1. Introduction

In the Neolithic and Bronze Ages, in a number of regions around the world, local inhabitants created a rock-cut culture. In its older layer, it was expressed in the generation of specific natural rock forms, and later it turned to the creation of processed monuments. First, they carved them into the rocks with the help of harder stone or bronze tools - these are the so-called rock-cut monuments. Subsequently, in many places, independent structures of huge and roughly split (hewn) rock blocks appeared in the form of pillars, slabs, vertical, horizontal, linear or circular combinations of them - these are the so-called megalithic sites [

1,

2].

On the ground, there are both pure megaliths (menhirs, dolmens and their derivatives), and mixed or quasi-megalithic sites. The mixing can go in two directions:

-along with the typical rock-cut and megalithic elements, the site may contain sections executed in classical dry masonry of relatively small stone pieces;

-along with the typical megalithic elements, the site may contain sections formed by rock-cutting, incising and splitting.

Some of the most impressive rock-cut cult complexes have been preserved on the territory of Bulgaria [

3]. These are the places in whose sacred territory all possible elements are usually found – rock-cut altars, altars, purification pools, o-relief discs, caves (natural or rock-cut), stairs and platforms cut into the rock foundations of rooms, pole beds of wooden structures and buildings. Often, but not necessarily, the entire space or its central part is protected by a wall [

4]. The most striking examples are the rock complexes: “Harman Kaya”, “Tatul”, “Shterna” - Momchilgrad region, “Tangardak Kaya”, “Perperek” - Kardzhali region, “Gluhite kamani”, the rock sanctuary near the village of Svirachi, - Ivaylovgrad region, “Paleokastro” - Topolovgrad region, “Belintash” - Asenovgrad region [

5,

6,

7,

8].

Rock-cut monuments and megaliths have been preserved with amazing constancy in the principles of construction. In this sense, it could be argued that the spread of the idea of them is the oldest globalization carried out in the world. The first constructive principle used is: megaliths are not created through classical masonry, but by grouping and assembling two main types of building elements - pillars and slabs. The second generally valid principle is: the building elements are so large that they often have the size of the building itself, i.e., their number is minimal [

9,

10].

From a physical point of view, rock-cut and megalithic sites are interesting in at least three aspects.

1. The first physical aspect is related to the stability of the structure from the point of view of statics - cuttings and tools, stability of the construction, joints between the few but very large building elements, the strengthening role of mounds and rock clusters around, etc. [

11].

2. The second physical aspect is related to archaeoastronomy - orientation of the sites in some specific directions that are astronomically significant and directed towards: stars, constellations, Sun, Moon, sunrises, sunsets, culminations, etc. The orientation is probably related to early mythology or to attempts to create stable calendars [

12].

2. The third physical aspect is related to the possibility of their direct dating. Conventional dating in archaeology is related to the found artifacts. However, it is indirect – it dates the last use of the object, but not the time of its creation. In the 1970s, dating by thermoluminescence (TL) was proposed, and later by photoluminescence (PL) or optically stimulated luminescence (OSL). This is a direct method that shows the very moment of the creation of the object [

13]. Its typical error is 5-10%.

The research, cultural-historical and religious interest of wide public circles in rock-cut and megalithic monuments all over the world constantly gives rise to research, educational, restoration-conservation and exhibition-tourist projects for individual objects or groups of them [

14]. The mystery of the millennial belief in sacred rocks, caves and large stones, which challenges the knowledge and imagination of generations of scientists and lovers of antiquity, is so fascinating that its answers continue to be incomplete or inaccurate.

The beginning of these rock topoi of faith dates back to the end of the Chalcolithic era (5 thousand BC), and their formation as sanctuaries with religious, administrative and economic functions, belonging to the population of entire regions, marks the ethnogenesis processes of the Thracian and other paleo peoples. Some of these sanctuaries became royal cities (Kabile, Yambol region; the archaeological reserve near the village of Sveshtari, Razgrad region; the rock complex between the villages of Perperek and Gorna Krepost, Kardzhali region) or into sacred territories with temples and necropolises (the village of Starosel, Hissar region). Such processes are observed in antiquity in other regions of Southeast Europe and Asia Minor.

