Submitted:

23 June 2025

Posted:

24 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

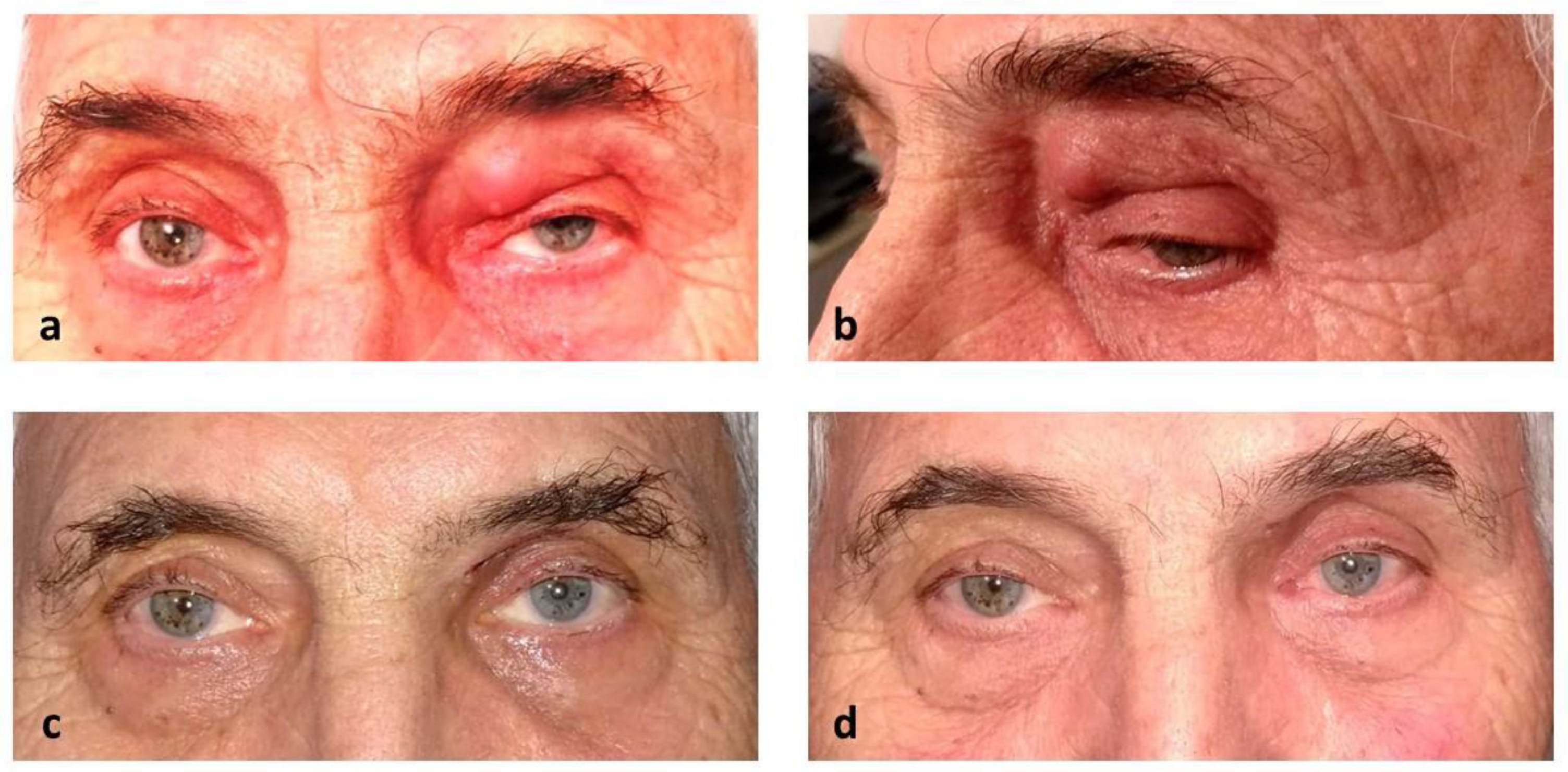

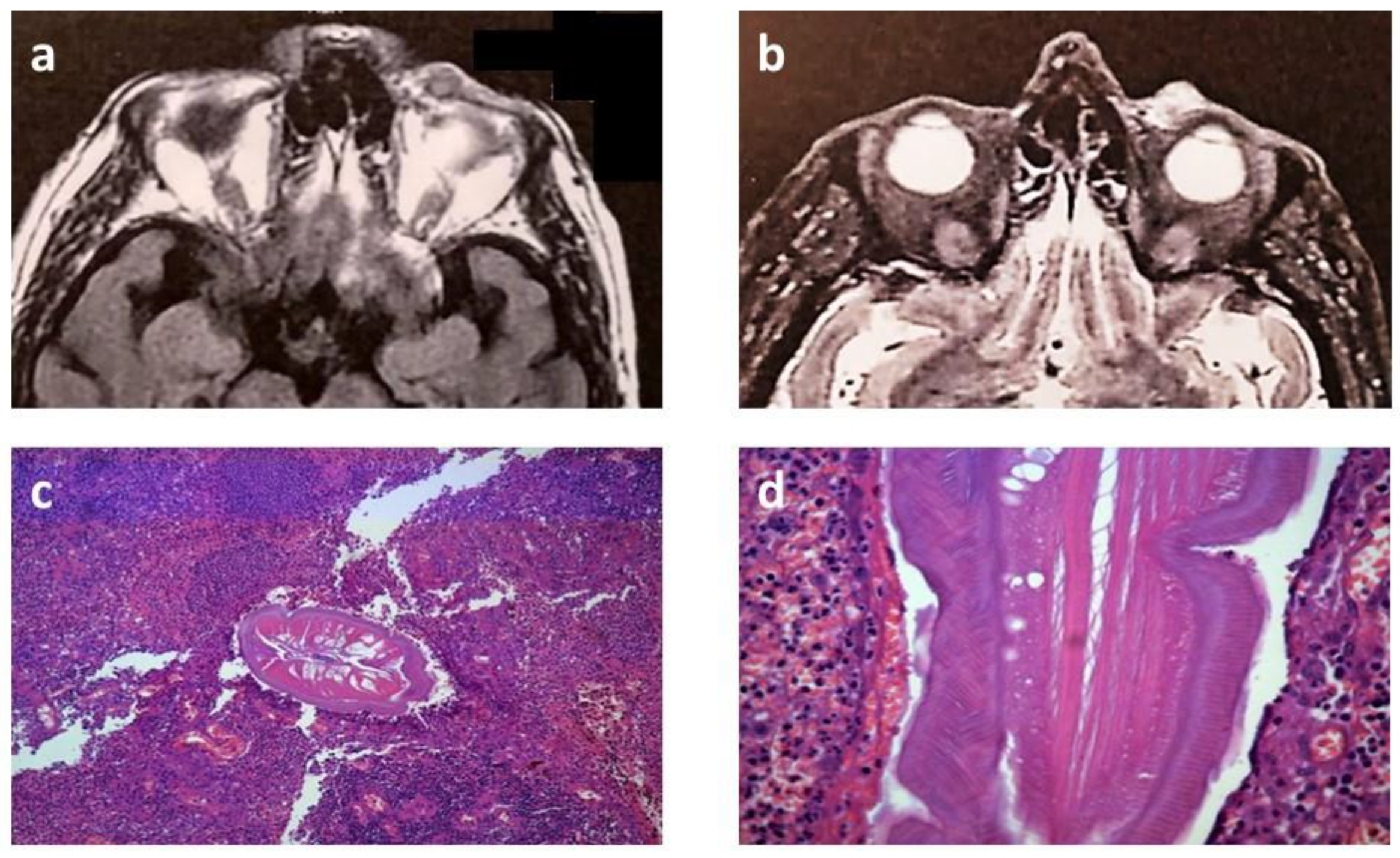

1.1. Case Report

2. Discussion

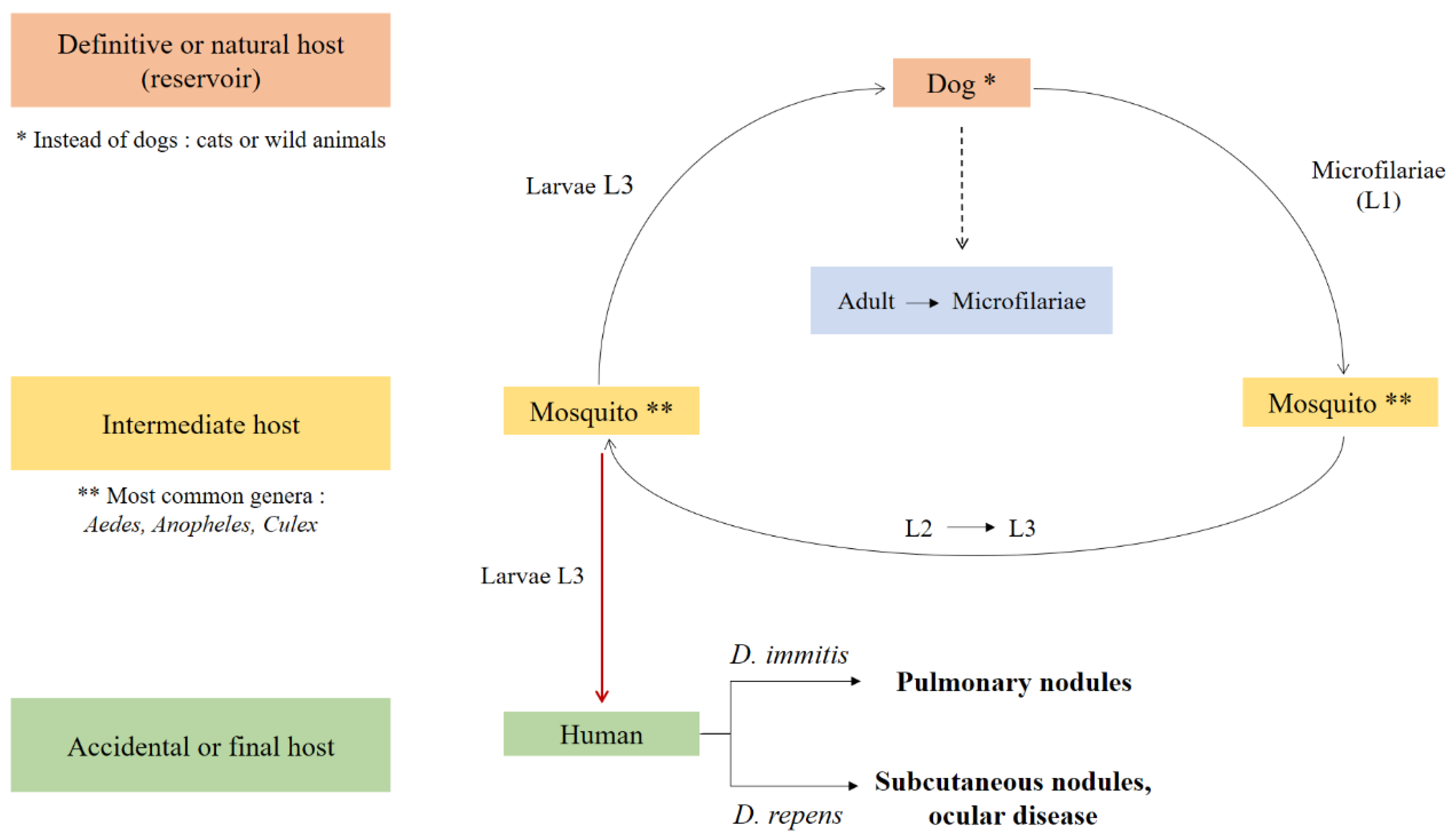

2.1. Synopsis of Dilofiraria’s Life Cycle

2.2. Ocular dirofilariasis and Involved Tissues

2.3. Eyelid Dirofilariasis

2.3.1. Literature Review - Methodology

2.3.2. Literature review - Results

| Total cases, N | 117 | |

|

Patient age Median Mean (±standard deviation) Range |

39 years 40.1 (±18) years 11 months - 77 years |

