1. Most-Favored-Nation Drug Pricing Executive Order

In May 2025, the Trump Administration published an executive order titled “Delivering Most-Favored-Nation Prescription Drug Pricing to American Patients.” The order aims to address the longstanding issue of higher prescription drug prices in the United States compared to other developed countries. Americans are believed to end up subsidizing pharmaceutical innovation worldwide, as pharmaceutical companies sell medicines at much lower prices outside the U.S., whilst charging American consumers two or even triple the prices for the same medicines. The order supports American patients enjoying the “most-favored-nation” (MFN) discounting—the lowest available price for a drug in any comparably developed nation.

The Order instructs federal agencies, specifically the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), to negotiate MFN rates with pharmaceutical companies. If negotiations break down, the HHS may recommend rulemaking that requires MFN prices, explore certifying the importation of less expensive medicines, and engage in antitrust enforcement. The policy also seeks to facilitate direct consumer purchases at MFN prices and engage in trade enforcement to push back against foreign price practices. The end objective is to decrease domestic drug prices while deterring worldwide “freeloading” off U.S. R&D.

Table 1.

Drug Prices in the U.S. vs. Other Countries.

Table 1.

Drug Prices in the U.S. vs. Other Countries.

| Drug (Brand Name) |

U.S. Price |

UK / Germany Price |

Canada Price |

% Difference (U.S. vs Others) |

| Humira (adalimumab) |

~$7,000/month |

~$1,060/month (UK) |

$1,325 / Month |

~+560% |

| Lantus (insulin glargine) |

~$276/vial |

~$75/vial (UK) |

~$114/vial |

~+140% to +270% |

| Xarelto (rivaroxaban) |

~$532/month (Medicare) |

~$150–180/month |

~$90–150/month |

~+250% to +490% |

| Eliquis (apixaban) |

~$500/month |

~$130/month (Germany/UK) |

~$120–150/month |

~+215% to +320% |

| Harvoni (Hepatitis C drug) |

~$94,500/course |

~$47,000–60,000/course |

~$47,000–60,000/course |

~+60% to +100% |

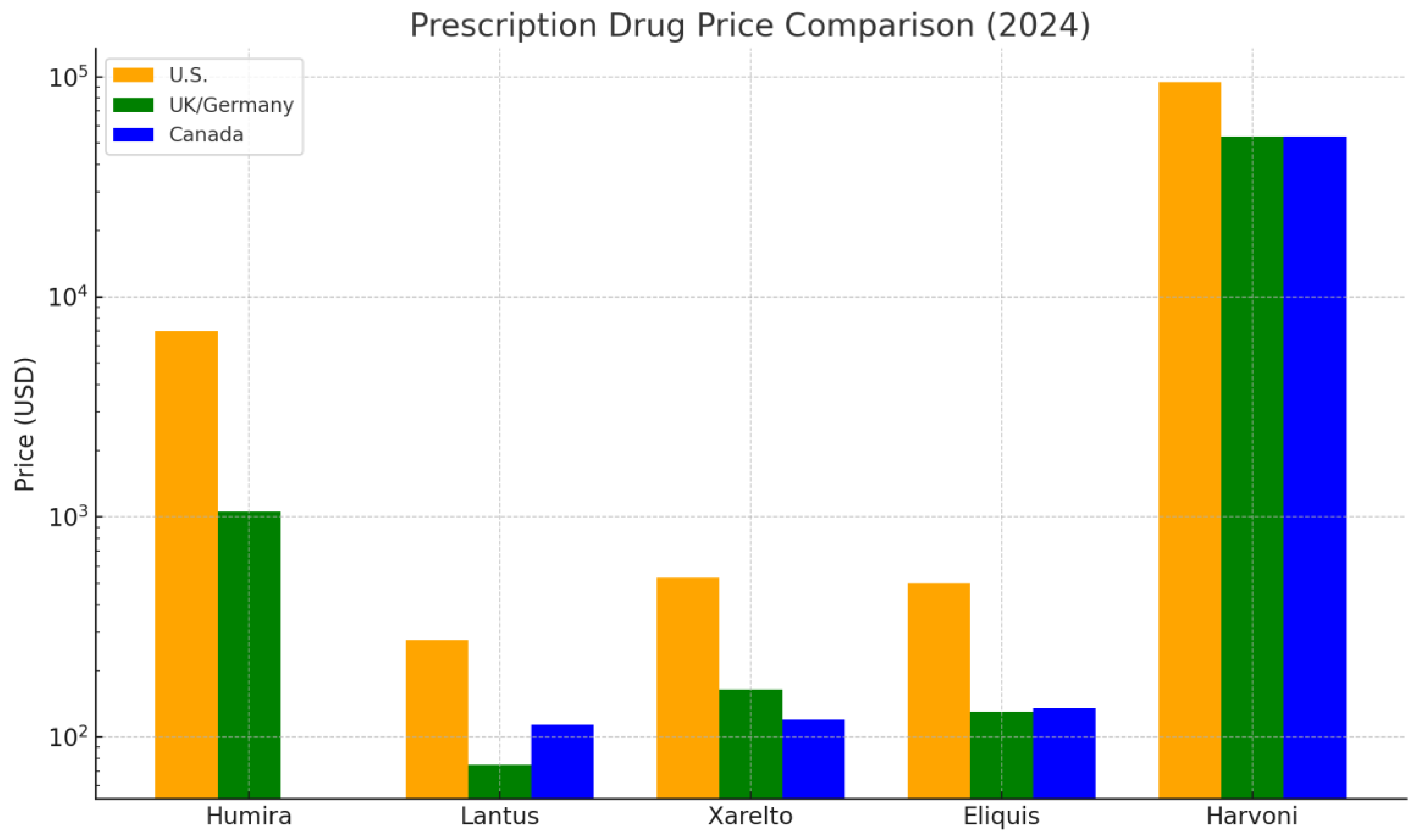

Figure 1.

