Submitted:

27 June 2025

Posted:

27 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

γδ T Cell Characteristics and Functions

Human γδ T Cells in GBM

Anti-Tumoral Role of γδ T Cells in GBM

Pro-Tumoral Role of γδ T Cells in GBM

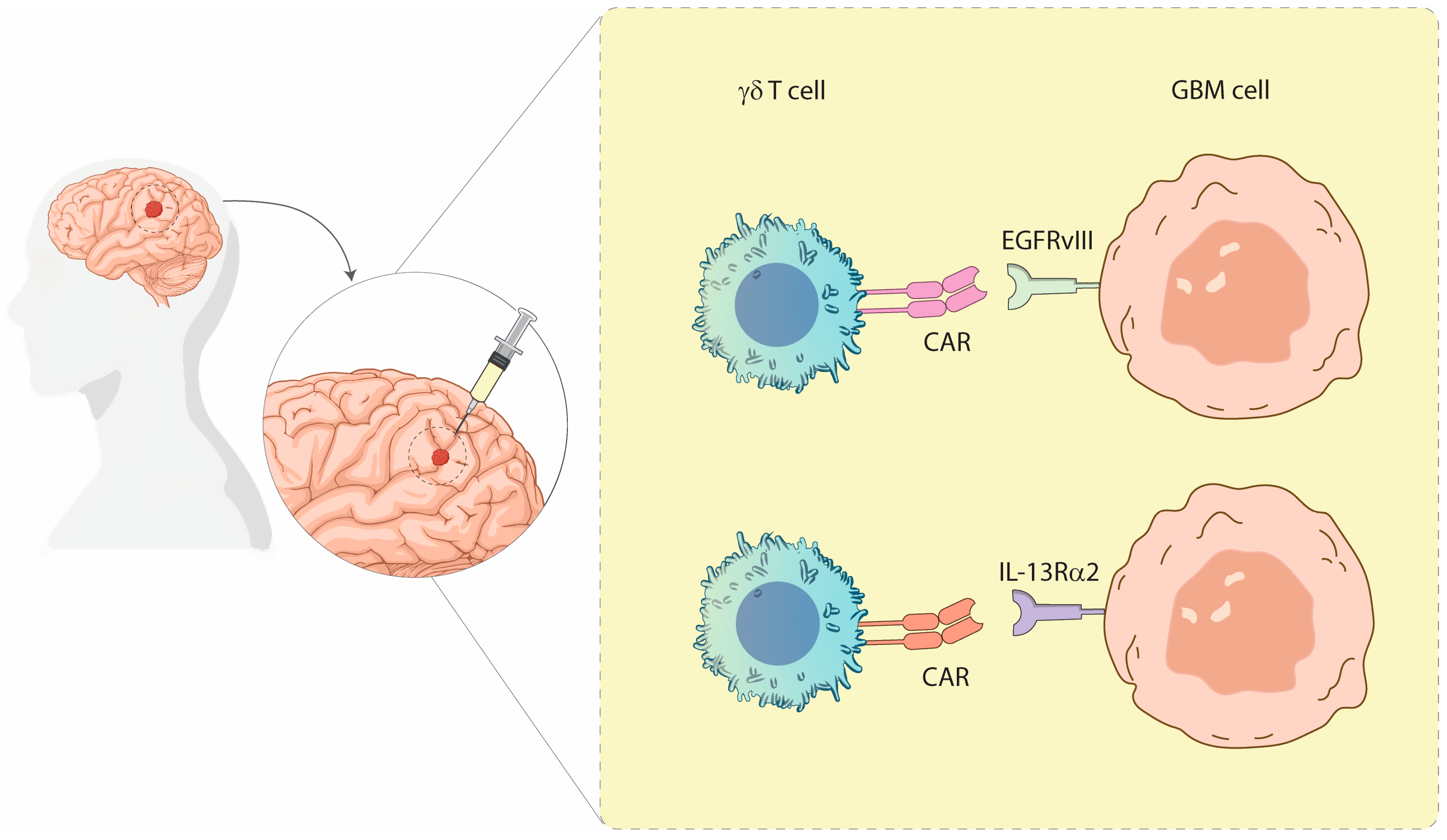

γδ T Cells in Cancer Immunotherapy

- Exhaustion: Repeated stimulation or chronic activation can lead to functional exhaustion, which reduces efficacy over time [53].

- Off-Target Effects: The MHC-independent recognition of antigens raises concerns about potential off-tumor cytotoxicity [54].

- Tumor Heterogeneity: Variability in the expression of stress-induced antigens across tumors may limit the applicability of γδ T cell therapies [49].

