1. Introduction

Venezuelan equine encephalitis (VEE) is caused by VEE virus (VEEV), an alphavirus transmitted by mosquitoes. VEEV is a positive-sense, single stranded RNA genome of 11.5 kb in length [

1]. The virion has an enveloped icosahedral structure approximately 70 nm in diameter. In humans, VEEV causes a biphasic febrile illness that can result in myeloencephalitis with high morbidity, including neurological complications and a mortality rate of approximately 2% [

2]. The initial symptoms of VEE, such as fever and headache, resemble other infections, which complicates clinical diagnosis. In addition, there is considerable overlap between geographic regions of VEEV endemicity and those of some other tropical diseases. For example, an overlap of VEEV with areas of dengue virus may result in an underestimation of VEEV prevalence [

3]. Ecological and climate factors may cause increases in geographical distribution of

Culex mosquitos, transmitting VEEV to humans and equines at risk of contracting the virus [

4]. VEEV is also recognized as a potential biological weapon, due to the severe threat posed to human and animal health, and the minimal infectious aerosol dose required for infection. Finally, VEEV has a history of laboratory-acquired infections [

5,

6,

7]. Taken together, these factors suggest the continuing possibility of VEEV infections and outbreaks, including in non-endemic areas.

Currently, there is no approved VEEV vaccine or therapy for human. The TC-83 vaccine developed in the 1960s has been used as Investigational New Drug (IND) for vaccination of laboratory personnel at risk of infection with VEEV [

8]. The vaccine induces neutralizing antibodies that protect from infection; however, there are several issues regarding the efficacy and safety of the TC-83 as a vaccine for humans. It has been reported that approximately 20% of recipients do not develop neutralizing titer, and more importantly, roughly 20% of vaccinees experience mild to moderate adverse reactions, ranging from inflammatory (e.g. fever, chills, and malaise to neurological (e.g., anorexia) clinical reactions [

8,

9,

10].

Regarding to the safety of VEEV vaccines, it is important to ensure that a VEEV vaccine should have a lack of neuroinvasion property, especially for a live attenuated vaccine for the neurotropic nature of VEEV. Previous reports have demonstrated that attenuating mutations render the virus incapable of CNS invasion[

11]. Immunocompetent mice are able to effectively control the attenuated VEEV strains after subcutaneous (SC) or intramuscular (IM) injections, preventing neuroinvasion. However, some studies have indicated that the VEEV live-attenuated vaccines may be able to gain access to the CNS from the peripheral inoculation site, resulting in a CNS infection in humans or in immunocompetent mice [

11], particularly by a reversion of the attenuating mutations considering the high mutation rate of RNA viruses in general and high diversity of population within VEEV TC-83 sample [

12] .

