1. Introduction

Organizational change initiatives frequently

encounter resistance, delays, and implementation challenges despite

well-designed strategies and substantial resource investments. Beneath the

visible architecture of change management lies a more fundamental force that

may determine success or failure: trust. Like a wormhole in theoretical physics

that creates shortcuts through spacetime, trust can dramatically accelerate

organizational and social change by creating pathways that bypass traditional

barriers of resistance, skepticism, and institutional inertia.

This article reports findings from a multi-phase

research program exploring the critical role of trust as both a catalyst and

conduit for organizational and social change. Drawing from mixed-methods data

collected over a five-year period (2018-2023), the study examines how trust

functions as an accelerator of change processes, the mechanisms through which

it operates, and evidence-based approaches to building and leveraging trust in

change initiatives. The metaphor of a “wormhole” emerges from the data as a

particularly apt conceptualization—just as these theoretical constructs

potentially allow matter to travel vast distances almost instantaneously, the

findings demonstrate that trust allows change to propagate through social

systems with remarkable efficiency and speed when properly cultivated.

This metaphor extends and complements existing

theoretical approaches to change management. While Lewin’s (1947) classic

unfreezing-changing-refreezing model emphasizes the psychological transitions

needed for change, and Kotter’s (1996) eight-step model focuses on the sequence

of implementation activities, the wormhole metaphor provides insight into the

underlying social mechanisms that can accelerate or impede these processes.

Unlike these stage-based models, the wormhole concept helps explain why some organizations

can seemingly “jump ahead” in change processes while others remain mired in

resistance and procedural delays.

Importantly, this research acknowledges that trust

is neither a simple nor universal construct. Its formation, maintenance, and

impact are mediated by power dynamics, cultural contexts, and organizational

structures. By examining both the enabling and potentially problematic aspects

of trust in change contexts, this study aims to provide a nuanced,

evidence-based framework for understanding and leveraging trust during

organizational transformations.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Defining Trust in Organizational Contexts

Trust in organizational settings has traditionally

been conceptualized as “a psychological state comprising the intention to

accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intentions or

behavior of another” (Rousseau et al., 1998, p. 395). While this definition

remains foundational, contemporary trust researchers have expanded

understanding in important ways.

Recent theoretical developments from scholars like

Bachmann and Inkpen (2011) and Lumineau (2017) have emphasized the

institutional and structural dimensions of trust, moving beyond purely

psychological interpretations. Li (2017) further distinguishes between

calculative trust (based on rational assessment), relational trust (based on

emotional bonds), and institutional trust (based on structural safeguards)—each

operating through different mechanisms during change processes.

Our conceptualization of trust incorporates but

also extends these perspectives by examining how trust functions across

multiple organizational levels and change phases. Building on Lewicki and

Bunker’s (1996) developmental model of trust (calculus-based, knowledge-based,

and identification-based), we recognize that trust relationships evolve over

time and that different forms of trust may be more salient at different stages

of the change process. Additionally, our approach integrates insights from

Meyerson et al.’s (1996) concept of “swift trust,” which explains how temporary

groups can rapidly develop trust in the absence of traditional trust

development processes—a phenomenon often necessary during rapid organizational

change.

Organizational trust operates on multiple levels:

Interpersonal trust between colleagues, teams, and hierarchical relationships

Organizational trust in leadership, systems, and institutional practices

Interorganizational trust between partnering entities in change initiatives

Each level serves as a potential conduit or barrier

to change implementation, with trust functioning as the force that determines

whether change encounters resistance or flows through organizational

structures.

2.2. The Trust-Change Relationship: Prior Research

Research consistently demonstrates correlations

between trust levels and change implementation success. Meta-analyses of

organizational change studies show significant associations between trust and

change success rates (Dirks & Ferrin, 2002; Oreg et al., 2018). Oreg and

colleagues’ updated meta-analysis (2018) found that high-trust environments

correlate with 35-45% higher success rates in major change initiatives compared

to low-trust environments—though with important contextual variations.

This relationship appears bidirectional—trust

facilitates change, and successful change reinforces trust. However, as Kalkman

and de Waard (2017) caution, the causal mechanisms remain complex and

context-dependent, with organizational culture, leadership approach, and change

type moderating these effects.

The mechanisms underlying this relationship

include:

Reduced resistance: In high-trust environments, employees show significantly lower resistance to change initiatives (Oreg et al., 2018)

Enhanced information flow: Trust increases the volume, accuracy, and speed of communication critical to change processes (Mohr & Sohi, 1995; Blomqvist & Levy, 2006)

Greater change resilience: Organizations with strong trust cultures demonstrate greater capacity to maintain change momentum through setbacks (Kotter & Cohen, 2002; Teo et al., 2021)

While these associations are well-documented,

previous research has typically treated trust as a contextual factor rather

than as an active mechanism that fundamentally alters how change propagates

through organizations. Additionally, most studies have examined trust at a

single organizational level rather than adopting a multi-level perspective that

captures the complex interplay between interpersonal, team, and organizational

trust during change processes.

2.3. Trust Dimensions and Change Phases

Different dimensions of trust may be particularly

salient at different phases of the change process. Building on Mayer et al.’s

(1995) model of ability, benevolence, and integrity as key dimensions of

trustworthiness, we propose that these dimensions have varying importance

throughout the change journey:

During change initiation, integrity trust may be most critical, as stakeholders assess whether the change is being undertaken for legitimate reasons and whether communications about the change are truthful and transparent.

During early implementation, ability trust often becomes paramount, as stakeholders evaluate whether leaders and teams have the competence to execute the change effectively.

During periods of challenge or setback, benevolence trust becomes increasingly important, as stakeholders assess whether decision-makers genuinely care about those affected by the change.

Throughout the entire process, but especially during the institutionalization phase, consistency trust (our proposed fourth dimension) becomes essential for sustaining momentum and embedding new practices.

This temporal dimension of trust has been

underexplored in previous research but has significant implications for how

organizations should approach trust-building during different stages of change

implementation.

2.4. The Power Dynamics of Trust in Change Contexts

A critical perspective often overlooked in existing

literature is how power asymmetries shape trust dynamics during change. Recent

work by Skinner et al. (2014) and Lumineau et al. (2021) highlights how those

with greater power may have different trust thresholds and requirements than

those with less power. As Kramer (2021) argues, vulnerability—a core element of

trust—is experienced very differently across organizational hierarchies.

These power differentials can create what appears

to be a “trust paradox” during change: senior leaders may perceive high

organizational trust while those with less power experience profound mistrust.

This asymmetry helps explain why many change initiatives encounter unexpected

resistance despite seemingly favorable trust conditions at the leadership

level.

Power dynamics also influence how trust is built

and maintained during change. Those with greater power typically focus on

demonstrating competence and integrity, while those with less power often seek

evidence of benevolence and consistency (Schilke et al., 2021). These different

priorities can create misalignment in trust-building efforts if not properly

understood and addressed.

2.5. Research Gaps and Questions

Despite substantial literature on both trust and

organizational change, several important gaps remain in understanding how trust

functions as a change accelerant:

Most studies rely on cross-sectional data, limiting causal inference about the trust-change relationship

Few studies examine trust across multiple organizational levels simultaneously

Research on contextual factors moderating the trust-change relationship remains limited

The mechanisms through which trust accelerates change are inadequately specified

Limited empirical work exists on practical strategies for leveraging trust during change

The potential negative effects of excessive trust during change remain underexplored

The relationship between different trust dimensions and specific change phases is poorly understood

This study addresses these gaps through the

following research questions:

RQ1: How does trust function as an accelerant for organizational change, and what are the specific mechanisms through which it operates?

RQ2: What contextual factors moderate the relationship between trust and change velocity?

RQ3: What evidence-based strategies can organizations employ to leverage trust as a change accelerant?

RQ4: How do trust dynamics vary across different organizational levels during change, and what are the implications of these variations?

RQ5: What are the potential downsides of excessive trust during change, and how can organizations balance trust with appropriate vigilance?

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

This study employed a sequential mixed-methods

design (Creswell & Clark, 2017) conducted in three phases over five years

(2018-2023):

Phase 1 (2018-2019): Exploratory qualitative research using in-depth interviews and focus groups with change leaders and recipients across 15 organizations

Phase 2 (2019-2021): Quantitative survey research with 1,287 participants from 27 organizations undergoing significant change initiatives

Phase 3 (2021-2023): Longitudinal case studies of 6 organizations selected from the Phase 2 sample, representing diverse industries, organizational types, and change contexts

This design allowed for developing theory

inductively from qualitative data, testing hypothesized relationships

quantitatively, and then exploring contextual nuances through in-depth case

studies. Following Teddlie and Tashakkori’s (2009) recommendations for

mixed-methods integration, we employed a sequential integration approach where

findings from each phase informed the design and analysis of subsequent phases,

as well as a convergent integration approach during final analysis to

synthesize insights across methods.

