1. Introduction

The heart is the organ responsible for pumping blood to supply oxygen and nutrients to other organs throughout the body. Cardiomyocytes (CMs) and cardiac fibroblasts (CFs) are the two major cell types in the heart. CMs handle the contractile function of the heart, while CFs stabilize the cardiac structure and repair potential cardiac damage. Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Heart failure (HF), a major manifestation of cardiovascular disease, often results from cardiac ischemic events such as myocardial infarction (MI). About 64 million people worldwide are affected by HF, and half of these patients will die within five years of diagnosis (1). An MI triggers proliferation and activation of cardiac fibroblasts; if uncontrolled, this can lead to excessive cardiac fibrosis, reducing heart function and leading to HF. HF is categorized based on ejection fraction (EF), which measures the percentage of blood pumped out of the heart with each beat: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) (2). HFrEF occurs when the left ventricle cannot contract properly and ejects less oxygen-rich blood after MI. Conversely, HFpEF maintains an EF above 50% but has impaired diastolic function and a reduced ability to fill the left ventricle with oxygenated blood, often developing after long-term hypertension, obesity, or diabetes. Chronic HF remains the leading cause of hospitalization among patients over 65 and poses significant clinical challenges and economic burdens both in the U.S. and globally.

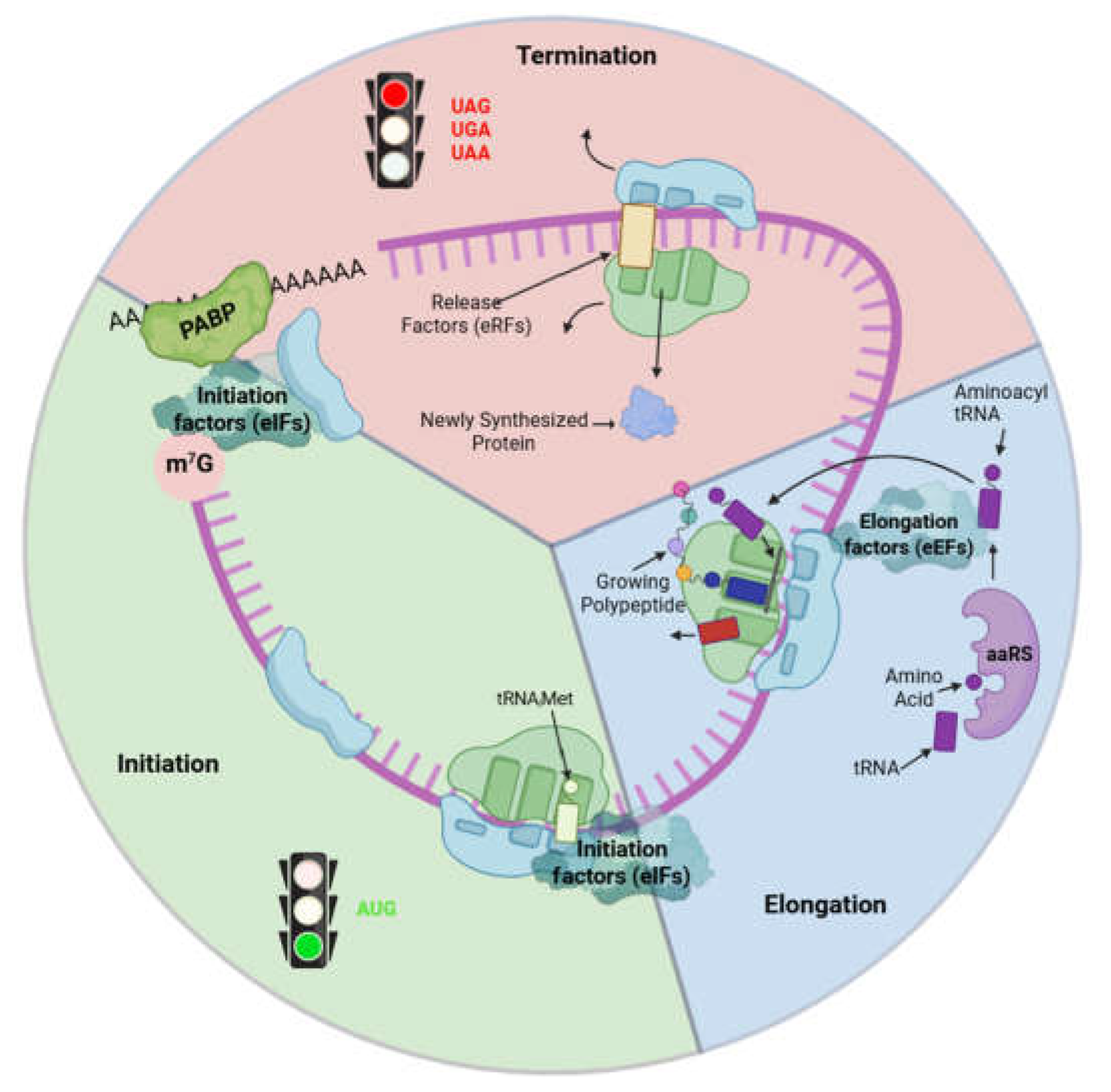

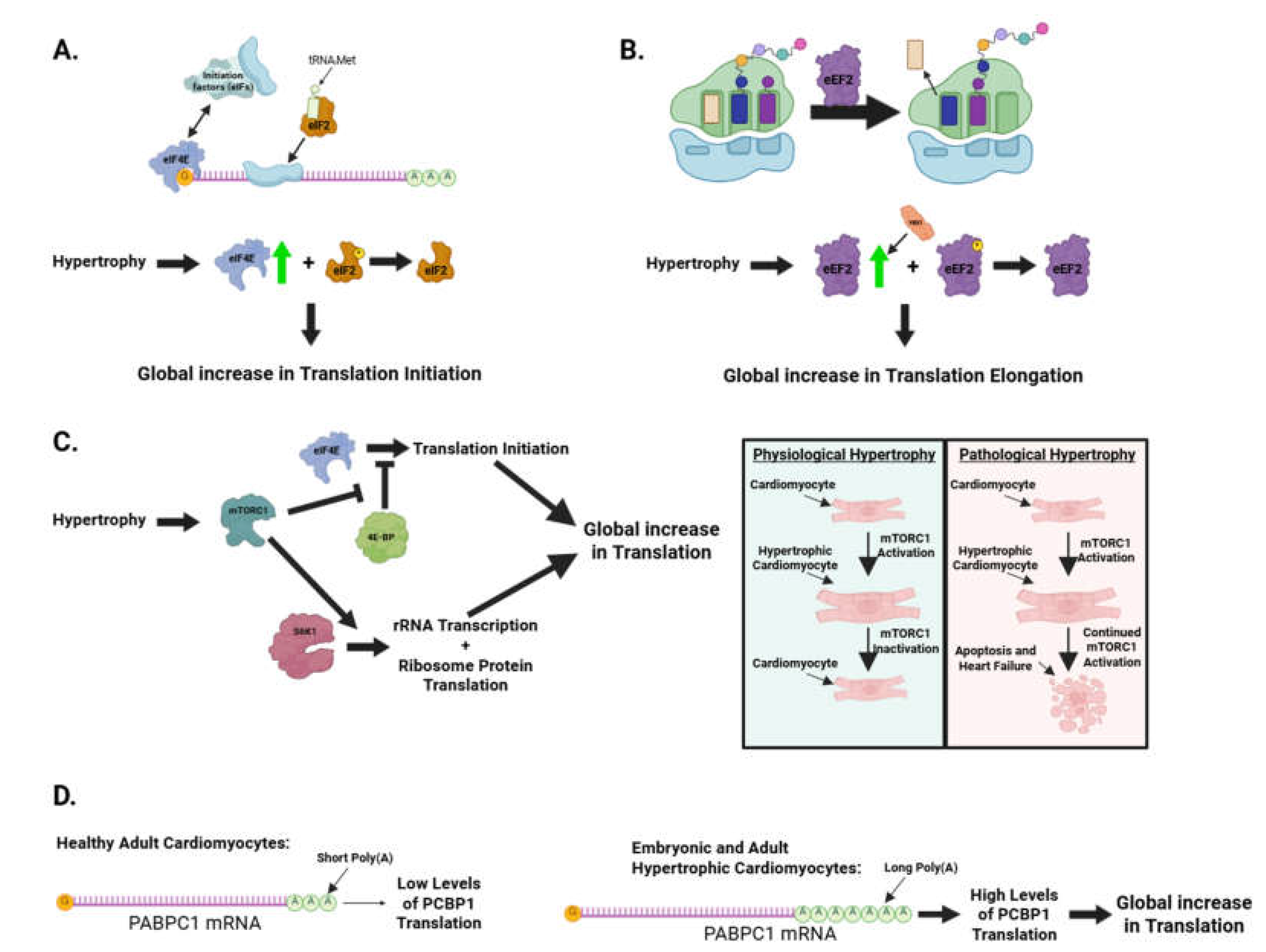

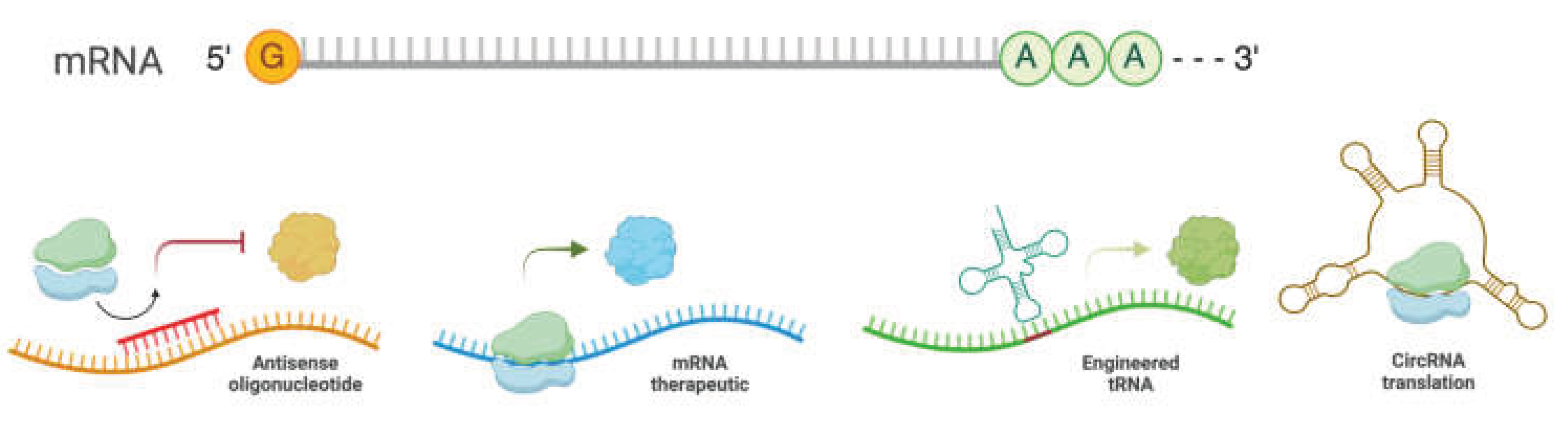

The central dogma of molecular biology states that DNA is transcribed into mRNA (transcription), and mRNA is then translated into proteins (translation). Although transcriptional regulation has been studied extensively, fewer investigations have focused on understanding cardiac health and disease through translational control. Translation is crucial in producing functional proteins following DNA transcription to mRNA in all biological processes (Figure 1), including cardiac cell proliferation, differentiation, hypertrophy, and fibrosis. While increased protein synthesis of pro-hypertrophic and pro-fibrotic genes has been observed during cardiac remodeling, transcriptional regulation alone does not explain all the increases. Transcription factors and microRNAs (miRNAs) are sequence-specific regulators of transcription and post-transcriptional processes (mRNA stability and translatability), respectively. The roles and mechanisms of transcription factors and miRNAs in cardiac biology have been extensively studied over the past twenty years. However, little is known about the molecular mechanisms of miRNA-independent translational control and the therapeutic potential of targeting the general translation process or transcript-specific translational regulation in heart disease treatment. Understanding the abnormal translation control mechanisms that promote pro-hypertrophic and pro-fibrotic mRNA translation in cardiac cells is essential.