Ancient Thrace is the contact zone, opened to the south to the Aegean world, to the southeast to Anatolia, to the northeast to the Black Sea steppes and the Caucasus, and to the northwest/west to Central Europe and Italy, due to the Thracian belief in immortality and their role as a “plaque tournante” (rotating disk) between East and West. One of the mysteries of the Thracian rock-cut and megalithic complexes, to which no answer has been given, is why such sanctuaries, described in ancient Greek and Latin sources and philosophical-Neoplatonic treatises and traditionally considered philosophical-religious speculative constructions, are found precisely on the territory of ancient Thrace. The rock sanctuaries and megalithic complexes on the territory of present-day Bulgaria are located mainly in the mountains (Rhodopi, Strandzha, Sakar, Stara Planina). They show similarities with the rock sanctuaries in the ancient Anatolian cultures (Phrygian, Hittite, Urartian, Lycian), as well as with the Hellenic, Paleo Balkan and Italian. The specific thing is that in the Thracian rock complexes all possible elements are found, which are present individually or in combination in the other cultures mentioned above – rock-cut rooms, stairs, sacrificial platforms and sacrificial pits, altars, sacred caves, suns, votive niches, chutes for draining sacrificial liquids, etc. [

15]. At the same time, the knowledge of rock cutting was used very rationally to drain the rocky terrains and form stone, wooden and adobe rooms. It is traditionally assumed that the ancient Phrygians, who, according to Herodotus, migrated from Thrace to Asia Minor and established their kingdom there, brought their veneration of the Mountain Great Mother Goddess, glorified in rock-cut sanctuaries and megalithic complexes, precisely from the Thracian European southeast (the most famous rock-cut complex of the Phrygians is the “City of Midas”). On the territory of Southeast Europe and Asia Minor, rock-cut sacred sites can generally be typified as sanctuaries for the confession of mass mystery rites, for individual initiation rites, sanctuaries for the confession of doctrinal rites of closed societies, sanctuaries with necropolises, sacred caves for initiation rites through katabasis (“descent into the Underworld”) [

2]. Many of the rock-cut sacred sites of the Thracians and other paleo peoples are become hereditary topoi of faith and have been assimilated over the centuries by folk Christianity, and some have been transformed into Aliyan (Shiite) sanctuaries. Many of these topoi of faith are still revered by people of different ethnic consciousness and religious affiliation as holy places [

16,

17,

18].

Condition of the sites: for the most part, the rock-cut and megalithic monuments are registered, but have not been documented with modern methods [

15]. The difficult accessibility and their remoteness from populated areas further increase the cost of the activities of discovering, documenting, preserving and socializing the individual monuments. For this reason, the rock-cut and megalithic monuments are not known to the general public, but only to a very narrow circle of specialists. The lack of professional documentation for the sites makes it difficult to preserve them, introduce them into a scientific approach and interpret them in the Eurasian cultural and historical context. This context concerns the overall problem of the Southeast European–Asia Minor–Black Sea–Aegean rock topographies of faith and the formation of the oral “faith-ritualism”, which developed in parallel with the classical literary Olympian religion. Progress in the study of oral faith-ritualism as a basic element of the most ancient European and Anatolian culture requires the urgent preparation of several types of modern documentation of rock-cut and megalithic monuments, before proceeding to archaeological excavations and their comprehensive study. It should be emphasized that the exposure of rocks in these places leads to irreversible erosion processes and the loss of the monument to modern human civilization.

2. Materials and Methods

Two Bulgarian rock-cut monuments have been studied using several methods of investigation: the Belintash rock sanctuary near the Municipality of Asenovgrad and the cromlech near the village of Dolni Glavanak, Municipality of Madzharovo.

- A.

Use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV)

In this sense, the filming, documentation and visualization of objects of the cultural and historical rock-cut heritage in Bulgaria has an expanding field of application. Modern unmanned aerial systems (UAS) offer a technology for obtaining geometric and semantic information about archaeological sites, rock-cut monuments and megaliths from images using various types of sensors. The use of digital cameras built into mid-range UAS, together with appropriate software and methodology, allows obtaining accurate digital spatial products for rock-cut monuments.