- Expansion Variability: Ex vivo expansion protocols often yield inconsistent results, which can impact the scalability and reproducibility of therapies [50].

γδ T Cells in GBM Immunotherapy

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GBM | Glioblastoma Multiforme |

| TMZ | Temozolomide |

| TME | Tumor Microenvironment |

| TAMs | Tumor-associated macrophages |

| MDSCs | Myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| Tregs | Regulatory T cells |

| BBB | Blood-brain barrier |

| ICIs | Immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| PD-1 | Programmed Death-1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Death Ligand-1 |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen-4 |

| MHC | Major histocompatibility complex |

| NK | Natural killer |

| TCR | T cell receptor |

| NCRs | Natural cytotoxicity receptors |

| PAgs | Phosphoantigens |

| MEP | 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate |

| ADCC | Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| TAAs | Tumor-associated antigens |

| N-BPs | Nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates |

| ZOL | Zoledronic acid |

| CARs | Chimeric antigen receptors |

| MGMT | O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase |

| EGFR | Epidermal Growth Factor |

| N/A | Not Available |

| AE | Adverse Events |

| ROA | Administration Route |

| IC | Intracranial |

| ST-IC | Stereotactic Intracranial |

| IP | Intraperitoneal |

| IT | Intra-tumoral |

| ICV | Intraventricular |

References

- Di Carlo, D.T.; Cagnazzo, F.; Benedetto, N.; Morganti, R.; Perrini, P. Multiple High-Grade Gliomas: Epidemiology, Management, and Outcome. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurosurg Rev 2019, 42, 263–275. [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R.; Mason, W.P.; Van Den Bent, M.J.; Weller, M.; Fisher, B.; Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Belanger, K.; Brandes, A.A.; Marosi, C.; Bogdahn, U.; et al. Radiotherapy plus Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide for Glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2005, 352, 987–996. [CrossRef]

- Weller, M.; Van Den Bent, M.; Tonn, J.C.; Stupp, R.; Preusser, M.; Cohen-Jonathan-Moyal, E.; Henriksson, R.; Rhun, E.L.; Balana, C.; Chinot, O.; et al. European Association for Neuro-Oncology (EANO) Guideline on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Adult Astrocytic and Oligodendroglial Gliomas. The Lancet Oncology 2017, 18, e315–e329. [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Liu, C.; Hu, A.; Zhang, D.; Yang, H.; Mao, Y. Understanding the Immunosuppressive Microenvironment of Glioma: Mechanistic Insights and Clinical Perspectives. J Hematol Oncol 2024, 17, 31. [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Fan, W.; Lau, J.; Deng, L.; Shen, Z.; Chen, X. Emerging Blood–Brain-Barrier-Crossing Nanotechnology for Brain Cancer Theranostics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 2967–3014. [CrossRef]

- Naimi, A.; Mohammed, R.N.; Raji, A.; Chupradit, S.; Yumashev, A.V.; Suksatan, W.; Shalaby, M.N.; Thangavelu, L.; Kamrava, S.; Shomali, N.; et al. Tumor Immunotherapies by Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs); the Pros and Cons. Cell Commun Signal 2022, 20, 44. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Kong, Z.; Ma, W. PD-1/PD-L1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Glioblastoma: Clinical Studies, Challenges and Potential. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2021, 17, 546–553. [CrossRef]

- Lukas, R.V.; Rodon, J.; Becker, K.; Wong, E.T.; Shih, K.; Touat, M.; Fassò, M.; Osborne, S.; Molinero, L.; O’Hear, C.; et al. Clinical Activity and Safety of Atezolizumab in Patients with Recurrent Glioblastoma. J Neurooncol 2018, 140, 317–328. [CrossRef]

- Omuro, A.; Vlahovic, G.; Lim, M.; Sahebjam, S.; Baehring, J.; Cloughesy, T.; Voloschin, A.; Ramkissoon, S.H.; Ligon, K.L.; Latek, R.; et al. Nivolumab with or without Ipilimumab in Patients with Recurrent Glioblastoma: Results from Exploratory Phase I Cohorts of CheckMate 143. Neuro Oncol 2018, 20, 674–686. [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.W.; Quail, D.F. Immunotherapy for Glioblastoma: Current Progress and Challenges. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 676301. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guo, G.; Guan, H.; Yu, Y.; Lu, J.; Yu, J. Challenges and Potential of PD-1/PD-L1 Checkpoint Blockade Immunotherapy for Glioblastoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2019, 38, 87. [CrossRef]