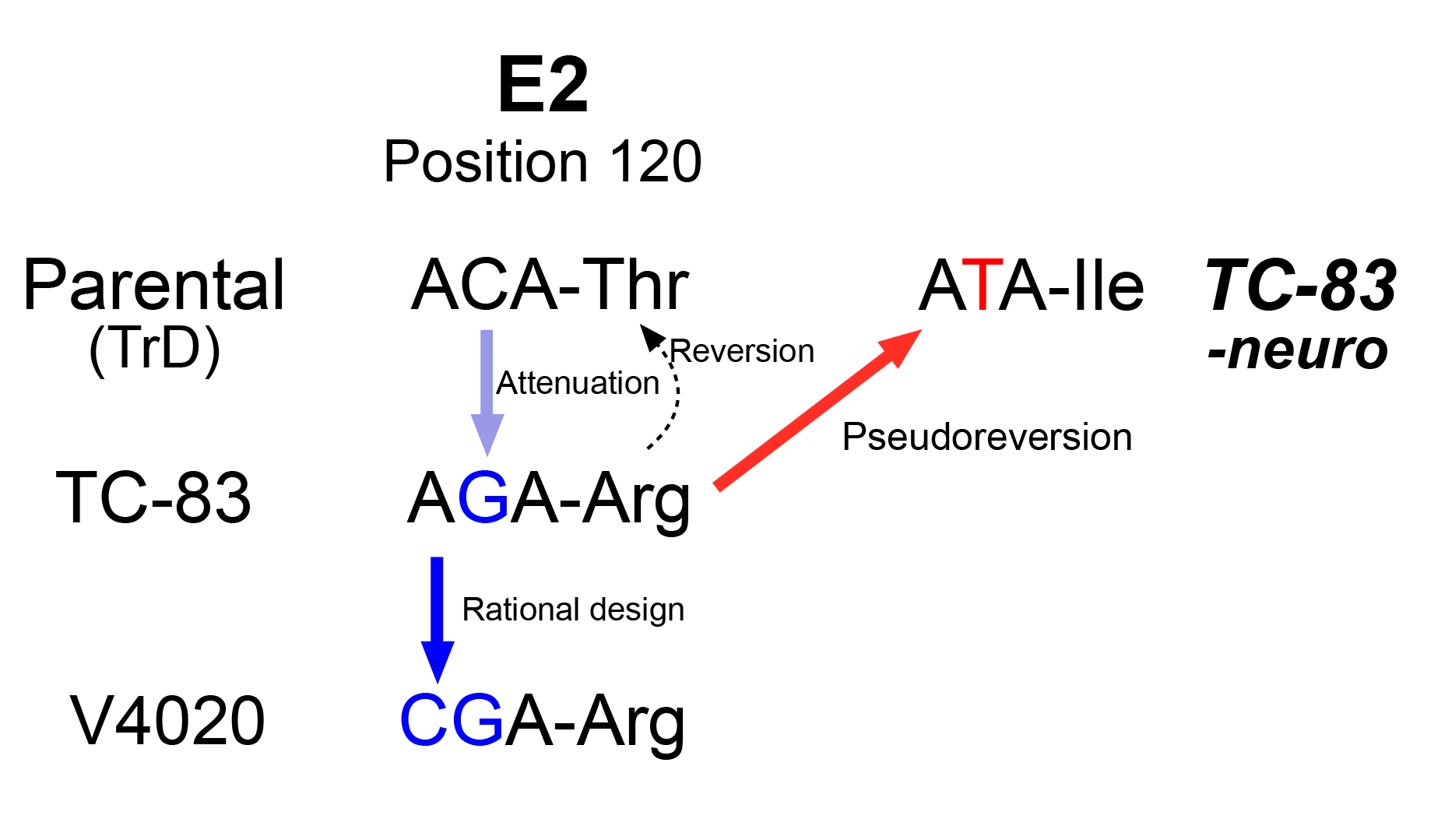

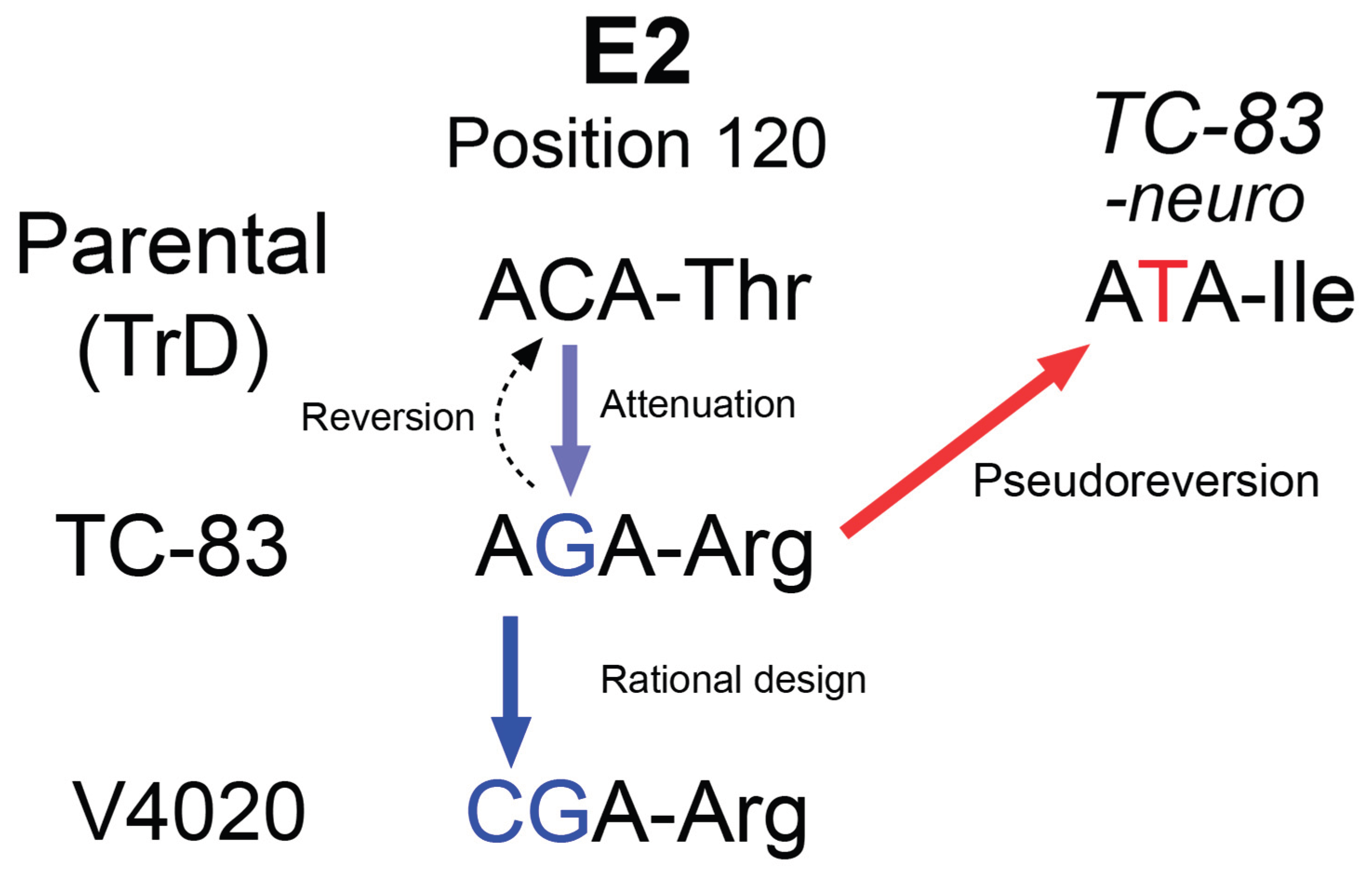

To address this safety concern, we previously developed a live attenuated VEEV vaccine, V4020, which includes the key attenuating mutations of TC-83, namely 5’A3 and E2-Arg120 derived, as well genetic rearrangement of the capsid and glycoprotein genes for an additional attenuation factor[

13,

14,

15] (

Supplementary Figure S1). Importantly, to prevent potential reversions to the wild-type genotype, the translational codon of AGA for the attenuating mutation E2-Arg in the TC-83 was replaced with CGA, synonymous but requiring two point mutations to revert to the wild-type codon ACA encoding E2-Thr as in virulent VEEV strains [

13,

14]. These changes were designed to enhance the safety of the prospective vaccine for human uses[

16,

17].

Here we investigated the potential of neuroinvasion of V4020 in immunocompetent mice and found that V4020 has a considerably lower neuroinvasion potential than that of TC-83. While a few of TC-83 vaccinated mice showed active viral replication in the CNS after a subcutaneous or intramuscular administration, none of mice administered with V4020 showed any signs of virus replication in the brain. We found that TC-83 virus isolated in the CNS has a mutation of R120I in E2 gene, which might have served as a phenotypic reversion (i.e., pseudoreversion), providing a justification for our approach of using a new codon for the residue.

Here we investigated the potential of neuroinvasion of V4020 in immunocompetent mice and found that V4020 has a considerably lower neuroinvasion potential than that of TC-83. We found that a few of TC-83 vaccinated mice showed active viral replication in the CNS after a subcutaneous or intramuscular administration. TC-83 virus isolated in the CNS had a mutation of R120I in E2 gene, which might have served as a phenotypic reversion (i.e., pseudoreversion). However, none of mice administered with V4020 showed any signs of virus replication in the brain, providing a justification for our approach of using a new codon for the residue.

2. Materials and Methods

Vaccine viruses

Test vaccine virus, V4020 (Lot: 20230512) was generated as previously described [

13,

14] and titrated by plaque assay, with titer 9.33x10

7 PFU/mL. The control vaccine stock, VEEV TC-83 (Lot: 20230404/1) was amplified once from TC-83 vaccine (USAMRIID, Fort Detrick, MD) and used as a comparator, with titer 1.11x10

9 PFU/mL. The stock viruses were stored at -80

oC until used. The seed stock of each vaccine virus was diluted to the desired concentration in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and kept on ice before injections.

Neuroinvasion animal model

Mouse, BALB/c (Jackson Laboratory USA, Cat # 000651), 4-6 weeks old were used for SC and IM administration studies. Animals were acclimated 3-5 days prior to being used for experiments. Toe tattoos were applied for identification of individual animals, and three or four same sex mice were housed together as a group. For administration, diluted virus was administered via either SC injection (50 µL per injection) between the shoulder blades or IM injection of 25 µL of dilute virus into each hind leg (total volume of 50 µL per mouse). For the mock infected group, PBS was used in place of virus. For the intranasal (IN) infection model, mouse strain C3H (Charles River Laboratory, USA, Cat # 025), 4-6 weeks old, was used [

18]. After an acclimatation period, diluted vaccine was administered via the IN route in a total volume of 50 µL (25 µL/nare) under anesthesia with isoflurane. All procedures in mice were carried out in accordance with the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and institutional guidelines for animal welfare and use, reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Louisville (Protocol number IACUC 22221, initial approval on 02/07/2023).

In-life monitoring

Animals were observed twice daily for clinical signs starting on day 0 through the end of the study. When it occurs, VEEV-induced encephalitis causes a severe deficit in infected animals in motor activity and morbidity. To evaluate such clinical outcomes, changes in body weight measurement and clinical signs such as activity, grooming, grimace, and neurological behaviors were monitored daily.

Blood cell count

The animals were anesthetized under isoflurane, and blood was collected by using the cardiac puncture technique using a 1 mL syringe and 25G needle. Blood was transferred into BD Microtainer tubes containing K2EDTA and mixed well. The samples were then shipped to the Regional Biocontainment Laboratory and whole blood was processed for a complete blood count using the Hemavet 950 (Drew Scientific) within 48 hours after blood collection.

Brain tissue harvest, fixation, and histopathology

After mice were humanely euthanized, total body perfusion was performed to remove the blood from the tissue by manually pushing PBS into the left ventricle via a 23G butterfly needle out to an incision at the right atrium. The brain was then removed and separated into left and right hemispheres. The right hemisphere was placed into an embedding cassette and submerged in 10% buffered formalin for 12-24 h. The embedded tissues were then subjected to a paraffin embedding, followed by microtome sectioning. Tissue sectioning, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, and pathology scoring were all carried out by the Iowa State University Veterinary Medical Pathology. Tissues were evaluated for any pathological findings by a certified pathologist.

