1. Introduction

Fairness in Machine Learning (ML) has been one of the most debated concepts, particularly in an era where numerous ML models exist, and their applications are increasingly pervasive [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The rise of ML in critical decision-making processes necessitates a closer examination of how these models perform across different demographics and classes to ensure equitable outcomes. Fairness in ML refers to the absence of any prejudice or favoritism toward an individual or group based on their inherent or acquired characteristics. This concern has gained prominence as biased models can perpetuate and even amplify societal biases, leading to unfair treatment of marginalized groups.

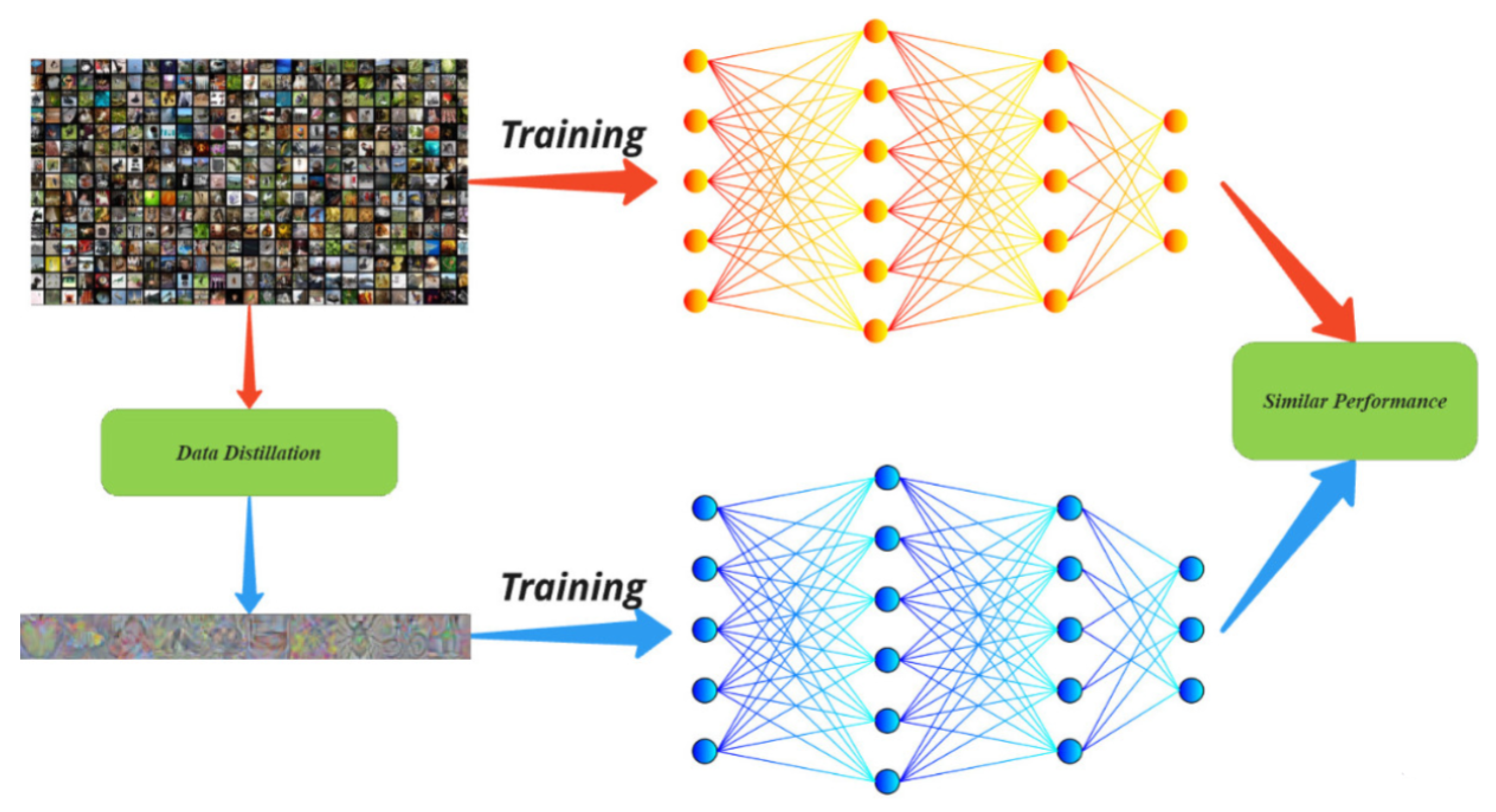

This paper aims to assess the impact of dataset distillation on the class-wise fairness of models trained on distilled data. Class-wise fairness refers to a model’s ability to treat all classes equally. Dataset distillation [

6,

7,

8,

9], as illustrated in

Figure 1, synthesizes smaller datasets that preserve the essential information from larger ones. It generates a compact synthetic dataset capturing the most informative aspects of the original data, thereby reducing the computational resources needed for training. This technique is particularly beneficial in minimizing the computational burden associated with training machine learning models on extensive datasets—a capability that may challenge the emerging research direction of applying quantum-ML techniques to tackle such complexity [

10,

11]—thus improving overall efficiency. However, it is crucial to investigate how this reduction process influences the inherent biases in the data and how it subsequently affects the fairness of the trained models.

Specifically, this work employs the state-of-the-art Dataset Distillation by Matching Training Trajectories (MTT) method [

12] and compares results across different distilled dataset sizes, quantified in terms of the number of images per class (IPC). The MTT method focuses on matching the training trajectories of the original and distilled datasets to ensure that the distilled dataset captures the dynamics of the full training process. This method involves a complex optimization process that aims to create a distilled dataset by aligning the gradient trajectories of the distilled dataset’s training with those of the original dataset.

Our study will undertake a comprehensive experimental analysis, focusing on evaluating the trade-offs between high model performance and fairness. By systematically varying the Instances Per Class (IPC), we aim to uncover patterns that highlight the optimal balance between dataset size, model accuracy, and fairness. The experiments will involve training models on distilled datasets with varying IPC values, followed by a rigorous assessment of both their performance and fairness metrics. To ensure the robustness and generalizability of our findings, we will employ a diverse array of datasets and model architectures in the analysis.

Our findings will provide valuable insights for ML practitioners and researchers, guiding them in choosing appropriate dataset sizes and distillation techniques that do not compromise on fairness while optimizing for efficiency. This research contributes to the ongoing discourse on ethical AI by highlighting the importance of fairness in model training processes and offering practical recommendations for mitigating biases through careful dataset management. The implications of this study are significant for real-world applications where both fairness and efficiency are critical considerations. By understanding the impact of data distillation on fairness, we can develop more ethical and reliable ML models that serve all segments of society equitably.

1.1. Contribution of the Paper

This paper introduces several novel contributions to the study of fairness in Machine Learning:

First-of-its-Kind Analysis of Fairness in Dataset Distillation: This study is among the first to systematically examine how the process of dataset distillation impacts fairness in ML models. By focusing on this unexplored area, the paper addresses a critical gap in current research.

Application of the MTT Method for Fairness: The research uniquely applies the state-of-the-art Dataset Distillation by Matching Training Trajectories (MTT) method to assess its effectiveness in preserving fairness across different dataset sizes, offering new insights into the method’s utility beyond traditional performance metrics.

Innovative Trade-off Analysis: The paper provides a novel analysis of the trade-offs between fairness and accuracy, using multiple fairness metrics to deliver a comprehensive understanding of how these two crucial factors interact during the distillation process.

New Insights on Dataset Size: By varying the number of images per class (IPC) in distilled datasets, the study uncovers new patterns and offers practical recommendations on how dataset size affects fairness and model performance, contributing valuable guidance for future applications.