- Ahmedna, T.; Khela, H.; Weber-Levine, C.; Azad, T.D.; Jackson, C.M.; Gabrielson, K.; Bettegowda, C.; Rincon-Torroella, J. The Role of Γδ T-Lymphocytes in Glioblastoma: Current Trends and Future Directions. Cancers 2023, 15, 5784. [CrossRef]

- Bryant, N.L.; Gillespie, G.Y.; Lopez, R.D.; Markert, J.M.; Cloud, G.A.; Langford, C.P.; Arnouk, H.; Su, Y.; Haines, H.L.; Suarez-Cuervo, C.; et al. Preclinical Evaluation of Ex Vivo Expanded/Activated Γδ T Cells for Immunotherapy of Glioblastoma Multiforme. J Neurooncol 2011, 101, 179–188. [CrossRef]

- Kang, I.; Kim, Y.; Lee, H.K. Γδ T Cells as a Potential Therapeutic Agent for Glioblastoma. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1273986. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, S.; Pereira, V.; Lau, C.; Teixeira, M.D.A.; Bini-Antunes, M.; Lima, M. Human Peripheral Blood Gamma Delta T Cells: Report on a Series of Healthy Caucasian Portuguese Adults and Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Cells 2020, 9, 729. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Lee, H.K. Function of Γδ T Cells in Tumor Immunology and Their Application to Cancer Therapy. Exp Mol Med 2021, 53, 318–327. [CrossRef]

- Hudspeth, K.; Silva-Santos, B.; Mavilio, D. Natural Cytotoxicity Receptors: Broader Expression Patterns and Functions in Innate and Adaptive Immune Cells. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4. [CrossRef]

- Göbel, A.; Rauner, M.; Hofbauer, L.C.; Rachner, T.D. Cholesterol and beyond - The Role of the Mevalonate Pathway in Cancer Biology. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 2020, 1873, 188351. [CrossRef]

- Sireci, G.; Espinosa, E.; Sano, C.D.; Dieli, F.; Fournié, J.-J.; Salerno, A. Differential Activation of Human γ δ Cells by Nonpeptide Phosphoantigens. Eur. J. Immunol. 2001, 31, 1628–1635. [CrossRef]

- Cieslak, S.G.; Shahbazi, R. Gamma Delta T Cells and Their Immunotherapeutic Potential in Cancer. Biomark Res 2025, 13, 51. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Ma, X.; Yang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, X.; Ma, W.; Duan, J.; Xue, J.; Yang, H.; et al. Phosphoantigens Glue Butyrophilin 3A1 and 2A1 to Activate Vγ9Vδ2 T Cells. Nature 2023, 621, 840–848. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Hu, Q.; Li, Y.; Lu, L.; Xiang, Z.; Yin, Z.; Kabelitz, D.; Wu, Y. Γδ T Cells: Origin and Fate, Subsets, Diseases and Immunotherapy. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 434. [CrossRef]

- Lo Presti, E.; Pizzolato, G.; Corsale, A.M.; Caccamo, N.; Sireci, G.; Dieli, F.; Meraviglia, S. Γδ T Cells and Tumor Microenvironment: From Immunosurveillance to Tumor Evasion. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 1395. [CrossRef]

- Dieli, F.; Poccia, F.; Lipp, M.; Sireci, G.; Caccamo, N.; Di Sano, C.; Salerno, A. Differentiation of Effector/Memory Vδ2 T Cells and Migratory Routes in Lymph Nodes or Inflammatory Sites. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 2003, 198, 391–397. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; He, W. γδT Cells: Alternative Treasure in Antitumor Immunity. Explor Immunol 2022, 32–47. [CrossRef]

- La Manna, M.P.; Di Liberto, D.; Lo Pizzo, M.; Mohammadnezhad, L.; Shekarkar Azgomi, M.; Salamone, V.; Cancila, V.; Vacca, D.; Dieli, C.; Maugeri, R.; et al. The Abundance of Tumor-Infiltrating CD8+ Tissue Resident Memory T Lymphocytes Correlates with Patient Survival in Glioblastoma. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2454. [CrossRef]

- Meraviglia, S.; Eberl, M.; Vermijlen, D.; Todaro, M.; Buccheri, S.; Cicero, G.; La Mendola, C.; Guggino, G.; D’Asaro, M.; Orlando, V.; et al. In Vivo Manipulation of Vgamma9Vdelta2 T Cells with Zoledronate and Low-Dose Interleukin-2 for Immunotherapy of Advanced Breast Cancer Patients. Clin Exp Immunol 2010, 161, 290–297. [CrossRef]

