1. Introduction

Breast cancer, a chronic disease with the highest global incidence among all cancer types and the second-highest mortality rate after lung cancer, demands immediate attention. It is the most common cancer among the female population worldwide [

1]. Indonesia the leading cancer, with a prevalence of around 16.6% and the highest mortality rate [

2].

The pathophysiology of breast cancer, a complex and evolving field, is not yet fully understood. It is believed that a multitude of risk factors contribute to the occurrence of breast cancer, necessitating a comprehensive and urgent assessment. Many instances of breast cancer originate from epithelial tumour cells that develop from ducts or lobules. The biological classification of breast cancer includes several types, such as luminal A, luminal B, positive HER-2 non-luminal, basal-like type, and specific histological types. This comprehensive assessment is crucial in our fight against breast cancer [

2,

3].

Breast cancer develops due to DNA damage and genetic mutations that can be influenced by exposure to estrogen. The immune system of an average person will attack cells with abnormal DNA or abnormal growth. Failure of the immune system to attack abnormal DNA causes tumours to grow and spread in breast cancer patients. Cancer cells are formed, and various body mechanisms react, especially from the immune system [

4]. The complex human immune system is a defence of the body to prevent the growth of dangerous cells [

5,

6].

Each breast cancer patient is unique, and their treatment is tailored to their specific subtype of cancer. This personalized approach, which may include BCT (Breast-Conserving Therapy), mastectomy, radiation therapy, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, targeted and biologic therapy, and hormone therapy, provides reassurance and a sense of understanding to patients and caregivers.

Lymphocyte-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1, also known as CD11a/CD18 and αLβ2) is a glycoprotein found on the surface of leukocytes. It is one of the many integrins in the human body that promotes adhesion in immunological and inflammatory responses. Its role is based on its preferential presence in leukocytes. ICAM-1 (Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1) is a distinct glycoprotein from the palatal surface. Its wide distribution, low inflammatory expression, and involvement in LFA-dependent palatal adhesion suggest that ICAM may be a substitute for LFA-1 [

6,

7].

A study linked LFA-1 and its primary mediator ICAM-1 (or CD54) to cancer via lymphocyte and myeloid functions in tumour cells and the role of LFA-1-containing exosomes in tumour growth and metastasis from these tumours. The interaction of LFA-1 with ICAM facilitates T-cell antigen receptor (TCR)-mediated killing [

8]. Productive LFA-1 binding is required for efficient target cell lysis by releasing cytolytic granules. LFA-1 provides a clear signal that is important in directing the released cytolytic granules to the surface of antigen-bearing target cells to mediate the efficient killing of these cells by cytotoxic T lymphocytes [

9].

Several intercellular adhesion molecules (ICAMs), including ICAM-1 and functional adhesion molecule 1, are common ligands for binding to the LFA-1 gene. The strength of LFA-1 adhesion varies according to the affinity adjustment, the level of LFA-1 Clustering, and the force applied by the ligand. LFA-1 is not an adhesive between cells but mediates signals that modulate cell growth, differentiation, and survival. A study stated that ICAM-1 is partly responsible for breast cancer metastasis through a highly intricate and multifaceted mechanism [

10]. Based on this background, the author is interested in briefly summarizing the expression of LFA-1 and ICAM-1 genes in breast cancer and the proliferation activity of breast cancer with LFA-1 antagonist and LFA-1 agonist therapy.

2. Breast Cancer

Breast cancer is a heterogeneous group of tumours originating from the epithelial cells lining the milk ducts. The disease varies greatly from patient to patient, and tumour heterogeneity can be different even within a single individual. All these diverse factors determine the risk of disease progression and resistance to therapy [

11,

12].

Heterogeneity in Clinical and Histopathological Findings Breast cancer is best classified by the clinical stage of the disease based on physical examination and supporting factors such as radiology. As medical professionals, researchers, and students in oncology, crucial role in using the TNM grouping system, adapted from the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) / Union for International Cancer Control (UICC). This system combines tumour size, regional lymph node status, and metastasis. Breast cancer classification based on gene expression analysis is categorized into four main subtypes that are intended to support therapy and prognosis, including luminal A, luminal B, HER2-enriched and basal-like types. Luminal A and luminal B subtypes show tumour heterogeneity in ER-positive breast cancer and have a better chance of survival compared to HER2-enriched and basal-like subtypes [

13]. Both luminal subtypes express estrogen receptors (ER). Furthermore, the luminal A subtype has a better prognosis than the luminal B subtype because the luminal B subtype is characterized by increased expression of proliferation-related genes [

13].

Genomic instability refers to the hallmark of cancer, which is increased genomic changes in cells. This includes changes in the slightest structural variations of cells, such as base pair changes or mutations and small insertions or deletions, or significant structural variations, such as the loss or addition of larger chromosome fragments or entire chromosome components.

The molecular classification scheme for breast cancer. The model is intended to understand how molecular subtypes fit into the initial molecular scheme of ER+/PR+, HER2+, and TNBC. The signature of the PAM50 gene organizes breast cancer into five distinct subtypes: luminal A, luminal B, normal-like, basal-like, and HER2 enriched. At the same time, TNBC subtypes are defined into four distinct subtypes: basal-like 1 (BL1), basal-like 2 (BL2), mesenchymal (M), and luminal androgen receptor (LAR). ER, estrogen receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; PAM50, microarray prediction analysis 50; PR, TNBC [

14].

Numerical chromosome instability is the addition or loss of an entire chromosome, resulting in an abnormal chromosome number, also known as aneuploidy. Several mechanisms, including defects in DNA damage repair, DNA replication, DNA segregation, and telomere stability, cause it. These mechanisms are highly interwoven and link a complex network of cellular pathways. Structural chromosome instability refers to the addition or loss of chromosome fragments or chromosomal rearrangements, resulting in translocations, duplications, and deletions, directly preceded by lesions affecting DNA repair genes, e.g., BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations [

15].

In Breast Cancer, genes that generally play a role in maintaining genome stability are often affected by germline or somatic mutations, Copy number aberrations, or changes in epigenetic control. This will mainly lead to DNA repair errors and chromosome instability, which will lead to genome instability and signs of malignancy [

16,

17].

3. LFA-1 and ICAM-1 Theory and Concepts

Lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1), or if translated into Indonesian, has the meaning of antigen that is related LFA-1. LFA-1 is a glycoprotein found on the surface of leukocyte cells that initiates intracellular adhesion bonds in immune and inflammatory responses. LFA-1 also mediates close contact between specific cells and antigens in the immune system in antigen-nonspecific interactions [

5,

18]. LFA-1 antigen is widely expressed in hematopoietic cells and is the main receptor for T cells, B cells, and granulocytes. (Simmons, Makgoba, and Seed 1988) In mice and humans, both express LFA-1 on follicular helper T cells [

19].