Advancing Ethical AI: The findings push the boundaries of ethical AI practices by offering novel strategies to mitigate bias in ML models, ensuring that they remain both efficient and fair, particularly in real-world applications.

This paper provides insights into maintaining fairness while optimizing dataset distillation, marking a significant advancement in the field.

In this paper, the structure will be as follows:

Section II presents the background of this work. It begins with a review of related work, followed by an explanation of the MTT method. Subsequently, the ConvNet and AlexNet architectures will be described. Section III details the experimental setup. Section IV presents distilled data samples. Section V discusses the results. Finally, Section VI presents the conclusion.

2. Background

2.1. Related Work

The first studies on Dataset Distillation produced distilled data by matching the performance of a model trained on the distilled data with the performance of a model trained on the original data [

6,

24,

27,

30]. These methods often focused on optimizing the distilled dataset to retain the same accuracy or loss metrics as achieved with the original dataset.

Later approaches introduced more sophisticated techniques to improve the quality of distilled datasets. Gradient matching methods [

20,

22,

29] aimed to align the gradients of the loss function with respect to the model parameters for both the distilled and original datasets. This approach ensures that the distilled dataset encapsulates the learning dynamics of the full dataset, leading to more effective training. Distribution matching methods [

21,

23,

25] took a different approach by focusing on matching the data distributions. These methods ensure that the statistical properties of the distilled dataset are consistent with those of the original dataset, which can lead to better generalization performance on unseen data.

Training trajectory matching methods [

12,

26] further refined the distillation process by aligning the training trajectories of the original and distilled datasets. These methods optimize the distilled dataset to replicate the sequence of parameter updates (gradient trajectories) that would occur when training on the original dataset. MTT [

12] represents the current state-of-the-art in non-factorization approaches, achieving superior performance by focusing on this alignment.

Data factorization methods [

28] provide another approach by factorizing the dataset into smaller components, which are then used to reconstruct the dataset during training. These methods aim to reduce the dataset size while retaining critical information for model training. The large-scale use of distilled datasets can significantly impact important decisions, thus it is crucial to preserve privacy and fairness [

33]. Studies such as [

16] and [

31] have evaluated the class-wise fairness of models trained on datasets distilled with Model Matching [

6] on text datasets. Their results indicate that distillation can amplify the biases learned from the original data. Additionally, [

17] conducted a comprehensive experiment similar to ours but focused primarily on performance comparison between distilled and original datasets, without assessing the effect of the number of images per class (IPC) on fairness.

While early dataset distillation methods focused on matching model performance, subsequent advancements have introduced techniques like gradient matching, distribution matching, training trajectory matching, and data factorization to enhance the efficacy of distilled datasets. However, these distilled datasets must also be evaluated for fairness and privacy implications to ensure their responsible use in practical applications.

2.2. Matching Training Trajectories

Model Trajectory Matching (MTT) is a sophisticated dataset distillation method designed to ensure that the distilled dataset captures the dynamics of the full training process [

34,

35,

36,

37]. This method involves several mathematical components that work together to achieve this goal.

First, consider the parameters of a neural network, denoted as

. The update of these parameters during training is governed by the gradient descent rule:

where

is the learning rate,

is the loss function, and

D is the dataset.

Let

represent the original dataset, and

represent the distilled dataset. The goal of MTT is to ensure that the gradient trajectory when training on

matches that of

. Define the gradient at step

t for the original and distilled datasets as:

and

respectively. The objective is to minimize the difference between these gradients over the training trajectory:

where

T is the total number of training steps.

This optimization problem aims to minimize the squared -norm of the difference between the gradients of the original and distilled datasets. By doing so, MTT ensures that the updates to the parameters when training on are as similar as possible to those when training on .

The distilled dataset

is updated iteratively to better match the gradient trajectories. At each iteration

k, the distilled dataset is refined through:

where

is the learning rate for updating the distilled dataset. This involves computing the gradient of the loss difference with respect to the distilled dataset and making iterative adjustments to minimize this difference.

To provide further mathematical insight, consider the gradient matching loss function:

The gradient of this loss with respect to the distilled dataset

is given by:

where

is the gradient of the distilled dataset’s gradient with respect to the dataset itself. This term captures the influence of the distilled dataset on the gradient trajectories.

Finally, the distilled dataset is used to train the neural network, and its performance is evaluated based on metrics such as accuracy and loss. This evaluation ensures that the distilled dataset maintains the efficacy of the original dataset. The process can be summarized in the following steps:

|

Algorithm 1 MTT Algorithm |

- 1:

Initialize randomly - 2:

for each iteration k do

- 3:

Compute for

- 4:

Compute for

- 5:

Update using the gradient of the matching loss: - 6:

- 7:

end for - 8:

Train the model on the updated

- 9:

Evaluate the performance of the model |

MTT involves a detailed mathematical process that focuses on aligning the gradient trajectories of the distilled dataset with those of the original dataset. This alignment ensures that the distilled dataset captures the essential training dynamics, allowing for effective training of neural networks with significantly fewer data samples.

3. Experiment Setup

In our research, we aimed to test a specific hypothesis through a series of meticulously designed experiments. Our primary objective was to investigate the performance of various classifiers on the CIFAR-10 dataset while examining the effects of data distillation on classifier accuracy and variance. The experimental setup is detailed as follows:

Initially, we concentrated on training ten classifiers for each setting of images per class (IPC) using the CIFAR-10 dataset. The CIFAR-10 dataset consists of 60,000 color images of dimensions 32x32 pixels, evenly distributed across ten categories, with each class containing 6,000 images [

38,

39]. The dataset is partitioned into 50,000 images for training and 10,000 images for testing, providing a well-defined framework for evaluating classifier performance. CIFAR-10 was chosen for its relatively simpler structure and smaller class set, making it ideal for initial experimentation with data distillation techniques and allowing us to quickly assess model behavior.

Subsequently, we extended our analysis to the CIFAR-100 dataset, which presents a more complex challenge due to its 100 distinct categories. Like CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100 comprises a total of 60,000 32x32 pixel color images; however, each class in CIFAR-100 contains only 600 images [

48]. This finer categorization increases the difficulty of classification tasks, as the model must distinguish between a larger number of classes with significantly fewer training samples available per class. The dataset is similarly split into 50,000 images for training and 10,000 images for testing.

CIFAR-100 was selected to explore the scalability of our findings from CIFAR-10 to a more challenging scenario. The dataset’s hierarchical structure, comprising 20 superclasses each containing five subclasses, not only enriches its diversity but also compels classifiers to develop nuanced representations that can effectively capture the distinctions among similar classes [

41,

42]. This characteristic is particularly pertinent for evaluating the robustness of data distillation techniques, as they may have varying impacts on model performance and fairness when applied to more complex datasets.

By employing both CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets in our experiments, we aimed to provide a comprehensive evaluation of classifier performance across varying levels of data complexity and class granularity, ensuring that our findings would be relevant and applicable to a broad range of machine learning applications.

Following this preliminary analysis, we proceeded to employ various classifiers and established a rigorous training and evaluation process, as outlined below:

Classifiers: We employed two different neural network architectures, ConvNet [

45,

46,

47] and AlexNet [

40,

43,

44], for this experiment. Both architectures were trained with identical hyperparameters as described in [

12].

Training: Each classifier was trained for a fixed number of epochs using stochastic gradient descent (SGD) with momentum. The learning rate, batch size, and other hyperparameters were kept consistent across all training sessions.