- Giannotta, C.; Autino, F.; Massaia, M. Vγ9Vδ2 T-Cell Immunotherapy in Blood Cancers: Ready for Prime Time? Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1167443. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, C. The Role of Human Γδ T Cells in Anti-Tumor Immunity and Their Potential for Cancer Immunotherapy. Cells 2020, 9, 1206. [CrossRef]

- Lafont, V.; Sanchez, F.; Laprevotte, E.; Michaud, H.-A.; Gros, L.; Eliaou, J.-F.; Bonnefoy, N. Plasticity of Î3δ T Cells: Impact on the Anti-Tumor Response. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Wang, W.; Hawes, I.; Han, J.; Yao, Z.; Bertaina, A. Advancements in γδT Cell Engineering: Paving the Way for Enhanced Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1360237. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Park, C.; Woo, J.; Kim, J.; Kho, I.; Nam, D.-H.; Park, W.-Y.; Kim, Y.-S.; Kong, D.-S.; Lee, H.W.; et al. Preferential Infiltration of Unique Vγ9Jγ2-Vδ2 T Cells Into Glioblastoma Multiforme. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 555. [CrossRef]

- Lamb, L.S.; Pereboeva, L.; Youngblood, S.; Gillespie, G.Y.; Nabors, L.B.; Markert, J.M.; Dasgupta, A.; Langford, C.; Spencer, H.T. A Combined Treatment Regimen of MGMT-Modified Γδ T Cells and Temozolomide Chemotherapy Is Effective against Primary High Grade Gliomas. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 21133. [CrossRef]

- Zagzag, D.; Salnikow, K.; Chiriboga, L.; Yee, H.; Lan, L.; Ali, M.A.; Garcia, R.; Demaria, S.; Newcomb, E.W. Downregulation of Major Histocompatibility Complex Antigens in Invading Glioma Cells: Stealth Invasion of the Brain. Lab Invest 2005, 85, 328–341. [CrossRef]

- Łaszczych, D.; Czernicka, A.; Gostomczyk, K.; Szylberg, Ł.; Borowczak, J. The Role of IL-17 in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Glioblastoma—an Update on the State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Med Oncol 2024, 41, 187. [CrossRef]

- Caccamo, N.; La Mendola, C.; Orlando, V.; Meraviglia, S.; Todaro, M.; Stassi, G.; Sireci, G.; Fournié, J.J.; Dieli, F. Differentiation, Phenotype, and Function of Interleukin-17-Producing Human Vγ9Vδ2 T Cells. Blood 2011, 118, 129–138. [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, T.N.; Schreiber, R.D. Neoantigens in Cancer Immunotherapy. Science 2015, 348, 69–74. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H.; Qiu, J.; O’Sullivan, D.; Buck, M.D.; Noguchi, T.; Curtis, J.D.; Chen, Q.; Gindin, M.; Gubin, M.M.; van der Windt, G.J.W.; et al. Metabolic Competition in the Tumor Microenvironment Is a Driver of Cancer Progression. Cell 2015, 162, 1229–1241. [CrossRef]

- Ribas, A.; Wolchok, J.D. Cancer Immunotherapy Using Checkpoint Blockade. Science 2018, 359, 1350–1355. [CrossRef]

- Hayday, A.C. Γδ T Cells and the Lymphoid Stress-Surveillance Response. Immunity 2009, 31, 184–196. [CrossRef]

- Rei, M.; Gonçalves-Sousa, N.; Lança, T.; Thompson, R.G.; Mensurado, S.; Balkwill, F.R.; Kulbe, H.; Pennington, D.J.; Silva-Santos, B. Murine CD27(-) Vγ6(+) Γδ T Cells Producing IL-17A Promote Ovarian Cancer Growth via Mobilization of Protumor Small Peritoneal Macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, E3562-3570. [CrossRef]

- Silva-Santos, B.; Serre, K.; Norell, H. Γδ T Cells in Cancer. Nat Rev Immunol 2015, 15, 683–691. [CrossRef]

- Kunzmann, V.; Bauer, E.; Feurle, J.; Tony, F.W., Hans-Peter; Wilhelm, M. Stimulation of Γδ T Cells by Aminobisphosphonates and Induction of Antiplasma Cell Activity in Multiple Myeloma. Blood 2000, 96, 384–392. [CrossRef]

- Roelofs, A.J.; Thompson, K.; Gordon, S.; Rogers, M.J. Molecular Mechanisms of Action of Bisphosphonates: Current Status. Clinical Cancer Research 2006, 12, 6222s–6230s. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, G.; Wan, X. Challenges and New Technologies in Adoptive Cell Therapy. J Hematol Oncol 2023, 16, 97. [CrossRef]

