Submitted:

26 June 2025

Posted:

27 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Functional Hypogonadism

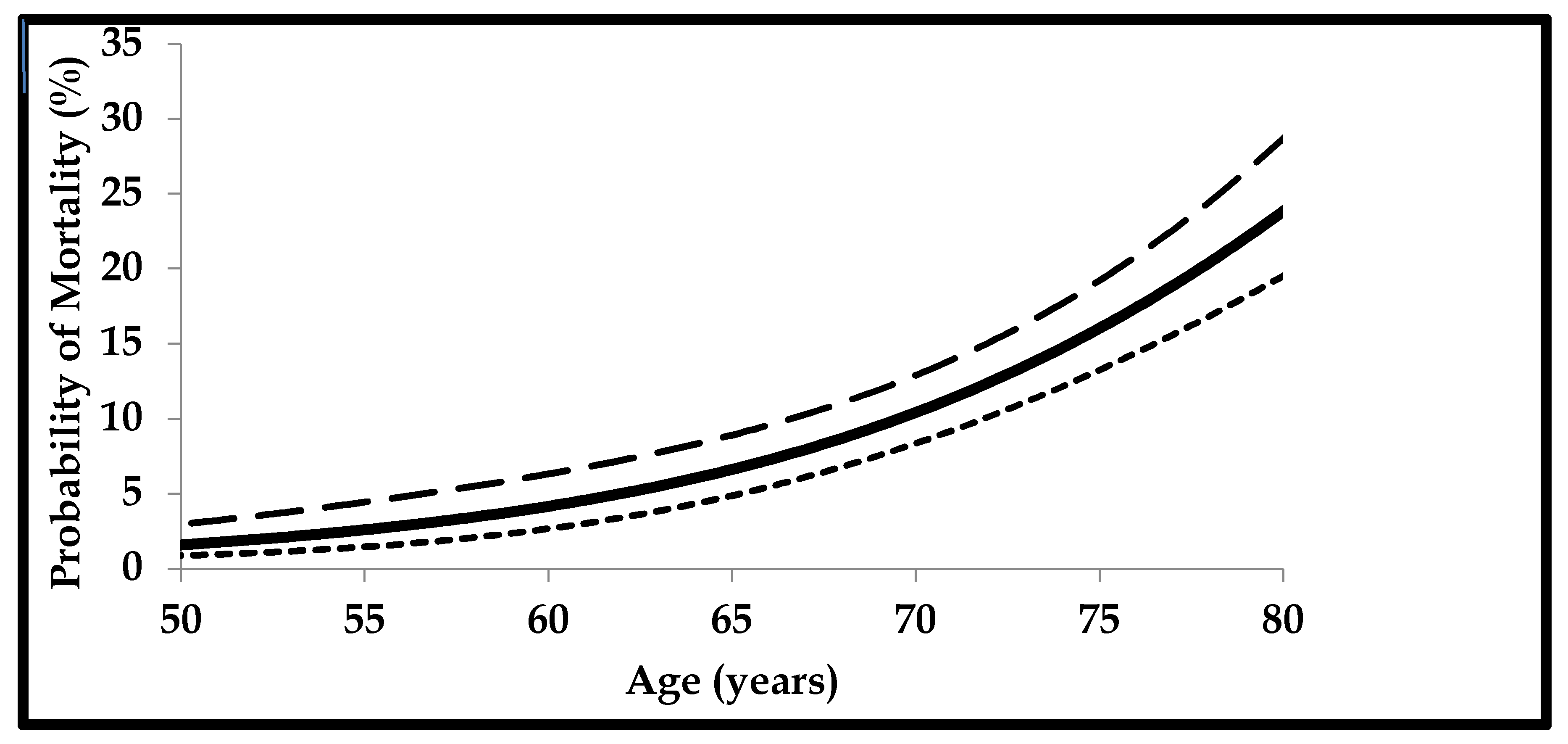

μ(x) = mortality rate

age = x

α and β = constants representing the ageing rate