Evaluation: Post-training, we evaluated the classifiers on the test set. The primary metrics recorded were the average accuracy per class and the variance in accuracies across different classes. This provided us with a baseline set of data comprising average accuracy and variance metrics.

Subsequently, we employed data distillation techniques to generate new training datasets. Data distillation aims to condense the information from the original dataset into a smaller synthetic dataset while retaining its predictive power.

Distillation Process: We generated ten new datasets for each Image Per Class (IPC) value for both CIFAR-10 (IPC values: 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30) and CIFAR-100 (IPC values: 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35), following the method in [

12]. Multiple datasets per IPC ensure statistical reliability, reducing the influence of outliers. The IPC values span a broad range to capture performance across varying dataset sizes.

Classifier Training: Ten classifiers were trained per distilled dataset: ConvNet and AlexNet for CIFAR-10, and ConvNet for CIFAR-100. The training setup, including hyperparameters, was consistent with baseline configurations. Training multiple models helps ensure robust performance estimates, while using different architectures for CIFAR-10 allows comparison across model types. A single architecture for CIFAR-100 ensures focus on this more complex dataset.

Evaluation: We recorded the average accuracy per class and the variance between these accuracies, noting differential performance across classes. Tracking average accuracy and variance allows us to assess both overall performance and consistency across classes, ensuring balanced and fair model behavior.

For each IPC scenario, we averaged the results across 100 models. This was achieved by training ten classifiers on each of the ten distinct distilled datasets per IPC value. The averaging process helped mitigate the effects of any anomalies or outliers, thereby providing a more robust estimate of model performance. Finally, a comparative analysis was conducted to understand the impact of data distillation on classifier performance. We compared the average accuracies and variances of classifiers trained on the distilled datasets with those trained on the original dataset. This analysis offered insights into how data distillation affects model performance, particularly regarding accuracy consistency across different classes.

To ensure the reproducibility of our experiments and the consistency of results, all experiments were conducted with fixed random seeds for dataset generation and model initialization. Additionally, the entire process was automated using scripts to minimize human errors and biases. This meticulous setup allowed us to rigorously evaluate the impact of data distillation on classifier performance and provide reliable insights into the potential benefits and limitations of this approach.

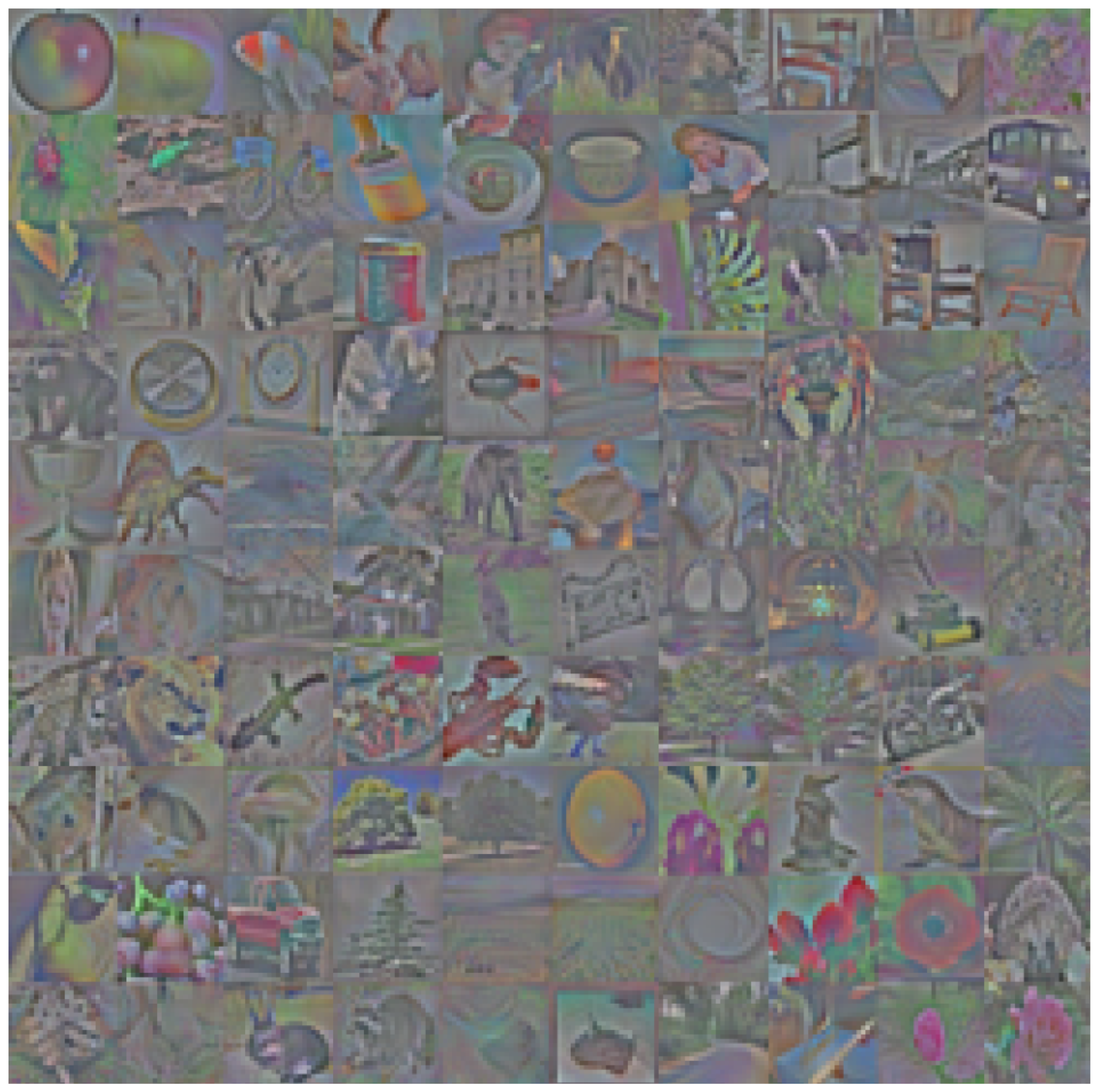

As a visual aid, we present the distilled dataset at IPC values of 1, 5, and 10. The figure shows the entire dataset in each case, as dataset distillation reduces the original dataset to such a small size. We display the synthesized images used for training. The images from CIFAR-100 at different IPCs and are shown in

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4. It can be observed that the 1-image-per-class samples are more abstract yet information-dense, while the 5-image-per-class samples exhibit more structure, with further refinement as the IPC increases to 10.