|

|

Patient sex, n (%) Female Male Not reported |

69 41 7 |

(59) (35) (6) |

|

Lesion localization, n (%)

Upper eyelid Lower eyelid Lateral canthus Medial canthus Not reported |

64 35 1 1 16 |

(54.7) (29.9) (0.85) (0.85) (13.7) |

|

Geographic region†, n (%) Eastern Europe Southern Europe Western Europe Central Asia Eastern Asia Western Asia South-eastern Asia Southern Asia Northern America Northern Africa Not reported |

34 19 11 2 2 5 4 31 6 2 1 |

(29.1) (16.2) (9.4) (1.7) (1.7) (4.3) (3.4) (26.5) (5.1) (1.7) (0.9) |

| Reported travel history to an endemic region, n (%) | 10 | (8.5) |

|

Nematode sex, n (%) Female Male Not reported |

31 7 79 |

(26.5) (6) (67.5) |

|

Nematode species, n (%) D. repens D. immitis D. tenuis D. hongkongensis Not reported |

103 2 4 1 7 |

(88) (1.7) (3.4) (0.9) (6) |

| Molecular confirmation of the diagnosis, n (%) | 20 | (17.1) |

2.3.3. Clinical Appearance

2.3.4. Laboratory Investigation

2.3.5. Imaging Findings

2.3.6. Management

3. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diaz, JH. Increasing risks of human dirofilariasis in travelers. J Travel Med. 2015;22(2):116–23.