3. Cardiovascular Disease Prevention

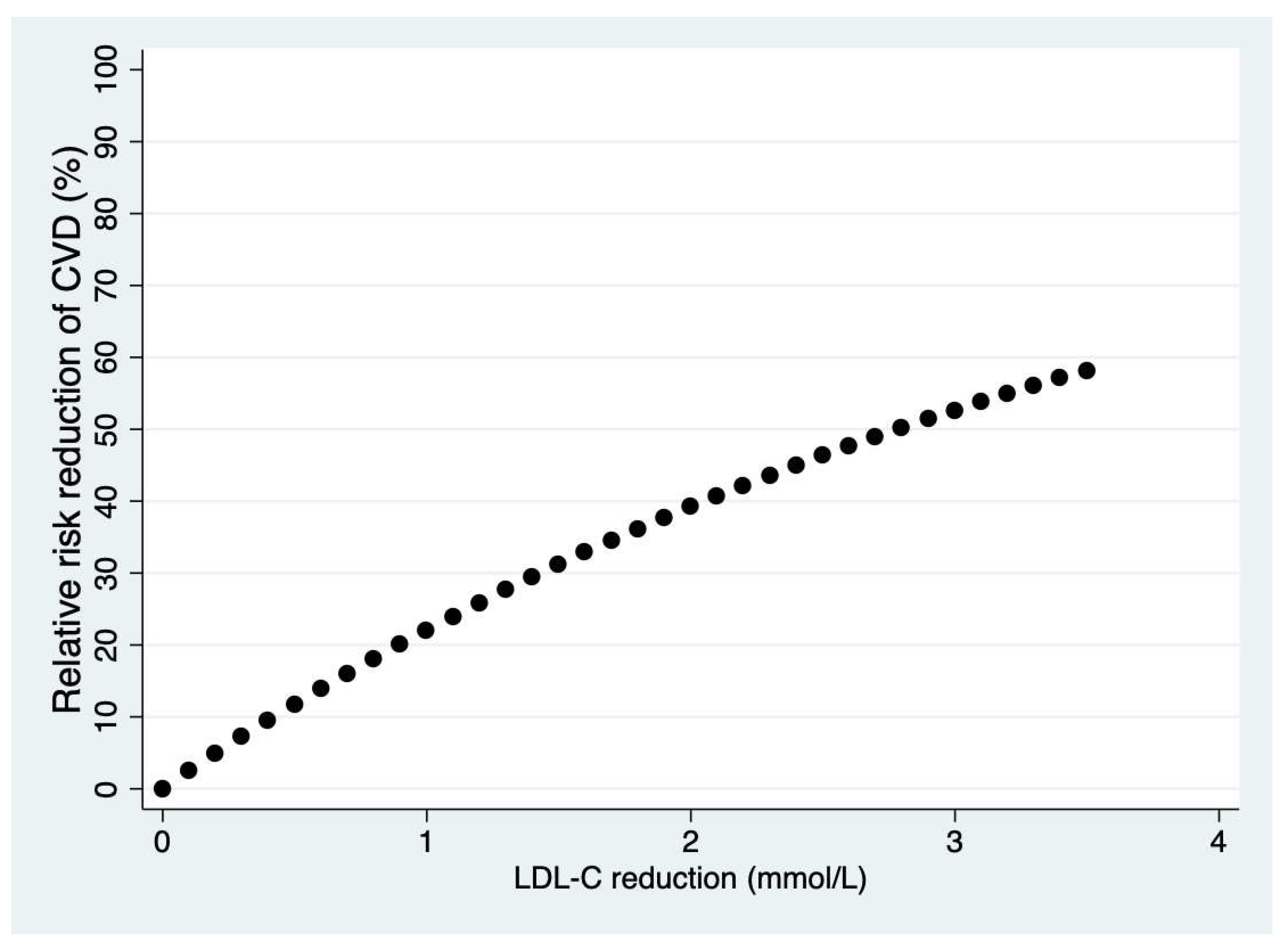

α = LDL-C decrease

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- Mir TH. Adherence Versus Compliance. HCA Healthc J Med. 2023;4(2):219-220. [CrossRef]