Figure 1.

Overview of mammalian mRNA translation.

Figure 1.

Overview of mammalian mRNA translation.

In any eukaryotic cell, two sets of translation machinery exist: one in the cytoplasm and one in the mitochondria. Both translation machines have four major components: aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (ARSs), translation factors, ribosomes, and translation-regulatory RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) (Figure 1). ARSs are a family of evolutionarily conserved housekeeping enzymes ubiquitously present in the three major domains of life. ARSs catalyze the ligation of amino acids to the 3'-terminus of cognate tRNAs bearing the correct anticodon triplet to ensure accurate “reading” of mRNA to protein according to the genetic code (3, 4). Mammals have 20 cytoplasmic ARSs and 17 nuclear-encoded mitochondrial ARSs (3 ARSs are common in both cellular compartments). ARSs generally contain catalytic aminoacylation and tRNA anticodon recognition functions in separate domains. Several ARSs, including LARS1, IARS1, VARS1, AARS1, TARS1, FARS1, and EPRS1, contain a separate editing domain for hydrolyzing mis-aminoacylated products to maintain translation fidelity (5, 6). Translation factors such as initiation, elongation, and termination factors are required for uploading, translocating, and disassembling ribosome subunits, respectively. Cytoplasmic ribosomes comprise a 40S small subunit and a 60S large subunit, while mitochondrial ribosomes comprise a 28S small subunit and a 39S large subunit. All ribosome subunits consist of numerous ribosome proteins associated with ribosomal RNAs and are central for protein biosynthesis. RNA-binding proteins and miRNAs bind to sequence- or structure-specific cis-acting elements and regulate the translation efficiency of target mRNAs. In any disease state, phenotypic changes are driven by the alteration of pathogenic proteins produced by the translation machinery. However, due to translational control, the protein expression often does not correlate with mRNA abundance (7, 8).

Prior reviews have extensively discussed RNA-binding proteins and mRNA metabolism at the posttranscriptional level (9, 10). This review will focus on understanding translational control in cardiac biology and heart disease. We first introduce various techniques that can be used to study translational control: biochemical methods, deep sequencing, and imaging-based techniques. We then discuss translational control in cardiac development and congenital heart disease. We follow this with an overview of translational control in adult cardiac disease. Finally, we discuss therapies that target translational control mechanisms and what we believe are future areas of interest for investigations and therapies based on translational control in the heart.

2. Techniques and Methods to Investigate mRNA Translation in the Heart

2.1. Biochemical methods for studying translational control

2.1.1. RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation (RIP) to identify bound target RNAs

This method uses immunoprecipitation via specific antibodies to apply the pulldown of a specific target protein and its respective negative control (11, 12). Briefly, healthy growing cells or tissues (such as cardiac cells or the heart) undergo lysis with appropriate RNase and protease inhibitors, and cell or tissue lysates are prepared for immunoprecipitation. An immunoprecipitation-graded antibody for a target protein and a specific IgG isotype control are used for the RIP experiment. Before immunoprecipitation, blocking and pre-clearing steps can be performed to minimize nonspecifically interacting proteins pulled down. mRNAs and interacting proteins can be extracted separately from the precipitated protein-RNA complexes. The isolated RNAs are used for quantitative (q)PCR or next-generation deep sequencing (RIP-seq) to check for RNA association or determine the global RNA targets. The retrieved proteins are subjected to immunoblot or mass spectrometry to confirm protein interaction or unbiasedly identify the interactome of the target protein of interest.

2.1.2. Crosslinking and immunoprecipitation (CLIP) to map RBP-binding sites on RNAs

This method examines the direct physical association between RNAs and their interacting proteins (13, 14). CLIP applies UV or formaldehyde crosslinking of live cells or tissues, which forms covalent bonds between RNAs and proteins in proximity (15, 16). Cell or tissue lysates are then prepared and subjected to partial fragmentation by a selected ribonuclease (e.g., RNase A or T1), followed by immunoprecipitation using a validated antibody for the target protein of interest and an IgG isotype control antibody. RNA fragments from the precipitated protein-RNA complexes are ligated with DNA adaptors on 3' and 5' ends (for individual-nucleotide resolution CLIP (iCLIP), DNA adaptors can be ligated on 5' ends after reverse transcription) and purified by SDS-PAGE with size selection. The isolated products are subjected to proteinase K digestion and reverse transcription to cDNA and amplified by appropriate cycles of PCR reaction. Following the library construction, next-generation deep sequencing (CLIP-seq) is carried out to map transcriptome-wide protein binding sites on RNAs. If an immunoprecipitation-competent antibody for the target protein is unavailable, recombinant tagged RNA-binding proteins can be overexpressed, or transgenic tagging of endogenous RNA-binding proteins can be used for CLIP in a specific cell type.

2.1.3. In vitro pulldown of interacting proteins of biotinylated RNA

This technique uses a cell-free system to study RBP and RNA interactions. Briefly, RNA can be in vitro transcribed with internal biotin (biotinylated CTP) or 5' biotin modification and incubated with cardiac cell or tissue lysates to capture interactions with specific RNA-binding proteins. The respective control oligo (scrambled or antisense oligo) and only beads are taken as negative controls, and an immunoblotting experiment is undertaken to decipher any possible interactions (17). Alternatively, mass spectrometry analysis can be conducted to identify novel RNA-interacting proteins as an unbiased approach, followed by immunoblot confirmation.

2.1.4. Proximity ligation assay associated with immunoblot or mass spectrometry

This technique applies selective biotinylating of proteins adjacent to a target protein of interest and can be used to study protein-protein interactions (18). In brief, a biotin ligase is fused to a target protein of interest and expressed in living cells, which biotinylates proteins that potentially interact with the target protein in the presence of external biotin added to culture media. The biotinylated proteins can be isolated using streptavidin beads and coupled with mass spectrometry or immunoblot analysis to examine protein-protein interactions and draw the interactome atlas of the target protein of interest. The mass spectrometry-based, label-free quantitative proteomics data (e.g., spectral count or intensity) can be scored using the SAINT (Significance Analysis of INTeractome) software package to identify high-confidence protein-protein interactions (SAINT score > 0.95) (19).

2.1.5. Puromycin incorporation assay to assess global translation efficiency

This is the most commonly used technique for studying the protein synthesis status of cultured primary cells in vitro and animal tissues in vivo (20). Cells are subjected to puromycin treatment for 15-20 minutes at a 37ºC incubator, followed by harvesting with a cell lysis buffer containing an appropriate protease inhibitor for protein isolation. The cellular protein lysates undergo immunoblotting analysis. Untreated cells are used as a negative control. In vivo puromycin incorporation allows imaging of nascent proteins and evaluating the regulation of translation spatially and temporally in whole organisms (21). An alkyne analog of puromycin, O-propargyl-puromycin (OP-puro), can form covalent conjugates with nascent polypeptide chains and label and visualize nascent proteins in the target organ of interest. This method broadly applies to imaging protein synthesis under physiological and pathological conditions in vitro and in vivo.

2.2. Deep sequencing-based translatome profiling in cells and animals

2.2.1. Polysome profiling-sequencing (polysome-seq)

Total cell or tissue lysates are subject to sucrose gradient solution and ultracentrifugation to separate different translation fractions, including free mRNP (mRNA-ribonucleoprotein complex), 40S ribosome small subunit, 60S ribosome large subunit, 80S monosome, and polysomes (disome, trisome, and multiple ribosomes). Actively translated mRNAs bound by polysomes can be determined by next-generation deep sequencing to evaluate the translation efficiency of individual mRNAs as normalized by total RNA-seq signal (22). Also, multiple pools can be collected, including non-polysome, monosome, and polysome, and their associated RNAs can be sequenced to calculate the distribution of specific mRNAs among different pools or individual fractions as translation efficiency, depending on the cost efficiency and demand of the resolution.

2.2.2. Translating ribosome affinity purification sequencing (TRAP-seq)

Genetic engineering of endogenous ribosome protein-coding genes in the mouse genome introduces a peptide or protein tag to the gene for subsequent affinity pulldown of ribosomes in vivo. Currently, three conditional inducible knock-in mouse models are available, including RPL22-3xHA, RPL10-EGFP, and mRPL62-FLAG (23-25). In the former two cases, cytoplasmic ribosomes can be affinity-purified using HA or EGFP antibodies from tissue lysates to capture ribosomes from a specific cell type by immunoprecipitation of the large ribosome subunit proteins RPL22 or RPL10 based on the use of the Cre recombinase transgenic mouse model. The latter targets the mitochondrial large ribosome subunit protein mRPL62 for purifying ribosomes in mitochondria. RNA-seq following the translating ribosome affinity purification (TRAP-seq) quantitatively measures the translation efficiency in a specific cell type across various organs in vivo.

2.2.3. Translational landscape in human and mouse heart failure determined by ribosome profiling (Ribo-seq)

Ribosome profiling, also known as Ribo-seq, is a technique that measures the activity of ribosomes in translating mRNA into protein in a cell at a specific time. Ribo-seq uses deep sequencing to analyze ribosome-protected mRNA fragments after digesting the unprotected RNA around the ribosome footprints with ribonucleases, like micrococcal nuclease or RNase I. The sequenced ribosome-protected fragments can be used to determine the positions of the translating ribosomes to define open reading frames (ORF), determine the protein synthesis rate, map translation start sites, examine translational control, and identify ribosome stalling sites. Ribosome profiling provides a snapshot of ribosome density on individual mRNAs and translation activity.