Prescription Drug Price Comparison (2024), This chart compares U.S. prescription drug prices with those in the UK/Germany, and Canada. U.S. prices are consistently higher, with differences ranging from ~60% to over 500%. A log scale is used due to wide price disparities.

Figure 1.

Prescription Drug Price Comparison (2024), This chart compares U.S. prescription drug prices with those in the UK/Germany, and Canada. U.S. prices are consistently higher, with differences ranging from ~60% to over 500%. A log scale is used due to wide price disparities.

To approximate the differentials in prices, academics generally apply cross-country comparisons based on data from the IQVIA MIDAS database, aggregating brand-name and generic drug prices in a standardized form by country. Volume-weighted and unweighted average prices for a basket of standard drugs, adjusted for exchange rates and dose equivalency, were applied by the RAND Corporation (2021). Similarly, as a basis for comparison, public health systems such as the NHS (UK), the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (Canada), and those in the U.S. list prices, as well as net prices after rebates, are compared by OECD and CBO studies.

Other methods include regression models that adjust for confounding factors such as market size, R&D investment, patent laws, and therapeutic class. Some studies also account for the availability of generics and biosimilars, which significantly affect prices in markets with price regulation. These models demonstrate that the U.S. consistently pays higher prices, primarily due to the lack of centralized negotiation and the highly fragmented insurance coverage structure.

2. Projected Effects of the Executive Order

The implementation of the Executive Order would significantly reduce prices for expensive drugs covered by Medicare by tying them to international prices. It is, however, contingent on regulatory enforcement as well as feasibility in a legal sense. If enforced vigorously, the order can cut U.S. spending on targeted drugs by 20–30% (CBO, 2023). Critics caution against potential restrictions on access if pharmaceutical manufacturers withdraw stock or curtail research and development efforts.

