Submitted:

24 June 2025

Posted:

25 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Statistics in Medical Research

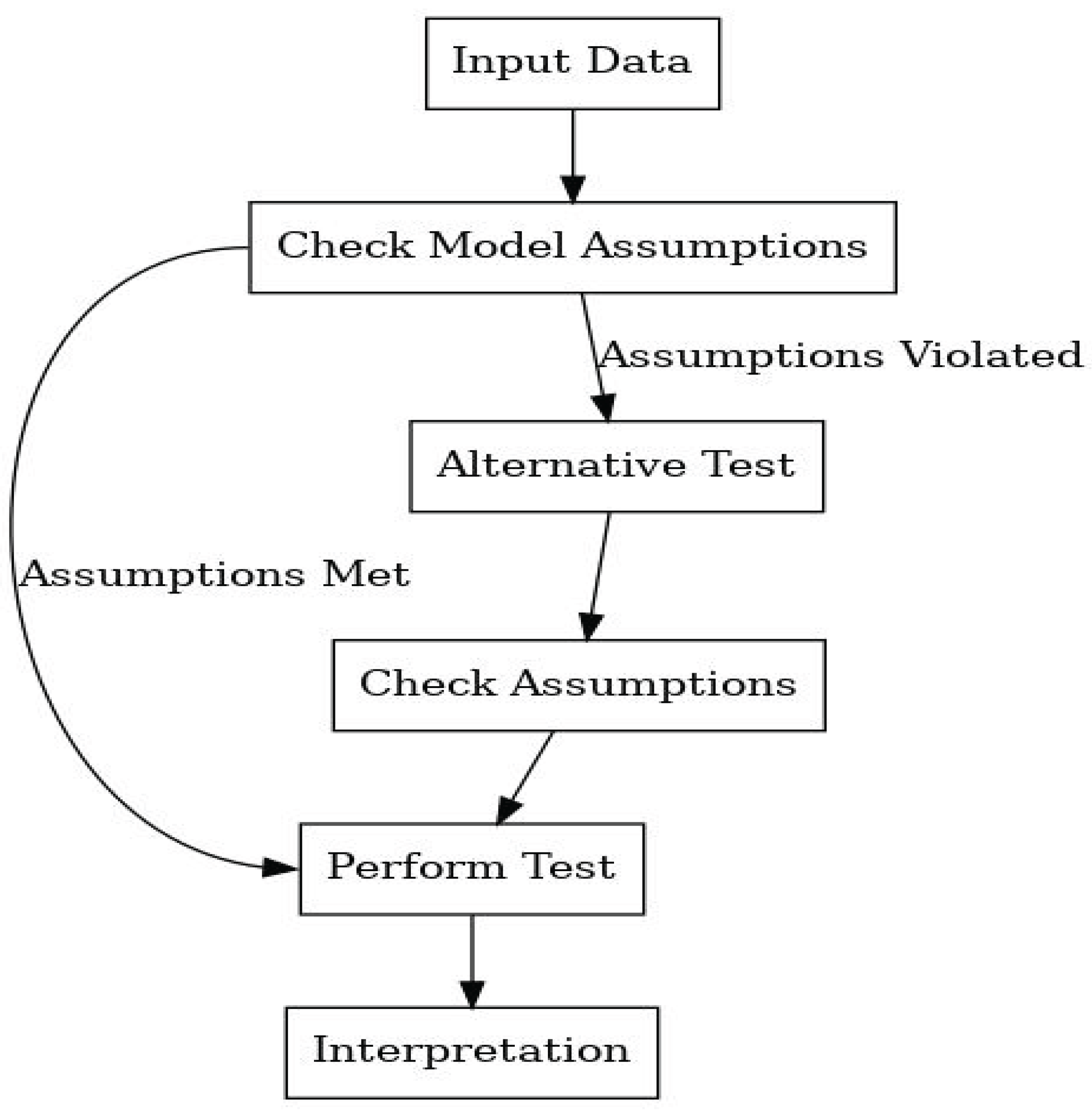

2.1. Statistical Tests and Assumptions

2.2. T-Tests and Their Assumptions

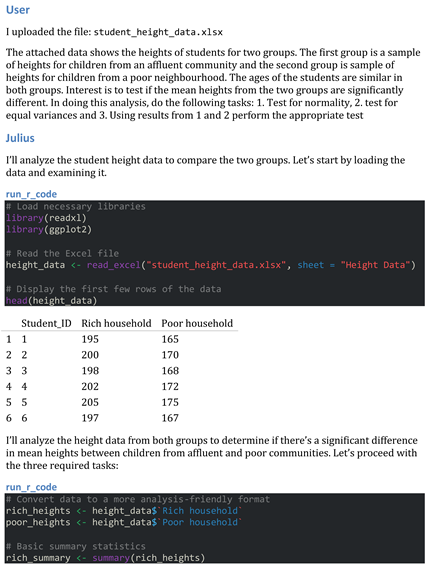

3. Illustration

3.1. Data

| Student_ID | Rich household | Poor household |

| 1 | 195.00 | 165.00 |

| 2 | 200.00 | 170.00 |

| 3 | 198.00 | 168.00 |

| 4 | 202.00 | 172.00 |

| 5 | 205.00 | 175.00 |

| 6 | 197.00 | 167.00 |

| 7 | 203.00 | 173.00 |

| 8 | 201.00 | 171.00 |

| 9 | 199.00 | 169.00 |

| 10 | 204.00 | 174.00 |

4. Conclusion

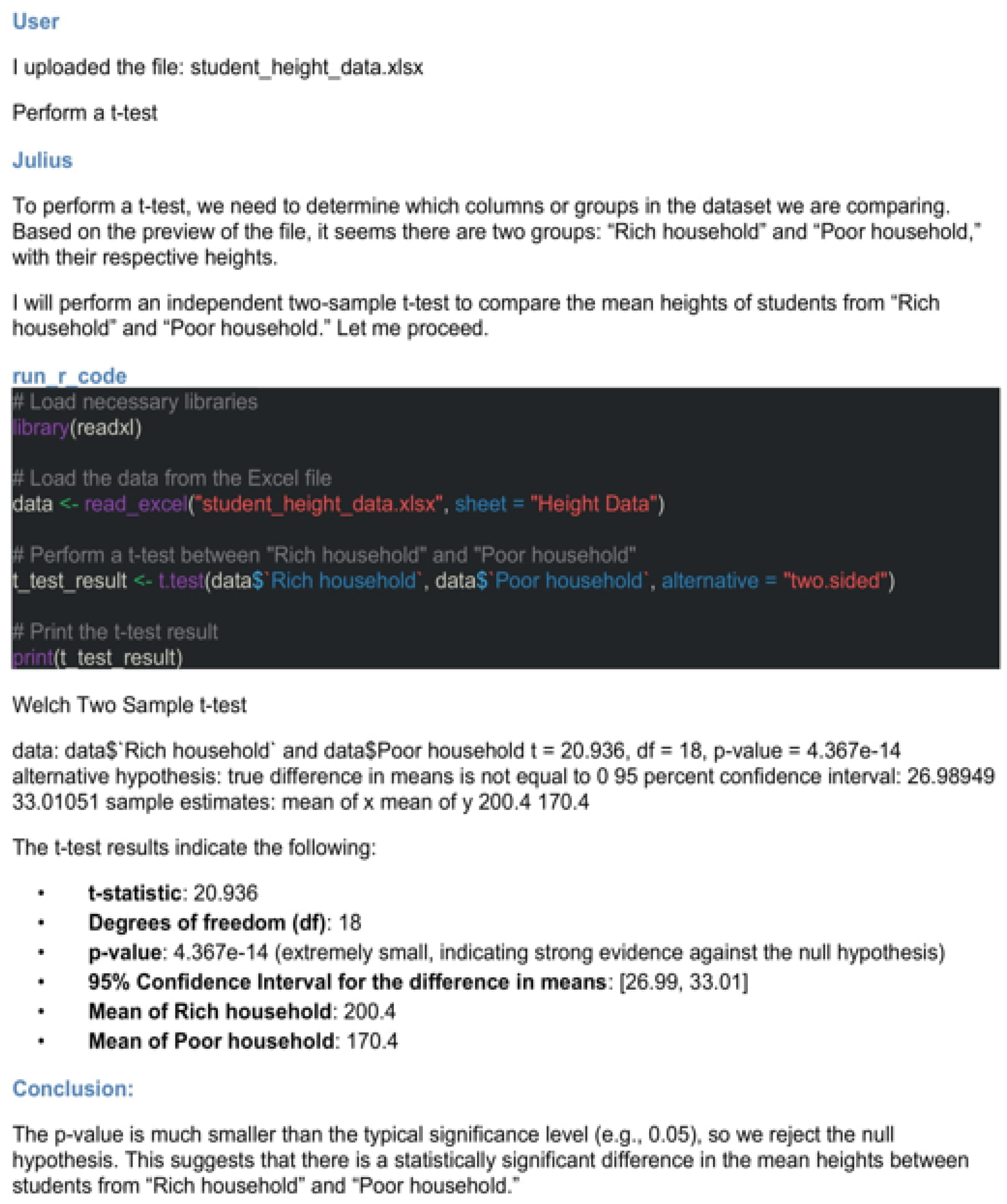

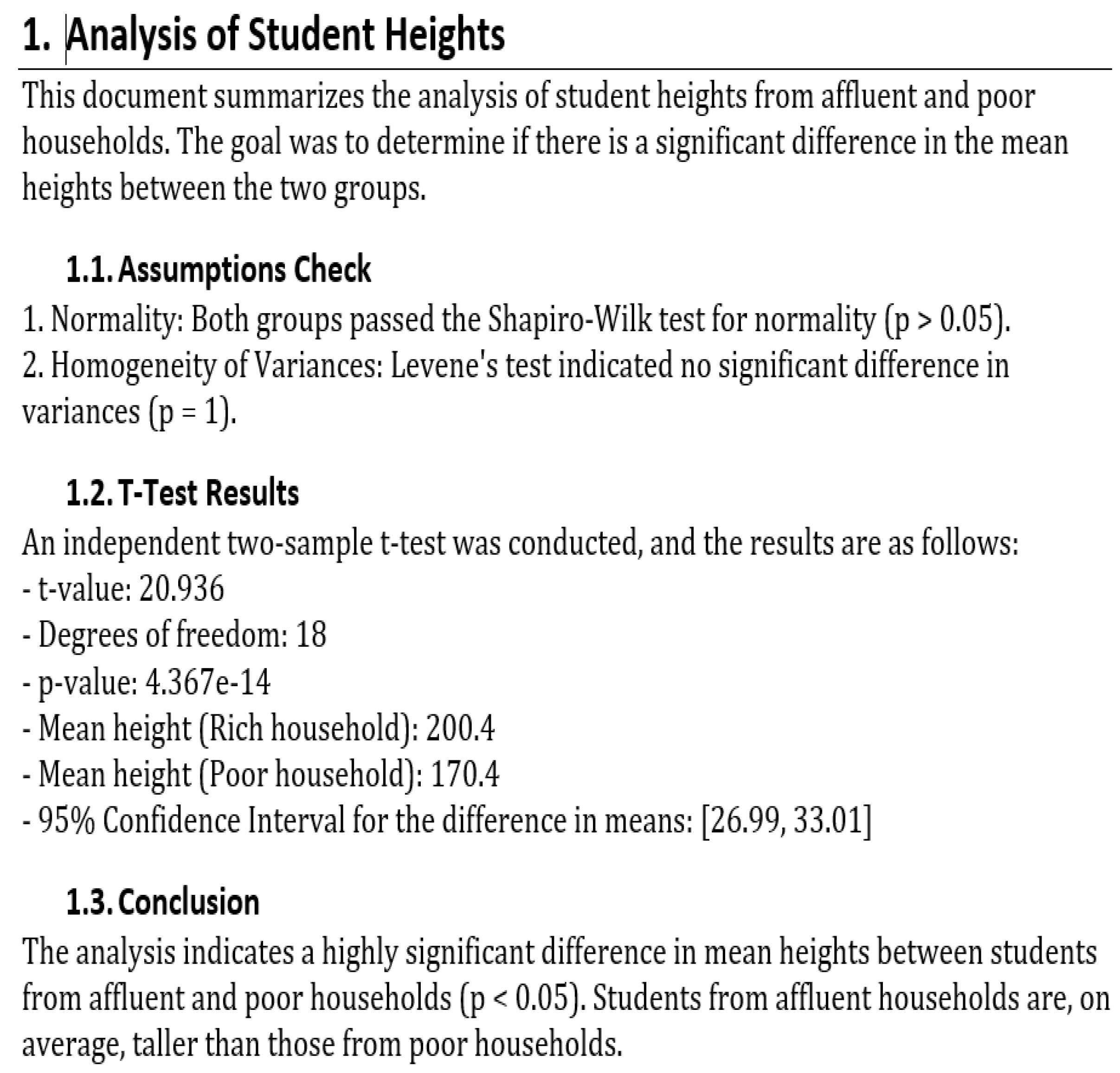

Appendix E Julius AI Claude 3.7 Sonnet Output Using Approach 3

References

- AI, O. Introducing ChatGPT. https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt/, 2022. Accessed: April 02, 2025.