ICAM-1 (Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1) is a glycoprotein that is a ligand of LFA-1 expressed by Antigen Presenting Cell (APC) on the endothelium surface of blood vessels. Its wide distribution, low inflammatory expression and involvement in LFA-dependent adhesion suggest that ICAM-1 may be a substitute for LFA-1 [

5,

18]. However, a study conducted by Steven et al stated that ICAM-1 is not the only ligand of LFA-1 [

18].

Integration between ICAM-1 and LFA-1 will rapidly increase the affinity for the resulting bond, which will then respond to intracellular signals induced in all leukocytes through chemokine binding to chemokine receptors and T cells through antigen binding to antigen receptors. The involvement of chemokine and antigen receptors triggers a signaling pathway that links enzymes and proteins that interact with the cytoskeleton with the cytoplasm of integrin proteins in infection. This results in changes in the extracellular domain of integrins that cause increased affinity [

20,

21].

When there is an infection by microbes or recognition of tumor antigens by immunity, LFA-1 integrin will be activated in naive T cells, resulting in a strong bond between integrin, especially with its ligand ICAM-1 located on the surface of the endothelium. The signal sent by leukocytes mediated on the endothelium will align with integrin activation; inflammatory cytokines regulate the expression of its binding on endothelial cells. This bond includes ICAM-1, which binds LFA-1 and MAC-1 integrins [

5].

4. LFA-1 and ICAM-1 Research Results in Cancer

Cancer cells grow rapidly and change the microenvironment, a safe place for survival and cell division. Interaction with the stroma causes cancer cells to receive signals to survive and produce proteins and other substances that suppress the immune system's activity. Myeloid cells have an important role in tumor development or inhibit tumor growth [

8]. (Reina 2017)

The role of cell adhesion molecules ICAM-1, vascular endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), E-selectin, and P-selectin has been widely studied in the inflammatory process. Leukocyte adhesion during inflammation is thought to occur hierarchically, adheres to leukocytes, and mediates strong adhesion and transmigration. CD8 functions as a receptor for ICAM-1. In addition to attaching leukocytes to the endothelium, it also plays a dominant role in transendothelial migration. In addition, many studies have shown that complete inhibition of CD8, or genetic mutations, greatly reduces leukocyte transmigration at sites of inflammation [

8,

9,

22].

A study conducted [

8] found that LFA-1 has been associated with the function of myeloid cells in interactions with tumors. They also mentioned the importance of the role of LFA-1 in infiltrating tumor cells [

8]. The presence of neutrophils in the process of cancer cell division is associated with its relationship with LFA-1. Neutrophils are said to be responsible for the process of distant metastasis by breast cancer [

8].

Research Gabriela Vazquez Rodrigue et al conducted LFA-1 in neutrophils plays an important role in tumor cell division and distant metastasis in breast cancer. The study was conducted on cultured cells and showed excessive expression of LFA-1 in neutrophils [

23]. Cancer cells metastasized further, increasing the number of neutrophils in the cultured cells. In contrast, in other types of cancer, neutrophils inhibit tumor survival and prevent tumors from growing faster [

8]. This makes it important to categorize tumors supported by neutrophils with tumors inhibited by neutrophils [

8].

Mechanism of the role of CD8 + T lymphocytes which is dependent on ICAM-1-LFA-1 in cancer tissue, preventing recirculation to the draining lymph nodes. Intra-tumoral CD8+ T lymphocytes form a pool maintained in the cancer microenvironment through homotypic ICAM-1-LFA-1 interactions. ICAM-1 destroys the T cell pool and increases the sensitivity of T cells to CCL21-guided chemokine migration to lymphatic vessels, thereby facilitating their transit to the draining lymph nodes [

8].

Christine Schoder et al. showed that there is a relationship between overexpression of ICAM-1 protein and aggressiveness of breast cancer, which can be used as a determinant of breast cancer prognosis. Therefore, research targeting ICAM-1 as a therapy for breast cancer must be carried out. (Witzel, Mu, and Schro 2011) In another study, increased overexpression of ICAM-1 was found in qPCR examination of TNBC breast cancer samples through a process involving TLS (Tertiary Lymphoid Structures) in samples found positive for ICAM-1 had a high number of immune cell infiltration [

24].

Reserarch interaction between LFA-1 and its ligand ICAM-1, activating exosome attachment to CD8 T cells. Exosomes derived from tumors can suppress the proliferation and cytotoxicity of CD8 T cells. This is a prerequisite for exosomal binding to tumors and suppression of T cells. Another study linked the presence of estradiol, which plays a key role in breast cancer development, with overexpression of LFA-1 [

25]. Overexpression of LFA-1 integrin was found in estradiol-induced neutrophils in breast cancer patients [

24].

ICAM-1 plays a major role during the initiation of metastasis that drives tumor development. Expression of ICAM-1 protein by liver parenchymal and non-parenchymal cells increases its potential to facilitate disease progression. Ligand binding to ICAM-1 and overexpression of ICAM-1 in tumors contribute to the activation of several signaling pathways with key roles in different stages of metastasis development. In addition, ICAM-1 is elevated in the serum of patients with metastatic disease, recurrence, and prognosis of other cancer types [

8,

26,

27].

Endothelial ICAM-1 is involved in tumor cell adhesion to the endothelium, which is a very important phenomenon considering that tumor adhesion to the blood vessel wall is a common feature of many cancers. Ghislin et al. reported that ICAM-1 expressed on the surface of endothelial cells is essential for melanoma cell adhesion to endothelial monolayers in vitro. In this condition, ICAM-1 expression was increased after tumor stimulation, concomitant with increased tumor cell adhesion [

26,

27].

Liang et al. stated that LFA-1 expression was not detected in cancer cell molecules in the metastatic phase and then interacted with neutrophils, indicating that cancer cells used neutrophils as carriers. IL-8 signals interact with PMNs through binding between ICAM-1 on cancer cells. The authors also showed that this interaction facilitates adhesion to endothelial cells. Activation of LFA 1 in cancer cells to increase binding to ICAM-1 has a potential role in increasing the recruitment of specific T cells in cancer. Productive interaction between LFA-1 and ICAM-1 can cause cytotoxic T lymphocytes to leave the systemic circulation, infiltrate tumor tissue, and trigger proliferative role functions that result in tissue damage [

27,

28,

29].

A study on the role of ICAM-1ICAM-1 in breast cancer metastasis in the lungs illustrates the overexpression of ICAM-1ICAM-1 involvement in TNBC-type breast cancer metastasis in the lungs. ICAM-1 initiates metastasis by activating cellular pathways related to the cell cycle and stem cells [

30].

