and storage of design files and sensitive data.

5.2.1. AI-Driven System Reliability

- Regularly updating AI models with real-world data helps increase the accuracy of forecasts and flexibility in adapting to changing AM conditions.

- Using hybrid decision-making models that combine AI automation with human supervision can ensure that critical operations deliver reliable results.

5.2.2. The Challenge in Combining Physical and Digital Systems

- Wang et al. (2020) have proposed the application of modular AI frameworks that can adjust to unexpected environments, including material discrepancies.

- Traceability solutions by blockchain technology can closely track the whole production process, and this guarantees that the data obtained from sensors, DTs, and AI models is preserved in a safe manner and can be validated, therefore helping with system synchronization and the resolution of any potential errors [82,83,84,85].

- Edge computing can enable rapid changes within AM processes and facilitate real-time data processing, thereby helping to minimize the number of delays generated by centralized technology [86].

5.2.3. High Costs and Resource Requirements

- Encouragement of open-source projects and industrial partnerships helps enable the distribution of resources, accelerate development, and lower total costs for stakeholders.

5.3. Shortcomings and Proposed Framework

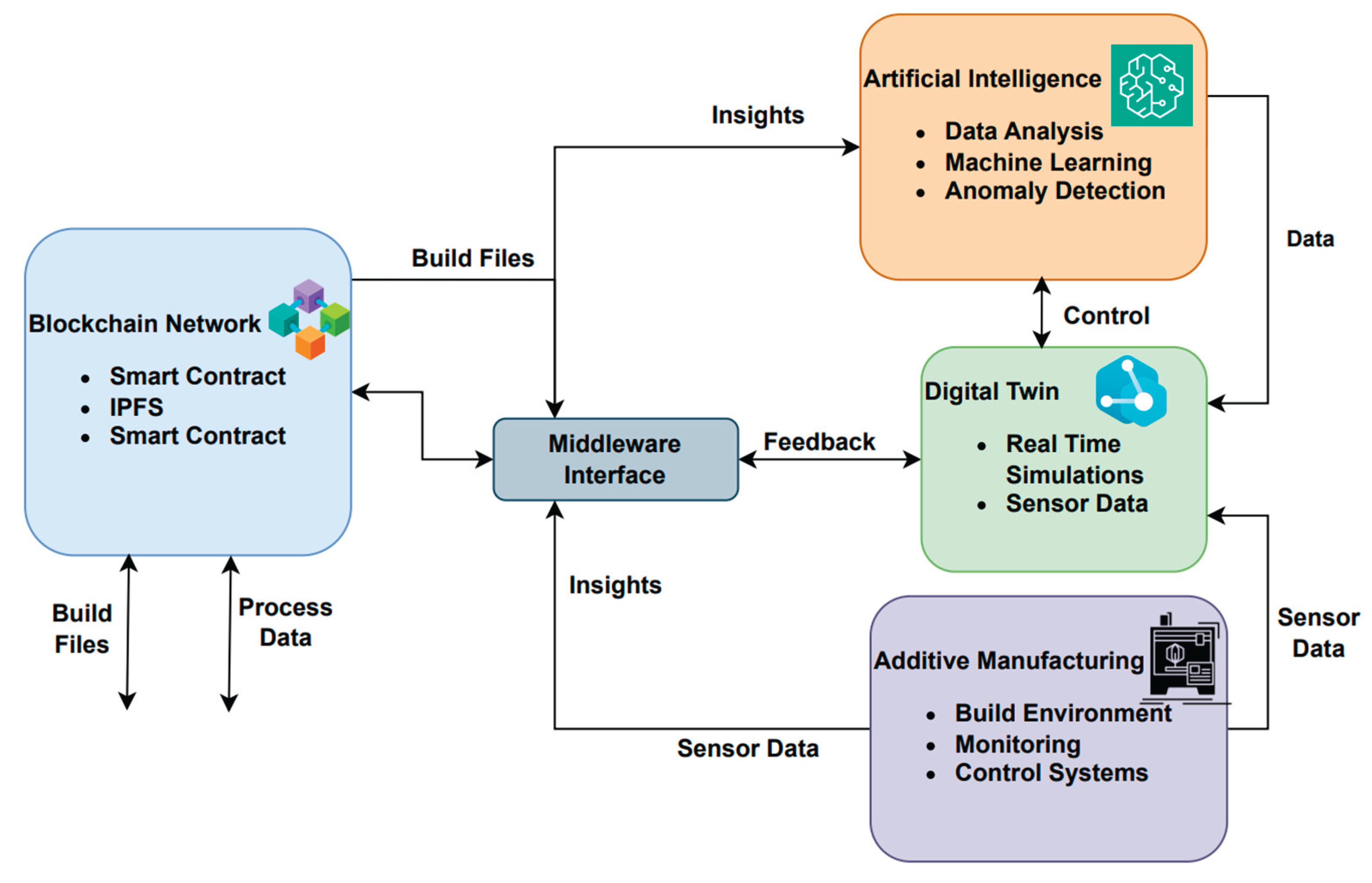

5.3.1. Framework Overview and Architecture

5.3.2. Digital Twin Layer: Real-Time Process Replication and Simulation

- Real-time checking of in-process abnormalities (e.g., overheating, delamination, recoater failures),

- Predictive simulations handling finite element or reduced-order simulations for thermal and residual stress inference,

- Control validation by evaluating expected results against live sensor feedback.