The objects selected by us by type and current condition do not imply the possibility of reconstructing their geometric structure only from metric data (geodetic measurements or data from map sources). For this reason, it is better to apply a technology for three-dimensional reconstruction based on data from remote sensing – photogrammetric shooting with an unmanned aerial system (UAS) or the so-called aerial photogrammetry.

Remote data collection methods of this type allow the creation of detailed three-dimensional models of historical monuments or archaeological sites, showing their condition over time. This allows not only to record each stage of their study, but also to analyze changes over time [

19]. Remote sensing methods and three-dimensional modeling of objects using this data can be called three-dimensional precise digitization of the relevant monuments, which constitutes an important digital archive. This archive serves to preserve historical data about the object, but can also be the basis for its restoration in the event of events leading to damage, destruction or subsequent socialization.

- B.

Photogrammetric methods for mapping rock-cut and megalithic monuments

Automated aerial and close-range digital photogrammetry have become a powerful and widely used tool for three-dimensional topographic modeling. The development of algorithms for modeling the surface of the monument and its adjacent terrain, through digital image processing, radically improves the quality of data about the monument and the terrain [

20]. Also, the decline in the price and improvement in the quality of compact cameras (SLR - Single-Lens Reflex camera), as well as the methods for calibrating such non-metric cameras, lead to a wider use of photogrammetric modeling and the development of a wide range of software applications used to process the data.

- C.

Image Processing Method – SfM

The Structure from Motion (SfM) method is based on matching features (points) in multiple overlapping images to simultaneously and automatically solve for the three-dimensional camera position and image geometry [

21]. The SfM method is based on the principles of photogrammetry, in which a significant number of photographs taken from different overlapping viewpoints are combined to recreate the studied rock object - i.e., a 3D structure is obtained from a series of overlapping images.

However, the SfM method differs significantly from traditional photogrammetry. While classical photogrammetry relies on overlapping image strips obtained from parallel flight lines, SfM reconstructs the three-dimensional geometry of rock features from random (unordered) images. An important condition is that a physical point of a rock feature is present in multiple images. The principle of using randomly positioned images is possible thanks to advances in automatic image matching. For example, the scale-invariant feature transform SIFT [

22], where the key approach is the ability to recognize a specific physical feature present in multiple images regardless of the scale (i.e., resolution) of the images and the viewpoint of the image. Classical photogrammetry relies on images with the same resolution due to the image correlation-based processing approach. These approaches rely on cross-correlation, calculated with a simple image convolution operator, between pixel samples from two images. As a result, these cross-correlation methods are very sensitive to changes in image resolution. Furthermore, the use of image brightness and color gradients in algorithms such as SIFT, rather than absolute pixel values, means that an object can be identified by being registered from many viewpoints [

21].

Another fundamental difference between classical digital photogrammetry and SfM methods is the need for ground control points with known coordinates. In classical photogrammetry, the coordinates of the control points are needed to solve the collinearity equations that define the relationship between the camera, the image, and the ground surface. The external orientation elements determine the spatial position and angular orientation of the camera at the time of creation of a given image.

In the SfM method, camera positions and orientations are automatically solved without the need to first have a grid of control points with known 3D coordinates [

23]. Instead, they are solved simultaneously using many repeated iterative batch alignment procedures that are based on a database automatically extracted from the overlapping images [

24].

- D.

Workflow for applying the SfM method

The ease of use of the SfM method, its accessibility, and the automated algorithm it provides make it possible for a large group of users. With a simple digital camera and processing software, clouds with 3D points and orthophoto mosaics of a rock object. There are several photogrammetric programs using the SfM method. The most popular commercial solutions include Agisoft Photo Scan and Pix4D, which have become popular due to their user-friendly interface and support. There are also open source SfM solutions, which include Visual SfM, OSM-Bundler (software for reconstruction a 3D geometry from a set of photos, OpenStreetMap for example), Photosynth Toolkit, OpenDroneMap, etc. While SfM programs differ from each other, they all follow a common workflow. The following workflow was developed by Rossi et al. [

25]. Open source products vary depending on the program. Some allow several steps to be performed, while others have only one step and must be combined with additional modules and software products.