- Boucher, J.C.; Yu, B.; Li, G.; Shrestha, B.; Sallman, D.; Landin, A.M.; Cox, C.; Karyampudi, K.; Anasetti, C.; Davila, M.L.; et al. Large Scale Ex Vivo Expansion of Γδ T Cells Using Artificial Antigen-Presenting Cells. Journal of Immunotherapy 2023, 46, 5–13. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.P.; Heuijerjans, J.; Yan, M.; Gustafsson, K.; Anderson, J. Γδ T Cells for Cancer Immunotherapy: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials. OncoImmunology 2014, 3, e27572. [CrossRef]

- Capsomidis, A.; Benthall, G.; Van Acker, H.H.; Fisher, J.; Kramer, A.M.; Abeln, Z.; Majani, Y.; Gileadi, T.; Wallace, R.; Gustafsson, K.; et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Engineered Human Gamma Delta T Cells: Enhanced Cytotoxicity with Retention of Cross Presentation. Molecular Therapy 2018, 26, 354–365. [CrossRef]

- Siegers, G.M.; Lamb, L.S. Cytotoxic and Regulatory Properties of Circulating Vδ1+ Γδ T Cells: A New Player on the Cell Therapy Field? Molecular Therapy 2014, 22, 1416–1422. [CrossRef]

- Hayday, A.; Dechanet-Merville, J.; Rossjohn, J.; Silva-Santos, B. Cancer Immunotherapy by Γδ T Cells. Science 2024, 386, eabq7248. [CrossRef]

- Correia, D.V.; Lopes, A.C.; Silva-Santos, B. Tumor Cell Recognition by Γδ T Lymphocytes: T-Cell Receptor vs. NK-Cell Receptors. OncoImmunology 2013, 2, e22892. [CrossRef]

- Liguori, L.; Polcaro, G.; Nigro, A.; Conti, V.; Sellitto, C.; Perri, F.; Ottaiano, A.; Cascella, M.; Zeppa, P.; Caputo, A.; et al. Bispecific Antibodies: A Novel Approach for the Treatment of Solid Tumors. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2442. [CrossRef]

- Thommen, D.S.; Schumacher, T.N. T Cell Dysfunction in Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 547–562. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, J.; Wu, P.; Zhang, T.; Wei, Q.; Huang, J.; Wu, D. Γδ T Cell Exhaustion: Opportunities for Intervention. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 2022, 112, 1669–1676. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Katakura, R.; Ebina, T.; Yokoyama, J.; Fujimiya, Y. Interleukin-15 Effectively Potentiates the in Vitro Tumor-Specific Activity and Proliferation of Peripheral Blood gammadeltaT Cells Isolated from Glioblastoma Patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother 1998, 47, 97–103. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Fujimiya, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Katakura, R.; Ebina, T. A Simple Method for the Propagation and Purification of γδT Cells from the Peripheral Blood of Glioblastoma Patients Using Solid-Phase Anti-CD3 Antibody and Soluble IL-2. Journal of Immunological Methods 1997, 205, 19–28. [CrossRef]

- Fujimiya, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Katakura, R.; Miyagi, T.; Yamaguchi, T.; Yoshimoto, T.; Ebina, T. In Vitro Interleukin 12 Activation of Peripheral Blood CD3(+)CD56(+) and CD3(+)CD56(-) Gammadelta T Cells from Glioblastoma Patients. Clin Cancer Res 1997, 3, 633–643.

- Suzuki, Y.; Fujimiya, Y.; Ohno, T.; Katakura, R.; Yoshimoto, T. Enhancing Effect of Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-Alpha, but Not IFN-Gamma, on the Tumor-Specific Cytotoxicity of gammadeltaT Cells from Glioblastoma Patients. Cancer Lett 1999, 140, 161–167. [CrossRef]

- Cimini, E.; Piacentini, P.; Sacchi, A.; Gioia, C.; Leone, S.; Lauro, G.M.; Martini, F.; Agrati, C. Zoledronic Acid Enhances Vδ2 T-Lymphocyte Antitumor Response to Human Glioma Cell Lines. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2011, 24, 139–148. [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, T.; Nakamura, M.; Park, Y.S.; Motoyama, Y.; Hironaka, Y.; Nishimura, F.; Nakagawa, I.; Yamada, S.; Matsuda, R.; Tamura, K.; et al. Cytotoxic Human Peripheral Blood-Derived γδT Cells Kill Glioblastoma Cell Lines: Implications for Cell-Based Immunotherapy for Patients with Glioblastoma. J Neurooncol 2014, 116, 31–39. [CrossRef]