When the U.S. adopts MFN prices, drug companies could seek to recoup profits by increasing prices in those countries that already enjoy reduced rates. This could put foreign healthcare systems, especially those with weaker negotiation power, under strain and upset international drug pricing models. Alternatively, companies could cut global prices to ensure consistency and accessibility.

There is a valid concern that declining revenues in the U.S. could lead to a reduction in budgets for worldwide R&D, as the U.S. accounts for approximately 60–75% of global pharmaceutical profits (IQVIA, 2022). Others contend that pharma R&D is insufficiently funded and could withstand some price reductions; yet others fear that innovation, particularly for orphan drugs and biologic medicines, would be slowed if incentives were to fall. Increasing price transparency and value-based pricing may shift investment towards impactful medicines.

3. Value-Based Care

Value-based care (VBC) has become a revolutionary model in healthcare delivery, with efforts underway to replace the fee-for-service system with methods that reward outcomes rather than volume. In essence, VBC ensures that provider reimbursement is aligned with the quality and effectiveness of the care provided, promoting preventive services, coordination, and patient-oriented interventions. Evidence continues to grow in support of the idea that value-based models can successfully decrease total healthcare spending without compromising quality, even with improvements. Three studies involving value-based insurance design (VBID), strategic approaches to national health services, and nursing resource management illustrate how VBC efforts have reduced costs and improved outcomes.

One of the best-researched VBC strategies is Value-Based Insurance Design (VBID), which aligns patient out-of-pocket expenses with the intended clinical value of services. The approach is simple: making essential medicines and valuable treatments more affordable increases compliance, leading to improved subsequent health outcomes and averted expensive complications or hospitalizations. Mahoney et al. (2013) report in-depth results on the application of VBID in employer-sponsored health coverage. In the case of chronic conditions like diabetes and asthma, they found that eliminating economic barriers to evidence-based services resulted in higher compliance and a decrease in overall healthcare expenditures. Not only did this model increase clinical outcomes, but it also improved the efficient use of healthcare services.

In further support, Smith and Fendrick (2022) contend that VBID approaches provide a clinically differentiated strategy for cost-sharing, particularly for economically disadvantaged populations. They identify that reductions in copayments for higher-value medicines directly correlate with improved medication adherence and better disease control. Noting that cost savings may not be uniform everywhere, they add that value-based, targeted VBID interventions have effectively reduced overall costs, especially when targeting conditions with strong correlations between nonadherence and preventable hospitalizations, as well as accelerated disease progression. Together, these studies suggest that VBID is a practical and scalable model for VBC, which keeps costs low and avoids expensive downstream complications.

Another area with promise for implementing Value-Based Care (VBC) lies in publicly funded national health systems. O’Donnell et al. (2023) investigated the application of VBC principles by the National Health Service (NHS) in Wales for diabetes care, with a focus on prevention, early detection, and patient-oriented interventions. By opening a specific VBHC (Value-Based Health Care) office, the NHS targeted investments in interventions that generated the best long-term outcomes while eliminating low-value practices. Outcomes included improvements in patient outcomes, as well as reductions in unnecessary spending.

This approach involved transitioning from reactive treatments to proactive health management. For instance, by investing in early screening for diabetic complications and patient self-management education, the Welsh system pre-empted expensive emergency interventions and hospitalizations. These efforts proved that by accessing the entire chain of care and adapting interventions, national health systems can maximize clinical and economic benefits. O’Donnell et al. (2023) also suggest that the Health Service Executive (HSE) in Ireland has begun implementing similar approaches, indicating an increasing acceptance that VBC can be applied and is valuable in resource-limited, publicly funded environments.

These savings occur not from spending less on care but from shifting spending into higher-impact, patient-focused services. As the study shows, publicly funded systems can strategically utilize VBC to balance constrained funding, promote health equity, and realize measurable savings, particularly in controlling chronic conditions that dominate healthcare budgets.