The activities carried out to obtain 3D models of the rock-cut monument “Belintash” near the village of Mostovo and the cromlech near the village of Dolni Glavanak, Madzharovo Municipality [

26,

27,

28] include the following steps in the workflow for three-dimensional modeling:

a) Preliminary preparation:

-Localization of the study areas, selection of specific rock-cut and megalithic sites, stabilization and measurement of ground control points (GCP).

b) Photogrammetric shooting:

-Selection of UAV;

-Preparation of a flight plan with UAV;

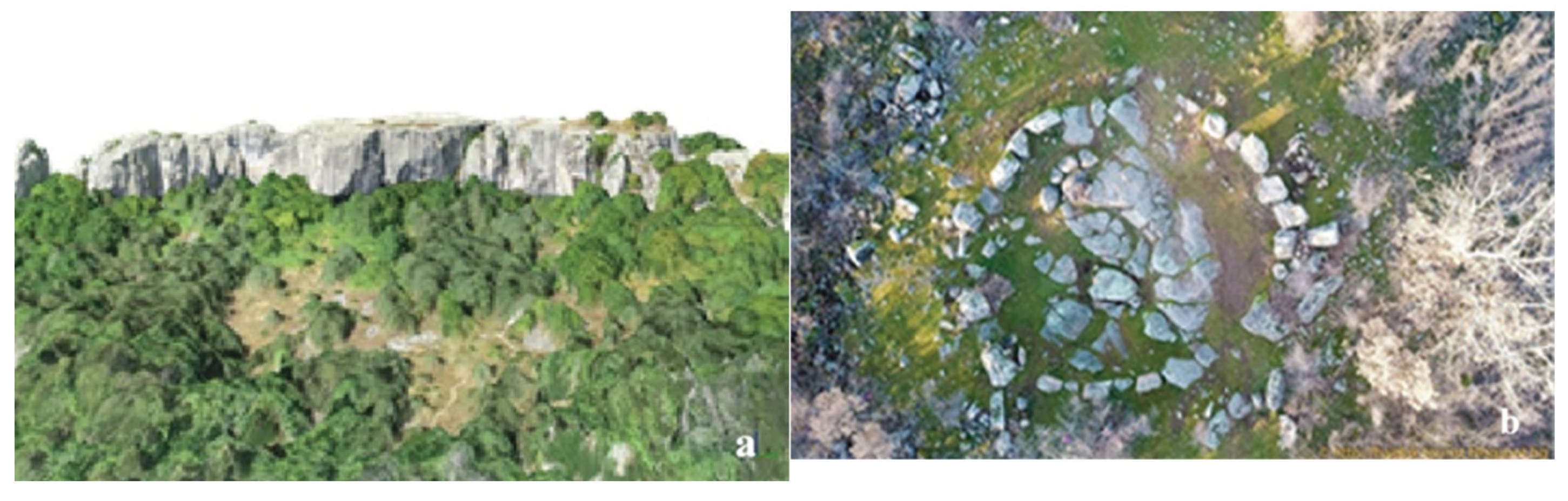

-Performance of flights and shooting of the rock-cut site and cromlech (

Figure 1a,b).

c) Data processing:

-Generation of digital products from the processed data;

-Creation of vector metric data for the sites;

-Three-dimensional modeling and visualization of the sites;