- Lamb, L.S.; Bowersock, J.; Dasgupta, A.; Gillespie, G.Y.; Su, Y.; Johnson, A.; Spencer, H.T. Engineered Drug Resistant Γδ T Cells Kill Glioblastoma Cell Lines during a Chemotherapy Challenge: A Strategy for Combining Chemo- and Immunotherapy. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e51805. [CrossRef]

- Nabors, L.B.; Lamb, L.S.; Goswami, T.; Rochlin, K.; Youngblood, S.L. Adoptive Cell Therapy for High Grade Gliomas Using Simultaneous Temozolomide and Intracranial Mgmt-Modified Γδ t Cells Following Standard Post-Resection Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy: Current Strategy and Future Directions. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1299044. [CrossRef]

- Joalland, N.; Chauvin, C.; Oliver, L.; Vallette, F.M.; Pecqueur, C.; Jarry, U.; Scotet, E. IL-21 Increases the Reactivity of Allogeneic Human Vγ9Vδ2 T Cells Against Primary Glioblastoma Tumors. J Immunother 2018, 41, 224–231. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Li, Y. Unraveling the Immunosuppressive Microenvironment of Glioblastoma and Advancements in Treatment. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1590781. [CrossRef]

- Chitadze, G.; Kabelitz, D. Immune Surveillance in Glioblastoma: Role of the NKG2D System and Novel Cell-based Therapeutic Approaches. Scand J Immunol 2022, 96, e13201. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ji, N.; Zhang, Y.; Chu, J.; Pan, C.; Zhang, P.; Ma, W.; Zhang, X.; Xi, J.J.; Chen, M.; et al. B7H3-Targeting Chimeric Antigen Receptor Modification Enhances Antitumor Effect of Vγ9Vδ2 T Cells in Glioblastoma. J Transl Med 2023, 21, 672. [CrossRef]

- Rosso, D.A.; Rosato, M.; Iturrizaga, J.; González, N.; Shiromizu, C.M.; Keitelman, I.A.; Coronel, J.V.; Gómez, F.D.; Amaral, M.M.; Rabadan, A.T.; et al. Glioblastoma Cells Potentiate the Induction of the Th1-like Profile in Phosphoantigen-Stimulated Γδ T Lymphocytes. J Neurooncol 2021, 153, 403–415. [CrossRef]

- Bryant, N.L.; Suarez-Cuervo, C.; Gillespie, G.Y.; Markert, J.M.; Nabors, L.B.; Meleth, S.; Lopez, R.D.; Lamb, L.S. Characterization and Immunotherapeutic Potential of Gammadelta T-Cells in Patients with Glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 2009, 11, 357–367. [CrossRef]

- Beck, B.H.; Kim, H.; O’Brien, R.; Jadus, M.R.; Gillespie, G.Y.; Cloud, G.A.; Hoa, N.T.; Langford, C.P.; Lopez, R.D.; Harkins, L.E.; et al. Dynamics of Circulating Γδ T Cell Activity in an Immunocompetent Mouse Model of High-Grade Glioma. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122387. [CrossRef]

- Chitadze, G.; Lettau, M.; Luecke, S.; Wang, T.; Janssen, O.; Fürst, D.; Mytilineos, J.; Wesch, D.; Oberg, H.-H.; Held-Feindt, J.; et al. NKG2D- and T-Cell Receptor-Dependent Lysis of Malignant Glioma Cell Lines by Human Γδ T Cells: Modulation by Temozolomide and A Disintegrin and Metalloproteases 10 and 17 Inhibitors. OncoImmunology 2016, 5, e1093276. [CrossRef]

- Jarry, U.; Chauvin, C.; Joalland, N.; Léger, A.; Minault, S.; Robard, M.; Bonneville, M.; Oliver, L.; Vallette, F.M.; Vié, H.; et al. Stereotaxic Administrations of Allogeneic Human Vγ9Vδ2 T Cells Efficiently Control the Development of Human Glioblastoma Brain Tumors. OncoImmunology 2016, 5, e1168554. [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, T.; Nakamura, M.; Matsuda, R.; Nishimura, F.; Park, Y.S.; Motoyama, Y.; Hironaka, Y.; Nakagawa, I.; Yokota, H.; Yamada, S.; et al. Antitumor Effects of Minodronate, a Third-Generation Nitrogen-Containing Bisphosphonate, in Synergy with γδT Cells in Human Glioblastoma in Vitro and in Vivo. J Neurooncol 2016, 129, 231–241. [CrossRef]