Research conducted by Changguo Chen et al. Adhesion molecule sICAM-1 with diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of 98% and 94% at a cutoff value of 20.0 (ng/mL), with an area under the characteristic curve of 0.99. Cutoff value can effectively distinguish between healthy controls and breast cancer groups. The diagnostic sensitivity and specificity were lower, at 44.6% and 94.1%, respectively. A 40 ng/mL cutoff value was identified as a value that provided a sensitivity of 44.6% and a specificity of 94.1%. Increased levels of sICAM-1-1 were also observed in most breast cancer patients, especially in patients with metastases to multiple organs [

31,

32,

33].

4. Ki-67 Research Results Review

Breast cancer research, Ki-67 expression is closely related to cancer growth and is a marker for predicting known conditions and outcomes. The level of Ki-67 expression is also useful for guiding treatment decision-making in some cases. Therefore, routine measurement of Ki-67 is now widely performed during pathological tumor evaluation. A study that took information from large cohort data showed that Ki-67 is frequently tested in daily clinical practice [

34]. Ki-67 expression is related to common histopathological parameters but is also an independent prognostic determinant of disease recurrence and survival in breast cancer patients [

35].

The emergence of molecular medicine has changed the way breast cancer is managed. Breast cancer is now considered a heterogeneous disease with various forms, molecular features, tumor behaviors, and responses to treatment strategies. This is supported by a combination of genomic and immunohistochemical factors of the tumor, such as estrogen receptor (ER) status, progesterone receptor (PgR) status, human epidermal growth factor-2 (HER2) receptor status, Ki-67 proliferation index, and multigene panel, all of which play a role in subcategorization, prognostication, and personalization of treatment modalities for each case. Ki-67 expression is closely related to tumor cell growth and proliferation and is routinely evaluated as a proliferation marker. Further efforts should focus on standardizing the Ki-67 assessment and specifying its role in treatment decision-making [

34,

35].

Ki67 is a protein that is a marker of cell proliferation. In normal, healthy breast tissue, Ki67 levels are reported to be very low, usually less than 3%. Previous studies have shown that estrogen receptor (ER) positive cells tend to receive proliferation signals by initiating DNA synthesis. In normal breast tissue, Ki67 expression is mainly seen in ER-negative cells. However, in hyperplastic tissue, the average Ki67 expression level increases to about 6.3%, and this has been associated with an increased risk of breast cancer [

25,

34,

35].

The pattern of Ki67 expression plays an important role, especially in the breast carcinogenesis phase. Several studies have found that in patients with early-stage breast cancer who have high levels of Ki67 expression, there is a higher risk of recurrence and poorer survival rates [

25,

36].

International Ki67 in Breast Cancer Working Group (IKWG) states that using Ki67 immunohistochemistry as a prognostic marker in breast cancer has limited clinical validity. Ki67 can be used as a prognostic marker in early breast cancer and can also help determine whether additional chemotherapy is needed after initial treatment. However, further research is needed to predict and monitor patient response to chemotherapy more accurately [

25,

36].

Ki67 immunohistochemistry (IHC) is indeed a valuable tool in assessing the risk of recurrence in estrogen receptor (ER)-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative breast cancer. It can be considered a surrogate marker for molecular testing, helping differentiate between luminal A and luminal B breast cancer subtypes. High Ki67 levels have been associated with good clinical response to chemotherapy, particularly in triple-negative breast cancer. However, it is important to note that although Ki67 may have some predictive value, its independent significance is limited, and it may not always be necessary to measure in routine clinical scenarios. Nonetheless, several clinical trials have provided insight into the role of Ki67 in treatment decisions [

25,

36,

37].

A trial from The European Institute of Oncology showed that high Ki67 levels (≥32%) may indicate the potential benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in luminal B breast cancer with positive lymph node metastasis. In addition, studies have shown that a high Ki67 index (≥20%) is associated with increased efficacy of docetaxel in adjuvant therapy for ER-positive breast cancer. The BCIRG001 trial showed that the TAC chemotherapy regimen (docetaxel, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide) had a significant complementary effect to endocrine therapy for patients with high Ki67 index (≥13%), ER-positive, and positive lymph nodes [

37,

38].

