Submitted:

24 June 2025

Posted:

24 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling of Mineral Water

2.2. Studied Compounds, Materials and Reagents

2.2. Cell Line and Subcultivation

2.3. Cell Viability Assay

2.4. Induction of Inflammation

2.5. Gene Expression Analysis

2.5.1. Total RNA Extraction

2.5.2. Reverse Transcription

2.5.3. Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT PCR)

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

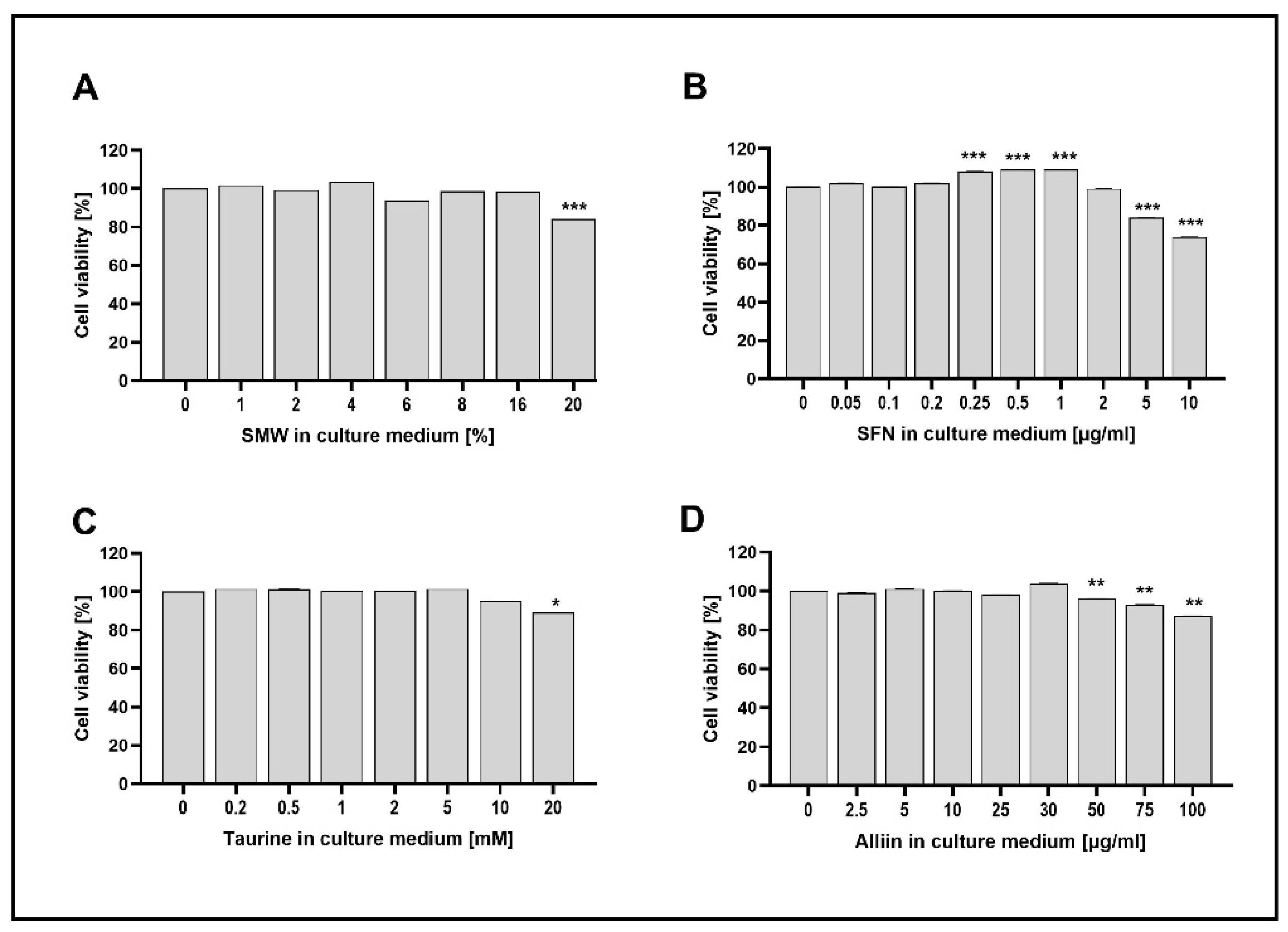

3.1. Cell Viability

3.2. Expression of Target Genes in a Model of LPS-Induced Inflammation

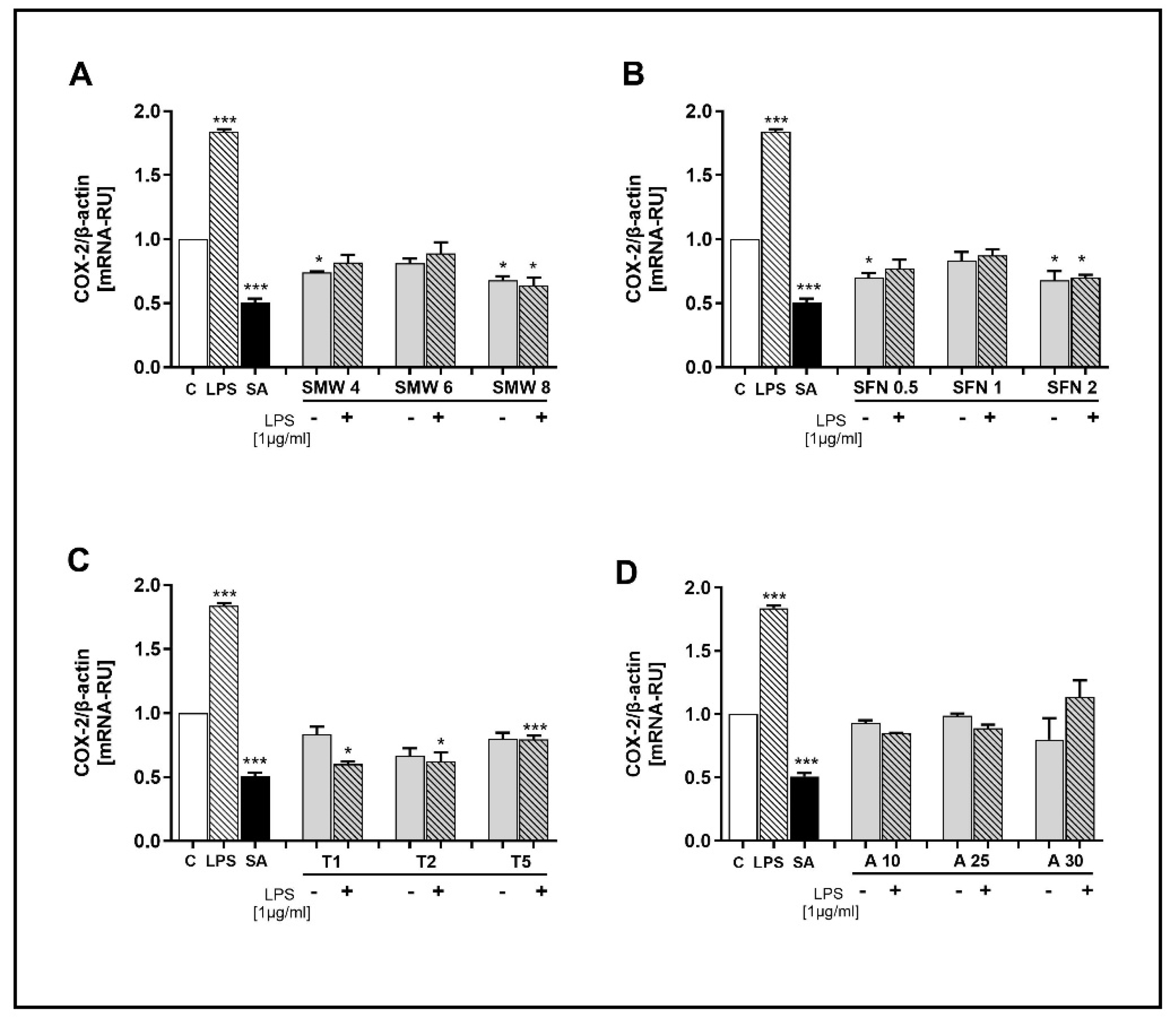

3.2.1. Effect of SMW and SBAC on COX-2 Expression