- Chauvin, C.; Joalland, N.; Perroteau, J.; Jarry, U.; Lafrance, L.; Willem, C.; Retière, C.; Oliver, L.; Gratas, C.; Gautreau-Rolland, L.; et al. NKG2D Controls Natural Reactivity of Vγ9Vδ2 T Lymphocytes against Mesenchymal Glioblastoma Cells. Clinical Cancer Research 2019, 25, 7218–7228. [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Kim, T.-G.; Jeun, S.-S.; Ahn, S. Human Gamma-Delta (Γδ) T Cell Therapy for Glioblastoma: A Novel Alternative to Overcome Challenges of Adoptive Immune Cell Therapy. Cancer Letters 2023, 571, 216335. [CrossRef]

- Lobbous, M.; Goswami, T.; Lamb, L.S.; Rochlin, K.; Pillay, T.; Ter Haak, M.; Nabors, L.B. INB-200: Fully Enrolled Phase 1 Study of Gene-Modified Autologous Gamma-Delta (Γδ) T Cells in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM) Receiving Maintenance Temozolomide (TMZ). JCO 2024, 42, 2042–2042. [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.D.; Gerstner, E.R.; Frigault, M.J.; Leick, M.B.; Mount, C.W.; Balaj, L.; Nikiforow, S.; Carter, B.S.; Curry, W.T.; Gallagher, K.; et al. Intraventricular CARv3-TEAM-E T Cells in Recurrent Glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2024, 390, 1290–1298. [CrossRef]

| Author, Year | Study Type | Aim of the Study | Technique | Findings | ROA (if therapy) |

Target | AE | Patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bryant et al., 2009 [68] | In vitro (preclinical) | Assess the innate immune function of T cells in GBM and their therapeutic potency | T cells from GBM patients and healthy controls were expanded and tested against U251MG, D54MG, U373MG, U87MG and primary GBM explants | GBM patients had fewer and weaker T cells. Activated T cells could kill GBM cells but spared normal astrocytes, indicating selective cytotoxicity. | N/A | GBM cell lines and primary cultures | N/A | GBM patients and healthy controls |

| Bryant et al., 2011 [13] | In vivo (mouse xenograft) | Evaluate T cell migration, infiltration, and antitumor efficacy in GBM | U251MG cells were implanted intracranially in immunodeficient mice, followed by stereotactic injection of expanded T cells | T cells significantly slowed tumor progression and extended survival. Demonstrated in vivo trafficking and tumor infiltration. | IC | U251MG xenografts | N/A | Immunodeficient mouse model |

| Cimini et al., 2011 [59] | In vitro | Investigate whether Zol enhances γδ T cell killing of GBM | Vδ2 T cells activated with phosphoantigens were co-cultured with T70, U251, and U373 GBM cells ± Zol | Zol enhanced perforin-mediated killing and induced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner, increasing γδ T cell efficacy. | N/A | GBM cell lines | N/A | Cell line model |

|

Lamb et al., 2013 [61] |

In vitro | Determine if MGMT-modified T cells resist TMZ and retain cytotoxicity | T cells were transduced with MGMT and tested on TMZ-resistant U87, U373, SNB-19 GBM lines | MGMT+ T cells resisted TMZ and remained effective against GBM. TMZ increased NKG2D ligands, enhancing T cell sensitivity. | N/A | TMZ-resistant GBM cells | N/A | GBM cell lines |

| Nakazawa et al., 2014[60] | In vitro | Examine the role of Zol in boosting γδ T cell cytotoxicity | U87MG, U138MG, A172 GBM lines were treated with Zol before γδ T cell exposure | Zol sensitized GBM cells, killing from <32% to over 80% in some lines. Blocked by anti-TCR antibody. | N/A | GBM cell lines pretreated with Zol | N/A | GBM cell lines |

| Beck et al., 2015 [69] | In vivo (immunocompetent mouse) | Characterize γδ T cell kinetics and immune suppression in glioma | GL261 murine glioma model used to monitor T cell cytokines and tumor progression | T cells expanded early, then collapsed. Tumors secreted TGF-β, promoting immune evasion. No survival difference in γδ T cell KO mice. | N/A | GL261 gliomas | N/A | Immunocompetent mice |