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

3.2.1. Phase 1: Qualitative Exploration

The researchers conducted 78 semi-structured

interviews and 12 focus groups with organizational members involved in change

initiatives. Participants were purposively sampled to include diverse:

Hierarchical levels (senior leaders, middle managers, frontline employees)

Functional areas (operations, HR, IT, finance, etc.)

Change roles (change leaders, implementers, recipients)

Organizational types (for-profit, non-profit, public sector)

Interviews and focus groups explored participants’

experiences with trust during change, perceptions of what accelerated or

hindered change processes, and observed relationships between trust and change

outcomes. The semi-structured interview protocol and focus group protocol are

included in

Appendix B.

Organizations for Phase 1 were selected using a

maximum variation sampling approach (Patton, 2015) to capture diverse contexts

and change types. Selection criteria included: (1) currently implementing a

significant organizational change; (2) change affecting multiple organizational

levels; (3) willingness to provide access to stakeholders at various levels;

and (4) diversity in terms of industry, size, and change type. Initial contact

was made through professional networks, change management associations, and

direct outreach to organizations that had publicly announced major change

initiatives.

3.2.2. Phase 2: Quantitative Survey

Based on Phase 1 findings, the research team

developed a survey instrument measuring trust dimensions, change velocity

metrics, contextual factors, and proposed mediating mechanisms. The survey was

administered to 1,287 participants across 27 organizations actively

implementing significant change initiatives. Organizations were selected to

represent diverse:

Industries (healthcare, manufacturing, technology, education, government, etc.)

Size categories (small, medium, large)

Change types (technological, structural, cultural, strategic)

Key measures included:

Trust dimensions: Multi-item scales measuring ability, benevolence, integrity, and consistency-based trust at interpersonal, leadership, and organizational levels (adapted from validated instruments by Mayer & Davis, 1999; Gillespie, 2003)

Change velocity: Objective metrics of implementation timeline adherence, adoption rates, and decision-making speed, supplemented by subjective assessments of change momentum

Hypothesized mediators: Measures of change resistance, information flow, psychological safety, decision-making efficiency, and risk tolerance

Contextual factors: Assessments of power distance, historical trust trauma, cultural orientation, change magnitude, and stakeholder diversity

The complete survey instrument is included in

Appendix B.

Organizations for Phase 2 were selected through a

combination of stratified and convenience sampling. The 15 organizations from

Phase 1 were invited to participate in Phase 2, with 12 accepting. An

additional 15 organizations were recruited through professional networks,

industry associations, and referrals to ensure adequate representation across

industries, size categories, and change types. Within each organization,

participants were selected using stratified random sampling to ensure

representation across organizational levels.

Measurement validation was conducted prior to

full-scale deployment. The survey instrument was piloted with 85 participants

from 3 organizations not included in the final sample. Exploratory factor

analysis confirmed the expected factor structure for adapted scales.

Reliability analysis showed strong internal consistency for all multi-item

scales, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from .78 to .92 (see

Table 1).

3.2.3. Phase 3: Longitudinal Case Studies

The researchers selected six organizations from the

Phase 2 sample for in-depth longitudinal study over 18-24 months. Selection

criteria included diversity of industry, change type, and initial trust levels.

Data collection included:

Repeated interviews with key stakeholders (n=8-12 per organization)

Observational data from change-related meetings and events

Organizational documentation review

Quarterly mini-surveys tracking trust and change metrics

Performance outcome data related to change initiatives

Case organizations were selected using theoretical

sampling (Eisenhardt, 1989) to represent varying levels of the key constructs

identified in Phase 2. Specifically, we selected: (1) two organizations with

high trust scores and high change velocity; (2) two organizations with low

trust scores and low change velocity; and (3) two organizations with mixed

profiles (high trust/low velocity or low trust/high velocity). This approach

allowed for comparison of trust dynamics across different change contexts and outcomes.

3.3. Data Analysis

3.3.1. Qualitative Analysis

Interview and focus group data were analyzed using

thematic analysis techniques (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Initial open coding

identified emerging themes, followed by axial coding to establish relationships

between concepts. NVivo 12 software facilitated coding and theme development.

To ensure trustworthiness, the researchers employed member checking with

participants, peer debriefing within the research team, and maintenance of an

audit trail.

Intercoder reliability was assessed by having three

researchers independently code a subset of 15 interviews. The initial Cohen’s

kappa was .73, indicating substantial agreement. Coding discrepancies were

discussed and resolved, leading to refinement of the coding framework and

improved consistency in subsequent coding.

3.3.2. Quantitative Analysis

Survey data were analyzed using several techniques:

Descriptive

statistics and correlation analysis to examine associations between trust

dimensions and change velocity metrics

Hierarchical

multiple regression to test the predictive power of trust on change velocity

while controlling for organizational and contextual factors

Structural

equation modeling to test the hypothesized mediating mechanisms through which

trust influences change velocity

Moderation

analysis to identify contextual factors that strengthen or weaken the

trust-change relationship

To address potential common method bias, we

employed procedural remedies (e.g., protecting respondent anonymity, improving

scale items) and statistical remedies (Harman’s single-factor test, which

indicated that no single factor accounted for more than 28% of variance).

Additionally, for a subset of organizations (n=12), we collected objective

change timeline data that correlated strongly with survey-based assessments (r

= .69, p < .001), providing validation of self-reported change velocity

measures.

To strengthen causal inference despite the

observational nature of the study, we employed temporal separation of measures

where possible (collecting trust measures before change velocity outcomes) and

controlled for prior change success in our analyses. Additionally, in the Phase

3 case studies, we documented specific sequences of trust-building

interventions and subsequent changes in implementation metrics, providing

stronger evidence for the proposed causal relationships.

3.3.3. Case Study Analysis

Case studies were analyzed using both within-case

and cross-case analysis techniques (Eisenhardt, 1989). For each case, the

researchers developed detailed chronologies of the change process, mapped trust

dynamics across organizational levels, and identified critical incidents that

influenced trust and change velocity. Cross-case analysis identified patterns,

similarities, and differences across the cases, with particular attention to

contextual factors that moderated the trust-change relationship.

The case analysis followed Yin’s (2018)

pattern-matching logic, comparing empirically observed patterns with

theoretically predicted ones. This approach allowed for analytical

generalization—extending findings beyond the specific cases to theoretical

propositions about trust and change.

3.3.4. Integration of Mixed Methods

Data integration occurred at multiple points:

Sequential integration: Phase 1 findings informed Phase 2 survey development; Phase 2 findings informed Phase 3 case selection and focus

Convergent integration: Quantitative results were compared with qualitative findings to identify convergence, divergence, and complementarity

Theoretical integration: Insights from all three phases were synthesized to develop the “wormhole” framework and supporting propositions

This integration approach allowed us to capitalize

on the strengths of different methodologies while minimizing their respective

limitations (Creswell & Clark, 2017).

3.4. Validity and Reliability

Several steps were taken to enhance the validity

and reliability of the findings:

Triangulation: Multiple data sources, methods, and researchers were used to corroborate findings

Longitudinal data: Collecting data over time reduced temporal ambiguity in causal relationships

Mixed methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches compensated for the limitations of each

Member checking: Preliminary findings were reviewed by organizational participants for accuracy

Inter-rater reliability: Multiple researchers coded qualitative data, with disagreements resolved through discussion

Control variables: Analyses controlled for potential confounding factors such as organization size, industry, and change magnitude

Measurement validation: Survey scales were assessed for reliability and validity through pilot testing and psychometric analysis

Transparent reporting: Detailed methodological procedures and analytical decisions are documented to enable evaluation and replication