4. Results

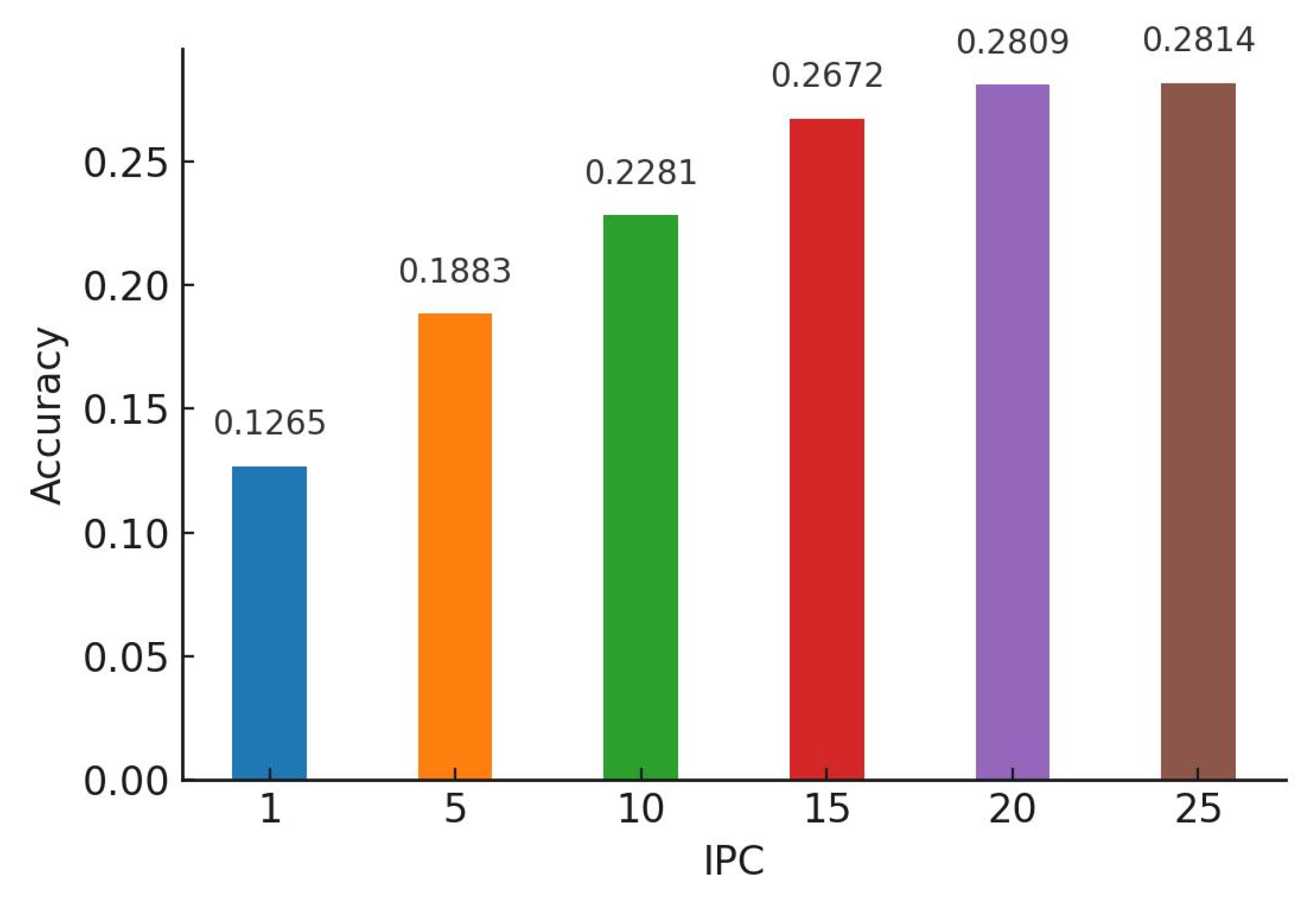

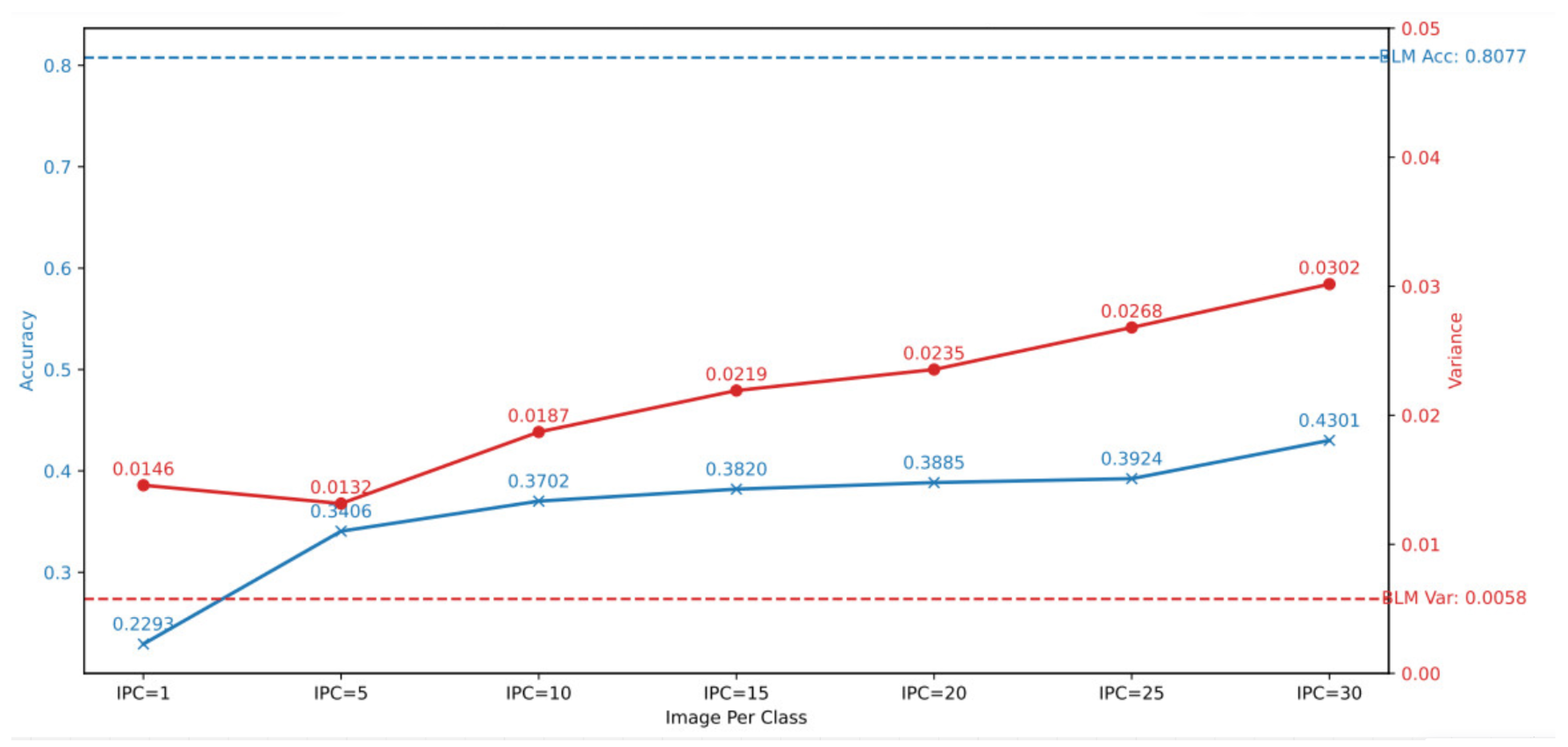

In our study, we conducted a comparative analysis of the accuracy between models trained on distilled datasets (DDM) and those trained on the baseline model (BLM). Consistent with existing literature, our findings indicated that the utilization of DDMs generally results in a decrease in overall accuracy alongside an increase in bias. However, a more nuanced insight emerged from our detailed examination: as the size of the distilled dataset increased, model accuracy exhibited a corresponding improvement. This enhancement, however, is accompanied by a trade-off—heightened variance in accuracy across different classes.