Tissue homogenization

The spinal cord, cerebral cortex, cerebellum, and olfactory bulbs of the left hemisphere were separated and placed into individual homogenization tubes. Additionally, the liver and spleen were collected. The harvested tissues were homogenized in 2 mL tubes prefilled with sterilized 0.5 mm silica beads (Benchmark, Inc.) with two one-minute cycles (Omni BEAD RUPTOR 4) while being kept on ice throughout the entire process. Once homogenized, the tissues were aliquoted into Eppendorf tubes and stored in the –80 °C freezer.

Detection of virus by plaque assay.

The study employed two different methods to detect VEEV in the CNS: virus titrations using plaque assay in cell culture and RNAscope assays to detect any replicating and residual viral RNA. Briefly, samples were serially diluted 10-fold in a virus infectious media (VIM: MEM-E, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 25 mM HEPES). Then, 166 µL per well of serially diluted samples were used to infect Vero 76 cell grown overnight in 24-well plates. After one hour incubation at 37 °C, the supernatant was removed, and the cells were washed with PBS, 0.5 mL per well. A methylcellulose overlay media (0.7% methylcellulose in VIM) was added to the cell plates and incubated for 3 days in a 37 °C CO2 incubator. Virus plaques were developed by using 2% paraformaldehyde and 0.5% crystal violet solution.

Detection of virus by RNAscope assay

To validate the virus brain titrations and to gain spatial information on virus replication in the brain, the RNAscope assay was implemented. Paraffin-embedded brain tissues were sectioned in the sagittal direction, then mounted on glass slides. Viral signal was detected using RNAscope 2.5 HD Detection Reagent – Brown kit (ACD, Cat # 322310), following the manufacturer’s instructions with a VEEV probes set (ACD, Cat # 404501). After DAB staining, and coverslip mounting, final slides were scanned using a Hamatsu NanoZoomer SQ slide scanner for digital image recording.

Viral genome sequence analysis

Virus was amplified from tissue homogenates confirmed with replicating virus in Vero 76 cells once, and 200 PFU equivalent amount of the tissue culture supernatant was used to inoculate Vero 76 cells grown overnight. The next day, total RNA was isolated from the infected cells using RNAZol RT (MRC Inc.) following the manufacturer’s protocol. After removing RNA secondary structures by heating to 65°C for 5mins and placing on ice for another 5mins, cDNA synthesis was performed using 2µM random hexamers (IDT), RT Buffer, RNaseOUT Ribonuclease Inhibitor, 0.5mM dNTPs, and Maxima H-minus Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Scientific), and the structural and non-structural genes were PCR amplified separately using GC buffer, 0.2mM dNTPs, Phusion (Thermo Scientific), and 0.5µM of each primer (IDT), and Phusion with a protocol of: 98°C for 30s, 30 cycles of 98°C for 10s, an annealing temperature of 57.5 °C for 20s, and 72°C for 5mins, then 72°C for 5mins on a S1000 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad). Each amplicon was pooled and purified using 0.5x bead-to-sample volume ratio of KAPA Pure magnetic beads (Roche) and eluted in nuclease-free water. 1 µg of each sample was used in the Nanopore Ligation Sequencing Native Barcode Kit 24 V14. Sequencing was carried out using a MinION Mk1c sequencer with R10.4.1 Flongle flow cells for 20 hours with high accuracy basecalling (Oxford Nanopore Technologies). Minimap2 [

19] was used to align the fastq files that met the Phred quality score threshold to the reference genome sequence (VEEV GenBank: L01442.2), and mpileup [

20] from samtools (now bcftools) was used to identify single nucleotide polymorphism including their frequencies at each position in the target region. For the sequenced samples, the average sequencing depth was 2608x, and the average coverage was 84.61%.

3. Results

3.1. Study Design

The overall study design aimed to detect potential neuroinvasion after administrations of test vaccine at peripheral sites, shown in

Table 1. Current IND vaccine, TC-83, is administered at 1 x 10

5 PFU dose in humans. To evaluate any potential neuroinvasion, a 20-fold excess dose (2 x 10

6 PFU per dose per mouse) was used. Inoculation of vaccines is expected to establish a local, limited replication of vaccine at the injection site. Attenuated strains of VEEV are not expected to have considerable ability to invade the CNS of immunocompetent mice (e.g., BALB/c strain) when they are inoculated via IM or SC route [

11]. Each group consisted of 10 animals per time point (DPI2 and 5) with same number of males and females.