- Simón F, Siles-Lucas M, Morchón R, González-Miguel J, Mellado I, Carretón E, et al. Human and animal dirofilariasis: the emergence of a zoonotic mosaic. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012 Jul;25(3):507–44.

- Genchi C, Rinaldi L, Mortarino M, Genchi M, Cringoli G. Climate and Dirofilaria infection in Europe. Vet Parasitol. 2009 Aug 26;163(4):286–92.

- Capelli G, Genchi C, Baneth G, Bourdeau P, Brianti E, Cardoso L, et al. Recent advances on Dirofilaria repens in dogs and humans in Europe. Parasit Vectors. 2018 Dec 19;11(1):663.

- Aspock H. Dirofilaria and dirofilarioses; Introductory remarks. In: Proceedings of Helminthological Colloquium, Vienna. 2003. p. 5.

- Genchi C, Kramer LH, Rivasi F. Dirofilarial infections in Europe. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011 Oct;11(10):1307–17.

- Pampiglione S, Canestri Trotti G, Rivasi F. Human dirofilariasis due to Dirofilaria (Nochtiella) repens: a review of world literature. Parassitologia. 1995 Dec;37(2–3):149–93.

- Sergiev VP, Supriaga VG, Morozov EN, Zhukova LA. [Human dirofilariasis: diagnosis and the pattern of pathogen-host relations]. Med Parazitol (Mosk). 2009;(3):3–6.

- McCall JW, Genchi C, Kramer LH, Guerrero J, Venco L. Heartworm disease in animals and humans. Adv Parasitol. 2008;66:193–285.

- Kagei N, Tanaka K, Okamura R, Korenaga M, Tada I. A report of the first case of Dirofilaria infection in the eyelid region in Japan. Jpn J Med Sci Biol. 1985;38(5–6):223–7.

- Pampiglione S, Rivasi F. Human dirofilariasis due to Dirofilaria (Nochtiella) repens: an update of world literature from 1995 to 2000. Parassitologia. 2000 Dec;42(3–4):231–54.

- Harizanov RN, Jordanova DP, Bikov IS. Some aspects of the epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of human dirofilariasis caused by Dirofilaria repens. Parasitol Res. 2014 Apr;113(4):1571–9.

- Sathyan P, Manikandan P, Bhaskar M, Padma S, Singh G, Appalaraju B. Subtenons infection by Dirofilaria repens. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2006 Jan;24(1):61–2.

- Kalogeropoulos CD, Stefaniotou MI, Gorgoli KE, Papadopoulou CV, Pappa CN, Paschidis CA. Ocular Dirofilariasis: A Case Series of 8 Patients. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2014;21(4):312–6.

- Bhat S, Saldanha M, Mendonca N. Periocular dirofilariasis: A case series. Orbit. 2016;35(2):100–2.

- Eligi C, Scasso CA, Eligi B, Busoni F. [Retrobulbar orbital dirofilariasis. A case report]. Radiol Med. 1995 Sep;90(3):334–5.

- Sethi A, Puri V, Dogra N. An unusual presentation of lacrimal gland dirofilariasis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2017 Jul;65(7):615–7.

- Gupta P, Pradeep S, Biswas J, Rishi P, Muthusamy R. Extensive Chorio-retinal Damage Due to Dirofilaria Repens- Report of a Case. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021 Aug 18;29(6):1142–4.

- Font RL, Neafie RC, Perry HD. Subcutaneous dirofilariasis of the eyelid and ocular adnexa. Report of six cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980 Jun;98(6):1079–82.

- Delage A, Lauraire MC, Eglin G. [Is human Dirofilaria (Nochtiella) repens parasitosis mor frequent than it appears on the Mediterranean coast?]. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1995;88(3):90–4.

- Spina F, Saraniti G, Randazzo S, Dal Bello A, Vallone G, Gorgone G. [2 cases of ocular filariasis]. Bull Mem Soc Fr Ophtalmol. 1986;97:57–61.