| Chitadze et al., 2016 [70] | In vitro | Assess impact of TMZ and metalloprotease inhibitors on NKG2DL expression | U87MG, A172, T98G, U251MG treated with TMZ and ADAM10/17 inhibitors; tested with BrHPP-activated γδ T cells | TMZ upregulated ULBP2 on GBM surface. ADAM inhibition prevented shedding, enhancing T cell-mediated lysis. | N/A | NKG2DLs (MICA, MICB, ULBPs) | N/A | Human GBM cell lines |

| Jarry et al., 2016 [71] | In vivo (xenograft) | Test if stereotactic injection of γδ T cells with Zol improves survival | Vγ9Vδ2 T cells were injected into brains of mice bearing U87MG or GBM-10 xenografts ± Zol | Stereotactic delivery led to tumor clearance and improved survival, especially with Zol sensitization. | ST-IC | U87MG, GBM-10 | N/A | Mice with human GBM xenografts |

| Nakazawa et al., 2016 [72] | In vitro & in vivo | Evaluate synergy between minodronate and γδ T cells | Co-culture of GBM cells with γδ T cells ± minodronate; IP injection in immunocompromised mice | Combination induced higher granzyme B, TNF-α release, stronger apoptosis, and tumor inhibition in vivo. | IP (mice) | U87MG, U138MG | N/A | Immunodeficient mouse model |

| Joalland et al., 2018 [63] | In vivo | Investigate effect of IL-21 on γδ T cell cytotoxicity in GBM | Vγ9Vδ2 T cells were pretreated with IL-21 and injected into GBM-bearing mice | IL-21 enhanced cytotoxicity against GBM-1 and U87MG. Survival extended from 41 to 66 days. | ST-IC | GBM-1 (primary), U87MG | N/A | Orthotopic GBM mouse model |

| Chauvin et al., 2019 [73] | In vitro & in vivo | Evaluate immunoreactivity of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells against molecular subtypes of patient-derived GBM cells | Co-culture of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells with mesenchymal (GBM-1) and classical/proneural (GBM-10) cells; tested with/without nitrogen bisphosphonate | Vγ9Vδ2 T cells naturally lysed mesenchymal GBM-1 but not GBM-10. NBPs were required to sensitize GBM-10. Killing depended on TCR and NKG2D pathways. | N/A | Mesenchymal vs classical GBM subtypes | N/A | Patient-derived GBM primary cultures |

| Lee et al., 2019 [32] | In vitro | Characterize tumor-infiltrating γδ T cells in GBM patients | TCR sequencing of tumor and blood-derived γδ T cells from patients | Tumor-infiltrating Vγ9Vδ2 T cells had non-canonical TCR sequences and cytotoxic gene profiles similar to Th1 and M1 macrophages. | N/A | Tumor-infiltrating Vγ9Vδ2 T cells | N/A | GBM patients |

| Choi et al., 2023 [74] | Review | Summarize γδ T cells as a non-MHC-based GBM therapy | Review of existing in vitro/in vivo and early clinical data | Vγ9Vδ2 T cells use NKG2D/DNAM-1 to recognize stress ligands; CAR or checkpoint-enhanced platforms proposed. | IT, ICV (proposed) |

NKG2D, DNAM-1 ligands | N/A | Preclinical evidence |

| Nabors et al., 2024 [62] | Phase 1 clinical trial (ongoing) | Test safety/feasibility of MGMT-modified γδ T cells with TMZ | Drug-resistant immunotherapy: MGMT+ γδ T cells injected during concurrent TMZ | MGMT expression allows T cells to persist during TMZ. Trial ongoing; preliminary data shows feasibility. | IC | NKG2D ligands (e.g., MICA, ULBP2) | Not fully disclosed | Newly diagnosed GBM patients |

| Lobbous et al., 2024 [75] | Phase 1 trial | Determine safety of intracranial MGMT+ γδ T cells during SOC | MGMT+ γδ T cells injected into surgical resection cavity during standard Stupp regimen | No dose-limiting toxicities. Some patients had PFS benefit. Mild hematological AEs only. | IC (resection cavity) |

NKG2D ligands | Mild hematologic; no CRS | Newly diagnosed GBM patients |

| Choi et al., 2024 [76] | Phase 1 trial (dose escalation) | Assess safety of CARv3-TEAM-E T cells targeting EGFR/EGFRvIII | Autologous CAR-T cells delivered intraventricularly; dual-targeting with enhanced cytotoxic modules | Partial tumor regressions observed. No dose-limiting toxicities. Reversible neurotoxicity (grade 3) and fatigue reported. | ICV | EGFRvIII and wild-type EGFR | Grade 3 encephalopathy, fatigue | Recurrent EGFRvIII+ GBM patients |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).