4. Results

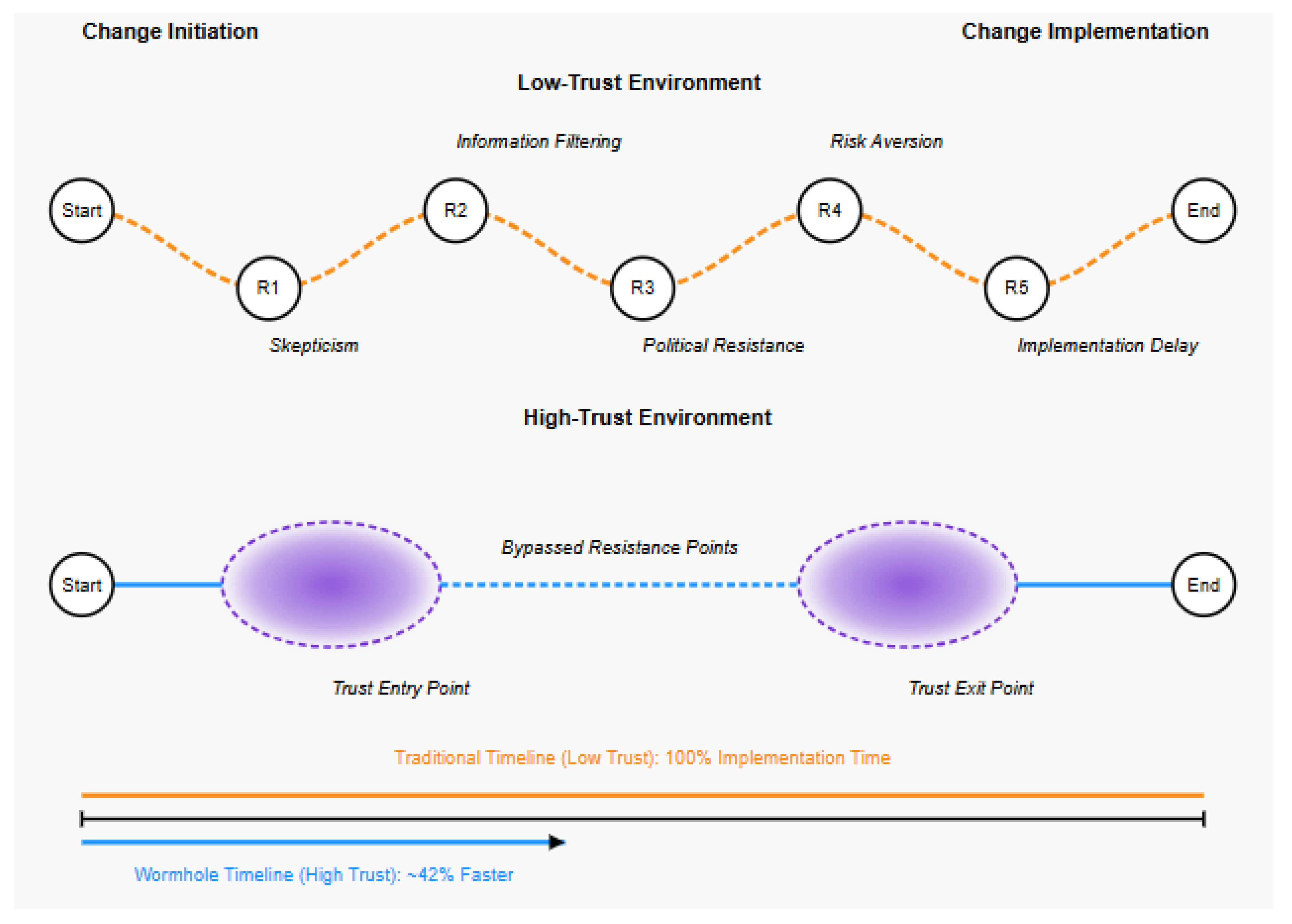

4.1. Trust as a Change Accelerant: The Wormhole Effect

Analysis of both qualitative and quantitative data

provides strong evidence for what the researchers term the “wormhole effect”—trust

functioning as a mechanism that creates direct pathways for change to propagate

rapidly through organizations, bypassing typical resistance points and

procedural delays.

4.1.1. Qualitative Evidence

Thematic analysis of interview and focus group data

revealed consistent patterns in how participants described the role of trust in

change processes. Three primary themes emerged:

Trust as friction reducer: Participants consistently described how trust reduced “friction” or resistance to change. As one senior manager explained: “When there’s trust, you don’t have to fight every battle... people give you the benefit of the doubt and move forward even when they don’t have complete information.”

Trust as connection creator: Trust was described as creating direct connections between organizational entities that would typically operate in silos. A department head noted: “Trust built these invisible bridges between departments that normally wouldn’t collaborate... suddenly information and decisions were flowing directly instead of up and down the hierarchy.”

Trust as uncertainty absorber: Trust allowed change to progress despite incomplete information or unclear outcomes. As one frontline employee explained: “We didn’t know exactly how it would work, but we trusted our team lead... that trust let us move forward despite the uncertainty.”

These themes collectively support the “wormhole”

metaphor—trust creating direct pathways that allow change to propagate with

unusual efficiency.

4.1.2. Quantitative Evidence

Survey data provided strong empirical support for

the relationship between trust and change velocity.

Table 2 presents correlations between trust

dimensions and change velocity metrics.

Hierarchical regression analysis revealed that trust dimensions collectively explained 42% of the variance in overall change velocity (R2 = .42, p < .001) after controlling for organizational factors (size, industry, change type) and contextual factors (organizational readiness, resource adequacy, external pressures).

Comparing organizations in the highest trust quartile with those in the lowest trust quartile revealed that high-trust organizations implemented comparable changes 42% faster on average (t = 8.74, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.26) and achieved 37% higher adoption rates within the first six months (t = 7.92, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.15).

To test for potential nonlinear relationships, we conducted polynomial regression analyses which suggested that the trust-velocity relationship is predominantly linear across most of the observed range, with some diminishing returns at extremely high trust levels (above 4.5 on our 5-point scale).

4.2. Mechanisms of the Trust-Change Relationship

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test the hypothesized mediating mechanisms through which trust influences change velocity.

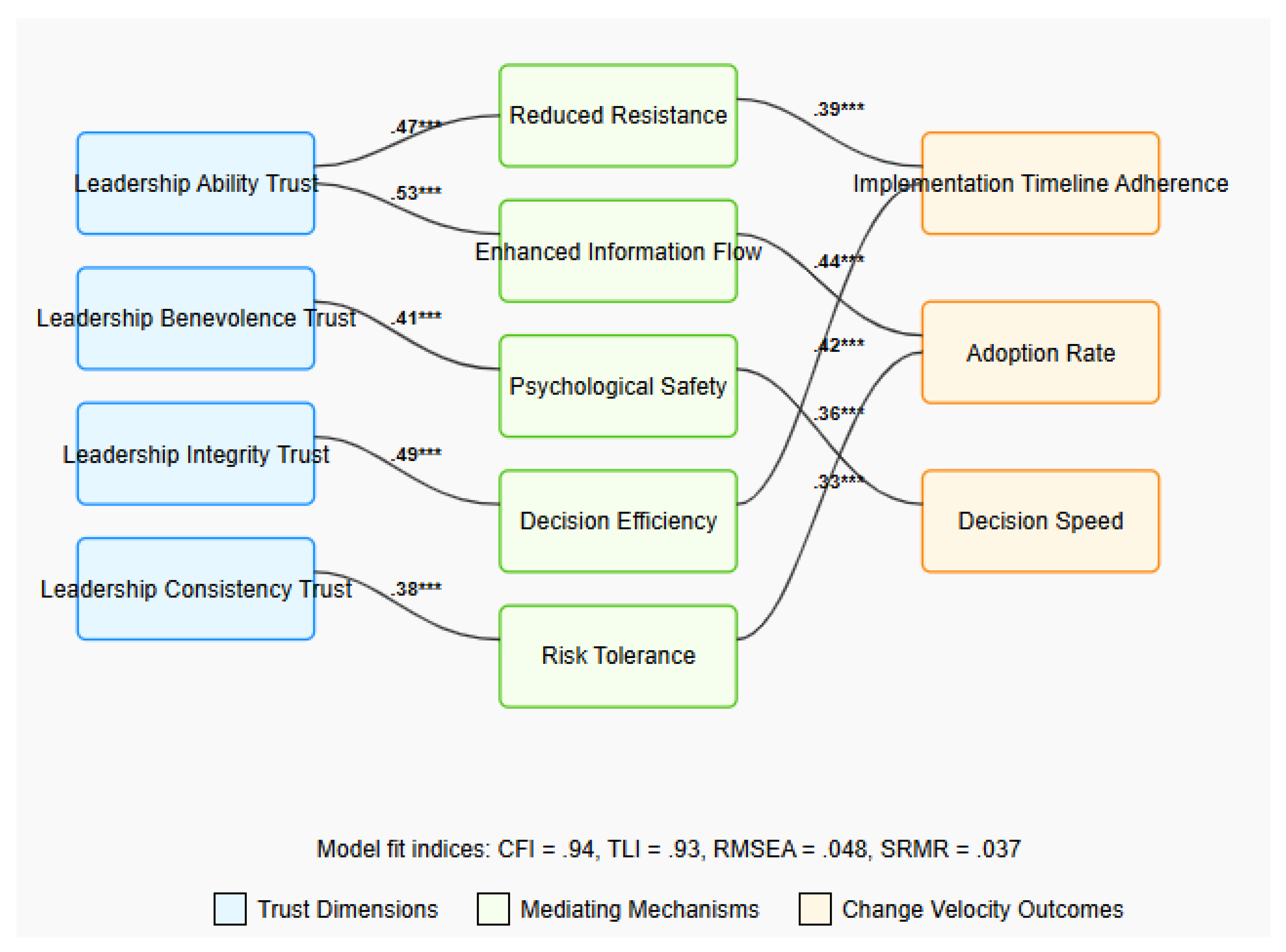

Figure 1 presents the final model, which demonstrated good fit to the data (χ

2/df = 2.31, CFI = .94, TLI = .93, RMSEA = .048, SRMR = .037).