The third study, by Caspers and Pickard (2013), examines the use of value-based care in nursing practice across 14 hospitals. Caspers and Pickard proposed the Value-Based Resource Management (VBRM) model, which incorporates real-time clinical information from electronic medical records (EMRs) into nursing processes. This data-driven system enabled hospitals to make more informed staffing decisions, reduce unnecessary overtime, and manage patients’ length of stay. The initiative resulted in increased patient satisfaction and measurable cost savings, highlighting the overlap between total efficiency and patient-centered care.

Caspers and Pickard (2013) highlight the potential for applying VBC concepts at the operational level to deliver quantifiable financial returns. By leveraging patient acuity and predictive analytics, participating hospitals can adjust care delivery to maximize the utilization of available resources without compromising quality. The study also challenges conventional resource management methods by asserting that aligning staff and resource allocation with patient outcomes, rather than schedules or budgets, represents a more effective approach to generating value.

Their conclusions also have broader implications for healthcare systems transitioning to value-based payment systems. The integration of nursing information with outcome measures enhances the coordination of patient care and supports population health planning, enabling a more responsive and cost-sensitive model for healthcare.

Although the evidence suggests that VBC reduces overall healthcare expenditures, it is essential to recognize that successful adoption requires large-scale structural and cultural changes. These involve investment in interoperable information systems, interdisciplinary collaboration, and the re-education of health workers in outcomes-oriented models of care. Furthermore, there is an upfront investment in implementing numerous such programs, such as purchasing predictive analytics software or setting up coordination-of-care teams.

However, long-term economic advantages—such as lower hospitalizations, better control of chronic conditions, and decreased emergency interventions—usually take precedence over upfront costs. Furthermore, as demonstrated by the three studies, models of VBC prove adaptable to both public and private healthcare systems in various clinical settings. The flexibility lies in adapting VBC methods—such as in the case of VBID for private insurance or in managing diabetes within national-level systems—so that they can be implemented without compromising efficiency, equity, or quality.

These studies demonstrate that when carefully implemented, value-based care can reduce the overall cost of care and improve outcomes. Mahoney et al. (2013) and Smith and Fendrick (2022) present how VBID programs increase compliance and decrease downstream spending. O’Donnell et al. (2023) demonstrate how countries, such as the NHS in Wales, achieved improved outcomes by deliberately allocating resources for chronic illness. Lastly, Caspers and Pickard (2013) demonstrate how nursing efficiencies can translate to hospital-level savings. These results demonstrate that value-based care is a necessary and feasible reform for enhancing population well-being and cost control.

4. Value-Based Care Does Not Reduce the Overall Expense of Care

Value-based care (VBC) is commonly advocated as a reform-oriented approach expected to increase quality and decrease spending. Nevertheless, despite the theoretical attractiveness and promise in early periods, the empirical evidence for its effect on total spending is inconsistent. In the field, several well-designed studies have demonstrated that VBC models, including value-based insurance design (VBID), bundled payments, and pay-for-performance approaches, have consistently failed to decrease total spending in practice. Although VBC improves medication adherence, patient satisfaction, and clinical outcomes in several instances, the promise of guaranteed savings has not been reliably fulfilled. The synthesis presented here examines results from three landmark studies that demonstrate, in various ways, that worthwhile value-based care does not necessarily end in cost savings.

A systematic review by Lee et al. (2013) extensively evaluated the impacts of VBID programs on patient expenditure, medication use, and healthcare spending. VBID eliminates or reduces copayments for valuable medications, aiming to enhance patient medication adherence, particularly for those with chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular illness. The review noted that improved medication adherence through VBID was achieved by 3.0% in a year and significantly decreased out-of-pocket spending for patients. These clinical benefits, however, failed to translate into meaningful changes in total patient or insurer spending.