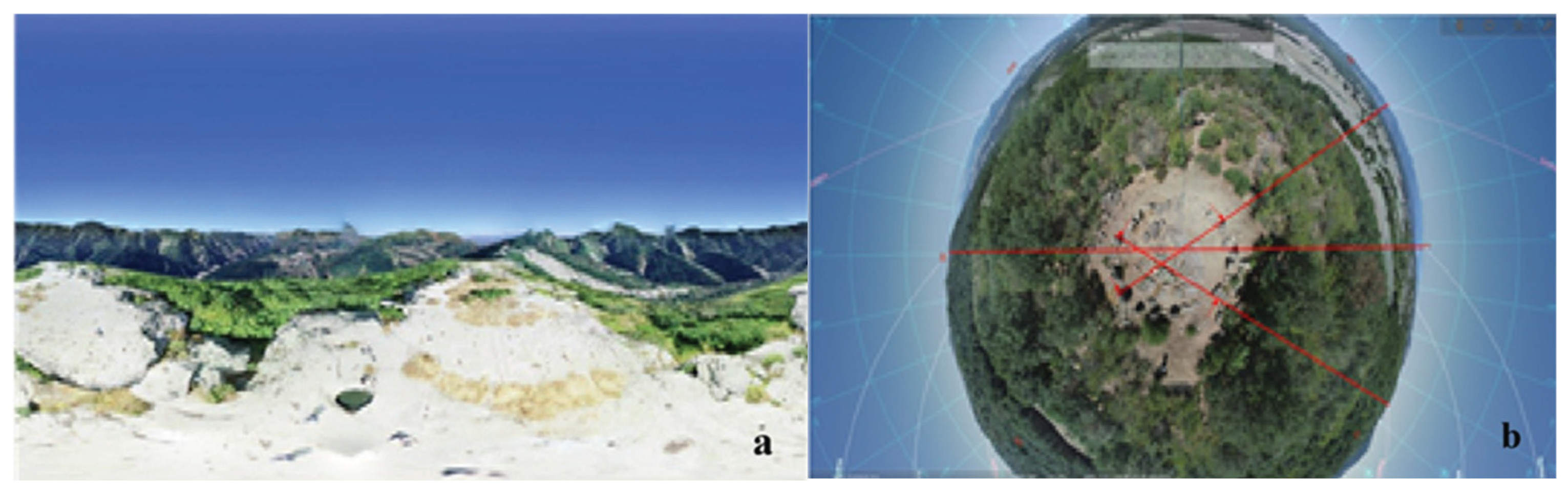

-Development of a simplified three-dimensional model of the rock-cut monument “Belintash” near the village of Mostovo and cromlech near the village of Dolni Glavanak (

Figure 2a,b);

-Integration of the three-dimensional models into the specialized astronomical software Stelarium, obtaining the possibility of virtual astronomical observations in the supposed era of creation and functioning of the monument, as well as during various prehistoric periods of interest to the archaeoastronomer-researcher.

Image sources - the first step in the workflow is the selection of the desired images to be processed. We must have consecutive images that cover the rock-cut object. When using images captured with a UAV, an important condition is that there is such an overlap of the images that the selected object is present in multiple images. Algorithms for matching characteristic points rely on this principle, and therefore the greater the overlap of the images, the more matches will be obtained during processing.

Feature extraction procedure - after the images are imported into the processing system, an algorithm for extracting basic features must be executed for each image. This step generates a set of descriptors (control blocks) for each image. A descriptor is an identifier of a key point that distinguishes it from the rest of the mass of single points. In turn, descriptors must provide the invariance to find a correspondence between single points with respect to image transformations. There are numerous feature extraction algorithms, the most common of which is SIFT (Scale Invariant Feature Transform), developed by Lowe [

22]. SIFT provides robust descriptors under various image conditions and is an algorithm that transforms an image into a large collection of local fundamental vectors, through which invariance (an unchanging feature of a single unit that unifies its variants) is obtained. Invariance is with respect to translation, rotation, scale and partly for the illumination of the objects [

29].

Feature matching procedure - the next step in the SfM workflow is to create a feature matching table that connects all combinations of descriptors between the images. The goal is to calculate the connection points or correspondence between the images. The process of comparing two images can be described by the following sequence:

-the main points and their descriptors are selected from the images;

-by matching the descriptors, the corresponding key points are allocated;

-based on the set of matching key points, an image transformation model is built, through which one image can be obtained from the other.

This step can be computationally heavy due to the number of required comparisons of a large number of data. The process can be run in parallel and divided into separate tasks. Multi-core or clustered computing environments can be used to reduce the required computation time [

25].