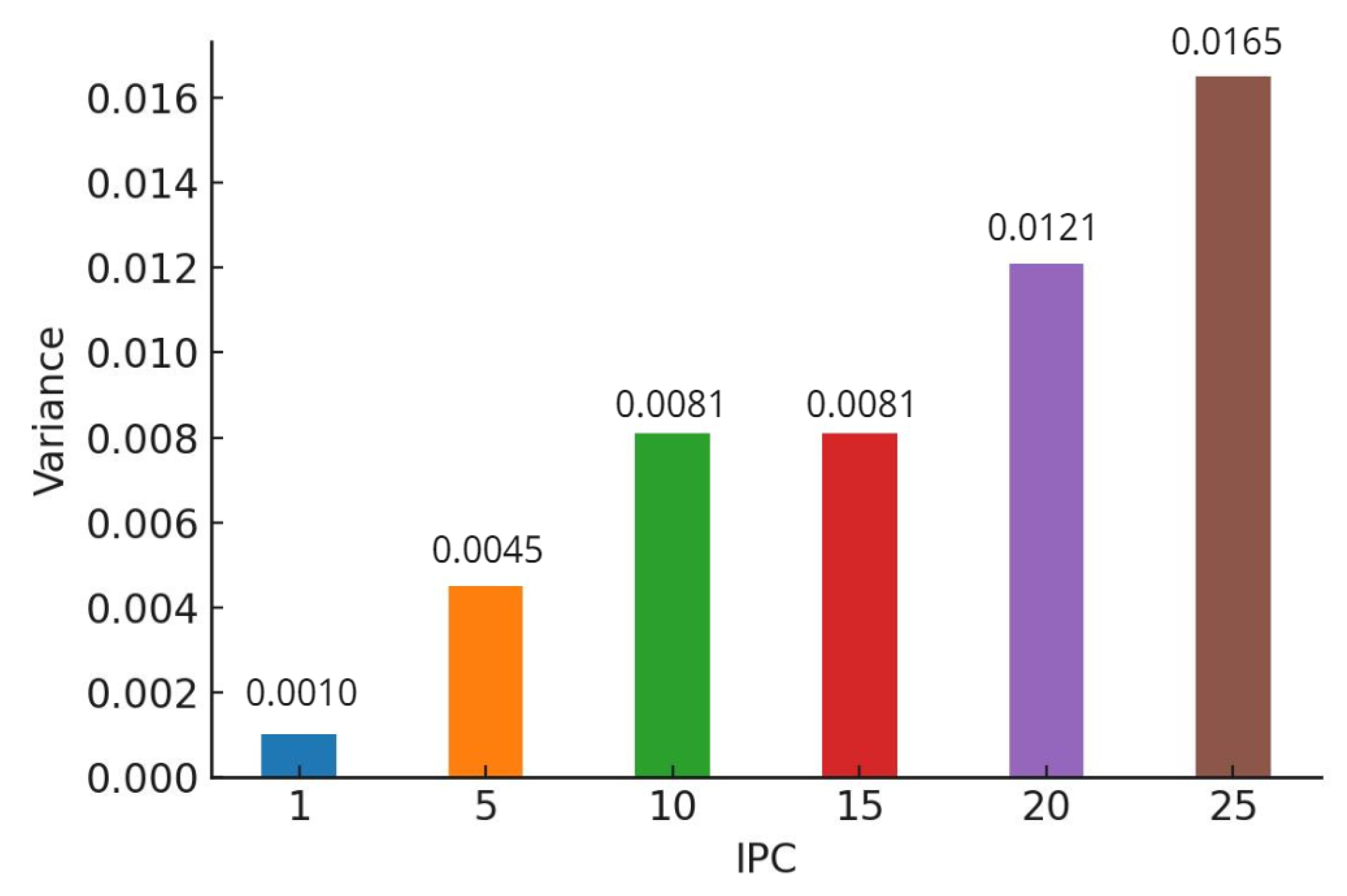

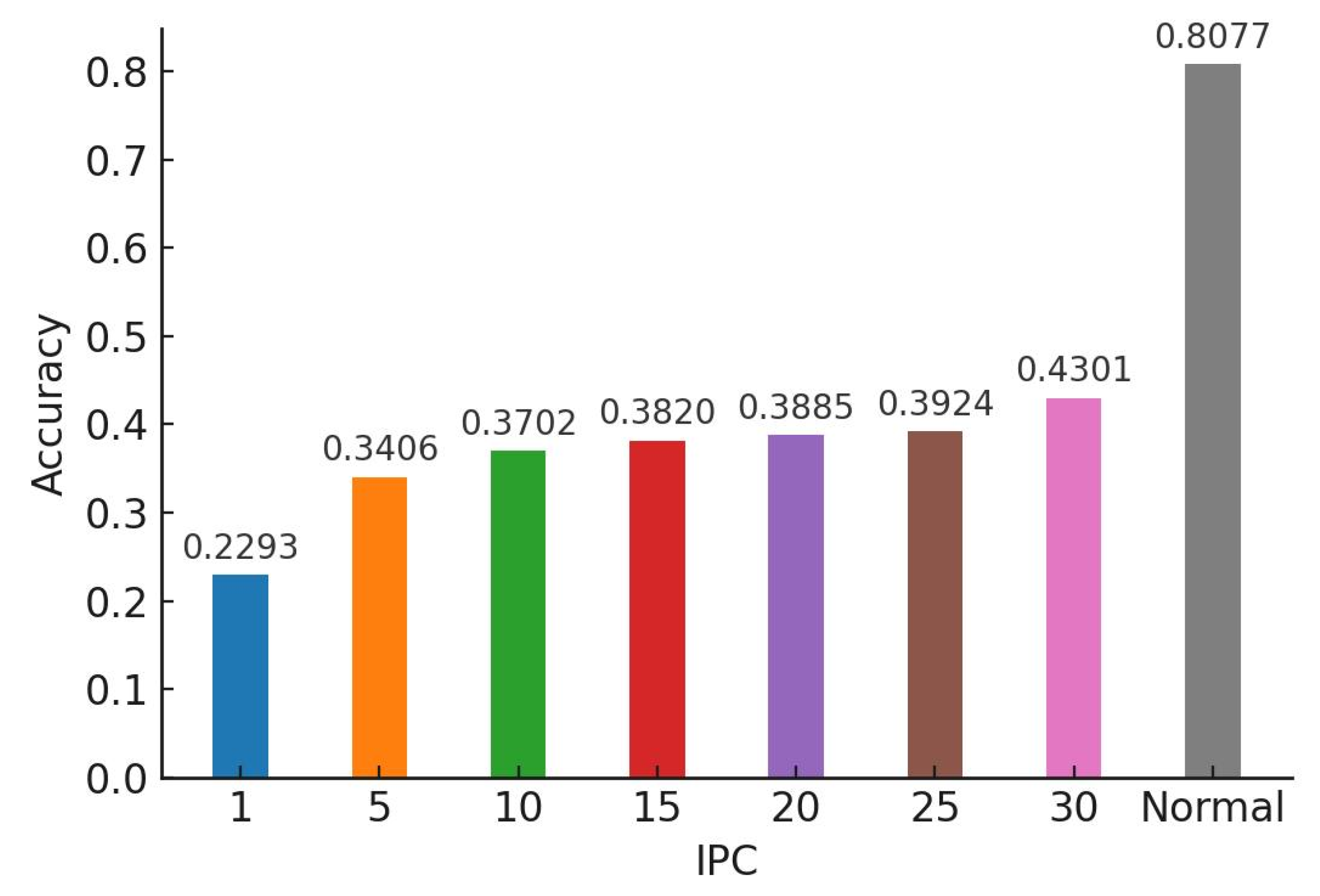

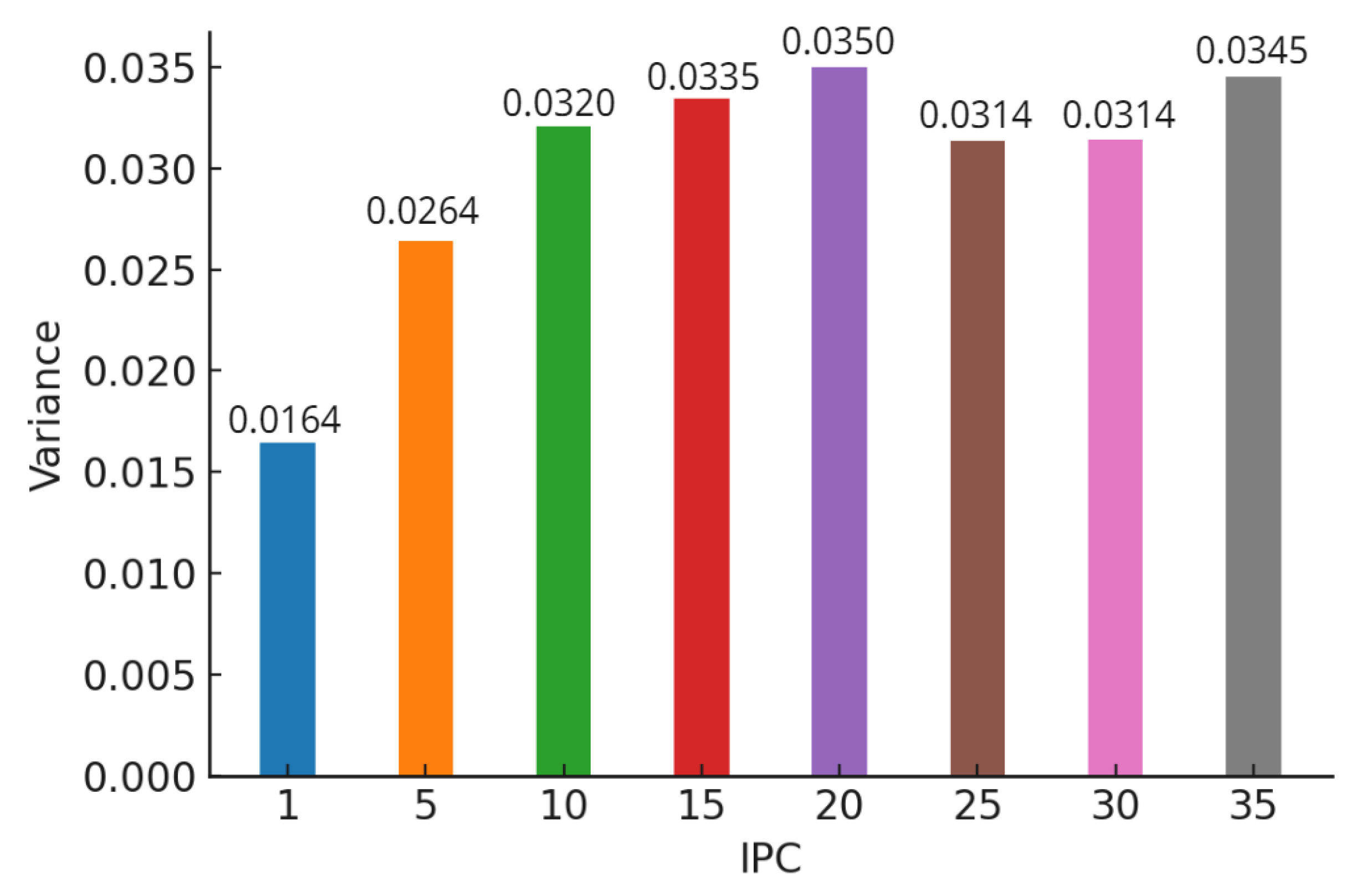

This pattern of results was consistent across various classification models, including AlexNet for CIFAR-10 (