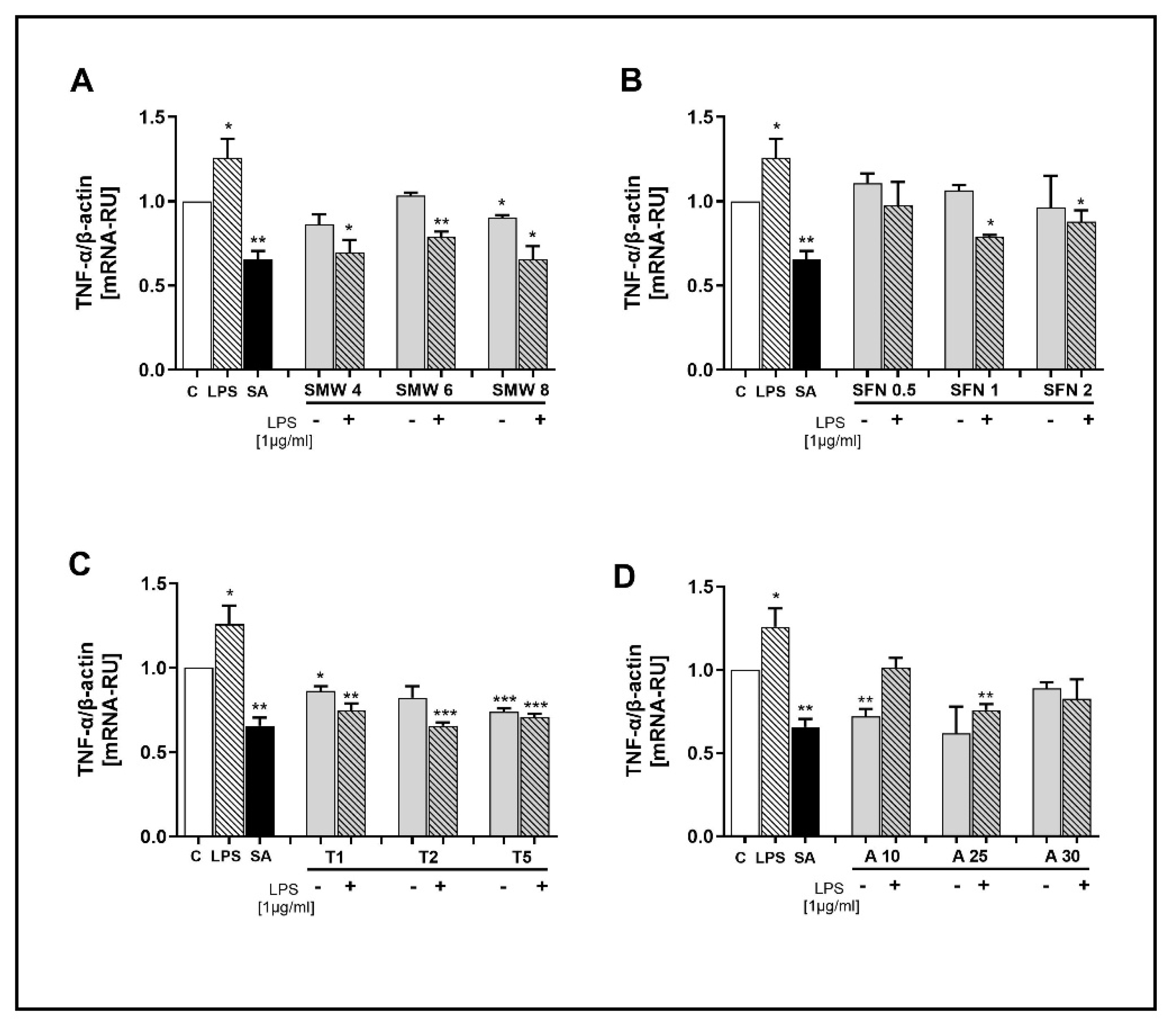

3.2.2. Effect of SMW and SBAC on TNF-α Expression

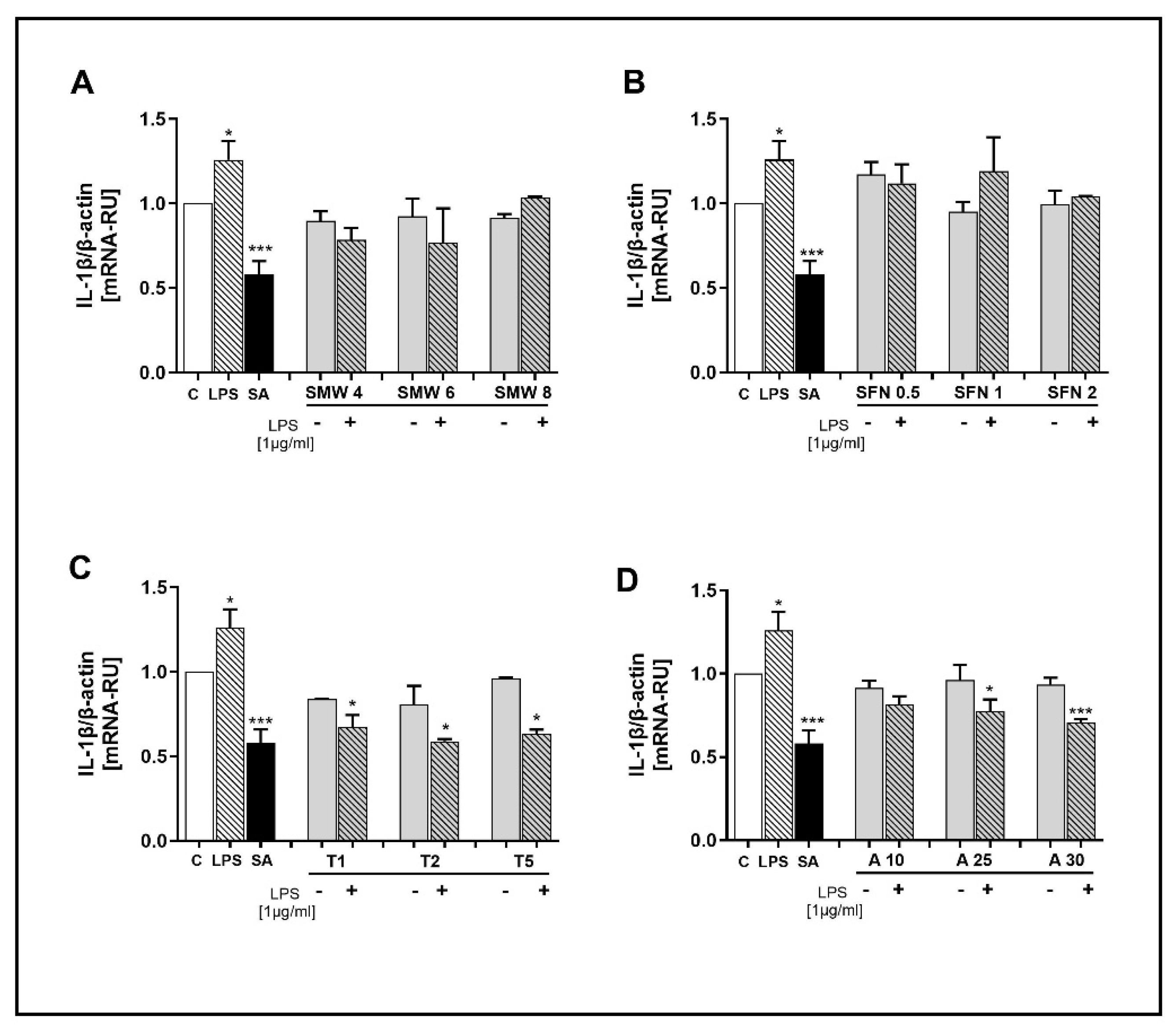

3.2.3. Effect of SMW and SBACon IL-1β Expression

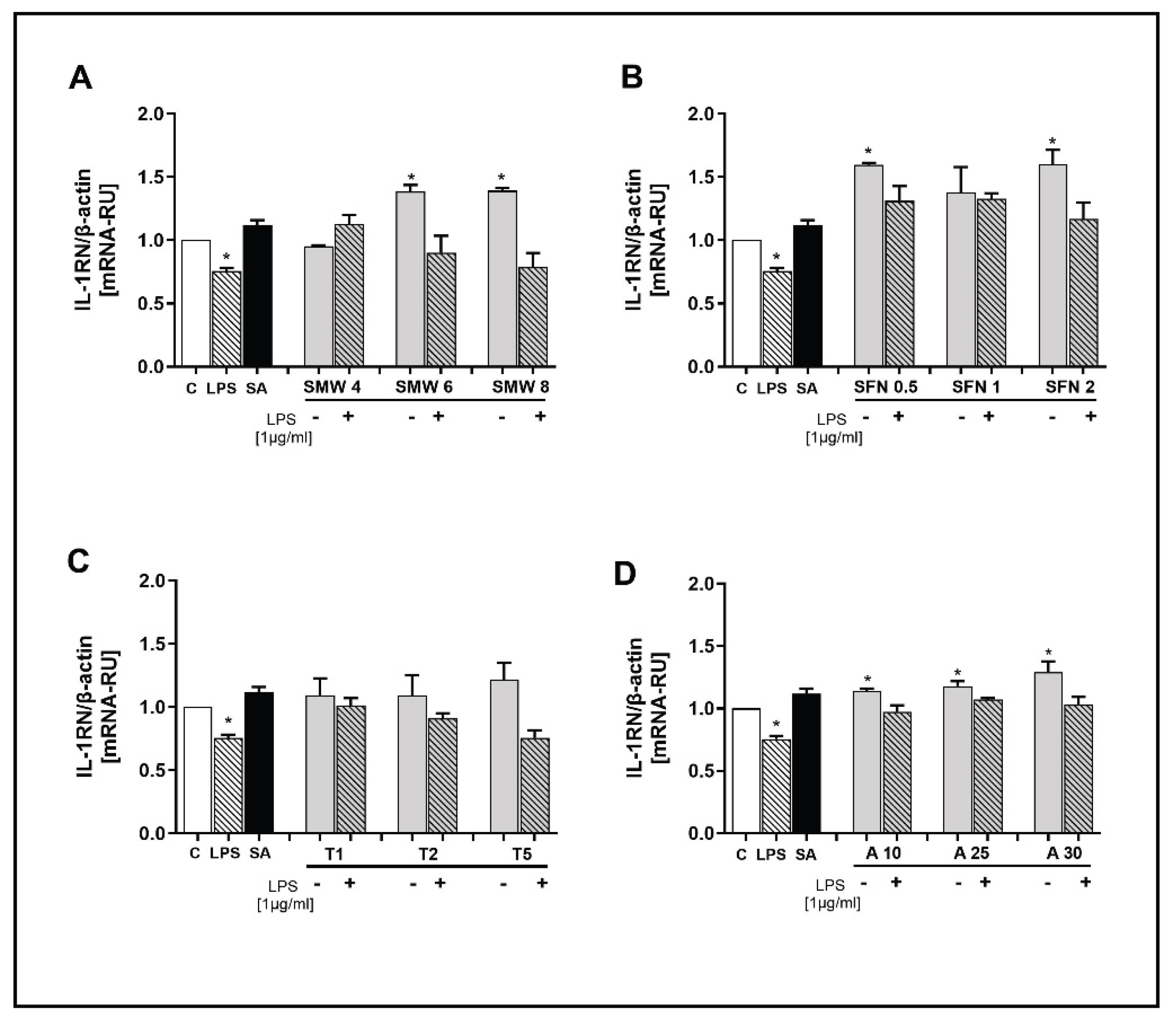

3.2.4. Effect of SMW and SBACon IL-1RN Expression

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of SMW and SBAC on Cell Viability

4.2. Effects of SMW and SBAC on COX-2 Gene Expression

4.3. Effects of SMW and SBAC on TNF-α Gene Expression

4.4. Effects of SMW and SBAC on IL-1β Gene Expression

4.5. Effects of SMW and SBAC on IL1RN Gene Expression

5. Conclusions

Funding

Author Contributions Conceptualization