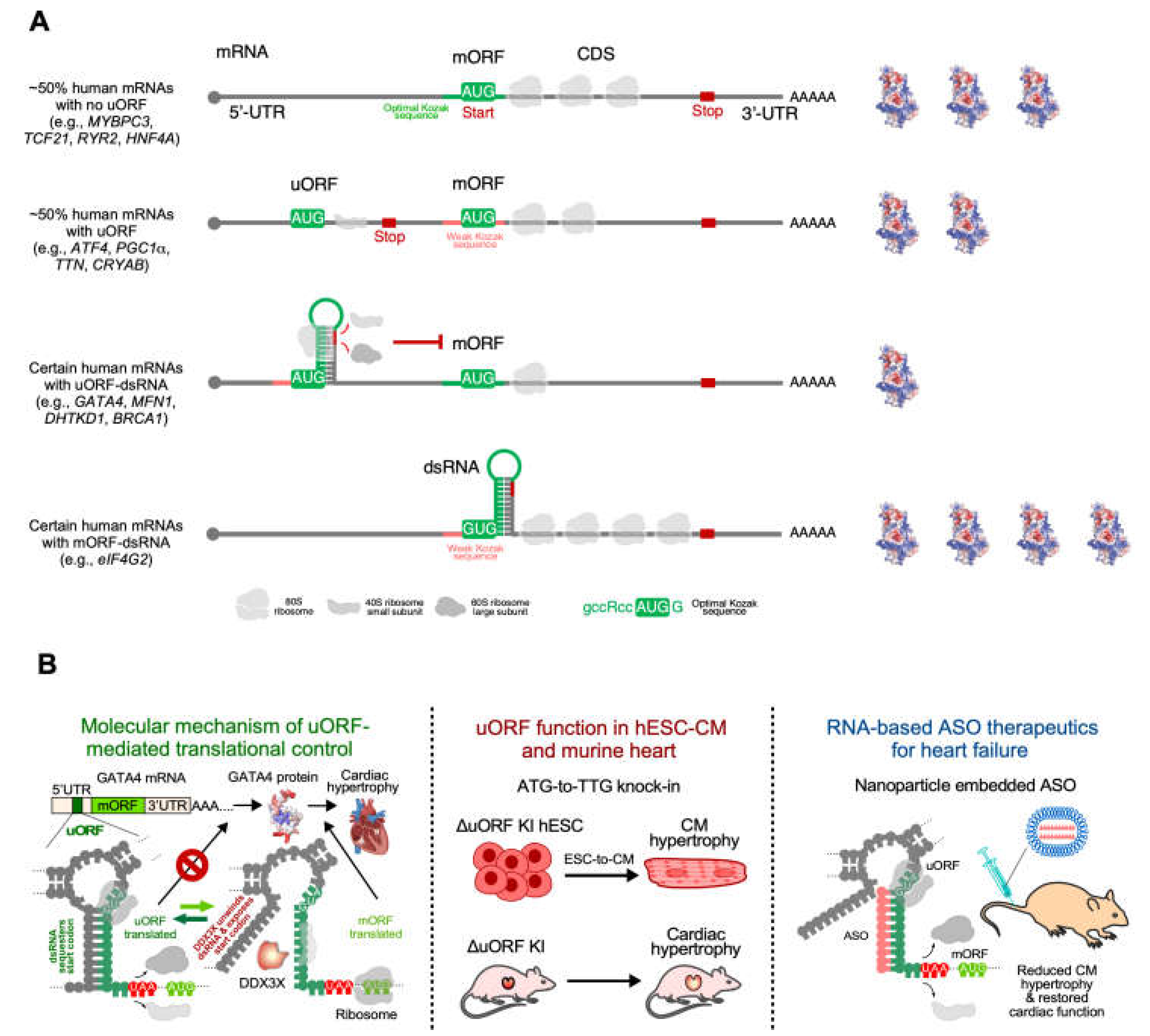

Our understanding of translational control of gene expression in human diseases has always been sparse and less systematic due to the diversity of global and specific regulation machinery. A recent study by van Heesch, S., et al. has attempted to solve this problem and provide a comprehensive landscape of translational regulation related to heart failure (26) by combining RNA-seq, ribosome profiling (Ribo-seq), and mass spectrometry. Results were generated from 80 human hearts, including 65 failing and 15 non-failing hearts. The investigators provided a detailed assessment of translational control in the human heart, including regulation of translation by diverse cis- or trans-elements. By comparing RNA-seq and Ribo-seq results, the investigators revealed translational downregulation of 327 genes and upregulation of 474 genes, including many cardiac disease marker genes, such as the extracellular matrix components genes associated with cardiac fibrosis. They also revealed specific cis-acting elements on mRNA correlated with translational regulation. For example, transcripts with a 5' terminal oligopyrimidine (TOP) motif are significantly translationally upregulated, which agrees with previous studies about mTOR activation during heart disease. Apart from the 5' TOP motif, upstream open reading frames (uORFs), another cis-acting element known to affect translation, have also been detected. They suggest no detectable correlation between the translation efficiency of the main ORF and the efficiency of uORF for most of the proteins. However, several proteins, such as eIF4G2, show an anti-correlation between the translation of the main ORF versus uORF, indicating a selective negative regulation of specific mRNAs via uORF in the diseased human hearts at the endpoint. Alternatively, the correlation analysis using the whole hearts at the endpoint of heart failure does not reveal the causative relationship between the translations of uORF and mORF due to the lack of temporal and spatial resolutions, regarding early versus late stages of disease status and averaging effects from multiple cell types and anatomic locations.

They also detected a correlation between naturally occurring genetic variations and translation. They monitored the influence of single-nucleotide variants, insertions, and deletions on mRNA abundance, ribosome occupancy, and translation efficiency. Although most variations do not correlate with ribosome occupancy or translation efficiency, genetic association with translation is detected for around 100 genes. Intriguingly, nonsense genetic mutations do not efficiently induce nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) since many protein-truncated variants (PTVs) are detected at the mRNA level. Ribosome occupancy of these PTVs shows little difference upstream or downstream of the premature stop codon, indicating inefficient termination or efficient re-initiation. The presence of these PTVs provides a possible cause of cardiac disease. Titin-truncating variants (TTNtvs) are detected in 13 dilated cardiomyopathy patients with different constitutive exons. No evidence of efficient NMD has been found, and significant ribosome occupancy downstream of the premature stop codon is detected in some cases, indicating that different TTNtvs may be translated differently and affect cardiac function in various ways. This observation partially explains the incomplete penetrance of heart disease occurrence in human patients with the same genetic mutation of TTNtvs. One possibility is additional expression and activity changes in eukaryotic release factors that may cause ribosome readthrough of premature termination codons but not native stop codons.

To complement Ribo-seq in whole human hearts, cell-type-specific translatomic analysis has been conducted. For instance, although post-transcriptional regulators such as IL-11 have been identified as related to cardiac fibrosis (27), the post-transcriptional mechanisms underlying myofibroblast transformation remained unexplored until 2019, when Chothani, S., et al. monitored the global changes of transcriptome and translatome during human cardiac fibroblast activation and transformation to myofibroblast using RNA-seq and ribosome profiling (28). TGFβ was used to stimulate fibrosis in primary cardiac fibroblasts isolated from atrial biopsies. Then, they performed RNA-seq and Ribo-seq at baseline and in a time-course ranging from 45 minutes to 24 hours after TGFβ stimulation to capture a dynamic picture of the transcriptional and posttranscriptional changes underlying the transition of quiescent fibroblasts into myofibroblasts.

They identified dynamically transcribed genes from RNA-seq and determined dynamically translated mRNAs from the integrated analysis of both RNA-seq and Ribo-seq results. A total of 1691 dynamically translated mRNAs were captured during the fibrotic response, of which translational changes alone were enough to cause changes in protein abundance. Sixty-seven dynamically translated mRNAs showed instant translational changes 45 minutes after TGFβ stimulation. The most enriched gene ontology term of those dynamically translated mRNAs was "transcription regulator activity," suggesting that instant translational changes may modulate subsequent transcriptional changes. The impact of translation then gradually decreases at later time points while the effect of transcription gradually increases, indicating a possible shift from translational regulation to transcriptional regulation. However, although plenty of dynamically transcribed genes were detected, about 29% of the transcriptional changes are buffered by translational regulation, implying that translation efficiency may be upregulated on genes with limited transcripts or vice versa.

Chothani S. et al. suggest that over one-third of all gene expression changes detected in myofibroblast transformation involve translational regulation, which may be carried out through RNA-binding proteins (RBPs). During myofibroblast transformation, fifty-three differentially expressed RBPs were detected. The targets of these RBPs were predominantly enriched in dynamically translated genes, but not in dynamically transcribed genes, highlighting the possibility that these RBPs shape the fibrotic response. However, loss-of-function and gain-of-function validation studies for individual RBPs are required to form the causative relationship between these RBPs and the fibrotic response.

2.3. Imaging-based techniques for evaluating translation efficiency and localized translation in cardiomyocytes

Puromycin, an unnatural analog of tyrosyl-tRNA, can be incorporated into the aminoacyl (A) site of translating ribosomes, leading to truncated protein production terminated at this residue. Treatment of cultured cardiac cells with puromycin can evaluate the global protein synthesis rate using immunoblot. Moreover, injecting puromycin into animals can allow direct imaging of the translation events in vivo. This method can provide information on the location of translation in organs and allow quantification of the translation efficiency by comparing control and genetically modified or disease-triggering animal models. One example is the visualization of translation machinery colocalized with sarcomere protein network in mouse cardiomyocytes in vivo (29). Macromolecular protein complexes, such as the sarcomere, the basic contractile macromolecular complex of cardiomyocytes, are maintained with proper localization and fixed subunit stoichiometry. Single-cell analysis of cardiomyocytes using mRNA and protein synthesis imaging demonstrates three different but related mechanisms for retaining the sarcomere (29): i) Mature mRNAs encoding sarcomere component proteins are localized to the sarcomere where their protein products are assembled. ii) Translation machinery, such as ribosomes, is located at the sarcomere with localized translation of sarcomere protein-coding mRNAs. iii) A specific localized E3 ubiquitin ligase allows rapid and efficient degradation of excess unincorporated sarcomere component proteins. These three mechanisms are distinct and required. Cooperation of the mechanisms is essential to ensure appropriate spatial localization of sarcomere proteins and to buffer the variability in mRNA expression levels of these proteins. Cardiomyocytes maintain their sarcomeres using localized translation at high rates and continuous proteasomal degradation to remove excess proteins and maintain the homeostatic stoichiometric ratio of different component proteins in the sarcomere protein network. Therefore, tightly regulated localization of mRNA transcripts, translation, and protein degradation controls the organization of sarcomere assembly and maintains the spatiotemporal features.

During cardiac hypertrophy, stress-induced signal transduction enhances CM mRNA translation, adding new contractile sarcomere units to enlarge cell size and enhance contractility. In this process, microtubules are required for cardiomyocyte growth via spatiotemporal control of the translation machinery (30). In particular, Scarborough et al. show that microtubule motor protein Kinesin-1 localizes ribosomes and mRNAs along microtubule tracks to different regions within the cell. Microtubules normally deliver mRNAs and translation machinery to specific sites to promote local translation and cardiomyocyte contractile unit assembly. This microtubule network is disrupted upon hypertrophic stress stimulus (phenylephrine treatment), causing mRNA and ribosome collapse around the nucleus, leading to mislocalized protein synthesis and rapid degradation of newly synthesized proteins. Consequently, cardiomyocytes fail to grow despite increased translation rates, suggesting that properly localized translation, not just the translation rate, is a key determinant of cardiac hypertrophy.

Synthesis of sarcolemma and sarcoplasmic reticulum membrane-associated proteins in cardiomyocytes was assumed to follow the general secretory pathway with localized mRNA translation in perinuclear areas, followed by protein trafficking and delivery to the functional sites. However, limited experimental evidence was provided. Using a single-molecule level visualization and a proximity-ligated in situ hybridization approach, researchers visualized ribosome-associated mRNAs for ion channel-related proteins, such as SERCA2A and SCN5A, providing detailed information on the localized translation sites within the cell (31). The translation machinery for membrane-associated protein synthesis occurs throughout the cardiomyocyte and enables the distributed synthesis of specific transmembrane proteins within specific sub-cellular locations. In these niches, the localized ribosomes synthesize proteins on local mRNA pools trafficked from in the nucleus by association with the microtubules and cytoskeleton network. As an evolutionarily conserved mechanism from mouse to human, membrane protein mRNAs are widely distributed across the cardiomyocyte in normal and failing human heart tissues. These findings confirm that local protein synthesis in cardiomyocytes regulates cardiac structure and function. At the pathophysiological level, arrhythmias and sudden death can occur with a mild imbalance between inward sodium and outward potassium currents. One new paradigm provides insights into the mechanisms of maintaining this critical balance. Electrophysiological and single-molecule fluorescence imaging analysis reveal that two mRNAs encoding SCN5A (INa) and hERG (IKr) channels are associated and coordinated in defined discrete complexes, namely, “micro-translatomes”, during protein translation (32). About half of the hERG-translating complexes contain SCN5A mRNA transcripts. Moreover, both mRNA transcripts are regulated at co-translational levels, and consequently, this regulation alters the expression of both functional ion channels localized at the cytoplasmic membrane.