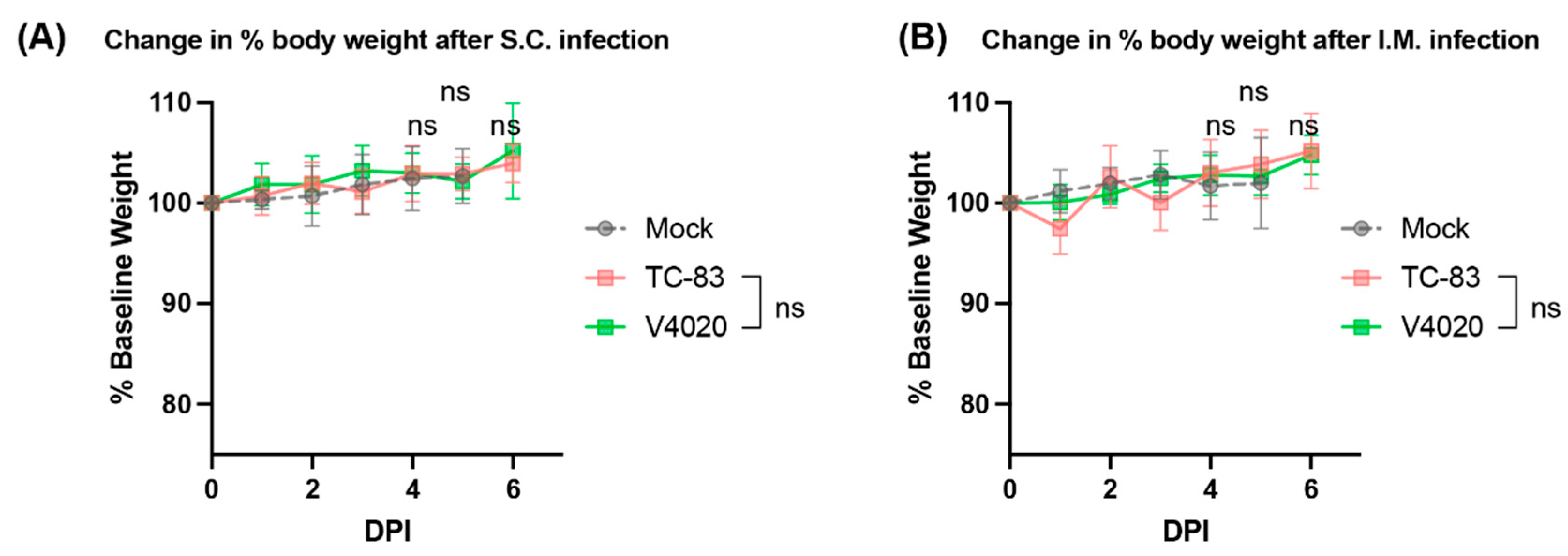

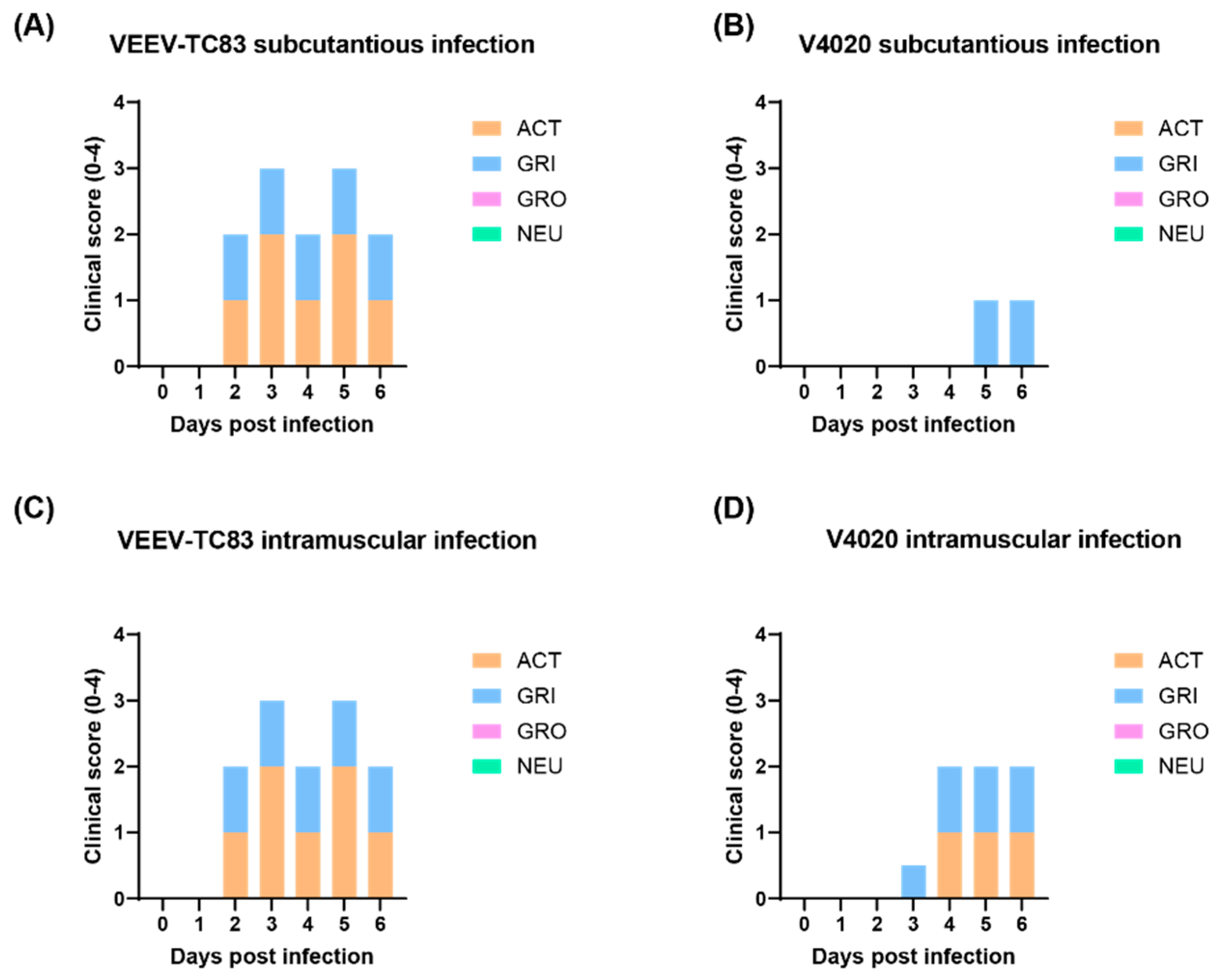

3.2. V4020 Showed Lower Degree Adverse Effects Than TC-83

To evaluate adverse effects induced by vaccination, several clinical signs were analyzed including body weight, activity (ACT), grimace (GRI), grooming GRO), and neurological (NEU) abnormality with a scale of 0-4 (none to severe). The mock group injected with PBS showed no adverse changes in body weight over the course of the study. The groups vaccinated with VEEV TC-83 or V4020 via the SC or IM routes did not show any noticeable decrease in body weight compared to the mock group (

Figure 1), showing no morbidity in the terms of body weight.

For clinical scores (

Figure 2), the mock group injected with PBS did not show any clinical signs, and they behaved normally. The TC-83 group vaccinated via the SC route or the IM route demonstrated moderate level of weakness and slower movements (activity), and the facial expression of pain and squinting (grimace), starting from 2 days post infection (DPI 2) until the end of study (DPI 6). In contrast, the V4020 group, either vaccinated via the SC or the IM, demonstrated low-to-moderate level of the clinical signs starting from DPI 3. Some mice from the IM injection group showed a lower activity starting from DPI 4 until the end of the study (DPI 6). In conclusion, compared to VEEV TC-83, in both the SC and IM infection model, the V4020 group clearly showed a lower degree of clinical morbidity signs than that of TC-83 (

Figure 2).

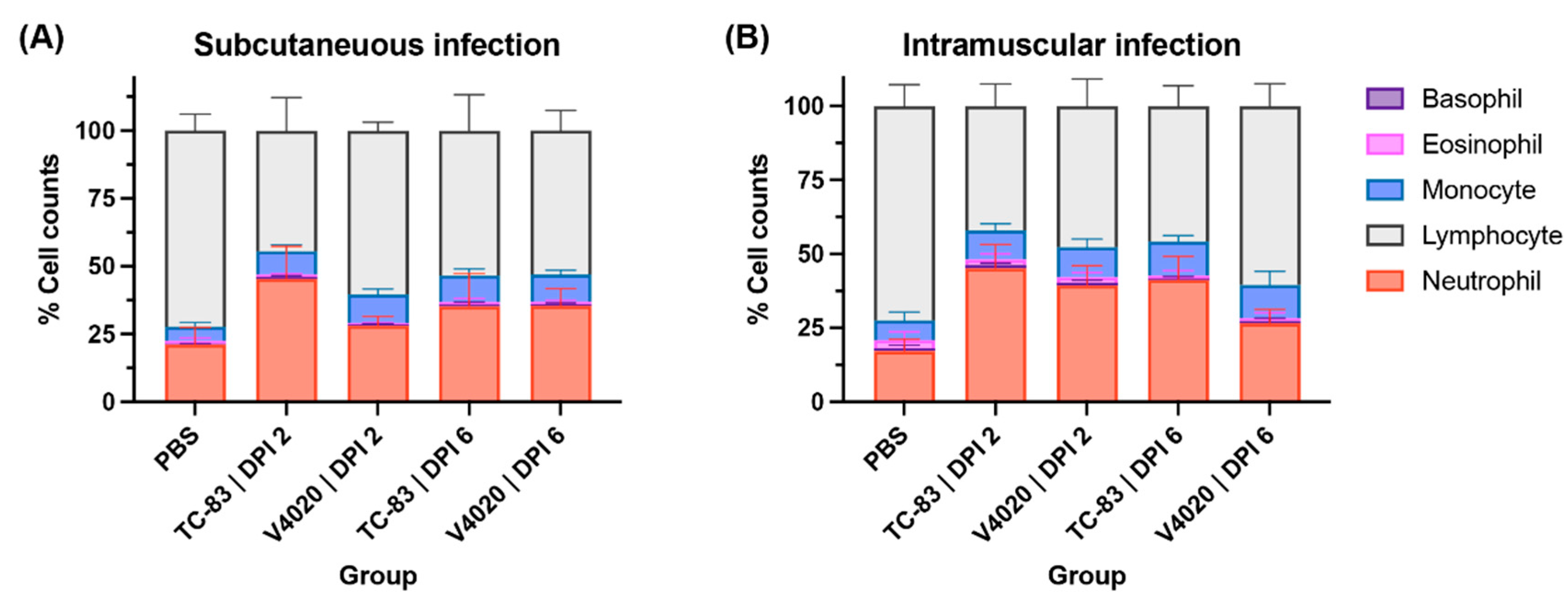

3.3. V4020 Induced a Lower Degree of Neutrophilia Than TC-83

To evaluate hematological reactions following the vaccination, total blood samples was subjected to blood cell counting analysis (

Figure 3), and the mock group harvested at DPI 5 was used as the baseline with a typical blood cell composition of approximately 21% of neutrophils and 72% of lymphocytes. The group vaccinated with VEEV TC-83 via the SC route (

Figure 3A) showed a significantly higher proportion of neutrophils (neutrophilia, approximately 45%) and a lower proportion of lymphocytes (lymphopenia, approximately 44%) at DPI 2. This observation indicates the animals have developed systematic inflammations (Two-Way ANOVA,

p < 0.0001 for neutrophils and lymphocytes compared to the mock group). The systemic inflammation decreased at DPI 6 compared to DPI 2; however, it remained higher than those of the mock group with a significantly higher proportion of neutrophils (neutrophilia, approximately 35%) and a lower proportion of lymphocytes (lymphopenia, approximately 53%) at DPI 6 (Two-Way ANOVA,

p < 0.0001 for neutrophils and lymphocytes compared to the mock group).