- Aremu TO, Oluwole OE, Adeyinka KO, Schommer JC. Medication Adherence and Compliance: Recipe for Improving Patient Outcomes. Pharmacy (Basel). 2022;10(5):106. [CrossRef]

- Driever EM, Brand PLP. Education makes people take their medication: myth or maxim? Breathe (Sheff). 2020;16(1):190338. [CrossRef]

- Cheen MHH, Tan YZ, Oh LF, Wee HL, Thumboo J. Prevalence of and factors associated with primary medication non-adherence in chronic disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pract. 2019;73(6):e13350. [CrossRef]

- Foley L, Larkin J, Lombard-Vance R, Murphy AW, Hynes L, Galvin E, Molloy GJ. Prevalence and predictors of medication non-adherence among people living with multimorbidity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021 Sep 2;11(9):e044987. Erratum in: BMJ Open. 2022;12(7):e044987corr1. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044987corr1. PMID: 34475141; PMCID: PMC8413882. [CrossRef]

- Kvarnström K, Westerholm A, Airaksinen M, Liira H. Factors Contributing to Medication Adherence in Patients with a Chronic Condition: A Scoping Review of Qualitative Research. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(7):1100. [CrossRef]

- Tenny S, Varacallo MA. Evidence-Based Medicine. [Updated 2024 Sep 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470182/.

- O’Connor AM, Wennberg JE, Legare F, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Moulton BW, Sepucha KR, Sodano AG, King JS. Toward the ‘tipping point’: decision aids and informed patient choice. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(3):716-25. [CrossRef]

- O’Connor AM, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Flood AB. Modifying unwarranted variations in health care: shared decision making using patient decision aids. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;Suppl Variation:VAR63-72. [CrossRef]

- Kumah EA, McSherry R, Bettany-Saltikov J, van Schaik P. Evidence-informed practice: simplifying and applying the concept for nursing students and academics. Br J Nurs. 2022;31(6):322-330. [CrossRef]