- Pampiglione S, Brollo A, Ciancia EM, De Benedittis A, Feyles E, Mastinu A, et al. [Human subcutaneous dirofilariasis: 8 more cases in Italy]. Pathologica. 1996 Apr;88(2):91–6.

- Cancrini G, Favia G, Giannetto S, Merulla R, Russo R, Ubaldino V, et al. Nine more cases of human infections by Dirofilaria repens diagnosed in Italy by morphology and recombinant DNA technology. Parassitologia. 1998 Dec;40(4):461–6.

- Kondrazkyi V, Parkhomienco L. Palpebral dirofilariasis. Vestn Ophthalmol. 1977;93(3):78–9.

- Avdiukhina TI, Supriaga VG, Postnova VF, Kuimova RT, Mironova NI, Murashov NE, et al. [Dirofilariasis in the countries of the CIS: an analysis of the cases over the years 1915-1996]. Med Parazitol (Mosk). 1997;(4):3–7.

- Koroev, AI. [Filaria under the skin of the eyelid]. Vestn Oftalmol. 1954;33(1):43.

- Merkusceva I, Cemerizkaia M, Iliuscenko A, Elin I, Malash S. Merkusceva IV, Cemerizkaia MV, Iliuscenko AA, Elin IS, Malash SL, 1981. Dirofilaria repens, nematode, in human eye. Sdravookhran Bjelorussyi 1: 67-68 (in Russian). Sdravookhran Bjelorussyi. 1981;1:67–8.

- Avdiukhina TI, Lysenko AI, Supriaga VG, Postnova VF. [Dirofilariasis of the vision organ: registry and analysis of 50 cases in the Russian Federation and in countries of the United Independent States]. Vestn Oftalmol. 1996;112(3):35–9.

- Postnova VF, Kovtunov A, Abrosimova L, Avdiukhina T, Mishina L, Posorelciuk TIa OV, et al. Dirofilariasis in man new cases. Medsk Parazitol. 1997;1:6–9.

- Dissanaike AS, Abeyewickreme W, Wijesundera MD, Weerasooriya MV, Ismail MM. Human dirofilariasis caused by Dirofilaria (Nochtiella) repens in Sri Lanka. Parassitologia. 1997 Dec;39(4):375–82.

- Pampiglione S, Rivasi F, Angeli G, Boldorini R, Incensati RM, Pastormerlo M, et al. Dirofilariasis due to Dirofilaria repens in Italy, an emergent zoonosis: report of 60 new cases. Histopathology. 2001 Apr;38(4):344–54.

- Raju K, Anju A, Vijayalakshmi M. Subcutaneous Dirofilaria Repens Infection of the Eyelid - A Report of Two Cases. Kerala Journal of Ophthalmology. 2008;XX(3):294–6.

- Szénási Z, Kovács AH, Pampiglione S, Fioravanti ML, Kucsera I, Tánczos B, et al. Human dirofilariosis in Hungary: an emerging zoonosis in central Europe. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2008;120(3–4):96–102.

- Salomváry B, Korányi K, Kucsera I, Szénási Z, Czirják S. A new case of ocular dirofilariosis in Hungary. Szemészet. 2005;142:231–5.

- Parlagi G, Sumi Á, Elek G, Varga I. Orbital dirofilariosis.(Szemüregi dirofilariosis). Szemészet. 2000;137:105–7.

- Elek G, Minik K, Pajor L, Parlagi G, Varga I, Vetési F, et al. New human Dirofilarioses in Hungary. Pathol Oncol Res. 2000;6(2):141–5.

- Fodor E, Fok E, Maka E, Lukáts O, Tóth J. Recently recognized cases of ophthalmofilariasis in Hungary. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2009;19(4):675–8.

- Nath R, Gogoi R, Bordoloi N, Gogoi T. Ocular dirofilariasis. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53(1):157–9.

- Iddawela D, Ehambaram K, Wickramasinghe S. Human ocular dirofilariasis due to Dirofilaria repens in Sri Lanka. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2015 Dec;8(12):1022–6.

- Miterpáková M, Antolová D, Ondriska F, Gál V. Human Dirofilaria repens infections diagnosed in Slovakia in the last 10 years (2007-2017). Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2017 Sep;129(17–18):634–41.