3. Translational Control in Cardiac Development and Congenital Heart Disease

3.1. Human genetic mutations in translation machinery and congenital heart disease

3.1.1. Diamond Blackfan Anemia and other heart disease-causing mutations in cytoplasmic translation factors

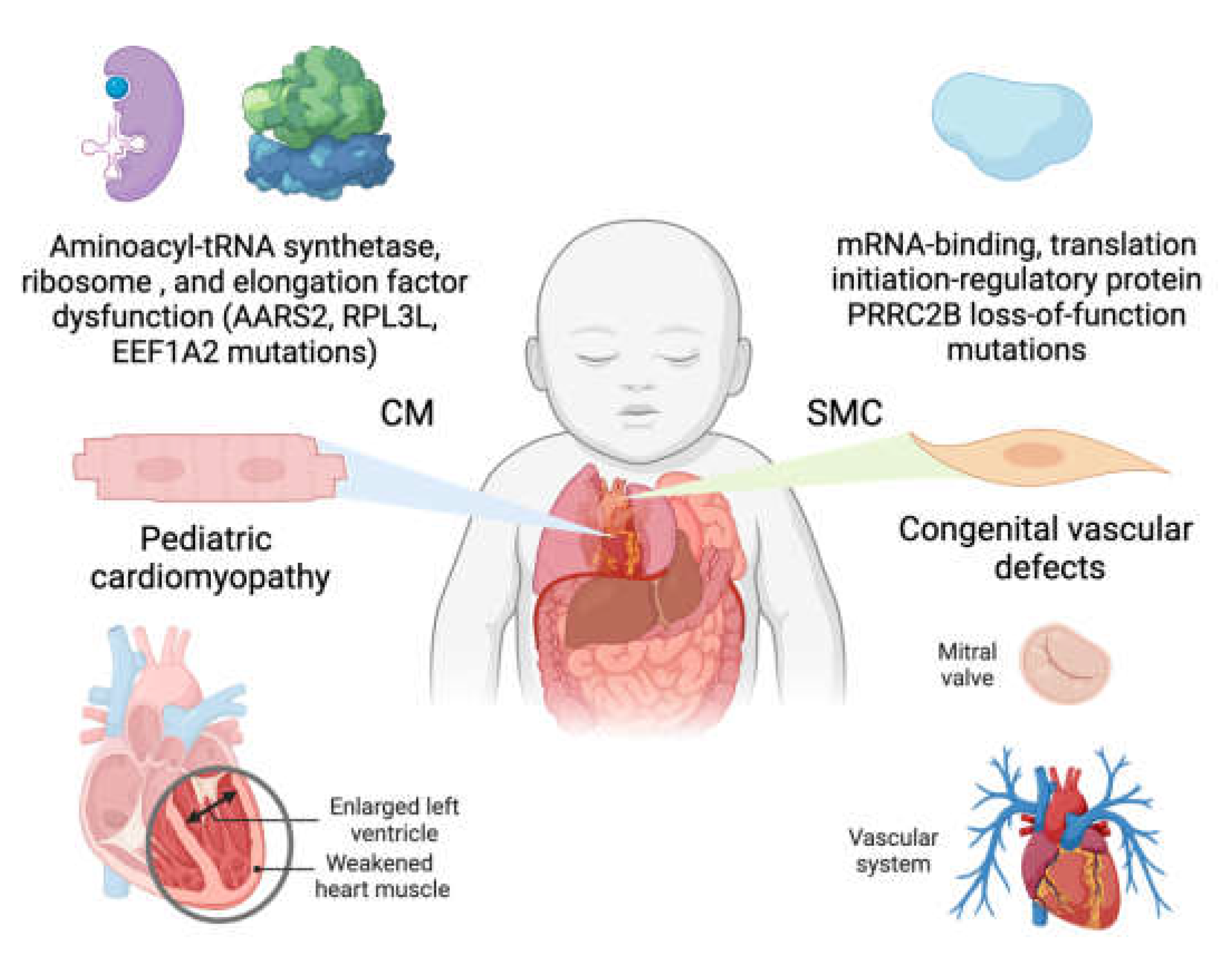

Human genetic mutations in cytoplasmic large ribosomal subunit protein 5 (RPL5), among many other cytoplasmic ribosome protein-coding genes, lead to Diamond Blackfan Anemia with congenital cardiac developmental defects (33-35), suggesting that loss-of-function of general house-keeping translation factors can result in cell-type- and organ-specific disorders. This observation has been well recapitulated in mouse and zebrafish genetic models with ribosome protein mutations (36). Most of these ribosome proteins are expressed ubiquitously across organs and cell types, such as RPL5 and RPL3 (large ribosomal subunit protein 3). Intriguingly, multiple ribosomal protein paralogs are expressed in a tissue-specific manner. It is under debate how these proteins influence translation in specific organs and affect the development and function, such as the heart. Large ribosomal subunit protein 3-like (RPL3L), a paralog of RPL3, is specifically expressed in cardiomyocytes and skeletal muscle cells of the heart and skeletal muscle, respectively, and modulates the dynamics of the translation elongation process. Genetic mutations of RPL3L in humans are associated with pediatric cardiomyopathy and age-related atrial fibrillation (37) (Figure 2). To recapitulate the genetic defects in human patients, a homozygous Rpl3l knockout mouse model has been established in multiple labs. Shiraishi’s group reported that a deficiency of RPL3L-bearing ribosomes in Rpl3l global knockout mice (CRISPR-Cas9-mediated deletion of the exon 2) caused reduced cardiac contractility (38). Transcriptome-wide ribosome profiling assay showed that ribosome occupancy at mRNA genetic codons was changed in the Rpl3l-null heart, and the changes were negatively correlated with those observed in myoblast cells with RPL3L overexpression. Compared with RPL3-bearing canonical ribosomes, RPL3L-bearing ribosomes were less prone to ribosome collisions on the mRNA. The reduction of RPL3L-containing ribosomes reprograms the translation elongation dynamics for the global transcriptome. Intriguingly, this translation-altering effect is most significant for mRNA transcripts encoding proteins related to cardiac muscle contraction and dilated cardiomyopathy, with the quantity of these proteins being decreased due to repressed translation. Thus, RPL3L-bearing ribosomes are essential to maintain the translation elongation dynamics required for normal cardiac function. This finding provides insights into the mechanisms of tissue-specific ribosome protein-mediated translational regulation with physiological and pathological relevance in human patients.

In contrast, Milenkovic’s group recently demonstrated a dynamic interplay between RPL3- and RPL3L-bearing ribosomes that regulates mitochondrial activity and ATP production in the mammalian heart as a translation-independent noncanonical mechanism. Different cell types possess distinct types of ribosomes with specialized ribosome proteins like RPL3L. This phenomenon is defined as ribosome heterogeneity. However, whether this ribosome heterogeneity results in functionally diverse “specialized ribosomes” in canonical mRNA translation or noncanonical functions remains controversial. Milenkovic’s group used a similar but different Rpl3l knockout mouse strain (CRISPR-Cas9-mediated deletion of a 13-bp DNA fragment in the exon 5) to uncover a rescue mechanism in which compensatory induction of RPL3 is triggered upon RPL3L inactivation, accumulating RPL3-bearing ribosomes instead of RPL3L-bearing ribosomes that are uniquely present in cardiomyocytes (39). In contrast to Shiraishi’s group’s findings, using ribosome profiling and a novel approach of ribosome pulldown coupled with nanopore RNA-seq (Nano-TRAP), RPL3L is found to modulate neither translational efficiency nor ribosome affinity towards a specific subset of mRNA transcripts. Interestingly, knockout of Rpl3l leads to enhanced ribosome–mitochondria interactions and a significant increase in mitochondrial activity and subsequent ATP synthesis in CMs. This study suggests that tissue-specific ribosome protein paralogues may not regulate the translation of specific mRNA transcripts. Alternatively, the presence or absence of RPL3L alters the expression of RPL3, which changes the subcellular localization of cytoplasmic ribosomes and modifies the mitochondrial activity. What factors cause the discrepancy between these two studies using similar approaches remains unclear. One of the most reproducible findings suggest that unrelated genetic deletion distinct from Rpl3l loss-of-function, such as conditional knockout of a cytosolic gene, glutamyl-prolyl-tRNA synthetase (Erps1), or a nuclear-encoded mitochondrial gene family with sequence similarity 210 member A (Fam210a) in CMs, caused heart failure and exhibited simultaneous increase in RPL3 and decrease in RPL3L mRNA and protein expression levels (22, 40). Cryo-electron microscopy visualization of RPL3- and RPL3L-bearing ribosome structures and comparative bioinformatic re-analysis of independent Ribo-seq data from both groups will provide critical insights into better deciphering the functional and mechanistic divergence between the two specialized ribosomes in the CMs.

A recent report from Molkentin's group showed that mouse cardiac ventricles express RPL3 during the neonatal stage (37). RPL3 is then replaced by RPL3L in adulthood but is re-expressed under cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling. This follows a similar expression pattern of the fetal gene program, such as the key transcription factors and sarcomere proteins. Intriguingly, Rpl3l−/− mice (CRISPR-Cas9 mediated deletion and frameshifting in the exon 5) showed no overt changes in cardiac structure or function at baseline or after transverse aortic constriction surgery-based, pressure overload-induced hypertrophy. Possibly, loss-of-function of RPL3L could be compensated by RPL3, as the expression of the latter was persistently upregulated in the adult heart (37). Transcriptomic profiling analysis and polysome profiling assay show little differences between Rpl3l knockout and wild-type control hearts from adult mice. Moreover, in adult Rpl3l knockout cardiomyocytes, no changes were found in cellular localization of the ribosome, cardiac tissue ultrastructure, or mitochondrial function compared to wild-type control cells. Adeno-associated virus-9 (AAV9)-mediated overexpression of either RPL3 or RPL3L in the hearts failed to cause pathogenesis in mice. Rpl3l null mice had significantly smaller hearts during cardiac aging than wild-type controls at 18 months after birth. Unlike the other two groups, Molkentin's lab demonstrates that Rpl3l knockout can be fully compensated by RPL3, although Rpl3l deletion leads to a slight but significant reduction in heart weight. More replicated studies are required to reproduce and confirm any of these findings because the different genetic knockout strategies from the three labs could partially contribute to the contradictory conclusions and distinct phenotypes and mechanisms. Ribo-seq mapping can provide detailed information about subtle changes in translation elongation dynamics that polysome-seq cannot. To resolve this controversy, genetic knock-in of the specific human mutation in the mouse genome must be performed to recapitulate the heart disease phenotype observed in human patients. If no spontaneous phenotype is triggered, it indicates the possibility of human mutations as an accompanying or modifier variant, which may not directly cause heart disease symptoms.

Intriguingly, a preprint manuscript from Wu’s lab provided further mechanistic insights into how PRL3L mutant proteins lead to dilated cardiomyopathy 2D (CMD2D; OMIM # 619371) due to a gain of toxic function in humans (41) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Translation machinery defects in early-onset human heart disease.

Figure 2.

Translation machinery defects in early-onset human heart disease.

They identified new, rare yet highly pathogenic heterozygous hotspot mutations D308V/N and G27D in the RPL3L gene. These mutations were co-initiated with known loss-of-function mutations (frameshift, missense mutation, alternative splicing) or low-pathogenic missense mutations. Despite carrying autosomal recessive alleles, such patients do not exhibit severe heart failure. The authors observed a decrease in 28S rRNA but not 18S rRNA in the tissue of these patients. Moreover, neither RPL3 mRNA nor protein levels were found to be upregulated as a compensatory response. To evaluate the impact of each mutation, the authors developed an AC16 human cardiomyocyte cell model with inducible RPL3 and different variants of RPL3L to assess the effect of each mutation. D308V/N and G27D variants of RPL3L showed a reduction in 28S rRNA and 60S ribosomal subunits, resulting in the loss of 80S monosomes and polysomes. Being heterozygous and recessive, the mutations confer a gain of toxic function rather than a loss of function. The D308V/N and G27D RPL3L proteins were detected solely in the nucleus. Interactome research revealed their interaction with proteins involved in 28S rRNA processing and 60S ribosome subunit biogenesis. The nuclear-localized mutant RPL3L exhibited the highest binding affinity with the ribosomal chaperones and biogenesis factors GRWD1 and C7ORF50, as indicated by HA-tagged RPL3L overexpression followed by immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry analysis. Thus, D308N and G27D proteins may sequester ribosomal biogenesis factors, ultimately diminishing overall translation. Additionally, the authors found that the R161W and T189M mutants of RPL3L induced a compensatory effect on RPL3, mirroring the upregulation of Rpl3 mRNA in the Rpl3l knockout mouse model. These two mutations enhance RPL3 mRNA stability but do not affect its transcription. However, the compensation from increased RPL3 was inadequate to rescue the failure caused by the gain-of-function mutation allele of RPL3L. Publicly available human genome sequencing databases reveal more than ten RPL3L homozygous knockout humans with no reported heart diseases. This supports the idea of a gain of toxic function of the RPL3L mutations. Noticeably, they used lentiviral overexpression of mutant RPL3L with shRPL3 knockdown in an immortalized human AC16 ventricular cardiomyocyte cell line fused with human fibroblast cells. This experimental system may not necessarily recapitulate the gene expression and protein localization in vivo in the human hearts. Genetic knock-in mouse model for the human RPL3L mutations and human iPSC-CM after maturation need to be exploited to validate their findings in the AC16 cell line. Also, the mechanism underlying this RPL3 mRNA stabilization by mutant RPL3L protein remains unclear and warrants future thorough biochemical characterization. As an example, a gain-of-toxic-function human mutation S637G in RBM20 (RNA binding motif protein 20) leads to mislocalization of this protein in the cytoplasm, formation of RBM20-ribonucleoprotein granules, thereby causing severe dilated cardiomyopathy via inhibiting mRNA translation most likely. The severe heart failure symptoms and high mortality rate are faithfully recapitulated in a Rbm20S639G knock-in mouse model, but not in the Rbm20 knockout model with a mild heart disease phenotype(42).