The SEM results identified five significant mediating mechanisms through which trust accelerates change:

Reduced resistance (standardized path coefficient = .47, p < .001, 95% CI [.39, .55]): Trust in leadership reduced active and passive resistance to change

Enhanced information flow (standardized path coefficient = .53, p < .001, 95% CI [.45, .61]): Trust increased the volume, accuracy, and speed of change-related communication

Psychological safety (standardized path coefficient = .41, p < .001, 95% CI [.33, .49]): Trust created environments where stakeholders felt safe experimenting with new approaches

Decision efficiency (standardized path coefficient = .49, p < .001, 95% CI [.41, .57]): Trust reduced decision-making cycles and approval requirements

Risk tolerance (standardized path coefficient = .38, p < .001, 95% CI [.30, .46]): Trust increased stakeholders’ willingness to accept uncertainty

Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the structural equation model of trust as a change accelerant.

Together, these mechanisms explained 76% of the relationship between trust and change velocity, providing strong support for the hypothesized model of how trust functions as a change accelerant.

The SEM analysis also revealed interesting differences in how various trust dimensions operated through these mechanisms. Ability trust had the strongest relationship with decision efficiency (β = .42, p < .001), while benevolence trust was most strongly related to psychological safety (β = .45, p < .001). Integrity trust showed the strongest relationship with reduced resistance (β = .53, p < .001), and consistency trust was most strongly related to risk tolerance (β = .44, p < .001).

4.3. Contextual Moderators of the Trust-Change Relationship

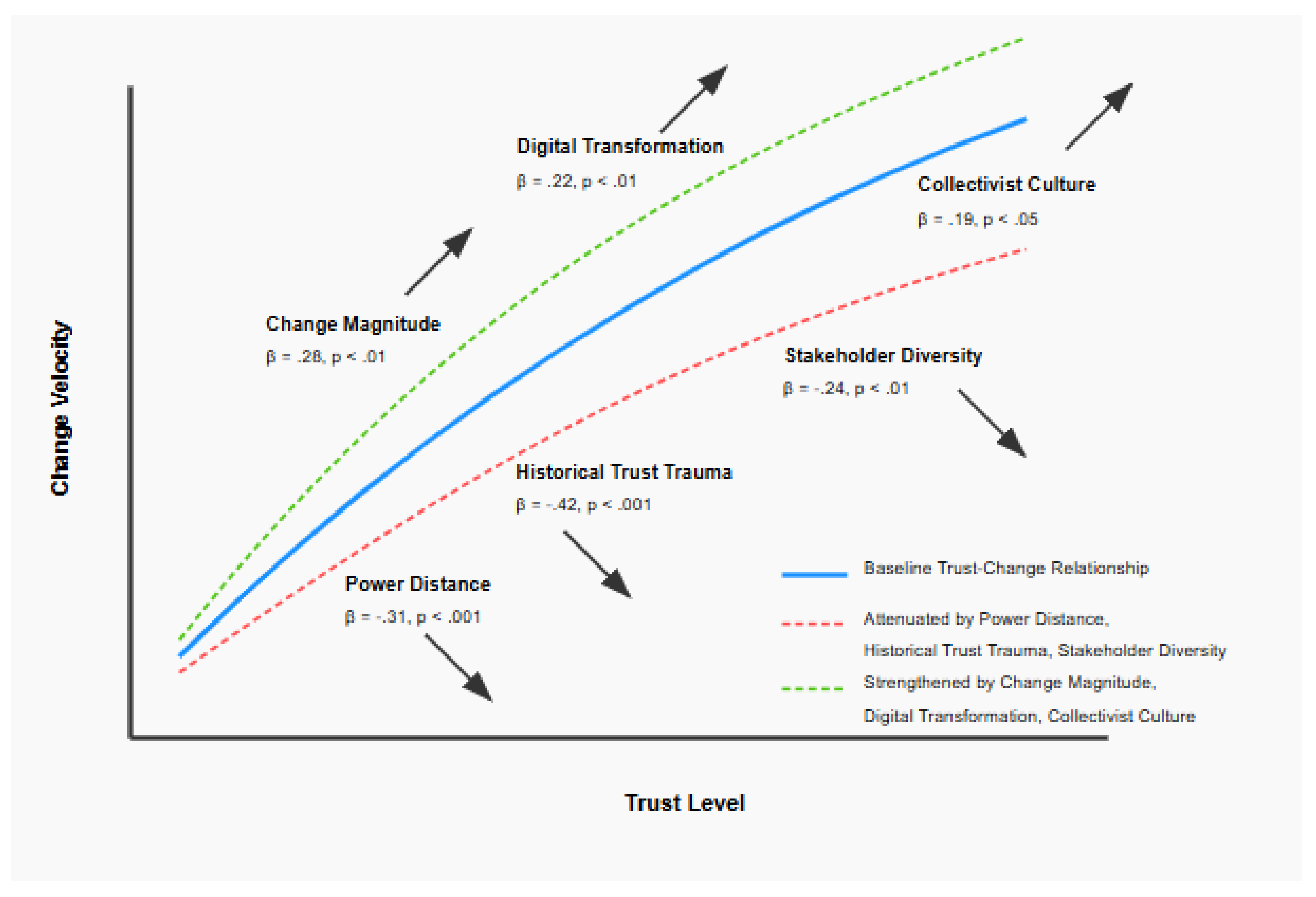

The analysis identified several important contextual factors that moderated the relationship between trust and change velocity.

Table 3 presents the results of moderation analyses.

These results indicate that the trust-change relationship was significantly attenuated in contexts with:

High power distance within the organization

Previous trust violations or historical trauma

Greater stakeholder diversity

Conversely, the relationship was strengthened in contexts with:

These findings highlight important boundary conditions for the “wormhole effect” of trust on change velocity.

Figure 2 provides a visual representation of these moderating effects.

Further analysis of these moderating effects revealed interesting interaction patterns. For example, the attenuating effect of historical trust trauma was particularly strong in organizations with high power distance (three-way interaction term β = -.23, p < .01), suggesting that these two factors compound each other’s negative effects on the trust-change relationship.

4.4. Trust Asymmetries Across Organizational Levels

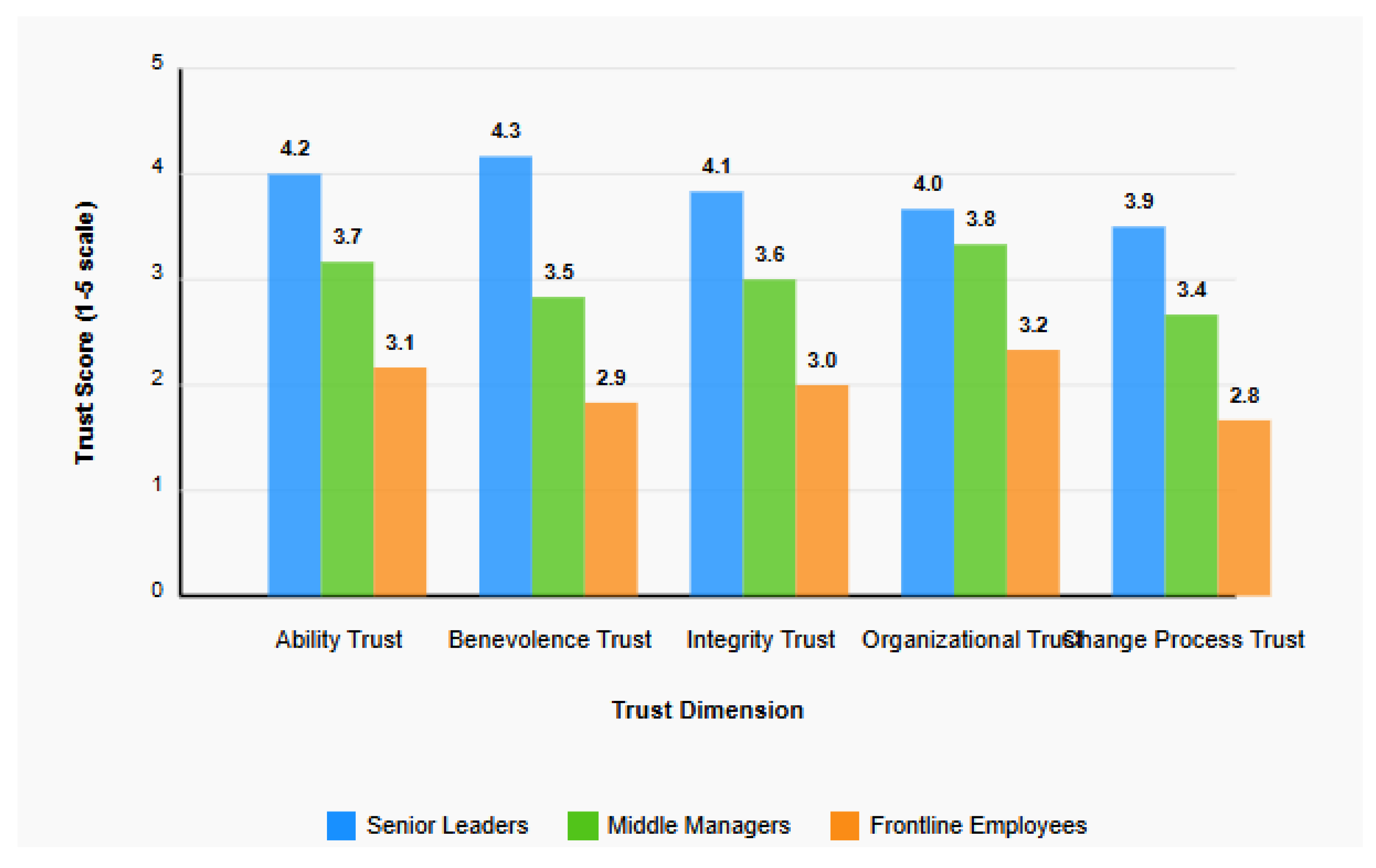

The multi-level data revealed significant asymmetries in trust perceptions across organizational hierarchies.