In contrast, the group vaccinated with V4020 through the SC route showed a non-significant increase in neutrophils (neutrophilia, approximately 28%) and a lower proportion of lymphocytes (lymphopenia, approximately 60%) at DPI 2 indicating a degree of systemic inflammations (Two-Way ANOVA, p = 0.088 and 0.0012 for neutrophils and lymphocytes, respectively). The systemic inflammation maintained at DPI 6 showing a significantly higher proportion of neutrophils (neutrophilia, approximately 35%) and a lower proportion of lymphocytes (lymphopenia, approximately 53%) at DPI 6 (Two-Way ANOVA, p < 0.0001 for neutrophils and lymphocytes compared to the mock group).

These findings were largely the same with the IM vaccinated groups with slight variations including the overall higher neutrophil counts. One noticeable difference from the SC study was that neutrophil counts for V4020 vaccine group were higher at DPI 2 (39%) than DPI6 (27%) for the IM vaccination group (

Figure 3B).

Overall, after SC or IM administration, both V4020 and TC-83 demonstrated increases in neutrophil counts, a sign of inflammation or infection. However, the extent of the inflammation from the V4020 was much less than that of TC-83-inoculated group, potentially indicating a lower degree of reactogenicity compared to TC-83 group.

3.4. Detection of Neuroinvasion in TC-83 Infected Mice

To evaluate the sign of neuroinvasion in the animals that received the test vaccines, the brains were harvested at DPI 2 and DPI 6, and the viral loads from four parts of the brain, namely the olfactory bulb, the cerebrum cortex, the spinal cord, and the cerebellum were enumerated. The mock-infected control group did not show any infectious virus in the CNS. For both TC-83 and V4020 infected groups, no infectious viruses were detected in the CNS at DPI 2 (data not shown). However, some animals that received TC-83 showed a detectable amount of virus in the CNS at DPI 6. Among the SC administration group, 50% (three out of six) brain samples showed infectious virus, two in the cerebral cortex and one the spinal cord (

Table 1). For the IM vaccination group (

Table 2), two out of six samples showed a detectable amount of virus in the brain. However, none of the brains from the V4020 administered mice showed any replicable virus, which highlights the lower risk of V4020 compared to TC-83.

Table 1.

Virus in the CNS after vaccine administration via. the SC route.

Table 1.

Virus in the CNS after vaccine administration via. the SC route.