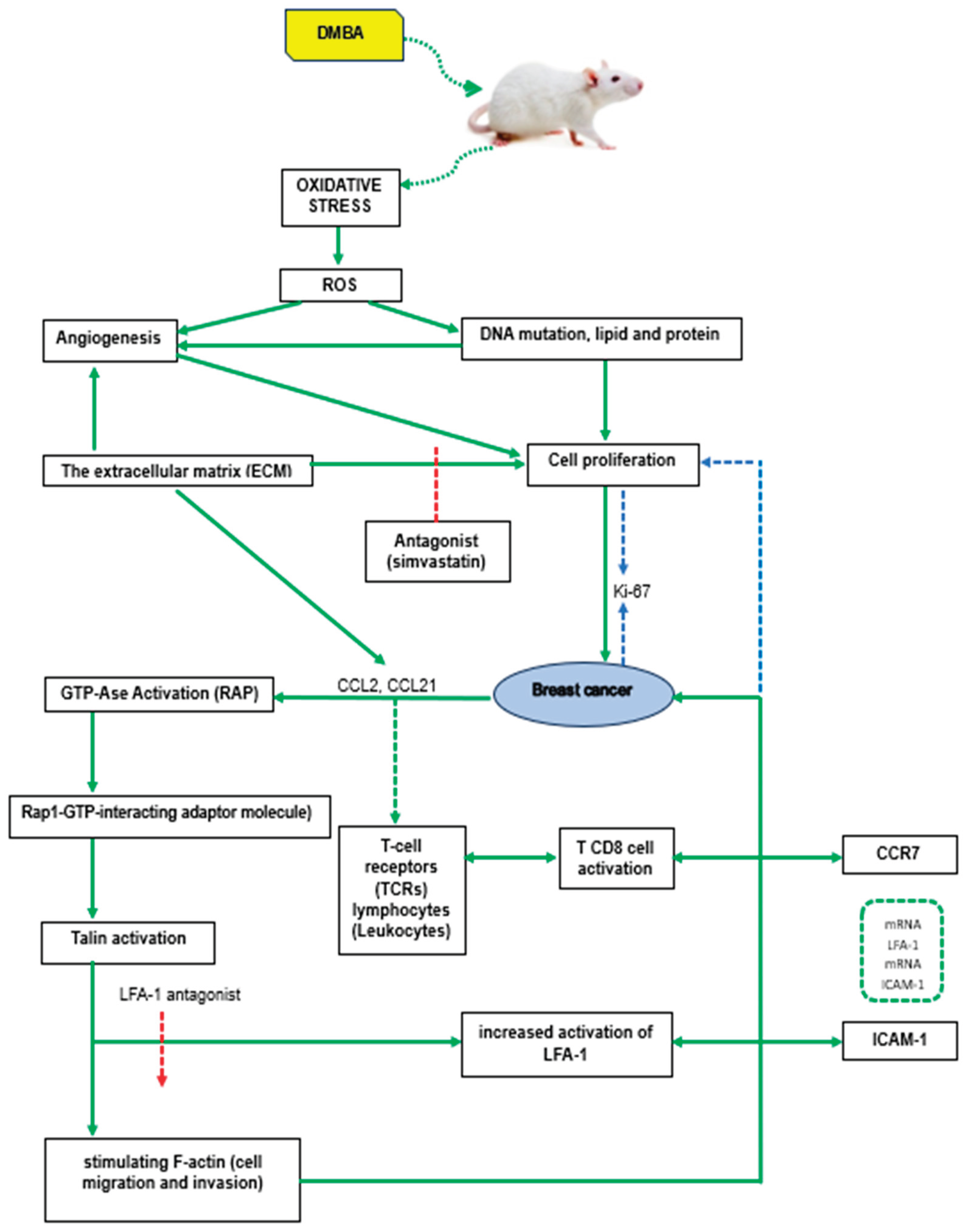

5. Main Components

DMBA (7,12-dimethylbenz(a)-anthracene) is a carcinogen that can be found in the air as an environmental pollutant, especially in motor vehicle exhaust, factory smoke, and cigarette smoke. It can transform normal cells into cancer cells, and cancers that can be induced include breast, lung, oral, and skin cancers. DMBA induces oxidative stress through enzymatic reduction of the nitro group, which produces free radical species (ROS) such as superoxide anion, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals. This can cause oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA, which in turn can trigger mutagenesis and malignant transformation [

8,

26].

Main components of the tumor microenvironment is the extracellular matrix (ECM), which is a network of proteins that interact with cell surface receptors and contain a variety of signaling molecules such as growth factors and cytokines. Talin proteins act as important adaptors that connect integrin adhesion molecules to the actin cytoskeleton within cells. In mice, there are two talin genes, Talin1 and Talin2, which encode similar proteins called talin1 and talin2. Previous studies have shown that talin1 is involved in regulating focal adhesion dynamics, cell migration, and invasion [

9,

39].

Recent studies have explored the role of talin2 in cell migration, particularly in liver carcinoma and breast cancer cells, although its role in invasion and metastasis is still not fully understood. In the recent study, talin1 expression was knocked down in human breast cancer cells using short-stranded RNA (shRNA) interference. This allowed the researchers to investigate the effects of talin2 loss on human breast cancer cell invasion. By studying talin-depleted cell lines, the researchers sought to understand how talin affects cell invasion, particularly in the context of the tumor microenvironment, specifically in breast cancer. Understanding the role of talin in cell invasion and metastasis provides information on the mechanisms underlying breast cancer development. It can also open up the potential to find new therapeutic targets that can improve therapy management in breast cancer patients [

29,

40,

41].

RAP1 Interacting Molecule (RIAM) is a multidomain protein that plays an important role in regulating various functions in immune cells, especially in KP. This domain facilitates the interaction of RIAM with mitogen-activated protein kinase to interact with membrane lipids, especially on the cell plasma membrane, after the cells are activated. RIAM has a significant role in regulating cell adhesion and migration, and also contributes to the process of KP cell invasion and migration. Tumor cell proliferation influenced by angiogenesis can be measured by the Ki-67 proliferation index.

The level of Ki-67 expression correlates with the degree of differentiation, histological type, and stage of breast cancer, and serves as an important biomarker in the diagnosis, prognosis, and selection of treatment. All this suggests that the relationship between DMBA, oxidative stress, talin regulation, LFA-1, ICAM-1 expression and cell proliferation (measured by Ki-67) is an important aspect in the pathogenesis and progression of breast cancer [

25,

37,

42,

43].

The main components are outlined in the following flow.

Figure 1.

Main components.

Figure 1.

Main components.