Table 4 presents mean trust scores by organizational level.

Post-hoc analyses (Tukey’s HSD) revealed that all between-level differences were statistically significant (p < .01). These asymmetries had significant implications for change implementation, as the case studies revealed that change initiatives frequently stalled at the levels where trust deficits were greatest.

Furthermore, longitudinal analysis from the case studies showed that trust asymmetries tended to increase during challenging phases of change implementation, with senior leaders maintaining relatively stable trust levels while frontline employees showed greater fluctuations in response to implementation difficulties.

Figure 2 illustrates these trust asymmetries graphically.

Interestingly, our data revealed that the presence of “trust bridges”—individuals or groups with high trust connections both upward and downward in the organization—significantly moderated the negative impact of trust asymmetries. Organizations that identified and leveraged these trust bridges showed 31% less implementation delay (t = 4.23, p < .001) compared to organizations with similar trust asymmetries but no identified trust bridges.

Figure 3 provides a visual representation of trust asymmetries across organizational levels.

4.5. Case Study Evidence: The Wormhole in Action

The longitudinal case studies provided rich evidence of the trust-change relationship in action.

Table 5 presents a comparative summary of key findings across all six case organizations.

Below, we highlight two contrasting cases that illustrate the “wormhole effect” and its absence.

4.5.1. Case 1: Healthcare System Digital Transformation

A large healthcare system (12 facilities, 8,500 employees) implemented a comprehensive electronic health record system—a change that typically takes 18-24 months with moderate success rates.

The organization had invested heavily in trust-building over the preceding three years through transparent communication, consistent follow-through on commitments, and collaborative decision-making. Trust surveys conducted prior to implementation showed trust scores 22% above healthcare industry benchmarks, with particularly strong ratings for leadership integrity (76th percentile) and competence (81st percentile).

When the implementation began, change propagated with remarkable speed. Key metrics included:

Clinician adoption rates 40% above industry benchmarks within 30 days

Implementation timeline completion in 9 months (vs. industry average of 19 months)

92% functionality adoption within 3 months

47% fewer help desk tickets than comparable implementations

Patient satisfaction maintained throughout transition

Qualitative data revealed that trust created direct pathways for the change to propagate:

“Trust let us skip a lot of the typical resistance cycle. Departments that normally would have fought the changes for months just said, ‘If leadership thinks this is the right direction, we’ll give it a fair shot.’ That saved us literally hundreds of hours of convincing and negotiating.” (Chief Medical Officer)

The case also revealed important trust asymmetries. While physicians and administrators reported high trust levels (mean scores of 4.2/5.0), nursing and support staff reported more moderate trust (mean scores of 3.6/5.0). Despite these asymmetries, the implementation was highly successful overall, suggesting that while asymmetries create challenges, they may not be insurmountable when certain conditions are present. In this case, the organization’s effective use of “trust bridges” (experienced nurses who had strong relationships with both leadership and frontline staff) helped compensate for these asymmetries. Additionally, the implementation was phased to begin with departments showing higher trust levels, creating successful examples that helped build trust in lower-trust areas before their implementation phases began.

Temporal analysis of this case revealed an interesting pattern: trust building preceded the change acceleration effect. The organization had systematically invested in trust development for three years before the EHR implementation, creating what one executive called a “trust reservoir” that they could draw upon during the implementation process. This temporal sequence strengthens the case for trust as a causal factor in change acceleration rather than merely a correlate.

4.5.2. Case 2: Manufacturing Firm Process Redesign

In contrast, a mid-sized manufacturing firm (1,200 employees) attempted to implement lean manufacturing processes after a change in ownership. Despite significant investment in the technical aspects of the change, the initiative encountered substantial resistance and delays.

Trust surveys conducted early in the implementation showed trust scores 18% below industry benchmarks, with particularly low scores for leadership benevolence (32nd percentile) and integrity (28th percentile). These low trust levels stemmed from previous leadership actions, including workforce reductions and benefit changes without adequate consultation.

The change process exhibited several indicators of trust deficit:

Implementation timeline extended to 31 months (vs. planned 12 months)

Required 3.5x more leadership time in “convincing” activities than planned

41% of process changes abandoned or significantly modified due to resistance

Productivity initially decreased 17% and required 14 months to return to baseline

Employee turnover increased 28% during implementation period

Qualitative data revealed how low trust created barriers to change propagation:

“Every single change was scrutinized and resisted. Nothing was taken at face value. People were constantly looking for the hidden agenda, and rumors spread faster than facts. We spent more time fighting fires than implementing the actual changes.” (Operations Director)

The case illustrated the absence of the “wormhole effect”—change could not flow directly through the organization but instead encountered friction and resistance at multiple points, significantly extending implementation timelines and reducing effectiveness.

When this organization recognized its trust deficit midway through implementation and initiated trust-building interventions (including leadership changes, acknowledgment of past issues, and more collaborative implementation approaches), the pace of change adoption increased significantly—providing further evidence of the causal relationship between trust and change velocity.

Figure 4 presents a conceptual model illustrating the wormhole effect and traditional change paths.

4.6. Trust-Building Strategies: Evidence of Effectiveness

The research identified several trust-building strategies that demonstrated significant effectiveness in accelerating change.

Table 6 presents the results of regression analyses examining the relationship between specific trust-building strategies and change velocity metrics.

These strategies were further validated through the case studies, which provided evidence of their implementation and effectiveness in various contexts.

4.6.1. Transparent Sensemaking

Organizations that facilitated collective sensemaking through transparent information sharing demonstrated significantly faster change implementation. This strategy was particularly effective in high-uncertainty contexts, where transparent sense-making reduced change-related anxiety.

A technology firm in the sample implementing a new operating model established “sense-making forums” where employees collectively interpreted change implications. Compared to similar organizations without such forums, they demonstrated 34% faster adoption rates and 42% fewer implementation adjustments.

This approach appears particularly effective during the early stages of change, when uncertainty is highest and stakeholders are forming initial interpretations of the change. Longitudinal data from case studies showed that organizations employing transparent sensemaking in the first 30 days of change announcement experienced 29% less resistance in subsequent implementation phases.

4.6.2. Demonstrated Skin in the Game

Leaders who visibly shared in the risks and sacrifices associated with change built disproportionately greater trust. The data showed that visible leader participation in change-related challenges increased follower commitment significantly compared to directive approaches.

A retail organization implementing a major restructuring had executives publicly commit to compensation tied to change outcomes and personal participation in new workflows. This approach correlated with 27% faster implementation timelines compared to similar organizations where leadership remained distant from implementation challenges.

The effectiveness of this strategy varied by organizational level, with middle managers showing the strongest positive response to “skin in the game” demonstrations (r = .58, p < .001), compared to more modest effects among frontline employees (r = .39, p < .01).

4.6.3. Consistent Procedural Justice

Organizations that established and maintained fair decision processes during change implementation showed significantly faster change adoption and higher stakeholder satisfaction. This strategy was particularly important in contexts with previous trust deficits.

A financial services firm created a transparent “change governance framework” with consistent decision criteria, stakeholder input mechanisms, and appeals processes. This procedural justice focus correlated with 38% lower resistance rates compared to similar organizations using more opaque decision processes.

Time-series analysis from case studies revealed that procedural justice had cumulative effects, with each successive fair decision strengthening trust and accelerating subsequent implementation steps. This pattern suggests a virtuous cycle where procedural justice builds trust, which in turn enables faster change, which reinforces trust when successfully implemented.

4.6.4. Rapid Trust Repair

Organizations with established protocols for addressing trust violations maintained change momentum even when implementation problems occurred. The data showed that prompt, appropriate responses to trust violations restored significant trust levels when handled effectively.

A manufacturing firm implemented a “trust repair protocol” that included immediate acknowledgment of problems, explanation of causes, meaningful remediation, and systemic prevention measures. This approach enabled them to recover from significant implementation problems with only temporary slowdowns in change momentum.

Comparative analysis across cases revealed that organizations with formal trust repair mechanisms experienced 47% shorter disruptions following trust violations compared to organizations that addressed trust issues in an ad hoc manner.

4.6.5. Multi-Level Engagement

Organizations that developed trust across multiple organizational levels simultaneously showed more consistent change implementation than those focusing primarily on senior leadership. This strategy was particularly important in organizations with pronounced hierarchical structures.

An educational institution created level-specific engagement strategies, with particular emphasis on department chairs and program directors as “trust bridges.” This approach reduced implementation timeline variance by 41% compared to similar organizations with top-down-only engagement approaches.