The study’s methodology comprised a review of 13 observational studies from various databases, including PubMed, EconLit, and Embase, among others. Despite improvements in drug compliance, increases in prescription drug expenditures typically offset potential savings from decreased hospitalizations or emergency department visits, according to Lee et al. (2013). In addition, there was limited evidence from the literature that VBID had a clinical impact beyond improved compliance, as numerous studies were constrained by brief follow-up periods or lacked control groups. Therefore, notwithstanding the value of being a quality-improvement measure, the potential for savings through VBID is not established in the short to medium term.

These conclusions were supported by Agarwal et al. (2018), who undertook another review and established moderate-quality evidence that, although medication prescribing improved with VBID programs, they had a neutral impact on overall healthcare spending. Increased drug costs were often offset by marginal decreases in the use of other services, resulting in no net change in spending. Therefore, even as VBID improves the quality of care for chronic diseases, whether it reduces overall costs is questionable.

Another prominent VBC strategy—bundled payments—has also demonstrated similar limitations in cost-effectiveness. Ryan et al. (2019) studied the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) model, a Medicare program bundling payments for joint replacement. The study included over 1,200 total knee arthroplasties at a single institution, both before and after the implementation of CJR. As the model sought to align payments with quality and efficiency, the study found that shifting to bundled payments did not translate to reduced hospital spending. In contrast to modest improvements in quality scores and the absence of biased patient selection, there was no statistically different change in the cost of care.

This is especially significant as joint replacement surgeries are big-volume, expensive procedures typically targeted by VBC reform efforts. The fact that the CJR model cannot save on hospital costs is a cause for concern that greater big-picture coordination and shared risk may not, in every situation, translate to decreased spending. The study highlights that even in instances where improvements in processes—e.g., fewer complications, shorter hospital stays—are achieved, the delivery of complex care can remain as expensive as before due to structural, labor, and material costs that cannot be altered.

Additionally, bundled payments are often hindered by implementation challenges, which diminish their effectiveness. Significant investments in data capabilities, coordination, and staff training may be necessary for hospitals to adapt to the requirements of bundled payments, thereby negating the potential savings. The financial savings for bundled models, as proposed by Ryan et al. (2019), may be realized under certain conditions or over a longer time horizon.

In a third study by Leao et al. (2023), the authors systematically evaluated 40 studies that represented value-based payment (VBP) models, ranging from shared savings to pay-for-performance arrangements. Although numerous models had a positive impact on clinical quality and patient outcomes, the impact on cost savings was inconsistent. Most VBP programs had no impact or had achieved only marginal reductions in spending. Additionally, the provider’s experience with VBP was generally negative, citing issues such as program complexity, misaligned incentives, and a lack of trust.

The review highlighted that reductions in preventable hospitalizations and improvements in the control of chronic conditions were observed in some VBP models. However, those benefits often accrue at the expense of higher administrative costs, incentive payments, or expenditures for quality measurement systems. Providers also cited that the effort to achieve VBP targets—including reporting, tracking, and restructuring—often provided scant financial rewards.

Leao et al. (2023) observed that enabling factors for successful cost savings through VBP models comprised well-specified goals, sound performance measurements, and well-coordinated communication among stakeholders. In most actual environments, however, such enabling factors were present in a weak form or not at all, thereby curbing the effect of reducing total care expenditures through VBP. The study found that, despite improving the quality of care, VBP models are inconsistent in reducing costs, particularly in the absence of supportive systems and properly aligned incentives.

In combination, these three studies contradict the premise that value-based practice models universally decrease spending on healthcare. VBID interventions (Lee et al., 2013; Agarwal et al., 2018) increase compliance and decrease drug expenditures for patients but tend to produce neutral spending results for total costs with offsetting increases in pharmaceutical expenditures. Bundling payments, as in the CJR model (Ryan et al., 2019), increases outcome measurements without corresponding hospital-level savings. Lastly, more comprehensive VBP models (Leao et al., 2023) often encounter implementation difficulties and yield variable outcomes in controlling costs.