5.3.3. AI Layer: Data-Driven Intelligence and Control Optimization

- Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) for explaining inverse problems such as rebuilding indefinite boundary conditions from partial thermal data [96],

- Deep learning models (e.g., CNNs, LSTMs) trained on prior process data to estimate defect formation, porosity zones, or layer-wise quality differences [97],

- Reinforcement Learning (RL) drivers learn to independently adjust laser power, scan speed, or hatch spaces in real time to enhance process results[98].

5.3.4. Blockchain Layer: Secure Traceability, IP Management, and Smart Contracts

- Generates a tamper-proof audit trail for build records, parameter changes, and failure events [99],

- Implements access control using smart contracts to guarantee only authorized personnel or collaborators can view/edit critical data [100],

- Enables IP protection by combining design files, toolpaths, and quality metrics to unique blockchain logs, preventing unauthorized access or modifications.

5.3.5. Middleware Orchestration: Real-Time Integration and Interoperability

- Event-driven interaction, allowing data triggers (e.g., thermal anomaly detection) to use blockchain transactions or AI-based control updates,

- Standardized data formats and ontologies for inferring sensor feedback, simulation outputs, and blockchain metadata throughout subsystems,

- APIs and microservices for integrating external systems, such as PLM systems, ERP tools, or connected manufacturing networks.

6. Conclusions

- This paper summarizes and critically analyzes multiple data-driven (DT) architectures for additive manufacturing (AM), including mechanical, control, and machine learning-based models, and discusses their role in in-situ monitoring and process optimization.

- This paper reviews the role of dynamic and modular AI frameworks, including PINNs, CNNs, LSTMs, and RL algorithms, in adjusting real-time AM process parameters, such as laser power and scan speed, to optimize build quality.

- The paper proposes a holistic closed-loop architecture that combines a Digital Twin, AI, a blockchain network, and real-time middleware orchestration to enable intelligent control, predictive process optimization, and secure cyber-physical interaction in additive manufacturing (AM) production systems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, M., Fuenmayor, E., Hinchy, E., Qiao, Y., Murray, N., Devine, D.: Digital Twin: Origin to Future. Applied System Innovation. 4, 36 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M., Mehrabi, H., Naveed, N.: An overview of modern metal additive manufacturing technology. J Manuf Process. 84, 1001–1029 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Fei Tao, Meng Zhang, A.Y.C. Nee: Digital Twin Driven Smart Manufacturing. (2019).

- Erol, T., Mendi, A.F., Dogan, D.: Digital Transformation Revolution with Digital Twin Technology. In: 2020 4th International Symposium on Multidisciplinary Studies and Innovative Technologies (ISMSIT). pp. 1–7. IEEE (2020).

- Glaessgen, E., Stargel, D.: The Digital Twin Paradigm for Future NASA and U.S. Air Force Vehicles. In: 53rd AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics and Materials Conference<BR>20th AIAA/ASME/AHS Adaptive Structures Conference<BR>14th AIAA. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Reston, Virigina (2012).

- Grieves, M.: Back to the Future: Product Lifecycle Management and the Virtualization of Product Information. In: Product Realization. pp. 1–13. Springer US, Boston, MA (2009).

- Ahn, D.-G.: Directed Energy Deposition (DED) Process: State of the Art. International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing-Green Technology. 8, 703–742 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.Y.H., Zheng, P., Chen, C.-H.: A state-of-the-art survey of Digital Twin: techniques, engineering product lifecycle management and business innovation perspectives. J Intell Manuf. 31, 1313–1337 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Chen, X., Zhou, W., Cheng, T., Chen, L., Guo, Z., Han, B., Lu, L.: Digital Twins for Additive Manufacturing: A State-of-the-Art Review. Applied Sciences. 10, 8350 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, A., Yavari, R., Montazeri, M., Cole, K., Bian, L., Rao, P.: Toward the digital twin of additive manufacturing: Integrating thermal simulations, sensing, and analytics to detect process faults. IISE Trans. 52, 1204–1217 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Le Roux, L., Körner, C., Tabaste, O., Lacan, F., Bigot, S.: Digital Twin-enabled Collaborative Data Management for Metal Additive Manufacturing Systems. J Manuf Syst. 62, 857–874 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Sujit Rokka Chhetri, Sina Faezi, Mohammad Abdullah Al Faruque: Digital Twin of Manufacturing Systems. , Irvine Irvine, CA 92697-2620, USA (2017).