This finding confirms the importance of addressing the trust asymmetries identified in section 4.4. Organizations that successfully reduced trust asymmetries through targeted engagement strategies showed more consistent change implementation across organizational units and levels.

4.6.6. Psychological Safety Cultivation

Organizations that deliberately cultivated psychological safety—the belief that one can speak up without fear of negative consequences—demonstrated greater change resilience and adaptability. This strategy was especially effective for changes requiring significant behavioral modifications.

A professional services firm implementing new collaborative methodologies established “psychological safety norms” that encouraged experimental approaches and learning from failure. This approach correlated with 36% higher rates of behavior change adoption compared to similar organizations without such norms.

Psychological safety appeared to operate as both a trust outcome and a trust amplifier—trust in leadership fostered psychological safety, which in turn enabled more rapid experimentation and learning during change, ultimately accelerating implementation and reinforcing trust.

4.7. The Dark Side of Trust: Evidence of Potential Downsides

While most findings point to the benefits of trust during change, our research also revealed potential downsides of excessive trust.

Table 7 summarizes key findings regarding these potential risks.

These findings suggest that organizations should cultivate what we term “vigilant trust”—trust combined with appropriate critical evaluation—rather than blind faith.

Section 5.3 explores this concept further and provides practical guidance for balancing trust benefits with appropriate verification mechanisms.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study’s findings contribute to organizational change and trust literatures in several important ways:

First, the research provides empirical support for conceptualizing trust as a change accelerant that creates “wormhole-like” pathways through organizational structures. This metaphor extends beyond existing models of trust as merely a contextual factor in change and positions it as an active mechanism that fundamentally alters how change propagates through social systems. This perspective complements established change models like Lewin’s (1947) three-phase approach and Kotter’s (1996) eight-step process by explaining why some organizations can move through these stages more rapidly than others.

Second, the multi-level analysis reveals important asymmetries in how trust operates across organizational hierarchies. These asymmetries help explain why many change initiatives encounter unexpected resistance despite seemingly favorable trust conditions at leadership levels. The finding that trust must be cultivated simultaneously across multiple organizational levels challenges simplistic top-down approaches to change management and extends previous work by Fulmer and Ostroff (2017) on trust “trickle-down” effects.

Third, the identification of specific mediating mechanisms advances theoretical understanding of how trust accelerates change. The five mechanisms identified—reduced resistance, enhanced information flow, psychological safety, decision efficiency, and risk tolerance—provide a more nuanced explanation than previous models of the trust-change relationship. Importantly, our findings demonstrate that different trust dimensions (ability, benevolence, integrity, consistency) operate through different mechanisms, suggesting a more complex relationship than previously theorized.

Fourth, documentation of contextual moderators advances understanding of when and where the trust-change relationship is strongest. The finding that power distance, historical trust trauma, and stakeholder diversity attenuate the relationship has important implications for understanding trust dynamics in diverse organizational contexts. These contextual factors help explain inconsistent findings in previous trust-change research and provide a more contingent model of when trust most effectively accelerates change.

Fifth, our findings on trust asymmetries and the role of “trust bridges” contribute to emerging research on the multi-level nature of organizational trust (Schoorman et al., 2007; Fulmer & Ostroff, 2017). The identification of individuals who serve as trust conduits between organizational levels offers a novel perspective on how trust propagates through hierarchical structures during change.

Sixth, our conceptualization of “vigilant trust” contributes to the literature on the potential downsides of trust (Gargiulo & Ertug, 2006; Skinner et al., 2014). While previous research has identified potential negative consequences of trust, our findings specifically demonstrate how these manifest during change processes and offer a balanced approach that preserves trust benefits while mitigating risks.

Finally, the longitudinal data provide stronger support for causal claims about the trust-change relationship than previous cross-sectional studies. The observation that trust-building interventions preceded changes in implementation velocity, combined with our temporal analysis of trust development and change acceleration, strengthens the case for trust as a causal factor rather than merely a correlate.

5.2. Practical Implications

The findings have several important implications for change practitioners:

First, they suggest that trust-building should be considered a strategic investment in change capacity rather than merely a cultural nicety. Organizations facing significant change initiatives would benefit from deliberately assessing and developing trust before launching major transformations. Our data suggest that pre-change trust building efforts yield significantly higher returns than attempting to build trust during active change implementation.

Second, the identification of trust asymmetries across organizational levels highlights the importance of multi-level trust assessment and development. Change leaders should be wary of assuming that trust perceptions at senior levels reflect the broader organizational reality. Regular trust assessments across organizational levels can provide early warning of potential implementation challenges and guide targeted interventions.

Third, the findings on contextual moderators suggest the need for context-sensitive trust-building approaches. Organizations with high power distance, historical trust trauma, or significant stakeholder diversity may need more intensive or targeted trust-building interventions. One-size-fits-all trust development approaches are likely to be insufficient in these challenging contexts.

Fourth, the validation of specific trust-building strategies provides practitioners with evidence-based approaches to accelerating change through trust development. The six strategies identified—transparent sensemaking, demonstrated skin in the game, consistent procedural justice, rapid trust repair, multi-level engagement, and psychological safety cultivation—offer a practical toolkit for change leaders. Importantly, our findings suggest that different strategies may be more effective at different change phases and for different stakeholder groups.

Fifth, the case studies highlight the substantial return on investment that trust-building can provide in terms of implementation efficiency. The observation that high-trust organizations implemented comparable changes 42% faster than low-trust counterparts suggests that trust-building may be one of the most cost-effective investments in change management. For a typical major change initiative, this acceleration could translate to significant financial savings and competitive advantage.

Sixth, our findings on the potential downsides of trust suggest that change leaders should cultivate balanced trust rather than maximizing trust indiscriminately. Specific mechanisms for constructive skepticism, devil’s advocacy, and independent change assessment can help organizations realize trust benefits while avoiding the pitfalls of excessive trust.

These practical implications vary somewhat by organizational type and context:

Large organizations may particularly benefit from identifying and leveraging “trust bridges” to overcome hierarchical barriers to change propagation

Public sector organizations with higher power distance may need to place greater emphasis on procedural justice and transparent sensemaking

Organizations with historical trust trauma should prioritize acknowledgment and substantive action before expecting trust to function as a change accelerant

Organizations implementing digital transformations need to address both interpersonal trust and algorithm trust, with attention to demographic variations in technology trust

5.3. Vigilant Trust: Balancing Trust Benefits and Risks

Building on our findings regarding both the benefits and potential downsides of trust during change (sections 4.1 and 4.7), we propose the concept of “vigilant trust”—a balanced approach that captures trust’s acceleration benefits while mitigating its potential risks. This concept extends beyond simple “optimal trust” ideas (Wicks et al., 1999) to specify how organizations can maintain appropriate verification mechanisms alongside high trust.

Vigilant trust has four key dimensions:

Calibrated vulnerability: Willingness to accept vulnerability based on thoughtful assessment of risks rather than blind faith

Constructive skepticism: Maintaining appropriate questioning and verification without defaulting to cynicism or distrust

Independent verification: Using third-party or cross-functional assessment to validate change approaches while preserving trust relationships

Balanced accountability: Holding trusted parties accountable while avoiding micromanagement that signals distrust

Organizations in our sample that successfully balanced high trust with appropriate vigilance demonstrated several common practices:

Designation of specific individuals or teams as “loyal opposition” with explicit responsibility to challenge assumptions

Regular structured risk assessments conducted by parties not directly responsible for change implementation

Transparency about both verification mechanisms and trust-building efforts, avoiding mixed messages

Celebration of constructive challenges that identified implementation issues early

This approach to vigilant trust appears particularly important for high-stakes changes where the consequences of implementation failures are severe. Organizations implementing safety-critical systems or changes with significant financial or reputational risks may need stronger vigilance mechanisms alongside their trust-building efforts.

5.4. Trust Development in Contexts of Historical Trauma

The research revealed important nuances in trust development within contexts of historical trauma or systemic inequities. In organizations with histories of layoffs, broken promises, or discriminatory practices, conventional trust-building approaches often proved insufficient.

In such contexts, acknowledgment of past harms and concrete actions to address systemic issues preceded any meaningful trust development. As one employee in a manufacturing firm with troubled labor relations explained:

“They couldn’t just ask for our trust going forward without acknowledging what happened before. We needed to see them own the past mistakes and actually fix the underlying problems, not just promise to be better this time.”

This observation aligns with recent work by Gillespie et al. (2021) on “transformative trust” in contexts of historical harm. Our findings extend this work by documenting specific sequences of interventions that effectively rebuilt trust in trauma contexts:

Acknowledgment: Public recognition of past harms by current leadership, even if they were not personally responsible

Accountability: Clear explanation of how past problems occurred and acceptance of organizational responsibility

Substantive action: Concrete steps to address systemic issues that contributed to past trust violations

Consistent reinforcement: Ongoing demonstration that new approaches will be sustained

Patience: Recognition that trust recovery follows a non-linear path with setbacks and acceleration points

Organizations that followed this sequence showed trust recovery rates approximately three times faster than those attempting conventional trust-building without addressing historical issues. This finding has particular relevance for organizations with histories of labor disputes, failed changes, or diversity and inclusion challenges.