The variable extent of cost savings in VBC efforts indicates that financial efficiency could be achieved through a more system-level, integrated approach. This might include optimizing the pay-for-performance design for VBC, creating longer-term timelines for implementing efforts, and implementing efforts that target population health approaches that tackle determinants in the social environment. Policymakers must also recognize that improved outcomes and saved expenditures may not always occur concurrently and that quality-cost compromises vary by setting.

5. Evaluation and Policy Recommendation

Two fundamental questions frame the debate on value-based care (VBC): Does it improve the quality of care while reducing total spending? The answer is multifaceted, as evidenced by both findings (Parts 2a and 2b). Although solid evidence supports the notion that value-based care enhances patient outcomes—such as medication adherence, chronic disease control, and care coordination—the evidence that the intervention reduces total costs is less robust. In synthesizing the findings, I believe that the evidence indicating that value-based care does not uniformly reduce total spending is more substantial and has a broader impact, particularly in the short to medium term.

First, numerous studies have demonstrated that cost savings are contingent upon limited settings, ideal conditions for implementation, or pilot periods involving engaged stakeholders (Agarwal et al., 2018; O’Donnell et al., 2023). Early successes in value-based insurance design (VBID) or models for Welsh diabetic care, for example, generally rely on specialized populations (e.g., at-risk patients) and may not translate well to wider, more heterogeneous systems. Furthermore, such studies generally lack well-designed control groups or extended follow-up periods to determine whether persistent cost reductions are achieved.

In comparison, studies that challenge the potential for cost savings through VBC are more comprehensive in scope and methodologically robust. For example, Lee et al. (2013) undertook a structured review of 13 VBID projects and found that medication compliance improved, but total medical expenditure did not decrease significantly. Again, Ryan et al. (2019) demonstrated that the CJR model, a leading example of bundled payment reform, did not decrease hospital expenditures even as some value-based outcomes improved. Lastly, Leao et al. (2023) surveyed dozens of VBC efforts in numerous countries and pay systems, concluding that clinical improvements typically occurred, but savings were variable or nonexistent.

The weight of that evidence suggests that value-based care, in its current form, can enhance quality, rather than cut spending. This is perhaps because the underlying causes for the costs in the sector—e.g., drug prices, fee-for-service legacy systems, and excessive administrative overhead—are not entirely covered by models of VBC.

Given such realities, a more efficient policy would integrate value-based care principles with targeted reform focused on cost drivers and system equity. A three-pronged approach, as described below, can assist toward a more optimal market result:

Implement VBC in regions or specialty areas with significant cost and outcome variations (e.g., orthopedic surgery, diabetic care). However, it ties reimbursement levels to outcomes and equity-adjusted measurements, such as decreases in preventable hospitalizations in underserved populations. This would not only make VBC outcome-oriented but also socially meaningful.

For big health systems, the transition is from fragmented VBC pilots to global budgets or capitated payments (fixed per-member-per-month arrangements). This induces more substantial financial incentives for prevention and control costs. Maryland’s global hospital budget system is a real-world example of this in practice at scale.

Most failures in VBC are not due to concepts but to their implementation. For this reason, federal policy must invest in interoperable health data systems, predictive analytics, and training for clinicians to provide the necessary tools for success in VBC. In summary, value-based care is valuable, particularly in enhancing quality and patient-oriented outcomes in healthcare.

Nevertheless, it will not automatically decrease costs without addressing structural inefficiencies and providing the appropriate financial and technological support. A hybrid policy that connects equity with value transforms the scale of payment models and establishes robust infrastructure, providing a more pragmatic route to a fair and efficient healthcare system.

6. Conclusion

MFN prices of drugs and value-based care (VBC) are ambitious efforts to address the cost and equity issues of the United States’ health system. The MFN Executive Order establishes a relationship between the nationwide prices of drugs and overseas prices, with the potential for significant societal savings, as well as the risk of global price distortions and hindrances to innovation. VBC, on the other hand, improves clinical results within select settings, yet often does not achieve aggregate cost savings, primarily due to structural inadequacies and implementation hurdles.