- Knapp, G.L., Mukherjee, T., Zuback, J.S., Wei, H.L., Palmer, T.A., De, A., DebRoy, T.: Building blocks for a digital twin of additive manufacturing. Acta Mater. 135, 390–399 (2017). [CrossRef]

- DebRoy, T., Zhang, W., Turner, J., Babu, S.S.: Building digital twins of 3D printing machines. Scr Mater. 135, 119–124 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A., Chaudhary, A., Devi, S.: Cyber Security With Emerging Technologies & Challenges. In: 2022 4th International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication Control and Networking (ICAC3N). pp. 1875–1879. IEEE (2022).

- Hossain Faruk, M.J., Tahora, S., Tasnim, M., Shahriar, H., Sakib, N.: A Review of Quantum Cybersecurity: Threats, Risks and Opportunities. In: 2022 1st International Conference on AI in Cybersecurity (ICAIC). pp. 1–8. IEEE (2022).

- Rajasekharaiah, K.M., Dule, C.S., Sudarshan, E.: Cyber Security Challenges and its Emerging Trends on Latest Technologies. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 981, 022062 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, T., DebRoy, T.: A digital twin for rapid qualification of 3D printed metallic components. Appl Mater Today. 14, 59–65 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Thejane, K., du Preez, W., Booysen, G.: Implementing digital twinning in an additive manufacturing process chain. MATEC Web of Conferences. 388, 10001 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Phanden, R.K., Aditya, S.V., Sheokand, A., Goyal, K.K., Gahlot, P., Jacso, A.: A state-of-the-art review on implementation of digital twin in additive manufacturing to monitor and control parts quality. Mater Today Proc. 56, 88–93 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Bi, G., Yao, X., Tan, C., Su, J., Ng, N.P.H., Chew, Y., Liu, K., Moon, S.K.: Multisensor fusion-based digital twin for localized quality prediction in robotic laser-directed energy deposition. Robot Comput Integr Manuf. 84, 102581 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., Lu, Y., Yu, C.: Augmented reality-assisted cloud additive manufacturing with digital twin technology for multi-stakeholder value Co-creation in product innovation. Heliyon. 10, e25722 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Phua, A., Davies, C.H.J., Delaney, G.W.: A digital twin hierarchy for metal additive manufacturing. Comput Ind. 140, 103667 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Kanthimathi, T., Rathika, N., Fathima, A.J., K S, R., Srinivasan, S., R, T.: Robotic 3D Printing for Customized Industrial Components: IoT and AI-Enabled Innovation. In: 2024 14th International Conference on Cloud Computing, Data Science & Engineering (Confluence). pp. 509–513. IEEE (2024).

- Yin Z, H., Wang, L.: Application and Development Prospect of Digital Twin Technology in Aerospace. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 53, 732–737 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Jin, L., Zhai, X., Wang, K., Zhang, K., Wu, D., Nazir, A., Jiang, J., Liao, W.-H.: Big data, machine learning, and digital twin assisted additive manufacturing: A review. Mater Des. 244, 113086 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Yao, X., Liu, K., Tan, C., Moon, S.K.: MULTISENSOR FUSION-BASED DIGITAL TWIN IN ADDITIVE MANUFACTURING FOR IN-SITU QUALITY MONITORING AND DEFECT CORRECTION. Proceedings of the Design Society. 3, 2755–2764 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Jannesari Ladani, L.: Applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning in metal additive manufacturing. Journal of Physics: Materials. 4, 042009 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.A., Adnan, N.A.A., Wahab, D.A., Azman, A.H.: Component design optimisation based on artificial intelligence in support of additive manufacturing repair and restoration: Current status and future outlook for remanufacturing. J Clean Prod. 296, 126401 (2021). [CrossRef]