Unbiased animal genome- and transcriptome-wide associated studies (GAWS and TWAS) and subsequent expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL), as well as translation efficiency quantitative trait locus (teQTL) provide a complementary approach to human GWAS, TWAS, eQTL, and subsequent characterization of the causative genetic variants of diseases. One such study discovered a trans locus that causes ribosomopathy in hypertrophic hearts that modulates mRNA translation in a protein length-dependent manner using teQTL analysis in rats (43). This study investigated the influence of trans-acting genetic variation in distant genetic loci on the mRNA translation efficiency. It defined their contribution to developing complex disease phenotypes within a panel of rat inbred lines. One of the tissue-specific master regulatory loci, associated explicitly with hypertrophic hearts, drives a transcriptome-wide protein length-dependent regulation in mRNA translation efficiency, altering the stoichiometric translation rates of many sarcomeres protein-coding mRNAs. Mechanistically, significant differences in global polysome profiles and dysregulation of the small nucleolar RNA SNORA48 influence ribosome biogenesis and activity, leading to a translation machinery defect. Reproducible protein length-dependent shifts in translational efficiency were observed as an evolutionarily conserved trait of translation machinery mutants across multiple species from yeast to humans, including ribosomopathy-causing translation machinery component protein mutants. Mutations in different trans-acting factors can reduce or enhance a negative correlation between protein length and translation rates. This effect is potentially caused by transcript-specific translation initiation and re-initiation rate imbalances.

Another ribosome-related translation component is eukaryotic elongation factor 1A (eEF1A). eEF1A mediates aminoacyl-tRNA recruitment to the aminoacyl-tRNA site (A-site) of the eukaryotic cytoplasmic 80S ribosome. Therefore, eEF1A is crucial to the translation elongation process on mRNAs. Two different isoforms exist, eEF1A1 and eEF1A2, though antibodies to differentiate these isoforms have only recently become available. eEF1A1 is ubiquitously expressed through embryonic and neonatal mice and is then reduced and replaced by eEF1A2 in the heart, brain, spinal cord neurons, and skeletal muscle. Mice with a 15.8 kilobase deletion in the Eef1a2 gene have a “wasted” phenotype, experiencing muscle wasting, neurodegeneration, and death at postnatal day 28 (44). Humans with a Pro333-to-Leu mutation in the EEF1A2 gene have dilated cardiomyopathy, developmental delay, epilepsy, and early death (45) (Figure 2). Xmlc2-Cre+ driven cardiomyocyte-specific conditional knockout of Eef1a2 and knock-in of Pro333-to-Leu mutation in mice resulted in left ventricular chamber dilation and systolic dysfunction, followed by full penetrance of death at around 8-17 weeks (46), suggesting an essential role of eEF1A2 in heart development and functional maintenance. Like RPL3L and RPL3, it is crucial to dissect the functional redundancy and uniqueness between eEF1A1 and eEF1A2 as a future direction.

3.1.2. Human mutations in mitochondrial translation machinery lead to genetic cardiomyopathy

Numerous human mutations in mitochondrial translation machinery have been reported to cause spontaneous early-onset dilated or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. These cardiomyopathy-related mitochondrial translation machinery mutations include mitochondrial aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and tRNAs, translation factors, mitoribosomal proteins, and mitochondrial RNA-binding proteins (47). An illustration of this is a mutation in the mitochondrial alanyl-tRNA synthetase, AARS2, resulting in infant-onset cardiomyopathy (48-50) (Figure 2). This implies that AARS2-dependent translation is necessary for normal cardiac development. Another example of mitochondrial translation affecting cardiomyopathy was shown in experiments by Rudler et al (51). They generated a knockout mouse model of mtIF3, a mitochondrial translation initiation factor. A global knockout mouse model of Mtif3fl/fl with a global Cre transgene was embryonic lethal. In contrast, a heart and skeletal muscle knockout mouse model with Ckmm-Cre resulted in dilated cardiomyopathy. Evidence of mutations in mitochondrial translation elements resulting in cardiomyopathy highlights the importance of normal mitochondrial translation in maintaining mitochondrial integrity and cardiac function.

3.1.3. Loss-of-function of PRRC2B-mediated translation initiation regulation causes congenital cardiovascular defect in humans and mice

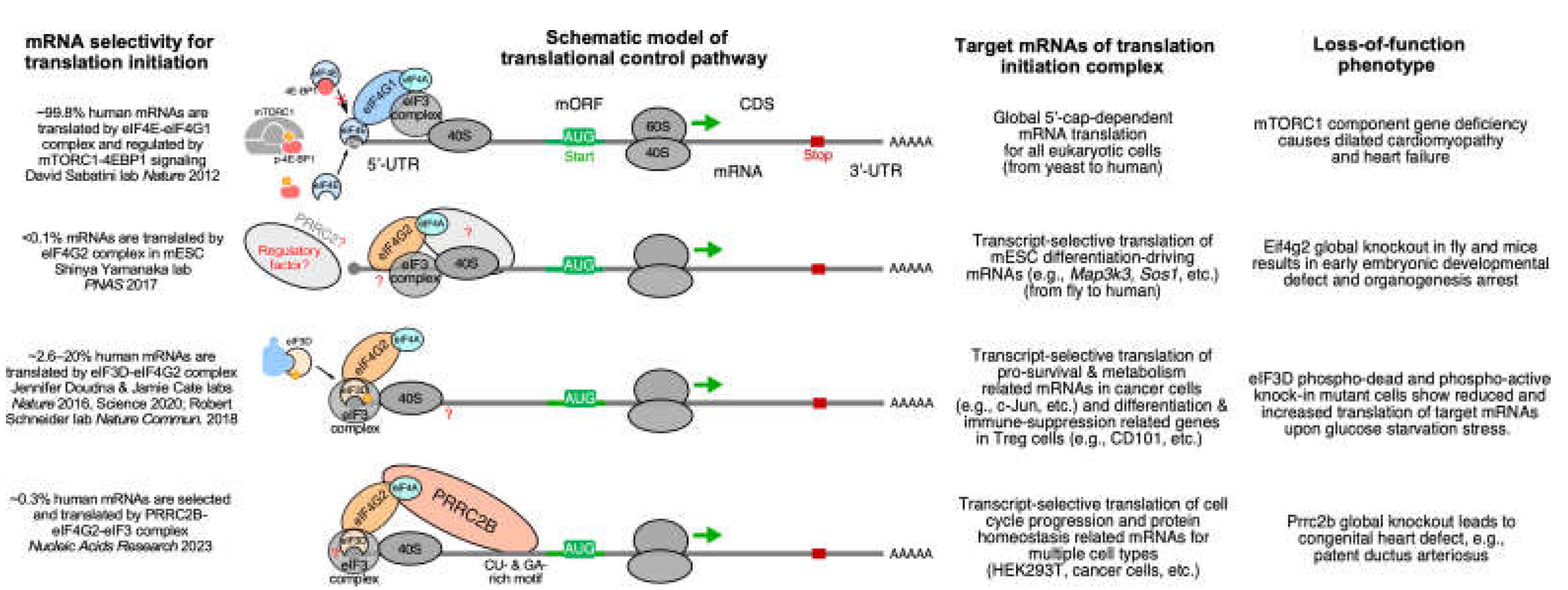

Posttranscriptional control of gene expression, including RNA splicing, transport, modification, translation, and degradation, is primarily mediated by RBPs and their interaction with target mRNAs (52). Recently, our group characterized the function of a novel RBP, Proline-rich coiled-coil 2B (PRRC2B) (13) (Figure 2). Transcriptome-wide CU- or GA-rich RNA regions were identified as PRRC2B binding sites near the translation initiation codon on a specific cohort of mRNAs by photoactivatable ribonucleoside-enhanced crosslinking and immunoprecipitation and sequencing (PAR-CLIP-seq) in human cells. These PRRC2B-bound mRNAs, including oncogenes, protein homeostasis-related factors, and cell cycle regulators such as cyclin D2 (CCND2), showed decreased translation efficiency upon inducible PRRC2B knockdown, leading to compromised G1/S phase transition and cell proliferation. Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) masking PRRC2B interacting sites within CCND2 mRNA 5' UTR reduced its translation and inhibited cell cycle progression and proliferation. Mechanistically, PRRC2B interacts with eukaryotic translation initiation factors 4G2 (eIF4G2) and eIF3 in an RNA-independent manner to form a ribonucleoprotein complex together with target mRNAs. The interaction between PRRC2B and eIF4G2 is essential for sufficient translation initiation of CCND2 mRNA. Therefore, PRRC2B is a critical translation regulatory factor for the efficient expression of a selective cohort of proteins (~0.3% of human genes) required for cell cycle progression and proliferation (Figure 3). We confirmed that the shRNA-mediated knockdown of PRRC2B inhibits the translation of a selective cohort of endogenous mRNAs in human cells, such as CCND2, among others (13). Interestingly, CCND2 protein was reported to promote the proliferation of cardiomyocytes when overexpressed in porcine hearts as a potential factor to enhance heart regeneration in large mammals (53), implying that PRRC2B might be involved in cardiomyocyte proliferation at the translational level. In line with this idea, Teleman’s group reported the critical role of PRRC2 family proteins, PRRC2A, PRRC2B, and PRRC2C, in the cell proliferation of human cancer cells (54).

Our recent work highlighted a novel function of PRRC2B associated with congenital heart disease (55). We identified two alternatively spliced isoforms of PRRC2B and confirmed their conservation in human and mouse hearts and HEK293T cell lines. Kimchi’s group recently reported the same alternative spliced isoforms in multiple additional human cancer cell lines, such as HeLa, HCT116, A549, among others (56). Interestingly, our in vivo exon-16-containing premature termination codon knock-in mouse model for full-length PRRC2B did not show any severe cardiac phenotype, suggesting a possible compensation either by the alternate spliced isoform (exclusion of exon 16, as termed ΔE16) or possibly by PRRC2A or PRRC2C. However, global knockout of both full-length and ΔE16 Prrc2b mRNA isoforms (genetic deletion of exon 4 shared by both isoforms) causes a high penetrance of neonatal lethality in mice by triggering patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), a genetic disorder with cardiovascular developmental defects observed in humans. Bulk and single-nucleus RNA-seq data identify a decrease in smooth muscle cell number and expression of smooth muscle-specific genes upon global Prrc2b deletion. Moreover, polysome-seq, RNA-seq, and mass spectrometry analysis from CRISPR-Cas9-mediated PRRC2B knockout HEK293T cells suggest a significant reduction of genes involved in cell proliferation, heart and vascular development, indicating a possible regulation of PRRC2B in vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and contraction. Two heterozygous loss-of-function mutations of the PRRC2B gene in patients with congenital heart disease are reported to manifest symptoms of pulmonary vein atresia and mitral regurgitation and stenosis, underscoring the connection between PRRC2B and cardiovascular development and disorders. Therefore, PRRC2B has been hypothesized to regulate protein translation of specific proteins in cardiac cells, such as smooth muscle cells, to maintain normal heart morphogenesis, and loss-of-function of PRRC2B causes aberrant gene expression and congenital heart defects. Our recent findings indicate that the knockdown of PRRC2B in primary human aorta-derived smooth muscle cells inhibited cell proliferation and migration (55) (Figure 3). PRRC2B is a promising RNA-binding protein that could be pivotal in cardiovascular disease development and a future therapeutic target.