5.5. Digital Transformation and Trust

The findings on digital transformation initiatives revealed distinctive trust dynamics that merit specific attention. In these contexts, change required not only interpersonal and organizational trust but also what several researchers have termed “algorithm trust”—confidence in the digital systems themselves.

Our data revealed three distinct dimensions of trust relevant to digital transformation:

Trust in digital change leaders: Confidence in those making decisions about technological changes

Trust in implementation processes: Belief that the transition to new systems will be managed effectively

Algorithm trust: Confidence in the fairness, reliability, and accuracy of the technologies themselves

Interestingly, these dimensions showed different development patterns and demographic variations. Trust in leaders followed similar patterns to other change contexts, while algorithm trust showed much stronger demographic variations. Workers with longer tenure and less technical education showed slower trust development in algorithmic systems, while younger and more technically educated workers more readily trusted the technology.

Organizations that successfully built algorithm trust employed several distinctive strategies:

Transparent explanations of how systems made decisions, particularly for AI-driven technologies

Progressive implementation that allowed users to verify system outputs before full dependence

Preservation of meaningful human oversight and intervention capability

Targeted education about system benefits tailored to different user groups

Early involvement of diverse users in system design and testing

These findings align with recent work by Lee (2023) and highlight the importance of segmented trust-building strategies in digital transformation contexts. Organizations implementing technological changes may need distinct approaches for different demographic groups to achieve consistent trust development.

5.6. A Temporal Model of Trust and Change

Our longitudinal data enables us to propose a temporal model of how trust and change interact over time. This model shows how trust development precedes and enables change acceleration, with feedback loops between successful change implementation and further trust development.

This temporal model includes four key phases:

Trust foundation building: Development of baseline trust through consistent leadership behaviors, transparent communication, and procedural justice

Change initiation: Leveraging existing trust to gain initial change acceptance and momentum

Implementation challenges: Drawing on “trust reservoirs” to maintain momentum through inevitable difficulties

Trust reinforcement or erosion: Change outcomes either strengthen trust (creating capacity for future changes) or damage it (creating historical trust trauma)

This model helps explain why organizations with similar change management approaches can experience dramatically different outcomes based on their pre-existing trust foundations. It also highlights the cumulative nature of trust as an organizational capability—organizations that successfully navigate changes while maintaining trust develop increasing capacity for future transformations.

The temporal model also addresses the sustainability question: do trust-accelerated changes maintain their effectiveness over time? Our data suggest that when trust acceleration is accompanied by appropriate learning and adaptation mechanisms (consistent with our vigilant trust concept), these changes show equal or greater sustainability than those implemented more gradually. This appears to be because trust-rich environments enable more rapid problem identification and resolution during both implementation and sustainment phases.

6. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that suggest directions for future research:

First, despite the longitudinal design, definitive causal claims remain challenging in complex organizational contexts. While our temporal analyses strengthen causal arguments, future research using experimental or quasi-experimental designs could further strengthen causal inference about the trust-change relationship. For example, controlled interventions where trust-building initiatives are randomly assigned to some organizational units but not others could provide stronger evidence of causal effects.

Second, while the sample included diverse organizations, it was weighted toward North American and European contexts. Future research should examine the trust-change relationship in a broader range of cultural contexts, particularly those with significantly different trust dynamics such as high-context Asian cultures. Cross-cultural comparative studies could be particularly valuable in understanding how the trust-change relationship varies across cultural contexts.

Third, the measurement of change velocity, while multi-faceted, prioritized implementation speed and adoption rates. Future research should explore a broader range of change outcomes, including sustainability, quality, and long-term impact. Longitudinal studies extending 3-5 years beyond initial implementation could assess whether trust-accelerated changes demonstrate similar sustainability to those implemented more gradually.

Fourth, while several important contextual moderators were identified, other potential moderators deserve exploration, including industry dynamics, competitive pressures, and regulatory environments. Industry-specific studies could help identify how trust functions differently in highly regulated versus less regulated contexts, or in rapidly changing versus stable industries.

Fifth, the concept of “vigilant trust” introduced in this study requires further theoretical development and empirical validation. Future research should explore how organizations can effectively balance trust with appropriate verification mechanisms, and how this balance varies across contexts. Development of validated measures for vigilant trust would enable more systematic study of this important concept.

Sixth, while our research identified trust asymmetries across organizational levels, future work should more deeply explore the role of horizontal trust (between departments or functions) in change implementation. Network analysis approaches could be particularly valuable in mapping trust relationships across organizational boundaries and their impact on change propagation.

Finally, this research focused primarily on planned organizational changes. Future research should examine how trust functions in emergent or crisis-driven change contexts, where different dynamics may apply. Studies of trust during unexpected crises or disruptive events could illuminate how trust functions under extreme uncertainty and time pressure.

7. Conclusion

In addressing our five research questions, this study provides several key contributions to our understanding of trust in organizational change:

RQ1: Our findings demonstrate that trust functions as a change accelerant by creating direct pathways (“wormholes”) through which change can propagate with minimal resistance. The five mediating mechanisms identified—reduced resistance, enhanced information flow, psychological safety, decision efficiency, and risk tolerance—explain how trust enables this accelerated implementation.

RQ2: We identified six significant contextual moderators of the trust-change relationship, with power distance, historical trust trauma, and stakeholder diversity attenuating the relationship, while change magnitude, digital transformation context, and collectivist culture strengthened it. These findings help explain when and where trust most effectively accelerates change.

RQ3: The six evidence-based strategies identified—transparent sensemaking, demonstrated skin in the game, consistent procedural justice, rapid trust repair, multi-level engagement, and psychological safety cultivation—provide practitioners with practical approaches to leveraging trust during change.

RQ4: Our multi-level analysis revealed significant trust asymmetries across organizational hierarchies, with trust typically decreasing at lower organizational levels. These asymmetries can create implementation challenges, but our findings on “trust bridges” suggest ways to mitigate these effects.

RQ5: We documented potential downsides of excessive trust during change and proposed the concept of “vigilant trust” as a balanced approach that captures trust benefits while mitigating risks through calibrated vulnerability, constructive skepticism, independent verification, and balanced accountability.

The evidence consistently supports viewing trust not merely as a cultural aspiration but as a strategic asset with quantifiable value in change contexts. Organizations and leaders who deliberately build and manage trust create conditions where change can proceed with unusual efficiency and effectiveness.

Importantly, the findings highlight that this relationship is neither simple nor universal. Trust operates differently across organizational levels, varies in its effects based on contextual factors, and requires tailored development approaches in different environments. Additionally, trust is not an unmitigated good—excessive or uncritical trust can create its own problems in change contexts. The concept of “vigilant trust” offers a balanced approach that captures trust benefits while mitigating potential downsides.

The research also reveals the importance of addressing trust asymmetries across organizational levels, the distinctive dynamics of trust in digital transformation contexts, and the special challenges of building trust in environments with historical trauma. These nuanced findings extend our understanding of trust beyond simplistic approaches and provide a more sophisticated framework for leveraging trust during change.

The data are clear: organizations with strong trust foundations demonstrate superior change implementation capabilities, including faster timelines, higher adoption rates, and more sustainable outcomes. In a world where the pace of required change continues to accelerate, organizations that invest in trust-building may gain a decisive competitive advantage—the ability to transform more rapidly, more thoroughly, and with less collateral damage than their low-trust counterparts.

The wormhole of trust doesn’t defy the laws of organizational physics—it works with them, creating conditions where change encounters minimal resistance and maximum momentum. For organizations committed to meaningful transformation, there may be no more valuable focus than the deliberate cultivation of this powerful catalyst.

Appendix A. Trust and Change Acceleration Survey Instrument

Trust and Change Acceleration Survey Instrument

Introduction to Survey Participants

Thank you for participating in this research study on trust and organizational change. This survey examines how trust influences the implementation of change initiatives in organizations. Your responses will help us better understand the relationship between trust and change success.

Your participation is voluntary, and your responses will be kept confidential. Only aggregated data will be reported in research findings. The survey should take approximately 20-25 minutes to complete.

Section 1: Demographics and Organizational Context

-

Your position in the organization:

Senior leadership (C-suite, VP, Director)

Middle management

First-line supervisor

Non-supervisory employee

Other (please specify): ________

-

Length of time with your current organization:

Less than 1 year

1-3 years

4-7 years

8-15 years

More than 15 years

-

Your functional area:

-

Industry sector of your organization:

-

Size of your organization (number of employees):

Small (1-99 employees)

Medium (100-999 employees)

Large (1,000-9,999 employees)

Very large (10,000+ employees)

-

Primary type of change your organization is currently implementing or has recently implemented:

Technological (new systems, digital transformation)

Structural (reorganization, merger/acquisition)

Strategic (new business direction, market entry)

Cultural (values, norms, work practices)

Process (workflow, efficiency improvements)

Other (please specify): ________

-

Current stage of the change initiative:

Section 2: Trust Dimensions

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements using the scale:

1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neither Agree nor Disagree, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly Agree

Leadership Ability Trust

- 8.