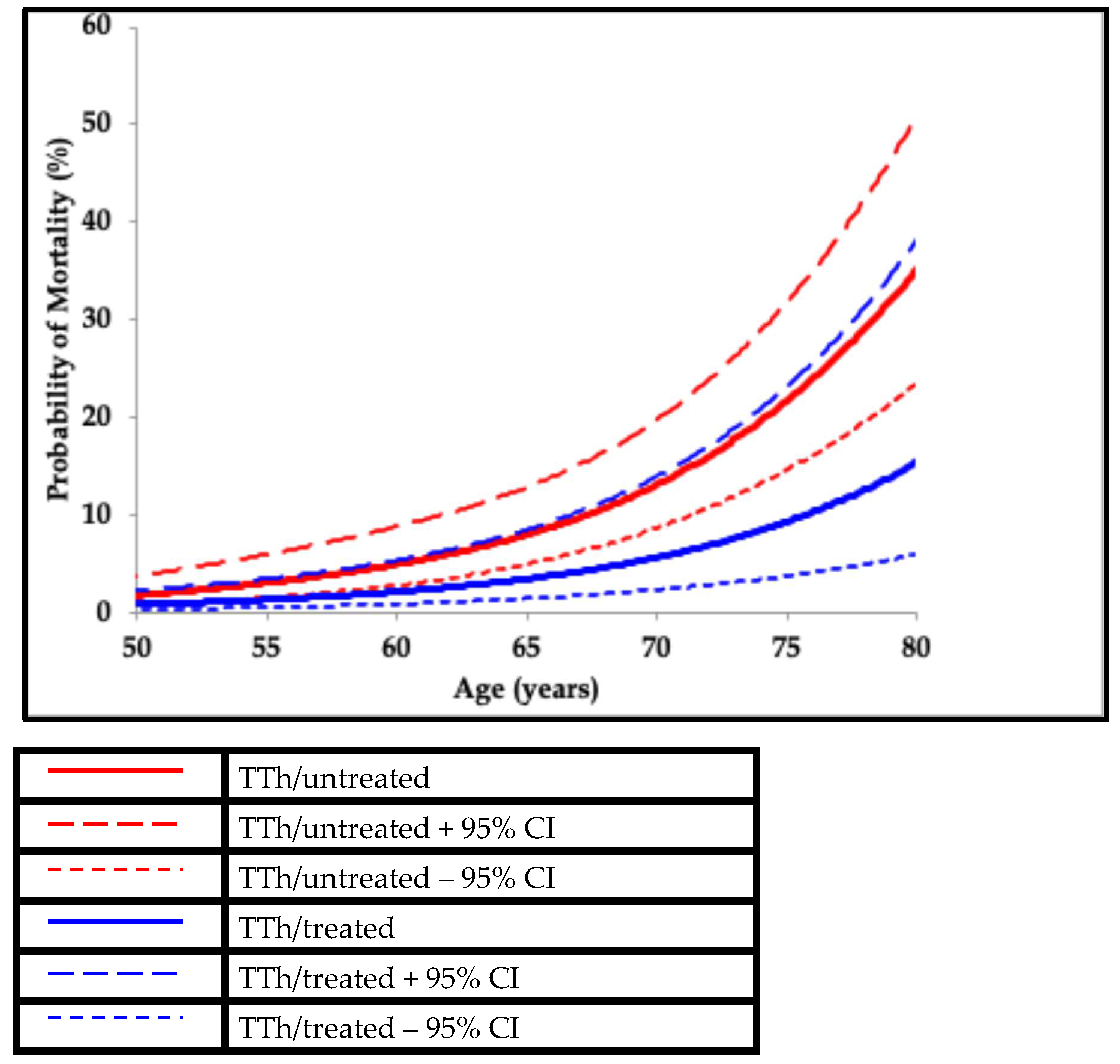

- Hackett G, Kirby M, Rees RW, Jones TH, Muneer A, Livingston M, Ossei-Gerning N, David J, Foster J, Kalra PA, Ramachandran S. The British Society for Sexual Medicine Guidelines on Male Adult Testosterone Deficiency, with Statements for Practice. World J Mens Health. 2023;41(3):508-537. [CrossRef]

- Pye SR, Huhtaniemi IT, Finn JD, Lee DM, O’Neill TW, Tajar A, Bartfai G, Boonen S, Casanueva FF, Forti G, Giwercman A, Han TS, Kula K, Lean ME, Pendleton N, Punab M, Rutter MK, Vanderschueren D, Wu FC; EMAS Study Group. Late-onset hypogonadism and mortality in aging men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(4):1357-66. [CrossRef]

- Antonio L, Wu FCW, Moors H, Matheï C, Huhtaniemi IT, Rastrelli G, Dejaeger M, O’Neill TW, Pye SR, Forti G, Maggi M, Casanueva FF, Slowikowska-Hilczer J, Punab M, Tournoy J, Vanderschueren D; EMAS Study Group. Erectile dysfunction predicts mortality in middle-aged and older men independent of their sex steroid status. Age Ageing. 2022;51(4):afac094. [CrossRef]

- Holmboe SA, Skakkebæk NE, Juul A, Scheike T, Jensen TK, Linneberg A, Thuesen BH, Andersson AM. Individual testosterone decline and future mortality risk in men. Eur J Endocrinol. 2018;178(1):123-130. [CrossRef]