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A | Alliin |

| COX-2 | Inducible cyclooxygenase |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| H2S | Hydrogen sulfide |

| IL-1RN | IL-1β receptor antagonist |

| IL-1β | Interleukin -1β |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| SBAC | Sulfur-containing biologically active compounds |

| SFN | Sulforaphane |

| SMW | Sulphur-containing mineral waters |

| TAU | Taurine |

| TNF-α | Tumour necrosis factor alpha |

References

- Bálint, G.P.; Buchanan, W.W.; Adám, A.; Ratkó, I.; Poór, L.; Bálint, P.V.; Somos, E.; Tefner, I.; Bender, T. The effect of the thermal mineral water of Nagybaracska on patients with knee joint osteoarthritis—a double blind study. Clin. Rheumatol. 2007, 26(6), 890–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.P.; Choi, Y.J.; Cho, K.A.; Woo, S.Y.; Yun, S.T.; Lee, J.T.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, J.W. Effect of spa spring water on cytokine expression in human keratinocyte HaCaT cells and on differentiation of CD4(+) T cells. Ann. Dermatol. 2012, 24(3), 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seite, S. Thermal waters as cosmeceuticals: La Roche-Posay thermal spring water example. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 6, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branco, M.; Rêgo, N.N.; Silva, P.H.; Archanjo, I.E.; Ribeiro, M.C.; Trevisani, V.F. Bath thermal waters in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2016, 52(4), 422–430. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carbajo, J.M.; Maraver, F. Sulphurous mineral waters: New applications for health. Evid.-Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2017, 2017, 8034084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussev, B.; Sokrateva, T.; Nashar, M.; Radanova, M.; Komosinska-Vassev, K.; Olczyk, P.; Potoroko, I.; Ivanova, D. Effect of sulfur-containing mineral water on the renal function: a human interventional study. Compt. Rend. Acad. Bulg. Sci. 2019, 72(11), 1577–1584. [Google Scholar]