Figure 5 and

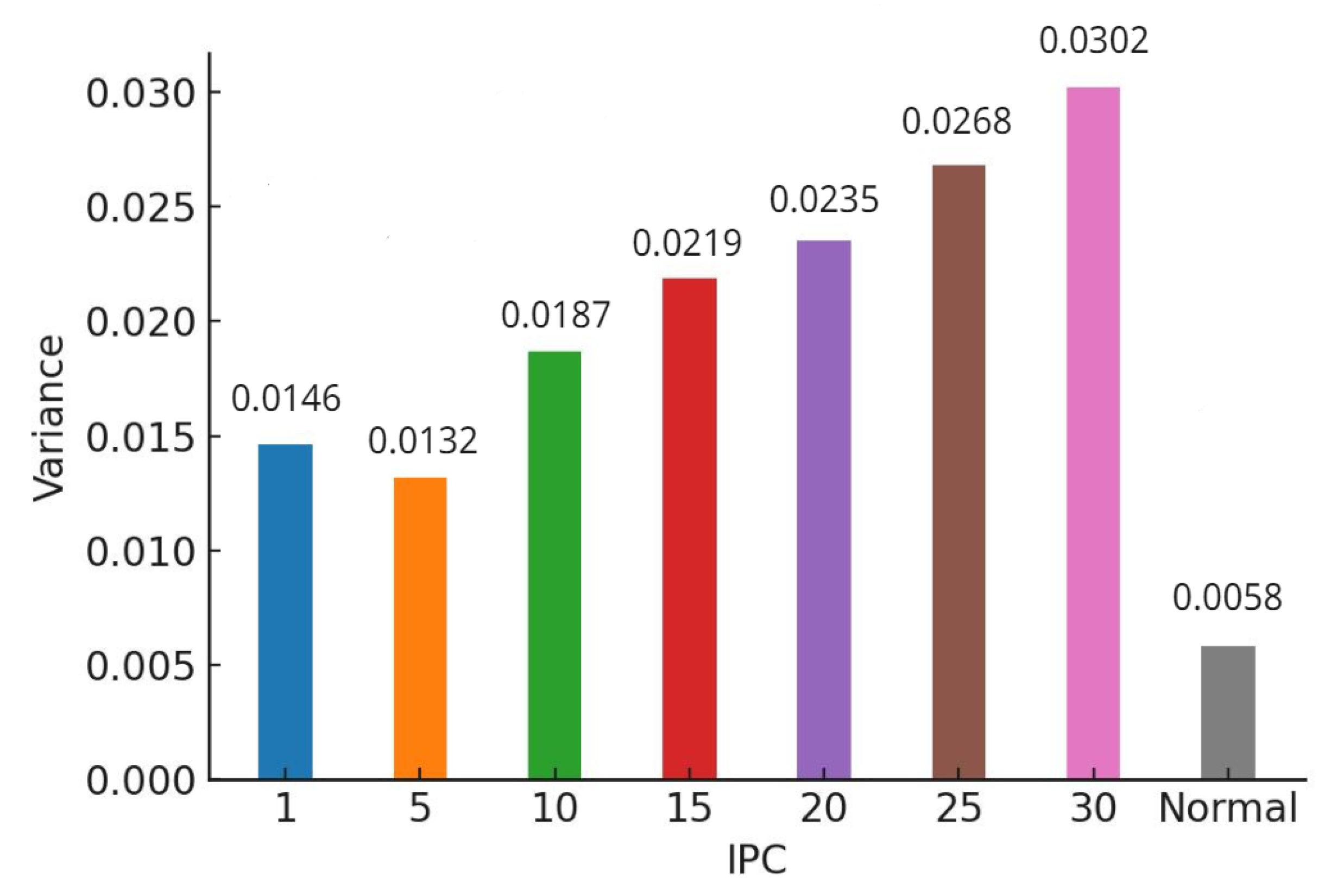

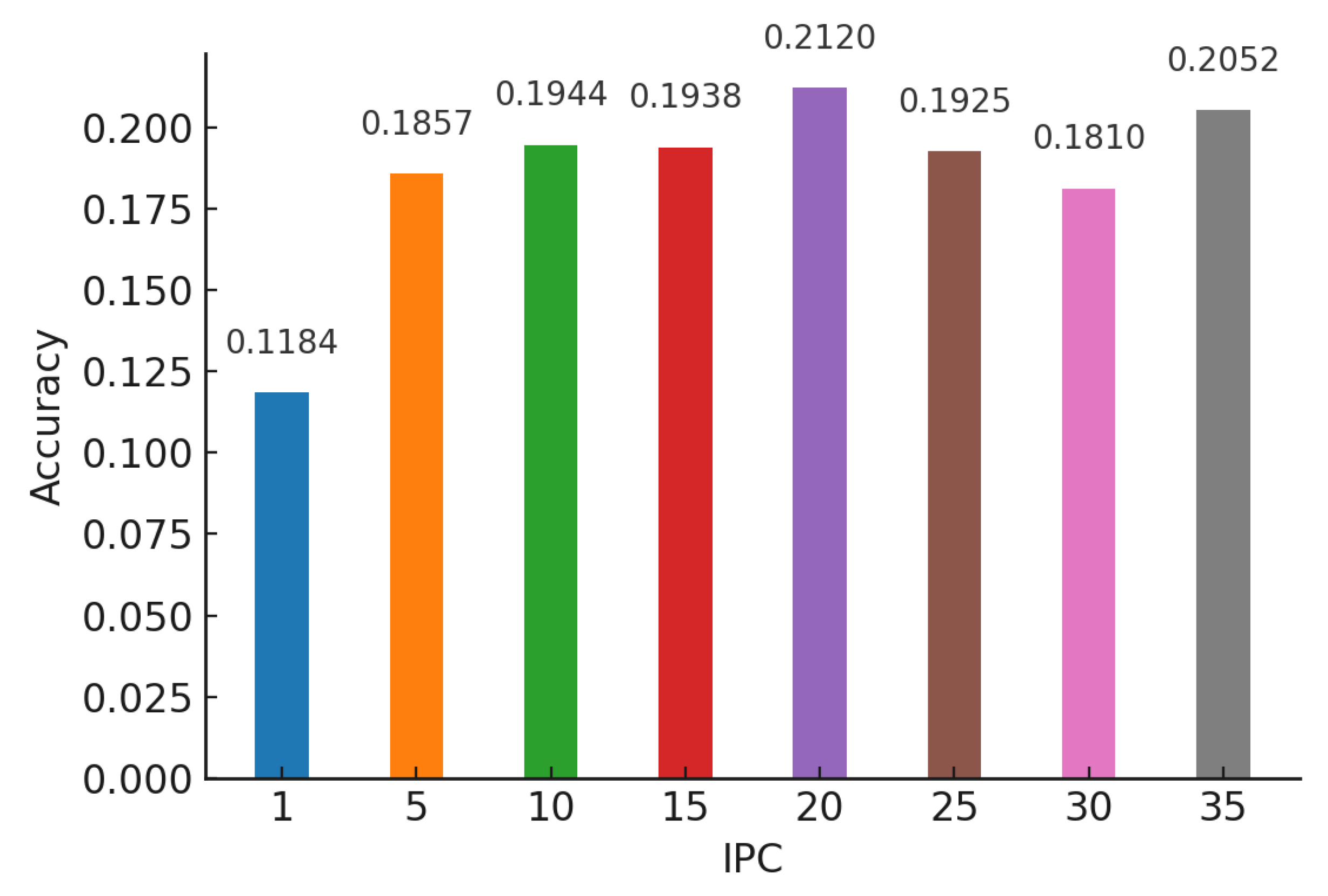

Figure 6), ConvNet for CIFAR-10 (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8), and ConvNet for CIFAR-100 (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). A key finding of this study is that while increasing the size of the distilled dataset enhances overall accuracy, this improvement is concomitant with an increase in class-wise variance.

The term increased class-wise variance signifies that the accuracy of the model demonstrates more significant fluctuations between different classes. This suggests that, although the model may achieve better average performance, the consistency of its accuracy across various classes diminishes. For instance, the model may excel in certain classes while performing considerably worse in others, leading to less equitable outcomes.

Our results underscore a fundamental tension inherent in the use of distilled datasets: optimizing for overall accuracy may come at the expense of fairness, as evidenced by the increased disparity in accuracy across classes.

5. Conclusion

Our study revealed insightful trends in the behavior of classifiers trained on DDMs compared to BLM. We observed that DDMs, while generally exhibiting lower accuracy than BLM, show a positive correlation between dataset size and accuracy as shown in

Figure 11. This finding underscores the complexity of dataset distillation, where larger distilled datasets lead to enhanced model performance but also increased variance across different classes. Specifically, as the size of the distilled dataset increases, both accuracy and class-wise variance exhibit a concurrent rise. This correlation indicates that while optimizing for accuracy through larger datasets is beneficial, it can compromise the consistency of model performance across diverse classes, resulting in potential inequities. Our findings highlight a critical tension in machine learning practices: enhancing computational efficiency through dataset distillation must be balanced with the imperative of fairness. Therefore, it is essential for practitioners to rigorously evaluate the implications of dataset distillation methodologies, ensuring that advancements do not come at the cost of ethical considerations in AI applications. Future research should continue to explore this intricate interplay, contributing to a more equitable deployment of machine learning models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S. and H.S.; methodology, K.S., H.S., R.H.; software, K.S., R.H; validation, K.S., H.S. and M.P.; formal analysis, M.P.; investigation, K.S., H.S., R.H.; resources, H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, K.S., H.S., R.H; writing—review and editing, K.S., H.S., M.P; visualization, K.S., H.S., R.H, M.P; supervision, K.S, H.S, M.M.; project administration, H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Economic Development of the Russian Federation (agreement No. 139-10-2025-034 dd. 19.06.2025, IGK 000000C313925P4D0002).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Economic Development of the Russian Federation (agreement No. 139-10-2025-034 dd. 19.06.2025, IGK 000000C313925P4D0002).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dana Pessach and Erez Shmueli. goog. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 55(3):1–44, 2022. ACM New York, NY.

- Simon Caton and Christian Haas. Fairness in machine learning: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys, 56(7):1–38, 2024. ACM New York, NY.

- Ninareh Mehrabi, Fred Morstatter, Nripsuta Saxena, Kristina Lerman, and Aram Galstyan. A survey on bias and fairness in machine learning. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 54(6):1–35, 2021. ACM New York, NY, USA. [CrossRef]

- Luca Oneto and Silvia Chiappa. Fairness in machine learning. In Recent trends in learning from data: Tutorials from the inns big data and deep learning conference (innsbddl2019), pages 155–196, 2020. Springer.

- Reuben Binns. Fairness in machine learning: Lessons from political philosophy. In Conference on fairness, accountability and transparency, pages 149–159, 2018. PMLR.

- Wang, T., Zhu, J.-Y., Torralba, A., & Efros, A. A. (2020). Dataset Distillation. arXiv. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1811.10959.

- S. Lei and D. Tao, “A comprehensive survey of dataset distillation,” IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Sajedi, S. Khaki, E. Amjadian, L. Z. Liu, Y. A. Lawryshyn, and K. N. Plataniotis, “Datadam: Efficient dataset distillation with attention matching,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 17097–17107.