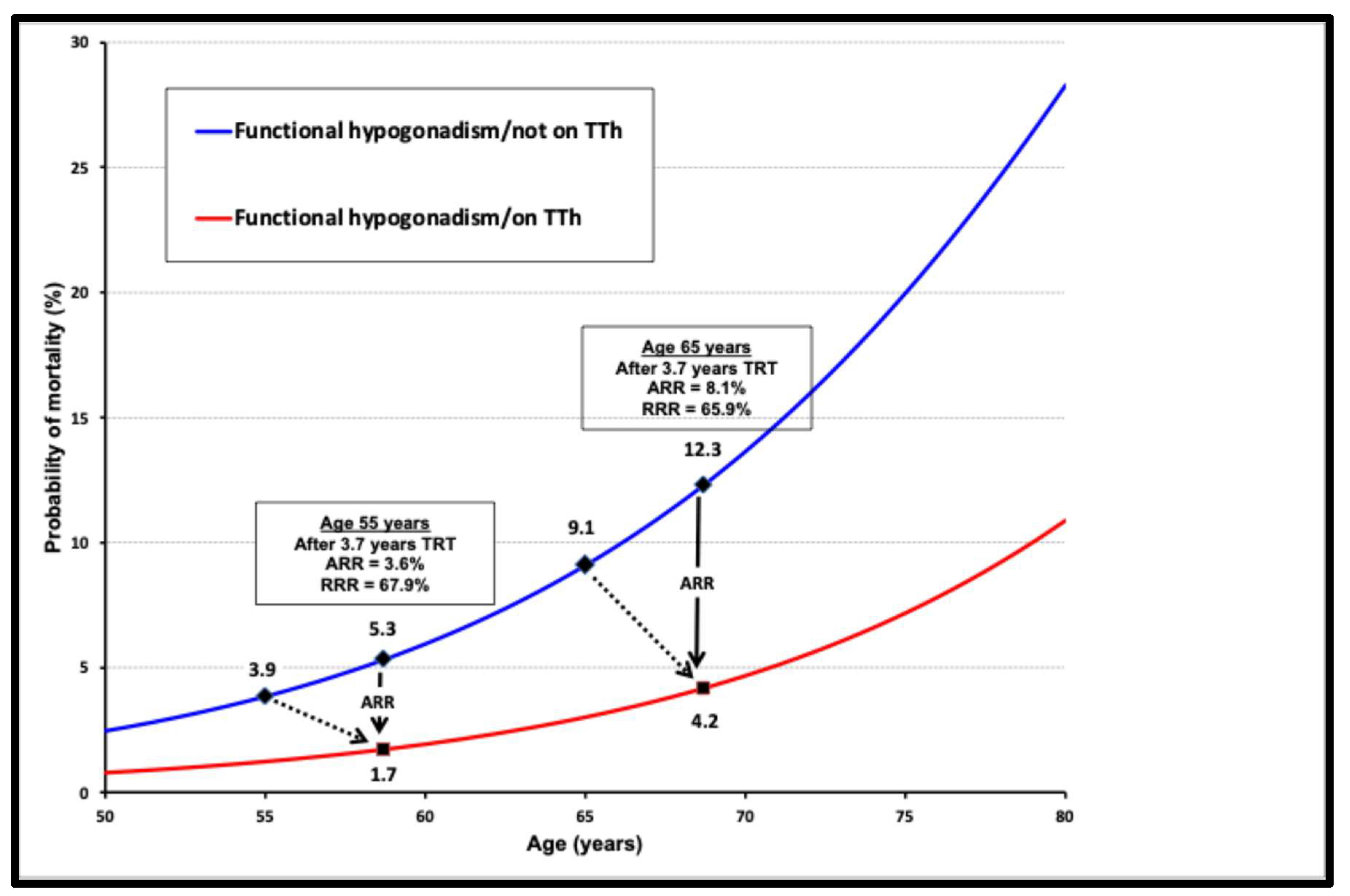

- Muraleedharan V, Marsh H, Kapoor D, Channer KS, Jones TH. Testosterone deficiency is associated with increased risk of mortality and testosterone replacement improves survival in men with type 2 diabetes. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;169(6):725-33. [CrossRef]