- Sokrateva, T.; Roussev, B.; Nashar, M.; Kiselova-Kaneva, Y.; Mihaylova, G.; Todorova, M.; Pasheva, M.; Tasinov, O.; Nazifova-Tasinova, N.; Vankova, D.; Ivanova, D.P.; Radanova, M.; Galunska, B.; Vlaykova, T.; Ivanova, D.G. Effects of sulfur-containing mineral water intake on oxidative status and markers for inflammation in healthy subjects. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 127(4), 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, M.; Conti, V.; Corbi, G.; Filippelli, A. Hydropinotherapy with sulphurous mineral water as complementary treatment to improve glucose metabolism, oxidative status, and quality of life. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagülle, M.Z; Karagülle, M.; Kılıç, S.; et al. . In vitro evaluation of natural thermal mineral waters in human keratinocyte cells: a preliminary study. Int J Biometeorol, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheleschi, S.; Gallo, I.; Tenti, S. A comprehensive analysis to understand the mechanism of action of balneotherapy: why, how, and where they can be used? Evidence from in vitro studies performed on human and animal samples. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2020, 64(7), 1247–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, E.C.; Szczesny, B.; Soriano, F.G.; Olah, G.; Szabo, C. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates cytokine production through the modulation of chromatin remodeling. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 35(6), 1741–1746.Sen, N.; Paul, B.D.; Gadalla, M.M.; Mustafa, A.K.; Sen, T.; Xu, R.; Kim, S.; Snyder, S.H. Hydrogen sulfide-linked sulfhydration of NF-κB mediates its antiapoptotic actions. Mol. Cell 2012, 45, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, N.; Paul, B.D.; Gadalla, M.M.; Mustafa, A.K.; Sen, T.; Xu, R.; Kim, S.; Snyder, S.H. Hydrogen sulfide-linked sulfhydration of NF-κB mediates its antiapoptotic actions. Mol. Cell 2012, 45, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, M.; Gaddam, R.R. Hydrogen Sulfide in Inflammation: A Novel Mediator and Therapeutic Target. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2021, 34, 1368–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, J.L.; Wang, R. Hydrogen sulfide-based therapeutics: exploiting a unique but ubiquitous gasotransmitter. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, J.; Esteves, A.F.; Cardoso, E.M.; Arosa, F.A.; Vitale, M.; Taborda-Barata, L. Biological Effects of Thermal Water-Associated Hydrogen Sulfide on Human Airways and Associated Immune Cells: Implications for Respiratory Diseases. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerencsér, G.; Szabó, I.; Szendi, K.; Hanzel, A.; Raposa, B.; Gyöngyi, Z.; Varga, C. Effects of medicinal waters on the UV-sensitivity of human keratinocytes - a comparative pilot study. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2019, 63, 1417–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fioravanti, A.; Lamboglia, A.; Pascarelli, N.A.; Cheleschi, S.; Manica, P.; Galeazzi, M.; Collodel, G. Thermal water of Vetriolo, Trentino, inhibits the negative effect of interleukin 1β on nitric oxide production and apoptosis in human osteoarthritic chondrocyte. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2013, 27, 891–902. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.; Oliveira, A.S.; Vaz, C.V.; Correia, S.; Ferreira, R.; Breitenfeld, L.; Martinez-de-Oliveira, J.; Palmeira-de-Oliveira, R.; Pereira, C.M.F.; Palmeira-de-Oliveira, A.; Cruz, M.T. Anti-inflammatory potential of Portuguese thermal waters. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petropoulos, S.; Di Gioia, F.; Ntatsi, G. Vegetable Organosulfur Compounds and their Health Promoting Effects. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-J.; Cheng, M.-C.; Hsu, C.-N.; Tain, Y.-L. Sulfur-Containing Amino Acids, Hydrogen Sulfide, and Sulfur Compounds on Kidney Health and Disease. Metabolites 2023, 13, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeva, S.; Nashar, N.; Sokratreva, T.; Vankova, D.; Zamtikova, M.; Zaykov, H.; Varbanov, P. Anti-inflammatory Properties of Plant-Derived Organosulfur Compounds: Insights from Sulforaphane and Allicin. Scr. Sci. Pharm.