- He, F., Yuan, L., Mu, H., Ros, M., Ding, D., Pan, Z., Li, H.: Research and application of artificial intelligence techniques for wire arc additive manufacturing: a state-of-the-art review. Robot Comput Integr Manuf. 82, 102525 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Arinez, J.F., Chang, Q., Gao, R.X., Xu, C., Zhang, J.: Artificial Intelligence in Advanced Manufacturing: Current Status and Future Outlook. J Manuf Sci Eng. 142, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Çınar, Z.M., Abdussalam Nuhu, A., Zeeshan, Q., Korhan, O., Asmael, M., Safaei, B.: Machine Learning in Predictive Maintenance towards Sustainable Smart Manufacturing in Industry 4.0. Sustainability. 12, 8211 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Soori, M., Arezoo, B., Dastres, R.: Artificial intelligence, machine learning and deep learning in advanced robotics, a review. Cognitive Robotics. 3, 54–70 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Tan, X.P., Tor, S.B., Lim, C.S.: Machine learning in additive manufacturing: State-of-the-art and perspectives. Addit Manuf. 36, 101538 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Guo, K., Yang, Z., Yu, C.-H., Buehler, M.J.: Artificial intelligence and machine learning in design of mechanical materials. Mater Horiz. 8, 1153–1172 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Qin, J., Hu, F., Liu, Y., Witherell, P., Wang, C.C.L., Rosen, D.W., Simpson, T.W., Lu, Y., Tang, Q.: Research and application of machine learning for additive manufacturing. Addit Manuf. 52, 102691 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Dipak Kumar Banerjee, Ashok Kumar, K.S.: Artificial Intelligence on Additive Manufacturing. International IT Journal of Research. 02, 02 (2024).

- Wang, Y., Zheng, P., Peng, T., Yang, H., Zou, J.: Smart additive manufacturing: Current artificial intelligence-enabled methods and future perspectives. Sci China Technol Sci. 63, 1600–1611 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Masinelli, G., Shevchik, S.A., Pandiyan, V., Quang-Le, T., Wasmer, K.: Artificial Intelligence for Monitoring and Control of Metal Additive Manufacturing. In: Industrializing Additive Manufacturing. pp. 205–220. Springer International Publishing, Cham (2021).

- Heiden, B., Alieksieiev, V., Volk, M., Tonino-Heiden, B.: Framing Artificial Intelligence (AI) Additive Manufacturing (AM). Procedia Comput Sci. 186, 387–394 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z., Zhang, Z., Gu, G.X.: Automated Real-Time Detection and Prediction of Interlayer Imperfections in Additive Manufacturing Processes Using Artificial Intelligence. Advanced Intelligent Systems. 2, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Elambasseril, J., Brandt, M.: Artificial intelligence: way forward to empower metal additive manufacturing product development – an overview. Mater Today Proc. 58, 461–465 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Gu, S., Choi, M., Park, H., Jeong, S., Doh, J., Park, S.: Application of artificial intelligence in additive manufacturing. JMST Advances. 5, 93–104 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. V., Garanger, K., Hardin, J.O., Berrigan, J.D., Feron, E., Kalidindi, S.R.: A generalizable artificial intelligence tool for identification and correction of self-supporting structures in additive manufacturing processes. Addit Manuf. 46, 102191 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Choi, W., Advincula, R.C., Wu, H.F., Jiang, Y.: Artificial intelligence and machine learning in the design and additive manufacturing of responsive composites. MRS Commun. 13, 714–724 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, S., Vykhtar, B., Möbs, N., Kelbassa, I., Mayr, P.: IoT-Based Data Mining Framework for Stability Assessment of the Laser-Directed Energy Deposition Process. Processes. 12, 1180 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, F., Song, J., Zoughi, R.: Electromagnetic Scattering Properties of Metal Powder Cloud for Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF) Additive Manufacturing (AM). IEEE Open Journal of Antennas and Propagation. 1–1 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q., Liu, Z., Yan, J.: Machine learning for metal additive manufacturing: predicting temperature and melt pool fluid dynamics using physics-informed neural networks. Comput Mech. 67, 619–635 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Meng, L., McWilliams, B., Jarosinski, W., Park, H.-Y., Jung, Y.-G., Lee, J., Zhang, J.: Machine Learning in Additive Manufacturing: A Review. JOM. 72, 2363–2377 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Goh, G.D., Sing, S.L., Yeong, W.Y.: A review on machine learning in 3D printing: applications, potential, and challenges. Artif Intell Rev. 54, 63–94 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Tan, X.P., Tor, S.B., Lim, C.S.: Machine learning in additive manufacturing: State-of-the-art and perspectives. Addit Manuf. 36, 101538 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Throne, O., Lăzăroiu, G.: Internet of Things-enabled Sustainability, Industrial Big Data Analytics, and Deep Learning-assisted Smart Process Planning in Cyber-Physical Manufacturing Systems. Economics, Management, and Financial Markets. 15, 49 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Andronie, M., Lăzăroiu, G., Ștefănescu, R., Uță, C., Dijmărescu, I.: Sustainable, Smart, and Sensing Technologies for Cyber-Physical Manufacturing Systems: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability. 13, 5495 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N., Zeadally, S., Vuduthala, A.B.: Cyber-Physical Cloud Manufacturing Systems With Digital Twins. IEEE Internet Comput. 26, 15–21 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Balta, E.C., Pease, M., Moyne, J., Barton, K., Tilbury, D.M.: Digital Twin-Based Cyber-Attack Detection Framework for Cyber-Physical Manufacturing Systems. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering. 21, 1695–1712 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., Cao, H., Yang, G., Lu, T., Wan, S.: Digital Twin of Intelligent Small Surface Defect Detection with Cyber-manufacturing Systems. ACM Trans Internet Technol. 23, 1–20 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Dafflon, B., Moalla, N., Ouzrout, Y.: The challenges, approaches, and used techniques of CPS for manufacturing in Industry 4.0: a literature review. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 113, 2395–2412 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Corallo, A., Lazoi, M., Lezzi, M., Pontrandolfo, P.: Cybersecurity Challenges for Manufacturing Systems 4.0: Assessment of the Business Impact Level. IEEE Trans Eng Manag. 70, 3745–3765 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Wu, M., Song, Z., Moon, Y.B.: Detecting cyber-physical attacks in CyberManufacturing systems with machine learning methods. J Intell Manuf. 30, 1111–1123 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Yampolskiy, M., Horvath, P., Koutsoukos, X.D., Xue, Y., Sztipanovits, J.: Taxonomy for description of cross-domain attacks on CPS. In: Proceedings of the 2nd ACM international conference on High confidence networked systems. pp. 135–142. ACM, New York, NY, USA (2013).