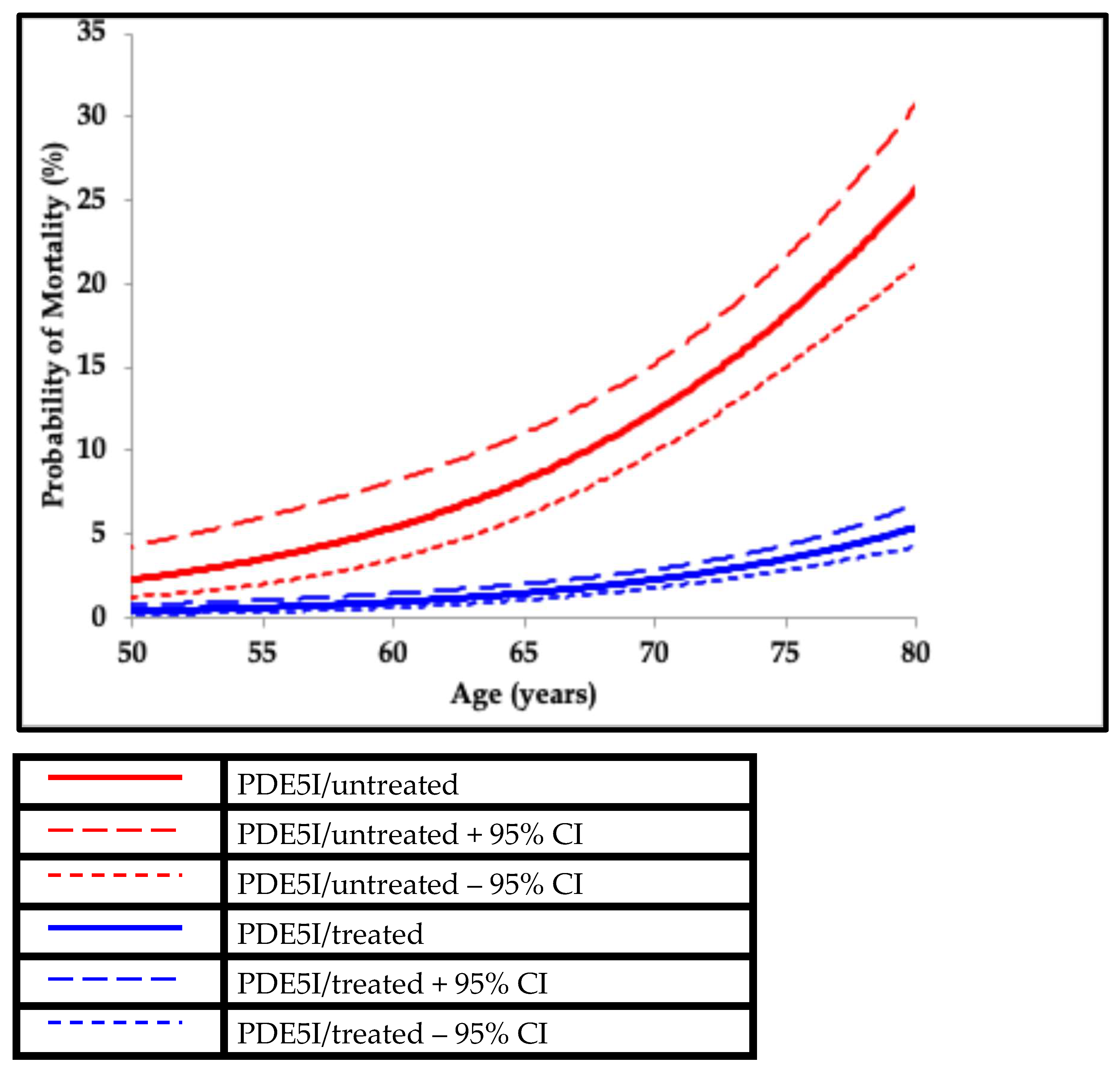

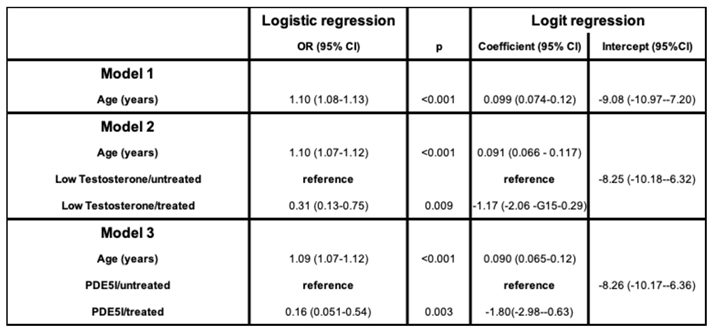

- Hackett G, Heald AH, Sinclair A, Jones PW, Strange RC, Ramachandran S. Serum testosterone, testosterone replacement therapy and all-cause mortality in men with type 2 diabetes: retrospective consideration of the impact of PDE5 inhibitors and statins. Int J Clin Pract. 2016;70(3):244-53. [CrossRef]

- Shores MM, Smith NL, Forsberg CW, Anawalt BD, Matsumoto AM. Testosterone treatment and mortality in men with low testosterone levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(6):2050-8. [CrossRef]

- Mann A, Strange RC, König CS, Hackett G, Haider A, Haider KS, Desnerck P, Ramachandran S. Testosterone replacement therapy: association with mortality in high-risk patient subgroups. Andrology. 2024;12(6):1389-1397. [CrossRef]

- Andersson DP, Trolle Lagerros Y, Grotta A, Bellocco R, Lehtihet M, Holzmann MJ. Association between treatment for erectile dysfunction and death or cardiovascular outcomes after myocardial infarction. Heart. 2017;103(16):1264-1270. [CrossRef]

- Anderson SG, Hutchings DC, Woodward M, Rahimi K, Rutter MK, Kirby M, Hackett G, Trafford AW, Heald AH. Phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitor use in type 2 diabetes is associated with a reduction in all-cause mortality. Heart. 2016;102(21):1750-1756. [CrossRef]

- Kloner RA, Stanek E, Desai K, Crowe CL, Paige Ball K, Haynes A, Rosen RC. The association of tadalafil exposure with lower rates of major adverse cardiovascular events and mortality in a general population of men with erectile dysfunction. Clin Cardiol. 2024;47(2):e24234. [CrossRef]