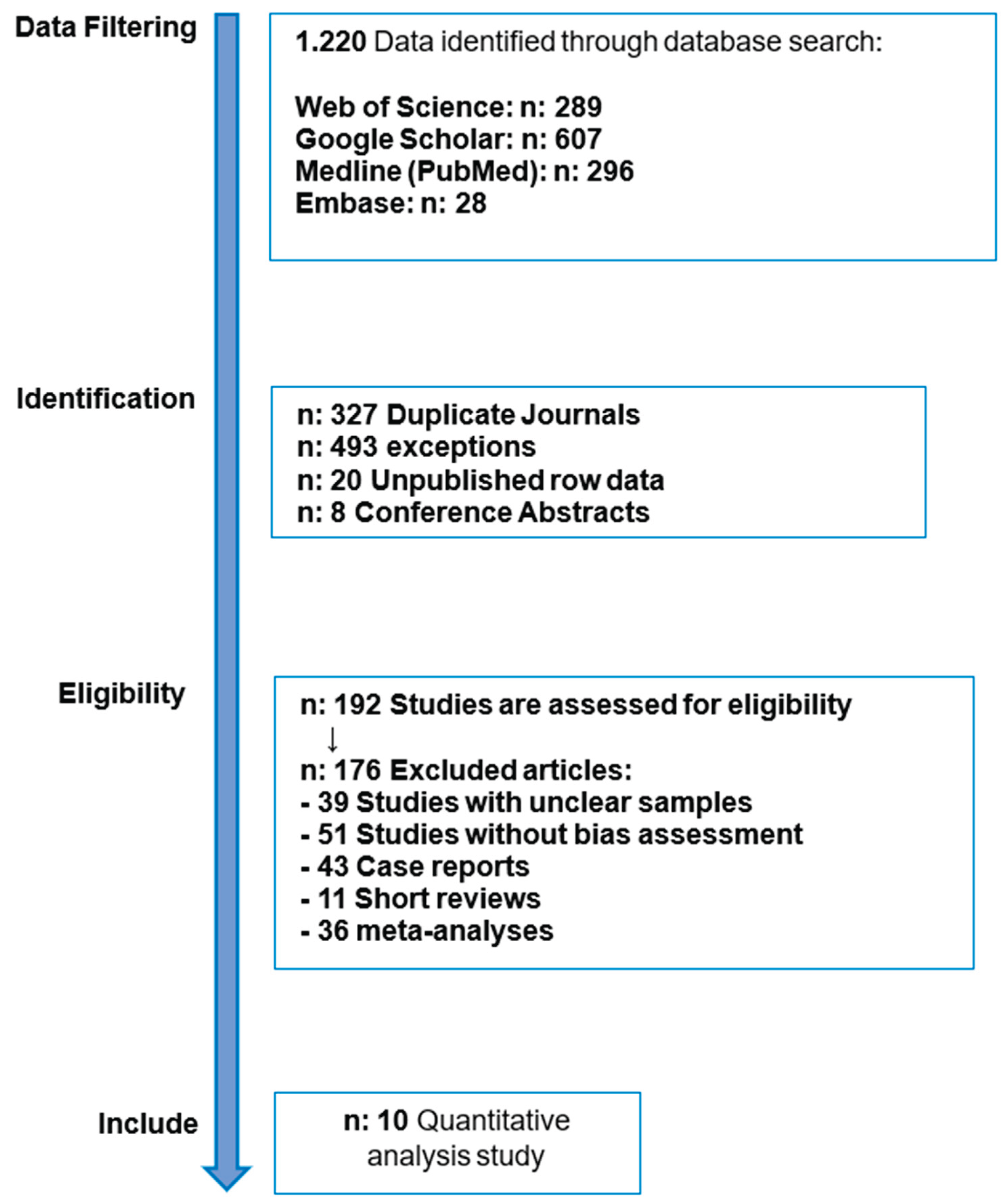

6. Literature Review Method

The article search method was based on several reports of systematic reviews and meta-analyses based on the (PRISMA) guidelines [

42] using 4 (four) electronic databases, namely Web of Science, PubMed, Embase, and Google Scholar. The keywords used followed the data search strategy analysis (

Table 1). Manual searches were also carried out on topics related to the specified theme or based on references selected from several articles. The themes were arranged in this Systematic Review using PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome) [

44].

The article identification search found 7,510 articles, resulting in 10 articles that have been filtered by considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria for each article found. The articles have calculated the explanation bias, as shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4. Ten articles meet the eligibility criteria.

Figure 2.

Article identification search process.

Figure 2.

Article identification search process.

6. Discussion

Zhang et al. stated that the underlying mechanism of Ki-67 tumour-promoting function in breast cancer had been further studied through studies involving reduced Ki-67 expression in breast cancer cell lines, such as the human MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. These studies showed that when Ki-67 expression was reduced, cancer cell proliferation and migration activities were also reduced. This suggests that Ki-67 may play a role in increasing the malignancy of breast cancer cells. Overall, these findings indicate that impaired Ki-67 expression may be involved in breast cancer development by affecting cancer cell proliferation and migration [

29].

Expression Ki-67 in the genesis and development of breast cancer, most likely affecting cancer cell proliferation and migration. Detecting and interfering with Ki-67 expression may have implications for guiding breast cancer treatment and prognosis in clinical practice. This emphasizes the potential importance of Ki-67 as a therapeutic target and prognostic marker in breast cancer management [

37,

46].

A study by Jacqueline Brown et al. showed that Ki-67 testing is not commonly used in patients in the US with early-stage hormone receptor-positive (HR+), HER2-negative breast cancer. However, this study suggests that the Ki-67 score has the potential to serve as a valuable prognostic marker to aid in treatment decisions for patients with HR+, HER2-negative early breast cancer who are at intermediate risk for disease recurrence [

51].

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, patients with HR+, HER2-negative early breast cancer are predominantly treated with endocrine therapy (ET) with or without chemotherapy (CT). This treatment approach is consistent with current recommendations and underscores the importance of Ki-67 testing as a potential additional tool to refine treatment decisions for this patient population [

25,

52].

Anette H. Skjervold et al., it was found that the assessment of Ki-67 levels in breast tumours using Digital Image Analysis (DIA) identified a higher proportion of cases with high Ki-67 levels compared to Visual Assessment (VA) in the same tumour. When using VA, the results did not change significantly with increasing number of cells counted. However, it is suggested that with DIA, it may be sufficient to count 100-200 cells in a digitally selected area to identify the most significant number of cases of high Ki-67 tumours [

43].

The results of the current study by Nahed A. Soliman et al. indicate that Ki-67 levels have the potential to be an important biomarker in breast cancer management, especially in the selection of treatment and subsequent patient monitoring. Standardization efforts should focus on developing a consistent methodology for measuring Ki-67 levels across laboratories and institutions. In addition, future research should focus on clarifying specific clinical scenarios in which information on Ki-67 levels makes the most important contribution to treatment decision-making [

46].

Significant progress has been made in identifying prognostic and predictive factors that are important for early breast cancer treatment. The role of pathologists in defining biomarkers is crucial, and they must have a comprehensive understanding of these topics. However, challenges remain in biomarker and prognostic/predictive testing, providing ongoing opportunities for further research and refinement [

22,

41].

According to literature, Carlo Pescia et al. Early breast cancer risk assessment involves the analysis of multiple biomarkers and clinicopathological features. Fundamental histopathological characteristics such as tumour size, lymph node status, grade, and hormone receptor status are important in determining prognosis and guiding treatment decisions. In addition, biomarkers such as Ki-67 proliferation index, HER2/neu expression, and genetic markers such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations provide valuable information for risk stratification and treatment selection. Integrating these factors allows for a comprehensive risk assessment and personalized management approach in early breast cancer patients [

47].

The recommendations provided by the International Ki-67 in Breast Cancer Working Group (IKWG) are critical in setting standards for validating Ki-67 analysis in diagnosing and treating breast cancer. By following these recommendations, laboratories can ensure that Ki-67 testing is performed accurately and consistently across laboratories. This will improve the reliability of test results and help clinicians make better treatment decisions for breast cancer patients [

41,

47].

Meta-analysis that evaluated the impact of Ki-67/MIB-1 on disease-free survival and/or overall survival. The study included Sixty-eight trials and 46 studies involving 12,155 patients; 38 studies were evaluable for disease-free survival outcomes, and 35 studies for overall survival. Ki-67/MIB-1 positivity was associated with a higher likelihood of relapse in all patients, patients without affected lymph nodes (node-negative) and those with affected lymph nodes (node-positive). In addition, Ki-67/MIB-1 positivity was associated with worse survival in all node-negative and node-positive patients. The study concluded that Ki-67 positivity indicates high recurrence and poorer survival [

53].

The role of Ki67 in breast cancer and the standardization efforts undertaken by the “International Ki67 in Breast Cancer Working Group”. Their recommendations are critical to improving the consistency and validity of using Ki67 as a clinical practice and research biomarker. With clear guidelines, it is hoped that the interpretation and application of Ki67 will become more consistent across laboratories and studies, allowing for its more practical use in guiding patient prognosis, predicting response to therapy, and better-managing breast cancer clinically [

54,

55,

56].