- Wu, M., Moon, Y.B.: Taxonomy for Secure CyberManufacturing Systems. In: Volume 2: Advanced Manufacturing. American Society of Mechanical Engineers (2018).

- Dave, M.: Internet of Things Security and Forensics: Concern and Challenges for Inspecting Cyber Attacks. In: 2022 Second International Conference on Next Generation Intelligent Systems (ICNGIS). pp. 1–6. IEEE (2022).

- Wang, L., Mosher, R.L., Duett, P.: Cyberattacks and Cybersecurity in Additive Manufacturing. In: SoutheastCon 2024. pp. 1040–1045. IEEE (2024).

- Mahan, T., Menold, J.: Simulating cyber-physical systems: Identifying vulnerabilities for design and manufacturing through simulated additive manufacturing environments. Addit Manuf. 35, 101232 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Mullet, V., Sondi, P., Ramat, E.: A Review of Cybersecurity Guidelines for Manufacturing Factories in Industry 4.0. IEEE Access. 9, 23235–23263 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Raza, A., Memon, S., Nizamani, M.A., Hussain Shah, M.: Machine Learning-Based Security Solutions for Critical Cyber-Physical Systems. In: 2022 10th International Symposium on Digital Forensics and Security (ISDFS). pp. 1–6. IEEE (2022).

- Torbacki, W.: A Hybrid MCDM Model Combining DANP and PROMETHEE II Methods for the Assessment of Cybersecurity in Industry 4.0. Sustainability. 13, 8833 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Daim, T., Yalcin, H., Mermoud, A., Mulder, V.: Exploring cybertechnology standards through bibliometrics: Case of National Institute of Standards and Technology. World Patent Information. 77, 102278 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Sturm, L.D., Williams, C.B., Camelio, J.A., White, J., Parker, R.: Cyber-Physical Vulnerabilities in Additive Manufacturing Systems. Presented at the (2014).

- Turner, H., White, J., Camelio, J.A., Williams, C., Amos, B., Parker, R.: Bad Parts: Are Our Manufacturing Systems at Risk of Silent Cyberattacks? IEEE Secur Priv. 13, 40–47 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Zeltmann, S.E., Gupta, N., Tsoutsos, N.G., Maniatakos, M., Rajendran, J., Karri, R.: Manufacturing and Security Challenges in 3D Printing. JOM. 68, 1872–1881 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z., Mamun, A. Al, Kan, C., Tian, W., Liu, C.: An LSTM-autoencoder based online side channel monitoring approach for cyber-physical attack detection in additive manufacturing. J Intell Manuf. 34, 1815–1831 (2023). [CrossRef]