- Hrčkova G, Kuchtová H, Miterpáková M, Ondriska F, Cibíček J, Kovacs S. Histological and molecular confirmation of the fourth human case caused by Dirofilaria repens in a new endemic region of Slovakia. J Helminthol. 2013 Mar;87(1):85–90.

- Velev V, Vutova K, Pelov T, Tsachev I. Human Dirofilariasis in Bulgaria Between 2009 and 2018. Helminthologia. 2019 Sep;56(3):247–51.

- Velev, V. Several Cases of Ocular Dirofilariasis in Bulgaria. Med Princ Pract. 2020 Dec;29(6):588–90.

- Riebenbauer K, Weber PB, Walochnik J, Karlhofer F, Winkler S, Dorfer S, et al. Human dirofilariosis in Austria: the past, the present, the future. Parasit Vectors. 2021 Apr 29;14(1):227.

- Lammerhuber C, Auer H, Bartl G, Dressler H. Subkutane Dirofilaria (Nochtiella) repens-Infektion im Oberlidbereich. Spektrum der Augenheilkunde. 1990;4(4):162–4.

- Faust EC, Agosín M, Garcia-laverde A, Sayad WY, Johnson VM, Murray NA. Unusual Findings of Filarial Infections in Man. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1952;1(2):239–49.

- Zhaboedov GD, Shupik AL. [Case of dirofilariasis of the eye in the Poltava district]. Oftalmol Zh. 1976;31(6):467–8.

- Blodi FC, Saparoff GR. [A dirofilaria granulom of the lid and the orbid (author’s transl)]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 1977 Aug;171(2):222–4.

- Jariya P, Sucharit S. Dirofilaria repens from the eyelid of a woman in Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1983 Nov;32(6):1456–7.

- Mak JW, Thanalingam V. Human infection with Dirofilaria (Nochtiella) sp.(Nematoda: Filarioidea), probably D. repens, in Malaysia. Tropical Biomedicine. 1984;1(2):109–13.

- Baumann, J. [Worm infection (Dirofilaria conjunctivae) in the ENT area]. Laryngol Rhinol Otol (Stuttg). 1987 Sep;66(9):480–3.

- Pampiglione S, Canestri-Trotti G, Piro S, Maxia C. [Palpebral dirofilariasis in man: a case in Sardinia]. Pathologica. 1989;81(1071):57–62.

- Pampiglione S, Manilla G, Canestri-Trotti G. [Human dirofilariasis in Italy: a new palpebral case with spontaneous healing in Abruzzo]. Parassitologia. 1990 Dec;32(3):381–4.

- Georgouli M, Loukaki M, Lentari A, Hinou F, Karaiskos H, Golemati P. An unusual case of human dirofilariasis located in the subcutaneous tissue of the lower eyelid. Acta Microbiologica Hellenica. 1991;36:213–20.

- Soylu M, Ozcan K, Yalaz M, Varinli S, Slem G. Dirofilariasis: an uncommon parasitosis of the eye. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993 Sep;77(9):602–3.

- Fuentes I, Cascales A, Ros JM, Sansano C, Gonzalez-Arribas JL, Alvar J. Human subcutaneous dirofilariasis caused by Dirofilaria repens in Ibiza, Spain. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994 Oct;51(4):401–4.

- van den Ende J, Kumar V, van Gompel A, van Den Enden E, Puttemans A, Geerts M, et al. Subcutaneous dirofilariasis caused by Dirofilaria (nochtiella) repens in a Belgian patient. International journal of dermatology. 1995;34(4):274–7.

- Awadalla HN, Bayoumi DM, Ibrahim IR. The first case report of suspected human dirofilariasis in the eyelid of a patient from Alexandria. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1998 Dec;28(3):941–3.

- Sekhar HS, Srinivasa H, Batru RR, Mathai E, Shariff S, Macaden RS. Human ocular dirofilariasis in Kerala Southern India. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2000 Jan;43(1):77–9.

- Striukova IL, Goncharova OV, Gul’iants VA. [Dirofilariasis in the practice of an ophthalmologist]. Vestn Oftalmol. 2001;117(3):43–4.

- Vakalis N, Vougioukas N, Patsoula E, Spanakos G, Sioutopoulou DO, Vamvakopoulos NC. Genotypic assignment of infection by Dirofilaria repens. Parasitol Int. 2002 Jun;51(2):163–9.

- Dzamić AM, Arsić-Arsenijević V, Radonjić I, Mitrović S, Marty P, Kranjcić-Zec IF. Subcutaneous Dirofilaria repens infection of the eyelid in Serbia and Montenegro. Parasite. 2004 Jun;11(2):239–40.