The study of Ayat Lashen et al., it was found that Ki67 staining with a homogeneous pattern was generally found in about 80% of breast cancers. On the other hand, the granular pattern was strongly associated with DMFS (distant metastasis-free survival) and was an independent prognostic factor. This suggests that the granular pattern can provide valuable information about patient prognosis. Based on this, the quantification method per 1000 cells is considered a feasible Ki67 assessment method because it has been shown to have the highest risk of harm. The heterogeneity of Ki67 staining and its expression pattern can provide additional information about clinical outcomes in breast cancer [

49].

Research Julia Fekadu et al. stated that LFA-1 is important in mediating leukocyte adhesion, movement, and forming adhesions between immune cells. The leukocyte adhesion cascade begins with inflammation that causes endothelium activation by endogenous and exogenous stimuli. Expressed on the surface of activated endothelial cells, it mediates leukocyte adhesion to the surface of blood vessels. The interaction between β2-integrin LFA-1 and ICAM-1 allows leukocytes to adhere to the endothelium in the inflammatory phase [

48].

Joshua J. Sanchez et al. reported that LFA-1 affects the development of pathological pain through changes in function and increased sensitivity of astrocytes to cytokines. By antagonizing LFA-1 activation, there is a change in the local environment in the spinal cord from a pro-inflammatory phenotype to an anti-inflammatory phenotype [

50].

Systematic study targeting LFA-1 as a therapy in breast cancer. Both support LFA-1 with its primary ligand, ICAM-1 or inhibit its binding with its inhibitor.

7. Conclusion

The conclusion of this brief review is to find out the research on the role of LFA-1 and ICAM-1 in breast cancer proliferation given LFA-1 antagonist and agonist therapy. The data obtained in this paper can be used as an essential reference for indicators of immunological component examination in breast cancer patients. The benefit of knowing the role of LFA-1 and ICAM-1 in breast cancer is that we can further study the involvement of LFA-1 and ICAM-1 in breast cancer.

The relationship between LFA-1 and ICAM-1 mRNA expression with the administration of LFA-1 antagonist and agonist therapy is to be a reference for finding treatment in terms of inhibiting breast cancer proliferation activity, which provides new knowledge in the medical world, especially in the field of oncology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.E.M. and A.A.I.; methodology, Z.E.M. and M.H.; validation, Z.E.M., P.P., and N.F.A.P.; formal analysis, Z.E.M.; investigation, Z.E.M.; resources, M.H.; data curation, Z.E.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.E.M.; writing—review and editing, A.A.I. and P.P.; visualization, Z.E.M.; supervision, A.A.I. and P.P.; project administration, A.A.I.; funding acquisition, Z.E.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the corresponding author (Z.E.M.) personally.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editorial and technical staff who provided support during the preparation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this review, the authors used ChatGPT-4 (OpenAI, 2024) to assist with language refinement and organization of the draft. All content was carefully reviewed and edited by the authors, who take full responsibility for its final form.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LFA-1 |

Lymphocyte Function-Associated Antigen 1 |

| ICAM-1 |

Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 |

| Ki-67 |

Antigen Identified by Monoclonal Antibody Ki-67 (a cellular proliferation marker) |

| TCR |

T-Cell Receptor |

| NK cells |

Natural Killer Cells |

| ER |

Estrogen Receptor |

| PR |

Progesterone Receptor |

| HER2 |

Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| TNBC |

Triple Negative Breast Cancer |

| IHC |

Immunohistochemistry |

| TLS |

Tertiary Lymphoid Structures |

| DMBA |

7,12-Dimethylbenz[a]anthracene |

| ECM |

Extracellular Matrix |

| RIAM |

RAP1 Interacting Adaptor Molecule |

| APC |

Antigen-Presenting Cell |

| CT |

Chemotherapy |

| ET |

Endocrine Therapy |

| NCCN |

National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| AJCC |

American Joint Committee on Cancer |

| UICC |

Union for International Cancer Control |

| PRISMA |

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

References

- Sung, Hyuna, Jacques Ferlay, Rebecca L. Siegel, Mathieu Laversanne, Isabelle Soerjomataram, Ahmedin Jemal, and Freddie Bray. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2021, 71(3):209–49. [CrossRef]

- Fachri, Muhammad, Mochammad Hatta, Muhammad Nasrum Massi, Arif Santoso, Tri Ariguntar Wikanningtyas, Ressy Dwiyanti, Ade Rifka Junita, Muhammad Reza Primaguna, and Muhammad Sabir. The Strong Correlation between ADAM33 Expression and Airway Inflammation in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Candidate for Biomarker and Treatment of COPD. Scientific Reports 2021, 11(1):1–13. [CrossRef]

- Choi, Lydia. MSD Manuals Professional Version. in MSD Manuals Global Medical Knowledge 2022. Rahway, NJ.

- Alkabban, Fadi M., and Troy Ferguson. 2022. Breast Cancer. Updated 20. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

- Abbas, Abul K., Andrew H. Lichtman, and Shiv Pillai. 2016. Basic Immunology. 5th ed. Singapore: Elsevier.

- Hatta, Mochammad, Eko E. Surachmanto, Andi Asadul Islam, and Syarifuddin Wahid. Expression of MRNA IL-17F and SIL-17F in Atopic Asthma Patients. BMC Research Notes 2017, 10(1):1–5. [CrossRef]

- Junita, Ade Rifka, Firdaus Hamid, Budu Budu, Rosdiana Natzir, Yusmina Hala, Gemini Alam, Rosana Agus, Burhanuddin Bahar, Ahmad Syukri, Muhammad Reza Primaguna, Ressy Dwiyanti, Andini Febrianti, Muhammad Sabir, Azhar Azhar, and Mochammad Hatta. A Potential Mechanism of Miana (Coleus Scutellariodes) and Quercetin via NF-ΚB in Salmonella Typhi Infection. Heliyon 2023. 9(11): e22327. [CrossRef]

- Reina, Manuel. Role of LFA-1 and ICAM-1 in Cancer. Cancer MDPI 2017, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Fantozzi, A., & Christofori, G. Mouse models of breast cancer metastasis. Breast Cancer Research 2006, 8, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Anikeeva, Nadia, Kristina Somersalo, Tasha N. Sims, V. Kaye Thomas, Michael L. Dustin, and Yuri Sykulev. Distinct Role of Lymphocyte Function-Associated Antigen-1 in Mediating Effective Cytolytic Activity by Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes. PNAS 2005, 102(18). [CrossRef]

- Rosette, Caridad, Richard B. Roth, Paul Oeth, Andreas Braun, Stefan Kammerer, and Jonas Ekblom. Role of ICAM1 in Invasion of Human Breast Cancer Cells. Carcinogenesis 2005, 26(5):943–50. [CrossRef]

- Polyak, Kornelia. Review Series Introduction Heterogeneity in Breast Cancer. 2011, 121(10).