| Inoculum |

Animal ID |

Sex |

DPI 6 |

| O.B. |

C.O. |

C.B. |

S.P. |

| TC-83 |

1 |

Female |

N.D. |

2.3E+06 |

1.6E+03 |

N.D. |

| 2 |

Female |

N.D. |

2.2E+03 |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| 3 |

Female |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| 4 |

Male |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| 5 |

Male |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

7.5E+02 |

| 6 |

Male |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| V4020 |

1 |

Female |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| 2 |

Female |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| 3 |

Female |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| 4 |

Male |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| 5 |

Male |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| 6 |

Male |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

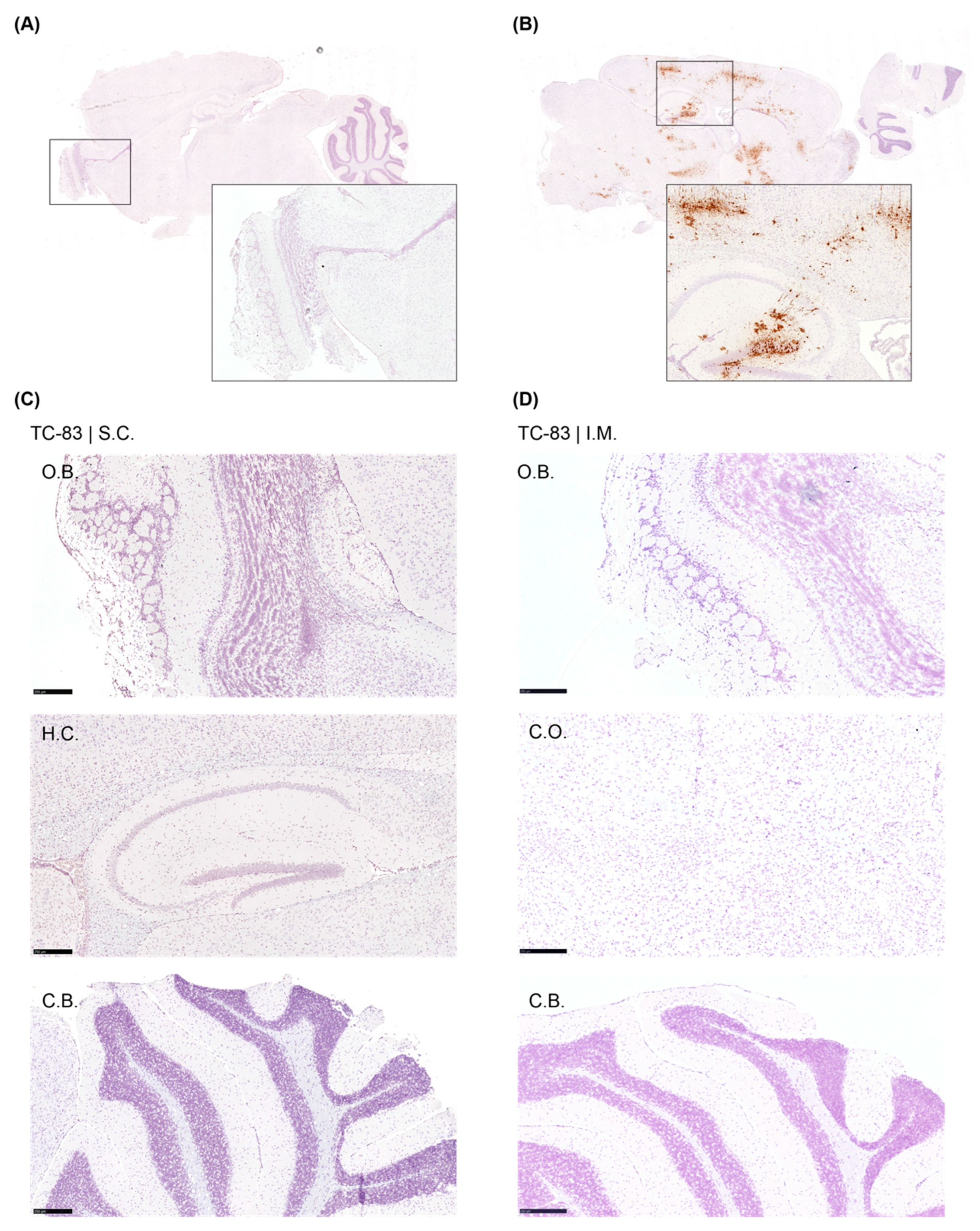

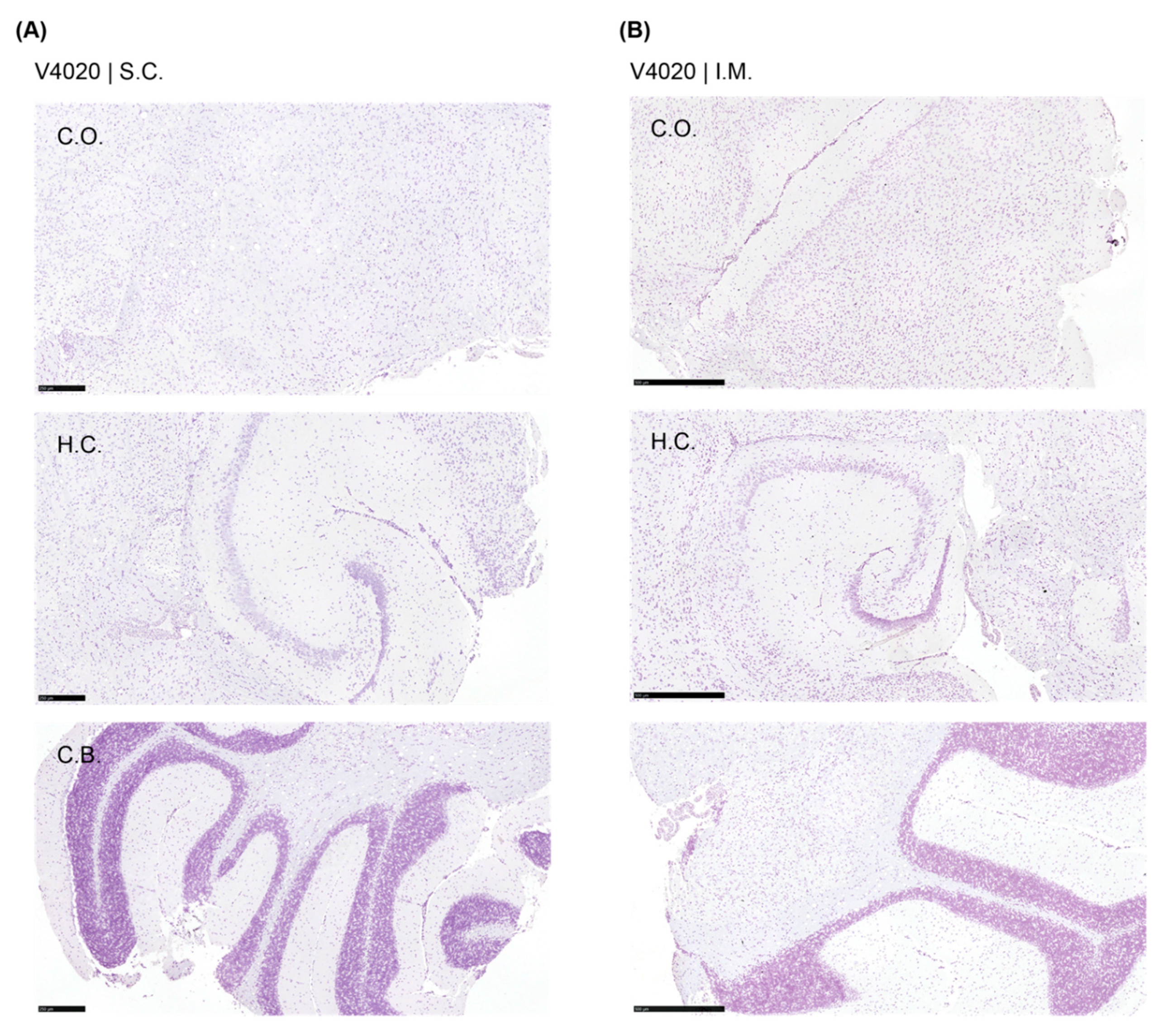

We employed the RNAScope assay to detect infectious, replicating virus with respect to location within the brain. As a positive control, brains from mice (strain C3H/Ne) intranasally infected with TC-83 were used (

Figure 4). The mock treated group did not show any VEEV-positive signal anywhere in the brain tissues, and the positive control samples showed strong positive signal for virus as expected. However, no VEEV-specific signal was detected from the brains of V4020 nor TC-83 vaccinated (

Figure 5).

3.5. Pseudoreversion of the Neuroinvasive TC-83 Population

To understand what changes in the viral genome could be associated with neuroinvasion of TC-83, we sequenced the genome of TC-83 virus isolated from the brains. Total cellular RNAs from Vero 76 cells infected with the samples were subjected to PCR-amplicon based sequencing (

Table 3). We found that all three isolates had two non-synonymous mutations: 1) E2 R120I, and 2) E1 V80A. The E2 R120I mutation was caused by a single mutation at nucleotide position 8922 G/T, of which the codon is responsible for the attenuation mutation of TC-83 (Arg120) compared to its processor, Trinadad Donkey strain (TrD, Thr120). Sequencing analysis of the inoculum samples of both TC-83 and V4020 did not detect these mutations (data not shown), indicating the mutation might be selected during the replication within the animals.