- Frey, C.B.; Osborne, M.A. The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Technological forecasting and social change 2017, 114, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insights, G.M. Generative AI in Healthcare Market – By Application, By End Use - Global Forecast, 2024 to 2032. https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt/, 2022. Accessed: April 02, 2025. 02 April.

- Ackerman, P.E.; Andrews, E.; Carter, C.M.; DeMaio, C.D.; Knaple, B.S.; Larson, H.; Lonstein, W.; McCreight, R.; Muehlfelder, T.; Mumm, H.C.; et al. Intersection of Biotechnology and AI (Sincavage & Muehlfelder & Carter). Advanced Technologies for Humanity 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Njei, B.; Kanmounye, U.S.; Mohamed, M.F.; Forjindam, A.; Ndemazie, N.B.; Adenusi, A.; Egboh, S.M.C.; Chukwudike, E.S.; Monteiro, J.F.G.; Berzin, T.M.; et al. Artificial intelligence for healthcare in Africa: a scientometric analysis. Health and Technology 2023, 13, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, T.; Olsen, E.; Vinod, A.; Glenn, N.; Hanna, K.; Lund, G.C.; Pierce-Talsma, S.; et al. Generative Artificial Intelligence in Medical Education—Policies and Training at US Osteopathic Medical Schools: Descriptive Cross-Sectional Survey. JMIR Medical Education 2025, 11, e58766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehrman, E. How Generative AI Is Transforming Medical Education. https://https://magazine.hms.harvard.edu/articles/how-generative-ai-transforming-medical-education, 2024. Accessed: April 02, 2025.

- Andigema, A.; Cyrielle, N.N.T.; Danaëlle, M.K.L.; Ekwelle, E. Transforming african healthcare with AI: paving the way for improved health outcomes. Journal of Translational Medicine & Epidemiology 2024, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cribben, I.; Zeinali, Y. The benefits and limitations of ChatGPT in business education and research: A focus on management science, operations management and data analytics. Operations Management and Data Analytics (March 29, 2023) 2023.

- Zhai, C.; Wibowo, S.; Li, L.D. The effects of over-reliance on AI dialogue systems on students’ cognitive abilities: a systematic review. Smart Learning Environments 2024, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wu, R.; He, J.; Xiang, Y. Evaluating ChatGPT-4.0’s data analytic proficiency in epidemiological studies: A comparative analysis with SAS, SPSS, and R. Journal of Global Health 2024, 14, 04070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sackett, D.L. Evidence-based medicine. In Proceedings of the Seminars in perinatology. Elsevier, 1997, Vol. 21, pp. 3–5.

- Thiese, M.S.; Arnold, Z.C.; Walker, S.D. The misuse and abuse of statistics in biomedical research. Biochemia medica 2015, 25, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, P.S. Introductory statistics; John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

- Nørskov, A.K.; Lange, T.; Nielsen, E.E.; Gluud, C.; Winkel, P.; Beyersmann, J.; de Uña-Álvarez, J.; Torri, V.; Billot, L.; Putter, H.; et al. Assessment of assumptions of statistical analysis methods in randomised clinical trials: the what and how. BMJ evidence-based medicine 2021, 26, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanji, G.K. 100 statistical tests; Sage, 1999.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).