- Turashvili, Gulisa, and Edi Brogi. 2017. “Tumor Heterogeneity in Breast Cancer.” 4(December). [CrossRef]

- Gao, J. J., & Swain, S. M. Luminal A Breast Cancer and Molecular Assays: A Review. The Oncologist 2018, 23(5), 556–565. [CrossRef]

- Turner, Kevin M., Syn Kok Yeo, Tammy M. Holm, and Elizabeth Shaughnessy. Dynamic Tumor Heterogeneity and Cancer Progression Heterogeneity within Molecular Subtypes of Breast Cancer. Amercican Journal of Physiology, Cell Physiology 2023, 343–544. [CrossRef]

- Couch, S. M., Chatzopoulos, E., Arnett, W. D., & Timmes, F. X. The three-dimensional evolution to core collapse of a massive star. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 2015, 808(1);1-7. [CrossRef]

- Lhota, F., Zemankova, P., Kleiblova, P., Soukupova, J., Vocka, M., Stranecky, V., ... & Kleibl, Z. Hereditary truncating mutations of DNA repair and other genes in BRCA1/BRCA2/PALB2-negatively tested breast cancer patients. Clinical genetics 2016, 90(4), 324-333. [CrossRef]

- Gollin, Susanne M. Mechanisms Leading to Chromosomal Instability. Proquest 2005, 15:33–42. [CrossRef]

- Meli, Alexandre P., Ghislaine Fonte, Danielle T. Avery, Deborah J. Fowell, Stuart G. Tangye, Irah L. King, Danielle T. Avery, Scott A. Leddon, Mifong Tam, Michael Elliot, Alexandre P. Meli, and Ghislaine Fonte. The Integrin LFA-1 Controls T Follicular Helper Cell Generation and Maintenance Article the Integrin LFA-1 Controls T Follicular Helper Cell Generation and Maintenance. Immunity 2016, 831–846. [CrossRef]

- Baratawidjaja, K. G., & Dasar, R. I. I. Edition 10. Jakarta: Badan Penerbit Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Indonesia, 2010.

- Kalim, H., Handono, K., Wahono, C. S., Darinafitri, I., Rahman, P. A., Febriliant, M. R., & Manugan, R. A. Reumatologi Dasar. Universitas Brawijaya Press, 2019.

- Borowsky, Alexander. Special Considerations in Mouse Models of Breast Cancer. Breast Disease 2007, 28:29–38. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, Gabriela Vazquez, Annelie Abrahamsson, Lasse Dahl, and Ejby Jensen. Estradiol Promotes Breast Cancer Cell Migration via Recruitment and Activation of Neutrophils. Cancer Immunol Research 2017, 5 (3):234–247. [CrossRef]

- Figenschau, Stine L., Erik Knutsen, Ilona Urbarova, Christopher Fenton, Bryan Elston, Maria Perander, Elin S. Mortensen, and Kristin A. Fenton. ICAM1 Expression Is Induced by Proinflammatory Cytokines and Associated with TLS Formation in Aggressive Breast Cancer Subtypes. Scientific Reports 2018, (July):1–12. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Wei, Wenqun Zhong, Beike Wang, George Daaboul, Wei Zhang, Wenqun Zhong, Beike Wang, Jiegang Yang, Jingbo Yang, Ziyan Yu, Zhiyuan Qin, and Alex Shi. Article ICAM-1-Mediated Adhesion Is a Prerequisite for Exosome-Induced T Cell Suppression Ll Ll Article ICAM-1-Mediated Adhesion Is a Prerequisite for Exosome-Induced T Cell Suppression. Developmental Cell 2022, 57(3):329–343.e7. [CrossRef]

- Benedicto, Aitor, Irene Romayor, and Beatriz Arteta. Role of Liver ICAM-1 in Metastasis. Oncology Letters 2017, 14(4):3883–3892. [CrossRef]

- Ghislin, S., Obino, D., Middendorp, S., Boggetto, N., Alcaide-Loridan, C., & Deshayes, F. LFA-1 and ICAM-1 expression induced during melanoma-endothelial cell co-culture favors the transendothelial migration of melanoma cell lines in vitro. BMC Cancer 2012, 12(1), 455. [CrossRef]

- Iverson, B. L., & Dervan, P. B. Adenine-specific DNA chemical sequencing reaction. In Methods in Enzymolog 1993, (Vol. 218, pp. 222-227). [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Li, Wei Li, and Ce Shi Chen. Breast Cancer Animal Models and Applications. Zoological Research 2020, 41(5):477–494. [CrossRef]

- Taftaf, R., Liu, X., Singh, S., Jia, Y., Dashzeveg, N. K., Hoffmann, A. D., & Liu, H. ICAM1 initiates CTC cluster formation and trans-endothelial migration in lung metastasis of breast cancer. Nature Communications 2021, 12(1), 4867. [CrossRef]

- Dyan, B., Seele, P. P., Skepu, A., Mdluli, P. S., Mosebi, S., & Sibuyi, N. R. S. A Review of the Nucleic Acid-Based Lateral Flow Assay for Detection of Breast Cancer from Circulating Biomarkers at a Point-of-Care in Low Income Countries. Diagnostics 2022, 12(8), 1973. [CrossRef]

- Eiro, N., Gonzalez, L., Fraile, M., Cid, S., Schneider, J., & Vizoso, F. Breast Cancer Tumor Stroma: Cellular Components, Phenotypic Heterogeneity, Intercellular Communication, Prognostic Implications and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cancers MPDI 2019, 11(5), 664. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Zhu, X., Yi, C., Yang, H., Hou, X., Liao, X., & Zhou, X. An efficient NiFe binary alloy anode catalyst for direct borohydride fuel cells. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 472, 145097. [CrossRef]

- Davey, M. S., Davey, M. G., Hurley, R., Hurley, E. T., & Pauzenberger, L. Return to Play Following COVID-19 Infection—A Systematic Review of Current Evidence. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation 2022, 31(2), 218–223. [CrossRef]

- Inwald, E. C., Klinkhammer-Schalke, M., Hofstädter, F., Zeman, F., Koller, M., Gerstenhauer, M., & Ortmann, O. Ki-67 is a prognostic parameter in breast cancer patients: results of a large population-based cohort of a cancer registry. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2013, 139(2), 539–552. [CrossRef]

- Shiri, R., El-Metwally, A., Sallinen, M., Pöyry, M., Härmä, M., & Toppinen-Tanner, S. The role of continuing professional training or development in maintaining current employment: A systematic review. In Healthcare MDPI 2023, (Vol. 11, No. 21, p. 2900). [CrossRef]

- Finkelman, Brian S., Huina Zhang, David G. Hicks, and Bradley M. Turner. The Evolution of Ki-67 and Breast Carcinoma: Past Observations, Present Directions, and Future Considerations. Cancers MDPI 15(3). [CrossRef]