Figure 3.

eIF4G2-PRRC2B complex-mediated translation initiation regulatory pathway for cell proliferation and cardiac developmental integrity. Bottom row compared to eIF4G1-eIF4E-driven, cap-dependent canonical translation initiation (top row), eIF4G2-mediated cap-independent (second row), and eIF3D-mediated cap-dependent (third row) noncanonical translation initiation pathways.

Figure 3.

eIF4G2-PRRC2B complex-mediated translation initiation regulatory pathway for cell proliferation and cardiac developmental integrity. Bottom row compared to eIF4G1-eIF4E-driven, cap-dependent canonical translation initiation (top row), eIF4G2-mediated cap-independent (second row), and eIF3D-mediated cap-dependent (third row) noncanonical translation initiation pathways.

3.1.4. eIF4E1C regulates cardiomyocyte metabolism and proliferation during heart regeneration in zebrafish

In eukaryotes, the eIF4E family of translation initiation factors, such as canonical eIF4E1A, bind 5' methylated guanosine caps of mRNAs as a limiting step for mRNA translation. Another family member, eIF4E1C, present in aquatic vertebrates but lost in terrestrial species, plays a vital role during cardiac development and heart regeneration in zebrafish (57). eIF4E1C is broadly expressed across multiple cell types and organs in fish. Genetic deletion of the eif4e1c gene in zebrafish caused growth defects and reduced juvenile survival. The knockout zebrafish surviving to adulthood had a significantly decreased number of cardiomyocytes and compromised proliferation in response to cardiac injury compared to wild-type controls. Translatome-wide Ribo-seq analysis of eif4e1c-null hearts reveals changes in the translation efficiency of mRNAs encoding proteins that regulate cardiomyocyte cell proliferation. Disruption of eIF4E1C function in the mutant fish had the most pronounced impact on the heart at juvenile stages. This suggests a specialized requirement for fine-tuning the control of translation initiation via a unique eIF4E paralog for heart regeneration and development in fish. Identifying a similar translation factor and regulatory mechanism in terrestrial species (e.g., mammals) is the key to generalizing this concept in evolution.

3.2. Translational control in mitochondrial cardiomyopathy

Many genetic mutations have been reported in the genes encoding mitochondrial translation machinery that cause spontaneous cardiomyopathy with mitochondrial dysfunction, including mitochondrial aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and tRNAs, mitochondrial translation initiation and elongation factors, mitoribosome proteins, and other translation regulatory factors or RNA-binding proteins localized in the mitochondria (47). Persistent activation of an evolutionarily conserved central cytosolic translational control pathway, namely, integrated stress response (ISR), is considered a common shared feature with multiple types of mitochondrial cardiomyopathy and other mitochondrial dysfunction-related diseases caused by these mitochondrial protein-coding gene mutations (58, 59).

Translational regulation inside mitochondria is still underexplored, and more research is needed to discover novel therapeutic targets in the translational process to treat mitochondrial diseases. Prior genome-wide association studies in humans revealed that FAM210A (family with sequence similarity 210 member A) gene mutations were associated with skeletal muscle disorder and bone fractures (60, 61). We recently showed that the Fam210a cardiomyocyte-specific genetic knockout mouse model exhibited progressive mitochondrial cardiomyopathy and heart failure (62). Multi-omics analyses, including RNA-seq, Ribo-seq, proteomic mass spectrometry, and metabolomics, revealed a reduction of mitochondrial encoded mRNA translation elongation and consequent activation of ISR in Fam210a knockout hearts. Chronic and persistent ISR activation inhibits cap-dependent translation initiation in the cytoplasm, leading to translational reprogramming and disrupted protein homeostasis. Interestingly, FAM210A protein expression is reduced in diseased hearts from ischemic heart failure patients and mice with myocardial infarction surgery. This discovery demonstrates a novel crosstalk mechanism between mitochondrial and cytosolic translation processes via FAM210A-mediated regulation of mitochondrial translation elongation. Ribo-seq proved that mitochondrial translation elongation is compromised upon genetic knockout of Fam210a in cardiomyocytes in mice, as indicated by increased ribosome footprints of mRNAs transcribed from mitochondrial-encoded genes. Adeno-associated virus (AAV9)-mediated overexpression of FAM210A can significantly enhance mitochondrial translation and protect the heart from ischemia stress-induced cardiac dysfunction (62) as a potential gene therapy (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

FAM210A-EF-Tu complex regulates mitochondrial translation elongation and cardiac mitochondrial homeostasis in hypertensive cardiomyopathy and ischemic heart failure. Left panel: miR-574-5p and miR-574-3p downregulate FAM210A expression and limit cardiac hypertrophy in transverse aortic constriction-induced hypertensive cardiomyopathy. Right panel: FAM210A expression is reduced in left anterior descending coronary artery ligation-induced myocardial infarction, leading to pronounced mitochondrial dysfunction and contributing to heart failure.

Figure 4.

FAM210A-EF-Tu complex regulates mitochondrial translation elongation and cardiac mitochondrial homeostasis in hypertensive cardiomyopathy and ischemic heart failure. Left panel: miR-574-5p and miR-574-3p downregulate FAM210A expression and limit cardiac hypertrophy in transverse aortic constriction-induced hypertensive cardiomyopathy. Right panel: FAM210A expression is reduced in left anterior descending coronary artery ligation-induced myocardial infarction, leading to pronounced mitochondrial dysfunction and contributing to heart failure.

Following a prior miRNA expression screen for MI models (63), we identified mammalian miR-574 (including guide and passenger strands miR-574-5p and miR-574-3p) as involved in cardiac hypertrophy and pathological remodeling. We discovered that dual-strand miRNAs, miR-574-5p and miR-574-3p, are induced in human and mouse non-ischemic failing hearts compared to healthy hearts. Using the miR-574 genetic knockout mouse model and RNA-seq, we found that miR-574-5p and miR-574-3p target Fam210a mRNA in mouse cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts, thereby maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis and preventing cardiac hypertrophy and ventricular remodeling in a pressure overload-induced hypertensive cardiomyopathy model (64). This work demonstrates that the miR-574-FAM210A axis regulates mitochondrial translation for maintaining optimal expression of mitochondrial electron transport chain complex genes in non-ischemic heart disease (64) (Figure 4). More importantly, miR-574 delivered in the hypertensive cardiomyopathy mouse models via nanoparticles can be a potential therapeutic tool for antagonizing cardiac pathological remodeling (64). Based on these findings, we proposed “normalizing” mitochondrial translation to maintain the homeostatic balance with cytosolic translation to protect the heart from progressive pathological remodeling and heart failure.

To characterize the biochemical and biophysical properties, the protein structure of FAM210A and its complex with EF-Tu or other interacting partners needs to be resolved. This was highly challenging as FAM210A is a mitochondrial transmembrane protein. We overexpressed human FAM210A with a truncated mitochondria-targeting signal peptide at the N-terminus in bacteria and purified the recombinant protein from E. coli (65). Interestingly, bacteria-derived translation elongation factor EF-Tu is co-purified with human FAM210A, which recapitulates the formation of FAM210A-EF-Tu complex in cardiac mitochondria as seen by immunoprecipitation-mass spectrometry (64). Consistently, recombinant human FAM210A protein is localized in the plasma membrane of E. coli, like the localization in the inner mitochondrial membrane in CMs.

3.3. Translational regulation of cardiac cell proliferation and differentiation

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the leading cause of birth defect-related death and can lead to severe adult heart disease, such as heart failure. The severity of CHD emphasizes the importance of the normal developmental program of the cardiovascular system, which depends on precise spatial and temporal control of the expression of genes encoding structural proteins, transcription factors, and cell cycle-related proteins. The gene expression programs of developing organs are established at both transcription and translation levels at the early stages of embryonic development. Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms are well-known for initiating and arranging developmental time courses for organogenesis. It is well-established that multiple transcription factors and cell cycle-related proteins control the development of the cardiovascular system (66-69). However, the regulatory mechanism upstream of these factors at the translational level remains largely unexplored. Translational regulation is competent for determining the fate of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) towards cardiac differentiation by a specific mRNA translation regulatory pathway directed by RBPMS (RNA binding protein with multiple splicing) (70). Under cardiac cell differentiation conditions, RBPMS is associated with actively translating ribosomes in hESCs to activate the translation of a specific cohort of key factors required for initiating a cardiac commitment program, such as the Wingless/Integrated (WNT) signaling. As a result, the loss-of-function of RBPMS profoundly impairs cardiac mesoderm specification, thereby leading to profound morphogenetic and tissue patterning defects in cultured human cardiac organoids. RBPMS acts in translational control via two separate and related molecular mechanisms, including selectively binding to the 3'-UTR of specific target mRNAs and globally promoting translation initiation for enhancing protein synthesis. RBPMS depletion leads to inhibition of translation initiation, indicated by abnormal eIF3 complex retention and eIF5A drop-off on mRNAs, thereby blocking ribosome recruitment and elongation during protein synthesis.