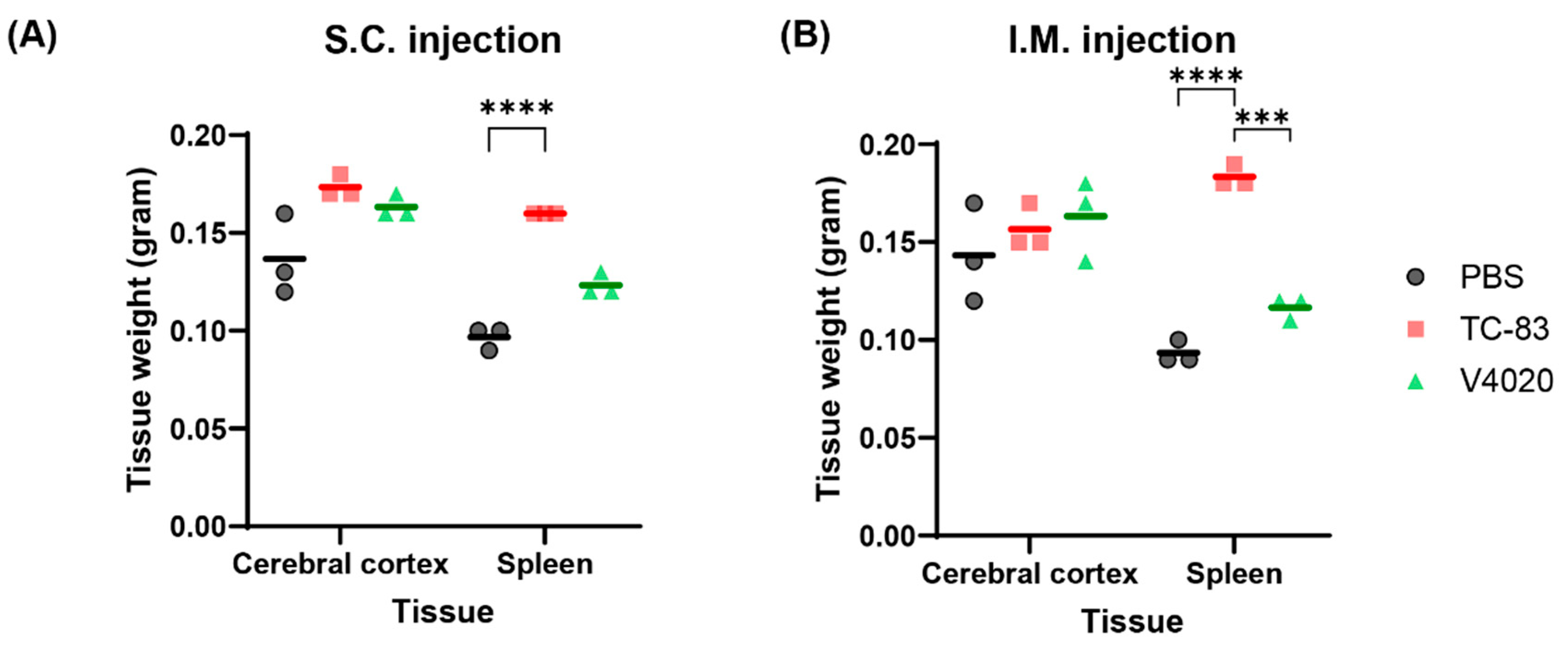

3.6. TC-83 and V4020 Did Not Induce Pathological Changes in the Brains and Other Organs

To evaluate if the vaccines could cause any pathogenic effect at the gross level, major organs were tested for macroscopic evaluation; no macroscopic pathology was noticed in the brain nor in the abdominal cavity in all the animals, and no signs of irritation (swelling, redness, etc.) were seen at the injection sites for both SC and IM injection groups (

Table 4). Clinical observation did not reveal any apparent abnormalities or changes in the size or appearance of major organs. Weight analysis of the brain (cerebral cortex) and spleen showed that the brain weight did not show any significant difference in any of the test groups compared to the mock group (

Figure 6). However, spleens from the TC83 and V4020 were larger than those from the mock group, with statistical significance between groups, although small group size (n=3) has limitations for statistical analysis. Interestingly, spleens from the TC-83 IM vaccinated group showed a higher weight compared to those from V4020, potentially indicating higher immunogenic activity by TC-83 than V4020.

To address concerns about potential neuroinvasion of vaccine, the right hemispheres of the brains were subjected to tissue histopathology. As a positive control, brains from mice intranasally infected with TC-83 were used. The intranasally infected TC-83 group showed a moderate degree of lesions in the meninges and cerebrum in all samples (n=10). For both TC-83 and V4020 vaccinated groups, however, no microscopic lesions were detected in any of the brain samples from either SC or IM administration routes groups (n=6). In conclusion, the legacy VEEV vaccine, VEEV TC-83, and the V4020 did not induce any tissue pathology in the brain after SC or IM injection, which are an intended route of injection.

4. Discussion

The potential of neuroinvasion by vaccine viruses is a critical area for understanding safety of live-attenuated vaccines for neurotropic viruses such as VEEV, although the minimum level of neuroinvasion may not necessarily indicate the safety of the vaccine. For example, previous research has shown that both virulent JEV and SA-14-14-2 vaccine can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [

21]. However, SA-14-14-2 vaccine for Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) has been approved in many countries with JEV endemicity. In China, it has been administered safely and effectively to millions of children as young as 8 months of age since 1988 [

22]. Additionally, the SA-14-14-2 vaccine is approved in Australia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand to protect public from JEV infections. The vaccine strain crosses the BBB much less efficiently than virulent strains, and this indicates that while vaccine strains may have some level of neuroinvasion, they are generally accepted as safe with much less neuroinvasive compared to their virulent counterparts.

In this study, we evaluated the neuroinvasion potential of V4020, a TC-83 based VEEV vaccine with a rationally designed strategy for attenuation as well as for prevention for potential reversion. We employed immunocompetent mice with a vaccine dose of 2x106 PFU, a 20-fold higher than the expected 105 PFU vaccination dose either SC or IM, the intended routes of administration for the V4020 vaccine. We compared the neuroinvasion potential and any adverse effects to TC-83, the legacy VEEV vaccine strain as its comparator. Overall, our study found that adverse effects from V4020 vaccination were significantly lower compared to the comparator VEEV TC-83 based on the clinical scores and blood cell counts.

Importantly, we found that live TC-83 vaccine virus can establish a CNS-infection at a rather significant rate (30-50% frequency) after SC or IM administration in mice. While neuroinvasion of virulent VEEV after peripheral route infection is well-documented, to the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have shown neuroinvasion of TC-83 following peripheral infection in adult mice other than intranasal infection. While our finding could be due to the high amount of virus inoculum (2 x 10

6 PFU per dose per mouse, 20-fold higher than the expected vaccine dose), this observation of the neuroinvasion by TC-83 vaccine is in line with the clinical observations with the TC-83 vaccine in humans, as it was used as part of Special Immunization Programs to vaccinate medical workers at risk of VEEV infection. Up to 20% of TC-83 vaccine recipients experienced adverse reactions including mild to medium neurological symptoms [

8,

9,

10].

TC-83 virus recovered from the CNS (i.e., neurotropic TC-83) harbored two unique mutations in E2 and E1 genes which play critical roles in virus-receptor interaction. The mutations, particularly E2 R102I mutation, we found from TC-83 virus recovered from the CNS (i.e., neurotropic TC-83) were of special interest. The R120 residue is well-known to confer attenuation compared to its virulent parental strain, TrD, which encodes Thr [

23]. The T120R mutation in TC-83, a change from a neutral to a positive charge amino acid, is likely to promote the binding with heparin sulfate in cell cultures and to decrease with its putative receptor

in vivo [

24,

25,

26]. Interestingly, the neurotropic TC-83 population encoded R102I mutation, which is not a true reversion as the Arg residue has changed to Ile, not Thr. We believe that this change is a pseudoreversion, restoring the phenotype lost by changing the residue to a neutral amino acid (

Figure 7). However, we did not validate this pseudoreversion is the key factor to regain the neuroinvasion activity of TC-83 due to the dual-use concern because such an introduction to TC-83 might be a gain-of-function for an existing vaccine.

In contrast, the lack of detectable neuroinvasion by V4020 suggests a higher safety profile of V4020 in regard to neuroinvasion potential. While we cannot directly conclude, this lack of neuroinvasion of V4020 is presumably due to the fact that the codon for E2-R120 was engineered to the CGA codon, which requires a double mutation for the first two positions of the codon for reversion. A previous study analyzing virus population sequence V4020 RNA showed that no SNPs of 1% or higher frequency were detected at each nucleotide of the codon, suggesting a low probability of a reversion or a pseudoreversion.

Alternatively, this lack of neuroinvasion could be because of the lower V4020 viremia titer in the circulation for the higher level of attenuation of V4020, as compared to TC-83 virus, as higher viremia could increase the chance of neuroinvasion from circulation. After SC inoculation, virulent VEEV reaches viremia 10

5-10

7 PFU/mL in the serum, while viremia for attenuated variants varies from the undetectable to rarely detectable depending on the attenuating mutation [

11]. Attenuating rearrangement of the capsid and glycoproteins in V4020 would have contributed to the decrease, if any, in viral load in the blood.

Although we detected virus in the brain following the vaccination with TC-83, we did not find pathological outcomes nor RNA detection by RNAScope assay at the histopathology level. This lack of consistency could be due to the nature of the approach utilizing a small section of the tissue, rather than the entire brain as virus isolation. Another explanation is the premature development of neuropathology, as the neuroinvasion could have happened at a later time point.