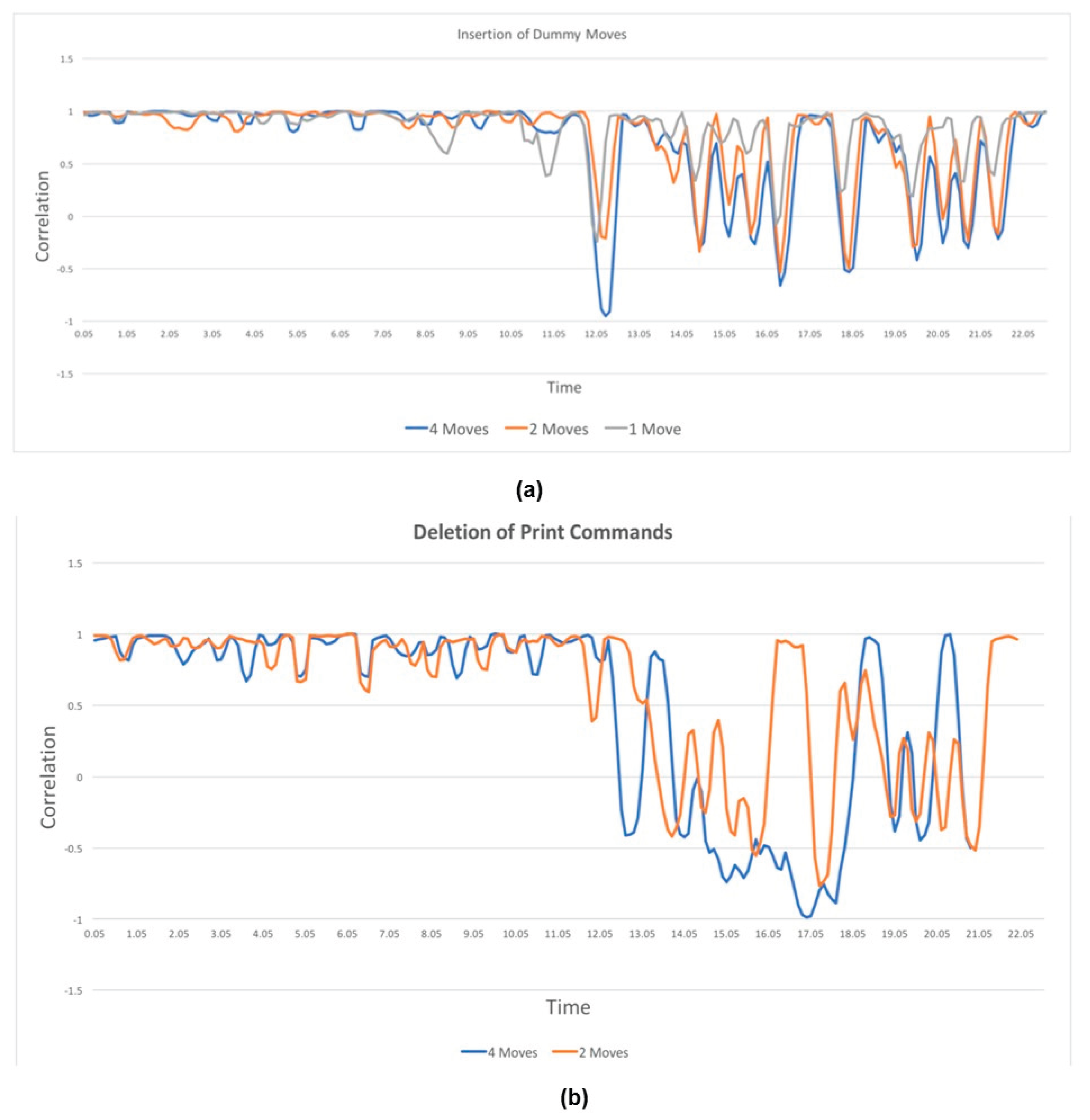

- Sofia Belikovetsky, Yosef Solewicz, Mark Yampolskiy, Jinghui Toh, Yuval Elovici: Detecting Cyber-Physical Attacks in Additive Manufacturing using Digital Audio Signing. (2017).

- Yu, S.-Y., Malawade, A.V., Chhetri, S.R., Al Faruque, M.A.: Sabotage Attack Detection for Additive Manufacturing Systems. IEEE Access. 8, 27218–27231 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Wu, M., Moon, Y.B.: Intrusion Detection of Cyber-Physical Attacks in Manufacturing Systems: A Review. In: Volume 2B: Advanced Manufacturing. American Society of Mechanical Engineers (2019).

- Haridas, A., Samad, A.A., D, V., K, D.L., Pathari, V.: A blockchain-based platform for smart contracts and intellectual property protection for the additive manufacturing industry. In: 2022 IEEE International Conference on Signal Processing, Informatics, Communication and Energy Systems (SPICES). pp. 223–230. IEEE (2022).

- Shi, Z., Kan, C., Tian, W., Liu, C.: A Blockchain-Based G-Code Protection Approach for Cyber-Physical Security in Additive Manufacturing. J Comput Inf Sci Eng. 21, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Haw, J., Dola, T.A., Sing, S.L., Tan, E.Y.S., Liu, A.Z.: Blockchain for Additive Manufacturing. In: Additive Manufacturing Design and Applications. pp. 582–587. ASM International (2023).