- Niu, Ting, Zhengyang Li, Yiting Huang, Yuxiang Ye, Yilong Liu, Zhijin Ye, Lingbi Jiang, Xiaodong He, Lijing Wang, and Jiangchao Li. LFA-1 Knockout Inhibited the Tumor Growth and Is Correlated with Treg Cells. Cell Communication and Signaling 2023, 21(1):1–13. [CrossRef]

- Yanguas, Alba, Saray Garasa, Álvaro Teijeira, Cristina Aubá, Ignacio Melero, and Ana Rouzaut. ICAM-1-LFA-1 Dependent CD8+ T-Lymphocyte Aggregation in Tumor Tissue Prevents Recirculation to Draining Lymph Nodes. Frontiers in Immunology 2018. 9(SEP):1–14. [CrossRef]

- Iorns, Elizabeth, Katherine Drews-Elger, Toby M. Ward, Sonja Dean, Jennifer Clarke, Deborah Berry, Dorraya El Ashry, and Marc Lippman. A New Mouse Model for the Study of Human Breast Cancer Metastasis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7(10). [CrossRef]

- Jenie, R. I., & Meiyanto, E. Ko-kemoterapi ekstrak etanolik daun sambung nyawa (Gynura procumbens (Lour.) Merr.) dan Doxorubicin pada sel kanker payudara. Majalah Farmasi Indonesia 2007, 18(2), 81-87.

- Nielsen, Torsten O., Samuel C. Y. Leung, David L. Rimm, Andrew Dodson, Balazs Acs, Sunil Badve, Carsten Denkert, Matthew J. Ellis, Susan Fineberg, Margaret Flowers, Hans H. Kreipe, Anne Vibeke Laenkholm, Hongchao Pan, Frédérique M. Penault-Llorca, Mei Yin Polley, Roberto Salgado, Ian E. Smith, Tomoharu Sugie, John M. S. Bartlett, Lisa M. McShane, Mitch Dowsett, and Daniel F. Hayes. Assessment of Ki67 in Breast Cancer: Updated Recommendations from the International Ki67 in Breast Cancer Working Group. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2021, 113(7):808–819. [CrossRef]

- Skjervold, Anette H., Henrik Sahlin Pettersen, Marit Valla, Signe Opdahl, and Anna M. Bofin. Visual and Digital Assessment of Ki-67 in Breast Cancer Tissue - a Comparison of Methods. Diagnostic Pathology 2022, 17(1):1–14. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, L. S., Wijesiri, B., Ayoko, G. A., Egodawatta, P., & Goonetilleke, A. Water-sediment interactions and mobility of heavy metals in aquatic environments. Water Research 2021, 117386. [CrossRef]

- Patel, A., Bilinska, J., Tam, J. C., Fontoura, D. D. S., Mason, C. Y., Daunt, A., & Nori, A. Clinical features and novel presentations of human monkeypox in a central London centre during the 2022 outbreak: descriptive case series. BMJ 2022, 378. [CrossRef]

- Soliman, Nahed A., and Shaimaa M. Yussif. Ki-67 as a Prognostic Marker According to Breast Cancer Molecular Subtype. Cancer Biology and Medicine 2016, 13(4):496–504. [CrossRef]

- Pescia, Carlo, Elena Guerini-Rocco, Giuseppe Viale, and Nicola Fusco. Advances in Early Breast Cancer Risk Profiling: From Histopathology to Molecular Technologies. Cancers 2023, 15(22):1–15. [CrossRef]

- Fekadu, Julia, Ute Modlich, Peter Bader, and Shahrzad Bakhtiar. Understanding the Role of LFA-1 in Leukocyte Adhesion Deficiency Type I (LAD I): Moving towards Inflammation?” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23(7). [CrossRef]

- Wahab, N., Miligy, I. M., Dodd, K., Sahota, H., Toss, M., Lu, W., & Minhas, F. Semantic annotation for computational pathology: multidisciplinary experience and best practice recommendations. The Journal of Pathology: Clinical Research 2022, 8(2), 116-128. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, Joshua J., Jacob E. Sanchez, Shahani Noor, Chaselyn D. Ruffaner-Hanson, Suzy Davies, Carston R. Wagner, Lauren L. Jantzie, Nikolaos Mellios, Daniel D. Savage, and Erin D. Milligan. Targeting the Β2-Integrin LFA-1, Reduces Adverse Neuroimmune Actions in Neuropathic Susceptibility Caused by Prenatal Alcohol Exposure. Acta Neuropathologica Communications 2019, 7(1):54. [CrossRef]

- Zambelli, A., Gallerani, E., Garrone, O., Pedersini, R., Caremoli, E. R., Sagrada, P., ... & Cazzaniga, M. E. Working tables on Hormone Receptor positive (HR+), Human Epidermal growth factor Receptor 2 negative (HER2-) early stage breast cancer: defining high risk of recurrence. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 2023, 191, 104104. [CrossRef]

- Hacking, S. M., Yakirevich, E., & Wang, Y. From immunohistochemistry to new digital ecosystems: A state-of-the-art biomarker review for precision breast cancer medicine. Cancers 2022., 14(14), 3469. [CrossRef]

- Ades, F., Zardavas, D., Bozovic-Spasojevic, I., Pugliano, L., Fumagalli, D., de Azambuja, E., Viale, G., Sotiriou, C., & Piccart, M.. Luminal B Breast Cancer: Molecular Characterization, Clinical Management, and Future Perspectives. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2014, 32(25), 2794–2803. [CrossRef]

- Kris, M. G., Camidge, D. R., Giaccone, G., Hida, T., Li, B. T., O'connell, J., ... & Jänne, P. A. Targeting HER2 aberrations as actionable drivers in lung cancers: phase II trial of the pan-HER tyrosine kinase inhibitor dacomitinib in patients with HER2-mutant or amplified tumors. Annals of Oncology 2015, 26(7), 1421-1427. [CrossRef]

- Dowsett, M., Nielsen, T. O., Rimm, D. L., & Hayes, D. F. Ki67 as a Companion Diagnostic: Good or Bad News? Journal of Clinical Oncology 2022, 40(33), 3796–3799. [CrossRef]

- Shim, Veronica C., Robin J. Baker, Wen Jing, Roisin Puentes, Sally S. Agersborg, Thomas K. Lee, Wamda GoreaI, Ninah Achacoso, Catherine Lee, Marvella Villasenor, Amy Lin, Malathy Kapali, and Laurel A. Habel. Evaluation of the International Ki67 Working Group Cut Point Recommendations for Early Breast Cancer: Comparison with 21-Gene Assay Results in a Large Integrated Health Care System. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2024, 203(2):281–289. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).