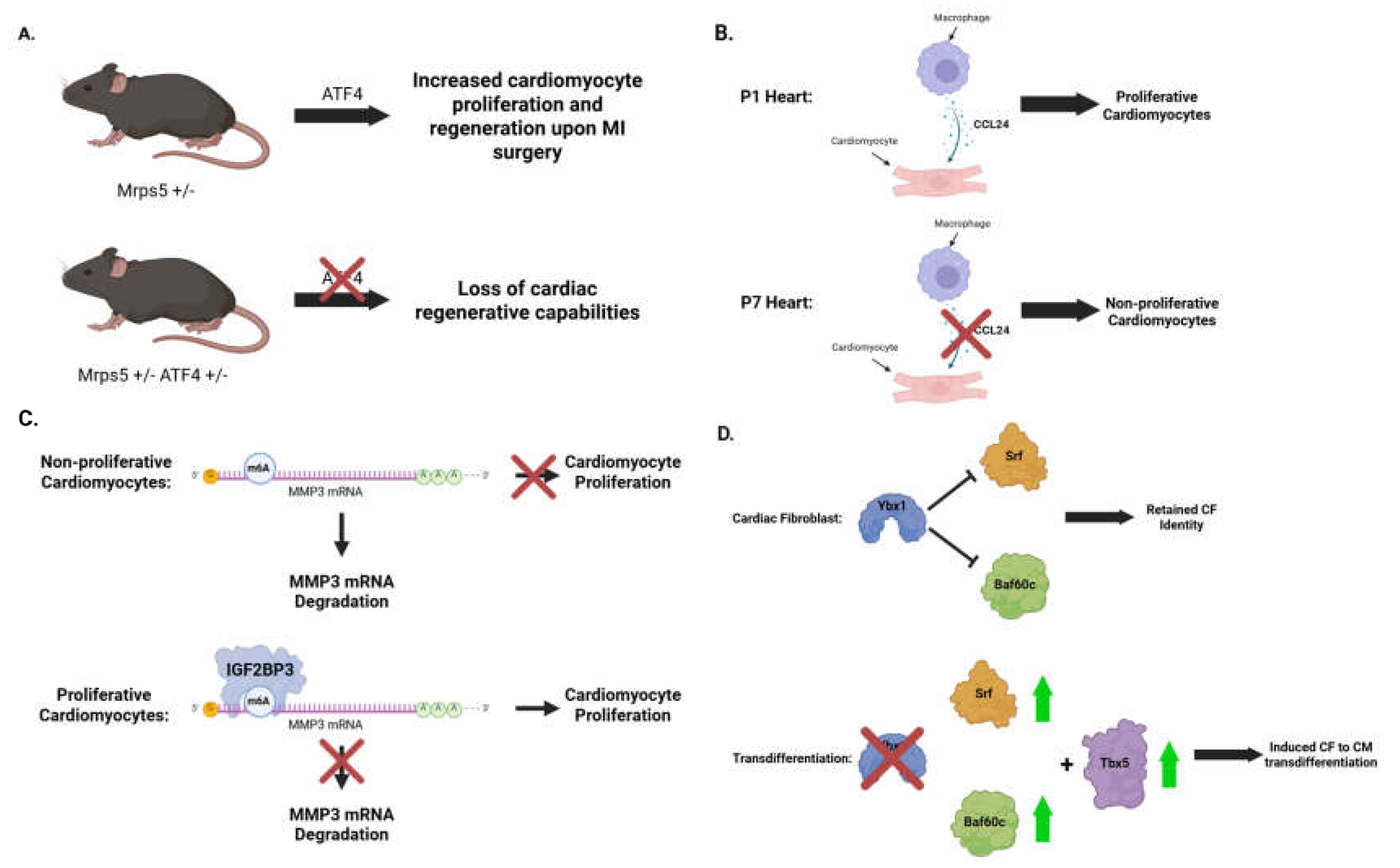

Mitochondria play essential roles in maintaining normal cardiac function and preventing heart disease. Generally, reduced mitochondrial translation causes a mitochondrial-nuclear proteomic imbalance and leads to changes in the activity of the electron-transporter chain complex. Intriguingly, deleting a single allele of mitochondrial small ribosomal subunit protein 5 (Mrps5) in mice enhances cardiomyocyte proliferation and cardiac regeneration in a surgical myocardial infarction mouse model (71) (Figure 5A). Cardiac function after MI surgery is significantly improved in mice with haploinsufficiency of Mrps5. Activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) is a critical regulator of the mitochondrial stress response in cardiomyocytes from heterozygous Mrps5 knockout mice. Mechanistically, ATF4 regulates KNL1 (kinetochore scaffold 1) expression, increasing cytokinesis during cardiomyocyte proliferation. Doxycycline-mediated inhibition of mitochondrial translation counterintuitively promoted cardiomyocyte proliferation. Cardiomyocyte proliferation of Mrps5+/− can be attenuated when one allele of Atf4 is also genetically deleted (Mrps5+/− Atf4+/−), resulting in a loss of the cardiac regenerative capacity. MRPS5 reduction and doxycycline treatment activate an evolutionarily conserved regulatory mechanism that increases the proliferation of human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSC)-derived cardiomyocytes, providing a new approach for treating cardiac injury and activating heart regeneration.

Figure 5.

Translational regulatory mechanisms driving cardiomyocyte proliferation and cardiac fibroblast-to-myocyte transdifferentiation. A. Mild mitochondrial translational defects activate integrated stress response and cardiomyocyte proliferation. B. Paracrine secretion of CCL24 from macrophages stimulates cardiomyocyte proliferation. C. The molecular mechanism of IGF2BP3-mediated binding and stabilization of m6A-modified MMP3 mRNA contributes to cardiomyocyte proliferation. D. Loss-of-function of YBX1 promotes cardiac fibroblast-to-myocyte transdifferentiation with TBX5 overexpression.

Figure 5.

Translational regulatory mechanisms driving cardiomyocyte proliferation and cardiac fibroblast-to-myocyte transdifferentiation. A. Mild mitochondrial translational defects activate integrated stress response and cardiomyocyte proliferation. B. Paracrine secretion of CCL24 from macrophages stimulates cardiomyocyte proliferation. C. The molecular mechanism of IGF2BP3-mediated binding and stabilization of m6A-modified MMP3 mRNA contributes to cardiomyocyte proliferation. D. Loss-of-function of YBX1 promotes cardiac fibroblast-to-myocyte transdifferentiation with TBX5 overexpression.

In addition to the stoichiometry of ribosome proteins influencing cardiomyocyte proliferation, the posttranslational modifications contribute to cardiomyocyte differentiation. 2-oxoglutarate and iron-dependent oxygenase domain-containing protein 1 (OGFOD1), a ribosomal prolyl-hydroxylase, catalyzes the posttranslational hydroxylation of proline 62 in the small ribosomal protein S23 (RPS23). Genetic deletion of OGFOD1 in an in vitro cell culture model of human cardiomyocytes decreases the translation of specific proteins, such as RNA-binding proteins, which may, in turn, regulate translation and alternative splicing as a secondary effect (72). Loss of OGFOD1 causes alterations in protein translation and reprograms the cardiac proteome, thereby increasing the synthesis of sarcomere proteins, including cardiac troponins, titin, and cardiac myosin-binding protein C. Consistent with these translational changes, OGFOD1 expression is reduced during cardiomyocyte differentiation.

Mammalian cardiomyocytes exit the cell cycle shortly after birth. The adult heart cannot regenerate in response to injury, whereas the neonatal heart can efficiently regenerate following MI surgery, but this capacity is lost by postnatal day (P)7 (73). RNA-seq analysis for regenerative (P1) and nonregenerative (P8) mouse hearts after MI surgery revealed that the transcriptome of post-MI regenerative hearts reverts rapidly to a baseline pattern compared to uninjured control hearts. In contrast, post-MI nonregenerative hearts exhibited a distinct gene expression pattern (74). Integrated with active chromatin landscapes, genes and biological processes activated in injured hearts were identified, among which the immune response and embryonic developmental gene programs were strikingly divergent between regenerative and nonregenerative hearts. The macrophage-mediated innate immune response has been reported to play a critical role in neonatal heart regeneration (75). Acute activation of immune-related genes in regenerative hearts is evident through the deposition of histone H3 lysine-27 acetylation (H3K27ac), which marks active enhancers and promoters, serving as key steps in triggering regeneration; notably, the injury-induced immune factor CCL24 secreted from P1 macrophages promoted CM proliferation during neonatal heart regeneration (Figure 5B). Moreover, the regenerative P1 heart retained developmental and cell-cycle gene programs, within which an RNA-binding protein, IGF2BP3 (insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein), was identified to promote CM proliferation and restore cardiac morphology and function after MI, possibly driven by translational activation of CM regenerative factor mRNAs such as IGF2 (insulin-like growth factor 2) through the binding of 3'-UTR.

Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying the reactivation of CM proliferation and heart regeneration is essential for inducing cardiac repair in response to injury. IGF2BP3 belongs to a family of N6-methyladenosine (m6A) readers that recognize the consensus GG(m6A)C sequence and promote the stability of thousands of m6A-modified mRNA targets (76). IGF2BP3 expression progressively declines in mouse hearts during postnatal development and is nearly undetectable by P28. While MI induces IGF2BP3 upregulation in neonatal hearts, its expression remains barely detectable in adult hearts (77). Overexpression of IG2BP3 in P7 CMs promotes mitosis and cell-cycle progression, while IGF2BP3 knockdown decreases CM proliferation (Figure 5C). In vivo, adeno-associated virus AAV9-mediated IGF2BP3 overexpression in the left ventricular myocardium of P1 mice, followed by MI surgery, increases proliferative CMs and results in improved cardiac hypertrophy, reduced myocardial infarction size, decreased myocardial fibrosis, and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Among the most enriched mRNAs pulled down by IGF2BP3, MMP3 mRNA was identified as a target of IGF2BP3-mediated post-translational regulation. Mechanistically, the KH3 and KH4 domains of IGF2BP3 directly bind to the MMP3 mRNA and stabilize it through m6A modification, increasing MMP3 protein translation. Functionally, MMP3 acts as a downstream target of IGF2BP3 to promote heart regeneration and improve cardiac function after myocardial infarction.

Cardiomyocytes lose their proliferative ability shortly after their differentiation and maturation. This does not allow an adult mammal heart to regenerate after damage. Heart-specific triggers and pathways responsible for proliferation remain enigmatic. Understanding the mRNA expression signature in proliferating cardiomyocytes is one of the keys to studying heart regeneration. A recent unbiased comparative study used artificial intelligence (AI)-based tools to find such signatures among two pre-existing in vivo (mice and pigs) and one in vitro (human induced pluripotent stem cell-to-cardiomyocyte, hiPSC-CM) proliferating CM model. In vivo mouse and pig models provide single-nucleus (sn)RNA-seq on different days after induced MI. MI was also performed on P28 in pigs alone or combined with another apical resection surgery on P1. The in vitro model includes bulk RNA-seq of the hiPSC-CM cells on different days after differentiation. The AI tool identifies clusters of proliferative cells based on RNA-seq analysis of hiPSC-CM 16 days after differentiation, when these cells maintain their proliferative ability, compared to hiPSC-CM 140 days after differentiation, when cells stop proliferating. Upregulated and downregulated mRNA for each model and each cluster were found. Many upregulated genes are related to mitochondrial metabolism, protein biosynthesis, and mRNA modifications or processing. The investigators identified twenty-one overlapping up-regulated genes among all models across three species. Nine coded proteins are associated with ribosomes, including a well-established CM regenerative factor IGF2BP3, HSPA5, DHX9, and BLM, among others. Three genes code classic RNA-binding proteins (DHX9, PTBP3, and IGF2BP3); others are metabolic enzymes, cytoskeleton maintenance, and heat shock proteins, which have been identified as noncanonical RBPs (78). Immunohistochemistry in hiPSC-CM proved overexpression of multiple proteins in pig hearts with proliferating CMs, such as PTBP3, DHX9, DDX6, and HNRNPUL1.

In addition to hESC/hiPSC-CM differentiation and reactivating cardiomyocyte proliferation, direct reprogramming of cardiac fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes (iCMs) is another promising strategy for heart regeneration (79, 80). Recent studies reveal new insights into the translational landscape underlying the CF-to-iCM trans-differentiation and reprogramming process through integrative translatomic and transcriptomic profiling (81). A gene-specific targeted loss-of-function screening for translational regulatory factors identified an RNA-binding protein, Y-box binding protein 1 (YBX1), as a critical barrier to iCM trans-differentiation (Figure 5D). In a mouse myocardial infarction-induced heart failure model, reducing Ybx1 expression enhanced CF-to-iCM reprogramming efficiency in vivo, resulting in improved cardiac function and decreased fibrosis and scar size. Ybx1 removal activates the translation of its direct mRNA targets Srf and Baf60c, which directs the effect of Ybx1 depletion on facilitating iCM induction. Depletion of Ybx1 combined with overexpression of a single transcription factor, Tbx5, is sufficient in mediating CF-to-iCM conversion. This strategy simplifies the well-established overexpression of the transcription factor “cocktail”, including GATA4, MEF2C, and TBX5, with a specific stoichiometric ratio (82).