- Y. Liu, J. Gu, K. Wang, Z. Zhu, W. Jiang, and Y. You, “Dream: Efficient dataset distillation by representative matching,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 17314–17324.

- Kyriaki A. Tychola, Theofanis Kalampokas, and George A. Papakostas, “Quantum machine learning—an overview,” Electronics, vol. 12, no. 11, p. 2379, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hadi Salloum, Kamil Sabbagh, Vladislav Savchuk, Ruslan Lukin, Osama Orabi, Marat Isangulov, and Manuel Mazzara, “Performance of Quantum Annealing Machine Learning Classification Models on ADMET Datasets,”.

- Cazenavette, G., Wang, T., Torralba, A., Efros, A. A., & Zhu, J.-Y. (2022). Dataset Distillation by Matching Training Trajectories. arXiv. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/2203.11932.

- Radosavovic, I., Dollar, P., Girshick, R., Gkioxari, G., & He, K. (2018). Data Distillation: Towards Omni-Supervised Learning. In 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 4119-4128). Salt Lake City, UT, USA: IEEE. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00433.

- Sachdeva, N., & McAuley, J. (2023). Data Distillation: A Survey. arXiv. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/2301.04272.

- Tan, S., Caruana, R., Hooker, G., & Lou, Y. (2018). Distill-and-Compare: Auditing Black-Box Models Using Transparent Model Distillation. In Proceedings of the 2018 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (pp. 303-310). doi:10.1145/3278721.3278725.

- Lukasik, M., Bhojanapalli, S., Menon, A. K., & Kumar, S. (2021). Teacher’s pet: understanding and mitigating biases in distillation. arXiv. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/2106.10494.

- Chen, Z., Geng, J., Zhu, D., Woisetschlaeger, H., Li, Q., Schimmler, S., Mayer, R., & Rong, C. (2023). A Comprehensive Study on Dataset Distillation: Performance, Privacy, Robustness and Fairness. arXiv. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/2305.03355.

- G. Hinton, O. Vinyals, and J. Dean, "Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network," arXiv:1503.02531, Mar. 2015. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1503.02531.

- B. Zhao and H. Bilen, "Dataset Condensation with Differentiable Siamese Augmentation," [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2104.07513.

- C. Wang, J. Sun, Z. Dong, R. Li, and R. Zhang, "Gradient Matching for Categorical Data Distillation in CTR Prediction," in *Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems*, New York, NY, USA, Sep. 2023, pp. 161-170, doi: 10.1145/3604915.3608769.

- B. Zhao and H. Bilen, "Synthesizing Informative Training Samples with GAN," arXiv:2204.07513, Dec. 2022. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2204.07513.

- B. Zhao, K. R. Mopuri, and H. Bilen, "Dataset Condensation with Gradient Matching," arXiv:2006.05929, Mar. 2021. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2006.05929.

- B. Zhao and H. Bilen, "Dataset Condensation with Distribution Matching," in *2023 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV)*, Waikoloa, HI, USA, Jan. 2023, pp. 6503-6512, doi: 10.1109/WACV56688.2023.00645.

- Y. Zhou and E. Nezhadarya, "Dataset Distillation using Neural Feature Regression," [Online]. Available: https://sites.google.com/view/frepo.

- K. Wang, B. Zhao, X. Peng, Z. Zhu, S. Yang, S. Wang, G. Huang, H. Bilen, X. Wang, and Y. You, "CAFE: Learning to Condense Dataset by Aligning Features," in 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 2022, pp. 12186-12195. doi: 10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.01188. Available: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9879629/.

- J. Cui, R. Wang, S. Si, and C.-J. Hsieh, "Scaling Up Dataset Distillation to ImageNet-1K with Constant Memory," [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2011.00050. [Accessed: 24-Sep-2023].

- N. Loo, R. Hasani, A. Amini, and D. Rus, "Efficient Dataset Distillation using Random Feature Approximation," [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2011.00050. [Accessed: 24-Sep-2023].

- Z. Deng and O. Russakovsky, "Remember the Past: Distilling Datasets into Addressable Memories for Neural Networks," [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2011.00050. [Accessed: 24-Sep-2023].

- S. Lee, S. Chun, S. Jung, S. Yun, and S. Yoon, "Dataset Condensation with Contrastive Signals," [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2011.00050. [Accessed: 24-Sep-2023].

- T. Nguyen, Z. Chen, and J. Lee, "Dataset Meta-Learning from Kernel Ridge-Regression," arXiv, Mar. 2021. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2011.00050. [Accessed: 24-Sep-2023].

- X. Han, A. Shen, Y. Li, L. Frermann, T. Baldwin, and T. Cohn, "Towards Fair Supervised Dataset Distillation for Text Classification," [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2011.00050. [Accessed: 24-Sep-2023].

- J. Chai, T. Jang, and X. Wang, "Fairness without Demographics through Knowledge Distillation," [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2011.00050. [Accessed: 24-Sep-2023].

- N. Mehrabi, F. Morstatter, N. Saxena, K. Lerman, and A. Galstyan, "A Survey on Bias and Fairness in Machine Learning," arXiv, Jan. 2022. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2011.00050. [Accessed: 24-Sep-2023].

- Zhen Yu, Yang Liu, and Qingchao Chen. "Progressive trajectory matching for medical dataset distillation." arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.13469, 2024.

- Yongchao Zhou, Ehsan Nezhadarya, and Jimmy Ba. "Dataset distillation using neural feature regression." Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 35, pp. 9813–9827, 2022.

- Jiawei Du, Qin Shi, and Joey Tianyi Zhou. "Sequential subset matching for dataset distillation." Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 36, 2024.

- Yongmin Lee and Hye Won Chung. "SelMatch: Effectively scaling up dataset distillation via selection-based initialization and partial updates by trajectory matching." In Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning, 2024.

- A. Krizhevsky, G. Hinton, et al., “Convolutional deep belief networks on CIFAR-10,” Unpublished manuscript, vol. 40, no. 7, pp. 1–9, 2010.

- B. Recht, R. Roelofs, L. Schmidt, and V. Shankar, “Do CIFAR-10 classifiers generalize to CIFAR-10?,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.00451, 2018.

- A. Krizhevsky, I. Sutskever, and G. E. Hinton, “Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 25, 2012.

- Sahil Singla, Surbhi Singla, and Soheil Feizi. "Improved deterministic l2 robustness on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100." arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.04062, 2021.

- Neha Sharma, Vibhor Jain, and Anju Mishra. "An analysis of convolutional neural networks for image classification." Procedia Computer Science, vol. 132, pp. 377–384, 2018. Elsevier.

- H.-C. Chen, A. M. Widodo, A. Wisnujati, M. Rahaman, J. C.-W. Lin, L. Chen, and C.-E. Weng, “AlexNet convolutional neural network for disease detection and classification of tomato leaf,” Electronics, vol. 11, no. 6, p. 951, 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Yu, K. Yang, Y. Bai, T. Xiao, H. Yao, and Y. Rui, “Visualizing and comparing AlexNet and VGG using deconvolutional layers,” in Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning, 2016.

- S. Cong and Y. Zhou, “A review of convolutional neural network architectures and their optimizations,” Artificial Intelligence Review, vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 1905–1969, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Taye, “Theoretical understanding of convolutional neural network: Concepts, architectures, applications, future directions,” Computation, vol. 11, no. 3, p. 52, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Shyam, “Convolutional neural network and its architectures,” Journal of Computer Technology & Applications, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 6–14, 2021.

- A. Krizhevsky, “Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images,” University of Toronto, 2009.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).