- Ittyerah TP, Mallik D. A case of subcutaneous dirofilariasis of the eyelid in the South Indian state of Kerala. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2004 Sep;52(3):235.

- Aiello A, Aiello P, Aiello F. A case of palpebral dirofilariasis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2005;15(3):407–8.

- Siepmann K, Wannke B, Neumann D, Rohrbach JM. Subcutaneous tumor of the lower eyelid: a potential manifestation of a Dirofilaria repens infection. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2005;15(1):129–31.

- Beden U, Hokelek M, Acici M, Umur S, Gungor I, Sullu Y. A case of orbital dirofilariasis in Northern Turkey. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;23(4):329–31.

- Abdel-Rahman SM, Mahmoud AE, Galal L a. A, Gustinelli A, Pampiglione S. Three new cases of human infection with Dirofilaria repens, one pulmonary and two subcutaneous, in the Egyptian governorate of Assiut. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2008 Sep;102(6):499–507.

- Smitha M, Rajendran V, Devarajan E, Anitha P. Case report: Orbital dirofilariasis. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2008 Feb;18(1):60–2.

- Mannino G, Contestabile MT, Medori EM, Mannino C, Enrici MM, Marangi M, et al. Dirofilaria Repens in the Eyelid: Case Report of Subcutaneous Manifestation. European Journal of Ophthalmology. 2009 May;19(3):475–7.

- Shenoi SD, Kumar P, Johnston SP, Khadilkar UN. Cutaneous dirofilariasis presenting as an eyelid swelling. Trop Doct. 2009 Jul;39(3):189–90.

- Dang TCT, Nguyen TH, Do TD, Uga S, Morishima Y, Sugiyama H, et al. A human case of subcutaneous dirofilariasis caused by Dirofilaria repens in Vietnam: histologic and molecular confirmation. Parasitol Res. 2010 Sep;107(4):1003–7.

- Khurana S, Singh G, Bhatti HS, Malla N. Human subcutaneous dirofilariasis in India: a report of three cases with brief review of literature. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2010;28(4):394–6.

- Kotigadde S, Ramesh SA, Medappa KT. Human dirofilariasis due to Dirofilaria repens in southern India. Trop Parasitol. 2012 Jan;2(1):67–8.

- Sahdev SI, Sureka SP, Sathe PA, Agashe R. Ocular dirofilariasis: still in the dark in western India? J Postgrad Med. 2012;58(3):227–8.

- Gopinath TN, Lakshmi KP, Shaji PC, Rajalakshmi PC. Periorbital dirofilariasis—Clinical and imaging findings: Live worm on ultrasound. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013 Jun;61(6):298–300.

- Senanayake MP, Infaq MLM, Adikaram SGS, Udagama PV. Ocular and subcutaneous dirofilariasis in a Sri Lankan infant: an environmental hazard caused by dogs and mosquitoes. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2013 Dec;33(2):111–2.

- Shankar MK, Shet S, Gupta P, Nadgir SD. Sac over the sac - a rare case of subcutaneous dirofilariasis over the lacrimal sac area. Nepal J Ophthalmol. 2014;6(2):224–6.

- Werner JU, Wacker T, Lang GK. [Subcutaneous dirofilariasis of the eyelid]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2014 Sep;231(9):924–5.

- Choi SH, Kim N, Paik JH, Cho J, Chai JY. Orbital dirofilariasis. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2014 Dec;28(6):495–6.

- Dóczi I, Bereczki L, Gyetvai T, Fejes I, Skribek Á, Szabó Á, et al. Description of five dirofilariasis cases in South Hungary and review epidemiology of this disease for the country. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2015 Sep;127(17–18):696–702.

- Kutlutürk I, Tamer GZS, Karabaş L, Erbesler AN, Yazar S. A rapidly emerging ocular zoonosis; Dirofilaria repens. Eye (Lond). 2016 Apr;30(4):639–41.

- Smets M, De Potter P. First cases of ocular dirofilariasis caused by drofilaria repens in Belgium. Acta Ophthalmologica [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2024 Apr 29];94(S256). Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1755-3768.2016.0572.

- Jessani LG, Patil S, Annapurneshwari D, Durairajan S, Gopalakrishnan R. Human ocular dirofilariasis due to Dirofilaria repens: an underdiagnosed entity or emerging filarial disease? International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2016;45:177.