4. Translational Control in Adult Cardiac Disease

4.1. Translational control in cardiomyocyte hypertrophy

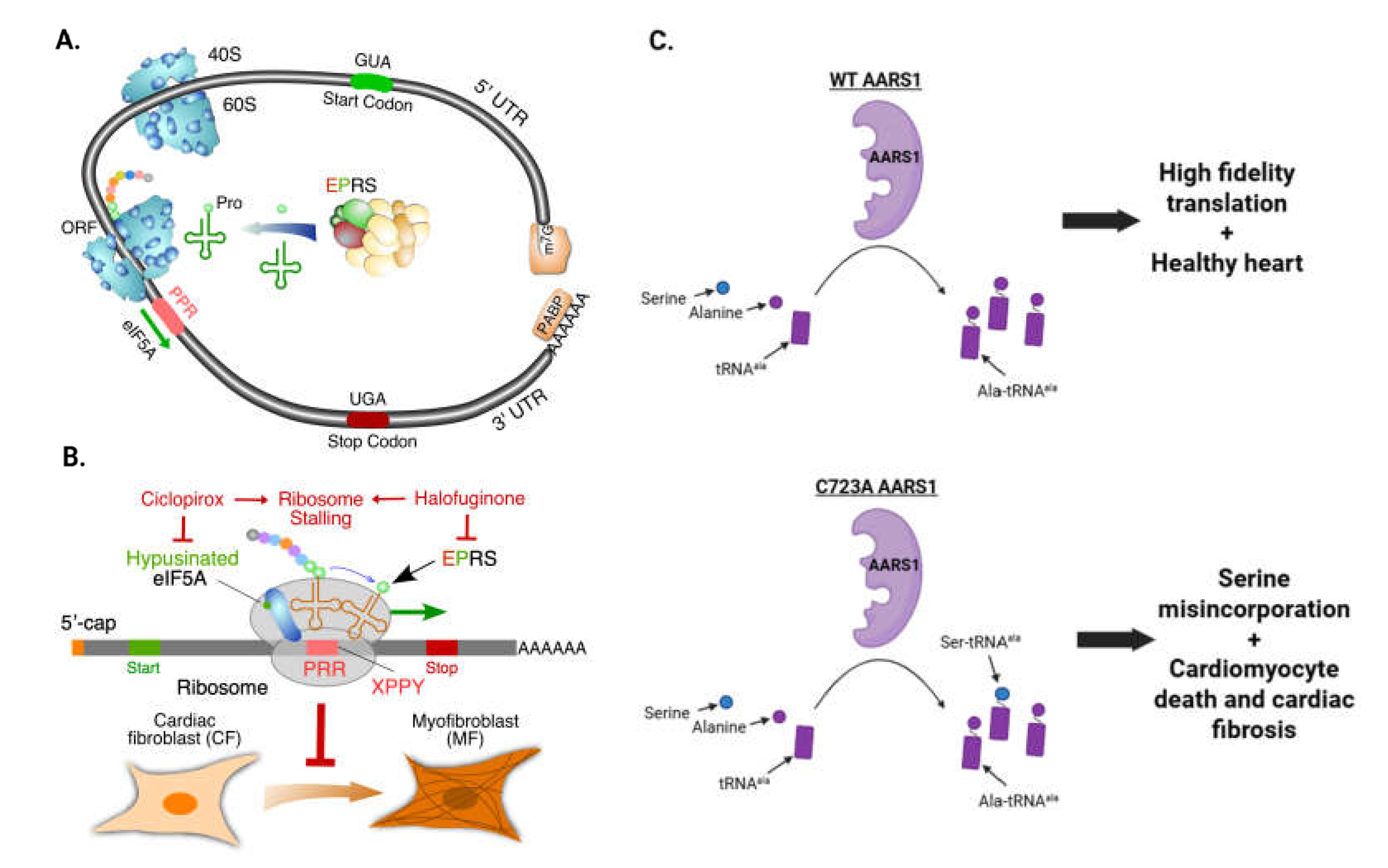

The human translation machinery is comprised of three main parts: ribosomes (ribosome proteins: RPs; ribosome RNA [rRNA]), translation factors (initiation and elongation factors), and ARSs and substrate transfer RNAs (tRNAs) (83) (Figure 1). Elevated global mRNA translation and protein synthesis are common features in cardiac hypertrophy (84-86). Hypertrophic stimuli activate mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) signaling (87-89), which promotes the synthesis of ribosome proteins and activation of translation factors (90). In hypertrophic CMs, ribosome proteins and rRNAs are markedly increased to support the increase of protein mass and CM size (84, 91-93). Therefore, both the capacity and efficiency of translation are increased in response to hypertrophic stimuli. A few specific translation factors required for cardiac hypertrophy have been defined.

4.1.1. Role of translation initiation factors in cardiac hypertrophy

Theoretically, translation efficiency can be regulated in three steps (i.e., initiation, elongation, and termination). In mammals, translation initiation is a critical control point in most cellular responses (94). Translation initiation is the process in which the assembly of elongation-competent 80S ribosomes occurs at the initiation codon, allowing further elongation to synthesize a full-length protein. Generally, the initiation process comprises two steps: forming 48S initiation complexes and joining 48S complexes with 60S large ribosomal subunits. Translation initiation happens canonically at the 5' end of mRNAs harboring a 7-methylguanosine (m7G) cap, i.e., cap-dependent translation initiation, which requires the cooperation of multiple translation initiation factors (94, 95) (Figure 3). Alterations in translation initiation are a crucial feature of cancer, viral infection, and cardiac hypertrophy (96-98).

The changes in protein synthesis rate in cardiomyocytes during stress-induced cardiac hypertrophy have been shown to correlate with changes in the activity of translation initiation factors, which modulate the rate of translation initiation (99-101). For instance, the activity of translation initiation factor eIF4E is increased upon hypertrophic stimuli in cardiomyocytes in a pressure overload model (98, 102) (Figure 6A). eIF4E is one component of the eIF4F complex that interacts with the m7G cap. When activated, eIF4E facilitates loading the 43S initiation complex onto mRNA to form 48S initiation complexes and promotes ribosome scanning in the 5'-UTR. The activity of eIF4E depends on its phosphorylation (103) (Figure 3). Expression of eIF3E has been shown to increase during both electrical pacing- or α1-adrenoceptor-induced hypertrophy of quiescent neonatal rat CMs (102). Phosphorylation of eIF4E is increased in adult feline CMs in culture during electrical pacing and in canine CMs in vivo after imposition of pressure overload (98). An increase in translation efficiency was concomitant with an increase in eIF4E phosphorylation in hypertrophied CMs in vivo (101). Overexpression of an inactive form of eIF4E slows down protein synthesis and reduces CM hypertrophy (104). However, increased expression or phosphorylation of eIF4E alone cannot induce hypertrophy in non-stimulated CMs (104). Thus, increased eIF4E activity is required for the accelerated rate of protein synthesis upon pressure overload, but increased eIF4E activity alone is insufficient for hypertrophy.

Besides eIF4E, modulated eIF2 activity has also been found after hypertrophic stimuli and other cardiovascular stress conditions (59, 105, 106). eIF2 is essential for forming the eIF2-GTP-Met-tRNAMet ternary complex during translation initiation. It cycles between GTP-bound active and GDP-bound inactive forms through phosphorylation. Phosphorylation of eIF2 locks eIF2 in the GDP-bound inactive form, reducing translation initiation (107). Glycogen synthase kinase 3b (GSK-3β), a kinase for eIF2Bε-S535 phosphorylation, is inhibited in isoproterenol-induced hypertrophied neonatal rat CMs, resulting in decreased eIF2 phosphorylation and accelerated translation initiation. Decreases in eIF2Bε-S535 phosphorylation were also observed in a rat model of cardiac hypertrophy in vivo (105). Overexpression of a consistently phosphor-active eIF2Bε mutant causes hypertrophy growth like isoproterenol treatment. In contrast, a phosphor-inactive eIF2Bε mutant blocks the effect of isoproterenol treatment (105). Therefore, unlike eIF4E, activated eIF2 alone is sufficient to cause CM hypertrophy (Figure 6B). Furthermore, the modulation of phosphorylation of eIF2α has also been found to be related to cardiovascular stress (59, 106). Gcn2−/− mice lacking a key eIF2α kinase were less prone to ventricular dysfunction, myocardial apoptosis, and fibrosis when subjected to transverse aortic constriction (106). A dephosphorylation inhibitor, salubrinal, has been shown to attenuate pressure-overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy (108). Although modulation of translation initiation factor activity correlates with cardiac disease, the global effect and high conservation of these factors among different cell types make it difficult to propose a treatment specific to cardiac disease without affecting other essential biological processes.

In addition to the translation initiation rate, the fidelity of translation initiation is also associated with cardiac function and disease (51). An example of this comes from mitochondrial translation, which synthesizes 13 essential electron transport chain complex component proteins to assemble the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) system required for energy production. One mitochondrial translation initiation factor, MTIF3, is required for molecular proofreading during the mitochondrial translation process. Loss of MTIF3 will increase the protein synthesis rate at the expense of reduced translation initiation fidelity, resulting in uncoordinated translation of the electron transport chain complex proteins, reducing the correct assembly of the OXPHOS system and ATP production (51). Heart-specific depletion of MTIF3 in mice causes spontaneous dilated cardiomyopathy, probably because of mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiac cells (51).

Apart from the canonical cap-dependent initiation, translation initiation can also happen in an alternative manner at internal ribosome entry sites (IRES) (109, 110). Cap-independent translation initiation is associated with many diseases, including cardiac diseases (109, 111, 112). One example of an IRES is Connexin 43 (Cx43) and its truncated isoform GJA1-20k (113, 114). Cx43 is the most widely expressed gap junction protein translated from an IRES in the 5' uORF (115) , while GJA1-20k is a truncated protein isoform generated from an IRES within the mORF of Cx43 (114). Levels of GJA1-20k regulate the formation of Cx43 gap junctions, which in cardiomyocytes are necessary for the electrical conduction that facilitates heartbeat (111). The IRES activity of GJA1-20k is increased in response to hypoxic conditions in cardiomyocytes (114). Ectopic expression of GJA1-20k has been found to rescue gap junction loss during acute ischemia, proving that modulating alternative translation initiation may protect against loss of electrical coupling, particularly in heart disease (111). Translation of GJA1-20k may be more complicated than “normal” IRES-driven translation since the evidence shows that m7G cap and ribosome scanning are also required (116). The non-canonical translation initiation of GJA1-20k exemplifies the role of alternative translation initiation related to cardiac disease. The mechanism needs to be elucidated regarding regulating the stoichiometric ratio of GJA1-20k to the full-length GJA1 at the translational level under baseline and cardiac stress conditions.

4.1.2. Role of translation elongation factors in cardiac hypertrophy

Although translation initiation has been established as the primary step for translational regulation (94), it is not surprising that translation elongation is also highly regulated since it is the most energy-consuming step during protein synthesis (117). Translation elongation is the process by which ribosomes decode mRNAs by bringing in the proper amino acids carried by aminoacyl-transfer RNAs (aa-tRNA) to form peptides (Figure 1). This process includes the selection of aa-tRNA according to mRNA codon in the ribosome aminoacyl (A) site, peptide bond formation, and movement of both tRNAs and the mRNA through the ribosome (118). A complex set of factors individually or cooperatively affects either the rate or the precision of translation elongation (117). The translation elongation step is affected by modification, abundance, and aminoacylation status of tRNAs, as well as the activity of elongation factors (117). Understanding the regulation of translation elongation is essential since it has been established that dysregulation of elongation is related to human disease (e.g., heart disease (119), tumors (120), neurodegeneration (121)). Evidence showing the correlation between the regulation of translation elongation and cardiac disease is seen by changes in the phosphorylation status of the eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2) induced by hypertrophic stimuli (122-125) (Figure 6B). eEF2 is a GTPase catalyzing the GTP-dependent ribosome translocation step during translation elongation. eEF2 enters the A-site and induces a conformational change of the ribosome through GTP hydrolysis, allowing the newly formed A-site-bound peptidyl-tRNA and P-site-bound deacylated tRNA to move to the P and E sites. The ribosome can then recruit a new aminoacyl-tRNA into the A-site and continue peptide elongation (126). The activity of eEF2 largely depends on its phosphorylation status (126). Dephosphorylated eEF2 results in eEF2 activation and increases elongation rate, while phosphorylation of eEF2 at Thr56 blocks translation elongation (123). The growth rate of CMs also correlates closely with eEF2 phosphorylation (122). Hypertrophic growth of neonatal CMs induced by angiotensin II is associated with mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent decreases in eEF2 phosphorylation (123). Decreased eEF2 can be detected within 30 minutes after angiotensin II treatment in isolated neonatal CMs, together with increased protein synthesis, which is believed to be one of the primary causes of cardiac hypertrophy (123). Other hypertrophic agonists, including endothelin-1, phenylephrine, and insulin, are also reported to facilitate dephosphorylation of eEF2 in CMs (124), suggesting that hypertrophy correlates with increased translation elongation caused by eEF2 phosphorylation. However, in another model where isoproterenol was used to induce hypertrophy in isolated adult rat ventricular myocytes, increased eEF2 phosphorylation was observed as early as 1 minute after isoproterenol treatment and remained elevated for 20 minutes (125). The inconsistent results of different models indicate the possibility that modulation of translation elongation during hypertrophy is complex. Isolated pharmaceutical hypertrophy models in vitro may not reflect what happens in vivo. In vivo mouse studies have shown that changes in eEF2 phosphorylation remain undetectable 1 week after isoproterenol injection into adult mice, while eEF2 phosphorylation is significantly increased after transverse aortic constriction surgery (122).