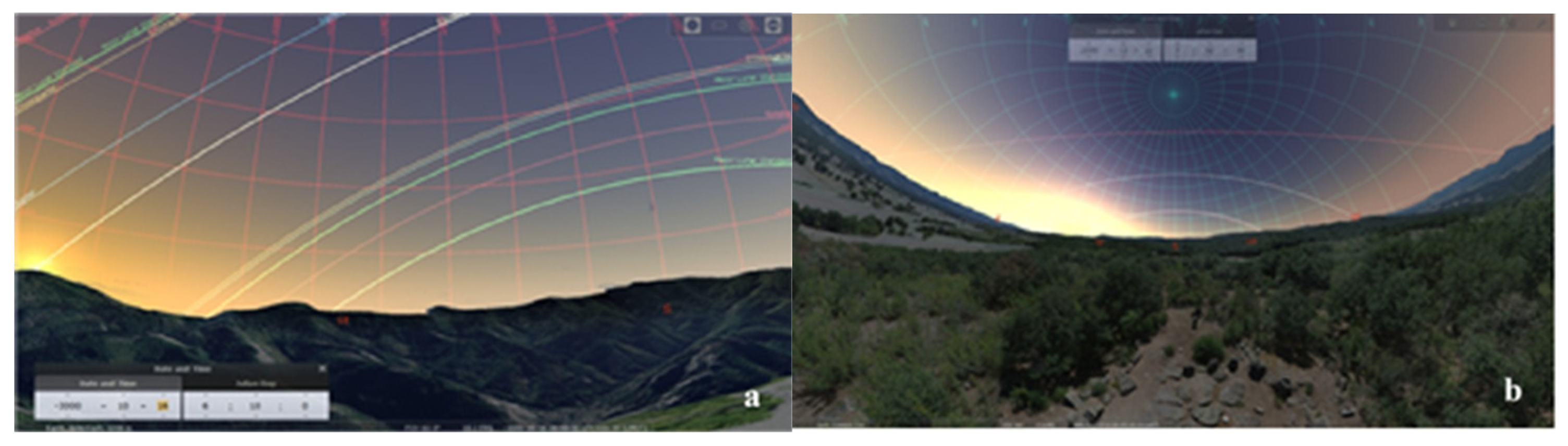

Group alignment procedure - Group alignment is a solution for refining the visual reconstruction to create a mutually optimal 3D structure and camera parameters (

http://www.theia-sfm.org/sfm.html, modified procedure). As a result of the large number of identical points identified during the automated image matching phase, SfM can solve the collinearity equations in an arbitrarily scaled coordinate system. In addition, the processing process also calculates the elements of the camera’s internal orientation (focal length, principal point coordinates, radial and tangential lens distortion, other characteristics) (

Figure 3a,b).

The intermediate stage in the SfM workflow is to obtain a point cloud (initial sparse cloud) with local X, Y and Z coordinates that are not in the real coordinate system. At this point, GCP coordinates (ground control points) and/or camera position coordinates are entered to transform and register this SfM point cloud to an established coordinate system. This transformation is linear and rigid and produces a point cloud suitable for mapping applications.

Procedure for generating a dense 3D point cloud - as a result of the batch alignment, the camera parameters for each image are obtained and a sparse three-dimensional point cloud is generated for the studied rock object. With these parameters, the 3D cloud is densified. The cloud compaction process uses the parameters (elements of internal and external orientation) of the camera, the correspondence between the 2D images, the features around the 2D correspondences and the triangulation algorithm to extract 3D points for the rock object [

25]. Such a frequently used system is PMVS (Patch-based Multi-view Stereo Software patch) [

29].

Surface reconstruction procedure - for the reconstruction of the object surface of the rock monument, the “Poisson Surface Reconstruction” algorithm can be used, through which we obtain a textured surface from the generated 3D point cloud (with oriented normals). This is an approach that expresses the surface reconstruction as a solution to the spatial Poisson problem [

30]. This step results in products such as orthorectified images (orthophoto mosaics) and three-dimensional textured surfaces [

31].

Visualization procedure - after obtaining the digital products in the previous stages of the SfM workflow, the last step is their visualization. Commercial software packages, such as Agisoft PhotoScan and Pix4D, have built-in visualizers of 3D clouds and textured surfaces. Open source programs such as Meshlab and Blender can be used for additional processing of 3D point clouds and surfaces, as well as for their visualization. In our case, the SfM image processing method was applied to model the structure of the terrain surface of the rock-cut monument “Belintash” near the village of Mostovo and the cromlech near the village of Dolni Glavanak, Madzharovo Municipality [

32,

33].