Leaders in my organization have the skills needed to implement this change successfully.

- 9.

Leaders in my organization have demonstrated competence in managing previous changes.

- 10.

I believe the leadership team understands what is required to make this change work.

- 11.

Leaders in my organization have the technical knowledge relevant to this change.

- 12.

I trust leaders’ judgment regarding the best way to implement this change.

Leadership Benevolence Trust

- 13.

Leaders in my organization genuinely care about employees’ wellbeing during this change.

- 14.

I believe leaders consider how this change affects different stakeholder groups.

- 15.

Leaders would not knowingly do anything to harm employees through this change.

- 16.

Leaders take employee concerns about the change seriously.

- 17.

I believe leaders have employees’ best interests in mind when making change-related decisions.

Leadership Integrity Trust

- 18.

Leaders in my organization have been honest about the reasons for this change.

- 19.

Leaders follow through on the commitments they make regarding this change.

- 20.

Leaders’ actions during this change are consistent with their stated values.

- 21.

Leaders communicate transparently about both positive and negative aspects of this change.

- 22.

I believe leaders will keep their promises related to this change.

Leadership Consistency Trust

- 23.

Leaders in my organization are predictable in how they implement changes.

- 24.

Leaders’ messages about this change have been consistent over time.

- 25.

Different leaders in the organization present a unified message about this change.

- 26.

Leaders reliably follow established processes during change implementation.

- 27.

I can anticipate how leaders will respond to challenges in the change process.

Organizational Trust

- 28.

This organization has a good track record of implementing changes successfully.

- 29.

I trust that established organizational systems will support this change appropriately.

- 30.

This organization’s policies and procedures are reliable even during periods of change.

- 31.

The organization provides adequate resources to implement changes effectively.

- 32.

I believe this organization makes changes with legitimate business purposes in mind.

Team Trust

- 33.

Members of my immediate team trust each other during this change process.

- 34.

I can rely on my colleagues to fulfill their responsibilities related to this change.

- 35.

People in my team are honest with each other about change-related challenges.

- 36.

My team members share information openly about how the change affects our work.

- 37.

I feel comfortable discussing concerns about the change with my team members.

Please rate the following aspects of your organization’s current or recent change initiative:

Implementation Timeline Adherence

- 38.

The change initiative is progressing according to its planned timeline.(1 = Significantly behind schedule, 3 = On schedule, 5 = Ahead of schedule)

- 39.

Compared to similar changes in your organization or industry, this change is being implemented:(1 = Much slower, 3 = At typical pace, 5 = Much faster)

- 40.

Key change milestones are being met:(1 = Never, 2 = Rarely, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = Usually, 5 = Always)

- 41.

Delays in the change implementation are:(1 = Extensive and frequent, 3 = Moderate and occasional, 5 = Minimal to none)

Adoption Rate

- 42.

The percentage of affected employees actively using new systems, processes, or practices is:(1 = Very low (<20%), 2 = Low (21-40%), 3 = Moderate (41-60%), 4 = High (61-80%), 5 = Very high (>80%))

- 43.

The rate at which employees are adopting the change is:(1 = Much slower than expected, 3 = As expected, 5 = Much faster than expected)

- 44.

Compliance with new requirements or processes related to the change is:(1 = Very low, 2 = Low, 3 = Moderate, 4 = High, 5 = Very high)

- 45.

Stakeholder engagement with the change initiative is:(1 = Very low, 2 = Low, 3 = Moderate, 4 = High, 5 = Very high)

Decision Speed

- 46.

Decisions related to the change are made:(1 = Very slowly with many delays, 3 = At a moderate pace, 5 = Very quickly and efficiently)

- 47.

The time required to get approvals for change-related decisions is:(1 = Excessive, 3 = Reasonable, 5 = Minimal)

- 48.

When implementation issues arise, the time to resolve them is:(1 = Very long, 3 = Moderate, 5 = Very short)

- 49.

The number of decision-making layers involved in the change process is:(1 = Excessive, 3 = Appropriate, 5 = Streamlined)

Section 4:Mediating Mechanisms

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements using the scale:1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neither Agree nor Disagree, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly Agree

Resistance to Change

- 50.

Employees in my organization actively resist this change initiative.

- 51.

People frequently express skepticism about the value of this change.

- 52.

There is significant pushback against new processes or systems.

- 53.

Employees try to maintain old ways of working despite the change.

- 54.

There is a general reluctance to engage with this change initiative.

Information Flow

- 55.

Information about the change flows freely throughout the organization.

- 56.

People share relevant information about the change across departments.

- 57.

Communication channels are effective for distributing change-related updates.

- 58.

Employees receive timely information about change progress and challenges.

- 59.

There is open dialogue about the change across different organizational levels.

Psychological Safety

- 60.

Employees feel safe to experiment with new approaches during this change.

- 61.

People can express concerns about the change without fear of negative consequences.

- 62.

Making mistakes during the change implementation is treated as a learning opportunity.

- 63.

Different viewpoints about the change are welcomed and considered.

- 64.

Employees feel comfortable asking questions about the change.

Decision Efficiency

- 65.

Change-related decisions are made efficiently without unnecessary delays.

- 66.

Authority to make decisions about the change is appropriately delegated.

- 67.

Decision-making processes for this change are clear and well-understood.

- 68.

Approvals for change-related actions are obtained in a timely manner.

- 69.

The organization avoids excessive committees or approval layers for change decisions.

Risk Tolerance

- 70.

The organization is willing to accept some uncertainty during this change.

- 71.

Employees feel comfortable proceeding with incomplete information when necessary.

- 72.

The organization accepts that some aspects of the change may not work perfectly the first time.

- 73.

There is tolerance for calculated risks in implementing this change.

- 74.

People are willing to try new approaches even when success is not guaranteed.

Section 5: Contextual Factors

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements using the scale:1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neither Agree nor Disagree, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly Agree

Power Distance

- 75.

Important decisions in this organization are made by senior leaders with limited input from others.

- 76.

Employees are expected to follow leaders’ directions without questioning them.

- 77.

There is a clear hierarchy that influences how the change is implemented.

- 78.

Power is concentrated among a small group of individuals in this organization.

- 79.

Lower-level employees have limited influence over how changes are implemented.

Historical Trust Trauma

- 80.

This organization has a history of broken promises during previous changes.

- 81.

Past change initiatives have negatively affected employee trust.

- 82.

Leaders have previously failed to follow through on commitments during changes.

- 83.

There are lingering negative feelings about how past changes were handled.

- 84.

The organization has a history of surprising employees with unexpected changes.

Change Magnitude

- 85.

This change represents a significant departure from previous ways of working.

- 86.

The change affects a large percentage of employees in the organization.

- 87.

This change initiative has far-reaching implications for the organization.

- 88.

The change requires substantial adjustment to core processes or systems.

- 89.

This is a transformative rather than incremental change for our organization.

Stakeholder Diversity

- 90.

This change affects diverse groups with different interests and concerns.

- 91.

Stakeholders affected by this change have varying levels of influence in the organization.

- 92.

There is significant demographic diversity among those affected by the change.

- 93.

The change impacts people with widely differing job functions or specialties.

- 94.

Stakeholders have varying levels of understanding about this change.

Digital vs. Non-Digital Change

- 95.

This change primarily involves implementing new digital technologies.

- 96.

The change requires significant adaptation to digital systems or processes.

- 97.

Digital literacy is an important factor in implementing this change.

- 98.

This change is part of a broader digital transformation initiative.

- 99.

Technology plays a central role in this change initiative.

Cultural Context (Collectivist vs. Individualist)

- 100.

In our organization, group goals take priority over individual goals.

- 101.

Collaborative decision-making is valued more than individual autonomy.

- 102.

People identify strongly with their teams or the organization as a whole.

- 103.

Maintaining harmony in working relationships is highly valued.

- 104.

Individual achievements are less emphasized than collective accomplishments.

Section 6: Open-Ended Questions

- 105.

In what ways has trust (or lack of trust) affected the implementation of change in your organization?

- 106.

What specific actions by leaders have most significantly built or damaged trust during this change?

- 107.

If you could advise other organizations on building trust during change, what would you recommend?

- 108.

What barriers or challenges have most affected the speed of change implementation in your organization?

- 109.

Is there anything else you would like to share about trust and change in your organization?

Conclusion

Thank you for completing this survey. Your responses will contribute to our understanding of how trust influences organizational change processes. If you have any questions about this research or would like to receive a summary of findings when available, please contact the research team at [email address].

Appendix B: Interview and Focus Group Protocols

Semi-Structured Interview Protocol: Trust and Organizational Change

Introduction (5 minutes)

Introduce self and research purpose

Review informed consent, recording procedures, and confidentiality measures

Explain how the interview data will be used

Confirm interview duration (approximately 60 minutes)

Ask if participant has any questions before beginning

Participant Background (5-7 minutes)