Another important consideration is the vaccine virus population diversity, as was shown for other live-attenuated vaccines. For example, yellow fever virus (YFV) vaccine YF-17D is safely used worldwide to prevent infections with YFV. However, small percent, 0.000012–0.00002% of vaccinated patients can develop post-vaccination neurological syndrome. Next generation sequencing (NGS) studies of YF-17D variant have identified several neuroinvasive genetic variants in the vaccine virus population. It was concluded that viral population diversity is a critical factor for YFV vaccine neuroinvasiveness [

27]. Our NGS studies to compare experimental Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) vaccines revealed that the vaccine virus derived from infectious clone has fewer variations at attenuating sites, when compared to classic CHIKV vaccine derived by multiple passages [

28]. Likewise, TC-83 vaccine virus has been generated by multiple passages in tissue culture. In contrast, V4020 was derived from iDNA infectious clone and may have fewer genetic variants as compared to TC-83 vaccine [

13,

14].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, while the legacy VEEV vaccine TC-83 poses neuroinvasion potential via a pseudoreversion, our study establishes the experimental V4020 vaccine as a safer alternative vaccine candidate with advantageous safety features including reduced or no neuroinvasion risk.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Figure S1: Genomic structure of TC-83 and V4020 compared to the wildtype strain, TrD; Supplementary Table: Sequences of primers used for the study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C. and P.P.; methodology, D.C.; validation, D.C. and P.P. ; formal analysis, D.C.; data curation, I.T., A.C., A.P., K.B., and D.C.; writing—original draft preparation, P.P. and D.C.; writing—review and editing, P.P., I.T., K.B., and D.C.; visualization, D.C.; supervision, D.C.; project administration, D.C.; funding acquisition, P.P. and I.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by NIH NIAID, grant number AI155406.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Louisville (IACUC 22221, approval date 02/14/2023) for studies involving animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank USAMRIID for supplying TC-83 vaccine, the Iowa State University Vet Med Pathology for microscopic pathology service and University of Louisville RBL for hematology analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

I.T. and P.P. are employees and stakeholders at Medigen, Inc., declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VEEV |

Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus |

| CNS |

Central nervious system |

| IM |

Intramuscular |

| SC |

Subcutaneous |

| IN |

Intranasal |

References

- Paessler S, Weaver SC. Vaccines for Venezuelan equine encephalitis. Vaccine. 2009;27 Suppl 4:D80-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zacks MA, Paessler S. Encephalitic alphaviruses. Vet Microbiol. 2010;140(3-4):281-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aguilar PV, Estrada-Franco JG, Navarro-Lopez R, Ferro C, Haddow AD, Weaver SC. Endemic Venezuelan equine encephalitis in the Americas: hidden under the dengue umbrella. Future Virol. 2011;6(6):721-40. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Samy AM, Elaagip AH, Kenawy MA, Ayres CF, Peterson AT, Soliman DE. Climate Change Influences on the Global Potential Distribution of the Mosquito Culex quinquefasciatus, Vector of West Nile Virus and Lymphatic Filariasis. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0163863. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dietz WH, Jr., Peralta PH, Johnson KM. Ten clinical cases of human infection with venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis virus, subtype I-D. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1979;28(2):329-34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusnak JM, Dupuy LC, Niemuth NA, Glenn AM, Ward LA. Comparison of Aerosol- and Percutaneous-acquired Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis in Humans and Nonhuman Primates for Suitability in Predicting Clinical Efficacy under the Animal Rule. Comp Med. 2018;68(5):380-95. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sulkin SE. Laboratory-acquired infections. Bacteriol Rev. 1961;25(3):203-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pittman PR, Makuch RS, Mangiafico JA, Cannon TL, Gibbs PH, Peters CJ. Long-term duration of detectable neutralizing antibodies after administration of live-attenuated VEE vaccine and following booster vaccination with inactivated VEE vaccine. Vaccine. 1996;14(4):337-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin SS, Bakken RR, Lind CM, Garcia P, Jenkins E, Glass PJ, et al. Evaluation of formalin inactivated V3526 virus with adjuvant as a next generation vaccine candidate for Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus. Vaccine. 2010;28(18):3143-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tretyakova I, Lukashevich IS, Glass P, Wang E, Weaver S, Pushko P. Novel vaccine against Venezuelan equine encephalitis combines advantages of DNA immunization and a live attenuated vaccine. Vaccine. 2013;31(7):1019-25. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Grieder FB, Davis NL, Aronson JF, Charles PC, Sellon DC, Suzuki K, et al. Specific restrictions in the progression of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus-induced disease resulting from single amino acid changes in the glycoproteins. Virology. 1995;206(2):994-1006. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alejandro B, Kim EJ, Hwang JY, Park JW, Smith M, Chung D. Genetic and phenotypic changes to Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus following treatment with beta-D-N4-hydroxycytidine, an RNA mutagen. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):25265. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tretyakova I, Plante KS, Rossi SL, Lawrence WS, Peel JE, Gudjohnsen S, et al. Venezuelan equine encephalitis vaccine with rearranged genome resists reversion and protects non-human primates from viremia after aerosol challenge. Vaccine. 2020;38(17):3378-86. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tretyakova I, Tibbens A, Jokinen JD, Johnson DM, Lukashevich IS, Pushko P. Novel DNA-launched Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus vaccine with rearranged genome. Vaccine. 2019;37(25):3317-25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tretyakova I, Tomai M, Vasilakos J, Pushko P. Live-Attenuated VEEV Vaccine Delivered by iDNA Using Microneedles Is Immunogenic in Rabbits. Front Trop Dis. 2022;3. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pushko P, Lukashevich IS, Johnson DM, Tretyakova I. Single-Dose Immunogenic DNA Vaccines Coding for Live-Attenuated Alpha- and Flaviviruses. Viruses. 2024;16(3). [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pushko P, Lukashevich IS, Weaver SC, Tretyakova I. DNA-launched live-attenuated vaccines for biodefense applications. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2016;15(9):1223-34. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Julander JG, Bowen RA, Rao JR, Day C, Shafer K, Smee DF, et al. Treatment of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus infection with (-)-carbodine. Antiviral Res. 2008;80(3):309-15. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(18):3094-100. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khou C, Diaz-Salinas MA, da Costa A, Prehaud C, Jeannin P, Afonso PV, et al. Comparative analysis of neuroinvasion by Japanese encephalitis virulent and vaccine viral strains in an in vitro model of human blood-brain barrier. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0252595. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ginsburg AS, Meghani A, Halstead SB, Yaich M. Use of the live attenuated Japanese Encephalitis vaccine SA 14-14-2 in children: A review of safety and tolerability studies. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(10):2222-31. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kinney RM, Chang GJ, Tsuchiya KR, Sneider JM, Roehrig JT, Woodward TM, et al. Attenuation of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus strain TC-83 is encoded by the 5'-noncoding region and the E2 envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 1993;67(3):1269-77. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Klimstra WB, Ryman KD, Johnston RE. Adaptation of Sindbis virus to BHK cells selects for use of heparan sulfate as an attachment receptor. J Virol. 1998;72(9):7357-66. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Byrnes AP, Griffin DE. Large-plaque mutants of Sindbis virus show reduced binding to heparan sulfate, heightened viremia, and slower clearance from the circulation. J Virol. 2000;74(2):644-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang R, Hryc CF, Cong Y, Liu X, Jakana J, Gorchakov R, et al. 4.4 A cryo-EM structure of an enveloped alphavirus Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus. EMBO J. 2011;30(18):3854-63. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bakoa F, Prehaud C, Beauclair G, Chazal M, Mantel N, Lafon M, et al. Genomic diversity contributes to the neuroinvasiveness of the Yellow fever French neurotropic vaccine. NPJ Vaccines. 2021;6(1):64. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hidajat R, Nickols B, Forrester N, Tretyakova I, Weaver S, Pushko P. Next generation sequencing of DNA-launched Chikungunya vaccine virus. Virology. 2016;490:83-90. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).