- Esteve, M. Mechanisms Underlying Biological Effects of Cruciferous Glucosinolate-Derived Isothiocyanates/Indoles: A Focus on Metabolic Syndrome. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.D.; Zhao, Y.H. Targeting NF-κB Pathway for Treating Ulcerative Colitis: Comprehensive Regulatory Characteristics of Chinese Medicines. Chin. Med. 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, R.M.; Abdull Razis, A.F.; Mohd Sukri, N.S.; Perimal, E.K.; Ahmad, H.; Patrick, R.; et al. Beneficial Health Effects of Glucosinolates-Derived Isothiocyanates on Cardiovascular and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules 2022, 27, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caglayan, B.; Kilic, E.; Dalay, A.; Altunay, S.; Tuzcu, M.; Erten, F.; et al. Allyl Isothiocyanate Attenuates Oxidative Stress and Inflammation by Modulating Nrf2/HO-1 and NF-kB Pathways in Traumatic Brain Injury in Mice. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019, 46, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbujor, M.C.; Petrosino, M.; Zuhra, K.; Saso, L. The Role of Organosulfur Compounds as Nrf2 Activators and Their Antioxidant Effects. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baralić, K.; Živanović, J.; Marić, Đ.; Bozic, D.; Grahovac, L.; Antonijević Miljaković, E.; Ćurčić, M.; Buha Djordjevic, A.; Bulat, Z.; Antonijević, B.; Đukić-Ćosić, D. Sulforaphane—A Compound with Potential Health Benefits for Disease Prevention and Treatment: Insights from Pharmacological and Toxicological Experimental Studies. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahey, J.; Zalcmann, A.; Talalay, P. The Chemical Diversity and Distribution of Glucosinolates and Isothiocyanates among Plants. Phytochemistry 2001, 56, 5–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latté, K.P.; Appel, K.E.; Lampen, A. Health benefits and possible risks of broccoli – An overview. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 3287–3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, Y.; Wu, K.; Wang, W.; et al. Sulforaphane down-regulates COX-2 expression by activating p38 and inhibiting NF-kappaB-DNA-binding activity in human bladder T24 cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2009, 34, 1129–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhee, R.T.; Roberts, L.A.; Ma, S.; Suzuki, K. Organosulfur Compounds: A Review of Their Anti-inflammatory Effects in Human Health. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Wu, H.; Kong, L.; Wang, S.; Xu, Z.; et al. Metallothionein is downstream of Nrf2 and partially mediates sulforaphane prevention of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes 2017, 66, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Wang, R.; Pei, Y.; Wang, D.; Wu, N.; Ji, Y.; et al. Sulforaphane alleviated vascular remodeling in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension via inhibiting inflammation and oxidative stress. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2023, 111, 109182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, C.A. Sulforaphane: Its “Coming of Age” as a Clinically Relevant Nutraceutical in the Prevention and Treatment of Chronic Disease. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 2716870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, M.; Chen, H.; Liao, Y.; He, P.; Xu, T.; Tang, J.; Zhang, N. Sulforaphane and bladder cancer: a potential novel antitumor compound. In Frontiers in Pharmacology, Vol. 14; Frontiers Media SA: 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ilic, D.; Nikolic, V.; Nikolic, L.; Stankovic, M.; Stanojevic, L.; Cakic, M. Allicin and related compounds: Biosynthesis, synthesis and pharmacological activity. Facta Univ. Ser. Phys. Chem. Technol. 2011, 9, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Saber Batiha, G.; Magdy Beshbishy, A.; Wasef, L.G.; Elewa, Y.H.A.; Al-Sagan, A.A.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Taha, A.E.; Abd-Elhakim, Y.M.; Devkota, H.P. Chemical Constituents and Pharmacological Activities of Garlic (Allium sativum L.): A Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, A.; Lahav, M.; Sakhnini, E.; et al. Allicin inhibits spontaneous and TNF-alpha induced secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines from intestinal epithelial cells. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 23, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Mathews, A.E.; Rodrigues, C.; Eudy, B.J.; Rowe, C.A.; O’Donoughue, A.; Percival, S.S. Aged garlic extract supplementation modifies inflammation and immunity of adults with obesity: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2018, 24, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qaradakhi, T.; Gadanec, L.K.; McSweeney, K.R.; Abraham, J.R.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Zulli, A. The Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Taurine on Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attiq, A.; Jalil, J.; Husain, K.; Ahmad, W. Raging the War Against Inflammation With Natural Products. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.Y.; Li, H.; Lim, H.J.; Lee, H.J.; Jeon, R.; Ryu, J.H. Anti-inflammatory activity of sulfur-containing compounds from garlic. J. Med. Food 2012, 15, 992–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prandelli, C.; Parola, C.; Buizza, L.; Delbarba, A.; Marziano, M.; Salvi, V.; Zacchi, V.; Memo, M.; Sozzani, S.; Calza, S.; Uberti, D.; Bosisio, D. Sulphurous thermal water increases the release of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 and modulates antioxidant enzyme activity. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2013, 26, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokrateva, T.; Ivanova, D.; Galunska, B.; Todorova, M.; Ivanov, D. Physicochemical analysis of Varna Basin mineral water. Surveying Geology & Mining Ecology Management (SGEM). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Ruan, J.; Zhuang, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z. Phytochemicals of garlic: Promising candidates for cancer therapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 123, 109730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habtemariam, S. Anti-Inflammatory Therapeutic Mechanisms of Isothiocyanates: Insights from Sulforaphane. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swiderski, J.; Sakkal, S.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Zulli, A.; Gadanec, L.K. Combination of Taurine and Black Pepper Extract as a Treatment for Cardiovascular and Coronary Artery Diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, J.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, J.; Ma, Z.; Zhu, W.; Zou, S. The effect of taurine on the toll-like receptors/nuclear factor kappa B (TLRs/NF-κB) signaling pathway in Streptococcus uberis-induced mastitis in rats. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2011, 11, 1740–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhang, W.; Guo, Z.; Ma, Q. Arachidonic acid metabolism in health and disease. MedComm 2023, 4, e363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Z.; Li, M.; Xu, J.; Howell, D.C.; Li, Z.; Chen, F.E. Recent development on COX-2 inhibitors as promising anti-inflammatory agents: The past 10 years. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 2790–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D.I.; Lee, A.H.; Shin, H.Y.; Song, H.R.; Park, J.H.; Kang, T.B.; Lee, S.R.; Yang, S.H. The Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-α) in Autoimmune Disease and Current TNF-α Inhibitors in Therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, K.; Gu, H.; Yuan, Z.; Xu, X. Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha Signaling and Organogenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 727075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Wu, Q. Sulforaphane protects intestinal epithelial cells against lipopolysaccharide-induced injury by activating the AMPK/SIRT1/PGC-1ɑ pathway. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 4349–4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhee, R.T.; Ma, S.; Suzuki, K. Sulforaphane Protects Cells against Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Inflammation in Murine Macrophages. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, C.; Wang, C.; Li, P.; Huang, Y.; Lu, X.; Shi, M.; Zeng, C.; Qin, S. Effect of Garlic Organic Sulfides on Gene Expression Profiling in HepG2 Cells and Its Biological Function Analysis by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis System and Bio-Plex-Based Assays. Mediators Inflamm. 2021, 7681252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, R.; Deng, S.; Qin, Q.; Ran, C.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, L. Mechanism of taurine reducing inflammation and organ injury in sepsis mice. Cell. Immunol. 2022, 375, 104503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barua, M.; Liu, Y.; Quinn, M.R. Taurine chloramine inhibits inducible nitric oxide synthase and TNF-alpha gene expression in activated alveolar macrophages: decreased NF-kappaB activation and IkappaB kinase activity. J. Immunol. 2001, 167, 2275–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, A.; Bhatia, M. Hydrogen Sulfide: A Versatile Molecule and Therapeutic Target in Health and Diseases. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, N.; Kurata, M.; Yamamoto, T.; et al. The role of interleukin-1 in general pathology. Inflamm. Regener. 2019, 39, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, K.; Torres, R. Role of interleukin-1beta during pain and inflammation. Brain Res. Rev. 2009, 60, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Qian, H.; Xiao, M.; Lv, J. Role of signal transduction pathways in IL-1β-induced apoptosis: pathological and therapeutic aspects. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2023, 11, e762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.; Burgener, S.; Vezyrgiannis, K.; Wang, X.; Acklam, J.; Von Pein, J.; Pizzuto, M.; Labzin, L.; Boucher, D.; Schroder, K. Caspase-4 dimerisation and D289 auto-processing elicit an interleukin-1β-converting enzyme. Life Sci. Alliance 2023, 6, e202301908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luotola, K. IL-1 Receptor Antagonist (IL-1Ra) Levels and Management of Metabolic Disorders. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villatoro, A.; Cuminetti, V.; Bernal, A.; et al. Endogenous IL-1 receptor antagonist restricts healthy and malignant myeloproliferation. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, J.M.; Duarte, S.; Ribeiro, A.C.; Mascarenhas, P.; Noronha, S.; Alves, R.C. Association between IL-1A, IL-1B and IL-1RN Polymorphisms and Peri-Implantitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maculewicz, E.; Antkowiak, B.; Antkowiak, O.; et al. The interactions between interleukin-1 family genes: IL1A, IL1B, IL1RN, and obesity parameters. BMC Genomics 2022, 23, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, L.A.; Dutreil, M.; Fattman, C.; Pandey, A.C.; Torres, G.; Go, K.; Phinney, D.G. Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist mediates the antiinflammatory and antifibrotic effect of mesenchymal stem cells during lung injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 11002–11007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target gene (Human) |

Nucleotide sequence (5`-3`) |

|---|---|

| Actin beta | F GTG GCC GAG GAC TTT GAT TGR CCT GTA ACA ACG CAT CTC ATA |

| COX-2 | F GAA ACA GAG AAG TTG GCA GCAR GGC AGG ATA CAG CTC CAC AG |

| TNF-α | F CTC TTC TGC CTG CTG CAC TTTR ATG GGC TAC AGG CTT GTC ACT |

| IL-1β | F CCA CCT CCA GGG ACA GGA TAR AGA ATT AGC AAG CTG CCA GGA |

| IL1RN | F GCC CAT CCT CAG GAC CTT TCR ATG TCC TAG CCA TCC CCA CT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).