The accumulated evidence suggests that relying exclusively on either MFN prices or VBC will never resolve the affordability crisis in healthcare. On the contrary, a hybrid solution that combines the cost alignment of MFN prices with VBC’s quality incentives, along with countrywide investment in data infrastructure, as well as an emphasis on equity in high-cost areas, represents our best plausible way forward. Policy leaders must recognize that sustainable reform of this kind requires the alignment of financial, technological, and regulatory tools, with equity and transparency as the keystones of healthcare transformation.

Funding

No specific funding was received for this study.

Ethical Statement

This study did not involve human or animal subjects; hence, ethical approval was not required.

Consent Statement

This is not applicable as the study does not involve individual participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agarwal, R., Gupta, A., & Fendrick, A. M. (2018). Value-based insurance design improves medication adherence without an increase in total health care spending. Health Affairs, 37(7), 1057–1064. [CrossRef]

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH). (n.d.). National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System (NPDUIS).

- Caspers, B. A., & Pickard, B. (2013). Value-based resource management: A model for best value nursing care. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 37(2), 95–104. [CrossRef]

- Commonwealth Fund. (2023). U.S. prescription drug prices in international context. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/.

- German Federal Joint Committee (G-BA). (2024). Reports on pharmaceutical pricing. https://www.g-ba.de/.

- Leao, D. L. L., Cremers, H.-P., van Veghel, D., Pavlova, M., & Groot, W. (2023). The impact of value-based payment models for networks of care and transmural care: A systematic literature review. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 21(3), 441–466. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. L., Maciejewski, M. L., Raju, S. S., Shrank, W. H., & Choudhry, N. K. (2013). Value-based insurance design: Quality improvement but no cost savings. Health Affairs, 32(7), 1251–1257. [CrossRef]

-

Lupkin, S. (2023, July 20). Blockbuster drug Humira finally faces lower-cost rivals. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2023/07/20/1188745297/humira-threatened-by-yusimry-low-cost-rival.

- Mahoney, J. J., Lucas, K., Gibson, T. B., Ehrlich, E. D., Gatwood, J., Moore, B. J., & Heithoff, K. A. (2013). Value-based insurance design: Perspectives, extending the evidence, and implications for the future. The American Journal of Managed Care. https://www.ajmc.com/journals/supplement/2013/ad115_13jun_vbid/ad115_jun13_vbid.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2024). Drug Tariff. https://www.nice.org.uk/.

- O’Donnell, M. T., Lewis, S., Davies, S., & Dinneen, S. F. (2023). Delivering value-based healthcare for people with diabetes in a national publicly funded health service: Lessons from Ireland and Wales. Journal of Diabetes Investigation, 14(8), 925–929. [CrossRef]

- RAND Corporation. (2022). Value-based care: Challenges and insights from implementation across the U.S. RAND Health Quarterly, 9(2), 1–20. https://www.rand.org/pubs/periodicals/health-quarterly/issues/v9/n2.html.

- Ryan, S. P., Plate, J. F., Black, C. S., Howell, C. B., Jiranek, W. A., Bolognesi, M. P., & Seyler, T. M. (2019). Value-based care has not resulted in biased patient selection: Analysis of a single center’s experience in the Care for Joint Replacement Bundle. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 34(9), 1872–1875. [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. K., & Fendrick, A. M. (2022). Value-based insurance design: Clinically nuanced consumer cost sharing to increase the use of high-value medications. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 47(6), 797–813. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). (2024). Medicare Part D Drug Dashboard. https://data.cms.gov/resources/medicare-part-d-spending-by-drug-methodology#:~:text=Associated%20Products-,Background,download%20the%20complete%20methodology%20document.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).