- Nagpal S, Kulkarni V. Periorbital Dirofilariasis: A Rare Case from Western India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016 Mar;10(3):OD12-14.

- Gushсhina MB, Egorova EV, Yuzhakova NS, Mal’kov SA. [Orbital case of ocular dirofilariasis]. Vestn Oftalmol. 2017;133(2):82–5.

- Rodríguez-Calzadilla M, Ruíz-Benítez MW, de-Francisco-Ramírez JL, Redondo-Campos AR, Fernández-Repeto-Nuche E, Gárate T, et al. Human dirofilariasis in the eyelid caused by Dirofilaria repens: An imported case. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2017 Sep;92(9):439–41.

- Blaizot R, Receveur MC, Millet P, Otranto D, Malvy DJM. Systemic Infection With Dirofilaria repens in Southwestern France. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Feb 6;168(3):228–9.

- Lindner AK, Tappe D, Gertler M, Equihua Martinez G, Richter J. A live worm emerging from the eyelid. J Travel Med. 2018 Jan 1;25(1).

- Mani A, Khan MA, Kumar VP. Subcutaneous dirofilariasis of the eyelid. Med J Armed Forces India. 2019 Jan;75(1):112–4.

- Pupić-Bakrač A, Pupić-Bakrač J, Jurković D, Capar M, Lazarić Stefanović L, Antunović Ćelović I, et al. The trends of human dirofilariasis in Croatia: Yesterday - Today - Tomorrow. One Health. 2020 Dec;10:100153.

- Mihaljevic B, Ivekovic R, Zrinscak O, Vatavuk Z. [Subcutaneous Tumor of the Upper Eyelid: Infestation by Dirofilaria repens]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2020 Jan;237(1):32–4.

- Gebauer J, Ondruš J, Kulich P, Novotný L, Sałamatin R, Husa P, et al. The first case of periorbital human dirofilariasis in the Czech Republic. Parasitol Res. 2021 Feb;120(2):739–42.

- Agrawal S, Modaboyina S, Raj N, Das D, Bajaj MS. Eyelid Dirofilaria During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Telemedicine Diagnosis. Cureus. 2021 Jun;13(6):e15525.

- Tirakunwichcha S, Sansopha L, Putaporntip C, Jongwutiwes S. Case Report: An Eyelid Nodule Caused by Candidatus Dirofilaria hongkongensis Diagnosed by Mitochondrial 12S rRNA Sequence. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2022 Jan 5;106(1):199–203.

- Szostakowska B, Ćwikłowska A, Marek-Józefowicz L, Czaplewski A, Grzanka D, Kulawiak-Wasielak N, et al. Concurrent subcutaneous and ocular infections with Dirofilaria repens in a Polish patient: a case report in the light of epidemiological data. Parasitol Int. 2022 Feb;86:102481.

- Rymgayłło-Jankowska B, Ziaja-Sołtys M, Flis B, Bogucka-Kocka A, Żarnowski T. Subcutaneous Dirofilariosis of the Eyelid Brought to Poland from the Endemic Territory of Ukraine. Pathogens. 2023 Jan 28;12(2):196.

- Shaikh Z, Kar P, Mohanty S, Dey M, Samal DK. Ocular dirofilariasis: A report from Odisha. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2023;45:100388.

- Camacho M, Antonietti M, Sayegh Y, Colson JD, Kunkler AL, Clauss KD, et al. Ocular Dirofilariasis: A Clinicopathologic Case Series and Literature Review. Ocular Oncology and Pathology. 2023 Dec 9;10(1):43–52.

- Gitanjali MM, Konapur PG, Kolakkadan H, Azeez KN. Human dirofilariasis - Unforeseen lesion in subcutaneous nodules: Case series from a tertiary care hospital, Wayanad. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2024;67(1):204–6.

- Zvornicanin J, Zvornicanin E, Numanovic F, Delibegovic Z, Husic D, Gegic M. Ocular Dirofilariasis in Bosnia and Herzegovina: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2020 Jul 4;32(3):293–6.

- Trenkić BM, Otašević S, Stanković BG, Tasić A, Trenkić M. Human ocular dirofilariosis: Clinical and epidemiological features. Acta medica medianae. 2014;53(1):80–4.

- Groell R, Ranner G, Uggowitzer MM, Braun H. Orbital dirofilariasis: MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999 Feb;20(2):285–6.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).