- Hackett G, Jones PW, Strange RC, Ramachandran S. Statin, testosterone and phosphodiesterase 5-inhibitor treatments and age related mortality in diabetes. World J Diabetes. 2017;8(3):104-111. [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood TB. Deciphering death: a commentary on Gompertz (1825) ‘On the nature of the function expressive of the law of human mortality, and on a new mode of determining the value of life contingencies’. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015;370(1666):20140379. [CrossRef]

- Hallén A. Makeham’s addition to the Gompertz law re-evaluated. Biogerontology. 2009;10(4):517-22. [CrossRef]

- Hackett G, Kirby M, Edwards D, Jones TH, Rees J, Muneer A. UK policy statements on testosterone deficiency. Int J Clin Pract. 2017;71(3-4):e12901. [CrossRef]

- Hackett G, Kirby M, Wylie K, Heald A, Ossei-Gerning N, Edwards D, Muneer A. British Society for Sexual Medicine Guidelines on the Management of Erectile Dysfunction in Men-2017. J Sex Med. 2018;15(4):430-457. [CrossRef]

- Kapoor D, Aldred H, Clark S, Channer KS, Jones TH. Clinical and biochemical assessment of hypogonadism in men with type 2 diabetes: correlations with bioavailable testosterone and visceral adiposity. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(4):911-7. [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran S, Bhartia M, König CS. The lipid hypothesis: From resins to Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type-9 inhibitors. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Drug Discovery 2020: 5: 48-81.