- Westphal, E., Leiding, B., Seitz, H.: Blockchain-based quality management for a digital additive manufacturing part record. J Ind Inf Integr. 35, 100517 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Lupi, F., Cimino, M.G.C.A., Berlec, T., Galatolo, F.A., Corn, M., Rožman, N., Rossi, A., Lanzetta, M.: Blockchain-based Shared Additive Manufacturing. Comput Ind Eng. 183, 109497 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Alkhader, W., Alkaabi, N., Salah, K., Jayaraman, R., Arshad, J., Omar, M.: Blockchain-Based Traceability and Management for Additive Manufacturing. IEEE Access. 8, 188363–188377 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Guo, D., Ling, S., Li, H., Ao, D., Zhang, T., Rong, Y., Huang, G.Q.: A framework for personalized production based on digital twin, blockchain and additive manufacturing in the context of Industry 4.0. In: 2020 IEEE 16th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE). pp. 1181–1186. IEEE (2020).

- Ghimire, T., Joshi, A., Sen, S., Kapruan, C., Chadha, U., Selvaraj, S.K.: Blockchain in additive manufacturing processes: Recent trends & its future possibilities. Mater Today Proc. 50, 2170–2180 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Chadha, U., Abrol, A., Vora, N.P., Tiwari, A., Shanker, S.K., Selvaraj, S.K.: Performance evaluation of 3D printing technologies: a review, recent advances, current challenges, and future directions. Progress in Additive Manufacturing. 7, 853–886 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Kurpjuweit, S., Schmidt, C.G., Klöckner, M., Wagner, S.M.: Blockchain in Additive Manufacturing and its Impact on Supply Chains. Journal of Business Logistics. 42, 46–70 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Nain, G., Pattanaik, K.K., Sharma, G.K.: Towards edge computing in intelligent manufacturing: Past, present and future. J Manuf Syst. 62, 588–611 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Sæterbø, M., Arnarson, H., Yu, H., Solvang, W.D.: Expanding the horizons of metal additive manufacturing: A comprehensive multi-objective optimization model incorporating sustainability for SMEs. J Manuf Syst. 77, 62–77 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Haug, A., Wickstrøm, K.A., Stentoft, J., Philipsen, K.: Adoption of additive manufacturing: A survey of the role of knowledge networks and maturity in small and medium-sized Danish production firms. Int J Prod Econ. 255, 108714 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Simeone, A., Caggiano, A., Zeng, Y.: Smart cloud manufacturing platform for resource efficiency improvement of additive manufacturing services. Procedia CIRP. 88, 387–392 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A., Shakur, M.S., Ahamed, Md.S., Hasan, S., Rashid, A.A., Islam, M.A., Haque, Md.S.S., Ahmed, A.: A Cloud-Based Cyber-Physical System with Industry 4.0: Remote and Digitized Additive Manufacturing. Automation. 3, 400–425 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Haghnegahdar, L., Joshi, S.S., Dahotre, N.B.: From IoT-based cloud manufacturing approach to intelligent additive manufacturing: industrial Internet of Things—an overview. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 119, 1461–1478 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S., KC, S.: Leveraging Blockchain for sustainability and supply chain resilience in e-commerce channels for additive manufacturing: A cognitive analytics management framework-based assessment. Comput Ind Eng. 176, 108995 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Tao, F., Zhang, H., Liu, A., Nee, A.Y.C.: Digital Twin in Industry: State-of-the-Art. IEEE Trans Industr Inform. 15, 2405–2415 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q., Tao, F.: Digital Twin and Big Data Towards Smart Manufacturing and Industry 4.0: 360 Degree Comparison. IEEE Access. 6, 3585–3593 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Leng, J., Zhang, H., Yan, D., Liu, Q., Chen, X., Zhang, D.: Digital twin-driven manufacturing cyber-physical system for parallel controlling of smart workshop. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 10, 1155–1166 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Raissi, M., Perdikaris, P., Karniadakis, G.E.: Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J Comput Phys. 378, 686–707 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Equbal, M.A., Equbal, A., Khan, Z.A., Badruddin, I.A.: Machine learning in additive manufacturing: A comprehensive insight. International Journal of Lightweight Materials and Manufacture. 8, 264–284 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Zheng, P., Yin, Y., Wang, B., Wang, L.: Deep reinforcement learning in smart manufacturing: A review and prospects. CIRP J Manuf Sci Technol. 40, 75–101 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Alkhader, W., Alkaabi, N., Salah, K., Jayaraman, R., Arshad, J., Omar, M.: Blockchain-Based Traceability and Management for Additive Manufacturing. IEEE Access. 8, 188363–188377 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Christidis, K., Devetsikiotis, M.: Blockchains and Smart Contracts for the Internet of Things. IEEE Access. 4, 2292–2303 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.: Industry 4.0: A survey on technologies, applications and open research issues. J Ind Inf Integr. 6, 1–10 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Monostori, L.: Cyber-physical Production Systems: Roots, Expectations and R&D Challenges. Procedia CIRP. 17, 9–13 (2014). [CrossRef]