- Nissen SE, Lincoff AM, Brennan D, Ray KK, Mason D, Kastelein JJP, Thompson PD, Libby P, Cho L, Plutzky J, Bays HE, Moriarty PM, Menon V, Grobbee DE, Louie MJ, Chen CF, Li N, Bloedon L, Robinson P, Horner M, Sasiela WJ, McCluskey J, Davey D, Fajardo-Campos P, Petrovic P, Fedacko J, Zmuda W, Lukyanov Y, Nicholls SJ; CLEAR Outcomes Investigators. Bempedoic Acid and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Statin-Intolerant Patients. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(15):1353-1364. [CrossRef]

- Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, Koskinas KC, Casula M, Badimon L, Chapman MJ, De Backer GG, Delgado V, Ference BA, Graham IM, Halliday A, Landmesser U, Mihaylova B, Pedersen TR, Riccardi G, Richter DJ, Sabatine MS, Taskinen MR, Tokgozoglu L, Wiklund O; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(1):111-188. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2020 Nov 21;41(44):4255. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz826. [CrossRef]

- Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration; Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, Holland LE, Reith C, Bhala N, Peto R, Barnes EH, Keech A, Simes J, Collins R. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670-81. [CrossRef]

- Baigent C, Landray MJ, Reith C, Emberson J, Wheeler DC, Tomson C, Wanner C, Krane V, Cass A, Craig J, Neal B, Jiang L, Hooi LS, Levin A, Agodoa L, Gaziano M, Kasiske B, Walker R, Massy ZA, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Krairittichai U, Ophascharoensuk V, Fellström B, Holdaas H, Tesar V, Wiecek A, Grobbee D, de Zeeuw D, Grönhagen-Riska C, Dasgupta T, Lewis D, Herrington W, Mafham M, Majoni W, Wallendszus K, Grimm R, Pedersen T, Tobert J, Armitage J, Baxter A, Bray C, Chen Y, Chen Z, Hill M, Knott C, Parish S, Simpson D, Sleight P, Young A, Collins R; SHARP Investigators. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with simvastatin plus ezetimibe in patients with chronic kidney disease (Study of Heart and Renal Protection): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9784):2181-92. [CrossRef]

- Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, McCagg A, White JA, Theroux P, Darius H, Lewis BS, Ophuis TO, Jukema JW, De Ferrari GM, Ruzyllo W, De Lucca P, Im K, Bohula EA, Reist C, Wiviott SD, Tershakovec AM, Musliner TA, Braunwald E, Califf RM; IMPROVE-IT Investigators. Ezetimibe Added to Statin Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(25):2387-97. [CrossRef]

- Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, Honarpour N, Wiviott SD, Murphy SA, Kuder JF, Wang H, Liu T, Wasserman SM, Sever PS, Pedersen TR; FOURIER Steering Committee and Investigators. Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(18):1713-1722. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, Bhatt DL, Bittner VA, Diaz R, Edelberg JM, Goodman SG, Hanotin C, Harrington RA, Jukema JW, Lecorps G, Mahaffey KW, Moryusef A, Pordy R, Quintero K, Roe MT, Sasiela WJ, Tamby JF, Tricoci P, White HD, Zeiher AM; ODYSSEY OUTCOMES Committees and Investigators. Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2097-2107. [CrossRef]

- König CS, Mann A, McFarlane R, Marriott J, Price M, Ramachandran S. Age and the Residual Risk of Cardiovascular Disease following Low Density Lipoprotein-Cholesterol Exposure. Biomedicines. 2023;11(12):3208. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).