| Reference | Contributions | Future scope |

|---|---|---|

| [10] |

|

A single in-situ sensor monitors only temperature distribution but additional process parameters such as laser power, scan speed, layer thickness etc., can extend the accuracy of flaw detection across various AM methods |

| [12] |

|

Advanced AI and ML Integration with cyber-physical systems can improve real-time data analytics capabilities to facilitate predictive insights |

| [11] |

|

The DT-enabled collaborative data management system can have ML-enabled advanced data analytics developed and implemented and applied in it |

| [13] |

|

Implementing predictive models that can adapt in real time to changing conditions during the AM process is a significant challenge. It needs more validation and a verification process |

| [14] |

|

The development of a comprehensive database and Quantitative study of solidification texture can be explored |

| [18] |

|

Enhanced data integration and open-source collaboration can improve the DT applications in AM |

| [19] |

|

To improve the AM process chain, it is crucial to guarantee the validity and verifiability of the possible basic self-learning strategies as well as to better control data |

| Reference | AI Model | Contribution in AM (What they did and what are the results) |

|---|---|---|

| [37] | ANN | AI into AM, leading to the development of closed-loop AM systems and DTs |

| [38] | Deep learning | A smart AM framework based on cloud-edge computing |

| [39] | ML | an innovative approach for online quality monitoring of AM employing acoustic emissions |

| [40] | AI | The osmotic manufacturing method was proposed as a concept to apply additive manufacturing techniques together with graph theory |

| [41] | Deep learning | A real-time computing-based self-monitoring system has been designed to classify the several degrees of delamination that could arise in a printed part |

| [42] | ML and Deep learning | An overview of AI in AM for a closed-loop system is presented |

| [43] | AI | Shows how artificial intelligence may increase design efficiency, help discover materials, maximize additive manufacturing techniques, and guarantee the quality of outputs generated by AM |

| [44] | A generalizable AI | A fully automated workflow across several AM systems should be used for the aim of supporting quick autonomous process parameter discovery and/or enhanced scientific understanding |

| [45] | AI | It speeds up simulations, improves the selection of materials, facilitates the design of novel structures with multiple functionalities, and cuts down on both time and money spending |

| Major Attacks | Subcategory Attack | Attack Model | Existing Solutions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware Attacks | Side channel attacks | Acoustic Analysis, Electromagnetic Attacks, Power Analysis, Data Residuals, Environmental Exploits, Trimming Exploits, Cache Side-Channel, Differential Faults |

|

[62,63,64,65,66,67,68] |

| Physical attacks | Physical Damage, Chip Decapsulation, Node Jamming, Node Tampering, Fake Node Injection, Code Injection, Sleep Deprivation Attack RF Interference |

|||

| Network attacks | Outage attacks, DoS, tag cloning, camouflage, Man in the Middle, micro probing, traffic analysis, object replication | |||

| Data Attacks | Data exposure, leakage, loss, and scavenging; account hijacking; brute force; hash collision; malicious VM (virtual machine); and VM hopping | |||

| Software Attacks | Firmware attacks | Malware, reverse engineering, control hijacking, eavesdropping | ||

| Operating system attacks | Malware, worm, virus, Trojan, phishing, brute force, back door | |||

| Web application attacks | Malware, spyware, DDoS, pathbased DoS, reprogram attacks, malicious code injection, exploitation for reconfiguration |

| Reference | Attack Type | Detection Method | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| [69] | Malicious void Consequence | The effect on the mechanical strength of a printed specimen was investigated by means of a "printed void" | 14% reduction in yield load |

| [70] | Dimensions Change | Developed the Bayesian game, computing Bayes-Nash equilibria | Operators under attack were not aware of dimensional change without reminding |

| [71] | Printing orientation | Mechanical testing, finite element analysis, and ultrasonic inspection | Strength, failure strain reduction |

| [55] | Malicious void Consequence | Presented DTs utilizing data-driven ML models, and physics-based models | Drone propeller fatigue life reduction |

| [72] | Inside the hole of a solid block |

|

|

| [59] | Different infill defect patterns | RNN, Random Forest, and anomaly detection | The accuracy of anomaly detection is 96.6% |

| [73] | Alternation of G code | Audio fingerprint comparison | The detection rate of the deviation at the time of its occurrence was 100% |

| [74] | Vulnerability in critical components named Gear and Wrench | ML Model | Proposed robust detection systems to prevent structural failures |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).